Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study was to estimate the vaccine effectiveness (VE) against hospitalization and severe illness in adolescents due to infection with SARS-CoV-2 variants (gamma, delta, and omicron).

Study design

A test-negative, case-control analysis was conducted in Brazil from July 2021 to March 2022. We enrolled 8458 eligible individuals (12-19 years of age) hospitalized with an acute respiratory syndrome, including 3075 cases with laboratory-proven COVID-19 and 4753 controls with negative tests for COVID-19. The primary exposure of interest was vaccination status. The primary outcome was SARS-CoV-2 infection during gamma/delta vs omicron-predominant periods. The aOR for the association of prior vaccination and outcomes was used to estimate VE.

Results

In the pre-omicron period, VE against COVID-19 hospitalization was 88% (95% CI, 83%-92%) and has dropped to 59% (95% CI, 49%-66%) during the omicron period. For hospitalized cases of COVID-19, considering the entire period of the analysis, 2-dose schedule was moderately effective against intensive care unit admission (46%, [95% CI, 27-60]), need of mechanical ventilation (49%, [95% CI, 32-70]), severe COVID-19 (42%, [95% CI, 17-60]), and death (46%, [95% CI, 8-67]). There was a substantial reduction of about 40% in the VE against all end points, except for death, during the omicron-predominant period. Among cases, 240 (6.6%) adolescents died; of fatal cases, 224 (93.3%) were not fully vaccinated.

Conclusion

Among adolescents, the VE against all end points was substantially reduced during the omicron-predominant period. Our findings suggest that the 2-dose regimen may be insufficient for SARS-CoV-2 variants and support the need for updated vaccines to provide better protection against severe COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, adolescents, vaccine, SARS-CoV-2 variants, omicron

The efficacy of the BNT162b2 vaccine against COVID-19 has exceeded 90% in clinical trials including adolescents.1 , 2 As the pandemic evolved, variants of SARS-CoV-2 emerged and spread across the world. A key question is whether authorized vaccines are effective against these emerging variants. In the adult population, modest reductions in vaccine efficacy against infection with the delta variant were observed.3 , 4 However, Andrews et al5 reported that 2 doses of the vaccines provided limited protection against symptomatic disease caused by the omicron variant. Similarly, case-control studies on US adolescents also reported a substantial reduction in vaccine efficacy in the omicron-predominant period.6, 7, 8 Vaccine performance is highly context-dependent and influenced by the population at risk.9 , 10 Therefore, evaluation of its effectiveness is needed in many different subgroups and regions.11 , 12 However, data on vaccine effectiveness (VE) against variants of concern in adolescents in developing countries are still limited.

This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of vaccination against hospitalization and severe illness for acute respiratory syndrome due to SARS-CoV-2 infection among a cohort of adolescents (12 to 19 years) hospitalized with acute respiratory syndrome using a Brazilian national disease surveillance system.

Methods

We used a test-negative case-control design to estimate VE against COVID-19 in adolescents (12-19 years) hospitalized with acute respiratory syndrome enrolled in the Influenza Epidemiological Surveillance Information System (SIVEP-Gripe) in Brazil. Adolescents with a reverse transcription real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) or antigen test for SARS-CoV-2 were eligible for analysis. Individuals who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 were defined as cases and those who tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 were assigned as controls. The odds of vaccination in adolescents with PCR or antigen-positive cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection were compared with the odds in adolescents who tested negative for SARS-CoV-2.

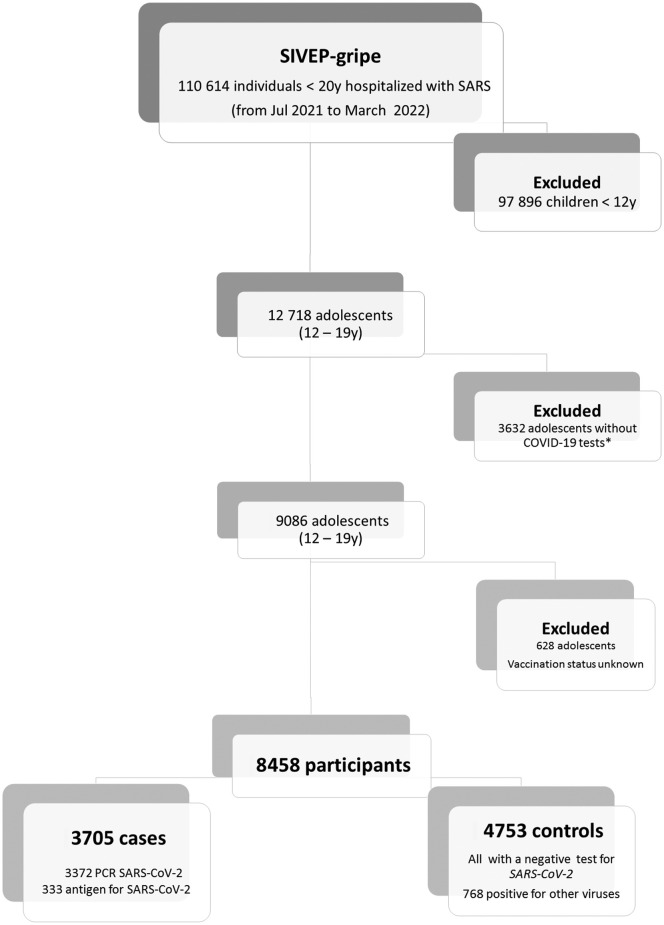

Detailed information about the selection of cases and controls is shown in Figure 1 (available at www.jpeds.com). Among controls, in addition to a negative test for SARS-CoV-2, 768 (6%) also tested positive for other viruses. We excluded 3632 individuals without COVID-19 tests available for the analysis (2008 waiting for the results, 983 missing information, 83 did not have any tests for COVID-19, and tests were inconclusive for 158 patients).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the cohort selection.

