Abstract

BACKGROUND

Esophageal submucosal hematoma is a rare condition. Although the exact etiology remains uncertain, vessel fragility with external factors is believed to have led to submucosal bleeding and hematoma formation; the vessel was ruptured by a sudden increase in pressure due to nausea, and the hematoma was enlarged by antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy. Serious conditions are rare, with a better prognosis. We present the first known case of submucosal esophageal hematoma-subsequent hemorrhagic shock due to Mallory-Weiss syndrome.

CASE SUMMARY

A 73-year-old female underwent endovascular treatment for an unruptured cerebral aneurysm. The patient received aspirin and clopidogrel before surgery and heparin during surgery, and was well during the surgery. Several hours after returning to the ICU, she complained of chest discomfort, vomited 500 mL of fresh blood, and entered hemorrhagic shock. Esophageal submucosal hematoma with Mallory-Weiss syndrome was diagnosed through an endoscopic examination and computed tomography. In addition to a massive fluid and erythrocyte transfusion, we performed a temporary compression for hemostasis with a Sengstaken-Blakemore (S-B) tube. Afterwards, she became hemodynamically stable. On postoperative day 1, we performed an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and confirmed no expansion of the hematoma nor any recurring bleeding; therefore, we removed the S-B tube and clipped the gastric mucosal laceration at the esophagogastric junction. We started oral intake on postoperative day 10. The patient made steady progress, and was discharged on postoperative day 33.

CONCLUSION

We present the first known case of submucosal esophageal hematoma subsequent hemorrhagic shock due to Mallory-Weiss syndrome.

Keywords: Esophageal submucosal hematoma, Hemorrhagic shock, Mallory-Weiss syndrome, Antithrombotic therapy, Anticoagulant therapy, Case report

Core Tip: Esophageal submucosal hematoma is a rare condition. Although the exact etiology remains uncertain, vessel fragility with external factors is considered to have led to submucosal bleeding and hematoma formation, with the vessel ruptured by a sudden increase in pressure due to nausea, and the hematoma was enlarged by antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy. Serious conditions are rare, with a better prognosis. We present the first known case of submucosal esophageal hematoma-subsequent hemorrhagic shock due to Mallory-Weiss syndrome. In addition, submucosal esophageal hematoma after coiling embolization for unruptured cerebral aneurysm is a very rare event, so there is also value in reporting this event.

INTRODUCTION

Esophageal submucosal hematoma, a rare condition, was initially reported by Williams in 1957[1]. It is categorized into two types: spontaneous and traumatic[2,3]. The spontaneous type involves hemorrhage and hematoma formation caused by rupturing blood vessels in the submucosal layer, brought about by a sudden pressure increase due to such elements as nausea, vomiting, or coagulation abnormalities[2,4]. The traumatic type is generally considered to be caused by such factors as contaminants, endoscopies, and bougies[2]. Previous reports have shown that esophageal submucosal hematoma may develop following endovascular surgery (which requires antithrombotic therapy); one case developed after endovascular treatment for coil embolization for an unruptured cerebral aneurysm[5-7]. Most commonly, the hematoma is located in the distal esophagus (83% of cases), which is also the area least supported by the surrounding structures[2]. However, long segment involvement is common: the middle esophagus area is involved in 68% of cases, and the proximal esophagus area in 27% of cases[2,8]. Serious conditions are rare, with a better prognosis[2,5]. To date, there have been no reports of hemorrhagic shock due to esophageal submucosal hematoma along with Mallory-Weiss syndrome; therefore, we report the first such case, together with a brief review of literature.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 73-year-old Japanese female was admitted to our hospital for stent-assisted coil embolization under general anesthesia, for an unruptured cerebral aneurysm of the right internal carotid-posterior communicating artery.

