Abstract

Naturally occurring retirement communities (NORCs) are unplanned communities with a high proportion of residents aged 65 years and older. Oasis is a Canadian aging in place model that combines health and supportive community services for adults aged 65 years and older within NORCs. The aims of this study were to explore how physical distancing restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic impacted older adults living in a NORC (Oasis members) and to investigate whether Oasis served as a context for social connection and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. An interpretive description methodology guided this study. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with nine Oasis members (aged 66–77 years) and two Oasis site coordinators. The Oasis members also completed a social network mapping activity guided by the hierarchical mapping technique. Three overarching themes related to the impact of physical distancing on Oasis members during the COVID-19 pandemic were identified: (1) unintended consequences of physical distancing restrictions on participants’ wellbeing; (2) face-to-face interactions are important for social connection; and (3) family, friend, healthcare provider, and community support mitigated the impact of physical distancing restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, two of Oasis’ core pillars were found to support participants: strengthening social connectivity and connection to pre-existing community services. Findings illustrate that community programs like Oasis acted as a source of resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic and advance our understanding of the impact of aging in place models on community dwelling older adults’ experience of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Aging in place, Community support, Naturally occurring retirement communities, Seniors

Introduction

Approximately 93% of Canadian older adults live in community settings (non-institutional, congregate living) (Statistics Canada, 2016c), and many of them want to remain living in the community and independently as long as possible (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, 2011). Aging in place describes a person’s ability to remain living in their community safely and with minimal support as they age (Davey et al., 2004). Older adults describe aging in place as having choices about their living arrangements, feeling safe and secure in their home, having access to community services, maintaining their social relationships, and having autonomy and independence (Wiles et al., 2012). When proper supports are available, aging in place can help maintain quality of life, preserve autonomy, and help avoid the costly option of institutional care (Marek et al., 2012). For example, the provision of social support and opportunity for social engagement has been found to maintain the physical and mental well-being of older adults and to delay institutionalization (Nicholson, 2012). Similarly, being socially isolated has been identified to be as strong a predictor of morbidity and mortality as obesity and smoking (Cacioppo et al., 2011; Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010, 2015), suggesting that it is important to encourage and support opportunities for social engagement throughout the lifespan.

The COVID-19 Pandemic and Social Connection

To control the spread of the Coronavirus 2019 disease (COVID-19), in the spring of 2020, provincial governments across Canada implemented physical distancing restrictions (Government of Canada, 2020). In the province of Ontario, physical distancing restrictions included closure of public services and non-essential businesses (for example, restaurants, recreational facilities and religious spaces), and encouragement by public health officials for individuals aged 70 and over or with underlying health conditions to self-isolate (The Government of Ontario, 2020). Although quarantines and source isolation (isolating the person with the infections disease to prevent cross-infection) have been done in the past to control the spread of other diseases (e.g., severe acute respiratory syndrome (Hawryluck et al., 2004) and Ebola (Desclaux et al., 2017)), this was the first time in history that communities implemented restrictions on all community members, whether they were infected with the virus or not. As such, the psychological impact of physical distancing at this scale is still unknown.

The COVID-19 Social Connectivity Paradox (Smith et al., 2020) suggests that following physical distancing recommendations simultaneously protected and harmed older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic (Smith et al., 2020). In a longitudinal study conducted in the Netherlands (Van Tilburg et al., 2020), older adults completed online questionnaires related to social and emotional loneliness in the fall of 2019, and again in the Spring of 2020, when physical distancing measures were still in place. Participants were found to be more socially and emotionally lonely during the pandemic (Van Tilburg et al., 2020). Similarly, in the United States, adults 18 and older completed questionnaires on loneliness in February, March and April of 2020 (Luchetti et al., 2020). Among adults 65 years or older, there was a slight increase in loneliness between February and March, and it was stable thereafter (Luchetti et al., 2020). Despite the increase in loneliness at the beginning of the pandemic, emerging data suggests that older adults were able to adapt to the changes resulting in a stability or improvement in loneliness over time (Kotwal et al., 2021). Older adults who experienced loneliness that remained severe, or worsened, over time, have been found to have insufficient social support, limited access or comfort with technology and/or an inability to cope emotionally (Kotwal et al., 2021). These findings suggest that personal characteristics and social contexts have promoted resilience among older adults during the pandemic.

Oasis Senior Support Living Inc.: A Canadian Model for Aging in Place

Oasis Senior Supportive Living Inc. (Oasis) is a Canadian model for aging in place that combines health and supportive community services for adults 65 and older within naturally occurring retirement communities (NORCs). NORCs are unplanned communities with a high proportion of residents aged 65 and above (Hunt & Ross, 1990). By targeting NORCs using a community-level intervention, NORC-based programs aim to change the way in which services are provided in the community to older adults by identifying local care needs, maximizing local capacities and allocating resources within a community setting in order to create and investigate what constitutes a successful aging in place model (Hunt & Gunter-Hunt, 1986). Recreational and social opportunities that help prevent and address isolation are core components of NORC-based programs (Hunt & Ross, 1990). For reference, Oasis participants are referred to as “members”.

Oasis has three core pillars that support the well-being and quality of life of members: social connection, activity, and nutrition (Oasis Senior Support Living Inc, 2020). Oasis consists of five core components: 1) on-site program coordinator (paid position) and volunteers; 2) physical and social activation programming (delivered by a paid staff); 3) a congregate meal program; 4) a community volunteer board of directors; and 5) monthly membership meetings. Oasis connects members to existing community services that provide instrumental support (such as meal delivery) and promotes the building of social networks by providing members with an opportunity to attend daily activities (such as fitness classes) in which they have opportunities to socialize with and learn from other Oasis members. For more information about Oasis refer to www.oasis-aging-in-place.com.

Although an increase in socialization among NORC residents has been noted as a benefit of NORC-based programs, such as Oasis, (Hunt & Ross, 1990), participants have also identified that their neighbours cannot support all of their needs (Greenfield & Bowers, 2016). For example, in a qualitative study conducted in the United States, NORC residents identified that while their neighbours might be able to help them with some practical tasks such as giving them a ride to see their doctor, they are not well suited to help with other challenges such as their finances and personal care (Greenfield & Bowers, 2016). Therefore, to support aging in place, NORC-based programs also strive to enhance access to formal providers and community supports.

Oasis was successfully initiated in an apartment building in Kingston, ON in 2008, its expansion in sites in London, Hamilton, Belleville, Toronto, and Kingston ON are currently being evaluated.

Guiding Theoretical Constructs Conceptual Frameworks

The Oasis program itself and the convoy model (Antonucci et al., 2014; Fuller et al., 2020) provided a conceptual framework for this study.

It has been proposed that NORC-based programs enhance relationships among lead agency staff and NORC residents, partnerships among professionals, and older adults’ relationships with each other (Greenfield, 2014). Enhancing these relationships is thought to improve services and supports at the community level, ultimately contributing to aging in place (Greenfield, 2014). Guided by the Oasis program model itself, in this study we assumed that Oasis builds and enhances relationships between members and helps develop long-term relationships between Oasis site coordinators and members, ultimately supporting service use and strengthening informal support networks.