Data Source

We performed an analysis of all hospitalized patients younger than 20 years of age registered in the SIVEP-Gripe from July 2021 to March 2022. To enter the SIVEP-Gripe database, the case must have flu-like syndrome and at least one of the following criteria: dyspnea or respiratory distress or oxygen saturation less than 95% in room air or cyanosis or symptoms specific for infants (intercostal retractions, nasal flaring, dehydration, and inappetence). Detailed information regarding this database, including reporting form and data dictionary, codes, and all de-identified data, are publicly available at https://opendatasus.saude.gov.br/dataset. Additional information regarding SIVEP-Gripe and the steps of the data retrieval are provided as Supplementary Methods (available at www.jpeds.com).

Exposure of Interest

The primary exposure of interest was vaccination status, which was categorized at the time of the onset of symptoms as unvaccinated (no vaccine dose or symptoms onset 0-13 days after the first dose), partially vaccinated (symptoms onset 14 days or more after the first dose or 0-13 days after the second dose), or fully vaccinated (14 days or more after the second dose).

Covariates and Definitions

Clinical and demographic data recorded in SIVEP-Gripe are described in detail elsewhere.13 , 14 The database provides information on preexisting medical conditions. This information on comorbidities is provided in closed binary fields (presence/absence) and was collected at hospital admission and based on parents' or adolescents' self-report. Additional information about comorbidities and other covariates definitions, data preparation, and codification is provided as Supplementary Methods. We divided the cohort into 2 groups according to the period of admission: gamma/delta-predominant period and omicron-predominant period. According to genotype surveillance data in Brazil, the prevalence of the gamma variant was 75%-95% from July to the middle of September 2021; the prevalence of the delta variant was greater than 85% from September 15, 2021, to December 24, 2021, and omicron prevalence ranged from 85% to 100% from the last week of December, 2021, to March 2022.15

Outcomes

The primary outcome was SARS-CoV-2 infection, confirmed by RT-PCR or antigen testing. In addition, we evaluated VE against severe illness among cases with documented SARS-CoV-2 infection. The following end points were considered as indicators of severe illness: intensive care unit (ICU) admission, need for ventilatory support, and in-hospital mortality.16 In the SIVEP-gripe database, the variable “ventilatory support” is stratified into 3 categories (none, noninvasive, and invasive). Therefore, we analyzed the outcome “ventilatory support” in 2 ways: (1) the need for any ventilatory support (including noninvasive oxygen support and invasive mechanical ventilation) and (2) the need for invasive mechanical ventilation. In addition, we created a composite outcome, combining the same indicators into a single index. For this composite outcome, cases were classified as mild (no need for oxygen support and no ICU stay), moderate (need for noninvasive oxygen support and/or ICU admission), and severe (mechanical ventilation or death). Additional information on the definitions of the end points is provided in Supplementary Methods.

Statistical Analyses

For the descriptive statistical analysis, we used median and interquartile to summarize continuous variables and calculated frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. For the comparisons of proportions and medians, the χ2 and the Mann-Whitney U test were used, respectively.

The analysis was carried out in 2 steps. First, VE against COVID-19–associated hospitalization was estimated with the use of binary logistic regression, comparing odds ratios of vaccination status in cases as compared with controls with the following equation: VE = 100 × (1−OR). Vaccination status was included as an independent variable (fully vaccinated vs partially vaccinated vs unvaccinated). All models were adjusted by age, sex, ethnic group, geographic macroregions, and presence of comorbidities.17 The analyses were carried out initially for the entire period of the study and then also stratified according to the SARS-CoV-2 lineage predominance (gamma/delta vs omicron), age group, and type of vaccine (BNT162b2, ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, CoronaVac). Using the same multivariable regression model, we also assessed the possible waning of the VE effectiveness over time at 30-day intervals from the second dose of the vaccine in fully vaccinated adolescents.

In the second step of the analysis, we assessed the VE against severe illness in cases with laboratory-proven SARS-CoV-2 infection. For this second step, life-supporting interventions, disease severity, and in-hospital mortality were considered as dependent variables in separately constructed models. We used regression logistic for binary outcomes (ICU admission, need for invasive mechanical ventilation, and death), and multinominal regression logistic for disease severity (mild/moderate/severe). In-hospital mortality was evaluated by competing-risk analysis, using cumulative incidence function.18 Discharge was analyzed as a competing event. The proportional subdistribution hazards model by Fine and Gray19 was fitted to estimate the effect of covariates on mortality. All models were also adjusted by age, sex, ethnic group, geographic macroregions, and presence of comorbidities. In this second stage, we compared vaccine protection between the entire period vs the omicron-predominant period, because in the gamma/delta-predominant period there were only 47 fully vaccinated individuals precluding a robust analysis. The results are expressed as vaccine protection (%) using the same formula earlier described = 100 × (1−aOR) and 95% CIs.

Ethical Aspects

We accessed data in SIVEP-Gripe, which are already deidentified and publicly available. Following ethically agreed principles on open data, this analysis did not require ethical approval in Brazil.

Results

During the study period, 110 614 individuals under 20 years of age were hospitalized with an acute respiratory syndrome in Brazil and among them, 8458 adolescents met the inclusion criteria and were eligible for analysis. Of them, 3705 (43.8%) had proven SARS-CoV-2 infection and were categorized as cases and 4735 (56.2%) had negative tests for SARS-CoV-2 infection and were assigned as controls. The clinical and demographic characteristics of the participants stratified as cases and controls are shown in Table I . The overall median age of the participants was 16 years, with cases slightly older than controls. Cases were more frequently admitted during the omicron-predominant period and the clinical outcomes were significantly worse for cases compared with the controls.

