Abstract

Previous research supports a link between school-related factors, such as bullying and school connectedness, and suicidal thoughts and behaviors. To deepen understanding of how school experiences may function as both protective and risk factors for youth struggling with suicidal thoughts and behaviors, this qualitative study explored multiple perspectives. Specifically, in-depth interviews were conducted with adolescents previously hospitalized for a suicidal crisis (n = 19), their parents (n = 19), and the professionals they may interact with in schools and hospitals (i.e., school professionals [n = 19] and hospital providers [n = 7]). Data were analyzed using applied thematic analysis revealing three main themes related to perceptions of how school experiences can positively or negatively impact mental health: School activities, school social experiences, and school interventions. An emergent theme related to the complexity of suicide-related risk identified the ways in which school experiences may intersect with other environmental, biological, and psychological factors. Findings underscore the need for school-based approaches to address the unique academic, social, and emotional needs of students with suicide-related risk that complement the supports and services provided in their home and community.

Keywords: Suicidal thoughts and behaviors, qualitative research, school, adolescent, parent, professional

Schools have been called upon to provide systematic suicide prevention programs that span from upstream approaches for bolstering protective factors against suicide to tertiary services for youth with heightened risk for suicide (e.g., Miller, 2021; Singer et al., 2019). School mental health professionals (e.g., psychologists, counselors, social workers, nurses) may be charged with delivering universal suicide prevention programs, providing targeted interventions for social and emotional concerns, formulating risk assessments, providing referrals to care, communicating with community providers, supporting school re-entry following a mental health crisis, and coordinating postintervention following a student death (Joshi et al., 2015; Surgenor et al., 2016). Although these supports and services vary in scope, frequency, and intensity, inherent to all these practices is the aim of mitigating risk related to suicide and reinforcing protective factors against suicide.

Although varying across cultural context (Marraccini, Griffin, et al., 2022; Marraccini, Ingram, et al., 2022), school-related risk and protective factors of suicide can be considered within an ideation-to-action framework. Ideation-to-action theories of suicide postulate distinct pathways of suicidal thoughts (i.e., suicidal ideation, including thinking about or making a plan about suicide) to suicidal behaviors (i.e., action, including attempting suicide; Klonsky et al., 2018). For example, the interpersonal theory of suicide posits that hopelessness about feelings of disconnect and burdensomeness may contribute to suicidal ideation, with reduced fear of death, increased pain tolerance, and access to means facilitating the move from thinking about suicide to acting on suicide (Van Orden et al., 2010). Aligned within this model, schools can contribute protective effects against suicidal ideation by enhancing feelings of belongingness and connectedness between school community members (Marraccini & Brier, 2017), but can also confer risk for suicidal ideation if negative experiences such as bullying, social difficulties, and discrimination are not prevented (Assari et al., 2017; Holt et al., 2015; van Geel et al., 2022; Walker et al., 2017). Moreover, school-based mental health preventions and interventions, school referrals to care, and school structures that prevent access to means may play a role in disrupting the shift from ideation to action.

Few studies have addressed school factors that may influence risk for suicidal thoughts and behaviors in clinical samples of adolescents. However, preliminary findings suggest that feeling connected to school is associated with improved recovery from a mental health crisis (King et al., 2019; Marraccini, Resnikoff, et al., 2021). Conversely, stressors such as bullying experiences and academic difficulties can confer risk for suicidal thoughts and behaviors and rehospitalization (Luukkonen et al., 2009; Marraccini, Resnikoff, et al., 2021; Tossone et al., 2014). Although this formative work helps establish the significance of school-related relationships for recovery from a mental health crisis, missing from this work is an exploration of the mechanisms linking school-related experiences with mental health outcomes in adolescents with suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

Drawing on previous work that has identified social (e.g., having to describe to their peers where they have been), academic (work remediation), and emotional (management of mental health symptoms) concerns for adolescents returning to school following psychiatric hospitalization (Marraccini & Pittleman, 2022; Preyde et al., 2017, 2018), the present study aimed to deepen understanding of how school-related experiences may influence suicidal thoughts and behaviors in adolescents with suicide-related risk. By exploring the lived experiences of adolescents previously hospitalized for a suicide-related crisis, as well as their parents, school professionals, and clinical providers, this study complements previous work that has identified a link in school-related experiences with suicide-related risk and protective factors. The primary aim of this qualitative study was to explore multiple perspectives of how school may intersect with suicide-related risk and recovery.

Theoretical Framework

From an ecological perspective, school environment and school experiences may influence both the development of suicidal ideation and the shift from ideation to action. Ecological systems theory posits that a child’s environment transacts with their development across multiple levels (Bronfenbrenner, 1996). Thus, consideration of how school may influence suicide-related risk spans all layers of a student’s ecology: schools may play a role in supporting student identity development (ontosystem), creating safe and inclusive spaces for students to learn and thrive (microsystem), building school-family-community partnerships to support student development (mesosystem), being part of safe communities for schools to actualize supports (macrosystem), and accounting for how social norms that include or exclude youth with diverse identities and mental health needs may shape schools (exosystem; Marraccini, Ingram, et al., 2022).

When considered within the cognitive-behavioral model of adolescent suicide (Spirito et al., 2012), proximal influences of schools (e.g., school values, structures, processes, relationships) can serve as stressors or protective factors of suicide when intersecting with a student’s internal processes (i.e., maladaptive cognition, behavior, and affective responses may lead to suicide risk). Risk for suicide, and the relationship between school and a student’s internal processes influencing risk, are also influenced by other microsystem level influences (e.g., family cohesiveness, community networks). Thus, school experiences and school environment are among many potential contributors to risk that must be considered within the unique context of a student (including both internal and external processes).

Consideration of cultural variation in risk factors and the ways in which they intersect with school norms and values is also critical for understanding school context and risk for suicide (Marraccini, Griffin, et al., 2022; Marraccini, Ingram, et al., 2022). Culture not only influences risk for suicide, but it is also shapes how suicide, associated risk factors, and associated protective factors are defined and expressed (Chu et al., 2010). For example, acculturative stress and racial discrimination are associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviors in racial and ethnic minoritized youth, and collaborative religion and spirituality may play a protective role against it (Goldston et al., 2008). Cultural interpretations and expressions (e.g., acceptability of stressors and suicidality) can influence the development of suicidal thoughts and behaviors (Chu et al., 2010).

A student’s identity, including their gender, sexuality, race, ethnicity, disability, and more, is at the center of a student’s ontosystem. It may be impacted by both proximal and distal stressors unique to ethnic, racial, sexual, and gender minoritized and economically disadvantaged individuals (Meyer, 2003). As outlined by the minority stress model, these may include experienced and expected discrimination and prejudice, which may be internalized and intersect with other risk and protective factors for suicide (Fulginiti et al., 2020; Meyer, 2003). Although originally proposed for understanding health risk in individuals identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, questioning, intersex, two spirit, and queer (LGBTQ+), a rich body of work suggests that these stressors are salient to suicide-related risk across a wide range of identities associated with societal disadvantages (Chu et al., 2010). Thus, a holistic understanding of school context and risk for suicide accounts for the intersectional experiences of multiple disadvantages. Such understanding must take an intersectionality lens, which acknowledges how interlocking systems of privilege, power, and oppression may interact to shape experiences according to a combination of identities (Crenshaw, 1989).

Building from intersectionality theory, along with critical race and disability theories, Disability Critical Race Theory (DisCrit) centers the intersection of the social constructs of race and disability (Sabnis & Bueno Martinez, 2022). Specifically, “DisCrit seeks to understand ways that macrolevel issues of racism and ableism, among other structural discriminatory processes, are enacted in the day-to-day lives of students of color with dis/abilities” (Annamma et al., 2013. p. 8). Because suicide is transdiagnostic – that is, risk for suicide has been found to associate with nearly all major mental health disorders (Schechter & Goldblatt, 2020) – and individuals with suicidal thoughts and behaviors represent a wide range in severity of symptoms, DisCrit helps frame how an understanding of school influences of suicide-related risk must acknowledge how intersecting identities, inclusive of identifying as having a mental health disorder, interact with cultural and contextual variations of suicide risk. For each unique identity, school experiences and norms can relate to development of or protection from suicide-related risk differently. For example, acceptance of LGBTQ+ identity and severity of symptoms related to suicide-related risk may be interpreted differently by school professionals and student families (Marraccini, Griffin, et al., 2022; Marraccini, Ingram, et al., 2022).

