Abstract

To obtain an estimate for the concentration of free functional RNA polymerase in the bacterial cytoplasm, the content of RNA polymerase β and β′ subunits in DNA-free minicells from the minicell-producing Escherichia coli strain χ925 was determined. In bacteria grown in Luria-Bertani medium at 2.5 doublings/h, 1.0% of the total protein was RNA polymerase. The concentration of cytoplasmic RNA polymerase β and β′ subunits in minicells produced by this strain corresponded to about 17% (or 2.5 μM) of the value found in whole cells. Literature data suggest that a similar portion of cytoplasmic RNA polymerase subunits is in RNA polymerase assembly intermediates and imply that free functional RNA polymerase can form a small percentage of the total functional enzyme in the cell. On infection with bacteriophage T7, 20% of the minicells produced progeny phage, whereas infection in 80% of the cells was abortive. RNA polymerase subunits in lysozyme-freeze-thaw lysates of minicells were associated with minicell envelopes and were without detectable activity in an in vitro transcription assay. Together, these results suggest that most functional RNA polymerase is associated with the DNA and that little if any segregates into DNA-free minicells.

The steady-state activity of a given promoter is completely determined by the two promoter-specific Michaelis-Menten parameters, Vmax and Km, and the free RNA polymerase concentration, [Rf] (see equation 1 in reference 37). It has not yet been possible to experimentally determine [Rf]. With excess polymerase, most promoters would be saturated (i.e., [Rf] >> Km of the average bacterial promoter) and their activities would be independent of [Rf]. Alternatively, with excess DNA, most promoters would be unsaturated and their activities would depend on [Rf] (i.e., [Rf] ≤ Km of the average promoter). Moreover, with excess polymerase, [Rf] would be a significant fraction of the total RNA polymerase, whereas with excess DNA, most polymerase would be associated with DNA and [Rf] would be a only small fraction of the total polymerase. As a result, qualitative information about free RNA polymerase may be obtained by observing the changes in the rate of transcription after changes are made in the DNA concentration. In a replication mutant with reduced DNA concentration (8) or in plasmid-containing minicells undergoing DNA replication (12), the rate of transcription was found to be independent of the DNA concentration; this has led to the suggestion that transcription in vivo is limited by the concentration of free RNA polymerase. However, these observations do not provide a quantitative estimate for [Rf].

It is not immediately obvious how free RNA polymerase can be quantitated experimentally. In previous studies, the distribution of RNA polymerase between the bacterial cytoplasm and nucleoids (36, 41) or between the cytoplasm of DNA-free minicells and DNA-containing large cells of a minicell-producing strain has been determined (38, 40). However, the results of those experiments are somewhat contradictory or ambiguous. For example, using the nucleoid method to determine the concentration of cytoplasmic RNA polymerase, it is difficult to rule out the possibility that a substantial fraction of the RNA polymerase dissociates from the DNA during the high-salt treatment required for isolation of nucleoids; this leads to an overestimate of the amount of RNA polymerase in the cytoplasm. A less error-prone approach is provided by measurement of the RNA polymerase subunit content in DNA-free minicells, which are small portions of cytoplasm partitioned off from the larger DNA-containing cell body in certain mutant bacterial strains. Such measurements are also ambiguous because they measure subunit content and not active RNA polymerase. In addition, some RNA polymerase may be in the form of nonspecifically DNA-bound holoenzyme, which would rapidly equilibrate with free holoenzyme, but it would be associated with the nucleoid and not the minicell cytoplasm.

In the present study we have again used minicell strains of Escherichia coli to readdress the question of free RNA polymerase. Although we cannot provide a final answer on this question, our results, in connection with other published observations, suggest that both free and nonspecifically bound holoenzyme represents only a small percentage of the total polymerase in the cell. This implies that the free RNA polymerase concentration is an important determinant of bacterial gene activities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The minicell-producing strain used was the E. coli K-12 derivative χ925, with the genotype thr ara leu lacY minA minB gal thi sup malA xyl mtl rpsL azi tonA (1, 16). A derivative of this strain, containing the R6K plasmid Amp+ Str+ Tra+ (26), was obtained by transformation (9). As plating bacteria for experiments with T7 bacteriophage, the non-minicell-producing parent strain χ975 (1) was used, although χ925 and R6K-carrying χ925 are equally T7 sensitive.

Cultures were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (33) supplemented with 0.1% glucose and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml or in medium C (19) supplemented with 0.2% glucose, 320 μg of dl-threonine per ml, 270 μg of l-leucine per ml, 20 μg of thiamine per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml. Growth was monitored as the increase in the concentration of cell mass (optical density at 460 nm [OD460]). For growth of χ925 cells containing the R6K plasmid, 250 μg of ampicillin per ml was added to the medium.

Isolation of minicells.

All steps except for culture growth were performed at room temperature. χ925 and χ925-plus-R6K cultures were grown to an OD460 of 1.4 to 2.2 and then centrifuged in a Sorvall SS34 rotor at 2,500 rpm for 5 min to pellet most of the large cells. The supernatant was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 25 min to pellet minicells. A portion of the large-cell pellet from the first centrifugation and the entire minicell pellet were each resuspended in a small volume of buffer (medium C minus supplements), layered onto 5 to 30% sucrose gradients (same buffer) with a 2-ml 60% sucrose cushion, and centrifuged in an SW25.1 rotor (4,000 rpm for 8 min). The gradients usually showed three bands (see Fig. 1); however, for gradients containing χ925 cells plus the R6K plasmid, the middle, small-cell peak was often missing (see Fig. 2b), possibly due to cell aggregation caused by sex pili (27, 28). Minicells and small cells were classified as in Fig. la, while large cells were taken as the pellet from the sucrose gradient containing the resuspended pellet from the first centrifugation. The gradients were entirely collected and fractionated from the top, or the top portion of the minicell band was removed with a handheld syringe. Minicells, small cells, and large cells were slowly diluted with buffer (medium C minus supplements) to at least twice the original volume. The cells were then concentrated by centrifugation (15,000 rpm for 30 min), resuspended in the same buffer or lysis buffer to the concentrations indicated for individual experiments, and either used immediately or stored at −70°C before lysis. The purified minicell preparations were always assayed for contaminating colony-forming cells by plating. Less than 0.5% of the OD460 of the minicell preparation was due to large cells (the fraction would be even smaller if the contamination was with small rather than large cells). Approximately 0.5% of the OD460 units from the initial culture was recovered as purified minicells after one sucrose gradient centrifugation.