Table I.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of case and controls hospitalized in Brazil from July 2021 to March 2022

| Characteristics | Overall (%) |

Cases |

Controls |

P∗ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8458 (100) | 3705 (100) | 4753 (100) | ||

| Age (y) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 16.2 (2.4) | 16.5 (2.2) | 16.0 (2.5) | <.0001 |

| Age group (y) | ||||

| 12-15 | 3553 (42.0) | 1306 (35.2) | 2247 (47.3) | <.0001 |

| 16-17 | 2186 (25.8) | 1073 (29.0) | 1113 (23.4) | |

| 18-19 | 2719 (32.1) | 1326 (35.8) | 1393 (29.3) | |

| Period of admission† | ||||

| Gamma/Delta | 5653 (66.8) | 2282 (61.6) | 3371 (70.9) | <.0001 |

| Omicron | 2805 (33.2) | 1423 (38.4) | 1382 (29.1) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 4588 (54.2) | 2045 (55.2) | 2543 (53.5) | .12 |

| Female | 3870 (45.8) | 1660 (44.8) | 2210 (46.5) | |

| Region | ||||

| Southeast | 4634 (54.8) | 1757 (47.4) | 2877 (60.5) | <.0001 |

| South | 1096 (13.0) | 750 (20.2) | 346 (7.3) | |

| Central-West | 723 (8.5) | 378 (10.2) | 345 (7.3) | |

| Northeast | 1344 (15.9) | 516 (13.9) | 828 (17.4) | |

| North | 661 (7.8) | 304 (8.2) | 357 (7.5) | |

| Ethinicity‡ | ||||

| White | 3400 (47.6) | 1618 (52.4) | 1782 (43.9) | <.0001 |

| Brown Black | 3628 (50.7) | 1414 (45.8) | 2214 (54.5) | |

| Asian | 66 (0.9) | 29 (0.9) | 37 (0.9) | |

| Indigenous | 56 (0.8) | 26 (0.8) | 30 (0.7) | |

| Signs/symptoms at presentation | ||||

| Fever | 4087 (59.0) | 2199 (59.4) | 2788 (58.7) | .53 |

| Cough | 5368 (63.5) | 2299 (62.1) | 3069 (64.6) | .02 |

| Dyspneia | 3989 (47.2) | 1764 (47.6) | 2225 (46.8) | .47 |

| Diarreha | 842 (10.0) | 407 (11.0) | 435 (9.2) | .005 |

| Number of comorbidities | ||||

| None | 6517 (77.1) | 2794 (75.4) | 3723 (78.3) | .002 |

| 1 | 1682 (19.9) | 801 (21.6) | 881 (18.5) | |

| ≥2 | 259 (3.1) | 110 (3.0) | 149 (3.1) | |

| Oxygen saturation <95%‡ | ||||

| Yes | 3251 (49.6) | 1465 (51.4) | 1786 (48.2) | .01 |

| ICU‡ | ||||

| Yes | 2134 (26.1) | 1021 (27.6) | 1113 (24.9) | .006 |

| Ventilatory support‡ | ||||

| None | 4092 (55.0) | 2043 (59.6) | 2049 (51.1) | |

| Noninvasive | 2537 (34.1) | 1015 (29.6) | 1522 (37.9) | <.0001 |

| Invasive | 813 (10.9) | 371 (10.8) | 442 (11.0) | |

| Severity index§ | ||||

| Mild | 4120 (48.7) | 1660 (44.8) | 2460 (51.8) | |

| Moderate | 3303 (39.1) | 1562 (42.2) | 1741 (36.6) | <.0001 |

| Severe | 1035 (12.2) | 483 (13.0) | 552 (11.6) | |

| Outcomes‡ | ||||

| Discharge | 7508 (91.5) | 3260 (89.3) | 4248 (93.3) | |

| Death | 497 (6.1) | 240 (6.6) | 257 (5.6) | <.0001 |

| In-hospital | 197 (2.4) | 149 (4.1) | 48 (1.1) | |

| Vaccination status | ||||

| Unvaccinated | 5760 (68.1) | 2848 (76.9) | 2912 (61.3) | |

| Partially | 1522 (18.0) | 459 (12.4) | 1063 (22.4) | <.0001 |

| Fully | 1176 (13.9) | 398 (10.7) | 778 (16.4) |

P, comparison between cases and controls.

Gamma/Delta predominance (June 25, 2021, to December 24, 2021) and Omicron predominance (December 25, 2021, to March 28, 2022).

Missing data: Ethnicity, 1308; Oxygen saturation, 2105; ICU admission, 278; Ventilatory support, 1,016; Outcomes, 241; and 15 death for other causes.

Severity index: mild (no need of oxygen support and no admission ICU), moderate (need of noninvasive oxygen support and admission in ICU), and severe (mechanical ventilation or death).

Vaccination Status

Among 8458 persons included in the study, 5760 (68.1%) were unvaccinated at the onset of symptoms, 1522 (18%) had received 1 dose (assigned as partially vaccinated), and 1176 (13.1%) had received 2 doses (assigned as fully vaccinated). Among 3705 cases with laboratory-proven COVID-19 included in the study, 2848 (76.9%) were unvaccinated at the onset of symptoms, 459 (12.4%) had received 1 dose, and 398 (10.7%) were fully vaccinated. Of 2282 cases admitted during the gamma/delta predominance, 179 (7.8%) were partially vaccinated and only 41 (1.8%) were fully vaccinated, whereas of 1423 cases hospitalized during the omicron-predominant period, the respective values were 280 (19.7%) and 357 (25.1%).

