Abstract

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) is a rare, uniformly fatal prion disease. Although CJD commonly presents with rapidly progressive dementia, ataxia, and myoclonus, substantial clinicopathological heterogeneity is observed in clinical practice. Unusual and predominantly cognitive clinical manifestations of CJD mimicking common dementia syndromes are known to pose as an obstacle to early diagnosis and prognosis. We report a series of three patients with probable or definite CJD (one male and two females, ages 52, 58 and 68) who presented to our tertiary behavioral neurology clinic at Mayo Clinic Rochester that met criteria for a newly defined progressive dysexecutive syndrome. Glucose hypometabolism patterns assessed by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) strongly resembled those of dysexecutive variant of Alzheimer’s disease (dAD). However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated restricted diffusion in neocortical areas and deep nuclei, while cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers indicated abnormal levels of 14-3-3, total-tau, and prion seeding activity (RT-QuIC), establishing the diagnosis of CJD. Electroencephalogram (EEG) additionally revealed features previously documented in atypical cases of CJD. This series of clinical cases demonstrates that CJD can present with a predominantly dysexecutive syndrome and FDG-PET hypometabolism typically seen in dAD. This prompts for the need to integrate information on clinical course with multimodal imaging and fluid biomarkers to provide a precise etiology for dementia syndromes. This has important clinical implications for the diagnosis and prognosis of CJD in the context of emerging clinical characterization of progressive dysexecutive syndromes in neurogenerative diseases like dAD.

Keywords: Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, dysexecutive syndrome, FDG-PET, atypical dementia, behavioral neurology

1. Introduction

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) is a uniformly fatal prion neurodegenerative disease, and its common clinical features include rapidly progressive dementia, ataxia and myoclonus [1]. However, CJD is characterized by a broader spectrum of clinicopathological entities, as exemplified by the myriad of unusual clinical presentations encountered in clinical practice [2]. This substantial heterogeneity may confound recognition and accurate diagnosis of CJD at an early stage, potentially leading to unnecessary testing, suboptimal management of symptoms, and inaccurate counselling for patients and family members. This is especially true when patients present with features mimicking common age-related neurodegenerative diseases primarily degrading higher-level cognitive functions that are more likely to be encountered in clinical settings.

We report three atypical cases of probable/definite CJD who presented with a predominant dysexecutive syndrome and showed a pattern of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) hypometabolism highly reminiscent of a recently characterized clinical phenotype of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) initially and predominantly targeting core executive functions (dysexecutive AD or dAD) [3]. We then discuss the clinical implications surrounding this atypical presentation of CJD and potential avenues to disambiguate the diagnostic conundrum between this syndrome and common neurodegenerative diseases such as dAD.

2. Participants and methods

2.1. Patient selection and diagnosis

Cases came from the practice of DTJ, VKR and DAD and were selected based on probable/definite CJD diagnosis, predominant dysexecutive presentation, and availability of FDG-PET. Clinical diagnoses were assigned by an experienced behavioral neurologist following a clinical interview and a neurological examination. Patients were administered the Kokmen Short Test of Mental Status (STMS) [4], which is a bedside cognitive test [5]. CJD etiology was assessed through a combination of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) protein (14-3-3, total-tau) levels and real-time quaking induced conversion (RT-QuIC) assay performed via the National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center (NPDPSC: Case Western, Cleveland, Ohio). CSF neuron-specific enolase (NSE) levels were measured within Mayo Clinic Laboratories (Rochester, MN). Post-mortem examination was performed in one of the three patients by the NPDPSC through Western blot, histopathology, and immunochemistry. Medical records were reviewed to additionally collect information related to imaging results (FDG-PET, electroencephalogram (EEG), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)).

2.2. Neuroimaging

MRI images were acquired at 3T and included a combination structural T2-weighted, diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and fluid attenuation inversion recovery (FLAIR) acquisition sequences.

