Key Points

Question

Does the programmed cell death 1 inhibitor serplulimab, when added to chemotherapy during the first line of treatment, improve outcomes in patients with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial that included 585 patients with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer who had not previously received systemic therapy, serplulimab plus chemotherapy, compared with placebo plus chemotherapy, significantly improved overall survival (15.4 months vs 10.9 months, respectively; hazard ratio for death, 0.63).

Meaning

In patients with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer, serplulimab plus chemotherapy as the first-line treatment resulted in improved overall survival compared with chemotherapy alone.

Abstract

Importance

Programmed cell death ligand 1 inhibitors combined with chemotherapy has changed the approach to first-line treatment in patients with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (SCLC). It remained unknown whether adding a programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) inhibitor to chemotherapy provided similar or better benefits in patients with extensive-stage SCLC, which would add evidence on the efficacy of checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of extensive-stage SCLC.

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy and adverse event profile of the PD-1 inhibitor serplulimab plus chemotherapy compared with placebo plus chemotherapy as first-line treatment in patients with extensive-stage SCLC.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This international, double-blind, phase 3 randomized clinical trial (ASTRUM-005) enrolled patients at 114 hospital sites in 6 countries between September 12, 2019, and April 27, 2021. Of 894 patients who were screened, 585 with extensive-stage SCLC who had not previously received systemic therapy were randomized. Patients were followed up through October 22, 2021.

Interventions

Patients were randomized 2:1 to receive either 4.5 mg/kg of serplulimab (n = 389) or placebo (n = 196) intravenously every 3 weeks. All patients received intravenous carboplatin and etoposide every 3 weeks for up to 12 weeks.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was overall survival (prespecified significance threshold at the interim analysis, 2-sided P < .012). There were 13 secondary outcomes, including progression-free survival and adverse events.

Results

Among the 585 patients who were randomized (mean age, 61.1 [SD, 8.67] years; 104 [17.8%] women), 246 (42.1%) completed the trial and 465 (79.5%) discontinued study treatment. All patients received study treatment and were included in the primary analyses. As of the data cutoff (October 22, 2021) for this interim analysis, the median duration of follow-up was 12.3 months (range, 0.2-24.8 months). The median overall survival was significantly longer in the serplulimab group (15.4 months [95% CI, 13.3 months-not evaluable]) than in the placebo group (10.9 months [95% CI, 10.0-14.3 months]) (hazard ratio, 0.63 [95% CI, 0.49-0.82]; P < .001). The median progression-free survival (assessed by an independent radiology review committee) also was longer in the serplulimab group (5.7 months [95% CI, 5.5-6.9 months]) than in the placebo group (4.3 months [95% CI, 4.2-4.5 months]) (hazard ratio, 0.48 [95% CI, 0.38-0.59]). Treatment-related adverse events that were grade 3 or higher occurred in 129 patients (33.2%) in the serplulimab group and in 54 patients (27.6%) in the placebo group.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among patients with previously untreated extensive-stage SCLC, serplulimab plus chemotherapy significantly improved overall survival compared with chemotherapy alone, supporting the use of serplulimab plus chemotherapy as the first-line treatment for this patient population.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04063163

This randomized clinical trial evaluates the efficacy and adverse event profile of serplulimab plus chemotherapy compared with placebo plus chemotherapy as first-line treatment in patients with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer.

Introduction

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is the most aggressive subtype of lung cancer, accounting for around 15% of all lung cancer cases and characterized by rapid proliferation and metastasis.1,2 Patients with SCLC usually present with extensive-stage disease at the time of diagnosis; the 5-year survival rate is only 7%.2 Since the 1990s, the standard first-line treatment for extensive-stage SCLC remained chemotherapy with a platinum-based agent plus etoposide, providing a median overall survival of approximately 10 months.3,4

Recent phase 3 trials of the programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitor atezolizumab or durvalumab combined with chemotherapy found significantly prolonged overall survival compared with the control group in patients with extensive-stage SCLC who had not previously received systemic therapy.5,6 Based on these trial results, the 2 combination therapies have been approved worldwide for first-line treatment of patients with extensive-stage SCLC.7,8,9,10 However, improvements in overall survival with the approved PD-L1 inhibitors were modest (12.9 months for durvalumab plus chemotherapy vs 10.5 months for chemotherapy,11 hazard ratio [HR], 0.71 and 12.3 months for atezolizumab plus chemotherapy vs 10.3 months for placebo plus chemotherapy,6 HR, 0.76), suggesting an unmet clinical need for more effective treatments in patients with extensive-stage SCLC.5,6 In comparison, the programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) inhibitor pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy prolonged progression-free survival, but did not significantly improve overall survival compared with placebo plus chemotherapy in a phase 3 trial.12

Serplulimab (formerly HLX10) is a fully humanized IgG4 monoclonal antibody against the PD-1 receptor. In a phase 1 trial, up to 10 mg/kg of serplulimab was well tolerated and demonstrated similar pharmacokinetic characteristics to pembrolizumab and nivolumab.13 Serplulimab showed antitumor activity and a manageable adverse event profile for a variety of cancers in phase 2 clinical trials.14,15 The ASTRUM-005 trial aimed to evaluate the efficacy and adverse event profile of PD-1 inhibitor serplulimab plus chemotherapy vs placebo plus chemotherapy in patients with extensive-stage SCLC who had not previously received systemic therapy.

Methods

Trial Oversight

This trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and local applicable regulatory requirements. The trial protocol, any amendments, the statistical analysis plan, and informed consent were approved by the central or independent institutional review board or ethics committee at the participating hospital sites. All participants provided written informed consent. The trial protocol, any amendments, and the statistical analysis plan appear in Supplement 1.

