Abstract

Bacteria assemble complex structures by targeting proteins to specific subcellular locations. The protein coat that encases Bacillus subtilis spores is an example of a structure that requires coordinated targeting and assembly of more than 24 polypeptides. The earliest stages of coat assembly require the action of three morphogenetic proteins: SpoIVA, CotE, and SpoVID. In the first steps, a basement layer of SpoIVA forms around the surface of the forespore, guiding the subsequent positioning of a ring of CotE protein about 75 nm from the forespore surface. SpoVID localizes near the forespore membrane where it functions to maintain the integrity of the CotE ring and to anchor the nascent coat to the underlying spore structures. However, it is not known which spore coat proteins interact directly with SpoVID. In this study we examined the interaction between SpoVID and another spore coat protein, SafA, in vivo using the yeast two-hybrid system and in vitro. We found evidence that SpoVID and SafA directly interact and that SafA interacts with itself. Immunofluorescence microscopy showed that SafA localized around the forespore early during coat assembly and that this localization of SafA was dependent on SpoVID. Moreover, targeting of SafA to the forespore was also dependent on SpoIVA, as was targeting of SpoVID to the forespore. We suggest that the localization of SafA to the spore coat requires direct interaction with SpoVID.

Proteins are targeted to specific subcellular locations during the assembly of a variety of bacterial structures. The structures assembled by prokaryotes include, for example, the cell division septum (3), surface protein layers (S-layers) (36), and a number of surface appendages such as flagella (24) and pili (17). Here we are concerned with the assembly of the Bacillus subtilis spore coat, a proteinaceous structure that encases spores (reviewed in references 7 and 16). The B. subtilis spore is a metabolically dormant cell type that is formed as an adaptive response to nutrient depletion (9, 30, 37). The spore coat provides protection against physical and chemical insults and can sense and respond to nutrients that trigger germination (9, 26).

Spore morphogenesis commences by the placement of an asymmetric septum that divides the rod-shaped cell into a larger mother cell and a smaller prespore, each containing a copy of the chromosome. The septal membranes migrate around the prespore, in a process known as engulfment, which eventually results in the formation of a free-floating protoplast (the forespore) separated from the mother cell cytoplasm by a double-membrane system. Cell wall material (the cortex) is deposited between the membranes of the forespore (9, 30, 37). A thick coat composed of more than two dozen proteins is assembled around the outer forespore membrane. The majority of the proteins that make up the coat are synthesized in the mother cell under the direction of mother cell-specific RNA polymerase sigma factors (7, 16, 30).

In thin-section electron micrographs, the coat appears as a multilayer structure with an electron-dense outer coat, a lamellar inner coat, and a diffuse gray undercoat (reviewed in references 7 and 16). In the earliest stages of coat assembly, a protein called SpoIVA forms a spherical shell close to the outer surface of the forespore (8, 13, 31, 32). Although the details of SpoIVA targeting are not known, SpoVM is at least partially required for SpoIVA localization (5, 21). In the next steps, CotE organizes into a ring, about 75 nm from the outer forespore membrane (8). Maintenance of the CotE ring requires SpoVID (8). Immunogold localization with a HA1 epitope-tagged version of SpoVID shows that the protein is localized near the forespore outer membrane, but it is not known what proteins interact with SpoVID at this location (8). SafA (29), also known as YrbA (38, 39), is a candidate for a protein that interacts with SpoVID. SafA is found at the interface between the coat and cortex in mature spores (29). SafA and SpoVID accumulate during the early stages of coat assembly, and during this stage, antibodies to either protein coimmunoprecipitate both SafA and SpoVID (29). Therefore, SafA and SpoVID may be associated in a complex during the early phases of coat assembly.

In this study we tested the hypothesis that SafA and SpoVID interact. Yeast two-hybrid and in vitro binding experiments showed that SpoVID interacts with SafA and SafA interacts with itself. We used immunofluorescence microscopy to examine the localization of SafA and SpoVID during sporulation in the wild-type and various mutant strains. We found that SafA is targeted to the forespore and that localization of SafA to the forespore required SpoIVA and SpoVID, but not CotE. We also found that targeting of SpoVID to the forespore was dependent on SpoIVA, but not SafA or CotE.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and general techniques.

The B. subtilis strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. The Escherichia coli strain DH5α (laboratory stock) was used for cloning, transformation, and amplification of all plasmid constructs. E. coli strain BL21 was used for the overproduction of the glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins (laboratory stock). E. coli strain BL21(DE3)/pLysS (Novagen) was used for the production of an His6x-S.Tag-SafA fusion protein (see below). Luria-Bertani medium was routinely used for growth and maintenance of E. coli and B. subtilis strains, with appropriate antibiotic selection when needed (14, 15). Nutrient exhaustion was used to induce sporulation in liquid culture or on plates of Difco sporulation medium (DSM) (27).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or propertiesa | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| B. subtilis strains | ||

| MB24 | Wild-type trpC2 metC3 Spo+ | Laboratory stock |

| AH131 | trpC2 metC3 amyE::Emr | Laboratory stock |

| AOB90 | trpC2 metC3 MB24ΩpOZ139 | This work |

| AOB68 | trpC2 metC3 ΔsafA::Spr | 29 |

| AOB24 | trpC2 metC3 ΔspoVID::Kmr | 29 |

| AH64 | trpC2 metC3 ΔcotE::Cmr | 29 |

| AH72 | trpC2 metC3 spoIVA178 | Laboratory stock |

| AOB125 | trpC2 metC3 amyE::pOZ168 | This work |

| AOB232 | trpC2 metC3 MB24ΩpOZ500 | This work |

| E. coli BL21 GST fusion protein-overproducing strains | ||

| AOE214 | Contains pOZ169 | This work |

| AOE215 | Contains pOZ171 | This work |

| AOE216 | Contains pOZ170 | This work |

| AOE235 | Contains pGex4T-3 | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR2.1TOPO | TA cloning vector | Invitrogen |

| pGex4T-3 | GST fusion protein expression vector | Pharmacia |

| pOZ139 | safA-FLAG in pCR2.1TOPO, Cmr | This work |

| pOZ115 | safA (with promoter region) in pCR2.1TOPO | This work |

| pOZ168 | safA::lacZ in pAC5 | This work |

| pOZ169 | spoVID in pGex4T-3 | This work |

| pOZ170 | safA-C30 in pGex4T-3 | This work |

| pOZ171 | safA in pGex4T-3 | This work |

| pOZ500 | pOZ139 with TTT-to-TGA mutation (at codon 155) | This work |

The omega symbol Ω denotes that the plasmid was integrated into the B. subtilis chromosome by a Campbell integration event (single crossover in the region of homology).

Preparation of B. subtilis whole-cell extracts and immunoblotting.