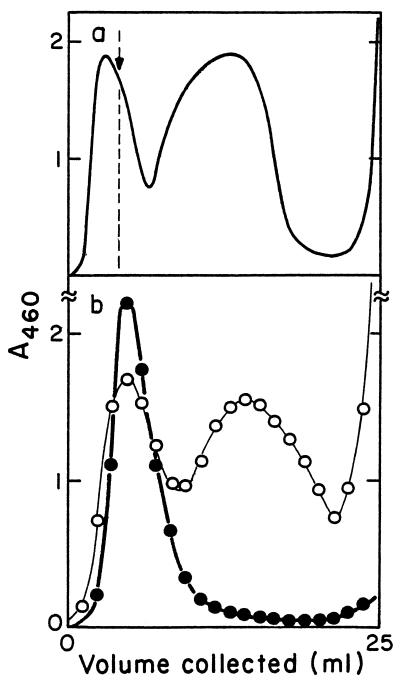

FIG. 1.

Purification of minicells by zone sedimentation through sucrose gradients. (a) Sedimentation distribution obtained from a 100-ml culture after removal of the major portion of large cells by differential centrifugation. (b) The separately pooled minicell (left of dashed line) and small-cell (right of dashed line) preparations from the first centrifugation were concentrated by centrifugation (15,000 rpm for 30 min in a Sorvall SS34 rotor), layered onto seperate sucrose gradients, and centrifuged as before. ●, minicell fraction; ○, small-cell fraction.

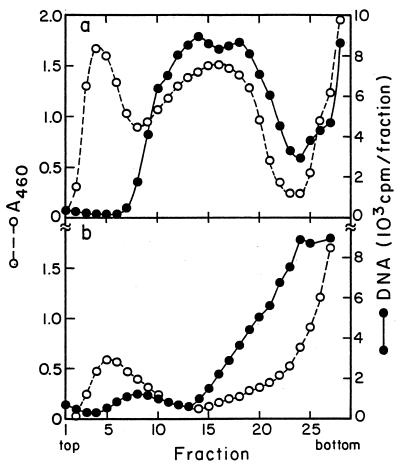

FIG. 2.

Location of DNA in sedimentation distributions of minicells without and with plasmid R6K. Two 100-ml cultures of χ925 (a) and χ925 carrying the R6K plasmid (b) were grown for 10 to 12 h in supplemented medium C containing 250 μg of deoxyadenosine per ml and 0.1 μCi of [6-3H]thymidine per ml (28 Ci/mmol). At an OD460 of 1.3 to 1.7, the cultures were centrifuged, and the crude minicell preparations obtained by differential centrifugation were analyzed by zone sedimentation through sucrose gradients: ○, OD460; ●, acid-precipitable radioactivity. For gradients containing plasmid-carrying χ925 cells, the small cell peak is missing, possibly due to cell aggregation caused by sex pili (see Materials and Methods).

Lysis procedure.

Minicells, small cells, and large cells of χ925 prepared from 3 liters of culture were suspended in lysis buffer (10% sucrose, 0.01 M Tris [pH 8], 0.005 M EDTA, 0.05 M NaCl) to an OD460 of approximately 40 and stored at −70°C. After several days, the cells (and a blank sample containing only lysis buffer) were thawed and kept on ice for 30 min, and then NaCl (0.2 M) and, lysozyme (0.4 mg/ml) were added. After 1 h on ice, the samples were subjected to five freeze-thaw cycles in an ethanol–dry-ice bath, and after the addition of MgCl2 to a final concentration of 0.03 M, they were treated with DNase (0.4 μg/ml) at room temperature for 1 h. DNase treatment was unnecessary for minicells without plasmid DNA; however, all the samples were treated alike.

The extent of lysis was estimated by diluting 20 μl of cell lysate into 3.98 ml of 0.025 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) centrifuging at 15,000 rpm for 20 min, and determining the absorbance at 260 nm (A260) of the supernatant as a measure of the amount of solubilized material (A260 mostly from ribosomes). Another 20 μl of the lysate or blank was heated (2 min at 100°C) with an equal volume of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). After the addition of 3.96 ml of water, the A260 was measured. The difference of A260 of SDS-lysate minus A260 of the SDS-blank sample is a measure of the total amount of UV-absorbing material in the minicell sample. Dividing the A260 of the supernatant after centrifugation by the total A260 determined from boiling the sample in SDS gives the percent lysis. In this manner, 80 to 100% lysis was found for small and large cells and 60 to 70% lysis was found for minicells. However, in a minicell lysate centrifuged for 20 min at 15,000 rpm, more than 90% of the RNA polymerase β and β′ subunits were in the pellet, whereas in a lysate from large cells centrifuged under the same conditions, only 10 to 20% of the polymerase subunits was in the pellet, corresponding to the fraction of unlysed cells. Other large polypeptides were similarly missing in the supernatant of minicell lysates but present in the pellet, indicating that many large proteins, including RNA polymerase, were incompletely liberated from presumably ruptured minicells.

Measurement of the amount of RNA polymerase β and β′ subunits in minicells, small cells, and large cells.

