Abstract

Constipation in children is a major health issue around the world, with a global prevalence of 9.5%. They present to clinicians with a myriad of clinical signs. The Rome IV symptom-based criteria are used to diagnose functional constipation. Functional constipation is also a huge financial burden for healthcare system and has a detrimental impact on health-related quality of life of children. There are various risk factors identified globally, including centrally connected factors such as child abuse, emotional and behavioral issues, and psychological stress. Constipation is also precipitated by a low-fiber diet, physical inactivity, and an altered intestinal microbiome. The main pathophysiological mechanism is stool withholding, while altered rectal function, anal sphincter, pelvic floor, and colonic dysfunction also play important roles. Clinical evaluation is critical in making a diagnosis, and most investigations are only required in refractory patients. In the treatment of childhood constipation, both nonpharmacological (education and de-mystification, dietary changes, toilet training, behavioral interventions, biofeedback, and pelvic floor physiotherapy), and pharmacological (osmotic and stimulant laxatives and novel drugs like prucalopride and lubiprostone) interventions are used. For children with refractory constipation, transanal irrigation, botulinum toxin, neuromodulation, and surgical treatments are reserved. While frequent use of probiotics is still in the experimental stage, healthy dietary habits, living a healthy lifestyle and limiting exposure to stressful events, are all beneficial preventive measures.

Keywords: Constipation, Children, Functional gastrointestinal disorders, Psychological stress, Treatment, Surgical interventions

Core Tip: Constipation is a public health problem. It has a high prevalence and a multitude of risk factors. The main pathophysiological mechanisms are stool withholding and colonic and anorectal dysfunction in younger and older children, respectively. Constipation is a clinical diagnosis based on the Rome IV criteria. Polyethylene glycol-based therapy is the mainstay in the management of constipation, while other osmotic and stimulant laxatives are used as adjunct therapies. Colonic washouts and surgical interventions are reserved for refractory constipation. A well-planned preventive strategy is useful in preventing functional constipation in children and would be able to reduce healthcare costs and improve health-related quality of life.

INTRODUCTION

Childhood functional constipation (FC) is characterized by the presence of infrequent, and painful bowel motions, fecal incontinence, stool withholding behavior, and occasional passage of large diameter stools. Epidemiologically it amounts to a global health problem as developed and developing countries show a high prevalence[1]. Children with constipation suffer from a variety of symptoms unrelated to their gastrointestinal system and the disease detrimentally affects their quality of life, often unrecognized by the healthcare systems[2]. A large sum of public funds is also being spent on caring for children with constipation due to repeated hospital admissions, emergency room visits, and regular clinic visits because of recurrent exacerbations of their symptoms[3]. All these factors demand a fresh look at childhood constipation. Therefore, in this frontier article, we critically review the current literature to develop a new paradigm on epidemiology and risk factors, pathophysiology, investigations, and management of children with constipation.

Identifying children with constipation: The Rome criteria

Constipation had been defined using a large number of definitions. An unambiguous, universal definition was needed for epidemiological, pathophysiological, and clinical trials at the turn of the century. These demands paved the way to defining functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) in the Rome process. In 2006, Rome III criteria were established to diagnose childhood constipation. The duration of constipation was reduced from 3 mo used in Rome II criteria to 2 mo, clearly defining constipation in a more practical way[4]. Rome III criteria were more useful in clinical diagnosis of constipation in children and has a good construct validity. However, the inter- and intra-observer reliability of Rome criteria has been poor, indicating the necessity to develop more robust, clinically valuable criteria[5]. The Rome IV criteria were released in 2016[6] (Table 1). Apart from changing the duration of symptoms from 2 mo to 1 mo from onset to diagnosis, the other criteria remain as the same in Rome III. The change has not increased the number of children diagnosed with constipation, and both Rome III and Rome IV criteria were in excellent agreement[7]. However, the reduction of the duration of symptoms required to diagnose constipation is an important move as it is essential to start therapeutic interventions as early as possible to minimize both physiological and psychological consequences of late diagnosis and treatments.

Table 1.

Rome IV diagnostic criterial for constipation in children

|

Diagnostic criteria must include at least 2 of the following features of constipation in a child with a development age of at least 4 yr with insufficient criteria to diagnose irritable bowel syndrome

|

| Two or fever defecations in the toilet per week |

| History of retentive posturing or excessive volitional stool retention |

| History of painful or hard bowel motion |

| Presence of a large fecal mass in the rectum |

| History of large diameter stools which may obstruct the toilet |

| After appropriate evaluation, the fecal incontinence cannot be explained by another medical condition |

Epidemiology

FC is a common FGID throughout childhood. In the last 2 decades, several systematic reviews reported that the prevalence of FC changes with the definition used, but prevalence does not change with age or sex and FC is found all over the world. The prevalence of FC is lower in Asian children compared to American and European children. Although the exact reason for this observation is not clear, it is possible that dietary, cultural factors, and social factors related to toilet training may play a role[1,8]. The relationship between socioeconomic status and FC is controversial. Several studies have reported that FC is not associated with low level of parental education, low family income, or maternal and paternal employment[9,10]. However, a Nigerian study reported a higher prevalence among children with low social class[11]. Other important factors reported in epidemiological studies include positive family history and health problems among family members[9,10]. Recent studies using Rome IV criteria reported a significantly high prevalence of FC in infants and young children. A study from China noted that 7% of children aged 0-4 years were suffering from FC and among infants in Malaysia it was 1.1%[12,13]. A systematic review on FGIDs in infants and toddlers reported a prevalence of FC as 11.6% at the age of 3 mo according to Rome III criteria[14].

Risk factors for constipation

Several risk factors for FC have been identified. All these factors finally lead to anorectal dysfunction and fecal retention in the rectum and the colon leading to passage of infrequent, hard, and painful stools. It is understood that FC is a disorder of gut brain interactions. Therefore, the risk factors involving childhood FC is divided into two main categories namely, centrally mediated and gut related mechanisms.

CENTRAL RISK FACTORS

Stressful life event

Subtle perceived stressors, such as separation from best friend, failure in exam in school, being bullied at school, and change of school and home related stressors, such as divorce or separation of parents, loss of job of a parent, and severe illnesses in the family may precipitate FC[15]. Other home related risk factors reported were frequent domestic fights, marital disharmony, and sibling rivalry[16,17].

Abuse and child maltreatment

Psychological trauma associated with abuse and maltreatment is known to associate with FC. A study from Sri Lanka reported exposure to all three major forms of abuse (physical, emotional, and sexual) predispose children to develop FC[18]. It also showed that these children had more severe bowel symptoms and somatization. At the molecular level, abuse influences DNA methylation and lead to changes in epigenetic structure and mechanisms[19]. Stress generated during the period of exposure to abuse and psychological influences that last longer and changes in the epigenetic structure may contribute to permanent alterations in the dialogue between the brain and the large bowel leading to FC.

Other psychological and behavioral factors

Studying children with FC using the child behavior check list, several authors reported behavioral traits such as internalization and externalization are more frequent among these children[20,21]. FC is also associated with psychological maladjustment, anxiety, and depression[22-24]. Using the strength and difficulty questionnaire, Cagan-Appak and co-workers[25] noted emotional and peer problems to be more common among children with FC.

Parental rearing style and psychological state

The rearing style of parents is a significant factor during the early life of a child, particularly during the time of toilet training. Parents with high autonomy may try to train their children too strictly and parents with lower autonomy could neglect toilet training leading to fecal retention and constipation.

Studies have noted that parents of children with FC have strict and authoritative parenting styles and are over protective and have rigid attitudes[21,25,26]. In addition, FC in children is also associated with depression and anxiety of parents[25]. All these factors could negatively affect the developing minds of children, adversely affecting their brain-gut connections and lead to FC.

Toilet training

Poor toilet training is a major risk factor for the development of FC in toddlers. Toilet training/potty training should be started between 18-30 mo[27]. However, socioeconomic factors and cultural norms also play a significant role in determination of the timing. Indeed, a comparative study between children from Vietnam and Sweden reported that toilet training was started at 6 mo of age in 89% of Vietnamese children and was achieved in 98% of children by 24 mo, whereas only 5% of Swedish children had started training by 24 mo[28]. Some young children develop stool toileting refusal due to fear of defecation using the toilet or strained family dynamics which enhances withholding behavior[27].

