Abstract

Hospital readmission is a key metric of hospital quality, such as for comparing Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals to private sector hospitals. To calculate readmission rates, one must first identify individual hospitalizations. However, in the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), data are organized by “bedded stays,” that is, any stay in a healthcare facility where a patient is provided a bed, not hospitalizations. Thus, CDW data poses several challenges to identifying hospitalizations including: (1) bedded stays include both non-acute inpatient stays (i.e. nursing home, mental health) and acute inpatient hospital care; (2) transfers between VA facilities appear as separate bedded stays; and (3) VA care may also be fragmented by non-VA care. Thus, we sought to develop a rigorous method to identify acute hospitalizations using the VA CDW. We examined all VA bedded stays with an admission date in 2009. Non-acute portions of a stay were dropped. VA to VA transfers were merged when consecutive discharge and admission dates were within one calendar day. Finally, hospitalizations that occurred in a non-VA facility were merged. The 30-day readmission rate was calculated at each step of the algorithm to demonstrate the impact. The total number of VA medical hospitalizations in 2009 with live discharges was 505,861. The 30-day readmission rate after adjusting for VA to VA transfers and incorporating non-VA care was 18.3% (95% confidence interval (CI): 18.2, 18.4%).

Keywords: Patient readmissions, United States Department of Veterans Affairs, Outcome assessment (health care), Computing methodology, Administrative data

1. Introduction

Hospital readmission rates are an oft-touted metric for evaluating the quality of care (Kocher and Adashi 2011) delivered by a health system. Readmissions are associated with substantial healthcare costs (PricewaterhouseCoopers’ Health Research Institute 2008) and disruption to patients’ lives, although many readmissions are potentially preventable (van Walraven et al. 2011). This has led to the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2016), which assesses financial penalties on hospitals with greater than expected readmission rates for select conditions (e.g. heart failure, pneumonia, acute myocardial infarction). Readmission rates are also publicly reported for many hospitals.

We reviewed prior literature to determine how hospitalizations and readmissions are identified using VA data. However, many studies of VA hospitalizations and readmissions do not report the specific tables used (Denson et al. 2016; Kheirbek et al. 2016; Axon et al. 2016), do not describe the methods used to define distinct hospitalizations (Kohn et al. 2017; Rinne et al. 2017) or do not provide the level of detail needed to independently reproduce the datasets (Nuti et al. 2016; Wong et al. 2016). Moreover, after talking to investigators at different VA facilities, we discovered that there is not a common approach by which to measure hospitalizations. To promote reproducible research methods and to facilitate comparisons across studies, we sought to describe a method for identifying hospitalizations within the VA, and use this method to measure hospital readmissions.

VA data are not organized by hospitalizations, but rather by bedded stay which is any stay in a healthcare facility where a patient is provided a bed, including hospitals and nonacute stays such as nursing facilities or mental health facilities (Table 1). Additionally, the VA not only directly provides care, but also pays for care delivered in the private sector. A Veteran may be transferred to a private hospital when a VA facility is full, or when advanced treatment (e.g. a specialty surgical or interventional procedure) is required. Thus, we aimed to develop a rigorous method that identifies acute hospital stays using the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) to measure hospital readmissions.

Table 1.

Definitions of key terms used throughout the manuscript

| Bedded stay Any stay in a healthcare facility where a patient is provided a bed, including hospital, nursing facility, mental health facility, or domiciliary for homeless Veterans |

| Specialty stay A portion of a bedded stay defined by the treating specialty. Each bedded stay is composed of one or more specialty stays |

| Acute specialty stay A specialty stay that is for an acute medical condition |

| Non-acute specialty stay A specialty stay that is not for an acute medical condition |

| Specialty transfer Patients care is transitioned from one treating specialty to another treating specialty |

| Hospitalization Consecutive acute specialty stay(s) |

2. Methods

2.1. Data

Data were utilized from the VA CDW (Federal Register: 79 FR 4377). The CDW is a national repository that contains comprehensive patient-level information across the VA, such as outpatient visits, pharmacy, labs, and vital signs. We utilized data from three tables in the Inpatient Domain (Gonsoulin 2016): (1) Inpatient, (2) Specialty Transfer, and (3) Fee-Basis.

The primary Inpatient table provides information on all bedded stays (Table 1) in a healthcare facility including hospitals, nursing facilities, mental health facilities and residential treatment facilities for homeless Veterans (referred to as domiciliaries (VA.gov, US Department of Veterans Affairs 2017) in VA). The structure of the primary Inpatient table is one row for each bedded stay within a single VA site. The Inpatient table was linked to the Specialty Transfer table, which contains one row for each specialty stay (Table 1). We classified each specialty stay as acute vs. non-acute based on treating specialty (see Supplementary material Table 5 for list of treating specialties classified as acute). Conceptually, for the purposes of this research, we considered acute specialties as those that treat an acute medical condition, as opposed to psychiatric or non-acute specialties, such as mental health, rehabilitation or nursing facilities. In addition to providing direct care to patients, the VA also serves as an insurer. Eligible Veterans may receive their care at a non-VA facility (VA Health Economics Research Center 2015). The data related to non-VA hospitalizations funded by the VA reside in the Fee-Basis domain in CDW.