School Related Risk and Protective Factors of Suicide

Recent reviews of school-related risk and protective factors of suicidal thoughts and behaviors focused on LGBTQ+ (Marraccini, Ingram, et al., 2022) and ethnic and racial minoritized (Marraccini, Griffin, et al., 2022) students have identified the significance of multiple components of school for understanding suicide-related risk in youth. Key factors may include school relationships (e.g., bullying that can occur in and out of schools, feelings of connectedness to teachers and peers), academic stressors and difficulties, and school processes (e.g., comprehensive suicide prevention programs; inclusive programs and policies that are welcoming to diverse students).

Although most research aimed at understanding school-related risk and protective factors of suicidal thoughts and behaviors has employed quantitative approaches, a rich literature based on qualitative research has explored experiences and perceptions of suicide in adolescents more generally. For example, Grimmond and colleagues (2019) conducted a systematic review of 27 qualitative inquiries focused on understanding youth and young adult suicide attempts, categorizing findings according to (a) triggers and risks leading to suicidality (including peer influences and academic challenges), (b) factors involved in recovery, (c) needs for institutional treatment/prevention strategies (including education in schools and specialized support and education for parents), and (d) beliefs about suicide within the wider culture. In the following sections we expand on quantitative and qualitative research exploring each of these school-specific components (school social supports and school connectedness, social difficulties and bullying, academic stressors and difficulties, and school processes for preventing suicide) as they relate to suicide-related risk in youth.

School Relationships and Connectedness

School connectedness has emerged as a potential protective factor against suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Findings from a 2017 meta-analysis indicated that when students feel connected to their school (by way of teachers and peers), they are approximately half as likely to report past suicidal thoughts or suicide attempts (Marraccini & Brier, 2017). Students feeling connected to their schools also appear less likely to report a suicide attempt in the months following an emergency department visit (King et al., 2019). Moreover, positive student teacher relationships (Marraccini, Resnikoff, et al., 2021) and connectedness to peers (Czyz et al., 2012) can support student recovery following a suicide related crisis.

When findings from quantitative studies are stratified by race, ethnicity, and gender identity, the protective effects of school connectedness are less consistent. Although school connectedness appears to play a protective role among American Indian and Hispanic students, its protective effects appear less consistent among Asian, Black, and LGBTQ+ students (Marraccini, Griffin, et al., 2022; Marraccini, Ingram, et al., 2022). Qualitative findings have largely pointed to peer supports (in and out of schools) as a salient theme for understanding recovery from suicide-related crises among adolescents globally (Bostik & Everall, 2007; Shilubane et al., 2012; Strickland & Cooper, 2011), but have less frequently explored the potential for adults in school to play a supportive role towards prevention and recovery (although the dearth of research focused on Black and African American and LGBTQ+ youth is consistent in qualitative studies).

Bullying and Peer Conflict

Bullying experiences and peer conflict may also confer risk for suicide. Several meta-analyses suggest that students reporting bullying victimization, bullying perpetration, or both, are approximately two to three times more likely to report suicidal thoughts and behaviors as compared to those without a history of bullying experiences or behaviors (Holt et al., 2015; Van Geel et al., 2014). They are also approximately one and a half to two times more likely to report suicidal thoughts and behaviors over time (Van Geel et al., 2022). Bullying appears to serve as a risk-factor for suicidal thoughts and behaviors among most ethnic, racial, sexual, and gender minoritized youth (Marraccini, Griffin, et al., 2022; Marraccini, Resnikoff et al., 2021). Several qualitative inquiries have identified bullying experiences as a perceived contributor to distress or risk for suicide, including Zayas and colleagues’ (2010) study exploring perspectives of Latina youth with a history of suicidal thoughts and behaviors and Matel-Anderson and Bekhet’s (2016) study focused on provider (i.e., nurses) perspectives.

Academic Stress and Pressure

Compared to research focused on school connectedness and bullying experiences, fewer studies have investigated how academic difficulties (and, conversely, academic successes) are associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviors. However, the relationship between academic performance and mental health more generally has been demonstrated in a recent meta-analysis (Bas, 2021), suggesting a bidirectional relationship of academic success and mental health functioning. A few studies have also supported this relationship for suicidal thoughts and behaviors specifically. Higher grades were shown to associate with lower scores on a measure of suicide-related risk (including indicators of depression and suicidal thoughts and behaviors) in a national sample of African American and Asian American students (Whaley & Noel, 2003). In a sample of students in New Mexico, students with plans for postsecondary education were approximately 60% less likely to report having made a suicide attempt compared to those without plans (Hall et al., 2018). Qualitative studies have also illustrated the ways in which academics may play a role in recovery from suicide-related crises, including concerns about academic pressure, academic difficulties, and overly focusing on academics (Gulbas & Zayas, 2015; Gulbas et al., 2015; Keyvanara & Haghshenas, 2011; Shilubane et al., 2014).

School Processes: Comprehensive Suicide Prevention Programs

Beyond the influence of school experiences and environments, schools are increasingly called upon to deliver comprehensive suicide prevention programs. Schools are ethically, and, in more than half of the states in the US, legally, required to provide training for suicide prevention (American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, 2020). The most effective suicide prevention programs are postulated to be those that (a) include a mechanism for identifying students at risk; (b) are embedded across all levels of the multitiered systems of support (including general education curriculum); (c) employ a gatekeeping approach wherein school faculty, staff, and students are aware of referral processes; and (d) efficiently connect youth with risk to suicide to school and community services (King et al., 2018; Miller & Mazza, 2018; Singer et al., 2019).

Despite growing interest in such programs, indicators of efficacy are limited due to both implementation and evaluation challenges, with research tending to rely on intermediate indicators such as knowledge and attitudes related to help-seeking and suicide, with less understanding about program effects on behavior (e.g., reducing risk for suicide; Klimes-Dougan et al., 2013; Singer et al., 2019). Still, several programs that can be considered within a multitiered systems of support (MTSS) framework have emerged as best practice. These may include (a) promoting protective factors and preventing risk factors for suicide and screening for suicide-related risk at the universal (tier 1) level, (b) identifying and intervening in suicide-related risk and enacting crisis protocols at the selected (tier 2) level, and (c) delivering intensive supports and interventions for youth identified with suicide-related risk, as well as enacting postvention interventions following death due to suicide at the indicated (tier 3) level (Singer et al., 2019). Recent findings have also prioritized “upstream” approaches that aim to address risk factors for suicide prior to the onset of risk for suicide (Singer et al., 2019; Wyman, 2014) as promising universal prevention associated with lower likelihood for suicidal ideation and attempts (Wilcox et al., 2008).

Several qualitative studies that involve community samples of adolescents and care providers (Coggan et al., 1997; Schwartz et al., 2010), as well as samples of youth with peers who had attempted or died of suicide (Shilubane et al., 2014), have identified the need for increased access to services and resources dedicated to suicide prevention in schools. Yet, there may be a chasm between family and school professional perspectives regarding standard procedures for risk assessment. Families have voiced concerns about assessments feeling intrusive and disciplinary, but professionals have shared their appreciation for the structured nature of standardized protocols (Kodish et al., 2020). School professionals delivering school-based suicide prevention programs have also described the difficulty in engaging in dialogue with students when expressions of suicide emerge (White & Morris, 2010).