For immunoblotting, samples (10 ml for French pressure cell, 1 ml for lysozyme lysis) of DSM cultures of various strains were collected at intervals after the onset of sporulation. French press lysates were prepared by the method of Seyler et al. (35). Whole-cell lysates were prepared by gentle lysozyme lysis by the method of Kodama et al. (19). For the GST pull-down assays (see below), 50-ml samples of B. subtilis strain AOB90 were taken 3 and 4 h after the onset of sporulation and lysed with the French press (18,000 lb/in2) in 5 ml of breaking buffer (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS], 0.1% Tween 20, 10% glycerol) with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The cell debris was removed by centrifugation. Proteins were resolved on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–12% polyacrylamide gels, and immunoblotting was performed as previously described (29) with an anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody at a 1:30,000 dilution of the stock solution (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.).

Yeast two-hybrid system.

The Matchmaker Two-hybrid system (Clontech) was used as described by Seyler et al. (35) with only minor modifications and with the following plasmid constructs. The spoVID coding sequence was obtained by PCR using primers VID1-d and VID1-R, and the safA coding sequence was amplified by primers saf+41d and saf+1234R (Table 2). The N-terminal region (residues 1 to 163) and the C-terminal region (residues 164 to 387) of SafA were amplified separately using primers saf+41d and saf163R and saf164d and saf+1234R, respectively (Table 2). The spoVID and safA PCR products were digested by NcoI and BglII and cloned into the NcoI and BamHI sites of both pAS2-1 and pACT-2 (Table 2) to create the plasmids represented in Table 1. S. cerevisiae strains Y187 (MATα ura3-52 his3-200 ade2-101 trp1-901 leu2-3,112 gal4Δ met− gal80Δ URA3::GAL1UAS-GAL1TATA-HIS3) and Y190 (MATa ura3-52 his3-200 ade2-101 lys2-801 trp1-901 leu2-3,112 gal4Δ gal80Δ cyhr2 LYS2::URA::GAL1UAS-HIS3TATA-HIS3 URA3::GAL1UAS-GAL1TATA-HIS3) (Clontech) were transformed independently with the pAS2-1 and pACT-2 vectors and/or constructs, respectively, according to the protocols suggested by the manufacturer. The resulting clones were used to do pairwise matings, selecting for Leu and Trp. Colony lift assays for detecting β-galactosidase activity were performed essentially as described by the manufacturer (Clontech).

TABLE 2.

Primers used for cloning and site-directed mutagenesis

| Primer | Sequence (5′→3′)a |

|---|---|

| saf+41d | TAGGAGGGGAAAACCATGGAAATCCATATCG |

| FLAG-R | TCATCATTTGTCATCGTCATCTTTATAATCCTCATTTTCTTCTTCCGGACGGCCAAACATTTGGTTTACAGAAGGC |

| saf+1234R | CGTTCCGAAAGATCTCTCATTTTCTTCTTCCGG |

| saf-554d | GATGAATTAGTAGCTGAATCCGGGC |

| saf155stop-d | CATATGTATCATATGCAAGACCAATGACCACAACAGGAG |

| saf155stop-R | CCATATTACTCATAGCCTCCTGTTGTGGTCATTGGTCTT |

| saf-121d | GCCAAAAGCCATTCAGGAGGATCCACTCCTTGCCC |

| pAC5R1 | ACGTTGTAAAACGACGGGATCCGCATTTTCCATATTACTA |

| VID1-d | ATGAAAGGAGGCCATGGACTTGCCGCAAAA |

| VID1-R | CATTTTCGGATCCCTTACGGTTTACGC |

| saf164d | AGTTATAGTAGGATCCCCATGGAAAATGCAAATTATCC |

| saf163R | GCATATGATACATAAGATCTATATTTCCGTC |

| safFL-d | CTGGTTCCGCGTGGATCCTTGAAAATCCATATCG |

| safC-d | CTGGTTCCGCGTGGATCCTTGCCGCAAAATCATCG |

| safGST-R | ATGCGGCCGCTCGAGTCACTCATTTTCTTCTTCC |

| VID2-d | CTGGTTCCGCGTGGATCCTTGCCGCAAAATCATCG |

| VID2-R | ATGCGGCCGCTCGAGTTACGCATGGCTATTTTTATATTGAGG |

Restriction enzyme sites are underlined.

Pull-down assays with GST fusion proteins and B. subtilis lysates containing a FLAG-tagged version of SafA.

Primer pairs VID2-d and VID2-R, safFL-d and safGST-R, and safC-d and safGST-R (Table 2) were used to PCR amplify the coding regions of spoVID, safA-C30, and safA-FL, respectively. The resulting PCR products were digested with BamHI and XhoI and cloned into the corresponding sites in pGex4T-3 (Amersham/Pharmacia) to create in-frame N-terminal GST fusion protein constructs pOZ169, pOZ170, and pOZ171 (Table 1). These three plasmids and the GST construct alone (pGex4T-3) were transformed into E. coli expression strain BL21 (Amersham/Pharmacia) to create strains AOE214, AOE216, AOE215, and AOE235, respectively. These E. coli expression strains were grown to mid-log phase (0.4 optical density at 600 nm), induced with 2 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), and grown for 3 h before harvesting the cells. The cell pellets were resuspended in 1-ml portions of VPEX-100 buffer (100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10% glycerol) per 50 ml of induced culture and lysed in a French pressure cell (18,000 lb/in2). The lysate was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm (SS-34 rotor) for 30 min to remove cell debris. One milliliter of cleared lysate was bound to 50 μl of a 50% slurry of glutathione Sepharose beads (Amersham/Pharmacia) in an Eppendorf tube on a rotating tube holder at 4°C. The beads were washed three times in VPEX-200 (same as VPEX-100 but with 200 mM NaCl) and then three times in PBS–0.1% Tween 20.

For the interaction assay, 1-ml portions of soluble extracts prepared from samples of cultures of B. subtilis AOB90 taken 3 or 4 h after the onset of sporulation (described above) were incubated for 30 min at 4°C on a rotator with the prepared GST fusion proteins bound to the glutathione Sepharose beads or to glutathione Sepharose beads alone. The mixtures were washed three times with PBS–0.1% Tween 20 and resuspended in a final volume of 50 μl. The samples were boiled for 2 min in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) Laemmli loading buffer (Bio-Rad) and subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting, with an anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody at a 1:30,000 dilution of the stock solution (Sigma).

Pull-down assays with purified SpoVID-GST and His-tagged SafA.

The in vitro pull-down assay was performed as described above, except that purified SafA was used in place of the B. subtilis AOB90 bacterial lysate. We used an N-terminal histidine-tagged version of SafA. Cloning, overexpression, and purification of His6x-SafA were performed by the methods described by Ozin et al. (29) with the following modifications. The solubilized protein was purified on a small scale using a nitrilotriacetic acid magnetic resin (Qiagen) following the manufacturer's protocol and eluting the protein with 500 mM imidazole.