Regarding vaccine types, all 1555 vaccinated adolescents younger than 18 years of age received mRNA vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech). Among 1069 vaccinated adolescents older than 18 years, 533 (49.8%) received an mRNA vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech), 357 (33.3%) virus-inactivated vaccine (Sinovac; CoronaVac), 171 (16.0%) adenovirus-vector vaccine ChAdOx1nCoV-19 (AstraZeneca), and only 8 (0.7%) received the vaccine JNJ-78436735 (Janssen). Additional information about vaccination status and schedules used in Brazil is provided in the Supplementary Methods.

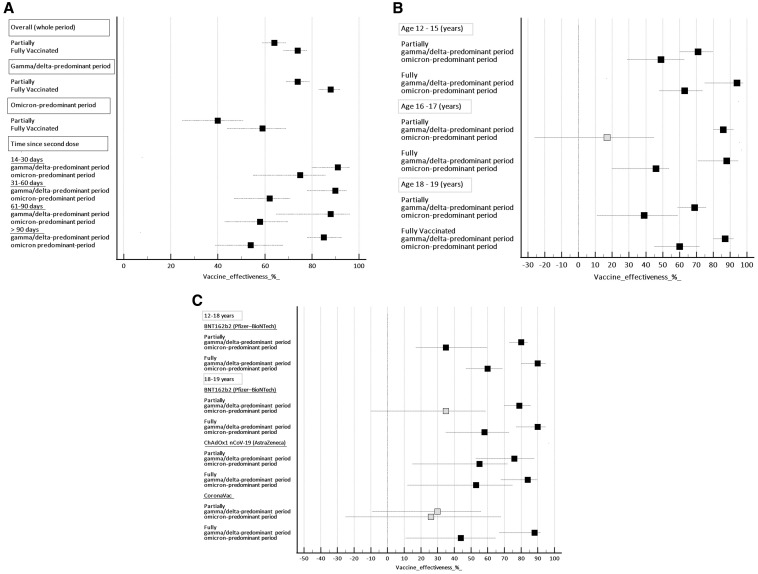

VE Against COVID-19

VE against SARS-CoV-2 infection leading to hospitalization in adolescents who were partially and fully vaccinated according to the variants predominance, time since the second dose, age group, and vaccine type is shown in Figure 2 (A-C; available at www.jpeds.com). The overall effectiveness for those individuals fully vaccinated was 74% (95% CI, 68%-78%) and for those partially vaccinated was 64% (95% CI, 59%-69%). VE was higher in the gamma/delta-predominant period than in the omicron period. During the gamma/delta-predominant period, the effectiveness for those individuals fully vaccinated reached 88% (95% CI, 83%-92%), whereas during the omicron period, the VE dropped to 59% (95% CI, 49%-66%) (Figure 2, A). The overall median interval time since the second dose of the vaccine was 68 days (IQR, 45-102). For the adolescents admitted during the gamma/delta-predominant and omicron-predominant periods, the median interval since the second vaccine dose was 54 days (IQR, 31-79 days) and 75 days (IQR, 50-107 days), respectively. During the delta-dominant period, VE for SARS-CoV-2 infection in adolescents after 2 doses of vaccine peaked at 14-30 days (91%, 95% CI, 80%-96%) and gradually declined to 85% (95% CI, 78%-93%) after 90 days from the second dose. Vaccines were less effective against the omicron variant than the gamma/delta variant at all intervals after the second dose of the vaccine. During the omicron-predominant period, after the second dose, VE also peaked between 14 and 30 days (75%, 95% CI, 55%-86%) and had a steadily decline to only 54% (39%-68%) at 90 days and longer (Figure 2, A). In the gamma/delta-predominant period, for individuals fully vaccinated, the VE was similar among the age groups (Figure 2, B). The VE was 94% (95% CI, 75-98), 88% (95% CI, 71-95), and 87% (95% CI, 80-92) for the age groups 12-15 years, 16-17 years, and 18 years or older, respectively. However, in the omicron-predominant period, there was a substantial reduction in the VE for all age groups (Figure 2, B). The comparative analysis of vaccine types was stratified according to age groups because adolescents from 12 to 17 years of age received only the BNT162b2 vaccine. In this subgroup, the VE for those fully vaccinated was 90% (95% CI, 80-95) in the gamma/delta-predominant period. However, during the omicron-predominant period, the VE was reduced to 60% (95% CI, 47-69) (Figure 2, C). For adolescents of 18 years or older, in the gamma/delta-predominant period, the effectiveness of mRNA vaccine was slightly higher (90%, 95% CI, 77-95) than that of virus-inactivated vaccines (88%, 95% CI, 67-90) and adenovirus-vector vaccine (84%, 95% CI, 68-90). During the omicron-predominant period, the estimated VE was also substantially reduced for all vaccine types (Figure 2, C).

Figure 2.

Effectiveness of the vaccine against hospitalization for COVID-19 in adolescents stratified according to A, variant-predominant periods and time since second-dose, B, age groups, and C, vaccine types and age groups. Reference category is unvaccinated individuals. Black markers, P < .05; Grey markers P > .05.

VE Against Severe Outcomes

The clinical and demographic characteristics of the cases stratified by the vaccination status are shown in Table 2 . The proportion of fully vaccinated was significantly higher in older patients, female sex, white ethnicity, from the highest-income region of the country, and those admitted in the omicron-predominant period. In this comparative univariate analysis, all relevant outcomes of the severity of COVID-19 were significantly higher in non–fully vaccinated patients.

