ABSTRACT

Zoonotic coronaviruses represent an ongoing threat to public health. The classical porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) first appeared in the early 1970s. Since 2010, outbreaks of highly virulent PEDV variants have caused great economic losses to the swine industry worldwide. However, the strategies by which PEDV variants escape host immune responses are not fully understood. Complement component 3 (C3) is considered a central component of the three complement activation pathways and plays a crucial role in preventing viral infection. In this study, we found that C3 significantly inhibited PEDV replication in vitro, and both variant and classical PEDV strains induced high levels of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) in Huh7 cells. However, the PEDV variant strain reduces C3 transcript and protein levels induced by IL-1β compared with the PEDV classical strain. Examination of key molecules of the C3 transcriptional signaling pathway revealed that variant PEDV reduced C3 by inhibiting CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBP-β) phosphorylation. Mechanistically, PEDV nonstructural protein 1 (NSP1) inhibited C/EBP-β phosphorylation via amino acid residue 50. Finally, we constructed recombinant PEDVs to verify the critical role of amino acid 50 of NSP1 in the regulation of C3 expression. In summary, we identified a novel antiviral role of C3 in inhibiting PEDV replication and the viral immune evasion strategies of PEDV variants. Our study reveals new information on PEDV-host interactions and furthers our understanding of the pathogenic mechanism of this virus.

IMPORTANCE The complement system acts as a vital link between the innate and the adaptive immunity and has the ability to recognize and neutralize various pathogens. Activation of the complement system acts as a double-edged sword, as appropriate levels of activation protect against pathogenic infections, but excessive responses can provoke a dramatic inflammatory response and cause tissue damage, leading to pathological processes, which often appear in COVID-19 patients. However, how PEDV, as the most severe coronavirus causing diarrhea in piglets, regulates the complement system has not been previously reported. In this study, for the first time, we identified a novel mechanism of a PEDV variant in the suppression of C3 expression, showing that different coronaviruses and even different subtype strains differ in regulation of C3 expression. In addition, this study provides a deeper understanding of the mechanism of the PEDV variant in immune escape and enhanced virulence.

KEYWORDS: C/EBP-β, complement C3, NSP1, PEDV, replication

INTRODUCTION

The complement system is an important part of the immune system in organisms. As a set of biochemical pathways, it plays a role in killing pathogens and attacking target cells (1). The complement system links innate and adaptive immunity by a variety of pathways, including regulating immune effectors, enhancing humoral immunity, and affecting cellular immune function (2, 3). The complement system is a set of plasma proteins that sense and respond to invading pathogens (1). Among them, complement component 3 (C3) plays a central role in classical, alternative, and lectin complement activation pathways (4, 5). C3 has a wide range of roles, not only playing a role in clearing pathogens but also directly participating in the immune response and controlling tumor progression (6, 7). Meanwhile, the centrality of C3 in immune surveillance makes it a target for immune escape by pathogenic microorganisms (2, 8, 9).

As a member of the acute-phase proteins, C3 expression levels are either positively or negatively regulated by inflammatory cytokines (10). Interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and glucocorticoids are the positive regulators (11, 12). Previous study had shown that IL-1β and IL-6 synergistically enhance mRNA levels and protein secretion of C3 (13). IL-1β upregulates C3 expression through the activation of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBP-β) in a p38-mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38-MAPK)-dependent manner (14). C/EBP-β, a member of the leucine zipper (bZIP) family, is expressed as three alternate translation products (15) as follows: the 49-kDa liver-enriched activating protein 1 (LAP1), 45-kDa LAP2, and a 20-kDa liver-enriched inhibitory protein (LIP) (16). The phosphorylation of LAP2 at Thr235 in the MAPK consensus site is required for activation of C3 promoter in response to IL-1β, and LIP has no effect on C3 promoter activation (14).

Coronaviruses are enveloped, positive-sense RNA viruses that infect a variety of hosts, including pigs, camels, bats, cats, and humans (17). Extensive research about coronavirus and the complement system have been conducted, especially after the emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). SARS-CoV-2 infection activates the complement cascade, but the complement system plays an ambiguous role during SARS-CoV-2 infection (18–20). Accumulating evidence indicates that SARS-CoV infection can systemically activate the complement cascade, influencing disease exacerbation (19). The swine coronavirus, porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV), first discovered in 1971, is an ancient virus to which pigs are specifically susceptible (21). Infection with this virus causes porcine epidemic diarrhea (PED), a highly infectious digestive tract disease that can cause vomiting and diarrhea in pigs and has a high mortality rate in piglets (22, 23). The classical PEDV has gradually become an epidemic in European and Asian countries since it was first reported. since 2010, recurrent epidemics caused by the highly virulent PEDV variants have swept the world again (23–27) and led to 100% mortality in piglets aged 7 days or younger (28). The recent and rapid global spread of highly pathogenic PEDV variants highlights a critical health threat and demonstrates the resources needed to understand the virus and its potential pathogenicity in mammals.

Current studies have shown that PEDV infections have the potential to suppress innate immunity, especially the production of interferons, thereby escaping their antiviral effects (29). At the same time, PEDV infection provokes the production of multiple inflammatory factors, including IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α (30). One study measured the levels of the major complement components in porcine serum after PEDV infection and found a decreasing trend of C3, C6, and CFB (31), but the molecular mechanism behind this remains unclear.

In this study, we found that infection with the variant or classical PEDV strain induced different expression levels of C3. Furthermore, nonstructural protein 1 (NSP1) of the variant strain downregulated the C3 transcript levels by inhibiting the phosphorylation of C/EBP-β, thus escaping the antiviral effects of C3. This study identified a novel strategy by which PEDV variant strains escape innate immunity, enriching our understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms of PEDV.

RESULTS

Variant PEDV inhibits C3 expression.

A single-cell RNA sequencing of jejunums from piglets infected with PEDV variant strain AH2012/12 (GenBank accession number KU646831) was performed before (GEO accession number GSE175411; data not shown), and a new transcriptional analysis of complement components revealed that the transcripts of C3, C5, and C6 were reduced in the enterocyte cells after PEDV infection (Fig. 1A). The fold change analysis revealed the most significant reduction, of approximately 50%, in C3 (Fig. 1B). In vitro, IPEC-J2 cells were used to verify the change in single-cell RNA sequencing, and the results showed that both mRNA and protein levels of C3 were decreased during the phase of AH2012/12-infected IPEC-J2, with the significant differences at 24 and 36 h postinfection (hpi) (Fig. 1C and D).

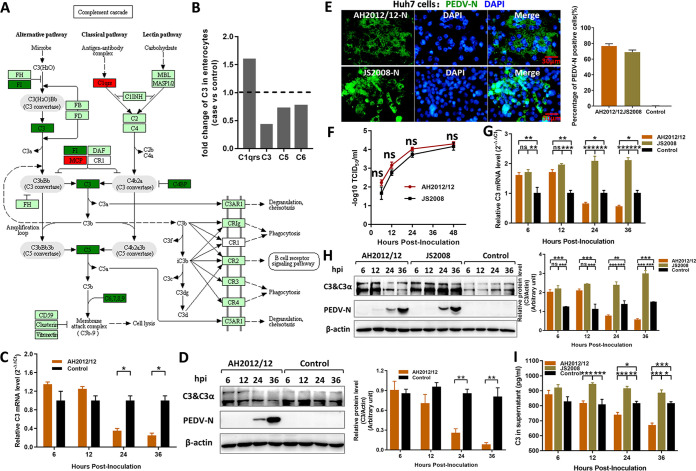

FIG 1.