Patients

Eligible patients were aged 18 years or older, had histologically or cytologically confirmed extensive-stage SCLC according to the Veterans Administration Lung Study Group staging system, and had not previously received systemic therapy for extensive-stage SCLC. Patients must have had 1 or more measurable lesions assessed using version 1.1 of the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status Scale score of 0 or 1, adequate organ function, and a life expectancy of 12 weeks or longer. Key exclusion criteria included mixed-stage SCLC, active central nervous system metastases or carcinomatous meningitis, and autoimmune diseases. Patients with asymptomatic and stable brain metastases were included (patients were considered to have stable brain metastases if there was no evidence of new or enlarging brain metastases for ≥2 months as confirmed by 2 radiological examinations at least 4 weeks apart after treatment and if patients had discontinued steroid use 3 days prior to study drug administration). The full eligibility criteria appear in the eMethods in Supplement 2.

Race and ethnicity were self-reported by the patients using fixed categories or were based on identity information provided by the patients. Both race and ethnicity were included after consultation with the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency.

Randomization

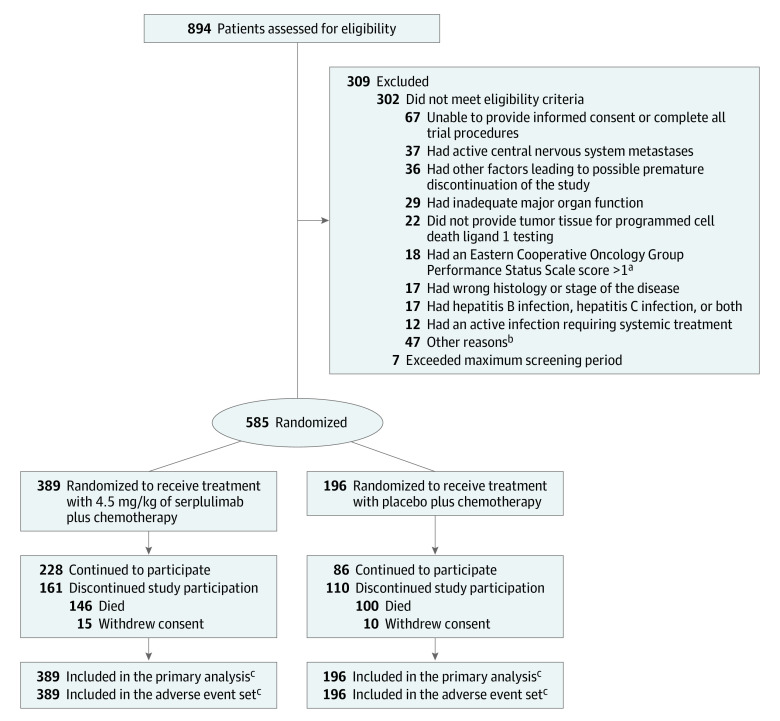

This double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 randomized clinical trial was conducted in China, Georgia, Poland, Russia, Turkey, and Ukraine. Patients were randomized 2:1 to the serplulimab group or the placebo group (Figure 1). Randomization was performed centrally using an interactive web and voice-response system with randomly selected block sizes of 3, 6, or 9, stratified by PD-L1 expression level (tumor proportion score <1%, ≥1%, or not evaluable or available), brain metastases (yes or no), and age (≥65 years or <65 years).

Figure 1. Recruitment, Randomization, and Flow of Patients With Extensive-Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer in the ASTRUM-005 Trial.

The date of data cutoff was October 22, 2021.

aScores range from 0 to 5 (higher scores indicate greater disability).

bDetailed reasons appear in eTable 1 in Supplement 2.

cPatients received at least 1 dose of study treatment.

Interventions

Patients received either 4.5 mg/kg of serplulimab or placebo via intravenous infusions every 3 weeks until disease progression, death, unacceptable toxicity, withdrawal of consent, or other reasons specified in the trial protocol (Supplement 1). All patients received 100 mg/m2 of etoposide on days 1, 2, and 3 and carboplatin within the area under the serum drug concentration time curve of 5 mg/mL/min (up to 750 mg) on day 1 of each cycle for up to 4 cycles via intravenous infusions. Patients were eligible to continue receiving the assigned treatment after disease progression at the discretion of the investigators if prespecified criteria were met (eMethods in Supplement 2).

Outcomes and Assessments

The primary outcome was overall survival. There were 13 secondary outcomes, including progression-free survival, objective response rate, and duration of response (all 3 were assessed both by an independent radiology review committee and by the investigators using version 1.1 of RECIST), adverse events, and the relationship between PD-L1 expression and efficacy. The definitions for the efficacy outcomes appear in the eMethods in Supplement 2.

The secondary outcome of progression-free survival that was assessed by the investigators using version 1.1 of the modified RECIST for immune-based therapeutics is not reported in this article as well as additional unreported secondary outcomes (pharmacokinetics, immunogenicity of serplulimab, other biomarkers including microsatellite instability and tumor mutational burden, and quality of life).

Expression of PD-L1 was assessed centrally by Labcorp Drug Development using PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx assay kit on the Dako Autostainer link 48 platform (Agilent Technologies). A positive PD-L1 expression level was defined as a tumor proportion score of 1% or greater. Details of the PD-L1 assessment method appear in the eMethods in Supplement 2. Tumor responses were assessed at screening, every 6 weeks for the first 48 weeks, and every 9 weeks thereafter.

Treatment-emergent adverse events were recorded throughout the trial and for 90 days after the last dose was received, and were graded according to version 5.0 of the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events. The investigators evaluated the causality between serplulimab or placebo and the treatment-emergent adverse events and classified the events as “related,” “possibly related,” “unlikely related,” “unrelated,” or “unknown”; the investigators were blinded to treatment allocation when they made the assessments. The treatment-emergent adverse events were recorded as “serplulimab-related” or “placebo-related” unless they had a classification of “unlikely related” and “unrelated” to serplulimab or placebo.

Sample Size Calculation

The sample size calculation was based on overall survival. The initial sample size calculation was based on progression-free survival. A protocol amendment (protocol version 3.0 dated April 8, 2020) was made at the request of the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency that changed the primary outcome from progression-free survival to overall survival and the sample size was recalculated. Enrollment of 567 patients (378 in the serplulimab group and 189 in the placebo group) was planned based on a dropout rate of 20%. It was estimated that 342 deaths would be needed to provide 85% power at a 2-sided α level of .05 to detect an HR of 0.7 for death in the serplulimab group vs the placebo group, assuming a median overall survival of 10 months in the placebo group. The assumption of an HR of 0.7 for death was made on the basis of results from the IMpower133 trial.16

Statistical Analysis

Efficacy was assessed in patients who underwent randomization according to their randomized group. Adverse events were assessed in the adverse event set, which comprised randomized patients who received at least 1 dose of study treatment.

