ABSTRACT

HIV-1 DNA is preferentially integrated into chromosomal hot spots by the preintegration complex (PIC). To understand the mechanism, we measured the DNA integration activity of PICs—extracted from infected cells—and intasomes, biochemically assembled PIC substructures using a number of relevant target substrates. We observed that PIC-mediated integration into human chromatin is preferred compared to genomic DNA. Surprisingly, nucleosomes lacking histone modifications were not preferred integration compared to the analogous naked DNA. Nucleosomes containing the trimethylated histone 3 lysine 36 (H3K36me3), an epigenetic mark linked to active transcription, significantly stimulated integration, but the levels remained lower than the naked DNA. Notably, H3K36me3-modified nucleosomes with linker DNA optimally supported integration mediated by the PIC but not by the intasome. Interestingly, optimal intasome-mediated integration required the cellular cofactor LEDGF. Unexpectedly, LEDGF minimally affected PIC-mediated integration into naked DNA but blocked integration into nucleosomes. The block for the PIC-mediated integration was significantly relieved by H3K36me3 modification. Mapping the integration sites in the preferred substrates revealed that specific features of the nucleosome-bound DNA are preferred for integration, whereas integration into naked DNA was random. Finally, biochemical and genetic studies demonstrate that DNA condensation by the H1 protein dramatically reduces integration, providing further evidence that features inherent to the open chromatin are preferred for HIV-1 integration. Collectively, these results identify the optimal target substrate for HIV-1 integration, report a mechanistic link between H3K36me3 and integration preference, and importantly, reveal distinct mechanisms utilized by the PIC for integration compared to the intasomes.

IMPORTANCE HIV-1 infection is dependent on integration of the viral DNA into the host chromosomes. The preintegration complex (PIC) containing the viral DNA, the virally encoded integrase (IN) enzyme, and other viral/host factors carries out HIV-1 integration. HIV-1 integration is not dependent on the target DNA sequence, and yet the viral DNA is selectively inserted into specific “hot spots” of human chromosomes. A growing body of literature indicates that structural features of the human chromatin are important for integration targeting. However, the mechanisms that guide the PIC and enable insertion of the PIC-associated viral DNA into specific hot spots of the human chromosomes are not fully understood. In this study, we describe a biochemical mechanism for the preference of the HIV-1 DNA integration into open chromatin. Furthermore, our study defines a direct role for the histone epigenetic mark H3K36me3 in HIV-1 integration preference and identify an optimal substrate for HIV-1 PIC-mediated viral DNA integration.

KEYWORDS: human immunodeficiency virus, HIV, preintegration complex, PIC, nucleosome, integration, chromatin, histone, posttranslational modification, PTM, H3K36me3, intasome

INTRODUCTION

The human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) has infected approximately 80 million people worldwide, with ~38 million people currently living with the virus (UNAIDS, 2021). Highly potent antiretroviral therapy (ART) has rendered HIV-1 infection a chronic condition and has significantly reduced the burden of AIDS (UNAIDS, 2021). However, ART is not curative, faces drug resistance, and lifelong ART can cause severe toxicity and comorbid conditions (1). Therefore, a clear understanding of the mechanism of HIV-1 replication is critical for the continued development of novel and improved therapeutic strategies.

HIV-1 replicates in immune cells expressing the CD4 receptor and the CCR5 or CXCR4 chemokine coreceptors (2). Binding of the HIV-1 glycoprotein(s) to these receptors and coreceptors initiates the fusion of the viral membrane to the cellular plasma membrane (3). Thereafter, the viral capsid containing two copies of the linear single-stranded viral RNA genome and a number of viral/cellular factors is released into the cytoplasm of the host cell (4–9). The cytoplasmic release of the capsid allows the reverse transcription complex (RTC) to convert the viral RNA genome into a double-stranded viral DNA copy (10). Subsequently, by a poorly understood mechanism, the RTC transitions into a preintegration complex (PIC). The PIC containing the viral DNA, viral integrase (IN) enzyme, and associated cellular/viral proteins (11) carries out integration of the viral DNA into the host chromatin to establish the proviral genome (12–17). The proviral genome is required for the production of progeny virions and the establishment of viral reservoirs (18–20). Because integration is critical for HIV-1 infection (11, 21, 22), this step has been the target of highly potent antiviral drugs (23, 24).

HIV-1 DNA integration is dependent on the activity of the PIC-associated IN enzyme (25). First, IN carries out the 3′-processing of the viral DNA ends and then, via a strand-transfer step, the viral DNA is inserted into the host genomic DNA (26–29). Even though HIV-1 integration is not dependent on the target DNA sequence (30), the viral DNA is selectively inserted into specific “hot spots” of human chromosomes (31). Notably, the protein-coding genes account for <2% of the entire human genome. However, this tiny fraction of the human genome contains over half of the reported HIV-1 integration sites (31–37). Despite HIV-1 IN being the primary viral factor required for inserting the viral DNA into chromosomal hot spots, a growing body of literature indicates that structural features of the human chromatin are important for integration targeting (33, 37–42). For instance, HIV-1 integration site analysis reveals selective integration patterns into the intragenic regions of the open chromatin (35, 36, 40, 43). These preferred regions for integration are often characterized by active transcription, gene density, and epigenetic factors characteristic of open chromatin (33, 37, 40, 42–46). In particular, deep-sequencing analysis coupled with the advances in human genome annotation have provided evidence that HIV-1 integration is favored near chromatin features associated with active transcription (33, 47–49). Consistent with the model that open chromatin is favored for HIV-1 integration, heterochromatic regions at human centromeres and telomeres are disfavored for integration (31, 40, 42, 44). However, the mechanisms that guide the PIC and enable insertion of the PIC-associated viral DNA into specific hot spots of the human chromosomes are not fully understood.

To insert the viral DNA into the genomic hot spots, the PIC must engage/overcome the structural barriers of the chromosomal landscape. For instance, a single copy of the human genome can extend over 2 m, yet it is packaged into a nucleus with an average diameter of 10 μm (50). This complex and poorly understood genome compaction process is achieved by organizing the DNA into a nucleoprotein polymer called chromatin. The basic repeating unit of chromatin is a nucleosome, which contains a nucleosome core formed by an octamer of histone proteins containing two copies of H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 that wraps a 147 bp of the genomic DNA (50, 51). The nucleosome core is connected to the adjacent nucleosome core by a segment of linker DNA. The linker DNA is often associated with the histone protein (H1) that further compacts the genome (52–54). Finally, an array of epigenetic modifications on the histone proteins and the DNA adds more complexity to the structural and functional landscape of the human chromatin (55–57).

A direct role of chromatin structure in PIC-mediated viral DNA integration targeting has remained elusive. However, studies of purified HIV-1 IN suggest a potential functional link. For example, the DNA wrapped within nucleosomes is preferred for retroviral integration (58–62). Particularly, HIV-1 and other retroviral INs preferentially target the outward-facing major groove of the nucleosomal DNA (60–63). Evidently, the distortion of the nucleosomal DNA as it bends around the histone octamer is thought to facilitate integration into the nucleosomes. However, retroviral INs differ in how they integrate viral DNA within chromatinized DNA templates (38, 41, 64–68). Although HIV and murine leukemia virus (MLV) target nucleosome cores for integration, nucleosome arrays are less preferred for avian sarcoma virus (ASV) integration compared to analogous naked DNA (39, 41, 65). In addition, ASV IN-mediated integration is preferred into a compacted chromatin than with naked DNA or an extended nucleosome array (38). In contrast, HIV-1 IN-mediated integration was reduced into compacted chromatin. In addition, specific epigenetic modifications that are known to alter chromatin structure have also been linked to integration targeting (33, 37). For example, HIV-1 integration is positively associated with a group of histone posttranslational modifications that are linked to active transcription (33, 37, 69). Conversely, HIV-1 integration is negatively associated with modifications that inhibit transcription, such as H3 K27 trimethylation and DNA CpG methylation. The effects of epigenetic modifications on HIV-1 integration contrast with other retroviruses such as MLV, which prefers to integrate into CpG islands, and ASV, which integrates within runs of alternative CpG islands (70, 71). Similarly, cellular proteins such as LEDGF/p75, BET, and others that are recruited by viral proteins also play key roles in viral DNA integration, especially into chromatin substrates (38, 39, 41, 64, 65, 72–74). In particular, the interaction between HIV-1 IN and LEDGF/p75 is linked to integration site selection (75–86). Still, the molecular and biochemical details underlying the preference of retroviral DNA integration into specific regions of chromatin are not fully understood. There is currently a lack of studies of PIC-mediated viral DNA integration preference into physiologically relevant targets such as isolated chromatin and dechromatized genomic DNA (gDNA).

In this study, we describe a biochemical mechanism for the preference of the HIV-1 DNA integration into open chromatin. We used HIV-1 PICs extracted from acutely infected T-cell lines and measured the ability of these viral replication complexes to integrate the viral DNA into isolated chromatin, genomic DNA substrates, biochemically assembled nucleosomes, and analogous naked DNA. To study whether viral DNA integration by PICs is distinct, we carried out comparative analysis with intasome (INS)-mediated integration. Our results demonstrated that PIC-mediated integration into biochemically assembled nucleosomes without histone tail modifications was lower compared the naked DNA substrates. Notably, the addition of a trimethylated histone tail modification H3K36me3 significantly enhanced PIC-mediated integration into nucleosomes. The addition of linker DNA to the modified nucleosomes optimally supported PIC-mediated integration but not INS-mediated integration. Surprisingly, the cellular cofactor LEDGF/p75 had distinct effects on PIC compared to the INS. Furthermore, chromatin compaction by the linker histone H1° negatively regulated HIV-1 integration. Finally, using sequencing analysis, we identified integration preferences within specific regions of the nucleosomal DNA. Overall, our study provides critical biochemical evidence for HIV-1 PIC-mediated integration preference into open chromatin.

RESULTS

Chromatin is the preferred substrate for HIV-1 PIC-mediated viral DNA integration.

HIV-1 infection is dependent on the integration of the viral DNA into host chromosomes by the PIC. There is strong evidence that HIV-1 DNA is preferentially integrated into actively transcribing genes (31, 32, 36, 45). However, the biochemical determinants of integration site preference within the chromatin are not fully understood. To better understand the mechanism of HIV-1 integration into chromatin hot spots, we measured viral DNA integration into target substrates such as isolated chromatin, genomic DNA, biochemically reconstituted nucleosome core particles with or without linker DNA, and the analogous naked DNA sequences. To study viral DNA integration in a physiologically relevant system, we extracted HIV-1 PICs from SupT1 cells acutely infected with wild-type enveloped HIV-1 particles. The extracted PICs retain robust DNA integration activity in vitro (see Fig. S1A and B in the supplemental material) (87–91), and the assay is specific since the HIV-1 integrase inhibitor raltegravir (RAL) significantly inhibited viral DNA integration (see Fig. S1B).

