Abstract

The study examined how friendships among women in recovery from substance use disorders are related to individual resources (e.g., social support, self-esteem, and hope) and empowerment (e.g., power and optimism). Findings from a path analysis of 244 women in recovery revealed that friendships among women were positively related to individual resources; that is, the stronger the relationships with other women, the higher women perceived their resources to be. Further, individual-level resources mediated the relations between friendships and empowerment, with higher levels of individual resources related to higher levels of empowerment constructs of power and optimism. Results point to the importance of developing and sustaining empowering relationships for women in recovery. Findings have implications for gender-specific treatment practices and recommendations impacting substance use recovery outcomes.

Keywords: friendships, empowerment, substance use disorders, recovery, path analysis

The tendency for both women and men to have more same-gender friendships than cross-gender friendships over their life span is well documented (Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Although women and men conceptualize their ideal friendships in similar ways, women tend to rate their same-gender friendships higher in intimacy, social support, nurturance, overall quality, and satisfaction (Bank & Hansford, 2000). Women are also less likely to nominate their spouse as their closest friend and more likely to nominate other women in their networks than men (Fuhrer & Stansfeld, 2002). Similarly, women report receiving more support from friends, whereas men report receiving more support from spouses (Schuster et al., 1990). Gender identity reflects how individuals understand themselves in relation to cultural meanings ascribed to gender and how they behave (Wood & Eagly, 2015). Thus, gender-based socialization and norms can explain the aforementioned differences in same-gender friendship patterns, including why women are more emotionally expressive in these types of relationships, and why men are more likely to reserve intimacy for their sexual or romantic partners (Reis et al., 1985).

Friendships among women can provide critical social resources and promote overall wellness, feelings of self-worth, and empowerment. Findings from studies that examine these relationships among women indicate that the quality of friendship support is more important than the mere number (Billings & Moos, 1984). Supportive friendships, which are characterized by intimacy, nurturance, loyalty, and prosocial behaviors, are associated with heightened psychological and physical well-being (Cable et al., 2013).

The self-in-relation theory (Surrey, 1991) proposes that women’s self-concept is largely relational; that is, “women’s sense of self becomes very much organized around being able to maintain affiliations and relationships” (Miller, 1976, p. 83), particularly with other women. The theory further states that relationships that enhance women’s sense of self exhibit mutuality and empathy. Covington (2007) described these as relationships in which women can share their feelings and thoughts and meet one another at a cognitive and affective level. The self-in-relation theory suggests that women that can establish mutual and empathetic relationships can achieve a higher sense of worth and empowerment (Kaplan, 1986). Taken together, relationships with other women are highly important and influential for women, both to their sense of self and quality of life outcomes.

Empowerment and Individual-Level Resources

The marginalization and oppression of women manifest in society through policies, norms, and systems that limit women’s ability to make choices and gain power (Cattaneo & Chapman, 2010). Therefore, empowerment entails increasing access to resources to promote marginalized people’s well-being. Given that power is inherently a social construct, many scholars conceptualize empowerment as both developed and exercised through one’s relations with others (Christens, 2012; Prilleltensky & Gonick, 1994). For instance, Surrey (1987) defined empowerment as “the motivation, freedom, and capacity to act purposefully, with the mobilization of the energies, resources, and strengths, or powers of each person, through a mutually, relational process” (p. 2). Similarly, Christens (2012) defined relational empowerment as emerging in transactional spaces between individuals. Relational empowerment includes providing social and emotional support as people struggle, facilitating critical awareness of systems, guiding one another as well as utilizing interpersonal networks to mobilize and motivate people.

Optimism and empowerment are highly associated with one another (Campbell & Martinko, 1998). Optimism is the tendency to have generalized positive expectancies for outcomes (Glanz & Schwartz, 2008) and perceptions of control over the future (Rogers et al., 1997). Rogers and colleagues (1997) found optimism to be one of five subordinate factors of empowerment. Campbell and Martinko (1998) found those scoring high on empowerment either had more optimism or viewed negative situations as controllable. Conversely, individuals who scored low on empowerment were most associated with pessimism or the worldview that negative situations are uncontrollable. Moreover, women’s optimistic expectancy that their actions will be successful is essential for them to take action in seeking their goals (Diener & Diener, 2009).

Social support, hope, and positive self-esteem are valuable individual resources that may serve as pathways through which friendships among women lead to empowerment. Social support, which embodies resources obtained from interpersonal relationships, can come in the form of the provision of information, tangible resources, emotional guidance, and positive appraisal (Cohen & McKay, 1984). Hope is considered to have a salient influence on motivation and behavior and is characterized by three dimensions (a) the perception of successful agency, (b) available pathways to achieve one’s goals (Snyder et al., 1991), and (c) having opportunities found in the environmental context that facilitate goal attainment (Stevens et al., 2014). Women with higher levels of hope can better deal with challenges and generate more strategies to attain their goals. Hope is also contingent on the opportunities and obstacles present in the environment that can either hinder or facilitate the achievement of goals. Friendships among women can contribute to greater hope by identifying possible pathways for overcoming challenges, bolstering perceptions of having greater agency, and providing resources (Parker et al., 2015). Lastly, self-esteem is a person’s self-reflection of their worth and abilities characterized by two dimensions self-liking and self-competence (Tafarodi & Milne, 2002). Friendships can also increase self-esteem by providing positive appraisals, which help women develop positive self-perception and higher confidence in their abilities to overcome obstacles. In summary, friendships with other women can increase levels of social support, hope, and self-esteem, and these individual resources seem to be directly related to women’s empowerment. Specifically, women with higher levels of individual resources may perceive themselves as having greater power and more realistically optimistic about achieving positive outcomes despite obstacles.