Overall survival, progression-free survival, and duration of response were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. For the analysis of overall survival, data for patients who were alive were censored on the last known survival date. The Brookmeyer-Crowley method was used to calculate the 95% CIs for median overall survival, progression-free survival, and duration of response.

The between-group comparisons of overall survival and progression-free survival were calculated using a stratified log-rank test. A stratified Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate the HRs and 95% CIs. The proportionality assumption was tested using the Grambsch-Therneau test (2-sided P = .67) and visually checked on a Schoenfeld residual plot. The results indicated that the proportionality assumption was not violated.

The objective response rate was analyzed using the stratified Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel method. Preplanned subgroup analyses of overall survival were conducted according to demographics, prognostic factors, and PD-L1 expression level using descriptive statistics and HRs and 95% CIs. Post hoc tests for interaction were conducted by adding treatment, subgroup factor, and a subgroup factor × treatment interaction term into a Cox proportional hazards model.

Missing data for overall survival and progression-free survival were imputed only under the following circumstances: (1) if the day of death was missing but the year and month were available, the date of death was imputed by the first day of the month or the latest known alive date, whichever was later or (2) if the day of tumor assessment was missing but the year and month were available and were earlier than the date when the patient was known to be alive, the date of tumor assessment was imputed by the day after the last date of tumor assessment or the first day in the month of disease progression or death, whichever was later. The full methods for handling missing data appear in the statistical analysis plan in Supplement 1.

The interim analyses were planned after 226 patients died and the final analyses were planned after 342 patients died. The O’Brien-Fleming method for the α spending function was used to control the study-wise type I error rate at a 2-sided α level of .05. The P-value boundary for superiority of overall survival was .012 during the interim analysis and .046 during the final analysis. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, the findings for the analyses of the secondary outcomes should be interpreted as exploratory. All statistical analyses were calculated using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Patients and Treatment

Between September 12, 2019, and April 27, 2021, 894 patients were screened at 114 hospital sites in 6 countries. Among the 585 patients who were randomized (mean age, 61.1 years [SD, 8.67 years]; 104 [17.8%] women), 246 (42.1%) completed the trial and 465 (79.5%) discontinued study treatment (292 patients [75.1%] in the serplulimab group and 173 patients [88.3%] in the placebo group). The most common reason for discontinuing study treatment was disease progression. The included patients (389 in the serplulimab group and 196 in the placebo group) received 1 dose or more of the study treatment and their data were included in the primary analysis and adverse event set. A total of 309 patients were excluded prior to randomization (Figure 1 and eTable 1 in Supplement 2). The baseline characteristics were balanced between the 2 groups (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients With Extensive-Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer in the ASTRUM-005 Trial.

| Patients with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer, No. (%)a | ||

|---|---|---|

| Serplulimab (n = 389) | Placebo (n = 196) | |

| Age, median (range), y | 63 (28-76) | 62 (31-83) |

| Aged <65 y | 235 (60.4) | 119 (60.7) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 317 (81.5) | 164 (83.7) |

| Female | 72 (18.5) | 32 (16.3) |

| Raceb | ||

| Asian | 262 (67.4) | 139 (70.9) |

| Non-Asianc | 127 (32.6) | 57 (29.1) |

| Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status Scale scored | ||

| 0 (fully active) | 71 (18.3) | 32 (16.3) |

| 1 (restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory) | 318 (81.7) | 164 (83.7) |

| Smoking history | ||

| Never | 81 (20.8) | 35 (17.9) |

| Current | 102 (26.2) | 48 (24.5) |

| Former | 206 (53.0) | 113 (57.7) |

| Size of target lesions, median (range), mm in diametere | 117.7 (13.8-323.7) | 120.5 (14.5-269.6) |

| Type of metastases | ||

| Brain | 50 (12.9) | 28 (14.3) |

| Liver | 99 (25.4) | 51 (26.0) |

| Programmed cell death ligand 1 expression level, No./total (%) | ||

| Tumor proportion score <1%f | 317/379 (83.6) | 152/186 (81.7) |

| Tumor proportion score ≥1%f | 62/379 (16.4) | 34/186 (18.3) |

| Previous cancer treatment | ||

| Chemotherapyg | 9 (2.3) | 3 (1.5) |

| Otherh | 1 (0.3) | 2 (1.0) |

Some of the data are expressed as median (range) as indicated in the rows.

Self-reported by the patients by selecting 1 or more racial designations (American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, White, or Other) or based on identity information provided by the patients.

All patients were White.

Scores range from 0 to 5 (higher scores indicate greater disability).

Measured using computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging.

Not evaluable or no data for 20 patients (3.4%). This was mostly due to inappropriate sectioning or poor sample quality (insufficient evaluable cells).

There were 11 patients who had received treatment for limited-stage small cell lung cancer (treatment-free interval ≥6 months). One patient in the placebo group had received treatment for gastric cancer (>5 years ago).

Herbal or traditional Chinese medicine (2 in the placebo group) and the immunostimulant lentinan (1 in the serplulimab group).

At the data cutoff for the interim analysis (October 22, 2021), 97 patients (24.9%) in the serplulimab group and 23 patients (11.7%) in the placebo group were still receiving study treatment. All patients were followed up for a median of 12.3 months (range, 0.2-24.8 months). After the first incidence of disease progression, subsequent treatment was received by 172 patients (44.2%) in the serplulimab group and 85 patients (43.4%) in the placebo group (eTable 2 in Supplement 2).