2.2. Issues with defining distinct hospitalizations

Our objective was to determine the readmission rate after live discharge from a VA-funded hospitalization. To do this, we needed to identify distinct hospitalizations. There were three problems to address to accomplish this (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of data structure problems that were addressed to identify hospitalizations

| Problem 1: Identifying hospitalizations within a single VA hospital |

| VA data is organized as specialty stays nested within bedded stays. However, we are interested in hospitalizations |

| Problem 2: Hospitalizations with VA-to-VA transfer |

| Some Veterans are transferred from one VA to another. This appears as two separate hospitalizations and therefore seems like a readmission, when in fact it is one hospitalization |

| Problem 3: Hospitalizations with a VA-to-private sector or private sector-to-VA transfer |

| Some Veterans are transferred between a VA and the private sector. This appears as two separate hospitalizations, and exists in two separate datasets |

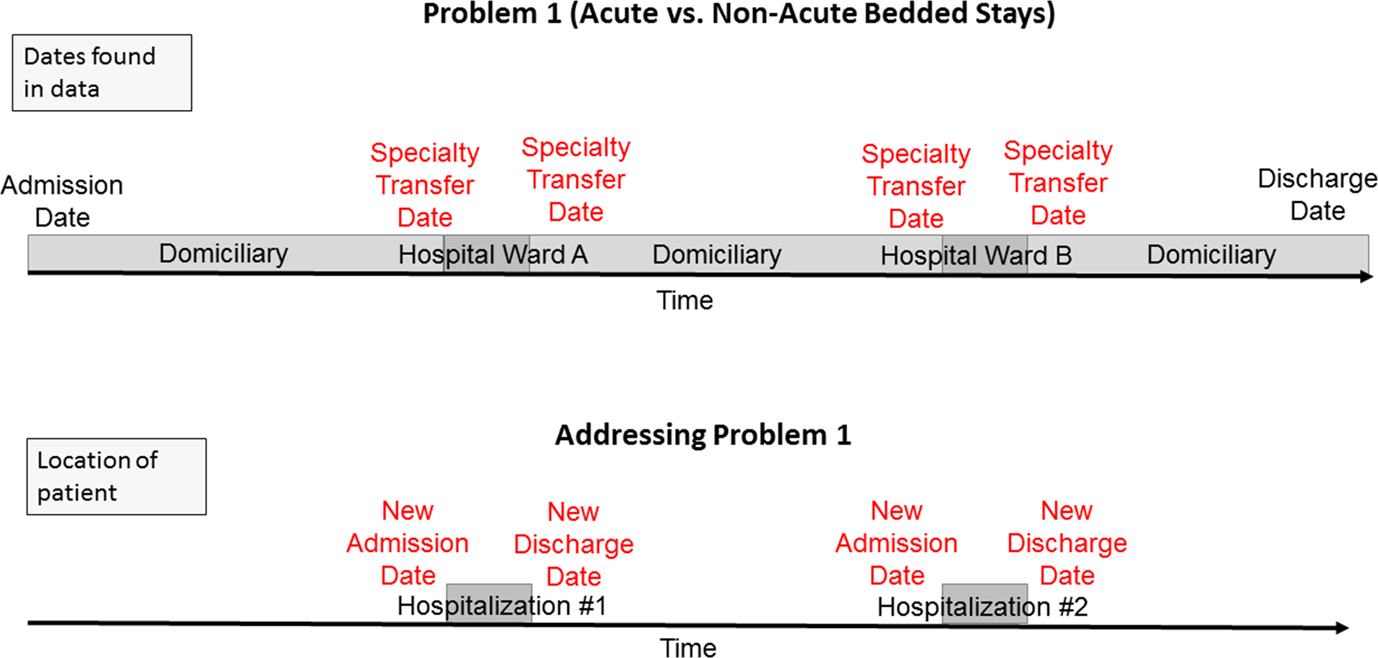

Problem 1 (Acute vs. Non-Acute Bedded Stays) was identifying acute hospitalizations within a single VA hospital from bedded stays that contain both acute and non-acute specialty stays. Figure 1 illustrates Problem 1 (Acute vs. Non-Acute Bedded Stays), whereby a patient who lived in a domiciliary within the VA presented to Hospital Ward A, returned to the domiciliary and later presented at Hospital Ward B before returning to the domiciliary. The structure of the data was a single bedded stay, with specialty stays for each of the hospital ward and domiciliary stays. However, for the purposes of determining hospital readmissions, we needed to consider each stay within the hospital ward as a distinct hospitalization and disregard the time spent in the domiciliary. Thus, rather than a single bedded stay, this scenario represents an index hospitalization (Ward A) followed by a readmission (Ward B).

Fig. 1.

