Summary

Non-replicating rotavirus vaccines are an alternative strategy to improve the efficacy and safety of rotavirus vaccines. The spike protein VP4, which could be enzymatically cleaved into VP8∗ and VP5∗, is an ideal target for the development of recombinant rotavirus vaccine. In our previous studies, we demonstrated that the truncated VP4 (aa26-476, VP4∗) could be a more viable vaccine candidate compared to VP8∗ and VP5∗. Here, to develop a human rotavirus vaccine, the VP4∗ proteins of P[4], P[6], and P[8] genotype rotaviruses were expressed. All VP4∗ proteins can stimulate high levels of neutralizing antibodies in both guinea pigs and rabbits when formulated in aluminum adjuvant. Furthermore, bivalent VP4∗-based vaccine (P[8] + P[6]-VP4∗) can stimulate high levels of neutralizing antibodies against various genotypes of rotavirus with no significant difference as compared to the trivalent vaccines. Therefore, bivalent VP4∗ has the potential to be a viable rotavirus vaccine candidate for further development.

Subject areas: Biological sciences, Microbiology, Virology, Viral microbiology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Purified rotavirus VP4∗ proteins form homogenic and stable trimers

-

•

VP4∗ stimulated high levels of homotypic and heterotypic neutralizing antibodies

-

•

The immunogenicity of different genotype VP4∗ is not influenced by each other

-

•

Bivalent VP4∗ (P[8]+P[6]) stimulated protective immunity against most prevalent rotaviruses

Biological sciences; Microbiology; Virology; Viral microbiology

Introduction

Diarrheal disease is a leading child killer (Kotloff et al., 2013), and rotavirus is the leading cause of diarrhea-associated morbidity and mortality in infants and children younger than 5 years old (Lanata et al., 2013). The annual number of death due to rotavirus infection is approximately 146,480 worldwide, and the vast majority of these deaths occurred in the low-income countries in Africa and Asia (Faris, 2018). Four live attenuated rotavirus vaccines have been prequalified by WHO, among which Rotarix (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals) and RotaTeq (Merck & Co., Inc.) have been implemented in the national immunization schedule worldwide (AuthorAnonymous, 2013). The live attenuated vaccines are effective in reducing rotavirus-associated morbidity and mortality (Clark et al., 2019; O'Ryan and Linhares, 2009). However, the effectiveness of these vaccines is significantly decreased in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) compared to high-income countries (Armah et al., 2010; Bhandari et al., 2014; Isanaka et al., 2017; Kulkarni et al., 2017; Stockman, 2011; Zaman et al., 2010).

The decreased efficacy of live attenuated rotavirus vaccines in LMICs could be due to several reasons, such as high titers of maternal antibodies (Armah et al., 2010; Bhandari et al., 2014; Zaman et al., 2010), enteric virome (Kim et al., 2022), enteropathy (Parker et al., 2018), and differences in host receptor human histoblood group antigens (HBGAs) (Nordgren et al., 2014; Coulson, 2015). Non-replicating rotavirus vaccines could potentially overcome the efficacy issues of live attenuated vaccines, because they may circumvent the interference of maternal antibody, enteropathy, and the differences in HBGAs. Moreover, the safety of non-replicating rotavirus vaccines should be also higher than oral vaccines. Therefore, different parenteral, non-replicating rotavirus vaccines have been developed, including inactivated vaccines (Jiang et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2015), virus-like particles (Azevedo et al., 2013; Changotra and Vij, 2017), and single subunit vaccines (Groome et al., 2020; Xue et al., 2015).

A series of rotavirus antigens, such as VP4 (Li et al., 2018), VP7 (Khodabandehloo et al., 2012), VP6 (Afchangi et al., 2019), and NSP4 (Liu et al., 2021) can stimulate protective immunity and confer protection in animal models. Among these antigens, the spike protein VP4, which mediates rotavirus attachment and internalization, was most explored (Dunn et al., 1995; Jia et al., 2017; Li et al., 2010, 2018; Wen et al., 2012). VP4 can be enzymatically cleaved into VP8∗ and VP5∗, and both VP8∗ and VP5∗ can stimulate neutralizing antibodies (Nair et al., 2017; Trask et al., 2012). The most advanced recombinant rotavirus vaccine was based on the distal hemagglutinin domain of VP4 (ΔVP8) (Wen et al., 2012), which was fused to the Th2 epitope of tetanus toxin (P2) to improve the immunogenicity of ΔVP8 (P2-VP8) (Groome et al., 2017). However, Dunn et al. found that VP4 can stimulate higher immune responses and confers higher protective efficacy than VP8 and VP5 (Dunn et al., 1995). In our previous studies, we also found that the immunogenicity of truncated murine and lamb rotavirus VP4∗, which contains VP8 and VP5 antigen domain, was also higher than VP8∗ and VP5∗ alone (Li et al., 2018). Immunization with VP4∗ provided 100% protection against fecal shedding of rotavirus and severe diarrhea in mice when formulated with aluminum adjuvant (Li et al., 2018). Therefore, VP4∗ was expected to be a viable candidate antigen for recombinant rotavirus vaccines.

In human, P[4], P[6], and P[8] are the most prevalent P genotypes of rotaviruses (Gupta et al., 2019). Therefore, in this study, VP4∗ protein of P[8], P[4], and P[6] genotypes was expressed and purified, and their immunogenicity were evaluated. The results show that all the three genotypes of VP4∗ proteins are highly immunogenic, and bivalent VP4∗-based vaccine (P[8]+ P[6]) can stimulate high level of protective antibodies against the common genotypes of rotaviruses.