PEDV variant decreases C3 expression in vitro. (A) Single-cell sequencing of the jejunum from piglets infected with PEDV variant strain AH2012/12 was previously performed, and the complement cascade was determined using intestinal enterocytes obtained from the virus-infected versus control groups. Dark green and dark red indicate significantly downregulated and upregulated genes, respectively. (B) Fold changes of major complement components were analyzed according to the transcriptome data. In vitro, variant strain AH2012/12 was inoculated into IPEC-J2 cells at 1 MOI, and the infected cells were analyzed using the transcript level for C3 mRNA by relative qRT-PCR (C) and the protein level for C3 and PEDV-N proteins by Western blotting (D). Huh7 cells were inoculated with two PEDV strains at 1 MOI. The susceptibilities of Huh7 cells to PEDV strains were detected using IFs and flow cytometry at 24 hpi (E) and growth curve assays (F). The infected Huh7 cells were analyzed to determine the transcript level for C3 mRNA (G) and the protein levels for C3 and PEDV-N proteins (H). (I) The content of C3 in the supernatant was determined by an ELISA kit. The relative expression levels of target proteins according to the grayscale of β-actin in cells were also assayed. For the data, two-way ANOVA multiple comparisons tests were used to compare the data from different treatment groups. Values are means ± SD. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; n = 3. The error bars indicate the standard deviation.

To determine whether there are differences in C3 expression among different strains, especially between classical low-virulence and variant high-virulence strains, a classical strain JS2008 (GenBank accession number KC109141) was selected to compare with AH2012/12. However, there is an extremely low infectivity of JS2008 to IPEC-J2 cells. So, the Huh7 cells, a commonly used cell line for complement research, was used to perform the subsequent infection experiments. As shown in Fig. 1E, at 24 hpi, the indirect immunofluorescences (IFs) showed that AH2012/12 and JS2008 can both efficiently infect Huh7 cells with above 70% PEDV-positive cells, and infection of Huh7 cells with AH2012/12 also requires trypsin, presenting the cytopathic effect (CPE) of syncytia formation. The growth curves of viruses in Huh7 cells showed that the AH2012/12 replicative capacity was slightly higher than that of JS2008 with no significant difference, and the titers of both strains were approximately 104 median tissue culture infective dose (TCID50)/mL at 48 hpi (Fig. 1F). After infections with these two different PEDV strains in Huh7, both mRNA and protein levels of C3 were increased significantly during the early stages of infection. Subsequently, C3 expression levels decreased in the group infected with AH2012/12 at 24 and 36 hpi, whereas the C3 remained at a high level in the JS2008-infected group (Fig. 1G and H). In addition, compared with those of JS2008, the protein levels of C3 were significantly decreased in the supernatants of AH2012/12-infected cells at 24 and 36 hpi (Fig. 1I).

C3 inhibits PEDV replication.

C3 plays a pivotal role in complement activation, and there is no report about C3 on PEDV replication. A eukaryotic expression vector that expresses porcine C3 protein tagged with hemagglutinin (HA)-tag at the C terminus (pLV-pC3/HA) was constructed and used to assay the antiviral effect of C3 on PEDV replication. As shown in Fig. 2A, the levels of N proteins of AH2012/12 and JS2008 in pLV-pC3/HA-transfected groups were both significantly lower than those in the control pLV-Exp-transfected groups. The levels of viral mRNA in cells and the titers in supernatants of the pLV-pC3/HA-transfected groups were also significantly lower than those of the pLV-Exp-transfected groups (Fig. 2B and C). In addition, the results showed that C3 overexpression significantly inhibited PEDV replication with a greater effect on JS2008.

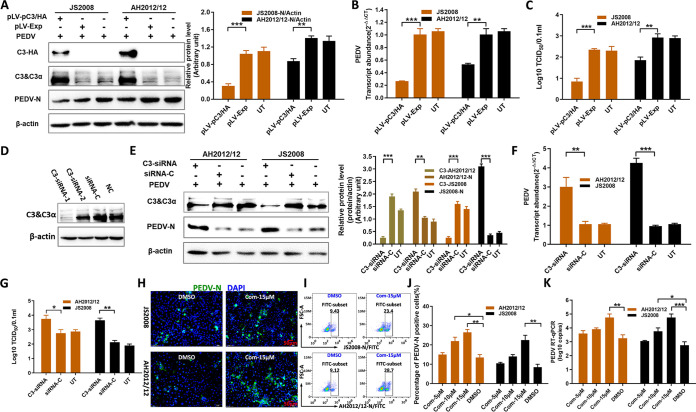

FIG 2.

C3 significantly inhibits PEDV replication. Huh7 cells were transfected with pLV-pC3/HA or pLV-Exp at 1.5 μg/well in a 24-well plate. After 24 h, all cells were inoculated with AH2012/12 or JS2008 at 1 MOI for another 24 h. Then, the infected cells were analyzed to determine the protein expression levels for C3 chains, C3-HA and PEDV-N proteins (A), the transcript level for PEDV mRNA (B), and the virus titers of the supernatants (C). (D) In the C3 knockdown assays, two synthetic C3-siRNAs were transfected into Huh7 cells, and the C3 expression levels were analyzed. Subsequently, cells were transfected with C3-siRNA-1 and siRNA-C for 24 h, and then all cells were inoculated with AH2012/12 or JS2008 for another 24 h. The infected cells were analyzed to determine the protein levels of C3 and PEDV-N (E), PEDV mRNA (F), and the virus titers of supernatants (G). Additionally, C3-AH2012/12 and C3-JS2008 in panel E represent the relative expression levels of protein C3 according to the grayscale of β-actin with different treatments in the AH2012/12- and JS2008-infected groups, respectively. Huh7 cells were inoculated with Com at different concentrations for 6 h, and all cells were inoculated with AH2012/12 or JS2008 at 0.1 MOI for another 24 h. The infected cells were detected by using IFs (H), flow cytometry (I and J), and the gene copy numbers of PEDV (K). For the data, two-way ANOVA multiple comparisons tests were used to compare the data from different treatment groups. Values are means ± SD. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; n = 3. The error bars indicate the standard deviation.

The effect of knockdown of C3 on virus replication was determined further. Two specific small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) to C3 (C3-siRNAs) were tested, and C3-siRNA-1 transfected significantly downregulated the levels of C3 protein in Huh7 cells (Fig. 2D). Subsequently, Huh7 cells were transfected with C3-siRNA-1 or siRNA-C. As shown in Fig. 2E, compared with those of the siRNA-C treatment groups, the expression levels of AH2012/12 and JS2008 N proteins in the C3-siRNA treatment groups were significantly increased. What is more, the abundances of viral gene transcripts in cells and virus titers in supernatants of the C3-siRNA groups were both significantly higher than those in the siRNA-C groups (Fig. 2F and G). In addition, the effects of C3-specific inhibitor compstatin (Com) (32) on viral replication were also tested. The IFs and flow cytometry revealed that the number of PEDV-positive cells was significantly higher after pretreatment with Com (Fig. 2H and I). What is more, the number of PEDV-positive cells and replication levels of PEDV were inversely dose dependent with the concentrations of Com (Fig. 2J and K). These results confirmed the antiviral activity of C3 on PEDV infection.

Variant PEDV suppresses C3 expression induced by IL-1β.

