Abstract

Immigrant women in Sweden often have unmet sexual and reproductive health (SRH) needs. Successful contraceptive counselling may improve their sexual and reproductive health and rights. The unique Swedish model, with midwives as the main providers of contraceptive counselling, is important for immigrant women’s health at both individual and societal levels. This study explored immigrant women’s perspectives on receiving contraceptive counselling from midwives in Sweden, in order to obtain deeper knowledge about the factors they perceive as important in the counselling situation. Nineteen in-depth individual interviews were conducted from December 2018 to February 2019, followed by qualitative manifest and latent content analysis. Trust emerged as the overall important factor in the contraceptive counselling meeting. Knowledge was lacking about the midwife’s professional role as a contraceptive counsellor. Contraceptive counselling was seen as a private matter not easily shared with unfamiliar midwives or interpreters. Previous experiences of contraceptives and preconceptions were important considerations for contraceptive choice, but communicating these needs required trust. Women also wanted more knowledge about contraceptives and SRH care and rights. Cultural and social norms concerning when and why to use contraceptives needed to be acknowledged in the midwife encounter. Although immigrant women want more knowledge about contraception, a trustful relationship with the midwife is needed to be able to make informed contraceptive choices. Midwives may need increased awareness of the many factors influencing immigrant women's choices to ensure their contraceptive autonomy. Policy changes that promote new ways of counselling and ability to provide continuous care are needed.

Keywords: immigrant women, contraceptive counselling, midwives, trust, health literacy, outreach interactions

Résumé

Les immigrantes en Suède ont souvent des besoins insatisfaits de santé sexuelle et reproductive (SSR). Des consultations réussies sur la contraception peuvent améliorer leur santé et leurs droits sexuels et reproductifs. Le singulier modèle suédois, dans le cadre duquel les sages-femmes sont les principales prestataires de conseils contraceptifs, est important pour la santé des immigrantes aux niveaux aussi bien individuel que sociétal. Cette étude a exploré les perspectives des immigrantes sur les conseils contraceptifs qui leur ont été prodigués par des sages-femmes en Suède, afin de mieux comprendre les facteurs qu’elles jugent importants dans la consultation. Dix-neuf entretiens individuels approfondis ont été menés de décembre 2018 à février 2019, suivis d’une analyse qualitative des contenus manifeste et latent. La confiance est apparue comme facteur d’importance globale dans les consultations sur la contraception. Les immigrantes manquaient de connaissances sur le rôle professionnel des sages-femmes comme conseillères en matière de contraception. Elles considéraient que les conseils contraceptifs étaient une question privée difficilement partagée avec des sages-femmes ou des interprètes inconnus. Les expériences précédentes avec les contraceptifs et les idées préconçues étaient des considérations importantes pour le choix de la contraception, mais la confiance était nécessaire pour pouvoir communiquer ces besoins. Les femmes voulaient aussi en savoir plus sur les contraceptifs ainsi que les soins et les droits de SSR. Les normes culturelles et sociales concernant le moment et le motif de l’utilisation de contraceptifs devaient être prises en compte pendant la rencontre avec la sage-femme. Même si les immigrantes veulent être mieux informées sur la contraception, une relation de confiance avec la sage-femme est indispensable pour qu’elles puissent faire des choix éclairés en matière de contraception. Il est possible que les sages-femmes aient besoin de mieux connaître les nombreux facteurs qui influencent les choix des immigrantes pour garantir leur autonomie contraceptive. Des changements de politiques sont nécessaires pour promouvoir de nouvelles façons de conseiller et la capacité d’assurer fournir des soins suivis.

Resumen

Las mujeres inmigrantes en Suecia a menudo tienen necesidades de salud sexual y reproductiva (SSR) insatisfechas. La consejería anticonceptiva exitosa podría mejorar su salud y derechos sexuales y reproductivos. El modelo sueco único, con parteras como principales proveedores de consejería anticonceptiva, es importante para la salud de las mujeres inmigrantes a nivel individual y social. Este estudio exploró las perspectivas de mujeres inmigrantes con respecto a recibir consejería anticonceptiva de parteras en Suecia, a fin de obtener más conocimientos sobre los factores que perciben como importantes en la situación de consejería. Entre diciembre de 2018 y febrero de 2019, se realizaron 19 entrevistas a profundidad individuales, seguidas de análisis cualitativo de contenido manifiesto y latente. Confianza surgió como factor importante general en la reunión de consejería anticonceptiva. Se carecía de conocimiento sobre el rol profesional de la partera como consejera anticonceptiva. La consejería anticonceptiva era considerada como un asunto personal que no se comparte con facilidad con parteras o intérpretes desconocidos. Experiencias e ideas preconcebidas anteriores con relación a los métodos anticonceptivos eran importantes consideraciones para la elección del anticonceptivo, pero para comunicar estas necesidades se necesitaba confianza. Además, las mujeres querían conocer más sobre los servicios y derechos de anticoncepción y SSR. En el encuentro con la partera, era necesario reconocer las normas culturales y sociales relativas a cuándo y por qué usar anticonceptivos. Aunque las mujeres inmigrantes quieren conocer más acerca de la anticoncepción, una relación de confianza con la partera es necesaria para poder tomar decisiones informadas sobre la anticoncepción. Las parteras posiblemente necesiten más sensibilización sobre los numerosos factores que influyen en las decisiones de las mujeres inmigrantes para poder garantizar su autonomía anticonceptiva. Se necesita realizar cambios a las políticas que promueven nuevas maneras de brindar consejería y capacidad para brindar atención continua.

Introduction

According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), one billion people – one in every seven – are migrants.1,2 About 250 million people are international migrants, and nearly half of them are women.1 Globally, women are migrating to new countries, bringing with them their perspectives and knowledge about sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) and contraceptives.1 Worldwide there is a lack of education about family planning, and access to contraceptives is limited due to financial, political and legislative reasons and social norms governed by traditions, religion and culture.3 Furthermore, women and girls are not given access to or sufficient education and knowledge about their possibilities and rights to choose if and when to have children and with whom, which is their human right.4 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 270 million women globally who want to stop or delay childbearing are not using any method of contraception to prevent pregnancy.5 UNFPA data report that only 55% of women worldwide can make their own decisions about their sexual and reproductive health (SRH) and about contraception.1 Consequently there are still a high number of maternal deaths, unintended pregnancies, and unsafe abortions being performed every day.6 Women and girls fleeing from environments characterised by gender-based violence, child marriage, insecurity and abuse face new challenges as migrants. SRH for migrant women is, according to UNFPA, under-prioritised globally, leading in consequence to unplanned pregnancies, unsafe abortions and lack of knowledge of contraceptives and access to contraceptives.7,8

There is no universally accepted definition of the term “migrant”.9 The International Organization of Migration defines the term “migrant” as a person who moves away from his or her place of usual residence, whether within a country or across an international border, temporarily or permanently, and for a variety of reasons including violence, conflict, natural disasters and human rights abuse, whereas the term “immigrant” denotes persons who move into a country which becomes their country of usual residence.9,10 The European Region accounts for 35% of the global international immigrant population, of whom half are women, many of childbearing age.11 In Sweden, about 25% of the population are immigrants or descendants of immigrants, i.e. foreign-born or having at least one parent who was born outside of Sweden, and about 20% of the population is foreign-born.12,13 The immigrant population in Sweden encompasses a heterogenous group of people representing about 200 different countries, with a majority from non-European countries and with different cultural and socio-economic backgrounds.12 In this study immigrant women are defined as women who are foreign-born.

