Abstract

The use of complementary and alternative medicine has increased, most markedly among cancer patients. Previous research on energy healing is inconclusive, but qualitative studies have mainly reported positive healing experiences, whereas positive results from trials are scarce. Considering the apparent discrepancy between qualitative and quantitative studies, we aimed to describe the interpretation processes of the patients receiving energy healing. We followed the interpretation processes of a subsection of cancer patients who participated in a pragmatic trial on energy healing, including patients in the control groups. No significant differences between the groups were found in the quantitative part of the trial, but the majority of patients in both the intervention and control groups reported subjective improvements. A subset of 32 patients from the trial was selected for this qualitative sub-study to gain insight into their interpretation processes. These 32 patients recruited from the trial were followed with qualitative interviews before, during, and after the treatment period, using a cultural-phenomenological approach. Most patients who received energy healing changed their perception of bodily experiences, and they perceived a wider variety of signs as indicative of healing than the patients in the control groups. After receiving energy healing, the patients also perceived signs that from a medical perspective are regarded as symptoms, as signs of healing. The changes in perception of illness and healing affected decision-making dynamics and should be considered when producing information and communication strategies for health promotion.

Keywords: colon cancer, energy healing, embodiment, perception of pain, perception of healing

Background

The proportion of cancer patients who use complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is higher than in the general population, according to surveys from Europe and Canada.1,2 Cancer patients’ use of CAM increased from an estimated 25% in the 1970s and 1980s to 32% in the 1990s and 49% after 2000, according to a review that covered the research literature from Europe, Canada, the U.S.A., Australia, and New Zealand. 3 In Europe, “energy healing” is among the most widely used forms of CAM by cancer patients. 1 A study from Denmark found that 5.3% of patients with breast cancer had used energy healing or laying on of hands after being diagnosed. 4 The term “energy healing” refers to treatments where the therapists intend to transfer energy to patients, usually by their hands, as in Reiki, Healing Touch, Spiritual healing, and Therapeutic Touch. “Energy” is a key concept in many forms of CAM, but the therapists do not have a standardized definition of the term. An overview of systematic reviews 5 concludes that CAM appears to be beneficial in reducing side effects and improving the quality of life of cancer patients, but also points out that many studies and reviews have methodological flaws. Increasing numbers of cancer patients survive but suffer from long-term effects; thus, exploring unconventional treatments that patients may benefit from is highly relevant. Systematic reviews on energy healing for cancer patients report that research is scarce and mostly of poor quality, with mixed results from quantitative studies on effectiveness, and without significant positive findings from the few high-quality RCTs.6-11 It is not possible to conclude because of the low quality and scarcity of trials7-11 which also implies that the effect sizes are dubious. Some suggest integrating energy healing into conventional care as patient satisfaction seems to be high.12-14 Two recent trials demonstrated an effect on self-reported pain in cancer patients,15,16 but patients and therapists were not blinded, and it is not clear if the researchers were blinded, and if or how the patients were randomized or referred to treatments. One of these studies evaluated the role of self-efficacy in cancer patients before surgery and suggests that the effect is conditional and related to the patients’ level of self-efficacy prior to the Reiki treatment. 16 Qualitative studies have unanimously reported that patients have positive experiences with energy healing.17-22

A mixed-methods study found an apparent discrepancy between negative results based on quantitative data (quality of life with sub-scales) and positive changes reported in qualitative interviews (p. 154). 23 The qualitative data were re-analyzed, and it was concluded that the positive changes reported by interviewees were due to a “redefinition” of their initial problems according to the “clinical reality” of the healing groups (p. 154). 23 While the scope of the study did not encompass the process of redefinition, Glik 23 surmises that expectations became “self-fulfilling prophecies that caused personal events to be interpreted positively” (p. 162). The study found that problems were “psychologized” (p. 161) 23 and redefined as “less serious, less medical, more chronic” (p. 151) 23 than those initially defined. Both Glik’s 23 study and a study by Finkler 24 concluded that patients’ perceptions of afflictions changed and that they were perceived as less troubling. This was also suggested in a study conducted at a healing center. 25 Glik 23 suggested “in-depth monitoring of individuals over time that would have revealed conditions that triggered the initiation of the redefinition process, or how persons who redefined problems were distinct from those who did not: these issues demand further research.” (p. 162).

As there has been a tendency toward discrepancies between findings from quantitative and qualitative studies of energy healing, this qualitative study was designed to describe the experiences and interpretation processes of cancer patients in a pragmatic trial who received energy healing. Although it was anticipated that the patients would report positive outcomes in interviews, as in previous qualitative studies, this study also aimed to gain insight into the interpretation processes of patients over time, as suggested by Glik. 23 The pragmatic trial from which the patients were recruited concluded that there was no significant difference between changes for control groups and intervention groups in the subscales of quality of life, depressive symptoms, mood, and sleep quality in colorectal cancer patients. 26 We focused on the processes of interpretation of cancer patients before, during and after the energy healing treatment and compared the changes reported by patients to the findings of the trial.