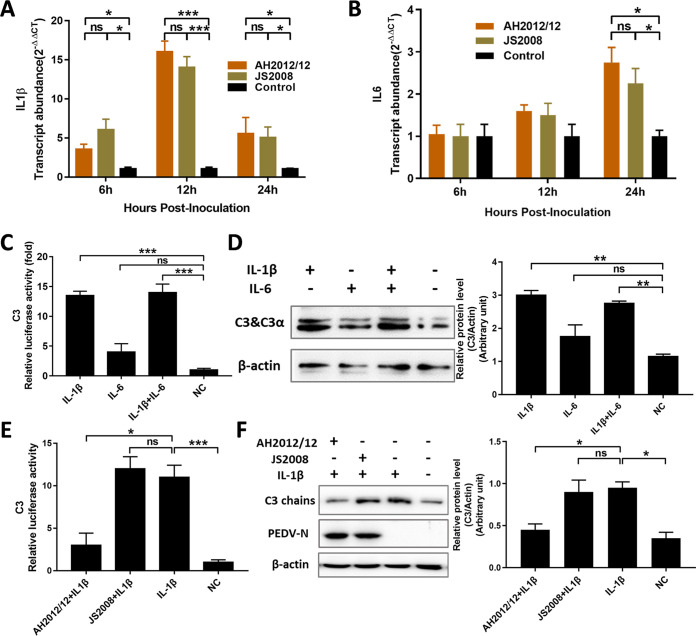

Previous studies have reported that IL-1β and IL-6 can activate C3 promoter activity and upregulate C3 expression (14). In this study, the transcript levels of IL-1β and IL-6 in Huh7 cells induced by PEDV-infections were measured, and the results showed that both PEDV strains AH2012/12 and JS2008 significantly upregulated the transcripts of IL-1β and IL-6 (Fig. 3A and B). The effects of IL-1β and IL-6 on the C3 promoter activity and expression in the Huh7 cells were also determined, and the results showed that C3 promoter activities and expression levels were both significantly upregulated in the IL-1β pretreatment groups compared with the control groups (Fig. 3C and D). The induction of C3 by IL-6 was not significant, and there was no synergistic effect of IL-1β and IL-6 on inducing C3 expression. To further determine the effects of different PEDV strains on IL-1β-induced C3 expression, Huh7 cells were inoculated with IL-1β together with PEDV strains AH2012/12 or JS2008 for 24 h. Then, C3 expression levels were determined, and the results showed that, in the variant PEDV AH2012/12-infected group, the promoter activities as well as the protein expression levels of C3 were significantly lower than those of the classical PEDV strain JS2008-infected group (Fig. 3E and F). The above results indicated that variant PEDV strain AH2012/12 downregulates the C3 expression induced by IL-1β.

FIG 3.

PEDV variant suppresses C3 expression induced by IL-1β. The transcript levels of IL-1β (A) and IL-6 (B) were determined in cells inoculated with AH2012/12 or JS2008 at different time points. The effects of IL-1β and/or IL-6 on C3 promoter activities (C) and expressions (D) were detected in Huh7 cells. When the effect of viral infection on IL-1β-induced C3 was determined, virus (MOI = 1) and cytokines were inoculated into cells together for 24 h. Then, all of the cells were lysed to assay the C3 luciferase activities (E) and the expression levels of C3 and PEDV-N proteins (F). The relative expression levels of target proteins according to the grayscale of β-actin in cells were also assayed. For panels A and B, two-way ANOVA multiple comparisons tests were used to compare the data from different treatment groups; for panels C to F, analyses were performed by Student’s t test. Values are means ± SD. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; n = 3. The error bars indicate the standard deviation.

Variant PEDV suppresses C3 transcription by inhibiting C/EBP-β phosphorylation.

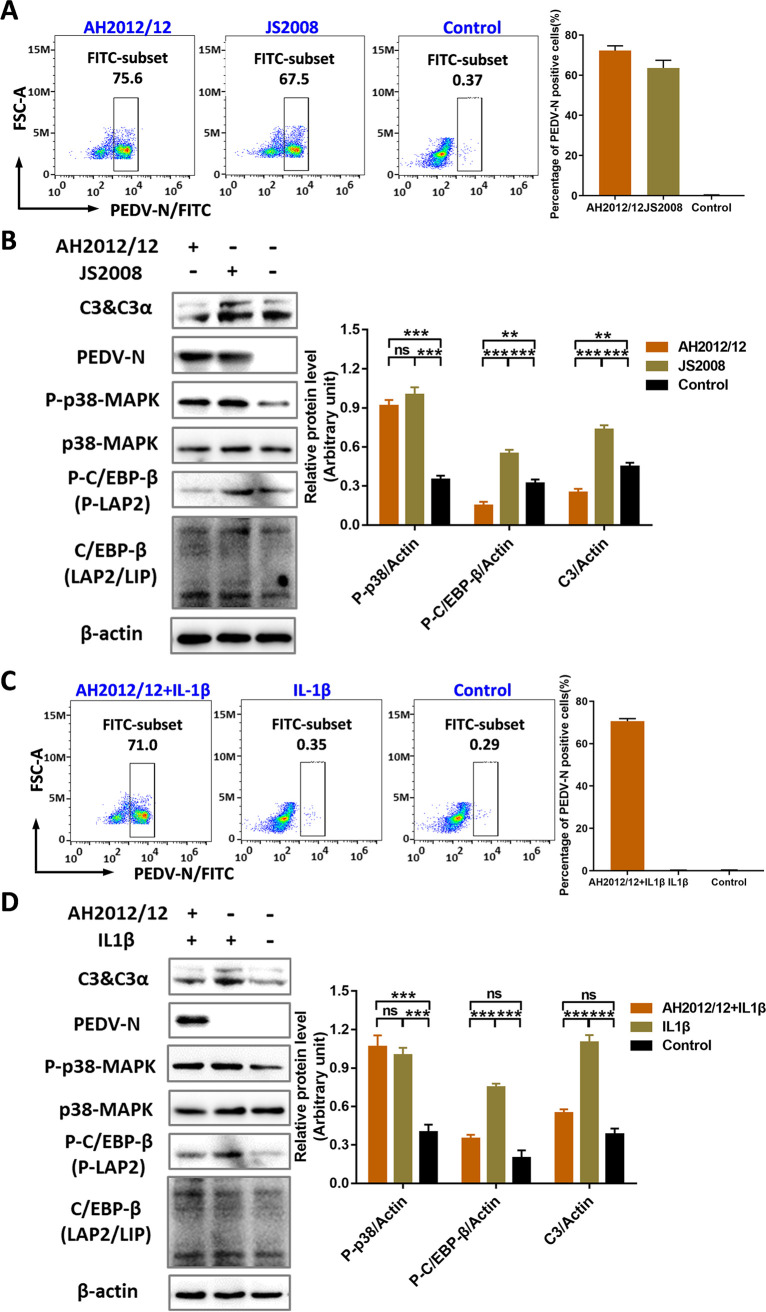

IL-1β regulates C3 expression through the activation of C/EBP in a p38-MAPK-dependent manner (14). The key molecules of the signaling pathway involved in the inhibition of C3 expression by variant PEDV were determined further. First, the infection rates of the Huh7 cells by AH2012/12 and JS2008 were approximately 70% at 24 hpi (Fig. 4A). Under this condition, the expression and phosphorylation levels of p38-MAPK and C/EBP-β were measured in Huh7 cells infected with viruses. As shown in Fig. 4B, both strains had no effect on the expression of p38-MAPK, and both induced the phosphorylation of p38-MAPK with no significant difference. For C/EBP-β, compared with that of the control group, JS2008 infection significantly upregulated the phosphorylation of C/EBP-β. However, the AH2012/12 infection significantly inhibited phosphorylation of C/EBP-β.

FIG 4.

PEDV variant suppresses C3 transcription by inhibiting C/EBP-β phosphorylation. (A) Huh7 cells were inoculated with 1 MOI of AH2012/12 or JS2008, and at 24 hpi, the percentages of PEDV-positive cells were determined by flow cytometry. (B) Then, all cells were lysed to assay the expression levels of different proteins. (C) PEDV and IL-1β were inoculated into cells together for 24 h, and the percentages of PEDV-positive cells were determined by flow cytometry. (D) Then, all cells were lysed to assay the expression levels of different proteins. The relative expression levels of target proteins according to the grayscale of β-actin in cells were also assayed. For panels B and D, two-way ANOVA multiple comparisons tests were used to compare the data from different treatment groups. Values are means ± SD. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; n = 3. The error bars indicate the standard deviation.

To define the inhibitory effect of AH2012/12 on C/EBP-β phosphorylation further, IL-1β was used as a positive inducer. As shown in Fig. 4C, the rate of AH2012/12-infected Huh7 cells was more than 75% at 24 hpi, and compared with the cells treated with only IL-1β, the C/EBP-β phosphorylation level was significantly decreased in AH2012-inoculated cells with the downregulation of C3 expression (Fig. 4D). The above results indicated that variant PEDV decreases C3 expression by inhibiting C/EBP-β phosphorylation.