Illustration of Problem 1: Acute vs. Non-Acute Specialty Stays

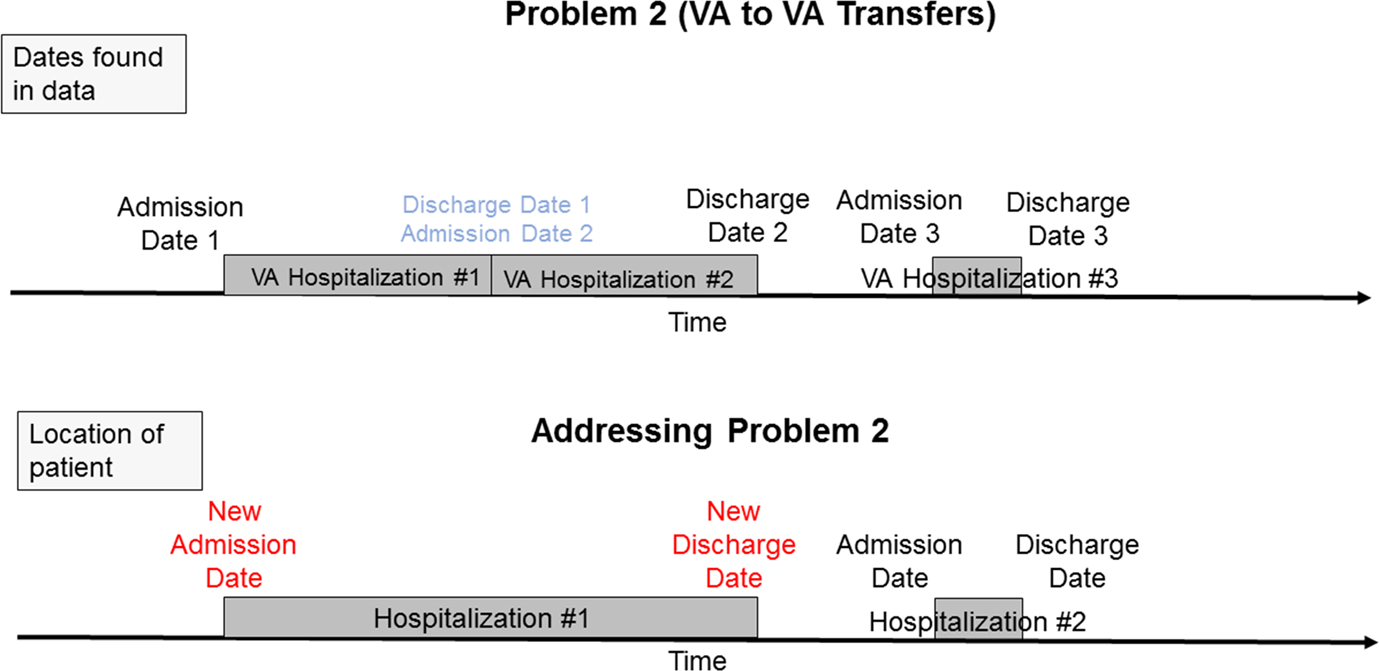

An example of Problem 2 (VA to VA Transfers) is presented in Fig. 2. A patient was transferred from one VA facility to another and had another hospitalization later in time. For transfers within the VA, patients are discharged from one facility and subsequently admitted to the next, thereby appearing as two bedded stays. However, in the context of determining readmissions, the two bedded stays should be considered a single hospitalization, while the third hospitalization was a readmission.

Fig. 2.