PERIPHERAL RISK FACTORS

Diet

Several dietary factors have been identified as increasing the risk to develop FC. Fiber is an important component of the human diet. Several studies have shown an association between consumption of a diet low in fiber content, including fruits and vegetables, and FC in children[9,10,29]. An observational study noted an association between consumption of fast food and FC[30]. Cow’s milk protein allergy is also considered as a potential risk factor for FC in children. Several studies have reported the association between consumption of cow’s milk and FC[31-33]. In an elegant study, Borrelli et al[32] showed that children with cow’s milk allergy-related constipation had increased rectal mast cell density and increased spatial interaction between mast cells and nerve fibers. In addition, anorectal motor abnormalities were found which may result in constipation. These abnormalities resolved on an elimination diet.

Physical activity

Physical activity is an integral part of day-to-day life and has a number of positive health benefits including improved cardiometabolic and bone health. Sedentary lifestyle has been associated with FC[30,34]. Likewise, others have also noted the beneficial effects of physical activity in preventing FC[35,36].

Abnormal microbiota

The microbiome of the large intestine plays a crucial role in health and disease. Its concentration is estimated up to 1011-1012 cell/g luminal content in the large bowel[37]. This large body of live organisms serves the human body with a variety of physiological functions including digestion and absorption, immunity, prevention of growth of pathogenic organisms, and production of multiple bioactive products. In addition, the microbiome significantly contributes to the stool bulk. de Meij and co-workers[38] reported increased Bacteroides (B. fragilis, B. ovatus) and Bifidobacteria (B. longum) in children with FC. Another study reported increased Bifidobacteria and Clostridia in children with FC[39]. In contrast a reduction of Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli were noted in adults with FC[40]. When summarizing these data, it is not possible to clearly identify a pattern of organisms associated with FC. Therefore, there is no definitive evidence that the microbiome contributes significantly to predispose children to develop FC.

Pathophysiology

The etiology of FC in children is largely unknown. However, the understanding of the potential pathophysiological mechanisms is rapidly advancing with the aid of evolving novel technological advances, such as high resolution anorectal and colonic manometry and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) imaging. Growing evidence suggests that voluntary withholding, anorectal dysfunctions (altered sensation, increased compliance, anal achalasia, and dyssynergic defecation), colonic dysfunctions (altered electrophysiology and altered motility), and central mechanisms operating through the brain-gut-microbiota axis and hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis contribute to the pathophysiological mechanisms.

STOOL WITHHOLDING

Stool withholding is the commonest pathophysiological mechanism for developing FC in young children. Faulty toilet training and painful defecation due to passage of hard and large fecal masses lead children to withhold stools. The rectal mucosa, which is designed to absorb water in stools, absorbs water in feces, and the fecal mass in the rectum becomes rock hard and difficult to evacuate. Occasional passage of the fecal mass causes pain in the perianal region, which further aggravates withholding. The rectal wall stretches due to the enlarging fecal mass and accommodates more fecal matter, sometimes leading to a megarectum, which further reduces the desire to pass stools, and augmenting symptoms[41]. Stretched rectal walls may lose its normal contractility, which is necessary to propel feces. All these pathophysiological factors set up a vicious cycle of stool withholding, painful defecation, and alteration of rectal physiology.

ALTERED RECTAL COMPLIANCE

Increased rectal compliance was noted in children with long-standing fecal impaction. It is difficult to determine whether altered rectal compliance is a primary pathology leading to fecal impaction or secondary to bowel damage caused by prolonged fecal stasis. Children with higher rectal compliance have more severe symptoms, such as fecal incontinence[42]. However, it had been shown that increased rectal compliance has no relationship to the treatment success by noticing that children with high rectal compliance also recovered fully despite their abnormal physiology[42]. In addition, it is important to note that high rectal compliance persists in some children despite them being successfully treated and having no features of FC for many years[43].

ANAL SPHINCTER AND PELVIC FLOOR DYSFUNCTION

During the act of defecation, when the intra-rectal pressure rises to a critical point anal sphincters need to be relaxed to facilitate expulsion of feces. In a subset of children with FC, a paradoxical contraction of external anal sphincter was observed with an increase of intra-rectal pressure, widely known as dyssynergic defecation. Both conventional manometry and the novel three-dimensional high-resolution anorectal manometry have shown the existence of dyssynergic defecation due to dysfunction of the sphincter complex, puborectalis muscle, and internal anal sphincter achalasia[44]. Internal anal sphincter achalasia is a rare condition, which could present with refractory FC. The exact pathophysiological mechanism has not been delineated and the condition is thought to be due to altered intramuscular innervation leading to a dysfunctional anal sphincter[45].

COLONIC DYSFUNCTION

One of the main physiological functions of the colon is to store and propel fecal matter. Several pathological processes, such as neuropathies, myopathies, and reduction of the number of Intestinal Cells of Cajal, which are considered as the pacemaker cells of the large intestine, could contribute to poor colonic transit. Studies have shown that children with intractable constipation have slow colonic transit using nuclear transit studies[46]. Other methods, such as conventional and high-resolution colonic manometry studies, have shown the lack of high amplitude propagatory contractions, reduction in retrograde cyclic motor pattern, and failure to induce a meal response with cyclic motor pattern in children with constipation[47]. Accumulation of feces might lead to dilatation and elongation of the colon leading to premature termination of high amplitude propagatory contractions and the release of nitric oxide, which inhibits myenteric neurons inducing secondary colonic dysfunction[48].

IMPACT OF FC

Economic and burden on hospitals

Being one of the commonest FGIDs, FC has serious ramifications on existing healthcare systems across the world. Emergency room visits for fecal impaction and abdominal pain, regular clinic visits, regular medications (which could be needed for months), sophisticated investigations, such as anorectal and colonic manometry, and occasional surgical intervention in refractory cases, contribute to the cost. In addition. analysis of national emergency department data from the US showed that fecal impaction due to FC is an important reason to visit the emergency room[49]. In a birth cohort study of children younger than 5 years, FC was reported to have the highest number of first-time medical visits compared to other chronic gastrointestinal disorders, including abdominal pain and gastroesophageal reflux[50]. A study conducted in Victoria, Australia, noted that FC represented 6.7% of annual hospital admission with annual cost of 5.5 million Australian dollars[3]. Using a nationally representative household survey, the annual cost of managing FC in children in the US was noted to be 3.9 billion for urinary stone disease[51]. All these studies indicate the economic burden of FC on healthcare systems and on national healthcare expenditure.

QUALITY OF LIFE AND IMPACT ON EDUCATION

Health related quality of life (HRQoL) is an indirect measure of the impact of a disease in a given individual. It is calculated as a composite numerical figure, including several components such as social, emotional, physical, and school functions. HRQoL has also been identified as one of the secondary outcome measures in clinical trials of FC. Several studies have reported poor HRQoL in children with FC. In a case-controlled study, Youssef reported that children with FC have a lower HRQoL than children with severe organic diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease or gastroesophageal reflux, indicating the magnitude of the problem[52]. A hospital-based, case-control study from China also reported poor physical, emotional, social, and school related quality of life in children with FC[53]. A recent systematic review and a meta-analysis has clearly emphasized the negative impact of FC on HRQoL in children[2]. There are multitude of reasons for this observation. Symptoms of FC, such as pain during defecation and lower abdominal discomfort due to fecal impaction, could be troublesome to children. Associated fecal incontinence (FI) also leads to significant embarrassment and shame. Finally, psychological comorbidities associated with FC, including emotional and behavioral issues, maladjustment, and abnormal personality traits, also could negatively affect the quality of life of children[20,22,23].

