Abstract

The FaceBase Consortium, funded by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research of the National Institutes of Health, was established in 2009 with the recognition that dental and craniofacial research are increasingly data-intensive disciplines. Data sharing is critical for the validation and reproducibility of results as well as to enable reuse of data. In service of these goals, data ought to be FAIR: Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable. The FaceBase data repository and educational resources exemplify the FAIR principles and support a broad user community including researchers in craniofacial development, molecular genetics, and genomics. FaceBase demonstrates that a model in which researchers “self-curate” their data can be successful and scalable. We present the results of the first 2.5 y of FaceBase’s operations as an open community and summarize the data sets published during this period. We then describe a research highlight from work on the identification of regulatory networks and noncoding RNAs involved in cleft lip with/without cleft palate that both used and in turn contributed new findings to publicly available FaceBase resources. Collectively, FaceBase serves as a dynamic and continuously evolving resource to facilitate data-intensive research, enhance data reproducibility, and perform deep phenotyping across multiple species in dental and craniofacial research.

Keywords: data curation, developmental biology, morphogenesis, craniofacial abnormalities, molecular genetics, genomics

Introduction

Dental and craniofacial research are being transformed by increasingly data-intensive methods across a diversity of omics and imaging modalities. For example, rapidly emerging techniques in single-cell data analysis as well as automated image-based phenotyping produce and consume large volumes of data to drive new discoveries. Data sharing has been recognized as critical for both the validation and reproducibility of results and the reuse of data to drive new research directions or derive maximal utility from control data. The case has been made that data ought to be “FAIR” (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) (Wilkinson et al. 2016) to make them easier for scientists to reuse and reproduce results and to feed data-hungry analytic pipelines. The goal is clear, but achieving it requires significant investment both from laboratories tasked with producing high-quality data and from infrastructure, including biocuration, necessary for “FAIRness.” Data often tend to fall short of the ideal, for example, due to variation in data-processing pipelines preventing direct comparisons across data sets or due to a lack of machine-interpretable metadata that could enhance FAIRness and enable machine learning. Biocurators, moreover, are in short supply (International Society for Biocuration 2018), making it difficult to keep pace with the flood of data produced by modern research methods. Furthermore, when the workload of producing FAIR data sets is offloaded from the scientists that produce data onto biocurators, it is a lost opportunity to train researchers in better data stewardship. Ultimately, it slows “knowledge turns” because data must be curated after the fact and go through round trips from researcher to curator and back, and essential metadata to describe research data may have been lost by the time those data are finally published. The practice of “throwing it over the fence” is suboptimal in both scale and quality of FAIR data being produced. Instead, if researchers can be empowered with tools and training in data curation and socialized to the value of data sharing and citation as a key outcome of their research rather than an afterthought, we can scale biocuration of large data collections of reproducible data to support an open global community of researchers, accelerating knowledge turns and thereby increasing the rate of discovery.

The FaceBase Consortium (Samuels et al. 2020), funded by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), was established in 2009 with the goal of enabling the craniofacial research community to share and reuse research data. FaceBase operates a trustworthy data repository and hosts educational resources that exemplify FAIR principles. FaceBase supports a broad research community encompassing craniofacial development, molecular genetics, and genomics. Initially, FaceBase operated in a “hub-and-spoke” model with approximately 10 spoke projects contributing data sets and online resources over each of the first two 5-y iterations of the FaceBase Consortium (FaceBase 1 and FaceBase 2, respectively). During the last iteration of its hub-and-spoke model, FaceBase 2 began to develop a new approach dubbed “self-curation” wherein the hub focused on developing tools and infrastructure to empower scientists in spoke projects to curate and publish their data with minimal training and oversight from hub curators. Working collaboratively, members of the hub-and-spoke projects jointly developed new data models for organizing and describing data sets, adopted and refined controlled vocabulary for labeling characteristics of data, and produced an ever-growing collection of diverse research data.

In 2019, the NIDCR decided that the third phase of FaceBase (FaceBase 3) would transition from a hub-and-spoke model to operate as a hub only. So began an ambitious experiment in biocuration—to open the hub to the community and make the self-curation methodology honed through interactions with the FaceBase 2 spoke projects available to the research community at large as they elect to contribute data to the hub. Socializing a broad base of researchers to learn to curate data to a level of quality that is FAIR and reproducible has been generally considered untenable. FaceBase 3 demonstrated that this model is indeed viable and scalable, even in an open public community model where researchers may “shop” for a data repository and are not required to share data through the hub. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, FaceBase 3 roughly doubled the number of contributing projects in just over 2 y of its open community model compared with the previous 10 y of hub and spoke. Curators from the hub generally spend a small amount of time training (typically a 1-h online tutorial) members of each new project and follow up for review and feedback on contributed data sets. This has been enough to empower researchers to use FaceBase tooling to organize, annotate, and upload data that meet quality standards exemplifying FAIR guidelines. In addition, FaceBase integrates online visualization tools to enhance the accessibility of data, including a genome track browser, single-cell browser, histology image viewer with annotation editing, orthogonal slice viewer, 3-dimensional (3D) image volume rendering, and surface mesh viewing with landmarks and measures between pairwise combinations of landmarks. Following our approach tocommunity-driven curation, FaceBase recently passed the 1,000th data set milestone, has expanded its community to a broader consortium of projects, and demonstrated that its structure can support reproducible results.

