Abstract

The Medicare annual wellness visit—a preventive care visit free to Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Part B—requires detection of cognitive impairment. We surveyed an internet panel of adults ages sixty-five and older who were enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare or Medicare Advantage to measure the use of that benefit and the receipt of structured cognitive assessment by 2019. Overall, approximately one-half of beneficiaries surveyed reported having an annual wellness visit, and fewer than one-third reported having a structured cognitive assessment. Compared with fee-for-service enrollees, Medicare Advantage enrollees were nearly 20 percentage points more likely to report that they had an annual wellness visit and 8.6 percentage points more likely to report that it included a structured cognitive assessment. The difference suggests that the rate of structured cognitive assessment in fee-for-service Medicare might be increased by offering financial and other incentives for take-up that are similar to those in Medicare Advantage.

Of the fifty-five million Americans ages sixty-five and older, an estimated 6.9 million (12.5 percent) were living with dementia in 2018.1 The cost of medical and long-term care is high, at about $290 billion in 2019.2 By 2050, 13.8 million Americans are projected to be living with dementia,3 with costs rising to more than $1.5 trillion just for Alzheimer disease, the most common form of dementia.1

Increases in the number of people living with dementia and in the financial and nonfinancial costs of care are major policy concerns. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) promotes early detection of dementia through the Medicare annual wellness visit, a comprehensive primary care visit that requires, among other things, that providers detect cognitive impairment. Our study examines patient-reported use of the annual wellness visit benefit and structured assessment of cognitive impairment at these or other visits among beneficiaries in fee-for-service Medicare versus Medicare Advantage (MA).

Despite the current lack of therapies to prevent or treat dementia, early detection may facilitate the identification and treatment of reversible causes of cognitive impairment, management of symptoms to maintain functioning, improvement in quality of life, and delay of institutionalization.4–6 Early detection may also enable patients to communicate living and end-of-life desires before impairment is severe and allow families to plan for a patient’s safety and protection.2–9

Dementia is often diagnosed late or goes undiagnosed, particularly among Black and Hispanic populations, who are at higher risk for dementia than non-Hispanic Whites.10–12 The annual wellness visit has the potential to increase dementia detection rates, as mild cognitive impairment is often an early indication of dementia, and dementia is typically diagnosed in the primary care setting.13

The annual wellness visit specifically requires “detection of any cognitive impairment,” defined as “assessment of an individual’s cognitive function by direct observation, with due consideration of information obtained by way of patient report, concerns raised by family members, friends, caretakers or others.”14 Medicare offers limited policy guidance on how to perform an assessment, beyond specifying the use of a “validated structured assessment tool,” if appropriate.15 Evidence of whether cognitive assessment takes place at the annual wellness visit is limited, in part because providers bill Medicare for this visit but not for the specific services performed at the visit. Even less well understood is how annual wellness visit use and cognitive assessments vary by Medicare coverage type—that is, in fee-for-service Medicare or MA plans.

We fielded a brief survey among people ages sixty-five and older who are part of an ongoing internet panel to capture their self-reported Medicare coverage type, use of the annual wellness visit benefit, and receipt of structured cognitive assessments. The key research questions were, first, what are the rates of annual wellness visit use and of structured cognitive assessment at the annual wellness visit or at any health care visit; and, second, how do these rates vary between enrollees in Medicare Advantage and enrollees in fee-for-service Medicare?

Background

In January 2011, as a result of the ACA, Medicare began reimbursing for its annual wellness visit to promote detection and prevention of many age-related health conditions, including cognitive decline.1 Because the annual wellness visit is available without cost sharing to Part B enrollees, take-up of the visit has grown.6–18 According to a 20 percent sample of fee-for-service Medicare claims, 7.5 percent of beneficiaries had an annual wellness visit in 2011, but 15.6 percent had one in 2014.16 By 2015 nearly 19 percent of fee-for-service beneficiaries received an annual wellness visit.18 In one large MA plan, take-up increased from 6.2 percent in 2011 to 25.2 percent in 2015.19 However, we lack population-based estimates of annual wellness visit take-up among the 36 percent of beneficiaries who are in MA plans; estimates from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) assume that the fee-for-service rate applies to beneficiaries in MA plans.20,21

A few studies find that general preventive services increase with the annual wellness visit,22–24 whereas others find little change in preventive care use25,26 or follow-up care, including neurology visits.27 Anecdotal evidence suggests that many providers do not take a systematic approach to detecting cognitive impairment.28 A potential hurdle may be the lack of specific policy guidance on how to conduct an assessment.15

Similar to other preventive care visits, use of the annual wellness visit may differ across fee-for-service and MA coverage.21 Fragmented care in fee-for-service Medicare may hamper dissemination of new benefits such as the annual wellness visit. In contrast, the star rating system for MA plans, a key provision of the ACA that measures plan performance in several domains covered by the annual wellness visit, may encourage these visits. Moreover, CMS’s risk adjustment to modify capitated payments to MA plans based on an enrollee’s illness burden provides incentives to monitor the health of members through visits such as the annual wellness visit.

