Abstract

Background & Aims

It is unclear whether rs738409 (p.I148M) missense variant in patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 (PNPLA3) rs738409 promotes fibrosis development by triggering specific fibrogenic pathways or by creating an unfavorable microenvironment by promoting steatosis, inflammation, and ultimately fibrosis. We tested the hypothesis that intermediate histologic traits, including steatosis, lobular and portal inflammation, and ballooning may determine the effect of rs738409 on liver fibrosis among individuals with biopsy-proven NAFLD.

Approach and Results

Causal mediation models including multiple mediators in parallel or sequentially were performed to examine the effect of rs738409, by decomposing its total effect on fibrosis severity into direct and indirect effects, mediated by histology traits in 1153 Non-Hispanic White (NHW) patients. Total effect of rs738409 on fibrosis was β=0.19 (95% CI: 0.09–0.29). The direct effect of rs738409 on fibrosis upon removing mediators’ effects was β=0.09 (95% CI: 0.01–0.17) and the indirect effect of rs738409 on fibrosis through all mediators’ effects were β=0.010 (95% CI: 0.04–0.15). Among all mediators, the greatest estimated effect size was displayed by portal inflammation (β=0.09, 95% CI: 0.05–0.12). Among different sequential combinations of histology traits, the path including lobular inflammation followed by ballooning degeneration displayed the most significant indirect effect (β=0.023, 95% CI: 0.011–0.037). Mediation analysis in a separate group of 404 individuals with biopsy-proven NAFLD from other races and ethnicity showed similar results.

Conclusions

In NAFLD, nearly half of the total effect of the rs738409 G allele on fibrosis severity could be explained by a direct pathway, suggesting that rs738409 may promote fibrosis development by activating specific fibrogenic pathways. A large proportion of the indirect effect of rs738409 on fibrosis severity is mediated through portal inflammation.

Keywords: PNPLA3 rs738409, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, fibrosis, steatosis, portal inflammation, mediation analysis

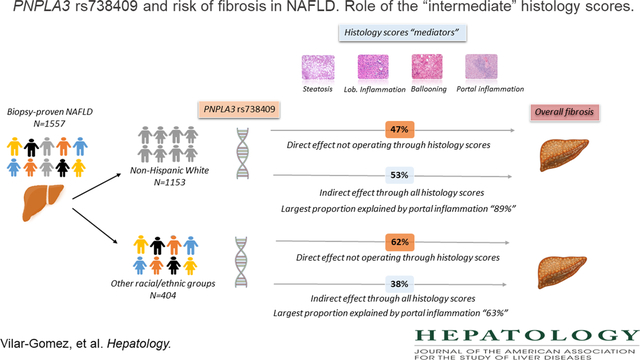

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The rs738409 (p.I148M) missense variant in patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 (PNPLA3) has consistently been associated with an increased risk of fatty liver, steatohepatitis, fibrosis, cancer, and liver-related mortality, and these associations are independent of body mass index (BMI), age, sex, and insulin resistance. (1–6) Despite the unquestionable association of rs738409 with NAFLD and its severity, the molecular mechanisms through which this variant may lead to hepatic advanced fibrosis remain unclear. There has been an intense debate on whether rs738409 promotes fibrosis development by triggering specific fibrogenic pathways or by creating a favorable microenvironment by promoting steatosis, inflammation, and ultimately fibrosis. (7) Some recent studies have shed light on the molecular and physiological implications of rs738409 in the liver. In-vitro studies have shown that the PNPLA3 protein has triacylglycerol hydrolase, acyltransferase, and transacylase activities, which promote lipid droplet remodeling in hepatocytes and hepatic stellate cells. (8, 9) The rs738409 has been associated with reduced fatty acid hydrolysis and impaired mobilization of triglycerides (TG), resulting in TG accumulation in the liver. (8–15)

The natural history of NAFLD is not uniform across the affected individuals, and the presence and the severity of intermediate histologic traits might explain partly the clinical phenotypic variability of the disease. (16–18) Hepatocellular ballooning is believed to be an important determinant of worse histologic phenotypes, including liver cirrhosis. (19) Likewise, the increased portal (20) and lobular inflammation (21) have been associated with an increased risk of progressive disease.

Here, we contrasted the hypothesis that intermediate histologic traits, including steatosis, lobular and portal inflammation, and hepatocyte ballooning degeneration may be determinants of the effect of rs738409 on liver fibrosis. Thus, we sought to test the model in which the rs738409 variant is the exposure variable and histologic steatosis, lobular and portal inflammation, ballooning are the mediators of the fibrosis severity as the outcome. To test this assumption, we used a causal mediation analysis that can quantify the proportion of direct or indirect (via histologic intermediate traits) exposure effects on the outcome of interest. Since other metabolic features may confound the relationship between rs738409 and all histology scores, all our mediation analyses were controlled for BMI, diabetes, and other relevant confounders.

Material and Methods

Study design and patient population

A detailed description of the study design and individuals included in this cross-sectional analysis has been published elsewhere. (22, 23) Briefly, adults ≥18 years with biopsy-confirmed NAFLD were prospectively recruited at 9 medical centers across the U.S. and enrolled in different studies conducted by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK)–sponsored Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network (NASH CRN) including NAFLD Adult Database 1, NAFLD Adult Database 2 (clinicaltrial.gov identifier: NCT01030484) and PIVENS (Pioglitazone vs Vitamin E vs Placebo for Treatment of Non-Diabetic Patients With Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis) (clinicaltrial.gov identifier: NCT00063622) and FLINT (The Farnesoid X Receptor Ligand Obeticholic Acid in NASH Treatment) (clinicaltrial.gov identifier: NCT01265498) trials. (24–26) After excluding participants with excessive alcohol consumption (>7 and >14 standard drinks per week for women and men, respectively), other causes of chronic liver disease, history of total parenteral nutrition, biliopancreatic diversion or bariatric surgery, short bowel syndrome, suspected or confirmed hepatocellular carcinoma, and positivity for HIV, our study population comprised 1557 individuals who had complete information on central review of liver histology and rs738409 genotyping through July 2019. All study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of each participating center, and all participants provided written informed consent. More details on our study design and participants can be found in the Supplemental Material.

Assessment and Definitions of Exposure, Mediator, Outcome, and Relevant Confounders

Exposure variable: the rs738409 variant

DNA samples from 1557 were analyzed; rs738409 was successfully genotyped in 100% of the samples. All samples were blindly duplicated to assess the reproducibility of the genotype, and reproducibility of 100% was obtained. The association between rs738409 and mediators/outcome was explored using an additive model (CC, CG, GG) of inheritance. A description of the rs738409 genotyping method is available in the Supplemental Material.

Mediators and Outcome variables: Liver histology scores

All liver biopsies were centrally read in a blinded fashion by the pathology committee of the NASH CRN as described previously. (27) NAFLD was defined as ≥5% of hepatocytes containing macrovesicular fat. Liver histology reports were based on the NASH CRN Scoring System, which assesses the severity of steatosis (0–3), lobular inflammation (0–2), hepatocyte ballooning degeneration (0–2), portal inflammation (0–2), and fibrosis (0–4). (27, 28) Fibrosis severity was considered the outcome of interest, whereas steatosis, lobular inflammation, hepatocyte ballooning degeneration, and portal inflammation were considered the mediators.