Clinical evaluation

A thorough history and a complete physical examination are sufficient to diagnose constipation. The main components of the clinical history are given in the Table 2. The modified Bristol Stool Scale Form can be used to identify the type of stools in children to facilitate the diagnosis[54]. A complete physical examination, specifically designed to spot general growth and dysmorphic syndromes that could be associated with constipation, should be undertaken as a part of clinical evaluation (Table 3). Alarm features that indicate possible organic diseases also will be revealed during clinical evaluation (Table 4). Presence of such features demands further evaluation of the child for possible organic disorders. In the majority of children with FC, it is not necessary for such investigations; however, a thorough understanding of anorectal physiology, neurophysiology, and morphology is essential when symptoms become refractory despite adequate medical interventions.

Table 2.

Clinical history-taking

| Component and subcomponents |

| Onset of symptoms and duration of the disease |

| Bowel habits |

| Frequency of stools |

| Nature of the stools |

| Fecal incontinence |

| Blood in stools |

| Passage of meconium |

| Other associated symptoms |

| Withholding behavior |

| Somatic symptoms |

| Past medical and surgical history |

| Bowel surgeries |

| Medications |

| Neuromuscular diseases |

| Dietary history |

| Fiber continent in the diet |

| Frequency of junk food |

| Family history |

| Psychological history |

| Developmental history |

Table 3.

Physical examination

| Component and subcomponents |

| General examination |

| Assessment of growth |

| Assessment of development |

| Abdominal examination |

| Abdominal distension |

| Surgical scars |

| Palpable fecal masses |

| Perianal observation |

| Position of the anus |

| Perianal excoriation and dermatitis |

| Scars, fissures, and tags |

| Patulous anus |

| Neurological evaluation |

| Spine |

| Lower limb neurological assessment |

Table 4.

Red flag features and their clinical relevance

|

Features and subfeatures

|

| Hirschsprung disease |

| Delayed passage of meconium |

| Positive family history |

| Ribbon like stools |

| Significant abdominal distension |

| Child sexual abuse |

| Extreme fear of anal examination |

| Scars in the perianal region |

| Fissures in children > 2 yr of age |

| Neurological abnormalities |

| Hair tuft/hemangioma/scars on spine |

| Abnormal anal and cremasteric reflex |

| Deficiencies in lower limb neurology |

| Developmental delay |

| Other organic disorders |

| Bilious vomiting |

| Blood in stools |

| Failure to thrive |

| Malposition of the thyroid gland |

COMMON INVESTIGATIONS

Several reviews have summarized the value of plain abdominal radiograph in identifying FC[55,56]. According to these reviews and clinical experiences, a plain abdominal radiograph does not provide any useful insights for management. Similarly, most of the routine blood tests, such as thyroid function tests, screening for cow’s milk allergy or celiac disease, and checking for electrolyte abnormalities (hypokalemia, hypercalcemia) are not very helpful in day-to-day management of FC[55].

COLONIC FUNCTION

Colonic transit time

Colonic transit studies measure the ability of the colon to propel fecal matter and are useful in assessing overall colonic motor function. Delayed colonic transit time (CTT) was noted in children with FC due to anorectal dysfunction as well as colonic dysfunction[57]. Currently CTT is utilized only to differentiate constipation associated fecal incontinence from functional nonretentive fecal incontinence when a clinical differentiation is not possible[56].

Colonic manometry

Colonic physiology in children with FC is poorly understood. High-resolution colonic manometry is a valuable method to study physiological function, including motor and propulsive activity of the colon. In the beginning, the fasting motility is recorded, and the gastrocolic reflexes are assessed after a meal. Bisacodyl is instilled into the colon only when high amplitude propagatory contractions are not identified after a meal. Absence of high amplitude propagatory contractions, generalized colonic hypomotility, absence of response stimulant laxatives, and lack of increase in the cyclic retrograde propagatory motor patterns after a test meal are characteristic features in children with FC indicating neuromuscular dysfunction. In addition, premature termination of the propagation of contractions possibly indicates the presence of a segmental dysmotility[58]. These observations are helpful in decision making in management, such as surgery of refractory cases. However, there are several limitations, including limited availability, need for general anesthesia, high initial cost, and lack of normal data in children.

ANORECTAL FUNCTION

Anorectal manometry

Anorectal manometry provides details on the length of the anal canal, rectal sensation, and squeeze sphincter pressures, rectoanal reflexes, and pressure changes in attempted balloon expulsion mimicking defecation. However, its main use is to exclude Hirschsprung disease in young children with constipation by demonstrating the absence of the rectoanal inhibitory reflex[55]. It is generally measured using either solid state or water perfused catheters.

Wireless motility capsule

The wireless motility capsule (WMC) is useful in measuring the transit through the different parts of the gastrointestinal transit. It is a non-invasive test that does not expose the patient to radiation. The pediatric studies using WMC, on the other hand are still in the early phase and have only been described as case studies[59]. The test is well tolerated up until the age of 8 years. WMC is beneficial in detecting the delayed colonic transit time in children with refractory constipation, and the results show a strong correlation with colonic transit time evaluated using radiopaque markers[60]. Therefore, the utility of WMC in children with FC should be investigated in future studies, particularly when FC is resistant to standard management strategies.

OTHER INVESTIGATIONS

Lower GI contrast studies in children are used to differentiate FC from Hirschsprung disease and assess the length of the aganglioinic segment in Hirschsprung disease. However, the test is insensitive, and once a transitional zone is detected, a biopsy is needed to confirm the diagnosis. Defecography is not useful in the day-to-day management of constipation in children as the procedure exposes children to a significant amount of radiation and rectoceles, and rectal intussusceptions are rare in children. Similarly endoscopy is also not recommended in children with FC[61]. Although the use of ultrasonography in diagnosing FC has been reported, further refinements of the technique are needed before it is used in current clinical practice[62]. MRI of the spine is only indicated in children who show features of intractable constipation and features suggestive of spinal anomaly indicated by a tuft of hair, hemangiomas, or scars in the lower spine and neurological signs in lower limbs.

Management

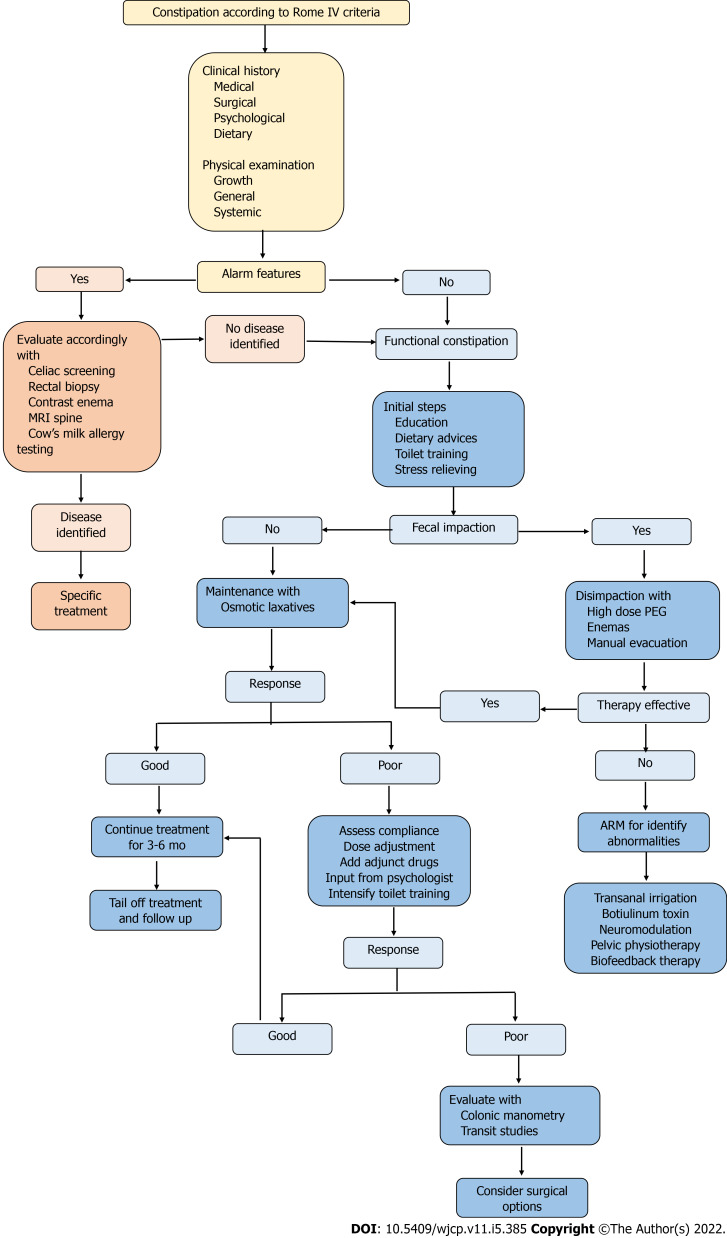

Clinical management of constipation has several facets. The main approaches are non-pharmacological interventions (education and demystification, dietary adjustment, toilet training, behavioral interventions, use of biofeedback, and pelvic floor physiotherapy), pharmacological interventions (oral and/or rectal laxatives, including novel drugs such as prucalopride and lubiprostone), and surgical interventions (antegrade enema and bowel resection), and other novel modalities, such as neuromodulation (Figure 1). The majority respond to one or combination of above-mentioned therapeutic strategies. It is crucial to understand that untreated or poorly managed children with FC tend to have significant complications. Therefore, it is quite important to treat these children effectively at the early stages to relieve symptoms.