According to the convoy model (Antonucci et al., 2014), a person is surrounded by a social network composed of individuals that provide the person with different types of support e.g., social support, defined as the perception that one is cared for and has people that can help as needed (House, 1981), and instrumental support, which refers to the provision of tangible goods and services (House, 1981). The convoy model is typically measured using the hierarchical mapping technique (Ajrouch et al., 2001; Antonucci, 1986), which involves placing the person’s social network into three concentric circles representing three levels of closeness: close, closer, closest. Social networks vary in their structure, function and quality of relationships (Antonucci et al., 2014). The structure of convoys is influenced by situational (e.g., cultural values) and personal (e.g., gender and age) characteristics. For example, older women tend to have significantly larger networks than men (McLaughlin et al., 2010).

A supportive social network may mitigate the impact of physical distancing restrictions by proving the person with support, as needed. As suggested by the convoy model (Antonucci et al., 2014; Fuller et al., 2020), individuals are supported by a social network. Community programs like Oasis may have acted as a source of resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic, supporting older adults’ ability to adapt to the changes brought on by physical distancing restrictions.

Purpose of Study

Following the implementation of physical distancing regulations in March 2020, Oasis programming was suspended, including the monthly membership meetings. None of the programming or meetings were offered virtually. To continue supporting the members, in the summer of 2020, when we conducted the study, the site coordinators were engaging with members via intermittent telephone conversations (both individual and conference calls) and delivering monthly care packages. These were new services not previously offered by Oasis. Using the Oasis program model and the convoy model (Antonucci et al., 2014; Fuller et al., 2020) as guiding frameworks, in this study we investigated whether Oasis served as a context for social connection and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study was conducted to explore how physical distancing restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic impacted Oasis members and to investigate if and how the Oasis aging in place model provided older adults living in NORCs support when physical distancing restrictions were imposed.

In this study we addressed two research questions:

How did physical distancing impact Oasis members?

Did Oasis serve as a context for social connection and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic (from the perspective of Oasis site coordinators and the members themselves)?

Methods

Study Design

The study was guided by qualitative interpretive description methodology (Thorne, 2016; Thorne et al., 1997). Interpretive description is an inductive research methodology used in practice-oriented research to generate knowledge of complex phenomena (Thorne, 2016; Thorne et al., 1997). Interpretive description is positioned within a constructivist paradigm, in which it is suggested that there are multiple perspectives and multiple understandings of a phenomena (Charmaz, 2000).

In interpretive description, it is suggested that the researcher’s clinical background and theoretical knowledge shapes the analytic process (Thorne, 2016). Rehabilitation science is an interdisciplinary field that is focused on optimizing physical and psychosocial functioning and quality of life of persons with disabilities and ill-health (Ntusi, 2019). In this study, from a rehabilitation science perspective, we explored the perceived impact of the Oasis program on the physical distancing experiences of older adults living in a NORC in Hamilton, ON. The research team was composed of a health services researcher, and rehabilitation sciences researchers with backgrounds in occupational therapy, physiotherapy, and gerontology.

Participant Recruitment

This study is part of a larger participatory research project aimed at evaluating the original Oasis program and its expansion in sites across Ontario, Canada (Kingston, Belleville, Toronto, Hamilton and London). To be eligible to participate in this study, individuals had to be an Oasis site coordinator or an Oasis member in Hamilton’s site. Oasis members had to have previously consented to participating in Oasis-related research (n = 16). Eligible members and the two site coordinators were invited to participate in this study by a research assistant. All interested participants were then contacted by the first author (LGD) and were provided with a package containing study materials (information letter, consent form, semi-structured interview questions and materials for the social network mapping activity).

Ethical Approval

This study received approval by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (REB Project #5098). Oral informed consent was obtained by the interviewer from all participants prior to starting the phone interviews.

Setting

Hamilton’s Oasis site is located in a 216-unit apartment complex (3 buildings) in Hamilton, ON, a city of 747,545 people (Statistics Canada, 2016b). Just before COVID-19 physical distancing restrictions were imposed in March 2020, the site had 34 active members and offered an average of six activities per week (such as coffee hour, group walks, and karaoke). The average age of members at the Hamilton Oasis location is 74 years. The average age in the dissemination area (small geographic area with a population of 400 to 700 persons (Statistics Canada, 2018)) where Oasis is located is 41 years, with adults aged 65 years and older making up 16% of the population (Statistics Canada, 2016a).

Data Generation

The data consisted of semi-structured one-on-one interviews as well as social network mapping. Participants were provided with the interview questions as well as instructions for the social network mapping activity and an example of a completed social network map one week prior to the interview. Phone interviews took place in July and August of 2020, at a time during which social gatherings were limited to ten people, indoor recreational facilities remained closed, and restaurants were only allowed outdoor dinning. The interviews were conducted first and were immediately followed by the social network mapping activity (this activity was only completed by Oasis member participants, not the site coordinator participants). All interviews, including the social network mapping, were conducted by LGD and were audio-recorded.

Interview Guide

A semi-structured interview guide was developed to address the research questions. Open-ended questions were formulated for each type of participant (nine and seven questions for Oasis members and site coordinators, respectively). Interview questions were focused on the impact that physical distancing had on members’ routines as well as whether and how Oasis were supporting members while physical distancing restrictions were in place. A member and a site coordinator from a different Oasis site (Kingston, ON) provided feedback about the clarity of the interview questions. The interview guide was refined accordingly. Questions for Oasis members included “Could you please describe what has been the hardest thing for you about the physical distancing experience?” and “How do you feel Oasis has influenced your experience with physical distancing?” Questions for site coordinators included “How do you feel having a program like Oasis in the building prior to the implementation of physical distancing regulations has influenced how members are managing the current situation?” and “From your conversation with members and your observations, could you please tell me how the suspension of Oasis has impacted members?”.

Social Network Maps

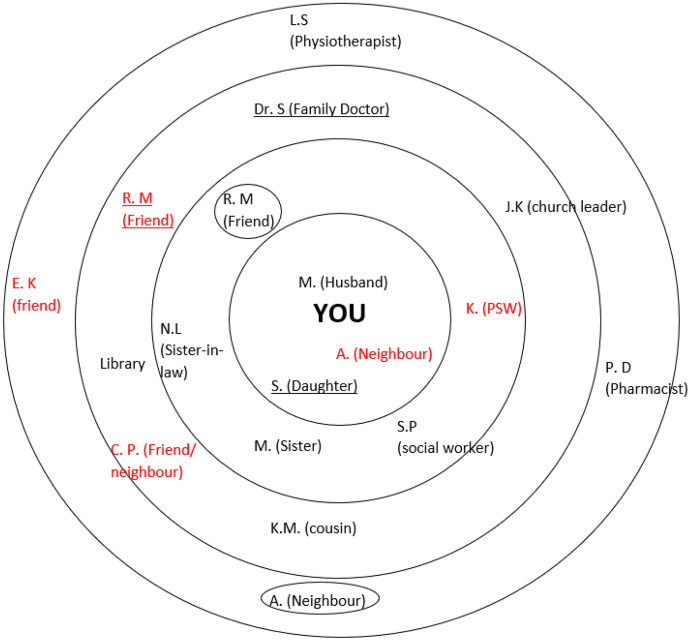

A pilot of the social network mapping activity was conducted with a member from a different Oasis site (Kingston, ON), and questions and instructions were refined for clarity. The social network mapping activity was guided by the convoy model (Antonucci et al., 2014) and the hierarchical mapping technique (HMP) (Ajrouch et al., 2001; Antonucci, 1986), which is designed to measure network structure and relationship closeness. The HMP uses three concentric circles to represent participants’ social networks.