Empowering Settings

Friendship formation is highly dependent on the social context. Allan (1979) theorized that friendships are both constructed and organized in a social setting. In particular, empowering settings can promote the development of supportive friendships among women. Neal (2014) defined empowering settings as ones in which (a) relationships allow for the exchange of resources, and (b) power is equitable among members. According to Christens (2012), empowering settings have been conceptualized as being collaborative, having distributed leadership among community members, and having an emphasis on interpersonal relationships. The focus on interpersonal relationships broadens community members’ understanding of the social world, increases motivation to get and remain involved, increases confidence, and integrates new members into the community (Christens, 2012). Moreover, empowering settings tend to have a variety of tenure among members with the shared value of passing on the legacy through mentorship and guided/structured participation between older participants and newer members to increase capacity and reinforce group solidarity (Christens, 2012).

Empowering settings might be particularly important for women, who experience many gender-based forms of marginalization evidenced by the gender pay gap, high rates of intimate partner and gender-based violence, and workplace harassment and discrimination. Women experience further marginalization at the intersections of their many identities (e.g., race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, documentation status, disability status, mental health; Crenshaw, 1991). Looking closely at one intersection of experience and identity, women with substance use disorders experience greater psychiatric comorbidities and greater barriers to treatment (Greenfield et al., 2007; McHugh et al., 2018; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019). The literature points to gender-specific differences concerning substance use patterns, the onset of substance use, psychosocial characteristics, subjective experiences, the physiological impact of substance use, and treatment utilization (Azzi-Lessing & Olsen, 1996). Additionally, research has documented the inequitable federal spending on alcohol and substance treatment, indicating women receive a small fraction of the federal dollars compared to men (Azzi-Lessing & Olsen, 1996). Compared to men, women have significantly lower entry rates into treatment, retention, and completion of treatment (Krueger et al., 2022).

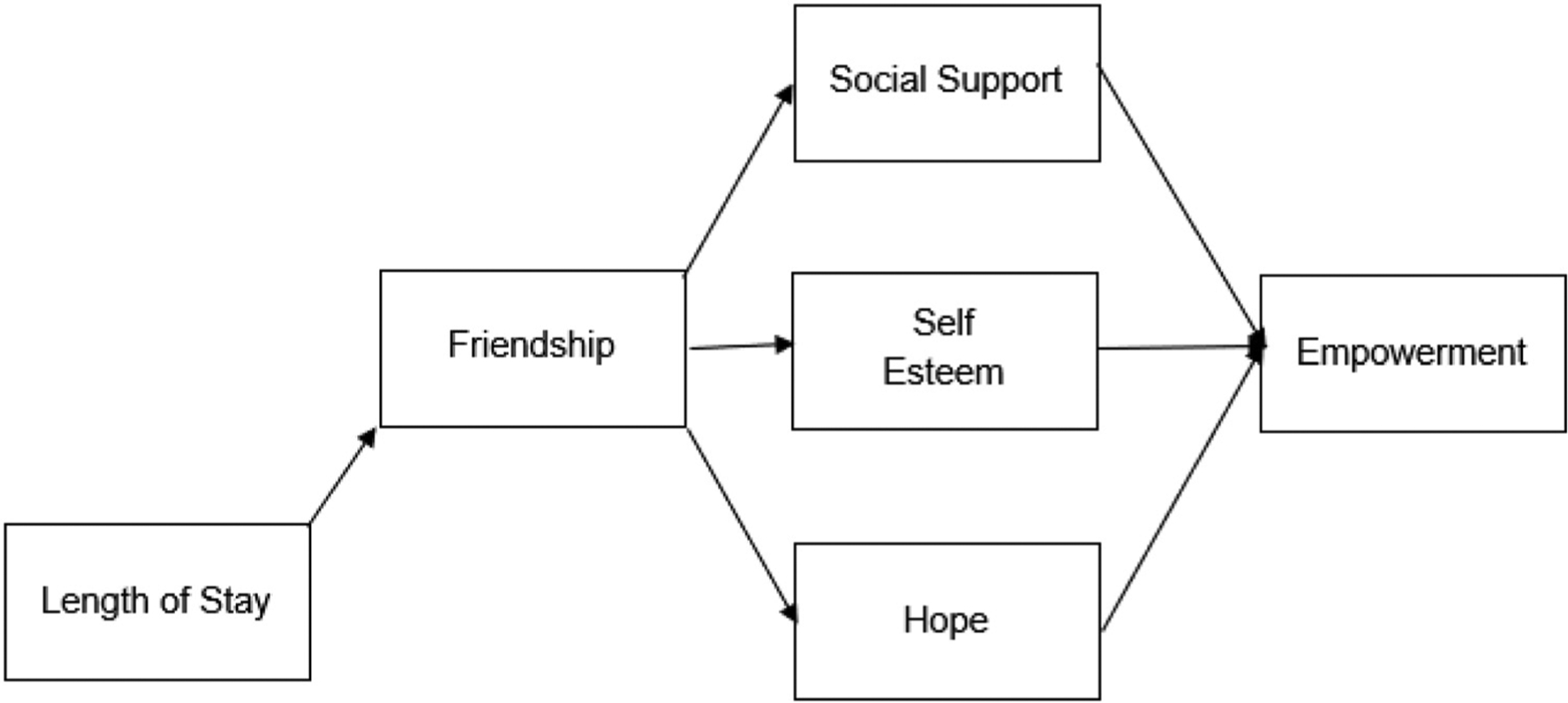

Examining empowering settings and mechanisms for treatment and recovery among women with substance use disorders merits particular attention. Women with substance use disorders face many social consequences related to their substance use, including strained relationships and limited access to social resources (Grella, 1999). Given the unique social needs among women in recovery (Covington, 2008; Marsh et al., 2000), it is critical to identify how same-gender sex friendships are related to empowerment for this population, especially when considering the importance of same-gender friendships for women’s well-being (Kroenke et al., 2006; Miething et al., 2016). The current study tested the model shown in Figure 1, which explored relations between friendships among women in recovery, individual resources (i.e., social support, self-esteem, hope), and empowerment (power and optimism). We hypothesized that longer durations of stay in a recovery-based group home would be related to more positive friendships with other women. Additionally, we hypothesize that individual resources would mediate the relations between women’s friendships and empowerment. This study involved former and current residents of Oxford House (OH; Oxford House, 2020). OHs are abstinence-based recovery homes for individuals with substance use disorders that are entirely peer-run with no professional or therapeutic staff. The OHs follow a democratic decision-making model with residents appointed to rotating leadership positions. Unlike most recovery homes, OHs have no limit on the length of residency as long as members pay their share for rent and utilities, remain abstinent from drug/alcohol use, and attend and comply with rules discussed at weekly house meetings. The OH model is centered on the philosophy that peer-to-peer support is one of the most important resources for one’s recovery, thus making this setting conducive to developing positive friendships. This community-based organization was selected as a recruitment site given its alignment with the characteristics of an empowering setting (Christens, 2012; Neal, 2014).