Study Data And Methods

DATA

We designed and fielded a survey to people ages sixty-five and older who are part of the Understanding America Study. This nationally representative panel of about 8,000 people ages eighteen and older residing in the United States is maintained by the Center for Economic and Social Research at the University of Southern California. Understanding America Study surveys are conducted online, using a computer, tablet, or smartphone. People without online access are provided with a tablet and an internet subscription.29 The Understanding America Study has been used to study health insurance uptake30 and vaccinations.31

We created a thirteen-question survey to address our research questions. The survey included a validated measure of cognitive function from the Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System;32 the Patient Health Questionnaire 2 (PHQ-2) measure of depressed mood; and two widely used, five-option measures: self-rated health and self-rated mental health. We also designed questions to capture annual wellness visit experiences and views of cognitive testing (for example, level of agreement with the statement, “Cognitive assessments are a good addition to medical services”). Demographic and socioeconomic information for panel members was collected previously by the Understanding America Study. The University of Southern California’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved our data collection as an amendment to the IRB-approved study UP-14-00148. Respondents received $4 in compensation for survey completion based on a median response time of six minutes. The full text of our survey and our data are on the Understanding America Study website (search for “UAS 179”).33

On April 18, 2019, we invited all 1,428 people ages sixty-five and older in the Understanding America Study to complete our survey. We closed the survey on May 6, 2019, after receiving 1,142 complete responses (80 percent response rate). The final analytic sample included 966 people: the 993 people who stated they had Medicare coverage minus 27 people who had survey sampling weights of zero as a result of Understanding America Study recruitment sampling limitations.

We compared our final Understanding America Study analytic sample with data for people ages sixty-five and older with Medicare coverage in the 2018 Annual Social and Economic Supplement of the Current Population Survey (CPS), a nationally representative survey on labor-force participation, income, and health insurance conducted by the Census Bureau (online appendix exhibit 1).34 Compared with the CPS sample, Understanding America Study respondents were nearly half as likely to be non-White (12 percent versus 23 percent) and more likely to be born in the US (93 percent versus 88 percent) or be widowed (20 percent versus 13 percent) than Current Population Survey respondents (appendix exhibit 1).33 The distribution of age, education, sex, Hispanic ethnicity, and self-rated health was similar in the two samples. Rates of MA enrollment (37.7 percent) in the Understanding America Study sample were similar to the 2018 national average (36 percent).20

To benchmark annual wellness visit rates, we analyzed fee-for-service Medicare claims. We used annual Part B claims data from the period 2011–18 for about twenty-one million beneficiaries per year who were age sixty-five or older and had been continuously enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare for three years (for example, N = 21,681,174 beneficiaries in 2018). Codes G0438 and G0439 identified annual wellness visits.

KEY SURVEY MEASURES

ANNUAL WELLNESS VISITS:

The survey described the nature of and differences between “Welcome to Medicare” visits and “Annual Wellness Visits.” The survey then asked respondents whether they had ever had a “Welcome to Medicare” visit—a one-time initial Medicare visit available to all beneficiaries in the first twelve months of Part B enrollment that is distinct from an annual wellness visit. A separate question asked respondents whether they had ever had an annual wellness visit. Our outcome of interest was receipt of at least one annual wellness visit between 2011 and April 2019, when we fielded our survey.

COGNITIVE ASSESSMENTS:

The survey described cognitive assessments using examples of word recall and backward counting tests commonly used in structured cognitive screenings. It then explained that the annual wellness visit should include, among other things, a cognitive assessment. Respondents were asked whether they had received a cognitive assessment at an annual wellness visit and, separately, whether they had received a cognitive assessment during any health care visit. The outcomes of interest were cognitive assessment at an annual wellness visit and cognitive assessment in any care setting.

COVERAGE STATUS:

Respondents were asked whether they had Medicare coverage. Those who answered yes were asked whether they were enrolled in traditional (fee-for-service) Medicare or a Medicare Advantage plan.

ANALYSIS

We first used fee-for-service Medicare Part B claims to quantify the percentage of beneficiaries who had an annual wellness visit in each year from 2011 to 2018. For comparison with our Understanding America Study survey, we also measured the share of beneficiaries in 2018 who ever had an annual wellness visit.