Theory

This qualitative study is based on a cultural phenomenological approach developed by Csordas 27 to describe healing processes. The approach is sensitive to cultural contexts and enables a description of what counts as healing for individuals situated in specific social and cultural settings. Csordas demonstrated that the specificity of self-processes is relevant for understanding the complexity of therapeutic effectiveness. This approach is based on insights of the phenomenologist Merleau-Ponty 28 and the practice theory of Bourdieu. 29 This approach holds that embodied and sensory experiences are framed by interpretations related to language and cultural categories. This approach is sensitive to patients’ perceived experiences of problems and their preferred outcomes and changes, whereas the pragmatic trial mainly focused on pre-defined measures. The cultural phenomenological approach is concerned with how (if) a therapy may lead to changes in the orientation of the self and engagement in the world, which in turn may lead to changes in experiences of health and illness. 27 We perceived patients’ elaborations of their experiences and therapeutic processes as results of orientation processes where attentiveness to signs and interpretations are related to the patients’ preconceptions. Four components in the healing processes of the patients were in focus in this study: (1) the patient’s disposition, understood as preconceptions and social network related to the treatment; (2) the patient’s capacity for extraordinary experiences, which they perceive as relevant for health and well-being; (3) the patient’s elaboration of alternatives (in the assumptive world) related to possible changes in their condition; and (4) actualization of change Adapted from Agdal (pp.47-48) 7 and Csordas (pp.72-73). 27

Methods

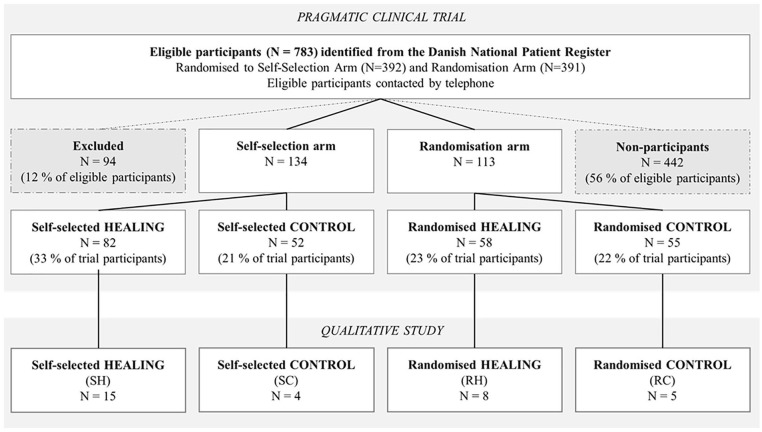

The 32 patients who participated in this study were recruited from a pragmatic trial with 247 participants to test the effectiveness of energy healing (Figure 1). The primary diagnosis was colorectal cancer, and patients had undergone treatment with surgery, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy, and had no evidence of current cancer at the time of inclusion. Patients were randomly stratified into a self-selection or randomization arm prior to initial contact. Eligible participants were mailed a folder containing information about the study, the energy healers in the study, and an informed consent form. They consented to participate in the trial and in this study (Figure 1). The participants in the randomized arm were further randomized to an energy healing intervention (RH) or a control (RC) group, and the self-selection arm chose self-selected healing (SH) or self-selected control (SC). The trial did not involve blinding, because we also aimed to study the potential impact of self-selection versus randomization. 30 The first patients who completed the questionnaires of the overall trial were recruited to this sub-study. This recruitment strategy resulted in an uneven selection of patients from the 4 arms for this sub-study (Figure 1). The patients were interviewed 4 times; before treatment with energy healing, after the first treatment, at the end of the 4 treatments and 2 months after the final treatment. They could choose when they wanted the 4 treatments within 2 months. Energy healers were instructed to conduct their treatments as usual, wherein they intend to transfer energy with or without touching the patient. They were instructed to refrain from offering additional forms of therapy. Most energy healers had training in several types of energy healing, but the majority referred to Reiki as their main approach. The most experienced energy healers tended to combine approaches.

Figure 1.

Patient recruitment.

To prepare the interview guide for patient interviews, and for context, 18 energy healers who participated in the trial and 7 other energy healers were interviewed. The energy healers were asked about their practice and perspectives on illness in general and cancer in particular. They were members of “Healerh-ringen,” a Danish national association for energy healers, that requires its members to undergo at least 200 hours of relevant training. This association was approved by the energy healers who contributed to the study.

In accordance with the theoretical basis, the interview guide for patient interviews covered the above-mentioned 4 components of healing processes. To cover topics related to the 4 components the interviewers invited patients to talk about their health condition and what they expected or experienced to influence their health condition and healing processes, whether they were related to their everyday life or treatments, as well as their expectations and hopes for the future. The interviewers asked open-ended questions and maintained a flow in the conversation by adding cues to invite the patients to elaborate on topics that were relevant to the 4 components of the healing process. We aimed to avoid introducing core metaphors used by the energy healers, such as “energy” or “positive thinking” in the conversations. The patients were asked to be specific about experiences related to everyday life and treatments, and implicitly about how they interpretated signs of the body and possible changes in their experience of health. These topics led to conversations about what it meant to the patients to be healthy and ill and how they understood the treatments and future possibilities. The interview guide was tested in a pilot phase in which 5 patients were interviewed. The majority of the first and last interviews with each patient typically lasted for 1 to 1.5 hours and took place at the patients’ homes. Interviews number 2 and 3 were shorter and conducted over telephone, focusing on the immediate experiences of treatment and potential changes. The interviews were recorded and transcribed soon after they were conducted and then read to prepare the follow-up interviews with each patient. The aforementioned cultural-phenomenological theoretical approach provided the basis for a directed content analysis 31 and allowed the observation of other categories through a first step of open coding. The interviews were coded for each patient in several steps; first, to prepare the follow-up interviews with individual patients, second; reading through all 4 interviews with individual patients for open coding; and third; reading the interviews for each patient for coding based on the cultural-phenological and theory-driven approach. In the second phase, the interviews were read to familiarize with the data, generate codes, search, and review and recognize topics. This initial coding was conducted to avoid bias because of the theory-driven coding, 31 and to specifically avoid excluding themes that were important for patients. Statements were marked and coded using pen and paper, color markers, and tables to keep track of the coding. In the third and theory-driven phase of the analysis, the interviews were reread to identify elements relevant to the themes of the 4 components of the healing process described above. To reduce the risk of bias, analyses of interviews and cases were discussed in the cross-disciplinary research group. Information from the final phase of the coding was entered into a table to keep track of the elements from the interviews for each patient. Patterns that emerged in the work sheet, when comparing the interpretation processes of individual patients with different dispositions, were transferred to the tables in this article.