Migrants are a heterogeneous group variously influenced by the interaction of the process of migration and exposure to risks and access to social determinants of health in the country of origin and the host country.14 While country of origin, previous health status and socio-economic status are factors that influence migrants’ health, the migratory process itself can cause significant impact on people’s physical and mental health and their well-being.14 The healthcare system's response is therefore described as one of the essential elements of the intersection between migrants and health, more specifically, equal access to equal health care.15 Even if health is an individual responsibility, there is a collective responsibility to develop health systems that are sensitive to migrants’ cultural and health characteristics.15

WHO Europe reports in their technical guidance for improving refugee and migrant women’s and children's health, that newly arrived women and those with uncertain legal migrant status are at particularly increased risk of negative pregnancy outcomes and that there is a higher burden of disease and poor health outcomes in refugee and immigrant women, especially women coming from low-income to high-income countries.16 These outcomes are linked to several different combinations of pre-existing conditions, including the socio-economic situation in the host country and lack of social support.16

Previous research in Western Europe including Sweden shows that immigrant women have higher rates of unintended pregnancies and induced abortions and that contraceptive use is lower than for native women.17,18 One reason for this is lower utilisation of SRH services, including family planning.15 Lower levels of health literacy, language barriers, lack of awareness of rights, health professionals’ lack of awareness of access to rights and lack of acceptability of SRH services for socio-economic, political or cultural reasons are some of the barriers affecting many immigrant women’s reproductive health compared to native-born women.19–24 Quality of health care that includes a healthcare system and healthcare personnel with regard for immigrant women's particular situation and the receiving country’s law and policies are factors to be recognised for making contraceptive counselling and access to contraceptives possible for all women, thereby increasing gender equality.19–24

Sweden is a country with a long tradition of free contraceptive counselling and subsidised contraceptives.25 Almost 80% of all contraceptive counselling in Sweden is provided by midwives and 20% by gynaecologists.18,26 Contraceptive counselling is mainly provided by midwives at maternal health clinics and at youth sexual health centres.27 It is free of charge and can easily be accessed by appointment.27 This Swedish model, with educated midwives acting as healthcare providers for all healthy women's SRH, is unique.28,29 The aim, according to official policies and guidelines, is to provide women and youth with an individually tailored, safe and effective contraceptive that prevents unwanted pregnancy but preserves fertility until pregnancy is planned.27 Despite this model, there has been a rise in unmet needs of contraceptive use from 9% to 15% in recent years.30

Unmet need refers to women who do not wish to become pregnant and do not use a contraceptive method.7 According to Senderowicz, unmet need is measured and accounted for by the indicator “proportion of need satisfied by a modern method”, an indicator that is included in the Sustainable Development Goals.31 Promotion of long-active reversible contraceptives (LARC) has been implemented in Sweden to reduce unintended pregnancies, and although uptake has been shown to be satisfactory among immigrant women, it is unknown to what extent this represents immigrant women's own needs, or those of the healthcare system.32,33 Women’s contraceptive use and choice of method are often described and measured in relation to fertility rates, use of modern methods, unintended pregnancies and induced abortions.34,35 Senderowicz suggests that the way unmet need is calculated, using modern contraceptive method use as a primary marker of success and measuring fertility rates, is not in line with promoting reproductive health and rights.31 Contraceptive autonomy refers to women being able to decide for themselves what they want and when they want it in regard to contraceptive use and then to realise that decision.31 By aiming at contraceptive autonomy as a goal, autonomous choices of women including the choice of non-use of contraception would be considered to be a positive outcome and not an unmet need.31 Senderowicz states that some forms of contraceptive coercion, such as focusing on maximising use of contraception, would be reduced if the emphasis was not on fertility rates but rather on enhancing women’s autonomous choice under the domains of informed choice, full choice and free choice.31 Thus, optimal contraceptive counselling should promote women’s right to contraceptive autonomy.

Ensuring that immigrant women's contraceptive counselling needs are fully met is vital for Sweden's commitment to the developmental goals set out in Agenda 2030 and the right to receive universal health coverage.36 Sweden is a country with a governmental feminist foreign policy plan where one priority is ensuring equal access to contraception and improving the SRHR of all women and girls is the main priority.37 Contraceptive counselling and the right to choose contraceptives of individual preference are important aspects of SRHR and also of the right to receive universal health coverage.36 Access to contraceptive counselling and contraceptives may enable immigrant women to be an equal part of the political, economic and social aspects of society.36,38–40 However, the Swedish system of providing contraceptive counselling and education for women about different options has not been adjusted to the changing demographic profile of the Swedish population and its changing needs.41,42

Furthermore, the first encounter with the Swedish health system for newly arrived immigrant women is often with a midwife. Previous research shows that it is during the perinatal period that newly arrived immigrant women establish first contact with the Swedish health system and midwives, and this experience has an impact on their future views and use of health care.43

Therefore, it is important to gain a deeper understanding of how immigrant women perceive the contraceptive counselling currently provided by midwives in Sweden. The aim of this study was to explore immigrant women’s perspectives on contraceptive counselling provided by midwives in Sweden. More specifically, the study aimed to gain an understanding of how immigrant women experience the midwife’s role, skills and prerequisites and of immigrant women’s perceptions of what they need to receive from the midwife, in order to optimise contraceptive counselling.

Methods

Study design

The study utilised a qualitative research design based on individual in-depth interviews. This approach was chosen to gain a deeper understanding and insight into immigrant women’s perspectives on the research topic. Individual in-depth interviews are considered suitable for exploring sensitive topics, and to be flexible according to the informants’ needs and life conditions.44

Study setting

The study was carried out in Malmö in southwestern Sweden. Malmö is Sweden's third largest city. About 45% of Malmö's 344,166 inhabitants are of immigrant descent, with more than 184 nationalities represented.45 Afghanistan, Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Iran, Iraq, Somalia and Thailand are some of the most common countries of origin represented. Malmö is the Swedish city with the largest proportion of non-European immigrants in relation to the population size.46 The city has a young population with 48% of the inhabitants under the age of 35 years.

Data collection

Data collection took place from December 2018 through February 2019, with interviews conducted by the first author. A purposive sampling strategy was used for this study, as it was considered to be the most suitable methodology to achieve the study aim.44

Two different locations, a government-supported association for immigrant women and a youth sexual health care clinic, were chosen to access a heterogeneous sample of participants with variations in age, perspectives and perceptions of the research question. Contact was established with staff from both locations. The contact persons acted as gatekeepers and established contact with potential participants who met the criteria set for the study aim: immigrant women (foreign-born) between 18 and 49 years old, residing in Sweden for at least one year, speaking Swedish or English or, if needed, willing to use an interpreter, and having experience of contraception counselling provided by a midwife in Sweden within the past 10 years. One of the gatekeepers was working with the association and one gatekeeper was located at the youth health clinic. The gatekeepers gave oral and written information about the study to potential participants. Those women who were interested to participate in the study left their contact information with the gatekeeper who in turn forwarded the information to the first author. The gatekeeper did not receive further information about who participated in the study. Initially, four pilot interviews were conducted to test and evaluate the purposive recruitment and the interview guide. The pilot interviews were conducted at one of the smaller associations for immigrant women in Malmö. The pilot interviews were deemed to be of sufficient quality to be included in the study. No changes needed to be made in the original version of the interview guide and research design. Interviews were conducted until a sense of closure was attained whereby no new information was obtained. Seventeen interviews were conducted from the immigrant women’s association and two interviews from the youth sexual health clinic. Thirteen interviews were conducted at the immigrant women’s association in a secluded room of the participant's choice with no one else present. One interview was conducted at the participant’s home and one interview at a secluded area at the participant's workplace. Nineteen interviews altogether were conducted and included in the study.