Figure 1.

Hypothesized Model

Note. Empowerment is measured as power and optimism.

Method

Procedure

Data for this study were collected at the Women’s Conference, Women Empowering Women, held during the 2017 annual Oxford House World Convention. Surveys were distributed to 244 women who filled out their packets individually within the same room. The participants were either currently living in an Oxford House or were alumni. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was granted by DePaul University.

Participants

Since OHs are separated by sex, women in this study are biologically female. A total of 244 women participated in this study with 73.7% (n = 179) identifying as European American, 12.8% (n = 31) African American, 4.9% (n = 12) multiracial, 4.5% (n = 11) other, and 4.1% (n = 10) Hispanic/Latinx. Ages ranged from 19 to 69 years with an average age of 37 years. A majority of women were current OH residents (82.1%), while only 17.5% of participants were OH alumni. The average length of stay in OH was 1.5 years and ranged from under one month to 14 years. Additionally, 77.4% were heterosexual, 14.3% were bisexual, 4.8% were homosexual, and 3.5% were other. Most women in the study had completed some college (43%), and most were employed full-time (68.8%). The years spent in active addiction ranged from 2 to 44 years, with a mean of 15.37 years. The time in sobriety ranged from under one month to 21 years, with a mean of 2.3 years.

Measures

Friendships With Women Scale (FWS)

The authors adapted the 7-item FWS for use in the current study from the 6-item general Friendship Scale (Hawthorne, 2006) to be exclusively about current relationships with all other women. For example, the item “It has been easy to relate to others” was changed to “It has been easy to relate to other women,” and “When with other people I felt separate from them” was changed to “When with other women I felt separate from them.” An extra item, “I felt competitive toward women around me,” was added to the FWS, which had no comparable item in the FWS. The second author, who is a woman in recovery, felt that this extra item was critical to understanding women’s friendships among our population. The items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all” to “almost always.” The FWS has been found to have excellent internal structures (CFI = .99, RMSEA = .02) and to be reliable with a Cronbach’s alpha of .83 (Hawthorne, 2006). The FWS had a comparable Cronbach’s alpha of .82.

Interpersonal Support Evaluation List-9 Item (ISEL-9)

ISEL-9 was adapted from the 12-item scale, which was truncated for this study due to a time limitation in data collection (Cohen et al., 1985). Items were also adapted to be specifically about relationships with other women and were rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “definitely false” to “definitely true.” Some items include “I feel there are no women I can share my most private worries and fears with” and “If I decide one afternoon that I would like to go to a movie that evening, I could easily find a woman to go with me.” The ISEL-9 is reliable with a Cronbach’s alpha at .88.

Rosenberg’s (1965) Self-Esteem Scale (RSES). RSES is a widely used 10-item, global self-esteem scale measured on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” Items include “I think I have a number of good qualities” and “I take a positive attitude toward myself.” The Cronbach’s alpha for our current sample is .88, which suggests strong internal consistency.

Hope Scale

The Hope Scale is a 9-item scale using an 8-point Likert scale ranging from “definitely false” to “definitely true.” This measure was adapted from the 6-point Snyder’s (1991) State Hope Scale to include the domain of “environmental context” (Stevens et al., 2014). The original two domains in Synder’s State Hope Scale are agency and pathways. Examples of items from the environmental context subscale include, “Right now I do not feel limited by the opportunities that are available,” and “I feel like I have plenty of good choices in planning my future.” Examples of items from the agency subscale include, “I can think of many ways to reach my current goals,” and “At this time, I am meeting the goals that I have set for myself.” Examples of items from the pathways subscale include, “If I should find myself in a jam, I could think of many ways to get out of it,” and “There are lots of ways around my problems that I am facing now.” The overall scale has a good internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of .86.

Adult Consumer Empowerment Scale (ACES)

The ACES is a 28-item scale measured using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” (Rogers et al., 1997). The scale was developed to measure empowerment among consumers of mental health services based on the consumer. The measure contains 5 domains: (1) self-esteem, (2) power/powerlessness, (3) community activism and autonomy, (4) optimism and control over the future, and (5) righteous anger. A confirmatory factor analysis of our sample has suggested this model is a good fit (CFI = .904, RSMEA = .047). Only the power and optimism subscales were used in the current analysis. Examples of items from the power/powerlessness subscale include, “I feel powerless most of the time,” and “Experts are in the best position to decide what people should do or learn.” Examples of items from the optimism subscale include, “I am generally optimistic about the future” and “Very often a problem can be solved by taking action.” The ACES has a strong internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of .86 (Rogers et al., 1997).

Analytic Approach

Path analysis was used to test the hypothesized mediational model (Baron & Kenny, 1986) using Mplus 8.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). Maximum likelihood estimation tested the conceptual model, in which friendships with women, individual resources (social support, self-esteem, and hope), and empowerment (power and optimism) were all observed variables. Indirect effects were tested using a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 replications with bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Significant indirect effects are indicated when the bias-corrected 95% confidence interval does not contain zero. Model fit indices were used to determine the overall goodness of fit for the data. The following model indices were used to assess model fit: Root M Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) values less than .08, the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) values greater than or equal to .95, and Comparative Fix Index (CFI) values greater than or equal to .90.