Principles of the Community-Driven Hub

FaceBase uses the DERIVA (Discovery Environment for Relational Information and Versioned Assets) platform for data-intensive sciences built with FAIR principles at its core (Schuler et al. 2016; Bugacov et al. 2017). DERIVA provides a unique platform for building online data resources consisting of a metadata catalog with rich data modeling facilities and expressive ad hoc query support (Czajkowski et al. 2018), file storage with versioning and fixity, persistent identifiers for all data records, user-friendly desktop applications for bulk data transfer and validation, semantic file containers (Chard et al. 2016), and intuitive user interfaces for searching, displaying, and data entry that adapt to any data model implemented in the system (Tangmunarunkit et al. 2021). Building on this foundation, we devised and employed the following strategy for self-serve data curation.

Stay Agnostic with Respect to the Data Model

In the context of databases, the term data model is used to refer to the structure or schema of data within the database. When supporting a large coalition of researchers with diverse needs and interests, the data model will be challenged with representing an ever-changing research landscape. Database schemata are often outdated within months of their development due to changes in system requirements (Stonebraker et al. 2016). We built system components based on a pattern of inspecting the current state of the data model (i.e., Have new tables been introduced since last time the program was executed? Have tables been altered? Have relationships between tables changed?), then adapting the query expressions accordingly or loading a special configuration (called a “schema annotation”) to instruct the program in how to execute against the current schema (Schuler et al. 2020). This part of the approach ensures that system components in the hub infrastructure can adapt to changes in the data model.

Start with a Simple Data Model and Update Incrementally

While data collections may grow and change, the data model only changes when the organization of data within the database needs updating. Often the rigidity of database-dependent applications (e.g., visualization tools or data-processing pipelines) limits changes or induces significant pains when making updates to the data model (Curino et al. 2009), but following the principle of staying agnostic, we can evolve the system fluidly. We begin with a simple conceptual model (e.g., a structural description of experiments consisting of samples on which analyses produce resulting data) with a few additional attributes (timestamps, file checksums, etc.) to support FAIRness. We then socialize the basic concepts of the schema with users (as collaborators in the formation of the system) and build out incrementally from an initial core to finer levels of details. For example, when we set out to redesign our data model for reproducible omics experiments in 2018, we developed it with the spoke user community engaged and incrementally refined an initial sketch of the new model until we collectively settled on a design that satisfied the objectives for integrating omics pipelines with the hub and reproducing original processed data results from contributing spoke projects (Schuler et al. 2019).

Provide Intuitive Tools, Processes, and Training

Scalability depends on training users to contribute and curate data up to the level of quality needed for secondary analysis. The hub’s role is to socialize the importance of data stewardship best practices and to create a community of researchers that treat data curation not as an afterthought, but as a matter of practice to improve their handling of data. While FaceBase has thus far generally accepted data when ready for public sharing—rather than during experimentation and acquisition—the practices for organizing and labeling data are intended to influence the internal practices of researchers. By directly engaging researchers, we can avoid inefficient round trips between contributors and traditional curators and back. FaceBase provides intuitive web interfaces following common user interaction patterns for data entry forms, efficient multirecord entry, and searching and browsing interfaces. Data entry forms are fully integrated with the database and therefore they ensure that metadata are aligned properly with controlled terminology and organized per the database schema. Using these tools, researchers truly “curate” data—not only initial data entry, but they review, make edits, align to vocabulary terms, and ensure their data are accurately represented.

Employ Automated Data Pipelines

Since contributors “self-curate” data and the data entry forms are fully integrated into the database, most quality control (QC) procedures are performed upfront, before data are recorded in the system. The system enforces correct usage of data types, semantic alignment with vocabulary terms, and integrity checks on the relationships between records. These upfront QC checks must be satisfied for data even to be entered. File integrity checks are performed following the “end-to-end” principle (Saltzer et al. 1984) to ensure that what is retrieved from FaceBase is exactly what was uploaded. In addition, another round of QC is subsequently performed by our more recently developed QC pipeline that executes a series of rules against each data set and flags issues in QC dashboards for contributors to review and resolve. For example, a QC rule checks if sequencing experiments have bioreplicates associated with them and whether sequencing files have been submitted for each bioreplicate. Beyond QC, additional pipelines perform data enhancements such as optimizing imaging data for online visualization, generating image thumbnails, registering data sets with a digital object identifier (DOI) registration agency, and indexing data records for keyword search. The aim of automated data pipelines is to streamline and reduce manual effort, although the effectiveness is yet to be determined and warrants further evaluation.

