Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19)-induced myocarditis constitutes a major mechanism of myocardial injury based on influential reports of outpatients with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome CoronaVirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection1. Subsequent imaging data and endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) and autopsy sample analysis indicated that myocarditis might be far less common, especially in elite-level athletes recovering from COVID-192 , 3. The mechanisms underlying myocardial damage remain uncertain, as no pathological study has shown viral particles to be present within cardiomyocytes4.

Our institution performs a comprehensive annual evaluation of professional soccer players from an elite Greek Super League® team; the evaluation includes electrocardiogram and cardiac ultrasound. Following COVID-19 pandemic, we sought to investigate the effect of SARS-CoV-2 infection on this group. Echocardiography data (two-dimensional, Doppler echocardiographic examinations, and speckle tracking analysis) were obtained at the acute (immediately post quarantine) and recovery (2 months post-verified infection) phases, while stress cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) assessment (including T1, T2 mapping, and late gadolinium enhancement – LGE assessment) was performed only at 2 months on a 3T system. Myocarditis diagnosis was made in accordance with the currently accepted criteria5. Myocardial perfusion analysis was performed with a fully automated, quantitative perfusion scan in three short-axis slices (basal, midventricular, apical) (Fig. 1 ).

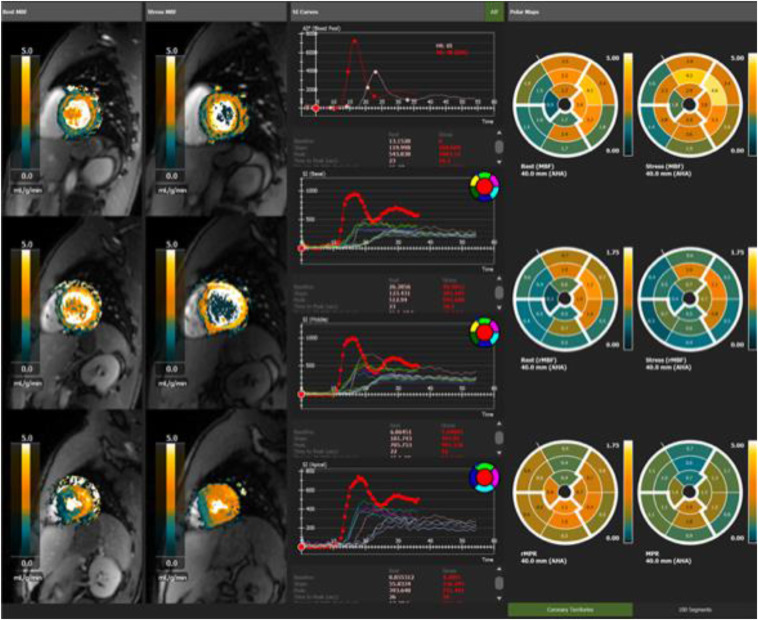

Figure 1.

Results of fully automatic myocardial quantitative perfusion analysis. Fully automated quantitative perfusion analysis. Rest and stress perfusion (left columns) are aligned together with motion correction that allows free breathing acquisition (cvi42MoCo). Pixel-wise myocardial blood flow (MBF) maps at rest and at stress are generated (first row) as well as relative MBF maps (second row), which are computed by first identifying the “healthy” tissue pixels in the MBF and then dividing the myocardial pixels by the average of the healthy pixel values. Myocardial Perfusion Reserve (MPR) and relative MPR derived from the division of the stress by the rest MBF and from their relative counterparts (third column). Signal intensity (SI) curves from the basal, midventricular and apical slice as well as from the blood pool for the calculation of Arterial Input Function (AIF) are depicted (middle column).

With regard to differences in the acute and recovery phase (Table 1 ), lower Emv values at the recovery phase were recorded; however, this did not affect diastolic function, as evidenced by all other related parameters (E/Emv, left atrial volume index, E/A). Finally, although QRS widening was present, its absolute magnitude, approximately 4 msec, with the final value well within the normal range most likely deprive it of any clinical significance. Almost all measured parameters by CMR were within the normal range, with the notable exception of T1 mapping mean value, potentially pointing to a diffuse pattern of myocardial involvement, although normal extracellular volume values weaken this assumption. A single asymptomatic patient had pericardial involvement with no further sequelae. Regarding myocardial perfusion, no abnormalities were noted, rendering moot the possibility of long-term microvascular dysfunction.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and findings in the acute and post-convalescence setting

| N=15 elite soccer athletes | |||

| Parameter | Acute phase | Recovery phase | p-value |

| Age (years) | 26.7±4.5 | - | |

| Sex (% males) | 100 | - | |

| % of maximal predicted heart rate during exercise (pre- vs post-COVID 19) | 88.8±3.8 | 92.4±2.2 | 0.001 |

| Left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (mm) | 54.1±3.7 | 53.4±3.9 | 0.276 |