Such findings align to those reported in a qualitative analysis of 22 quantitative and 30 qualitative datasets addressing barriers and facilitators to adolescent help seeking for mental health care, the majority of which took place in school settings (Radez et al., 2021). Radez and colleagues described barriers to help seeking in and out of schools to include social (e.g., stigma) and therapeutic relationships (e.g., confidentiality concerns), as well as personal factors (e.g., limited knowledge) and structural barriers (e.g., logistical, financial). Thus, even with dedicated resources and interventions addressing suicide prevention, there are additional structural, systemic, and interpersonal obstacles to accessing mental health care in schools.

The Present Study

Risk for suicide is complex and stems from a combination of biological, environmental, and psychological risk factors. Although research to date suggests that there are multiple ways in which schools can help to prevent suicide, the majority of studies have used quantitative methods to identify general predictors or have explored qualitative perceptions of risk more generally, without focusing explicitly on school context. In sum, this work has yet to elucidate the mechanisms or ways in which these school specific risk and protective factors may relate to suicidal thoughts and behaviors. The present study aimed to deepen understanding of school-related risk and protective factors of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among youth with suicide-related crises. Specifically, we aimed to address the following research question: How do adolescents with a history of suicide-related crises, their parents, school professionals, and hospital professionals describe school-related influences of suicidal thoughts and behaviors and mental health?

Material and Method

This qualitative research is part of a larger mixed-methods study that is developing school re-entry guidelines for adolescents hospitalized for suicidal thoughts and behaviors. The larger study involved three phases of data collection, including (a) a survey of school professionals across one state (n = 133); (b) in-depth interviews with adolescents previously hospitalized for suicidal thoughts and behaviors (n=19), their parents (n = 19), school professionals (n = 19), and hospital professionals (n = 7); and (c) iterative development of school re-entry guidelines based on feedback from representative participants completing focus group and one-on-one interviews. In our previous analyses addressing data as part of Phases 1 and 2, we focused on adolescent and school professional descriptions and experiences related to school reintegration following psychiatric hospitalization and informing the types of supports adolescents may require as they return to school (see Marraccini & Pittleman, 2022; Marraccini, Pittleman, et al., 2022). The present study also focused on qualitative data collected from the interviews conducted during Phase 2, but explored adolescent, parent, school professional, and hospital professional perceptions of school influences of suicide-related risk more generally (as opposed to focusing on school reintegration only).

Participants

Participants included four cohorts consisting of adolescent (n = 19) and parent (n = 19) dyads, school professionals (n = 19), and hospital professionals (n = 7). Each cohort was selected to enhance understanding of adolescent school experiences. We focused on adolescents because they are the individuals interfacing with schools as students experiencing suicidal thoughts and behaviors. We included parents because they are often a primary caregiver of adolescents and may have an indirect understanding of school experiences by way of their adolescent and direct experiences with school by advocating for their adolescent and interacting with school through meetings and events. We included school professionals because they can be involved in supporting adolescents with suicidal thoughts and behaviors and may directly observe adolescent experiences in schools. Finally, we included hospital professionals, because they deliver acute treatment to adolescents that involves understanding and assessing suicide-related risk and protective factors, drivers, and triggers; and because they integrate school assessments into treatment decision making.

Final sample sizes for each cohort were based on assessment of data saturation by monitoring debrief summaries following interview completion with consideration of representativeness within each cohort. Specific representativeness considerations included (a) severity of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among adolescent and parent dyad participants, (b) school demographic characteristics among school professional participants, and (c) professional roles among school and hospital professional participations. All participants completed consent and/or assent procedures prior to participating in the study and were informed of ethical protections for their participation (i.e., a certificate of confidentiality provided by National Institute of Mental Health). As compensation for their time, adolescent participants received $30, parent participants received $25, and school and hospital professional participants received $20.

Adolescent/Parent Dyads

Adolescent and parent participants were identified from medical records of adolescent patients with a hospital billing code related to suicidal thoughts and behaviors within a large hospital located in the southeast United States. Adolescent eligibility criteria were (a) hospitalization for suicidal thoughts and behaviors at a psychiatric inpatient facility, (b) ages 13–18 years (Mage = 15.7, SD = 1.3), (c) return to school following hospitalization, and (d) ability to speak, read, and understand English sufficiently to complete study procedures. One legal guardian of each participating adolescent was eligible to participate.

A total of 1399 records were extracted at three different times over a 16-month window. After removing records that indicated patients were not admitted to an inpatient hospital (n = 1198; e.g., they were seen in the emergency department or a medical unit only), a total of 231 records were screened for eligibility on an ongoing basis. Records were excluded if they were identified as duplicates (n = 10), identified as requiring interpreter services during hospital interactions (n = 11), or no longer met eligibility criteria (n = 87). Note that because the records were static and our recruitment was ongoing, records in the latter category primarily reflected those that were no longer eligible to participate based on date of discharge or age at the time of recruitment.

In total, we mailed 123 “opt-out” letters to families, following up by phone to describe study procedures. A total of 19 (15.4%) adolescent/parent dyads (n = 17 mothers and n = 2 fathers; ages 29–56 years, Mage = 45.7, SD = 7.7) participated in the study and completed consent and assent procedures in-person or virtually (depending on safety during the pandemic). The remaining families did not participate because they (a) indicated that they were not interested in participating (n = 22, 17.9%), (b) did not return our phone calls or no longer had the same contact information as indicated in their medical records (n = 60, 48.8%), or (c) were not eligible to participate based on eligibility criteria (n = 19 [15.4%], of whom three [2.4%] were ineligible because they were not proficient in English to complete study procedures).

School Professionals

We also conducted in-depth interviews with a purposive sample of school professionals (n = 19) participating in Phase 1 of the study, in which we recruited school professionals providing school-based mental health services across one southeastern state to complete surveys about school reintegration (n = 133). School professional participants, as part of Phase 1, were recruited within 35 participating school districts using an email invitation. When completing the consent process during Phase 1, school professionals indicated their interest in completing qualitative interviews and researchers followed up with interested participants by email and phone. The final sample of school professional participants as part of Phase 2 was selected to represent individuals working in a range of school-based roles in different districts across the state. School professional participants included school psychologists (n = 4), school counselors (n = 4), social workers (n = 4), nurses (n = 2), one principal, one special education teacher, and one professional who identified as “other.”

Hospital Professionals

Hospital professionals were recruited by way of email invitations to one psychiatric inpatient facility in the same state. Any hospital professionals working in the facility supporting adolescents hospitalized for suicide-related crises at the facility were eligible. Hospital professionals included two individuals working in the hospital’s school, with the remaining participants working in treatment as occupational therapists, recreational therapists, or attending physicians. Note that although the hospital professionals worked in a hospital or the hospital’s school setting and did not directly observe adolescents in their community school environments, they described a range of relevant experiences. These included speaking with adolescents about school experiences, planning for adolescent return to school settings, and integrating school-based reports into their treatment planning.

Procedure

Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board. Following parent permission for adolescents under the age of 18 years, adolescents completed informed assent procedures. All adult participants (i.e., adult adolescents, parents, school professionals, and hospital professionals) completed informed consent prior to participation. Following consent and assent procedures, all participants completed interviews; adolescent, parent, and school professional participants also completed a brief set of questionnaires that varied according to cohort.

Instrumentation

Self-Report Measures and Clinical Interviews

Demographic data were collected using a self-report survey for adolescent, parent, and school professional participants and by using verbal prompts for hospital professionals. Although specific questions varied by cohort (i.e., adolescents and parents were asked about household income, attendance, grades, and special education services; school and hospital professionals were asked about their profession and number of years working in the profession), all participants were asked about their race, ethnicity, and gender. The questions asking about ethnicity and race adhered to a two-question format, addressing ethnicity and race separately.1 To address ethnicity, participants were asked: “Are you Hispanic or Latinx?” Response options on the survey for race included American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, White, or Other. If adolescent and parent participants selected “Other” an open-ended text box allowed them to self-describe their race. This option to self-describe race was not included for school or hospital professional participants.