Illustration of Problem 2: VA to VA Transfers

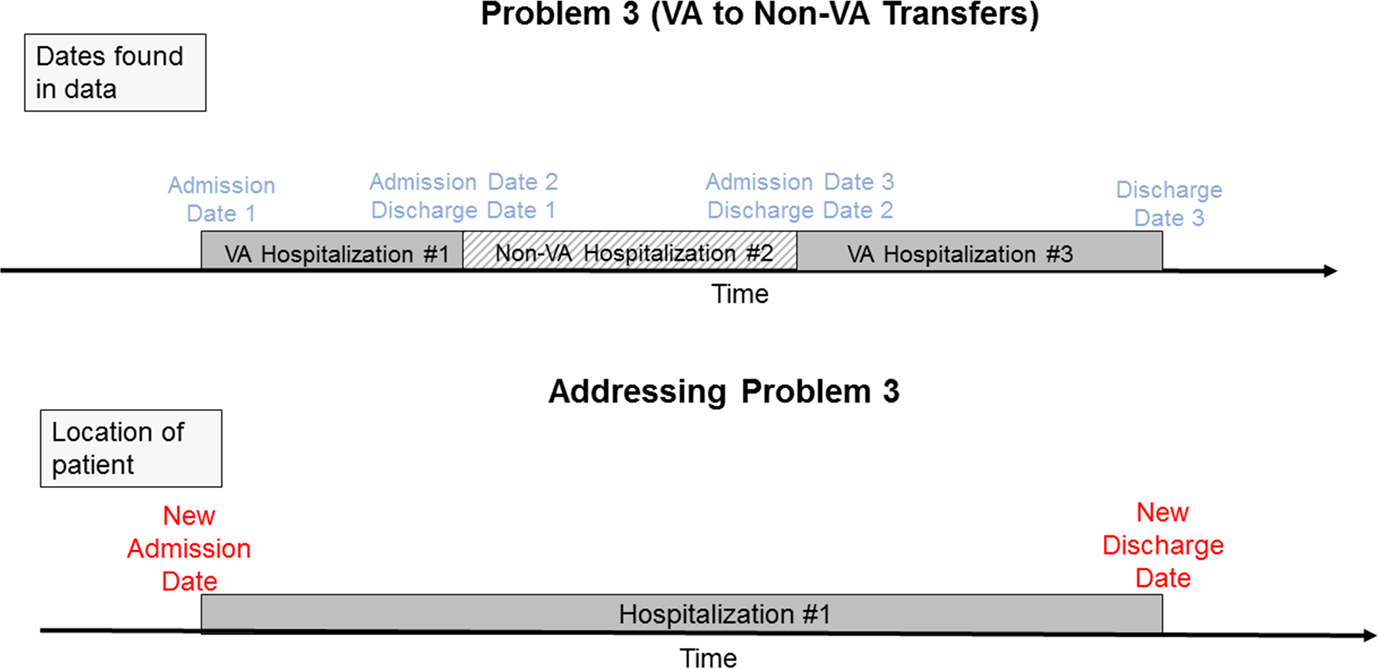

Moreover, in the case of Problem 3 (VA to Non-VA Transfers), a patient may be transferred between VA and non-VA facilities. Data for non-VA care exists in another domain (Inpatient Fee-Basis) and requires linkage to the Inpatient table. In Fig. 3, a patient was transferred from a VA facility to a non-VA facility, then back to a VA facility. Without considering the time in a non-VA facility, the second VA hospitalization appeared as a readmission, but was part of one hospitalization. The other potential impact of non-VA care is if a Veteran presented to a non-VA hospital directly, that hospitalization would not be captured without including non-VA data but may be a readmission from a previous VA hospitalization.

Fig. 3.

Illustration of Problem 3: VA to Non-VA Transfers

2.3. Approach to Problem 1 (Acute vs. Non-Acute Bedded Stays)

The procedure for determining hospitalizations within the VA is illustrated in detail in the Supplementary material. In brief, starting with the Inpatient and Specialty Transfer tables from CDW, we used all records with admission dates from 2009 (as the example year). Pre-processing was performed, in which test patients, duplicate records, and uninterpretable records (those in which the first specialty admission date differed by more than 2 days from the hospital admission date) were removed. Code specifying precisely how we implemented each pre-processing step is also in the Supplementary material.

After pre-processing, we first addressed bedded stays that were composed of just a single specialty stay. Bedded stays with a non-acute specialty stay (as defined in Supplementary material Table 5) were dropped, while bedded stays with an acute specialty stay were retained and considered hospitalizations.

We next considered bedded stays with multiple specialty stays that were all acute or all non-acute. Again, bedded stays with only non-acute specialty stays were dropped, while bedded stays with only acute specialty stays were retained and considered hospitalizations.

Finally, we considered bedded stays containing both acute and non-acute specialty stays. First, the non-acute specialty stay segments were dropped and the remaining stays were merged if there was a gap of less than 1 day. If there was a gap of one or more days between acute specialty stays, then the subsequent stay was considered a separate hospitalization. The admission and discharge dates were adjusted to reflect the acute portions of the stays.

2.4. Approach to Problem 2 (VA to VA Transfers)

After determining the acute hospitalizations within each VA facility, we linked VA to VA facility transfers. If a patient was discharged and admitted within 1 day, the second admission was classified as a hospital transfer and thus part of the same hospitalization. Otherwise, if there was more than 1 day between the discharge and subsequent admission, the second admission was considered a readmission. The admission and discharge dates were adjusted to reflect initial admission and final discharge of each newly merged hospitalization.

2.5. Approach to Problem 3 (VA to Non-VA Transfers)

We consolidated VA and non-VA hospitalizations by merging data from the Fee-Basis domain with the newly created hospitalization table. Admissions and discharges within 1 day were considered inter-hospital transfers and classified as one hospitalization, consistent with the approach used by Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Admission and discharge dates were adjusted to reflect initial admission and final discharge of each newly merged hospitalization.