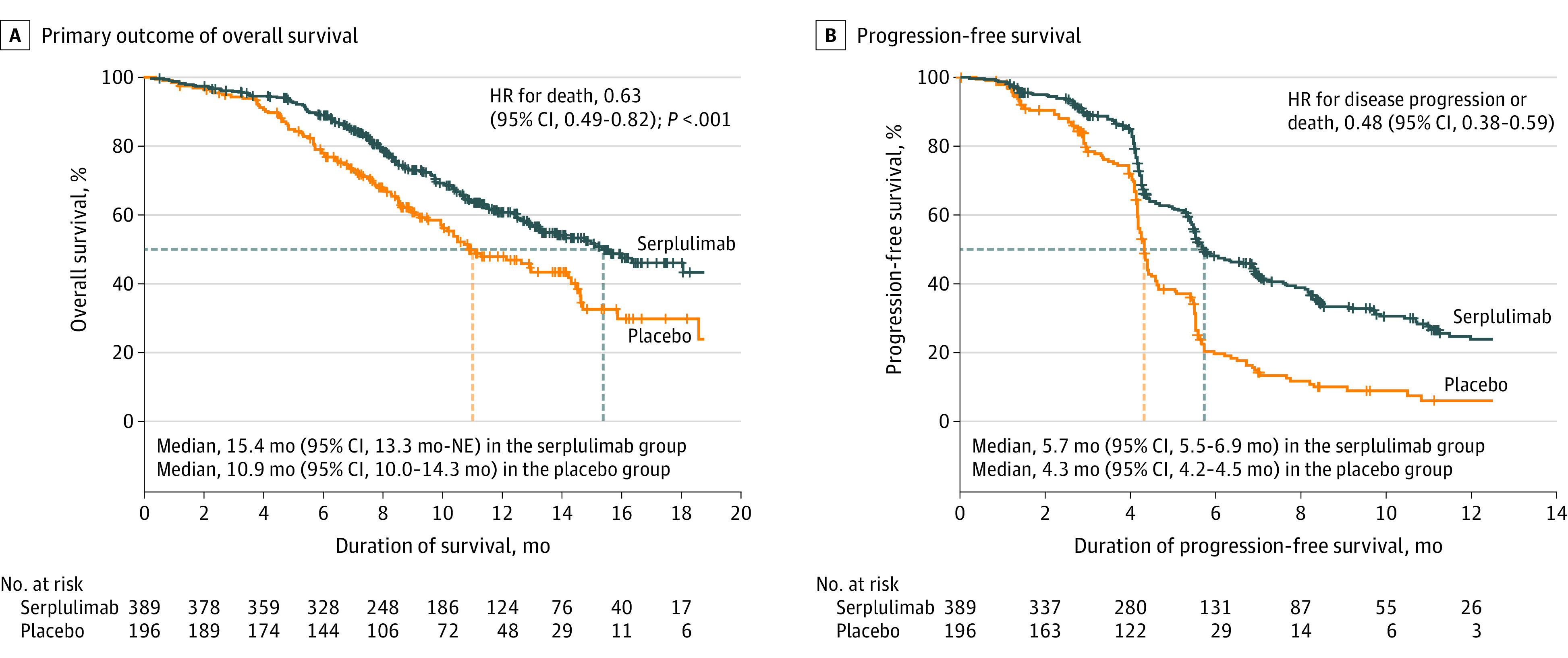

Primary Outcome

By the time of the interim analysis, 146 patients (37.5%) had died in the serplulimab group compared with 100 patients (51.0%) in the placebo group. There were 243 patients in the serplulimab group who were censored without evidence of death (62.5%; 228 [58.6%] alive and 15 [3.9%] lost to follow-up) compared with 96 patients in the placebo group (49.0%; 86 [43.9%] alive and 10 [5.1%] lost to follow-up). The median overall survival was 15.4 months (95% CI, 13.3 months-not evaluable) in the serplulimab group compared with 10.9 months (95% CI, 10.0-14.3 months) in the placebo group (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Estimates of Overall and Progression-Free Survival.

Data are from assessments by the independent radiology review committee using version 1.1 of the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors. The tick marks indicate censored data. The median duration of follow-up for overall survival at the interim analysis was 12.5 months (IQR, 8.9-15.5 months) for the serplulimab group and 12.3 months (IQR, 8.6-14.9 months) for the placebo group. The median duration of follow-up for progression-free survival was 9.5 months (IQR, 5.6-13.2 months) for the serplulimab group and 8.4 months (IQR, 7.0-13.0 months) for the placebo group. HR indicates hazard ratio; NE, not evaluable.

The primary outcome reached prespecified statistical significance (HR, 0.63 [95% CI, 0.49-0.82]; P < .001). The estimated overall survival rate at 1 year was 60.7% (95% CI, 54.9%-66.0%) in the serplulimab group compared with 47.8% (95% CI, 39.6%-55.6%) in the placebo group. The estimated overall survival rate at 2 years was 43.1% (95% CI, 34.1%-51.7%) in the serplulimab group compared with 7.9% (95% CI, 0.7%-27.2%) in the placebo group.

Secondary Outcomes

Assessments by the Independent Radiology Review Committee

The independent radiology review committee assessed progression-free survival, objective response rate, and duration of response using version 1.1 of RECIST. The committee found that 223 patients (57.3%) in the serplulimab group had disease progression or died compared with 151 patients (77.0%) in the placebo group and the median progression-free survival was 5.7 months (95% CI, 5.5-6.9 months) compared with 4.3 months (95% CI, 4.2-4.5 months), respectively (HR, 0.48 [95% CI, 0.38-0.59]; Figure 2B). The objective response rate was 80.2% (95% CI, 75.9%-84.1%) in the serplulimab group compared with 70.4% (95% CI, 63.5%-76.7%) in the placebo group (Table 2). Among patients with complete or partial tumor response, the median duration of response was 5.6 months (95% CI, 4.2-6.8 months) in the serplulimab group compared with 3.2 months (95% CI, 2.9-4.2 months) in the placebo group.

