Abstract

Objective

To examine the relevance of existing chronic care models to the integration of chronic disease care into primary care services in sub-Saharan Africa and determine whether additional context-specific model elements should be considered.

Design

‘Best fit’ framework synthesis comprising two systematic reviews. First systematic review of existing chronic care conceptual models with construction of a priori framework. Second systematic review of literature on integrated HIV and diabetes care at a primary care level in sub-Saharan Africa, with thematic analysis carried out against the a priori framework. New conceptual model constructed from a priori themes and new themes. Risk of bias of included studies was assessed using CASP and MMAT.

Eligibility criteria

Conceptual models eligible for inclusion in construction of a priori framework if developed for a primary care context and described a framework for long-term management of chronic disease care. Articles eligible for inclusion in second systematic review described implementation and evaluation of an intervention or programme to integrate HIV and diabetes care into primary care services in SSA.

Information sources

PubMed, Embase, CINAHL Plus, Global Health and Global Index Medicus databases searched in April 2020 and September 2022.

Results

Two conceptual models of chronic disease care, comprising six themes, were used to develop the a priori framework. The systematic review of primary research identified 16 articles, within which all 6 of the a priori framework themes, along with 5 new themes: Improving patient access, stigma and confidentiality, patient-provider partnerships, task-shifting, and clinical mentoring. A new conceptual model was constructed from the a priori and new themes.

Conclusion

The a priori framework themes confirm a need for co-ordinated, longitudinal chronic disease care integration into primary care services in sub-Saharan Africa. Analysis of the primary research suggests integrated care for HIV and diabetes at a primary care level is feasible and new themes identified a need for a contextualised chronic disease care model for sub-Saharan Africa.

Keywords: health services research, HIV, primary health care, patient-centered care, diabetes mellitus

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

The health transition taking place in sub-Saharan Africa towards chronic communicable and non-communicable diseases such as HIV and diabetes as the main causes of morbidity and mortality means that health systems currently orientated towards acute, episodic care, must be re-orientated towards meeting the long-term needs of patients with chronic diseases.

Existing chronic care conceptual models were designed for use in high income countries rather than a sub-Saharan African (SSA) context.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

All six of the a priori framework themes derived from the chronic care model and the innovative care for chronic conditions framework were identified within the primary research studies and therefore have relevance to the provision of chronic care in a primary care context in sub-Saharan Africa.

An additional five new themes were identified from the primary research studies: improving patient access, task shifting, clinical mentoring, stigma and confidentiality, and patient–provider partnerships.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

These findings imply that there are additional themes and delivery strategies specific to an SSA context that need to be considered in the implementation of primary care-level integrated chronic disease care provision in sub-Saharan Africa.

The new themes identified from the primary research highlight the importance of health services being accessible and acceptable to patients, of partnering with patients to improve health outcomes, and of patient confidentiality and imply a need to reconceptualise chronic care from a patient-centred viewpoint.

Introduction

Sub-Saharan Africa is experiencing an epidemic of noncommunicable diseases (NCD),1 with deaths from NCD projected to be greater than those resulting from communicable, perinatal, maternal and nutritional causes combined by 2030.2 However, sub-Saharan African (SSA) populations also remain at risk of communicable diseases such as HIV, which continues to be a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in sub-Saharan Africa.3 Therefore, one of the key strategic challenges facing health policymakers in sub-Saharan Africa is how fragmented health systems, traditionally orientated towards addressing acute episodic care, can be strengthened to provide continuity of care and address the burden of chronic communicable and NCDs.4

This growing double burden of disease means that there is an urgent need to move beyond vertical interventions for individual diseases, towards an integrated care approach to healthcare provision for chronic disease of all causes.4 5 Integrated care lacks a single agreed definition, but it describes care that is coordinated rather than episodic and fragmented6 and has been conceptualised as a response to the growing problem of chronic disease and multimorbidity.7 Crucially, people who have chronic disease require sustained engagement with the healthcare delivery system over time8 with continuity of care found to be associated with better outcomes.9

Primary care has been identified by the WHO to be the natural setting for integrated chronic disease care delivery,10 11 with its distinctive attributes of accessibility, comprehensiveness, continuity and person-centredness12 meaning that primary care is well-placed to address the need for longitudinal engagement with patients.8 13 In high income countries integrated chronic disease management in primary care has been implemented based upon the chronic disease care model (CCM) developed by Wagner et al.14 However, as yet, there is no consensus on a model to guide implemetation of integrated chronic disease care in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) in SSA.7 15

The focus of this study is the integration of chronic disease care into primary care services in SSA, with the aim of determining whether existing chronic care models require modification for a SSA context. We build in a user-led definition of integrated care16 to define integrated chronic disease care as the delivery of longitudinal, person-centred, coordinated care, incorporating primary prevention, screening, diagnosis, linkage to care, monitoring, treatment and long-term follow-up4 for chronic diseases in a primary care context with the goal of improving patient outcomes such as markers of disease control, morbidity and mortality.

Due to the double burden of disease in SSA, a relevant model must describe the integration of both chronic communicable and non-communicable disease care into primary care services13 and HIV and diabetes have been selected as representative examples that require ongoing community-based continuity of care.17 Diabetes mellitus represents a growing problem in SSA, with diabetes-related morbidity and mortality in SSA the highest anywhere in the world.18 Diabetes exemplifies the challenges of delivering chronic NCD care as it is characterised by prolonged duration and slow progression requiring life-long engagement with health services for monitoring and treatment.17 19

Methods

The ‘best fit’ framework synthesis (BFFS) method was selected as it provides a systematic and transparent method to identify and build on existing frameworks and models of chronic disease care using primary research data to derive a new model relevant to a SSA context.20 The BFFS method uses both framework and thematic synthesis approaches to analyse complex issues of feasibility and health system implementation.21 The BFFS method has been previously used by Lall et al and Kane et al to adapt existing models of chronic disease care for NCDs in LMIC settings.8 15

The seven steps of the BFFS method were followed for this systematic review20: (1) the review question was formulated; (2) two systematic reviews were conducted (a) to identify existing relevant ‘best fit’ chronic disease care conceptual models and (b) of primary research focusing on integration of HIV and diabetes care at a primary care level in sub-Saharan Africa; (3) results of the systematic reviews were then analysed to (a) construct an a priori framework using thematic analysis and (b) assess primary research study characteristics and quality; (4) study evidence was coded against the a priori framework; (5) any data that could not be placed within the framework was interpreted using inductive, thematic analysis; (6) a new framework was created using both the a priori and new themes identified from the primary research; and (7) further thematic analysis led to the creation of a new conceptual model.