The protocol adhered to the ethical requirements of the Helsinki Declaration, was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency, and was submitted to the Regional Committee of Research Ethics in Southern Denmark. Participants were informed that they could withdraw their consent at any time without consequences for treatment. The case descriptions were based on individual patients; all patient names were changed to protect their confidentiality.

Patient Interpretation of Signs as Relevant to Healing Processes

The energy healers frequently employed symbolic resources associated with spiritually oriented traditions and stressed psychosomatic causes for cancer. 7 Thus, we expected that a spiritual orientation and acceptance of the energy healers’ etiology of cancer could be relevant for patients with well-developed dispositions, and their engagement in the treatment. In the following, we present patterns observed in experiences of patients who interpreted experiences related to the treatment as extraordinary and changed their attention toward what they perceived as signs of healing. Furthermore, we illustrate some of the typical interpretation processes and traits by presenting 2 individual patients, before describing patterns of those who did not ascribe self-reported improvements to energy healing. Patients who did not ascribe extraordinary experiences to energy healing did not attribute positive changes to the treatment either. Finally, we present comparisons drawn between cancer patients in the intervention and control groups.

Experiences of the Extraordinary, Followed by Changes in Attention

After meeting the energy healers most patients perceived a greater variety of signs as extraordinary and relevant for healing, and their disposition toward the energy healing treatment changed. The interpretation of experiences as extraordinary, prompted attentiveness toward “signs of healing” and “positive changes.” Patients who perceived experiences during treatment with energy healing as extraordinary considered this as the start of healing processes and searched for signs that confirmed healing (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patients Who Ascribed Perceived Health Improvements to Energy Healing Treatment.

| Randomized to healing (RH) or self-selected healing (SH) | Betty (RH) | Erica (RH) | Marge (RH) | Anne (RH) | Vivi (SH) | John (SH) | Eve (SH) | Carol (SH) | Alan (SH) | Mia (SH) | Eddy (SH) | Eric (SH) | Jo (SH) | Ron (SH) | Martin (SH) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 48 | 80 | 68 | 48 | 75 | 50 | 69 | 36 | 78 | 60 | 64 | 70 | 51 | 65 | 58 |

| Ascribed changes to treatment | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Ambivalent regarding changes | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Extraordinary experiences related to treatment | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Incremental healing | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Spiritual orientation | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Previous use of energy healing (EH) | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Previous use of complementary/alternative medicine | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Positive expectations of EH | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Accepting EHs etiology | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Being active and positive as important | X | X | X | X | X |

As observed in Table 1, some traits were common among patients who ascribed perceived health improvement to energy healing; the majority had a spiritual orientation, many had positive expectations toward the energy healing, they accepted the energy healers’ etiology of cancer, and had used complementary or alternative medicine prior to the study. Their disposition seemed to sustain their engagement in energy healing and they showed attentiveness, toward the signs they interpreted as extraordinary and toward perceived health improvements. When the differences in disposition were compared to the subsequent process of case progression, the following pattern emerged: when cancer patients developed a disposition toward the energy healing it influenced their attention and attribution of meaning to “signs of healing.” Depending on their frame of reference, some cancer patients experienced particular incidents as highly meaningful and extraordinary.

Sensory experiences perceived as extraordinary were the most important source of authentication of the value of the treatment by those who ascribed perceived positive health changes to it. Additionally, some patients experienced that the energy healers had an extraordinary intuition, and some found that they had an extraordinary ability to communicate with the dead. Others doubted the energy healers’ claims and intuition, and whether their experiences were extraordinary or not. The cancer patients did not discuss if their sensory experiences were “real.” However, they discussed whether the energy healers’ ability to communicate with the dead was “real” and whether their own visions during the treatments, for example seeing a dead relative, were “real” or products of imagination or coincidence. The cancer patients who had a well-developed disposition toward energy healing perceived signs of the body, including pain, as unambiguous signs of “the energy working.”

In some cases, cancer patients changed their interpretations of incidents from extraordinary to ordinary, and this determined whether patients would ascribe perceived health changes to the treatment with energy healing. Views of “extraordinariness” over time, and different patients perceived different signs of “extraordinariness.” Those in the intervention groups with well-developed dispositions toward the treatment were more prone to describe bodily experiences as extraordinary, including sensations of relaxation, warmth, coldness, pain, lightness, heaviness, falling asleep and new afflictions. Some of the afflictions reported by those in the intervention groups can be categorized as medically alarming symptoms, for instance symptoms of relapse of cancer, whereas others appeared to be symptoms of self-limiting conditions, such as mild respiratory infections or pain that came and went away. Contrary to those who perceived such bodily experiences as extraordinary, others described bodily experiences as ordinary. We will return to their descriptions in the section about patients who did not ascribe changes to the energy healing. Our analysis is based on their interpretations that they shared in the interviews; thus, it is a premise that it is not feasible to compare the actual experiences, despite the presence of patterns in the interpretations.