History of present illness

The cerebral aneurysm was first detected thirteen years ago, and had been regularly checked on an annual basis. As it gradually grew, her doctor eventually advised her to have an operation, and she agreed. Starting 10 d prior to the surgery, 100 mg aspirin and 75 mg clopidogrel were administered orally. Laboratory data taken upon admission was within normal limits, including complete blood count, biochemistry, blood glucose, coagulation ability tests, and adenosine diphosphate. During surgery, a tracheal intubation was performed uneventfully after infusion administration of 50 mg rocuronium, followed by the uneventful insertion of a nasogastric (NG) tube, which was left open to room air until the completion of surgery; there was no spontaneous reflux of gastric contents. The patient underwent stent-assisted coil embolization of an unruptured cerebral aneurysm. At the beginning of surgery, 1000 units of heparin were administered intravenously. Activated clotting time was maintained for 2–2.5 times the control value. We removed the nasogastric tube without sustaining negative pressure, aspirating a small amount of gastric fluid that did not contain blood components. After surgery, we performed extubation uneventfully, with no nausea, vomiting, or strong cough occurring. Afterwards, 3.5 h after returning to the intensive care unit, the patient complained of chest discomfort, and vomited gastric acid that did not contain blood components. Shortly afterward, she vomited about 500 mL of fresh blood, and entered a state of hemorrhagic shock.

History of past illness

The patient’s medical history included essential hypertension and dyslipidemia. She was given 2 mg of temocapril hydrochloride for essential hypertension and 5 mg of atorvastatin calcium hydrate for dyslipidemia, on a regular basis, and her blood pressure, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and neutral fat were all well controlled.

Personal and family history

The patient had no history of smoking nor drinking alcohol. There were no abnormal findings on her regular medical exams. She had worked as a salesperson, but was currently unemployed. She had an allergy to alcohol. She did not need any assistance for everyday life activities. She had no family history of malignant disease or hereditary disease.

Physical examination

The patient was 155 cm tall and weighed 53 kg (body mass index: 22.1). Her vital signs and consciousness were as follows: blood pressure of 55/14 mmHg, heart rate of 155 irregular beats/min, body temperature of 36.2°C, blood oxygen saturation of 96% in ambient air, respiratory rate of 24/min, Glasgow Coma Scale score of 7 points (E3V1M3). A physical examination of the patient, including examination of her skin, revealed four abnormalities: hypotension, tachycardia, tachypnea, and disturbed consciousness.

Laboratory examinations

A routine laboratory examination, taken in a state of hemorrhagic shock, revealed an increased white blood cell count of 12.9 × 109/L and increased proportionate values for neutrophil of 83.4%, chloride of 110 mEq/L, plasma glucose of 156 mg/dL, and d-dimer of 1.1 μg/mL, and deceased proportionate values for lymphocyte of 13.4%, eosinophil of 0.4%, potassium of 3.3 mEq/L, and a red blood cell count of 3.13 × 1012/L. On the other hand, the other measured values, such as complete blood count, biochemistry, and coagulation, were normal (Table 1).

Table 1.

Routine laboratory examination of the patient, taken in a state of hemorrhagic shock

| Parameter (units) | Measured value | Normal value |

| White blood cell (109/L) | 12.9 | 3.6-8.9 |

| Neu (%) | 83.4 | 37-72 |

| Lym (%) | 13.4 | 25-48 |

| Mon (%) | 2.6 | 2-12 |

| Eos (%) | 0.4 | 1-9 |

| Bas (%) | 0.2 | 0-2 |

| Red blood cell (1012/L) | 3.13 | 3.8-5.04 |

| Platelet (109/L) | 221 | 153-346 |

| Aspartate transaminase (IU/L) | 14 | 5-37 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) | 12 | 6-43 |

| Lactic acid dehydrogenase (IU/L) | 164 | 119-221 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 159 | 110-348 |

| Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (IU/L) | 15 | 0-75 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.5 | 0.4-1.2 |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 7.4 | 6.5-8.5 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.5 | 3.8-5.2 |

| Creatine kinase (U/L) | 95 | 47-200 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 13 | 9-21 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.76 | 0.5-0.8 |

| Amylase (IU/L) | 98 | 43-124 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 140 | 135-145 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 3.3 | 3.5-5 |