Minicell-, small-cell-, and large-cell lysates, prepared as described above from a 3-liter LB culture, were adjusted to approximately 4 mg of protein/ml (determined by the Lowry assay [30]), diluted with an equal volume of SDS sample solution (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 1% SDS, 1% β-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol, 0.2% bromophenol blue), heated for 2 min in boiling water, and stored at −70°C. For electrophoresis, the SDS-treated lysates were thawed and 150 μl was loaded per sample well onto an SDS–5 to 6.75% polyacrylamide (27 cm-length) slab gel. The slab gel was subjected to electrophoresis, fixed, stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250, and destained as described previously (42). At very low and very high protein concentrations in a particular band of the gel, the band intensity observed in a scan of a lane in the stained gel (see Fig. 3) leads to an underestimate of the amount of protein in the band because of loss of stain during destaining or stain saturation, respectively (42). For this reason, the sample from large cells was coelectrophoresed in various dilutions. In addition, various known concentrations of bovine serum albumin (BSA) were electrophoresed for calibration. From a plot of the peak areas against the concentrations of lysate or BSA, respectively, it was possible to make an appropriate correction for the nonlinearity of the stain per microgram of protein for very small peaks, i.e., for the β and β′ peaks from minicells (see Fig. 3, inset). The percentage of total protein that is RNA polymerase core enzyme was determined by measuring the total protein in the electrophesed lysate, also at different concentrations, using the Lowry assay (30), calibrated with different known concentrations of BSA.

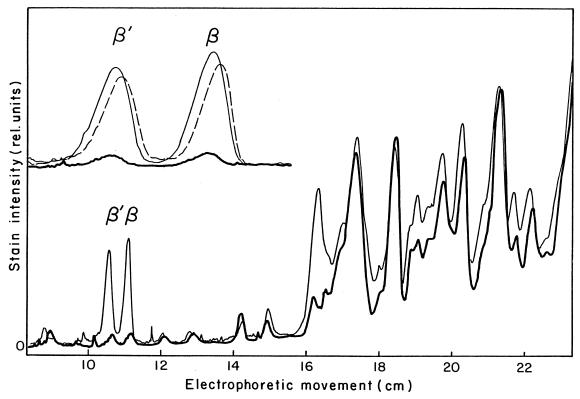

FIG. 3.

RNA polymerase β and β′ subunits in minicells, small cells, and large cells. Densitometer tracing was performed on Coomassie blue-stained polypeptides after electrophoresis. Traces are shown for minicells (thick line), small cells (dashed line), and large cells (thin line). The insert illustrates an expanded abscissa of the ββ′ region. Each sample slot in the SDS-gel contained 0.30 mg of protein. Measurement of the area under a given peak results in an underestimate of the amount of protein present in the smallest and largest peaks; corrections for this were made as described in Materials and Methods.

Measurement of in vitro RNA polymerase activity.

Purified minicells, small cells, and large cells (from a 3-liter culture) were subjected to freeze-thaw lysis and treated with DNase (see above), and the total protein content was measured by the Lowry assay (30). RNA polymerase activity was measured by adding 2 μl of the DNase-treated cell lysate to 55 μl of assay mixture (30 μg of T5 DNA per ml or 100 μg of calf thymus DNA per ml, 0.4 mM each ATP, GTP, and UTP, 1.7 μM [14C]CTP [49 mCi/mmol], 0.1 M KCl [for assays with calf thymus DNA, the KCl was omitted from the reaction mixture], 15 mM MgCl2, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 0.1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mg of BSA per ml) and incubating it at 37°C for 5 min. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 2 ml of ice-cold carrier RNA (50 μg of yeast RNA per ml in 1 M NaCl) and 0.5 ml of 3 M trichloroacetic acid (TCA). Radioactive RNA was collected on a glass fiber filter (Reeve Angel 934AH), rinsed with 0.05 M TCA, dried, and counted.

To liberate RNA polymerase from endogenous DNA fragments protected from DNase degradation by the polymerase, part of each lysate was treated with 2 M KCl (80 mg of KCl to 0.5 ml of lysate) for 1 h at 37°C (41a). This treatment increases the polymerase activity three- to fourfold and rendered more than 90% of the activity sensitive to rifampin.

RESULTS

RNA polymerase β and β′ subunits in minicells.

Crude preparations of minicells from E. coli strain χ925 were obtained after removal of the bulk of the large cells by centrifugation. Zone sedimentation analysis of these preparations showed that they contain three size classes designated minicells, small cells, and large cells (Fig. 1a). These size classes were isolated and subjected again to zone sedimentation (Fig. 1b). The minicell preparation was essentially pure (Fig. 1b) and did not contain DNA (Fig. 2a, fractions 1 to 6). Colony-forming cells per concentration of cell mass (OD460) were determined for minicell, small-cell, and large-cell preparations by plating various dilutions. In the minicell preparation, less than 0.5% of the OD460 was accounted for by colony-forming large or small cells (data not shown) (this value was much less than 0.5% if most colony formers were contaminating small rather than large cells). Small cells are assumed to be the remainders of whole cells that have lost parts of their distal cell bodies in minicell divisions. They had a normal concentration of DNA (DNA/OD460, Fig. 2a, fractions 10 to 25).

The purified minicells, small cells, and large cells were lysed with lysozyme and by freeze-thaw cycles and analyzed by SDS-electrophoresis (Fig. 3 shows a representative example). Minicells and small cells were found to contain approximately 17 and 92%, respectively, of the number of RNA polymerase β and β′ subunits per total protein compared to large cells (Fig. 3; Table 1). The peak areas of the β and β′ subunits in the gel scans from minicells were only 11 to 12% in comparison to those in large cells (Fig. 3, inset); however, the use of controls with various known concentrations of protein has previously shown that very small peaks in Coomassie blue-stained gels tend to be underestimated (42); therefore, the somewhat higher value of 17% in Table 1 was obtained after an appropriate correction (Fig. 3 legend). Most other polypeptides were present in approximately equal proportions in minicells and large cells. The distribution in Fig. 3 is representative of several repeats of the experiments, with little variation in the relative height of the subunit peaks obtained from minicells. These results suggest that most bacterial RNA polymerase is DNA associated and that only a small fraction (about 17% based on β and β′ subunit composition) is cytoplasmic.

TABLE 1.