With the Understanding America Study survey data, we quantified the percentage of respondents who had ever had an annual wellness visit; a cognitive assessment at an annual wellness visit; and, because people might not recall the setting of an assessment, any cognitive assessment. We compared rates for beneficiaries in fee-for-service Medicare versus Medicare Advantage.

We estimated linear probability models to quantify the association between Medicare coverage type and annual wellness visit and cognitive assessment, adjusting for demographic, socioeconomic, and health characteristics. Our models included indicators for age groups (ages 65–69, 70–79, and 80+), education categories (high school or less, some college, or college and above), non-White race, Hispanic/Latino ethnicity, male, native US born, marital status, income categories (below $25,000, $25,000–$49,999, $50,000–$74,999, and $75,000+), and two separate self-reported measures of physical and mental health on five-point scales. For summary statistics overall and by Medicare coverage type, see appendix exhibit 2.34 We included indicators for state of residence; thus, our estimates compared self-reported annual wellness visit use and cognitive assessment receipt for people in fee-for-service versus MA plans who lived in the same state.

We performed several sensitivity and robustness checks. Because enrollment in Medicare Advantage requires an active choice, we assumed that the 10 percent of beneficiaries who did not know their coverage type had not chosen Medicare Advantage and, therefore, had fee-for-service Medicare. We analyzed the robustness of the results to this assumption by excluding the people uncertain as to their coverage type. Second, we estimated probit models to test the robustness of our results to model choice. Finally, we tested the sensitivity of our results to dropping rather than coding as 0 those answering “Do not know” about receipt of an annual wellness visit, cognitive assessment at an annual wellness visit, or cognitive assessment at any visit.

LIMITATIONS

This study had several limitations. First, Understanding America Study panel participants must answer survey questions online. As a consequence, the sample might not capture people with severe cognitive impairment. Their exclusion is unlikely to substantively change the finding of low assessment rates at the annual wellness visit, given that about 10 percent of the population ages sixty-five and older is living with dementia.35

Second, survey responses are subject to recall errors, which may be more severe among those with cognitive impairment. Also, survey measures may be sensitive to question wording and ordering. Our survey captured patients’ reports of receiving structured cognitive assessment; however, the requirement to detect cognitive impairment may also be fulfilled using direct observation or by having a discussion with the patient, a family member, or a caregiver. By focusing on structured cognitive assessments, the survey may underestimate actual detection rates. Furthermore, differences by coverage type in either the share of respondents with cognitive impairment or cognitive assessment methods could affect the interpretation of our data. These limitations highlight the importance of future validation work.

Third, although weighted to be nationally representative, the Understanding America Study has very few non-White and low-education respondents. Because Blacks and Hispanics compared with Whites and people with low relative to high education are at higher risk for dementia, additional research using larger, more diverse samples are needed to better understand cognitive assessment in high-risk groups.36