Results

Pearson’s bivariate correlations were conducted to assess the associations among the study variables (see Table 1). As hypothesized, length of stay was positively related to friendships with women (r = .29, p < .01). Friendships with women was significantly correlated with social support (r = .45, p < .01), self-esteem (r = .46, p < .01), and hope (r = .35, p < .01), with more positive friendships with women signifying higher levels of individual resources. Friendships with women was also significantly correlated with power (r = .22, p < .01) and optimism (r = .21, p < .01), with higher positive friendships being related to higher empowerment. Lastly, all three hypothesized mediators (e.g., social support, self-esteem, and hope) were positively correlated with power and optimism (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Bivariate Correlations of Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Length of stay | — | ||||||

| 2. Friendships | .29** | — | |||||

| 3. Social support | .25** | .45** | — | ||||

| 4. Hope | .07 | .35** | .48** | — | |||

| 5. Self-esteem | .23** | .46** | .37** | .60** | — | ||

| 6. Power | .13* | .22** | .29** | .20** | .32** | — | |

| 7. Optimism | .05 | .21** | .15* | .35** | .34** | .11 | — |

p < .05.

p < .01.

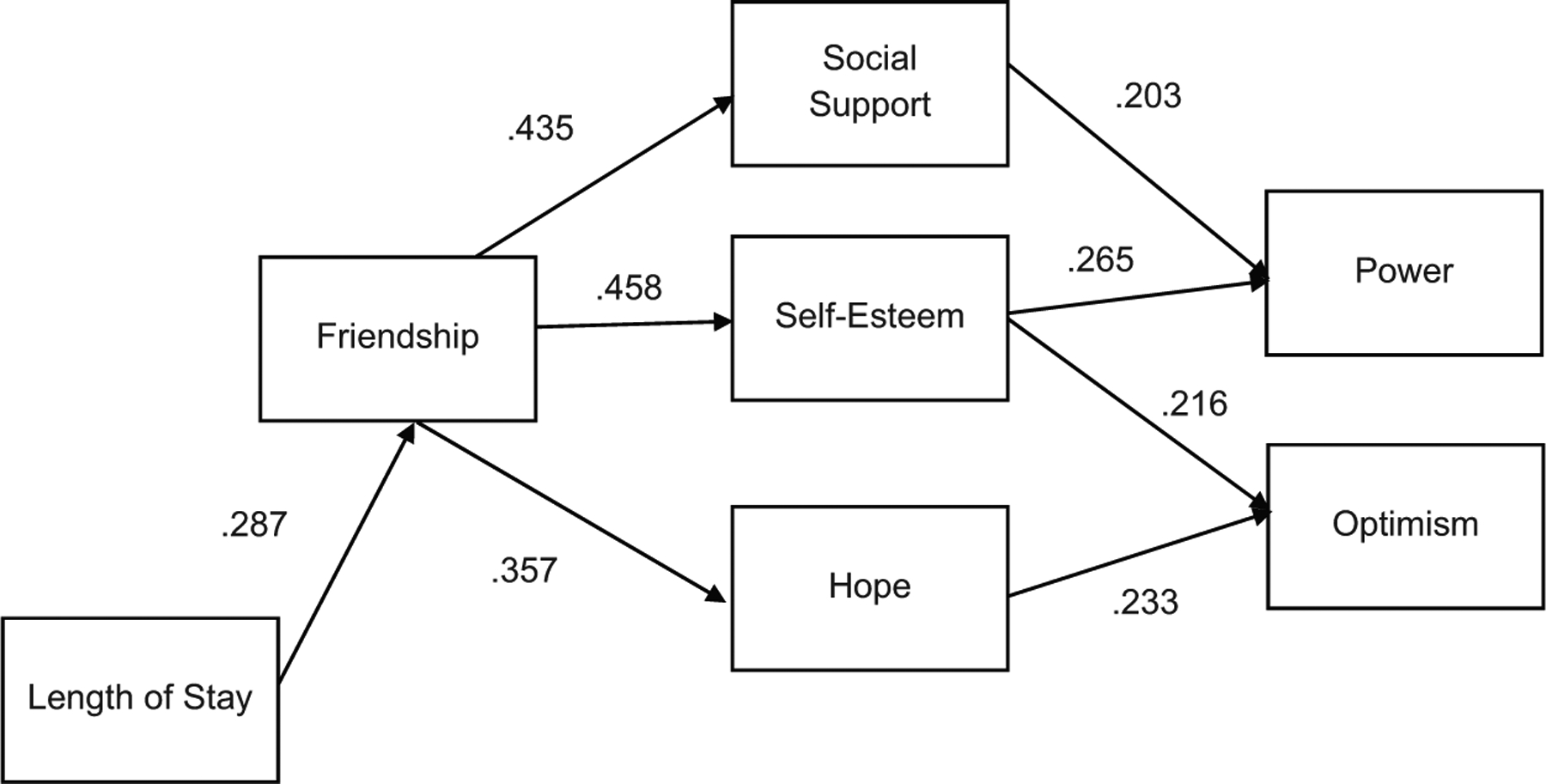

Table 2 provides the standardized parameter estimates and standard errors. Table 3 provides the parameter estimates of standardized indirect paths. The path analysis for Figure 2 indicated the chi-square value was χ2(7) = 13.629, p = .0582; and the overall model had an acceptable to excellent fit statistics (RMSEA = .063, CFI = .980, TLI = .939, SRMR = .031). This was a correlational model, with the absolute path coefficients varying from .216 to .458, and the effect sizes from small to moderate, with p values of .01 or less. Friendships among women had a significant and material relationship with women’s self-esteem, hopefulness, and social support. Friendship status was positively associated with empowerment constructs of power and optimism. Self-esteem was the only individual resource that was related to both power and optimism. Social support and self-esteem were related to power, whereas hope and self-esteem were related to optimism.

Table 2.

Standardized Direct Effects Model Results

| Direct paths | Estimate | SE | Est./SE | Two-Tailed P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friendship | ON | ||||

| Length of stay | 0.287 | 0.060 | 4.785 | .000* | |

| Self-esteem | ON | ||||

| Friendship | 0.458 | 0.052 | 8.819 | .000* | |

| Social support | ON | ||||

| Friendship | 0.435 | 0.053 | 8.200 | .000* | |

| Hope | ON | ||||

| Friendship | 0.357 | 0.057 | 6.208 | .000* | |

| Power | ON | ||||

| Self-esteem | 0.265 | 0.077 | 3.433 | .001* | |

| Social support | 0.203 | 0.069 | 2.941 | .003* | |

| Hope | −0.067 | 0.083 | −0.802 | .423 | |

| Optimism | ON | ||||

| Self-esteem | 0.216 | 0.076 | 2.853 | .004* | |

| Social support | −0.051 | 0.068 | −0.742 | .458 | |

| Hope | 0.233 | 0.080 | 2.919 | .004* |

Note. SE = standard error; Est. = estimate.

p < .05.