Following the interview, LGD asked Oasis member participants to complete the social network mapping activity. In the package mailed to participants the week before the interview, participants were provided with detailed instructions for how to complete the social network map, an example of a completed map, and two pens (black and red-ink). Members were first asked to think about their social network before joining Oasis and to write on a blank piece of paper the names of those identified (individuals an/or organizations). Participants were then asked to identify the contacts that they feel are the closest to them and, using the black-ink pen, to write the initials of those contacts in the inner-most circle. Participants were then asked to place the remaining names on the two outer circles, based on how close they felt to those contacts. Following this, members were asked to think about their social network today (day of the interview) and to add any contacts not previously identified (with the red-ink pen).

Once they had completed the map, members were asked to describe their map to LGD, starting with the inner-most circle (i.e., person or organizations that the person identified as closest to them). While describing their map, LGD asked members whether and how each contact had supported them during physical distancing. LGD asked participants to underline the contacts that had provided them the most support. Participants were also asked to consider whether physical distancing restrictions had had an impact on the composition of their network (e.g., feeling like some of the contacts were no longer a part of their social network). For members that had included another Oasis member in their map, members were asked if they had met that person at Oasis, and if they knew them previously, whether their relationship had strengthened since joining Oasis. After the interview was completed, members were asked to mail their social network map to the research team using a prepaid envelope. Figure 1 provides an example of a completed social network map.

Fig. 1.

Social network mapping example. All the names in red ink represent new addition to participants’ social network after joining Oasis. The contacts that provided participants with the most support during physical distancing are underlined

Data Analysis

In line with an interpretive description approach (Thorne, 2016), data generation and analysis occurred concurrently. All interviews were transcribed verbatim by LGD, and all identifiable information was eliminated in the transcription process. The transcripts, audio files and social network maps were imported into Dedoose (SocioCultural Research Consultants LLC, 2019), a program designed to store and organize qualitative data.

The data were analyzed in three stages: preparation stage, organization stage, and interpretation stage (Thorne, 2016). LGD was involved in all three stages, LL in the organization and interpretation stages, and ED in the interpretation stage. In addition, a Qualitative Structural Analysis (QSA; Herz et al., 2015) was used to combine interview and social network map data. QSA is a three-step analysis process in which the interview transcripts and social network maps are initially analyzed separately and are then combined. The transcripts and social network maps were analyzed separately in the preparation and organization stages and then in combination in the interpretation stage. To support the exploration of relationships and explanations contained within the data, LGD wrote analytical memos (Birks et al., 2008) at each stage of data analysis.

In the preparation stage (Thorne, 2016), LGD read the interview transcripts twice prior to coding and the social network maps were visually examined by LGD to get a sense of map attributes. In the organization stage (Thorne, 2016), the interview transcripts were coded in two cycles. In the first cycle, large sections of transcripts were coded by LGD to preserve context and multiple codes were applied to each excerpt to capture the complexity of members’ experiences. Oasis members and site coordinators’ transcripts were analyzed separately. Interpretive categories were identified and defined using a constant comparison analysis technique (Thorne, 2016) in which data excerpts were compared with one another and with emerging interpretations to look for similarities and differences across and between participant experiences. The senior author (LL) reviewed the coding of two transcripts (one from a site coordinator, the other from an Oasis member) and changes were made to the codes and definitions of the codes based on her input. In the second cycle, similar codes were combined and grouped into interpretive categories. For example, the codes “giving support” and “receiving support” were grouped into the interpretive category “reciprocal familial support”. Still in the organization stage, the analysis of the network maps focused on the attributes of the maps such as number of contacts in members’ networks, type of contacts (i.e., friends, family, healthcare providers, and community support), distribution of contacts (location of contacts within the map), and information about contacts who were supportive to the participants while physical distancing restrictions were in place (location of contact within the map and relation to member). All coding was done in the Dedoose platform. Once codes were finalized, all codes and associated quotations were transferred to an excel spreadsheet for further refinement.

Lastly, in the interpretation stage (Thorne, 2016) the attributes of the social network maps were compared between participants. This information was used to further refine the interpretive categories identified in the previous stage in relation to the interview transcripts by providing a greater understanding of how members’ social networks supported them during physical distancing, and the perceived impact of Oasis on that experience. The first author, in consultation with LL and ED, further refined the interpretive categories and reorganized them into themes related to Oasis members and site coordinators’ perceptions of the impact of physical distancing on Oasis members. For example, the interpretive categories “mobility”, “health concerns” and “isolation/loneliness” were grouped together into the theme “Unintended consequences of physical distancing restrictions on members’ wellbeing”.

Quality Strategies

Data source-triangulation (Thorne, 2016) enhanced credibility of findings. Triangulation in this project consisted of the use of multiple data sources (Oasis members and site coordinators) and mediums (one-on-one interviews and social network mapping activity). To establish transparency and trustworthiness, an audit of the decision trail (Carcary, 2009) was developed using a qualitative log in which the analysis process was recorded by LGD. In addition, numbers were included in the presentation of findings to establish transparency about the extent to which an idea had been endorsed by participants in the study (Thorne et al., 2004). It is important to note that no inferences can be drawn about the prevalence of phenomena observed beyond the study’s sample. Procedural and analytical rigour were enhanced through the use of an explanatory effects matrix (Miles et al., 2013), which was used to display the findings while examining patterns within and between participants. Permeability refers to the researcher’s capacity of having their own assumptions, understanding and interpretations be influenced by the information gathered or observations made, so that data outcomes reflect participants’ views, and not the researcher’s pre-conceived ideas (Fossey et al., 2002; Stiles, 1999). To enhance permeability, before data generation and analysis, LGD made explicit her assumptions, beliefs, and expectations from this study by recording her preconceptions of the impact of a program like Oasis on members’ experience of physical distancing which were informed by previous research and immersion in current research.

Findings

Nine Oasis members (one male, eight females) and two site coordinators participated in this study. The members were between 66 and 77 years of age. Prior to the implementation of COVID-19 distancing requirements, five of the members attended activities at least once a week, the other four a few times per month. Three members lived alone, four with a spouse and two with a friend. Seven members reported family (besides their spouse) in Hamilton or within a one-hour drive, and two had family in Ontario (more than an hour’s drive away). Six members drove and had access to a car, three did not drive and relied on public transportation. All the members lived with at least one chronic condition.

Three overarching themes related to the impact of physical distancing on Oasis members during the COVID-19 pandemic were identified during the analysis: (1) unintended consequences of physical distancing restrictions on members’ wellbeing; (2) face-to-face interactions are important for social connection; and (3) family, friend, healthcare provider, and community support mitigated the impact of physical distancing restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Unintended Consequences of Physical Distancing Restrictions on Members’ Wellbeing

As a result of physical distancing restrictions, Oasis member participants had limited opportunities for physical activity and social interactions, which may have impacted their physical and mental health. Some of the participants reported that disregard of physical distancing recommendations by other community members was a reason why they avoided outings as they caused feelings of vulnerability, frustration, and distress. In addition, to reduce their risk of getting COVID-19, some of the participants let go of personal resources and habits that they reported were supportive of their wellbeing.

Based on the data about COVID-19 (Iaccarino et al., 2020; Palmieri et al., 2020; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2020) the study participants’ older age and their health status of living with pre-existing health conditions put them at a higher risk of experiencing more acute illness and related consequences if they were to get the COVID-19 virus. All the Oasis member participants were aware of their higher vulnerability to the virus in comparison to the general population. As one member who had recently been diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease described:

“If people have COVID-19 and they don’t know it, and I get it, well I am finished. I don’t think I can fight it. I don’t have full lung capacity and at my age and my husband's age, if I give it to him, he is gone.” (OM2).