The interviews started with general questions about the participant's background, followed by open-ended questions concerning the individual experiences of contraceptive counselling provided by midwives. The interviews were performed using a semi-structured interview guide according to Kvale.27 Topics in the interview guide concerned the following areas: pre-understanding, accessibility, needs, expectations, trust, relations and communication during contraceptive counselling with midwife. Open-ended questions such as “what expectations did you have about contraceptive counselling provided by a midwife”, “how did you experience the information that was given”, “how did you manage language barriers if any”, “can you describe your relation to the midwife” and “what were your needs and were they met” were asked. Follow-up questions were asked, such as “can you tell me more about how you were feeling” or “can you describe this situation more in depth”. The length of the interviews varied between 25 and 55 min (median 35 min). All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Eighteen interviews were conducted in Swedish and one interview was conducted in English. The transcripts were translated from Swedish to English by the first author.

Data analysis

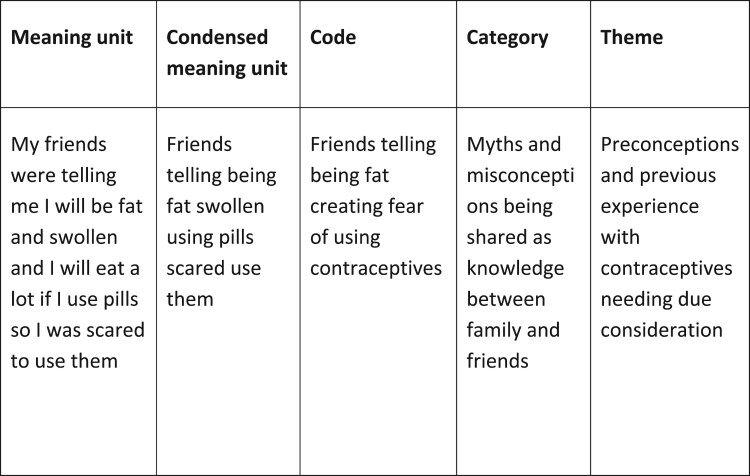

The data were analysed according to qualitative content analysis with an inductive approach, as described by Graneheim and Lundman.47 All interviews were read through several times to gain a sense of the material. This was followed by identifying meaning units, condensing meaning units, coding, aggregating codes into categories and identifying emerging themes. By selecting meaning units, the process of de-contextualisation of the data started according to Graneheim and Lundman.47 The process of de-contextualisation continued with condensing and the coding of the data.48 After coding the data, the codes were aggregated into categories and the data started to re-contextualise.48 The process of continuously analysing and reading through the codes and categories facilitated the emergence and identification of the latent themes. Throughout the analytical process, the first author held discussions with the co-authors to obtain a thorough level of shared understanding regarding the text analysis and the interpretation of the findings. See Figure 1 for an example of the analytical process.

Figure 1.

Example of the analytical process.

Ethical considerations

The participants received oral and written information from both the gatekeepers and the interviewer about the purpose of the study, voluntary participation, and were told that they could terminate or withdraw their participation at any time. Consent to participation in the study was gathered before interview started from the participants orally and in writing. To ensure further anonymity of each study participant all were assigned a study identity number. (P1–P19)

The study was approved 18 December 2018, by the Regional Research Ethics Board in Lund, Sweden (dnr. 2018/989).

Results

In total, 19 immigrant women were interviewed. All of the included study participants met the inclusion criteria. The participants were all born in a non-European country. Furthermore, all participants mentioned belonging or professing to a religion during the interviews. A socio-demographic profile overview of the study participants is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study participants (N = 19).

| Profile of the participants | |

|---|---|

| Age of the participants: | 19–49 years. |

| Median: 38 years. | |

| Countries of origin: | Ghana, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, Thailand and Turkey. |

| Years of residency in Sweden: | 1–35 years |

| Median: 15 years | |

| Education: | N = 1 no schooling, |

| N = 14 basic education | |

| N = 4 higher education. | |

| Working experience: | N = 13 no work experience |

| N = 6 some working experience (7 years was the longest period of work experience). | |

| Civil status: | N = 16 married |

| N = 1 divorced | |

| N = 2 unmarried | |

| Parity: | N = 17 > 2 children |

| N = 2 nulliparous. | |

| Religions mentioned were: | Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam. |

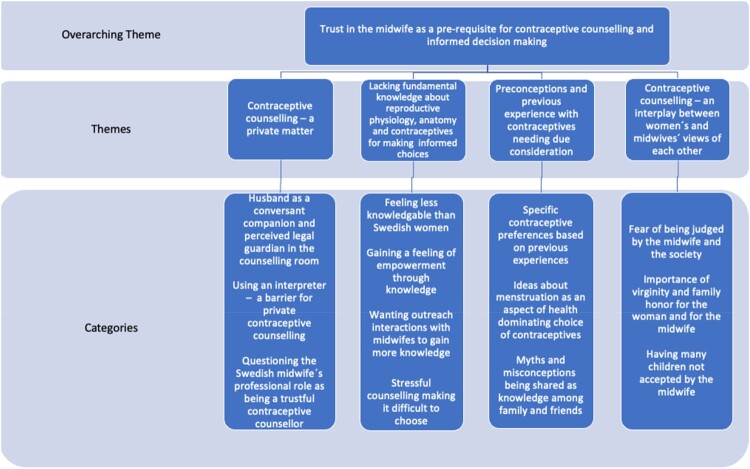

One overarching latent theme emerged during the analysis: “Trust in the midwife as a prerequisite for contraceptive counselling and informed decision making”. The overarching theme was based on four themes and 13 categories as presented in Figure 2 and described further in the text.

Figure 2.

Themes and categories emerging from the interviews.

Trust in the midwife as a pre-requisite for contraceptive counselling and informed decision-making

The overarching latent theme described the importance of trust. Without feeling trust, it was not possible to rely on the provider of contraceptive counselling, in this study the midwives, and their professional advice.

Contraceptive counselling – a private matter

The theme “Contraceptive counselling – a private matter” concerned meeting and revealing one’s personal life to someone who was unfamiliar and who, according to the participants, might have a different approach to contraceptives and contraceptive counselling from their own.

Husband as a conversant companion and perceived legal guardian in the counselling room

This category described the importance of having the husband present in the room. One reason was that the participants felt shy and insecure about sharing intimate and private matters with an unknown midwife. Furthermore, the husband often came along as a conversant companion when, as described by the participants, “the woman felt she lacked sufficient knowledge about contraceptives”. According to the participants, the husband often had a greater knowledge about contraceptives and the Swedish language, and it was usually the husband who paid for and provided contraceptives. The participants stated that they were afraid of choosing something that would disturb their mutual sexual life and feared that the midwife might give them something that interfered with this. Husbands also accompanied the woman as legal guardian, according to the participants, to ensure that no decision was taken, or no document was signed without the woman having enough knowledge about it. Participants coming from countries that were described as having low trust towards healthcare personnel and authorities felt that it was difficult to know whether it was possible to trust the midwife's advice as an authority or not, and needed the husband's confirmation.

“My husband he is working … he knows these things … you know … he speaks Swedish … little English … . I don’t take my ID card with me … what if they give me something I don’t know … maybe I sign a document or something … he knows.” (P14)

Using an interpreter – a barrier for private contraceptive counselling

This category described the participants’ feelings of discomfort and lack of trust when using an interpreter during contraception counselling. Talking about contraceptives was regarded as a private matter and participants felt shy talking about private details of sexual and reproductive issues to someone unknown, as the interpreter described. Some interpreters were known to the women from the local home country community, and participants described not having proper confidentiality and being afraid of the consequences. Using an interpreter by phone was better than having an interpreter in person in the counsellor's room, even though it was described as being difficult when wanting to have a deeper discussion about contraceptives. According to the participants, it would be better for improved communication to have more midwives with an immigrant background, but at the same time, some participants felt that meeting an immigrant midwife speaking the same language was too private and too personal.