RNA polymerase content and activity in large cells, small cells, and minicells of strain χ925

| Cell typea | Protein concnb (mg/ml) | αpc (%) | RNA polymerase activity

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cpm/2 μld (%) | cpm/μg of proteine (%) | cpm/μg of polymerasef (%) | |||

| Large | 15.5 | 1.00 | 1,441 (100) | 46.4 (100) | 4,640 (100) |

| Small | 9.2 | 0.92 | 859 (69) | 46.6 (100) | 5,065 (109) |

| Mini | 2.6 | 0.17 | 1 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.1) | 118 (2.5) |

Minicell, small-cell, and large-cell lysates were prepared as described in Materials and Methods.

A portion of each lysate was used to determine the protein concentration.

Another portion of each lysate was subjected to SDS-gel electrophoresis (see Materials and Methods) (Fig. 3), and αp (percentage of total protein that is RNA polymerase protein) was determined.

Each value is the average (minus blank) of two assays on T5 DNA after KCl treatment (see Materials and Methods for details). The values in parentheses were calculated by setting the large-cell value to 100%.

The RNA polymerase activity per microgram of total protein is the quotient of the values in the columns indicated by footnotes d and b, divided by 2 (microliters per assay).

The RNA polymerase activity per microgram of RNA polymerase is the quotient of the values in the columns indicated by footnotes e and c.

RNA polymerase β and β′ subunits in plasmid-carrying minicells.

The largest, but apparently not all, minicells derived from a minicell strain carrying R6K plasmids contained DNA (presumably plasmid DNA), as seen from the sedimentation profile of a crude preparation of minicells labeled with radioactive thymidine (Fig. 2b). The amount of RNA polymerase β and β′ subunits per total protein in R6K-carrying minicells was found to be 20 to 22% of the amount in large cells (data not shown, obtained as in Fig. 3). This represents a 24% (21/17 = 1.24) increase compared to plasmid-free minicells, corresponding to 4% (21% − 17%) of the total subunits.

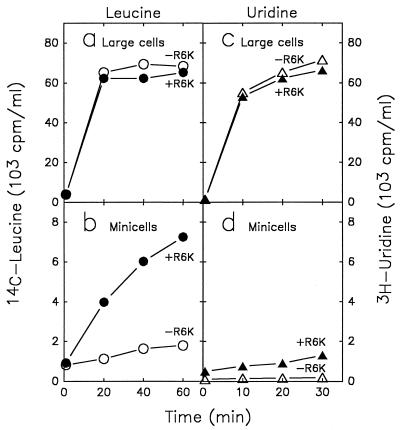

In agreement with previous reports (12, 23, 39), plasmid-carrying minicells also synthesized measurable amounts of RNA and protein, as demonstrated by incorporation of radioactive uridine and leucine (Fig. 4). This shows that minicells are capable of macromolecular syntheses if they contain plasmid DNA at the time of their formation. The rate of incorporation of exogenous uridine into plasmid-carrying minicells (Fig. 4d) corresponded to about 0.3% of the rate observed with large cells (Fig. 4c, initial slope); however, this value does not reflect the relative rate of transcription in minicells, because the specific radioactivity of UMP incorporated into RNA is diluted by UMP from decaying nonradioactive mRNA. This dilution differs for large cells, which synthesize both mRNA and stable RNA, and for minicells, which synthesize only plasmid mRNA. Even if transcription rates for plasmid-carrying minicells could be determined, such data cannot be interpreted in terms of RNA polymerase concentrations without specific knowledge about the concentrations and kinetic properties of the plasmid promoters. The rates of incorporation into plasmid-free minicells corresponded to less than 0.1% of the rates with whole cells and suggest that the contamination of the minicell preparations with whole cells was below 0.1% in terms of cell mass (below 0.01% in terms of cell numbers).

FIG. 4.

RNA and protein synthesis in minicells and large cells. The incorporation of [14C]leucine or [3H]uridine into acid-precipitable material was measured in large cells (a and c) or minicells (b and d) of strain χ925 with (●, ▴) and without (○, ▵) R6K plasmid. Purified minicells and large cells were suspended to an OD460 of 0.4 in medium C supplemented with 0.2% glucose, 320 μg of dl-threonine per ml, and 20 μg of thiamine per ml. Each cell suspension was divided into equal portions for RNA and protein labeling. The portion for RNA labeling received 270 μg of l-leucine per ml. The cell suspensions were incubated at 37°C for 10 min with aeration before addition of radioctivity and plating for viable cells. For incorporation of [14C]leucine (a and b), a 2-ml portion of minicells or large cells, respectively, was added to 0.2 ml (0.1 μCi) of [14C]leucine (312 Ci/mol) at time zero and incubated at 37°C with aeration. Samples (0.1 ml) were removed into 1 ml of cold 1 M TCA, heated for 30 s in a boiling-water bath, and cooled to 0°C. Radioactive acid-precipitable material was collected on glass fiber filters and counted. For incorporation of [3H]uridine, a 2.5-ml portion of minicells or large cells was added to 0.5 ml (2.5 μCi) of [5-3H]uridine (21 Ci/mmol) at time zero and incubated at 37°C with aeration. Samples (0.5 ml) were added to 2 ml of cold 1 M TCA, and acid-precipitable radioactivity was collected on glass fiber filters and counted. The scales for large cells and minicells differ by 10-fold. The time zero values represent background radioactivity, and the slight increases in radioactivity seen with plasmid-free minicells are presumed to result from contaminating nucleated cells. The labeling plateaus observed with large cells reflect exhaustion of the exogenous precursor from the medium.

T7 infection of minicells.

It has been reported that only 0.1% of minicells infected with 10 T7 phage per minicell produce progeny (35); this is so low that the result might not be significant. With T4 phage-infected minicells, a yield of one T4 phage per infected center has been reported (39), but since no adsorption and growth kinetics were shown, it is not clear to what extent free phage and whole cells might have contributed to the infective centers. Therefore, we decided to investigate this question further. As a control, a culture with normal (large) cells was infected (8 × 107 bacteria per ml infected with 1.3 × 107 T7 phage per ml, corresponding to a multiplicity of infection of 0.16) (Fig. 5, time points at 5 to 8 min). Under these conditions, a burst of 160 phage per infected bacterium was observed 10 to 15 min after infection (Fig. 5, points after 10 min). Phage adsorption was monitored by measuring infective centers in chloroform-treated samples (Fig. 5). The plaques on these plates represent both free phage and progeny phage from cells prematurely lysed by chloroform (beginning after 5 min). Over 90% of input phage were adsorbed within 1 to 2 min; the first intracellular progeny phage appeared at about 5 min. The decrease in PFU per milliliter seen in the chloroform-treated samples at approximately 15 min is due to readsorption of liberated progeny phage to bacteria in the adsorption tube.