Table 3.

The Indirect Effect of Friendship on Empowerment Through Individual Resources

| BC 95% CI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect paths | Estimate | SE | Est./SE | Two-Tailed P-Value | Lower | Upper |

| Power | ||||||

| Self-esteem/friendship | 0.122 | 0.038 | 3.162 | .002* | 0.023 | 0.112 |

| Social support/friendship | 0.088 | 0.032 | 2.738 | .006* | 0.010 | 0.088 |

| Optimism | ||||||

| Self-esteem/friendship | 0.099 | 0.037 | 2.687 | .007* | 0.017 | 0.118 |

| Hope/friendship | 0.083 | 0.032 | 2.616 | .009* | 0.016 | 0.103 |

Note. SE = standard error; Est. = estimate; BC 95% CI = bias corrected 95% confidence interval.

p < .05.

Figure 2.

Relationships Between Friendship, Individual Resources, and Empowerment

Note. Standardized estimates are presented. All paths are significant at p < .05.

Analyses indicated a significant indirect effect of friendships on power via self-esteem (β = .12, p < .005) and social support (β = .08, p < .01). There was a significant indirect effect of friendships on optimism via self-esteem (β = .09, p < .01) and hope (β = .08, p < .01). There were no significant indirect effects between friendships and hope on power or between friendships and social support on optimism. Findings suggest that social support and self-esteem helped explain the positive role of friendships with women on power. Additionally, findings suggest that self-esteem and hope help explain the positive role of friendships with women on optimism.

Discussion

This study found that friendships between women are related to individual resources, meaning friendships may provide individuals with a specific perspective on themselves. Specifically, the stronger their friendships, the higher their self-esteem, hope, and social support. Moreover, friendships mediated by individual resources may increase women’s levels of perceived empowerment. These findings indicate that friendships have implications for how women view their future and the ability to control their future. This model provides support for the importance of a strong and positive community for women’s sustained well-being. Additionally, findings have implications for gender-specific treatment practices and recommendations impacting recovery outcomes. These findings suggest that supportive friendships are important resources in women’s lives that can help facilitate recovery from substance use disorders.

Our study found that a greater duration in a recovery-based facility, such as Oxford House (OH), was related to positive friendships with other women. Supportive and growth-oriented treatment and recovery settings where individuals can forge meaningful relationships with others might align well with what theorists refer to as empowering settings. Recovery homes and mutual-help programs might be examples of empowering settings that are conducive to the development of supportive friendships. In the OH context, the mixture of tenure among house members and the shared decision-making structure create a developmental scaffolding process for new members. Interpersonal relationships among members of different tenure in a setting have shown to increase trust, mutual obligation, information sharing, collective norms, and efficacy, and in turn, impact member’s commitment to passing on values to future members and foster the desire to help others (Russell et al., 2009). The existing structure within OHs functions to delegate control and decision-making, position others to take on new challenges, and bridge social divisions (e.g., race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation). The emphasis on interpersonal relationships, mentoring, and shared values of abstinence and recovery aim to empower house members to promote their well-being, overall functioning, and community integration.

Finally, models of mutual empowerment within community-based programs focus on transferring skills and knowledge from one setting to another, which is consistent with the OH model as it tends to be a transitional housing experience that bridges the gap between residential or inpatient detoxification and treatment to full integration into the community (Fedi et al., 2009). Additional research suggests the length of time spent in the treatment setting, abstinence self-efficacy, and social support predict cumulative abstinence for individuals (Jason et al., 2007), demonstrating the importance of these factors for recovery. These might be some of the reasons why the length of stay in a recovery home was related to greater positive relationships with other women.

Findings from our path analysis revealed that self-esteem was the only individual resource that mediated the relationship between friendships and empowerment constructs of power and optimism. This finding is consistent with the literature on friendships, self-esteem, and empowerment among women. Friendships appear to play a significant role in how women in recovery feel about themselves, and specifically, feedback from others is crucial to how one conceptualizes the self, their self-esteem, and self-worth (Voss et al., 1999). Others have hypothesized that self-esteem serves as a barometer of inclusion or exclusion within one’s social network (Voss et al., 1999). Indeed, theorists have consistently found that positive feedback from peers tends to increase positive self-assessments, whereas negative feedback results in less favorable self-assessments (Lundgren & Rudawsky, 1998). Our findings also align with the Self-in-Relation theory (Surrey, 1991) which conceptualizes connections that foster growth as the foundation of women’s development. In particular, this model posits that relational skills empower individuals, increase their self-worth, and promote a desire for further connection (Liang et al., 2002).

Self-esteem also has implications for the development and maintenance of optimism over time. The vulnerability model posits that low self-esteem is a risk factor for depressive symptoms as opposed to a depressive mood leading to low self-esteem (Steiger et al., 2015). The vulnerability model supports the findings of the current study, indicating the development of personal level resource self-esteem is related to increased optimism. A longitudinal study supporting the vulnerability model found that low self-esteem predicted greater depression at a later time point in both adolescents and young adults (Orth et al., 2008).