Result

Purification and characterization of truncated VP4 proteins

Among prevalent human rotaviruses, P[8] are the most prevalent P genotypes, followed by P[4] and P[6], and these three P genotypes account for more than 95% of human rotaviruses (Doro et al., 2014). To develop a human rotavirus vaccine, the VP4∗ proteins of P[4], P[6], and P[8] strains were expressed in E.coli BL21(DE3), and the soluble proteins were purified from the supernatant. After ion exchange and hydrophobic exchange chromatography, the purity of VP4 proteins was higher than 95% as analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and the identity was confirmed by Western blot (Figures 1A and 1B). Native-PAGE results showed that the size of VP4∗ protein ranged from 130 to 170 kDa. We hypothesized that VP4∗ protein existed as trimer in TB8.8 buffer (Figure 1C). The homogeneity of the purified VP4∗ proteins was analyzed by HPSEC, and the results showed that the purified VP4∗ proteins were eluted in a single peak with a retention time of about 14 min (Figures 1D–1F). As analyzed by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), two peaks were observed for all the three genotypes of VP4∗ proteins, indicating that there were two distinct thermal transitions during the unfolding process. We speculated that the first peak represents the transition of VP4∗ from trimers to monomers, while the second peak represents the unfolding of VP4∗ monomers (Figures 1G–1I). The endotoxin in VP4∗ proteins was further removed by Detoxi-Gel endotoxin removing columns, and the endotoxin level in VP4∗ proteins were lower than 20 EU/mg as analyzed by limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL).

Figure 1.

Purification and characterization of VP4∗ proteins

(A) SDS-PAGE analysis of VP4∗ proteins of P[4], P[6], and P[8] genotype rotaviruses.

(B) Western blot analysis of VP4∗ proteins using a broadly reactive mAb 9C4.

(C) Native PAGE analysis of VP4∗ proteins.

(D–F) HPSEC analysis of VP4∗ proteins using G3000PWXL.

(G–I) DSC analysis of VP4∗ proteins.

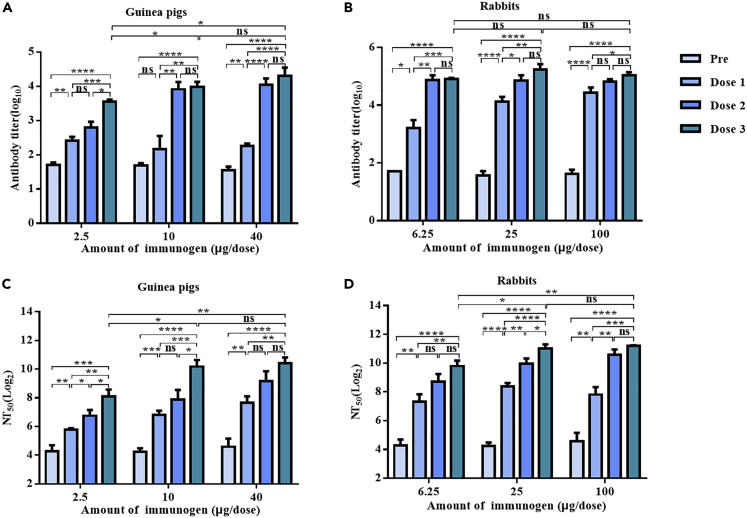

Dose-dependent immunogenicity of P[8]-VP4∗

To evaluate the immunogenicity and optimal immunization dose of VP4∗ proteins, guinea pigs and rabbits were immunized intramuscularly with different amount of P[8]-VP4∗ proteins formulated with aluminum adjuvant for three doses. In both guinea pigs and rabbits, homotypic VP4∗-specific binding antibody (IgG) and neutralizing antibody (nAb) titers were detectable after the first dose of immunization (Figure 2). The antibody titers and nAb titers increased after the second and third immunization in the low dose group; while in the high dose group, no significant difference was observed after the second and third immunization (Figure 2). After three doses of immunization, the nAb titers reached 271 (100–550), 1153 (289–2660), and 1375 (566–2277) in low-, middle-, and high-dose groups in guinea pigs (Figure 2C). In rabbits, the neutralizing antibody titers reached to 888 (400–1768), 2099 (1107–3547), and 2336 (2151–2630) in low-, middle-, and high-dose groups, respectively (Figure 2D). The nAb titers in the low dose groups were significantly lower than those in high-dose groups, while there was no significant difference in the neutralizing antibody titers between the middle- and high-dose groups in both guinea pigs and rabbits (Figures 2C and 2D). Thus, 10 and 25 μg per dose was selected for guinea pigs and rabbits in the following studies.

Figure 2.

Dose-dependent immunogenicity study of P[8]-VP4∗ in guinea pigs and rabbits

The guinea pigs and rabbits were immunized intramuscularly (IM) with VP4∗ proteins formulated in aluminum adjuvant for three times with 2-week interval. The serum samples were collected individually from the guinea pigs and rabbits before immunization and 2 weeks after each dose of immunization.

(A) Antibody titers against P[8]-VP4∗ in guinea pig sera.

(B) Antibody titers against P[8]-VP4∗ in rabbit sera.

(C) Neutralizing antibody titers against human rotavirus of Wa in guinea pig sera.

(D) Neutralizing antibody titers against human rotavirus Wa in rabbit sera. The bars represent mean and standard error of the means in each group (n = 5). ∗, ∗∗, ∗∗∗, ∗∗∗∗ represents p < 0.05, 0.005, 0.0005, 0.0001; ns represents p > 0.05.

The Immunogenicity of VP4-P[8], VP4-P[4], and VP4-P[6] in guinea pigs and rabbits.