Search strategy

A priori framework

PubMed, Embase, CINAHL plus, Global Health (CABI), and WHO’s Global Index Medicus databases were searched to identify conceptual models or frameworks of chronic disease care for the generation of the a priori framework. Search terms for all databases are included in the supplementary file.

Inclusion criteria were articles in English describing a conceptual model or framework for chronic disease care, developed for application in a primary care context, and describing the long-term management of chronic diseases. We excluded animal models, purely economic models, models describing healthcare workforce roles only, models focusing on a specific aspect of chronic disease care provision such as health promotion, screening, self-care, e-health or telemedicine, or on a population subgroup such as paediatric or elderly care. Models that were an adaption of a pre-existing conceptual model to a specific country or health system context not relevant to sub-Saharan Africa were also excluded. No limits were set on date of publication. Database searches were carried out between 1 and 30 April 2020.

Primary research studies

PubMed, Embase, CINAHL plus, Global Health (CABI), and WHO’s Global Index Medicus were searched for primary research studies, along with grey literature via Google Scholar and analysis of key study bibliographies for relevant studies. The validated broad integrated care search filter for PubMed was incorporated into the search strategy. Search terms are included in the supplementary file.

Articles in English conducted in sub-Saharan African countries, as defined by World Bank Regional Groups, evaluating the implementation of an intervention or programme to integrate HIV and diabetes care located primarily at the primary level of the healthcare service were included.22 Database searches were carried out between 1 and 30 April 2020, with a subsequent search carried out on 1st May 2022 for articles published since the initial search. Articles published between September 2010 and May 2022 were included, to provide relevant data that would reflect the current SSA primary care context.

Analysis

Articles retrieved during each search process were imported into bibliographical management software. Duplicate records were removed, followed by an initial screen of titles and abstracts for relevance. Full-text screening was then carried out, recording reasons for exclusion. Both authors screened and confirmed the final selection of articles for the a priori framework and the primary research studies. Any differences of opinion would have been resolved by seeking a third opinion.

Data quality of the primary research studies was assessed as part of the systematic review. Studies were appraised against the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Checklist (CASP)23 and the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT)24. A study was deemed to be of adequate quality for inclusion if >50% of the CASP and MMAT checklists had been met. All the studies were found to be of adequate quality for inclusion.

Data was then extracted from all included articles into custom-made data extraction sheets, included in the supplementary file. Model elements were extracted from the chronic care models identified and used to build the a priori framework themes to which the primary research studies were mapped. Primary research studies were analysed and coded using the a priori framework themes. Following this, the results of primary research studies which could not be mapped to the a priori framework were thematically analysed and new themes identified.23 24

Results

A priori framework

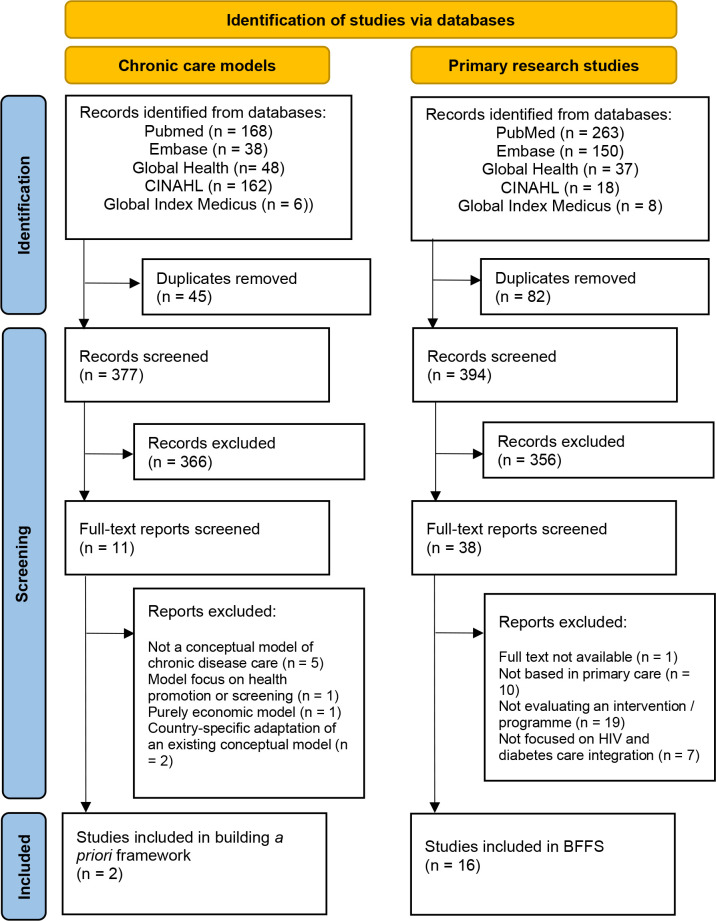

An initial 422 articles were identified, and after removing duplicates, 377 articles were screened by title and abstract with 366 then excluded. The 11 potentially applicable studies describing models or frameworks were then assessed with a further nine excluded, as outlined in figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of search results for models used to construct a priori framework, and primary research studies used for BFFS. Adapted from Page et al.50 BFFS, best fit framework synthesis.