| Chloride (mEq/L) | 110 | 96-107 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | 0.03 | 0-0.29 |

| Plasma glucose (mg/dL) | 156 | 65-109 |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time (Seconds) | 24.8 | 23-36 |

| Prothrombin time-international normalized ratio | 1.1 | 0.85-1.15 |

| D-dimer (μg/mL) | 1.1 | 0-1 |

Imaging examinations

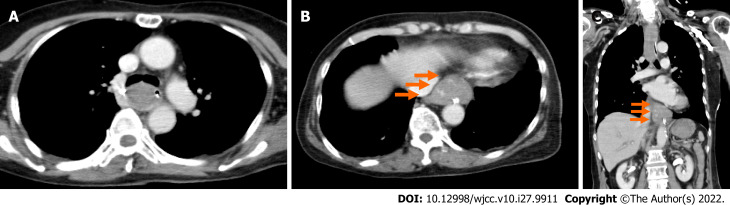

An electrocardiogram taken while the patient was in a state of hemorrhagic shock revealed no abnormalities compared to pre-surgery. We performed an enhanced computed tomography to assess her clinical condition, and it revealed a dilatation from the middle to lower esophagus, and that the esophageal lumen was almost entirely filled with hematomas (Figure 1A). In addition, an occupying lesion with a relatively clear boundary was observed under the mucosa at the esophagogastric (EG) junction, which had partial contrast effects (Figure 1B and C).

Figure 1.

Enhanced computerized tomography performed after the patient vomited approximately 500 mL of fresh blood and entered a state of hemorrhagic shock. A: Cross section. The mid thoracic esophagus is dilated, and the esophageal lumen is filled with massive hematomas; B: Cross section. An occupying lesion with a relatively clear boundary is observed under the mucosa just above the esophagogastric (EG) junction, with partial contrast effects (orange arrow); C: Coronal section. An occupying lesion with a relatively clear boundary is observed under the mucosa just above the EG junction, with partial contrast effects (orange arrow).

Further diagnostic work-up

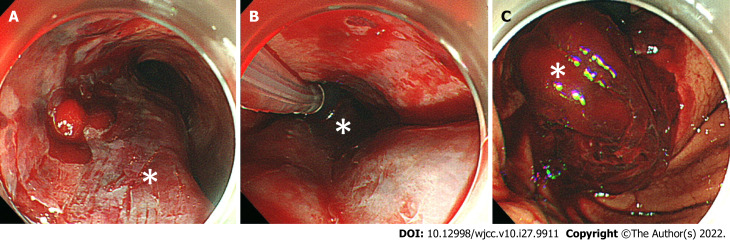

We administered 0.5 mg of atropine and 20 mg of omeprazole intravenously. In addition, we performed an emergency tracheal intubation using a 7.0 mm endotracheal tube and inserted a nasogastric tube, then continuously aspirated fresh blood from the nasogastric tube. We administered 1,000 ml of extracellular fluid and a transfusion of 4 units of red blood cells plus 4 units of fresh frozen plasma, but the hemorrhagic shock remained. We performed an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy for a detailed examination, together with the treatment for bleeding, and it revealed submucosal thickening from the mid to lower esophagus, which was due to the submucosal hematoma (Figure 2A). We also confirmed laceration of the gastric mucosa and a large amount of hematoma at the EG junction (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy images after hematemesis. A: Middle esophagus. A longitudinal extension of reddish mucosal thickening (white asterisk) and obstructing of the esophagus are confirmed; B: Middle esophagus, temporary compression hemostasis was performed with Sengstaken-Blakemore tube (white asterisk); C: Lower esophagus, massive hematoma and laceration of gastric mucosa together with bleeding are confirmed in the esophagogastric junction (white asterisk);.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Based on our findings, we determined a final diagnosis of submucosal esophageal hematoma and subsequent hemorrhagic shock due to Mallory-Weiss syndrome.

