Abstract

Projections of future food security require careful interpretation because they are often based on models that include only a subset of biophysical variables and have inherent uncertainties, caution Samuel Myers and colleagues

Over the past several years many global reports and scientific articles have offered guidance to policy makers on how climate change is likely to affect global food security. But these publications paint an incomplete, and likely overly optimistic, picture of the threat that anthropogenic environmental change poses to food production, nutrition, and health.

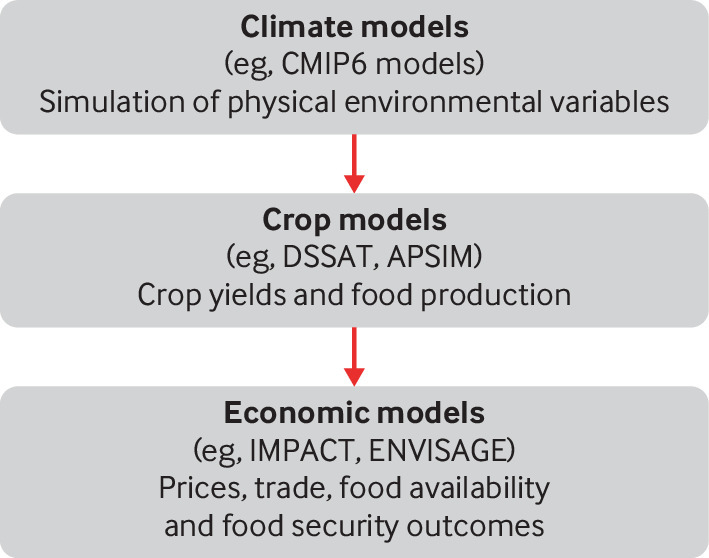

Projected effects of climate change on food security are often based on crop models that incorporate only a few dimensions of climate related biophysical change—usually characterized by changes in temperature and precipitation (fig 1). Omitted from these mathematical models are other biophysical changes related to a disrupted climate system and, importantly, other anthropogenic biophysical changes that are also likely to affect the quality or quantity of food the world can produce.

Fig 1.

Different models are connected in sequence to simulate future climate, food production, and food security outcomes. The outputs from climate models are inputs into crop models that, in turn, feed into economic models. In addition to the indicated inputs, crop models are also specified according to management, soil characteristics, and cultivar types, and economic models according to socioeconomic conditions1

Global food production depends on a host of biophysical conditions that are not captured in most crop modelling studies but are changing rapidly in response to human activities. We examine the ways in which current crop models might miss important environmental effects on food production. We discuss four main limitations to existing models and interpreting their output effectively to motivate action (though we focus on the first): the omission of key biophysical parameters; uncertainty in projection of physical climate variables, including precipitation and soil moisture; additional difficulty in understanding how long term climate change will influence short term extremes; and understudied non-linear interactions between co-evolving biological and physical variables.

This paper aims to provide policy makers with a more comprehensive overview of how human caused biophysical changes are altering food production and threatening human health, often in ways that cannot yet be quantified or incorporated into mathematical models. We introduce a note of caution about relying uncritically on current projections and emphasize the value of a precautionary principle to slow environmental change while building increased resilience into our global food system.

Modelling agricultural productivity

Most global crop models attempt to estimate future agricultural productivity, commonly for major commodities (such as grains and oilseeds), using a select few important biophysical parameters that regulate plant growth and yield, including temperature, precipitation, sunlight, atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2), and nutrient availability (fig 1). These environmental variables are simulated using general circulation models that integrate equations representing the motion, energetics, and other attributes of the global physical environment.

Economic models incorporate how changes in crop yields interact with social and economic forces—such as population growth, increases in per capita income, fluctuating food prices, dietary shifts, available farmable land, demographic changes, and agronomic technological change—to affect dietary intake or caloric adequacy and other outcomes.