“I had an interpreter … my friend was with me … I know little Swedish and my friend know little … we both understood … we did not get all information from the interpreter … she was not saying everything midwife was saying … so I stop using interpreter … . I say better speak slowly … slowly … or bring my friend … we have the same midwife.” (P1)

Questioning the Swedish midwife’s professional role as being a trustful contraceptive counsellor

This category described the professional role of the Swedish midwife in general, and as a contraceptive counsellor in particular, as not being clear to the participants. Being new to the Swedish health system, participants felt insecure about the Swedish midwife's competency, wondering if she was educated enough, comparing her to medical doctors and to midwives from their home countries and thereby wondering whether it was possible to have confidence in her provision of health care and her ability to provide confidentiality and privacy.

“Actually this thing with midwives … in our countries they do not have any education so we have gynecologists … if you are poor and you cannot pay … you see the midwife … the midwife has no formal education … her knowledge is something inherited from her mother or grandmother … so you choose … if you go to uneducated midwife at the governmental health clinic which is for free … but most women go to gynecologist … they pay … they don’t want to take the risk.” (P6)

When trust was established, the participants expressed a wish for seeing the same midwife through all kinds of care and different life cycles. A trusted and well-known midwife was seen as a trusted companion through life, like a sister or a mother.

“You know … it was my first midwife and I loved her … she was like a mother to me and I was her child or … like a sister … she had a warmth in her voice … .it is important that the midwife is kind and warm … not having a wall between us … in my country we have one midwife same midwife … .Why can we not have one same midwife like we have a family doctor? … ..” (P5)

Lacking fundamental knowledge about reproductive physiology, anatomy and contraceptives for making informed choices

The theme “Lacking fundamental knowledge about reproductive physiology, anatomy and contraceptives for making informed choices” reflected participants’ views that many immigrant women had limited or no knowledge about the reproductive system, anatomy and types of contraceptives. Having knowledge was perceived as fundamental for being able to receive and trust the information given by the midwife at the contraceptive counselling meeting and for making an informed choice.

Feeling less knowledgeable than Swedish women

This category described participants’ belief that they did not have the same level of knowledge as “Swedish women”. Participants felt that there was a difference in fundamental knowledge about anatomy and contraceptives depending on whether one had a Swedish background or whether one had a foreign background. The participants described having no or very little education about SRH in school in their home countries. The participants who came to Sweden at a young age described themselves as having some knowledge but still not sufficient. Participants described that they were asking midwives about the contraceptives they had used in their home country, but felt that there was no room for discussing or comparing previous knowledge about contraceptives at the contraceptive counselling meeting.

“I feel there is a difference … In the beginning I asked my friends about the body and sexuality … I searched on the internet … . I have mostly contact with women from my home country … I realized that if I had been in school in Sweden I would have had more knowledge about these things … .” (P5)

Gaining a feeling of empowerment through knowledge

This category described participants’ sense of increased self-esteem when a trusted midwife provided information about the body and SRHR. For some of the participants, receiving knowledge during the contraceptive counselling visit about genital anatomy, the menstruation cycle and the reproductive system was a strengthening experience. The information from the midwife and her engagement about how to try to overcome fear of examinations and contraceptives were perceived as something very encouraging and empowering.

“I was very, very scared … my midwife was kind and had a lot of patience … then we talked about the exam and she was gentle … I am happy that we had this good relation and I could trust her … so I could use my contraception without fear … she helped me overcome my fear for inserting IUD … and now I dare using it and I dare to go through vaginal exam.” (P9)

Wanting outreach interactions with midwives to gain more knowledge

This category described the participants’ desire for more knowledge about where and when to see a midwife and for interactions with midwives outside the scheduled appointments. According to the participants, contraceptive counselling was usually initiated by the midwife and not by the participant, some weeks after childbirth.

“I had my baby … so they called me to come for contraceptives … for postpartum checkup … so I went … It was not my midwife … it changed … she asked me if I would like to be ‘ prevented’ … .” (P2)

If the participant was not pregnant, it was difficult to obtain knowledge about contraceptives and contraceptive counselling. The participants felt that meeting midwives in a group-oriented situation would make it easier to ask questions and would be an additional way to obtain knowledge outside the counselling arena. Apart from wanting information about contraceptives, participants expressed a specific need for more knowledge about consanguineous marriage and homosexual, bisexual, transsexual and queer (HBTQ) related questions. Participants wanted more outreach interactions with midwives about SRH.

“I believe that in Sweden midwives need to come to see us … and having meeting … talking with us … giving information … gathering all women and telling openly about these things … midwives are needed to come to our associations … before all women were scared for pap smear tests now we have been talking so much about these things … before it was haram (sin) … now everyone is taking their tests … midwives should come to our Language cafés … and inform about contraceptives … we need to know more from them.” (P12)

Stressful counselling making it difficult to choose

This category described participants’ experiences of meeting midwives who did not seem happy about their jobs, or who seemed overworked and stressed during the contraceptive counselling visit. Perceiving that there was limited time for counselling, participants felt that it was difficult to discuss different contraceptive alternatives or to ask questions and get deeper knowledge about contraceptives and anatomy. Some of the participants stated that during drop-in hours, when a lot of people are waiting for their turn, both they and the midwives were feeling stressed. After the stressful counselling, when the midwife asked them to choose a contraceptive method, it was difficult to make a decision.

“Every time you go … you see a new midwife … . So you just meet and the midwife is telling me you can choose this and this … but I cannot choose or decide which one I want … what is best for me … and so little time … so I want her to decide … I do not know if I take the right decision … how should I know … she is the expert … not me … she should know what is best for me … so I got very confused and asked my friends … .” (P4)

Preconceptions and previous experience with contraceptives needing due consideration

The theme “Preconceptions and previous experience with contraceptives needing due consideration” described how the participants brought to the contraceptive counselling meeting their own individual preconceptions, different knowledge levels and previous experiences of contraceptives. The participants considered preconceptions and previous experiences to be essential when expressing contraceptive preferences, but these could not be discussed unless trust was established with the midwife.

Specific contraceptive preferences based on previous experiences

This category described how effectiveness and choice of contraceptives were based on feelings of physical and psychological satisfaction with previous choices. This feeling of effectiveness was according to the participants not always based on factual knowledge, but rather based on what they themselves perceived as effective and not harmful to them and to their husband. If the participants had experienced side effects from a contraceptive method they had been offered, they did not return for counselling unless they had a trustful relationship with their provider, the midwife. All participants described having used condoms and had good knowledge about them, as well as methods such as coitus interruptus and safe periods, which were, according to the participant’s methods as commonly used as condoms. The participants stated that these methods were well known to them even when knowledge about any other method was lacking. The cost of contraceptives was, according to the participants, secondary in relation to the feeling of effectiveness and sense of well-being. According to the participants, condoms were never bought by women, only by men, and often it was the men who preferred using the condom.

“ … I feel it is better with condom … and my husband also like condom … so we found this method … I did not ask my midwife.” (P15)

Ideas about menstruation as an aspect of health dominating choice of contraceptives

This category included other factors that participants could not ignore, such as the desire for having regular menstrual periods, and fear of hormones. The participants stated that many women regarded menstruation as an indicator of good health and were afraid of contraceptives that would make them bleed too much or too little or not at all. According to the participants, it was important to have the opportunity to try different methods and to evaluate them with a supportive midwife. When they found a satisfactory contraception method, they could more easily disregard previous requirements, such as the importance of bleeding.