To assess gender, hospital and school professional participants were asked “Which of the following describes your gender?” Response options included male, female, or other. The questions asking adolescent and parent participants about their gender were selected based on recommendations from the Gender Identity in U.S. Surveillance (GenIUSS) group for identifying transgender and other gender minoritized individuals (The GenIUSS Group, 2014) and youth specifically (Greytak et al., 2014). Accordingly, we used a two-step procedure wherein we first asked participants to identify sex as described on their birth certificate and next asked participants to select or identify their gender. Parent participants were asked the question, “How do you describe yourself? (check one),” and response options included female, male, transgender, and I do not identify as female, male, or transgender. Adolescents were provided with the following prompt: “When a person’s sex and gender do not match, they might think of themselves as transgender. Sex is what a person is born with. Gender is how a person feels. What one response best describes you?” Response options included I identify as a boy or man, I identify as a girl or woman, I identify in some other way, I do not know what this question is asking, or I do not know if I am transgender. Adolescent and parent participants also identified their sexual orientation by selecting from the following response options: Heterosexual or straight, bisexual, gay or lesbian. They identified their sexual attraction to others by selecting from only attracted to females, mostly attracted to females, equally attracted to females and males, mostly attracted to males, only attracted to males, or not sure.

Although the present study was focused on qualitative interviews and demographic information collected from participants, additional measures completed by participants included the School Reintegration Survey and the School and Community Mental Health Services Questionnaire (Marraccini et al., 2019; Marraccini, Vanderburg, et al., 2022; completed by school professionals), the Authoritative School Climate Survey (Konald & Cornell, 2015; completed by adolescents, parents, and school professionals), and the Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview (Nock et al., 2007; completed by adolescents).

In-Depth Interviews

Masters and doctoral-level interviewers completed a 2-day qualitative training addressing qualitative in-depth interview approaches, the interview protocol, and applied thematic analysis. The training was provided by a senior researcher with expertise in qualitative methods for applied health behaviors and other patient-oriented research. The senior researcher also provided ongoing consultation throughout the project.

The semi structured qualitative interview guide addressed four main areas: (a) school experiences prior to hospitalization, (b) school experiences and considerations during hospitalization, (c) school re-entry experiences and processes, and (d) information sharing between hospitals and schools. The interview guide allowed for adaptations and flexibility based on individual differences across interview and included sample questions to address each area. For example, a sample interview question particularly relevant to the present study aims that was included in the first section of the interview (school experiences prior to hospitalization) asked “How do you think your [or your adolescent’s] school may have influenced suicidal thoughts and behaviors?” (directed to adolescents and parents), and “How do you think school may influence students with suicidal thoughts and behaviors?” (directed to school and hospital professionals). Because each topic could be addressed in any order to follow the logical flow of the interview, and questions were informed by participant responses, specific questions addressed to individual participants varied according to individual interviews.

The majority (18 of 19) of one-on-one interviews with adolescent and parent participants were conducted in-person in private interview rooms located within a teaching laboratory and clinic. The final adolescent/parent interview was conducted virtually due to safety concerns during the pandemic. A total of four interviews conducted with school professionals were conducted in-person (e.g., at the participant’s workplace), with the remaining interviews with both school (n = 15) and hospital (n = 7) professionals conducted virtually.

Following completion of interviews, interviewers completed debrief summaries to provide a summary of the interview and monitor data saturation. Debrief summaries described tone and demeanor of the participant, a summary of responses for each segment of the interview, conceptual lessons learned, notes about the interview set up, interruptions or problems during the interview, and areas for follow-up or change. Interviews ranged in length from 33 to 120 min for all participants (M = 68). By cohort, interviews ranged from 42 to 90 min for adolescents (M = 64), 44 to 120 minutes for parents (M = 76), 33 to 101 minutes for school professionals (M = 65), and 45 to 94 minutes for hospital professionals (M = 63).

Data Analysis

Qualitative interviews were audio recorded, transcribed, reviewed for accuracy, and redacted of identifying information. Final interviews were entered into NVivo and Nvivo 12 Pro qualitative data analysis software (depending on the date of analysis), which is a qualitative software tool that helps organize and manage qualitative data into analytic themes (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2018, 2020).

We conducted applied thematic analysis on transcribed interviews. Applied thematic analysis is a systematic and inductive approach that draws from multiple theoretical foundations, such as basic inductive thematic analysis, grounded theory, and phenomenology (Guest et al., 2012). Although coding structures were developed separately for each cohort, we first developed the adolescent coding structure and used it as the basis for developing the coding structure for other cohorts. Initially based on the interview agenda, we iteratively refined and developed the adolescent coding structure to include emergent themes throughout the coding process, following a similar process for other cohorts. We prioritized the adolescent coding structure as a guide for other structures because they represent the population of focus. For the present study, we focused on an emergent code related to the study’s aim, which addresses perceptions of school experiences in relation to adolescent functioning. The first author further reduced the data to identify themes related to perceptions of school influences of mental health, discussing them with the second author throughout the process. Note that there are additional codes outside the scope of the present study (e.g., focused on school reintegration procedures) that have been summarized elsewhere (see Marraccini & Pittleman, 2022; Marraccini, Pittleman, et al., 2022) and are currently under analysis to address other research questions.

Trustworthiness

We enhanced trustworthiness in our data analysis by addressing issues related to credibility, transparency, and transferability. Interview procedures involved a form of member checking, wherein the researchers regularly summarized participant responses to confirm understanding. To ensure credibility, two trained researchers read transcripts and identified emergent codes separately, and then met regularly to come to agreement about the coding structure. An “audit trail” identifying changes to the coding structure was maintained to ensure transparency. A total of 53% (10 of 19) of adolescent transcripts were double coded (i.e., two independent researchers coded interviews separately), with assessment of internal reliability (percent agreement above .80) assessed during the final stages of coding. To prevent drift from occurring during independent coding of the final nine transcripts, wherein the researcher may begin to apply codes inconsistently over time, two of the nine transcripts were double coded. All other transcriptions (collected from parents, school professionals, and hospital professionals) were double coded to ensure credibility. In the case of disagreements, researchers engaged in discussions to come to consensus, documenting reasonings for agreement. To support transferability of findings, illustrative quotes were selected to represent common themes.

Researcher Positionality

We considered the background of each researcher, including privilege and underrepresented statuses conferred by our unique racial, ethnic, sexual, and gender identities, when interpreting study findings and included a diverse group of researchers to help manage the influence of our prior experiences and perspectives. The first author is the principal investigator of the study and has focused on research aimed at supporting adolescents with suicidal thoughts and behaviors in the context of school settings. Trained as a school psychologist and licensed as a psychologist, she is committed to identifying ways for schools to play a supportive role in recovery from suicide-related crises. Accordingly, the first author applied an ecological lens when engaged in this work, remaining open to the potential for schools to play a complex role in adolescent recovery (having both positive and negative influences on recovery).

The second, third, and fifth authors are doctoral level graduate students, each with experiences working in schools. Collectively, they have worked with a wide age range of both neurotypical and neurodiverse students from varied socioeconomic, racial, and cultural backgrounds across school-based and/or clinical settings. They also applied an ecological lens focused on societal, environmental, cultural, familial, and internal factors to both clinical conceptualizations and research.

Finally, the fourth and sixth authors are psychiatrists with fellowship training in child and adolescent psychiatry. They both work clinically with children and adolescents with suicidal thoughts and behaviors, in inpatient and outpatient settings. Additionally, the sixth author conducts independent research examining a task-shifting model of providing mental health care in schools in resource-limited areas. The fourth and sixth authors have applied a biopsychosocial lens to this work, taking into consideration biological underpinnings of mental health, psychological contributions to mental health, and social and environmental influences on mental health.

