Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effectiveness of interventions designed to improve the health behaviours of health professionals.

Design

Systematic review.

Data sources

Database searches: Medline, Cochrane library, Embase and CINAHL.

Review methods

This systematic review used Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines to compare randomised controlled trials of health professionals, published between 2010 and 2021, which aimed to improve at least one health behaviour such as physical activity, diet, smoking status, mental health and stress. Two independent reviewers screened articles, extracted data and assessed quality of studies and reporting. The quality of articles was assessed using the Effective Public Health Practice Project quality assessment tool and the completeness of intervention reporting was assessed.

Outcome measures

The outcome assessed was change in behaviour between intervention and control groups from baseline to follow-up.

Results

Nine studies met the eligibility criteria, totalling 1107 participants. Health behaviours targeted were mental health and stress, physical activity, and smoking cessation, physical activity and nutrition. Six interventions observed significant improvements in the health behaviour in the intervention compared with control groups. Seven of the studies selected in person workshops as the mode of intervention delivery. The quality of the included studies was high with 80% (7/9) graded as moderate or strong.

Conclusions

Although high heterogeneity was found between interventions and outcomes, promising progress has occurred across a variety of health behaviours. Improving reporting and use of theories and models may improve effectiveness and evaluation of interventions. Further investigation is needed to recommend effective strategies.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42021238684.

Keywords: EDUCATION & TRAINING (see Medical Education & Training), PRIMARY CARE, Health policy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A strength is that the highest quality study designs (randomised controlled trials) have been reviewed providing confidence in the findings of studies and the potential mechanisms of action or attributes which contribute to success.

A strength is that an inclusive definition of health behaviours was used to allow future research to be informed by work done for a range of health behaviours.

A limitation is that the inclusive nature of interventions meant high heterogeneity existed between interventions outcomes, preventing a quantitative meta-analysis from being possible.

Introduction

Health professionals are essential components of health services that provide support for individuals, communities and society. Health professionals’ personal health directly impacts their ability to provide safe and effective health services.1 Health professionals are at higher risk of experiencing chronic health conditions and progression of disease2 and are at increased risk of unhealthy coping mechanisms when compared with community members.3 4 Initiatives that support healthy lifestyle behaviours of health professionals are clearly warranted.

The work environment of health professionals is increasingly demanding, with pressure to work longer hours and provide efficient and effective care.5 Health professionals who directly interact with patients experience significant work-related psychological pressures and emotional exhaustion, placing them at risk of negative health outcomes.3 The cumulative toll of these demands on health professionals is evident in their physical health, high rates of absenteeism, burnout, reduced clinical hours and staff turnover.1 6 The true financial cost of poor lifestyle beahviours on health professionals is poorly understood6 7 but estimates from the USA indicate that the loss of clinical hours and turnover alone costs US$7600 per employed physician per year.6 The COVID-19 epidemic has placed additional strain on healthcare systems and emphasised the importance of effective approaches to prevent health professional becoming secondary victims of this increased burden.3 Efforts to support health professionals to improve their health can reduce these costs and enhance the quality of care.

The adoption of healthy lifestyles and the development of healthy coping mechanisms provide a sound foundation on which to increase resilience for the challenges faced in the workplace.7 Key modifiable health behaviours such as low physical activity, poor diet and eating behaviours, smoking and alcohol abuse are common causes of many health problems experienced by health professionals.2 Understanding the most effective approaches to support lasting behaviour change is key to improving health professional’s health. The aim of this systematic review is to identify and critically appraise interventions which aim to improve the health behaviours of health professionals.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.8 The review was registered with PROSPERO (ID: CRD42021238684). Due to the high heterogeneity expected in interventions and outcomes, this review employed a descriptive approach to identify and critically appraise interventions based on their outcomes and areas of behaviour change in a way that can be used to inform future research and policy decisions.