TREATMENT

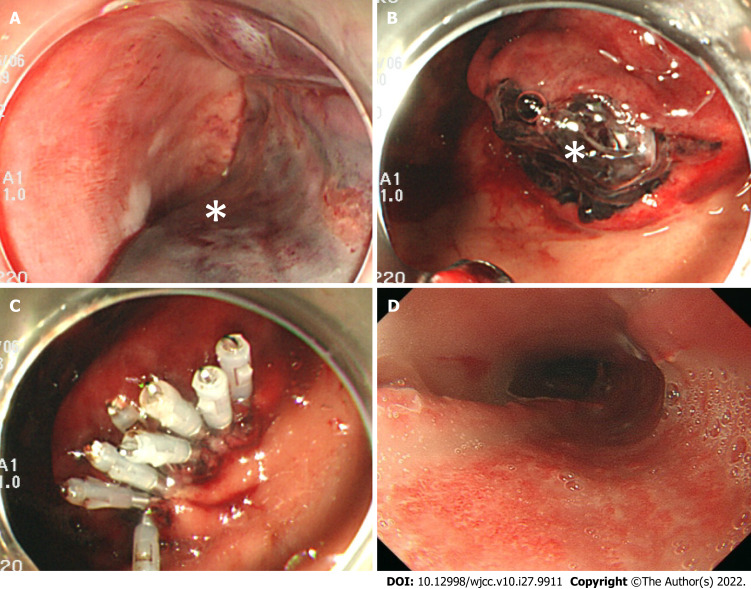

Ninety minutes after the onset of vomiting fresh blood, we confirmed that the patient’s hematemesis still continued, and the amount of bleeding reached a total of 1,500 mL. Furthermore, the level of hemoglobin decreased to 7.6 g/dL. We performed a temporary compression for hemostasis using a Sengstaken-Blakemore (S-B) tube, during which the esophageal balloon was inflated to 40 mmHg balloon pressure (Figure 2B). Two hours after the onset of hemorrhagic shock, she became hemodynamically stable. On postoperative day 1, we performed an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, and confirmed that there was no expansion of the hematoma nor recurrence of bleeding. We then removed the S-B tube (Figure 3A and B) and clipped the gastric mucosal laceration at the EG junction (Figure 3C). We started antiplatelet therapy on postoperative day 1, and removed the tracheal tube on postoperative day 3. An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy on postoperative day 10 revealed that the submucosal hematoma had been replaced by an esophageal ulcer (Figure 3D), and we started the patient’s oral intake on the same day.

Figure 3.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy images of postoperative course. A: One day after surgery, middle esophagus, hemostasis is confirmed; B: One day after surgery, Lower esophagus, Hematoma (white asterisk) and laceration of the gastric mucosa are confirmed in the esophagogastric (EG) junction; C: One day after surgery, EG junction, gastric mucosal laceration is clipped; D: 10 d after surgery, middle esophagus, the submucosal hematoma has been replaced by an esophageal ulcer.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

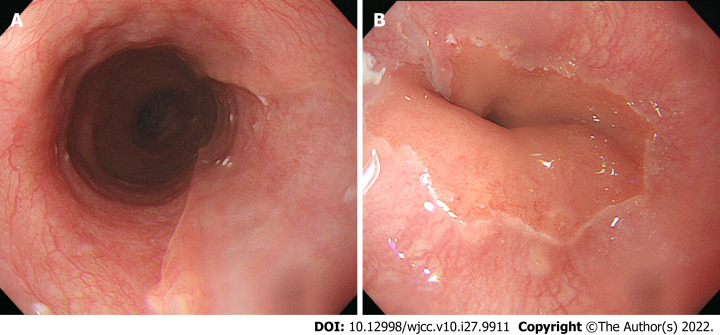

The patient made steady progress, and was discharged on postoperative day 33. An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy on postoperative day 60 revealed a scar from the esophageal ulcer (Figure 4A and B).

Figure 4.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy images 60 d after surgery. A: Middle esophagus, hemostasis has disappeared, and the endoscopy revealed normal findings; B: Esophagogastric junction, the esophageal ulcer has been replaced with a scar.