Statistical analysis

Before testing for mediation, potential correlations, and collinear effects between potential mediators (steatosis, lobular inflammation, hepatocyte ballooning degeneration, and portal inflammation) and fibrosis severity were checked using the multivariable linear regression models. The tolerance and the variance inflation factor (VIF), two collinearity diagnostic factors, were used to identify multicollinearity between mediators and the outcome. A small tolerance value, typically less than 0.1, might suggest strong multicollinearity. Although there is no formal VIF value for determining the presence of multicollinearity, VIF values that exceed 2.5 are often regarded as indicating multicollinearity. (29, 30)

Two different mediation models including either multiple mediators in parallel or sequentially were conducted to examine the effect of rs738409, by decomposing its total effect on fibrosis severity into direct and indirect effects, mediated by steatosis, lobular inflammation, ballooning, and portal inflammation. Regarding the analysis examining the effect of including mediators sequentially, we considered the inclusion of up to two consecutive histology traits (ie., steatosis → lobular inflammation, steatosis → ballooning, lobular inflammation → ballooning, etc.) The inclusion of 3 or more sequential traits did not improve model predictions (results are not shown). Overall, a mediation model displays 3 main types of path-specific estimates: 1) direct effect (represents the direct effect of rs738409 on fibrosis score, not operating through mediators “steatosis, lobular and portal inflammation and ballooning degeneration scores”), 2) indirect effect (represents the effect of rs738409 on fibrosis score that operates through mediators), 3) total effect (represents the sum of direct and indirect effects of rs738409 on fibrosis score). (31) Since age, gender, BMI, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), non-heavy alcohol intake, and other genetic variants (HSD17B13 rs72613567, TM6SF2 rs58542926, MBOAT7 rs641738) may be significantly associated with both the mediators and the outcome, all mediation analyses were adjusted by these relevant confounding factors.

Standardized regression coefficients express effect size measurements for total, direct, and indirect paths. Statistical significance for the total, natural direct, and natural indirect effects of rs738409 genotypes on fibrosis scores were determined using 95% bootstrap bias-corrected confidence intervals (CIs) based on 10,000 bootstrap samples. (32, 33) If the 95% bias-corrected CIs do not contain zero, the associations are considered significant. No missing observations were handled in our analyses. The mediation effects were estimated by linear regression-based mediation using the PROCESS macro, version 4.0, models 4 (parallel mediation) or 6 (sequential mediation), in SPSS (Version 27; Chicago, IL, USA). (33) The acyclic graphic or causal diagram (Suppl. Figure 1) shows our hypothesized associations between exposure, mediators, outcome, and relevant confounders. In the diagram, the indirect “mediation” effect is represented by the path from exposure to the outcome via the mediator (path a x path b). It expresses the fraction of the exposure effect that is mediated through a specific mediator. Mediation effects can be either positive or negative, depending on the signs of the a and b effects. When a is positive and b is negative, the mediation effect becomes negative. Path c represents the direct effect whereas the total effect is c’ (c + a x b). Additional details regarding our mediation models are given in the Supplemental Material.

Because our study population mostly comprised non-Hispanic (NH) White participants, the main analysis was performed in this ethnic group. However, to reproduce our results, a sensitivity analysis was conducted in a cohort including other races and ethnicities (n=404). A description of our selected cohort of NH-White has been previously published. (22, 23)

Monte Carlo power analyses as recommended by Schoemann et al. (34) with 10,000 repetitions, 20,000 Monte Carlo draws, and a 95% confidence interval, indicated 400 participants were needed to achieve between 0.79 and 0.84 statistical powers to detect a significant indirect effect in our model including 4 mediators in parallel. More details are given in Supplemental Material.

Data availability statement

Data used in this study are deposited to the data coordinating center of the Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network. Data can be made available by submitting a request to the NASH CRN data coordinating center, at https://jhuccs1.us/nash/ in compliance with its data-sharing policies and procedures.

Results

Most of the participants were NH-White (n=1153, 74%), followed by Hispanic (n=156, 10%), NH-Asian (n=106, 7%), NH-Black (n=52, 3%) and other or multiracial (n=90, 6%). Among all participants, rs738409 genotypes were distributed as follows: CC (n=490, 31%), CG (n=680, 44%) and GG (n=387, n=25%). The average age and BMI were 48.5 years (SD=11.5) and 34.4 kg/m2 (SD=6.4) with 64% (n= 989) being female, 36% (n=560) had a history of T2DM and 36% (n=567) being classified as non-heavy drinker. Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the study population, including the NH-White cohort.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population.

| Entire cohort | Non-Hispanic White cohort | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Variables | N=1557 | N=1153 |

|

| ||

| Age (years) | 48.5 ± 11.5 | 50.7 ± 11.5 |

| Gender (female), n (%) | 989 (64) | 727 (63) |

| Type 2 diabetes n (%) | 560 (36) | 408 (35) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 873 (56) | 685 (59) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 34.4 ± 6.4 | 34.9 ± 6.4 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 109.2 ± 14.3 | 110.4 ± 14.2 |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1153 (74) | - |

| Hispanic | 156 (10) | - |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 52 (3) | - |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 106 (7) | - |

| Other or multiracial | 90 (6) | - |

| Non-heavy alcohol intake, (%) | 567 (36) | 433 (38) |

| Genetic variants, n (%) | ||

| PNPLA3 rs738409 | ||

| CC | 490 (31) | 377 (33) |

| CG | 680 (44) | 528 (46) |

| GG | 387 (25) | 248 (22) |

| HSD17B13 rs72613567 | ||

| −/− | 1028 (66) | 737 (64) |

| −/A | 446 (29) | 348 (30) |

| A/A | 83 (5) | 68 (6) |

| TM6SF2 rs58542926 | ||

| CC | 1005 (78) | 866 (76) |

| TC | 328 (21) | 254 (22) |

| TT | 24 (1) | 19 (2) |

| MBOAT7 rs641738 | ||

| CC | 511 (33) | 273 (24) |

| TC | 721 (46) | 550 (48) |

| TT | 325 (21) | 317 (28) |

| Lab reports | ||

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 72.0 ± 50.2 | 69.9 ± 47.2 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 51.7 ± 33.0 | 51.3 ± 32.3 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 180.7 ± 166.1 | 185.6 ± 178.1 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 192.0 ± 43.7 | 192.4 ± 44.3 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 43.7 ± 11.9 | 43.3 ± 11.6 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 115.8 ± 36.9 | 115.7 ± 37.3 |

| Histology reports | ||

| Steatosis, n (%) | ||

| <5% | 31 (2) | 21 (1.8) |

| 5–33% | 577 (37.1) | 420 (36.5) |

| 33–66% | 561 (36) | 413 (35.8) |

| >66% | 388 (24.9) | 299 (25.9) |

| Lobular inflammation, n (%) | ||

| No foci | 7 (0.4) | 2 (0.2) |

| <2 foci/200x | 783 (50.3) | 606 (52.6) |

| 2–4 foci/200x | 585 (37.6) | 419 (36.3) |

| >4 foci/200x | 182 (11.7) | 126 (10.9) |

| Ballooning, n (%) | ||

| None | 513 (33) | 383 (33.2) |

| Few | 444 (28.5) | 320 (27.8) |

| Many | 600 (38.5) | 450 (39) |

| Portal inflammation, n (%) | ||

| None | 184 (11.8) | 126 (10.9) |

| Mild | 994 (63.8) | 740 (64.2) |

| > Mild | 379 (24.4) | 287 (24.9) |

| Fibrosis stages, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 362 (23.2) | 258 (22.4) |

| 1 | 461 (29.6) | 313 (27.2) |

| 2 | 306 (19.7) | 238 (20.6) |

| 3 | 296 (19) | 227 (19.7) |

| 4 | 132 (8.5) | 117 (10.1) |

Quantitative variables are displayed as mean ± SD.