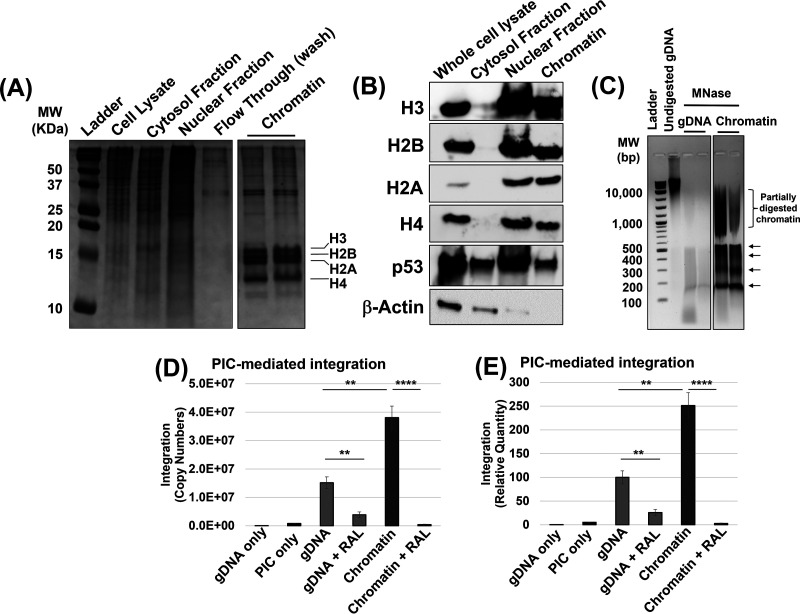

Next, we extracted chromatin from HEK293T cells by adopting a protocol that yields high-quality chromatin through isolation and purification of clean nuclei (92). The chromatin preparation contained the canonical histone proteins and lacked detectable levels of cytoplasmic protein markers (Fig. 1A and B; see also Fig. S1C). Importantly, a partial micrococcal nuclease digestion of the isolated chromatin resulted in a “ladder-like” pattern with the smallest DNA band at 150 bp (Fig. 1C; see also Fig. S13C). The ~150-bp length is equivalent to the length of DNA (147 bp) wrapped around a nucleosome (50, 51, 93). Collectively, these results demonstrate the integrity of the intact nucleosomes in the chromatin preparation. In parallel, the analogous dechromatinized genomic DNA (gDNA) substrate was prepared by deproteination of the isolated chromatin (Fig. 1C). To probe the integration into these substrates, PICs were incubated with either the chromatin or gDNA preparations containing equivalent amount of DNA (300 ng). PIC-mediated DNA integration activity was measured by using Alu-based nested qPCR (87, 89–91). The results from these measurements revealed that PIC-mediated viral DNA integration levels were significantly higher with the chromatin substrate compared to the gDNA (Fig. 1D and E). Even though substrate preference studies of HIV-1 PICs are limited, these results are consistent with prior studies using recombinant integrase showing that chromatinized substrates can support higher quantities of integration relative to naked DNA (58, 59, 61, 62, 64, 74). Notably, the chromatin substrate used in our assay contains the host factor LEDGF/p75 and a specific histone modification that are positively implicated in HIV-1 integration targeting (see Fig. S1C). Therefore, the preference of PIC-mediated integration into the chromatin is most likely driven by both the host factors and the structural elements within the nucleosomes.

FIG 1.

Chromatin is the preferred substrate for HIV-1 PIC-mediated integration. Chromatin was isolated from HEK293T cells and assessed for the histone proteins and DNA. (A) Fractions from various steps of the chromatin preparation were analyzed by using a 15% acrylamide gel and visualized by Coomassie staining. The chromatin fraction containing the canonical histone proteins H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 is shown. (B) The histone proteins were detected by Western blotting in the whole-cell lysate, the cytosol fraction, the nuclear fraction, and chromatin (left panel). In addition, cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins were probed in each fraction (right panel). (C) Protection of the chromatin DNA within nucleosomes was assessed by partial micrococcal nuclease (MNase) digestion. The arrows to the right of the gel indicate discrete DNA bands of nucleosome-mediated protection. (D) PIC-mediated integration was measured by nested-PCR and represented as the copy numbers of integrated viral DNA, using 300 ng of chromatin and deproteinated genomic DNA (gDNA) as targets. As a negative control, 1 μM RAL (the integrase strand transfer inhibitor) was used. (E) The copies of HIV-1 DNA integration were plotted relative to the integration into gDNA. The results in panel E are shown as means of the viral DNA copy numbers of at least three replicates, with the error bars indicating the standard errors of the mean (SEM). *, P < 0.05; **, P = 0.01 to 0.05; ***, P = 0.01 to 0.001; ****, P = 0.001 to 0.0001; *****, P < 0.0001.

Nucleosomes without histone tail modifications are not preferred for PIC-mediated viral DNA integration.

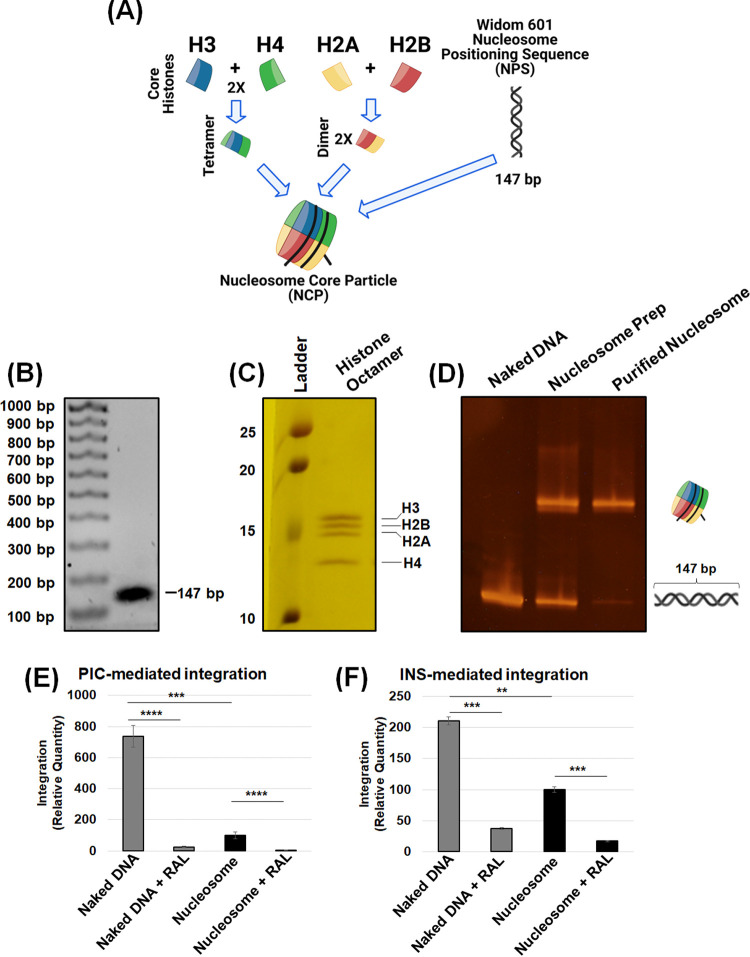

The basic repeating unit of chromatin is a nucleosome, consisting of a core histone octamer that wraps 147 bp of DNA (50, 51). A number of published studies suggest that nucleosomes are the preferred substrates of retroviral DNA integration (59–62, 64, 94). In particular, there is evidence that the outward-facing DNA within the nucleosome is targeted for retroviral DNA integration (59–62). To probe whether the nucleosome structure contributed to the enhanced integration into chromatin (Fig. 1), we measured PIC-mediated integration using biochemically assembled nucleosomes. To generate nucleosome substrates, we used the Widom 601 nucleosome positioning sequence DNA (95) and purified human recombinant histones H2A, H2B, H3C110A, and H4 (Fig. 2A). First, histone octamers were generated from purified histone proteins by a well-established stepwise biochemical assembly approach (96). Then, the 147-bp Widom 601 DNA (Fig. 2B) was added to the assembled histone octamers (Fig. 2C). Formation of the nucleosome core particle was confirmed by an electromobility shift assay (EMSA), and our purified nucleosome preparation was devoid of any free DNA (Fig. 2D).

FIG 2.

The nucleosome is a barrier to HIV-1 integration. (A) Schematic of the biochemical assembly of nucleosomes. The nucleosomes are assembled with the Widom 601 nucleosome positioning sequence and a recombinant human histone octamer. The histone octamer was assembled first by an equimolar addition of histone protein dimers H2A and H2B with the H3/H4 tetramer. (B) The 147-bp NPS (naked DNA) DNA used for nucleosome assembly was analyzed on a 1.5% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. (C) SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining visualized the presence of individual histone proteins in the octameric histone assembly. (D) The biochemical assembly of the nucleosome was analyzed by an EMSA. (E) PIC-mediated integration was assessed using 300 ng of the 147-bp naked DNA and the analogous nucleosome as targets, with RAL serving as a specific inhibitor for HIV-1 integration. (F) Intasome (INS)-mediated integration was measured using qPCR, with the naked DNA and the nucleosome serving as targets. The data are represented as the relative quantity of viral DNA integration in reference to the naked DNA, and error bars were generated from the SEM of at least three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P = 0.01 to 0.05; ***, P = 0.01 to 0.001; ****, P = 0.001 to 0.0001.

Then, equivalent amount of the nucleosomes or the analogous naked Widom DNA (300 ng) was used as the substrate to measure PIC-mediated viral DNA integration. We used specific primers (see Table 1) that amplify the junctions of integrated viral DNA into these particular target substrates by nested qPCR. Surprisingly, PIC-mediated integration into the naked DNA was significantly higher (~7-fold) compared to the nucleosomes (Fig. 2E). The specificity of the assay was demonstrated by the inhibition of PIC-mediated integration activity by 1 μM RAL with both the nucleosome and naked DNA (Fig. 2E). These results deviate from prior studies showing that nucleosomes are preferred substrates for integration compared to naked DNA. A key difference is that our study uses PICs extracted from infected cells compared to the in vitro studies of purified IN enzymes (38, 39, 59–62, 64, 65, 74). Therefore, it is likely that the PIC-associated factors play key roles in integration preference beyond what might be driven by the IN alone.