Revise the Role of Data Curator

Although the FaceBase hub is open to the community, new contributors must submit a short description of their proposed contribution. FaceBase hub and NIDCR program staff review each proposal to ensure that the data meet the priorities, qualities, and needs for the craniofacial and dental research community served by FaceBase. If the proposal is accepted, the hub creates an account for the researcher and grants access to upload and curate their data on the hub. All data sets are reviewed by a hub curator to ensure that they meet FaceBase standards with detailed descriptions, protocol documentation, and use of controlled vocabulary terms. When the hub curation team determines that the data meet our quality standards, the data sets are released and made public. In the community-driven hub, the role of the curator is to train researchers in data curation practices, review and provide feedback, and act as a gatekeeper.

Growth and Impact of FaceBase 3

First, we present details of the growth in the FaceBase data repository for the last 2.5 y of operating in an open community model in terms of significant milestone-driven achievements and a summary of data sets published over that time. We then present a highlight from research that both used and contributed to FaceBase.

Milestones and Recent Data Sets

The open community model coupled with the “self-curation” approach to curation kicked off in the second half of 2019, and despite the global COVID-19 pandemic, FaceBase has onboarded 30 new projects, including an amelogenesis research consortium, and released its 1,000th data set. Researchers have contributed 116 new data sets with detailed descriptions of 2,038 experiments, 10,587 biosample characteristics, and 43,259 new files of nearly 4.5 TB of data. Figure 1 summarizes the growth in contributing research projects (A), new data sets released to the public (B), and an overview of data files across all newly released data sets (E). The figure also shows growing diversification of experiment types (C) and coverage of an increasingly broad array of biological characteristics (D). The hub’s infrastructure supported all these new data types without modification to its fundamental data structures and features, demonstrating the ability for FaceBase to scale flexibly to accommodate an ever-changing landscape in craniofacial and dental research. It also highlights the benefits of “self” curation, since the expertise and resources to curate data scale commensurately with new data contributions. Put in context, relative to the first two 5-y phases of FaceBase, during the initial 2.5 y of FaceBase 3, the number of contributing projects has grown by 1.5-fold, the number of experiments has more than doubled, types of experiments nearly doubled, biosample records more than tripled, and data files nearly quadrupled.

Figure 1.

Growth and diversification of the FaceBase hub data collection. (A) Contributing research projects that have joined FaceBase and released data sets since the second half of 2019; (B) data sets released through FaceBase from new projects; (C) new experiment or assay types now being reported in data sets as a count of the distinct “experiment type” vocabulary terms used to label data sets; (D) biosample characteristics being reported in data sets as a count of the distinct “gene,” “genotype,” and developmental “stage” vocabulary terms used to label data sets; and (E) new data files across all newly released data sets.

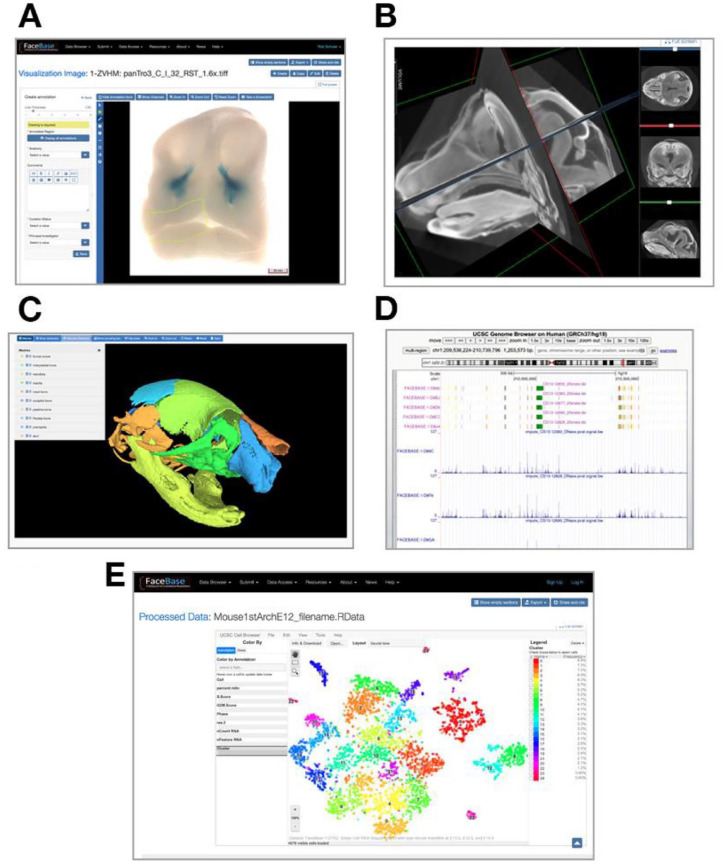

Figure 2 shows interactive, online visualization capabilities integrated as part of FaceBase’s infrastructure. These visualization tools support high-resolution histological data with built-in annotation editing and display, image volumes with orthogonal slice and 3D rendering, surface meshes with landmarks and measurements between pairwise combinations of landmarks, genome annotation track visualization (Kent et al. 2002), and interactive single-cell visualization (Speir et al. 2021). The integration of these tools also represents an effort to collaborate with and reuse tools developed by the broader biomedical research community. FaceBase also supports offline data analyses and visualization through bulk download packages and utilities known as Big Data Bag (BDBag) (Chard et al. 2016). This allows researchers to download whole data sets, all data sets for a project, or select subsets of data based on search results obtained from FaceBase’s data browser. All data are represented in an integrated data model using a common set of vocabularies, most of which are sourced from standardized community termsets, including Uberon (Mungall et al. 2012), Mammalian Phenotype Ontology (Smith and Eppig 2009), Ontology of Craniofacial Development and Malformation (Brinkley et al. 2013), and several others.