“For many women it is important not to bleed too much … many women believe bleeding is for health … for fertility … for example there is women having new contraceptive and bleeding 15 days in one month … and then they stop using it … not knowing why bleeding so much … and then she does not trust to try any other contraceptive.” (P13)

Myths and misconceptions being shared as knowledge among family and friends

This category described how the participants were influenced by their social context regarding contraceptives. Common myths and misconceptions about contraceptives were that contraceptives made one unable ever to have children or unable to have sex, IUDs damaged virginity or disappeared into the body, infections such as HIV were transmitted through contraceptives, and hormones caused irreversible damage to the body. According to the participants, these myths and misconceptions, combined with experiences of contraceptives of poor quality from their home countries or experiences of side effects, contributed to increase fear of contraceptives. The participants found it difficult to ignore these myths and misconceptions since friends and family were trusted as advisors in life in general. The participants emphasised that it was important to be able to discuss their fears of contraceptives with the midwife during contraception counselling. The participants stated that if they did not feel the midwife understood their fear or did not take it seriously, they did not return for a new counselling appointment.

“You know … the view of contraceptives is very bad … people telling you that you will be fat … you will be infertile if you use contraceptives … the attitude towards contraceptives is as something being very bad and harmful … when I tell my family and friends in my home country that I am using pills they are upset … telling me to stop … telling me I will have problems … and then I say I have talked to my midwife … but they tell me do not trust her … she don’t know … .” (P19)

Contraceptive counselling – an interplay between women’s and midwives’ views of each other

The theme “Contraceptive counselling – an interplay between women's and midwives’ views of each other” described participants’ feelings of being different from the midwife in Sweden. They perceived a feeling of “we and them” as an unseen barrier in their relationship with the midwife, and perceived that there were differences between them concerning “when and why” to use contraceptives and general attitudes towards sexuality and SRHR.

Fear of being judged by the midwife and the society

This category described participants’ concerns about being accepted by the midwife, not knowing if she was judgmental or not. The participants stated that women having sex before marriage or using contraceptives without being married were often judged by their own families and described as being promiscuous. Their chances of getting married were then severely decreased. The consequences for the girl or the woman can be fatal, according to the participants. Coming from countries with different attitudes towards contraception use, the participants stated that they were afraid of telling the midwife about their perceived differences between Sweden and their home country, fearing that they then risked being judged by her. According to the participants, if they felt judged, it was very likely that they did not see a midwife again and then the possibility of getting contraceptives was lost. The participants described successful contraceptive counselling as a meeting grounded in a mutual understanding of one another's views of sexual norms, as well as when to see a midwife for contraceptive counselling. Such a mutual understanding was essential for being able to establish a non-judgmental trustful relationship.

“Sometimes I believe midwives are thinking contraceptives are being something forbidden to us … having own perceptions about us coming from other countries … but they should just ask … sometimes I have the feeling that they don’t believe we will take the medicine anyway.” (P18)

Importance of virginity and family honour for the woman and for the midwife

This category described participants’ views about the difficulties associated with being a young woman and not being married. The participants, regardless of age or marital status, were fearful about parents getting to know that unmarried women were seeing a midwife, because they would assume that such women were thinking of having sex. Female virginity was an important issue, according to all participants. Vaginal exams were described as a taboo for an unmarried girl. Women and girls were, according to the participants, sent to medical doctors for checking if they were virgins before marriage. Factual knowledge about the hymen and virginity was regarded as poor by the participants. Swedish secondary schools and educational programmes for newly arrived adults provide sex education as part of the curriculum, but participants felt that this was not enough. The participants emphasised the importance of midwives having knowledge about the importance of virginity and that the consequences of not being a virgin before marriage could be serious for the girl. Furthermore, midwives needed to dare to ask girls and women questions about virginity and its personal importance for them, so that there could be a dialogue. According to the participants, the midwives must have this knowledge so that the girls and women coming to see them can have a feeling of being understood and gain trust in the midwife.

“People are scared that you will lose your virginity if you go for a gynecology exam … then they are telling us at the gynecology clinic that they can repair the virginity … but how does that work … how do I know that it is done … I am not sure how you lose your virginity … is it when you have intercourse? … In our countries it is however not well seen that a unmarried girl should look for contraceptives or go through a vaginal examination … but we have to improve and take our girls to midwife or doctor if they are not feeling well … but there can be fatal consequences if they see a midwife and [also] if they don’t …” (P16)

Having many children not accepted by the midwife

This category described participants’ perception that midwives disapproved of having many children. Midwives had asked them about how many children they had and how many they wanted to have, in a tone that made them feel that it was not allowed to have many children. They felt questioned by the midwife for wanting many children and whether it was their own choice or if it was their husband's choice. According to the participants, some of them had experienced being at the hospital giving birth and the midwife was asking if this was the last baby. However, when midwives encouraged them to take care of their bodies and to have time spacing between the children by using contraceptives so that the body is able to recover, the participants felt cared about and seen. The participants wanted to learn about how to take better care of themselves, saying they were not aware of the risks the midwives were telling them about that were associated with going through many pregnancies.

“Once I was visiting midwife and she told me to close down (to get sterilized) … you know … telling me it is good to have a break between the children … to not have too many children … I was very tired … I felt no contraceptive was right for me … but I never wanted to do that … then she asked me if it is my husband who wants to have more children … but I wanted to have more children … my son was asking for a little brother … and how can I decide … God decide … I love my children and my family … it feels like in Sweden I am not allowed to have many children.” (P6)

Discussion

This study's aim was to explore immigrant women's perspectives on contraceptive counselling provided by midwives in Sweden. Trust was described as the overall important factor that could not be ignored in contraceptive counselling between the woman and the midwife. The need for trust concerned different perspectives, such as trusting the Swedish healthcare system, the midwife, and the interpreter, as well as the woman's own trust in herself and her knowledge.

Sweden, a secularised country, is today a globalised country hosting more people with different beliefs and approaches to SRH than ever before.49 The participants in this current study described a feeling of fear and mistrust towards the midwife and the Swedish healthcare system, and not knowing if the midwife or what she presented and represented, could be trusted. People’s general level of trust is important and has a significant impact on their health and their feelings of being an equal part of society.50 Findings emphasising the importance of trust are presented in the report from the Commission for a Socially Sustainable Malmö which is included in the city of Malmö’s further work with the Sustainable Development Goals and Agenda 2030.51,52

It was not obvious to the participants that a midwife could be the main provider for contraceptive counselling. Immigrants’ mistrust of nurses with specialist competencies within the Swedish healthcare system has previously been described by Nkulu et al.53 The professional role of Swedish midwives and their formal competence, including contraceptive counselling, needs therefore to be highlighted to immigrants coming to Sweden.

Communication challenges arose, not only when discussing intimate matters with an unknown midwife, but also when including an interpreter. Trust in the interpreter as a professional is an essential factor together with shared linguistic background and gender for successful interpretation.54 In the present study, the participants sometimes preferred to use husbands, friends, or relatives as interpreters rather than to reveal something private and personal through a professional interpreter. The use of family members as interpreters is not uncomplicated and does not guarantee equal health care,55 as stipulated by Swedish law.56 Currently, there is a lack of female, well-educated medical interpreters in Malmö and in Sweden in general, which might explain the perceived unsatisfactory quality of interpretation by the participants in this present study.57

Increased levels of trust are generally associated with increased levels of knowledge and education.49 All participants in this current study stated that they had too little knowledge and wanted to know more about contraceptives and SRH. This is a positive aspect that should not be ignored since improved health literacy is highlighted as one of the most important factors for having good SRH and thereby health in general.58 Furthermore, midwives need to raise their awareness and become more “health literate” to be able to meet, to communicate and to understand the needs of immigrant women with lower health literacy levels.59 In Sweden today, civic mediators are building sexual health literacy among newly arrived immigrants and cultural doulas have been successfully educated, building bridges between migrant women and the Swedish healthcare system.60,61 However, the participants asked for more knowledge and education from midwives as a trusted profession, which indicates that midwives as a profession can be useful outside the traditional healthcare setting. This is in accordance with a recent review by Fair et al.14 who describes the importance of “finding the way through the system” for maternal healthcare providers and to think in untraditional ways in order to meet the information needs of migrant women experiencing maternity care in European settings.