TABLE 1.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) | Binding site | Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| PIC-mediated integration (REV) | GTGCGCGCTTCAGCAAG | U5 of HIV-1 genome | PIC assay (ALL) |

| INS-mediated integration primer | AGCGTGGGCGGGAAAATCTC | INS donor DNA | INS assay (ALL) |

| Gag-PVI (REV) | GTTCCTGCTATGTCACTTCC | HIV-1 Gag sequence | |

| ALU (FWD) | GCCTCCCAAAGTGCTGGGATTACAG | Alu repeat in the human genome | PIC and INS assay with chromatin/genomic DNA |

| NPS-147-FWD | CTGGAGAATCCCGGTGC | 5′ end of the Widom 601 NPS | PIC assay and INS assay with 147-bp Widom substrates |

| NPS-147-REV | ACAGGATGTATATATCTGACACGTG | 3′ end of the Widom 601 NPS | PIC-assay and INS assay with 147-bp Widom substrates |

| NPS-247-FWD | GCTTGTCGACGAATTCAGATTCATAAGG | 5′ end of the linker DNA containing Widom 601 NPS | PIC assay and INS assay with 247-bp Widom substrates |

| NPS-247-REV | CGGATCCAGAATTCGTGATTGTAGC | 3′ end of the linker DNA containing Widom 601 NPS | PIC assay with 247-bp Widom substrates |

| 2nd Round-LTR-F (989) | TCTGGCTAACTAGGGAACCCA | R region of HIV-1 genome (LTR) | Second-round qPCR for PIC assay and PVI |

| 2nd Round-LTR-R (990) | CTGACTAAAAGGGTCTGAGG | U5 region of HIV-1 genome (LTR) | Second-round qPCR for PIC assay and PVI |

| 2nd Round-LTR-Probe (995) | [6-FAM]-TTAAGCCTCAATAAAGCTTGCCTTGAGTGC-[TAMRA] | LTR of HIV-1 genome | Second-round qPCR for PIC assay and PVI |

| 2nd Round-Gag-F2 | TCAGCCCAGAAGTAATAC | Gag of HIV-1 genome | Gag specific PVI |

| 2nd Round-Gag-R2 | CACTGGATGCAATCTATC | Gag of HIV-1 genome | Gag specific PVI |

| 2nd round-Gag-Probe | [FAM]-TCAGCATTATCAGAAGGAGCCACC-[TAMRA] | Gag of HIV-1 genome | Gag specific PVI |

To better understand the PIC-mediated DNA integration into nucleosomes, we probed whether the reduced levels of integration is PIC specific. To test this, we used HIV-1 intasomes (INS), which are formed by IN and viral DNA sequences and constitute the minimal substructures of PICs capable of carrying out viral DNA integration (97, 98). We assembled HIV-1 INS through an established biochemical approach that uses purified IN and viral DNA sequences from the long terminal repeat (LTR) region (97, 98). We used the purified recombinant HIV-1 IN containing a Ssod7 domain for solubility (98) and viral DNA mimics (25 and 27 bp) (see Fig. S2B). We evaluated INS-mediated viral DNA integration by using a qPCR-based assay to amplify the integration junctions into these specific target substrates (see Fig. S2B). Notably, this qPCR-based assay is designed to detect both half-site and full-site strand transfer. Our results show selective amplification the viral and target DNA junction only when both the INS and the target substrate were added to the reaction mixture (see Fig. S2C). Since RAL inhibited INS-mediated integration activity, the assay is specific (see Fig. S2C). Next, INS activity was measured with the naked DNA and nucleosome substrates (Fig. 2F). We observed that INS-mediated integration was significantly higher with the naked DNA compared to the nucleosome (Fig. 2F), an observation similar to the PIC activity (Fig. 2E). Interestingly, the level of reduction in INS activity into nucleosomes was ~2-fold compared to a reduction of ~7-fold in PIC activity. These observations suggest that nucleosomes confer a stronger barrier for the PICs to insert the viral DNA. Even though previous studies suggest that nucleosomes are preferred for HIV-1 integration, the source of nucleosomes in our study differs from those of previously published studies. For instance, published studies used nucleosomes and chromatinized substrates, assembled using histones derived from cellular sources (38, 39, 41, 50, 64, 65, 99). In contrast, our study used biochemically assembled recombinant nucleosomes assembled with purified histone proteins and the synthetic Widom 601 sequence that forms highly stable nucleosomes compared to native DNA sequences (94, 95, 100). Thus, the nucleosomes in our study lack any histone tail modifications, whereas the cellular histones used in the previously published studies most likely contain physiologically relevant and possibly integration-stimulating histone modifications. Taken together, these observations suggest that highly stable nucleosomes without any histone tail modifications are not preferred for HIV-1 DNA integration over the analogous naked DNA by both the PIC and the INS.

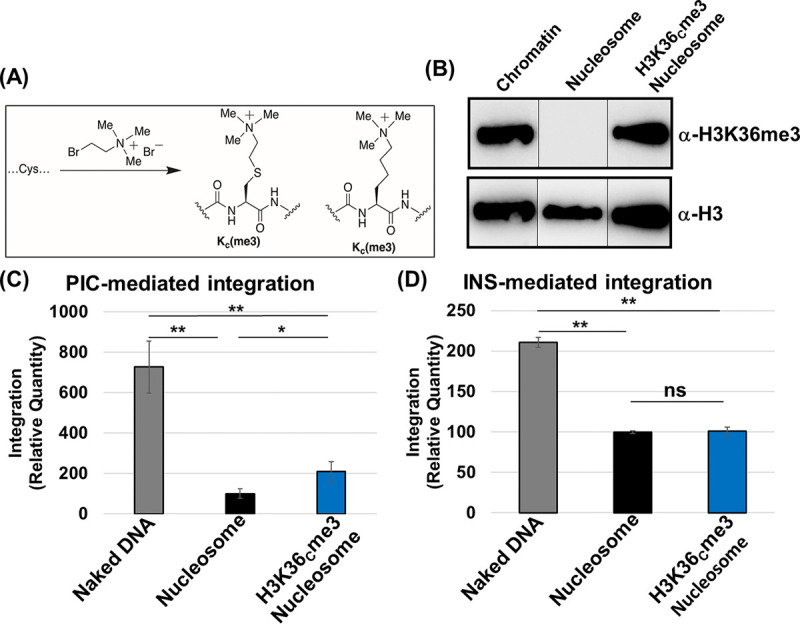

Nucleosomes containing a trimethylated histone 3 at lysine 36 enhanced PIC-mediated viral DNA integration.

In chromatin, nucleosomes are decorated with chemical modifications primarily in the extended tails of the histone proteins (56, 101, 102). In the case of HIV-1, histone modifications associated with active transcription are positively correlated with integration preference, whereas histone marks indicative of heterochromatin and transcriptionally silent genes are negatively associated with DNA integration (33–35, 37, 40, 45). Given our unexpected results that nucleosomes without histone modifications are not preferred for HIV-1 DNA integration in vitro (Fig. 2), we assessed whether nucleosomes containing specific histone modifications are required for optimal integration. One of the histone modifications most commonly associated with HIV-1 integration preference in sequencing studies is the trimethylated histone 3 at lysine 36 (H3K36me3) (33, 37, 40, 42, 45, 46, 66, 103, 104). As a proof of concept, we tested whether nucleosomes containing the H3K36me3 mark affects integration activity of both PICs and INS. We assembled nucleosomes with the biochemical mimetic (H3K36Cme3) of the H3K36me3 modification by an alkylation reaction (Fig. 3A). The H3K36Cme3 mark itself is not known to enhance nucleosomal DNA unwrapping (105, 106) and is biochemically indistinguishable from the posttranslational modification found in cells (107). Our Western blot analysis confirmed the presence of H3K36me3 in isolated chromatin and H3K36Cme3-modified nucleosomes (Fig. 3B). When we assessed PIC-mediated integration activity using the H3K36Cme3-modified nucleosomes as the substrate, we observed a significant increase in integration compared to the analogous unmodified nucleosome substrate (Fig. 3C). However, PIC activity with the H3K36Cme3-modified nucleosome substrate remained significantly lower compared to the analogous naked DNA substrate (Fig. 3C; see also Fig. S3B and C). To further study this phenotype, we measured INS-mediated integration activity using the naked DNA, nucleosomes, and H3K36Cme3-modified nucleosomes as target substrates. In stark contrast to the PIC activity (Fig. 3C), INS activity with the H3K36Cme3-modified nucleosome substrate showed no measurable difference relative to the unmodified nucleosomes (Fig. 3D; see also Fig. S3D). Interestingly, the INS activity remained higher with the naked DNA substrate compared to either the modified or the unmodified nucleosome substrates (Fig. 3D; see also Fig. S3D). These observations strongly suggest that the H3K36me3 modification specifically promotes viral DNA integration, by the PIC but not by the INS, into nucleosomes.

FIG 3.

Nucleosomes containing trimethylated histone 3 at lysine 36 enhanced PIC-mediated integration. (A) Schematic illustrating the insertion of the H3K36me3 mimetic by site-directed mutagenesis of the H3 K36 to cysteine (K36C). The K36C H3 undergoes alkylation to functionalize the K36C to create a biochemical mimic of the histone 3 trimethylation (H3KC36me3). (B) Western blot analysis of the H3K36me3 and histone H3 in the H3K36Cme3 nucleosome compared to the unmodified nucleosome and the isolated chromatin. (C) PIC-mediated integration with the naked DNA, nucleosome, and H3K36Cme3 nucleosome. The data were analyzed with reference to the naked DNA. (D) The INS-mediated integration was then assessed by comparing the naked DNA, nucleosome, and H3K36Cme3 nucleosome. The error bars were determined by the SEM of at least three independent replicates. *, P < 0.05; **, P = 0.01 to 0.05.

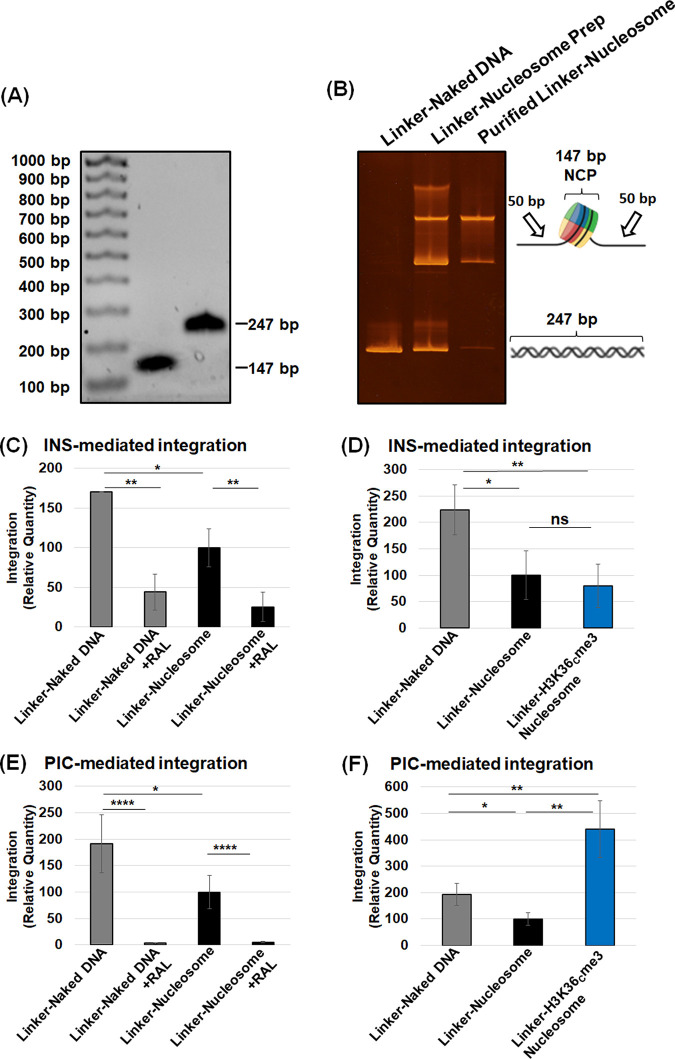

Nucleosomes harboring H3K36me3 and linker DNA optimally promoted PIC-mediated viral DNA integration.