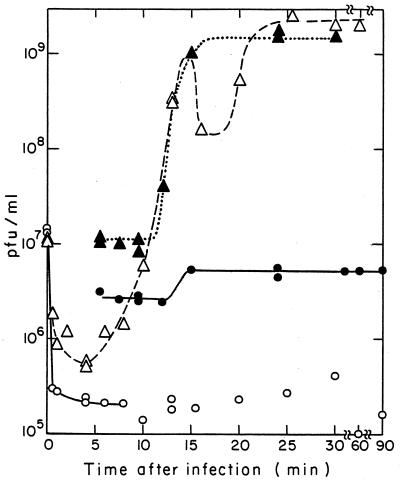

FIG. 5.

Adsorption and one-step growth curve of T7 bacteriophage infection of minicells and large cells of strain χ925. Purified minicells and large cells were resuspended in supplemented LB medium to an OD460 of 0.455 (about 8 ×108 minicells and 3 ×105 viable cells/ml) and 0.480 (8 ×107 viable cells/ml), respectively. The minicells (2.7 ml) were incubated for 5 min at 37°C with aeration before the addition at t = 0 of 0.3 ml of T7 phage to a final concentration of 1.3 ×107 PFU/ml. ○, adsorption to minicells. (At the indicated times, 0.1-ml samples were diluted 1:50 into chloroform-saturated supplemented LB medium at 37°C, and the number of free phage in these chloroform tubes was later determined by plating). ●, one-step growth curve for minicells, determined by removing 0.1-ml samples from the absorption tube at various times, making appropriate dilutions, and plating. To prevent readsorption of progeny phage, samples were removed from a tube (made at t = 8.5 min) containing a 1:250 dilution of the adsorption mixture. ▵, adsorption kinetics; ▴, one-step growth curve with χ925 large cells, obtained as with minicells, except for different dilutions.

A minicell preparation with the same concentration of cell mass (OD460) as used for large cells, but containing about 10 times more minicells (8 × 108/ml) and 3 × 105 contaminating colony-forming small and large cells per ml, was infected similarly with 1.3 × 107 PFU of T7 phage/ml (i.e., at a multiplicity of infection of about 0.02). Between 5 and 10 min after the addition of phage, only 2.6 × 106 infective centers per ml were detected (Fig. 5, points between 5 and 12 min), of which about 2 × 105/ml were due to free phage (Fig. 5, points after 5 min), whereas the remaining 2.4 × 106 infective centers/ml must have resulted from infected minicells. Thus, about 20% of the adsorbed input phage was able to reproduce and liberate progeny phage in minicells, whereas 80% of adsorbed input phage produced abortively infected minicells.

The burst size in the minicell preparation at 12 to 15 min was only two phage per infected center (Fig. 5). In the minicell preparation used for infection, at most 0.3% of the total cell mass in the minicell preparation was in colony-forming small and large cells (probably less than 0.3% if the preparation was contaminated mostly with small rather than large cells). The fraction of input T7 phage adsorbed to these larger nucleated cells is estimated to be similarly small (at most 0.003 × 1.3 × 107 = 3.9 × 104 infected nucleated cells per ml). Thus, at most 10% of the total number of contaminating colony-forming cells present (3 × 105/ml) were infected. If these infected nucleated cells produced a normal burst of 160 phage per bacterium (see above), their total yield would be similar to the observed burst at 15 min of infection (Fig. 5; observed increase of 2.5 × 106/ml in infective centers; maximum expected burst from infected nucleated cells = 3.9 × 104 × 160 = 6.2 × 106 phages/ml). Therefore, the small burst seen in Fig. 5 (points between 10 and 15 min) appears to have resulted from infection of nucleated cells contaminating the minicell preparation.

In the chloroform-treated minicells, no rapid increase in the production of progeny phage is seen (Fig. 5). This suggests that the infective centers obtained from minicells (2.4 × 106/ml, see above) are the result of late cell lysis that occurred mostly after the 90 min of the experiment in Fig. 5, i.e., during incubation of the plate used to determine infective centers. Apparently infected nucleated small cells were not prematurely lysed by chloroform.

In summary, it appears as if only about 20% of the minicells possessed sufficient RNA polymerase and perhaps other limiting factors to be able to produce enough phage proteins and lysozyme to liberate one or more progeny phage after an unusual long delay. The results shown in Fig. 5 are representative of several independent experiments. The same results were obtained with minicells from plasmid R6K-carrying bacteria, which contain 24% more RNA polymerase subunits than do plasmid-free minicells (see above).

Absence of RNA polymerase activity in minicell lysates.

It has been reported that minicell extracts are devoid of RNA polymerase activity (11). To reinvestigate this question, RNA polymerase activity was assayed in freeze-thaw lysates from lysozyme-treated minicells, small cells, and large cells, using bacteriophage T5 DNA as templates. With lysates from large and small cells, the activity was 95% dependent on the addition of exogenous DNA and greater than 95% sensitive to rifampin. Large and small cells had an activity of about 5,000 cpm (standard assay) per μg of RNA polymerase, whereas RNA polymerase prepared from minicells had no measurable activity (1 cpm over a counting background of 50 cpm) or less than 2.5% of the activity observed with large cells (Table 1). The procedure used to lyse minicells liberated 60 to 70% of the total cellular UV-absorbing material (mostly rRNA and tRNA) but only about 10% of the RNA polymerase β and β′ subunits (see Materials and Methods). It is therefore possible that the T5 DNA used as a template for the in vitro transcription assays did not have access to the RNA polymerase in partially disrupted minicells. With about 10% of minicell β and β′ subunits liberated and accessible to DNA (see above), the results suggest that less than 25% of β and β′ subunits in minicells represent functional enzyme.