Figure 1.

Management flow chart of childhood constipation.

POOR PROGNOSTIC FACTORS

Presence of poor prognostic factors may interfere with treatment success. Table 5 provides the possible factors that could influence prognosis[55]. It is imperative that the clinician looks into these factors at the initial assessment and use these factors in decision making while determining therapeutic options.

Table 5.

Factors negatively affect the prognosis of functional constipation

| Factor |

| Constipation during the 1st yr of life |

| Longer duration of symptoms before presentation |

| Low defecation frequency at presentation |

| Presence of fecal incontinence |

| Large diameter stools |

| Stool withholding |

| Nighttime urinary incontinence |

| Presence of fecal mass in abdomen/rectum |

| Prolonged colonic transit > 100 h |

| Failed balloon expulsion test |

CLEAN UP THE RECTUM AND COLON

The majority of children with FC have a large fecal mass in their rectum. Therefore, the first step in the management is to clean up the rectal fecal mass and the impacted colon as much as possible. This facilitates the passage of stools during the maintenance phase as the colon and rectum impacted with hard fecal matter may not respond to the drugs commonly used in the management of FC. In a comparative study, both polyethylene glycol (PEG, 1.5 g/kg) and enemas for 3-6 d were equally effective in disimpaction. Both modalities had similar frequency of adverse effects with the exception of fecal incontinence, which was significantly more common in the group receiving PEG[63]. However, the oral route is generally well tolerated in children and therefore should be the first line therapy when available. In children where medical therapy is not effective or the rectum is impacted with an enormous scybalous, manual evacuation of impacted feces in the rectum is recommended.

MAINTENANCE THERAPY

In the maintenance stage, children are encouraged to pass stools regularly while using laxatives for at least 2 mo. This is to keep stools soft and make defecations less painful and less frightening. After disimpaction, this is achieved by using both pharmacological and proven nonpharmacological interventions using a step-down model with gradual tailing off of laxatives. Once regular defecation pattern is established, children with FC are managed with regular use of toilet and a balanced diet with adequate fluid and fiber intake.

NONPHARMACOLOGICAL INTERVENTIONS

Toilet training

The majority (80%-100%) of young children with FC demonstrate features of stool withholding and most of the stool withholders (> 80%) refuse to pass stools in the toilet (stool toileting refusal)[64]. Parents should encourage their child to sit on the potty or toilet for 5 min after wakening and after lunch and dinner. They need to be instructed on proper seating method, how to keep legs and feet relaxed, how to relax the perineum, and how to strain to expel stools using a model toilet or a video. The process needs to be a conscious effort, and using mobile phones or tabs as rewards while sitting on the potty would be counterproductive. It is also imperative to counsel parents to reinforce the positive behavior of the child, especially when the child passes stools in the toilet/potty[65].

Behavioral and psychological intervention

There are many learned behavioral problems related to FC. They include toilet refusal, stress, and fear related to defecation. These behavior traits frequently lead to development and perpetuation of symptoms of FC. Therefore, in some children behavior therapy might be helpful in addition to medical treatment[66]. Novel therapeutic interventions, such as the use of principles of positive psychology, including resilience, optimism, and self-regulation providing a framework to achieve subjective well-being. These treatment modalities, when starting early in the disease process might be able to prevent the patient developing maladaptive coping habits, engage in high physical and psychological symptom reporting, and exhibit poor, costly disease outcomes[67]. These new therapeutic modalities need to be explored in children with FC early in the disease process before bowel and psychological damage take place leading to poor long-term prognosis.

Dietary interventions

Fiber is an important dietary component with significant long term health benefits. The current recommendation from the American Health Foundation is to consume at least “age in years plus 5 g – 10 g” of fiber per day for children over 2 years[68]. Low fiber intake is a risk factor to develop FC in children[10]. In the last decades, 9 different fiber types have been tried as therapeutic agents for children with FC. They include cocoa husk, glucomannan, partially hydrolyzed guar gum, combination of acacia fiber, corn fiber, soy fiber, psyllium fiber, and fructose, galactooligosaccharides, and inulin-type fructose. A systematic review studying 10 randomized trials showed some beneficial effects of using fiber in treating children with FC. However, due to different types of fibers, different study designs, and small sample size, it is difficult to make strong recommendations[69]. Indeed, the ESPGHAN/ NAPGHAN guideline recommends ensuring normal amount of dietary fiber intake for children with FC[55].

Probiotics

Dysbiosis is known to occur in children, although our knowledge of this important area is still in its infancy[38]. A systematic review published in 2017 assessed seven randomized controlled trials (RCTs) using probiotics for FC. In this systematic review the authors found that Lactobacillus rhamnosus casei Lcr35 is no more effective than a placebo in treating FC in children. None of the probiotics were effective in reducing frequency of fecal incontinence[70]. Other studies showed that Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG was not effective as adjunct therapy or with polyethylene glycol[71] in treating FC.

Other dietary modifications

Cow’s milk protein allergy had been considered as a possible associated factor with FC. Two studies evaluated the clinical utility of cow’s milk elimination diet in treating children with FC with variable results[72,73]. A recent trial conducted by Bourkheili et al[74], showed the efficacy of cow’s milk elimination diet in children who did not respond to laxatives. However, the open-label nature of the study leads to a high degree of bias in their findings. The ESPGHAN-NASPGHAN guideline recommends cow’s milk protein-free diet only in laxative resistant constipation and under the guidance of an expert[55]. Increasing water intake or hyperosmolar fluid has no significant effect on defecation frequency or improvement of consistency of stools[75]. The ESPGHAN-ESPGHAN guideline does not support the use of extra fluid intake in the treatment of FC[55]. Other studies of dietary interventions, such as Cassia Fistula emulsion and Descurainia Sophia seeds, showed high risk of bias and, therefore, could not recommended as therapeutic interventions[76,77].

Biofeedback and pelvic floor physiotherapy

Biofeedback gives a visual display of physiological monitoring of anorectal function while providing input by a therapist to retrain anorectal and perineal muscles. A systematic review concluded that biofeedback is not recommended for children with FC[78]. Similarly, the ESPGHAN-NASPGHAN guideline also does not recommend biofeedback as a therapeutic intervention for children with FC[55]. Pelvic floor physiotherapy uses motor relearning. The components of pelvic floor physiotherapy include supporting toilet training, increase awareness of sensation, and pelvic floor muscle training. A pragmatic trial using the Dutch pelvic floor physiotherapy protocol compared pelvic floor physiotherapy plus standard medical care with standard medical care. The primary outcome of the study was defined as the absence of FC according to the 6 Rome III criteria. In this study 24 out of 26 (92.3%) children receiving pelvic floor physiotherapy with standard medical care showed treatment success compared to 17/27 (63.0%) who received standard medical care (adjusted OR 11.7; 95%CI 1.8-78.3; P = 0.011)[79]. However, there are several limitations in this trial, including lack of blinding, small sample size, and alteration and adjustment of the protocol during the trial. Potential benefits of pelvic floor physiotherapy as a therapeutic option for FC need further elaboration.