Study Results

ANNUAL WELLNESS VISITS

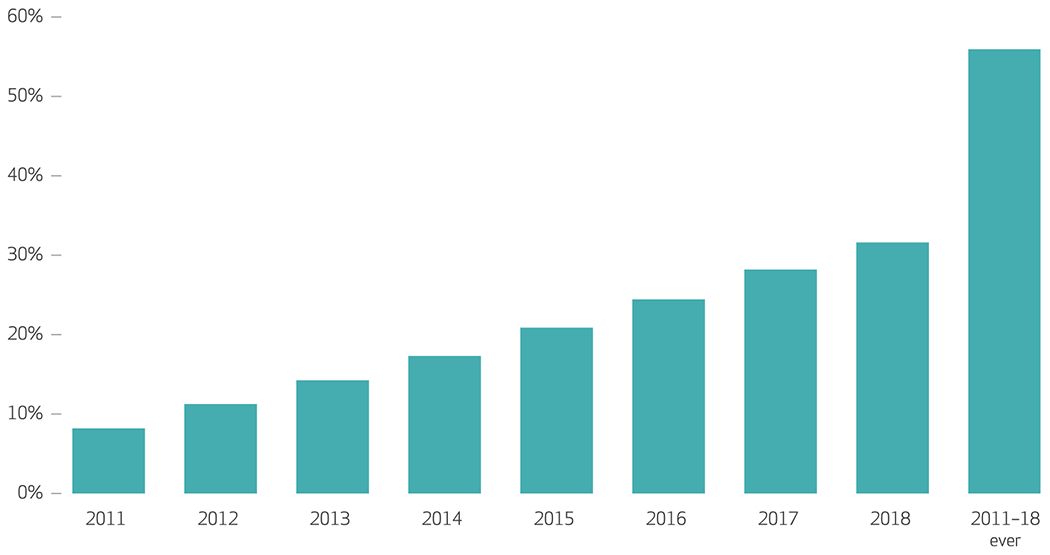

Exhibit 1 shows the percentage of fee-for-service beneficiaries who had an annual wellness visit in each year from 2011 to 2018, based on Medicare claims. In 2011 approximately 8 percent of beneficiaries had an annual wellness visit. Visit rates increased by about 3 percentage points each year to 31.6 percent in 2018. By 2018 about 56 percent of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries had had at least one annual wellness visit since 2011. Our 2016 rate is about 4.5 percentage points higher than the published rate for that year,21 possibly because of our restriction to continuously enrolled beneficiaries.

EXHIBIT 1. Annual wellness visit prevalence among fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries, 2011-18.

source Claims data for all beneficiaries in fee-for-service Medicare in each year, 2011–18. note “2011–18 ever” represents beneficiaries in 2018 who were continuously enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare for three years (2016–18) and who had had at least one annual wellness visit since 2011.

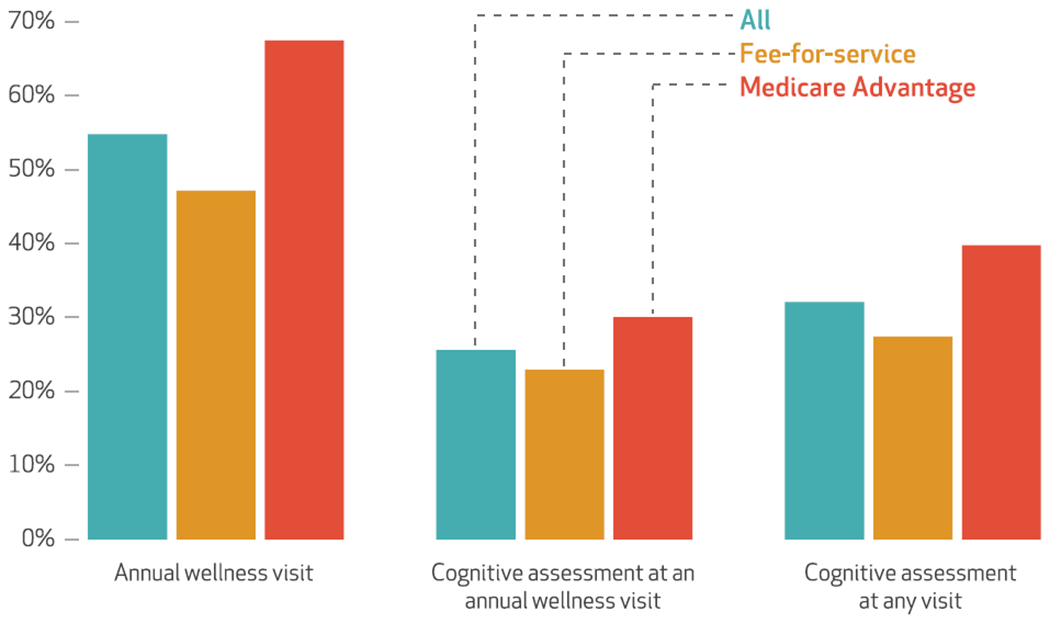

Exhibit 2 shows our survey measures of annual wellness visit use as of mid-2019. Just over half (55 percent) of our sample reported ever having an annual wellness visit. Visit rates varied markedly by Medicare coverage type, with 47 percent of fee-for-service beneficiaries and 67 percent of MA enrollees reporting an annual wellness visit. Although the fee-for-service rate (47 percent) was lower than the 56 percent rate in the fee-for-service claims (see exhibit 1), this may be because the Understanding America Study captured current rather than continuous coverage.

EXHIBIT 2. Percent of Medicare beneficiaries receiving annual wellness visits and cognitive assessment, overall and by Medicare plan type, 2019.

source Understanding America Study survey of seniors ages sixty-five and older. note Measures capture ever having had an annual wellness visit or cognitive assessment.