When cancer patients in the intervention groups directed their attention toward signs that they had learned to perceive as potential indicators of healing, they also started to explore possible improvements in their health, changes in the character of afflictions, and the meaning of new afflictions. Cancer patients in the intervention groups frequently interpreted afflictions as positive signs of healing processes. Pain during or after treatment with energy healing was typically considered a positive sign, rather than a side effect or a coincidence. When cancer patients who underwent energy healing interpreted pain as a positive sign, it was in some cases followed by a process of re-orientation that led to a change in the experience of the quality of pain. Some mentioned a change in “focus” and reported that the afflictions did not have the same consequences for their functioning in everyday life. For some, this implied a shift in the habitual mode of attention. Others changed their disposition and habitual mode of attention and became attentive to a wider range of signs perceived as signs of healing. The experiences that these cancer patients perceived as extraordinary fueled their search for a wide range of signs of healing. Cancer patients who ascribed changes to the energy healing treatment were attentive to a wider range of signs than before that confirmed the presence of a healing process, linked to their experiences of the extraordinary. Cancer patients who did not report extraordinary experiences related to the treatment did not ascribe positive changes to the treatment, and they did not report a spiritual orientation.

Most cancer patients in the intervention groups welcomed the self-help techniques suggested by the energy healers, including “positive thinking.” Some reported that their energy healer said that they needed to work on the psychosomatic causes for illness. The cancer patients who used energy healing for the first time picked up terms and techniques suggested by the energy healers, which led to changes in their assumptive world. The most common “self-help” techniques were exercises to change ways of thinking or focus. Some learned breathing techniques or meditation. Patients who embraced these techniques used them to explore processes of re-orientation, changing their habitual mode of attention by actively working on their focus, thereby producing and maintaining processes experienced as positive. Some of the cancer patients in the intervention groups who practiced “positive thinking” reported that they were able to improve their level of functioning in everyday life and that the energy healers had provided them hope. Regardless of whether they reported positive treatment experiences, some cancer patients who underwent energy healing reported additional factors that were important for their healing, such as social support, being in nature, and being positive and active.

The focus on “positive thinking” and the idea that cancer could result from psychosomatic causes led some patients to attempt to avoid “negative thoughts.” Consistent with the etiology of the energy healers, some patients also mentioned that social interaction could have a negative effect on their healing process.

First case description: An experienced user of energy healing

In the first interview, Betty talked about her knowledge of energy healing and referred to energy healers as “channeling” the “power of God.” She was familiar with the energy healers’ models of illness and disease, and consistent with this, she was confident that she had developed cancer because she feared getting it. She reported that “negative thinking” could cause cancer, because she had heard this from an energy healer and read it in the book “Heal your life” by Louise Hay. This book states that “negative thought patterns” create illnesses. Hence, to “think more positively” became part of Betty’s strategy to enhance health. She referred to herself as religious and had a spiritual orientation related to mood and motivations in her everyday life. Betty said that she hoped the treatment would help her oversensitive fingers and that she suffered from “chronic stress and something in the stomach.” Her previous experiences with energy healing meant that her ideas were not only images-in-consciousness, but also embodied images related to haptic memories. Her disposition provides a frame of reference that influences both the habitual mode of attention and the interpretation of her experiences. Overall, Betty’s disposition was informed by energy healing concepts.

Betty reported that she felt that “something happened” during the treatments, and she felt occasional pain. She ascribed sensory experiences during and after the treatment to the “energy working,” and interpreted them as positive signs. When she fell ill 15 days after treatment, she reported this as a positive sign and related it to the treatment. At the outset she had an image of “the power of God” and “the healer’s energy.” Such embodied images can take on a presentational immediacy when she perceives experiences related to the treatment. She objectifies sensory experiences, not only as “something happening,” but as the presence of “the power of God,” along with an authentication of the abilities of the energy healer. According to Betty, when the energy healer stated that she could sense problems in her neck and back, Betty perceived it as a demonstration of intuitive knowledge. While Betty and the energy healer paid attention to an area that had once been injured, Betty sensed the pain reoccurring. She interpreted this as a sign of healing. Betty mentioned that her attention changed because of the influence of the energy healer.

According to Betty, several new afflictions were signs that the energy was working and healing processes had started, which included a sudden onset of illness. She did not refer to afflictions as coincidental or side effects, or irrelevant to her cancer rehabilitation. Betty said that she attempted to create more “positive thought patterns” and that her “fear” had caused cancer. Betty said she felt happier in the final interview and stated, “I doubt that I have any problems any longer.” She was sure that the energy healing had contributed to a positive healing process and that there were positive changes; however, in the same interview, she was uncertain about the results. Her descriptions seemed contradictory, which made it difficult to summarize the final changes. She said that afflictions were “gone” and “still there” in the same interview. This may partly be related to a change in the habitual mode of attention; she said she did not “dwell on” the pain any longer and experienced it differently.

Second case description: A man who learned to work on himself

In contrast to Betty, Martin did not have a highly developed disposition toward the treatment. He referred to his father-in-law, who reportedly had tried energy healing and experienced that the healer had extraordinary intuitive knowledge. Martin was somewhat concerned about what might happen during the treatment and had never considered alternative therapies. In the first interview, before the treatment, Martin stated that he had been surprised that he got cancer. He said he suspected that the cancer might have developed due to “genetic weakness” or toxins, because he had followed advice from experts: he had exercised every day, followed a healthy diet and consumed very little alcohol, and never smoked. Later he reported that the energy healer told him that negative thinking could have caused the cancer and that this made sense to him. He developed trust in the energy healer, who reportedly had “a whole textbook” about the causes off cancer and encouraged him to practice “positive thinking.”