2.6. Validation of the algorithm

We selected at random 100 cases to validate the algorithm against direct review of the patient chart in the electronic medical record. Specifically, we sampled 50 instances where the patient had bedded stays composed of both acute and non-acute specialty stays (Problem 1) and 50 instances of VA to VA transfers (Problem 2) to validate our algorithm. We were unable to validate the transfers to/from a non-VA hospital (Problem 3) because we did not have access to the charts for the non-VA hospitals, however conceptually this problem is identical to Problem 2 (VA to VA Transfers). An independent reviewer was provided with a date range of interest for each of the 100 cases, starting before the hospital admission and ending after hospital discharge. For each the 100 cases, the reviewer created a time-line for each patient, documenting the pertinent dates (admissions, transfer, discharge) and location (e.g. hospital, nursing home). We compared the dates of hospitalization from our algorithm to these patient time-lines. The list of 100 randomly selected patients were provided in random order, and the reviewer did not know whether the patient had nonacute stays or VA to VA transfers.

2.7. Calculating hospital readmission after a VA hospitalization

We calculated the readmission rate as the number of live discharges from a VA hospital followed by a 30-day hospital readmission divided by the number of live discharges. We considered patients who died within 1 day of discharge as an in-hospital death. We then calculated the 30-day readmission rates for each step of the algorithm: after converting bedded stays to hospitalizations, after merging VA to VA transfers, and after incorporating non-VA care. We additionally compared the 30-day readmission rates by hospital after addressing Problem 1 (Acute vs. Non-Acute Bedded Stays) and after addressing Problem 3 (VA to Non-VA Transfers). All data processing and analyses were performed using SAS 9.4.

3. Results

The total number of transfers measured at each step in our algorithm is presented in Table 3. The first column, inter-facility transfers, displays the total number of transfers that occurred, either between VA hospitals (Problem 2, VA Transfers) or between a VA and non-VA hospital (Problem 3, VA to Non-VA Transfers). We have further broken down the type of inter-facility transfers (within VA, to/from VA). In the second column, we display the total number of hospitalizations in which one or more inter-facility transfers occurred. This number is smaller than the total number of inter-facility transfers because some hospitalizations had multiple transfers. For example, a transfer from a VA facility to a non-VA facility and then back to a VA facility would be counted as two inter-facility transfers, but only one hospitalization with an inter-facility transfer.

Table 3.

Number and types of inter-facility transfers

| Inter-facility transfers | Hospitalizations (with an inter-facility transfer) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Number | 8359 | 7325 |

| VA to VA facility, N (% of total) | 6110 (73.1%) | 5345 (73.0%) |

| Non-VA to VA facility, N (% of total) | 1483 (17.7%) | 1309 (17.9%) |

| VA to non-VA facility, N (% of total) | 766 (9.2%) | 671 (9.2%) |

3.1. Addressing Problem 1 (Acute vs. Non-Acute Bedded Stays)

There were 746,267 distinct bedded stays (defined as having the same patient identifier and admission date and time) with 1,240,918 specialty stays, after pre-processing and merging the primary Inpatient table to the Specialty Transfer table. Of these 746,267 bedded stays, 475,602 (63.7%) had a single specialty stay. Of these, 179,308 (37.7%) were a non-acute specialty and 296,294 (62.3%) were an acute specialty by our classification. Bedded stays composed of a single acute specialty stay were defined as hospitalizations, while those with a single non-acute specialty stay were dropped.

We next examined the 270,665 bedded stays that contained multiple specialty stays. Of these, 255,890 (94.5%) contained all acute or all non-acute specialty stays. Again, bedded stays containing only acute specialty stays were classified as hospitalizations (n = 202,554), while those containing only non-acute specialty stays were dropped (n = 53,336).

We next examined the 14,775 bedded stays that contained both acute and non-acute specialty stays (comprised of 42,418 specialty stays). We first removed 19,447 non-acute specialty stays, and then defined consecutive acute specialty stays with a greater than 1 day gap between discharge and admission as separate hospitalizations. There were 826 acute hospitalizations identified with a greater than 1 day gap between acute specialty stays, resulting in 15,601 bedded stays in which the specialties were all acute. In total, after addressing Problem 1 (Acute vs. Non-Acute Bedded Stays), we identified 514,449 acute hospitalizations in 2009. More details of the procedure used in Problem 1 (Acute vs. NonAcute Bedded Stays) are available in the Supplementary material, Fig. 1.

3.2. Addressing Problem 2 (VA to VA Transfers)

Of the 514,449 acute hospitalizations identified after addressing Problem 1 (Acute vs. Non-Acute Bedded Stays), 522 were hospitalizations in which the Veteran was admitted to the same VA facility within 2 h of discharge from a prior hospitalization (composed of 1044 acute bedded stays identified from Problem 1 (Acute vs. Non-Acute Bedded Stays). We considered these to be erroneous discharges and merged the two records, dropping the number of hospitalizations to 513,927. Additionally, there were 5345 hospitalizations with one VA to VA transfer, and an additional 765 which had multiple VA to VA facility transfers. These 5345 hospitalizations with an inter-facility transfer was composed of 6110 distinct inter-facility transfers [affecting 11,462 hospitalizations identified after Problem 1 (Acute vs. Non-Acute Bedded Stays)]. After merging these VA to VA transfers, the final number of hospitalizations was reduced to 507,810.