OM2 is aware that her and her husband’s age and pre-existing health conditions increase their vulnerability to the virus; she therefore reported following public health recommendations rigorously.

Six of the Oasis member participants reported that awareness of greater vulnerability to COVID-19 prompted them to take added precautions. OM2’s earlier description of her vulnerability and fear of getting the virus resulted in her cancelling visits from the personal support worker (healthcare provider) who provided daily personal care to her husband:

“I cancelled the [personal support workers] once COVID-19 started. I was afraid of them bringing the virus [to our home]. They could have the virus and not know it and give it to us.” (OM2).

OM2 shared that it was difficult to care for her husband on her own, but that her family’s safety was more important. Similarly, talking generally about an Oasis member, one of the site coordinator participants said: “she [Oasis member] did not leave her apartment for three weeks. She would not even go to the laundry room.” (SC2). SC2 shared that pre-pandemic that Oasis member went on daily walks; staying indoors all day was not her usual behaviour. Lastly, one of the site coordinator participants shared that one Oasis member stopped working because she did not feel safe using public transportation:

“She [Oasis member] has a number of underlying health issues and did not want to take any risks by taking the bus, so she did not return to work. She has no support from family, so she is basically on her own.” (SC1).

As described by SC1, in not working or having family support, the Oasis member’s ability to support herself financially may have been impacted. These examples illustrate that Oasis members rigorously followed physical distancing recommendations; however, a repercussion of the added precautions is that Oasis member participants let go of resources (financial and personal) that they reported were supportive of their wellbeing.

Five of the participants reported that opportunities for physical activity were limited by the closure of public places (such as indoor walking spaces) and fear of being around others. For example, one member shared that she typically goes to the beach for walks in the summer, but because of how crowded it had been, she did not feel safe doing so this year: “It will be a while before I go down to the beach for a walk again, because the beach gets very crowded.” (OM1). Similarly, the four other participants who reported that they used to go on regular walks pre-pandemic, expressed that they had either stopped or reduced the frequency of their walks.

Five of the participants described outings (such as going to the grocery store) as being extremely difficult because seeing others not following physical distancing recommendations made them feel unsafe and frustrated. As described by one Oasis member participant:

“At the beginning most people would allow for physical distancing. Now [three months post implementation of restrictions] they are like, ‘oh we are fine, we can just walk near you, it doesn’t matter.’ So that is a concern because I do not want to get sick. I try to do what I can not to get sick.” (OM5).

Similarly, one of the site coordinators described an encounter she had with an Oasis member after a grocery store trip:

“[Physical distancing] has increased some of the members' frustration. I met [Oasis member] at the elevator, she was in tears and completely outraged. She had finally ventured out to the grocery store and people were not physical distancing, people were reaching in front of her, and by the time she got home she was in quite a state.” (SC2).

These two quotations illustrate that when community members do not follow physical distancing recommendations, they may unintentionally cause individuals who are worried about getting the virus to feel vulnerable, frustrated, and distressed.

Face-to-face Interactions are Important for Social Connection

Face-to-face interactions were identified by participants as being important for giving and receiving social and instrumental support. Even though all of the Oasis member participants reported that they stayed connected with their social network virtually and through phone calls, most of the participants reported feeling isolated as a result of lack of face-to-face interactions.

Seven of the members discussed not leaving their homes often pre-pandemic, suggesting that most participants were already relatively isolated before physical restrictions were implemented. For example, OM1 shared: “Now the only difference [in my routine] is that I have to get to the store at 7am to avoid the crowds, everything else is the same.” (OM1). This participant reported that prior to the pandemic, she only left her house to get groceries and to attend Oasis activities; physical distancing restrictions did not have a substantial impact on her routine. Similarly, for six of the participants, besides medical appointments, grocery shopping and visiting family, Oasis activities were the only activity that they reported attending. As OM6 shared, “What I miss the most about attending Oasis programing is just getting out of the apartment. Just having somewhere to go.” (OM6). Similarly, a participant site coordinator shared: “[Oasis member] said to me, ‘[Oasis] saved my life. We [he and his wife] were just so lonely, it gave them something to look forward to.’” (SC1). Although seven of the participants did not report substantial changes to their routine, as illustrated in SC1’s remarks, small changes to one’s routine can impact wellbeing.

All Oasis member participants mentioned missing the face-to-face interactions that they had throughout the week: “I miss it [Oasis in-person activities]. I miss the friendship and camaraderie.” (OM1). Even though OM1 stayed connected with another Oasis member, she shared that she missed seeing the other members and having somewhere to go during the day. Similarly, OM2 shared: “[Before COVID-19] I was going to the library [once a week] to get books and to talk to the librarians. I miss that” (OM2). OM2 identified that the social contact with librarians in addition to getting books as something important to her. The social interactions described by OM2 and OM1 occurred in public places that offer activities and/or services for the community (the library and Oasis), which illustrates that community activities are important for maintaining and building social connections.

Even though all the participants remained in contact with someone from their social network, virtually and through phone calls, face-to-face interactions were described as important for giving and receiving support. For example, OM7’s son had a car accident two years ago and pre-pandemic she visited him weekly to provide instrumental and emotional support. OM7 described that despite talking to her son daily, the hardest thing about the pandemic was not seeing him as this prevented her from providing the support that he needed: “My son lives by himself and he needs my support and company at least once a week. It hurts not being able to [support him].” (OM7). Similarly, for OM2 face-to-face interactions were necessary to remain connected with some of her friends: “I have not been able to stay in contact with them because one of them is deaf, and the other one has a disability [which prevents hers from virtual communication].” (OM2). OM2’s comment illustrates that connecting virtually or through phone calls may not be possible for everyone, thus not everyone is able to rely on technology for connection.

The site coordinators noticed that members seemed to be feeling lonely. One site coordinator participant described that because people seemed to be lonely, weekly check-in phone calls were taking much longer: “The phone calls [with Oasis members] can go on for half an hour. They [Oasis members] are lonely, so they are not quick phone calls.” (SC1). As members did not have their usual opportunities for socialization (such as at the public library or pool), the phone calls provided an opportunity for social connection. Six of the Oasis member participants reported feeling isolated as a result of physical distancing restrictions: “I am at the stage where I can’t really leave my husband unless I get somebody to help. So even before COVID-19, I was getting isolated.” (OM2). OM2 reported her previous feelings of isolation were exacerbated while physical distancing restrictions were in place. Similarly, OM8 stated: “Physical distancing has stopped me from having a life that allows me to survive. It is unnatural for me to be physically distancing myself from other human beings.” OM8 reported struggling with the lack of face-to-face interaction, which she described made her feel isolated. For participants who were more actively engaged in their community prior to the pandemic, the restrictions resulted in feelings of isolation that may not have been present before.

Family, Friend, Healthcare Provider, and Community Support Mitigated the Impact of Physical Distancing Restrictions during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Oasis member participants identified receiving emotional, instrumental, and informational support from family, friends, healthcare providers and community organizations during the COVID-19 pandemic. This support reduced the impact of physical distancing restrictions. In addition, in the social network maps, most of the participants identified that as a result of attending Oasis programming their social networks had expanded. This expansion was found to be supportive of participants during the COVID-19 pandemic as it provided them with social support from other Oasis members and from the site coordinators.