To evaluate the immunogenicity of rotavirus VP4∗ proteins of P[4], P[6], and P[8] rotavirus, guinea pigs and rabbits were immunized with 10 or 25 μg VP4∗ proteins for three doses, respectively. After three doses of immunization, P[4]-, P[6]-, and P[8]-VP4∗ proteins all stimulated robust antibody responses in guinea pigs and rabbits (Figure 3). In guinea pigs, the GMT of nAbs after three dose of immunization was 694, 1363, and 4852 for P[4]-, P[6]-, and P[8]-VP4∗ proteins, respectively (Figure 3C); while in rabbits, the GMT of nAbs was 1520, 2714, and 4768, respectively (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

The immunogenicity of VP4∗ in guinea pigs and rabbits

The guinea pigs and rabbits were immunized intramuscularly (IM) with VP4∗ proteins formulated in aluminum adjuvant for three times with 2-week interval. The serum samples were collected individually from the guinea pigs and rabbits before immunization and 2 weeks after each dose of immunization.

(A–D) (A) The antibody titers in serum of guinea pigs, (B) the antibody titers in the serum of rabbits, (C) the neutralizing antibody titers in serum of guinea pigs, (D) the neutralizing antibody titers in serum of rabbits. Rotavirus Wa (G1P[8]), DS-1 (G2P[4]), and VR-2104 (G3P[6]) were used for detecting the homotypic neutralizing antibodies stimulated by P[4]-, P[6]-, and P[8]-VP4∗ proteins, respectively. The bars represent mean and standard error of the means in each group (n = 5). ∗, ∗∗, ∗∗∗, ∗∗∗∗ represents p < 0.05, 0.005, 0.0005, 0.0001; ns represents p > 0.05.

The heterotypic neutralizing antibody responses induced by VP4∗ proteins

To evaluate whether VP4∗ proteins could stimulate heterotypic nAbs, the nAb levels of the serum samples to heterotypic G or P genotype rotaviruses were determined. P[8], P[6], and P[4] genotype VP4∗ proteins all stimulated nAbs against the heterotypic rotaviruses (Figure 4 and S1). For DS-1, P[8]-VP4∗ stimulated similar titers of nAbs compared to the homotypic P[4]-VP4∗ (Figure 4). However, for both P[8] and P[6] rotaviruses, the neutralizing antibody levels stimulated by a heterotypic P genotype VP4∗ were significantly lower than those stimulated by homotypic VP4∗ proteins in guinea pigs (Figure 4A). Thus, bivalent or trivalent vaccines based on VP4∗ should be developed to stimulate protection against most prevalent human rotaviruses. In addition, the differences in guinea pigs were higher than that in rabbits, so the immunogenicity of bivalent and trivalent vaccines was evaluated in guinea pigs.

Figure 4.

The cross-neutralizing antibodies against different rotavirus induced by P[8]-VP4∗ in guinea pigs and rabbits

The neutralizing activity of serum samples after three doses of immunization described in Figure 3 against different rotaviruses were determined.

(A and B) (A) The cross-neutralizing antibodies in the serum of guinea pigs after 3 doses immunization, (B) the cross-neutralizing antibodies in the serum of rabbits after 3 doses immunization. The serum was collected to detected neutralizing antibodies against homotypic rotavirus and heterotypic with ELISpot. The bars represent mean and standard error of the means in each group (n = 5). ∗, ∗∗, ∗∗∗, ∗∗∗∗ represents p < 0.05, 0.005, 0.0005, and 0.0001, respectively; ns represents p > 0.05.

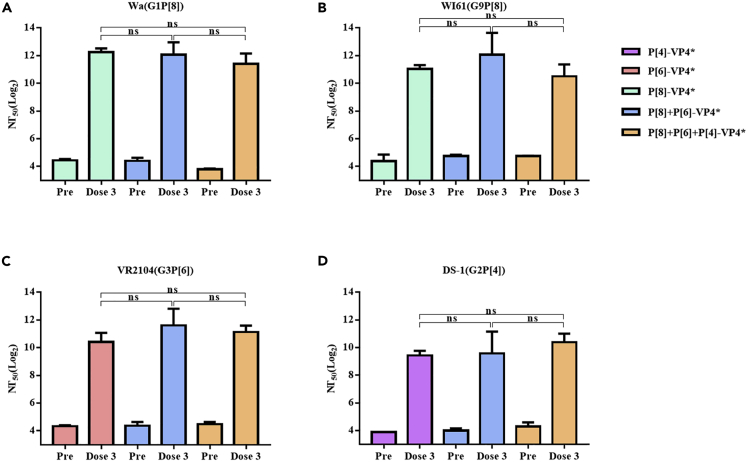

Bivalent VP4∗ stimulates protective antibodies against common human rotaviruses

Considering the fact that P[8] was the most prevalent P genotypes and P[8]-VP4∗ stimulated higher titers of neutralizing antibodies against P[8] rotaviruses, the bivalent vaccine was composed of P[8]-VP4∗ and P[6]-VP4∗. Guinea pigs were immunized with the bivalent and trivalent vaccines using the same dose and schedule as the monovalent vaccines. After 3 doses of immunization, the neutralizing activity of the serum samples from guinea pigs against different G and P genotype rotaviruses was determined. Both bivalent and trivalent vaccines stimulated high levels of nAbs against the rotaviruses tested. In addition, for all the rotaviruses tested, bivalent and trivalent vaccines stimulated similar levels of nAbs compared to the monovalent homotypic VP4∗. There was no significant difference between the bivalent vaccine and trivalent vaccine for the nAbs against all the rotaviruses tested (Figure 5). Thus, a bivalent vaccine based on VP4∗ could stimulate protective immunity against most of the prevalent rotaviruses.