Table 2. Secondary Outcomes of Tumor Response Assessed by the Independent Radiology Review Committee.

| Serplulimab (n = 389) | Placebo (n = 196) | |

|---|---|---|

| Complete or partial tumor response, No. (%) [95% CI]a | 312 (80.2) [75.9-84.1] | 138 (70.4) [63.5-76.7] |

| Best response, No./total (%)a | ||

| Complete response | 3/370 (0.8) | 0/186 |

| Partial response | 309/370 (83.5) | 138/186 (74.2) |

| Stable disease | 49/370 (13.2) | 37/186 (19.9) |

| Progressive disease | 9/370 (2.4) | 11/186 (5.9) |

| Duration of responsea | ||

| Median (95% CI), mob | 5.6 (4.2-6.8) | 3.2 (2.9-4.2) |

| Lasted ≥12 mo, % (95% CI)c | 24.0 (17.3-31.4) | 8.9 (3.6-17.0) |

Assessed using version 1.1 of the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors at screening, every 6 weeks for the first 48 weeks, and every 9 weeks thereafter.

Among patients with a complete or partial tumor response, which was defined as the time from first objective response to disease progression or death from any cause.

Calculated based on the Kaplan-Meier product limit estimate, which was a cumulative probability.

Assessments by the Investigators

The investigators assessed progression-free survival, objective response rate, and duration of response using version 1.1 of RECIST. The median progression-free survival assessed by the investigators was 5.5 months in the serplulimab group compared with 4.3 months in the placebo group (HR, 0.58 [95% CI, 0.48-0.71]; eFigure in Supplement 2), which was consistent with that assessed by the committee. The assessments of tumor response and duration of response by the investigators were consistent with the committee’s assessments (eTable 3 in Supplement 2).

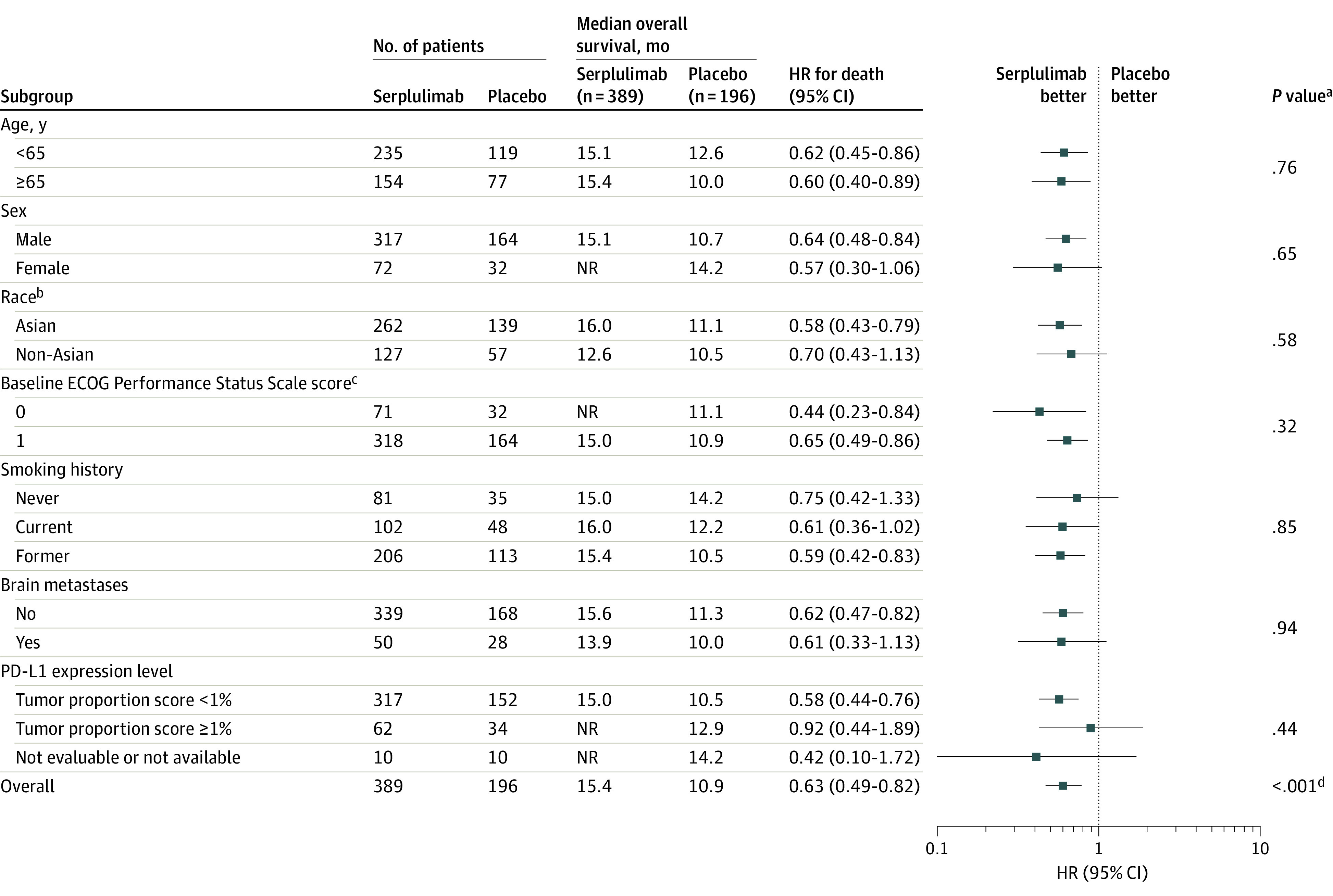

Prespecified Subgroup Analyses and Post Hoc Analyses

The HR for overall survival consistently favored the serplulimab group across the prespecified subgroups (Figure 3). In patients with brain metastases, the median overall survival was 13.9 months (95% CI, 9.0 months-not evaluable) in the serplulimab group compared with 10.0 months (95% CI, 7.2-12.7 months) in the placebo group (HR, 0.61 [95% CI, 0.33-1.13]). In patients without brain metastases, the median overall survival was 15.6 months (95% CI, 13.3 months-not evaluable) in the serplulimab group compared with 11.3 months (95% CI, 10.0-14.6 months) in the placebo group (HR, 0.62 [95% CI, 0.47-0.82]). There seemed to be an imbalance in median overall survival for patients with a tumor proportion score of less than 1% for PD-L1 expression level (15.0 months in the serplulimab group compared with 10.5 months in the placebo group; HR, 0.58 [95% CI, 0.44-0.76]) and for patients with a tumor proportion score of 1% or greater (not reached vs 12.9 months, respectively; HR, 0.92 [95% CI, 0.44-1.89]). However, the post hoc test for interaction did not show significant interactions between the subgroup factors and treatment group.