Construction of strains carrying a wild-type (or stop codon mutant) C-terminal FLAG-tagged version of safA.

Primers saf+41d and FLAG-R, which encodes the amino acid sequence (DYKDDDDK) for a FLAG tag (Table 2), were used to amplify the safA coding region excluding the C-terminal stop codon. The resulting 1,223-bp PCR product, C-terminal FLAG tag fused in frame with safA, was cloned into the PCR2.1TOPO vector (Invitrogen) to form pOZ130. A chloramphenicol resistance cassette, extracted from pMS38 (M. Serrano and A. O. Henriques, unpublished vector) by a restriction digest with BglII and BamHI, was ligated into the BamHI site of pOZ130 to form pOZ139. Plasmid pOZ139 served as a template for site-directed mutagenesis. A nonsense mutation at codon 155 was made following the manufacturer's protocol for the Quick Change system (Stratagene) using primer sets saf155stop-d and saf155stop-R (Table 2). The mutations in the resulting plasmid pOZ500 were confirmed by sequencing. Competent cells of MB24 were transformed with pOZ139 or pOZ500, with selection for chloramphenicol resistance. Transformants were expected to arise as a result of a single reciprocal crossover (Campbell-type) event, which would contain two copies of safA, a functional upstream copy of the wild type (strain AOB90) or stop codon mutant (AOB232) with the C-terminal FLAG tag, and a promoterless downstream wild-type copy. The arrangement of the safA locus was confirmed by PCR analysis of the AOB90 and AOB232 recombinant chromosomes.

Construction of a strain carrying a safA::lacZ translational fusion ectopically inserted at the amyE locus.

The safA gene, including 554 bp upstream from its start point of transcription, was amplified by PCR generated from primers saf-554d and saf+1234R (Table 2). This 1,788-bp DNA fragment was cloned into the TA-TOPO cloning system 2.1 (Invitrogen) to produce pOZ115. Primers saf-121d and saf-pAC5R1 (Table 2) were used to PCR amplify the safA promoter region (39) up to codon 167 from pOZ115. The resulting 663-bp PCR product, flanked by engineered BamHI sites, was cloned into the BamHI site of pAC5 (25) to create a safA::lacZ translational fusion plasmid, pOZ168. The PCR insert was confirmed to be oriented in the same direction as lacZ by PCR and restriction digest analyses.

Competent cells of B. subtilis AH131 were transformed with ScaI-digested pOZ168 with selection for chloramphenicol resistance and screened for erythromycin sensitivity. The resulting clone AOB125 was shown by PCR analysis to result from an allele replacement (double crossover event) of the erythromycin resistance cassette at the amyE locus (AH131).

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

The general immunofluorescence microscopy protocols of Harry et al. (13) and Pogliano (31) were used with the following modifications. A commercial fixative, Histochoice (Amresco), was used for cell fixation before permeabilization by lysozyme. Immunolabeling was carried out with antiserum concentrations of 1:1,000 of anti-SafA and anti-SpoVID (29) and 1:10,000 anti-FLAG (Sigma). Alexa 488 secondary antibody conjugates were used in place of fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibodies, nucleic acids were labeled with 1:1,000 dilution of a 10-mg/ml stock of 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and samples were mounted in Pro-Fade medium (Molecular Probes). We used an Olympus BX60 epifluorescence microscope equipped with a Quantix Digital camera (Photometrics). All samples were observed with a 100× objective lens and standard filters for fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and DAPI viewing. Images were processed with Adobe Photoshop 4.0.

RESULTS

Interaction of SafA with itself and with SpoVID in an S. cerevisiae two-hybrid system.

In this investigation we were interested in determining whether SafA and SpoVID form complexes through direct interaction. We tested for interaction between SpoVID and SafA using the yeast two-hybrid system (10–12). We fused the coding sequences of spoVID or safA independently to either the activation domain (AD) or the DNA-binding domain (BD) of the yeast transcriptional activator GAL4 and introduced these sequences into yeast reporter strains Y187 and Y190. We also fused the C-terminal region of safA (SafA-C30; residues 164 to 387) and the N-terminal region (SafA-N; residues 1 to 163) of safA to either the AD or the BD of the yeast transcriptional activator GAL4 because multiple forms of SafA are found in the spore coat (28, 29, 38, 39). N-terminal amino acid sequencing of proteins isolated from mature spores showed that the 45-kDa form is full-length SafA (SafA-FL), whereas the 30-kDa form (SafA-C30) represents the C-terminal amino acids of SafA beginning at codon 164 (38, 39). Interaction of the fusion proteins in the yeast strains results in expression of a lacZ reporter gene (35). As shown in Table 3, there was no β-galactosidase activity detected when individual fusion proteins were expressed with the vector control. In contrast, positive interactions were produced between SpoVID and SafA and between full-length SafA (SafA-FL) and itself. No interactions were detected between the SafA-N and SafA-C30 constructs. When fused to the BD, SafA-C30 interacted with SpoVID, SafA-FL, and itself, but when fused to the AD, SafA-C30 interacted only with itself. It is not uncommon that interactions between GAL4 fusion proteins can be detected in only one of the two contexts, AD or BD (35). We did not find evidence for an interaction of SpoVID with itself, using the yeast two-hybrid assay (Table 3). Our results strongly suggest that SpoVID directly interacts with SafA, that the N-terminal region of SafA can interact with itself, and that the C-terminal region of SafA can interact with itself.

TABLE 3.

Detection of lacZ transcription by colony lift assays in diploid yeast strains Y187 and Y190a

| Plasmid with activation domain fusionb | Detection of lacZ transcription using plasmid with DNA-binding domain fusionc

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pAS2-1 (BD) | pOZ57 (SafA-FL-BD) | pOZ185 (SafAn-BD) | pOZ187 (SafAc-BD) | pOZ24 (SpoVID-BD) | |

| pACT-2 (AD) | − | − | − | − | − |

| pOZ56 (SafA-FL-AD) | − | +++ | +++ | +++ | + |

| pOZ186 (SafAn-AD) | − | +++ | +++ | − | + |

| pOZ188 (SafAc-AD) | − | − | − | +++ | − |

| pOZ23 (SpoVID-AD) | − | + | + | + | − |

Yeast strains Y187 and Y190 contain fusions of products encoded by spoVID and full-length N- or C-terminal regions of safA to GAL4 activation and binding domains.

Plasmid constructs in pACT-2 (contains GAL4 activation domain [AD]) that were transformed into yeast strain Y190 (Clontech). The plasmids carry in-frame fusions of SafA-FL, SafA N-terminal region (SafAn), SafA C-terminal region (SafAc), or SpoVID to the GAL4 AD.