DISCUSSION

We present the first known case of report of hemorrhagic shock due to an esophageal submucosal hematoma along with Mallory-Weiss syndrome. In addition, submucosal esophageal hematoma after coiling embolization for unruptured cerebral aneurysm is very rare, so there is also value in reporting this event. We searched for other reports of esophageal submucosal hematomas using PubMed, J-STAGE, and Google Scholar, where we found 13 cases from January 1, 1998, through March 31, 2022 (Table 2)[2,5,7,9-16]. Of these, 9 (69%) were female, and the mean age was 69.5 years old (range: 32–85). Although the condition’s precise etiology remains unclear, the mechanism of the condition is considered to be vessel fragility with external factors, leading to submucosal bleeding and hematoma formation, followed by vessel rupture brought about by a sudden pressure increase caused by nausea; the hematoma was additionally enlarged by continuous bleeding caused by the antiplatelet effect of aspirin[2]. Generally, submucosal hematoma pathogenesis is considered to involve increased bleeding tendency caused by antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy[2,5,7]. Including this case, there are seven recorded cases in which esophageal submucosal hematomas occurred after surgery for unruptured cerebral aneurysms. In all cases, the patient received preoperative antiplatelet therapy and intraoperative anticoagulant therapy. In general, to prevent thrombotic complications, antiplatelet therapy is started preoperatively for coil embolizations for unruptured cerebral aneurysms, and anticoagulant therapy is started intraoperatively[6]. In our case, two antiplatelet drugs were administrated before the operation, and we administered heparin during surgery, with the estimated activated clotting time range around 200 s during operation. Therefore, preoperative antiplatelet therapy and intraoperative anticoagulant therapy are suspected to influence the occurrence of extensive esophageal submucosal hematomas, and the subsequent massive hematemesis with hemorrhagic shock. On the other hand, acute mucosal injury of the esophagus consists of esophageal hematoma along with Mallory-Weiss and Boerhaave's syndromes, and most frequently, a Mallory-Weiss tear is observed[2,15]. As an additional etiology, it is possible that the hematoma may have been related to inserting or removing the gastric tube[7].

Table 2.

Summary of prior reported cases of esophageal submucosal hematoma

|

Case No.

|

Year

|

Age

|

Sex

|

Underlying disease

|

Antiplatelet therapy

|

Anticoagulation therapy

|

Symptoms

|

Imaging findings

|

Complications

|

Prognosis

|

Prognosis time

|

Ref.

|

| 1 | 1998 | 64 | M | Ischemic heart disease | None | None | Retrostemal pain and coffee-ground vomitus | CT: A non-enhancing low-density submucosal columnar lesion in the mid- and lower oesophagus consistent with a submucosal haematoma. MRI: Intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images and hyperintense signal on T2-weighted images of this lesion. | None | Recovered | N/A | Yuen et al[9] |

| 2 | 2000 | 67 | M | Unruptured cerebral aneurysm | None | Heparin | Hematemesis | CT: A longitudinal water density mass without enhancement in the distal half of the esophageal lumen. It extended from about 3 cm below the level of the tracheal carina to the esophagocardiac junction. | None | Recovered | N/A | Yamashita et al[10] |

| 3 | 2001 | 84 | F | Dissecting aortic aneurysm | None | None | Chest discomfort and hematemesis | CT: Partial thickness of the esophageal wall which was not enhanced by contrast medium. | None | Recovered | N/A | Kise et al[11] |

| 4 | 2010 | 68 | F | Cerebrovascular disease | A | None | Hematemesis and retrostemal pain | None | None | Recovered | N/A | Zimmer et al[12] |

| 5 | 2013 | 32 | F | Neurofibromatosis type 1 | None | None | Sever central chest pain and interscapular pain associated with dysphagia | N/A | Massive bleeding with hypovolemic shock due to dissecting intramural hematoma of the esophagus | Dead | 6 hours | Pomara et al[13] |

| 6 | 2014 | 74 | M | Cerebral infarction and chronic hepatitis C | A | None | Hematemesis | None | None | Recovered | N/A | Oe et al[2] |