Results

Results are presented in three sections. First, we describe descriptive data identifying participant demographic characteristics. Second, we describe themes related to perceptions of how school experiences can positively or negatively relate to mental health. Third, an emergent theme related to the complexity of suicide-related risk and how school may intersect with other environmental, biological, and psychological risk and protective factors, is presented. Sections are organized according to subthemes and cohorts are described together.

Participant Characteristics

Demographic Characteristics

Demographic characteristics for the four participant cohorts, including gender, race, and ethnicity, are shown in Table 1. Only adolescent and parent participants were asked questions about sex and gender separately, of whom only adolescents identified a gender inconsistent with sex identified on their birth certificate. More specifically, most adolescents selected their gender to be girl or boy, aligning to the sex identified on their birth certificate and were considered cisgender (n = 16); two adolescents identified in some other way than boy, man, girl, or woman (n = 2); and one indicated they did not know if they were transgender (n = 1). Regarding race, adolescents were White (n = 11), Asian American and White (n = 4), Black or African American (n = 2), or other (n= 2). Four adolescents identified their ethnicity as Latinx or Hispanic.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants by Cohort

| Adolescents | Parents | School Professionals | Hospital Professionals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Gender† | ||||

| Girl, woman, or female | 14 (73.7) | 17 (89.5) | 15 (78.9) | 7 (100) |

| Boy, man, or male | 2 (11.8) | 2 (11.8) | 4 (21.1) | 0 |

| Something other than boy, man, girl, or woman | 2 (11.8) | |||

| Do not know if transgender | 1 (5.3) | |||

| Race | ||||

| American Indian/Alaska Native†† | 0 | 1 (5.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Asian American†† | 4 (21.0) | 1 (5.3) | 0 | 1 (14.3) |

| Black or African American | 2 (10.5) | 2 (10.5) | 2 (10.5) | 1 (14.3) |

| White | 11 (57.9) | 14 (73.7) | 15 (79.0) | 5 (71.4) |

| Other††† | 2 (10.5) | 1 (5.3) | 1 (5.3) | 0 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Latinx/Hispanic | 4 (21.0) | 2 (10.5) | 1 (5.3) | 1 (14.3) |

| Non-Latinx/Hispanic | 13 (79.0) | 17 (89.5) | 17 (89.5) | 6 (85.7) |

Note.

Response options for gender varied according to participant cohort

All adolescents and parents identifying as American Indian/Alaska Native or Asian American also identified as White

One adolescent selecting “other” self-described their race as “Latino” and the other adolescent did not describe their race; the parent identifying as “other” self-described their race as Brazilian; the school professional identifying as “other” did not have an option to self-describe their race. Numbers represent frequency with percent shown in parentheses. Total percent may be less than 100 in cases where participants chose not to answer.

Fifteen parents identified as women and four identified as men. Parents were White (n = 14), Black or African American (n = 2), American Indian/Alaska Native and White (n = 1), Asian American and White (n = 1), or other (n = 1). Two parents identified their ethnicity as Latinx or Hispanic. Fifteen school professionals identified as female and four identified as male. School professionals were White (n = 15), Black or African American (n = 2), or “other” (n = 1), with one identifying as Latinx or Hispanic. Finally, all hospital professionals were female (n = 7), identifying their race as White (n = 5), Asian American (n = 1), or Black or African American (n = 1). One hospital professional identified their ethnicity as Latinx or Hispanic.

Adolescent and Parent Characteristics

Only adolescents and parents were asked about sexual orientation and attraction. Of the adolescent participants answering the question (n = 18), seven adolescents (38.9%) identified as heterosexual or straight, two (11.1%) identified as gay or lesbian, and nine (50.0%) identified as bisexual. When asked about sexual attraction to other people, only four adolescents (21.0%) indicated they were only attracted to the other sex. The remaining adolescents indicated they were mostly attracted to the other or same sex (n = 12, 63.2%), equally attracted to females and males (n = 1, 5.3%), or not sure about their attraction (n = 1, 5.3%). Most parents (n = 18, 95%) identified as heterosexual, and one parent (5%) identified as bisexual. Most also indicated they were only attracted to the other sex (n = 15, 83%), whereas two (10.5%) indicated they were mostly attracted to the other sex and one (5.3%) indicated they were equally attracted to females and males. Taking both gender and sexuality in account, 14 adolescents (70%) and one parent (5%) identified in a way that can be considered under the umbrella identity of LGBTQ+.

All adolescents attended public school and 26% of parents (n = 5) reported that their child received special education or remedial services in school. Adolescents described receiving “Mostly A’s” (n = 5, 26%), “Mostly A’s and B’s” (n = 8, 42%), “Mostly B’s” (n = 1, 5%), “Mostly B’s and C’s” (n = 2, 11%) and “Mostly C’s” (n = 3, 16%). Annual household income was reported by 16 parent participants, ranging from $0 to $500,000 (M = $115,703; Mdn = $105,500).