These models enable simulation of processes that cannot be studied in a lab and have an important role relative to simpler conceptual models in encoding assumptions in an explicit and reproducible format. The complexity of such simulations, however, makes it computationally impractical to obtain more than a small number of plausible simulations, let alone the resources required to understand and communicate the output generated by such a highly multidimensional system. The current generation of crop models have struck this balance by focusing on the physical variables that are most directly influenced by greenhouse gas emissions.

This approach omits a much broader suite of other potent global scale environmental changes that are affecting agricultural productivity. A core precept of the emerging field of planetary health is that anthropogenic environmental change is altering the structure and function of most of our planet’s natural systems and biophysical conditions.2 These changes include, but are not limited to, greenhouse gas induced climate change. Human activity is also changing land use and land cover; altering biogeochemical cycles; polluting air, water, and soil; reducing natural resources like fresh water and arable land; and driving the sixth mass extinction of life on Earth.

Biophysical changes omitted from most models

Table 1 describes ongoing biophysical changes known to affect food quality or quantity and describes what we know about their mechanism and effect on food production, human nutrition, and health outcomes. Most of these changes are not incorporated into traditional models of future food production. Declines in pollinating insects, for example, are limiting yields of fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes that are important in preventing heart disease, stroke, some cancers, and diabetes. Empirically, insufficient pollination accounts for roughly one quarter of the yield gap between the highest performing farms and average farms based on data from experimental farms on four continents.15 Warming oceans are shifting the population sizes and distribution of fisheries away from the tropics and towards the poles, jeopardizing access to wild harvested fish for nearly a billion people who depend on them for sufficient intake of critical nutrients.29 Although the precise mechanism remains uncertain, rising concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere are lowering the amount of iron, zinc, protein, and B vitamins in staple food crops, increasing the risk of deficiencies in these key nutrients for hundreds of millions of people.12 These effects are difficult to quantitatively represent because our level of understanding of the underlying dynamics is limited, and they are not incorporated into most models of future food production.

Table 1.

Selected effects of anthropogenic environmental shifts on global food production and health

| Stressor | Mechanism | Effect on future food production | Human nutrition and health consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heat stress3 | • Greater heat in a warming climate, when not ameliorated by greater water availability, decreases crop yields in low and mid latitudes by shortening its life cycle and increasing plant mortality • Crops grown in high latitudes benefit from warmer and thereby more suitable growing conditions • Temperature changes also alter suitability of land for agriculture, causing net declines in productive land from increasing aridity • Higher temperatures also lead to greater food contamination and spoilage • Livestock also suffer under heat stress by decreasing fertility, liveweight gain, and milk and egg production4 |

• Combined heat and water stress predicts average modelled future crop yield changes of 1-3% losses per decade for maize, rice, soybean, and wheat3

• But average projections like these are incomplete, cloaking very large uncertainties from highly imprecise predictions of future biophysical conditions, especially precipitation • Fungal and bacterial pathogens will increase in abundance and range, increasing spoilage of stored grain • Milk production for cattle may be reduced by 1-13% among largest producers owing to heat stress5 |

• Assumptions of future crop losses would increase food insecurity, and this would be more dramatic after 2050 as climate change accelerates • A study of the health impacts (through diet and nutrition) of combined effects of climate change (extending beyond heat stress in isolation) indicate a 10% rise in the food insecure population in 2050 under the scenario known as RCP 8.5 versus no climate change6 • But these and similar estimates are subject to uncertainties • Greater rates of aflatoxin contamination, primarily in maize, could drive higher human toxicity under warmer, drier conditions7 |

| Water availability (changes to precipitation patterns and extreme events)3 | • Future precipitation patterns are uncertain in direction and magnitude, but frequency of extreme events (floods, droughts) is likely to increase • Demands for higher yields and changing precipitation patterns will leave some existing cropland without sufficient water, requiring irrigation to meet needs • In some areas, irrigation might not be possible because of too little water or poor storage or transportation infrastructure |