Detection of lacZ transcription by a colony lift assay as measured by time until the appearance of blue colonies. Plasmid constructs in pAS2-1 (binding domain [BD]) that were transformed into yeast strain Y187 (Clontech). The plasmids carry in-frame fusions of SafA-FL, SafA N-terminal region (SafAn), SafA C-terminal region (SafAc), or SpoVID to the GAL4 BD. The development of color in 30 min (+++), 1 h (+), and >8 h (−) was determined by testing three independent colonies for each pair of plasmids.

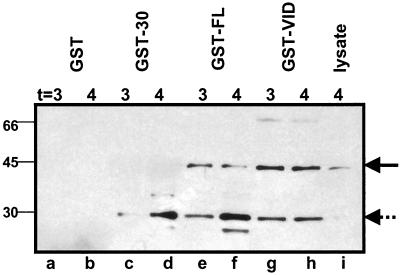

SpoVID interacts in vitro with SafA in extracts from B. subtilis

We tested whether GST proteins fused to SpoVID or to SafA could be used to capture SafA from extracts of B. subtilis cells. GST was fused to the N termini of SpoVID, SafA, and SafA-C30. These GST fusion proteins and GST alone were overproduced in E. coli BL21 and immobilized by binding to glutathione Sepharose beads. Soluble extracts taken from B. subtilis strain AOB90 (containing a FLAG-tagged version of SafA) (Table 1) harvested 3 and 4 h after the onset of sporulation were incubated with the GST fusion proteins bound to the beads. The interacting partners that remain bound to the GST fusion proteins after extensive washing were separated by SDS-PAGE and detected by immunoblotting using a monoclonal antibody against the FLAG epitope tag as a probe. The C-terminal FLAG-tagged versions of SafA, the full-length SafA and the 30-kDa short form, are weakly detected in the lysate from AOB90 harvested 4 h after the onset of sporulation (Fig. 1, lane i). GST alone did not pull-down either form of SafA (Fig. 1, lanes a and b), and the glutathione beads without bound GST fusion proteins did not do so either (not shown). However, GST-SpoVID and GST-FL-SafA pulled down both the full-length (45-kDa) and 30-kDa forms of SafA (Fig. 1, lanes e to h). The GST-C30-SafA pulled down only the 30-kDa form of SafA (Fig. 1, lanes c and d). These results are in agreement with the results of the yeast two-hybrid experiment (Table 3), establishing an interaction between SafA and SpoVID and between SafA with itself.

FIG. 1.

Capture of SafA from B. subtilis cell lysates with immobilized GST fusion proteins. Cell extracts from B. subtilis strain AOB90, taken 3 or 4 h after the onset of sporulation, were incubated with purified GST (lanes a and b), GST-C30-SafA (lanes c and d), GST- FL-SafA (lanes e and f), or GST-SpoVID (lanes g and h) on glutathione Sepharose beads and washed. Proteins retained on the beads were resolved by SDS-PAGE, blotted, and probed with anti-FLAG antibodies. A sample of the soluble cell extract taken from AOB90 4 h after the onset of sporulation before incubation with GST fusion proteins is shown in lane i. The positions of FLAG-tagged FL-SafA and C30-SafA proteins are indicated by the solid and broken arrows, respectively. The positions of molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are indicated to the left of the gel.

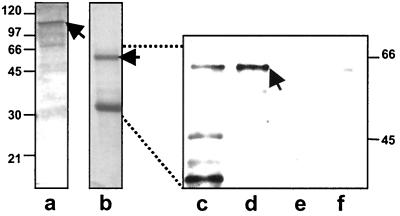

Interaction of SafA and SpoVID in E. coli extracts.

To eliminate the possibility that the apparent interaction of SafA and SpoVID seen in the experiments discussed above was mediated by another protein in the B. subtilis extracts, we used proteins produced in E. coli in an in vitro pull-down assay. The GST-SpoVID fusion protein was immobilized on glutathione beads as described above. The fusion protein migrated at approximately 110 kDa (Fig. 2, lane a). Western blotting of this preparation indicated that some of the smaller contaminating bands observed on the Coomassie blue-stained gel could be degradative products of the GST-SpoVID fusion (not shown). An epitope-tagged version of SafA (His6x-S.tag) was expressed in E. coli and purified by batch binding to a nickel-conjugated resin and elution with imidazole. The full-length His6x-S.tag-SafA fusion protein migrated as a 55-kDa protein, and smaller SafA-derived products migrated between sizes of 30 and 45 kDa (Fig. 2, lanes b and c). It is possible that some of the smaller minor species are due to degradation of the full-length product or premature termination of translation during production in E. coli. These products would contain the N-terminal six-His tag; therefore, they would be expected to bind to the nickel-conjugated resin. However, if the 30-kDa form seen in lane b were SafA-C30, it would not contain the N-terminal six-His tag. Therefore, if the 30-kDa form seen in lane b is SafA-C30, it may have an innate affinity for the nickel resin, or SafA-C30 may have copurified with SafA-FL because the two SafA products interact. We incubated the purified SafA preparation with the immobilized GST-SpoVID preparation, the immobilized GST protein, or with glutathione beads alone. After several washes with the incubation buffer, any retained SafA was detected on immunoblots with an antibody raised against SafA (Fig. 2). The SafA fusion protein was retained only in the reaction mixture containing the SpoVID fusion protein (Fig. 2, lane d). Since SafA and SpoVID formed a complex in preparations partially purified from extracts of E. coli, we conclude that no other B. subtilis protein is required for interaction of SafA and SpoVID. These results and those of the yeast two-hybrid experiments support the model that SafA and SpoVID interact directly.

FIG. 2.

Interaction of purified SpoVID with SafA from E. coli extracts. GST was fused to the N terminus of SpoVID (GST-SpoVID) and the N-terminal His6x-S.tag was fused to SafA (His6x-S.TagSafA), and both fusion proteins were overproduced in E. coli and partially purified. Coomassie blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gels of partially purified GST-SpoVID (expected molecular mass of 110 kDa) (indicated by an arrow) and His6x-SafA (expected molecular mass of 55 kDa) (indicated by an arrow) are shown in lanes a and b, respectively. GST-SpoVID was immobilized on glutathione Sepharose beads, incubated with His6x-S.TagSafA, and washed several times before separation by SDS-PAGE and blotted with anti-SafA antisera (lanes c to f). Immunoblot of purified His6x-S.TagSafA (lane c) and immunoblots detecting His6x-S.TagSafA captured by GST-SpoVID, GST, and glutathione beads (lanes d, e, and f, respectively) are shown. The dotted lines are used to emphasize the expanded scale of the gel representing lanes c to f. The positions of molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons ) are indicated to the right and left of the gel.

SafA is targeted to the forespore.