Figure 3. Subgroup Analysis for the Primary Outcome of Overall Survival.

The date of data cutoff was October 22, 2021. The hazard ratios (HRs) and P values were not stratified for the patient subgroups and were stratified for the overall population. The median duration of follow-up for overall survival at the interim analysis was 12.5 months (IQR, 8.9-15.5 months) for the serplulimab group and 12.3 months (IQR, 8.6-14.9 months) for the placebo group in the overall population. NR indicates not reached; PD-L1, programmed cell death ligand 1.

aFor the patient subgroups, the P values for interaction were calculated by adding treatment, subgroup factor, and a subgroup factor × treatment interaction term into a Cox proportional hazards model.

bSelf-reported by the patients by selecting 1 or more racial designations (American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, White, or Other) or based on identity information provided by the patients. All non-Asian patients were White.

cEastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status Scale scores range from 0 to 5 (higher scores reflect greater disability). A score of 0 indicates fully active; 1, restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory.

dCalculated using a 2-sided stratified log-rank test.

Adverse Events

The median number of treatment cycles administered was 8 (range, 1-32) in the serplulimab group compared with 6 (range, 1-36) in the placebo group. The median duration of treatment exposure was 22.0 weeks (range, 0.1-107.7 weeks) in the serplulimab group compared with 16.4 weeks (range, 0.1-106.1 weeks) in the placebo group.

Treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in 95.6% of patients in the serplulimab group (82.5% for grade ≥3) compared with 97.4% of patients in the placebo group (80.1% for grade ≥3) (eTable 4 in Supplement 2). Common treatment-emergent adverse events (reported in ≥10% of patients in either group) appear in eTable 5 in Supplement 2.

Treatment-related adverse events (related to serplulimab or placebo) were reported by 272 patients (69.9%) in the serplulimab group compared with 110 patients (56.1%) in the placebo group; the most common adverse events were anemia, decreased white blood cell count, decreased neutrophil count, and decreased platelet count (Table 3). Treatment-related adverse events that were grade 3 or higher occurred in 129 patients (33.2%) in the serplulimab group compared with 54 patients (27.6%) in the placebo group (Table 3). The most common grade 3 or higher treatment-related adverse events were decreased neutrophil count (14.1% in the serplulimab group compared with 13.8% in the placebo group), decreased white blood cell count (8.5% vs 8.7%, respectively), decreased platelet count (6.2% vs 8.2%), and anemia (5.4% vs 5.6%).

Table 3. Treatment-Related Adverse Events in the Adverse Event Seta.

| Patients who experienced treatment-related adverse events, No. (%)b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any gradec | Grade ≥3d | |||

| Serplulimab (n = 389) | Placebo (n = 196) | Serplulimab (n = 389) | Placebo (n = 196) | |

| Any treatment-related adverse eventa | 272 (69.9) | 110 (56.1) | 129 (33.2) | 54 (27.6) |

| Anemia | 84 (21.6) | 36 (18.4) | 21 (5.4) | 11 (5.6) |

| Decreased white blood cell count | 78 (20.1) | 33 (16.8) | 33 (8.5) | 17 (8.7) |

| Decreased neutrophil count | 77 (19.8) | 35 (17.9) | 55 (14.1) | 27 (13.8) |

| Decreased platelet count | 59 (15.2) | 36 (18.4) | 24 (6.2) | 16 (8.2) |

| Hypothyroidism | 58 (14.9) | 5 (2.6) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Nausea | 50 (12.9) | 28 (14.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Increased alanine aminotransferase level | 46 (11.8) | 19 (9.7) | 4 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) |

| Hyperthyroidism | 44 (11.3) | 6 (3.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Increased aspartate aminotransferase level | 38 (9.8) | 21 (10.7) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (1.0) |

| Decreased lymphocyte count | 26 (6.7) | 8 (4.1) | 8 (2.1) | 2 (1.0) |

| Neutropenia | 25 (6.4) | 10 (5.1) | 17 (4.4) | 9 (4.6) |

| Hyperglycemia | 24 (6.2) | 6 (3.1) | 8 (2.1) | 0 |

| Leukopenia | 21 (5.4) | 9 (4.6) | 10 (2.6) | 4 (2.0) |

| Hyponatremia | 17 (4.4) | 5 (2.6) | 9 (2.3) | 2 (1.0) |

Adverse events related to serplulimab or placebo.

Adverse events related to serplulimab or placebo. Adverse events were graded according to version 5.0 of the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events.

Occurred in 10% or greater of patients in either group.

Occurred in 2% or greater of patients in either group.

The incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation were similar between the 2 groups (8.0% in the serplulimab group compared with 7.7% in the placebo group; eTable 4 in Supplement 2). Nineteen patients (4.9%) in the serplulimab group compared with 8 patients (4.1%) in the placebo group discontinued treatment due to treatment-related adverse events. Death due to treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in 30 patients (7.7%) in the serplulimab group compared with 20 patients (10.2%) in the placebo group (eTable 4 in Supplement 2). Three patients (0.8%) died of adverse events attributed to serplulimab, including those with acute coronary syndrome, pyrexia, and a decreased platelet count. One patient (0.5%) died of an adverse event (thrombocytopenia) attributed to placebo. All 4 treatment-related adverse events leading to death were immune related (eTables 4 and 6 in Supplement 2).

Immune-related adverse events were reported in 144 patients (37.0%) in the serplulimab group compared with 36 patients (18.4%) in the placebo group (eTable 4 in Supplement 2). Grade 3 or higher immune-related adverse events occurred in 37 patients (9.5%) in the serplulimab group compared with 11 patients (5.6%) in the placebo group (eTable 6 in Supplement 2). Immune-related adverse events with a rate of 5% or higher in any group were hypothyroidism (11.6% in the serplulimab group compared with 1.5% in the placebo group) and hyperthyroidism (9.0% vs 3.1%, respectively) (eTable 6 in Supplement 2). Infusion-related reactions occurred in 7 patients (1.8%) in the serplulimab group compared with 1 patient (0.5%) in the placebo group.