• Models unconstrained by irrigation infrastructure (assuming all regional freshwater can be redistributed seamlessly to where it is needed) predict that irrigation is insufficient to offset climate change related effects: only 12-57% of climate caused crop yield losses could be offset by irrigation in 20908

• 25% of croplands (mainly in sub-Saharan Africa, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia) are also subject to “economic water scarcity,” whereby sufficient water exists but infrastructure is inadequate to capture and allocate it9 |

• Water scarcity is likely to imperil food security in regions already insecure and where future water availability might be insufficient to buffer climate driven yield losses with irrigation: China, India, Pakistan, Middle East, North Africa, and Mexico8

• Elsewhere, insufficient infrastructure could limit ability to take advantage of rainfall or deeper aquifers for agriculture, producing food shortfalls: sub-Saharan Africa, Central and Eastern Europe9 |

| Rising CO2 | • Higher CO2 in isolation can increase crop growth rate, but when combined with its consequential changes in climate (higher temperature, water stress) its benefit is lost • Elevated CO2 can also directly induce losses in nutrient density for staple crops like wheat, rice, legumes, potato, and maize10 • Initial recent experiments combining higher CO2, temperature, and water stress show inconsistent signals on nutrient density |

• Elevated CO2 (550 ppm) in isolation lowers zinc, iron, and protein content of major crops by 3-17%10 and B vitamins in rice by 13-30%11 | • Population newly at risk of deficiency owing to decline in crop quality: 175 million for zinc and 122 million for protein; 1.4 billion women (aged 15-49) and children (<5) live in countries at highest vulnerability to greater iron deficiency anaemia12

• The combined effect of CO2 on crop yield (including through climate change) and nutrient density results in reduced growth in global nutrient availability compared with baseline of 19.5% for protein, 13.6% for iron, and 14.6% for zinc13 |

| Loss of wild pollinators14 | • Loss of natural habitat and forage; harmful pesticides; changing phenology owing to climate change; greater invasion from new predators, pathogens, and competitors causing declines in abundance, range, and richness of most recorded wild pollinator species14

• Insufficient pollination reduces the yield of many healthy and nutritious foods15 16 • Poor pollination can also worsen crop quality |

• Trajectory of pollinators and their relation to future food production is understudied and difficult to predict • Stylized models of 50%, 75%, and 100% pollinator removal estimate up to 16-22% reductions in fruit, vegetable, and nut production17 |

• Highly simplified modelled losses of fruit, vegetable, and nut production owing to full pollinator removal could lead to 1.4 million additional deaths caused mainly by rises in chronic disease exacerbated by loss of healthy food groups17 |

| Pests and crop pathogens | • Rising temperatures and conversion of natural land to agriculture will worsen crop losses owing to changes in the range, population size, life history traits, or trophic interactions for most agricultural pests18

• Patterns of intensity and diversity of pathogen infections of crops are predicted to track yield trends; more infection in higher latitudes, lower in tropics19 • More abundant herbivorous pests may also increase vector transmission of pathogens |

• Highly simplified model linking temperature, metabolism, and crop losses estimated 10-25% yield losses in wheat, rice, and maize per degree of warming20

• Pathogen related crop losses will be highest in areas where yields increase most, thus blunting productivity gains19 • |

• An example of a theoretical widespread fungal rice disease outbreak in East Asia could result in 10-15% losses in total calorie intake both regionally and globally, primarily for poor countries (such as Madagascar, Laos, Myanmar) that cannot absorb ~250% price increases for rice21

• |

| Ground level ozone22 23 | • Plant damaging air pollutant produced mainly through photochemical reactions of anthropogenic emissions • Ozone production accelerates under warmer temperatures |

• 2050 high ozone scenario (RCP 8.5) predicts decreased global production of wheat, rice, maize, and soybean by 3.6%, worsening predicted losses from climate change alone (−11% to −15%)24