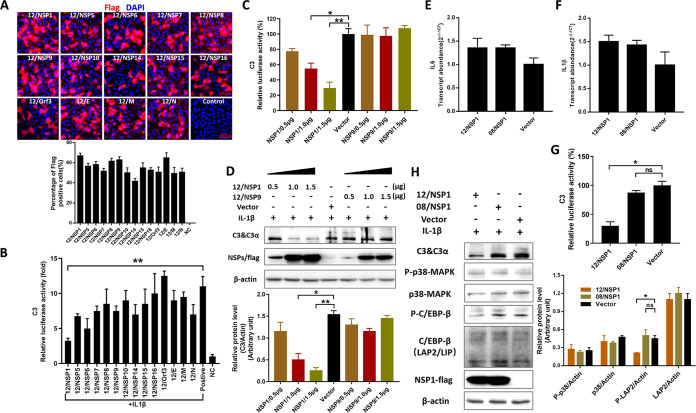

NSP1 of variant PEDV inhibits the phosphorylation of C/EBP-β.

To identify which viral protein inhibits C/EBP-β phosphorylation, 14 individual PEDV nonstructural and structural protein expression vectors were transfected into Huh7 cells to assay the effects on C3 promoter activity. The transfection efficiencies were first assayed, and the results showed that about 60% of the cells were positive for viral proteins (Fig. 5A). Luciferase assays showed that the NSP1 derived from AH2012/12 had the most significant inhibition on C3 promoter activity compared with the IL-1β-positive treated group (Fig. 5B). Dose-dependent tests showed that increased expression of AH2012/12 NSP1 led to more pronounced inhibitions of C3 promoter activities (Fig. 5C) and protein expressions (Fig. 5D), whereas the AH2012/12 NSP9, which was considered a control sample, had no effect on C3. Moreover, the NSP1 proteins of AH2012/12 and JS2008 had no effect on the transcript levels of IL-6 and IL-1β (Fig. 5E and F). In addition, comparison of NSP1 proteins from both strains revealed that only AH2012/12 NSP1 exerted a significant inhibitory effect on C3 promoter activity induced by IL-1β (Fig. 5G). To verify the effect of NSP1 on C/EBP-β activity, Huh7 cells were transfected for 24 h with the NSP1 proteins of AH2012/12 and JS2008, respectively. Then, IL-1β was added for another 24 h, and the results showed that the AH2012/12 NSP1-transfected group had significantly downregulated phosphorylation of C/EBP-β and expression of C3 compared with those of the JS2008 NSP1 group (Fig. 5H).

FIG 5.

NSP1 of the PEDV variant inhibits the phosphorylation of C/EBP-β. Huh7 cells were transfected with the C3 promoter luciferase reporter constructs, alone or together with AH2012/12 nonstructural or structural protein-expressed vectors, and then treated with IL-1β. A portion of the cells were fixed and the expression levels of viral proteins were determined using IFs and flow cytometry (A), and another portion of the cells were lysed and the C3 luciferase activities were measured (B). 12/NSP1 or 12/NSP9 with different concentrations were transfected into Huh7 cells, treated with IL-1β. Then, the C3 luciferase activities (C) and the expression levels of C3 protein (D) were assayed. Recombinant vectors 12/NSP1 or 08/NSP1 were transfected into Huh7 cells, and the transcript levels of IL-6 (E) and IL-1β (F) were determined. Huh7 cells were transfected with 12/NSP1, 08/NSP1, or empty vector. After 24 h, all cells were inoculated with IL-1β for another 24 h and were then lysed to assay the C3 luciferase activities (G) and the expression levels of different proteins (H). The relative expression levels of target proteins according to the grayscale of β-actin in cells were also assayed. For panels B to G, analyses were performed by Student's t test; for panel H, two-way ANOVA multiple comparisons tests were used to compare the data from different treatment groups. Values are means ± SD. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; n = 3. The error bars indicate the standard deviation.

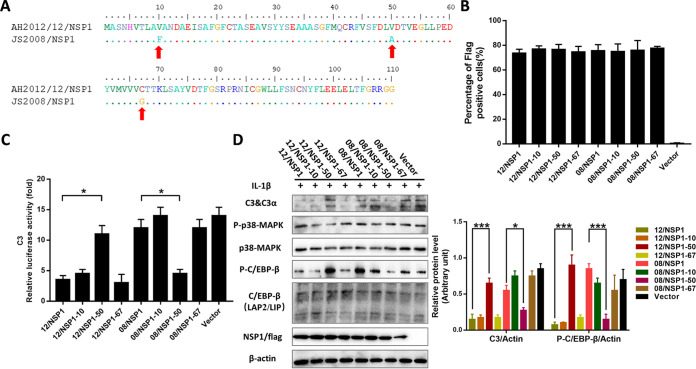

Amino acid 50 of NSP1 plays a role in regulating C3 expression.

To define the critical amino acid sites responsible for regulating C3 expression, we aligned the amino acid sequences of AH2012/12 and JS2008 NSP1 and identified three differential amino acids: V10F, V50A, and C67G (Fig. 6A). The NSP1 expression vectors with single amino acid mutants were constructed and transfected into Huh7 cells. The flow cytometry analysis showed that more than 70% of cells were positive for NSP1 (Fig. 6B). Of note, a single mutation at V50A rendered 12/NSP1 similar to 08/NSP1 with the no inhibition effect on C3 promoter activity (Fig. 6C). In addition, A50V acted as a gain-of-function mutation in a 08/NSP1 background and allowed comparable inhibition of C3 promoter activity to that of wild-type JS2008 NSP1 (Fig. 6C). Moreover, Western blot assays showed that phosphorylation of C/EBP-β and C3 expression levels were significantly increased and decreased in the 12/NSP1-50- and 08/NSP1-50-transfected groups, respectively, compared with those of their respective parental strain NSP1 (Fig. 6D). The above results suggested that the amino acid 50 of NSP1 plays an important role in regulating C3 expression.

FIG 6.

Amino acid 50 of NSP1 plays a role in regulating C3 expression. (A) Amino acid sequence alignment of AH2012/12 and JS2008 NSP1 revealed three amino acids mutations V10F, V50A, and C67G. Huh7 cells were transfected with the mutant vectors of AH2012/12 and JS2008 NSP1 proteins. After 24 h, the percentages of NSP1-expressed cells were determined by flow cytometry (B); the same treated cells were inoculated with 10 ng/mL IL-1β for another 24 h and then lysed to assay the C3 luciferase activities (C) and the expression levels of different proteins (D). The relative expression levels of target proteins according to the grayscale of β-actin in cells were also assayed. For panel C, analyses were performed by Student's t test; for panel D, two-way ANOVA multiple comparisons tests were used to compare the data from different treatment groups. Values are means ± SD. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; n = 3. The error bars indicate the standard deviation.

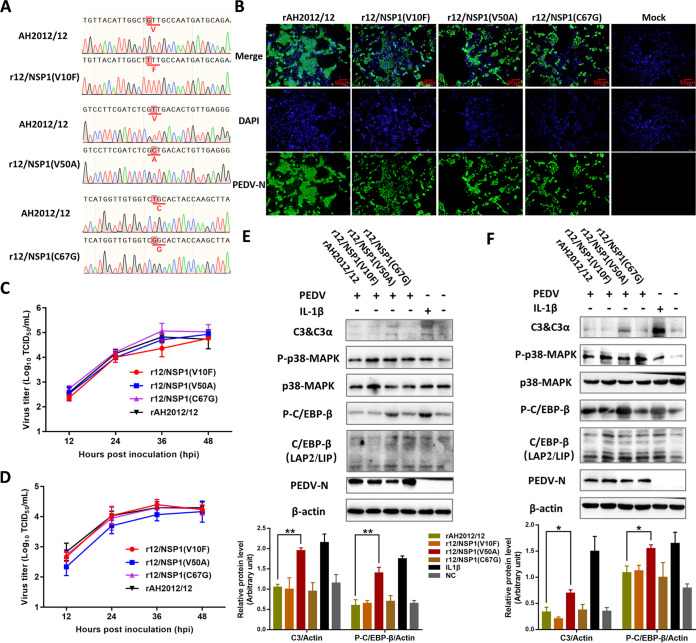

The regulation of C3 by amino acid 50 of NSP1 at the viral level.