Even though all individual histological scores were independently correlated with the fibrosis score even after controlling for important confounders, we did not find relevant multicollinearity issues in the multiple linear regression analysis. The tolerance and the variance inflation factor, two collinearity diagnostic factors, were typically greater than 0.1 and less than 2.5, respectively (Table 2). (29)

Table 2.

Correlations between mediator scores and the fibrosis stage (0–4). Non-Hispanic White (n=1153) and other racial/ethnic groups (n=404) cohorts. Analysis based on multivariable linear regression.

| Non-Hispanic White population |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted estimates | Collinearity statistics | ||||

| Histology scores | β coefficient | 95% CI | P value * | Tolerance | VIF† |

|

|

|||||

| Steatosis (0–3) | −0.11 | −0.18 to −0.04 | 0.002 | 0.897 | 1.115 |

| Lobular inflammation (0–3) | 0.08 | −0.01 to 0.17 | 0.093 | 0.765 | 1.307 |

| Ballooning degeneration (0–2) | 0.54 | 0.46 to 0.62 | <0.001 | 0..872 | 1.363 |

| Portal inflammation (0–2) | 0.78 | 0.67 to 0.88 | <0.001 | 0.872 | 1.146 |

|

Other racial/ethnic groups |

|||||

| Steatosis (0–3) | −0.08 | −0.18 to 0.03 | 0.145 | 0.865 | 1.157 |

| Lobular inflammation (0–3) | 0.18 | 0.06 to 0.31 | 0.005 | 0.778 | 1.286 |

| Ballooning degeneration (0–2) | 0.57 | 0.45 to 0.68 | <0.001 | 0.752 | 1.330 |

| Portal inflammation (0–2) | 0.48 | 0.33 to 0.63 | <0.001 | 0.830 | 1.205 |

Adjustment for age, gender, body mass index (kg/m2), T2DM, non-heavy alcohol intake, PNPLA3 rs738409, HSD17B13 rs72613567, TM6SF2 rs58542926, MBOAT7 rs641738. Race/ethnicity was further included in the multivariable analysis focusing on the other racial/ethnic groups. All histology scores were included in the same multivariable model along with other previously mentioned confounders.

All correlation coefficients were below 0.70, reducing the concern of the presence of multicollinearity. (30)

Relationship between rs738409 and mediators (histology scores)

NH-White population (n=1153)

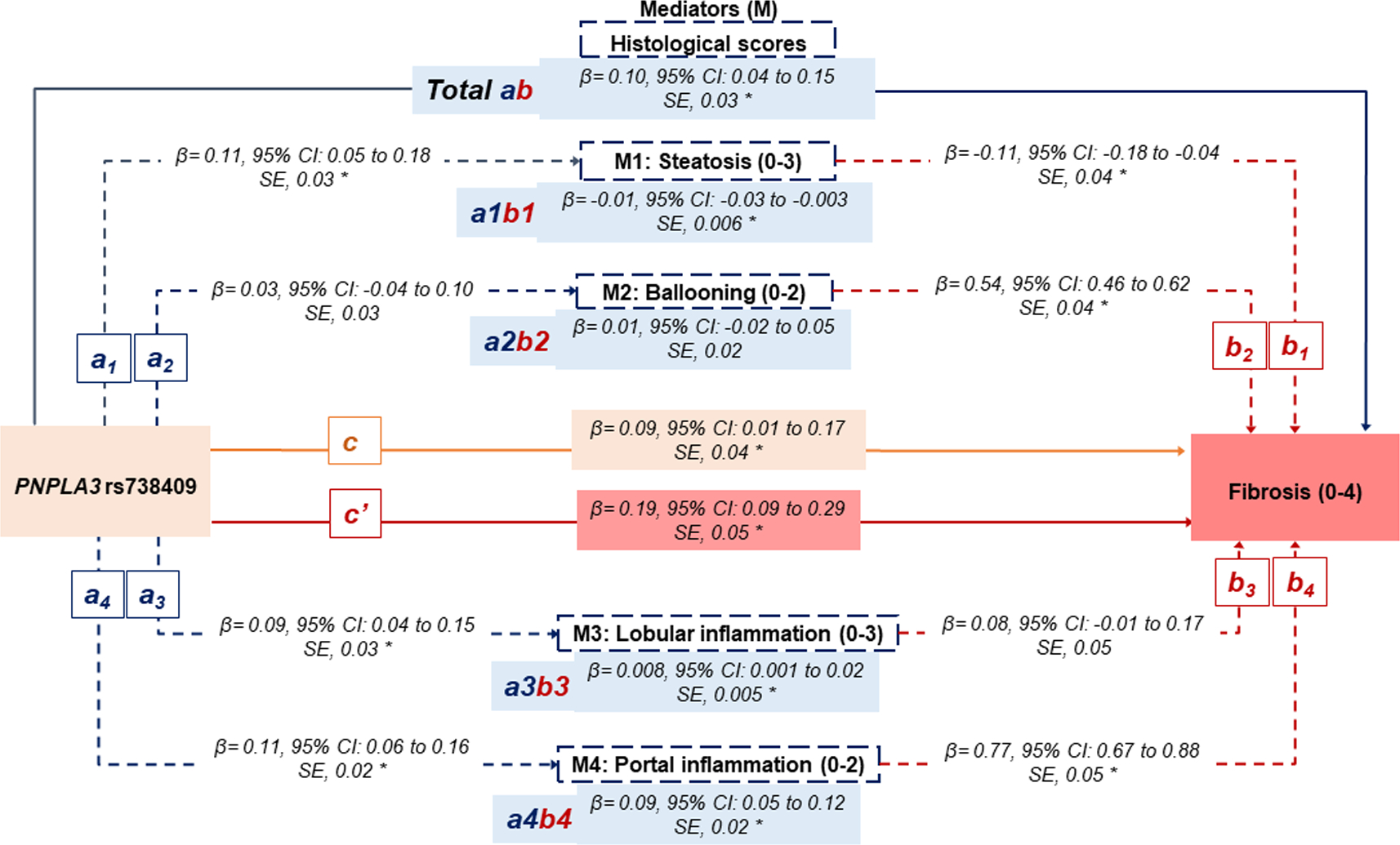

We detected positive and significant relationships between rs738409 and steatosis (β=0.11, 95% CI: 0.05–0.18), and lobular (β=0.09, 95% CI: 0.04–0.15) and portal (β=0.11, 95% CI: 0.06–0.16) inflammation, signifying that rs738409 increases the risk of steatosis and portal and lobular inflammation, but not ballooning degeneration (β=0.03, 95% CI: −0.04 to 0.10) (Paths a on the Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Statistical diagram of a parallel mediation model including 4 mediators.