His trust in the energy healer was reinforced by the experiences Martin described as extraordinary. During the first treatment, he had been asked to relax while being wrapped up in blankets. He reported that he had felt warmth and fallen asleep so that he was “gone” throughout the treatment. He described his sleep as extraordinary. The healing session involved guided meditation, wherein the energy healer encouraged him to meet an angel. The image of the angel was familiar to him; it took on an experiential presence, as he “was gone that moment” when he met the angel, he said. Following the energy treatments, he reported dizziness, tiredness and had aching limbs as if he had a flu. He therefore went to bed and recovered after a couple of days. Martin reported that the energy healer had explained to him that the ailments could be due to the “energies working,” but that he had been skeptical until a friend told him that this was a common reaction. After his friend validated the energy healers’ suggestion, Martin said he believed that the illnesses after the treatments were signs that the “energy was working.”

Martin said that the energy healer encouraged him to ignore the pain and focus on “I can do it” when he performed practical tasks and sports. The interviews showed that his trust in the healer grew throughout the 4 months; the energy healer motivated him to attempt to change his focus toward a more positive mindset, thus, altering his habitual mode of attention. Martin found that the techniques proposed by the energy healer made a difference in his daily life; he experienced positive changes when he followed the energy healers’ advice. He discussed specific activities with the energy healer, for instance that he could only run short distances before nerve damage in his feet became too painful. This advice pertained to explorations of the processes of re-orientation, by actively working to change his habitual mode of attention, by monitoring feelings and thoughts and by consciously trying to produce and maintain processes of positive changes. Whereas he focused on his problems in the first interview, Martin gradually demonstrated a different orientation in the subsequent interviews; he more frequently interpreted ailments that appeared after the treatments as signs of healing.

Martin changed his understanding of cancer and, accordingly, his strategies to avoid relapse and regain health. He said that he tried to think more positively and decided to see the energy healer “for the rest of his life” to avoid ill health. While Betty already shared the energy healer’s understanding of cancer from the outset, Martin found new health-seeking strategies and learned to “work on himself” by means of “positive thinking.” Martin affirmed that he managed to take more control of his attention and way of thinking; this helped him better manage tasks such as running and handling small tools. He said that he felt more relaxed and that his wife found him less irritable and in a better mood. Martin appreciated that he could discuss his problems with the energy healer and get suggestions on how to address them. The suggestions from the healer seemed to help him change his habitual mode of attention so that he could ignore pain until it “went away.” From the first interview to the last, 4 months later, Martin actively tried to make changes in his habitual mode of attention.

Martin and Betty reported that their focus had changed and they experienced pain differently after the energy healing, although neither said that their problems had disappeared. Both were attentive to “signs of healing” and interpreted experiences that could be perceived as illness, such as flu, as signs of healing processes. Their orientation processes, and thus, their experiences, varied in accordance with their dispositions toward the energy healing treatment.

Participants Who Did Not Ascribe Changes to Energy Healing

Most patients in the intervention group ascribed the perceived healing processes to energy healing, but 5 out of the 23 patients did not, and 3 patients were ambivalent (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patients Who Did Not Ascribe Change to Treatment or Were Ambivalent.

| Patients randomized to healing (RH); randomized to control (RC); self-selected healing (SH); or self-selected control (SC) | Ella (RH) | Andy (RH) | Evan (RH) | Ben (SH) | Bo (SH) | Jenny (SH) | Bridget (SH) | Grace (SH) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 69 | 66 | 71 | 54 | 58 | 60 | 60 | 55 |

| Experienced positive changes | X | X | X | X | ||||

| No changes ascribed to treatment | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Related changes to treatment | Ambivalent | Ambivalent | Ambivalent | |||||

| Extraordinary experiences related to treatment | Ambivalent | Ambivalent | Ambivalent | |||||

| Incremental healing | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Spiritual orientation | ||||||||

| Previous use of energy healing (EH) | ||||||||

| Previous use of complementary/alternative medicine | X | X | X | |||||

| Positive expectations to energy healing | X | X | ||||||

| Accepted EHs etiology before or after treatment | X |

Five patients did not interpret anything related to the energy healing treatment as “extraordinary.” The 3 patients who were ambivalent regarding whether to ascribe perceived healing processes to the treatment, were also ambivalent regarding whether their experiences related to the energy healing treatment sessions had been extraordinary. In the final interview, these 3 patients concluded that their health did not improve due to the treatment and that their experiences during the treatment were not extraordinary after all. Notably, the changes in interpretations of experiences, whether extraordinary or not, corresponded to the patients’ changing interpretation of whether they had improvements that could be ascribed to the treatment. This seem to indicate that the perception of “extraordinariness” is related to the interpretations and the disposition of patients. They develop their dispositions without being conscious about how this affects their interpretations; the development of their disposition goes beyond the beliefs they are aware of. Two of the patients who expressed ambivalence regarding their experiences developed their disposition toward the treatment during the project period, while simultaneously familiarizing themselves with the energy healers’ ideas about the causes off cancer. In the last interview, one of them stated that she had learned from the energy healer that trauma was the reason for her cancer. This implied a change in disposition toward the treatment, and they both reported that they would continue the energy healing treatment after the research project.

These 8 patients did not have a well-developed disposition toward the energy healing treatment at the time of the first interview, they had not used energy healing previously, they were not familiar with the treatment or the associated etiologies, and they did not have a spiritual orientation.