Table II.

Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patient cases according to vaccination status

| Characteristics/Outcomes | Unvaccinated |

Partially |

Fully |

P∗ | P† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2848 (100) | 459 (100) | 398 (100) | |||

| Age (y) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 16.4 (2.3) | 16.6 (2.0) | 17.4 (2.0) | <.0001 | |

| Age group (y) | |||||

| 12-15 | 2664 (46.2) | 575 (37.8) | 314 (26.7) | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| 16-17 | 1519 (26.4) | 396 (26.0) | 271 (23.0) | ||

| 18-19 | 1577 (27.4) | 551 (36.2) | 591 (50.3) | ||

| Period of admission‡ | |||||

| Gamma/Delta | 2062 (72.4) | 179 (39.0) | 41 (10.3) | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Omicron | 786 (27.6) | 280 (61.0) | 357 (89.7) | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 1505 (52.8) | 277 (60.3) | 263 (66.1) | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Female | 1343 (47.2) | 182 (39.7) | 135 (33.9) | ||

| Region | |||||

| Southeast | 1336 (46.9) | 211 (46.0) | 210 (52.8) | <.0001 | .009 |

| South | 575 (20.2) | 91 (19.8) | 84 (21.1) | ||

| Central-West | 307 (10.8) | 44 (9.6) | 27 (6.8) | ||

| Northeast | 393 (13.8) | 66 (14.4) | 57 (14.3) | ||

| North | 237 (8.3) | 47 (10.2) | 20 (5.0) | ||

| Ethinicity§ | |||||

| White | 1214 (51.8) | 220 (52.9) | 184 (56.4) | .22 | .21 |

| Brown Black | 1093 (46.6) | 184 (44.2) | 137 (42.0) | ||

| Asian | 21 (0.9) | 7 (1.7) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| Indigenous | 17 (0.7) | 5 (1.2) | 4 (1.2) | ||

| Signs/symptoms at presentation | |||||

| Fever | 1734 (60.9) | 268 (58.4) | 197 (49.5) | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Cough | 1814 (63.7) | 258 (56.2) | 227 (57.0) | .001 | .03 |

| Dyspneia | 1438 (50.5) | 180 (39.2) | 146 (36.7) | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Gastrointestinal | 327 (11.5) | 53 (11.5) | 27 (6.8) | .02 | .85 |

| Number of comorbidities | |||||

| None | 2159 (75.8) | 335 (73.0) | 300 (75.4) | .76 | .96 |

| 1 | 606 (21.3) | 108 (23.5) | 87 (21.9) | ||

| 2 | 83 (2.9) | 16 (3.5) | 11 (2.8) | ||

| Oxygen saturation <95%§ | |||||

| Yes | 1210 (54.5) | 137 (39.8) | 118 (41.4) | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| ICU | |||||

| Yes | 820 (28.8) | 116 (25.3) | 85 (21.4) | .004 | .03 |

| Ventilatory support§ | |||||

| None | 1473 (56.2) | 284 (68.4) | 286 (72.6) | ||

| Noninvasive | 855 (32.6) | 88 (21.2) | 72(18.3) | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Invasive | 292 (11.1) | 43 (10.4) | 36 (9.1) | ||

| Severity index¶ | |||||

| Mild | 1190 (41.8) | 248 (54.0) | 222 (55.8) | ||

| Moderate | 1278 (44.9) | 152 (33.1) | 132 (33.2) | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Severe | 380 (13.3) | 59 (12.9) | 44 (11.1) | ||

| Outcomes§ | |||||

| Discharge | 2511 (89.6) | 397 (88.4) | 352 (88.4) | ||

| Death | 194 (6.9) | 30 (6.7) | 16 (4.0) | .001 | <.0001 |

| In-hospital | 97 (3.5) | 22 (4.9) | 30 (7.5) |

P, comparison among of 3 groups.

P, comparison between unvaccinated/partially vs fully vaccinated groups.

Gamma/Delta predominance (June 25, 2021, to December 24, 2021) and Omicron predominance (December 25, 2021, to March 28, 2022).

Missing data: Ethnicity, 618; Oxygen saturation, 855; Ventilatory support, 276; Outcomes, 56.

Severity index: mild (no need of oxygen support and no admission ICU), moderate (need of noninvasive oxygen support and admission in ICU), and severe (mechanical ventilation or death).

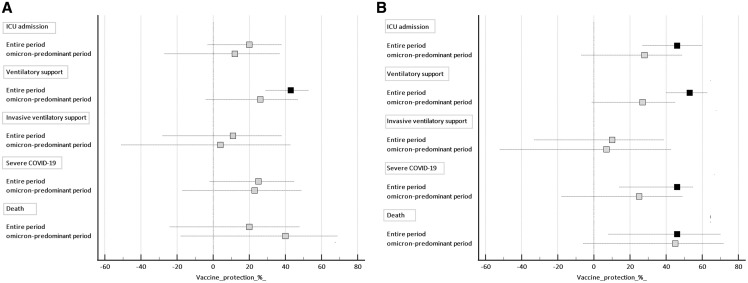

Vaccine protection against clinical outcomes of disease severity in patients with proven COVID-19 is shown in Figure 3 . All models were adjusted by age, sex, ethnicity, macroregion of the country, and presence of comorbidities. For partially vaccinated cases, there was a significant protection only against the need for any ventilatory support (49%, 95% CI, 32-70, P < .001) considering the entire period of the study (Figure 3, A). For fully vaccinated individuals, considering the entire period, there was a significant protection against the need of ICU admission (46%, 95% CI, 27-60, P < .001), need for any ventilatory support (49%, 95% CI, 32-70, P < .001), severe COVID-19 (42%, 95% CI, 17-60, P < .001), and death (46%, 95% CI, 8-67, P = .02), but not for invasive mechanical ventilation (10%, 95% CI, −33 to 39, P = .55). On the other hand, during the omicron-predominant period, there was no significant protection against all end points of disease severity even for fully vaccinated cases (Figure 3, B).