Two models satisfied the inclusion criteria for informing the a priori framework: the CCM14 and the innovative care for chronic conditions framework (ICCCF).25 26 Model elements and building blocks of these models were extracted to inform development of the a priori framework (table 1). The CCM identifies six essential model elements that enable provision of high-quality chronic disease care in a primary care setting.14 27 Each of these model elements can be further described in terms of service delivery components or strategies that enable the implementation of integrated chronic disease care.28 In 2003, several additional service delivery components were added to reflect pilot study results,29 and these were included for analysis. The scope of the ICCCF conceptual model is broader than the CCM, describing micro, meso and macro levels of integration.25 Primary care as a service delivery approach is located at the meso level of integration30; therefore, the meso level building blocks described in the ICCCF were used to inform the a priori framework. Although these meso level building blocks of the ICCCF are based on the six model elements of the CCM and the models overlap significantly in their content,26 both the CCM and ICCCF contain unique service delivery strategies which were valuable to inform the a priori framework themes.

Table 1.

A priori framework themes identified from CCM and ICCCF conceptual models25 27 29

| CCM model element | ICCCF building block | Service delivery strategies | A priori framework themes |

| Delivery system design | Promote continuity and coordination | Defined roles and responsibilities of team members within team.* Care appropriate to cultural background* Clinical case management for complex patients* Promotion of communication within healthcare team to coordinate patient care† Continuity through planned and proactive follow-up to support evidence-based care‡ Coordination of services across levels of healthcare and providers‡ |

1. Effective team-working to deliver continuity and coordinated proactive care. |

| Health System | Encourage quality care through leadership and incentives | Promotion of effective strategies for improvement and system change* Organisational culture and leadership support of improving quality of care‡ Incentivisation of quality care‡ Quality monitoring and improvement activities as a routine among all team members, including processes for review of significant events‡ |

2. Organisational leadership, culture and mechanisms to promote quality and safety. |

| Decision support | Organise and equip healthcare teams | Promotion of continuing professional education* Access to specialist advice* Equipped healthcare teams with necessary supplies, medical equipment, laboratory access and essential medications† Training to help promote patient self-management and support behavioural change† Implementation of ongoing use of evidence-based guidelines and diagnostic and treatment algorithms‡ Effective communication to promote information exchange and patient participation in shared decision-making in evidence-based management‡ |

3. Equipped healthcare teams to deliver evidence-based patient-centred care. |

| Self-management support | Support self-management and prevention | Proactive support for patient’s self-management and prevention efforts over time† Emphasis on central role of patient in managing care‡ Use of effective self-management strategies‡ Organisation of resources to support patient self-management and prevention‡ |

4. Empowerment and support of patients for self-management and prevention. |

| Clinical information systems | Use information systems | Monitoring of team performance* Sharing of information with patients and providers for care coordination* Collection and organisation of useful patient data† Reminder systems for providers and patients‡ Identification of subpopulations for proactive care‡ Use for individual care planning‡ |

5. Use of data collection systems to facilitate effective care and follow-up. |

| Community resources and policies | Building blocks for the community | Encouraging participation of patients in effective community programmes* Raising awareness of chronic conditions and reduce stigma† Providing complementary preventive and management services through mobilising informal network of providers, such as community health workers and volunteers† Mobilisation and coordination of local community resources to support screening, prevention and improved management of chronic conditions† Forming partnerships with community leadership and organisations‡ |

6. Community partnerships to promote awareness, mobilise resources and support health service provision. |

Primary research studies

Database searching retrieved 476 citations, with 394 unique citations after removing duplicates (figure 1). Thirty-eight full-text articles were screened, of which 16 were found to satisfy the inclusion criteria. There were no additional records identified from searches of bibliographies of key articles or of grey literature using Google Scholar. The 16 studies included in the framework synthesis varied by design, with 8 qualitative studies, 7 quantitative studies and 1 mixed methods study identified. The 16 studies were conducted in 9 different SSA countries: South Africa (n=5), Kenya (n=3), Malawi (n=3), Uganda (n=1), Botswana (n=1), Zimbabwe (n=1), Eswatini (n=1); Ethiopia (n=1) and both Tanzania and Uganda (n=1) (see online supplemental table 1).

fmch-2022-001703supp001.pdf (115.6KB, pdf)

Analysis of primary studies against a priori framework themes

The studies were analysed and coded using the a priori framework themes. All a priori themes were identified in at least four studies (see online supplemental table 1).

The a priori theme ‘Effective team-working to deliver continuity and coordinated proactive care’ was included in twelve studies. Several studies highlighted having team members with defined roles as an important strategy for effective teamworking.31–34 Continuity was identified as a particular challenge due to high loss to follow-up rates,31 34 with effective appointment systems found to have an important role in delivering continuity and coordinated care. Patients felt that a rigid and inflexible follow-up appointment system represented a barrier to accessing healthcare,35 while merging follow-up appointment dates for patients with diabetes and HIV comorbidity was identified to be important for improving continuity outcomes.32 36 37

‘Organisational leadership, culture and mechanisms to promote quality and safety’ was included in 6 studies and was identified as a key factor in the success of projects to integrate HIV and diabetes care.32 34 Benefits were found from having a motivated leader to drive change, make key decisions and communicate a vision within the organisation.32 34 Identifying monitoring and evaluation indicators for quality improvement was also highlighted as important for promoting quality and safety. 32 38

‘Equipped healthcare teams to deliver evidence-based patient-centred care’ was a dominant theme, found within 12 of the 16 primary studies, and supporting the ICCCF modification of the original CCM ‘decision support’ model element to include equipping of healthcare teams.25 Common findings from the primary studies were that healthcare facilities lacked basic screening equipment,35 38–40 access to laboratory diagnostic tests38 39 and a reliable supply of diabetes drugs.35 38 39 41 The development and implementation of local and national evidence-based guidelines and diagnostic and treatment algorithms were found to be important for improving patient care.31 32 38 39 Several studies highlighted clinical mentorship as a method of providing continuing professional education.32 34 38 39 42

‘Empowerment and support of patients for self-management and prevention’ was a theme identified in 9 of the primary research studies. Self-management was mainly supported through the delivery of health education to patients,35 38–40 43 such as a programme to empower patients with diabetes to take responsibility for their health through education about glycaemic control.32 From a patient perspective, participants in a South African study emphasised the importance of trusting relationships between patients and healthcare workers to facilitate effective clinic-based support for self-management.36