3.3. Addressing Problem 3 (VA to Non-VA Transfers)

In 2009, there were 23,665 distinct non-VA hospitalizations. Of these, 14,121 (59.7%) were hospitalizations of Veterans who also had at least one VA hospitalization in 2009. We identified 2249 transfers between the VA and non-VA hospitals (composed of 4240 hospitalizations identified after Problem 2 (VA to VA Transfers). Of these, there were 1483 instances of a non-VA to VA transfer and 766 instances of a VA to non-VA transfer. The number of hospitalizations with an inter-facility transfer involving non-VA facilities was 1980 (1309 with non-VA to VA and 671 with VA to non-VA transfer). The total number of hospitalizations after including non-VA care and merging hospitalizations as necessary was 519,635, an increase of 11,825 (2.3%) after addressing Problem 3 (VA to Non-VA Transfers). The total number of transfers and hospitalizations with a transfer that occurred at each step is presented in Table 3.

3.4. Validation of algorithm

We conducted a validation for 50 patients with acute and non-acute bedded stays (Problem 1). There was one case when our algorithm detected that the patient was in a non-acute setting, but they were under observation in the ICU and possibly should have been coded as acute, although this was difficult to discern from the chart. In three cases, the progress notes for patients were generated the next calendar day, but upon inspection of these cases, we found that they were all admissions that occurred after 11:00 PM. We could find the correct calendar date when we looked at the discharge summaries for these three patients. For one patient, the chart showed that the patient moved around to several locations, but in CDW it was shown as one long stay. This did not impact our algorithm in coding the correct admission and discharge dates because each stay was acute and consecutive.

We conducted a validation of 50 charts with VA to VA transfers (Problem 2). We identified one patient with an admission date in CDW that occurred 2 days before their first specialty stay. The chart confirmed that this admission date was erroneous and our algorithm correctly recoded this. There was also an example of a patient that had their bed held at a nursing home while they were hospitalized in an acute specialty. Our algorithm correctly recoded the admission and discharge date as the time spent in the acute specialty.

3.5. Hospital readmission rates

Table 4 summarizes the total number of acute hospitalizations after each step. We included admissions that occurred during January 2010 in the calculation of the 30-day readmission rate, to ensure that hospitalizations with discharges in December 2009 were followed for the full 30 days. After defining acute hospitalizations within a single VA hospital (Problem 1), we had 514,449 acute hospitalizations, of which 501,013 (97.4%) survived to discharge. The 30-day readmission rate was 18.4% (CI: 18.3, 18.5%).

Table 4.

Hospitalizations and readmission rates after each step

| Problem 1: Acute vs. Non-Acute Bedded Stays | Problem 2: VA to VA Transfers | Problem 3: VA to Non-VA Transfers | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Total hospitalizations | 514,449 | 507,810 | 519,635 |

| Total hospitalizations, survived to discharge | 501,013 (97.4%) | 494,317 (97.3%) | 505,861 (97.3%) |

| 30-day readmission rate (95% CI) | 18.4% (18.3%, 18.5%) | 17.3% (17.2%, 17.4%) | 18.3% (18.2%, 18.4%) |

| Median length of stay, in days (IQR) | 3 (2,6) | 3 (2,6) | 3 (2,6) |

| Mean length of stay, in days (SD) | 5.1 (8.4) | 5.1 (8.4) | 5.1 (8.4) |

After adjusting for VA to VA transfers (Problem 2), there were 507,810 hospitalizations, and 494,317 (97.3%) live discharges. The 30-day readmission rate was 17.3% (CI: 17.2, 17.4%). Finally, after including non-VA care, there were 519,635 hospitalizations. Of these, 505,861 (97.3%) were live discharges. The 30-day readmission rate was 18.3% (CI: 18.2, 18.4%).