Figure 2.

Online visualization capabilities in the FaceBase repository. (A) High-resolution histological data with built-in annotation editing and display, (B) image volumes with orthogonal slice and 3-dimensional rendering, (C) surface meshes with landmarks and measurements between pairwise combinations of landmarks, (D) genome annotation track visualization, and (E) interactive single-cell visualization through integration with the UCSC Cell Browser.

See the Table for a summary of data sets released since late 2019 under the new open community model of data sharing through FaceBase 3. In addition to growing our established data collection on craniofacial development and dysmorphology, several recent contributions have expanded FaceBase to support dental research. Notably, FaceBase is the home for a research consortium generating new models of amelogenesis to improve the understanding of the processes of enamel formation. More details on the 4 projects that make up this consortium may be found here:

Table.

Summary of Recent Data Sets by New Contributing Projects.

| Project ID | Project Name | DOI | Experiment Type(s) | No. of Data Sets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-723Y | Genome-wide Copy Number Variations in a Large Cohort of Bantu African Children | 10.25550/1-723Y | Genome wide association studies (GWAS), genotyping assay, morphometric analysis, secondary analysis | 1 |

| 1-72PM | Epigenomic Atlas of Early Human Craniofacial Development | 10.25550/1-72PM | Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq)assay | 6 |

| 1-A3FC | Enamel Atlas: Systems-Level Amelogenesis Tools at Multiple Levels | 10.25550/1-A3FC | Atom probe tomography, imaging assay, microbeam particle-induced X-ray emission spectroscopy, micro–computed tomography (microCT), micro-infrared spectroscopy, nanoindentation, near-edge X-ray absorption fine structure spectroscopy, optical microscopy, Raman microscopy, scanning electron micrograph, scanning electron microscopy, scanning electron microscopy energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, synchrotron small angle X-ray scattering, wide-angle X-ray scattering | 1 |

| 1-B7CE | Development and Validation of Novel Amelogenesis Models | 10.25550/1-B7CE | Chain termination sequencing assay, comparative phenotypic assessment, genotyping assay, hematoxylin and eosin stain, imaging assay, transcript expression location detection by hybridization chain reaction | 3 |

| 1-ETAC | The Molecular Regulatory Mechanism of Tooth Root Development | 10.25550/1-ETAC | Fluorescence microscopy, hematoxylin and eosin stain, imaging assay, laser capture microdissection (LCM), microCT, microscopy assay, RNAscope in situ hybridization, RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) assay, single-cell RNA-seq assay (scRNA-seq) | 9 |

| 1-ETAE | TGF-β Signaling and Craniofacial Morphogenesis | 10.25550/1-ETAE | RNA-seq assay, scRNA-seq | 1 |

| 1-F5A6 | Genes and Non-coding RNAs Associated with Craniofacial Birth Defects | 10.25550/1-F5A6 | Data analysis, secondary analysis | 4 |

| 1-RBXJ | Proteomics and Genetics of Enamel and Dentin | 10.25550/1-RBXJ | Comparative phenotypic assessment, confocal fluorescence microscopy, hematoxylin and eosin stain, optical microscopy, RNAscope in situ hybridization, scanning electron microscopy | 1 |

| 1-SXS0 | Exploratory Statistical Analysis of Differential Network Behaviors Based on Gene Expression Atlas of Palate Development | 10.25550/1-SXS0 | RNA-seq assay, secondary analysis | 9 |

| 1WVT | Research on Functional Genomics, Image Analysis and Rescue of Cleft Palate | 10.25550/1WVT | Microscopy assay, RNA-seq assay, transcription profiling by array assay | 3 |

| 1WW2 | Anatomical Atlas and Transgenic Toolkit for Late Skull Formation in Zebrafish | 10.25550/1WW2 | Confocal fluorescence microscopy | 2 |

| 1WW6 | RNA Dynamics in the Developing Mouse Face | 10.25550/1WW6 | RNA-seq assay | 1 |

| 1WW8 | Transcriptome Atlases of the Craniofacial Sutures | 10.25550/1WW8 | RNA-seq assay, scRNA-seq | 6 |

| 1WWE | Integrated Research of Functional Genomics and Craniofacial Morphogenesis | 10.25550/1WWE | Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin Sequencing (ATAC-seq), gene summary, RNA-seq assay, scRNA-seq | 46 |