Perceptions of Positive and Negative School Experiences

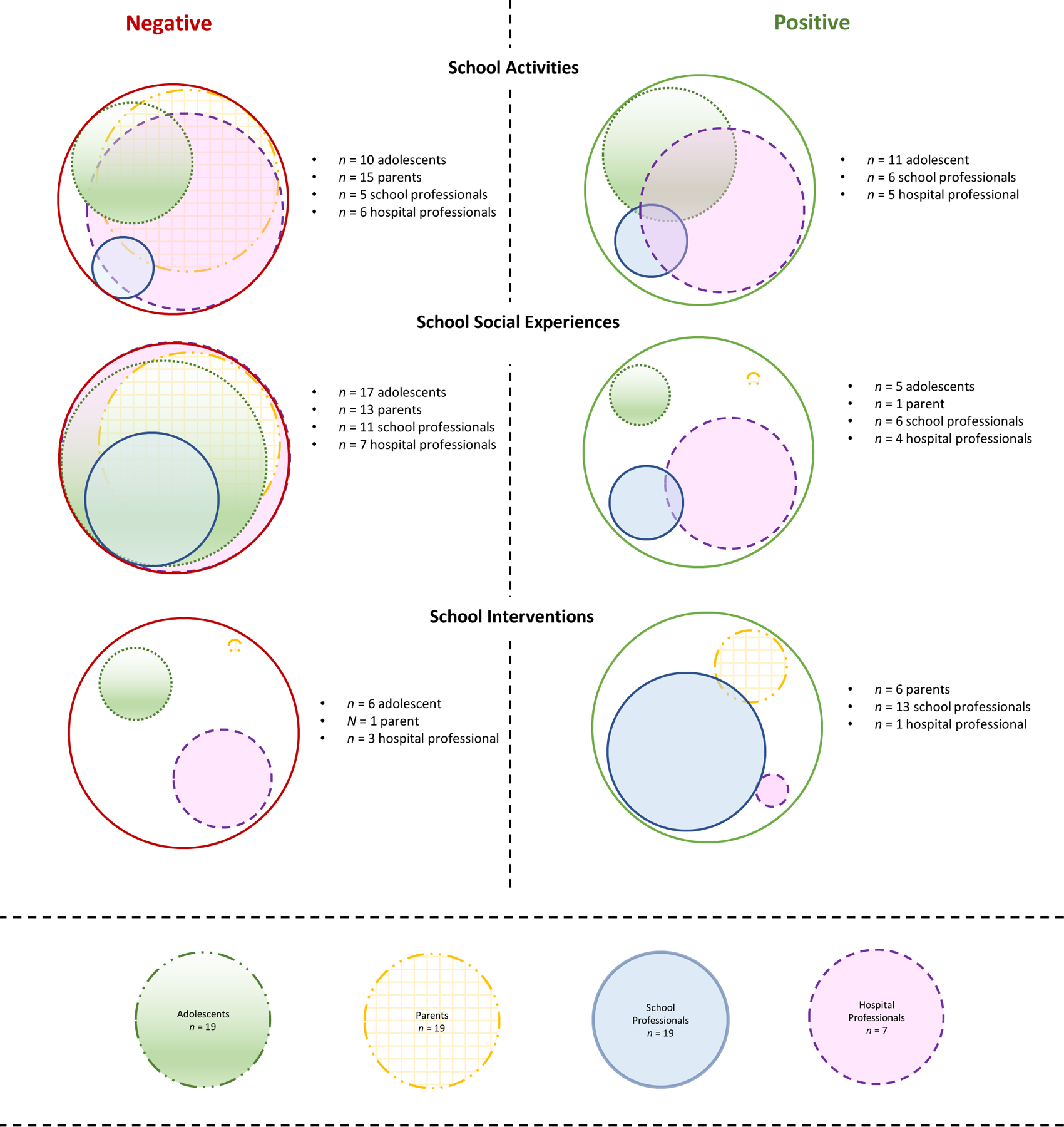

Figure 1 displays common themes related to participant views of how school experiences may positively or negatively relate to psychological functioning in adolescents with suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Themes included (1) participation in school activities, (2) school social experiences, and (3) school interventions. For each theme, we first present descriptions of how school experiences may positively relate to mental health and next present descriptions of how school experiences may negatively relate to mental health. Illustrative quotes are presented to enhance understanding of each theme and are displayed in Supplementary Tables 1–3.

Figure 1.

School Experiences Perceived to Negatively and Positively Influence Mental Health

Note. Size of circle indicates proportion of participants within cohort describing an experience or perspective that aligns with each theme.

School Activities

Positive Perceptions: Engagement and Distraction.

Eleven adolescents (58%), six school professionals (32%), and five hospital professionals (71%) described how engagement in school experiences (e.g., academics, extracurricular activities) and the consistent routine and structure provided by school can serve as a form of coping, connection, or distraction for adolescents. School professionals indicated the significance of school as a safe place that can also serve as an escape from difficult home experiences, and individuals across cohorts described how they believed engagement in school activities can have a positive influence on adolescent health. A school counselor provided an example of one student who, despite having a difficult home life, made school “her safe place” by engaging in Future Farmers of America activities “where she feels important and a leader.”

Adolescents (n = 9, 47%) also identified the potential for school to serve as a form of distraction from other pain and stressors. For example, this 17-year-old girl explained how school helped served as a form of distraction: “Distraction. Just like, ‘Okay. I’m not gonna be in the house being depressed and doing stupid sh*t all day. Great.’” Another 16-year-old girl explained the push and pull they felt from feeling stressed in school while also benefiting from it as a distraction:

Cause I was like, oh my gosh, I’m missing school. Why am I missing school, like. Oh, it was, like, just—sometimes I had to break myself out of it. You have scars all over your arm. Like, you need to not think about school. But then, I don’t know. It was also good, though, for a distraction sometimes to just make me, like—I’d tell myself, like, no I need to do this homework cause I need to, like, think about something in the future. Like, I’m gonna turn this assignment in. Like, have that.

For some adolescents, distraction was the only aspect of school they felt had a positive effect on them.

Negative Perceptions: Academic and Performance Pressure.

Perceptions of how academic pressure, as well as pressure to perform well in other areas, may have a negative influence on mental health emerged as a common theme across cohorts (adolescents, n = 10 [53%]; parents, n = 15 [79%]; school professionals, n = 5 [26%]; hospital professionals, n = 6 [86%]). Several participants (two adolescents [10%], two parents [10%], and two hospital professionals [29%]) described how the combination of academic pressure and being a “perfectionist” or high achiever can be particularly challenging. For example, this 16-year-old girl explained:

…I was putting the pressure on myself that I had to do every assignment perfectly, get perfect grades, um, everything like that. And, of course, there’s benefits to being a perfectionist in school because it drives me to do well but—um, it really took a toll on my mental health. And I think that it was kind of that attitude about the [advanced] program that was hard because it was kind of like you go, go, go. There’s no slack. Like, everyone, the teachers-it’s not just solely the teachers, but the students as well. Like, it’s kinda the environment, that everyone puts the school before their mental health.

A related issue, in which adolescents may compare their performance to their peers, was described by three parents. A father explained how attending a school with high-performing students may have influenced their adolescent’s mental health:

I think generalized anxiety about performance. There’s all the usual cultural sh*t of body image and the whole Snapchat, Instagram culture of comparing yourself to—and she’s going to a school with a lot of really high-performing, amazing people. If you’re feeling like your life’s not going well, that can really wear you down.

Others (two adolescents) described how academic pressure can exacerbate additional risk factors for them, for example not getting enough sleep or spending too little time with friends. One 16-year-old adolescent girl simply described how academic stress minimized their fear of death: “Well, I guess what I’m trying to say is like, school, because of the stress load from school, it made, like, thinking of suicide not as scary of a thing.”

Pressure to succeed was not limited to academics; for example, one adolescent noted the pressure they faced in sports. Indeed, a hospital professional described how for some adolescents, doing less in school may be one of the solutions for recovery:

I think each kid probably is different. I think sometimes things that have been helpful have been really specific things…some of that could be like, “Okay, you’re in ROTC [Junior Reserve Office Training Corps program], and you play on the soccer team, and you do this, and you do that. Which of those roles do you—you’re telling me that you don’t have enough time. Which of those roles are most fulfilling to you? What benefits are you getting from those activities? How can we make sure you’re still getting those benefits but you still have enough time to care of yourself?”

Finally, when describing how schools may influence suicidal thoughts and behaviors, a school psychologist described how school-related pressures may intersect with student backgrounds, including economic privilege, to influence mental health and suicide-related risk. They described how patterns of school factors contributing to mental health may differ across demographic groups, with college and advanced coursework pressure more salient to some, but economic constraints more salient to others:

I think it really is across all of our demographic groups. I see some differences. I see that the kids that are taking those AP classes and they really are pushed to college and stuff, it’s more the anxiety, it’s more the stress and the anxiety. Some of our other kids, our Hispanic kids, there’s been a fear of, “Have you been coming to school over recent years?” Then when you start getting on them about attendance because they’re trying to work a job on top of coming to school, you see them dropping out in this homeroom.

School Social Experiences

Positive Perceptions: School Relationships.

Positive in-school relationships with adults and peers were described as supporting adolescent mental health by a handful of adolescents (n = 5 [26%]), school professionals (n = 6 [32%]), and hospital professionals (n = 4 [57%]), as well as one parent (5%). Positive in-school adult relationships were especially emphasized by school professionals. A school psychologist described how teachers shared information about students of concern simply to provide emotional support to them:

They were aware of some really significant depression, anxiety, and internalizing concerns. They had just talked about how they tracked the student on their own. From semester to semester, they made sure they talked about this student and her background to the next set of teachers. Said, “Keep an eye out, and check in with this student a little bit more. Talk to her and see what she needs.”

A more general sense of connectedness to school was also expressed by hospital professionals. This hospital school professional explained:

I’ve been happily surprised to hear that it seems like most students feel like there is someone in the school that they can talk to. It can be different people, but I do feel like overall, maybe 80 % or something of the students that I actually ask—I don’t always ask that to every kid. If I do happen to ask them, they feel like there is someone that they can identify as someone that they’re comfortable talking to at their school.

Adolescents also expressed gratitude for adult relationships, as this 14-year-old girl described:

But my SRO [school resource officer], you know, like, if I looked sad or mad or something like that, you know, she always knew what it was. And she would always, you know, like, talk to me, like take me up to her office. You know, she’d make me laugh somehow. And so did my counselor. So during that time, you know, I felt safe going to school, you know? I felt good, you know? I was like, “You know, even though this is happening, you know, I still got these people to talk to.”

In addition to adult relationships, a few adolescents reported that they appreciated having school as a place they could connect with peers. A 15-year-old girl expressed the positives of school this way: “It was the only way I could really see my friends.”

Negative Perceptions: Difficult Social Interactions.