Social support was found to mediate the relationship between friendship and power, but not optimism. This finding suggests that greater social support is related to feelings of having greater control over one’s life and ability to make choices, but not to positive expectancies of future outcomes. This finding aligns with conceptualizations of women’s empowerment being developed and exercised through interpersonal relationships (Surrey, 1987). Social support obtained from friendships contributes to several psychological benefits such as companionship, emotional support, and relationship satisfaction (Sias & Bartoo, 2007; Taylor et al., 2000). Further, in the context of recovery from substance use disorder, social support and residential stability are key predictors of substance use recovery and treatment program completion (Dobkin et al., 2002; Longabaugh et al., 2010). Indeed, women living in a drug-free social environment are associated with higher abstinence rates (Ellis et al., 2004). Among both men and women, a longer duration spent in the OH setting was associated with decreased social support for alcohol and drug use (Davis & Jason, 2005). For only women, longer stays were related to an increased investment suggesting that duration in a treatment setting might be particularly important for women. Skaff et al. (1999) examined how stressors and friendships impacted men’s and women’s functioning with a drinking problem over time. Friendships were found to be particularly crucial for women. Specifically, an increase in friendship support predicted a decrease in depression and a decrease in days intoxicated among women.

Hope was found to mediate the relationship between friendship and optimism, with greater hope being related to greater optimism. Hope and optimism are positively related, but different constructs (Youssef & Luthans, 2007). Optimism differs from hope in that it is a general belief that one will have a positive future but distinctly lacks the components of personal action and environmental context. However, both hope and optimism are important for promoting and sustaining actions toward goal attainment. The current study suggests that hope derived from friendships can be particularly beneficial to women’s empowerment as it relates to higher positive expectancies about one’s future.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are several limitations to the present study. Data were cross-sectional, and causal inferences should not be inferred. Future studies should examine these types of constructs with longitudinal data to determine causality. Since self-esteem emerged as the sole mediator of both optimism and power, future longitudinal investigations into self-esteem’s mediating role are particularly warranted. Ideally, such data should be collected before women enter OH or other community settings and at various points during their stay to determine how such settings can influence these linkages. Prospective studies should also consider how same-gender friendships impact the severity of substance use and recovery outcomes over time for women.

A major limitation of this study was that it involved a convenience sample of women attending an Oxford House convention and may not be representative of women’s experiences in other recovery-based facilities. This recruitment method presents a sampling bias given that women who had negative experiences while in OH were less likely to attend the convention. Future studies can overcome this sampling bias by recruiting women who have had various recovery experiences (e.g., other types of recovery support settings and lack of recovery support) to determine whether friendships similarly influence their sense of empowerment via the individual resources examined in this study.

Additionally, while we collected information regarding participants’ sexual orientation, we did not collect information on participants’ gender identities. Rather, we included a statement in our informed consent that the study was open to women in recovery. Prospective studies should explore whether the processes explored in this paper are the same for transgender women. Lastly, our sample was primarily European American, warranting future studies on women of color, particularly given the racial and ethnic disparities in substance abuse treatment utilization and outcomes among women (Pinedo, 2019; Verissimo & Grella, 2017; Zemore et al., 2014).

Prospective studies can improve upon the measurement of friendships by using social network methods. There is a long tradition of research and theory on friendships to draw upon in the social network science literature (Boda et al., 2020; De la Haye et al., 2010; Moreno, 1934; Shin & Ryan, 2014). A social network approach recognizes the interdependencies between individuals and their social relationships and how these interdependencies affect behaviors, cognition, and attitudes (Smith & Christakis, 2008). A social network study on friendships among women can further elucidate the impact of these relationships on the development of empowerment.

Conclusion

Considering the importance of women’s interpersonal relationships, the current research examined the mechanisms through which friendships can lead to higher empowerment, specifically, to higher perceptions of power and optimism. Overall, findings revealed that positive friendships with other women are related to empowerment via individual resources (e.g., social support, self-esteem, and hope). There are several implications of the study’s findings. First, the results point to the importance of developing and sustaining empowering relationships for women in recovery. Findings also highlight the clear need to study settings that help foster these types of supportive friendships among women. Lastly, our findings have theoretical implications. The current findings align with feminist theory (Kabeer, 1999), which frames power as the ability to make choices and empowerment by utilizing resources to develop, act, and successfully achieve goals. Furthermore, our study corroborates other scholars’ conceptualization of empowerment as a relational process that is both built and exercised through positive relationships (Christens, 2012; Prilleltensky & Gonik, 1994; Surrey, 1987).

Public Significance Statement.

This study highlights the importance of developing and sustaining empowering relationships for women in recovery and identifying settings that help foster these supportive friendships. Findings can inform gender-specific treatment practices that are aimed at empowering women through their social connections to other women.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all the women who participated in this study and to the Oxford House organization. We thank Laura Sklansky for her invaluable feedback on earlier drafts. This publication was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Grant AA022763).

Biographies

Mayra Guerrero is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Research Consortium on Gender-based Violence at Michigan State University. She received her Ph.D. in Community Psychology from DePaul University. Her research examines the social and contextual factors that promote the well-being of marginalized populations. She specializes in working with individuals with substance use disorders, veterans, survivors of domestic violence, and individuals experiencing housing instability.

Casey Longan is a woman in long term recovery with a sobriety date of September 14, 2011. She graduated from San Antonio College during the pandemic with a bachelor’s degree in Criminal Justice and is currently a Training and Education Coordinator for Oxford House, Inc. She enjoys working with individuals who suffer from substance misuse so she can see them gain back their lives and become productive members of society.

Camilla Cummings is a doctoral candidate in the Clinical-Community Psychology PhD program at DePaul University in Chicago, IL. She is currently completing her pre-doctoral clinical internship at the Palo Alto Veterans Affairs Healthcare System in Palo Alto, CA. She conducts research, provides clinical services, and teaches undergraduate classes related to substance and alcohol use recovery and policy, PTSD and trauma-related disorders, and specializes in serving individuals who are unhoused.

Jessica Kassanits is a Research Study Coordinator in the department of Medical Social Sciences at Northwestern University. She is currently pursuing a Master of Public Health from DePaul University motivated by her experience working as a Research Project Assistant at the Center for Community Research at DePaul University.

Angela Reilly is an attorney at Edelson PC and a graduate of The University of Chicago Law School. Her legal career was inspired by the time she spent working at DePaul University’s Center for Community Research as a Research Project Coordinator, where she contributed to the present publication.

Ed Stevens was a researcher at the Center for Community Research, DePaul University, and is currently retired.