Today, contraceptive counselling postpartum is usually provided in one-on-one encounters and, according to our findings, often on the initiative of the midwife rather than the woman herself. A Swedish study found that about 30% of all women in Sweden do not attend the scheduled postpartum visits 8 weeks after giving birth, which significantly increases the risks for unintended pregnancies.62 Midwives in Sweden working with immigrant women report how they develop their own transcultural provider strategies to adapt the counselling in relation to immigrant women’s knowledge and language level and to when they actually come for other visits, i.e. “catch her when you can”.26,63 Previous studies suggest that providing and offering contraceptive counselling in other reproductive health contexts, for example, during prenatal care and/or post-natal care, is beneficial for women with lower educational levels and women with less knowledge about contraceptives in general.64–66

The participants in our study stated that they wanted knowledge to be provided by midwives in an outreach setting in addition to the individual counselling session. Previous research found that midwives working in immigrant areas providing contraceptive counselling felt that outreach work is necessary and that the midwives need to be more visible/available in the society.63 Furthermore, outreach work would strengthen immigrant women's general knowledge about the midwife's professional role, in line with the needs indicated by our findings. Further studies are needed to develop and evaluate outreach efforts by midwives in immigrant areas. Generally, a more flexible approach as to when and where to provide contraception counselling would give women more time to discuss alternatives, more time for contemplation of choice of contraceptive methods and increased health literacy.59,63,64

According to the European TANCO study,67 providers of contraception counselling generally underestimate women’s interest in information regarding different contraceptive methods. A wish for deeper discussions about contraceptives was expressed by the participants. However, having too much information and too many choices was described by the participants as being overwhelming when not having enough knowledge. Dehlendorf et al. state that women who are experiencing the process of shared decision-making are more content with their choice of method.68 The participants stated that shared decision-making and shared responsibility would have helped them, instead of receiving a lot of information about contraceptives and then being left to make the choice on their own. At the same time, the counselling was often experienced as too stressful and “it was not my midwife”. Sandall et al. found that continuity of care, i.e. meeting the same midwife, significantly increased women’s health, reducing maternal and child mortality.69 Continuity of care where women are meeting the same midwife is best practice but is not implemented in Sweden.70

Hellström et al.12 found that a large proportion of women in Sweden are using less effective contraceptive methods and overestimate their effectiveness despite easy access to contraception counselling and subsidised contraceptives. Factors such as low educational level, poor social networks, unemployment and being outside common pathways to health care have been reported as possible reasons for some women using less effective contraceptives and consequently having a higher percentage of unintended pregnancies,27 aspects which may also have influenced the present study participants. Furthermore, in line with our research findings, fear of side effects, fear of hormones and misconceptions related to contraceptives contribute to why women in general are avoiding the use of modern contraceptives30,71–73.

The promotion of the most effective contraceptive methods by policy makers and healthcare providers in order to achieve the SDG goals of reducing pregnancies and abortions has been criticised by Senderowicz, among others, for its lack of a patient-centred approach.31 Consequently, women are facing a choice-less choice and losing their contraceptive autonomy, where the choice of non-use might be acceptable as well.31 The participants stated that they felt that having many children was not accepted by the midwife. Effectiveness in family planning programmes is usually measured through indicators of the total fertility rate, contraceptive prevalence rate and unmet need for contraception.31 However, none of these indicators are measuring women’s health, quality of care, access to contraceptives, or reproductive rights.31 From the provider perspective, effectiveness is measured through use of modern contraceptives which are seen as mostly beneficial for women and for avoiding unintended pregnancies.74 In this present study the effectiveness of contraceptives was viewed by the participants as good, regardless of which method they used, when they felt it was a choice of their own and in line with their current needs. To understand women’s needs and why they are not using contraceptives, the definition and measurement of unmet needs would benefit from being divided into two aspects: the demand side (lack of desire to use contraception) and a supply side (lack of access to contraception).75 In Sweden there is free access to contraceptive counselling and modern contraceptive methods are subsidised, yet national surveys suggest there has been a rise in unmet needs. The concept of full choice, described as the perception of access to family planning services, applies only when the woman herself perceives that she has access to family planning services.31 Therefore, to reach a more person-centred understanding of contraceptive need and unmet need, the understanding of a woman's demand for using contraceptives must be disaggregated from the perspective of access to contraceptives.75

The participants in this present study described how they felt that they had less knowledge than Swedish women, that they did not have time to discuss previous experiences of contraceptives during the contraceptive counselling and that midwives did not seem to want to hear about contraceptives previously used in the home country. Furthermore, the trusted relationship with the midwife was a key factor for returning for counselling. In order to prevent losing previous users who were not happy with their choice of contraceptives, also described as the “leaking bucket” effect by Jain,76 providers or midwives need to explore women’s previous experiences of contraceptives and their beliefs about contraceptives before continuing to provide information. Discontinuation of contraceptives can depend on several aspects, e.g. experienced side effects, lack of accurate information or a wish for pregnancy.73,76 Furthermore, women who are using long-acting reproductive contraceptives are dependent on the provider for removing the contraceptive of choice, which can be another barrier affecting their use of contraceptives and feelings of reproductive autonomy.75 According to our present study findings and in accordance with the concept of contraceptive autonomy,31 there is a need for the midwife to understand the entire life context of the woman and to allow room for her to share her life perspective in relation to contraceptive use or non-use. Informed choice in order to attain contraceptive autonomy means to receive balanced information about different methods and side effects, and information about knowing what to do in case of side effects, including being told about removal and permanence.31

Men’s opinions and experiences regarding contraceptives were also present in the contraception counselling room even if they were not always there in person, which is in line with previous research regarding immigrant women and abortion care in Sweden.77 Previous research shows that men’s educational level, concern about contraceptive methods, personal feelings and attitudes towards contraception and abortion are affecting women’s access to contraceptives.78 Immigrant women who are coming from societies with mostly patriarchal structures and moving to Sweden can experience personal conflicts due to different gender perspectives, both in society in general and, with time, also within family life and in relation to family planning.79,80 Depending on the husband's attitude to contraceptives, the decision about use of contraceptives often cannot be made without the consent of the husband.20,81 According to Upadhyay et al., gender inequalities increase women’s vulnerabilities through male-dominated decision-making and economic and educational disparities.78 Midwives providing contraceptive counselling based on the contraceptive autonomy framework31 need therefore to navigate together with the woman, providing women-centred care to help her to uphold her autonomy and express her free will regarding contraception. The participants described a feeling of increased self-esteem and empowerment when gaining more knowledge about contraceptives and SRH from the midwife. Women’s empowerment and the ability to make strategic life choices are considered to be key factors for family planning and optimal reproductive health outcomes.82 However, global research on family planning shows that male involvement is needed for improving women’s abilities to use contraception.7 Nevertheless, the question remains as to how midwives can provide and enhance contraceptive autonomy for women who are accompanied by their husbands, without compromising the woman's best interests and her rights. More research on why men accompany their partner for contraceptive counselling and how midwives can provide best contraceptive counselling in the husbands’s presence is needed.