| 1WWG | Epigenetic Landscapes and Regulatory Divergence of Human Craniofacial Traits | 10.25550/1WWG | Enhancer activity detection by reporter gene assay | 23 |

| 1-X7QE | Molecular Regulatory Mechanism of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Adult Mouse Incisors | 10.25550/1-X7QE | Fluorescence microscopy, hematoxylin and eosin stain, LCM, microCT, RNAscope in situ hybridization, RNA-seq assay | 2 |

| 1-X9EM | Defining an Integrated Signaling Network That Patterns the Craniofacial Skeleton | 10.25550/1-X9EM | Nanostring-based assay | 2 |

| 1-Y732 | Timing of Mouse Molar Formation Is Unmoved by Jaw Length Including Retromolar Space | 10.25550/1-Y732 | Imaging assay, microCT, microscopy assay | 1 |

| 1-YA78 | Tissue-Specific Roles of AP-2 Transcription Factors, Tfap2a and Tfap2b, in Dental Development | 10.25550/1-YA78 | MicroCT | 2 |

| 1-YPS4 | Developmental Stage-Specific TF-miRNA Co-regulation during Craniofacial Development | 10.25550/1-YPS4 | Data analysis, secondary analysis | 4 |

| 25NR | Developmental Nonlinearity Drives Phenotypic Robustness | 10.25550/25NR | GWAS, imaging assay, morphometric analysis, quantitative trait locus analysis (QTL) | 1 |

| 3-HXMC | MusMorph, a Database of Standardized Mouse Morphology Data for Morphometric Meta-Analyses | 10.25550/3-HXMC | Imaging assay, microCT, morphometric analysis | 29 |

| 3-KG12 | Progenitor Regulation in Craniofacial Development and Regeneration; Molecular and Cellular Basis of Craniosynostosis | 10.25550/3-KG12 | scRNA-seq, single-nucleus ATAC-seq | 2 |

Only projects that have publicly released data sets since August 2019 are summarized here. Additional projects (not listed here) are preparing data sets for release.

Enamel Atlas: Systems-level Amelogenesis Tools at Multiple Levels (https://doi.org/10.25550/1-A3FC)

Cre Mouse Models to Study Amelogenesis (https://doi.org/10.25550/1-AEEE)

Ameloblast Differentiation and Amelogenesis: Next-Generation Models to Define Key Mechanisms and Factors Involved in Biological Enamel Formation (https://doi.org/10.25550/1-AWCT)

Development and Validation of Novel Amelogenesis Models (https://doi.org/10.25550/1-B7CE)

FaceBase is working with the amelogenesis consortium and other data contributors to bring new data resources for dental researchers online.

FaceBase serves an active research community that currently includes over 700 registered users. Since its inception, FaceBase data have been cited by 210 publications. In just the most recent 6-mo timeframe from August 2021 through January 2022, FaceBase served 7,621 visitors to the site with 33,289 unique page views, 8,471 online image views, 115,217 genome annotation track visualizations, and 44,960 file downloads.

Research Highlight: Secondary Analysis of FaceBase Data

Genetic variants, prenatal environmental exposures, and gene–environment interactions have substantial influences on the prevalence of cleft lip with/without cleft palate (CL/P) (Beaty et al. 2016). Mouse and human genetic studies, as well as epidemiological data, have enabled the identification of a wide array of genetic and environmental risk factors for CL/P (Dixon et al. 2011; Suzuki et al. 2016). However, the etiology of CL/P is not yet fully understood due to the complexity of these genetic and environmental risk factors as well as of gene–environment interactions. In fact, approximately 70% of all cases of CL/P are nonsyndromic, with the remaining 30% classified as syndromic. Since 2009, the FaceBase Consortium has generated a large number of data sets in craniofacial development, including mouse genomic data sets for mRNA, microRNA (miRNA), and enhancers (Brinkley et al. 2016). We analyzed these data in order to identify regulatory networks and temporospatial-specific molecular signatures for noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) and genes during lip and palate development.

ncRNAs consist of a wide variety of nucleic acid species that can be subclassified according to size, including small ncRNAs (e.g., miRNAs) and long ncRNAs (lncRNAs). Small ncRNAs and lncRNAs can regulate the activities of target genes at the transcriptional and/or posttranscriptional levels (Roundtree and He 2016; Gil and Ulitsky 2020). They are abundant in mammalian genomes, with over 13,000 annotated lncRNAs and over 6,000 annotated small ncRNAs reported to date in humans and mice (GENCODE releases 39 and M28, respectively). Although ncRNAs play a crucial role in the morphogenesis of many tissues and organs (Fu et al. 2018), their roles and regulatory networks in craniofacial development remain elusive. Using FaceBase transcriptome data for mRNA and miRNA, we first developed pipelines with the aim to extract mRNAs, miRNAs, and lncRNAs. We then systematically annotated regulatory pairs such as transcription factor (TF)–gene, miRNA–gene, TF–miRNA, miRNA–TF, TF–lncRNA, and lncRNA–gene (here, gene refers to non-TF protein-coding gene), which were deposited in the FaceBase hub. Next, we developed a novel embryonic stage-specific network approach to identify dynamic regulatory mechanisms through feed-forward loops (FFLs), using genomic data from the developing lip and palate, and found several key regulators (TFs: FOXM1, HIF1A, ZBTB16, MYOG, MYOD1 and TCF7; miRNAs: miR-340-5p and miR-129-5p), target genes (Col1a1, Sgms2, and Slc8a3), and signaling pathways (Wnt–Foxo–Hippo pathway [E10.5 to E11.5], tissue remodeling [E12.5 to E13.5], and miR-129-5p–mediated Col1a1 regulation [E10.5 to E14.5]). Our secondary data analyses, along with the experimental validation, contributed to the understanding of the comprehensive regulatory mechanisms involved in craniofacial development (Li et al. 2019, 2020; Yan et al. 2020). See Figure 3 for an overview of the data analysis and integration processes.