SafA is found in mature spores (29, 39). However, since SafA is synthesized in the mother cell under the direction of ςE, it is not known whether SafA is targeted exclusively to the developing endospore or whether SafA also accumulates in the mother cell membrane, as could be inferred from the presence of a cell wall-binding motif in its N terminus (29, 39). We used immunofluorescence microscopy to monitor the accumulation of SafA during sporulation. Samples were prepared from cultures harvested 2.5 and 4 h after the onset of sporulation and probed with anti-SafA antisera and a secondary anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) fluorescent conjugate. We used a nucleoid stain (DAPI) in our immunofluorescence experiments as a marker for the approximate stage of sporulation of each sporangium and to distinguish between the mother cell and forespore compartments (13, 22, 23, 31, 34). Differential interference contrast images were captured to mark the position of the whole cell. We examined a field of approximately 150 cells from each sample and recorded the number of cells that could be unambiguously classified as being in stages II to IV of sporulation (Table 4). Less than 100% of the cells in each field could be classified, because sporulation was not 100% efficient and the orientation of some cells in the field was not optimal for determining their stage of development. We also recorded the number and pattern of fluorescence labeling by the antibody (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Scoring and classification of the immunofluorescence labeling of SpoVID, SafA, and FLAG-tagged SafA

| Primary antibody | Strain or phenotype (time [h] into sporulation) | Total no. of cells examineda | No. of cells between stages II-IV of sporulationb

|

Classification of labeling patternc

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| II | III-IV | Diffuse | Spot | Cap | Ring | |||

| Anti-SpoVID | Wild type (2.5) | 152 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 0 |

| Wild type (4) | 140 | 8 | 56 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 40 | |

| SpoIVA (2.5) | 158 | 30 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| SpoIVA (4) | 160 | 5 | 51 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Anti-SafA | Wild type (2.5) | 151 | 34 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 0 |

| Wild type (4) | 160 | 13 | 59 | 0 | 0 | 97 | 0 | |

| SpoIVA (2.5) | 148 | 53 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 0 | 0 | |

| SpoIVA (4) | 150 | 13 | 51 | 0 | 54 | 0 | 0 | |

| SpoVID (2.5) | 156 | 56 | 0 | 0 | 102 | 0 | 0 | |

| SpoVID (4) | 159 | 8 | 46 | 0 | 77 | 0 | 0 | |

| Anti-β-galactosidase | AOB125 (4) | 130 | 8 | 45 | 96 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anti-FLAG | AOB90 (2.5) | 145 | 46 | 0 | 0 | 81 | 0 | 0 |

| AOB90 (4) | 142 | 24 | 58 | 0 | 0 | 78 | 0 | |

| AOB232 (2.5) | 155 | 59 | 0 | 0 | 51 | 0 | 0 | |

| AOB232 (4) | 151 | 11 | 45 | 0 | 64 | 0 | 0 | |

Total number of cells in the field of view.

Number of cells in either stage II or stages III to IV of sporulation as determined by DAPI staining. Stage II sporangia have a completely segregated forespore nucleoid, which remains more condensed than the mother cell nucleoid (Fig. 3B). Stage III sporangia show forespore and mother cell nucleoids with approximately the same degree of condensation (Fig. 3E).

Number of cells that displayed the following patterns of fluorescence labeling: diffuse, diffused in the mother cell (Fig. 3U); spot, spot at the mother cell forespore border (Fig. 3C); cap, brackets on both sides of the forespore compartment (Fig. 3F); ring, fluorescence around the entire forespore compartment (Fig. 4F).

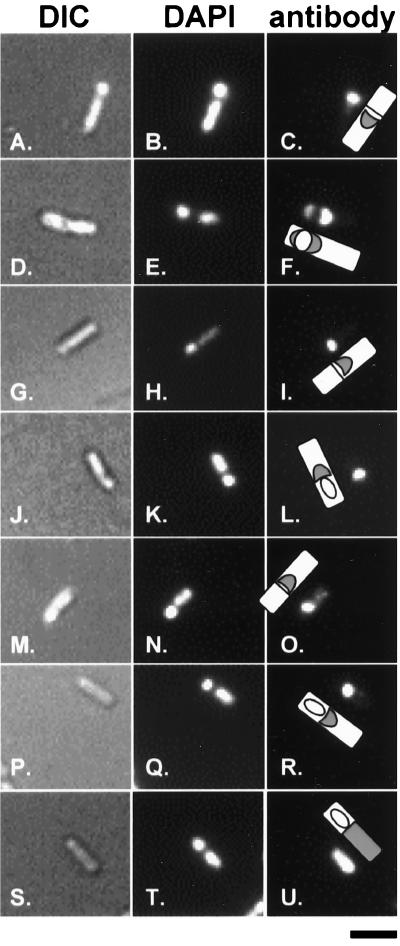

SafA localization appeared to occur in two stages. SafA was detected 2.5 h after the onset of sporulation as a band of fluorescence at the border of the mother cell and prespore compartments (Fig. 3A to C). By 4 h after the onset of sporulation, SafA protein was detected on both ends of the forespore as caps of material (Fig. 3D to F). The polar cap pattern formed by SafA is reminiscent of that formed by the CotE protein (13, 31). This pattern was disrupted by fusing the N-terminal half of SafA to β-galactosidase. In this case, the preferential accumulation of this SafA-N-LacZ fusion protein in the mother cell cytoplasm was detected with anti-β-galactosidase antibodies (Fig. 3S to U) or anti-SafA antisera (data not shown). No SafA was detectable in a safA deletion mutant (not shown). SafA localized to the prespore border in spoVID (Fig. 3G to I) and spoIVA (Fig. 3M to O) mutants 2.5 h after the onset of sporulation, but there was no migration of this material around the forespore to form the polar forespore caps by 4 h (Fig. 3J to L and P to R, respectively) or 6 h (data not shown) after the onset of sporulation. Therefore, the first stage of SafA localization, its targeting to the prespore border, is independent of SpoVID and SpoIVA, but the second stage, in which SafA is localized around the forespore, is dependent on both SpoIVA and SpoVID. SafA targeting around the forespore was independent of CotE (not shown).

FIG. 3.

Localization of SafA in wild-type, spoVID, and spoIVA mutant sporangia. Sporulation of B. subtilis strains was induced by starvation in DSM, and samples of each strain were taken 2.5 or 4 h after the onset of sporulation. Samples were labeled with anti-SafA antisera and a secondary rabbit IgG conjugated to a fluorescent molecule (panels C, F, I, L, O, and R) or with anti-β-galactosidase antibody and secondary mouse IgG conjugated to a fluorescent molecule (panel U). DAPI was used to stain the forespore and mother cell nucleoids, and differential interference contrast (DIC) was used to visualize the cell. Also shown are drawings illustrating our interpretations of the location of fluorescent label (gray) on a cell. Wild-type sporangia at 2.5 h (panels A to C) and 4 h (panels D to F), spoVID mutant sporangia at 2.5 h (panels G to I) and 4 h (panels J to L), spoIVA mutant sporangia at 2.5 h (panels M to O) and 4 h (panels P to R), and strain AOB125 containing a safA::lacZ translational fusion at 4 h (panels S to U) are shown. Bar, 2 μm.