Figure 5.

Cross-neutralizing antibodies detected by ELISpot for the serum of guinea pigs immunized with monovalent, bivalent, and trivalent vaccine

(A–D) the neutralizing antibodies against different genotype rotavirus in the serum of guinea pigs immunized three doses of monovalent, bivalent, or trivalent VP4∗ proteins. The bivalent and trivalent VP4∗ formulations include 10 μg VP4∗ proteins of each P genotype. The bars represent mean and standard error of the means in each group (n = 5). ∗, ∗∗, ∗∗∗, ∗∗∗∗ represents p < 0.05, 0.005, 0.0005, and 0.0001, respectively; ns represents p > 0.05.

Discussion

In this study, the truncated VP4∗ of human rotavirus P[4], P[6], and P[8] genotypes were expressed and all of the VP4∗ proteins can stimulate high level of neutralizing antibodies. It was found that a bivalent VP4∗-based vaccine (P[8]+P[6]) can stimulate protective antibodies against rotaviruses of common G and P genotypes. The results in this study are encouraging and suggest that the bivalent VP4∗ could be a viable vaccine candidate for further development.

The spike protein VP4 mediates the attachment and penetration of rotaviruses, and was widely explored as candidate antigens for rotavirus vaccines (Dunn et al., 1995; Jia et al., 2017; Li et al., 2010, 2018; Wen et al., 2012). VP4 could be enzymatically cleaved into VP8∗ and VP5∗ by trypsin, which enhances the infectivity of rotavirus (Clark et al., 1981). Both VP8∗ and VP5∗ can stimulate neutralizing antibodies, however, most rotavirus vaccines based on the hemagglutinin domain of VP8 (ΔVP8) (Mohanty et al., 2018; Ramesh et al., 2019; Wen et al., 2012; Xue et al., 2015). There were several reasons for the focus on VP8. First, VP8∗ binds to the cell surface receptors, and antibodies specific for VP8 could inhibit the first step of rotavirus infection (Ruggeri and Greenberg, 1991); second, the immunogenicity of VP8∗ was higher than VP5∗(Padillanoriega et al., 1992); third, ΔVP8 could be expressed in soluble from in high level that the production process should be simple and the cost should be low (Kovacs-Nolan et al., 2001; Kraschnefski et al., 2005).

In our previous studies, we also explored truncated VP8 as the candidate antigen for rotavirus antigen, and found that the N-terminus (aa26-64) was critical for VP8 to stimulate neutralizing antibodies (Xue et al., 2015); however, the immunogenicity of VP8 was not high enough when formulated in aluminum adjuvant (Xue et al., 2016). Later, we found that the truncated VP4 (VP4∗), which contains both VP8 (aa26-231) and VP5 antigen domain, could be a more viable candidate for rotavirus vaccine. VP4∗ stimulated significantly higher immune responses than VP8∗ and VP5∗ alone, and conferred higher protective efficacy in mice (Li et al., 2018). In the early studies, Dunn et al. also found that the full-length VP4 was more efficient than VP8∗ and VP5 (1)∗ in generating protective immunity (Dunn et al., 1995), and the antibodies against VP5 (1)∗ were more effective than antibodies against VP8∗. Moreover, most of the heterotypic neutralizing antibodies are specific for VP5 (Nair et al., 2017). Compared to VP8, the sequences of VP5 were more conserved, and inclusion of VP5 antigen in the vaccine candidate may stimulate higher heterotypic protection.

Rotaviruses can be classified into different G and P genotypes based on the sequences of VP7 and VP4, respectively (Desselberger, 2014). Globally, G1, G2, G3, G4, G9, and G12 are the most common G genotypes, while P[8], P[4], and P[6] are the most dominant P genotypes (Doro et al., 2014). Due to the variable efficacy of monovalent rotavirus vaccines based on animal rotaviruses (Lanata et al., 1996), multivalent reassortant vaccines were developed. In the development of reassortant rotavirus vaccines, G genotypes were more concerned, which could be due to that VP7 was the dominant immunogen for production of neutralizing antibodies after intestinal infection (Ward et al., 1990). The reassortants contain a G1 to G4 VP7 in Rotateq and G1-G4 and G9 VP7 in Rotasiil. Two monovalent rotavirus vaccines based on human rotavirus, Rotarix (G1P[8]) and Rotavac (G9P[11]), have been prequalified by WHO, and proven to be effective (Bernstein and Ward, 2006; Bhandari et al., 2014). However, in recent years, it was found that G2P[4] became the dominant genotypes in countries where Rotarix was implemented in the immunization schedule (Gurgel et al., 2007). Compared to the G genotype, the P genotype of rotavirus infecting humans is mainly P[8], P[4], and P[6], and these three P genotypes accounted for more than 95% (Doro et al., 2014). These results suggest that a rotavirus vaccine with P[8], P[4], and P[6] genotype can induce the protection against most common genotypes of rotaviruses. The most advanced non-replicating rotavirus vaccine was the trivalent vaccine based on VP8 (P[4], P[6], and P[8]).