Figure 3.

Overview of the FaceBase data analysis and integration with current knowledge of craniofacial anomalies. To identify spatiotemporal expression and role of genes and noncoding RNAs, FaceBase data were analyzed with various bioinformatic tools and methodologies. In addition, the genes and noncoding RNAs predicted through these bioinformatic analyses were cross-referenced with genes and microRNAs reported in craniofacial anomalies (e.g., cleft lip, cleft palate) in humans and mice. The regulatory networks and functions of the candidate genes and microRNAs were further experimentally validated. Some of these findings have been stored at our database, CleftGeneDB, which is publicly available at https://bioinfo.uth.edu/CleftGeneDB/, and the processed data were also deposited into FaceBase (10.25550/1-YPS4 and 10.25550/1-F5A6).

The results obtained through these data analyses were also integrated with the current knowledge of CL/P-related genes identified in humans and mice through our systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature (Suzuki et al. 2018; Gajera et al. 2019; Suzuki et al. 2019). Accumulating evidence shows that expression of ncRNAs is influenced by a wide variety of environmental factors, including prenatal exposure to various chemicals, drugs, and toxins (Hudder and Novak 2008). Therefore, we examined a potential link between miRNAs and several environmental factors that induce CL/P (Yoshioka, Mikami, et al. 2021; Yoshioka, Ramakrishnan, Shim, et al. 2021; Yoshioka, Ramakrishnan, Suzuki and Iwata 2021). Our findings, together with results from ongoing genetic studies, were added to a database for genes and miRNAs related to CL/P (CleftGeneDB) (Xu et al. 2021). Overall, our secondary data analyses will be useful for not only increasing our knowledge of craniofacial morphogenesis but also developing clinical, diagnostic, and preventative interventions for CL/P.

Conclusions

An important aspect of FaceBase’s mission is education and workforce improvement in addition to providing data resources on dental and craniofacial development. Adopting a “self” curation approach not only improves the sustainability of FaceBase but also trains researchers in better data stewardship practices. With respect to FAIR data, FAIRness begins even before the first sample is assayed and the first data are generated. It begins during the study design, when cataloging materials and recording methods. It continues as data are collected, accurately labeled, and correlated with laboratory notebooks. While FaceBase infrastructure may not extend into the researcher’s laboratory, the practices learned through using and interacting with FaceBase are lessons that can be applied back to the lab.

By socializing the research community at large to produce high-quality data sets, FaceBase encourages and trains the research workforce and, we believe, can improve not only data sharing but internal data handling practices and raise the standards within laboratories, among students and early career researchers for handling of data. To that end, as these practices are adopted within labs, the effect is to increase the FAIRness of data early within the research life cycle rather than wrangling and publishing data after the fact (Dempsey et al. 2022). While the entry of complex data sets may never be “easy,” FaceBase users typically find that the greatest effort involved is typically organizing data internal to the lab in preparation for data entry, rather than the data entry forms themselves.

Data are often an overlooked and undervalued product of research. Part of our mission in FaceBase is to educate and train the research community to view data as a critical part of research. Just as one budgets time to manage laboratory notebooks, document protocols, care for laboratory specimens, and prepare manuscripts for publication, research teams must likewise allocate resources for proper handling of data. Curating data for sharing should be factored into the research budget in much the same way that preparing manuscripts for publication is also factored into the research budget. Even with the high standards for curation on FaceBase, it typically takes researchers a few hours to upload and describe their data sets, but for large and complex data sets, it could take at most a couple of weeks in our experience.

FaceBase results have demonstrated that an open community model for data collection, curation, and dissemination is a viable model for building scalable, collaborative communities of researchers. Our near-term plans include usability improvements for both usage and contribution of FaceBase’s data resources. We also plan enhancements to 3D imaging visualization to broaden the types of imaging data we can support and ongoing enhancements to our recently integrated single-cell visualization features. With the growing importance of artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML) to the craniofacial and dental research community, the FaceBase hub is assessing and improving the AI/ML-readiness of its large collection of facial imaging scans. Collectively, FaceBase serves as a dynamic and continuously evolving resource to facilitate data-intensive research, enhance data reproducibility, and perform deep phenotyping across multiple species in dental and craniofacial research.