Search strategy and selection criteria

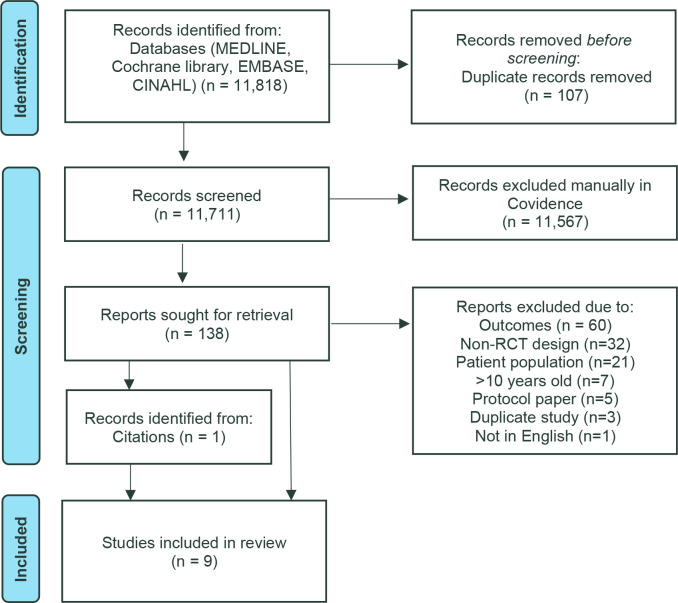

Searches of published scientific literature were conducted up to the 15 January 2021 using the following databases: Medline, Cochrane Library, Embase, CINAHL. Boolean connector AND was used to combine three search strings related to (1) health professionals/students, (2) intervention and (3) specific intervention details. Boolean connector OR was used to combine search terms within each string, the full list of search terms is provided in online supplemental appendix 1. Studies with full text available, peer reviewed, published in English since 2010 were included. The studies were imported to Covidence9 to assist in article management. The study selection process is illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart of study selection.

bmjopen-2021-058955supp001.pdf (67.3KB, pdf)

Inclusion criteria were: (1) studies on health professionals of any age and profession, working in any health setting including tertiary, secondary or primary care or residential care; (2) studies of interventions aimed to improve personal health behaviours of participants through either activities to modify behaviour within intervention sessions, such as the provision of food or participation in an exercise class, or influence behaviour through education and/or counselling; (3) studies assessing changes in health behaviours including diet, physical activity, and exercise, smoking and alcohol consumption, as well as well-being, mental health and stress management; (4) studies using a randomised controlled design.

Exclusion criteria were: (1) studies with mixed populations where data of health professionals could not be separated from other populations, such as health professionals/students and administrative professionals in health environments; (2) studies where the primary intervention focused was not on health behaviour change; and (3) studies using non-randomised or cross-sectional designs.

Within Covidence, study titles and abstracts were screened in duplicate, independently by three members of the research team (JC, KB, LB). Full texts were retrieved for 138 articles that met inclusion criteria or required further information to decide. Full-text articles were screened against the selection criteria in duplicate by JC and KB. Disagreement on inclusion/exclusion was resolved by discussion with the research team until consensus. Reasons for exclusion are listed in figure 1. Included articles’ reference lists were searched for other relevant articles not identified in the search strategy.

Data analysis

Data for the included papers were extracted independently by two researchers (JH, LM, KB, JC) within Covidence using a template design specifically for the review. Data extracted included: country, aim, setting, number of intervention arms, number of participants, profession, attrition rate, intervention description (dose, intensity and description of activities), control group description, tools for outcome measures, follow-up time points, behaviour change outcomes (changes in diet, physical activity, smoking or alcohol consumption), other outcomes of interest (body mass index, cholesterol, weight, mental health scores, stress scores, stage of change, process of change and self-efficacy). Differences in the extracted data were reviewed and discussed by two researchers for consensus. No study authors were contacted for further information.

The focus of analysis was the difference in health behaviour change between intervention and control groups, such as a change in physical activity, dietary intake, smoking or alcohol behaviours. Secondary outcomes were differences between the interventions and control groups in associated health outcomes such as weight, cholesterol, mental health and stress scores or stage of change. Interventions were deemed to be effective if there was an observed statistically significant improvement in a health behaviour between intervention and control groups (p<0.05).

Quality assessment of included studies was conducted in duplicate by JH, JC, KB, LM using two tools: the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) quality assessment tool9 and the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR).10 Covidence was used to independently record quality assessment answers and supporting text. Conflicts in rating were resolved via team discussion and reviewed by LB and JP.

Patient and public involvement

None.

Results

The initial search identified 11 818 publications; 107 duplicate records were removed. Following title and abstract screening, 138 studies were assessed for eligibility using their full-text publication. The main reasons for exclusion, outlined in figure 1, were for assessing non-health behaviour outcomes (n=60), using non-randomised controlled trial study designs (n=32), and not studying health professional populations (n=21). Citation searches of eligible studies identified one additional study for inclusion. Nine studies were eligible for inclusion.11–19

The characteristics of the nine studies included in the systematic review are outlined in table 1. Four of the studies were conducted with nurses,14–16 18 19 four were conducted on trainee physicians11–13 17 and one study included nurses, physiotherapists and midwives.18 Eight of the nine studies included participants without specific health conditions, while one study focused on participants with chronic lower back pain.18 Over half of the studies (n=5) focused on early career, newly graduated or trainee health professionals.11–13 16 17 Majority of participants were employed in large hospital settings,11–15 17–19 with one study conducted in an academic medical centre.16 The studies were conducted in the USA (n=4),11 12 16 17 Australia (n=1),13 Iran (n=1),14 Spain (n=1),15 Finland (n=1)18 and Jordan (n=1).19 Rates of attrition ranged between none to 22% (mean across all studies=7.6%). All studies comprised one trial with two arms, apart from Saadat et al (2012) with three arms17 and Suni et al with four arms.18 Saadat et al included an intervention group and two control groups, whereby one control group received no treatment with time off from duties and the other control group received no treatment and continued routine clinical duties (RD).17

Table 1.