Due to the host restriction of rotaviruses, animal rotavirus VP4∗ proteins were expressed and evaluated in our previous studies. We demonstrated the protective efficacy of animal rotavirus VP4∗ immunization against rotavirus infection and diarrhea in mice (Li et al., 2018). In this study, we found that human rotavirus VP4∗ (aa26-476) can also be expressed in soluble form in E.coli and stimulate high titers of neutralizing antibodies in both guinea pigs and rabbits, though one more amino acid was expressed compared to the animal rotavirus VP4∗ (aa26-476) after alignment. P[8]-VP4∗ and P[4]-VP4∗ stimulated similar levels of neutralizing antibodies to rotavirus DS-1 (G2P[4]) (Figure 4). This is consistent with the fact that P[8] and P[4] rotaviruses belong to the same serotype (P1) (Desselberger, 2014). In previous studies, Wen et al. also found that P[4]-VP8 stimulated heterotypic antibodies to P[8]-VP8 and can neutralize rotavirus Wa (G1P[8]) (Wen et al., 2012). In addition, bivalent VP4∗ (P[8] and P[6]) could stimulate similar levels of neutralizing antibodies compared to the trivalent VP4∗ (Figure 5). Thus, bivalent VP4∗ could be considered as a viable vaccine candidate. Compared to a trivalent vaccine, the total dose of VP4∗ antigens in bivalent vaccine should be lower, and the safety would be higher.

Limitations of the study

This study is a step forward toward the development of VP4∗-based recombinant rotavirus vaccines. However, more work still needs to be done. First, only one P[4] and P[6] rotavirus was evaluated in this study, the neutralizing activity against more rotaviruses, especially the dominant viruses in recent years should be evaluated. Second, the immunogenicity of the bivalent and trivalent VP4∗ proteins was only evaluated in guinea pigs in this study. The immunogenicity and protective efficacy against rotavirus diarrhea and shedding should be evaluated in large animals, such as pigs or monkeys in further study. In summary, the truncated VP4∗ of human rotavirus could stimulate high titers of neutralizing antibodies in both guinea pigs and rabbits when formulated with aluminum adjuvant. Bivalent VP4∗ could be a viable candidate vaccine against common human rotaviruses.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| 9C4-HRP | This paper | N/A |

| 2A9-HRP | This paper | N/A |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Wa strains Rotavirus | This paper | N/A |

| WI61 strains Rotavirus | This paper | N/A |

| DS-1 strains Rotavirus | This paper | N/A |

| VR2104 strains Rotavirus | This paper | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| P[8]-VP4∗ protein | This paper | N/A |

| P[6]-VP4∗ protein | This paper | N/A |

| P[4]-VP4∗ protein | This paper | N/A |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Goat polyclonal Secondary Antibody to Guinea pig IgG - H&L (HRP) | Abcam | Cat# ab6908 |

| Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (HRP) | Abcam | Cat# ab6721 |

| Butyl Sepharose 4 Fast Flow | GE | Cat# 17,098,001 |

| Phenyl Sepharose High Performance | GE | Cat# 17-1082-03 |

| Q Sepharose high performance | GE | Cat# 17-1014-03 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| MA104 | ATCC | ATCC CRL2378.1 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pTO-T7-P[8]-VP4∗ | This paper | N/A |

| pTO-T7-P[6]-VP4∗ | This paper | N/A |

| pTO-T7-P[4]-VP4∗ | This paper | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism (version 8.0.1) | Graphpad | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

| Origin 7 | OriginLab | https://www.originlab.com/ |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by Prof. Shengxiang Ge (sxge@xmu.edu.cn).

Materials availability

All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the Lead Contact with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Experimental model and subject details

Cell and viruses

MA104 cells (ATCC® CRL2378.1, Washington, USA) were grown in DMEM media with 10% FBS, cultured at 37°C, 5% CO2. Human rotavirus strains Wa(G1P[8]), WI61(G9P[8]), DS-1(G2P[4]), VR2104(G3P[6]) were purchased from ATCC and cultured in MA104 cells. The infectious titers of the viruses were determined by an enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISpot) assay as described previously (Li et al., 2014a).

Ethics statement

All experiments were conducted according to the guidelines of laboratory animals of China and the protocol was approved by Xiamen University Laboratory Animal Center.

Animals

Famale guinea pigs weighing 450–500g and female rabbits weighing 2 kg were purchased from Shanghai Songlian Experimental Animal Farm (Shanghai, China) and feed in Xiamen University Laboratory Animal Center.

Method details

Protein expression and purification

The expression and purification of VP4∗ was described previously (Li et al., 2022). In briefly, the genes encoding P[4]-, P[6]- and P[8]-VP4∗ were cloned into pTO-T7 and the proteins were expressed in E.coli BL21(DE3) in the soluble form. The bacteria were harvested by centrifugation and the pellets were resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH = 8.0). The VP4 proteins were purified from the supernatant by anion exchange chromatography in combination with hydrophobic interaction chromatography. The purity of the VP4∗ was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and the concentration was determined by BCA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The endotoxin was further removed by Detoxi-Gel Endotoxin Removing Columns (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The endotoxin level was measured using limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL, Fuzhou XinBei Biochemical Industrial Co.,Ltd. Fujian, China).

Western blot

The identity of VP4∗ was analyzed by western blot as follows: the P[8], P[6], P[4]-VP4∗ proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, then transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking, the membrane was incubated at 37°C with 1:2000 diluted horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-VP4 antibody 9C4 (9C4-HRP) for 1 h. The broadly reactive antibody 9C4 was screened in our previous studies using hybridoma technology, and the mouse were immunized with his-tagged VP4∗ proteins. Finally, the Western Bright™ ECL substrate (Advansta, Menlo Park, CA) was add to the membrane following five times washing with Phosphate Buffered Saline-Tween (PBST). The membrane was imaged immediately with ImageQuant LAS4000 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA).

Analytical high-performance size exclusion chromatography (HPSEC)

The homogeneity of VP4 proteins was determined by HPSEC using Waters e2695 HPLC system (Waters, Milford, MA) with an analytical TSK Gel G3000PWXL (TOSOH, Tokyo, Japan) as described previously (Li et al., 2018). Briefly, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH8.8) was used as elution buffer, and the flow rate was maintained at 0.5 mL/min. The absorbance at 280 nm was monitored for 30 min to detect the protein in the eluent.