Strict pollution control measures (RCP 4.5) could increase productivity of these major crops by 3.1% relative to baseline24 |

• Dietary and health implications of ozone related crop losses have not been quantified, though are assumed to deepen food insecurity |

| Soil degradation 25 | • Multiple factors are degrading global agricultural soils, ranging from ubiquitous (soil erosion, loss of soil organic matter) to regional or local (contamination with heavy metals and chemicals, salinisation, acidification) • Climate change may accelerate soil degradation by accelerating soil erosion from more frequent and intense storms or greater saline groundwater intrusion into coastal areas • Other anthropogenic drivers may also degrade soils: heavy metal contamination in rapidly developing countries, salinisation from heavy irrigation, acidification from overapplication of ammonium based fertilizers |

• Average agricultural soil erosion outpaces formation, potentially lowering yields owing to losses of topsoil • Globally averaged agricultural soil erosion of 0.90-0.95 mm/year would cumulatively decrease annual crop productivity by 0.3% (0.1-0.4%): translates to 10.25% loss in 205025 • 20% of Chinese farmland is estimated to be contaminated with heavy metals, with potential implications for plant productivity and food safety25 Other drivers where present—salinisation, acidification, contamination, loss of soil organic matter, and biodiversity—will progressively decrease crop yields or cause failures if they exceed tolerance |

• Unless tackled, loss of productive soils could have implications for producing sufficient food, particularly in areas where soil is poorest and future population growth will be highest (mainly sub-Saharan Africa, also Asia and Latin America) |

| Fisheries changes26 | • Overfishing in weakly governed marine areas is unsustainable in a third of wild capture fisheries; wild capture fish harvest has plateaued in recent decades26

• Global growth of seafood consumption is therefore met by aquaculture, which faces its own challenges owing to diminishing availability of suitable farming locations and water, more aquatic disease outbreaks, and waning productivity gains • Climate change may affect seafood production by shifting suitable habitats of many fish polewards and also slightly decreasing populations; aquaculture might also be affected by loss of suitable production areas from higher temperatures, more disease transmission, and influx of invasive species |

• Strong growth in aquaculture, primarily in Asia, is generally predicted to meet fish demand in the coming decades, though some regions may see declines: African fish consumption is unlikely to keep pace with population growth, and per capita intake is predicted to decline from 10 to 9.8 kg/person/year by 203026

• But climate change could upend growth trends: under high emission climate change scenarios, nearly all wild capture fisheries and freshwater aquaculture will be outside of their historical temperature variability by 2100—a high risk for achievable and sustainable growth of seafood production27 |

• Many low latitude, low income countries in Latin America, Africa, and Asia are most nutritionally and economically reliant on wild capture and aquaculture fisheries, and least capable to adapt • At least 50 countries are predicted to face high risk across one or more dimension of wellbeing—health, nutrition, social, or economic—related to losses of aquatic food production by 2100 regardless of intensity of climate change27 |

| Biodiversity losses28 | • Diverse species assemblages support agriculture through many pathways: natural pest predators providing organic pest management, soil organisms increasing fertility and nutrient availability, wild food species contributing to more diverse diets, aquatic animals and plants purifying water and cycling nutrients, protecting against natural disasters (robust food webs resisting disease outbreaks, trees providing windbreaks, preventing floods by strengthening coastlines and riverbanks); also pollinators (discussed above) • Biodiversity is declining because of many drivers: land use change, pollution, overuse of agrochemicals, overharvesting, invasive species, poor forest and aquatic system management |

• Loss of species could have detrimental effects on the stability of food production, resilience to shocks, diversity of food types, and availability of key wild harvested foods • Lower biodiversity limits opportunities for sustainable intensification, potentially narrowing options for future yield growth • Diverse crops also provide natural breeding opportunities to increase yield or generate beneficial crop properties • By decreasing the diversity of foods (both on-farm and wild harvest), communities are less resilient to challenges, as diverse systems can adapt more easily to changes in environmental pressures or disasters |