Patients in Control and Intervention Groups

None of the interviewed patients in the control groups expressed disappointment that they did not undergo energy healing. While patients in the intervention groups interacted with energy healers and were exposed to their practices and their etiology of cancer, patients in the control group agreed to not use energy healing during the period of the pragmatic trial. Most of the interviewed cancer patients in this study reported perceived improvements, regardless of whether they were in the energy healing intervention or a control group. The patients in the control groups did not include any afflictions as signs of healing, in contrast to patients in the intervention groups. Cancer patients in the energy healing groups ascribed positive changes to the energy healing in the final interview, and those in the control groups considered various aspects of their life as important for their improvement. Most patients in the control group considered 3 aspects important for their recovery; experience of social support, being in nature or with animals, and being active and thinking positively. Some of the cancer patients in the energy healing groups mentioned the same elements, but there were some differences in how they related to these 3 aspects.

The cancer patients in the control group mentioned social support from family, friends, and the local community. Contrary to the control group patients’ report of social support, some patients in the intervention groups mentioned social interaction as a possible negative influence on their health. The fear of negative consequences of social interaction on their health in general and on cancer symptoms, as observed among some cancer patients in the intervention groups, may have reduced their ability to utilize social support.

Most cancer patients in the intervention groups reported that the energy healers suggested useful techniques for them to “work on themselves,” such as being positive and active, and being in nature, whereas the cancer patients in the control groups referred to these as their own strategies.

Cancer patients in both the control and in the intervention groups mentioned being in nature as important for their healing process and well-being. However, patients in the intervention groups frequently referred to being in nature as advice from the energy healers. The cancer patients in the intervention groups seemed more ambivalent regarding the impact of being in nature than those who chose to do so without referring to energy healers. Their communication with energy healers who introduced new ways to understand cancer, also involved re-interpretations within their everyday lives, regarding new options for healing as well as new perceptions of risk. The patients in the control groups were not exposed to etiologies and practices that were new to them to the same extent as the patients who underwent energy healing. This may explain why their attitudes toward treatments and other factors that might influence their healing processes were more stable than for those who consulted with the energy healers and understood cancer in new ways.

When cancer patients, regardless of the group, believed that certain practices could contribute to their improvement, it caused changes in their assumptive world and their attention. These changes lead them to search for signs of healing. Some cancer patients developed trust toward the energy healers, their disposition changed, and they continued to seek out energy healing after the project, whereas cancer patients in the control group did not change their disposition toward the energy healing treatment.

Some cancer patients who received energy healing changed their perception of cancer, signs of healing, and beliefs, and others expressed doubt and ambiguity. Some cancer patients perceived new “risks” that could affect their health and new ways to take responsibility by thinking and acting to promote health. Meetings with energy healers strengthened some cancer patients’ spiritual orientation, and cancer patients with a spiritual orientation were more prone to report perceived healing processes consistent with the etiology of energy healers.

Discussion

The present study provided data from repeated interviews with cancer patients who participated in a pragmatic trial on energy healing. The results elucidate the findings from the pragmatic trial and previous research by exploring subjective experiences of healing as orientation processes in the control and intervention groups. The investigation of orientation processes provided specific descriptions of changes in cancer patients’ understanding of cancer and their perceptions regarding signs of progression toward improved health. This influences the dynamics of patients’ decision-making and their perceptions of risk.

While previous qualitative studies refer to patients’ positive experiences,17-22 this study found additional changes for the intervention groups. The findings of this study do not contradict the results of the trial wherein the patients were recruited 26 but add insights to the role of mediators and the complexity of healing processes. The study conducted an in-depth monitoring of individuals over time to reveal conditions that trigger the initiation of the redefinition process, as suggested in a previous study. 23 By interviewing the cancer patients before, during, and after the treatment period, we identified changes in their disposition toward energy healing that led to changes in the habitual mode of attention, perception, and framing of experiences as signs of healing. The specific processes of patients’ interpretation were not merely the cognitive processes of “redefinition,” as suggested by Glik, 23 but embodied processes. The processes involved sensing and perceiving the signs of the body, while searching for signs of healing. Patients reported that energy healers encouraged them to pay attention to their bodies, along with being aware of a wide variety of signs of healing. The focus on the body is known from other studies on CAM.30,32 The patients shared reflections to some extent about whether to interpret auditory or visual signs (ie, dreaming about something, a picture, or a story) as “real” signs of healing, but they rarely shared reflections or doubts about signs of their bodies. A wide range of bodily signs were perceived as univocal signs of healing, including pain, although some were also ambivalent about the meaning. Previous studies also found that patients who use energy healing report that they perceive afflictions as less troubling and less serious.23,25 The results of this study show that signs, including afflictions, can be interpreted in different ways by patients, and that signs that for some would be seen as signs of deteriorating health, for example pain or a tumor, were unequivocal signs of healing for others. Patients’ interpretations of signs of illness and afflictions are closely linked to their dispositions. Re-interpretation of commonly perceived signs of illness, as signs of healing, has been referred to as “holistic sickening” in previous studies of CAM. 33 Many of the patients who consulted energy healers as part of the trial changed their perception of cancer, like in other studies on CAM.34,35 The energy healers taught the cancer patients to “work on themselves” using techniques like “positive thinking” and “affirmations” to improve their health and avoid relapses related to “stress,” “negative relations,” or “past traumas.”