Leonard A. Jason is currently a Professor of Psychology at DePaul University and the Director of the Center for Community Research. Jason is a former president of the Division of Community Psychology of the American Psychological Association. Jason has edited or written 30 books, and he has published over 900 articles and 100 book chapters. He has served on the editorial boards of ten psychological journals. Jason has served on review committees of the National Institutes of Health, and he has received over $46,500,000 in federal research grants.

References

- Allan G (1979). A sociology of friendship and kinship. Allen & Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Azzi-Lessing L, & Olsen LJ (1996). Substance abuse-affected families in the child welfare system: New challenges, new alliances. Social Work, 41(1), 15–23. 10.1093/sw/41.1.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bank BJ, & Hansford SL (2000). Gender and friendship: Why are men’s best same-sex friendships less intimate and supportive? Personal Relationships, 7(1), 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, & Kenny DA (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billings AG, & Moos RH (1984). Coping, stress, and social resources among adults with uni-polar depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(4), 877–891. 10.1037/0022-3514.46.4.877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boda Z, Elmer T, Vörös A, & Stadtfeld C (2020). Short-term and long-term effects of a social network intervention on friendships among university students. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 2889. 10.1038/s41598-020-59594-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cable N, Bartley M, Chandola T, & Sacker A (2013). Friends are equally important to men and women, but family matters more for men’s well-being. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 67(2), 166–171. 10.1136/jech-2012-201113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell CR, & Martinko MJ (1998). An integrative attributional perspective of empowerment and learned helplessness: A multimethod field study. Journal of Management, 24(2), 173–200. 10.1177/014920639802400203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo LB, & Chapman AR (2010). The process of empowerment: A model for use in research and practice. American Psychologist, 65(7), 646–659. 10.1037/a0018854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christens BD (2012). Toward relational empowerment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 50(1–2), 114–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, & McKay G (1984). Handbook of psychology and health: vol. 4. Social support, stress and the buffering hypothesis: A theoretical analysis (pp. 253–267). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarck T, & Hoberman H (1985). Measuring the functional components of social support. In Sarason IG & Sarason BR (Eds.), Social Support: Theory, research and application (pp. 73–94). Martinus Nijhoff. 10.1007/978-94-009-5115-0_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Covington S (2007). The relational theory of women’s psychological development: implications for the criminal justice system. In Zaplin R (Ed.), Female offenders: clinical perspectives and effective interventions (2nd ed.). Jones & Bartlett. [Google Scholar]

- Covington SS (2008). Women and addiction: A trauma-informed approach. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 40(Suppl. 5), 377–385. 10.1080/02791072.2008.10400665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241. 10.2307/1229039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MI, & Jason LA (2005). Sex differences in social support and self-efficacy within a recovery community. American Journal of Community Psychology, 36(3–4), 259–274. 10.1007/s10464-005-8625-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Haye K, Robins G, Mohr P, & Wilson C (2010). Obesity-related behaviors in adolescent friendship networks. Social Networks, 32(3), 161–167. 10.1016/j.socnet.2009.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, & Diener M (2009). Cross-cultural correlates of life satisfaction and self-esteem. In Diener E (Ed.), Culture and Well-Being (pp. 71–91). Springer. 10.1007/978-90-481-2352-0_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dobkin PL, De CM, Paraherakis A, & Gill K (2002). The role of functional social support in treatment retention and outcomes among outpatient adult substance abusers. Addiction, 97(3), 347–356. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00083.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis B, Bernichon T, Yu P, Roberts T, & Herrell JM (2004). Effect of social support on substance abuse relapse in a residential treatment setting for women. Evaluation and Program Planning, 27(2), 213–221. 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2004.01.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fedi A, Mannarini T, & Maton KI (2009). Empowering community settings and community mobilization. Community Development (Columbus, OH), 40(3), 275–291. 10.1080/15575330903109985 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrer R, & Stansfeld SA (2002). How gender affects patterns of social relations and their impact on health: A comparison of one or multiple sources of support from “close persons”. Social Science & Medicine, 54(5), 811–825. 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00111-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, & Schwartz MD (2008). Stress, coping, and health behavior. In Glanz K, Rimer B, & Viswanath K (Eds.), Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice (4th ed., 211–236). Jossey-Bass. https://iums.ac.ir/files/hshe-soh/files/beeduhe_0787996149.pdf#page=249 [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield SF, Brooks AJ, Gordon SM, Green CA, Kropp F, McHugh RK, Lincoln M, Hien D, & Miele GM (2007). Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: A review of the literature. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 86(1), 1–21. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE (1999). Women in residential drug treatment: Differences by program type and pregnancy. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 10(2), 216–229. 10.1353/hpu.2010.0174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawthorne G (2006). Measuring social isolation in older adults: Development and initial validation of the friendship scale. Social Indicators Research, 77(3), 521–548. 10.1007/s11205-005-7746-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Davis MI, & Ferrari JR (2007). The need for substance abuse after-care: Longitudinal analysis of Oxford House. Addictive Behaviors, 32(4), 803–818. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer N (1999). Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Development and Change, 30(3), 435–464. 10.1111/1467-7660.00125 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan A (1986). The “self-in-relation”: Implications for depression in women. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, & Practice, 23(2), 234–242. 10.1037/h0085603 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke CH, Kubzansky LD, Schernhammer ES, Holmes MD, & Kawachi I (2006). Social networks, social support, and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 24(7), 1105–1111. 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.2846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger E, Deal E, Lopez AA, Dressel AE, Graf MDC, Schmitt M, Hawkins M, Pittman B, Kako P, & Mkandawire-Valhmu L (2022). Successful substance use disorder recovery in transitional housing: Perspectives from African American women. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. Advance online publication. 10.1037/pha0000527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang B, Tracy A, Taylor CA, Williams LM, Jordan JV, & Miller JB (2002). The relational health indices: A study of women’s relationships. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 26(1), 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Wirtz PW, Zywiak WH, & O’Malley SS (2010). Network support as a prognostic indicator of drinking outcomes: The COMBINE Study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 71(6), 837–846. 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren DC, & Rudawsky DJ (1998). Female and male college students’ responses to negative feedback from parents and peers. Sex Roles, 39(5–6), 409–429. 10.1023/A:1018823126219 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh JC, D’Aunno TA, & Smith BD (2000). Increasing access and providing social services to improve drug abuse treatment for women with children. Addiction, 95(8), 1237–1247. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.958123710.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, Votaw VR, Sugarman DE, & Greenfield SF (2018, December). Sex and gender differences in substance use disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 66, 12–23. 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miething A, Almquist YB, Östberg V, Rostila M, Edling C, & Rydgren J (2016). Friendship networks and psychological well-being from late adolescence to young adulthood: A gender-specific structural equation modeling approach. BMC Psychology, 4(1), 34. 10.1186/s40359-016-0143-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JB (1976). Toward a new psychology of women. Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno J (1934). Who shall survive? Nervous and Mental Disease Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén B (2017). Mplus user’s guide: Statistical analysis with latent variables, user’s guide.