Family

In their social network map, six of the members identified family members in their innermost circle and shared that their family was an important source of instrumental and emotional support. For example, three of the members were too afraid to go grocery shopping and had family members deliver groceries to them (instrumental support): “My daughter comes from Innisfil [an hour and a half away from Hamilton], does my groceries for me and puts them away” (OM2). OM2 daughter’s actions demonstrate the support and care her family provide for her. Another member shared that her son moved in with her and her husband when the pandemic started: “My son has been with us since February. He is taking care of my husband and me as we are both battling cancer.” (OM6). OM6 additionally reported that her son did not visit his family (wife and two children) while he was caring for OM6 and her husband to avoid possible spread of the virus. OM6’s son put the needs of his parents above his own to ensure that they were safe and well supported, demonstrating emotional and instrumental support. Lastly, six member participants reported that family members called them on a regular basis to ensure that they were doing okay, thus providing emotional support, with two of the members adding that their grandchildren were an important source of emotional support: “My granddaughter is three years old, and she is the one that keeps me going.” (OM6). Speaking to and/or seeing grandchildren was a highlight of these two participants’ days, which illustrates that family members provide support in a variety of ways.

On the other hand, three of the members reported that they did not receive family support during the pandemic: “[Before the pandemic started] I used to hear from [my family] at least every other week. I have not heard from anybody in my whole family [since the pandemic started].” (OM4). While completing the social network map, OM4 shared that she did not know why her family had not checked in on her and that she no longer felt like her family was a part of her social network. The three Oasis member participants who did not receive support from their family relied on their friends for that support.

Friends

All the Oasis member participants described giving and/or receiving emotional support from at least one friend. For example, OM4 shared: “I hear from them [friends] either by telephone, or they make a point of banging on my door and asking me how I am doing and if I would like to go out for a walk.” (OM4). OM4 mentioned that she was not very close to her family; therefore, she really valued and appreciated her friends checking in on her. Similarly, OM7, who immigrated to Canada ten years ago, shared that staying in contact with her friends from her country of origin was important for her: “It is a special time for us [my friends and I] to listen to each other, and how we are experiencing the pandemic.” (OM7). Emotional support between her and her friends was provided by sharing how COVID-19 had impacted them. In addition, seven of the members expressed that even though they had supportive families, they were grateful to be in contact with at least one friend, with many of them identifying at least one friend in the innermost circles of their social network maps.

Healthcare Providers

Six of the Oasis member participants identified a healthcare provider(s) in the outermost circles of their social network map and shared that during the pandemic they were supported by at least one healthcare provider (pharmacist, family doctor, personal support worker, nurse) by receiving check-in phone calls, attending virtual appointments (when possible), and delivering medications free of charge, thus demonstrating emotional, instrumental, and informational support. Examples of such support were provided when OM2 and OM5 respectively said: “I put my pharmacist down [in the social network diagram] because I talk to him a lot. He even phones me to find out what is going on. They [pharmacy] now deliver my stuff, where I used to go out and pick it up.” and “My nurse calls me once a week to see how I am doing.”. These two participants described these phone calls as helpful, and that they appreciated knowing that they were supported by their healthcare team. Three of the participants mentioned that they had enjoyed having virtual appointments as they no longer had to figure out how they were going to get to and from their medical appointments: “I don’t have to take him [husband] to the doctor’s office or hospital anymore. It is hard for me to take him out, so this has made it easier.” (OM2). Even though OM2 shared that virtual appointments were a positive outcome of the pandemic, she also mentioned that because she was not leaving her home for medical appointments, she was at home more often than she would like.

Community Support

Community services such as the public pool, church, Oasis, and the public library, are places where eight of the members identified building social connections. Six of the members remained connected with people that they had met at community programs. For example, OM8 shared that she continued to communicate with a group of grandparents that have been estranged from their grandchildren by a daughter or son: “We [the group of estranged grandparents] are now connecting virtually.” (OM8). OM8 shared that a positive outcome of the pandemic was being introduced to virtual platforms that she can use to remain connected with others.

In their social network maps, four of the Oasis member participants identified another Oasis member in the two outer most circles and reported remaining in contact with them during the pandemic. For example, one of the Oasis member participants shared: “I have gotten a lot closer to her [another Oasis member]. We talk every time we meet, like at the grocery store or when we are out on a walk. We didn’t do that before [before joining Oasis].” (OM1). In her social network map, OM1 identified 14 contacts; thirteen of the contacts were family members or a health care provider, one contact (in the outer most circle) was another Oasis member. Joining Oasis resulted in OM1 meeting another member that she now identified as a friend and source of support. Similarly, one of the Oasis member participants shared “My husband and I moved to the building in 2018 and we didn’t know anybody. Joining Oasis was good for us. The staff and other members have been really nice and supportive.” (OM9). OM9 identified another Oasis member in the outermost circle of her social network map. Even though she also identified friends, healthcare providers and family members in her map, it appears that it was important for her to have friends in close physical proximity. Joining Oasis provided her with the opportunity to build those friendships. Additionally, one of the site coordinators described that three of the members are avid readers and decided to start a book exchange: “We have a few members exchanging books on their own. I can also think of 3 different members that call to check in on each other.” (SC1). To facilitate the book exchange while following physical distancing recommendations, the site coordinators helped with the pickup and delivery of the books: “The site coordinators helped to pass some books along, and that has been a godsend.” (OM3). Through the book exchange, OM3 was able to continue to engage in something that was meaningful to her (reading), and to remain connected to the other Oasis members she was exchanging books with. Without Oasis, this is something she would not have been able to do. Similarly, OM3 shared: “We [Oasis members] have all taken the time to pass the time of day [when they see each other in the building] and ensure that we are doing okay.” (OM3). Without previous Oasis in-person activities, the members would not have been able to have those small, but significant, interactions with other residents.

Six of the members reported maintaining contact with the Oasis site coordinators, with five identifying the site coordinators in their social network maps; four in the outer most circles, one in the innermost circle. In addition to emotional support, Oasis site coordinators reported providing informational and instrumental support:

“We [site coordinators] gave them [Oasis members] a list of agency names and phone numbers for things like Canada’s Emergency Response Benefit, meals on wheels, and heart to home meals. We also included grocery delivery numbers, just so that they would have those resources if they needed them.” (SC1).

Moreover, the site coordinators provided instrumental support by helping two Oasis members fill out government-related documentation (applying for Canada’s Emergency Response Benefit and updating driver’s licence). Similarly, one of the members was afraid of taking public transportation and relied on the site coordinators for getting her cat’s food “She [the site coordinator] bought stuff for my cat and brought it up and put it outside my door.” OM3. Without this instrumental support, the members would have had to find other means to get their errands done or neglect them all together.

Five of the participants shared that the site coordinators’ check-in phone calls made them feel like they mattered and like somebody cared, “Just knowing that they [site coordinators] cared enough to keep calling and dropping off little goodie bags, it made me feel like somebody cared about me.” (OM7). Similarly, OM5 shared “At least we know that they [site coordinators] are out there and that they care. That makes you feel good.” (OM5). Therefore, in addition to providing social connection, the check-in phone calls served as an important reminder to participants that other people care about them.