COGNITIVE ASSESSMENTS

Beneficiaries in MA plans were more likely to report receiving a structured cognitive assessment at an annual wellness visit than were fee-for-service beneficiaries (30 percent versus 23 percent; exhibit 2). The gap between fee-for-service and Medicare Advantage was larger for structured cognitive assessment at any type of visit, with 27 percent of fee-for-service beneficiaries and 40 percent of those in MA plans reporting a structured cognitive assessment. Nearly two-thirds of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that “cognitive assessments are a good addition to medical services,” with no difference among fee-for-service or Medicare Advantage enrollees (see appendix exhibit 2).34

ADJUSTING FOR BENEFICIARY DIFFERENCES

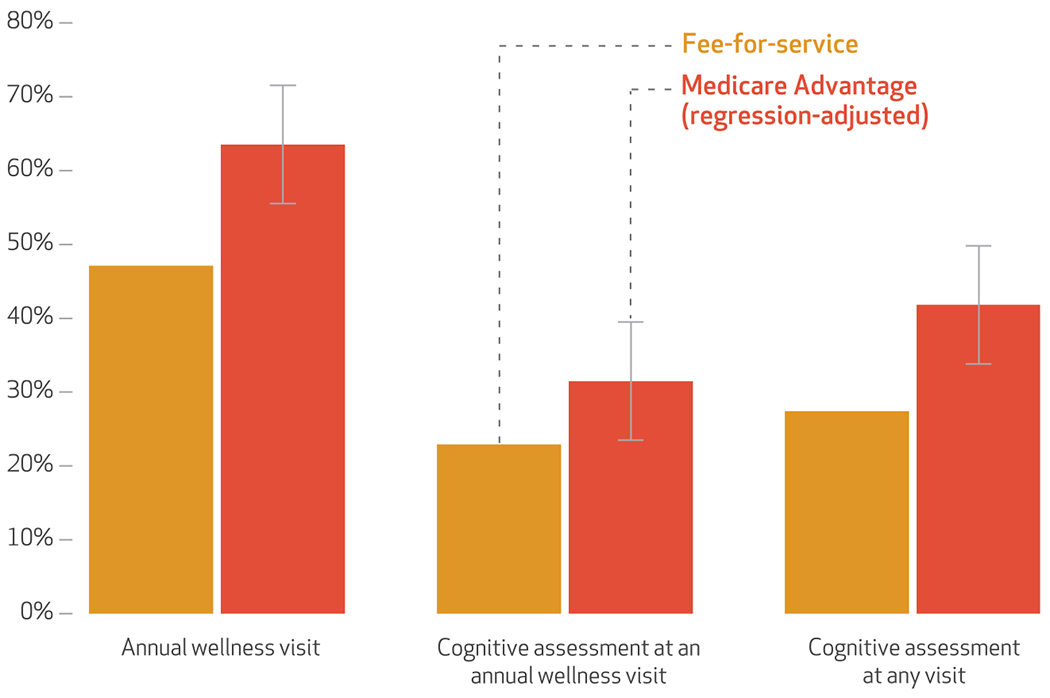

We also assessed whether observable differences in fee-for-service beneficiaries versus Medicare Advantage enrollees explained these differences. Exhibit 3 shows that the difference between annual wellness visit use by coverage type narrowed only slightly when we controlled for respondents’ characteristics. Respondents in Medicare Advantage plans were still more than 16 percentage points more likely to have had an annual wellness visit than otherwise similar enrollees in fee-for-service Medicare. Differences in cognitive assessments at the annual wellness visit narrowed as well but remained substantial. Those in MA plans were about 8.6 percentage points more likely to report a cognitive assessment at an annual wellness visit.

EXHIBIT 3. Adjusted difference In annual wellness visit or cognitive assessment likelihood among Medicare beneficiaries, 2019.

source Understanding America Study survey of seniors ages sixty-five and older. notes Measures capture ever having had an annual wellness visit or cognitive assessment. Error bars capture the 95% confidence intervals of the regression-adjusted rates for respondents with Medicare Advantage plans.

The difference in receipt of cognitive assessments at the annual wellness visit is explained entirely by the difference in annual wellness visit rates rather than in the propensity to screen at the visit. That is, controlling for annual wellness visit use, those in MA plans and in fee-for-service Medicare were equally likely to report a cognitive assessment at an annual wellness visit (see appendix exhibit 3).34 Because people might not remember where they had a cognitive assessment, we also analyzed whether respondents had a cognitive assessment at any health care visit. Those in MA plans were about 14 percentage points more likely to report receiving a cognitive assessment. This difference shrank by more than a third (to about 9 percentage points) but remained statistically significant after annual wellness visit use was controlled for (see appendix exhibit 3).34

The findings in exhibit 3 were stable across a range of robustness checks. First, estimates from models that included just state fixed effects and demographic controls or state fixed effects, demographic controls, and indicators for marital status and income categories were similar to the main model results (see appendix exhibit 4).34 Second, estimates were robust to our definition of MA plan status: Results that eliminated the small sample of people who did not know whether they were in an MA plan or fee-for-service Medicare were very similar (see appendix exhibit 5).34 Likewise, our results were not sensitive to model choice: Estimates from probit regression models, with marginal effects calculated at the means of the covariates, were qualitatively similar and in all cases somewhat larger in magnitude than our linear probability model results (see appendix exhibit 6).34

Finally, our results were not sensitive to eliminating people who were uncertain about having had an annual wellness visit or a structured cognitive assessment (see appendix exhibit 6).34 In short, our estimates all suggest that Medicare Advantage enrollees were more likely to have had an annual wellness visit and a structured cognitive assessment at the annual wellness visit than otherwise similar people living in the same state but enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare.