| 7 | 2016 | 70 | F | Unruptured cerebral aneurysm | A | Heparin | Epigastric pain and nausea | Unknown | Unknown | Recovered | N/A | Fujimoto et al[7] |

| 8 | 2017 | 81 | M | Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura | None | None | Chest pain and dysphagia | CT: A 17-cm long segment of homogeneous, soft tissue like density in the mid-to-distal esophagus with smooth eccentric configuration causing luminal narrowing. The maximal esophageal wall measures approximately 26 mm in thickness. Upper gastrointestinal contrast study: A large eccentric luminal narrowing caused by a mural wall compression of the mid-to-distal esophagus, confirming the submucosal hematoma. | None | Recovered | N/A | Sharma et al[14] |

| 9 | 2017 | 85 | F | Atrial fibrillation | None | Dabigatran | Hemoptysis | Unknown | Unknown | Recovered | N/A | Trip et al[15] |

| 10 | 2017 | 75 | F | Unruptured cerebral aneurysm | A+C | Heparin + Argatroban | Hematemesis | CT: Dilatation of the entire esophagus and the soft tissue shadow filled on the dorsal side that was ventrally displacing the lumen. | None | Recovered | N/A | Ito et al[16] |

| 11 | 2019 | 65 | F | Unruptured cerebral aneurysm | A | Heparin | Hematemesis | Unknown | Unknown | Recovered | N/A | Fujii et al[5] |

| 12 | 2019 | 73 | F | Unruptured cerebral aneurysm | A+C | Heparin | Epigastric pain and hematemesis | Unknown | Unknown | Recovered | N/A | Fujii et al[5] |

| 13 | 2019 | 65 | F | Unruptured cerebral aneurysm | A+C | Heparin | Epigastric pain | Unknown | Unknown | Recovered | N/A | Fujii et al[5] |

| 14 | 2020 | 73 | F | Unruptured cerebral aneurysm | A+C | Heparin | Hematemesis | CT: A dilatation from the middle to lower esophagus, and that the esophageal lumen was almost entirely filled with hematomas. An occupying lesion with a relatively clear boundary was observed under the mucosa at the esophagogastric junction, which had partial contrast effects. | None | Recovered | N/A | N/A |

CT: Computed tomography; M: Male; F: Female; A: Aspirin; T: Ticlopidine; C: Clopidogrel; N/A: Not applicable.

Ordinarily, the clinical picture is dominated by severe chest pain and/or discomfort as the predominant complaints; this is often misleading, resulting in erroneous diagnoses such as aortic dissection or ischemic heart disease[2,8,15,17]. One clue that can help suggest that clinicians consider esophageal diseases is that many patients ultimately complain of back pain, generally with sudden onset, which is associated with dysphagia, hemoptysis, and hematemesis[2,4]. All cases shown in Table 2 were acute onset, and the initial symptoms were chest pain and odynophagia in 11 patients (68.8%), hematemesis in 10 patients (62.5%), and dysphagia in 2 patients (12.5%). Based on these, the symptoms found in this case were comparable to previous reports.

Confirmation of diagnosis requires a barium swallow or an endoscopy, informed by the characteristic features described[3]. In our case, we made the diagnosis through an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Medical treatments have included temporarily ceasing or reducing antiplatelet therapy; every case was discharged with the symptoms cured, and with gastric intestinal fiber appearing in computed tomography imagery[5]. In most cases, conservative management of esophageal hematomas accompanied by Mallory-Weiss syndrome is adequate[2,4,15]. In our case, we were able to control bleeding through S-B tube compression. Therefore, if conservative treatment proves unfeasible for stopping bleeding for esophageal hematoma along with Mallory-Weiss syndrome, a temporary S-B tube compression may be useful. The prognosis is reportedly good, and conservative treatment leads to improvement for many patients[2,5]. However, a shallow ulcer forms across a wide area after the mucous membrane covering the hematoma peels away, and scars from the ulcer appear after approximately a month[2,18]. This case study has a limitation: it only reviews a single case report and case series of esophageal submucosal hematoma. Therefore, the actual situation and nature of the disease may differ from the results of this literature review, as a result of reporting bias. Additional studies are needed to further evaluate the impact of background and clinical presentation, treatment patterns, and outcomes of the disease.