FDG-PET images were acquired using a PET/CT scanner (GE Healthcare). Patients were injected with FDG in a dimly lit room and waited for a 30-minutes uptake period. FDG scans lasted 8 minutes, separated into four 2-minutes dynamic frames following a low-dose CT transmission scan. Images were processed through CortexID software. Standardized uptake value ratios (SUVRs) were calculated by normalizing regional glucose uptake to the pons and were compared with an age-segmented normative database using Z scores.

EEG evaluations consisted of 30–60-minute recordings with a 19-channel digital EEG machine with standard activating procedure. The standard ‘10–20 System’ procedure was used for the positioning of electrodes.

3. Results

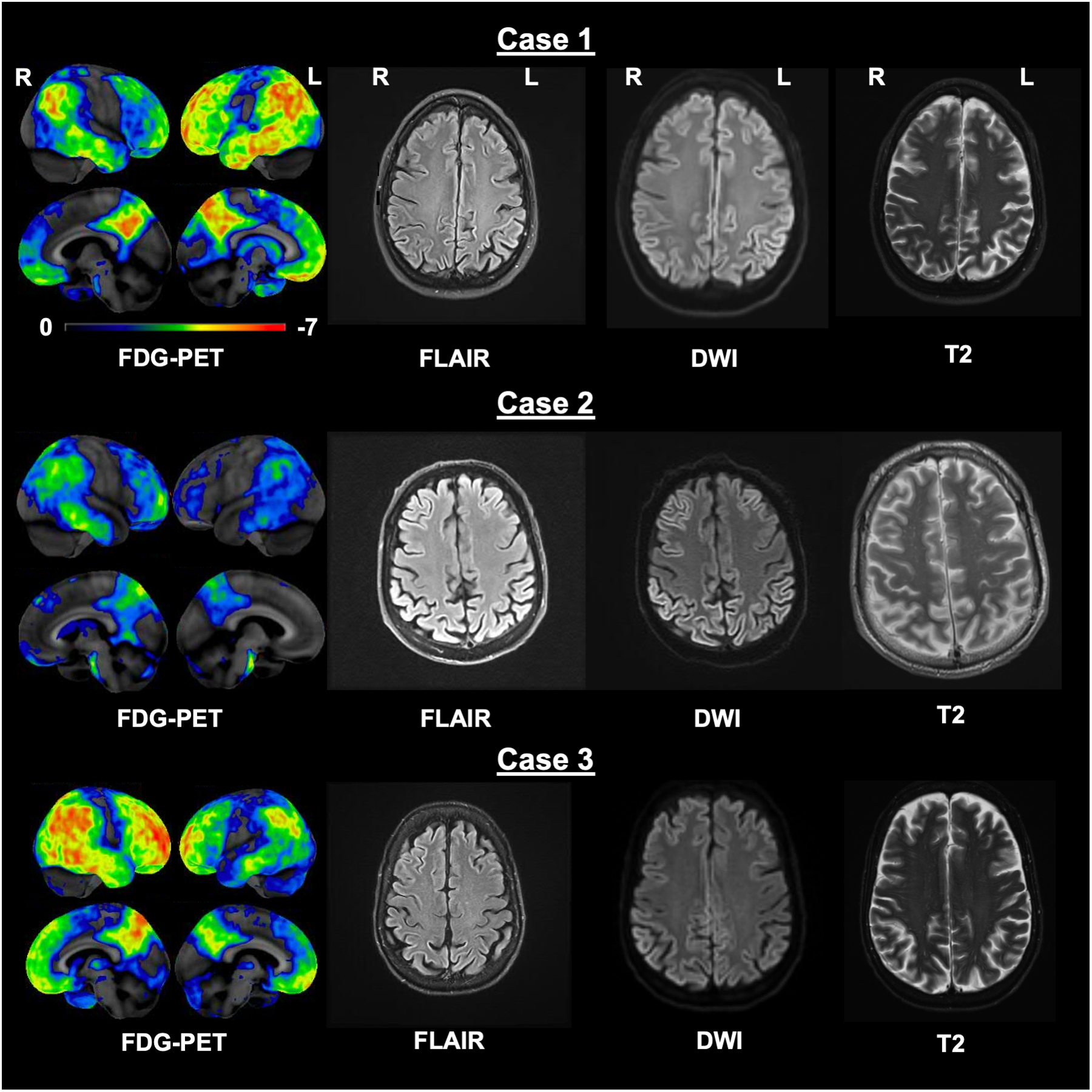

FDG-PET and MRI findings are displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Whole-brain FDG-PET and axial MRI (FLAIR, DWI, T2; left to right) images for all three CJD cases. FDG-PET images were processed using Cortex ID, GE Healthcare with Z-scores ranging from 0 to −7. FDG-PET findings highlighted bilateral yet asymmetric, marked hypometabolism in the posterior parietal (including the posterior cingulate), frontal and temporal areas, whereas FLAIR, DWI and T2 demonstrate clear hyperintensity and restricted diffusion in the parietal lobes. Images are displayed in radiologic convention. FDG-PET = 18Fluorodeoxyglucose-Positron emission tomography; MRI = Magnetic resonance imaging; FLAIR = Fluid attenuated inversion recovery; DWI = Diffusion-weighted imaging.

3.1. CJD case 1

The first case was a 52-year-old right-handed woman. She reported a 6-to-12-month history of cognitive decline which initially presented as problems with short-term memory and performing tasks under executive control which were sufficient to require her to stop working as a nurse. This also manifested in difficulties managing her medication at home, following instructions while cooking and driving under executive control. This caused her to stop all these activities which were eventually assumed by her husband. She also reported halting speech, more clumsiness on the right side than the left side, jerky movements at night, balance problems without falling, episodes of confusion and mood instability, although these latter difficulties were not as prominent as the executive dysfunction.