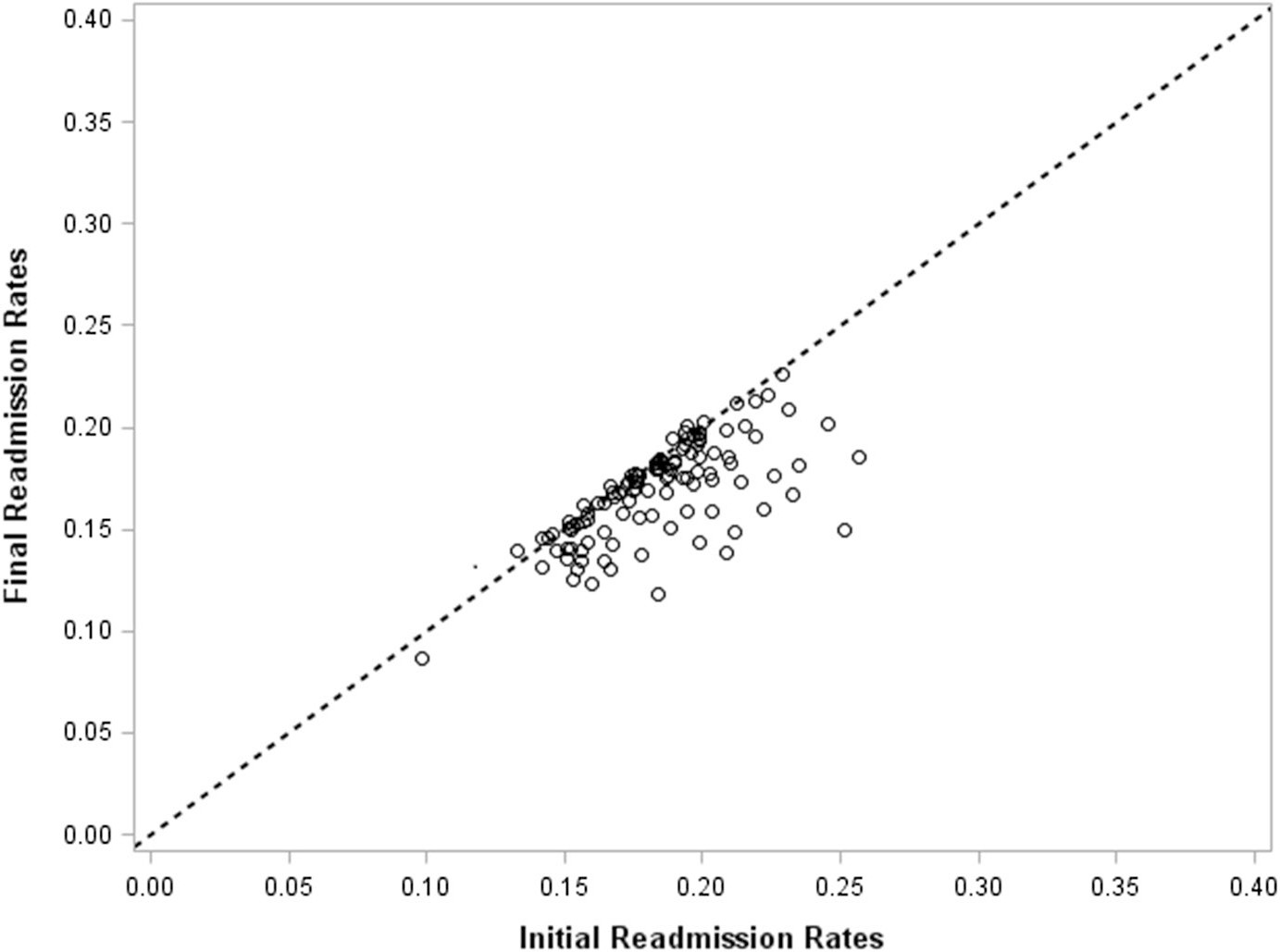

The differences in the readmission rates after each step were statistically significant. Figure 4 displays the 30-day readmission rate after addressing Problem 1 (Acute vs. NonAcute Specialty Stays) relative to the readmission rate after addressing Problem 3 (VA to Non-VA Transfers) for each hospital. The mean change in the 30-day readmission rate was 1.5 ± 2.0%.

Fig. 4.

30-day readmission rates by hospital

4. Discussion

In this paper, we present an algorithm for defining hospitalizations using VA data. This method involves removing non-acute bedded stays, merging VA to VA hospital transfers, and merging VA to non-VA hospital transfers. The inclusion of specific types of bedded stays can be amended depending on the goals of a research question. We were interested in medical or surgical readmissions after a medical or surgical hospitalization, so we excluded inpatient psychiatric care. However, other research questions may choose to include these stays. The algorithm can be easily modified depending on the goals of the research question.

We measured the number of hospitalizations, mean and median length of stay, and 30-day readmissions rates after each step of our algorithm. We also compared the hospital-specific readmission rates after addressing Problem 1 (Acute vs. Non-Acute Bedded Stays) and after addressing Problem 3 (VA to Non-VA Transfers). We find that the overall differences in readmission rates are small, but statistically significant. However, there was variability in the effect of VA to VA transfers and transfers between the VA and non-VA by hospital. In most cases, the readmission rates after Problem 1 (Acute vs. Non-Acute Bedded Stays) were higher than after accounting for VA to VA transfers and non-VA care. Thus, without addressing these problems, some hospitals may be inappropriately penalized for a high readmission rate. Accounting for non-VA care may be particularly important in longitudinal studies and studies of regional variation, since the use of non-VA care may change over time and by geographic region. We used 2009 data as an example of the potential impact of including non-VA care.

Although the overall rates of 30-day readmission were not markedly different between each step in our algorithm, much of this is attributed to the net effect of changes cancelling each other out. There were 6110 cases of VA to VA transfers that appear as a hospitalization and a subsequent readmission and 2249 cases in which a patient with a VA hospitalization was transferred to or from a non-VA hospital. In research studies in which the mechanisms or risk factors related to hospital readmissions are of interest, it is important to measure accurately what is happening with each hospitalization rather than focusing on the overall rates. Additionally, individual hospital readmission rates are subject to change at each step after adjusting for VA to VA transfers and non-VA care. Studies that seek to compare hospital readmission rates should account for all sources to accurately measure readmission for each hospital.