All data are available at https://www.facebase.org. FaceBase encourages participation and contributions from all researchers throughout the international research community. Please consider contributing to FaceBase by visiting us at https://www.facebase.org/submit/submitting-data/.

Author Contributions

R.E. Schuler, J. Iwata, Z. Zhao, contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, drafted and critically revised the manuscript; A. Bugacov, contributed to design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; J.G. Hacia, T.V. Ho, C. Williams, contributed to data acquisition, critically revised the manuscript; L. Pearlman, contributed to data acquisition and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; B.D. Samuels, contributed to data acquisition and interpretation, drafted and critically revised the manuscript; C. Kesselman, Y. Chai, contributed to conception and design, critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The FaceBase 3 hub is supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (U01-DE028729 to C. Kesselman and Y. Chai). The “research highlight” studies were supported by the National Institutes of Dental and Craniofacial Research (R03DE028340, R03DE026509, R03DE026208 to J. Iwata; R03DE027711 and R03DE028103 to Z. Zhao; and R01DE030122 and R03DE027393 to Z. Zhao and J. Iwata).

ORCID iDs: R.E. Schuler  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8956-5707

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8956-5707

J. Iwata  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3975-6836

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3975-6836

L. Pearlman  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0749-4707

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0749-4707

Data Availability: All data are available at https://www.facebase.org. Data listed in the Table may be found by their respective DOI as indicated.

References

- Beaty TH, Marazita ML, Leslie EJ. 2016. Genetic factors influencing risk to orofacial clefts: today’s challenges and tomorrow’s opportunities. F1000Res. 5:2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkley JF, Borromeo C, Clarkson M, Cox TC, Cunningham MJ, Detwiler LT, Heike CL, Hochheiser H, Mejino JLV, Travillian RS, et al. 2013. The ontology of craniofacial development and malformation for translational craniofacial research. Am J Med Genet C. 163(4):232–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkley JF, Fisher S, Harris MP, Holmes G, Hooper JE, Jabs EW, Jones KL, Kesselman C, Klein OD, Maas RL, et al. 2016. The FaceBase Consortium: a comprehensive resource for craniofacial researchers. Development. 143(14):2677–2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugacov A, Czajkowski K, Kesselman C, Kumar A, Schuler RE, Tangmunarunkit H. 2017. Experiences with DERIVA: an asset management platform for accelerating escience. 2017 IEEE 13th International Conference on E-Science (E-Science); Auckland, New Zealand. New York (NY): IEEE. p. 79–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chard K, D’Arcy M, Heavner B, Foster I, Kesselman C, Madduri R, Rodriguez A, Soliland-Reyes S, Goble C, Clark K, et al. 2016. I’ll take that to go: big data bags and minimal identifiers for exchange of large, complex datasets. IEEE International Conference on Big Data. New York (NY): IEEE. p. 319–328. doi: 10.1109/BigData.2016.7840618 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Curino CA, Moon HJ, Ham M, Zaniolo C. 2009. The PRISM workwench: database schema evolution without tears. ICDE: 2009 IEEE 25th International Conference on Data Engineering; Shanghai, China. New York (NY): IEEE. p. 1523–1526. [Google Scholar]