Discussion

Surveying a unique, established sample of adults ages sixty-five and older who have Medicare Advantage or fee-for-service Medicare coverage, we found that use of Medicare’s annual wellness visit benefit was systematically higher for people in MA plans. By collecting new data on receipt of a particular component of the annual wellness visit—the cognitive assessment—we found that only about a quarter of total respondents reported receiving one at an annual wellness visit, even though, under the ACA, cognitive assessment is a required element of that visit. Because “direct observation” can technically be used to detect cognitive decline at the annual wellness visit, the actual rate of assessment may be higher than that found here. However, as shown in other settings, assessments based on direct observation are subject to overconfidence, confirmation, and other psychological biases.37,38 Although the performance of direct observation compared with structured assessment for detecting cognitive impairment has not yet been analyzed, psychological biases decrease confidence in the validity of observation alone.

Because administrative claims data do not capture different components of the annual wellness visit, our data provide new insight into the black box of services received at that visit. Our data also captured how cognitive assessment varied in different Medicare coverage environments. People in MA plans were 8.6 percentage points more likely than those in fee-for-service Medicare to report a structured cognitive assessment at an annual wellness visit, primarily because of their higher likelihood of receiving such a visit. Medicare Advantage beneficiaries were also more likely to have a cognitive screen at any health care visit. Research is needed to validate these differences and understand what accounts for them.

Our findings are consistent with work showing higher preventive services use among MA plan beneficiaries than fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries in the same large, multicity health system and among enrollees in MA plans nationally. 39,40 Moreover, they are consistent with trade materials suggesting an advantage of annual wellness visits for MA plans, supporting a more detailed accounting of risk-adjustment factors.41 The differences may also reflect the greater focus on care coordination and patient outcomes inherent in MA plan design and incentivized by the Medicare Advantage star rating system.

Policy Implications

Take-up of Medicare’s annual wellness visit has grown since 2011. By 2019 most beneficiaries reported having had one. Although annual wellness visits have required detection of cognitive impairment since the visit’s introduction, our survey found that structured assessment of cognitive functioning is not widely performed. Our finding is consistent with, but lower than, primary care physician self-reports indicating that they perform brief cognitive assessments in about half of their patients ages sixty-five and older.2

Recently, the US Preventive Services Task Force updated its 2014 recommendation on screening for cognitive impairment, again concluding that as a result of the paucity of empirical evidence, it cannot appropriately weigh the benefits and harms of cognitive screening in community-dwelling older adults.42 Despite unanswered questions about the benefits of screening for patients and caregivers and the accuracy of tools, our survey data indicate that structured cognitive assessment is valued by older people. Combined with randomized controlled trial evidence that screening in the primary care setting does not increase depressive symptoms or anxiety,43 these data provide further evidence to support the use of structured cognitive assessments at the annual wellness visit.

Medicare payment policy for the routine assessment of cognitive impairment in the primary care setting is a potentially potent tool to improve early detection of dementia. If borne out in administrative data, our results indicate that MA plans can better deploy annual wellness visits in general, and structured cognitive assessment in particular. Thus, a direct service-related payment for a set of bundled services, as in fee-for-service Medicare, might not be the most potent tool to increase cognitive assessments. Rather, a combination of financial incentives and a system of communication among payers, providers, and patients may be necessary to increase annual wellness visit take-up and the receipt of structured cognitive assessments.

The higher rates of structured cognitive assessment seen in Medicare Advantage compared with in fee-for-service Medicare suggest that a higher rate of assessment is technically feasible. Recent policy changes may increase cognitive assessment rates and change the differential in Medicare Advantage versus fee-for-service Medicare. Specifically, CMS added new codes in 2017 to reimburse for cognitive assessment and care planning services for all Medicare beneficiaries and two new dementia condition categories to its risk-adjustment models for 2020 MA plan payment.44 As a result, MA plans now have more incentive to promote structured assessment for and documentation of dementia.45 ■

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Mireille Jacobson acknowledges support from the Navigage Foundation. Johanna Thunell and Julie Zissimopoulos acknowledge support from the National Institute on Aging, Grant Nos. R01AG055401, P30AG043073, and P30AG066589. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors thank the editor and three anonymous reviewers for excellent suggestions made to improve this article.