Globally, cultural and religious norms are factors that are affecting women’s abilities to use contraceptives, as also shown in our findings.83 Recent Swedish research reports regarding SRHR and immigrants49,84,85 found that non-European immigrant men and women in Sweden had generally different attitudes and norms for when and what kind of contraceptives to use compared to their Swedish counterparts, which is in line with our findings in this sample of non-European immigrants. The countries represented and the age of participants are in line with the young, diverse population in Malmö. Distance between the individual’s and society’s norms and values can lead to a feeling of alienation, unequal treatment and unequal access to health care.49,77 The participants in the current study felt that midwives needed to be aware of the potentially serious social consequences for young, unmarried women visiting midwives for contraceptive counselling. This is in line with previous research studies where Alizadeh et al.86 and Kolak et al.63 found that a trustful relation with the midwife could play a key role in preventing the repercussions caused by honour-related problems that are still present in Swedish society. Midwives working in immigrant-dense areas develop their own strategies for how to meet women with honour-related questions.63 Furthermore, to combat misogynist practices such as virginity control and hymen “reconstructions”, these issues need to be raised at micro and macro levels to uphold women’s rights and empower women.38

Our findings suggest that changes in the current system of contraceptive counselling in Sweden are needed in order to establish the trustful relationship with the midwife that immigrant women regard as essential. Immigrant women need to receive better information about the central role of the midwife in the Swedish system. Midwives need orientation in cultural differences to develop their empathy and to better understand the range of factors influencing immigrant women's contraceptive choices, including health literacy. Outreach activities whereby midwives can meet immigrant women in informal venues could help to establish the mutual understanding upon which trust is based. The caseload of midwives should not be too high so that midwives have sufficient time per client during the counselling session. Finally, an important priority would be ensuring continuity of care, so that women can meet the same midwife throughout various care needs. Moreover, midwives need to be aware that by providing contraceptive counselling, they have a unique opportunity to improve women’s SRHR.

Methodological considerations

Several aspects contributed to enhance the trustworthiness of the study. The purposive sampling method provided a heterogeneous group of participants with different backgrounds reflecting the variation and the non-European background of the immigrant population in Malmö, thereby strengthening the credibility of the study. Interviews are, however, often assymetrical in terms of the power dynamics between the interviewer and the participant.87 The participants in this present study were informed that the interviewer is a midwife by profession, which may have created a willingness to share information and experiences. However, the same information could have created a sense of limitation and mistrust. Although the use of an interpreter during the interviews was offered, all participants chose to decline. Therefore, it cannot be excluded that if the participants were speaking their “own” language, other information and nuances concerning the research topic could have emerged. Furthermore, it cannot be excluded that immigrant women who were not included in the sampling strategy, such as those with language barriers and/or with no contact with immigrant associations, would have different views and experiences and thereby would have contributed to other perspectives. The time frame of 10 years could have been a limitation for the participants’ ability to remember and thereby describe what they had experienced. The dependability of the study was strengthened by using a thematic interview guide based on the research topic and aim of the study. The interview data presented a shared view of contraceptive counselling regardless of the participants’ different origins and cultural backgrounds. Throughout the analytical process, no data were left out or difficult to sort, thereby strengthening the credibility of the findings. Furthermore, a detailed description of the methodology and analysis enhances the study’s confirmability. All authors have previous experience in the field of SRH, which enhanced their individual and collective pre-understanding of the research subject and enhanced the credibility of the study. Although the interviewer (first author) is not an immigrant, she has foreign-born parents, which may have facilitated a better understanding of cultural differences and the establishment of a conducive interview climate. Transferability of the findings to similar settings in Sweden is deemed to be good; however, it is not known to what extent the findings might be transferable to midwife counselling in other countries.

Conclusion

Although immigrant women want more knowledge about contraception, a trustful relationship with the midwife is needed to be able to make informed contraceptive choices. Midwives may need increased awareness of the many factors influencing immigrant women's choices to ensure women’s contraceptive autonomy. Policy changes that promote new ways of counselling and the ability to provide continuous care are needed.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Region Skåne, Vårdakademin.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- 1.United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) . Five reasons migration is a feminist issue. 2018, updated 09 April. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/news/five-reasons-migration-feminist-issue

- 2.Inci MG, Kutschke N, Nasser S, et al. Unmet family planning needs among female refugees and asylum seekers in Germany – is free access to family planning services enough? Results of a cross-sectional study. Reprod Health. 2020;17(1):115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Downe S, Finlayson K, Oladapo OT, et al. What matters to women during childbirth: a systematic qualitative review. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0194906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cottingham J, Germain A, Hunt P.. Use of human rights to meet the unmet need for family planning. Lancet. 2012;380(9837):172–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glenngård AH, Hjalte F, Svensson M, et al. Health systems in transition: Sweden. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe on behalf of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2005.

- 6.Alkema L, Kantorova V, Menozzi C, et al. National, regional, and global rates and trends in contraceptive prevalence and unmet need for family planning between 1990 and 2015: a systematic and comprehensive analysis. The Lancet. 2013;381(9878):1642–1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Starrs AM, Ezeh AC, Barker G, et al. Accelerate progress – sexual and reproductive health and rights for all: report of the Guttmacher– Lancet Commission. The Lancet. 2018;391(10140):2642–2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.UNFPA . Protect women and girls on the move. 2018, Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/news/call-protect-women-and-girls-move

- 9.IOM glossary [Internet] . 2019. Available from: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/iml_34_glossary.pdf

- 10.Mcauliffe M, Triandafyllidou A, editors. World migration report 2022. Geneva: International Organization for Migration (IOM); 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization . Report on the health of refugees and migrants in the WHO European Region: No public health without refugee and migrant health. Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 2018; Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311347/9789289053846-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Google Scholar]

- 12.SCB, Foreign-born persons in Sweden by country of birth, age and sex. [Internet] . 2021. Available from: http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/

- 13.Foreign-born persons in Sweden by country of birth, age and sex . Available from: http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/

- 14.Fair F, Raben L, Watson H, et al. Migrant women’s experiences of pregnancy, childbirth and maternity care in European countries: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2020;15(2):e0228378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Candeias P, Alarcão V, Stefanovska-Petkovska M, et al. Reducing sexual and reproductive health inequities between natives and migrants: a Delphi Consensus for sustainable cross-cultural healthcare pathways. Front Public Health. 2021;9:656454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO . Regional Office for Europe. Copenhagen. Improving the health care of pregnant refugee and migrant women and newborn children Technical guidance.2018. Available from: https://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/abstracts/improving-the-health-care-of-pregnant-refugee-and-migrant-women-and-newborn-children-2018Copenhagen

- 17.Ostrach B. “Yo no sabía … ”-immigrant women’s use of national health systems for reproductive and abortion care. J Immigr Minor Health. 2013;15(2):262–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kopp Kallner H, Thunell L, Brynhildsen J, et al. Use of contraception and attitudes towards contraceptive use in Swedish women – a nationwide survey. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0125990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sudbury H, Robinson DA.. Barriers to sexual and reproductive health care for refugee and asylum-seeking women. Br J Midwifery. 2016;24(4):275–281. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Otero-Garcia L, Goicolea I, Gea-Sanchez M, et al. Access to and use of sexual and reproductive health services provided by midwives among rural immigrant women in Spain: midwives’ perspectives. Glob Health Action. 2013;6:22645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rasch V, Gammeltoft T, Knudsen LB, et al. Induced abortion in Denmark: effect of socio-economic situation and country of birth. Eur J Public Health. 2007;18(2):144–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaisanen H, Koponen P, Gissler M, et al. Contraceptive use among migrant women with a history of induced abortion in Finland. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care: The Official Journal of the European Society of Contraception. 2018;23(4):274–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Omland G, Ruths S, Diaz E.. Use of hormonal contraceptives among immigrant and native women in Norway: data from the Norwegian prescription database. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;121(10):1221–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poncet LC, Huang N, Rei W, et al. Contraceptive use and method among immigrant women in France: relationship with socioeconomic status. Eur J Contracep Reprod Health Care: The Official Journal of the European Society of Contraception. 2013;18(6):468–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare . Midwives license and right to prescribe 1996 cited SOSFS 1996:21. Available from: https://legitimation.socialstyrelsen.se/andra-behorigheter/forskrivningsratt/forskrivningsratt-for-barnmorska/