Characteristics of included randomised controlled trials (n=9) examining health behaviour change in health professionals, ordered alphabetically by first author

| Author (year) | Country | Study stated aim | Population | Participants | Attrition rate |

| Alkhawaldeh et al (2020)19 | Jordan | To evaluate the effectiveness of the stress management interventional programme in reducing occupational stress and improving coping strategies. | Public health nurses | 170 | 7.6% |

| Axisa et al (2019)13 | Australia | To evaluate the effectiveness of a workshop intervention to promote well-being for Australian physician trainees | Physician trainees of RACP | 59 | 22% |

| Moosavi et al (2017)14 | Iran | To determine the effect of a TTM-based intervention on level of physical activity in ICU nurses | Nurses, working in ICU | 68 | 0 |

| Mujika et al (2014)15 | Spain | To test the efficacy, acceptability and feasibility of a motivational interviewing based smoking cessation intervention with nurses. | Nurses, currently smoking | 30 | 0 |

| Saadat et al (2012)17 | USA | To evaluate the effects of implementing an evidenced-based, workplace preventive intervention with anaesthesiology residents. | Anaesthesiology residents | 60 | 3% |

| Sampson et al (2019)16 | USA | To evaluate the effects of MINDBODYSTRONG for Healthcare Professionals Programme on stress, anxiety, depressive symptoms, healthy lifestyle behaviours and job satisfaction. | Nurses, residency programme | 93 | 4.3% |

| Suni et al (2018)18 | Finland | To investigate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of three intervention-arms (combined neuromuscular exercise and back care counselling or either alone) compared with non-treatment, for improvement of pain, ability to work and fear avoidance related to work/physical activity. | Female health workers with lower back pain (nurses, nurses’ aides, specialist nurses, assistant physiotherapists, physiotherapists and midwives) | 219 | 19.6% |

| Thorndike et al (2012)12 | USA | To test the effectiveness of a nutrition and exercise maintenance intervention to preventing weight regain. | Residents, internal medicine and medicine/paediatric | 304 | 9% |

| Thorndike et al (2014)11 | USA | To test use and access to activity monitor information in a hospital-based physical activity intervention to increase physical activity. | Residents, internal medicine and medicine/paediatric | 104 | 4.8% |

ICU, intensive care unit; RACP, Royal Australasian College of Physicians; TTM, transtheoretical model of behavioural change.

The description of interventions and outcomes are outlined in table 2. Interventions targeted a single or combination of health behaviours. Health behaviours included physical activity (n=4),11 12 14 18 diet (n=2),11 12 stress management (n=4),13 16 17 19 smoking cessation (n=1)15 and alcohol use (n=1).13 Techniques to change behaviour included education and instructions on how to perform the health behaviour (n=9),11–20 demonstration of health behaviours (n=2),14 18 goal setting (n=4),12 15 16 19 and environment change (n=2).11 12 Environment changes included access to an onsite fitness centre along with personal training and staff nutritionist, as well as a catered meal provided weekly at a work seminar11 or every 3 months in a group seminar.12

Table 2.

Description of health behaviour change interventions and outcomes of included randomised controlled trials (n=9), ordered alphabetically by first author

| Authors | Activity description | Primary outcomes | Secondary outcomes | Effectiveness | Quality |

| Alkhawaldeh et al (2020)19 | 2-hour sessions on stress, skills in stress management techniques, cognitive change and behaviours to cope with stress and avoid negative outcomes from stress. Under pinned by Folkman, Lazarus, Dunkel Schetter De Longis and Gruen’s cognitive theory of stress and coping. |

Occupational stress via Nurses Stress Scale. Coping strategies via Brief-COPE Scale. |

Not applicable | Significant improvement among intervention group compared with control group for total occupational stress scores, total coping strategies scale scores. | Strong |

| Axisa et al (2019)13 | 4-hour workshop on well-being, health and stress management techniques. | Alcohol use via AUDIT. Depression, anxiety and stress via DASS-21. Secondary traumatic stress and compassion satisfaction via ProQOL. |

Not applicable | No significant difference was found between intervention and control. | Weak |

| Moosavi et al (2017)14 | 1-hour CBT session for coping mechanisms, benefit of PA, time management for PA, PA strategies. 1 hour practical exercise training session. Isometric exercise CD to be used at home for 30 min/day. |

Physical activity via MET min/week questionnaire. | Stages of change (SoC). Self-Efficacy Scale. Decisional Balance Questionnaire Process of change. |