Contributor Information

Mireille Jacobson, Leonard Davis School of Gerontology and codirector of the Aging and Cognition Program at the Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics, University of Southern California, in Los Angeles, California.

Johanna Thunell, Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics, University of Southern California.

Julie Zissimopoulos, Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics and an associate professor at the Sol Price School of Public Policy, all at the University of Southern California.

NOTES

- 1.Zissimopoulos JM, Tysinger BC, Clair PA, Crimmins EM. The impact of changes in population health and mortality on future prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in the United States. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soci Sci. 2018;73(suppl_1):S38–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Special report on detection in the primary care setting. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(3):321–87. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zissimopoulos J, Crimmins E, Clair P. The value of delaying Alzheimer’s disease onset. Forum Health Econ Policy. 2014;18(1):25–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford A, Kunik ME, Schulz P, Williams SP, Singh H. Missed and delayed diagnosis of dementia in primary care: prevalence and contributing factors. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23(4):306–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubois B, Padovani A, Scheltens P, Rossi A, Dell’Agnello G. Timely diagnosis for Alzheimer’s disease: a literature review on benefits and challenges. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;49(3):617–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robinson L, Tang E, Taylor JP. Dementia: timely diagnosis and early intervention. BMJ. 2015;350:h3029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salib E, Thompson J. Use of anti-dementia drugs and delayed care home placement: an observational study. Psychiatrist. 2011;35(10):384–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raina P, Santaguida P, Ismaila A, Patterson C, Cowan D, Levine M, et al. Effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for treating dementia: evidence review for a clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(5):379–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Special report on the financial and personal benefits of early detection. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(3):367–429. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor DH Jr, Østbye T, Langa KM, Weir D, Plassman BL. The accuracy of Medicare claims as an epidemiological tool: the case of dementia revisited. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;17(4):807–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Y, Tysinger B, Crimmins E, Zissimopoulos JM. Analysis of dementia in the US population using Medicare claims: insights from linked survey and administrative claims data. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2019;5:197–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amjad H, Roth DL, Sheehan OC, Lyketsos CG, Wolff JL, Samus QM. Underdiagnosis of dementia: an observational study of patterns in diagnosis and awareness in US older adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(7):1131–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drabo EF, Barthold D, Joyce G, Ferido P, Chang Chui H, Zissimopoulos J. Longitudinal analysis of dementia diagnosis and specialty care among racially diverse Medicare beneficiaries. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(11):1402–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 42 CFR § 410.15: Annual wellness visits providing personalized prevention plan services: conditions for limitations on coverage [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): CMS; 2011. Nov 28 [cited 2020 Sep 1]. Available from: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2012-title42-vol2/pdf/CFR-2012-title42-vol2-sec410-15.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Medicare Learning Network. MLN booklet: annual wellness visit [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): CMS; 2018. Aug [cited 2020 Sep 1]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/AWV_Chart_ICN905706.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganguli I, Souza J, McWilliams JM, Mehrotra A. Trends in use of the US Medicare annual wellness visit, 2011–2014. JAMA. 2017;317(21):2233–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu J, Jensen GA, Nerenz D, Tarraf W. Medicare’s annual wellness visit in a large health care organization: who is using it? Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(7):567–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganguli I, Souza J, McWilliams JM, Mehrotra A. Practices caring for the underserved are less likely to adopt Medicare’s annual wellness visit. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(2):283–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carter EA, Lind K, Miller C. Annual wellness visits among Medicare Advantage enrollees: trends, differences by race and ethnicity, and association with preventive service use [Internet]. Washington (DC): AARP Policy Institute; 2019. May [cited 2020 Sep 1]. Available from: https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2019/05/annual-wellness-visits-among-medicare-advantage-enrollees.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare enrollment dashboard [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): CMS; 2020. Feb 13 [cited 2020 Sep 9]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/2018-mdcr-enroll-ab-1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Beneficiaries utilizing free preventive services by state, 2016 [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): CMS; 2017. Jan 12 [cited 2020 Sep 1]. Available from: https://downloads.cms.gov/files/Beneficiaries%20Utilizing%20Free%20Preventive%20Services%20by%20State%20YTD%202016.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chung S, Lesser LI, Lauderdale DS, Johns NE, Palaniappan LP, Luft HS. Medicare annual preventive care visits: use increased among fee-for-service patients, but many do not participate. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(1):11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galvin SL, Grandy R, Woodall T, Parlier AB, Thach S, Landis SE. Improved utilization of preventive services among patients following team-based annual wellness visits. N C Med J. 2017;78(5):287–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tao G Utilization pattern of other preventive services during the US Medicare annual wellness visit. Prev Med Rep. 2017;10:210–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jensen GA, Salloum RG, Hu J, Ferdows NB, Tarraf W. A slow start: use of preventive services among seniors following the Affordable Care Act’s enhancement of Medicare benefits in the U.S. Prev Med. 2015;76:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfoh E, Mojtabai R, Bailey J, Weiner JP, Dy SM. Impact of Medicare annual wellness visits on uptake of depression screening. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(11):1207–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ganguli I, Souza J, McWilliams JM, Mehrotra A. Association of Medicare’s annual wellness visit with cancer screening, referrals, utilization, and spending. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(11):1927–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ayati M Statement of Dr. Mehrdad Ayati, MD [Internet]. Washington (DC): US Senate Special Committee on Aging; 2018. Jan 24 [cited 2020 Sep 1]. Available from: https://www.aging.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/SCA_Ayati_01_24_18.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alattar L, Messel M, Rogofsky S. An introduction to the Understanding America Study internet panel. Soc Secur Bull. 2018;78(2):13–28. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Myerson R Health insurance literacy and health insurance choices: evidence from Affordable Care Act navigator programs [Internet]. Madison (WI): University of Wisconsin–Madison; 2018. Mar 18 [cited 2020 Sep 23]. [Unpublished manuscript]. Available from: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7a7b/6a7ae9a2029dbd4dbf5be9e221897a4ce1a7.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 31.Romley J, Goutam P, Sood N. National survey indicates that individual vaccination decisions respond positively to community vaccination rates. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0166858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Health Measures. PROMIS (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System) [Internet]. Evanston (IL): Northwestern University; 2020. [cited 2020 Sep 1]. Available from: https://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis [Google Scholar]