DISCUSSION

Comparison of the present data with previously reported data.

In a previous investigation with minicells from bacteria growing at 1.23 doublings/h, values of 0.086 and 0.61% for the concentrations of cytoplasmic and total RNA polymerase (relative to total protein), respectively, were reported (40). This corresponds to 14% (0.086/0.61 = 0.14) cytoplasmic RNA polymerase, similar to the value observed here at a growth rate of 2.5 doublings/h (Table 1; Fig. 3), and suggests that the proportion of total polymerase in the cytoplasm is rather independent of the growth rate. In a contradictory study (38), 0.5 to 1.5% of total minicell protein was found to be β and β′ RNA polymerase subunits. This aberrantly high value is similar to the proportion of RNA polymerase in total protein that has been found in wild-type strains or in the DNA-containing cells of the mutant minicell-producing strain and suggests either that most RNA polymerase is cytoplasmic and not DNA associated or that the minicell fractionation in that study was inefficient. In that study, no sedimentation patterns for the minicell preparations were shown and no control values were given.

When the distribution of RNA polymerase was previously examined after separation of nucleoids from bacterial extracts, about one-third of the total polymerase was found in the cytoplasm (36, 41). This high value may be explained by assuming that some polymerase dissociates from the DNA during nucleoid preparation; high salt concentrations are known to reduce the binding of RNA polymerase to DNA.

RNA polymerase assembly intermediates in the bacterial cytoplasm.

For a culture of an E. coli K-12 strain growing at 37°C in glucose minimal medium with a 70-min doubling time, it takes 1.5, 5, and 15 min for pulse-labeled β′, β, and α subunits, respectively, to appear in the nucleoid (41). Since the assembly of RNA polymerase occurs in the order α2, α2β, and α2ββ′ (17, 21), Saitoh and Ishihama (41) suggested that the assembly of a complete core enzyme under their conditions takes about 15 min, with the β′ subunit added last. This means that about 1.5 min after the addition of the β′ subunit, the complete core enzyme becomes active in transcription. At their culture-doubling time of 70 min, an RNA polymerase assembly time of 15 min would mean that perhaps up to 16% of the total subunit protein is in assembly intermediates in the cytoplasm (215/70 = 1.16, i.e., 16% of α subunits and lesser amounts of β and β′ subunits). However, the long time required to “chase” labeled α subunits from the cytoplasm into the nucleoid fraction probably reflects the excess synthesis of α subunits over the other subunits (18, 22, 23). Therefore, it is likely that the delay times of 5 and 1.5 min for the appearance of the β and β′ subunits in the nucleoid are more representative of the holoenzyme assembly time.

For bacteria grown in LB medium with a 25-min doubling time, the assembly of β and β′ subunits into active RNA polymerase must be finished in less than 5.6 min to obtain a value of partially assembled subunits that does not exceed the observed (17%) total cytoplasmic β and β′ subunits (25.6/25 = 1.17) present in minicells. Therefore, an assembly time between 1.5 and 5 min must mean that a substantial proportion of cytoplasmic β and β′ subunits represents RNA polymerase assembly intermediates. At a growth rate of 2.5 doublings/h, bacteria of the E. coli strain B/rA contain about 11,400 RNA polymerase β and β′ subunit molecules per average cell (42) (data summarized in Table 3 of reference 3). From our minicell segregation measurements, 83% (9,500 molecules) appear to be DNA bound and 17% (1,900 molecules) appear to be free in the cytoplasm. With an average cell volume of approximately 1.25 μm3 (at a growth rate of 2.5 doublings/h in glucose-amino acids medium [8], 1,900 cytoplasmic RNA polymerase molecules correspond to a concentration of 2.5 μM). If most of these 1,900 molecules are in the form of assembly intermediates (see above), the bacterial cytoplasm may contain only few hundred free functional enzyme molecules, i.e., probably in the nanomolar range. With more than 1,000 active mRNA genes (34), this would be less than one functional free RNA polymerase enzyme per active gene.

Minicells have approximately 1/10 the volume of the large DNA-containing cells, so a single minicell contains about 190 cytoplasmic β and β′ subunits, and only a few of these are functional enzymes. Previously, protein synthesis could not be detected in minicells after introduction of plasmid DNA by conjugation (15). However, we observed here that 20% of T7 phage-infected minicells produced progeny phage, which requires RNA and protein synthesis.

In vitro inactivity of RNA polymerase in minicell extracts.

The activity of RNA polymerase in the lysozyme freeze-thaw lysates of minicells was below the detectable assay minimum (Table 1). A similar result has been reported previously and cited as evidence for the absence of active RNA polymerase in minicells; no experimental details were given about the assay conditions (J. Hurwitz and M. Gold, unpublished data, cited in references 10 and 38). In our experiments, most (about 90%) of the RNA polymerase subunits were associated with partially ruptured minicells (see Materials and Methods); therefore, the in vitro inactivity might reflect a difficulty in getting the DNA templates to the RNA polymerase. It is unlikely that RNA polymerase was inactivated during the incubation of minicells, because RNA polymerase activity in plasmid-carrying minicells is essentially stable over at least 3 h (12). The probability of minicell formation is proportional to the cell number in a given volume of culture, so that 50% of the minicells were formed during the last generation (i.e., 25 min) before harvesting. It is also unlikely that RNA polymerase was not released from minicells because of its large size (much larger ribosomes were mostly released) or that the enzyme was inactivated during the isolation procedure (the same procedure worked well for large and small cells). Moreover, a lack of ς subunits was probably not the reason for the inactivity of the RNA polymerase, since core enzyme, although not active on phage DNA, is active on calf thymus DNA (5); minicell extracts had no increased polymerase activity in an assay with calf thymus DNA (data not shown). Finally, a lack of α subunits in minicells is unlikely, since the α2 intermediates are the first to form during assembly and are presumed to be present in excess in the cytoplasm (22, 23). Therefore, the inactivity might reflect a technical difficulty in disrupting minicells and recovering active polymerase and/or an absence of functional enzyme, e.g., if the last steps of polymerase core maturation require association with the nucleoid, a possibility considered by Saitoh and Ishihama (41).