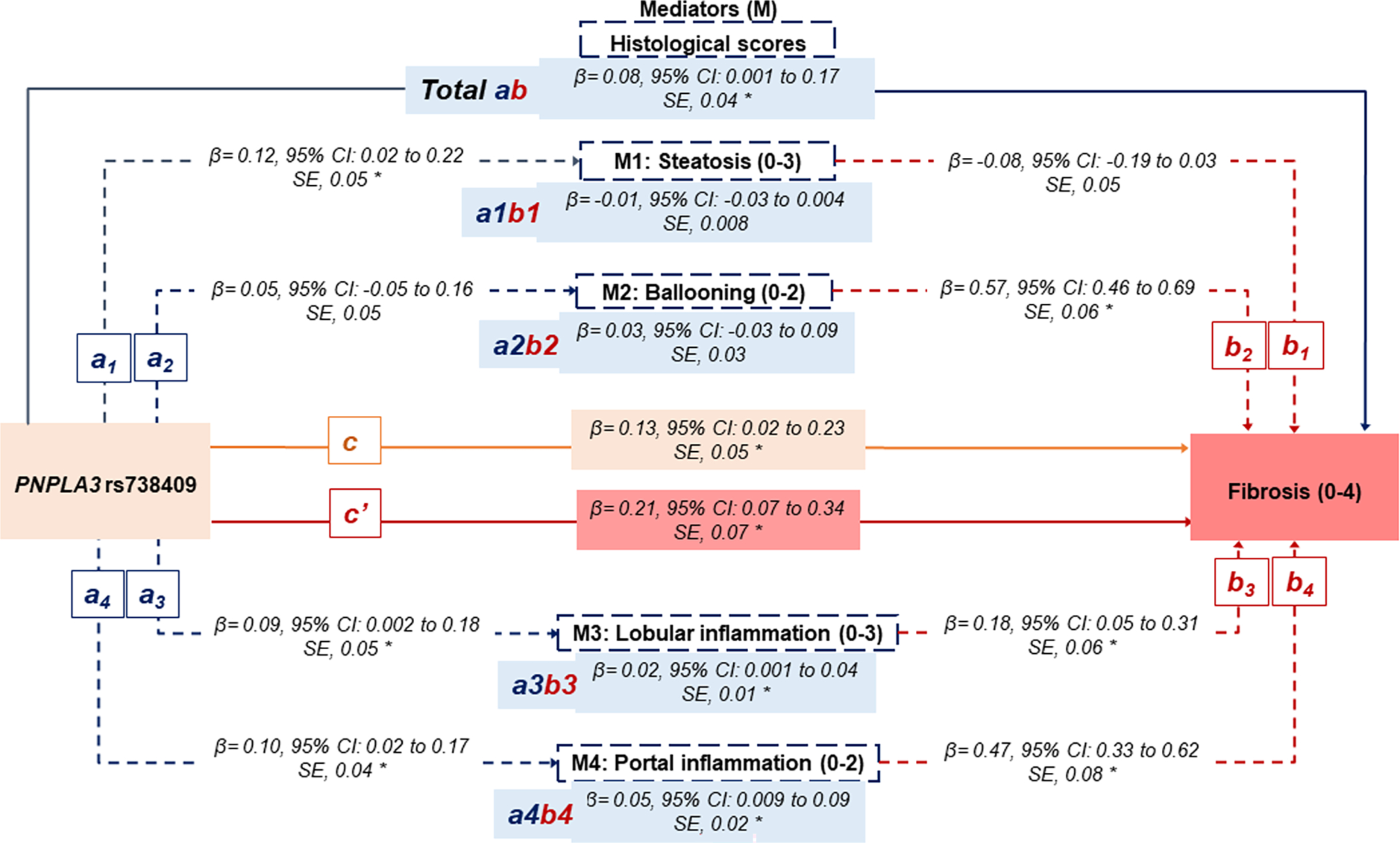

A) The non-Hispanic White population (n=1153). </p/>. B) Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, and other/multiracial (n=404).

a: The effect of rs738409 on the mediator (individual histological score)

b: The effect of the mediator (individual histological score) on the fibrosis score.

ab: The indirect effect of the rs738409 on the fibrosis score through each mediator (individual histological score).

Total ab: The sum of all indirect effects of the rs738409 on the fibrosis score through all mediators.

c: The direct effect of rs738409 on the fibrosis score, not operating through mediators.

c’: the total effect of rs738409.

β indicates bootstrap coefficients.

All analyses adjusted for age, gender, BMI (kg/m2), T2DM, non-heavy alcohol intake, PNPLA3 rs738409, HSD17B13 rs72613567, TM6SF2 rs58542926, MBOAT7 rs641738. Race/ethnicity was further included in the multivariable analysis focusing on the other racial/ethnic groups.

The star symbol (*) represents statistically significant paths.

Other racial and ethnic groups (n=404)

The rs738409 was positively associated with steatosis (β=0.12, 95% CI: 0.02–0.22), and lobular (β=0.09, 95% CI: 0.002–0.18) and portal (β=0.10, 95% CI: 0.02–0.18) inflammation. No association was found between rs738409 and the risk of ballooning degeneration (β=0.05, 95% CI: −0.05 to 0.16) (Paths a on the Figure 1B).

Relationship between mediators (histology scores) and fibrosis severity

NH-White population (n=1153)

Both ballooning degeneration (β=0.54, 95% CI: 0.46–0.62) and portal inflammation (β=0.77, 95% CI: 0.67–0.88) were significantly associated with an increased risk of fibrosis. Lobular inflammation (β=0.08, 95% CI: −0.01 to 0.17) tended to be positively associated with fibrosis but did not reach the statistical significance (Paths b on Figure 1A). Notably, steatosis (β= −0.11, 95% CI: −0.18 to −0.04) was negatively associated with fibrosis, meaning that lower steatosis scores were associated with advanced fibrosis.

To better understand the relationship within the mediators (“intermediate histology scores”), covariate-adjusted linear regression analyses were additionally performed. After controlling for rs738409 and other important confounders, steatosis was inversely correlated with portal inflammation (Adj. β= −0.07, P<0.01) and fibrosis (Adj. β= −0.11, P=0.01), but positively correlated with lobular inflammation (Adj. β=0.16, P<0.01) and ballooning degeneration (Adj. β=0.07, P=0.02). Lobular inflammation, ballooning degeneration, and portal inflammation were positively correlated with each other (Table 3). Since steatosis was negatively correlated with both fibrosis and portal inflammation, we sought to examine whether these correlations remained significant across all rs738409 genotypes (Table 4). Of note, steatosis remained negatively correlated with portal inflammation and fibrosis in participants with GC (Adj. β= −0.05, P=0.047 and Adj. β= −0.19, P<0.01) and GG genotypes (Adj. β= −0.16, P<0.01 and Adj. β= −0.21, P=0.03) but not in those with CC (Adj. β= −0.04, P=0.287 and Adj. β=0.06, P=0.450). The same analysis focusing on other racial/ethnic groups showed significant and negative correlations of steatosis with portal inflammation and fibrosis in those with rs738409 GG genotype (Table 5).

Table 3.