- 33.USC Dornsife Center for Economic and Social Research. Understanding America Study [Internet]. Los Angeles (CA): University of Southern California; 2017. [cited 2020 Sep 1]. Available from: https://uasdata.usc.edu/index.php [Google Scholar]

- 34.To access the appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alzheimer’s Association. 2018. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures [Internet]. Chicago (IL): 2018 [cited 2020 Sep 1]. Available from: https://www.alz.org/media/documents/facts-and-figures-2018-r.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen C, Zissimopoulos JM. Racial and ethnic differences in trends in dementia prevalence and risk factors in the United States. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2018;4:510–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kahneman D Thinking fast and slow. New York (NY): Farrar, Straus & Giroux; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Esteva A, Kuprel B, Novoa RA, Ko J, Swetter SM, Blau HM, et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature. 2017;542(7639):115–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Landon BE, Zaslavsky AM, Bernard SL, Cioffi MJ, Cleary PD. Comparison of performance of traditional Medicare vs Medicare managed care. JAMA. 2004;291(14):1744–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ayanian JZ, Landon BE, Zaslavsky AM, Saunders RC, Pawlson LG, Newhouse JP. Medicare beneficiaries more likely to receive appropriate ambulatory services in HMOs than in traditional Medicare. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(7):1228–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kauffman K, Worley C. Medicare annual wellness visits, proactive risk adjustment initiatives, coding, and your bottom line. Presentation at: American Medical Group Association Annual Conference; 2018. Mar 7–10; Phoenix, AZ. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, Barry MJ, Cabana M, Caughey AB, et al. Screening for cognitive impairment in older adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2020;323(8):757–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fowler NR, Perkins AJ, Gao S, Sachs GA, Boustani MA. Risks and benefits of screening for dementia in primary care: the Indiana University Cognitive Health Outcomes Investigation of the Comparative Effectiveness of Dementia Screening (IU CHOICE) trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(3):535–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 2020. Medicare Advantage and Part D rate announcement and final call letter fact sheet [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): CMS; 2019 April 1 [cited 2020 Sep 1]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/2020-medicare-advantage-and-part-d-rate-announcement-and-final-call-letter-fact-sheet [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pyenson BS, Steffens C. Including dementia in the Part C Medicare risk adjuster: health services issues [Internet]. Seattle (WA): Milliman; 2019. Feb [cited 2020 Sep 1]. Available from: https://www.milliman.com/-/media/Milliman/importedfiles/uploadedFiles/insight/2019/including-dementia-medicare-risk-adjuster.ashx [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.