Difficult social interactions were identified as a perceived stressor for adolescents with suicide-related risk by most adolescents (n = 17 [90%]), parents (n = 15 [79%]), school professionals (n = 11 [58%]), and hospital professionals (n = 7 [100%]). Because of the breadth of this theme, we present findings related to difficult social interactions in separate categories that include (a) challenging peer relationships or feelings of social isolation, (b) concerns about large numbers of students in school, (c) bullying and harassment experiences, and (d) difficult school adult-student relationships. As noted by this 15-year-old girl, however, social difficulties across these categories can overlap to make students feel isolated:

I think that being in school, it made me feel more isolated. That really intensified my suicidal thoughts where I was like, nobody likes you. You’re weird. You’re awkward. That made things harder. How little teachers seemed to care about you. It’d be like, this is their job, is to help develop students and care for them. The teachers that I had that actually did that made me realize how little they—you know what I’m sayin’? I don’t know how to describe it.

Challenges with Peers.

Ongoing challenges with peers in school were identified by several participants across all cohorts (8 [42%] adolescents, 9 [47%] parents, 6 [32%] school professionals, and 4 [57%] hospital professionals). Participants described experiences of social isolation and peer comparisons (e.g., academics, financial), leading to feelings of inadequacy. A special education teacher stated “That kid who is perpetually, always 100% alone, who is shunned when he or she tries to join in so they don’t even bother anymore, that’s a huge problem.” The special education teacher explained how for some kids, not feeling like they fit into the group leads to feelings of alienation, and for others, issues related to hygiene (because “they don’t want to take a shower” or their “moms had another boyfriend over last night, and [they’re] afraid to go in the bathroom”) can lead to other students not wanting to be around them.

One adolescent-mother dyad noted the feeling of disconnect among members of the school. For example, the mother described the psychosocial “culture” or climate of school as uncaring compared to that of their home:

Her struggles were in the school level. Her struggles were the overwhelming amount of children, older children, girls that she couldn’t relate to, the culture. She came from one culture that was safe, open, holistic, caring, everybody knew everybody’s name, blah, blah, blah to a culture of nobody cares about you at all.

Another parent and adolescent (dyad) each described the exhaustion the adolescent felt from having to pretend that everything was okay with friends and teachers, when it really was not.

Still, one hospital school professional explained that when school is described as a stressor or trigger in a patient’s chart (which they review to identify interests and dislikes related to school to better engage them as a learner), it was rarely because of “peer relationships,” but more often because “they’re not doing well in school, and that causes a lot of stress.” As noted by a hospital recreational therapist, the significance of social (and all) stressors varies across patients.

School professionals also identified the intersection of peer difficulties with social media. A school counselor explained:

Kids and adults, for that matter, society and special social media has created this image of what we should be like. When kids are coming to school, and they’re comparing themselves against other people, a lotta times we think somebody else has it all together when they really don’t. I think just comparing, and why can’t I be as smart as her? Why can’t I be as pretty as her? Why can’t I drive a car like she does? I think that creates in their mind what their life is supposed to be like and where they are versus where they think they should be. I think coming to school makes that more prominent in their mind of the differences.

In addition, two school professionals and one parent noted how careful they had to be to contain social contagion, where kids may reinforce each other’s negative coping responses.

Large Numbers of Students.

Five adolescents (26%), five parents (26%), four school professionals (21%), and two hospital professionals (29%) also described how being with a large group of people (e.g., in classrooms, in crowded hallways) was something that could be challenging more generally and difficult to avoid in school. Put simply by this adolescent, “…there’s a lot of people, and I get really anxious when there’s a lot of people.” A mother described it in more detail:

But it’s very overwhelming. It’s just too crowded. It is massive people there, and just… to changing classes, it’s very anxiety-inducing for her. I mean, school is, but she has to go. It’s her biggest trigger is her high school. That’s it. It sums it up right there.

In some cases, these stressors appeared to overlap with student perceptions of the school’s psychosocial support. For example, this 16-year-old girl described it this way:

Anxiety was really bad at [my school] because when that bell rings, your anxiety is like whoo ‘cause you have to run out the class. There’s a horde of people who just push you on—if you stop, they’ll push you to the ground. … Nobody stops when they see that. You just kind of feel like, oh, thanks. I guess I’m just a piece of garbage. They don’t even give you a second glance. They don’t care.

Bullying and Harassment.

Victimization and bystander experiences to incidents of bullying, rumors, and harassment were described by six adolescents (32%), five parents (26%), four school professionals (21%), and six hospital professionals (86%). This 14-year-old girl explained how they felt bullying experiences and rumors contributed to their suicidal thoughts and behaviors:

The bullying was not too bad, but it was bad enough to kind of make me very, very just tired of life and just—I just didn’t want to be here anymore ‘cause I just—I was just so tired of the BS and all the lies and stuff like that. …I think maybe it was a little bit of a contributor to what happened, but I don’t think it was necessarily a big reason.

A 15-year-old girl described how sexual comments in school could be upsetting: “Cause I’ll be havin’ a good day, and I’ll hear something disgusting and gross about somebody else’s—what somebody else would like to violate about someone else’s body.” Still another described the challenge they faced in seeing their perpetrator at school.

A hospital professional described how mental health issues such as “low self-esteem, not liking themselves, social anxiety, rumination, all those sorts of things” can be “wrapped up in” bullying. Note, however, that one hospital professional and one school professional explained that bullying may be relevant in some cases, but that it is not talked about by patients at a frequency that matches how media portrays the issue. Another hospital professional described that although patients may describe their experience as bullying, oftentimes, it may be more aligned to feelings of social isolation:

I would say also the other thing that came to mind is that sometimes, we do have kids who say they’re bullied, but when we ask more, it sounds like what they describe does not involve bullying behavior. It’s more of loneliness at school and then feeling isolated and describing that as being bullied, when in reality, it’s really more poor social skills, lack of peer relationships, which is sad. It’s just not the same as what we call bullying.

Relationships with School Adults.

Finally, tension experienced in relation to negative adult relationships or simply having too few adult relationships was described by seven adolescents (37%), three parents (16%), and four school professionals (21%) as a stressor. Adolescents identified specific teachers they found to be “triggering”, with several explaining that they felt unwelcome by counselors when seeking help. A 17-year-old girl described reaching out to counselors for help and being told “All right. Cool. Go to class.”

Parents also described the difficulties their adolescents faced from negative interactions with teachers and school professionals, with one describing an incident of their adolescent being picked on by a teacher. Although school professionals largely described positive student-adult relationships (detailed in the previous section), some also noted the difficulties students faced when they lacked close connections to school adults. A school psychologist explained, “I think that not having those relationships and not taking the time to form those relationships with kids is detrimental.” Another school psychologist noted how the shift from having school connections while in high school, to being disconnected following high school graduation, can exacerbate isolation, with a specific example of a student dying of suicide after graduation.

School Interventions

Positive Perceptions: School-Based Mental Health

Thirteen school professionals (68%), six parents (32%), one adolescent (5%), and one hospital professional (14%) identified the potential for school-based mental health supports to help adolescents with suicide-related risk. Participants described a variety of school-based mental health supports and services, such as monitoring of suicide-related risk, access to resources, and connection to care. As a school social worker explained:

There’s been a tremendous focus on trauma-informed schools these last 2 years. I think your staff are more in tune with some of the things that are maybe going on with students. Many things that maybe didn’t come to light before are now. That, I’m positive, has an impact. I can’t tell you empirically what that impact is, but I can tell you that we’ve definitely seen an increase.

School professionals emphasized how schools may be well equipped to monitor the safety of these high-risk adolescents, as did this hospital professional, explaining: “Teachers or school staff are a lot more apt to notice something that’s going on with them potentially.” A few school professionals also noted that they felt that their schools could continue to improve screening efforts and ways of reinforcing coping skills. For example, a school psychologist described that although they’ve “done well educating students about the mental health services available at the school,” they could do better at “addressing topics proactively rather than reacting when things come up.”