Pharmacological interventions

Pharmacological interventions are the mainstay of therapy for childhood FC. There are several therapeutic agents that can effectively and safely be used either alone or in combination.

OSMOTIC LAXATIVES

A Cochrane systematic review reported that polyethylene glycol (PEG) was found to be superior to placebo, lactulose, and milk of magnesia to improve stool frequency[80]. In addition, they showed that a high dose of (0.7 g/kg) PEG was more effective at increasing stool frequency than a low dose (0.3 g/kg). The common adverse effects of PEG include flatulence, abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhea, and headache. Another meta-analysis found that PEG is also more effective in disimpaction than non-PEG laxatives, such as lactulose, magnesium hydroxide, and liquid paraffin[81]. Based on the current evidence, PEG is the most suitable drug for both disimpaction and maintenance of FC in children.

There are no RCTs comparing lactulose with placebo. Two trials compared lactulose with liquid paraffin[82,83]. When pooling the data using a fixed-effect model, liquid paraffin was shown to be more effective than lactulose in increasing stool frequency[80]. Other trials comparing lactulose with partially hydrolyzed guar gum found no difference in clinical efficacy between those therapeutic modalities and lactulose[84]. Lactulose is recommended to use as the first line maintenance therapy when PEG is not available[55].

STIMULANT LAXATIVES AND FECAL SOFTENERS

Bisacodyl is a stimulant laxative. It has a local prokinetic effect and stimulates intestinal secretion. Bisacodyl is a useful adjunct drug to osmotic laxatives in treating children with FC[55]. Senna is a natural laxative made from the leaves and fruits of the senna plant and is another stimulant laxative that is frequently used in treating children with FC. In a retrospective chart review from the US, it was noted that senna was effective as a laxative in the treatment of FC, and only 15% of the patients reported significant side effects, including abdominal cramps and diarrhea. None of the patients had to stop the laxative due to adverse effects[85]. Sodium picosulphate is the other available stimulant laxative used in clinical practice. Mineral oil is a time-tested fecal softener and is only recommended as an add-on therapy in the maintenance phase when the response to osmotic laxatives is suboptimal[55].

NOVEL THERAPEUTIC OPTIONS

Several prosecretory agents have shown to be effective in treating constipation in adults. They include prucalopride, lubiprostone, linaclotide, and plecanatide. These agents stimulate secretory function of the intestine at various levels and improve stool consistency and stool volume, leading to increase bowel movements. Prucalopride is a highly affinity 5-HT4 receptor agonist with significant prokinetic properties. Studies in adults have shown beneficial effects of prucalopride in treating chronic constipation[86,87]. However, a large multicenter placebo-controlled randomized trial including 213 children (6-18 years) showed no significant difference in improvement in stool frequency and episodes of fecal incontinence between prucalopride and placebo[88]. Differences in mechanisms of constipation between children and adults, usage of different end points between studies (e.g., inclusion of fecal incontinence in the pediatric study), and inclusion of a large number of children with refractory constipation may have contributed to the lack of response of prucalopride in childhood constipation.

Lubiprostone is a CIC-2 chloride channel activator and cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Studies in adults have shown clinical efficacy of lubiprostone in adults with chronic constipation, as well as IBS-C[89-91]. A large double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study including more than 600 children with FC fulfilling the Rome IV criteria showed that 12 wk of lubiprostone treatment did not result in a statistically significant improvement in bowel movement frequency (to more than three times per week) in children with FC compared to placebo[92]. The reasons for not observing the desirable outcome of the trial may be similar to the prucalopride trial.

Linaclotide and plecanatide are guanylate cyclase C receptor agonists that promote secretion of fluid into the intestine. Although studies in adults show the efficacy of these two drugs in relieving constipation, no pediatric trials have been conducted. A retrospective chart review of 60 children with FC on linaclotide revealed that 45% had a positive response at 2.5 mo after starting the drug. However, about 1/3 of children on linaclotide had adverse events such as diarrhea, abdominal pain nausea, and bloating severe enough to stop treatment[93]. It is imperative to understand why these novel therapies are not working in children and find a way forward. Although the drugs make stools less hard and improve colonic motility by stimulating smooth muscles, none of these drugs address the main pathophysiological mechanisms of FC specially in younger children, i.e. stool withholding.

TRANSANAL IRRIGATION

Transanal irrigation systems irrigate the rectum and colon to clear accumulated feces. It is useful in children with constipation with severe recurrent fecal impaction resistant to conventional medical management. Three retrospective studies including children with constipation and FI (both organic and functional) have demonstrated improvement of FI when using transanal irrigation[94,95].

Surgical interventions

Surgical interventions are generally reserved for children whose symptoms are refractory to medical interventions. Around 10% of constipated children referred to a pediatric surgeon require some form of surgical intervention[96]. All these children need colonic and anorectal manometry and contrast enema of the lower bowel to delineate the physiological function and the anatomy before embarking into invasive surgical procedures.

ANTEGRADE CONTINENT ENEMA

In antegrade continent enema (ACE), a stoma is usually created to flush the colon from proximal to the distal direction using several surgical techniques. The initial procedure described was the Malone appendicocecostomy, where the appendix is brought out through the umbilicus, creating a conduit with a valve through which a catheter can be passed to irrigate the colon[97], or cecostomy, where a catheter is kept permanently. Novel techniques, such as creating a neoappendix using a colonic flap, laparoscopic-assisted cecostomy tube insertion, and inserting a percutaneous cecostomy button following interventional radiological procedures, have also been invented to establish the flushing mechanism[98]. A systematic review showed that both procedures (appendicostomy and cecostomy) are equally effective achieving continence (80% vs 70%, respectively)[99].

SURGICAL RESECTION AND STOMAS

Several surgical resection techniques have been described in the management of intractable constipation. They include segmental resection, including proctocolectomy with reservoir and ileoanal anastomosis, laparoscopic or open sigmoidectomy with or without ACE, laparoscopic low anterior resection, ileostomy, and colostomy[100]. However, there is no consensus on the definition of intractable constipation, and the type of surgical pathway that should follow. The decision that has to be taken after careful discussion between a motility specialist and pediatric surgeon. The physiological function of the colon needs to be carefully studied using contrast studies, transit studies, defecography and, when available, colonic manometry. However, complications, such as fecal incontinence, persistence of constipation following surgery, leaking from stomas, stoma prolapse, and small bowel obstructions, are known complications of these surgical interventions.

BOTULINUM TOXIN INJECTION

Botulinum toxin A is a neurotoxin, and acts as a muscle relaxant. When injected into intersphincteric area, botulinum toxin relaxes the internal anal sphincter and facilitates the passage of stools. The intervention is reported to be successful in the majority of children with constipation and only a few who received the first dose needed a second injection[58]. Minor complications such as pain, transient urinary and fecal incontinence are known to occur in some children. Large prospective placebo-controlled trials with a long follow-up are needed to evaluate the true effectiveness of this invasive and costly treatment.

NEUROMODULATION

Neuromodulation is an evolving therapeutic modality where a selective group of nerve fibers is electrically stimulated to alter the physiological function of a desired organ through neural activity. This can be achieved using transcutaneous stimulation of the posterior tibial nerve, transabdominal stimulation, and an electrode insertion surgically into the sacral foramen. Sacral neuromodulation improves colonic motility by increasing both antegrade and retrograde propagatory contractions[101,102]. Neuromodulation has been shown to be clinically effective (improving number of bowel motions and reducing frequency of fecal incontinence) in treating children with intractable constipation and slow transit constipation[103,104]. In addition, several systematic reviews have also shown the benefits of neuromodulation in children with constipation[105,106]. However, most of these studies are underpowered with a small number of patients, some were retrospective studies, and the majority had number of biases. In addition, there is no consensus on the frequency of stimulation or the duration of therapy. Therefore, it is difficult to draw firm conclusions in using neuromodulation as a treatment for chronic constipation in children.