However, the options provided by energy healers to cancer patients can be both a source of empowerment, because they can take “responsibility” for their illness, and a burden, as found in previous studies of energy healing.25,33,36 This mirrors the findings of the pragmatic trial that found no significant changes in outcomes, such as depression and quality of life. 26 Patients who developed or strengthened a spiritual orientation were more prone to accept the etiology of the energy healers, followed by other changes. The role of spirituality in coping with illness is controversial; some studies highlight spirituality as a source of coping, whereas others find that some aspects of spirituality may cause distress.33,36-38 Changes in patients’ understanding of the causes of cancer were often followed by a sentiment that they ought to change their health behavior accordingly by following the advice from the energy healers, that is to think positively or avoid relations that may have negative energy. The flexibility of patients’ conceptions of cancer has been documented.25,34,37,39,40 In addition to the changes in the perception of cancer, the interviews showed changes in the perception of signs of healing that illustrate the complexity of the experiences of healing processes. Some patients feel empowered and equipped with alternative strategies to improve their health. Although, the energy healers provided hope, meaning, and tools to work on themselves for some patients, other changes gave cause for concern. For instance, some patients learned that the continued use of energy healing and positive thinking would be necessary to avoid the relapse of the illness, and some perceived ailments as signs of healing. Consequently, some patients postponed seeking medical assistance. Treatment delays have been associated with use of alternative therapies.41,42 The reduced trust in medical advice and changes in strategies to enhance health affect health-seeking strategies and treatment choices, as well as other aspects of life. A study of European patients who used CAM found that 14.9% used energy healing exclusively, which is the highest percentage of exclusive use of a CAM modality. 43 We also observed that some cancer patients had a reduced ability to utilize social support because they feared that some social relations could have a negative influence on their healing, whereas social support was considered as important by most cancer patients in the control groups. This may indicate that the re-orientation toward the etiology of the energy healers led to ambivalence regarding factors that might enhance their health. In addition to expressing ambivalence regarding social interaction and support, the patients in the intervention group tended to be ambivalent regarding the advice from energy healers to spend time in nature for healing, whereas others considered nature to be important for their well-being without ambivalence. The idea of nature as healing has a long history in Scandinavian countries. 44 The role of nature for cancer patients is described in a study from neighboring Sweden, where the researcher asks if nature takes on the same role as “God” for believers. 45

The findings of this study indicate that cancer patients who use energy healing may change their health seeking strategies accordingly, consistent with previous studies that reported that users of energy healing tended to consider their illnesses as less serious after the treatment.23,24 The notion that “It can do no harm” is widespread among patients who use CAM and CAM practitioners. 46 Patients who pursue energy healing change their understanding of cancer and their strategies to improve health, which can result in treatment delays. This finding indicates the need for improved patient information. It has previously been established that there is strong reticence among cancer patients to disclose the use of CAM to their oncologists. A research group in Italy achieved promising results when a group of oncologists proactively established information meetings regarding CAM and cancer. 40 These meetings increased patients’ adherence to the advice of oncologists, and influenced their perception of cancer, symptom interpretation and attribution, perception of risk, and their health seeking strategies. Strategies for health promotion, patient education, and communication between health personnel and patients should be examined.

Positive Patients, Positive Thinking or Positive Changes?

In conclusion, the majority of cancer patients, both in the control and intervention groups, reported that they perceived positive changes in their health. However, some experiences reported by patients in the intervention groups were a cause for concern. Patients who underwent energy healing interpreted both previous and new afflictions as positive signs. The findings of this study regarding interpretation processes add to previous research on energy healing. Previous qualitative studies have unanimously reported subjective experiences of improvement that were unsustained by high quality trials. This study found that although “extraordinary” experiences followed by perceived improvements are considered highly meaningful by patients, researchers need to exercise caution when representing patients’ subjective experiences of “positive changes” without further contextualization. The changes in patients’ perceptions of health and illness influenced what they considered relevant strategies to improve health and their ability to utilize support. The impact of use of alternative therapies on cancer patients’ health-seeking strategies should be followed up with further research, as this may have implications in health promotion and patient information strategies. Notably, patients’ perceptions of sensory experiences were the most important source of authentication of the value of the energy healing treatment, by patients who ascribed perceived positive changes to their health to this treatment.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The study was funded by the Danish council for strategic research (and registered before data collection at clinicaltrials.gov; NCT01434264).

ORCID iD: Rita Agdal  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0314-8540