• Reduced biodiversity could lead to hunger and malnutrition, particularly during extreme events owing to weak resilience • Poorer households in particular are most vulnerable, because of the low or no cost of biodiverse ecosystem services and less ability to cope with hardship (food shortages or high food prices, or both) • Loss of biodiversity could cause overuse of agrochemicals to fill natural organisms’ roles, leading to financial strain of poor farmers and pollution in nearby farms, habitats, and waterways 28 |

Changing environmental conditions include both biological and physical factors. Among the biological factors in flux are pollinating insects, agricultural pests and their predators, livestock health, status and distribution of global fisheries, diversity of wild type plant varieties, and access to wild harvested plants and animals. Physical changes include changes in air quality, land degradation, loss of arable land and salinisation caused by sea level rise, extreme weather, and the direct effects of increased atmospheric CO2 concentrations. Importantly, most of the excluded variables in table 1 imply a modest to severe negative impact on agricultural production. Given an incomplete picture of climate change and omission of other biophysical changes, current models of food production incompletely capture the true downside risks of anthropogenic environmental change on productivity and nutrition.

Large inherent uncertainty in climate models

At the same time, even the best studied climatic variables that are incorporated as inputs into current crop models are characterized by considerable uncertainty, limiting the predictive capabilities of those models. Predictions of future precipitation patterns are quite blurry. The most recent ensemble findings from a global collaboration of modelling groups (Coupled Model Intercomparison Project 6; CMIP6), which projected global precipitation until 2050, disagreed with previous projections; not only on the magnitude of future precipitation trends for much of the world, but even the direction of those trends in many tropical and sub-tropical regions.30 Projections of crop yields based on averages across ensembles of predictions should be interpreted together with the spread of possible outcomes. Furthermore, additional features that are important for projecting yield outcomes—such as soil properties, irrigation, and crop rotation intensity—can be scarce and unreliable, further reducing the precision of final outputs.31

Averaging out short term volatility

A further problem worth mentioning is that future changes in biophysical variables are often considered as averages, neglecting the key dimension of short term volatility. Climate extremes that influence agriculture are generally predicted to increase in the coming decades, and a warmer world is generally associated with a more active hydrologic cycle, making croplands more susceptible to floods and droughts.32

Volatility is likely to be a key determinant of food security and nutrition. In a given year, extreme events can overwhelm our ability to adapt and can push social and economic systems—global trade and supply chain networks, countries at risk of conflict—over the brink and into crisis, causing cascading effects for geographic regions and the world. Consideration of the interplay between a more volatile climate system and the socioeconomic systems upon which it acts is needed to account for the full risk of climatic change on food security and nutrition.

Non-linear interactions

Finally, the interactions between different types of biophysical change are understudied and poorly characterized. All biophysical parameters we describe are changing rapidly in response to human activities and in concert with each other. Together they have substantial, but difficult to gauge, implications for the availability and quality of food. Many of these areas are the subject of ongoing research, but are not yet well understood individually, let alone as part of a jointly evolving system.

Limited research points to non-linear relationships among many stressors, either reinforcing or offsetting each other. The toxic effect on crops of elevated ozone levels, for example, is expected to be weaker under higher atmospheric CO2 concentrations because most food plants can decrease stomatal intake and still receive the same amount of CO2, thereby limiting simultaneous ozone uptake. In the other direction, herbivorous pest pressure induces flowering crops to invest in defence over reproduction, reducing flower size, density, and nectar content, while also producing deterrent compounds in leaves, pollen, and nectar that are distasteful to pollinators. These responses have the unintended effect of causing plants to be less attractive to pollinators overall, reducing successful pollination and fruit yield in excess of that which might be damaged by pests.33 Both these examples show that the combined effect of any suite of stressors might result in unpredictable outcomes, which greatly complicates the ability to accurately forecast their net effect on crop yields, diets, and nutrition in a world rapidly changing across many dimensions.