‘Use of data collection systems to facilitate effective care and follow-up’ was identified as a theme present in 6 studies. Integration of HIV and NCD patient data into a single, easily accessible patient file was found to facilitate patient data collection for clinical decision-making and monitoring and evaluation activities to improve team performance.32 34 38 39 42 Specific, detailed patient records were identified as enabling nursing staff to improve longitudinal follow-up, quantification of patient demand and accurate medication ordering.32 44

‘Community partnerships to promote awareness, mobilise resources and support health service provision’ was a theme identified in four studies. In Malawi, community health volunteers were mobilised for HIV and NCD patient support in clinics and in the community,39 and in Uganda, local staff were employed to facilitate a screening campaign.45 Support from local community leadership was also suggested as a way to increase screening uptake in hard-to-reach populations.45

Identification of new themes from primary study thematic analysis

Thematic analysis of results of primary research studies which could not be mapped to the a priori framework identified five new themes.

Improving patient access to chronic disease care

A new theme that emerged from 11 of the studies was that of improving patient access to chronic disease care. Barriers to patient access were long distances to travel to clinic, a lack of public transport, low vehicle ownership,34 35 45 a loss of income resulting from time away from the workplace, very long waiting times, and separate appointments for those with more than one chronic disease.35 36 41 42 46 Several studies identified the need for decentralisation of chronic care to primary care level to reduce travel time and costs.32 34 45 47 Three studies considered interventions to reduce waiting times and increase the flexibility of appointment systems.34 43 44 To remove the financial barrier of out-of-pocket expenditure, free care and medications were provided at the projects in Malawi and Zimbabwe.32 34

Task shifting

Eight studies highlighted task shifting as an important strategy for the delivery of integrated HIV and diabetes care in sub-Saharan Africa.31 32 34 39 42–44 47Going beyond implementing defined team roles, task shifting describes a strategy of transferring tasks to healthcare workers with shorter training and fewer qualifications, or to a healthcare cadre trained specifically to perform a limited task only, with the aim of improving service efficiency and accessibility in resource-constrained settings where physician numbers are low.48 Task shifting was identified as an important factor in delivering decentralised integrated chronic care, with several studies advocating the delegation of administrative tasks and screening to non-clinician healthcare cadres34 39 and chronic care management to primary care nurses, nurse aides and non-clinician health educators.32 43 44

Clinical mentoring

Clinical mentoring is a strategy that has been endorsed by the WHO for supporting the scale-up of HIV care in resource-constrained settings28 and has a wide scope beyond providing continuing professional education. In 5 of the primary studies, clinical mentorship was used as a strategy to train, retrain and support healthcare workers for HIV and diabetes care to facilitate task shifting, decentralisation of services and capacity building, as well as providing continuing professional development, assessment and supervision.32 34 38 39 41

Stigma and confidentiality

The theme of stigma and confidentiality was found in 8 of the primary research studies. This new theme goes beyond the ICCCF-derived service delivery strategy of raising awareness of chronic conditions and reducing stigma in the community, to highlight the fundamental importance of considering stigma and confidentiality in the design of primary care services and the ongoing support of patients with stigmatising conditions. Both HIV and diabetes were reported by patients to be stigmatising conditions.36 43 Fear of stigma arising from these conditions was identified by several studies to be an important concern for patients, affecting their willingness to access care.34 35 41 45 47 Conversely, confidentiality was found to be key in allowing HIV patients to feel comfortable to join an integrated NCD and HIV medication adherence club.42 43 Patients and healthcare workers felt that integrated HIV and NCD treatment reduced the stigma of HIV by treating it as any other chronic condition.43

Patient–provider partnerships

Patient–provider partnerships is a them identified in 6 of the primary studies and incorporates patient feedback, patient experiences and expectations of care, and patient involvement and consultation in service planning. Patients reported a power imbalance between patients and healthcare workers, feeling they lacked the power to ask questions.36 Matima et al suggested that the healthcare worker–patient relationship needed to be rebalanced to improve patient satisfaction and quality of care.36 Similarly, Ameh et al noted a provider–patient disconnect with patients expressing dissatisfaction about the behaviour of clinic staff and a lack of trust in their management, leading to the suggestion that assessment of quality of care should incorporate the user’s experience.35 Wroe et al involved patients in the initial planning for their project, Frieden et al in the development of locally adapted chronic disease guidelines, and Birungi et al in project meetings.32 34 41 Venables et al advised that to ensure services are acceptable to patients, it is important to involve people living with chronic diseases in their design to advise on adaptation to local needs and context.43

Expanded thematic framework

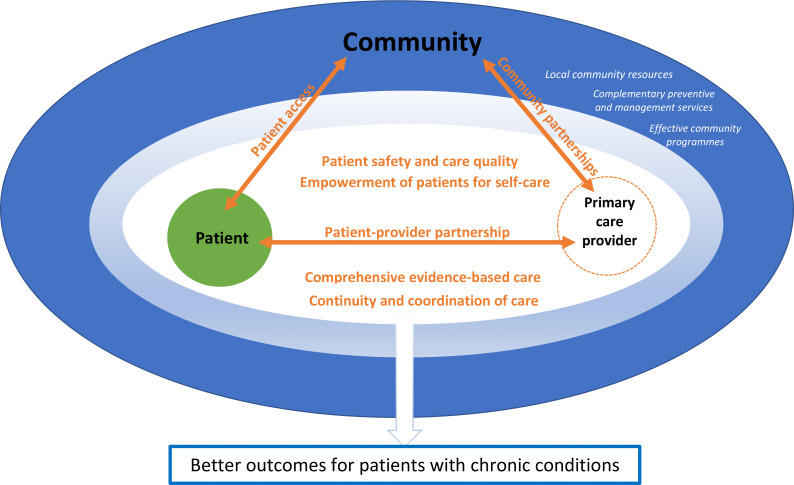

The five new themes identified from the primary studies and the six a priori themes confirmed from analysis of the primary research studies were combined to create a new expanded thematic framework, as detailed in table 2. The new conceptual model has seven components: improve patient access to care; foster patient–provider partnerships; ensure patient safety and care quality; empower patients for self-care; support delivery of comprehensive evidence-based care; implement effective care, continuity and coordination; and develop community partnerships. The seven model components are further formulated to demonstrate a person-centred approach, with the conceptual model visualised as in figure 2.