Preventive measures

It is important to consider possible preventive measures that could be implemented for reducing incidence of FC in children. It is well known that stress, in any form, predisposes children to develop constipation. These events include minor home and school related events, child maltreatment, and exposure to civil unrest[107]. It is imperative to understand that most of these events are beyond the control of children. Teaching coping strategies with stress should be a part of modern school curricula, and through early psychological interventions, it may be possible to prevent constipation that is associated with psychological stress. In addition, identifying and addressing other psychological factors, such as anxiety, depression, internalization, and externalization, which are common in children with FC, need to be recognized and addressed early as primary or secondary preventive strategies[20,22,25,108]. Indrio and co-workers[109] provided evidence that prophylactic use of probiotics also would be able to prevent developing FC in young children with significant reduction in healthcare cost. The mechanisms of how probiotics play a role in prevention of FC is not entirely evident. However, it could possibly be through improvement of intestinal permeability, reduction of visceral sensitivity, changing mast cell density, and altering the cross talk between the brain and the gut through the brain-gut-microbiota axis. More research into this unexplored area with more convincing evidence would provide a potential window of opportunity to prevent constipation in the future. Improper or inadequate toilet training is a common risk factor for children to develop FC. Raising public awareness regarding the importance of timely toilet training would also help to reduce the prevalence of constipation. Additionally, educating parents and children about the importance of eating a balanced diet with the recommended amount of fiber and avoiding "junk food" is a critical step. Several studies have shown the association between sedentary lifestyle and constipation in children[30,34]. Therefore, encouraging physical activity in children would help in reducing the prevalence of FC. It is critical to recognize that, in today's competitive society, parents are compelled to work longer hours and spend less time with their children. Attention, attachment, appropriate parenting styles, and assisting children in developing desirable core lifestyles by setting a healthy example with proper dietary and physical activity patterns are also helpful in reducing the prevalence of FC.

Way forward into the future

It is evident that FC is a global public health problem with a significant physical, psychological, economic, and societal burden. Furthermore, at individual levels, chronic FC leads to physical and psychological consequences. The HRQoL of children is significantly affected due to both intestinal and extraintestinal symptoms of FC. Therefore, clinicians, and public health experts need to understand the gravity of the problem. Early aggressive, and effective medical therapy and other individualized non-pharmacological treatments need to be commenced as early as possible to prevent progressive bowel dysfunction and psychological consequences. Several therapeutic interventions may be used at the beginning of treatment, with gradual reduction of interventions as the child respond to treatment. Most of the novel investigations are only needed in children who do not respond to initial treatment. High resolution colonic and anorectal manometry are important investigations and will further improve the understanding of pathophysiology of chronic FC in children. In combination with a detailed clinical history and thorough physical examination, these novel investigation modalities reveals most of the pathophysiological processes that a clinician needs in decision making. The key drug in the medical management of FC in children will be PEG during for the foreseeable future. The other novel drugs will only be adjunct therapies. Researchers need to identify this reality, and novel drugs need to be tested in combination with PEG in randomized trials to improve the therapeutic armory. Surgical interventions are only needed in a minority of patients who are having severe and refractory constipation. Most of the described surgical interventions are studied in a non-randomized manner for several reasons. We believe more evidence is needed in major surgical procedures in the future to optimize the management of FC. Clinical validity of novel treatment options, such as pelvic floor physiotherapy and botulinum toxin injection to the anal sphincter, need to be explored in well-designed randomized trails, as these treatments can be made available to many centers with collaborative training. Preventive measures should be explored widely across the world to minimize societal and economic burden of FC in children.

CONCLUSION

Childhood FC is a common health problem across the globe. The high prevalence is partly due to a multitude of risk factors which are highly prevalent among children. The aetiology of FC in children is not clearly understood. Stool withholding play a major role in developing FC in younger children while anorectal dysfunction, and colonic dysmotility significantly contribute to the development of FC in older children. FC is a clinical diagnosis established using the standard Rome IV criteria after a thorough clinical evaluation using clinical history and physical examination. Although commonly used most of the routine investigations are not helpful in diagnosing or day to day management. Anorectal, and colonic manometry are useful only in children who are refractory to conventional management strategies. The majority of children have fecal impaction when they present to a clinician. The first step in the management is to evacuate the rectal fecal mass either with oral PEG or enemas. The maintenance therapy using either osmotic laxatives alone or osmotic laxatives combined with stimulant laxatives aimed to prevent reaccumulation of fecal matter in the colon and the rectum. Although it may subject to variations, most children recover within 3-6 mo of therapy. Novel pharmacological interventions such as prucalopride, lubiprostone, and linaclotide need further clinical trials to prove their efficacy in children. The surgical options such as antegrade continent enema, creation of stomas, and bowel resection are only rarely needed in children and only reserved for refractory FC. It is imperative to understand that FC contributes to a significant healthcare expenditure, and reduction of HRQoL. Therefore, researchers should focus on developing preventive strategies to alleviate both the societal and healthcare burden of FC in children.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: November 6, 2021

First decision: December 12, 2021

Article in press: July 6, 2022

Specialty type: Pediatrics

Country/Territory of origin: Sri Lanka

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Khayyat YM, Saudi Arabia; Shahini E, Italy; Tong WD, China S-Editor: Xing YX L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Xing YX

Contributor Information

Shaman Rajindrajith, Department of Paediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, University of Colombo, Colombo 00800, Sri Lanka; University Paediatric Unit, Lady Ridgeway Hospital for Children, Colombo 00800, Sri Lanka. shamanrajindrajith4@gmail.com.

Niranga Manjuri Devanarayana, Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya, Ragama 11010, Sri Lanka.

Marc A Benninga, Department of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Emma Children Hospital, Amsterdam University Medical Center, Amsterdam 1105AZ, The Netherlands.