Figure 3.

Effectiveness of the vaccine against severe outcomes of COVID-19 in adolescents. A, Partially vaccinated; B, Fully vaccinated. Reference category is unvaccinated individuals. Black markers, P < .05; Grey markers P > .05.

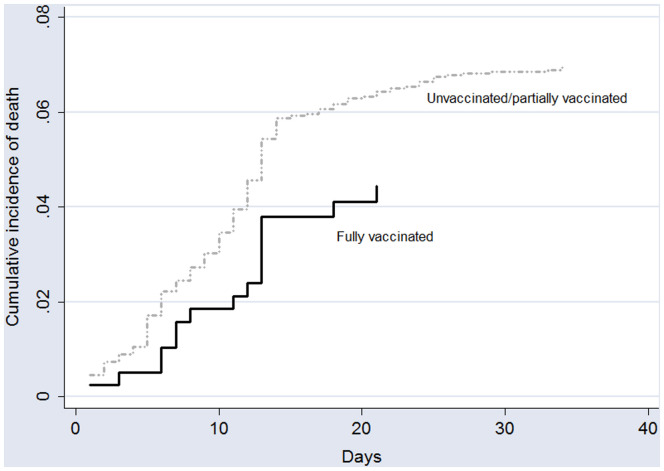

Among the 240 adolescents who died, 224 (93.3%) were not fully vaccinated. According to the competing-risk survival analysis, the estimated probability of fatal outcomes was 4.4% and 7.2%, for fully vaccinated adolescents and unvaccinated/partially vaccinates cases, respectively. The cumulative incidence of death according to the vaccination status is shown in Figure 4 (available at www.jpeds.com).

Figure 4.

Cumulative incidence of death according to the vaccination status (fully vaccinated vs unvaccinated/partially vaccinated).

Discussion

In this real-world analysis, we observed, after the second dose of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, high effectiveness of vaccines against COVID-19 and moderate effectiveness against severe outcomes of the disease during the gamma/delta-predominant period. However, our findings revealed a substantial reduction of the VE against SARS-CoV-2 infection and also against severe outcomes during the omicron-predominant period.

Epidemiological data have shown that children and adolescents have a low risk of severe disease and COVID-19–related death. However, data from low-income regions are quite diverse from findings of high-income countries that reported an overall mortality rate of 1% or even less in hospitalized pediatric patients20 Data from Brazil and Africa showed an overall mortality rate of 7.7% (1661 of 21 591) and 8.3% (39 of 469) in pediatric patients hospitalized with COVID-1913 , 14 , 21 , 22 These findings have clinical and public health implications and the implementation of an efficacious vaccination program is urgently needed for children and adolescents in low-income regions23

The first randomized trial of the BNT162b2 vaccine in recipients from 12 to 15 years, conducted before the emergence of the omicron variant, reported a favorable safety profile and was highly effective against SARS-CoV-2 infection (100%, [95% CI, 75.3-100])1 In addition, several studies showed that the BNT162b2 vaccine was highly effective in reducing the risk of hospitalization and severe COVID-19 outcomes in adolescents during the delta variant period.8 , 24 , 25 However, early assessments of the vaccination against COVID-19 and severe outcomes of the disease among adolescents during the omicron variant period have shown a substantial reduction in VE. For instance, Price et al,26 in a test-negative case-control study, reported that in the delta-predominant period, VE against hospitalization for COVID-19 among adolescents from 12 to 18 years of age was 93% (95% CI, 89-95), whereas during the omicron-predominant period, VE was only 40% (95% CI, 9-60). Using a similar design with a large sample size enrolled during the omicron-predominant period, Fleming-Dutra et al6 reported that the estimated VE was 59.5%, 2 to 4 weeks after the second dose, and only 16.6% during the second month after vaccination. Similarly, in a prospective cohort study, Fowlkes et al7 reported that the effectiveness of the 2-dose BNT162b2 vaccine schedule in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection among adolescents from 12 to 15 years was 81% (95% CI, 51-93) for delta variant infections, whereas for omicron infections, the value reduced to 59% (95% CI, 24-78). Of note, our findings from a developing country are in close agreement with these studies. In our analysis, considering the fully vaccinated adolescents, the VE was 88% during the pre-omicron period, whereas, during the omicron-predominant period, the VE dropped to 59% (95% CI, 49%-66%). Taken together, these results highlighted a reduction of about 30%-50% in the VE of the 2-dose vaccine schedule against infection of the omicron variant. Importantly, our findings highlight the concomitant reduction in vaccine protection related to the natural decline in VE over time and also regarding the omicron variant. We observed that the VE was consistently lower during the omicron-predominant period compared with the gamma/delta-predominant period for the same time intervals since the second dose. Previous studies have reported a similar pattern of the waning VE against symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection in adolescents. For instance, data from England on VE against symptomatic infection among people aged 16-17 years showed that after the second dose, VE peaked at 14-34 days (96%, 95% CI, 95.2%-96.8%) for the delta variant and at 7-13 days for the omicron variant (76.1%, 95% CI, 73.4%-78.6%) variant. Effectiveness fell rapidly for omicron after day 34, reaching 22.6% (95% CI, 14.5%-29.9%) 70 days after dose 2, compared with 83.7% (95% CI, 72.0%-90.5%) for the delta variant.27 Overall, these findings are consistent with early genomic data that predicted the potential immune evasion of the omicron variant. These studies demonstrated that the omicron receptor-binding domain binds to human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 with enhanced affinity, and marked reductions in neutralizing activity were observed against omicron compared with the ancestral virus in the plasma of convalescent individuals and of individuals who were vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2.28, 29, 30