Analytical differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

Microcal VP capillary DSC (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) was used to evaluate the thermostability of VP4∗ proteins according to the protocol described previously (Li et al., 2014c). In brief, all samples were diluted to 0.2 mg/mL and measured at a scan rate of 1 °C/min with the scan temperature from 15°C to 90°C.

Immunizations of Guinea pigs and rabbits

Before immunization, the proteins were mixed with aluminum adjuvant at a ratio of 1:1 (v/v) at 4°C for 4 h. The guinea pigs and rabbits were immunized intramuscularly (IM) with VP4∗ proteins formulated in aluminum adjuvant for three times with 2-week interval. Five animals were immunized in each group. The serum samples were collected individually from the guinea pigs and rabbits before immunization and 2 weeks after each dose of immunization.

Antibody titer detection

Indirect binding enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) was performed to detect the antibody titers in the sera of guinea pigs and rabbits immunized with the VP4 proteins. The protocol is similar to that previously reported (Xue et al., 2016). In brief, 96 well microtiter plates were coated with 500 ng/mL of VP4∗ proteins (100 μL/well) at 4°C overnight. After blocking, the serum samples were 10-fold serially diluted and added to the precoated microplates (100 μL/well), and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. After washing, Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated goat anti-guinea pig IgG antibody (abcam, 1:5000) or goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (abcam, 1:5000) was added and incubated at 37°C for 30 another minutes. After color development and termination, the absorbance at 450 and 630 nm were detected using a microplate reader (PHOmo, AutoBio, Zhengzhou, China). For each serum sample, the dilution with an OD450/630 between 0.2 and 3.0 was used to calculate the antibody titer, and the antibody titers were calculated using the following formula: dilution fold ∗ OD450/630/0.1.

Virus neutralization assay

The neutralizing antibodies titer in sera from guinea pigs and rabbits immunized with the VP4∗ proteins was detected by Enzyme-linked Immunospot (ELISpot) assay as previously described (Li et al., 2014b). Briefly, the serum samples were diluted at 2-fold serially after inactivation at 56°C for 30 min, and incubation with equal volume of indicated rotavirus at 37°C for 1 h; Then, 100 μL of each serum-rotavirus mixture was added to MA104 cells in 96-well cell culture microplates. After 14 h of incubation, the reductions in rotavirus infectivity by serum were measured by ELISPOT and the inhibition rate was calculated by the following formula: 100 x [1 - (average number of spots in experiment wells/average number of spots in control wells)]. The 50% neutralization titer (NT50) was automatically plotted by nonlinear regression using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, Inc. San Diego, CA).

Quantification and statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism™ version 7.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc. San Diego, CA) was used for data analysis. The experimental results are expressed as mean ±standard errors of mean after log2 or log10 transformation. Significant differences between 2 groups were determined using two-way ANOVA. p < 0.05 was considered as significant difference.

Additional resources

None.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82171816 and 81974260) and the Key Program of Science and Technology of Fujian Province (2020YZ015004).

Author contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, T.L., S.G., and N.X.; investigation, G.L., Y.Z., H.Y., Y.L., L.Y., C.L., and F.S.; Formal Analysis, G.L.; Visualization: G.L., T.L., and S.Z.; writing – original draft, G.L.; writing – review and editing, T.L. and S.G.; supervision, J.Z. and N.X.; funding acquisition, T.L. and J.Z.

Declaration of interests

Y.Z., Y.L., T.L., S.G., J.Z., and N.X. declared that they have applied related patent, all other authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Published: October 21, 2022

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2022.105099.

Contributor Information

Tingdong Li, Email: litingdong@xmu.edu.cn.