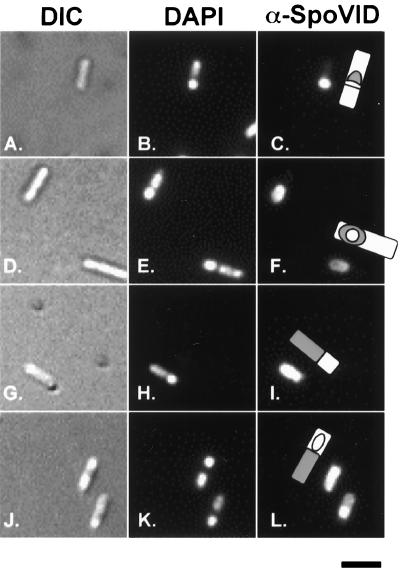

Since SafA localization around the forespore is dependent on both SpoVID and SpoIVA, we examined the accumulation of SpoVID by immunofluorescence microscopy using anti- SpoVID antisera. SpoVID localized to the sporulation septum 2.5 h (Fig. 4A to C), and by 4 h after the onset of sporulation, it appeared as a ring around the forespore (Fig. 4D to F). SpoVID was not detectable in a spoVID mutant control (data not shown). SpoVID localization occurred independent of the presence of CotE and SafA (data not shown); however, in spoIVA mutants, SpoVID was not targeted to the forespore and accumulated in the mother cell cytoplasm (Fig. 4G to I and J to L). Therefore, SpoIVA is required for SpoVID localization. However, since SpoIVA is required for SpoVID localization (Fig. 4G to I and J to L) and since SafA directly interacts with SpoVID (Fig. 1 and 2 and Table 3), it is likely that the dependency of SafA localization on SpoIVA reflects the requirement of SpoIVA for SpoVID localization.

FIG. 4.

Localization of SpoVID in wild-type and spoIVA mutant sporangia. Sporulation of B. subtilis strains was induced by starvation in DSM, and samples of each strain were taken 2.5 or 4 h after the onset of sporulation. Samples were labeled with anti-SpoVID antisera (α-SpoVID) and a secondary IgG conjugated to a fluorescent molecule. DAPI was used to stain the forespore and mother cell nucleoids, and differential interference contrast (DIC) was used to visualize the cell. Also shown are drawings illustrating our interpretations of the location of fluorescent label (gray) on a cell. Wild-type sporangia at 2.5 h (panels A to C) and 4 h (panels D to F) and spoIVA mutant sporangia at 2.5 h (panels G to I) and 4 h (panels J to L) are shown. Bar, 2 μm.

Correct localization of the C terminus of SafA requires full-length SafA.

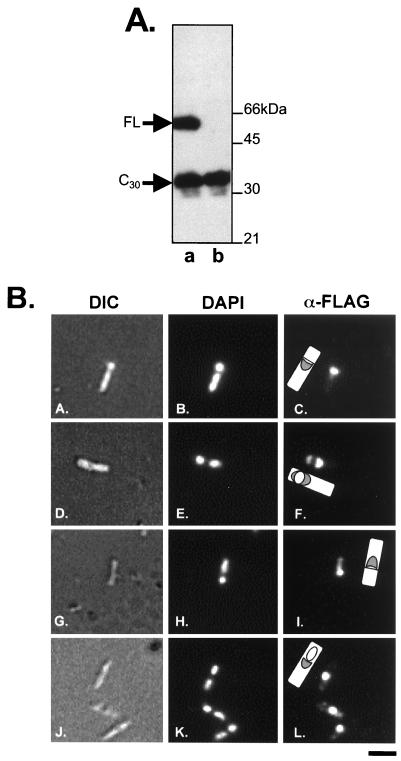

Multiple forms of SafA are found in the spore coat (29), and as noted above, N-terminal amino acid sequencing showed that the 30-kDa form (SafA-C30) represents the C-terminal amino acids beginning at codon 164 (38, 39). This form of SafA is produced by initiation of translation at codon 164 of the full-length safA mRNA (28). In order to examine the localization of SafA-C30, a FLAG epitope tag was fused in frame to the C terminus of SafA to create B. subtilis strain AOB90. The FLAG epitope had no effect on the function of SafA, as determined by spore resistance tests, germination assays, spore coat protein profiles, and pattern of accumulation by Western blotting (not shown). Also, the immunolocalization pattern of SafA in AOB90 was indistinguishable from that of the wild type using anti-SafA or anti-FLAG antibodies (compare Fig. 5B to Fig. 3A to F). However, we also isolated a strain that expresses only the 30-kDa C terminus of the protein by engineering a stop codon at codon 155 of safA. We compared whole-cell extracts, harvested 4 h after the onset of sporulation, of strains AOB90 (safA-FLAG) and AOB232 (safA155stop-FLAG) on immunoblots probed with an antibody against the FLAG epitope (Fig. 5A, lanes a and b, respectively). The stop codon mutation blocked accumulation of the full-length protein, but the 30-kDa form accumulated, presumably because translation was reinitiated at codon 164 (Fig. 5A, lane b). Additionally, the AOB232 mutant exhibited impaired spore coat assembly reminiscent of a safA deletion mutant (not shown). We used immunofluorescence microscopy to examine samples prepared from cultures of AOB90 and AOB232 harvested 2.5 and 4 h after the onset of sporulation and probed with anti-FLAG monoclonal antibodies and a secondary anti-mouse IgG fluorescent conjugate. The FLAG-tagged SafA-C30 was detected as spots of material at the prespore mother cell border, but it did not migrate around the forespore (Fig. 5B, panels G to I and J to L).

FIG. 5.

Localization of FLAG epitope-tagged SafA-FL and SafA-C30 during sporulation. (A) Immunoblot of B. subtilis whole-cell extracts harvested 4 h after the onset of sporulation probed with antibody against the FLAG epitope. Lane a, strain AOB90 (safA-FLAG); lane b, strain AOB232 (safA-stop155-FLAG). Full-length SafA-FLAG migrates at about 55 kDa (FL arrow), and SafA-C30-FLAG migrates at about 31 kDa (C30 arrow). (B) Sporulation of B. subtilis strains AOB90 and AOB232 was induced by starvation in DSM, and samples of each strain were taken 2.5 or 4 h after the onset of sporulation. Samples were labeled with anti-FLAG antibodies (α-FLAG) and a secondary IgG conjugated to a fluorescent molecule. DAPI was used to stain the forespore and mother cell nucleoids, and differential interference contrast (DIC) was used to visualize the cell. Drawings illustrating our interpretations of the location of fluorescent label (gray) on a cell are also shown. Strain AOB90 at 2.5 h (panels A to C) and 4 h (panels D to F) and strain AOB232 at 2.5 h (panels G to I) and 4 h (panels J to L) are shown. Bar, 2 μm.