In the second part of our analysis, we assessed the VE against severe clinical outcomes and COVID-19–related death among adolescents positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection. We observed an overall protection, with the 2-dose schedule, of about 40% against all end points except the need for invasive mechanical ventilation for which the value was about 10%. However, our findings showed that the VE has dropped to about 20% in the omicron period for most endpoints analyzed, except for in-hospital mortality, which remained around 45% in both periods. Similarly, early studies in the pre-omicron period showed impressive evidence of the BNT162b2 efficacy against serious illness, but with substantially lower protection during the omicron-predominant period.25 , 26

The strength of our study is the size of the population-based cohort, which allows a real-world analysis of VE among adolescents hospitalized with acute respiratory syndrome during distinct periods of the COVID-19 pandemic in a middle-income country. On the other hand, the conclusions of this report must be considered in light of several limitations. First, the predominant periods of SARS-CoV-2 lineages were assigned based on the prevalence of the strains in the Brazilian population at the time and not on the individual sequencing of the virus in the patients. Second, another relevant limitation is that the number of fully vaccinated cases during the period of gamma/delta predominance was small, precluding a reliable analysis separately of VE against a severe illness for this group in this period. Third, misclassification of cases and controls cannot be ruled out, especially given the reduced sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 antigen assays. However, for most individuals (91%) included in the study, the test used was RT-PCR. Fourth, we were unable to include previous SARS-CoV-2 infection status as a confounder. Prior infection may provide protective immunity, especially when associated with vaccination, and therefore may modify the effectiveness of the vaccine.31 Fifth, the negative test design used in our study has been routinely used to estimate the effectiveness of the seasonal flu vaccine, but its application in COVID-19 studies, although increasingly common, is new.15 , 22 , 32 , 33 A key point of the negative test design is whether there are differences between vaccinated and unvaccinated people that could influence the occurrence of the disease. Confusion by measured and unmeasured variables is a concern in observational studies. In this context, confounders are variables that influence both receipts of the vaccine and the occurrence of COVID-19 medically attended.33 To partially overcome this issue, we used various regression models to adjust for several measured confounders, including demographic and clinical variables and admission period.

For individuals 18-19 years of age, in the gamma/delta-predominant period, we found similar effectiveness for the BNT162b2, ChAdOx1nCoV-19, and CoronaVac vaccines. Our findings suggest that, for the omicron variant, the 2-dose regimen may be insufficient for adolescents. Additional studies with longer follow-up and continuous monitoring of vaccine efficacy and durability against hospitalization, critical illness, and death associated with COVID-19 are needed to guide vaccination strategies. Furthermore, our findings support the need for updated vaccines to provide better protection against COVID-19 and serious outcomes caused by emerging variants.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to the frontline clinical staff of the Brazilian Public Health System (SUS) who collected these data in challenging circumstances for their invaluable contribution in these difficult times. All data from the SIVEP-Gripe (Influenza Epidemiological Surveillance Information System) were systematically collected by these frontline health care workers.

Footnotes

This study was supported by the CNPq (National Council for Scientific and Technological Development) and FAPEMIG (Research Support Foundation of Minas Gerais). The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary data

Appendix

References

- 1.Frenck R.W., Jr., Klein N.P., Kitchin N., Gurtman A., Absalon J., Lockhart S., et al. Safety, Immunogenicity, and efficacy of the BNT162b2 Covid-19 vaccine in adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:239–250. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walter E.B., Talaat K.R., Sabharwal C., Gurtman A., Lockhart S., Paulsen G.C., et al. Evaluation of the BNT162b2 Covid-19 vaccine in children 5 to 11 years of age. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:35–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abu-Raddad L.J., Chemaitelly H., Butt A.A., National Study Group for C-V Effectiveness of the BNT162b2 Covid-19 vaccine against the B.1.1.7 and B.1.351 variants. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:187–189. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2104974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lopez Bernal J., Gower C., Andrews N. Public health England delta variant vaccine effectiveness study G. Effectiveness of Covid-19 vaccines against the B.1.617.2 (Delta) Variant. Reply. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:e92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2113090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrews N., Stowe J., Kirsebom F., Toffa S., Rickeard T., Gallagher E., et al. Covid-19 vaccine effectiveness against the Omicron (B.1.1.529) Variant. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1532–1546. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2119451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleming-Dutra K.E., Britton A., Shang N., Derado G., Link-Gelles R., Accorsi E.K., et al. Association of Prior BNT162b2 COVID-19 Vaccination With Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Children and Adolescents During Omicron Predominance. JAMA. 2022;327:2210–2219. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.7493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fowlkes A.L., Yoon S.K., Lutrick K., Gwynn L., Burns J., Grant L., et al. Effectiveness of 2-Dose BNT162b2 (Pfizer BioNTech) mRNA vaccine in preventing SARS-CoV-2 Infection among children aged 5-11 years and adolescents aged 12-15 years - PROTECT Cohort, July 2021-February 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:422–428. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7111e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein N.P., Stockwell M.S., Demarco M., Gaglani M., Kharbanda A.B., Irving S.A., et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 mRNA vaccination in preventing COVID-19-associated emergency department and urgent care encounters and hospitalizations among nonimmunocompromised children and adolescents aged 5-17 years - VISION network, 10 states, April 2021-January 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:352–358. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7109e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hungerford D., Cunliffe N.A. Real world effectiveness of covid-19 vaccines. BMJ. 2021;374:n2034. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Florentino P.T.V., Millington T., Cerqueira-Silva T., Robertson C., de Araujo Oliveira V., Junior J.B.S., et al. Vaccine effectiveness of two-dose BNT162b2 against symptomatic and severe COVID-19 among adolescents in Brazil and Scotland over time: a test-negative case-control study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00451-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ranzani O.T., Hitchings M.D.T., Dorion M., D'Agostini T.L., de Paula R.C., de Paula O.F.P., et al. Effectiveness of the CoronaVac vaccine in older adults during a gamma variant associated epidemic of covid-19 in Brazil: test negative case-control study. BMJ. 2021;374:n2015. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ranzani O.T., Silva A.A.B., Peres I.T., Antunes B.B.P., Gonzaga-da-Silva T.W., Soranz D.R., et al. Vaccine effectiveness of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 against COVID-19 in a socially vulnerable community in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: a test-negative design study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022;28:736 e1–e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2022.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oliveira E.A., Colosimo E.A., Simoes e Silva A.C., Mak R.H., Martelli D.B., Silva L.R., et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for death among hospitalised children and adolescents with COVID-19 in Brazil: an analysis of a nationwide database. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5:559–568. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00134-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oliveira E.A., Simoes e Silva A.C., Oliveira M.C.L., Colosimo E.A., Mak R.H., Vasconcelos M.A., et al. Comparison of the first and second waves of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic in children and adolescents in a middle-income country: clinical impact associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 gamma lineage. J Pediatr. 2022;244:178–185 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2022.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Latif A.A., Mullen J.L., Alkuzweny M., Tsueng G., Cano M., Haag E., et al. Omicron Variant Report. outbreak.info: Center for Viral Systems Biology. 2022. https://outbreak.info/situation-reports/omicron?selected=BRA&loc=BRA