To verify the regulation of C3 by amino acid 50 of NSP1 in the context of infectious viruses, we constructed three mutant strains, r12/NSP1 (V10F), r12/NSP1 (V50A), and r12/NSP1 (C67G), using variant strain AH2012/12 as the backbone (Fig. 7A). Biological characterization assays showed that the mutant strains were equally effective at infecting Vero cells as the parental strain (Fig. 7B), with generally consistent replication kinetic curves and viral titers of approximately 105 TCID50/mL at 36 hpi (Fig. 7C). Moreover, the replication kinetic curves of the mutant viruses in Huh7 cells were also determined by TCID50 assay. As shown in Fig. 7D, the viral titers of r12/NSP1 (V50A) were lower than those of rAH2012/12 at 12 (P = 0.10), 24 (P = 0.13), and 36 hpi (P = 0.37). Western blot assays of the mutant viruses-infected Huh7 cells showed that C/EBP-β phosphorylation and C3 expression levels in the r12/NSP1 (V50A)-infected group were significantly increased compared with those of the rAH2012/12-infected group (Fig. 7E). Meanwhile, C/EBP-β phosphorylation and C3 expression levels of the mutant viruses-infected IPEC-J2 cells were also detected, and the results showed that they were both significantly increased in the r12/NSP1 (V50A)-infected group compared with those of the rAH2012/12-infected group (Fig. 7F). The above results indicated that, at the viral level, amino acid 50 of NSP1 also plays a regulatory role in C3 expression.

FIG 7.

C3 regulation of NSP1 amino acid 50 at the viral level. (A) Three mutant strains, r12/NSP1 (V10F), r12/NSP1 (V50A), and r12/NSP1 (C67G), were constructed using the variant strain AH2012/12 as a backbone. The mutants were used to inoculate Vero cells at 1 MOI. (B) The specific fluorescence of N protein was detected using IFs at 24 hpi. The growth curves of viruses in Vero (C) and Huh7 (D) cells were determined using the virus titers at different time points after viral infection. Huh7 (E) and IPEC-J2 (F) cells were infected with the recombinant viruses or inoculated with IL-1β alone as the positive control for 24 h. Then, all cells were lysed to assay the expression levels of different proteins. The relative expression levels of target proteins according to the grayscale of β-actin in cells were also assayed. For panels E and F, two-way ANOVA multiple comparisons tests were used to compare the data from different treatment groups. Values are means ± SD. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; n = 3. The error bars indicate the standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

The involvement of the complement system in coronavirus infection has been the subject of many studies, especially since the outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 in 2019, with many researchers focusing on the role of the complement cascade in the pathogenesis of this virus (18). Numerous studies have confirmed a clear correlation between severe COVID-19 pneumonia and complement cascade overactivation (19). Plasma samples from patients suffering from COVID-19 showed a high level of complement proteins, including C5, C6, and C8 (33). For the swine coronavirus PEDV, only a few studies have reported the effect of viral infection on complement components. Chen et al. isolated serum exosomes and found significant decreases in C3, C6, and CFB complement components in PEDV-infected newborn piglets compared with those of mock piglets (31). In addition, the levels of proinflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α in the serum samples of PEDV-infected piglets were reported to be significantly increased (30). In this study, downregulation of multiple complement components, including C3, was similarly found with previous studies based on single-cell transcriptome data from the intestine of piglets infected with variant PEDV strain AH2012/12. In in vitro studies, we confirmed that PEDV infection upregulates the inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-6 but that variant PEDV exerts suppression of C3 expression through amino acid 50 of NSP1, thereby restricting the inhibitory effect of C3 on viral replication.

C3, which is a central molecule in the complement system, plays an important role in inhibiting virus replication (34, 35). The previous study showed that sensing of C3 in the cytoplasm activated mitochondrial antiviral signaling (MAVS)-dependent signaling cascades and induced proinflammatory cytokine secretion (34). In our study, we found that intracellular transient overexpression of C3 protein had a significant inhibitory effect on PEDV replication. This inhibition is perhaps related to the intracellular sensing of C3 that activates cell autonomous immunity. Moreover, we found that when Vero cells were infected by PEDV preincubated with purified C3 protein, the virus replication indexes could be reduced by 50% compared with those of the cell groups inoculated with virus alone (data not shown). A similar phenomenon was found in transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV), another member of the alpha coronaviruses, with some complement components from rabbit or guinea pig serum being able to neutralize TGEV virulent in the absence of known antibodies against TGEV (36). Several studies have reported that C3 activation results in virion lysis through membrane attack complex formation, opsonization, virion aggregation, and activation product deposition on virus particles (37). In this study, one explanation for our findings may be that C3 deposition on PEDV hinders its attachment to host cells, thereby leading to virus neutralization. Another reason may be that C3 aggregates and becomes deposited on the virion, leading to viral lysis. In addition, we found that the replication dynamic of r12/NSP1 (V50A) was lower than that of rAH2012/12, which most likely resulted from the elimination of inhibition of C3 expression. Such results suggest an inhibitory effect of C3 on PEDV replication and a critical role for the amino acid site in regulating C3 expression.

The complement system serves as an important immune defense against viruses in constant surveillance. The pressure exerted by complement on viruses led them to evolve multiple countermeasures. These include avoiding detection by targeting the recognition molecules, targeting the key enzymes and complexes of the complement pathway, encoding proteases that cleave complement proteins, and inhibiting the synthesis of complement proteins (38). For the production of C3, multiple studies have confirmed the important roles of upstream kinase p38-MAPK and C/EBP-β in initiating C3 transcription (14, 39). In IL-1β-mediated induction of the C3 gene, the roles of p38-MAPK, different isoforms, and the phosphorylation of C/EBP-β had been investigated by Maranto et al. (14, 39). Furthermore, Mazumdar et al. found that the hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS5A primarily suppresses the expression of C3 by inhibiting expression of IL-1β-induced C/EBP-β transcription factor (40). In this study, we demonstrated that a PEDV variant strain can downregulate the transcript level of C3 by inhibiting the phosphorylation of C/EBP-β, which is different from the mode of action of HCV. In addition, it is worth mentioning the roles of the different isoforms of C/EBP-β in the induction of C3 transcript levels. LAP2 reportedly had a profound effect on the induction of C3 promoter activity compared to that of LAP1 and LIP (14). The data in this study also reflected the important role of LAP2 with the consistency of changes of LAP2 phosphorylation and C3 expression.

Coronavirus NSP1 has the conserved biological function of inhibiting host gene expression (41–43). In addition, NSP1 also was characterized by the function of viral immune system evasion. PEDV NSP1 mediates cAMP-response element-binding protein (CREB)-binding protein and nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) degradation to inhibit type I interferon (IFN) responses (44, 45). In this study, we found a role for NSP1 in the regulation of complement responses, especially with PEDV variants, in the suppression of complement C3 expression, indicating a novel mechanism for NSP1 in innate immune regulation.

The PEDV NSP1 is structurally characterized by an irregular six-stranded β-barrel fold in the middle of two α-helices. The α1-helix that is located at the rim of the barrel forms a separate area (43). The α2-helix contains six amino acids, which is longer than other reported coronavirus NSP1 helices (41, 46). We identified a role for amino acid 50 in the regulation of C/EBP-β phosphorylation, and an alanine to valine mutation rendered NSP1 incapable of phosphorylating C/EBP-β. Structural analysis revealed that this amino acid is in the α2-helix. The size of the side chain determines the stability of the α-helix. If the R-group is too large, no intrachain hydrogen bonds can be formed because of electrostatic repulsion, which prevents the formation of a stable α-helix. Valine has a larger side chain (isopropyl) than alanine (methyl), all of which are hydrophobic amino acids, generally distributed in the interior of the protein molecule. If distributed in the active center, they can alter the active site structure and cause loss of functional activity.