Shengxiang Ge, Email: sxge@xmu.edu.cn.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon reasonable request. Original code is not reported in this paper. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- AuthorAnonymous Rotavirus vaccines WHO position paper: January 2013 - Recommendations. Vaccine. 2013;31:6170–6171. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afchangi A., Jalilvand S., Mohajel N., Marashi S.M., Shoja Z. Rotavirus VP6 as a potential vaccine candidate. Rev. Med. Virol. 2019;29:e2027. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armah G.E., Sow S.O., Breiman R.F., Dallas M.J., Tapia M.D., Feikin D.R., Binka F.N., Steele A.D., Laserson K.F., Ansah N.A., et al. Efficacy of pentavalent rotavirus vaccine against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis in infants in developing countries in sub-Saharan Africa: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:606–614. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60889-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo M.P., Vlasova A.N., Saif L.J. Human rotavirus virus-like particle vaccines evaluated in a neonatal gnotobiotic pig model of human rotavirus disease. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2013;12:169–181. doi: 10.1586/erv.13.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein D.I., Ward R.L. Rotarix: development of a live attenuated monovalent human rotavirus vaccine. Pediatr. Ann. 2006;35:38–43. doi: 10.3928/0090-4481-20060101-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari N., Rongsen-Chandola T., Bavdekar A., John J., Antony K., Taneja S., Goyal N., Kawade A., Kang G., Rathore S.S., et al. Efficacy of a monovalent human-bovine (116E) rotavirus vaccine in Indian infants: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:2136–2143. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62630-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changotra H., Vij A. Rotavirus virus-like particles (RV-VLPs) vaccines: an update. Rev. Med. Virol. 2017;27:e1954. doi: 10.1002/rmv.1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark A., van Zandvoort K., Flasche S., Sanderson C., Bines J., Tate J., Parashar U., Jit M. Efficacy of live oral rotavirus vaccines by duration of follow-up: a meta-regression of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019;19:717–727. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30126-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark S.M., Roth J.R., Clark M.L., Barnett B.B., Spendlove R.S. Trypsin enhancement of rotavirus infectivity - mechanism of enhancement. J. Virol. 1981;39:816–822. doi: 10.1128/jvi.39.3.816-822.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulson B.S. Expanding diversity of glycan receptor usage by rotaviruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2015:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2015.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desselberger U. Rotaviruses. Virus Res. 2014;190:75–96. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dóró R., László B., Martella V., Leshem E., Gentsch J., Parashar U., Bányai K. Review of global rotavirus strain prevalence data from six years post vaccine licensure surveillance: is there evidence of strain selection from vaccine pressure? Infect. Genet. Evol. 2014;28:446–461. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn S.J., Fiore L., Werner R.L., Cross T.L., Broome R.L., Ruggeri F.M., Greenberg H.B. Immunogenicity, antigenicity, and protection efficacy of baculovirus-expressed Vp4 trypsin cleavage products, Vp5(1) and Vp8 from rhesus rotavirus. Arch. Virol. 1995;140:1969–1978. doi: 10.1007/BF01322686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faris L. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specifi c mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet. 2018;388 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groome M.J., Fairlie L., Morrison J., Fix A., Koen A., Masenya M., Jose L., Madhi S.A., Page N., McNeal M., et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a parenteral trivalent P2-VP8 subunit rotavirus vaccine: a multisite, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:851–863. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30001-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groome M.J., Koen A., Fix A., Page N., Jose L., Madhi S.A., McNeal M., Dally L., Cho I., Power M., et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a parenteral P2-VP8-P[8] subunit rotavirus vaccine in toddlers and infants in South Africa: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017;17:843–853. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30242-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S., Chaudhary S., Bubber P., Ray P. Epidemiology and genetic diversity of group A rotavirus in acute diarrhea patients in pre-vaccination era in Himachal Pradesh, India. Vaccine. 2019;37:5350–5356. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurgel R.Q., Cuevas L.E., Vieira S.C.F., Barros V.C.F., Fontes P.B., Salustino E.F., Nakagomi O., Nakagomi T., Dove W., Cunliffe N., Hart C.A. Predominance of rotavirus P[4]G2 in a vaccinated population, Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007;13:1571–1573. doi: 10.3201/eid1310.070412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isanaka S., Guindo O., Langendorf C., Matar Seck A., Plikaytis B.D., Sayinzoga-Makombe N., McNeal M.M., Meyer N., Adehossi E., Djibo A. Efficacy of a low-cost, heat-stable oral rotavirus vaccine in Niger. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;376:1121–1130. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1609462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L., Li T., Ge S. [Research progress in rotavirus VP4 subunit vaccine] Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao. 2017;33:1075–1084. doi: 10.13345/j.cjb.160480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang B., Gentsch J.R., Glass R.I. Inactivated rotavirus vaccines: a priority for accelerated vaccine development. Vaccine. 2008;26:6754–6758. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodabandehloo M., Shahrabadi M.S., Keyvani H., Bambai B., Sadigh Z. Recombinant outer capsid Glycoprotein (VP7) of rotavirus expressed in insect cells induces neutralizing antibodies in rabbits. Iran. J. Public Health. 2012;41:73–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim A.H., Armah G., Dennis F., Wang L., Rodgers R., Droit L., Baldridge M.T., Handley S.A., Harris V.C. Enteric virome negatively affects seroconversion following oral rotavirus vaccination in a sampled cohort of Ghanaian infants. Cell Host Microbe. 2022;30:110–123.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2021.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotloff K.L., Nataro J.P., Blackwelder W.C., Nasrin D., Farag T.H., Panchalingam S., Wu Y., Sow S.O., Sur D., Breiman R.F., et al. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. Lancet. 2013;382:209–222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60844-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs-Nolan J., Sasaki E., Yoo D., Mine Y. Cloning and expression of human rotavirus spike protein, VP8∗, in Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;282:1183–1188. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraschnefski M.J., Scott S.A., Holloway G., Coulson B.S., von Itzstein M., Blanchard H. Cloning, expression, purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis of the VP8∗ carbohydrate-binding protein of the human rotavirus strain Wa. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 2005;61:989–993. doi: 10.1107/S1744309105032999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni P.S., Desai S., Tewari T., Kawade A., Goyal N., Garg B.S., Kumar D., Kanungo S., Kamat V., Kang G., et al. A randomized Phase III clinical trial to assess the efficacy of a bovine-human reassortant pentavalent rotavirus vaccine in Indian infants. Vaccine. 2017;35:6228–6237. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanata C.F., Fischer-Walker C.L., Olascoaga A.C., Torres C.X., Aryee M.J., Black R.E., Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group of the World Health Organization and UNICEF Global causes of diarrheal disease mortality in children <5 years of age: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8:e72788. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanata C.F., Midthun K., Black R.E., Butron B., Huapaya A., Penny M.E., Ventura G., Gil A., Jett-Goheen M., Davidson B.L. Safety, immunogenicity, and protective efficacy of one and three doses of the tetravalent rhesus rotavirus vaccine in infants in Lima, Peru. J. Infect. Dis. 1996;174:268–275. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.2.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Luo G., Zeng Y., Song F., Yang H., Zhang S., Wang Y., Li T., Ge S., Xia N. Establishment of sandwich ELISA for quality control in rotavirus vaccine production. Vaccines. 2022;10:243. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10020243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Lin H., Yu L., Xue M., Ge S., Zhao Q., Zhang J., Xia N. Development of an enzyme-linked immunospot assay for determination of rotavirus infectivity. J. Virol. Methods. 2014;209:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Lin H., Yu L., Xue M., Ge S., Zhao Q., Zhang J., Xia N. Development of an enzyme-linked immunospot (elispot) assay for determination of rotavirus infectivity. J. Virol. Methods. 2014;209:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Lin H., Zhang Y., Li M., Wang D., Che Y., Zhu Y., Li S., Zhang J., Ge S., et al. Improved characteristics and protective efficacy in an animal model of E. coli-derived recombinant double-layered rotavirus virus-like particles. Vaccine. 2014;32:1921–1931. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Xue M., Yu L., Luo G., Yang H., Jia L., Zeng Y., Li T., Ge S., Xia N. Expression and characterization of a novel truncated rotavirus VP4 for the development of a recombinant rotavirus vaccine. Vaccine. 2018;36:2086–2092. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.J., Ma G.P., Li G.W., Qiao X.Y., Ge J.W., Tang L.J., Liu M., Liu L.W. Oral vaccination with the porcine rotavirus VP4 outer capsid protein expressed by Lactococcus lactis induces specific antibody production. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010;2010:708460. doi: 10.1155/2010/708460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Huang P., Zhao D., Xia M., Zhong W., Jiang X., Tan M. Effects of rotavirus NSP4 protein on the immune response and protection of the S-R69A-VP8∗nanoparticle rotavirus vaccine. Vaccine. 2021;39:263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty E., Dehury B., Satapathy A.K., Dwibedi B. Design and testing of a highly conserved human rotavirus VP8∗ immunogenic peptide with potential for vaccine development. J. Biotechnol. 2018;281:48–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2018.06.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair N., Feng N., Blum L.K., Sanyal M., Ding S., Jiang B., Sen A., Morton J.M., He X.S., Robinson W.H., Greenberg H.B. VP4-and VP7-specific antibodies mediate heterotypic immunity to rotavirus in humans. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017;9:eaam5434. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aam5434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordgren J., Sharma S., Bucardo F., Nasir W., Günaydın G., Ouermi D., Nitiema L.M., Becker-Dreps S., Simpore J., Hammarström L., et al. Both Lewis and secretor status mediate susceptibility to rotavirus infections in a rotavirus genotype-dependent manner. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014;59:1567–1573. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Ryan M., Linhares A.C. Update on Rotarix: an oral human rotavirus vaccine. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2009;8:1627–1641. doi: 10.1586/erv.09.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padillanoriega L., Fiore L., Rennels M.B., Losonsky G.A., Mackow E.R., Greenberg H.B. Humoral immune-responses to Vp4 and its cleavage products Vp5-asterisk and Vp8-asterisk in infants vaccinated with rhesus rotavirus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1992;30:1392–1397. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.6.1392-1397.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker E.P., Ramani S., Lopman B.A., Church J.A., Iturriza-Gómara M., Prendergast A.J., Grassly N.C. Causes of impaired oral vaccine efficacy in developing countries. Future Microbiol. 2018;13:97–118. doi: 10.2217/fmb-2017-0128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh A., Mao J.D., Lei S.H., Twitchell E., Shiraz A., Jiang X., Tan M., Yuan L.J. Parenterally administered P24-VP8∗ nanoparticle vaccine conferred strong protection against rotavirus diarrhea and virus shedding in gnotobiotic pigs. Vaccines. 2019;7:177. doi: 10.3390/vaccines7040177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggeri F.M., Greenberg H.B. Antibodies to the trypsin cleavage peptide VP8 neutralize rotavirus by inhibiting binding of virions to target cells in culture. J. Virol. 1991;65:2211–2219. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2211-2219.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockman J.A. Effect of human rotavirus vaccine on severe diarrhea in african infants. Year Bk. Pediatr. 2011;2011:248–250. [Google Scholar]