DISCUSSION

Our work here focused on the interaction and the localization of two proteins, SafA and SpoVID, that are involved in the early stages of spore coat assembly. We showed that SafA is targeted early to the forespore, even before the forespore is fully engulfed. SafA localization around the engulfed forespore requires SpoVID (Fig. 3). SpoIVA is also required for SafA localization but possibly because SpoIVA is also required for SpoVID localization (Fig. 4G to L).

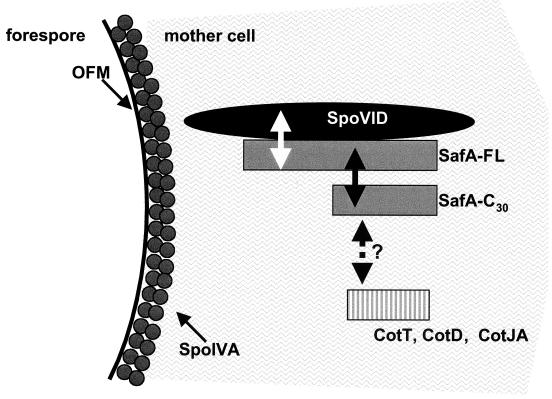

SafA probably interacts directly with SpoVID. The interactions between SafA and SpoVID are summarized in Fig. 6. We tested interactions with the N- and C-terminal regions of SafA independently in the yeast two-hybrid assay, and both regions showed a positive interaction with SpoVID. SpoVID may contact the C terminus of SafA at residues 203 to 210, which have been shown to strongly interact with SpoVID in vitro in a phage display assay (29). To explain the possible contact of SpoVID with the N-terminal region of SafA, we note that both SpoVID and SafA contain a cell wall binding motif at their C terminus and N terminus, respectively (29). Although the function of cell wall binding motifs is not well characterized, these motifs consist of a 50-amino-acid stretch of highly conserved residues that are thought to associate into higher-order structures that enable binding to cell wall material (18). The region containing this motif is critical for function of SpoVID since deletion of the last 24 amino acids of the 575-residue SpoVID protein results in its complete loss of function (2). It is possible that SpoVID may contact the N terminus of SafA through an interaction between their cell wall binding motifs.

FIG. 6.

Model of the interactions between SpoVID and SafA during the early stages of coat assembly. A section of a postengulfment cell is shown in cross-section. SpoIVA and SpoVID are located near the outer forespore membrane (OFM), and both are required for SafA localization. The sizes of the proteins are not drawn to scale. Interactions between SpoVID and SafA-FL (white arrow), SafA-FL and SafA-C30 (black arrow) are indicated. SafA may interact with proteins that have a high identity at the amino acid level to SafA-C30, such as CotT (EMBL accession no. BG10495), CotJA (EMBL accession no. BG11799), and CotD (EMBL accession no. BG10493); this possibility is indicated by the black broken arrow with a question mark. SpoVID may act as a platform for the localization and assembly of SafA and other SpoVID-associated proteins.

It is not clear whether the short form of SafA (SafA-C30) requires the full-length SafA (SafA-FL) for its localization. Rather than localizing as brackets around the forespore as does SafA-FL, SafA-C30 was localized to the septal proximal pole of the forespore as a spot of material in a mutant that did not express SafA-FL. Therefore, SafA-C30 targeting around the forespore may require interaction with SafA-FL or with the SpoVID-SafA-FL complex. The interaction between the C-terminal region of SafA and SpoVID may be stronger, as this was presumably the interaction uncovered in a phage display screening (29). It may be that this interaction occurs first, bringing together the two proteins, while a second interaction (between the N-terminal region of SafA and SpoVID) results in the formation of a complex with the proper topology to recruit additional proteins, including the SafA-C30 polypeptide. Formation of a SpoVID-SafA-C30 complex in the absence of full-length SafA may represent a dead-end complex with respect to the assembly of more SafA-C30, explaining why this form never encircles the forespore. Alternatively, SafA-C30 may always be targeted to and remain localized at one pole of the forespore. This pattern of localization may be independent of the full-length SafA protein. Other coat proteins such as TasA have been suggested to have a polar targeting pattern (33).

SafA is probably not the only protein that interacts with SpoVID. Inactivation of SafA results in spores with abnormal coats that are missing several proteins and are loosely attached to the underlying layers (29, 39). Inactivation of SpoVID however, has a more severe phenotype since the coat does not remain attached to the forespore and accumulates as swirls of material in the mother cell cytoplasm (2). Therefore, there are probably other proteins in addition to SafA that interact with SpoVID to help in adherence of the coat to forespore. CotT, CotD, and CotJA are possible candidates for SpoVID-interacting proteins since their amino acid sequences are similar to that of the C terminus of SafA (Fig. 6) (20, 29). Like SpoVID and SafA, CotJA is expressed under control of ςE in the mother cell and is probably associated with the undercoat (15, 35). CotT and CotD are synthesized later under the control of ςK and are probably components of the inner coat (1, 4, 6, 7, 16). Since SafA-C30 interacts with itself and with full-length SafA, it is also possible that SafA interacts with similar regions in CotT, CotD, and CotJA (Fig. 6).