Overall, we resolved key viral factors involved in the repression of C3 expression by a variant strain of PEDV, as well as the molecular signaling pathways involved in their repression. This study furthers our understanding of PEDV NSP1 protein function and reveals a novel finding that variant PEDV can escape the innate immune response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Cell lines Vero (ATCC CCL-81), IPEC-J2, and Huh7, were stored in our laboratory. The classical PEDV strain JS2008 and the highly pathogenic variant strain AH2012/12 were isolated from pig farms in China (47, 48). The TCID50 values of these viruses were determined by titration in Vero cells and stored at −80°C.

The effects of PEDV infections on C3 expression.

IPEC-J2 cells grown to a complete monolayer were incubated with PEDV variant strain AH2012/12 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 with 3 μg/mL trypsin, and Huh7 cells were incubated with AH2012/12 or JS2008 at an MOI of 1 with 5 μg/mL trypsin. Then, all cells were cultured at 37°C for 1 h to allow the viruses to invade. At different time points after viral infection, the cell samples were analyzed by Western blotting, indirect immunofluorescence, and real-time quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR). PEDV yields in the supernatant were titrated by the TCID50 assay by using Vero cells, and the supernatants were also obtained to assay the content of C3 by using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Elabscience, Wuhan, China).

Construction of recombinant plasmids.

Total RNA was extracted from IPEC-J2 cells using a QIAprep RNA minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and cDNA synthesis was performed with SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, CA, USA). The modified vector pLVX-N1 without the mCherry tag (pLV-Exp) was obtained as previously described (49). Then, amplicons of pig C3 amplified from IPEC-J2 cDNA were cloned into pLV-Exp with a HA tag at the carboxyl terminus (pLV-pC3/HA) using the recombinant cloning kit ClonExpress II (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Multiple nonstructural and structural proteins of AH2012/12 and the single point mutants of the NSP1 proteins of AH2012/12 and JS2008 were cloned into pcDNA3.1 with a Flag tag at the carboxyl terminus. All primers have been listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Assaying the inhibition of C3 on PEDV replication.

In order to assay the inhibition of C3 on PEDV replication, Huh7 cells at 80% confluence were transfected with pLV-pC3/HA or pLV-Exp at 1.5 μg/well, C3-siRNAs, or siRNA-C (RiboBio, Guangzhou, China) at 50 nM in a 24-well plate using Lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Thermo Fisher Scientific, CA, USA). After 24 h, all cells were inoculated with AH2012/12 or JS2008 at an MOI of 1 for another 24 h. Then, the infected cells were analyzed at the protein expression level for C3, C3-HA, PEDV-N, and β-actin proteins by Western blotting and at the transcript level for PEDV mRNA by relative qRT-PCR; the virus titers in the supernatant were determined by TCID50 assay.

Assaying the effects of Com on PEDV replication.

Huh7 cells were inoculated with Com at different concentrations (5, 10, and 15 μM), and the same volumes of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were added to the controls. After 6 h, all cells were inoculated with AH2012/12 or JS2008 at an MOI of 0.1 for another 24 h. The infected cells were detected using IFs and flow cytometry analysis, and the gene copy numbers of PEDV were determined by qRT-PCR.

Effects of virus infections on C3 expression induced by IL-1β.

Huh7 cells with complete monolayer were inoculated together with 1 MOI of AH2012/12, JS2008, or recombinant viruses, with IL-1β (10 ng/mL). At 24 hpi, all cells were lysed to assay the expression levels of C3, PEDV-N, and the critical members of C3 expression signaling pathway by Western blotting.

Construction of recombinant viruses.

To construct the recombinant viruses containing mutant NSP1, CRISPR-Cas9 technology was used to generate recombinant viruses as previously reported (50). Briefly, two single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) encompassing the NSP1 sequence were selected. The sgRNAs were generated by in vitro T7 transcription from the templates amplified by overlapping PCR with forward primers sgnsp1F1/F2 and a constant reverse primer scaffold oligonucleotide. Then, the PEDV AH2012/12 genomic cDNA in the bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) plasmid was cleaved by incubation in a mixture containing 5 μg of BAC plasmid, 5 μL of Cas9 nuclease (NEB, Beijing, China), 10 μg of sgRNA, and 5 μL of 10× NEBuffer 3.1 at 37°C for 2.5 h. The cleaved BAC plasmid was purified with a DNA cycle pure kit (Omega Bio-tek). Then, homologous recombination using an In-Fusion clone kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) was performed by incubation of the purified BAC plasmid with DNA fragments containing expected NSP1 mutations at 50°C for 30 min. Finally, 10 μL of reaction mixture was transformed into DH10B cells (Biomed, Beijing, China), and the recombinant BAC plasmids were verified by sequencing. The primers used to construct recombinant PEDVs are shown in Table S1.

Confluent Vero cells in six-well culture plates were transfected with recombinant BAC plasmids (6 μg/well) using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, CA, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. At 6 h posttransfection, the cells were washed twice with Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) and supplemented with DMEM containing 7.5 μg/mL of trypsin (2 mL/well). The cells were then placed in an incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2 to facilitate the recovery of infectious viruses. Cells were observed daily under a microscope to check the appearance of the CPE, and the biological assays of recombinant viruses were performed as described previously (48).

Luciferase assay.

In experiments assessing the effects of IL-1β and/or IL-6 in C3 activity, cells were treated with the cytokines (10 ng/mL for IL-1β and 50 ng/mL for IL-6) for 24 h and lysed by reporter lysis buffer (Promega, WI, USA). In the screen for viral proteins and their critical sites that regulate C3 expression, Huh7 cells were transfected with a C3 promoter luciferase reporter construct (500 ng/well) (Addgene Inc., MA, USA) alone or together with constructed PEDV nonstructural or structural protein recombinant vectors (1.5 μg/well), 12/NSP1 and 12/NSP9, at different concentrations (0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 μg/well) or the single point mutant vectors (1.5 μg/well) in a 24-well plate. At 24 h posttransfection, cells were inoculated with 10 ng/mL IL-1β for another 24 h. Then, all cells were lysed by reporter lysis buffer. When the effect of viral infection on IL-1β-induced C3 was determined, 1 MOI of the virus and the relevant cytokines were coinoculated into cells for 24 h. Then, all of the cells were lysed to assay the C3 luciferase activities, and the luciferase activities were measured using a multimode plate reader (EnSpire Alpha; PerkinElmer).

qRT-PCR.

Total RNA from the cells was extracted using a total RNA kit (Omega, Guangzhou, China), and the RNA was converted to cDNA using the HiScript II Q RT supermix (+genomic DNA [gDNA] wiper) (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative determinations of C3, IL-1β, and IL-6 mRNAs in IPEC-J2 or Huh7 cells and PEDV N protein genes were performed by real-time PCR analyses using the specific primers described in Table S1. The transcript levels of target genes were relatively quantified using the 2−ΔΔCT method. The GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) gene served as an internal reference. Moreover, the quantitative determinations of viral copy number were performed by qRT-PCR with the primers and probes targeting conserved regions of the PEDV N protein gene as previously described (49).

Indirect immunofluorescence.

The indirect immunofluorescence (IF) assays were carried out as described previously with little modification (49). Briefly, Huh7 and Vero cells with different treatments were fixed with 4% formaldehyde and blocked with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 5% bovine serum albumin. After being blocked, the cells were incubated with a PEDV-specific monoclonal antibody (produced in our laboratory; the immune-purified prokaryotic expression protein was the N protein of PEDV JS2008 strain; GenBank accession number KC109141) and then diluted 1:1,000 for 1 h. The cells were then washed and incubated with secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC], diluted 1:500) for 45 min. For the plasmid-transfected Huh7 cells, the blocked cells were incubated with Flag-specific monoclonal antibody (Abmart; diluted 1:1,000) and Cy3 labeled goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (diluted 1:500). Finally, all of the cells were washed and then visualized by fluorescence microscopy.