Covariate-adjusted* correlations between all histological lesions. Results based on multivariable linear regression. NH-White (n=1153) and other racial/ethnic groups (n=404) populations.

|

Non-Hispanic White population

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steatosis | Lobular inflammation | Ballooning degeneration | Portal inflammation | Fibrosis | ||

|

|

||||||

| Steatosis | Adj. β | 0.16 | 0.07 | −0.07 | −0.11 | |

| P-value | <0.001 | 0.018 | 0.001 | 0.011 | ||

| Lobular inflammation | Adj. β | 0.49 | 0.11 | 0.41 | ||

| P-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Ballooning degeneration | Adj. β | 0.12 | 0.65 | |||

| P-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Portal inflammation | Adj. β | 0.94 | ||||

| P-value | <0.001 | |||||

|

Other racial/ethnic groups |

||||||

| Steatosis | Adj. β | 0.13 | −0.07 | −0.08 | −0.13 | |

| P-value | 0.005 | 0.192 | 0.036 | 0.05 | ||

| Lobular inflammation | Adj. β | 0.42 | 0.11 | 0.46 | ||

| P-value | <0.001 | 0.008 | <0.001 | |||

| Ballooning degeneration | Adj. β | 0.14 | 0.70 | |||

| P-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Portal inflammation | Adj. β | 0.68 | ||||

| P-value | <0.001 | |||||

Multivariable linear regression models adjusting for age, gender, body mass index (kg/m2), T2DM, non-heavy alcohol intake, PNPLA3 rs738409, HSD17B13 rs72613567, TM6SF2 rs58542926, MBOAT7 rs641738. Race/ethnicity was further included in the multivariable analysis focusing on the other racial/ethnic groups cohort.

Table 4.

Covariate-adjusted* correlations between all histological lesions. Results based on multivariable linear regression. Sensitivity analysis by each rs738409 genotype. NH-White population (n=1153).

| rs738409 CC genotype (n=377) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steatosis | Lobular inflammation | Ballooning degeneration | Portal inflammation | Fibrosis | ||

|

|

||||||

| Steatosis | Adj. β | 0.12 | 0.08 | −0.04 | 0.06 | |

| P-value | 0.004 | 0.137 | 0.287 | 0.450 | ||

| Lobular inflammation | Adj. β | 0.54 | 0.17 | 0.52 | ||

| P-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Ballooning degeneration | Adj. β | 0.11 | 0.65 | |||

| P-value | 0.004 | <0.001 | ||||

| Portal inflammation | Adj. β | 0.92 | ||||

| P-value | <0.001 | |||||

|

rs738409 CG genotype (n=528) |

||||||

| Steatosis | Adj. β | 0.16 | 0.07 | −0.05 | −0.19 | |

| P-value | <0.001 | 0.095 | 0.047 | 0.002 | ||

| Lobular inflammation | Adj. β | 0.45 | 0.07 | 0.37 | ||

| P-value | <0.001 | 0.049 | <0.001 | |||

| Ballooning degeneration | Adj. β | 0.10 | 0.61 | |||

| P-value | 0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Portal inflammation | Adj. β | 0.93 | ||||

| P-value | <0.001 | |||||

|

rs738409 GG genotype (n=248) |

||||||

| Steatosis | Adj. β | 0.22 | 0.06 | −0.16 | −0.21 | |

| P-value | <0.001 | 0.385 | <0.001 | 0.031 | ||

| Lobular inflammation | Adj. β | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.33 | ||

| P-value | <0.001 | 0.030 | 0.002 | |||

| Ballooning degeneration | Adj. β | 0.18 | 0.76 | |||

| P-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Portal inflammation | Adj. β | 0.94 | ||||

| P-value | <0.001 | |||||

Multivariable linear regression models adjusting for age, gender, BMI (kg/m2), T2DM, non-heavy alcohol intake, PNPLA3 rs738409, HSD17B13 rs72613567, TM6SF2 rs58542926, MBOAT7 rs641738.

Table 5.

Covariate-adjusted* correlations between all histological lesions. Results based on multivariable linear regression. Sensitivity analysis by each rs738409 genotype. Other racial/ethnic groups (n=404).

| rs738409 CC genotype (n=113) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steatosis | Lobular inflammation | Ballooning degeneration | Portal inflammation | Fibrosis | ||

|

|

||||||

| Steatosis | Adj. β | 0.22 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.06 | |

| P-value | 0.022 | 0.849 | 0.497 | 0.645 | ||

| Lobular inflammation | Adj. β | 0.54 | 0.10 | 0.49 | ||

| P-value | <0.001 | 0.190 | <0.001 | |||

| Ballooning degeneration | Adj. β | 0.18 | 0.67 | |||

| P-value | 0.010 | <0.001 | ||||

| Portal inflammation | Adj. β | 0.54 | ||||

| P-value | 0.002 | |||||

|

rs738409 CG genotype (n=152) |

||||||

| Steatosis | Adj. β | 0.06 | −0.08 | −0.03 | −0.09 | |

| P-value | 0.441 | 0.369 | 0.613 | 0.417 | ||

| Lobular inflammation | Adj. β | 0.47 | 0.16 | 0.54 | ||

| P-value | <0.001 | 0.020 | <0.001 | |||

| Ballooning degeneration | Adj. β | 0.03 | 0.70 | |||

| P-value | 0.584 | <0.001 | ||||

| Portal inflammation | Adj. β | 0.69 | ||||

| P-value | <0.001 | |||||

|

rs738409 GG genotype (n=139) |

||||||

| Steatosis | Adj. β | 0.16 | −0.11 | −0.14 | −0.24 | |

| P-value | 0.041 | 0.267 | 0.033 | 0.050 | ||

| Lobular inflammation | Adj. β | 0.31 | 0.09 | 0.31 | ||

| P-value | 0.002 | 0.239 | 0.024 | |||

| Ballooning degeneration | Adj. β | 0.23 | 0.78 | |||

| P-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Portal inflammation | Adj. β | 0.75 | ||||

| P-value | <0.001 | |||||

Multivariable linear regression models adjusting for age, gender, BMI (kg/m2), T2DM, non-heavy alcohol intake, PNPLA3 rs738409, HSD17B13 rs72613567, TM6SF2 rs58542926, MBOAT7 rs641738, race/ethnicity.

Total, direct, and indirect effect of rs738409 on fibrosis severity. Analysis incorporating mediators in parallel.

NH-White population (n=1153)

Figure 1A depicts the estimated total and direct effect of rs738409 on fibrosis score, as well as the estimated indirect effects through each mediator “histological score”. The total effect (c’ path on Figure 1A) of rs738409 on fibrosis severity was β=0.19 (95% CI: 0.09–0.29). The direct effect (c path on Figure 1A) of rs738409 on fibrosis removing mediators’ effect was estimated at β=0.09 (95% CI: 0.01–0.17), which represents 47% of the total effect of rs738409 on fibrosis. The indirect effect of rs738409 on fibrosis through all mediators’ effects was estimated at β=0.010 (95% CI: 0.04–0.15) (Total ab path on Figure 1A). Thus, the percentage of total effect contributed by all mediators was estimated to be 53%. Among all mediators, the greatest estimated effect size was displayed by portal inflammation (β=0.09, 95% CI: 0.047–0.120), followed by lobular inflammation (β=0.008, 95% CI: 0.001–0.02), and steatosis (β= −0.01, 95% CI: −0.03 to −0.003). In other words, the effects of rs738409 variant, as per G allele, on fibrosis that is attributed to variations in portal inflammation, lobular inflammation, and steatosis are 0.09, 0.008, and −0.01, respectively. The percentage of total indirect effect contributed by each mediator was estimated to be 89%, 8.7%, and −12% for portal inflammation, lobular inflammation, and steatosis, respectively. Ballooning degeneration did not significantly mediate the relationship between rs738409 and fibrosis, although a positive marginal trend was observed (β=0.01, 95% CI: −0.02 to 0.05).