References

- 1.Koppen IJN, Vriesman MH, Saps M, Rajindrajith S, Shi X, van Etten-Jamaludin FS, Di Lorenzo C, Benninga MA, Tabbers MM. Prevalence of Functional Defecation Disorders in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pediatr. 2018;198:121–130.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vriesman MH, Rajindrajith S, Koppen IJN, van Etten-Jamaludin FS, van Dijk M, Devanarayana NM, Tabbers MM, Benninga MA. Quality of Life in Children with Functional Constipation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pediatr. 2019;214:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ansari H, Ansari Z, Lim T, Hutson JM, Southwell BR. Factors relating to hospitalisation and economic burden of paediatric constipation in the state of Victoria, Australia, 2002-2009. J Paediatr Child Health. 2014;50:993–999. doi: 10.1111/jpc.12675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rasquin A, Di Lorenzo C, Forbes D, Guiraldes E, Hyams JS, Staiano A, Walker LS. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: child/adolescent. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1527–1537. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chogle A, Dhroove G, Sztainberg M, Di Lorenzo C, Saps M. How reliable are the Rome III criteria for the assessment of functional gastrointestinal disorders in children? Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2697–2701. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hyams JS, Di Lorenzo C, Saps M, Shulman RJ, Staiano A, van Tilburg M. Functional Disorders: Children and Adolescents. Gastroenterology. 2016 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russo M, Strisciuglio C, Scarpato E, Bruzzese D, Casertano M, Staiano A. Functional Chronic Constipation: Rome III Criteria Versus Rome IV Criteria. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;25:123–128. doi: 10.5056/jnm18035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mugie SM, Benninga MA, Di Lorenzo C. Epidemiology of constipation in children and adults: a systematic review. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25:3–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park M, Bang YG, Cho KY. Risk Factors for Functional Constipation in Young Children Attending Daycare Centers. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31:1262–1265. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.8.1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inan M, Aydiner CY, Tokuc B, Aksu B, Ayvaz S, Ayhan S, Ceylan T, Basaran UN. Factors associated with childhood constipation. J Paediatr Child Health. 2007;43:700–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Udoh EE, Rajindrajith S, Devanarayana NM, Benninga MA. Prevalence and risk factors for functional constipation in adolescent Nigerians. Arch Dis Child. 2017;102:841–844. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-311908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang Y, Tan SY, Parikh P, Buthmanaban V, Rajindrajith S, Benninga MA. Prevalence of functional gastrointestinal disorders in infants and young children in China. BMC Pediatr. 2021;21:131. doi: 10.1186/s12887-021-02610-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chew KS, Em JM, Koay ZL, Jalaludin MY, Ng RT, Lum LCS, Lee WS. Low prevalence of infantile functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) in a multi-ethnic Asian population. Pediatr Neonatol. 2021;62:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2020.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferreira-Maia AP, Matijasevich A, Wang YP. Epidemiology of functional gastrointestinal disorders in infants and toddlers: A systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:6547–6558. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i28.6547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devanarayana NM, Rajindrajith S. Association between constipation and stressful life events in a cohort of Sri Lankan children and adolescents. J Trop Pediatr. 2010;56:144–148. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmp077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sujatha B, Velayutham DR, Deivamani N, Bavanandam S. Normal Bowel Pattern in Children and Dietary and Other Precipitating Factors in Functional Constipation. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:SC12–SC15. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/13290.6025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oswari H, Alatas FS, Hegar B, Cheng W, Pramadyani A, Benninga MA, Rajindrajith S. Epidemiology of Paediatric constipation in Indonesia and its association with exposure to stressful life events. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18:146. doi: 10.1186/s12876-018-0873-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rajindrajith S, Devanarayana NM, Lakmini C, Subasinghe V, de Silva DG, Benninga MA. Association between child maltreatment and constipation: a school-based survey using Rome III criteria. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58:486–490. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cecil CAM, Zhang Y, Nolte T. Childhood maltreatment and DNA methylation: A systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;112:392–409. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rajindrajith S, Ranathunga N, Jayawickrama N, van Dijk M, Benninga MA, Devanarayana NM. Behavioral and emotional problems in adolescents with constipation and their association with quality of life. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0239092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kilincaslan H, Abali O, Demirkaya SK, Bilici M. Clinical, psychological and maternal characteristics in early functional constipation. Pediatr Int. 2014;56:588–593. doi: 10.1111/ped.12282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ranasinghe N, Devanarayana NM, Benninga MA, van Dijk M, Rajindrajith S. Psychological maladjustment and quality of life in adolescents with constipation. Arch Dis Child. 2017;102:268–273. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-310694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Dijk M, Benninga MA, Grootenhuis MA, Last BF. Prevalence and associated clinical characteristics of behavior problems in constipated children. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e309–e317. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waters AM, Schilpzand E, Bell C, Walker LS, Baber K. Functional gastrointestinal symptoms in children with anxiety disorders. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2013;41:151–163. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9657-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Çağan Appak Y, Yalın Sapmaz Ş, Doğan G, Herdem A, Özyurt BC, Kasırga E. Clinical findings, child and mother psychosocial status in functional constipation. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2017;28:465–470. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2017.17216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Dijk M, de Vries GJ, Last BF, Benninga MA, Grootenhuis MA. Parental child-rearing attitudes are associated with functional constipation in childhood. Arch Dis Child. 2015;100:329–333. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2014-305941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pediatrics AAo. Guide to toilet training. New York: Penguin Random House, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duong TH, Jansson UB, Holmdahl G, Sillén U, Hellström AL. Urinary bladder control during the first 3 years of life in healthy children in Vietnam--a comparison study with Swedish children. J Pediatr Urol. 2013;9:700–706. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2013.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asakura K, Todoriki H, Sasaki S. Relationship between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake among primary school children in Japan: Combined effect of children's and their guardians' knowledge. J Epidemiol. 2017;27:483–491. doi: 10.1016/j.je.2016.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olaru C, Diaconescu S, Trandafir L, Gimiga N, Stefanescu G, Ciubotariu G, Burlea M. Some Risk Factors of Chronic Functional Constipation Identified in a Pediatric Population Sample from Romania. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:3989721. doi: 10.1155/2016/3989721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daher S, Tahan S, Solé D, Naspitz CK, Da Silva Patrício FR, Neto UF, De Morais MB. Cow's milk protein intolerance and chronic constipation in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2001;12:339–342. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3038.2001.0o057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borrelli O, Barbara G, Di Nardo G, Cremon C, Lucarelli S, Frediani T, Paganelli M, De Giorgio R, Stanghellini V, Cucchiara S. Neuroimmune interaction and anorectal motility in children with food allergy-related chronic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:454–463. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.El-Hodhod MA, Younis NT, Zaitoun YA, Daoud SD. Cow's milk allergy related pediatric constipation: appropriate time of milk tolerance. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21:e407–e412. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2009.00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chien LY, Liou YM, Chang P. Low defaecation frequency in Taiwanese adolescents: association with dietary intake, physical activity and sedentary behaviour. J Paediatr Child Health. 2011;47:381–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Asakura K, Masayasu S, Sasaki S. Dietary intake, physical activity, and time management are associated with constipation in preschool children in Japan. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2017;26:118–129. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.112015.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seidenfaden S, Ormarsson OT, Lund SH, Bjornsson ES. Physical activity may decrease the likelihood of children developing constipation. Acta Paediatr. 2018;107:151–155. doi: 10.1111/apa.14067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao Y, Yu YB. Intestinal microbiota and chronic constipation. Springerplus. 2016;5:1130. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2821-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Meij TG, de Groot EF, Eck A, Budding AE, Kneepkens CM, Benninga MA, van Bodegraven AA, Savelkoul PH. Characterization of Microbiota in Children with Chronic Functional Constipation. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0164731. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zoppi GC, M . ; Luciano, A. ; Benini, A. ; Muner, A. ; Bertazzoni M.E. The intestinal echosystem in chronic constipation. Acta Paediatr 1998; 87(8): 836-841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khalif IL, Quigley EM, Konovitch EA, Maximova ID. Alterations in the colonic flora and intestinal permeability and evidence of immune activation in chronic constipation. Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37:838–849. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baaleman DFR, Rajindrajith S, Devanarayana NM, Di Lorenzo C, Benninga MA. Defecation Disorders in Children: Constipation and Fecal Incontinence. In: Guandalini SD A, editor Textbook of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition A Comprehensive Guide to Practice. Second Edition ed. New York: Springer International Pulishing AG Switzerland, 2021: 247-260. [Google Scholar]