In vivo distribution of RNA polymerase.

A possible cellular partitioning for RNA polymerase has previously been suggested as follows (37) (Fig. 5 in reference 32): ∼50% actively transcribing core, ∼25% specifically bound holoenzyme, ∼25% nonspecifically bound core and holoenzyme, and <1% free holoenzyme. According to the above results, about 83% of total RNA polymerase subunits are associated with DNA. Previously, about 30% of the total RNA polymerase was found to be active in RNA chain elongation at any given time (at 2.5 doublings/h [13, 31, 42]). This means that 64% [(83 − 30)/83 = 0.64] of the DNA-bound polymerase is inactive.

The effector ppGpp is known to cause transcriptional pausing (see, e.g., reference 25); this may lead to RNA polymerase queuing behind a pausing enzyme, thereby trapping a substantial proportion of the total RNA polymerase (4). In ppGpp-deficient bacteria, up to 60% of the RNA polymerase is active in transcription, i.e., twice as much as in ppGpp-proficient strains (20). Therefore, we suggest that about 30% of the RNA polymerase in ppGpp-proficient strains is temporarily pausing during transcription. The remaining 23% of the DNA-associated polymerase is likely to be mostly holoenzyme specifically bound to mRNA promoters (32). For example, if the average promoter clearance time equals the average transcription time of a gene, then the fraction of promoter-bound holoenzyme equals the fraction of transcribing enzyme, i.e., 30%. For mRNA promoters, promoter clearance may take several minutes (29), longer than the actual transcription times (e.g., 30 s for an average mRNA of 1,500 nucleotides).

An upper limit for the amount of promoter-bound RNA polymerase is set by the amount of ς factor in E. coli, which corresponds to 20 to 30% of the total core enzyme (18, 22, 23). Saitoh and Ishihama (41) found little ς subunit present in the nucleoid, but it seems likely that the promoter-bound holoenzyme is preferentially released during the high-salt treatment required for the preparation of nucleoids. A small fraction of the inactive and nonpausing DNA-associated enzyme (included in the 23%) might also be nonspecifically DNA-bound core enzyme, whose dissociation is slow (6). If about 17% of the RNA polymerase subunits are cytoplasmic, most of them in the form of assembly intermediates (see above), this leaves only a small percentage for the two other forms of RNA polymerase: nonspecifically DNA-bound holoenzyme that dissociates fast and acts as a reservoir for free holoenzyme and free holoenzyme itself. Nonspecifically DNA-bound holoenzyme might slide along the DNA to find a promoter; however, no significant contribution of sliding to the velocity of productive initiation has yet been demonstrated (37).

Based on these considerations, we propose the following approximate distribution of polymerase in fast-growing (ppGpp-proficient) bacteria: 30% transcribing core, 30% paused and queued core, 23% promoter-bound holoenzyme, 15% cytoplasmic premature core, and 2% nonspecifically DNA-bound and free holoenzyme in rapid equilibration. This distribution implies that free ς is in excess over free core. Free core is generated during transcript termination at a rate equal to the rate of transcript initiation; with excess free ς, the released core would be rapidly reconverted to holoenzyme, thereby preventing the nonspecific (tight and nonproductive) binding of free core to DNA. This description of the distribution of cellular RNA polymerase, although still hypothetical, seems more complete than previously suggested distributions.

Implications for the control of gene activities.

Taken together, the results reported here indicate that free functional RNA polymerase is a limiting factor for the rate of transcription. This is consistent with reported observations indicating that the rate of transcription in E. coli is independent of the DNA concentration (i) in bacterial strains with lower DNA concentration due to a mutation affecting DNA replication (8), (ii) in plasmid-carrying minicells whose plasmids continue to replicate (12), (iii) after a change in the copy number of the particularly active rrn genes as a result of DNA replication during the cell cycle (14), and (iv) after artificial deletion (11) or addition (2, 24) of rrn genes.

When RNA polymerase is limiting for transcription, it implies that many promoters are not saturated and that changes in the concentration of free RNA polymerase must contribute to the control of gene activities (see above). Such changes in free RNA polymerase concentration are expected to occur both as a result of changes in the concentration or activity of promoters as mentioned above, including repression of mRNA genes in response to nutrients in the growth medium, and as a result of changes in RNA polymerase synthesis during growth at different rates (42). Because of their apparently higher Km values, rRNA promoters would be more strongly affected by changes in free RNA polymerase than would mRNA promoters, which appear to approach saturation during growth in rich media (29).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant GM15412 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and by a grant from the Medical Research Council of Canada. N.S. was the recipient of a Grant-In-Aid from Sigma Delta Epsilon—Graduate Women in Science, Inc.