Our results show that unmodified nucleosomes without flanking linker DNA are not preferred for integration compared to the analogous naked DNA (Fig. 3C and D). In the cellular context, nucleosomes are connected to adjacent nucleosomes by a linker DNA (93, 108). Therefore, we used nucleosomes mimicking the chromatin by assembling nucleosomes containing an additional 50 bp of linker DNA flanking both sides of the 147-bp Widom 601 DNA (Fig. 4A and B; see also Fig. S4A). Imperfect placement of DNA longer than 147 bp in the nucleosomes (109) most likely explains the presence of more than one population of nucleosomes (Fig. 4B). First, we measured INS-mediated integration into the 247-bp naked DNA and compared it to the nucleosomes assembled with the same DNA (Fig. 4C). We observed a reduction in the integration with the nucleosomes compared to the naked DNA, similar to our results with 147-bp naked DNA and nucleosome substrates (Fig. 2E and F). Moreover, results with the linker nucleosome without or with H3K36Cme3 modification indicated that histone trimethylation has a negligible effect on INS activity (Fig. 4D). Comparison of all three linker substrates surprisingly showed the preference of INS-mediated integration into the naked DNA (Fig. 4D). Next, we tested PIC-mediated integration with all the linker substrates. The naked 247-bp DNA was preferred for PIC activity over the linker nucleosomes (Fig. 4E), similar to the data of INS activity (Fig. 4C and D) and PIC activity with nonlinker substrates (Fig. 3C and D). Interestingly, the results of PIC activity with the 247-bp DNA and linker nucleosomes with H3K36Cme3 revealed a significant increase in integration with the H3K36Cme3-modified nucleosome substrate (Fig. 4F; see also Fig. S4D and E). Comparative analysis of PIC activity with all of the linker substrates showed that the linker H3K36Cme3 nucleosomes supported significantly higher integration than the linker nucleosomes and naked DNA (Fig. 4F). This is in stark contrast to the results with INS (Fig. 4D), strongly suggesting that the combination of the H3K36me3 and the linker DNA provides a biochemically favorable environment for the HIV-1 PIC-mediated viral DNA integration. Furthermore, these data also indicate that only the PIC, but not the PIC-substructure INS, contains the necessary factors/mechanisms to mediate HIV-1 DNA integration into H3K36me3-modified nucleosomes.

FIG 4.

The nucleosome containing linker DNA and the H3K36Cme3 is an optimal substrate for PIC-mediated integration. The nucleosome containing 50 bp of linker DNA flanking the Widom 601 NPS (linker-naked DNA) was assembled, resulting in a nucleosome with a linker substrate that is 247 bp. (A) The 147- and 247-bp nucleosome positioning sequence DNA was analyzed on a 1.5% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. (B) The biochemical assembly of nucleosomes with the 247-bp DNA was analyzed by EMSA. (C) The relative quantity of INS-mediated integration was measured with the linker-naked DNA, compared to the linker-nucleosomal DNA. The integrase inhibitor, RAL, was included as a control for integration. (D) The linker-naked DNA, linker-nucleosome, and linker-H3K36Cme3 were compared for INS-mediated integration relative to the linker-naked DNA. (E) PIC-mediated integration was assessed with the linker-naked DNA and linker-nucleosome. (F) PIC-mediated integration was measured by comparing the linker-naked DNA, linker-nucleosomes, and linker-H3K36Cme3. All the results are shown as the relative integration quantity and represent the means of at least three independent experiments. Error bars represent the SEM (*, P < 0.05; **, P = 0.01 to 0.05; ****, P = 0.001 to 0.0001).

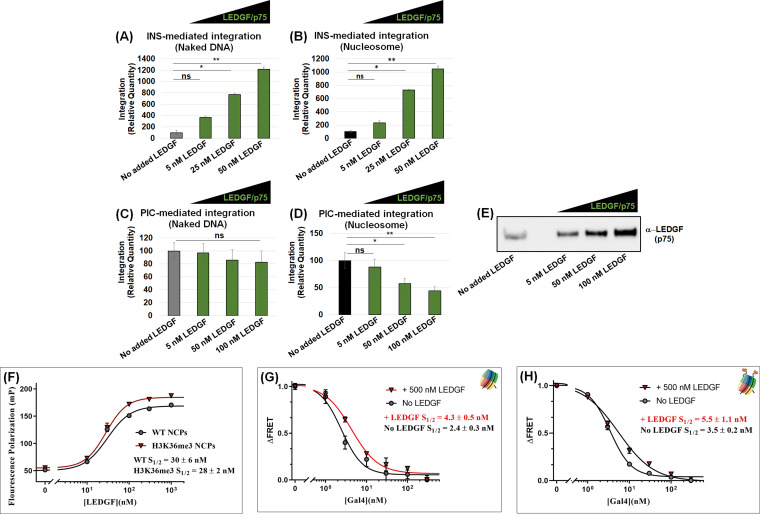

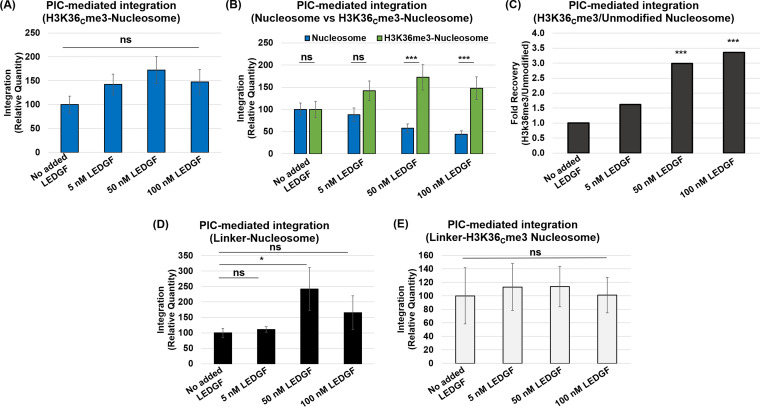

LEDGF/p75 addition stimulated INS-mediated viral DNA integration but reduced PIC-mediated viral DNA integration.

The PIC utilizes several host proteins to efficiently integrate the viral DNA into the host chromosomes, most notably CPSF6 and LEDGF/p75 (73, 110–113). LEDGF/p75 is known to bind mitotic chromatin (79, 114); however, the consequence of this binding is just recently beginning to emerge, particularly in the context of transcription (115). Early studies identified LEDGF/p75 as the key host protein to support HIV-1 integration (75–78, 83–85, 99). In particular, LEDGF/p75 binds to an integrase dimer at the catalytic core domain, plays a role in targeting integration toward actively transcribing genes, and stimulates the strand transfer activity of lentiviral integrases, including HIV, with both naked and chromatinized substrates (116–119). Therefore, to better understand our contrasting results in Fig. 4, we tested the effects of LEDGF/p75 on INS- and PIC-mediated viral DNA integration using nucleosome and naked DNA substrates. First, increasing amounts of purified LEDGF/p75 were supplemented to the INS reaction mixture containing the nucleosomes or naked DNA substrates. We observed a dose-dependent enhancement of INS-mediated integration into the naked DNA with increasing concentrations of LEDGF/p75 (Fig. 5A). LEDGF/p75 addition also stimulated INS activity with the nucleosomes in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 5B). Surprisingly, increasing amounts of LEDGF/p75 did not enhance PIC activity with the naked DNA albeit a slight but nonsignificant decrease at the highest concentrations (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, LEDGF/p75 addition significantly reduced PIC activity with the unmodified nucleosome substrate (Fig. 5D), in contrast to the enhanced effect observed with the INS (Fig. 5A and B). Interestingly, Western blot analysis showed that endogenous LEDGF/p75 is present in our extracted PIC preparation (Fig. 5E). Therefore, it is plausible that the PIC-associated LEDGF/p75 levels are sufficient for viral DNA integration and that additional amounts of the protein confer an inhibitory effect.

FIG 5.

LEDGF/p75 addition stimulated INS-mediated integration but reduced PIC-mediated integration with nucleosomes. (A and B) INS-mediated integration (25 nM) was measured in the presence of the integration cofactor LEDGF/p75. LEDGF/p75 was added to the indicated reaction mixtures at 5, 10, and 25 nM to both the naked DNA and the nucleosome substrate. (C and D) PIC-mediated integration was measured in the presence of LEDGF/p75 addition with both the naked DNA and the nucleosome substrate. (E) Western blot analysis for LEDGF/p75 in the isolated PIC preparation and in PICs supplemented with the recombinant LEDGF/p75 protein. (F) A fluorescence polarization assay was performed with fluorescein-labeled nucleosome core particle (NCP) to determine the LEDGF/p75 binding kinetics (S1/2) to the nucleosomes. (G and H) The ensemble FRET measurements were detected by Cy3-Cy5 NCP (Cy3 at the end of the NPS and Cy5 at the H2A K119C) and with titrations of GAL4 in the presence of LEDGF/p75 at saturating amounts of the unmodified NCP and H3K36Cme3-NCP. The error bars represent the SEM of at least three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P = 0.01 to 0.05.