- Czajkowski K, Kesselman C, Schuler RE, Tangmunarunkit H. 2018. ERMrest: a web service for collaborative data management. 30th International Conference on Scientific and Statistical Database Management (SSDBM 2018); July, 2018; Bozen-Bolzano Italy. ACM. p. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey W, Foster I, Fraser S, Kesselman C. 2022. Sharing begins at home. arXiv 2201.06564v1. https://arxiv.org/abs/2201.06564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dixon MJ, Marazita ML, Beaty TH, Murray JC. 2011. Cleft lip and palate: understanding genetic and environmental influences. Nat Rev Genet. 12(3):167–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Q, Liu CJ, Zhai ZS, Zhang X, Qin T, Zhang HW. 2018. Single-cell non-coding RNA in embryonic development. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1068:19–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajera M, Desai N, Suzuki A, Li A, Zhang M, Jun G, Jia P, Zhao Z, Iwata J. 2019. MicroRNA-655-3p and microRNA-497-5p inhibit cell proliferation in cultured human lip cells through the regulation of genes related to human cleft lip. BMC Med Genomics. 12(1):70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil N, Ulitsky I. 2020. Regulation of gene expression by cis-acting long non-coding RNAs. Nat Rev Genet. 21(2):102–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudder A, Novak RF. 2008. MiRNAs: effectors of environmental influences on gene expression and disease. Toxicol Sci. 103(2):228–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Society for Biocuration. 2018. Biocuration: distilling data into knowledge. PLoS Biol. 16(4):e2002846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, Roskin KM, Pringle TH, Zahler AM, Haussler D. 2002. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 12(6):996–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A, Jia P, Mallik S, Fei R, Yoshioka H, Suzuki A, Iwata J, Zhao Z. 2020. Critical microRNAs and regulatory motifs in cleft palate identified by a conserved miRNA-TF-gene network approach in humans and mice. Brief Bioinform. 21(4):1465–1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A, Qin G, Suzuki A, Gajera M, Iwata J, Jia P, Zhao Z. 2019. Network-based identification of critical regulators as putative drivers of human cleft lip. BMC Med Genomics. 12(Suppl 1):16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mungall CJ, Torniai C, Gkoutos GV, Lewis SE, Haendel MA. 2012. Uberon, an integrative multi-species anatomy ontology. Genome Biol. 13(1):R5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roundtree IA, He C. 2016. RNA epigenetics—chemical messages for posttranscriptional gene regulation. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 30:46–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltzer JH, Reed DP, Clark DD. 1984. End-to-end arguments in system-design. ACM Trans Comput Syst. 2(4):277–288. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels BD, Aho R, Brinkley JF, Bugacov A, Feingold E, Fisher S, Gonzalez-Reiche AS, Hacia JG, Hallgrimsson B, Hansen K, et al. 2020. FaceBase 3: analytical tools and fair resources for craniofacial and dental research. Development. 147(18):dev191213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler R, Bugacov A, Blow M, Kesselman C. 2019. Toward FAIR knowledge turns in bioinformatics. IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM); San Diego, CA. New York (NY): IEEE. p. 1240–1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler R, Czajkowski K, D’Arcy M, Tangmunarunkit H, Kesselman C. 2020. Towards co-evolution of data-centric ecosystems. 32nd International Conference on Scientific and Statistical Database Management; July 7–9, 2020; New York, NY. ACM. Vol. 4. p. 1–12. doi: 10.1145/3400903.3400908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler RE, Kesselman C, Czajkowski K. 2016. Accelerating data-driven discovery with scientific asset management. The IEEE 12th International Conference on eScience; Baltimore, MD. New York (NY): IEEE. p. 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Smith CL, Eppig JT. 2009. The mammalian phenotype ontology: enabling robust annotation and comparative analysis. Wires Syst Biol Med. 1(3):390–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speir ML, Bhaduri A, Markov NS, Moreno P, Nowakowski TJ, Papatheodorou I, Pollen AA, Raney BJ, Seninge L, Kent WJ, et al. 2021. UCSC cell browser: visualize your single-cell data. Bioinformatics. 37(23):4578–4580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stonebraker M, Deng D, Brodie ML. 2016. Database decay and how to avoid it. IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data); Washington, DC. New York (NY): IEEE. p. 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A, Abdallah N, Gajera M, Jun G, Jia P, Zhao Z, Iwata J. 2018. Genes and microRNAs associated with mouse cleft palate: a systematic review and bioinformatics analysis. Mech Dev. 150:21–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A, Li A, Gajera M, Abdallah N, Zhang M, Zhao Z, Iwata J. 2019. MicroRNA-374a, -4680, and -133b suppress cell proliferation through the regulation of genes associated with human cleft palate in cultured human palate cells. BMC Med Genomics. 12(1):93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A, Sangani DR, Ansari A, Iwata J. 2016. Molecular mechanisms of midfacial developmental defects. Dev Dyn. 245(3):276–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangmunarunkit H, Shafaeibejestan A, Chudy J, Czajkowski K, Schuler R, Kesselman C. 2021. Model-adaptive interface generation for data-driven discovery. CoRR. abs/2110.01781. https://arxiv.org/abs/2110.01781 arXiv preprint.

- Wilkinson MD, Dumontier M, Aalbersberg IJ, Appleton G, Axton M, Baak A, Blomberg N, Boiten JW, da Silva Santos LB, Bourne PE, et al. 2016. The FAIR guiding principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci Data. 3:160018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu HD, Yan FF, Hu RF, Suzuki A, Iwaya C, Jia PL, Iwata J, Zhao ZM. 2021. CleftGeneDB: a resource for annotating genes associated with cleft lip and cleft palate. Sci Bull. 66(23):2340–2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan F, Jia P, Yoshioka H, Suzuki A, Iwata J, Zhao Z. 2020. A developmental stage-specific network approach for studying dynamic co-regulation of transcription factors and microRNAs during craniofacial development. Development. 147(24):dev192948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka H, Mikami Y, Ramakrishnan SS, Suzuki A, Iwata J. 2021. MicroRNA-124-3p plays a crucial role in cleft palate induced by retinoic acid. Front Cell Dev Biol. 9:621045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka H, Ramakrishnan SS, Shim J, Suzuki A, Iwata J. 2021. Excessive all-trans retinoic acid inhibits cell proliferation through upregulated microRNA-4680-3p in cultured human palate cells. Front Cell Dev Biol. 9:618876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka H, Ramakrishnan SS, Suzuki A, Iwata J. 2021. Phenytoin inhibits cell proliferation through microRNA-196a-5p in mouse lip mesenchymal cells. Int J Mol Sci. 22(4):1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]