Significant improvement among intervention group compared with control group for: MET scores, SOC, POC, Self-efficacy, perceived benefits of PA. | Weak |

| Mujika et al (2014)15 | 1 hour session/week of patient centred MI sessions with a therapist to: establish a desire to quit, set a quitting date, maintain abstinence, overcome withdrawal symptoms and adopt a new lifestyle without tobacco. | Smoking cessation verified biochemically via urine cotinine and expired carbon monoxide. | Mean number of cigarettes smoked via self-reporting. Nicotine dependence via FTND. SoC via SOCQ. Self-efficacy via general self-efficacy test. Depression via PHQ-9. | Significant improvement among intervention group compared with control group for smoking cessation, mean no. of cigarettes per day, SOC, depression scores. | Moderate |

| Saadat et al (2012)17 | 1.5 hour/week CBT based sessions with four components on coping with work and family stress. | Job/family stress via 48 item (RQS) Coping strategies via self-reporting. Social support via an adaption of PSS. Anxiety via STAI. Depression via CESD. Physical symptoms via CHIPS. Alcohol and tobacco use via NSDUH. |

Not applicable | Significant improvement among intervention group compared with control group 2 for anxiety score, perceived stress as a parent, coping: problem-solving scores. Significant improvement among intervention compared with both control groups for social support at work. |

Moderate |

| Sampson et al (2019)16 | 45 min/week MINDBODYSTRONG sessions on: caring for the mind, caring for the bodyand skills building. CBT concepts to establish weekly goals and complete skills-building activities weekly. |

Perceived stress via PSS. Anxiety via GAD-7. Depressive symptoms via the 9-item Personal Health Questionnaire. Healthy lifestyle beliefs and healthy lifestyle behaviours via adaption of beliefs scales by Melnyk and colleagues. Job satisfaction via JSS. |

Not applicable | Significant improvement among intervention group compared with control group for perceived stress, anxiety scores, depressive symptoms scores, healthy lifestyle behaviours scores. | Strong |

| Suni et al (2018)18 | 1 hour/ 2× per week. First 8 weeks exercise was under instruction, remaining 16 weeks was 1 instructed session 1 at home. A modified Pilates-type exercise programme, started with easier exercises, and was progressive in terms of demands for coordination, balance and muscular strength over three stages. An additional 10×45 min counselling sessions were given exercise+counselling arm. CBT was used for the framework and PBL used to implement counselling sessions. |

Intensity of lower back pain measured with the Visual Analogue Scale (0–100 mm). | Bodily pain interfering with work (via GLMM). FABs related to work/PA (via GLMM). Cost-effectiveness ratio calculated from difference in mean total costs and mean effect (no. sick days or QALYs) between arms. |

Significant improvement for only the combined (exercise+counselling) arm in intensity of LBP, pain interfering with work, FABs related to work. Significant improvement for only the exercise-arm in FABs related to PA. Significant improvement for only the combined (exercise+counselling) arm in cost effectiveness. |

Strong |

| Thorndike et al (2012)12 | Intervention via website—PA and nutrition goals set weekly (monitored by nutritionist). Website provided resources and journaling option. Every 3 months option for face-to-face nutrition and/or PT session and a lunch-time group seminar. |

Weight loss, % weight loss. PA via estimate of intensity level and minutes spent in PA per week during previous 3 months. |

Diet via FFQ. BMI, waist circumference, BP, cholesterol, fasting serum glucose. |

No significant difference was found between intervention and control. | Moderate |

| Thorndike et al (2014)11 | All participants received ‘Be Fit’ workplace diet and PA intervention. Intervention group had access to PA monitor and website for tracking steps. Be Fit programme included 1 /week catered lunch. Access to onsite fitness centre and 1 hour PT session/week and two nutritionist sessions/week. |

PA measured in steps via activity monitor (Fitbit). | Compliance with wearing the monitor. | No significant difference was found between intervention and control. | Moderate |

AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CBT, cognitive behavioural theory; CD, Compact Disc; CESD, The Center of Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; CHIPS, Cohen-Hoberman Inventory of Physical Symptoms; DASS-21, Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 item; FAB, fear avoidance behaviour; FFQ, Food Frequency Questionnaire; FTND, Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence; GAD-7, Generalised Anxiety Disorder Scale; GLMM, generalised linear mixed model; JSS, Job Satisfaction Scale; LBP, Lower Back Pain; MET, Metabolic Equivalent of Task Scale; MI, motivational interviewing; NSDUH, National Survey on Drug Use and Health; PA, physical activity; PBL, problem-based learning; PHQ-9, The Patient Health Questionnaire – 9 items; POC, process of change; ProQOL, Professional Quality of Life Scale; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; PT, personal trainer; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year; RQS, Role Quality Scale; SOCQ, Stage of Change Questionnaire; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory.

The intervention components were frequently underpinned by behaviour change theory and the delivery methods varied widely. Behaviour change theories and models used in interventions included: cognitive behavioural theory (n= 4),14 16–18 transtheoretical/stage of change model (n=2),14 15 motivational interviewing combined with cognitive dissonance theory (n=1),15 Pearlin and Schooler’s hierarchy of coping mechanisms (n=1)17 and Folkman and colleagues cognitive theory of stress and coping (n=1).19 Reporting on how the theory unpinning the interventions varied, with five reporting how the theory was applied to the interventions,13–16 18 two did not include details on how theory was applied,17 19 and in two theory was not applied.11 12 Implementation of interventions was often poorly described including lack of information about delivery tools, resources and training/qualifications of intervention providers. Two studies11 15 provided the intervention only through individual sessions, the remaining studies used a group setting.