Table 2.

New chronic care model for integrated primary care of HIV and diabetes in sub-Saharan Africa

| Model component | Person-centred formulation | Healthcare service delivery strategies | Themes from expanded thematic framework |

| Improve patient access to care. | ‘I am able to access the chronic disease care I need’. | Routine chronic care delivery is decentralised to a primary care level to improve patient access. Streamlined and coordinated processes are developed and implemented to improve efficiency of patient services. Available healthcare staff are effectively used through rational shifting of tasks and have clearly defined roles and responsibilities for delivering integrated chronic care. Strategies to reduce patient out-of-pocket expenditure for care and medications are developed. |

New theme of ‘patient access’ New theme of ‘task shifting’ |

| Foster patient–provider partnerships. | ‘I partner with my healthcare worker to improve my health’. | Patient–healthcare worker communication that facilitates information exchange and shared decision-making is developed and encouraged. Healthcare worker training promotes the importance of patient-centred chronic care. Service design and implementation safeguard patient confidentiality and seeks to reduce chronic disease stigma. Patients are consulted and involved in the planning and implementation of healthcare services. Effective avenues of feedback are provided for patient suggestions, concerns and complaints. Care provided is appropriate to the patient’s cultural background. |

New theme of ‘patient–provider partnerships’ New theme of ‘stigma and confidentiality’ A priori theme of ‘effective team-working to deliver continuity and coordinated proactive care’ |

| Ensure patient safety and care quality. | ‘I receive safe, high-quality healthcare’. | Organisational leadership develops a culture that supports and promotes the improvement in quality of patient care. Effective strategies are promoted for improving the quality of patient care. Information for monitoring and evaluation of team performance is collected and used to drive improvements in patient care. Providing quality care for patients is incentivised. Quality monitoring and improvement activities are routine among all team members. Processes are in place for the review of significant events to improve patient safety. |

A priori theme of ‘organisational leadership, culture and mechanisms to promote quality and safety’ A priori theme of ‘use of data collection systems to facilitate effective care and follow-up’ |

| Empower patients for self-care. | ‘I am empowered with the information and resources to manage my health’. | Patients are empowered to take a central role in managing their care. Proactive support is provided for patient self-management and prevention efforts over time. Effective self-management strategies are provided to patients. Suitable resources are provided to support patient self-management and health prevention. |

A priori theme of ‘empowerment and support of patients for self-management and prevention’ |

| Support delivery of comprehensive evidence-based care | ‘My healthcare worker has the resources, knowledge and support to provide me with comprehensive evidence-based chronic disease care’ | Healthcare teams are equipped with necessary supplies, medical equipment, laboratory access and essential medications. Guidelines and diagnostic and treatment algorithms are implemented to support delivery of evidence-based chronic disease care. Healthcare workers have access to specialist advice. Support, education, training and retraining are delivered through programmes such as clinical mentoring to facilitate decentralisation of chronic disease care. Training for healthcare workers is provided to help promote patient self-management and support behavioural change. |

A priori theme of ‘equipped healthcare teams to deliver evidence-based patient-centred care’ New theme of ‘clinical mentoring’ |

| Implement effective care, continuity and coordination | ‘My healthcare worker has access to my health information to advise me effectively and to plan and coordinate my ongoing care’. | Useful patient data are collected, organised, stored securely and are accessible to guide patient care. Continuity is delivered through planned and proactive follow-up to support evidence-based care for chronic diseases. Reminder systems are in place for providers and patients. Data are used to identify subpopulations for proactive care. Data are used for individual care planning. Clinical case management is implemented to meet the needs of complex patients. Patient care is coordinated through effective communication and sharing of information between team members as well as between healthcare providers. |

A priori theme of effective team-working to deliver continuity and coordinated proactive care A priori theme of use of data collection systems to facilitate effective care and follow-up New theme of ‘stigma and confidentiality’ |

| Develop community partnerships | ‘My healthcare provider partners with my community to raise awareness, develop services, and increase support for chronic disease care’. | Community awareness of chronic conditions is raised to reduce stigma. Partnerships are formed with community leadership and organisations to support patient access to healthcare. Local community resources are identified and mobilised to support screening, prevention and improved management of chronic conditions. Complementary preventative and management services are provided where possible through mobilising an informal network of providers, such as community health workers and volunteers. Patients are encouraged to take part in effective community programmes. |

A priori theme of ‘community partnerships to promote awareness, mobilise resources and support health service provision’ |

Figure 2.

New conceptual model for delivering integrated primary care for chronic diseases incorporating the seven new model components. Italic text: community resources outside of primary care.

Discussion

This study has identified chronic care models from which an a priori framework for a chronic care model was produced. Primary research studies investigating integration of HIV and diabetes primary care in sub-Saharan Africa were mapped to the a priori framework, with new themes identified leading to construction of a novel conceptual model with a person-centred formulation.

The new themes identified from the primary research studies of ‘confidentiality and stigma’, ‘patient–provider partnerships’ and ‘improving patient access’ underline the importance of implementing services which are both acceptable and accessible to patients. These themes have at their heart the real-life struggles and concerns of many patients in sub-Saharan Africa and indicate a need for a reconceptualisation of CCMs of service delivery from an end-user perspective. The new model incorporates these new themes identified from the primary studies but also reorientates the a priori themes and service delivery components derived from the CCM and ICCCF to be more person-centred in their formulation (table 2). Task shifting and clinical mentoring are included in the model as key service delivery strategies identified from the primary studies for the contextualisation and practical implementation of a model that delivers person-centred HIV and diabetes care in a resource-constrained SSA setting.