Implications of underestimating risks to food security

In today’s context, we cannot ignore our growing vulnerability to disruptions in food trade. Several trends converge to generate this vulnerability.34 First, we have seen increasing reliance on food trade to achieve nutritional sufficiency as countries focus more on producing high value crops and less on the ability to subsist on domestic production.

Second, both agricultural and wild harvested fisheries production are expected to shift away from the tropics and towards the poles in a warming world. But human population growth will occur primarily in the tropics, further disconnecting people from the food they rely on.

Third, more extreme weather events are likely to cause more frequent climate shocks, and we have seen that food trade markets often behave perversely, closing doors to exports to protect domestic food prices and thereby amplifying the effect of the climate shocks on food prices.

This increased vulnerability has been tragically on display over the past three years, first with disruptions associated with the covid-19 pandemic and now in response to the Russian Federation’s invasion of Ukraine that is causing grain, cooking oil, and fertilizer shortages and sending cereal and other food commodity prices to historic highs while throwing tens of millions of people in poor, import dependent countries into new risk of food insecurity. Though increases in food trade to date have been beneficial overall to increase the efficiency and resilience of the global food system to disruptions in any one location, recent events have revealed a continued and growing vulnerability inherent to our dependence on food trade in a highly interconnected world experiencing more biophysical and social volatility.

What does all of this mean to policy makers? We must be very cautious in interpreting projections of food production or food security because they rely on models that omit many important biophysical changes and include other variables with profound, irreducible uncertainties. This is not a criticism of the models but a reflection of the limitations in our understanding of both the fundamental Earth system processes and their interactions. We should also be concerned that the combination of accelerating human caused environmental change and growing dependence on a volatile food trade system are creating large vulnerabilities for human food security, nutrition, and health. In this context, policies to reduce vulnerability become enormously important (box 1).

Box 1. Policies to reduce vulnerability .

Redoubling our efforts to mitigate climate change and stabilize other human caused environmental changes

Research into diverse crop varieties that can grow in altered biophysical conditions

Impounding more water in dams or aquifers to buffer against more volatile hydrologic extremes

Strengthening and broadening international trade agreements to ensure efficient food trade during crises

Improving food storage and transport systems to protect post-harvest yields against spoilage and minimize loss of perishable, nutritious foods

Engaging in multinational grain stock partnerships to allow for a freer flow of food during lean years

Improving the quality and comprehensiveness of data relevant to agriculture and food (such as crop yields, price elasticities, food waste)

Economic policies to increase broad based income growth or strengthen social safety nets to protect vulnerable populations.

Conclusion

Human beings are transforming Earth’s biophysical conditions with worrisome consequences for global food security, nutrition, and health. Our most powerful tools to understand the scope of the challenge are models, which are often used to explain how selected dimensions of physical, biological, and human systems may interact to affect food security. But these models cannot capture the full complexity of the real world and should not be relied on in isolation to provide an accurate picture of the future.

As we describe, many factors beyond the scope of current models—omitted variables, inherent uncertainty, short term volatility, and non-linear interactions—suggest a more complex and risky future than current model projections might indicate. Building policy around model output that might underestimate true human consequences could leave millions of people vulnerable to food and nutritional insecurity in the coming decades. It is, therefore, incumbent upon policy makers to act in caution to help safeguard an adequate supply of nutritious food in the face of a changing, erratic world.

Key messages.