Western blot analysis.

The Western blot analysis was performed as described before with little modification (51). Briefly, total cellular proteins were extracted from the cells with different treatments. The obtained protein samples were separated on SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto 0.22-μm polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) using a semidry electrophoretic transfer cell (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% (wt/vol) nonfat dry milk overnight at 4°C and then probed with anti-C3 (Invitrogen; catalog number PA5-21349; 1:1,000), C/EBP-β (ABclonal Technology; catalog number A19538; 1:1,000), P-C/EBP-β (ABclonal Technology; catalog number AP1055; 1:1,000), anti-p38-MAPK (Beyotime Biotechnology; catalog number AF7668; 1:1,000), P-p38-MAPK (Beyotime Biotechnology; catalog number AF5887; 1:1,000), anti-PEDV-N (made in lab; 1:1,000), or anti-HA tag, Flag tag, and β-actin (Proteintech Group; catalog numbers 66006-2-Ig, 66008-4-Ig, 66009-1-Ig; 1:20,000) primary antibodies at 37°C for 1 h. After thorough washing with PBS + 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (PBST), the membranes were incubated with the corresponding horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (Proteintech Group; 1:10,000) overnight at 4°C. The target protein blots on the membranes were developed with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and images were taken using a Tanon 5200 CE chemi-image system (Tanon, Shanghai, China). The relative expression levels of target proteins according to the grayscale of β-actin or the indicator proteins in cells were assayed using ImageJ software (version 1.8.0 for Windows) as described previously (49).

Flow cytometry.

The virus-infected cells and the recombinant vector-transfected cells were harvested and pretreated with fixation/permeabilization and permeabilization buffers (eBioscience); next, all cells were stained with anti-PEDV-N or Flag-tag primary antibody, followed by FITC or Cy3-labeled goat anti-mouse secondary antibody. After antibody staining, the cells were resuspended and passed through a 35-μm nylon filter to remove aggregates, and the frequencies of target cells were evaluated by using BD C6 Verse; data were analyzed using FlowJo version 7.6.1 software.

Statistical analysis.

All data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Student’s t tests and two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were used to compare the data from different treatment groups. Differences with a P value of <0.05 were considered significant. All statistical analyses and calculations were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 7.0 for Windows; GraphPad Software Inc.).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program (2021YFD1801104), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31802167 and 31872481), Jiangsu province Natural Sciences Foundation (BK20191235, BK20190003, and BK20210158), Jiangsu Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Fund (CX(21)3139), Innovation Foundation of Jiangsu Academy of Agricultural Sciences (ZX(21)1217), and the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2019A1515010658).

We declare no competing interests.

B. Fan, Q. Peng, S. Song, D. Shi, X. Zhang, W. Guo, Y. Li, J. Zhou, X. Zhu, Y. Zhao, H. Fan, and R. Guo conducted the experiments; B. Fan, Q. Peng, and B. Li conducted the investigations; B. Fan, Q. Peng, and B. Li performed the data analysis and wrote the manuscript; B. Fan, K. He, S. Ding, and B. Li designed the research; and the final version of the manuscript was reviewed and approved by all the authors.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Bin Li, Email: libinana@126.com.