The first aim of the person-centred formulation of the new conceptual model is to provide clarity regarding the aims of the model to policymakers and stakeholders, as well as to the leadership of chronic care programmes and healthcare workers within these programmes. The person-centred framing allows linkage of the model components to their outcomes for patients and therefore the reasons for implementing the service delivery strategies to achieve the component goal. If an understanding of the model of care is included within healthcare worker training, this may help with buy-in and motivation for integrated care activities, a problem which was identified in several primary studies as compromising implementation of integrated care.32 34 35 The second aim of the reframing is to incorporate the distinctive attributes of primary care, which are access, comprehensiveness, continuity and person-centeredness.12 This links the model to primary care and underlines its importance as a service delivery approach for provision of integrated, people-centred health services.17

The new model envisages a patient–provider partnership at the heart of chronic disease care, delivering person-centred care that takes account of patient concerns and preferences to create an acceptable service that patients will want to utilise. Chronic disease care is decentralised, with the primary care provider located within the community to improve patient access. Better outcomes for patients with chronic diseases are achieved by initiatives to increase access to care and deliver the model components through the implementation of the service delivery strategies by the primary care provider. The second partnership is between the primary care provider and the community, to mobilise resources for chronic disease care that patients can access to improve their health outcomes (figure 2).

The a priori themes derived from the CCM and ICCCF models confirm a need to move away from acute, episodic care towards coordinated and longitudinal care spanning the whole life course.4 17 Analysis of the primary research studies suggests that integrated care of HIV and diabetes at a primary care level is feasible in a SSA context and can potentially bring benefits such as system synergies from building on established programmes and protocols,32 38 42 stigma reduction,37 43 47 and increased access to care.34 37 42

Each of the a priori themes were identified within studies from at least four different SSA countries, suggesting that common challenges exist between SSA countries relating to chronic disease care integration, and that the new model for chronic disease care could have relevance across SSA countries. Five of the seven new model components are derived from the original six a priori framework themes, although they have been reframed and the service delivery strategies reordered to indicate the importance of the component to the end user through the inclusion of a person-centred formulation (table 2).

‘Implement effective care, continuity and coordination’ is based on the a priori themes of ‘effective team working’ and ‘use of data collection systems’. The collection of patient data and effective team-working are presented as key strategies to allow continuity in clinical decision-making, care-planning and follow-up, as well as the coordination of care, where continuity has been shown to improve patient outcomes.9 Data security has also been added into this component incorporating an aspect of the new theme of stigma and confidentiality.34

The ‘equipped healthcare teams’ a priori theme has been reframed as ‘support comprehensive evidence-based patient care’ to indicate that the aim in adequately equipping health teams with resources, knowledge and specialist support, is to deliver comprehensive and evidence-based chronic disease care in a primary care setting.49 This component also now includes the strategy of clinical mentoring as an approach to facilitate decentralisation, task shifting and capacity building in sub-Saharan Africa where distance, terrain and lack of healthcare staff pose challenges to equipping staff with knowledge and support.28

‘Patient safety and care quality’ is similar to the a priori theme of organisational leadership, culture and mechanisms to promote quality and safety. This component addresses concerns about the quality of primary care provision in sub-Saharan Africa12 through advocating implementation of robust monitoring and evaluation processes, an important strategy to drive improvement in the quality of patient care.

Delivery of primary care has been envisaged to involve partnering with people in managing their own health and that of their community.49 Two new model components address these goals. The first is ‘develop community partnerships’, corresponding to the a priori framework theme of community partnerships to promote awareness, mobilise resources and support health service provision. Similar to the patient–provider partnership, the community–provider partnership is envisaged as a two-way relationship whereby the community is consulted regarding local health needs and implementation of services, and the community contributes resources, complementary preventative and management services and human resources to strengthen delivery of chronic disease care.25 The second model component of ‘patient empowerment for self-care’ is similar to the a priori theme of empowerment and support of patients, relating to the important role of the healthcare provider in the empowerment of patients for chronic disease self-care. This is facilitated primarily through the patient–provider partnership allowing delivery of patient-centred education and the provision of appropriate resources, as well as through partnering with community-based informal providers such as health educators and peer-led support groups.25

The new themes identified from the primary studies further adapt the new conceptual model for a SSA context. The component ‘improve patient access to care’ was derived from the new theme of ‘patient access’. First contact accessibility is a key attribute of primary care,12 but healthcare workforce shortages, out-of-pocket expenditure and travel distances to health facilities represent significant barriers to patient access to care in sub-Saharan Africa which particularly adversely affect patients with chronic diseases who have ongoing, long-term needs for monitoring, medication and follow-up.4 13 The model addresses access to care through advocating decentralisation of primary care services and streamlining of processes involved in attending appointments to reduce waiting and travel times and associated indirect costs to patients. Task shifting is a strategy identified from the primary research studies to support improvements in patient access and streamlining of services through the effective use of the limited healthcare workforce in sub-Saharan Africa44 48 Out-of-pocket expenditure is addressed through advocating strategies to reduce the direct costs of healthcare, ideally through government financing initiatives, but also through partnering with NGOs and donor organisations where feasible.32 34

The new model component of patient–provider partnerships addresses acceptability of healthcare provision to patients and focuses on developing person-centred services, incorporating good communication, acknowledgement of patient concerns and preferences, and involvement of patients in decision-making for their care. These elements have the aim of fostering enduring trusting personal relationships to positively impact care and outcomes.36 40 Giving patients a voice in decision-making about their care through feedback about their concerns or complaints, as well as by involvement in identifying local health priorities and the design and implementation of health services, is consistent with the WHO’s vision of person-centred primary healthcare.5 49 The new theme of confidentiality and stigma derived from the primary studies and the service delivery approach of ‘care appropriate to cultural background’ also feature in this component as service delivery strategies. These aim to improve the acceptability and uptake of services, through their design and implementation to be culturally sensitive, protect confidentiality and reduce chronic disease stigma.37

It is acknowledged that sub-Saharan Africa is incredibly diverse, politically, socially and economically, with significant differences between health systems. The scope of this study is defined to be primary care as a service delivery approach, and as such does not attempt to address the ‘macro’ level issues in sub-Saharan Africa such as policy environment, economic, health system or political factors. This conceptual model therefore represents the key elements found to be significant for implementing delivery of chronic disease care services at a primary care level in SSA, derived from the available primary research conducted in SSA and from existing chronic care models. The model is not intended to be prescriptive and will require contextualisation to the many differing political, social and economic environments, but could act as a guide, based on what is known from the available studies from SSA.