| Left ventricular end-systolic diameter (mm) | 36.8±2.6 | 36.1±2.7 | 0.06 |

| Interventricular septum (mm) | 9.2±1 | 9.1±1.1 | 0.586 |

| Posterior wall (mm) | 9.2±1.1 | 9.3±1.1 | 0.438 |

| Left atrial volume index (ml/m2) | 30.7±7.7 | 30.9±8.3 | 0.935 |

| Right ventricular end-systolic diameter (mm) | 35.6±2.6 | 34±4.5 | 0.472 |

| E-wave (cm/sec) | 87.2±16.7 | 82.4±17.9 | 0.227 |

| A-wave (cm/sec) | 45.4±10.6 | 44.8±8 | 0.859 |

| E/A | 2±0.6 | 1.9±0.5 | 0.775 |

| Smv (cm/sec) | 11.3±2 | 10.8±2.3 | 0.256 |

| Emv(cm/sec) | 20.2±5 | 17.8±5.2 | 0.01 |

| E/Emv | 4.5±0.9 | 4.8±0.9 | 0.294 |

| Stv (cm/sec) | 15.8±2.6 | 14.4±1.9 | 0.116 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 60.4±3.8 | 60.8±3.6 | 0.175 |

| Global longitudinal peak strain (%) | -18.4±2.8 | -17.6±1.9 | 0.284 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 49.6±2.8 | 50.2±7.9 | 0.885 |

| PR interval (msec) | 177±36 | 170±34 | 0.676 |

| QRS duration (msec) | 97.2±7.7 | 101.6±7.9 | 0.04 |

| QT interval (msec) | 456±12.9 | 432±27.5 | 0.166 |

All values shown as mean ± standard deviation (parametric) or % frequency (nonparametric). Bold font denotes statistically significant differences.

The publication by Puntmann et al1 really stirred interest in myocardial involvement in COVID-19, reporting a dramatically increased prevalence of presumptive myocarditis among mainly nonhospitalized patients (78%). However, the issue of COVID-19-related cardiac involvement in the subgroup of collegiate athletes seems to have been resolved following an observational study6, where among >3,000 COVID-19 positive athletes, definite, probable, or possible cardiac involvement was found by CMR in 0.7% of the cohort. However, both this study and those included in a subsequent meta-analysis7, as opposed to ours, focused only on myocardial and pericardial aspects of cardiac involvement during COVID-19, potentially overlooking any microvascular involve-ment.

Thus, regarding athletes with no pre-existing cardiovascular conditions and none/mild symptoms, myocardial involvement in COVID-19 appears to be rare, justifying the use of liberal algorithms concerning both necessity of cardiac evaluation and timing of return to play8. The novelty of our work lies in using advanced imaging to evaluate all potential components of myocardial involvement following COVID-19, namely myocardial (edema, localized/diffuse fibrosis by using T1 mapping, T2 mapping, LGE), pericardial (LGE), and microvascular (automated perfusion scan). However, as the optimal time to perform CMR is unknown, mild myocardial injury may have eluded detection as CMR scans were obtained at a median of 45 days after a positive COVID-19 test result.

Conflict of interest

Authors report no relationships that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Hellenic Society of Cardiology.

References

- 1.Puntmann V.O., Carerj M.L., Wieters I., et al. Outcomes of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients Recently Recovered From Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA cardiology. Nov 1 2020;5(11):1265–1273. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.3557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brito D., Meester S., Yanamala N., et al. High Prevalence of Pericardial Involvement in College Student Athletes Recovering From COVID-19. JACC Cardiovascular imaging. Mar. 2021;14(3):541–555. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2020.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Starekova J., Bluemke D.A., Bradham W.S., et al. Evaluation for Myocarditis in Competitive Student Athletes Recovering From Coronavirus Disease 2019 With Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging. JAMA cardiology. Jan 14 2021 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.7444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawakami R., Sakamoto A., Kawai K., et al. Pathological Evidence for SARS-CoV-2 as a Cause of Myocarditis: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(3):314–325. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.031. Jan 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caforio A.L., Pankuweit S., Arbustini E., et al. Current state of knowledge on aetiology, diagnosis, management, and therapy of myocarditis: a position statement of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2013;34(33):2636–2648. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht210. 2648a-2648a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moulson N, Petek BJ, Drezner JA, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cardiac Involvement in Young Competitive Athletes. Circulation. 2021 Jul 27;144(4):256-266. Epub 2021 Apr 17. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.054824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Daniels C.J., Rajpal S., Greenshields J.T., et al. Prevalence of Clinical and Subclinical Myocarditis in Competitive Athletes With Recent SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Results From the Big Ten COVID-19 Cardiac Registry. JAMA cardiology. May 27 2021 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2021.2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim J.H., Levine B.D., Phelan D., et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 and the Athletic Heart: Emerging Perspectives on Pathology, Risks, and Return to Play. JAMA cardiology. Feb 1 2021;6(2):219–227. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.5890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]