Brain MRI performed at her local institution 5 months prior to her referral at Mayo Clinic showed diffusion signal along the cortical ribbon, most marked posteriorly, and largely associated with increased FLAIR signal in a similar distribution. RT-QuIC testing was negative, but t-tau (2120 pg/ml) and 14-3-3 were abnormally elevated. Routine EEG at that time demonstrated intermittent vertex predominant (2–2.5Hz) spike-wave complexes, with symmetrically slowed (7–8Hz) posterior dominant rhythm and diffuse intermittent delta (0.5–4 Hz) slowing lasting up to 3 seconds. One electrographic seizure was captured with generalized fronto-centrally predominant 2Hz spike-and-slow-wave complexes associated clinically with a 10 seconds period of unresponsiveness; she was subsequently placed on levetiracetam.

She consulted in our behavioral neurology clinic one month later. She scored 14/38 on the STMS. Points were lost on the orientation (5/8) digit span (1/7), learning (2/4), calculation (0/4), abstraction (2/3), information (2/3), construction (1/4) and delayed recall (1/4) subscales. Her speech was halting and perseverative at times, with frequent paraphasic errors. She had some left-right confusion and clear praxis difficulties. There was no evidence of finger agnosia, extraocular movement abnormalities, visual agnosia, ataxia, or parkinsonism, nor adventitious movements.

MRI showed prominent diffusion restriction along the cortical ribbon and the basal ganglia which had progressed compared to the prior scan; all regions showed some T2/FLAIR hyperintensity. FDG-PET highlighted bilateral hypometabolism involving the left greater than right frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital lobes, and cingulate gyri with sparing of the primary sensorimotor cortices. A repeated routine EEG performed showed bitemporal, maximal left, sharply contoured transients superimposed on diffuse 4–7Hz slow wave abnormalities; there was no longer a well-defined posterior dominant rhythm. No definitive epileptiform discharges were noted. Repeated RT-QuIC testing returned positive, and CSF t-tau (724 pg/mL) and 14-3-3 were again abnormal. Biomarkers for AD pathophysiology were negative (Aβ42 >1700 pg/ml; P-Tau 27.1 pg/ml).