Projections of human food production, hunger, and nutrition over the 21st century are informed by crop models that rely on a few key drivers to quantify food production into the future

Crop models omit many key biophysical variables that are already changing rapidly in ways that are likely to reduce the quality or quantity of food produced into the future

Irreducible uncertainties and unaccounted for volatility in climate projections, paired with non-linear interactions among many climate and biophysical variables, limit the accuracy of agricultural projections

Policy makers seeking to ensure future food security should interpret such projections cautiously

Pre-emptive action might be warranted because uncaptured complexity may lead to worse outcomes than current models project

Contributors and sources: SM has studied and reported widely on human health impacts of global environmental change, a field recently termed “planetary health.” MS researches how global environmental changes may affect human diets, nutrition, and health, now and in the future. KW conducts and leads research on foresight related to agriculture, food security and climate change. PH works on climate change and its implications for agriculture. JF has experience leading field research and global policy on sustainable diets and the role of environment, climate, and ecosystems on food security.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to declare.

This article is part of a series commissioned by The BMJ for the World Innovation Summit for Health (WISH) 2022. The BMJ commissioned, edited, and made the decisions to publish. The series, including open access fees, is funded by WISH. The steering committee members were Tim Benton, Sheryl Hendriks, Renzo R Guinto, Sam Myers, Jess Fanzo, Hugh Montgomery, Nassar Al Khalaf, and Gonzalo Castro de la Mata. Richard Hurley and Paul Simpson were the lead editors for The BMJ.

References

- 1. Nelson GC, Valin H, Sands RD, et al. Climate change effects on agriculture: economic responses to biophysical shocks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:3274-9. 10.1073/pnas.1222465110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Myers S, Frumkin H. Planetary health: protecting nature to protect ourselves. Island Press, 2020. 10.5822/978-1-61091-966-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kerr RB, Hasegawa T, Lasco R, et al. Food, Fibre, and other Ecosystem Products. In: Climate Change. Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, 2022, https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGII_FinalDraft_Chapter05.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4. Godde CM, Mason-D’Croz D, Mayberry DE, Thornton PK, Herrero M. Impacts of climate change on the livestock food supply chain; a review of the evidence. Glob Food Sec 2021;28:100488. 10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thornton P, Nelson G, Mayberry D, Herrero M. Impacts of heat stress on global cattle production during the 21st century: a modelling study. Lancet Planet Health 2022;6:e192-201. 10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nelson G, Bogard J, Lividini K, et al. Income growth and climate change effects on global nutrition security to mid-century. Nat Sustain 2018;1:773-81. 10.1038/s41893-018-0192-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Battilani P, Toscano P, Van der Fels-Klerx HJ, et al. Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change. Sci Rep 2016;6:24328. 10.1038/srep24328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Elliott J, Deryng D, Müller C, et al. Constraints and potentials of future irrigation water availability on agricultural production under climate change. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:3239-44. 10.1073/pnas.1222474110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rosa L, Chiarelli DD, Rulli MC, Dell’Angelo J, D’Odorico P. Global agricultural economic water scarcity. Sci Adv 2020;6:eaaz6031. 10.1126/sciadv.aaz6031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Myers SS, Zanobetti A, Kloog I, et al. Increasing CO2 threatens human nutrition. Nature 2014;510:139-42. 10.1038/nature13179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhu C, Kobayashi K, Loladze I, et al. Carbon dioxide (CO2) levels this century will alter the protein, micronutrients, and vitamin content of rice grains with potential health consequences for the poorest rice-dependent countries. Sci Adv 2018;4:eaaq1012. 10.1126/sciadv.aaq1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smith MR, Myers SS. Impact of anthropogenic CO2 emissions on global human nutrition. Nat Clim Chang 2018;8:834-9. 10.1038/s41558-018-0253-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Beach RH, Sulser TB, Crimmins A, et al. Combining the effects of increased atmospheric carbon dioxide on protein, iron, and zinc availability and projected climate change on global diets: a modelling study. Lancet Planet Health 2019;3:e307-17. 10.1016/S2542-5196(19)30094-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.IPBES. The assessment report on pollinators, pollination and food production : IPBES, 2016. http://digitallibrary.un.org/record/1664349