- Trask S.D., McDonald S.M., Patton J.T. Structural insights into the coupling of virion assembly and rotavirus replication. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012;10:165–177. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward R.L., Knowlton D.R., Greenberg H.B., Schiff G.M., Bernstein D.I. Serum-neutralizing antibody to VP4 and VP7 proteins in infants following vaccination with WC3 bovine rotavirus. J. Virol. 1990;64:2687–2691. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.6.2687-2691.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen X., Cao D., Jones R.W., Li J., Szu S., Hoshino Y. Construction and characterization of human rotavirus recombinant VP8∗ subunit parenteral vaccine candidates. Vaccine. 2012;30:6121–6126. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.07.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Yi S., Zhang G., Mu G., Yin N., Mi K., Zhou Y., Xie Y., Xiao N., Li H., Sun M. Isolation, preparation, and assessment of the immunogenicity effectiveness of a novel inactivated rotavirus vaccine strain: ZTR-68, rotavirus A genotype G1P[8] Lancet. 2015;386:62. [Google Scholar]

- Xue M., Yu L., Che Y., Lin H., Zeng Y., Fang M., Li T., Ge S., Xia N. Characterization and protective efficacy in an animal model of a novel truncated rotavirus VP8 subunit parenteral vaccine candidate. Vaccine. 2015;33:2606–2613. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.03.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue M., Yu L., Jia L., Li Y., Zeng Y., Li T., Ge S., Xia N. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of rotavirus VP8∗ fused to cholera toxin B subunit in a mouse model. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2016;12:2959–2968. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1204501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaman K., Dang D.A., Victor J.C., Shin S., Yunus M., Dallas M.J., Podder G., Vu D.T., Le T.P.M., Luby S.P., et al. Efficacy of pentavalent rotavirus vaccine against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis in infants in developing countries in Asia: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:615–623. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60755-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon reasonable request. Original code is not reported in this paper. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.