3.2. CJD case 2

The second case was a right-handed 68-year-old male. He reported a history of cognitive decline which apparently started 5 to 6 years prior to his consultation. This initially manifested with problems performing complex tasks under executive control. For instance, he experienced trouble with the temporal sequence of completing renovations at home, which was highly unusual for him as he was known to be particularly good with manual labor. He also mentioned problems with mental calculations and mathematics, which was also unusual for him as he used to work as a groundskeeper superintendent in a large institution. He also mentioned difficulties following instructions while driving under executive control, which caused him to stop this activity. Other symptoms were unspecified vision problems, high anxiety, jerky movements at night, difficulty sleeping and snoring, tremors, and strange positioning of the arms while walking, although these difficulties were not at the core of the clinical picture.

He scored 20/38 on the STMS. Points were lost on the orientation (5/8) digit span (4/7), calculation (2/4), abstraction (1/3), construction (0/4) and delayed recall (1/4) subscales, whereas all points were obtained for the learning (4/4) and information (4/4) subscales. He exhibited ideomotor and ideational apraxia, optic ataxia, oculomotor apraxia, simultagnosia and was unable to learn the Luria sequence. Repetition and naming were intact. He showed decreased arm swing and mild rigidity in the right arm and gegenhalten throughout right greater than left. He had impaired alternative motion rate and showed no response to plantar reflex. Gait was antalgic. The initial diagnostic impression based on clinical examination was dAD.

MRI revealed diffuse T2/FLAIR hyperintensity and diffusion restriction throughout the cortex, most notably within the temporoparietal regions, but also involving the frontal and occipital lobes. The FDG-PET examination confirmed hypometabolism in the frontal lobe bilaterally right greater than left, lateral parietal and inferior temporal lobes with involvement of the precuneus and posterior cingulate gyrus to a lesser degree and sparing of the sensorimotor cortices—a pattern consistent with dAD. 14-3-3, t-tau (3354 pg/mL) and neuron-specific enolase levels (71 pg/mL) were elevated, and RT-QuIC testing returned positive, establishing the diagnosis of CJD. Biomarkers were inconsistent with AD, where P-tau levels were abnormally elevated (100.5 pg/ml) but Aβ42 was in the normal range (1109.85 pg/ml).

This patient died 5 months following his visit. Brain autopsy demonstrated neuronal loss and gliosis with marked spongiosis in the medial temporal lobes, neocortex, and deep gray areas. Specific stain confirmed abnormal prion protein, with genotyping establishing the diagnosis of sporadic CJD (MM2 subtype) [1,6].

3.3. CJD case 3

The third case was a 58-year-old right-handed woman. She presented with a 10-month history of cognitive decline which initially manifested with problems with short-term memory, mental calculation, and following instructions while driving under executive control which caused her to get lost on one instance. Additional reported symptoms were mild depressive symptomatology and weight loss (33 pounds) over the past year.

She scored 18/38 on the STMS. Points were lost on the orientation (2/8) digit span (6/7), calculation (0/4), abstraction (2/3), construction (0/4) and delayed recall (0/4) subscales, whereas all points were obtained for the learning (4/4) and information (4/4) subscales. The remainder of the neurological examination was normal aside from mild and diffuse weakness in upper and lower extremities.

MRI examination revealed mild global cerebral and cerebellar volume loss without focal atrophy and minimal leukoaraiosis. There were signs of cortical ribboning in the posterior areas of the brain, including posterior, parietal and occipital regions. FDG-PET demonstrated right greater than left hemisphere cortical hypometabolism, involving the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes, with bilateral posterior cingulate and precuneus involvement and relative sparing of sensorimotor cortices, a pattern suggestive of dAD. Routine EEG demonstrated 0.5–8Hz slowing in the right temporal (F8/T8/P8) region with frequent focal sharp waves (T8/P8) in the setting of an asymmetric 8 Hz PDR, with reduced amplitude in the right posterior head region, and diffuse 4–8Hz slowing of the background rhythm maximal over the bitemporal regions. Biomarkers revealed abnormal T-tau (2201 pg/mL) and 14-3-3 protein levels; RT-QuIC was positive. Biomarkers were inconsistent with AD, where P-tau levels were abnormally elevated (82.95 pg/ml) but Aβ42 was in the normal range (1196.05 pg/ml).