Although not all the participants expressed needing support from Oasis, seven of them mentioned that they knew they could rely on the site coordinators for support, if needed. Just knowing that the site coordinators would provide help if needed was reassuring to participants: “I am not in that kind of position where I require that kind of help, I am very independent. But just knowing that there is somebody around if you really do need it, it is a nice feeling.” (OM3). Oasis member participants’ recognition that they could count on the site coordinators for support if needed was also reflected in four of the participants’ social network maps.

Overall, six of the Oasis member participants identified either another Oasis member and/or the site coordinators in their social network map. When comparing the social network maps of the members that identified Oasis (site coordinators and/or another Oasis member) in their map to the members that did not, it was found that those who identified Oasis had one to no contacts labelled as “friends” in their map, with all of their contacts labelled as “family” and/or “healthcare provider”. On the other hand, members that had not identified Oasis in their map had two or more contacts labelled as “friends” in their network map.

Discussion

Through this qualitative study, our aim was to explore how physical distancing restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic impacted Oasis members and to investigate whether Oasis served as a context for social connection and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Based on data about COVID-19 (Iaccarino et al., 2020; Palmieri et al., 2020; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2020), the study participants’ older age and pre-existing health conditions put them at a higher risk of experiencing more acute illness and related consequences if they were to get the COVID-19 virus. Participants’ vulnerability to COVID-19 resulted in most of the participants taking added precautions to avoid getting the virus, such as cancelling external caregiving support. As suggested by the COVID-19 Social Connectivity Paradox (Smith et al., 2020) physical distancing protected Oasis members by reducing their risk of getting COVID-19, but in doing so, it harmed their physical and social wellbeing by reducing opportunities for social interaction and physical activity.

For many of the Oasis member participants, the few social interactions that they had throughout the week happened when they left their home for services essential and meaningful to them such as getting groceries, going for medical appointments and picking up books at the library. Natural neighbourhood networks refer to relationships and interactions that are not ‘formal,’ but are informal, everyday encounters with non-family members, such as a grocery store cashier (Gardner, 2011). Results from this study support previous findings that informal interactions with natural neighbourhood networks provide older adults with an opportunity for social interaction and engagement in life, enhancing overall wellbeing (Gardner, 2011).

As a result of physical distancing recommendations, some of the participants either stopped or reduced the frequency of their daily walks. Frequency of walks was impacted by closure of indoor spaces (such as shopping malls), and fear of not being able to follow physical distancing recommendations in outdoor, crowded, spaces. Similarly, in a cross-sectional study conducted in Japan (Yamada et al., 2020) that investigated changes in physical activity in community dwelling older adults between January 2020 (pre-pandemic) and April 2020 (during the pandemic), it was found that total weekly physical activity was reduced by 65 min (-26.5%). The results of these studies suggest the need for future research on pandemic responses to investigate how communities can support older adults to continue engaging in daily walks, without having their safety compromised.

Regardless of the frequency of in-person interactions pre-COVID-19, as a result of physical distancing restrictions, some of the members that had not felt isolated before COVID-19 reported feeling isolated, and some reported exacerbated feelings of isolation. These results are consistent with literature published at the beginning of the pandemic, when this study was conducted, about the impact of physical distancing restrictions on social isolation and feelings of loneliness (Luchetti et al., 2020; Van Tilburg et al., 2020).

Impact of Oasis during the COVID-19 Pandemic

The Canadian aging in place community model Oasis was implemented in a NORC in Hamilton, Ontario a year prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. The support provided to members by the Oasis site coordinators and other Oasis members while physical distancing restrictions were in place during the COVID-19 pandemic were perceived by participants as having been supportive of members’ social wellbeing.

Six categories of older adults that participate in NORC-based programs have been identified in the literature: consciously no involvement; involved, but not consciously; relationship with staff only; selectively involved with a strong sense of security; NORC program leaders; and dependence on the NORC program (Greenfield & Fedor, 2015). In our study, the six Oasis members that benefitted the most from Oasis during the COVID-19 pandemic, and that consequently identified the site coordinators and/or other members in their social network, were individuals who had few contacts in their network, did not have a “friend” contact in their network prior to joining Oasis, or did not have anyone in their network that had the knowledge to provide instrumental support, such as filling out government forms. Following Greenfield and Fedor’s (2015) categorization of NORC-based program participants, these members could be categorized as relationship with staff only (only stayed in contact with the site coordinators) and dependence on the NORC program (did not have any, or very limited, support from friends outside of other Oasis members). Additionally, one Oasis member participant did not identify anyone from Oasis in their social network map but did express comfort in knowing that the site coordinators could help her, if needed. This member could be categorized as selectively involved with a strong sense of security; she had a supportive social network but knew she could reach out to the site coordinators, as needed. Thus, for these participants, Oasis served as a context for social connection and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. On the other hand, the two Oasis member participants that did not identify anyone from Oasis on their map or expressed that they would reach out to site coordinators for help, only identified two and three contacts, respectively, in their social network maps. These two Oasis members identified that they only attended Oasis programming a few times per month. There may be personal factors for why these two participants identified few contacts in their social network maps such as being selective on who they allow in their personal lives and preferring to keep to themselves.

One of Oasis’ core pillars is to enhance opportunities for social connection. It has been suggested that spatially proximate contacts are uniquely positioned to provide companionship and support to community-residing older adults (Litwin et al., 2015). For example, in a study conducted in Europe it was found that for older adults age 65–79, having spatially proximate contacts was associated with fewer depressive symptoms (Litwin et al., 2015). The importance of having spatially proximate contacts while following physical distancing restrictions is illustrated in the book exchange that was initiated by three Oasis members. The book exchange was made possible because the members live in proximity to each other, allowing for a quick pick-up and delivery of books.

Social networks are comprised of peripheral (for example, non-intimate friends from church) and intimate (for example, intimate friends and parents) members (Bruggencate et al., 2018). Peripheral relationships with neighbours have been found to contribute to feelings of social connectedness, safety and security (Bruggencate et al., 2018). As shared by a participant, while physical distancing restrictions were in place, when members saw each other around the building they took the time to check-in on each other. These small, but significant interactions, illustrate that Oasis helped create peripheral connections which were a source of social support to some of the members during the COVID-19 pandemic.

An important element of Oasis is that it connects members to pre-existing community services. In a study conducted in a Canadian NORC, it was found that older adults have a general lack of consistent and concrete information related to what to do in an emergency situation, such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Kloseck et al., 2014). An aging in place model like Oasis can support the dissemination of information so that residents are prepared and can be connected to the resources that they need when an emergency, like the COVID-19 pandemic, occurs. To support increased knowledge of available community services that could help members during the pandemic, in the monthly care-packages delivered by the Oasis site coordinators, members were provided with information about community services, such as grocery delivery services. In addition, the site coordinators helped one of the members with filling out the required documents to receive the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (financial support). Thus, Oasis was able to connect members to community and government services during the pandemic.

Implications for Aging In-place Community Models

In a national online survey of Canadians conducted by the National Institute on Ageing in partnership with TELUS Health (National Institute on Ageing, 2020), it was found that as a result of the impact of COVID-19 on the long-term care sector, 60% of all Canadians and 70% of older Canadians, have changed their opinion about moving to a long-term care or retirement home, with 91% of all Canadians and almost a 100% of all older Canadians, reporting that they plan on living in their own home for as long as possible. With cities and older populations growing at a rapid pace, proactive -rather than reactive- community solutions are needed.