The intensity of sessions and length of interventions varied from 4 to 130 hours over time periods of half a day up to 9 months. The frequency of delivery included one-off sessions (2–4 hours in length) (n=2),13 14 1 hour sessions each week (n=3),15–17 1 hour sessions twice a week (n=1)17 and 4 hour sessions three times a week (n=1).19 In person contact with participants varied across interventions with four studies having minimal in person contact following the initial intervention instructions, two had no in person contact until the 6-month follow up13 14 and two had contact via email or website until follow up11 or group meeting at 3 months.12 Two interventions used technology to contact and prompt participants on physical activity and/or nutrition goals, via monthly email and/or website access.11 12 Length of time until follow-up ranged from no follow-up (n=3),12 14 17 2 months post intervention (n=1),19 3 months post intervention (n=3)13 15 16 and 6 months post intervention (n=2).11 18

The outcome measures varied between the studies. In one study, physical activity was measured in steps via an activity monitor,11 in another study estimated intensity and minutes spent in physical activity per week in the last 3 months,12 and in another study the Metabolic Equivalent of the Task (MET) Scale through a questionnaire or physical activity per week.14 In one study, dietary behaviour was assessed via a food frequency questionnaire to estimate the number of serves from major food groups per day during the previous month, and body weight was measured with the percentage of weight loss calculated.12 In one study, self-reported smoking cessation was confirmed through biochemical measures (urine cotinine and expired carbon monoxide).15 In one study, changes in lower back pain were measured using the visual analogue scale (0–100 mm).18 Four studies assessed mental health and stress outcomes, using different tools to measure stress, coping, depression and anxiety, which included the Nurses Stress Scale,19 the Brief-Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced (COPE) scale,19 Perceived Stress Scale,16 Professional Quality of Life Scale,13 Job Satisfaction Scale,16 Generalised Anxiety Disorder Scale,16 Depression Anxiety Stress Scale,13 the Center of Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale,17 State-Trait Anxiety Inventory.17 The two studies that assessed alcohol used the National Survey on Drug Use and Health17 survey or an adaption of the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test.13 One study measured cigarette use using the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, which contains six items for quantity, compulsion and dependence.15 Finally, one study used the Cohen-Hoberman Inventory of Physical Symptoms which uses a 5-point Likert scale to measure the burden of physical symptoms resulting from psychological effects.17

Six of the nine studies (n=8 interventions) observed statistically significant outcomes between the intervention and control group.14–19 Of these, three were well-being interventions with mental health and stress-related outcomes,16 17 19 two were physical activity interventions14 18 and one was a smoking cessation intervention.15 Four of the effective interventions were delivered only through education and counselling on health behaviours, one for smoking cessation15 and three for stress management behaviour.13 17 19 From a four-armed study, the exercise combined with counselling was more effective at reducing lower back pain than the intervention arms providing only exercise or counselling.18 One study combined education and instructions to conduct exercises at home for 6 months and significantly reduced MET scores (intervention 2813.06 (SD 3172.58), control 1196.47 (SD 1441.29), p=0.02).14

Of studies that measured readiness or preparation to change behaviour (n=2),14 15 significant improvement was observed in the intervention groups, with participants progressing from preparation and contemplation stages to action and maintenance.14 15 In one study, the stage of change for physical activity improved, resulting in 91.2% at the stage of action and 5.9% at the stage of maintenance (p=0.0001), while the control group remained relatively constant with only 5.9% in the action stage and none in the maintenance stage (p=0.002).14 Similar progression in the stages of change occurred in the other study targeting smoking cessation, with the majority of participants in the intervention group progressing to preparation and action stages, 20% and 46% respectively, compared with most participants in the control group remaining in the precontemplation and contemplation stages (preparation stage intervention 47% vs control none, p=0.01, action stage intervention 40% vs control 3%, p=0.01).15

Of the three well-being interventions with a focus on mental health and/or stress management, all reported statistically significant reductions in stress and anxiety.16 17 19 One study observed lower depressive scores in the intervention group when compared with the control group16 while another study used two control groups, with one group released from duties (rostered time off) for the duration of the workshop (1 hour) while the other group continued RD.17 Statistically significant improvements occurred only between the intervention and the control group not released from duties with lower scores for anxiety (intervention 38.4 vs RD control 45.6, p = 0.02), perceived stress as a parent (intervention 21.7 vs RD control 24.1, p = 0.03), and increased coping scores (intervention 27.7 vs RD control 27.1, p = 0.03).17 The only effective outcome improved in the intervention group compared with both control groups was perceived social support at work (intervention 27.3 vs RD control 26.7 and rostered time off control 25.5, p = 0.02).17

The EPHPP tool was used to assess the quality of each of the studies, with the summary of ratings presented in table 3. Of the nine studies, three were rated as strong,16 18 19 four as moderate,11 12 15 17 and two as weak.13 14 The components in which interventions received a low score were study blinding,11–15 17 not controlling for confounders,13 14 or selection bias.15

Table 3.