CONCLUSION

We present the first known case of hemorrhagic shock due to esophageal submucosal hematoma along with Mallory-Weiss syndrome. Our primary finding is that clinicians should bear in mind the risk of esophageal submucosal hematoma during the postoperative management, after patients undergo endovascular surgery for unruptured cerebral aneurysm. As life expectancies rise, more and more people take antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants; clinicians should also be aware of this rare condition.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient and his family for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. Both written and verbal informed consent were obtained from the patient and his family for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: May 14, 2022

First decision: July 29, 2022

Article in press: August 17, 2022

Specialty type: Emergency medicine

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ye Y, China; Zhou B, China S-Editor: Xing YX L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX

Contributor Information

Jiro Oba, Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Juntendo University Nerima Hospital, Nerima-ku 177-8521, Tokyo, Japan. j.oba@juntendo-nerima.jp.

Daisuke Usuda, Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Juntendo University Nerima Hospital, Nerima-ku 177-8521, Tokyo, Japan.

Shiho Tsuge, Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Juntendo University Nerima Hospital, Nerima-ku 177-8521, Tokyo, Japan.

Riki Sakurai, Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Juntendo University Nerima Hospital, Nerima-ku 177-8521, Tokyo, Japan.

Kenji Kawai, Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Juntendo University Nerima Hospital, Nerima-ku 177-8521, Tokyo, Japan.

Shun Matsubara, Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Juntendo University Nerima Hospital, Nerima-ku 177-8521, Tokyo, Japan.

Risa Tanaka, Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Juntendo University Nerima Hospital, Nerima-ku 177-8521, Tokyo, Japan.

Makoto Suzuki, Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Juntendo University Nerima Hospital, Nerima-ku 177-8521, Tokyo, Japan.

Hayabusa Takano, Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Juntendo University Nerima Hospital, Nerima-ku 177-8521, Tokyo, Japan.

Shintaro Shimozawa, Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Juntendo University Nerima Hospital, Nerima-ku 177-8521, Tokyo, Japan.

Yuta Hotchi, Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Juntendo University Nerima Hospital, Nerima-ku 177-8521, Tokyo, Japan.

Kenki Usami, Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Juntendo University Nerima Hospital, Nerima-ku 177-8521, Tokyo, Japan.

Shungo Tokunaga, Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Juntendo University Nerima Hospital, Nerima-ku 177-8521, Tokyo, Japan.

Ippei Osugi, Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Juntendo University Nerima Hospital, Nerima-ku 177-8521, Tokyo, Japan.

Risa Katou, Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Juntendo University Nerima Hospital, Nerima-ku 177-8521, Tokyo, Japan.

Sakurako Ito, Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Juntendo University Nerima Hospital, Nerima-ku 177-8521, Tokyo, Japan.

Kentaro Mishima, Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Juntendo University Nerima Hospital, Nerima-ku 177-8521, Tokyo, Japan.

Akihiko Kondo, Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Juntendo University Nerima Hospital, Nerima-ku 177-8521, Tokyo, Japan.

Keiko Mizuno, Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Juntendo University Nerima Hospital, Nerima-ku 177-8521, Tokyo, Japan.

Hiroki Takami, Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Juntendo University Nerima Hospital, Nerima-ku 177-8521, Tokyo, Japan.

Takayuki Komatsu, Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Juntendo University Nerima Hospital, Nerima-ku 177-8521, Tokyo, Japan; Faculty of Medicine, Juntendo University, Bunkyo-ku 113-8421, Tokyo, Japan.

Tomohisa Nomura, Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Juntendo University Nerima Hospital, Nerima-ku 177-8521, Tokyo, Japan.

Manabu Sugita, Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Juntendo University Nerima Hospital, Nerima-ku 177-8521, Tokyo, Japan.