Aging in place community models, such as Oasis, are emerging as a promising approach to help Canadians to remain living at home for as long as possible. As illustrated in this study, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the impact that pre-existing community supports can have on supporting community-dwelling older adults during a crisis, such as pandemics. Although emergency preparedness was not an element of the Oasis model, two of Oasis’ objectives were found to be of support to participants during the COVID-19 pandemic: strengthening social connectivity, and connection to pre-existing community services. Similarly, in a study conducted in Rome and Genova, Italy (Palombi et al., 2020), older adults enrolled in a community-based proactive monitoring program called Long Live the Elderly! (LLE) had lower death rates than those of the general population. LLE supports older adults living in the community by strengthening social networks and by facilitating connection with social and health services (Palombi et al., 2020).

Aging in place community models are encouraged to incorporate emergency preparedness in their planning, which should include enhancing opportunities for social connection, and having a point-person that can facilitate connections with existing health and social services. As relationship building takes time, federal and provincial stakeholders need to recognize the funding of “aging in place” community models as a priority, so that communities can proactively develop and implement appropriate community supports.

Limitations

A limitation of this study is that only members and site coordinators from a single Oasis site were interviewed, thus the results may not be generalizable outside of this context for other Oasis sites or aging in place community models. Although all Oasis sites have the same overarching goal and are guided by the same pillars, sites are member-driven and community needs differ between sites, thus activities and supports offered at each location differ. Therefore, this study offers an insight into the possible impact of community-driven programs on older adults’ experience of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our study also had a small sample size, with only one male and one participant from an ethnic minority which limits the generalizability of our study findings. In addition, we did not investigate the influence of participants’ socioeconomic status on their experience with physical distancing. Similarly, we did not have access to demographic information from residents that were eligible to join Oasis but chose not to. Future research could address the impact of gender and socioeconomic status on the of crisis preparedness and responsiveness and whether socioeconomic status influences engagement in community programs like Oasis. The goal of our study was not to achieve generalizability, but rather, transferability by employing rich descriptions of members’ experiences and possible implications for NORCs and aging in place models. Findings from this study are encouraged to be used in conjunction with other studies or to inform future research on how aging in place models can support older adults during an emergency.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic and associated physical distancing restrictions impacted Oasis member participants’ physical and social wellbeing by limiting opportunities for in-person interaction and physical activity. The connections formed with other Oasis members pre-pandemic, and the ongoing support provided by the site coordinators, was perceived by participants as having been supportive of Oasis members’ wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study’s findings illustrate that community programs like Oasis acted as a source of resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic, by providing a context for connectivity and wellbeing. Thus, to ensure community-dwelling older adults are well-supported during emergency situations, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, we encourage communities to be proactive in their planning by identifying NORCs and implementing NORC-based programs, like Oasis, that focus on promoting social networks and facilitating the connection of residents to pre-existing community services.

Biographies

Laura Garcia Diaz, MSc

is a dual degree candidate (MSc Occupational Therapy/PhD Rehabilitation Sciences) in the School of Rehabilitation Science at McMaster University. To support a more systematic approach to the development, implementation, and evaluation of dementia-friendly communities, Laura’s work focuses on evaluation research.

Evelyne Durocher, OT, PhD

is an Occupational Therapist and Assistant Professor in the School of Rehabilitation Science at McMaster University. Her current research focuses on ethics and rehabilitation practice, specifically relating to questions of justice, vulnerability and equity in healthcare services for older adults. Her goals is to improve the health and social care experiences of older adults, family members and healthcare professionals.

Carrie McAiney, PhD

is an Associate Professor in the School of Public Health and Health Systems at the University of Waterloo, the Schlegel Research Chair in Dementia with the RIA, and Scientific Director of the Murray Alzheimer Research and Education Program (MAREP). As a health services researcher, Carrie works collaboratively with persons living with dementia, family care partners, providers and organizations to evaluate the impact and implementation of interventions and approaches that aim to enhance care and support for individuals living with dementia and their family members, and to improve the quality of work life for dementia care staff.

Julie Richardson, PT, PhD

is a Professor in the School of Rehabilitation Science. She is interested in interventions to promote mobility and lower-extremity functioning in older adults as well as risk factor assessment for mobility decline and functioning with aging and the health transitions that older persons undergo in the process of disablement. Julie is focused on identifying persons at risk for functional decline and rehabilitation interventions to maintain their health for those with chronic illness.

Lori Letts, OT, PhD

is a Professor in the School of Rehabilitation at McMaster University. Lori’s current research focuses on older adults with chronic illnesses and finding ways to help them to live with and manage their conditions while being active community-dwellers. Lori’s research has her involved in work in primary care and other community settings. She is also involved in research to identify and intervene in preventative ways so that people’s engagement occupation and health are optimized.

Author’s Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection was performed by Laura Garcia Diaz. Data analysis was performed by Laura Garcia Diaz, Evelyne Durocher and Lori Letts. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Laura Garcia Diaz and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Availability of Data and Material

Participants of this study did not agree for the interview data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available. The materials used for this study (interview guide and social network mapping activity) are available from the corresponding author LGD on request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

This study received approval by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (REB Project 5098).

Consent to Participate

Oral informed consent was obtained by LGD from all participants prior to starting the phone interviews.

Consent for Publication

All participants signed informed consent regarding publishing anonymized quotes from the interviews.

Conflict of Interests

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

None.

Ethical Treatment of Experimental Subjects (Animal and Human)

No experimental treatment was conducted on either human or animal subjects in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ajrouch KJ, Antonucci TC, Janevic MR. Social Networks Among Blacks and Whites: The Interaction Between Race and Age. The Journals of Gerontology Series B. 2001;56(2):112–118. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.2.S112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC. Measuring social support networks: Hierarchical mapping technique. Generations: Journal of the American Society on Aging. 1986;10(4):10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC, Ajrouch KJ, Birditt KS. The Convoy Model: Explaining Social Relations From a Multidisciplinary Perspective. The Gerontologist. 2014;54(1):82–92. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birks M, Francis K, Chapman Y. Memoing in qualitative research: Probing data and processes. Journal of Research in Nursing. 2008;13:68–75. doi: 10.1177/1744987107081254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bruggencate TT, Luijkx KG, Sturm J. Social needs of older people: A systematic literature review. Ageing and Society. 2018;35(9):1745–1770. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X17000150. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Norman GJ, Berntson GG. Social isolation. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2011;23:887–911. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06028.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research. (2011). A Focus on Seniors and Aging. Retrieved August 2, 2020, from https://www.homecareontario.ca/docs/default-source/publications-mo/hcic_2011_seniors_report_en.pdf?sfvrsn=14

- Carcary M. Enhancing trustworthiness in qualitative inquiry. Journal of Business Research Methods. 2009;7:11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructionist methods. In: Denzin N, Lincoln Y, editors. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. 2. Thousand Oaks; 2000. pp. 509–533. [Google Scholar]

- Davey J, De Joux V, Nana G, Arcus M. Accommodation Options for Older People in Aotearoa/New Zealand. New Zealand: Centre for Housing Research Aotearoa; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Desclaux A, Badji D, Gautier Ndione A, Sow K. Accepted monitoring or endured quarantine? Ebola contacts’ perceptions in Senegal. Social Science and Medicine. 2017;178:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossey E, Harvey C, McDermott F, Davidson L. Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;36:717–732. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller HR, Ajrouch KJ, Antonucci TC. The Convoy Model and Later-Life Family Relationships. Journal of Family Theory and Review. 2020;12(2):126–146. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner PJ. Natural neighborhood networks - Important social networks in the lives of older adults aging in place. Journal of Aging Studies. 2011;25(3):263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2011.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. (2020). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Canada’s response. Retrieved September 5, 2020, from https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/canadas-reponse.html#support