4. Discussion

We report three cases of probable/definite CJD who presented with a predominant dysexecutive syndrome and a pattern of FDG-PET hypometabolism typically seen in dAD [3]. Interestingly, patterns of FDG-PET hypometabolism were bilateral but with a clear hemispheric predominance, which is also commonly observed in dAD [3,7]. Prior investigations have reported isolated neocortical syndromes at symptomatic onset of CJD [8–14], and FDG-PET studies have generally reported hypometabolism in the basal ganglia and focal cortical areas related to these isolated clinical symptoms [15–17]. Our findings are distinct from these in noting the predominant “high-level” cognitive symptomatology in association with neocortical hypometabolism in the parieto-frontal network which is subserving executive functions [3,18–21]. It is of note that parietal and frontal hypometabolism has been reported in CJD [17], but this pattern is generally unilateral and lack involvement of the posterior cingulate and precuneus, thus differing from the pattern typically observed in AD. On rare instances CJD cases mimicking neurodegenerative diseases targeting higher-order cognitive function like amnestic AD [22,23] have been described. However, cases reported in these studies were either late-onset [23] or lacked imaging findings [22].

Co-localization of EEG and MRI abnormalities in CJD have been previously reported [24], but the co-localization of hemispheric predominance in FDG-PET and EEG abnormalities as seen in cases 1 and 3 has only been previously reported in one case of the Heidenhain variant of CJD [25]. Lateralized abnormalities, electrographic seizures, and the absence of bisynchronous periodic slow wave complexes (PSWC) are atypical, but well-described electrographic findings in CJD [24,26]. Given the FDG-PET similarities between dAD and these atypical CJD cases, functional measures may increase our understanding of shared physiologic correlates underlying the dysexecutive syndrome in pathologically disparate brain diseases such as AD and CJD, which are not well demonstrated on MRI and cannot be determined by molecular testing. These findings suggest that abnormalities observed in these CJD cases, most notably those highlighted by FDG-PET which reflected predominant dysfunction of the parieto-frontal network, accurately reflect regional dysfunction of macro-scale anatomy supporting cognitive abilities degraded across diseases selectively targeting executive functions [3,27,28]. They also support the longstanding yet underappreciated fact that executive functions are subserved by distributed networks spanning heteromodal cortices including but not restricted to prefrontal areas [29–34].

One case was found to be a cortical MM2 subtype. Interestingly, a study in twelve patients with the cortical MM2 cortical subtype showed that all patients had neuropsychological deficits at symptom onset, which emerged on average 6 to 8 months prior to typical signs of CJD[35]. Additionally, four of these cases were initially diagnosed with AD. It is thus possible that patients with the cortical MM2 subtype are predisposed to CJD, although pending post-mortem confirmation in the other two cases.

The symptomatology of unusual presentations of CJD manifesting with a predominant cognitive phenotype has traditionally been described as early “cognitive impairment” or “dementia”, most often without specifying the cognitive domain central to the clinical picture [2,36]. Here we highlight a clinical phenotype of CJD initially presenting with a predominant dysexecutive syndrome. This is far from trivial in the context of the recent characterization of dAD [3], which presents with highly similar clinical features and FDG-PET hypometabolism pattern as the CJD patients presented here. Increased awareness about the range of neurodegenerative diseases causing a progressive dysexecutive syndrome is critical for differential diagnosis and disease monitoring, given that nearly indistinguishable FDG-PET hypometabolism patterns can be observed despite distinct underlying etiologies [27]. This is particularly important considering that patients might initially consult in local, non-specialized settings with limited resources to evaluate the full spectrum of possible etiologies underlying cognitive symptomatology in the setting of an atypical presentation of a rare disease such as CJD. Optimally, neuropsychological assessment data would have also been included to better document the nature and extent of cognitive dysfunction observed in these patients. Such information may potentially help in identifying clinical features distinguishing this atypical and dysexecutive presentation CJD from other dementia syndromes targeting executive functions. Unfortunately, this was not done in these patients as clinical diagnoses relied on neurological examination, and further inquiry into this question is needed.