To understand the mechanism by which LEDGF/p75 reduced PIC-mediated integration into the nucleosome, we employed a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based binding assay. This FRET assay utilizes a 5′-Cy3-labeled nucleosome positioning sequence reconstituted into a nucleosome containing a Cy5 label on the H2A K119C within the histone octamer (120, 121). The positioning of these two fluorophores allowed for the measurement of nucleosome accessibility near the DNA entry/exit site. Since LEDGF/p75 is known to bind to the nucleosome at the entry/exit site (122), this assay is uniquely suited for our study. In this assay, a GAL4 binding sequence was cloned into the Widom 601 DNA (at nucleotide positions 6 to 25) to determine GAL4 accessibility to the nucleosome in direct competition with LEDGF/p75 (see Fig. S5C) (105, 109, 120). Initially, we demonstrated that LEDGF/p75 binds to the nucleosome by EMSA (see Fig. S5A), consistent with earlier studies (122, 123). This LEDGF/p75 binding to the nucleosome requires the DNA-binding domains, PWWP and AT-hooks, since a LEDGF/p75 mutant containing only the integrase-binding domain (IBD) failed to bind the nucleosome (see Fig. S5B). We observed that in the absence of GAL4, the addition of increasing amounts of LEDGF/p75 did not alter the FRET efficiency (see Fig. S5D). These results established that upon binding to the nucleosome, LEDGF/p75 addition minimally affects nucleosomal DNA unwrapping. Using fluorescence polarization analysis, we observed that LEDGF/p75 binds to both the unmodified nucleosome and H3K36Cme3 nucleosome substrates with comparable affinities of 30 and 28 nM, respectively (Fig. 5F). We then determined the nucleosome accessibility to GAL4 in the presence of LEDGF/p75 (Fig. 5G and H). LEDGF/p75 addition reduced the accessibility of GAL4 to the nucleosome by ~2-fold. Likewise, GAL4 accessibility to the DNA in the nucleosome containing H3K36me3 was also reduced by LEDGF/p75. Collectively, these results show that LEDGF/p75 can physically or sterically block trans-factors from gaining access to the DNA within the nucleosome. Thus, an excess of LEDGF/p75 likely reduces PIC-mediated integration by blocking access of the PIC-associated viral DNA to the nucleosomal DNA.

The H3K36me3 modification relieved the LEDGF/p75-mediated reduction of PIC-mediated viral DNA integration.

Our results indicated that the nucleosome features (histone tail modification and DNA length) and the chromatin-binding protein LEDGF/p75 directly influence viral DNA integration. The combination of the H3K36Cme3 and linker DNA within the nucleosome has an additive effect on PIC-mediated viral DNA integration (Fig. 4F). In contrast, PIC activity with the nonlinker nucleosome showed a LEDGF/p75-mediated reduction (Fig. 5D). To reconcile these disparate results of LEDGF/p75 with distinct substrates, we measured PIC activity using the linker substrates in the presence of LEDGF/p75. First, we observed that with the H3K36Cme3-modified nucleosome without the linker DNA, LEDGF/p75 addition did not inhibit PIC activity (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, when we juxtaposed the LEDGF/p75 addition data of the unmodified nucleosomes to the H3K36Cme3-modified nucleosome, the data indicated that the H3K36me3 mark relieves the LEDGF/p75-mediated reduction of PIC activity (Fig. 6B). Further analysis revealed a significant ~3-fold recovery of PIC activity with the H3K36Cme3-modified substrate over the unmodified substrate in the presence of 50 to 100 nM LEDGF/p75 (Fig. 6C). Intriguingly, the presence of linker DNA also relieved the LEDGF/p75-mediated reduction of PIC activity (Fig. 6D), an observation in clear contrast to the dose-dependent reduction of PIC activity with the unmodified nucleosome (Fig. 5D). Finally, PIC activity with the linker H3K36Cme3-modified nucleosome showed no significant effect of LEDGF/p75 addition on integration (Fig. 6E). Notably, the raw integration copy numbers indicated that the integration quantity is relatively high (see Fig. S6C), suggesting that in vitro integration occurs at an optimal level with the nucleosome substrate containing both the H3K36Cme3 and linker DNA, with the endogenous LEDGF/p75. These observations establish that the presence of linker DNA and the H3K36me3 mark within a nucleosome are biochemically favored for HIV-1 integration by the PIC.

FIG 6.

The H3K36Cme3 nucleosome and linker DNA supported PIC-mediated integration in the presence of LEDGF/p75. (A) PIC-mediated integration was measured using H3K36me3-nucleosomes as targets in the presence of LEDGF/p75 (5, 50, and 100 nM). Integration data are presented relative to the PIC reactions without added LEDGF/p75. (B) Comparative analysis of the relative PIC-mediated integration with the unmodified nucleosome to the H3K36Cme3-nucleosome in the presence of LEDGF/p75. (C) The fold change was calculated between the unmodified nucleosome and the H3K36me3-modified nucleosome effects on PIC-mediated integration in the presence of LEDGF/p75. (D) PIC-mediated integration was measured with LEDGF/p75 supplementation to the unmodified nucleosomes containing linker DNA. (E) PIC-mediated integration with the H3K36Cme3 nucleosome containing linker DNA in the presence of LEDGF/p75 is plotted relative to the assay without LEDGF/p75 supplementation. The error bars represent the SEM of at least three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; ***, P = 0.01 to 0.001.

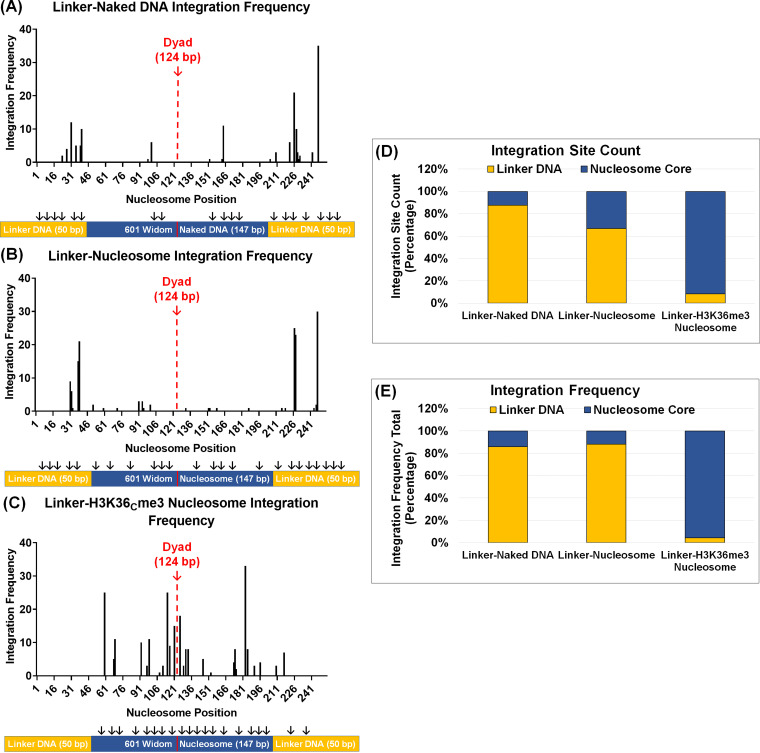

The nucleosome core is preferentially targeted for integration when modified with H3K36me3.

Our results identified that nucleosomes with linker DNAs and histone tail modification akin to open chromatin-enhanced PIC-mediated viral DNA integration (Fig. 4F; see also Fig. S4D and E). In the human genome, the H3K36me3 mark is primarily located within the gene body of actively transcribing genes (124–126). The H3K36me3 mark is associated with promoting polymerase II elongation through the gene body, gene splicing, suppression cryptic transcription, and DNA damage repair (127–130). While sequencing studies have correlated the proximity of H3K36me3 to HIV-1 integration targeting (103, 131, 132), a direct role of this epigenetic mark in the local viral DNA targeting within a nucleosome remains unknown. Therefore, to understand the consequence of the H3K36Cme3 mark in viral DNA integration, we carried out deep sequencing of the integration reactions with the linker substrates (99). Duplicate integration reactions of the naked DNA with linker, unmodified nucleosome with linker, and H3KC36me3 nucleosome with linker substrates were PCR amplified, concentrated, and spectrophotometrically analyzed. Amplicons were deep sequenced, and we quantified reads that contained sequences of the HIV-1 5′ LTR adjoined to the DNA sequence for the naked DNA, nucleosome, and H3K36Cme3 nucleosome targets with linkers. Analysis of the sequencing data identified integration junctions and revealed distinct integration patterns in each of the substrates (see Fig. S8 and 10). With the linker containing naked DNA, integration junctions were identified throughout the length of the sequence with an overrepresentation of viral DNA integration near the target DNA ends (Fig. 7A; see also Fig. S8). Similarly, the integration junctions were mostly found in the linker DNA regions of the nucleosome (Fig. 7B; see also Fig. S9). In contrast, the integration junctions within the linker containing H3K36Cme3 nucleosome were identified predominantly in the nucleosome core sequence (Fig. 7C; see also Fig. S7 and Fig. S10). The location of the integration sites within the linker H3K36Cme3 nucleosome was mapped near the entry/exit sites of the nucleosome. Importantly, this is the location of the H3-tail protrusion between the nucleosomal DNA (55, 120, 122), indicating that the HIV-1 PIC is drawn toward the H3K36me3 mark when engaged with a nucleosome during an integration event.

FIG 7.

HIV-1 DNA integration is preferentially directed into the core of the H3K36Cme3 containing nucleosomes. To study HIV-1 integration preference, the DNA from the integration reactions was PCR amplified and subjected to next-generation sequencing. The integration frequency within the linker substrates was determined by quantifying the integration junctions. The integration frequency is plotted as a histogram for the naked DNA with a linker (A), the nucleosome with the linker (B), and H3K36Cme3 with linker substrates (C). (D) After the integration sites within the linker containing DNA substrates were quantified, the percentages of sites within the linker sequences and nucleosome core sequence were plotted for comparative analysis. (E) The frequency of integration junctions at a particular site within the sequence was then determined. The integration frequency in the linker sequences and the nucleosome core sequence was quantified as a percentage of the total integration sites.

To further understand these sequencing data, we quantified the integration site counts as a percentage of the total integration events. These analyses revealed that the linker naked DNA and linker nucleosome comprised ~87% and ~67% of the junctions within the linker DNA, respectively (Fig. 7D). Distinctly, the linker H3K36me3 nucleosome contained over ~90% of the integration junctions adjoined in the nucleosome core sequence. Integration frequencies varied considerably between unmodified and H3K36Cme3-modified nucleosomes, wherein the nucleosome core of the linker H3K36Cme3-modified nucleosome contained ~95% of the integration junctions (Fig. 7E; see also Fig. S7B). However, the frequency of integration within the nucleosome core was only ~15% with the linker DNA and linker nucleosome lacking any histone modifications (Fig. 7E; see also Fig. S7B). Collectively, these results indicate that H3K36me3 modification promotes HIV-1 integration into specific regions of the nucleosome.