- Greenfield EA. Community aging initiatives and social capital: Developing theories of change in the context of NORC supportive service programs. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2014;33(2):227–250. doi: 10.1177/0733464813497994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield EA, Bowers BJ. Support from Neighbors and Aging in Place: Can NORC Programs Make a Difference? The Gerontologist. 2016;56(4):651–659. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield EA, Fedor JP. Characterizing Older Adults’ Involvement in Naturally Occurring Retirement Community (NORC) Supportive Service Programs. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2015;58(5):449–468. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2015.1008168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawryluck L, Gold W, Robinson S, Pogorski S, Galea S, Styra R. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004;10:1206–1212. doi: 10.3201/eid1007.030703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz, A., Peters, L., & Truschkat, I. (2015). How to do Qualitative Structural Analysis : The Qualitative Interpretation of Network Maps and Narrative Interviews. Sociological Research Online, 21.

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith T, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and Social Isolation as Risk Factors for Mortality: A Meta-Analytic Review. Perspective on Psychological Science. 2015;10(2):227–237. doi: 10.1177/1745691614568352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social Relationships and Mortality Risk: A Meta-analytic Review. PLoS Medicine. 2010;7(7):e1000316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House J. Work stress and social support. Addison Wesley; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt ME, Ross LE. Naturally Occurring Retirement Communities: A Multiattribute Examination of Desirability Factors. The Gerontologist. 1990;30:667–674. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt M, Gunter-Hunt G. Naturally occurring retirement communities. Journal of Housing for the Elderly. 1986;3:3–22. doi: 10.1300/J081V03N03_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iaccarino G, Grassi G, Borghi C, Ferri C, Salvetti M, Volpe M. Age and Multimorbidity Predict Death among COVID-19 Patients: Results of the SARS-RAS Study of the Italian Society of Hypertension. Hypertension. 2020;76(2):366–372. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloseck M, Gutman GM, Gibson M, Cox L. Naturally Occurring Retirement Community (NORC) Residents Have a False Sense of Security That Could Jeopardize Their Safety in a Disaster. Journal of Housing for the Elderly. 2014;28(2):204–220. doi: 10.1080/02763893.2014.899539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kotwal AA, Holt-Lunstad J, Newmark RL, Cenzer I, Smith AK, Covinsky KE, Escueta DP, Lee JM, Perissinotto CM. Social Isolation and Loneliness Among San Francisco Bay Area Older Adults During the COVID-19 Shelter-in-Place Orders. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2021;69(1):20–29. doi: 10.1111/JGS.16865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwin H, Stoeckel KJ, Schwartz E. Social networks and mental health among older Europeans: Are there age effects? European Journal of Ageing. 2015;12(4):299–309. doi: 10.1007/s10433-015-0347-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchetti M, Lee JH, Aschwanden D, Sesker A, Strickhouser JE, Terracciano A, Sutin AR. The trajectory of loneliness in response to COVID-19. American Psychologist. 2020;75(7):897–908. doi: 10.1037/amp0000690.supp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek KD, Stetzer F, Adams SJ, Popejoy LL, Rantz M. Aging in place versus nursing home care: Comparison of costs to Medicare and Medicaid. Research in Gerontological Nursing. 2012;5(2):123–129. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20110802-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin D, Vagenas D, Pachana NA, Begum N, Dobson A. Gender differences in social network size and satisfaction in adults in their 70s. Journal of Health Psychology. 2010;15(5):671–679. doi: 10.1177/1359105310368177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles M, Huberman M, Saldaña J. Qualitative data analysis. 3. Sage; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Ageing. (2020). Pandemic Perspectives on Ageing in Canada in Light of COVID-19: Findings from a National Institute on Ageing/TELUS Health National Survey. Retrieved August 5, 2020, from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5c2fa7b03917eed9b5a436d8/t/5f85fe24729f041f154f5668/1602616868871/PandemicPerspectives+oct13.pdf

- Nicholson NR. A Review of Social Isolation: An Important but Underassessed Condition in Older Adults. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2012;33:137–152. doi: 10.1007/s10935-012-0271-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ntusi N. Health and rehabilitation sciences in a clinical context. South African Medical Journal. 2019;109(3):139–141. doi: 10.7196/samj.2019.v109i3.013901. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oasis Senior Support Living Inc. (2020). About Oasis. Retrieved October 21, 2020, from https://www.oasis-aging-in-place.com/about-us

- Palmieri L, Vanacore N, Donfrancesco C, Lo Noce C, Canevelli M, Punzo O, Raparelli V, Pezzotti P, Riccardo F, Bella A, Fabiani M, D’Ancona FP, Vaianella L, Tiple D, Colaizzo E, Palmer K, Rezza G, Piccioli A, Brusaferro S, Onder G. Clinical Characteristics of Hospitalized Individuals Dying With COVID-19 by Age Group in Italy. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2020;75(9):1796–1800. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glaa146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palombi L, Liotta G, Orlando S, Gialloreti LE, Marazzi MC. Does the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic Call for a New Model of Older People Care? Frontiers in Public Health. 2020;8:1–4. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. (2020). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Outbreak update, 2020. Retrieved November 2, 2020, from https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection.html

- Smith ML, Steinman LE, Casey EA. Combatting Social Isolation Among Older Adults in a Time of Physical Distancing: The COVID-19 Social Connectivity Paradox. Frontiers in Public Health. 2020;8:403. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SocioCultural Research Consultants LLC. (2019). Dedoose Version 8.3.35, web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data. Retrieved January 19, 2021, from www.dedoose.com

- Statistics Canada. (2016a). Census Profile, 2016 Census - 35250852 [Dissemination area], Ontario and Hamilton, Census division [Census division], Ontario. Retrieved July 20, 2020, from https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016a/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=DA&Code1=35250852&Geo2=CD&Code2=3525&SearchText=L8E1K6&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=All&TABID=2&type=0

- Statistics Canada. (2016b). Hamilton, ON Census Profile 2016. Retrieved July 21, 2020, from https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016b/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=CMACA&Code1=537&Geo2=PR&Code2=35&Data=Count&SearchText=hamilton&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=All&TABID=1

- Statistics Canada. (2016c). Transitions to long-term and residential care among older Canadians. Retrieved July 20, 2020, from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/82-003-x/2018005/article/54966-eng.pdf?st=rJuCbB5Y

- Statistics Canada. (2018). Dissemination area: Detailed definition. Retrieved September 4, 2020, from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/92-195-x/2011001/geo/da-ad/def-eng.htm

- Stiles W. EBMH notebook: Evaluating qualitative research. Evidence-Based Mental Health. 1999;2:99–101. doi: 10.1136/ebmh.2.4.99. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The Government of Ontario. (2020). Statement from the Chief Medical Officer of Health. Retrieved January 4, 2021, from https://news.ontario.ca/en/statement/56515/statement-from-the-chief-medical-officer-of-health

- Thorne S. Interpretive Description: Qualitative Research for Applied Practice. 2. Routledge; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S, Kirkham SR, Flynn-Magee KO. The Analytic Challenge in Interpretive Description. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2004;3:1–11. doi: 10.1177/160940690400300101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]