- 42.van den Berg MM, Bongers ME, Voskuijl WP, Benninga MA. No role for increased rectal compliance in pediatric functional constipation. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1963–1969. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van den Berg MM, Voskuijl WP, Boeckxstaens GE, Benninga MA. Rectal compliance and rectal sensation in constipated adolescents, recovered adolescents and healthy volunteers. Gut. 2008;57:599–603. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.125690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van der Plas RN, Benninga MA, Büller HA, Bossuyt PM, Akkermans LM, Redekop WK, Taminiau JA. Biofeedback training in treatment of childhood constipation: a randomised controlled study. Lancet. 1996;348:776–780. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)03206-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Doodnath R, Puri P. Internal anal sphincter achalasia. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2009;18:246–248. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hutson JM, Chase JW, Clarke MC, King SK, Sutcliffe J, Gibb S, Catto-Smith AG, Robertson VJ, Southwell BR. Slow-transit constipation in children: our experience. Pediatr Surg Int. 2009;25:403–406. doi: 10.1007/s00383-009-2363-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Giorgio V, Borrelli O, Smith VV, Rampling D, Köglmeier J, Shah N, Thapar N, Curry J, Lindley KJ. High-resolution colonic manometry accurately predicts colonic neuromuscular pathological phenotype in pediatric slow transit constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25:70–8.e8. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dickson EJ, Hennig GW, Heredia DJ, Lee HT, Bayguinov PO, Spencer NJ, Smith TK. Polarized intrinsic neural reflexes in response to colonic elongation. J Physiol. 2008;586:4225–4240. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.155630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Corban C, Sommers T, Sengupta N, Jones M, Cheng V, Friedlander E, Bollom A, Lembo A. Fecal Impaction in the Emergency Department: An Analysis of Frequency and Associated Charges in 2011. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:572–577. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chitkara DK, Talley NJ, Weaver AL, Katusic SK, De Schepper H, Rucker MJ, Locke GR 3rd. Incidence of presentation of common functional gastrointestinal disorders in children from birth to 5 years: a cohort study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liem O, Harman J, Benninga M, Kelleher K, Mousa H, Di Lorenzo C. Health utilization and cost impact of childhood constipation in the United States. J Pediatr. 2009;154:258–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Youssef NN, Langseder AL, Verga BJ, Mones RL, Rosh JR. Chronic childhood constipation is associated with impaired quality of life: a case-controlled study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41:56–60. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000167500.34236.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang C, Shang L, Zhang Y, Tian J, Wang B, Yang X, Sun L, Du C, Jiang X, Xu Y. Impact of Functional Constipation on Health-Related Quality of Life in Preschool Children and Their Families in Xi'an, China. PLoS ONE 2013; 8(10) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gulati R, Komuravelly A, Leb S, Mhanna MJ, Ghori A, Leon J, Needlman R. Usefulness of Assessment of Stool Form by the Modified Bristol Stool Form Scale in Primary Care Pediatrics. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2018;21:93–100. doi: 10.5223/pghn.2018.21.2.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tabbers MM, DiLorenzo C, Berger MY, Faure C, Langendam MW, Nurko S, Staiano A, Vandenplas Y, Benninga MA European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition; North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology. Evaluation and treatment of functional constipation in infants and children: evidence-based recommendations from ESPGHAN and NASPGHAN. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58:258–274. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Benninga MA, Tabbers MM, van Rijn RR. How to use a plain abdominal radiograph in children with functional defecation disorders. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2016;101:187–193. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Southwell BR, Clarke MC, Sutcliffe J, Hutson JM. Colonic transit studies: normal values for adults and children with comparison of radiological and scintigraphic methods. Pediatr Surg Int. 2009;25:559–572. doi: 10.1007/s00383-009-2387-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lu PL, Mousa HM. Constipation: Beyond the Old Paradigms. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2018;47:845–862. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fritz T, Hünseler C, Broekaert I. Assessment of whole gut motility in adolescents using the wireless motility capsule test. Eur J Pediatr. 2022;181:1197–1204. doi: 10.1007/s00431-021-04295-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rodriguez L, Heinz N, Colliard K, Amicangelo M, Nurko S. Diagnostic and clinical utility of the wireless motility capsule in children: A study in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33:e14032. doi: 10.1111/nmo.14032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Excellence NIfHaC. Constipation in chldren and young people: diagnosis and management. 26th May 2010 ed. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gylaecologists, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bijoś A, Czerwionka-Szaflarska M, Mazur A, Romañczuk W. The usefulness of ultrasound examination of the bowel as a method of assessment of functional chronic constipation in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37:1247–1252. doi: 10.1007/s00247-007-0659-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bekkali NL, van den Berg MM, Dijkgraaf MG, van Wijk MP, Bongers ME, Liem O, Benninga MA. Rectal fecal impaction treatment in childhood constipation: enemas versus high doses oral PEG. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e1108–e1115. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Loening-Baucke V. Constipation in early childhood: patient characteristics, treatment, and longterm follow up. Gut. 1993;34:1400–1404. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.10.1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Taubman B, Blum NJ, Nemeth N. Stool toileting refusal: a prospective intervention targeting parental behavior. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:1193–1196. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.12.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van Dijk M, Benninga MA, Grootenhuis MA, Nieuwenhuizen AM, Last BF. Chronic childhood constipation: a review of the literature and the introduction of a protocolized behavioral intervention program. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67:63–77. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Keefer L. Behavioural medicine and gastrointestinal disorders: the promise of positive psychology. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15:378–386. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Williams CL, Bollella M, Wynder EL. A new recommendation for dietary fiber in childhood. Pediatrics. 1995;96:985–988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Axelrod CH, Saps M. The Role of Fiber in the Treatment of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Children. Nutrients. 2018;10 doi: 10.3390/nu10111650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wojtyniak K, Szajewska H. Systematic review: probiotics for functional constipation in children. Eur J Pediatr. 2017;176:1155–1162. doi: 10.1007/s00431-017-2972-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wegner A, Banaszkiewicz A, Kierkus J, Landowski P, Korlatowicz-Bilar A, Wiecek S, Kwiecien J, Gawronska A, Dembinski L, Czaja-Bulsa G, Socha P. The effectiveness of Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 as an adjunct to macrogol in the treatment of functional constipation in children. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2018;42:494–500. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2018.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dehghani SM, Ahmadpour B, Haghighat M, Kashef S, Imanieh MH, Soleimani M. The Role of Cow's Milk Allergy in Pediatric Chronic Constipation: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Iran J Pediatr. 2012;22:468–474. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Iacono G, Cavataio F, Montalto G, Florena A, Tumminello M, Soresi M, Notarbartolo A, Carroccio A. Intolerance of cow's milk and chronic constipation in children. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1100–1104. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810153391602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mohammadi Bourkheili A, Mehrabani S, Esmaeili Dooki M, Haji Ahmadi M, Moslemi L. Effect of Cow's-milk-free diet on chronic constipation in children; A randomized clinical trial. Caspian J Intern Med. 2021;12:91–96. doi: 10.22088/cjim.12.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Young RJ, Beerman LE, Vanderhoof JA. Increasing oral fluids in chronic constipation in children. Gastroenterol Nurs. 1998;21:156–161. doi: 10.1097/00001610-199807000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mozaffarpur SA, Naseri M, Esmaeilidooki MR, Kamalinejad M, Bijani A. The effect of cassia fistula emulsion on pediatric functional constipation in comparison with mineral oil: a randomized, clinical trial. Daru. 2012;20:83. doi: 10.1186/2008-2231-20-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nimrouzi M, Sadeghpour O, Imanieh MH, Shams Ardekani M, Salehi A, Minaei MB, Zarshenas MM. Flixweed vs. Polyethylene Glycol in the Treatment of Childhood Functional Constipation: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Iran J Pediatr. 2015;25:e425. doi: 10.5812/ijp.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brazzelli M, Griffiths PV, Cody JD, Tappin D. Behavioural and cognitive interventions with or without other treatments for the management of faecal incontinence in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD002240. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002240.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.van Engelenburg-van Lonkhuyzen ML, Bols EM, Benninga MA, Verwijs WA, de Bie RA. Effectiveness of Pelvic Physiotherapy in Children With Functional Constipation Compared With Standard Medical Care. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:82–91. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gordon M, MacDonald JK, Parker CE, Akobeng AK, Thomas AG. Osmotic and stimulant laxatives for the management of childhood constipation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016:CD009118. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009118.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen SL, Cai SR, Deng L, Zhang XH, Luo TD, Peng JJ, Xu JB, Li WF, Chen CQ, Ma JP, He YL. Efficacy and complications of polyethylene glycols for treatment of constipation in children: a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014;93:e65. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Farahmand F. A randomised trial of liquid paraffin versus lactulose in the treatment of chronic functional constipation in children. Acta Medica Iranica. 2007;45:183–188. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Urganci N, Akyildiz B, Polat TB. A comparative study: the efficacy of liquid paraffin and lactulose in management of chronic functional constipation. Pediatr Int. 2005;47:15–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.2004.02001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Üstündağ G, Kuloğlu Z, Kirbaş N, Kansu A. Can partially hydrolyzed guar gum be an alternative to lactulose in treatment of childhood constipation? Turk J Gastroenterol. 2010;21:360–364. doi: 10.4318/tjg.2010.0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vilanova-Sanchez A, Gasior AC, Toocheck N, Weaver L, Wood RJ, Reck CA, Wagner A, Hoover E, Gagnon R, Jaggers J, Maloof T, Nash O, Williams C, Levitt MA. Are Senna based laxatives safe when used as long term treatment for constipation in children? J Pediatr Surg. 2018;53:722–727. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Camilleri M, Kerstens R, Rykx A, Vandeplassche L. A placebo-controlled trial of prucalopride for severe chronic constipation. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2344–2354. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Quigley EM, Vandeplassche L, Kerstens R, Ausma J. Clinical trial: the efficacy, impact on quality of life, and safety and tolerability of prucalopride in severe chronic constipation--a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:315–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]