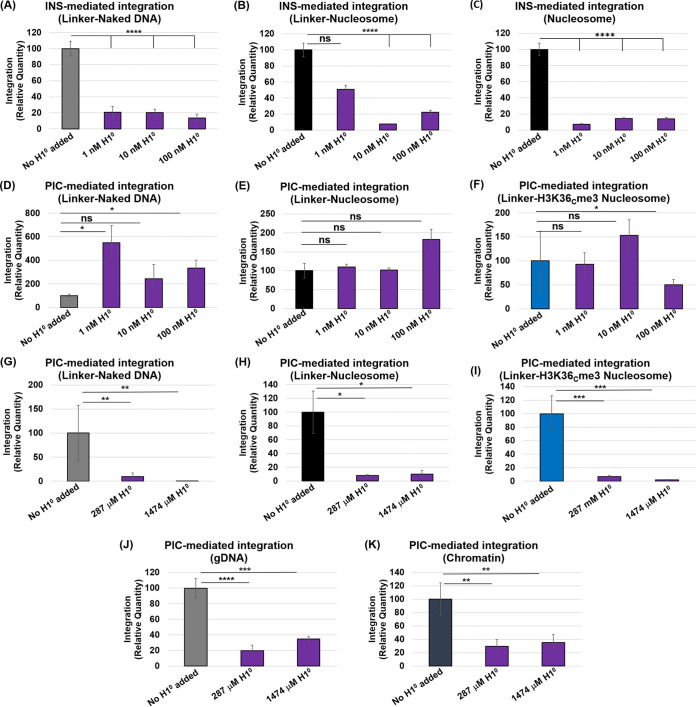

Chromatin compaction by histone H1 inhibited HIV-1 DNA integration.

To further understand the role of chromatin structure on HIV-1 integration, we tested the effects of H1 protein on INS and PIC activity. Linker histone H1 reduces chromatin accessibility by facilitating chromatin compaction (53, 133) through the direct interaction with the linker DNA near the entry/exit location of the nucleosome and at the nucleosome dyad (52, 134). A previous study has reported that H1-mediated compaction of nucleosome arrays can reduce HIV-1 integrase activity relative to open (noncondensed) chromatinized substrates (38). Therefore, we measured HIV-1 DNA integration by both PIC and INS in the presence of increasing concentrations of purified recombinant histone H1° protein. Our results revealed that INS-mediated integration was significantly reduced in the presence of nanomolar concentrations of H1° protein (Fig. 8) (Fig. 8A to C). The inhibitory effect of H1 was universally observed with the linker naked DNA, as well as, with nucleosomes without or with linker DNA. Surprisingly, PIC-mediated integration was not inhibited in the presence of nanomolar concentrations of H1° protein (Fig. 8D to F). Rather, with the linker substrates, H1° either modestly enhanced PIC activity with the linker naked DNA or had a minimal effect with both the unmodified and the H3K36me3-modified linker nucleosome substrates (Fig. 8D to F). Then, we tested the effects of H1° at saturating concentrations of 287 and 1,474 μM, which correspond to 1:1 and 1:5 molar ratios to the substrate concentrations, respectively. At these concentrations, the PIC activity was significantly inhibited with the naked DNA and unmodified and H3K36Cme3-modified nucleosome substrates containing the linker DNA (Fig. 8G to I). Finally, we tested the effects of H1° protein addition on PIC activity using chromatin and dechromatinized gDNA substrates. After preincubating the substrates with saturating concentrations of H1°, we observed significantly reduced PIC-mediated integration with both substrates (Fig. 8J and K; see also Fig. S13E and F). Notably, nanomolar amounts of H1° addition did not reduce PIC activity with the genomic DNA and chromatin substrates (see Fig. S12A to D).

FIG 8.

H1° reduces HIV-1 DNA integration. To probe the effects of H1 on HIV-1 integration, INS-mediated integration [25 nM] was first tested with the linker-naked DNA (A), the linker-nucleosome (B), or the non-linker-nucleosome (147 bp) (C) preincubated with recombinant H1° (1, 10, or 100 nM). The results are the average relative quantities with reference to the assay lacking H1° addition. The PIC-mediated integration was then measured with linker-naked DNA (D), linker-nucleosome (E), and linker-H3K36Cme3 nucleosome (F) that were preincubated with 1, 10, or 100 nM H1°. (G to I) Next, either 287 or 1,474 mM H1° was added to the PIC-mediated integration measurements with the linker-naked DNA, the linker-nucleosome, and the linker-H3K36Cme3 nucleosome substrates. The mM concentrations of H1° reflect amounts that show, respectively, 1:1 and 1:5 (wt/wt) stoichiometry of the substrate concentrations. The data shown are the relative quantities of the PIC integration relative to the assay lacking H1° addition. PIC-mediated integration was measured with gDNA (J) and chromatin (K) that were incubated on ice with 287 and 1,474 mM H1°. All data represent the means of at least three independent experiments, with the error bars representing the SEM (*, P < 0.05; **, P = 0.01 to 0.05; ***, P = 0.01 to 0.001; ****, P = 0.001 to 0.0001).

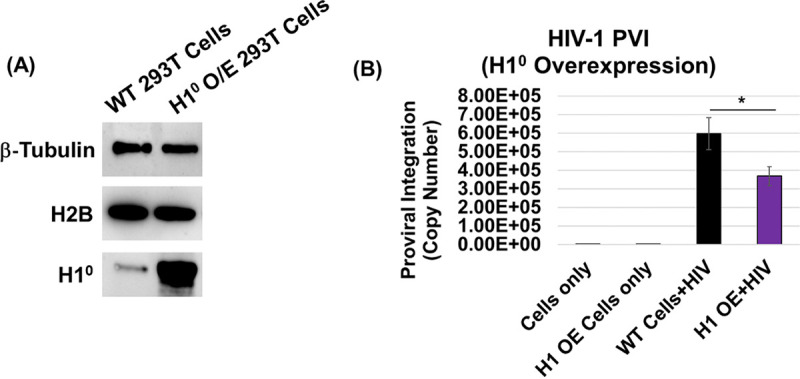

Finally, to determine whether these in vitro biochemical effects translate into a cellular context, we probed whether H1 expression regulates HIV-1 integration into human chromosomes in infected cells. To assess this, we overexpressed H1° in HEK293T cells before inoculation with pseudotyped HIV-1 virions. H1° overexpression in these cells was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 9A). Importantly, there is evidence that H1° overexpression does not alter cell viability (135). The genomic DNA was extracted from the WT and H1°-overexpressing cells, and the proviral integration (PVI) was measured using the nested Alu-Gag PCR method (87, 90, 136). Our results revealed that proviral DNA integration was reduced by ~50% in the H1°-overexpressing cells relative to the control infected cells (Fig. 9B), implying a negative correlation between H1 expression and HIV-1 integration. Collectively, these results provide evidence that chromatin compaction by H1 reduces HIV-1 integration and, by extension, supports the model that open chromatin structure is preferred for viral DNA integration.

FIG 9.

Histone H1 expression negatively regulates HIV-1 integration. (A) Linker histone H1° was overexpressed in HEK293T cells, H1° protein was probed by Western blot analysis, and the same blot was reprobed for β-tubulin and histone protein H2B as loading controls. (B) Proviral integration in the HEK293T cells overexpressing H1°. Cells were transfected with the pEV833 (GFP) expression construct for H1° and then inoculated with VSVg-dEnv-HIV-1 (GFP) particles. At 24 h postinoculation, HIV-1 proviral DNA integration (PVI) was quantified by nested Alu-PCR. All data represent at least three independent experiments, and the error bars represent the SEM (*, P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

HIV-1 infection is dependent on the integration of the viral DNA into genic hot spots of host chromosomes (11). These hot spots contain actively transcribing genes that are epigenetically marked with histone tail modifications representative of open chromatin structure (33, 37, 40, 42, 45, 46). However, the exact role of viral and host factors that program the PIC to integrate the viral DNA into these hot spots remains largely unclear. While specific chromatin features are associated with HIV-1 integration targeting, establishing a functional link between the markers of open chromatin and HIV-1 integration preference has been challenging (66, 68, 74, 137). To address this long-standing challenge, we employed a biochemical approach involving the extraction of PICs from acutely infected cells and quantified viral DNA integration activity in vitro (see Fig. S1A and B) (87, 89, 90). We used isolated chromatin, genomic DNA, in vitro assembled nucleosomes, and the analogous 147-bp naked DNA (Widom 601) to define the target substrate preference for HIV-1 DNA integration. Using this approach, we identified that the H3K36me3 histone modification, an epigenetic histone mark of active transcription, plays a direct role in HIV-1 DNA integration preference. In particular, our results show that nucleosomes assembled with the histone H3K36me3 are a preferred target and HIV-1 DNA integration predominantly occurred within the DNA wrapped around the nucleosome core. The H3K36me3 mark also relieved an unexpected LEDGF/p75-mediated block on HIV-1 DNA integration into the nucleosome. Finally, the histone H1 protein that induces compaction of chromatin significantly reduced HIV-1 DNA integration into nucleosomes, naked DNA, and chromatin substrates. Collectively, these studies establish a biochemical link between open chromatin structure and HIV-1 integration preference.

Retroviruses must complete an obligate integration step in order to propagate. Different genera of retroviruses employ distinct mechanisms to direct viral DNA integration into specific genomic regions of the host (32, 37, 65). However, the molecular and biochemical mechanisms that drive HIV-1 DNA integration into specific genomic regions in the human chromatin are not fully understood. This is in part due to the complexity of the structural landscape of the human chromatin coupled with the lack of complete knowledge of the PIC function and composition. Nucleosomes, the organizing unit of chromatin, regulate access to the genomic DNA through numerous intrinsic biochemical and structural mechanisms (55–57). These structures also allow access to the nucleosomal DNA for genomic functions such as DNA replication, RNA transcription, and DNA damage repair. The near-meta-stable nature of the nucleosomes, driven by structural and conformation mechanisms involves (i) the intrinsic binding affinity of the histone octamers, (ii) posttranslational modifications of the histone proteins and the DNA, (iii) the competitive or cooperative binding of other chromatin binding factors, and (iv) active translocation by ATP-dependent remodeling complexes (138–140). With the exception of prototype foamy virus IN (94, 141–146), the mechanisms by which most retroviruses counter the intrinsic structural and conformational barriers to access the nucleosomal DNA to insert their viral DNA are not fully understood. Nonetheless, biochemical studies of MLV PICs, together with purified MLV and HIV IN, show a preference for the nucleosomal DNA relative to naked DNA as targets of integration (59–62). The curvature of nucleosomal DNA bending around the histone octamers or even the histone proteins themselves seems to impact viral DNA integration preference (62, 63, 68, 137, 147). Conversely, the integration activity of recombinant HIV-1 IN can also be reduced with biochemically assembled target substrates such as nucleosomes and chromatin arrays (39, 41, 65). Our results showing enhanced viral DNA integration into chromatin-bound DNA relative to the dechromatinized genomic DNA (Fig. 1D and E) provide biochemical evidence for the substrate preference of the HIV-1 PIC. Therefore, we sought to tease out the contribution of the nucleosome structure and host factors to integration preference.