Our paper has several limitations. We considered admissions within 1 day of a prior discharge to be inter-hospital transfers, recognizing that a patient may leave one hospital and not arrive to the next hospital until the next calendar day. While it is possible that some of these instances may have been a discharge and subsequent readmission, we wanted to bias towards under-estimating readmission because hospitals are penalized for high readmission rates. However, we did not encounter this case in the 50 validation cases with a VA to VA transfer that we considered; our validation suggests that our approach was reasonable and that same/next day readmissions appear uncommon. Again, these underlying assumptions can be modified for a given research question. Additionally, the data available to the VA regarding non-VA care is limited to hospitalizations in which the VA paid for the care. There are some situations in which a patient received care outside of the VA that the VA did not cover.

For the purposes of our research question, we focused on the specific issues related to VA data in CDW. However, these issues are not necessarily unique to the VA. As more systems are using electronic medical record data for these types of metrics, researchers need to be aware of the idiosyncrasies of the data structure to ensure accurate measures.

5. Conclusion

We have developed a robust way to identify acute hospitalizations using the VA CDW. We describe the approach and include statistical code so that the method can be used and adapted by others.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Department of Veteran Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Services (11–109 and 13–079) and from the National Institutes of Health (K08 GM115859). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the view of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s10742-018-0178-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Human and animal rights This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- Axon RN, Gebregziabher M, Everett CJ, Heidenreich P, Hunt KJ: Dual health care system use is associated with higher rates of hospitalization and hospital readmission among veterans with heart failure. Am. Heart J. 174, 157–163 (2016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center, VA Health Economics Research: Fee Basis Data: A Guide for Researchers. VA Palo Alto, Menlo Park: (2015) [Google Scholar]

- CMS.gov, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Readmissions reduction program (2016). https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/acuteinpatientpps/readmissions-reduction-program.html. Accessed 13 Apr 2017

- Denson JL, Jensen A, Saag HS, Wang B, Fang Y, Horwitz LI, Evans L, Sherman SE: Association between end-of-rotation resident transition in care and mortality among hospitalized patients. JAMA 316, 2204–2213 (2016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonsoulin M: VIReC Factbook: Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) Inpatient 2.1 Domain (Part I—Inpatient). U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research & Development Service, VA Information Resource Center, Hines: (2016) [Google Scholar]

- Institute, PricewaterhouseCoopers’ Health Research. The Price of Excess: Identifying Waste in Healthcare Spending (2008). http://www.oss.net/dynamaster/file_archive/080509/59f26a38c114f2295757bb6be522128a/The%20Price%20of%20Excess%20-%20Identifying%20Waste%20in%20Healthcare%20Spending%20-%20PWC.pdf. Accessed 13 Apr 2017

- Kheirbek RE, Wojtusiak J, Vlaicu SO, Alemi F: Lack of evidence for racial disparity in 30-day all-cause readmission rate for older US veterans hospitalized with heart failure. Qual. Manag. Health Care 25, 191–196 (2016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocher RP, Adashi EY: Hospital readmissions and the affordable care act: paying for coordinated quality care. JAMA 306, 1794–1795 (2011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn CG, Weeda ER, Kumar N, Wells PS, Peacock WF, Fermann GJ, Wang L, Baser O, Schein JR, Crivera C, Coleman CI: External validation of a claims-based and clinical approach for predicting post-pulmonary embolism outcomes among United States veterans. Intern. Emerg. Med. 12, 613–619 (2017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuti SV, Qin L, Rumsfeld JS, Ross JS, Masoudi FA, Normand SL, Murugiah K, Bernheim SM, Suter LG, Krumholz HM: Association of admission to veterans affairs hospitals vs. non-veterans affairs hospitals with mortality and readmission rates among older men hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, or pneumonia. JAMA 315, 582–592 (2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinne STA, Elwy R, Bastian LA, Wong ES, Wiener RS, Liu CF: Impact of multisystem health care on readmission and follow-up among veterans hospitalized for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Med. Care 55(Suppl 7 Suppl 1), s20–s25 (2017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. 172VA10P2: VHA Corporate Data Warehouse, VA. 79 FR 4377. Updated 31 Dec 2017 [Google Scholar]

- VA.gov, US Department of Veterans Affairs. Domiciliary Care for Homeless Veterans Program (2017). https://www.va.gov/homeless/dchv.asp. Accessed 31 Dec 2017

- van Walraven C, Bennett C, Jennings A, Austin PC, Forster AJ: Proportion of hospital readmissions deemed avoidable: a systematic review. CMAJ Can. Med. Assoc. J. 183, E391–E402 (2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong ES, Rinne ST, Hebert PL, Cook MA, Liu CF: Hospital distance and readmissions among va-medicare dual-enrolled veterans. J. Rural Health 32, 377–386 (2016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.