- 26.Wätterbjörk I, Häggström-Nordin E, Hägglund D.. Provider strategies for contraceptive counselling among Swedish midwives. Br J Midwifery. 2011;19(5):296–301. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Skåne R. Regional riktlinje för antikonception [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://vardgivare.skane.se/siteassets/1.-vardriktlinjer/regionala-riktlinjer—fillistning/regional-riktlinje-for-antikonception-2019-02-13.pdf

- 28.Barnmorskeförbundet S. Kompetensbeskrivning for legitimerad barnmorska 2019 2019. Available from: https://storage.googleapis.com/barnmorskeforbundet-se/uploads/2020/04/Kompetensbeskrivning-for-legitimerad-barnmorska.pdf

- 29.Lindgren H, Bogren M, Osika Friberg I, et al. The midwife’s role in achieving the sustainable development goals: protect and invest together – the Swedish example. Glob Health Action. 2022;15(1):2051222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hellström A, Gemzell Danielsson K, Kopp Kallner H.. Trends in use and attitudes towards contraception in Sweden: results of a nationwide survey. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2019;24(2):154–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Senderowicz L. Contraceptive autonomy: conceptions and measurement of a novel family planning indicator. Stud Fam Plann. 2020;51(2):161–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Envall N, Emtell Iwarsson K, Bizjak I, et al. Evaluation of satisfaction with a model of structured contraceptive counseling: results from the LOWE trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100(11):2044–2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iwarsson KE, Larsson EC, Gemzell-Danielsson K, et al. Contraceptive use among migrant, second-generation migrant and non-migrant women seeking abortion care: a descriptive cross-sectional study conducted in Sweden. BMJ Sexual Reprod Health. 2019;45(2):118–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindh I, Skjeldestad FE, Gemzell-Danielsson K, et al. Contraceptive use in the Nordic countries. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96(1):19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hognert H, Skjeldestad FE, Gemzell-Danielsson K, et al. High birth rates despite easy access to contraception and abortion: a cross-sectional study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96(12):1414–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.United Nations Population Fund, UNFPA (2019) . Sexual and reproductive health and rights: an essential element of unviersal health coverage Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/SRHR_an_essential_element_of_UHC_SupplementAndUniversalAccess_27-online.pdf

- 37.Regeringskansliet . The Swedish foreign service action plan for feminist foreign policy 2019–2022, including direction and measures for 2020. [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://www.government.se/499195/contentassets/2b694599415943ebb466af0f838da1fc/the-swedish-foreign-service-action-plan-for-feminist-foreign-policy-20192022-including-direction-and-measures-for-2020.pdf

- 38.Christianson M, Eriksson C.. Promoting women’s human rights: A qualitative analysis of midwives’ perceptions about virginity control and hymen “reconstruction”. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care: The Official Journal of the European Society of Contraception. 2015;20(3):181–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walsh D. Midwives, gender equality and feminism. Pract Midwife. 2016;19(3):24–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.World Health O . Sexual health, human rights and the law. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller S, Abalos E, Chamillard M, et al. Beyond too little, too late and too much, too soon: a pathway towards evidence-based, respectful maternity care worldwide. The Lancet. 2016;388(10056):2176–2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scamell M, Alaszewski A.. Fateful moments and the categorisation of risk: midwifery practice and the ever-narrowing window of normality during childbirth. Health Risk Soc. 2012;14(2):207–221. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Akhavan S. Midwives’ views on factors that contribute to health care inequalities among immigrants in Sweden: a qualitative study. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11(1):47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dahlgren L, Emmelin M, Winkvist A.. Qualitative methodology for international public health. 2nd ed. Umeå: Epidemiology and Public Health Sciences, Department of Public Health and Clinical Medicine, Umeå University; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stad M. Fakta och befolkning2021. Available from: https://malmo.se/Fakta-och-statistik/Befolkning.html

- 46.Righard E, Öberg K. The governance and local integration of migrants and Europe’s refugees (GLIMER)2018. Available from: http://www.glimer.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Combined-Report.pdf

- 47.Graneheim UH, Lundman B.. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lindgren B-M, Lundman B, Graneheim UH.. Abstraction and interpretation during the qualitative content analysis process. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;108:103632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Puranen B. World Value Survey. Med migranternas röst2019 Available from: https://www.iffs.se/publikationer/iffs-rapporter/med-migranternas-rost/

- 50.Wollebæk D, Lundåsen SW, Trägårdh L.. Three forms of interpersonal trust: evidence from Swedish municipalities. Scan Polit Stud. 2012;35(4):319–346. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stad M. Malmös path towards a sustainable future. Health, welfare and justice. Commission for a Socially Sustainable Malmö2013 Available from: https://malmo.se/download/18.6c44cd5c1728328333211d32/1593519743583/malmo%CC%88kommisionen_rapport_engelsk_web.pdf

- 52.Stad M. Agenda 2030 i Malmö2021 Available from: https://malmo.se/Sa-arbetar-vi-med … /Hallbar-utveckling/Agenda-2030-i-Malmo.html

- 53.Kalengayi FN, Hurtig AK, Ahlm C, et al. “It is a challenge to do it the right way”: an interpretive description of caregivers’ experiences in caring for migrant patients in northern Sweden. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krupic F, Hellström M, Biscevic M, et al. Difficulties in using interpreters in clinical encounters as experienced by immigrants living in Sweden. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(11-12):1721–1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hadziabdic E, Albin B, Heikkilä K, et al. Family members’ experiences of the use of interpreters in healthcare. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2014;15(2):156–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.SFS . 1982:763 Hälso- och sjukvårdslagen [Swedish Health Care Act], HSL. Stockholm. Socialdepartementet. [cited SFS 1982:763. Hälso- och sjukvårdslagen [Swedish Health Care Act], HSL.

- 57.Skåne R. Kunskapscentrum migration och hälsa Malmö. Språktolkning inom hälsooch sjukvård– en fråga om mänskliga rättigheter 2019.

- 58.Wångdahl J, Lytsy P, Mårtensson L, et al. Health literacy among refugees in Sweden – a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Asplund RA. Iris Luthman ochSara Thalberg (redaktörer). Migranters möte med svensk hälso- och sjukvård, Avhandlingsnytt 2020:7. Migrants’ encounters with Swedish health care, Dissertation Series 2020:7. 2020.

- 60.Akhavan S, Edge D.. Foreign-born women’s experiences of community-based doulas in Sweden – a qualitative study. Health Care Women Int. 2012;33(9):833–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Svensson P, Asamoah BO, Agardh A.. Facilitating an encounter with a new sexuality discourse: the role of civic communicators in building sexual health literacy among newly arrived migrants. Cult Health Sex. 2021: 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liljeblad KL, Kallner HK, Brynhildsen J.. Risk of abortion within 1–2 years after childbirth in relation to contraceptive choice: a retrospective cohort study. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2020;25(2):141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kolak M, Jensen C, Johansson M.. Midwives’ experiences of providing contraception counselling to immigrant women. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2017;12:100–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]