We thank Jana Shafer for her assistance with the in vitro RNA polymerase assay.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adler H I, Fisher W D, Cohen A, Hardigree A A. Miniature Escherichia coli cells deficient in DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1967;57:321–326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.57.2.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baracchini E, Bremer H. Control of rRNA synthesis in Escherichia coli at increased rrn gene dosage. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:11753–11760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bremer H, Dennis P P. Modulation of chemical composition and other parameters of the cell by growth rate. In: Neidhardt F C, et al., editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 1553–1569. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bremer H, Ehrenberg M. Guanosine tetraphosphate as a global regulator of bacterial RNA synthesis: a model involving RNA polymerase pausing and queuing. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1262:15–36. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(95)00042-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burgess R R, Travers A A, Dunn J J, Bautz E K F. Factor stimulating transcription hy RNA polymerase. Nature (London) 1969;221:43–46. doi: 10.1038/221043a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chamberlin M J. RNA polymerase—an overview. In: Losick R, Chamberlin M, editors. RNA polymerase. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1976. pp. 17–67. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Churchward G, Estiva E, Bremer H. Growth rate-dependent control of chromosome replication initiation in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:1232–1238. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.3.1232-1238.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Churchward G, Bremer H, Young R. Transcription in bacteria at different DNA concentrations. J Bacteriol. 1982;150:572–581. doi: 10.1128/jb.150.2.572-581.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen S N, Chang A C Y, Hsu L. Nonchromosomal antibiotic resistance in bacteria: genetic transformation of Escherichia coli by R-factor DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1972;69:2110–2114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.8.2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen A, Fisher W D, Curtiss III R, Adler H I. The properties of DNA transferred to minicells during conjugation. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1968;33:631–641. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1968.033.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Condon C, French S, Squires C, Squires C L. Depletion of functional ribosomal RNA operons in Escherichia coli causes increased expression of the remaining intact copies. EMBO J. 1993;12:4305–4315. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06115.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crooks J H, Ullmann M, Zoller M, Levy S R. Transcription of plasmid DNA in minicells. Plasmid. 1983;10:66–72. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(83)90058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dalbow D G. Synthesis of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli B/r growing at different rates. J Mol Biol. 1973;75:181–184. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90537-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dennis P P. Stable ribonucleic acid synthesis during the cell division cycle in slowly growing Escherichia coli B/r. J Biol Chem. 1972;247:204–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fralick J A, Fisher W D, Adler H I. Polyuridylic acid-directed phenylalanine incorporation in minicell extracts. J Bacteriol. 1969;99:621–622. doi: 10.1128/jb.99.2.621-622.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frazer A C, Curtiss R., III Production, properties and utility of bacterial minicells. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1975;69:1–84. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-50112-8_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fukuda R, Ishihama A. Subunits of RNA polymerase in function and structure. V. Maturation in vitro of core enzyme from Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1974;87:523–540. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(74)90102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayward R S, Fyfe S. Over-synthesis and instability of sigma protein in a merodiploid strain of Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1978;159:89–99. doi: 10.1007/BF00401752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helmstetter C E. Rate of DNA synthesis during the division cycle of Escherichia coli B/r. J Mol Biol. 1967;24:417–427. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hernandez V J, Bremer H. Characterization of RNA and DNA synthesis in Escherichia coli strains devoid of ppGpp. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:10851–10862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ito K, Iwakura Y, Ishihama A. Biosynthesis of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli. III. Identification of intermediates in the assembly of RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol. 1975;96:257–271. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(75)90347-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iwakura Y, Ishihama A. Biosynthesis of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli. II. Control of RNA polymerase synthesis during nutritional shift up and down. Mol Gen Genet. 1975;142:67–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwakura Y, Ito K, Ishihama A. Biosynthesis of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli. I. Control of RNA polymerase content at various growth rates. Mol Gen Genet. 1974;133:1–23. doi: 10.1007/BF00268673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jinks-Robertson S, Gourse R, Nomura M. Expression of rRNA and tRNA genes in Escherichia coli: evidence for feedback regulation by products of rRNA operons. Cell. 1983;33:865–876. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90029-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kingston R E, Chamberlin M. Pausing and attenuation of in vitro transcription in the rrnB operon of E. coli. Cell. 1981;27:523–531. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90394-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kontomichalou P, Mitani M, Clowes R C. Circular R-factor molecules controlling penicillinase synthesis, replicating in Escherichia coli under either relaxed or stringent control. J Bacteriol. 1970;104:34–44. doi: 10.1128/jb.104.1.34-44.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levy S B. Physical and functional characteristics of R-factor deoxyribonucleic acid segregated into Escherichia coli minicells. J Bacteriol. 1971;108:300–308. doi: 10.1128/jb.108.1.300-308.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levy S B. Use of mucoid bacterial mutants to circumvent clumping of cells and minicells containing R plasmids derepressed for pilus synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1974;120:534–535. doi: 10.1128/jb.120.1.534-535.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liang S, Bipatnath M, Xu Y-C, Chen S-L, Dennis P P, Ehrenberg M, Bremer H. Activities of constitutive promoters in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1999;292:19–37. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matzura H, Hansen B S, Zeuthen J. Biosynthesis of the and β′ subunits of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1973;74:9–20. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McClure W R. Mechanism and control of transcription initiation in prokaryotes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:171–204. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.001131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neidhardt F C, Umbarger H E. Chemical composition of Escherichia coli. In: Neidhardt F C, et al., editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ponta H, Reeve J N, Pfennig-Yeh M, Hirsch-Kauffman M, Schweiger M, Herrlich P. Productive T7 infection of Escherichia coli F+ cells and anucleate minicells. Nature (London) 1977;269:440–442. doi: 10.1038/269440a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Portalier R, Worcel A. Association of the folded chromosome with the cell envelope of E. coli: characterization of the proteins at the DNA-membrane attachment site. Cell. 1976;8:245–255. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(76)90008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Record M T, Reznikoff E S, Craig M L, McQuade K L, Schlax P. Escherichia coli RNA polymerase (Eς70), promoters, and the kinetics of the steps of transcription initiation. In: Neidhardt F C, et al., editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 792–821. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rogerson A, Stone J E. β-β′ subunits of ribonucleic acid polymerase in episome-free minicells of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1974;119:332–333. doi: 10.1128/jb.119.1.332-333.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roozen K J, Fenwick R G, Jr, Curtiss R., III Synthesis of ribonucleic acid and protein in plasmid-containing minicells of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1971;107:21–33. doi: 10.1128/jb.107.1.21-33.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rünzi W, Matzura H. Distribution of RNA polymerase between cytoplasm and nucleoid in a strain of Escherichia coli. In: Kjeldgaard N O, Maaloe O, editors. Control of ribosome synthesis. 1976. pp. 115–116. Alfred Benzon Symposium IX. Munksgaard, Copenhagen, Denmark. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saitoh T, Ishihama A. Biosynthesis of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli. VI. Distribution of RNA polymerase subunits between nucleoid and cytoplasm. J Mol Biol. 1977;115:403–416. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90162-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41a.Shafer J. M.S. thesis. University of Texas at Dallas; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shepherd N S, Churchward G, Bremer H. Synthesis and activity of ribonucleic acid polymerase in Escherichia coli B/r. J Bacteriol. 1980;141:1098–1108. doi: 10.1128/jb.141.3.1098-1108.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]