SpoVID is required for targeting of SafA to the forespore, probably by direct interaction between SpoVID and SafA. However, it is not known whether SafA interacts with SpoVID that is already localized to the forespore surface or whether SafA interacts with SpoVID in the mother cell cytoplasm, followed by targeting of the preassembled SpoVID-SafA complex to the forespore membrane. We favor the model that SafA and SpoVID interact before targeting of the complex to the forespore. Two other coat proteins, CotJA and CotJC, interact, and each is required to target the another (35). This observation is most easily explained if CotJA and CotJC interact before assembly into the coat. SpoVID does not require SafA for localization to the forespore. However, as described above, it is likely that SpoVID interacts with other proteins. Therefore, in the absence of SafA, SpoVID finds other interacting partners for assembly into the coat. If this model is correct, then SpoVID may act as a molecular usher, guiding several proteins as preassembled complexes to the developing spore coat.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge Anita Corbett for help with the fluorescence microscopy and Fang F. Yin for technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by PHS grant GM54395 from the National Institutes of Health to C. P. Moran, Jr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aronson A I, Song H Y, Bourne N. Gene structure and precursor processing of a novel Bacillus subtilis spore coat protein. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:437–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beall B, Driks A, Losick R, Moran C P., Jr Cloning and characterization of a gene required for assembly of the Bacillus subtilis spore coat. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1705–1716. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.6.1705-1716.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bi E F, Lutkenhaus J. FtsZ ring structure associated with division in Escherichia coli. Nature. 1991;354:161–164. doi: 10.1038/354161a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourne N, FitzJames P C, Aronson A I. Structural and germination defects of Bacillus subtilis spores with altered contents of a spore coat protein. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6618–6625. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.20.6618-6625.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cutting S, Anderson M, Lysenko E, Page A, Tomoyasu T, Tatematsu K, Tatsuta T, Kroos L, Ogura T. SpoVM, a small protein essential to development in Bacillus subtilis, interacts with the ATP-dependent protease FtsH. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5534–5542. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5534-5542.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donovan W, Zheng L B, Sandman K, Losick R. Genes encoding spore coat polypeptides from Bacillus subtilis. J Mol Biol. 1987;196:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90506-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Driks A. Bacillus subtilis spore coat. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:1–20. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.1.1-20.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Driks A, Roels S, Beall B, Moran C P, Jr, Losick R. Subcellular localization of proteins involved in the assembly of the spore coat of Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 1994;8:234–244. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Errington J. Bacillus subtilis sporulation: regulation of gene expression and control of morphogenesis. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:1–33. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.1.1-33.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fields S, Song O. A novel genetic system to detect protein-protein interactions. Nature. 1989;340:245–246. doi: 10.1038/340245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fields S, Sternglanz R. The two-hybrid system: an assay for protein-protein interactions. Trends Genet. 1994;10:286–292. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(90)90012-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guarente L. Strategies for the identification of interacting proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1639–1641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harry E J, Pogliano K, Losick R. Use of immunofluorescence to visualize cell-specific gene expression during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3386–3393. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.12.3386-3393.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henriques A O, Beall B W, Moran C P., Jr CotM of Bacillus subtilis, a member of the α-crystallin family of stress proteins, is induced during development and participates in spore outer coat formation. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1887–1897. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.6.1887-1897.1997. . (Erratum, 179:4455.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henriques A O, Beall B W, Roland K, Moran C P., Jr Characterization of cotJ, a ςE-controlled operon affecting the polypeptide composition of the coat of Bacillus subtilis spores. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3394–3406. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.12.3394-3406.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henriques A O, Moran C P., Jr Structure and assembly of the bacterial endospore coat. Methods (Orlando) 2000;20:95–110. doi: 10.1006/meth.1999.0909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hultgren S J, Abraham S, Caparon M, Falk P, St. Geme J W, Normark S. Pilus and nonpilus bacterial adhesins: assembly and function in cell recognition. Cell. 1993;73:887–901. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90269-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joris B, Englebert S, Chu C P, Kariyama R, Daneo-Moore L, Shockman G D, Ghuysen J M. Modular design of the Enterococcus hirae muramidase-2 and Streptococcus faecalis autolysin. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;70:257–264. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90707-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kodama T, Takamatsu H, Asai K, Kobayashi K, Ogasawara N, Watabe K. The Bacillus subtilis yaaH gene is transcribed by SigE RNA polymerase during sporulation, and its product is involved in germination of spores. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4584–4591. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.15.4584-4591.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kunst F, Ogasawara N, Moszer I, Albertini A M, Alloni G, Azevedo V, Bertero M G, Bessieres P, Bolotin A, Borchert S, Borriss R, Boursier L, Brans A, Braun M, Brignell S C, Bron S, Brouillet S, Bruschi C V, Caldwell B, Capuano V, Carter N M, Choi S K, Codani J J, Connerton I F, Danchin A, et al. The complete genome sequence of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature. 1997;390:249–256. doi: 10.1038/36786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levin P A, Fan N, Ricca E, Driks A, Losick R, Cutting S. An unusually small gene required for sporulation by Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:761–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis P J, Nwoguh C E, Barer M R, Harwood C R, Errington J. Use of digitized video microscopy with a fluorogenic enzyme substrate to demonstrate cell- and compartment-specific gene expression in Salmonella enteritidis and Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:655–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis P J, Partridge S R, Errington J. Sigma factors, asymmetry, and the determination of cell fate in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3849–3853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macnab R M. Genetics and biogenesis of bacterial flagella. Annu Rev Genet. 1992;26:131–158. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.26.120192.001023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin-Verstraete I, Debarbouille M, Klier A, Rapoport G. Mutagenesis of the Bacillus subtilis “−12, −24” promoter of the levanase operon and evidence for the existence of an upstream activating sequence. J Mol Biol. 1992;226:85–99. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90126-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moir A, Smith D A. The genetics of bacterial spore germination. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1990;44:531–553. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.44.100190.002531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicholson W L, Setlow P. Sporulation, germination, and outgrowth. In: Harwood C R, Cutting S M, editors. Molecular biology methods for Bacillus. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley and Sons; 1990. pp. 391–450. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ozin A J, Costa T, Henriques A O, Moran C P., Jr Alternative translation initiation produces a short form of a spore coat protein in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:2032–2040. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.6.2032-2040.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ozin A J, Henriques A O, Yi H, Moran C P., Jr Morphogenetic proteins SpoVID and SafA form a complex during assembly of the Bacillus subtilis spore coat. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1828–1833. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.7.1828-1833.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piggot P J, Coote J G. Genetic aspects of bacterial endospore formation. Bacteriol Rev. 1976;40:908–962. doi: 10.1128/br.40.4.908-962.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pogliano K, Harry E, Losick R. Visualization of the subcellular location of sporulation proteins in Bacillus subtilis using immunofluorescence microscopy. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:459–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18030459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Price K D, Losick R. A four-dimensional view of assembly of a morphogenetic protein during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:781–790. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.3.781-790.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Serrano M, Zilhao R, Ricca E, Ozin A J, Moran C P, Jr, Henriques A O. A Bacillus subtilis secreted protein with a role in endospore coat assembly and function. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3632–3643. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.12.3632-3643.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Setlow B, Magill N, Febbroriello P, Nakhimovsky L, Koppel D E, Setlow P. Condensation of the forespore nucleoid early in sporulation of Bacillus species. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6270–6278. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.19.6270-6278.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seyler R W, Jr, Henriques A O, Ozin A J, Moran C P., Jr Assembly and interactions of cotJ-encoded proteins, constituents of the inner layers of the Bacillus subtilis spore coat. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:955–966. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1997.mmi532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sleytr U B, Beveridge T J. Bacterial S-layers. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:253–260. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01513-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stragier P, Losick R. Molecular genetics of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Annu Rev Genet. 1996;30:297–341. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takamatsu H, Kodama T, Imamura A, Asai K, Kobayashi K, Nakayama T, Ogasawara N, Watabe K. The Bacillus subtilis yabG gene is transcribed by SigK RNA polymerase during sporulation, and yabG mutant spores have altered coat protein composition. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1883–1888. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.7.1883-1888.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takamatsu H, Kodama T, Nakayama T, Watabe K. Characterization of the yrbA gene of Bacillus subtilis, involved in resistance and germination of spores. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4986–4994. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.16.4986-4994.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]