To understand the mechanism of chromatin preference for HIV-1 DNA integration, we assembled nucleosomes with the 147-bp Widom 601 nucleosome positioning DNA sequence (Fig. 2A to D) (95, 96). This approach generates compositionally uniform and precisely positioned nucleosomes opposed to the cellular sources for histones/chromatin that contain highly diverse nucleosomes marked with an array of histone and DNA modifications (56, 148, 149). Most importantly, the biochemically assembled nucleosome is uniquely suited to test whether the nucleosomes without any histone tail modification and the analogous naked DNA can serve as the substrates for HIV-1 DNA integration. Given the abundance of studies reporting enhanced HIV-1 integration with nucleosomes (59–61, 63, 64, 74), we anticipated that HIV-1 PIC activity would be stimulated with nucleosomes. To our surprise, we observed higher viral DNA integration with the naked DNA rather than the nucleosomes by both HIV-1 PICs and INS, the preassembled and purified PIC substructures (Fig. 2E and F). Since the nucleosomes used in our assay are devoid of any histone tail modifications, our results suggest that the DNA wrapped around naked nucleosomes lacks the biochemical and/or structural determinants to support efficient HIV-1 DNA integration. Moreover, there are studies that report nucleosome dense chromatin arrays are less preferred for HIV-1 integrase activity relative to the analogous naked DNA (39, 41, 65). Furthermore, the Widom 601 DNA used in these experiments is optimized for binding to the nucleosome with high affinity (94, 95, 100). This could impose a strong steric hindrance on the access and insertion of the viral DNA into nucleosome-bound DNA, whereas the naked DNA substrate possesses no such biochemical or structural limitation. Even though HIV-1 DNA integration is not specific for target DNA sequence (30), future studies using nucleosomes assembled with human DNA sequences like the D02 (94) would be valuable to determine the impact of DNA-histone octamer binding on PIC- and INS-mediated integration. In addition, it is important to note that the previous studies showing enhanced integration into nucleosome-bound DNA were derived from disparate chromatinized substrates, such as chicken erythrocytes, yeast, and SV40 minichromosomes, a mouse mammary tumor virus sequence mononucleosome, and a heterogeneously positioned chimeric dinucleosome (59–62). Moreover, the histones used in subsequent nucleosome reconstitution studies were from a cellular source (HeLa cells or chicken erythrocytes) that most likely retained the native posttranslational modifications that could influence viral DNA integration (38, 39, 64, 65, 74, 99). Therefore, our results suggest that the DNA wrapped within the nucleosomes lacking any histone tail modifications or linker DNA sequences is not a preferred substrate for HIV-1 DNA integration.

Chromatin structure is broadly categorized into open or euchromatin and closed or heterochromatin state (93, 150). Heterochromatin represents a highly condensed, gene-poor, and transcriptionally silent state, whereas euchromatin is less condensed, gene-rich, and more easily transcribed (151). Multiple features of chromatin, including histone modifications, DNA methylation, and small RNAs, are involved in higher-order chromatin structure and thus facilitate or prevent access to the nucleosomal DNA (152, 153). Notably, histone tail modifications characteristic of open chromatin are positively correlated with HIV-1 DNA integration preference (33, 36, 37, 40, 42, 44, 45, 104, 111). Conversely, histone modifications that define DNA compaction into a heterochromatin state are negatively associated with HIV-1 integration. In particular, the H3K36me3 modification is positively correlated with HIV-1 DNA integration across various published data sets (33, 37, 40, 42, 45, 46, 104, 154). Although the underlying mechanism by which H3K36me3 affects HIV-1 integration targeting is unclear, H3K36me3 is an abundant and highly conserved chromatin modification within the body of transcriptionally active genes (124–126). H3K36me3 also plays critical roles in the regulation of transcription elongation, DNA repair, the prevention of cryptic start sites, pre-mRNA splicing, and processing (127–130). Notably, H3K36me3 may play a role in tethering the PIC to the actively transcribing genes to facilitate HIV-1 DNA integration through the host factor LEDGF/p75 (42, 45, 66, 122, 130, 131). Genetic domain swamping and pharmacological inhibition of LEDGF/p75 binding to the HIV-1 IN results in a shift in integration sites away from the H3K36me3 mark (131, 132, 155, 156). Accordingly, we observed higher PIC-mediated DNA integration into the nucleosomes containing H3K36Cme3 compared to the unmodified nucleosomes (Fig. 3C and 4F; see also Fig. S3C and S4D). The level of viral DNA integration into the H3K36Cme3 nucleosome (147 bp) was lower compared to the naked DNA (Fig. 3C; see also Fig. S3B). Even though our results cannot fully explain the exact mechanism, the nucleosomes used in our study contain a single histone modification in contrast to the nucleosomes within native chromosomes (or natively sourced histones) that are decorated with epigenetic histone and DNA modifications (38, 39, 41, 59–62, 64, 65, 74, 99). Nevertheless, the presence of a linker DNA optimally stimulated PIC-mediated DNA integration into the H3K36Cme3-modified nucleosomes (Fig. 4F; see also Fig. S4E). The preference for the H3K36Cme3-modified nucleosomes with a linker DNA by the PICs was not observed with the INS (Fig. 3D and Fig. 4D). These data are consistent with other biochemical studies that reported a negligible effect by histone methylation marks associated with active transcription on HIV-1 IN or preassembled INS activity (66, 68, 74). Notably, these results strongly suggest that the recognition of the H3K36me3 mark is specific to the PIC and is probably mediated by a viral and/or host factor(s) other than the IN enzyme alone. The HIV-1 PIC preference for integration into the linker H3K36me3-modified nucleosomes also aligns with studies that demonstrated HIV-1 IN preferentially targets regions within chromatin arrays containing less nucleosome density and consequently longer linker DNA (39, 65). Structural studies of LEDGF/p75 with H3K36Cme3 nucleosomes revealed that LEDGF/p75 bound nucleosomes containing both linker DNA and the H3K36me3 mark more efficiently than nucleosomes lacking linkers (122). Consequently, the H3K36me3-modified nucleosome with linker DNA may serve as a better binding partner for LEDGF/p75, which, in turn, supports greater quantities of PIC-mediated integration (see Fig. S4D and E). Taken together, our results suggest that the H3K36me3 mark in the nucleosomes with a linker DNA contain the biochemical and molecular determinants for efficient HIV-1 DNA integration.

During HIV-1 infection, a number of host factors are utilized to complete the early and late stages of the viral replication cycle (157). HIV-1 DNA integration into the host chromosomes by the PIC is dependent on host factors such as LEDGF/p75, INI1, CPSF6, and others (111–113, 158). The most studied PIC-associated host factor is LEDGF/p75, which engages with HIV-1 IN via the IN binding domain (IBD) (79, 116, 118). Concomitantly, LEDGF/p75 interacts with the H3K36me2/3 marked chromatin, and other methylated histones, through the PWWP domain and AT-hook motifs (122, 123, 159). It has been reported that LEDGF/p75 facilitates HIV-1 DNA integration by tethering the PIC to actively transcribing genes (64, 77, 79, 83, 118, 160). Therefore, we hypothesized that the combination of LEDGF/p75 and the H3K36me3 would yield an additive effect on HIV-1 DNA integration. As expected, we observed a significant increase in HIV-1 DNA integration into both the nucleosome and the analogous naked DNA with the INS in the presence of LEDGF/p75 (Fig. 5A and B). Surprisingly, LEDGF/p75 significantly reduced PIC-mediated integration into the nucleosomes and had a minimal effect on integration into the naked DNA (Fig. 5C and D). Intriguingly, Lapaillerie et al. recently reported that LEDGF/p75 preincubation with a nucleosome target DNA resulted in reduced viral DNA integration with preassembled HIV-1 INS (66). A lack of such block to the INS-associated viral DNA points to the involvement of additional factors and/or mechanisms specific to the PIC. In addition, IN activity was disrupted when the LEDGF/p75 amounts exceeded a >2-fold amount of IN (119). Since, LEDGF/p75 is present in the extracted PICs (Fig. 5E) and the addition of exogenous LEDGF/p75 blocked access to the nucleosome-bound DNA (Fig. 5G and H), we predict that excessive LEDGF/p75 can sterically hinder access of the PIC-associated viral DNA to the nucleosome-bound target DNA. We acknowledge that the stoichiometry of PIC-associated IN and LEDGE/p75 in our PIC extracts is unknown. Nevertheless, excessive LEDGF/p75, overexpression of the LEDGF/p75-IBD domain, and certain LEDGF-derived peptides are reported to inhibit HIV-1 integration (78, 79, 119, 161–163). Notably, the LEDGF/p75 inhibition of PIC-mediated integration was relieved with the H3K36me3-modified nucleosomes and allowed recovery of the PIC-mediated integration (Fig. 6A to C). The presence of linker DNA also relieved the LEDGF/p75 mediated reduction of PIC-mediated integration (Fig. 6D). Collectively, these data implicate that structural and/or conformational features of nucleosomes rendered by linker DNA and the H3K36me3 modification are essential for LEDGF/p75 to promote of PIC-mediated viral DNA integration.

Our biochemical data show that the H3K36me3-modified nucleosomes containing linker DNA is an ideal substrate for PIC-mediated integration. However, our in vitro integration assay is not designed to identify the targets of integration into specific regions of the nucleosome. The nucleosome core particle-bound DNA is highly contorted and bent into ~1.75 left-handed superhelical turns of ~80 bp/turn (50, 51). This bending is a consequence of the minor and major groove structures of the DNA where the minor grooves are preferentially oriented toward the histone octamer surface (50, 95, 164, 165). There is evidence that the outward-facing DNA integration occurs at the sites of the major grooves of the target DNA within the nucleosome. Even though, retroviral INs lack target DNA sequence specificity for integration (166, 167), studies of mononucleosome particles (61) or minichromosomes (59, 60) have shown that the DNA wrapped around the nucleosome is preferentially targeted compared to nucleosome-free DNA. Therefore, to better understand the consequence of the H3K36me3-modified nucleosomes on viral DNA integration targeting, we carried out deep sequencing of the viral DNA integrants from PIC assays with the linker naked DNA, linker nucleosome, and the linker H3K36me3-modified nucleosome. The PIC-mediated viral DNA integration that was observed within the linker-DNA preferably occurred throughout the length of the DNA sequence, and primarily within the linker DNA sequence-positions from bp 1 to 50 and from bp 197 to 247 (Fig. 7A; see also Fig. S7 and S8 in the supplemental material). Similarly, integration within the linker unmodified nucleosomes occurred most frequently in the linker DNA and a slight uptick in the integration sites throughout the nucleosome core positioning sequence, bp 50 to 197 (Fig. 7B; see also Fig. S7 and S9). Remarkably, the integration into the nucleosome core DNA increased within the linker H3K36me3-modified nucleosomes. Both the integration count and the frequency occurred overwhelmingly in the nucleosome core sequence of the H3K36me3-modified nucleosomes with linker DNA (Fig. 7C; see also Fig. S7 and S10). It should be noted that these integration site analyses were from sequencing reads of <500 due to the technical challenges of shorter DNA substrates. Therefore, we are cautious about the statistical and physiological significance of these observations. Nevertheless, qualitative analysis of the integration sites within the linker H3K36me3 nucleosomes indicates that the integrants abutted within the superhelical locations (SHL) −1, −7, +7, and +1, locations that correspond to the location where the H3-tail protrudes through the nucleosomal DNA (55, 105, 122). This striking observation suggests that the H3K36me3 mark can perform a functional role in directing the HIV-1 PIC-associated DNA into specific regions of the nucleosomal DNA.