Other racial/ethnic groups (n=404)

We replicated our analysis in the cohort with different racial/ethnic groups, and results did not differ significantly from those obtained in the NH-White population (Figure 1B) even after adjusting for the same confounding factors along with race/ethnicity. The total effect of rs738409 on fibrosis was β=0.21 (95% CI: 0.07–0.34). The direct effect of rs738409 on fibrosis excluding mediators’ effect was estimated at β=0.13 (95% CI: 0.02–0.23), which represents 62% of the total effect of rs738409 on fibrosis. The indirect effect of rs738409 on fibrosis through all mediators’ effects was estimated at β=0.08 (95% CI: 0.001–0.17), signifying 38% of the total effect. Steatosis did not significantly mediate the effect between rs738409 and fibrosis. Portal inflammation and lobular inflammation remained the most important mediators, yielding 63% and 25% of the total indirect effects.

Sensitivity analysis

rs738409 effect through steatosis after excluding participants with advanced fibrosis. Analysis based on the whole cohort (n=1129)

Supplemental Figure 2. depicts the distribution of the steatosis severity (0–3) across fibrosis stages (0–4). An inverse association between the severity of steatosis and fibrosis was observed; higher fibrosis stages (3 and 4) were associated with lower steatosis scores (0 and 1). Thus, we decided to examine the effect of rs738409 on fibrosis via steatosis after excluding participants with advanced fibrosis (stages 3 and 4). Overall, our mediation analysis (Supplemental Figure 3) showed the same results that those obtained in NH-White and other racial/ethnic populations. However, steatosis (β=0.06, 95% CI: 0.01–0.11) was positively associated with fibrosis, and therefore, the indirect effect of rs738409 through steatosis was also positive (β=0.01, 95% CI: 0.002–0.02). The total, direct and indirect effects of rs738409 on fibrosis were estimated at β=0.08 (95% CI: 0.02–0.14), β=0.03 (95% CI: 0.001–0.09) and β=0.05, 95% CI: 0.01–0.08), respectively. The last two estimates represent 38% and 62% of the indirect or direct effects of rs738409 on fibrosis. Among the intermediate histology traits, portal inflammation remained the most robust mediator, followed by lobular inflammation and steatosis.

Total, direct, and indirect effect of rs738409 on fibrosis. Analysis incorporating mediators sequentially.

The mediation analysis was performed in the whole population (n=1557) and confirmed that rs738409 is directly associated with fibrosis (β=0.09, 95% CI: 0.04–0.13), meaning 50% of the total effect. Importantly, the indirect effect of rs738409 on fibrosis might be partly explained by portal inflammation (78%), lobular inflammation (8%), and steatosis (12%) when analyzed as single mediators. Ballooning degeneration as a single mediator did not influence the association between rs738409 and fibrosis. The most important sequential indirect paths were those including lobular inflammation followed by ballooning (β=0.023, 95% CI: 0.011–0.037) or portal inflammation (β=0.004, 95% CI: 0.001–0.008). A summary of all direct and indirect paths tested in the model is provided in Supplemental Table 1. A sequential mediation analysis performed in the population without advanced fibrosis (n=1129, Supplemental Table 2) confirmed the above-mentioned results. rs738409 displayed a significant direct effect of fibrosis (β=0.03, 95% CI: 0.001–0.09), signifying 38% of the total effect. Portal (52%) and lobular (30%) inflammation and steatosis (22%) significantly mediated the association between rs738409 and fibrosis. Among different sequential combinations of histology traits, the path including lobular inflammation followed by ballooning degeneration displayed the most remarkable indirect effect (β=0.020, 95% CI: 0.010–0.031). In both sequential mediations analyses, a sequential path of steatosis and then lobular inflammation remained significant, but with a minor contribution to the total indirect effect.

Discussion

In this observational and prospective study, we examined whether and to what extent steatosis, lobular inflammation, ballooning degeneration, and portal inflammation might mediate the effect of rs738409 on fibrosis severity by analyzing a relatively large U.S. population with biopsy-proven NAFLD.

Principal findings

Our mediation analyses suggested that rs738409 increases the risk of overall fibrosis, and part of its effects might partly be explained by direct (47% and 62%) and indirect (53% and 38%) histology pathways. Among the indirect histology pathways, a remarkable proportion of the effect of rs738409 on fibrosis was explained through the portal inflammation pathway (89% and 63%). It is noteworthy to mention that higher effect size estimates were observed between rs738409 and portal inflammation (a path in Figure 1), and between portal inflammation and overall fibrosis (b path in Figure 1). Thus, it is not surprising that portal inflammation was the most robust mediator between rs738409 and overall fibrosis severity relationships.

The contribution of either steatosis or lobular inflammation as histology mediators between rs738409 and the risk of overall fibrosis was relatively small and about 10%. Ballooning degeneration as a single mediator did not influence the association between rs738409 and overall fibrosis; this finding is likely explained by the lack of association between rs738409 and ballooning degeneration. Our mediation analyses testing the sequential effects of up to 2 histology traits showed that lobular inflammation followed by ballooning degeneration was the most significant combinatorial pathway, explaining between 26% and 40% of the total indirect effect of rs738409 on overall fibrosis.

Interpretation of results

Data from the cross-sectional analysis have shown a positive link between steatosis severity and increased risk of lobular inflammation, zone 3 fibrosis, and definite NASH, however, its association with ballooning and advanced fibrosis is less clear in adults with NAFLD. (35) Chronic portal inflammation is another histological marker of advanced NAFLD; its association is especially strong with bridging fibrosis and cirrhosis. (36, 37) In a seminal study, Brunt et al. found an inverse association between chronic portal inflammation and steatosis severity. (36) Previous studies have reported that liver fat declines in patients with advanced fibrosis (burnt-out NASH). (18, 38)

Consistent with the above-mentioned reports, we observed that portal inflammation and fibrosis severity were strongly correlated with each other, and both were negatively associated with steatosis severity. Interestingly, the inverse relationships between steatosis and portal inflammation and fibrosis severity were stronger in participants with rs738409 genotypes GC and GG as compared with CC. The mechanisms underpinning these associations are not well understood. One potential explanation can be that carriers of the rs738409 G allele are at increased risk of stages of fibrosis and higher degrees of portal inflammation, which can result in less accumulation of fat.

We tested this hypothesis by performing further mediation analyses (Supplemental Figure 3 and Supplemental Table 2) in a subpopulation that excluded participants with advanced stages of fibrosis (≥3). These analyses showed that steatosis and fibrosis scores were positively associated; therefore, the indirect estimate of rs738409 on fibrosis via steatosis was also positive. Taken altogether, these sensitivity analyses might confirm that the negative relationship between steatosis and fibrosis scores might be largely influenced by the significant proportion of individuals with advanced fibrosis (28%) enrolled in our study population.