The Effective Public Health Practiced Project checklist criteria for each study (n=9)

| Selection bias | Study design | Confounders | Blinding | Data collection | Withdrawal and dropout | Overall rating* | |

| Alkhawaldeh et al19 | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Strong |

| Axisa et al13 | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Weak | Strong | Moderate | Weak |

| Moosavi et al14 | Strong | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Strong | Strong | Weak |

| Mujika et al15 | Weak | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Strong | Moderate |

| Saadat et al17 | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Moderate |

| Sampson et al16 | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Strong | Strong | Strong |

| Suni et al18 | Strong | Strong | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Strong |

| Thorndike et al11 | Strong | Strong | Strong | Weak | Strong | Strong | Moderate |

| Thorndike et al12 | Strong | Strong | Strong | Weak | Strong | Strong | Moderate |

*Overall rating based on Strong=0 weak scores, Moderate=1 weak score, Weak= ≥2 weak scores.

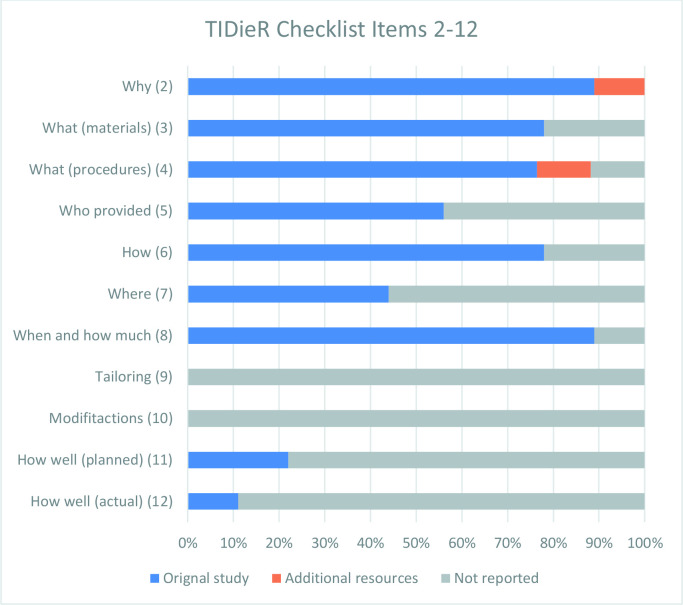

The TIDieR checklist report is shown in figure 2. Checklist items 2–8 were consistently reported on the primary publication for 73% of the included interventions. Checklist items 9–11 were not reported across most interventions. These items related to reporting on tailoring, modification, how well planned the interventions were, and how they were implemented. No interventions reported tailoring or modifications, two interventions11 15 reported intended plans to check how well the intervention delivery adhered to plan, while only one study measured and reported how well the intervention was delivered.11 Overall, information for 49.5% of 11 of the checklist items (items 2–12) was provided on the primary paper.

Figure 2.

Percentage of randomised controlled trial (n=9) with adequate Template for Intervention Description and Replication items (2–12) reported in the original study, additional sources or not reported.

Discussion

Summary of evidence

This systematic review has identified a modest collection of heterogeneous studies that show strong promise in enabling improvements in health professionals’ personal health behaviours. The professions included trainee physicians, nurses, physiotherapists, and midwives, targeting behaviours related to physical activity, nutrition, stress management, and coping strategies to improve anxiety and depression. Overall, most studies demonstrated significant improvements in health behaviours, which is encouraging and worthy of further investigation through health workforce policy given the considerable cost related to poor health of health professionals.6 Despite the heterogeneity of studies, significant progress was found for both direct and indirect behaviour change interventions.

Intervention mode and intensity were keyways that studies were heterogeneous. The most common mode and intensity was in person contact at least once a week. Higher intensity of contact has been shown to increase effectiveness in physical activity interventions.21 While increased intensity of contact with participants may increase the cost of interventions,22 a cost effective approach to increase contact has been demonstrated through technology.23 The use of technology among the reviewed studies was limited and the intensity of use was minimal at once a week and/or month,11 or every 3 months.12 Prior studies have noted21 24 the optimal intensity via technology is between three to five text messages a day21 and that technology intervention messages require extensive tailoring of content (eg, to match the stage of change etc).21 25 Future interventions should optimise the intensity of contact with participants to enhance intervention outcomes, such as through the use of technology.

Comparison

The included studies involved sessions to raise awareness and/or build knowledge among participants. The findings of the review suggest that the effectiveness of interventions was enhanced when counselling or group education workshops were used in combination with activities or approaches which required participants to perform behaviours. This is consistent with previous studies in behaviour change in other populations where effectiveness was enhanced by incorporating factors that aim to promote and support the performance of behaviours and engagement in self-regulation techniques (eg, goal setting, self-monitoring).21 26 Future interventions should combine activities that promote action and performance of behaviours to increase the likelihood of change.