Pneumonia was reported in 8.2% of patients in each group (32 cases in the serplulimab group vs 16 cases in the placebo group). Grade 3 or higher treatment-related adverse event of pneumonia was reported in 1% (4 cases in the serplulimab group compared with 2 cases in the placebo group). Pneumonia with an immune-mediated mechanism was reported by 3 patients (0.8%) in the serplulimab group compared with 1 patient (0.5%) in the placebo group. One patient in each group experienced grade 3 or higher immune-related pneumonia (eTable 6 in Supplement 2).

Discussion

In this double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 randomized clinical trial, serplulimab plus chemotherapy as a first-line treatment significantly improved overall survival compared with placebo plus chemotherapy in patients with extensive-stage SCLC. To our knowledge, this is the first phase 3 trial demonstrating overall survival benefits of a PD-1 inhibitor in combination with chemotherapy as a first-line treatment for patients with extensive-stage SCLC.

Phase 3 trials of the PD-L1 inhibitors atezolizumab and durvalumab in combination with chemotherapy showed superior efficacy and significantly prolonged overall survival compared with chemotherapy alone in patients with previously untreated extensive-stage SCLC.6,11 Based on these trials, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the 2 combination therapies as the standard first-line treatment for patients with extensive-stage SCLC.8,9 Adding the PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab to the standard first-line chemotherapy regimen (etoposide and a platinum-based agent) significantly improved progression-free survival in patients with extensive-stage SCLC, as well as prolonged the duration of response.12

In the current trial, patients treated with the PD-1 inhibitor serplulimab plus chemotherapy showed significantly longer overall survival than those treated with placebo plus chemotherapy. The secondary efficacy outcomes, including progression-free survival, objective response rate, and duration of response, all favored the serplulimab group, suggesting that PD-1 inhibition combined with chemotherapy may be beneficial during the first-line treatment of patients with extensive-stage SCLC.

Across the prespecified subgroups, treatment with serplulimab plus chemotherapy consistently prolonged overall survival. The survival benefits of adding serplulimab to chemotherapy were observed in patients across both age subgroups (≥65 years and <65 years). In addition, the data were inconclusive regarding the predictive potential of PD-L1 expression, consistent with findings from previous studies.6,12,17 In this trial, 19.8% of patients were never smokers; this proportion was higher than the proportions of patients in previous multinational trials with larger fractions of non-Asian patients (range, 3.0%-8.8%),5,12,16,18 but consistent with those reported from clinical trials and observational studies conducted in China (range, 22.0%-37.0%).19,20,21,22,23 In the current trial, 68.4% patients were Chinese, and the percentage of never smokers in the Chinese population was 25.0%. The higher percentage of never smokers among Chinese patients with extensive-stage SCLC is likely due to the prevalent exposure to second-hand smoke.24 An improvement in overall survival was seen in this unique patient subgroup, consistent with that in the overall population.

Serplulimab binds to different epitopes in PD-1 compared with nivolumab and pembrolizumab.25 Serplulimab exhibited a higher affinity to human PD-1 than nivolumab and pembrolizumab, as well as a greater potency to block PD-L1 and PD-L2 signaling than nivolumab.25 In the in vivo models, serplulimab inhibited tumor growth at a lower dose than nivolumab.25 The mechanisms underlying the better survival outcome with serplulimab remain unknown, while the preclinical findings provide directions for future studies.

The incidence and severity of treatment-emergent adverse events were similar between the 2 groups. Adverse events attributed to serplulimab reflect the toxic effects frequently observed with immunotherapy in patients with SCLC.5,6,12 Pneumonia occurred at a frequency similar to other PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors.5,6,12 Most immune-related adverse events occurred in a small percentage of patients (<5%), and the most frequent events, hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism, may be considered a drug class–related rather than drug-specific effect.5,6,12,18

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, this trial did not include a head-to-head comparison of serplulimab vs atezolizumab or durvalumab added to chemotherapy because atezolizumab or durvalumab plus chemotherapy had not been approved for patients with extensive-stage SCLC in China prior to the initiation of this trial.

Second, only a small number of patients with brain metastases were enrolled, perhaps resulting from the requirement of asymptomatic and stable brain metastases at trial entry.

Third, carboplatin, which was chosen for its lower toxicity compared with cisplatin, was the only platinum-based agent evaluated in the trial.26

Fourth, the duration of follow-up was relatively short by the date of data cutoff, especially for the non-Asian population (median, 9.1 months; range, 0.2-18.0 months). Updated analyses with longer follow-up duration should be reported in the future when available.

Conclusions

Among patients with previously untreated extensive-stage SCLC, serplulimab plus chemotherapy significantly improved overall survival compared with chemotherapy alone, supporting the use of serplulimab plus chemotherapy as the first-line treatment for this patient population.

Trial protocol

eMethods

eTable 1. Detailed Reasons for Excluding Patients Who Did Not Meet Eligibility Criteria

eTable 2. Summary of Subsequent Anticancer Treatment After First Disease Progression

eTable 3. Tumor Response According to Investigator Assessments per RECIST Version 1.1

eTable 4. Summary of Treatment-emergent Adverse Events

eTable 5. Common Treatment-emergent Adverse Events Reported by ≥10% Patients in the Adverse Event Set

eTable 6. Immune-related Adverse Events

eFigure. Progression-free Survival According to Investigator Assessments per RECIST Version 1.1

Nonauthor collaborators

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Rudin CM, Brambilla E, Faivre-Finn C, Sage J. Small-cell lung cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):3. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-00235-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society . Cancer facts and figures 2021. Accessed January 10, 2022. https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancer-facts-figures-2021.html