Limitations of study

There are several limitations to this study. The geographic coverage of the primary studies does not represent any countries in west or central SSA, potentially limiting the generalisability of the new model for the whole of SSA. The BFFS method relies on availability of primary research studies, and as there have been relatively few studies examining the integration of HIV and diabetes care in SSA37; it is possible that there are important themes for implementation of integrated chronic disease care in SSA that have not been identified. The inclusion of only one NCD will have further limited the number of studies returned by the primary study systematic search. Additionally, the selection of diabetes may mean that there are themed derived from the primary studies which are specific for diabetes care and could be less relevant to other NCDs, and conversely, that important themes for care of other NCDs have been overlooked. It is also possible that publication bias may lead to failed integration projects not being published, and therefore not included for analysis. The lack of dissonance between the primary studies could be seen as evidence of this, although some studies did record negative findings from implementation projects.20 32 35 39 Additionally, this study, although outside its stated scope, does not consider policy environment and economic factors that will have a huge influence on the implementation of any model of chronic disease care in sub-Saharan Africa.25 26

Conclusion

Implementing high-quality chronic disease care in a sustainable way requires moving beyond vertical disease programmes towards integrated healthcare systems, primarily through prioritising investment in primary care. Investing in primary care infrastructure and the healthcare workforce to support decentralisation, and access to person-centred high-quality care for HIV and diabetes, will improve patient outcomes and enable more patients with chronic diseases to lead healthy productive lives. Methods of using and training the current healthcare workforce, such as task shifting and clinical mentoring, can also help to deliver efficient and effective care for patients. This study adds to the available evidence for integrated models of chronic disease care in sub-Saharan Africa by building on relevant pre-existing conceptual models, using primary research studies on integration of HIV and diabetes care to develop a new conceptual model relevant to the challenges faced in implementing chronic disease care in sub-Saharan Africa. Implementing an integrated model of chronic care that has at its heart the needs and concerns of patients is anticipated to increase utilisation of chronic care services, improve chronic disease care outcomes and ultimately contribute towards achieving the goal of providing universal high-quality healthcare for all.

Footnotes

Contributors: SRH: conception and design of work; acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting and revising work; final approval of version to be published. AMJ: design of work; interpretation of data; drafting and revising work; final approval of version to be published; responsible for overall content as guarantor.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Nyirenda MJ. Non-Communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: understanding the drivers of the epidemic to inform intervention strategies. Int Health 2016;8:157–8. 10.1093/inthealth/ihw021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 2006;3:e442. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators . Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 2020;396:1204–22. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beaglehole R, Epping-Jordan J, Patel V, et al. Improving the prevention and management of chronic disease in low-income and middle-income countries: a priority for primary health care. Lancet 2008;372:940–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61404-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Druetz T. Integrated primary health care in low- and middle-income countries: a double challenge. BMC Med Ethics 2018;19:48. 10.1186/s12910-018-0288-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.RAND Europe . National Evaluation of the Department of Health’s Integrated Care Pilots, 2012. Available: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/2012/RAND_TR1164.pdf [Accessed 16 Sep 2022]. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Mounier-Jack S, Mayhew SH, Mays N. Integrated care: learning between high-income, and low- and middle-income country health systems. Health Policy Plan 2017;32:iv6–12. 10.1093/heapol/czx039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lall D, Engel N, Devadasan N, et al. Models of care for chronic conditions in low/middle-income countries: a 'best fit' framework synthesis. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e001077. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Servellen G, Fongwa M, Mockus D'Errico E. Continuity of care and quality care outcomes for people experiencing chronic conditions: a literature review. Nurs Health Sci 2006;8:185–95. 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2006.00278.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO . Technical series on primary health care. integrating health services brief, 2018WHO. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/326459/WHO-HIS-SDS-2018.50-eng.pdf 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO . Integrated care models: an overview, 2016. Available: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/322475/Integrated-care-models-overview.pdf [Accessed 16 Sep 2022]. 10.1155/2013/409083 [DOI]

- 12.Bitton A, Ratcliffe HL, Veillard JH, et al. Primary health care as a foundation for strengthening health systems in low- and middle-income countries. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32:566–71. 10.1007/s11606-016-3898-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rabkin M, El-Sadr WM. Why reinvent the wheel? Leveraging the lessons of HIV scale-up to confront non-communicable diseases. Glob Public Health 2011;6:247–56. 10.1080/17441692.2011.552068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q 1996;74:511–44. 10.2307/3350391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kane J, Landes M, Carroll C, et al. A systematic review of primary care models for non-communicable disease interventions in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Fam Pract 2017;18:46. 10.1186/s12875-017-0613-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Voices . A narrative for person-centred coordinated care., 2013National Voices. Available: https://www.nationalvoices.org.uk/sites/default/files/public/publications/narrative-for-person-centred-coordinated-care.pdf 10.1038/s41586-019-1200-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO . Who global strategy on People-Centred and integrated health services, 2015. Available: https://www.who.int/servicedeliverysafety/areas/people-centred-care/global-strategy/en/ [Accessed 04 May 2020].

- 18.International Diabetes Federation . IDF diabetes atlas, 9th edition, 2019. Available: https://www.diabetesatlas.org/upload/resources/material/20200302_133351_IDFATLAS9e-final-web.pdf [Accessed 16 Sep 2022]. 10.1186/1471-2288-9-59 [DOI]

- 19.Allotey P, Reidpath DD, Yasin S, et al. Rethinking health-care systems: a focus on chronicity. Lancet 2011;377:450–1. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61856-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carroll C, Booth A, Leaviss J, et al. "Best fit" framework synthesis: refining the method. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:37. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flemming K, Booth A, Garside R, et al. Qualitative evidence synthesis for complex interventions and Guideline development: clarification of the purpose, designs and relevant methods. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e000882. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Bank . World bank country and lending groups, 2020. Available: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups [Accessed 03 May 2020].