References

- 1.Williams B. Case report; oesophageal laceration following remote trauma. Br J Radiol. 1957;30:666–668. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-30-360-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oe S, Watanabe T, Kume K, Shibata M, Hiura M, Yoshikawa I, Harada M. A case of idiopathic gastroesophageal submucosal hematoma and its disappearance observed by endoscopy. J UOEH. 2014;36:123–128. doi: 10.7888/juoeh.36.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freeman AH, Dickinson RJ. Spontaneous intramural oesophageal haematoma. Clin Radiol. 1988;39:628–634. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(88)80076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steadman C, Kerlin P, Crimmins F, Bell J, Robinson D, Dorrington L, McIntyre A. Spontaneous intramural rupture of the oesophagus. Gut. 1990;31:845–849. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.8.845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujii T, Oishi H, Hara A, Teranishi K, Yatomi K, Yamamoto M. Three Cases of Esophageal Submucosal Hematoma after Coiling for Unruptured Cerebral or Intracranial Aneurysms. No Shinkei Geka. 2019;47:551–558. doi: 10.11477/mf.1436203980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamada NK, Cross DT 3rd, Pilgram TK, Moran CJ, Derdeyn CP, Dacey RG Jr. Effect of antiplatelet therapy on thromboembolic complications of elective coil embolization of cerebral aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:1778–1782. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujimoto Y, Shirozu K, Shirozu N, Akiyoshi K, Nishimura A, Kawasaki S, Motoyama Y, Kandabashi T, Iihara K, Hoka S. Esophageal Submucosal Hematoma Possibly Caused by Gastric Tube Insertion Under General Anesthesia. A A Case Rep. 2016;7:169–171. doi: 10.1213/XAA.0000000000000376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hagel J, Bicknell SG, Haniak W. Imaging management of spontaneous giant esophageal intramural hematoma. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2007;58:76–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuen EH, Yang WT, Lam WW, Kew J, Metreweli C. Spontaneous intramural haematoma of the oesophagus: CT and MRI appearances. Australas Radiol. 1998;42:139–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.1998.tb00591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamashita K, Okuda H, Fukushima H, Arimura Y, Endo T, Imai K. A case of intramural esophageal hematoma: complication of anticoagulation with heparin. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:559–561. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.108664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kise Y, Suzuki R, Shimada H, Tanaka H, Oshiba G, Chino O, Makuuchi H. Idiopathic submucosal hematoma of esophagus complicated by dissecting aneurysm, followed-up endoscopically during conservative treatment. Endoscopy. 2001;33:374–378. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-13684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zimmer V, Lammert F. Clinical images: Multiple esophageal submucosal hematomas. CMAJ. 2010;182:62. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pomara C, Bello S, D'Errico S, Greco M, Fineschi V. Sudden death due to a dissecting intramural hematoma of the esophagus (DIHE) in a woman with severe neurofibromatosis-related scoliosis. Forensic Sci Int. 2013;228:e71–e75. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma K, Wang Y. Submucosal esophageal hematoma precipitated by chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Radiol Case Rep. 2017;12:278–280. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2017.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trip J, Hamer P, Flint R. Intramural oesophageal haematoma-a rare complication of dabigatran. N Z Med J. 2017;130:80–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ito S, Iwata S, Kondo I, Iwade M, Ozaki M, Ishikawa T, Kawamata T. Esophageal submucosal hematoma developed after endovascular surgery for unruptured cerebral aneurysm under general anesthesia: a case report. JA Clin Rep. 2017;3:54. doi: 10.1186/s40981-017-0124-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kerr WF. Spontaneous intramural rupture and intramural haematoma of the oesophagus. Thorax. 1980;35:890–897. doi: 10.1136/thx.35.12.890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagai T, Torishima R, Nakashima H, Uchida A, Okawara H, Suzuki K, Sato R, Murakami K, Fujioka T. Spontaneous esophageal submucosal hematoma in which the course could be observed endoscopically. Intern Med. 2004;43:461–467. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.43.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]