Despite the presence of a dysexecutive syndrome and a dAD-like pattern of FDG-PET hypometabolism, all three patients showed restricted diffusion on MRI, abnormal levels of 14-3-3 and total-tau, and RT-QuIC testing. Although FDG-PET shows respectable sensitivity to differentiate AD from other common neurodegenerative diseases [37,38], in isolation it may not be sufficient for etiologic diagnosis when an unusual presentation of CJD is reasonably within the differential. Signal hyperintensity on FLAIR or DWI in at least two cortical regions or both caudate nucleus and the putamen remains to date the most sensitive imaging biomarker of CJD [39]. Thus, the systematic inclusion of the FLAIR and DWI acquisitions could represent an ecumenical avenue when fluid biomarkers and RT-QuIC testing are not readily available. It is also noteworthy that one patient had a negative RT-QuiC followed by a positive one. Although RT-QuiC is usually considered a gold standard measure to detect CJD, its sensitivity oscillates around 90% [40]. CJD cases with a negative RT-QuiC but otherwise compelling picture for CJD are thus rare but not undocumented. Moreover, two patients had elevated levels of P-Tau, which is a biomarker feature characteristic of AD. Although P-tau levels are usually lower in CJD than in AD, they are higher than in control individuals and other types of dementia (e.g., FTD) at the group-level and can often exceed thresholds of positivity [41–44]. Given the remarkably high levels of T-Tau usually seen in CJD, a T-Tau/P-Tau ratio has been suggested to offer high specificity and sensitivity compared to other neurodegenerative diseases, including AD [44]. Overall, this prompts for the need to integrate information on clinical course with multimodal imaging and fluid biomarkers to provide a precise etiology for dementia syndromes.

5. Conclusions

This clinical case series highlights that CJD can present with an atypical and predominant dysexecutive syndrome, masquerading common neurodegenerative diseases such as dAD. The use of multimodal imaging, especially FLAIR and DWI sequences, and assessment of CSF biomarkers/RT-QuIC testing can help disentangling CJD from other neurodegenerative diseases known to primarily target executive functions. This has implications for early diagnosis, prognosis, and symptom monitoring of patients with CJD. This is especially true in the era of expanding disease-modifying therapies targeting AD pathology, where patients receiving a misdiagnosis of AD could inadvertently be treated with inappropriate drugs.

Highlights.

CJD can present with a predominant dysexecutive syndrome

Clinical features and imaging findings can mimic newly defined dysexecutive AD

MRI and RT-QuIC can disambiguate this syndrome from AD

This has implications for early diagnosis and prognosis of CJD and AD

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our gratitude to our patients and their caregivers for their continuous dedication to our research program. We would also like to thank all healthcare providers and research professionals who were involved in this study but are not listed as coauthors.

Funding

There was no funding specifically dedicated to this research.

Conflicts of interests

GS Day is supported by a career development grant from the NIH (K23AG064029). He owns stock (>$10,000) in ANI Pharmaceuticals (a generic pharmaceutical company). He serves as a topic editor for DynaMed (EBSCO), overseeing development of evidence-based educational content, and as the Clinical Director of the Anti-NMDA Receptor Encephalitis Foundation (Inc, Canada; uncompensated).

Footnotes

Ethics approval

This retrospective study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Consent to participate

All patients or their informant provided written consent for their clinical data to be used for research purposes.