- 23.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme . Casp Qualitatitve checklist, 2018. Available: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- 24.Hong Q, Pluye P, Fabregues S. Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT). Available: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- 25.WHO . Innovative care for chronic conditions: building blocks for action, 2002. Available: https://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/icccreport/en/ [Accessed 07 May 2020].

- 26.Epping-Jordan JE, Pruitt SD, Bengoa R, et al. Improving the quality of health care for chronic conditions. Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13:299–305. 10.1136/qshc.2004.010744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, et al. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff 2001;20:64–78. 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.WHO . Who recommendations for clinical mentoring to support scale-up of HIV care, antiretroviral therapy and prevention in resource-constrained settings, 2006. Available: https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/clinicalmentoring.pdf [Accessed 01 June 2020].

- 29.Improving Chronic Illness Care Program, . The chronic care model: improving chronic illness care, 2003. Available: http://www.improvingchroniccare.org/index.php?p=Model_Elements&s=18 [Accessed 03 Sep 2020].

- 30.Brown LJ, Oliver-Baxter J. Six elements of integrated primary healthcare. Aust Fam Pract 2016;45:149–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edwards JK, Bygrave H, Van den Bergh R, et al. Hiv with non-communicable diseases in primary care in Kibera, Nairobi, Kenya: characteristics and outcomes 2010-2013. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2015;109:440–6. 10.1093/trstmh/trv038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frieden M, Zamba B, Mukumbi N, et al. Setting up a nurse-led model of care for management of hypertension and diabetes mellitus in a high HIV prevalence context in rural Zimbabwe: a descriptive study. BMC Health Serv Res 2020;20:486. 10.1186/s12913-020-05351-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rawat A, Uebel K, Moore D, et al. Integrated HIV-Care into primary health care clinics and the influence on diabetes and hypertension care: an interrupted time series analysis in free state, South Africa over 4 years. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018;77:476–83. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wroe EB, Kalanga N, Mailosi B, et al. Leveraging HIV platforms to work toward comprehensive primary care in rural Malawi: the integrated chronic care clinic. Healthc 2015;3:270–6. 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2015.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ameh S, Klipstein-Grobusch K, D'ambruoso L, et al. Quality of integrated chronic disease care in rural South Africa: user and provider perspectives. Health Policy Plan 2017;32:257–66. 10.1093/heapol/czw118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matima R, Murphy K, Levitt NS, et al. A qualitative study on the experiences and perspectives of public sector patients in Cape town in managing the workload of demands of HIV and type 2 diabetes multimorbidity. PLoS One 2018;13:e0194191. 10.1371/journal.pone.0194191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duffy M, Ojikutu B, Andrian S, et al. Non-Communicable diseases and HIV care and treatment: models of integrated service delivery. Trop Med Int Health 2017;22:926–37. 10.1111/tmi.12901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rabkin M, Melaku Z, Bruce K, et al. Strengthening health systems for chronic care: Leveraging HIV programs to support diabetes services in Ethiopia and Swaziland. J Trop Med 2012;2012:1–6. 10.1155/2012/137460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Angwenyi V, Aantjes C, Bunders-Aelen J, et al. Context matters: a qualitative study of the practicalities and dilemmas of delivering integrated chronic care within primary and secondary care settings in a rural Malawian district. BMC Fam Pract 2020;21:101. 10.1186/s12875-020-01174-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davis S, Patel P, Sheikh A, et al. Adaptation of a general primary care package for HIV-infected adults to an HIV centre setting in Gaborone, Botswana. Trop Med Int Health 2013;18:328–43. 10.1111/tmi.12041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Birungi J, Kivuyo S, Garrib A, et al. Integrating health services for HIV infection, diabetes and hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa: a cohort study. BMJ Open 2021;11:e053412. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wroe EB, Kalanga N, Dunbar EL, et al. Expanding access to non- communicable disease care in rural Malawi : outcomes from a retrospective cohort in an integrated NCD – HIV model.. BMJOpen 2020;10:e036836. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-036836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Venables E, Edwards JK, Baert S, et al. "They just come, pick and go." The Acceptability of Integrated Medication Adherence Clubs for HIV and Non Communicable Disease (NCD) Patients in Kibera, Kenya. PLoS One 2016;11:e0164634. 10.1371/journal.pone.0164634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khabala KB, Edwards JK, Baruani B, et al. Medication adherence clubs: a potential solution to managing large numbers of stable patients with multiple chronic diseases in informal settlements. Trop Med Int Health 2015;20:1265–70. 10.1111/tmi.12539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chamie G, Kwarisiima D, Clark TD, et al. Leveraging rapid community-based HIV testing campaigns for non-communicable diseases in rural Uganda. PLoS One 2012;7:e43400. 10.1371/journal.pone.0043400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gausi B, Berkowitz N, Jacob N, et al. Treatment outcomes among adults with HIV/non-communicable disease multimorbidity attending integrated care clubs in Cape town, South Africa. AIDS Res Ther 2021;18:72. 10.1186/s12981-021-00387-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Godongwana M, De W-billingsN, Milovanovic M. The comorbidity of HIV hypertension and diabetes : a qualitative study exploring the challenges faced by healthcare providers and patients in selected urban and rural health facilities where the ICDM model is implemented in South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res 2021;3:1–15. 10.1186/s12913-021-06670-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.WHO . Task shifting to tackle health worker shortages global recommendations and guidelines, 2008. Available: https://www.who.int/healthsystems/task_shifting/TTR_tackle.pdf?ua=1 [Accessed 01 June 2020].

- 49.WHO . World Health Report 2008 “Primary Health Care : Now More Than Ever”, 2008. Available: https://www.who.int/whr/2008/en/ [Accessed 18 Feb 2020].

- 50.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

fmch-2022-001703supp001.pdf (115.6KB, pdf)