- Neal JW (2014). Exploring empowerment in settings: Mapping distributions of network power. American Journal of Community Psychology, 53(3–4), 394–406. 10.1007/s10464-013-9609-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth U, Robins RW, & Roberts BW (2008). Low self-esteem prospectively predicts depression in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(3), 695–708. 10.1037/0022-3514.95.3.695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxford House. (2020). Oxford House, Inc. Annual Report FY2020. Oxford House, Inc. https://www.oxfordhouse.org/userfiles/file/doc/ar2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Parker PD, Ciarrochi J, Heaven P, Marshall S, Sahdra B, & Kiuru N (2015). Hope, friends, and subjective well-being: A social network approach to peer group contextual effects. Child Development, 86(2), 642–650. 10.1111/cdev.12308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinedo M (2019). A current re-examination of racial/ethnic disparities in the use of substance abuse treatment: Do disparities persist? Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 202, 162–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, & Hayes AF (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prilleltensky I, & Gonick LS (1994). The discourse of oppression in the social sciences: Past, present, and future. The Jossey-Bass social and behavioral science series. Human diversity: Perspectives on people in context (145–177). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Reis HT, Senchak M, & Solomon B (1985). Sex differences in the intimacy of social interaction: Further examination of potential explanations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(5), 1204–1217. 10.1037/0022-3514.48.5.1204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers ES, Chamberlin J, Ellison ML, & Crean T (1997). A consumer-constructed scale to measure empowerment among users of mental health services. Psychiatric Services, 48(8), 1042–1047. 10.1176/ps.48.8.1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, & Rudolph KD (2006). A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin, 132(1), 98–131. 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press. 10.1515/9781400876136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Muraco A, Subramaniam A, & Laub C (2009). Youth empowerment and high school Gay-Straight Alliances. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(7), 891–903. 10.1007/s10964-008-9382-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster TL, Kessler RC, & Aseltine RH Jr. (1990). Supportive interactions, negative interactions, and depressed mood. American Journal of Community Psychology, 18(3), 423–438. 10.1007/BF00938116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin H, & Ryan AM (2014). Early adolescent friendships and academic adjustment: Examining selection and influence processes with longitudinal social network analysis. Developmental Psychology, 50(11), 2462–2472. 10.1037/a0037922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sias PM, & Bartoo H (2007). Friendship, social support, and health. In Low-cost approaches to promote physical and mental health (pp. 455–472). Springer. 10.1007/0-387-36899-X_23 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skaff MM, Finney JW, & Moos RH (1999). Gender differences in problem drinking and depression: Different “vulnerabilities?”. American Journal of Community Psychology, 27(1), 25–54. 10.1023/A:1022813727823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KP, & Christakis NA (2008). Social networks and health. Annual Review of Sociology, 34(1), 405–429. 10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134601 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR, Harris C, Anderson JR, Holleran SA, Irving LM, Sigmon ST, Yoshinobu L, Gibb J, Langelle C, & Harney P (1991). The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(4), 570–585. 10.1037/0022-3514.60.4.570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger AE, Fend HA, & Allemand M (2015). Testing the vulnerability and scar models of self-esteem and depressive symptoms from adolescence to middle adulthood and across generations. Developmental Psychology, 51(2), 236–247. 10.1037/a0038478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens EB, Buchannan B, Ferrari JR, Jason LA, & Ram D (2014). An investigation of hope and context. Journal of Community Psychology, 42(8), 937–946. 10.1002/jcop.21663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2019). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP19-5068, NSDUH Series H-54). Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/ [Google Scholar]

- Surrey JL (1987). Relationship and empowerment (p. 163). Stone Center for Developmental Services and Studies, Wellesley College. [Google Scholar]

- Surrey JL (1991). Self in relation: A theory of women’s development. In Jordan J, Kaplan A, Miller JB, Stiver I & Surrey J (Eds.), Women’s growth in connection (51–66). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tafarodi RW, & Milne AB (2002). Decomposing global self-esteem. Journal of Personality, 70(4), 443–483. 10.1111/1467-6494.05017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Klein LC, Lewis BP, Gruenewald TL, Gurung RA, & Updegraff JA (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review, 107(3), 411–429. 10.1037/0033-295X.107.3.411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verissimo ADO, & Grella CE (2017). Influence of gender and race/ethnicity on perceived barriers to help-seeking for alcohol or drug problems. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 75, 54–61. 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss K, Markiewicz D, & Doyle AB (1999). Friendship, marriage and self-esteem. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 16(1), 103–122. 10.1177/0265407599161006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wood W, & Eagly AH (2015). Two traditions of research on gender identity. Sex Roles, 73(11), 461–473. 10.1007/s11199-015-0480-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Youssef CM, & Luthans F (2007). Positive organizational behavior in the workplace: The impact of hope, optimism, and resilience. Journal of Management, 33(5), 774–800. 10.1177/0149206307305562 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zemore SE, Murphy RD, Mulia N, Gilbert PA, Martinez P, Bond J, & Polcin DL (2014). A moderating role for gender in racial/ethnic disparities in alcohol services utilization: Results from the 2000 to 2010 national alcohol surveys. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 38(8), 2286–2296. 10.1111/acer.12500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]