One of the key findings of our study was that 47% and 62% of the total effect of the rs738409 G allele on overall fibrosis severity could be explained by a direct effect without the mediation of other histology factors, supporting the hypothesis that rs738409 likely promotes fibrosis development by triggering specific fibrogenic pathways. (39–42) Consistently, various epidemiological studies have indicated that rs738409 not only confers susceptibility to liver fat accumulation but also increases the risk of liver fibrosis and its progression in NAFLD patients. (2–5, 43, 44) Recent studies have reported that rs738409 increases the risk of inflammation and fibrosis regardless of the severity of steatosis, (43, 45) which suggests that other mechanisms not implicated in the lipid biosynthesis may also be playing a key role in the NAFLD progression. (39, 40, 46, 47) Our findings might also have important therapeutic implications as targeting the rs738409 variant is expected to be an excellent pharmacological strategy to treat NAFLD patients. Our mediation analyses identified the most common histology pathways through which rs738409 might influence fibrosis development. These pathways may offer a better understanding of how rs738409 affects disease progression and the potential benefits of a targeted-PNPLA3 intervention to reduce inflammation and fibrosis.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Our study has several strengths. This is the first study to examine whether intermediate histologic traits may be determinants of the effect of rs738409 on liver fibrosis using causal mediation analysis. (31, 48) Biopsies were evaluated centrally by the NASH CRN Pathology Committee. Adjustment for relevant confounders that could be associated with either rs738409 or histology scores allow us to disentangle the effect of rs738409 on fibrosis from the effects of these relevant confounders. Total, direct, and indirect effect size estimates of rs738409 on overall fibrosis were fairly reproduced and gave the same results in two different racial and ethnic subpopulations (NH-White and other racial/ethnic groups). This is important as the severity of NAFLD and the rs738409 minor allelic frequent distribution may differ across racial/ethnic groups. (1, 5, 49)

Our study has limitations that must be considered in the interpretation of the findings. Despite the relatively large sample size, results from our mediation analyses cannot be used to infer causality due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, even though temporality between exposure, mediator, and outcome variables were maintained. Future longitudinal research is needed to examine the links between rs738409, fibrosis, and intermediate histology traits and provide more reliable insights into the direction of the causal flow, although this study design would require serial liver biopsies resulting in significant ethic concerns. While our results did not significantly vary between the NH-White and other racial and ethnic groups, replication of this study would be required in individual racial/ethnic groups (e.g., NH-Black and Hispanic). Finally, mediation analysis is not suitable for identifying effective mediators rather than testing the significance of an assumed causal mediator.

In summary, our findings suggest that half of the total effect of rs738409 on overall fibrosis severity could be explained by a direct pathway without the mediation of other histology factors, supporting the hypothesis that rs738409 likely promotes fibrosis development by triggering specific fibrogenic pathways. The other half of the total effect of rs738409 on fibrosis severity seems to be mediated primarily through portal inflammation, highlighting the need for further investigations to better understand the pathogenesis and significance of portal inflammation, especially in the context of PNPLA3 genetic variation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network (NASH CRN) investigators and the Ancillary Studies Committee for providing clinical samples and relevant data from the Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) Database, Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) Adult Database 2, PIVENS trial, and FLINT trial.

The authors also thank the participants involved in the NASH CRN studies.

Financial support:

This study was approved by the Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network as an Ancillary Study (NASH CRN AS # 93). The NASH CRN is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (U01DK061718, U01DK061728, U01DK061731, U01DK061732, U01DK061734, U01DK061737, U01DK061738, U01DK061730, and U01DK061713). No funding was received from the NASH CRN for conducting this ancillary study. This study was supported in part by David W Crabb Endowed Professorship funds to Dr. Chalasani.

Abbreviations

- PNPLA3

patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3

- BMI

body mass index

- TG

triglycerides

- NASH

non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- CRN

clinical research network

- VIF

variance inflation factor

- T2DM

type 2 diabetes mellitus

- CIs

confidence intervals

- NH

non-Hispanic

- SD

standard deviation

- SE

standard error

- HSD17B13

hydroxysteroid 17-beta dehydrogenase 13

- TM6SF2

transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2

- MBOAT7

membrane-bound o-acyltransferase domain-containing

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interests

There are none for this paper. For full disclosure, Dr. Chalasani has ongoing paid consulting activities (or had in the preceding 12 months) with Abbvie, Madrigal, Zydus, Galectin, Altimmune, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Lilly, and Foresite. These consulting activities are generally in the areas of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and drug hepatotoxicity. Dr. Chalasani receives research grant support from Exact Sciences, DSM, and Galectin Therapeutics where his institution receives the funding. Drs. Vilar-Gomez, Sookoian, Pirola, Wilson, Liu, and Liang have nothing to disclose.

Code availability

The source macro “PROCESS” used in our causal mediation analysis to generate results included in all Tables and Figures of the manuscript can be downloaded from the following link: http://processmacro.org/download.html

Version 4.0 of PROCESS operates on both Windows and Mac versions of SPSS and SAS. PROCESS for SPSS requires SPSS version 19 or later but works best on versions 22 and above. PROCESS for SAS requires PROC IML. PROCESS for R was written in R base 3.6.1 and requires no additional packages.