- 16.WHO Working Group on the Clinical Characterisation and Management of COVID-19 infection A minimal common outcome measure set for COVID-19 clinical research. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:e192–e197. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30483-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel M.K., Bergeri I., Bresee J.S., Cowling B.J., Crowcroft N.S., Fahmy K., et al. Evaluation of post-introduction COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness: summary of interim guidance of the World Health Organization. Vaccine. 2021;39:4013–4024. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.05.099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Putter H., Fiocco M., Geskus R.B. Tutorial in biostatistics: competing risks and multi-state models. Stat Med. 2007;26:2389–2430. doi: 10.1002/sim.2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fine J.P., Gray R.J. A proportional hazards model for the sub-distribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitano T., Kitano M., Krueger C., Jamal H., Al Rawahi H., Lee-Krueger R., et al. The differential impact of pediatric COVID-19 between high-income countries and low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review of fatality and ICU admission in children worldwide. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nachega J.B., Sam-Agudu N.A., Machekano R.N., Rabie H., van der Zalm M.M., Redfern A., et al. Assessment of clinical outcomes among children and adolescents hospitalized with COVID-19 in 6 sub-saharan African countries. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176 doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.6436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oliveira E.A., Colosimo E.A., Simoes e Silva A.C. The need to study clinical outcomes in children and adolescents with COVID-19 from middle- and low-income regions. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176:727–728. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sam-Agudu N.A., Quakyi N.K., Masekela R., Zumla A., Nachega J.B. Children and adolescents in African countries should also be vaccinated for COVID-19. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-008315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glatman-Freedman A., Hershkovitz Y., Kaufman Z., Dichtiar R., Keinan-Boker L., Bromberg M. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 vaccine in adolescents during outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant infection, Israel, 2021. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:2919–2922. doi: 10.3201/eid2711.211886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olson S.M., Newhams M.M., Halasa N.B., Price A.M., Boom J.A., Sahni L.C., et al. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 vaccine against critical Covid-19 in adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:713–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2117995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Price A.M., Olson S.M., Newhams M.M., Halasa N.B., Boom J.A., Sahni L.C., et al. BNT162b2 protection against the Omicron variant in children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1899–1909. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2202826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Powell A.A., Kirsebom F., Stowe J., McOwat K., Saliba V., Ramsay M.E., et al. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 against COVID-19 in adolescents. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:581–583. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00177-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Viana R., Moyo S., Amoako D.G., Tegally H., Scheepers C., Althaus C.L., et al. Rapid epidemic expansion of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in southern Africa. Nature. 2022;603:679–686. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04411-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cameroni E., Bowen J.E., Rosen L.E., Saliba C., Zepeda S.K., Culap K., et al. Broadly neutralizing antibodies overcome SARS-CoV-2 Omicron antigenic shift. Nature. 2022;602:664–670. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04386-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dejnirattisai W., Huo J., Zhou D., Zahradnik J., Supasa P., Liu C., et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron-B.1.1.529 leads to widespread escape from neutralizing antibody responses. Cell. 2022;185:467–84 e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.12.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hall V., Foulkes S., Insalata F., Kirwan P., Saei A., Atti A., et al. Protection against SARS-CoV-2 after Covid-19 vaccination and previous infection. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1207–1220. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2118691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chua H., Feng S., Lewnard J.A., Sullivan S.G., Blyth C.C., Lipsitch M., et al. The use of test-negative controls to monitor vaccine effectiveness: a systematic review of methodology. Epidemiology. 2020;31:43–64. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000001116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dean N.E., Hogan J.W., Schnitzer M.E. Covid-19 Vaccine Effectiveness and the Test-Negative Design. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1431–1433. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2113151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.