Negative Perceptions: Minimal Supports for Mental Health.

Six adolescents (32%), one school professional (5%), and three hospital professionals (43%) indicated concerns about minimal support for mental health interventions in schools or the limitations of school rules to allow for flexibility in supporting students with mental health concerns. A 17-year-old girl explained:

I think that our school definitely does not take mental health seriously. If I had cancer, they would be like, “Oh, what can I do to help since you’re getting treatment today,” or “you’re sick because you’re just sore and tired, so it’s fine for you to take a day off. We’ll help you make up your work.” Then, if it’s “I couldn’t sleep last night because I was having a panic attack or I’ve been having consistent panic attacks and, mentally, I cannot handle today. I need a day,” then they’d be like, “Just skippin’. You’re just lazy.”

A 16-year-old girl described how when they sought counseling during a panic attack, they called their dad to take them home because “there was no support” as they were only told “to sit here for 5 minutes and go back to class.”

Finally, three participants (one adolescent, one hospital professional, and one school professional) described how the rigidity of school rules can interfere with mental health supports. A school counselor described how although a student with suicide-related risk was previously engaged in several extracurricular programs, when she began to face problems due to absences related to her mental health, the teachers did not allow the student to continue with those supports. A hospital professional further emphasized this point, identifying “the inflexibility of what happens for kids who are slow to wake up or who have a lot of difficulty socially” as difficult to modify.

Intersecting Bio-Psycho-Social Influences with School and Psychological Functioning

A notable theme across cohorts was the recognition that risk and resilience for adolescents with suicidal thoughts and behaviors is complex and driven by multiple, intersecting factors. School experiences were often considered a secondary influencer of health and well-being, and sometimes described as transacting with other risk factors (i.e., other problems led to school problems, which together lead to worse outcomes). These observations are evident within each of the previous themes, for example, how bullying has been portrayed in the media, but is rarely the sole driver of suicide.

For parents and adolescents, descriptions often related to the interaction of personality characteristics (e.g., perfectionism) and academic pressure, as well as the role of medications, substance use, and underlying psychopathology conferring risk for suicide. After describing how their son was “sneakily smoking pot on campus every single night,” this mother explained how drugs, learning differences, and peer comparisons converged in a problematic way for her son:

It’s not about the school, but the chemicals in his brain while he was trying to survive at this incredibly rigorous school. He’s used to being one of the smartest people in the room, but he never feels that smart because, again, when you take longer to answer a question, you feel like you might not be as smart as the person who answered it quickly even though you might do a better job of answering it. I think he thinks he’s really smart and thinks he’s stupid, and there’s a lot of things with him where he’s here and there at the same time, and that’s almost more painful than just thinking, “Oh, I’m okay.” Being in that, it’s like, “Am I dumbest person here? Am I the—,” I think it made him question himself even more.

For school professionals, some of these observations hinged around how the home environment and economic diversity played a role in student risk, obstructing access to care and making school-based supports and services more essential. For example, a special education teacher explained how remote learning was important for students while they were isolating during the pandemic, “especially the ones whose home life sucks because… even though they can’t get outta there, at least it’s a mental distancing for a few minutes.” When describing how the structure of school can be helpful for students, a school counselor reflected on their own experiences to point to its significance for those with less resources:

Definitely better is the structure. I think that for so long, I grew up in a very stable, safe house. I had both my parents. They were both employed. We didn’t deal with a whole lotta financial hardships. I’m speaking of me, of my own life. I think that has been the hardest thing. I’ve worked with kindergarten through 12th grade, and I think kids feel stuck in where they are. Unfortunately, so often, and good gracious, just research shows this. The cycle continues. Poverty is a cycle.

Hospital professionals perhaps emphasized this theme the most, considering their role in conceptualizing adolescent functioning and care. For example, one stated:

I would say every kid’s probably struggling with school on some level for the most part. It doesn’t mean it’s like—it seems like it contributes in some way. For other kids, it’s more, there’s a really difficult home situation or, in my mind, when you think of that psychopathology, there’s a difference between pure biological psychopathology and then biological that’s been really, really induced by the environment. Then there’s a subset of kids in the former where everything’s mostly, actually, fine. They just have true biological MDD [Major Depressive Disorder]. That’s what it is. School might be stressful, but, really, it’s a very clear pattern…It’s either impacted and/or a secondary exacerbator where things aren’t going well. Then they have to deal with school.

Discussion

Although previous research has demonstrated the significance of school-related experiences for enhancing protective factors (e.g., connectedness) and mitigating risk factors (e.g., bullying) of suicide, few studies have addressed these factors in clinical samples or explored the lived experiences of individuals representative of multiple roles. To address this gap, this qualitative study explored adolescent, parent, school professional, and hospital professional perceptions of how school may relate to adolescents’ suicidal thoughts, behaviors, and mental health. Participants included a diverse sample of adolescents, with 47% representing a racial or ethnic minoritized group and 70% identifying their gender or sexuality in a way that can considered under the umbrella identity of LGBTQ+. Accordingly, special consideration is given to how school psychologists can engage in culturally grounded practices and affirm the sexual and gender identity of youth to enhance their safety and psychological wellbeing in the context of suicide risk (Schultz et al., 2021).

Findings illustrate how school experiences may transact with other risk and protective factors of suicide to impact adolescent mental health. The nature of these influences not only appears to vary across individuals, but also across home and school communities. In the following sections we expand on the themes emerging from adolescent, parent, school professional, and hospital professional perceptions of positive and negative school influences of mental health (i.e., school activities, school social experiences, and school interventions), integrating consideration of the cross-cutting theme pertaining to how intersecting bio-psycho-social factors may contribute to risk. Findings inform how school psychologists can partner with families and other professionals to enhance supports for students with suicidal thoughts and behaviors in school settings, tailoring interventions to the unique needs of each student.

School Activities

Adolescents, school professionals, and hospital professionals, but not parents, noted some of the ways in which participation in school activities, including extracurriculars and school more generally, may help students struggling with suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Participants across cohorts also identified the negative effects of overinvolvement in activities, especially in the context of a culture that reinforces high-performance expectations. Accordingly, supportive practices that foster positive school engagement in youth with suicide-related risk may look different based on the unique needs of each student. Although some students may benefit from supports that increase their school involvement, others may benefit from a change in the type of activities they are involved in or interventions that help mitigate internalized messages of pressures to be perfect.

Enhancing Student Engagement

Although adolescents primarily described the ways that schools can distract them from their other problems or their own internal pain, school and hospital professionals described how students may become more connected and feel more supported when engaged in school. Indeed, positive emotions in school have been found to associate with behavioral engagement (i.e., involvement in learning and participation in school-related activities; Fredricks et al., 2019) through the use of effective coping skills (Reschly et al., 2008). Thus, school engagement may also help to promote positive affect.

In their review of evidence-based interventions addressing student engagement, Archambault and colleagues (2019) provided an extensive list of interventions across a multitiered system of support (MTSS). Although few of these identified interventions focus exclusively on intensive (tier 3) interventions targeting behavioral engagement for at-risk adolescents, Check and Connect (Evelo, 1996) has perhaps the most research support. Findings from several studies have demonstrated Check and Connect as effective for supporting student engagement across multiple contexts (Archambault et al., 2019; Heppen et al., 2018) and it is recommended as an intervention to specifically address suicide-related risk (Miller, 2021).

Most interventions addressing student engagement (including Check and Connect) tend to integrate family partnerships for increasing school participation in students (Archembault et al., 2019), with research supporting a link between family involvement in school and student engagement (Simons-Morton & Crump, 2003). The present study’s findings that no parent participants identified school activities or school engagement as a potential positive school experience for their adolescent provides additional credibility to the importance of connecting with families to engage students with suicide-related risk. Thus, as school psychologists work to enhance school engagement among adolescents facing suicide-related risk, an important first step involves partnering with student families.