- 3.Socinski MA, Smit EF, Lorigan P, et al. Phase III study of pemetrexed plus carboplatin compared with etoposide plus carboplatin in chemotherapy-naive patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(28):4787-4792. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.1548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossi A, Di Maio M, Chiodini P, et al. Carboplatin- or cisplatin-based chemotherapy in first-line treatment of small-cell lung cancer: the COCIS meta-analysis of individual patient data. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(14):1692-1698. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.4905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldman JW, Dvorkin M, Chen Y, et al. ; CASPIAN investigators . Durvalumab, with or without tremelimumab, plus platinum-etoposide versus platinum-etoposide alone in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (CASPIAN): updated results from a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(1):51-65. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30539-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu SV, Reck M, Mansfield AS, et al. Updated overall survival and PD-L1 subgroup analysis of patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer treated with atezolizumab, carboplatin, and etoposide (IMpower133). J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(6):619-630. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.01055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.AstraZeneca . Press release: Imfinzi approved in the EU for the treatment of extensive-stage small cell lung cancer. Accessed December 21, 2021. https://www.astrazeneca.com/content/astraz/media-centre/press-releases/2020/imfinzi-approved-in-EU-for-small-cell-lung-cancer.html

- 8.AstraZeneca . Press release: Imfinzi approved in the US for extensive-stage small cell lung cancer. Accessed December 21, 2021. https://www.astrazeneca.com/media-centre/press-releases/2020/imfinzi-approved-in-the-us-for-extensive-stage-small-cell-lung-cancer.html

- 9.Roche . Press release: FDA approves Roche’s Tecentriq in combination with chemotherapy for the initial treatment of adults with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer. Accessed December 21, 2021. https://www.roche.com/media/releases/med-cor-2019-03-19.htm

- 10.Roche . Press release: European Commission approves Roche’s Tecentriq in combination with chemotherapy for the initial treatment of people with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer. Accessed December 21, 2021. https://www.roche.com/media/releases/med-cor-2019-09-06b.htm

- 11.Paz-Ares L, Chen Y, Reinmuth N, et al. Durvalumab, with or without tremelimumab, plus platinum-etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: 3-year overall survival update from CASPIAN. ESMO Open. 2022;7(2):100408. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rudin CM, Awad MM, Navarro A, et al. ; KEYNOTE-604 Investigators . Pembrolizumab or placebo plus etoposide and platinum as first-line therapy for extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: randomized, double-blind, phase III KEYNOTE-604 study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(21):2369-2379. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.00793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chao TY, Ho CL, Cheng WH, et al. A novel anti-PD-1 antibody HLX10 study led to the initiation of combination immunotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(suppl 9):ix109-ix110. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz438.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu L, Li X, Wang J, et al. Efficacy and safety evaluation of HLX10 (a recombinant humanized anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody) combined with albumin-bound paclitaxel in patients with advanced cervical cancer who have progressive disease or intolerable toxicity after first-line standard chemotherapy: a single-arm, open-label, phase 2 study. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(suppl 15):e17510. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.e17510 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qin S, Li J, Zhong H, et al. Efficacy and safety of HLX10, a novel anti-PD-1 antibody, in patients with previously treated unresectable or metastatic microsatellite instability-high or mismatch repair-deficient solid tumors: a single-arm, multicenter, phase 2 study. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(15)(suppl):2566-2566. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.2566 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horn L, Mansfield AS, Szczęsna A, et al. ; IMpower133 Study Group . First-line atezolizumab plus chemotherapy in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(23):2220-2229. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paz-Ares L, Goldman JW, Garassino MC, et al. PD-L1 expression, patterns of progression and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) with durvalumab plus platinum-etoposide in ES-SCLC: results from CASPIAN. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(suppl 5):v928-v929. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz394.089 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spigel DR, Vicente D, Ciuleanu TE, et al. Second-line nivolumab in relapsed small-cell lung cancer: CheckMate 331☆. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(5):631-641. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.01.071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng Y, Wang Q, Li K, et al. Anlotinib vs placebo as third- or further-line treatment for patients with small cell lung cancer: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Br J Cancer. 2021;125(3):366-371. doi: 10.1038/s41416-021-01356-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fan Y, Zhao J, Wang Q, et al. Camrelizumab Plus Apatinib in Extensive-Stage SCLC (PASSION): a multicenter, two-stage, phase 2 trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16(2):299-309. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu X, Jiang T, Li W, et al. Characterization of never-smoking and its association with clinical outcomes in Chinese patients with small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2018;115:109-115. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang LL, Hu XS, Wang Y, et al. Survival and pretreatment prognostic factors for extensive-stage small cell lung cancer: a comprehensive analysis of 358 patients. Thorac Cancer. 2021;12(13):1943-1951. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.13977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang J, Zhou C, Yao W, et al. ; CAPSTONE-1 Study Group . Adebrelimab or placebo plus carboplatin and etoposide as first-line treatment for extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (CAPSTONE-1): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(6):739-747. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00224-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids . Global Adult Tobacco Survery: fact sheet China 2018. Accessed July 20, 2022. https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/assets/global/pdfs/en/GATS_China_2018_FactSheet.pdf

- 25.Issafras H, Fan S, Tseng CL, et al. Structural basis of HLX10 PD-1 receptor recognition, a promising anti-PD-1 antibody clinical candidate for cancer immunotherapy. PLoS One. 2021;16(12):e0257972. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santana-Davila R, Szabo A, Arce-Lara C, Williams CD, Kelley MJ, Whittle J. Cisplatin versus carboplatin-based regimens for the treatment of patients with metastatic lung cancer: an analysis of Veterans Health Administration data. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9(5):702-709. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol

eMethods

eTable 1. Detailed Reasons for Excluding Patients Who Did Not Meet Eligibility Criteria

eTable 2. Summary of Subsequent Anticancer Treatment After First Disease Progression

eTable 3. Tumor Response According to Investigator Assessments per RECIST Version 1.1

eTable 4. Summary of Treatment-emergent Adverse Events

eTable 5. Common Treatment-emergent Adverse Events Reported by ≥10% Patients in the Adverse Event Set

eTable 6. Immune-related Adverse Events

eFigure. Progression-free Survival According to Investigator Assessments per RECIST Version 1.1

Nonauthor collaborators

Data sharing statement