Our results provided biochemical evidence that the nucleosome structure characteristic of open chromatin enhances HIV-1 DNA integration. Open chromatin represents a minority of the human genomic DNA, whereas closed chromatin or heterochromatin represents up to 80% of the genomic DNA (150, 168). However, it is unclear why HIV-1 integration is disfavored in these vast DNA regions of the human chromosomes (33, 40, 42, 44, 103). To interrogate the role of closed chromatin on HIV-1 integration, we probed the effects of the linker histone H1° due to its relatively high abundance among H1 variants (169) and well-characterized ability to condense chromatin fibers and form rigid, stable chromatosome structures (52, 134). As expected, H1° addition protected isolated chromatin from the partial micrococcal nuclease digestion (see Fig. S13A to D) and, at nonsaturating amounts, inhibited HIV-1 INS-mediated integration (Fig. 8A to C). This is consistent with the published studies with HIV-1 IN and H1-mediated condensation of recombinant nucleosome arrays (38, 133, 170). Surprisingly, nonsaturating amounts of H1° failed to inhibit PIC-mediated integration into the linker substrates (Fig. 8D to F; see also Fig. S11A to C). However, at stoichiometric saturating levels relative to the DNA substrate, PIC-mediated integration was significantly reduced with all the linker substrates (Fig. 8G to I; see also Fig. S11D to F). Interestingly, H1 similarly reduced PIC-mediated integration into both genomic DNA and chromatin (Fig. 8J to K; see also Fig. S13E and F). These observations suggest that mechanisms other than nucleosome structure could be involved in PIC-mediated integration inhibition. While H1 specifically binds nucleosomes at the dyad while interacting with linker DNAs, H1 has also the ability to bind to naked DNA substrates (171–173). In addition, our data indicated that preincubation with the target DNA is requisite for the H1-mediated inhibition of PIC-mediated integration (see Fig. S13G and H). Finally, in line with our in vitro data, proviral DNA integration was reduced by almost 50% in H1° O/E cells (Fig. 9B), suggesting that the histone H1 can negatively regulate HIV-1 DNA integration through chromatin compaction. Studies interrogating the consequence of excess H1 and salt-mediated compaction on HIV-1 integration, as well as the subsequent integration site selection, will further enhance our knowledge of the mechanisms of reduced retroviral DNA integration into compacted chromatin.

Collectively, our study provides biochemical evidence and mechanistic insights into HIV-1 integration preference into open chromatin. Particularly, these results reveal a direct role of the H3K36me3 epigenetic mark in HIV-1 integration preference and identify an optimal substrate for HIV-1 PIC-mediated viral DNA integration. Finally, our study highlights the utility of PIC studies, since viral DNA integration by the PIC utilizes distinct mechanism compared to the biochemically assembled INS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

HEK293T and SupT1 cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The TZM-bl reporter cell line (catalog no. ARP-8129) was obtained through the NIH HIV Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH. TZM-bl cells were contributed by John C. Kappes, Xiaoyun Wu, and Tranzyme, Inc. (174). HEK293T and TZM-bl cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM glutamine, 1,000 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin. SupT1 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 1,000 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin. All cells were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Virus stocks and other reagents.

High titer virus stocks were generated by transient transfection of HEK293T cells with the HIV-1 plasmid construct pNL4-3 (NIH AIDS Reagents) with polyethyleneimine (PEI) as per our published protocol (87). Briefly, 3 × 106 cells were seeded per 10-cm culture dish and cultured overnight. The following day, cells in each dish were transfected using PEI and 10 to 15 μg of pNL4-3 DNA. At 16 h posttransfection, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (1× phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) and replenished with 6 mL of DMEM. After 36 h, the virus-containing culture supernatant of transfected cells was harvested, cleared of debris by low-speed centrifugation, filtered through 0.45-μm filters, and treated with DNase I (Calbiochem; 20 μg/mL of supernatant) in the presence of 10 mM magnesium chloride (MgCl2) for 1 h at 37°C. The virus infectivity was determined by using TZM-bl indicator cells, as previously described (175). Raltegravir (RAL) (Isentress, MK-0518), ARP-11680, was obtained from the NIH HIV reagent program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH, and was contributed by Merck & Company, Inc.

Chromatin isolation.

The chromatin isolation protocol is adapted from a published protocol (92). HEK293T cells were cultured to near confluence, harvested, and then washed once with ice cold 1× PBS. The cells were manually lysed on ice with a Dounce homogenizer (Wheaton) in native lysis buffer (NLB; 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 250 mM sucrose, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.5 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]) for 20 to 30 strokes. The lysate was washed and homogenized with NLB twice by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. After manual lysis with NLB, the pellet was washed with modified buffer B (MBB; 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 0.2 M EGTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF, protease inhibitor cocktail [Promega, Madison, WI]). The resulting pellet was resuspended in 2 volumes of MBB, in reference to the pellet volume, and then an equivalent volume of MBB–0.6 M KCl–10% glycerol was added in a dropwise manner. The lysate was incubated at 4°C for 10 min with consistent rocking. After incubation, the nuclear fraction was pelleted at a precooled (4°C) centrifuge at maximum speed. The pelleted nuclear fraction was resuspended in 20 times volume of medium salt buffer (MSB; 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 0.4 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol [vol/vol], 0.5 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF) and manually homogenized. The nuclear pellet was centrifuged for 10 min at 11,000 × g at 4°C and then resuspended in 4 pellet volumes of high salt buffer (HSB; 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 0.65 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.34 M sucrose, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF). Oligonucleosomes were released from the nuclear debris by manual homogenization on ice and fully separated from the debris by maximum-speed centrifugation at 4°C to collect the chromatin-containing supernatant. The chromatin was dialyzed for 16 h against low-salt buffer (LSB; 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 0.1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF). The dialyzed chromatin was tested for nucleosome protection by using partial micrococcal nuclease digestion, and, subsequently the presence of histone proteins was tested via Coomassie staining and Western blotting.

Immunoblotting.

To detect proteins by immunoblot, samples were prepared in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Inc., Dallas, TX) or NLB buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail and 10 μg/μL PMSF (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) according to the standardized protocol. Protein concentrations were determined using BCA (bicinchoninic acid) protein assay reagent (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer’s specifications. Equivalent amounts of protein from cellular lysates or fractions were electrophoresed on precast gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) or in-house prepared 15% polyacrylamide gels and electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using Trans-Blot SD semidry transfer cells (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The membranes were incubated in blocking buffer (5% [wt/vol] nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20 [TBST]; pH 8.0). After blocking, the membranes were then probed with the following indicated antibodies diluted in blocking buffer: H2A (ab18255), H2B (ab1790), H3 (ab1791), H4 (ab7311), and H1° (ab218417) (all from Abcam, Boston, MA); H3K36me3 (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA; ab_2615073); LEDGF/P75 (Bethyl Laboratories, Inc., Montgomery, TX; A300-848A); p53 (Cell Signaling Technology, 2527S); and GAPDH (60004-1; Proteintech, Rosemont, IL) and subsequently with secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (anti-rabbit 1:10,000 [vol/vol]; anti-mouse 1:10,000 [vol/vol]). The membranes were washed with 1× TBST buffer at least three times for 15 min for each wash, and immunocomplexes were detected by a clarity enhanced chemiluminescence method (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Isolation of PICs.

HIV-1 PICs were isolated from acutely HIV-1-infected T cells, as described in our published methods (87–91). Briefly, 8 × 107 of SupT1 cells were spinoculated (480 × g) with DNase I-treated wild-type virions for 2 h at 25°C and then cultured for 5 h at 37°C. The infected cells were then harvested by centrifugation (300 × g) for 10 min at room temperature. The cell pellet was washed twice with 2 mL of buffer K−/− (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 150 mM potassium chloride [KCl], 5 mM MgCl2). Subsequently, the cell pellet was gently resuspended in 2 mL of ice-cold buffer K+/+ (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 150 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 20 mg/mL aprotinin, 0.025% [wt/vol] digitonin). The cell suspension was transferred to a chilled 2-mL microcentrifuge tube and incubated on a rocking platform (60 to 80 rocking motions/min) for 10 min at room temperature. The cell lysate was centrifuged (1,500 × g) for 4 min at 4°C to separate the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions. The supernatant (cytoplasmic fraction) was transferred to a fresh 2-mL microcentrifuge tube and centrifuged again (16,000 × g) for 1 min at 4°C to clear residual nuclear debris. The resulting cytoplasmic fraction was treated with RNase A (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA) at a final concentration of 20 mg/mL and then incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Finally, 60% (wt/vol) sucrose was added to a final concentration of 7%, and the contents were thoroughly mixed. Aliquots of the cytoplasmic fraction were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for long-term storage. The cytoplasmic fraction aliquots were used as the source of HIV-1 PICs in assays.

Assay for measuring PIC-mediated viral DNA integration.

In vitro integration assays were performed using a modified version of a protocol from our laboratory (87, 89–91). The in vitro integration reaction was carried out by mixing 50 μL of PIC with 300 ng of the indicated target DNA and then allowing the mixture to incubate at 37°C for 45 min. The integration reaction was stopped by adding SDS, EDTA, and proteinase K to final concentrations of 0.5%, 8 mM, and 0.5 mg/mL, respectively, followed by overnight incubation at 55°C. The deproteinized reaction was brought to 200 μL, mixed with an equal volume of phenol (pH 8.0), thoroughly mixed by vortexing, and then centrifuged (17,000 × g) for 2 min at room temperature. The aqueous phase is extracted once with an equal volume of phenol-chloroform (1:1) mixture, followed by an equal volume of chloroform. The DNA was precipitated by adding 2.5 volumes of 100% ice-cold ethanol in the presence of sodium acetate (0.3 M, final concentration) and the coprecipitate glycogen (25 to 100 μg, final concentration), followed by a minimum incubation for 2 h at −80°C. The sample was centrifuged at maximum speed for 30 min at 4°C, and the resultant DNA pellet was washed once with 70% ethanol using maximum-speed centrifugation for 15 min at 4°C. The precipitated DNA was air-dried at room temperature, resuspended in 50 μL of nuclease-free water, and used as the template DNA for the nested qPCR to measure PIC-mediated viral DNA integration.