- 15. Garibaldi LA, Carvalheiro LG, Vaissière BE, et al. Mutually beneficial pollinator diversity and crop yield outcomes in small and large farms. Science 2016;351:388-91. 10.1126/science.aac7287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Smith MR, Mueller ND, Springmann M, et al. Pollinator deficits threaten human health and economic activity worldwide [in review]. Environ Health Perspect (in review). [Google Scholar]

- 17. Smith MR, Singh GM, Mozaffarian D, Myers SS. Effects of decreases of animal pollinators on human nutrition and global health: a modelling analysis. Lancet 2015;386:1964-72. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lehmann P, Ammunét T, Barton M, et al. Complex responses of global insect pests to climate warming. Front Ecol Environ 2020;18:141-50. 10.1002/fee.2160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chaloner TM, Gurr SJ, Bebber DP. Plant pathogen infection risk tracks global crop yields under climate change. Nat Clim Chang 2021;11:710-5. 10.1038/s41558-021-01104-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Deutsch CA, Tewksbury JJ, Tigchelaar M, et al. Increase in crop losses to insect pests in a warming climate. Science 2018;361:916-9. 10.1126/science.aat3466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Godfray HCJ, Mason-D’Croz D, Robinson S. Food system consequences of a fungal disease epidemic in a major crop. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2016;371:20150467. 10.1098/rstb.2015.0467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ainsworth EA, Yendrek CR, Sitch S, Collins WJ, Emberson LD. The effects of tropospheric ozone on net primary productivity and implications for climate change. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2012;63:637-61. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Emberson LD, Pleijel H, Ainsworth EA, et al. Ozone effects on crops and consideration in crop models. Eur J Agron 2018;100:19-34. 10.1016/j.eja.2018.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tai APK, Martin MV, Heald CL. Threat to future global food security from climate change and ozone air pollution. Nat Clim Chang 2014;4:817-21. 10.1038/nclimate2317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.FAO. Status of the world’s soil resources: main report. Rome, Italy: FAO 2015. https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/c6814873-efc3-41db-b7d3-2081a10ede50/

- 26.FAO. The state of world fisheries and aquaculture 2020 : sustainability in action. FAO, 2020. 10.4060/ca9229en [DOI]

- 27. Tigchelaar M, Cheung WWL, Mohammed EY, et al. Compound climate risks threaten aquatic food system benefits. Nat Food 2021;2:673-82. 10.1038/s43016-021-00368-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bélanger J, Pilling D. FAO C on GR for F and A. The state of the world’s biodiversity for food and agriculture. 2019. https://www.fao.org/3/CA3129EN/CA3129EN.pdf

- 29. Golden CD, Allison EH, Cheung WWL, et al. Nutrition: Fall in fish catch threatens human health. Nature 2016;534:317-20. 10.1038/534317a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee J-Y, Marotzke J, Bala G, et al. Future global climate: scenario-based projections and near-term information. In: Climate change 2021 : the physical science basis. contribution of working group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, 2021:553-672. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Grassini P, van Bussel LGJ, Van Wart J, et al. How good is good enough? Data requirements for reliable crop yield simulations and yield-gap analysis. Field Crops Res 2015;177:49-63. 10.1016/j.fcr.2015.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seneviratne SI, Zhang X, Adnan M, et al. Weather and climate extreme events in a changing climate. In: Climate Change 2021: The physical science basis. Contribution of working group i to the sixth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, 2021:1513-766. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jacobsen DJ, Raguso RA. Lingering effects of herbivory and plant defenses on pollinators. Curr Biol 2018;28:R1164-9. 10.1016/j.cub.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mbow C, Rosenzweig C, Barioni LG, et al. Food security. In: Shukla PR, Skea J, Calvo Buendia E, et al, eds. Climate change and land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems. 2019. https://www.ipcc.ch/srccl/chapter/chapter-5/