Interventions designed for health professionals need to allow for many interacting factors due to differences between work pressures, settings, access to support and resources and these factors increase the complexity of planning and tailoring of interventions to effectively promote behaviour change. The use of theory to underpin interventions can provide a practical means to approach these difficulties and evaluate outcomes.27 Across the review, studies used a variety of theories and models including the stages of change model,28 motivational interviewing29 and cognitive behavioural therapy.30 Previous studies have shown that combining theories and approaches has been effective in changing health behaviours.26 Reporting on how interventions are mapped to the underpinning theory is required to improve reproducibility of successful interventions.26 31Including a model to classify progress across interventions may also capture more subtle changes and improve strategies for addressing and/or measuring relapse and maintenance of changes.32 Behaviour change can be challenging to sustain with some individuals experiencing several relapses when attempting to maintain new health behaviours.21 26 32 Collectively, the evidence suggests that the use of a combination of theories and approaches can provide a means to design, implement and evaluate interventions to best meet the specific challenges of the health setting and facilitate sustainable change.

The follow-up activities and duration of studies varied widely. It has been suggested that a key time where individuals are likely to experience behaviour change relapse is in the first 6 months.32 33 The reviewed interventions may be failing to capture the patterns of behaviour maintenance and relapse occurring within the first 6 months following the intervention. Follow-up is important to establish if the intervention is effective at maintaining behaviour change beyond the life of the intervention.33 Previous studies indicate that a minimum, collection of follow-up data at 6 months post participation is ideal to assess maintenance of behaviour change.33 Future interventions should follow-up at 12 months and 24 months post programme to further increase understanding of programme effectiveness.33 34

Limitations

This review has highlighted a number of gaps which may be addressed in future research. The reviewed interventions were focused on a limited number or specific professional groups. Extending inclusion of intervention activities to a diverse group of health professions may increase social support and promote greater team connectedness.21 35 Dietary behaviour was only addressed in one intervention, and as diet has a significant influence on health, interventions to support healthy dietary behaviours may be worthy of being prioritised. Evaluation of cost effectiveness was also limited. Comparing intervention cost to improvement in quality of life and reduced staff turnover and absenteeism can make interventions more likely to be worthy of implementation. Factors which support action such as social support are important areas to be addressed to improve the effectiveness of interventions.21 Overall, the progress achieved across a variety of behaviours is promising and key gaps have been highlighted, although determining the future direction for interventions for health professionals may be challenging.

To advance the evidence consistent reporting methods with consensus on ideal outcomes for tracking specific health behaviours are needed. Improving the reporting of behaviour change strategies, their associated theories and models, and their outcomes will enhance future intervention design. Additionally, integrating monitoring and evaluation measures into intervention design including measures of behaviour maintenance and intervention cost effectiveness will provide a strong evidence base on which to develop future interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the University Health Librarian for her assistance in drafting the search and Dr Emily Burch for conducting the search.

Footnotes

Twitter: @laurenball01

Contributors: JH, JC, KB, LM and LB accessed and verified the study data. LB conceived and designed the review. JH analysed the data and interpreted the data. JH wrote the first draft of the manuscript with input from JC, KB and JP. All authors critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. LB and JP supervised the study. All authors had access to data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. JH acts as guarantor.