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0314-8540

References

- 1. Molassiotis A, Fernández-Ortega P, Pud D, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in cancer patients: a European survey. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:655-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Buckner CA, Lafrenie RM, Dénommée JA, Caswell JM, Want DA. Complementary and alternative medicine use in patients before and after a cancer diagnosis. Curr Oncol. 2018;25:e275-e281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Horneber M, Bueschel G, Dennert G, Less D, Ritter E, Zwahlen M. How many cancer patients use complementary and alternative medicine: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Integr Cancer Ther. 2012;11:187-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pedersen CG, Christensen S, Jensen AB, Zachariae R. Prevalence, socio-demographic and clinical predictors of post-diagnostic utilisation of different types of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in a nationwide cohort of Danish women treated for primary breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:3172-3181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lee SM, Choi HC, Hyun MK. An overview of systematic reviews: complementary therapies for cancer patients. Integr Cancer Ther. 2019;18:1534735419890029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Agdal R, von B, Hjelmborg J, Johannessen H. Energy healing for cancer: a critical review. Forsch Komplementmed. 2011;18:146-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Agdal R. Energy Healing for Cancer Patients in a Pragmatic Trial. An Anthropological Study of Healing as Self-Processes. PhD thesis, University of Southern Denmark; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jain S, Boyd C, Fiorentino L, Khorsan R, Crawford C. Are there efficacious treatments for treating the fatigue-sleep disturbance-depression symptom cluster in breast cancer patients? A rapid evidence assessment of the literature (REAL©). Breast Cancer. 2015;7:267-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jain S, Mills PJ. Biofield therapies: helpful or full of hype? A best evidence synthesis. Int J Behav Med. 2010;17:1-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gonella S, Garrino L, Dimonte V. Biofield therapies and cancer-related symptoms: a review. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2014;18:568-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rao A, Hickman LD, Sibbritt D, Newton PJ, Phillips JL. Is energy healing an effective non-pharmacological therapy for improving symptom management of chronic illnesses? A systematic review. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2016;25:26-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bardia A, Barton DL, Prokop LJ, Bauer BA, Moynihan TJ. Efficacy of complementary and alternative medicine therapies in relieving cancer pain: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5457-5464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pierce B. The use of biofield therapies in cancer care. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2007;11:253-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jackson E, Kelley M, McNeil P, Meyer E, Schlegel L, Eaton M. Does therapeutic touch help reduce pain and anxiety in patients with cancer? Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12:113-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gentile D, Boselli D, O’Neill G, Yaguda S, Bailey-Dorton C, Eaton TA. Cancer pain relief after healing touch and massage. J Altern Complement Med. 2018;24:968-973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chirico A, D’Aiuto G, Penon A, et al. Self-efficacy for coping with cancer enhances the effect of Reiki treatments during the Pre-Surgery phase of breast cancer patients. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:3657-3665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kelly AE, Sullivan P, Fawcett J, Samarel N. Therapeutic touch, quiet time, and dialogue: perceptions of women with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004;31:625-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Barlow F, Lewith GT, Walker J. Experience of proximate spiritual healing in women with breast cancer, who are receiving long-term hormonal therapy. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14:227-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Barlow F, Walker J, Lewith G. Effects of spiritual healing for women undergoing long-term hormone therapy for breast cancer: a qualitative investigation. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;19:211-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hallett A. Narratives of therapeutic touch. Nurs Stand. 2004;19:33-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Birocco N, Guillame C, Storto S, et al. The effects of Reiki therapy on pain and anxiety in patients attending a day oncology and infusion services unit. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2012;29:290-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kirshbaum MN, Stead M, Bartys S. An exploratory study of reiki experiences in women who have cancer. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2016;22:166-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Glik DC. The redefinition of the situation: the social construction of spiritual healing experiences. Sociol Health Illn. 1990;12:151-168. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Finkler K. Spiritualist Healers in Mexico: Successes and Failures of Alternative Therapeutics. Praeger Publishers; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 25. McClean S. ‘the illness is part of the person’: discourses of blame, individual responsibility and individuation at a centre for spiritual healing in the north of England. Sociol Health Illn. 2005;27:628-648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pedersen CG, Johannessen H, Hjelmborg JV, Zachariae R. Effectiveness of energy healing on quality of life: a pragmatic intervention trial in colorectal cancer patients. Complement Ther Med. 2014;22:463-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Csordas TJ. The Sacred Self: A Cultural Phenomenology of Charismatic. Healing University of California Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Merleau-Ponty M. Phenomenology of Perception. Northwestern University Press; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bourdieu P. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge University Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Baarts C, Pedersen IK. Derivative benefits: exploring the body through complementary and alternative medicine. Sociol Health Illn. 2009;31:719-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277-1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pedersen IK. Striving for self-improvement: alternative medicine considered as technologies of enhancement. Soc Theory Health. 2018;16:209-223. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sered S, Agigian A. Holistic sickening: breast cancer and the discursive worlds of complementary and alternative practitioners. Sociol Health Illn. 2008;30:616-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wortmann JK, Bremer A, Eich HT, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by patients with cancer: a cross-sectional study at different points of cancer care. Med Oncol. 2016;33:78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wode K, Henriksson R, Sharp L, Stoltenberg A, Hök Nordberg J. Cancer patients’ use of complementary and alternative medicine in Sweden: a cross-sectional study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2019;19:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pedersen CG, Christensen S, Jensen AB, Zachariae R. In God and CAM we trust. Religious faith and use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in a nationwide cohort of women treated for early breast cancer. J Relig Health. 2013;52:991-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schreiber JA, Brockopp DY. Twenty-five years later—what do we know about religion/spirituality and psychological well-being among breast cancer survivors? A systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:82-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Visser A, de Jager Meezenbroek EC, Garssen B. Does spirituality reduce the impact of somatic symptoms on distress in cancer patients? Cross-sectional and longitudinal findings. Soc Sci Med. 2018;214:57-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shahab L, McGowan JA, Waller J, Smith SG. Prevalence of beliefs about actual and mythical causes of cancer and their association with socio-demographic and health-related characteristics: findings from a cross-sectional survey in England. Eur J Cancer. 2018;103:308-316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bozza C, Gerratana L, Basile D, et al. Use and perception of complementary and alternative medicine among cancer patients: the CAMEO-PRO study : Complementary and alternative medicine in oncology. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2018;144:2029-2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Malik IA, Gopalan S. Use of CAM results in delay in seeking medical advice for breast cancer. Eur J Epidemiol. 2003;18:817-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Davis GE, Bryson CL, Yueh B, McDonell MB, Micek MA, Fihn SD. Treatment delay associated with alternative medicine use among veterans with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2006;28:926-931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kemppainen LM, Kemppainen TT, Reippainen JA, Salmenniemi ST, Vuolanto PH. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in Europe: health-related and sociodemographic determinants. Scand J Public Health. 2018;46:448-455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mellemgaard S. Kroppens Natur. Sundhedsoplysning Og Naturidealer i 250 År Museum Tusculanum. University of Copenhagen; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ahmadi F. Culture, Religion and Spirituality in Coping. The Example of Cancer Patients in Sweden. Vol. 53. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis Studie Sociologica Upsaliensis; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pedersen IK. ‘It can do no harm’: Body maintenance and modification in alternative medicine acknowledged as a non risk health regimen. Soc Sci Med. 2013;90:56-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]