References

- 1.Zerr I, Parchi P. Sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 2018; 155–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baiardi S, Capellari S, Stella AB, Parchi P. Unusual clinical presentations challenging the early clinical diagnosis of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018;64(4):1051–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Townley RA, Graff-Radford J, Mantyh WG, Botha H, Polsinelli AJ, Przybelski SA, et al. Progressive dysexecutive syndrome due to Alzheimer’s disease: a description of 55 cases and comparison to other phenotypes. Brain Commun. 2020;2(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kokmen E, Smith GE, Petersen RC, Tangalos E, Ivnik RC. The Short Test of Mental Status: Correlations With Standardized Psychometric Testing. Arch Neurol. 1991;48(7):725–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Townley RA, Syrjanen JA, Botha H, Kremers WK, Aakre JA, Fields JA, et al. Comparison of the Short Test of Mental Status and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Across the Cognitive Spectrum. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(8):1516–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parchi P, Giese A, Capellari S, Brown P, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Windl O, et al. Classification of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease based on molecular and phenotypic analysis of 300 subjects. Ann Neurol. 1999;46(2):224–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corriveau-Lecavalier N, Machulda MM, Botha H, Graff-Radford J, Knopman DS, Lower VJ, et al. Phenotypic subtypes of progressive dysexecutive syndrome due to Alzheimer’s disease: a series of clinical cases. J Neurol. (accepted). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baiardi S, Capellari S, Ladogana A, Strumia S, Santangelo M, Pocchiari M, et al. Revisiting the Heidenhain variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: evidence for prion type variability influencing clinical course and laboratory findings. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2016;50(2):465–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krasnianski A, Kaune J, Jung K, Kretzschmar HA, Zerr I. First symptom and initial diagnosis in sporadic CJD patients in Germany. J Neurol. 2014;261(9):1811–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Townley RA, Dawson ET, Drubach DA. Heterozygous genotype at codon 129 correlates with prolonged disease course in Heidenhain variant sporadic CJD: case report. Neurocase. 2018;24(1):54–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caine D, Nihat A, Crabb P, Rudge P, Cipolotti L, Collinge J, et al. The language disorder of prion disease is characteristic of a dynamic aphasia and is rarely an isolated clinical feature. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0190818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El Tawil S, Chohan G, Mackenzie J, Rowe A, Weller B, Will RG, et al. Isolated language impairment as the primary presentation of sporadic Creutzfeldt Jakob Disease. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;135(3):316–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tobias E, Mann C, Bone I, De Silva R, Ironside J. A case of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease presenting with cortical deafness. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57(7):872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orimo S, Ozawa E, Uematsu M, Yoshida E. A case of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease presenting with auditory agnosia as an initial manifestation. Eur Neurol. 2000;44(4):256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henkel K, Zerr I, Hertel A, Gratz K-F, Schröter A, Tschampa HJ, et al. Positron emission tomography with [18 F] FDG in the diagnosis of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD). J Neurol. 2002;249(6):699–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim E, Cho S, Jeong B, Kim Y, Seo SW, Na DL, et al. Glucose metabolism in sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease: a statistical parametric mapping analysis of 18F-FDG PET. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19(3):488–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Renard D, Castelnovo G, Collombier L, Thouvenot E, Boudousq V. FDG-PET in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: analysis of clinical-PET correlation. Prion. 2017;11(6):440–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones DT, Vemuri P, Murphy MC, Gunter JL, Senjem ML, Machulda MM, et al. Non-stationarity in the “resting brain’s” modular architecture. PLoS One. 2012;7(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones AD, Lowe V, Botha H, Wiepert D, Murphy MC. Patterns of neurodegeneration in dementia reflect a global functional state space. 2020.