References

- 1.Romeo S, Kozlitina J, Xing C, Pertsemlidis A, Cox D, Pennacchio LA, Boerwinkle E, et al. Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Genet 2008;40:1461–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sookoian S, Castano GO, Burgueno AL, Gianotti TF, Rosselli MS, Pirola CJ. A nonsynonymous gene variant in the adiponutrin gene is associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease severity. J Lipid Res 2009;50:2111–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Speliotes EK, Butler JL, Palmer CD, Voight BF, Consortium G, Consortium MI, Nash CRN, et al. PNPLA3 variants specifically confer increased risk for histologic nonalcoholic fatty liver disease but not metabolic disease. Hepatology 2010;52:904–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rotman Y, Koh C, Zmuda JM, Kleiner DE, Liang TJ, Nash CRN. The association of genetic variability in patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 (PNPLA3) with histological severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2010;52:894–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sookoian S, Pirola CJ. Meta-analysis of the influence of I148M variant of patatin-like phospholipase domain containing 3 gene (PNPLA3) on the susceptibility and histological severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2011;53:1883–1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Unalp-Arida A, Ruhl CE. Patatin-Like Phospholipase Domain-Containing Protein 3 I148M and Liver Fat and Fibrosis Scores Predict Liver Disease Mortality in the U.S. Population. Hepatology 2020;71:820–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trépo E, Romeo S, Zucman-Rossi J, Nahon P. PNPLA3 gene in liver diseases. Journal of Hepatology 2016;65:399–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He S, McPhaul C, Li JZ, Garuti R, Kinch L, Grishin NV, Cohen JC, et al. A sequence variation (I148M) in PNPLA3 associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease disrupts triglyceride hydrolysis. J Biol Chem 2010;285:6706–6715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumari M, Schoiswohl G, Chitraju C, Paar M, Cornaciu I, Rangrez AY, Wongsiriroj N, et al. Adiponutrin functions as a nutritionally regulated lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase. Cell Metab 2012;15:691–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang Y, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Expression and characterization of a PNPLA3 protein isoform (I148M) associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Biol Chem 2011;286:37085–37093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li JZ, Huang Y, Karaman R, Ivanova PT, Brown HA, Roddy T, Castro-Perez J, et al. Chronic overexpression of PNPLA3I148M in mouse liver causes hepatic steatosis. J Clin Invest 2012;122:4130–4144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smagris E, BasuRay S, Li J, Huang Y, Lai KM, Gromada J, Cohen JC, et al. Pnpla3I148M knockin mice accumulate PNPLA3 on lipid droplets and develop hepatic steatosis. Hepatology 2015;61:108–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu W, Anstee QM, Wang X, Gawrieh S, Gamazon ER, Athinarayanan S, Liu YL, et al. Transcriptional regulation of PNPLA3 and its impact on susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver Disease (NAFLD) in humans. Aging (Albany NY) 2016;9:26–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.BasuRay S, Smagris E, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. The PNPLA3 variant associated with fatty liver disease (I148M) accumulates on lipid droplets by evading ubiquitylation. Hepatology 2017;66:1111–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.BasuRay S, Wang Y, Smagris E, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Accumulation of PNPLA3 on lipid droplets is the basis of associated hepatic steatosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116:9521–9526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanyal AJ, Van Natta ML, Clark J, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Diehl A, Dasarathy S, Loomba R, et al. Prospective Study of Outcomes in Adults with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2021;385:1559–1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Angulo P, Kleiner DE, Dam-Larsen S, Adams LA, Bjornsson ES, Charatcharoenwitthaya P, Mills PR, et al. Liver Fibrosis, but No Other Histologic Features, Is Associated With Long-term Outcomes of Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2015;149:389–397.e310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vilar-Gomez E, Calzadilla-Bertot L, Wai-Sun Wong V, Castellanos M, Aller-de la Fuente R, Metwally M, Eslam M, et al. Fibrosis Severity as a Determinant of Cause-Specific Mortality in Patients With Advanced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Multi-National Cohort Study. Gastroenterology 2018;155:443–457.e417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matteoni CA, Younossi ZM, Gramlich T, Boparai N, Liu YC, McCullough AJ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a spectrum of clinical and pathological severity. Gastroenterology 1999;116:1413–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angulo P, Keach JC, Batts KP, Lindor KD. Independent predictors of liver fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 1999;30:1356–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Wilson LA, Unalp A, Behling CE, Lavine JE, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, et al. Portal chronic inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): A histologic marker of advanced NAFLD—Clinicopathologic correlations from the nonalcoholic steatohepatitis clinical research network. Hepatology 2009;49:809–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vilar-Gomez E, Pirola CJ, Sookoian S, Wilson LA, Liang T, Chalasani N. The Protection Conferred by HSD17B13 rs72613567 Polymorphism on Risk of Steatohepatitis and Fibrosis May Be Limited to Selected Subgroups of Patients With NAFLD. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2021;12:e00400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vilar-Gomez E, Sookoian S, Pirola CJ, Liang T, Gawrieh S, Cummings O, Liu W, et al. ADH1B∗2 Is Associated With Reduced Severity of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Adults, Independent of Alcohol Consumption. Gastroenterology 2020;159:929–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Loomba R, Sanyal AJ, Lavine JE, Van Natta ML, Abdelmalek MF, Chalasani N, et al. Farnesoid X nuclear receptor ligand obeticholic acid for non-cirrhotic, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (FLINT): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2015;385:956–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Clark JM, Bass NM, Van Natta ML, Unalp-Arida A, Tonascia J, Zein CO, et al. Clinical, laboratory and histological associations in adults with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2010;52:913–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanyal AJ, Chalasani N, Kowdley KV, McCullough A, Diehl AM, Bass NM, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, et al. Pioglitazone, vitamin E, or placebo for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1675–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, Behling C, Contos MJ, Cummings OW, Ferrell LD, et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2005;41:1313–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Wilson LA, Belt P, Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) activity score and the histopathologic diagnosis in NAFLD: distinct clinicopathologic meanings. Hepatology 2011;53:810–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miles J: Tolerance and Variance Inflation Factor. In: Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoo W, Mayberry R, Bae S, Singh K, Peter He Q, Lillard JW. A Study of Effects of MultiCollinearity in the Multivariable Analysis. International journal of applied science and technology 2014;4:9–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.VanderWeele TJ. Mediation Analysis: A Practitioner’s Guide. Annu Rev Public Health 2016;37:17–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods 2008;40:879–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press, 2013: xvii, 507–xvii, 507. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schoemann AM, Boulton AJ, Short SD. Determining Power and Sample Size for Simple and Complex Mediation Models. Social Psychological and Personality Science 2017;8:379–386. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chalasani N, Wilson L, Kleiner DE, Cummings OW, Brunt EM, Unalp A. Relationship of steatosis grade and zonal location to histological features of steatohepatitis in adult patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol 2008;48:829–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Wilson LA, Unalp A, Behling CE, Lavine JE, Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Portal chronic inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a histologic marker of advanced NAFLD-Clinicopathologic correlations from the nonalcoholic steatohepatitis clinical research network. Hepatology 2009;49:809–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rakha EA, Adamson L, Bell E, Neal K, Ryder SD, Kaye PV, Aithal GP. Portal inflammation is associated with advanced histological changes in alcoholic and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Pathol 2010;63:790–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van der Poorten D, Samer CF, Ramezani-Moghadam M, Coulter S, Kacevska M, Schrijnders D, Wu LE, et al. Hepatic fat loss in advanced nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: are alterations in serum adiponectin the cause? Hepatology 2013;57:2180–2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pirazzi C, Valenti L, Motta BM, Pingitore P, Hedfalk K, Mancina RM, Burza MA, et al. PNPLA3 has retinyl-palmitate lipase activity in human hepatic stellate cells. Hum Mol Genet 2014;23:4077–4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mondul A, Mancina RM, Merlo A, Dongiovanni P, Rametta R, Montalcini T, Valenti L, et al. PNPLA3 I148M Variant Influences Circulating Retinol in Adults with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease or Obesity. J Nutr 2015;145:1687–1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kovarova M, Königsrainer I, Königsrainer A, Machicao F, Häring HU, Schleicher E, Peter A. The Genetic Variant I148M in PNPLA3 Is Associated With Increased Hepatic Retinyl-Palmitate Storage in Humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100:E1568–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bruschi FV, Claudel T, Tardelli M, Caligiuri A, Stulnig TM, Marra F, Trauner M. The PNPLA3 I148M variant modulates the fibrogenic phenotype of human hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology 2017;65:1875–1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Valenti L, Al-Serri A, Daly AK, Galmozzi E, Rametta R, Dongiovanni P, Nobili V, et al. Homozygosity for the patatin-like phospholipase-3/adiponutrin I148M polymorphism influences liver fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2010;51:1209–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pennisi G, Pipitone RM, Cammà C, Di Marco V, Di Martino V, Spatola F, Zito R, et al. PNPLA3 rs738409 C>G Variant Predicts Fibrosis Progression by Noninvasive Tools in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;19:1979–1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Valenti L, Rumi M, Galmozzi E, Aghemo A, Del Menico B, De Nicola S, Dongiovanni P, et al. Patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 I148M polymorphism, steatosis, and liver damage in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2011;53:791–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haaker MW, Vaandrager AB, Helms JB. Retinoids in health and disease: A role for hepatic stellate cells in affecting retinoid levels. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids 2020;1865:158674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee YS, Jeong WI. Retinoic acids and hepatic stellate cells in liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;27 Suppl 2:75–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Valeri L, VanderWeele TJ. Mediation analysis allowing for exposure–mediator interactions and causal interpretation: Theoretical assumptions and implementation with SAS and SPSS macros. Psychological Methods 2013;18:137–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vilar-Gomez E, Vuppalanchi R, Mladenovic A, Samala N, Gawrieh S, Newsome PN, Chalasani N. Prevalence of High-risk Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH) in the United States: Results From NHANES 2017–2018. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this study are deposited to the data coordinating center of the Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network. Data can be made available by submitting a request to the NASH CRN data coordinating center, at https://jhuccs1.us/nash/ in compliance with its data-sharing policies and procedures.