Funding: Julie Hobby’s work received financial support from Griffith University (no award/grant number). At the time of this project A/Prof Lauren Ball’s salary was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (APP1173496). The funders of the study (NHMRC and Griffith University) had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The funders of this review had no known role in any study included in the review.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Koinis A, Giannou V, Drantaki V, et al. The impact of healthcare workers job environment on their mental-emotional health. coping strategies: the case of a local General Hospital. Health Psychol Res 2015;3:1984. 10.4081/hpr.2015.1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dayoub E, Jena AB. Chronic disease prevalence and healthy lifestyle behaviors among US health care professionals. Mayo Clin Proc 2015;90:1659–62. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barello S, Palamenghi L, Graffigna G. Burnout and somatic symptoms among frontline healthcare professionals at the peak of the Italian COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res 2020;290:113129. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teo YH, Xu JTK, Ho C, et al. Factors associated with self-reported burnout level in allied healthcare professionals in a tertiary hospital in Singapore. PLoS One 2021;16:e0244338. 10.1371/journal.pone.0244338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brand SL, Thompson Coon J, Fleming LE, et al. Whole-system approaches to improving the health and wellbeing of healthcare workers: a systematic review. PLoS One 2017;12:e0188418. 10.1371/journal.pone.0188418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han S, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, et al. Estimating the attributable cost of physician burnout in the United States. Ann Intern Med 2019;170:784–90. 10.7326/M18-1422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olson K, Marchalik D, Farley H, et al. Organizational strategies to reduce physician burnout and improve professional fulfillment. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 2019;49:100664. 10.1016/j.cppeds.2019.100664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n160. 10.1136/bmj.n160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans N, Lasen M, Tsey K. Appendix A: effective public health practice project (EPHPP) quality assessment tool for quantitative studies. A Systematic Review of Rural Development Research SpringerBriefs in Public Health 2015:45–55. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014;348:g1687. 10.1136/bmj.g1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thorndike AN, Mills S, Sonnenberg L, et al. Activity monitor intervention to promote physical activity of physicians-in-training: randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 2014;9:e100251. 10.1371/journal.pone.0100251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thorndike AN, Sonnenberg L, Healey E, et al. Prevention of weight gain following a worksite nutrition and exercise program: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med 2012;43:27–33. 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Axisa C, Nash L, Kelly P, et al. Burnout and distress in Australian physician trainees: evaluation of a wellbeing workshop. Australas Psychiatry 2019;27:255–61. 10.1177/1039856219833793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moosavi S, Farmanbar R, Fatemi S, et al. The effect of a TTM-Based intervention on level of physical activity in ICU nurses. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2017;19. 10.5812/ircmj.59033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mujika A, Forbes A, Canga N, et al. Motivational interviewing as a smoking cessation strategy with nurses: an exploratory randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 2014;51:1074–82. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sampson M, Melnyk BM, Hoying J. Intervention effects of the MINDBODYSTRONG cognitive behavioral skills building program on newly licensed registered nurses' mental health, healthy lifestyle behaviors, and job satisfaction. J Nurs Adm 2019;49:487–95. 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saadat H, Snow DL, Ottenheimer S, et al. Wellness program for anesthesiology residents: a randomized, controlled trial. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2012;56:1130–8. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2012.02705.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suni JH, Kolu P, Tokola K, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of neuromuscular exercise and back care counseling in female healthcare workers with recurrent non-specific low back pain: a blinded four-arm randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2018;18:1–13. 10.1186/s12889-018-6293-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alkhawaldeh Ja'far M, Soh KL, Mukhtar F, et al. Stress management training program for stress reduction and coping improvement in public health nurses: a randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs 2020;76:3123–35. 10.1111/jan.14506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khatri IA, Farooq S, Khatri MA. Preventing stroke at door step–need for a paradigm shift in delivery of preventive healthcare. Pakistan Journal of Neurological Sciences 2016;11:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greaves CJ, Sheppard KE, Abraham C, et al. Systematic review of reviews of intervention components associated with increased effectiveness in dietary and physical activity interventions. BMC Public Health 2011;11:1–12. 10.1186/1471-2458-11-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oxman AD, Thomson MA, Davis DA, et al. No magic bullets: a systematic review of 102 trials of interventions to improve professional practice. CMAJ 1995;153:1423. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michie S, Yardley L, West R, et al. Developing and evaluating digital interventions to promote behavior change in health and health care: recommendations resulting from an international workshop. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e7126. 10.2196/jmir.7126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stephenson A, McDonough SM, Murphy MH, et al. Using computer, mobile and wearable technology enhanced interventions to reduce sedentary behaviour: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2017;14:1–17. 10.1186/s12966-017-0561-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Webb TL, Joseph J, Yardley L, et al. Using the Internet to promote health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. J Med Internet Res 2010;12:e1376. 10.2196/jmir.1376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spahn JM, Reeves RS, Keim KS, et al. State of the evidence regarding behavior change theories and strategies in nutrition counseling to facilitate health and food behavior change. J Am Diet Assoc 2010;110:879–91. 10.1016/j.jada.2010.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions.

- 28.Prochaska JO, Redding CA, Evers KE. The transtheoretical model and stages of change. Health behavior: Theory, research, and practice 2015;97. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bundy C. Changing behaviour: using motivational interviewing techniques. J R Soc Med 2004;97 Suppl 44:43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fenn K, Byrne M. The key principles of cognitive behavioural therapy. InnovAiT 2013;6:579–85. 10.1177/1755738012471029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michie S, Fixsen D, Grimshaw JM, et al. Specifying and reporting complex behaviour change interventions: the need for a scientific method. Implement Sci 2009;4:40. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: following considerable development in the field since 2006, MRC and NIHR have jointly commissioned an update of this guidance to be published in 2019. BMJ 2019;50:587–92. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fjeldsoe B, Neuhaus M, Winkler E, et al. Systematic review of maintenance of behavior change following physical activity and dietary interventions. Health Psychol 2011;30:99. 10.1037/a0021974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Middleton KMR, Patidar SM, Perri MG. The impact of extended care on the long-term maintenance of weight loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2012;13:509–17. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00972.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rigby RR, Mitchell LJ, Hamilton K, et al. The use of behavior change theories in dietetics practice in primary health care: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Acad Nutr Diet 2020;120:1172–97. 10.1016/j.jand.2020.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-058955supp001.pdf (67.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.