- 20.Binkofski F, Buccino G, Posse S, Seitz RJ, Rizzolatti G, Freund HJ. A fronto-parietal circuit for object manipulation in man: Evidence from an fMRI-study. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11(9):3276–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Selemon LD, Goldman-Rakic PS. Common cortical and subcortical targets of the dorsolateral prefrontal and posterior parietal cortices in the rhesus monkey: evidence for a distributed neural network subserving spatially guided behavior. J Neurosci. 1988;8(11):4049–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kapur N, Abbott P, Lowman A, Will RG. The neuropsychological profile associated with variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Brain. 2003;126(12):2693–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyazawa N. Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Mimicking Alzheimer Disease and Dementia With Lewy Bodies-Findings of FDG PET With 3-Dimensional Stereotactic Surface Projection. Clin Nucl Med. 2017;42(5):e247–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cambier DM, Kantarci K, Worrell GA, Westmoreland BF, Aksamit AJ. Lateralized and focal clinical, EEG, and FLAIR MRI abnormalities in Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;114(9):1724–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feyissa AM, Wirrell EC, Jones DT, Young NP, Britton JW. Focal photoparoxysmal response in the Heidenhain variant of CJD: Hidden from view! Neurology. 2016;86(17):1647–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wieser HG, Schindler K, Zumsteg D. EEG in Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117(5):935–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones DT. Multiple aetiologies of the progressive dysexecutive syndrome and the importance of biomarkers. Brain Commun. 2020;2(2):fcaa127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tábuas-Pereira M, Almeida MR, Duro D, Lima M, Durães J, Guerreiro R, et al. Patients with progranulin mutations overlap with the progressive dysexecutive syndrome: towards the definition of a frontoparietal dementia phenotype. Brain Comms. 2020; 2(2), fcaa126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Friedman HR, Goldman-Rakic PS. Coactivation of prefrontal cortex and inferior parietal cortex in working memory tasks revealed by 2DG functional mapping in the rhesus monkey. J Neurosci. 1994. May 1;14(5):2775–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldman-Rakic PS. Topography of cognition: parallel distributed networks in primate association cortex. Ann Rev Neurosci. 1998; 11(1), 137–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graff-Radford J, Yong KX, Apostolova LG, Bouwman FH, Carrillo M, Dickerson BC, et al. New insights into atypical Alzheimer’s disease in the era of biomarkers. The Lancet Neurol. 2020; 20(3), 222–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones DT, & Graff-Radford J. Executive Dysfunction and the Prefrontal Cortex. CONTINUUM: Lifelong Learning in Neurology. 2021; 27(6), 1586–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mesulam MM. Large-scale neurocognitive networks and distributed processing for attention, language, and memory. Ann Neurol. 1990: 28(5), 597–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uddin LQ. Cognitive and behavioural flexibility: neural mechanisms and clinical considerations. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2021; 22(3), 167–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krasnianski A, Meissner B, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Kallenberg K, Bartl M, Heinemann U, et al. Clinical features and diagnosis of the MM2 cortical subtype of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(6):876–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mead S, Rudge P. CJD mimics and chameleons. Pract Neurol. 2017;17(2):113–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herholz K. FDG PET and differential diagnosis of dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nadebaum DP, Krishnadas N, Poon AMT, Kalff V, Lichtenstein M, Villemagne VL, et al. A head-to-head comparison of cerebral blood flow SPECT and 18F-FDG PET in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Intern Med J. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zerr I, Kallenberg K, Summers DM, Romero C, Taratuto A, Heinemann U, et al. Updated clinical diagnostic criteria for sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Brain. 2009;132(10):2659–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rhoads DD, Wrona A, Foutz A, Blevins J, Glisic K, Person M, et al. Diagnosis of prion diseases by RT-QuIC results in improved surveillance. Neurology. 2020; 95(8):e1017–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schonberger LB, Tatsuoka C, Cohen ML. Diagnosis of prion diseases by RT-QuIC results in improved surveillance. Neurology. 2020; 95(8):e1017–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lattanzio F, Abu-Rumeileh S, Franceschini A, Kai H, Amore G, Poggiolini I, … & Parchi P (2017). Prion-specific and surrogate CSF biomarkers in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: diagnostic accuracy in relation to molecular subtypes and analysis of neuropathological correlates of p-tau and Aβ42 levels. Acta neuropathologica, 133(4), 559–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Riemenschneider M, Wagenpfeil S, Vanderstichele H, Otto M, Wiltfang J, Kretzschmar H, et al. Phospho-tau/total tau ratio in cerebrospinal fluid discriminates Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease from other dementias. Molecular psychiatry. 2003; 8(3), 343–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Skillbäck T, Rosén C, Asztely F, Mattsson N, Blennow K, Zetterberg H. Diagnostic performance of cerebrospinal fluid total tau and phosphorylated tau in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: results from the Swedish Mortality Registry. JAMA Neurol. 2014; 1;71(4):476–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]