Bryan R. G. Williams, Hudson Institute of Medical Research

REFERENCES

- 1.Ghebrehiwet B. 2016. The complement system: an evolution in progress. F1000Res 5:2840. 10.12688/f1000research.10065.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolev M, Le Friec G, Kemper C. 2014. Complement–tapping into new sites and effector systems. Nat Rev Immunol 14:811–820. 10.1038/nri3761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carroll MC. 2004. The complement system in regulation of adaptive immunity. Nat Immunol 5:981–986. 10.1038/ni1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walport MJ. 2001. Complement. N Engl J Med 344:1058–1066. 10.1056/NEJM200104053441406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roozendaal R, Carroll MC. 2006. Emerging patterns in complement-mediated pathogen recognition. Cell 125:29–32. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pio R, Corrales L, Lambris JD. 2014. The role of complement in tumor growth. Adv Exp Med Biol 772:229–262. 10.1007/978-1-4614-5915-6_11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu XY, Wang XY, Li RY, Jia SC, Sun P, Zhao M, Fang C. 2017. Recent progress in the understanding of complement activation and its role in tumor growth and anti-tumor therapy. Biomed Pharmacother 91:446–456. 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.04.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar NA, Kunnakkadan U, Thomas S, Johnson JB. 2020. In the crosshairs: RNA viruses OR complement? Front Immunol 11:573583. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.573583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agrawal P, Sharma S, Pal P, Ojha H, Mullick J, Sahu A. 2020. The imitation game: a viral strategy to subvert the complement system. FEBS Lett 594:2518–2542. 10.1002/1873-3468.13856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juan TS, Wilson DR, Wilde MD, Darlington GJ. 1993. Participation of the transcription factor C/EBP delta in the acute-phase regulation of the human gene for complement component C3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:2584–2588. 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coulpier M, Andreev S, Lemercier C, Dauchel H, Lees O, Fontaine M, Ripoche J. 1995. Activation of the endothelium by IL-1α and glucocorticoids results in major increase of complement C3 and factor B production and generation of C3a. Clin Exp Immunol 101:142–149. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb02290.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawakami Y, Watanabe Y, Yamaguchi M, Sakaguchi H, Kono I, Ueki A. 1997. TNF-alpha stimulates the biosynthesis of complement C3 and factor B by human umbilical cord vein endothelial cells. Cancer Lett 116:21–26. 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)04737-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stapp JM, Sjoelund V, Lassiter HA, Feldhoff RC, Feldhoff PW. 2005. Recombinant rat IL-1beta and IL-6 synergistically enhance C3 mRNA levels and complement component C3 secretion by H-35 rat hepatoma cells. Cytokine 30:78–85. 10.1016/j.cyto.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maranto J, Rappaport J, Datta PK. 2011. Role of C/EBP-beta, p38 MAPK, and MKK6 in IL-1beta-mediated C3 gene regulation in astrocytes. J Cell Biochem 112:1168–1175. 10.1002/jcb.23032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nerlov C. 2007. The C/EBP family of transcription factors: a paradigm for interaction between gene expression and proliferation control. Trends Cell Biol 17:318–324. 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eaton EM, Hanlon M, Bundy L, Sealy L. 2001. Characterization of C/EBPβ isoforms in normal versus neoplastic mammary epithelial cells. J Cell Physiol 189:91–105. 10.1002/jcp.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li G, Fan Y, Lai Y, Han T, Li Z, Zhou P, Pan P, Wang W, Hu D, Liu X, Zhang Q, Wu J. 2020. Coronavirus infections and immune responses. J Med Virol 92:424–432. 10.1002/jmv.25685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perico L, Benigni A, Casiraghi F, Ng LFP, Renia L, Remuzzi G. 2021. Immunity, endothelial injury and complement-induced coagulopathy in COVID-19. Nat Rev Nephrol 17:46–64. 10.1038/s41581-020-00357-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polycarpou A, Howard M, Farrar CA, Greenlaw R, Fanelli G, Wallis R, Klavinskis LS, Sacks S. 2020. Rationale for targeting complement in COVID-19. EMBO Mol Med 12:e12642. 10.15252/emmm.202012642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hembram P. 2021. An outline of SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis and the complement cascade of immune system. Bull Natl Res Cent 45:123. 10.1186/s42269-021-00582-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pensaert MB, de Bouck P. 1978. A new coronavirus-like particle associated with diarrhea in swine. Arch Virol 58:243–247. 10.1007/BF01317606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kusanagi K, Kuwahara H, Katoh T, Nunoya T, Ishikawa Y, Samejima T, Tajima M. 1992. Isolation and serial propagation of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in cell cultures and partial characterization of the isolate. J Vet Med Sci 54:313–318. 10.1292/jvms.54.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun RQ, Cai RJ, Chen YQ, Liang PS, Chen DK, Song CX. 2012. Outbreak of porcine epidemic diarrhea in suckling piglets, China. Emerg Infect Dis 18:161–163. 10.3201/eid1801.111259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li W, Li H, Liu Y, Pan Y, Deng F, Song Y, Tang X, He Q. 2012. New variants of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, China, 2011. Emerg Infect Dis 18:1350–1353. 10.3201/eid1808.120002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang YW, Dickerman AW, Piñeyro P, Li L, Fang L, Kiehne R, Opriessnig T, Meng XJ. 2013. Origin, evolution, and genotyping of emergent porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strains in the United States. mBio 4:e00737-13. 10.1128/mBio.00737-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen F, Pan Y, Zhang X, Tian X, Wang D, Zhou Q, Song Y, Bi Y. 2012. Complete genome sequence of a variant porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strain isolated in China. J Virol 86:12448. 10.1128/JVI.02228-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bi J, Zeng S, Xiao S, Chen H, Fang L. 2012. Complete genome sequence of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strain AJ1102 isolated from a suckling piglet with acute diarrhea in China. J Virol 86:10910–10911. 10.1128/JVI.01919-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jung K, Saif LJ. 2015. Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus infection: etiology, epidemiology, pathogenesis and immunoprophylaxis. Vet J 204:134–143. 10.1016/j.tvjl.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li S, Yang J, Zhu Z, Zheng H. 2020. Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus and the host innate immune response. Pathogens 9:367. 10.3390/pathogens9050367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang H, Han F, Shu X, Li Q, Ding Q, Hao C, Yan X, Xu M, Hu H. 2022. Co-infection of porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus and porcine deltacoronavirus enhances the disease severity in piglets. Transbound Emerg Dis 69:1715–1726. 10.1111/tbed.14144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen J, Jin L, Yan M, Yang Z, Wang H, Geng S, Gong Z, Liu G. 2019. Serum exosomes from newborn piglets restrict porcine epidemic diarrhea virus infection. J Proteome Res 18:1939–1947. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.9b00195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mastellos DC, Yancopoulou D, Kokkinos P, Huber-Lang M, Hajishengallis G, Biglarnia AR, Lupu F, Nilsson B, Risitano AM, Ricklin D, Lambris JD. 2015. Compstatin: a C3-targeted complement inhibitor reaching its prime for bedside intervention. Eur J Clin Invest 45:423–440. 10.1111/eci.12419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shen B, Yi X, Sun Y, Bi X, Du J, Zhang C, Quan S, Zhang F, Sun R, Qian L, Ge W, Liu W, Liang S, Chen H, Zhang Y, Li J, Xu J, He Z, Chen B, Wang J, Yan H, Zheng Y, Wang D, Zhu J, Kong Z, Kang Z, Liang X, Ding X, Ruan G, Xiang N, Cai X, Gao H, Li L, Li S, Xiao Q, Lu T, Zhu Y, Liu H, Chen H, Guo T. 2020. Proteomic and metabolomic characterization of COVID-19 patient sera. Cell 182:59–72. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tam JC, Bidgood SR, McEwan WA, James LC. 2014. Intracellular sensing of complement C3 activates cell autonomous immunity. Science 345:1256070. 10.1126/science.1256070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arbore G, Kemper C, Kolev M. 2017. Intracellular complement - the complosome - in immune cell regulation. Mol Immunol 89:2–9. 10.1016/j.molimm.2017.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woods RD, Wesley RD, Kapke PA. 1988. Neutralization of porcine transmissible gastroenteritis virus by complement-dependent monoclonal antibodies. Am J Vet Res 49:300–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santiesteban-Lores LE, Amamura TA, da Silva TF, Midon LM, Carneiro MC, Isaac L, Bavia L. 2021. A double edged-sword - the complement system during SARS-CoV-2 infection. Life Sci 272:119245. 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Agrawal P, Nawadkar R, Ojha H, Kumar J, Sahu A. 2017. Complement evasion strategies of viruses: an overview. Front Microbiol 8:1117. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tahirov TH, Sato K, Ichikawa-Iwata E, Sasaki M, Inoue-Bungo T, Shiina M, Kimura K, Takata S, Fujikawa A, Morii H, Kumasaka T, Yamamoto M, Ishii S, Ogata K. 2002. Mechanism of c-Myb-C/EBPβ cooperation from separated sites on a promoter. Cell 108:57–70. 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00636-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mazumdar B, Kim H, Meyer K, Bose SK, Di Bisceglie AM, Ray RB, Ray R. 2012. Hepatitis C virus proteins inhibit C3 complement production. J Virol 86:2221–2228. 10.1128/JVI.06577-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jansson AM. 2013. Structure of alphacoronavirus transmissible gastroenteritis virus nsp1 has implications for coronavirus nsp1 function and evolution. J Virol 87:2949–2955. 10.1128/JVI.03163-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shen Z, Wang G, Yang Y, Shi J, Fang L, Li F, Xiao S, Fu ZF, Peng G. 2019. A conserved region of nonstructural protein 1 from alphacoronaviruses inhibits host gene expression and is critical for viral virulence. J Biol Chem 294:13606–13618. 10.1074/jbc.RA119.009713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shen Z, Ye G, Deng F, Wang G, Cui M, Fang L, Xiao S, Fu ZF, Peng G. 2018. Structural basis for the inhibition of host gene expression by porcine epidemic diarrhea virus nsp1. J Virol 92:e01896-17. 10.1128/JVI.01896-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Q, Shi K, Yoo D. 2016. Suppression of type I interferon production by porcine epidemic diarrhea virus and degradation of CREB-binding protein by nsp1. Virology 489:252–268. 10.1016/j.virol.2015.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Q, Ma J, Yoo D. 2017. Inhibition of NF-kappaB activity by the porcine epidemic diarrhea virus nonstructural protein 1 for innate immune evasion. Virology 510:111–126. 10.1016/j.virol.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Almeida MS, Johnson MA, Wuthrich K. 2006. NMR assignment of the SARS-CoV protein nsp1. J Biomol NMR 36(Suppl 1):46. 10.1007/s10858-006-9018-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li B, Liu H, He K, Guo R, Ni Y, Du L, Wen L, Zhang X, Yu Z, Zhou J, Mao A, Lv L, Hu Y, Yu Y, Zhu H, Wang X. 2013. Complete genome sequence of a recombinant porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strain from Eastern China. Genome Announc 1:e0010513. 10.1128/genomeA.00105-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fan B, Yu Z, Pang F, Xu X, Zhang B, Guo R, He K, Li B. 2017. Characterization of a pathogenic full-length cDNA clone of a virulent porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strain AH2012/12 in China. Virology 500:50–61. 10.1016/j.virol.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fan B, Zhu L, Chang X, Zhou J, Guo R, Zhao Y, Shi D, Niu B, Gu J, Yu Z, Song T, Luo C, Ma Z, Bai J, Zhou B, Ding S, He K, Li B. 2019. Mortalin restricts porcine epidemic diarrhea virus entry by downregulating clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Vet Microbiol 239:108455. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2019.108455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peng Q, Fang L, Ding Z, Wang D, Peng G, Xiao S. 2020. Rapid manipulation of the porcine epidemic diarrhea virus genome by CRISPR/Cas9 technology. J Virol Methods 276:113772. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2019.113772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou J, Huang S, Fan B, Niu B, Guo R, Gu J, Gao S, Li B. 2021. iTRAQ-based proteome analysis of porcine group A rotavirus-infected porcine IPEC-J2 intestinal epithelial cells. J Proteomics 248:104354. 10.1016/j.jprot.2021.104354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Download jvi.01024-22-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 0.09 MB (92.5KB, pdf)