Abstract

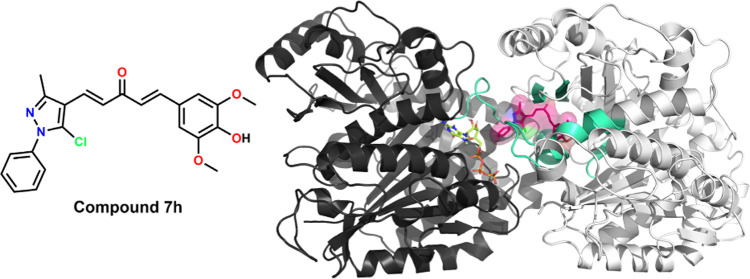

Addressing the growing burden of cancer and the shortcomings of chemotherapy in cancer treatment are the current research goals. Research to overcome the limitations of curcumin and to improve its anticancer activity via its heterocycle-fused monocarbonyl analogues (MACs) has immense potential. In this study, 32 asymmetric MACs fused with 1-aryl-1H-pyrazole (7a–10h) were synthesized and characterized to develop new curcumin analogues. Subsequently, via initial screening for cytotoxic activity, nine compounds exhibited potential growth inhibition against MDA-MB-231 (IC50 2.43–7.84 μM) and HepG2 (IC50 4.98–14.65 μM), in which seven compounds showing higher selectivities on two cancer cell lines than the noncancerous LLC-PK1 were selected for cell-free in vitro screening for effects on microtubule assembly activity. Among those, compounds 7d, 7h, and 10c showed effective inhibitions of microtubule assembly at 20.0 μM (40.76–52.03%), indicating that they could act as microtubule-destabilizing agents. From the screening results, three most potential compounds, 7d, 7h, and 10c, were selected for further evaluation of cellular effects on breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells. The apoptosis-inducing study indicated that these three compounds could cause morphological changes at 1.0 μM and could enhance caspase-3 activity (1.33–1.57 times) at 10.0 μM in MDA-MB-231 cells, confirming their apoptosis-inducing activities. Additionally, in cell cycle analysis, compounds 7d and 7h at 2.5 μM and 10c at 5.0 μM also arrested MDA-MB-231 cells in the G2/M phase. Finally, the results from in silico studies revealed that the predicted absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and the toxicity (ADMET) profile of the most potent MACs might have several advantages in addition to potential disadvantages, and compound 7h could bind into (ΔG −10.08 kcal·mol–1) and access wider space at the colchicine-binding site (CBS) than that of colchicine or nocodazole via molecular docking studies. In conclusion, our study serves as a basis for the design of promising synthetic compounds as anticancer agents in the future.

1. Introduction

Globally, 18,094,716 million cases of cancer were diagnosed in 2020, according to the Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN). Among those, breast and liver cancer were the most common ones, ranking first (11.7%) and seventh (4.7%) in incidence rate, and ranking fifth (6.9%) and third (8.3%) in mortality, respectively.1 With increasing burden in almost every country, prevention and treatment of cancer are significant public health challenges. Concerning cancer treatment, chemotherapy, a method using chemical drugs to kill and/or inhibit the growth and proliferation of cancer cells—alongside surgical operation, radiotherapy, and biotherapy—is the mainstay. Nevertheless, this treatment method has been facing several challenges. For instance, several active pharmaceutical ingredients might exhibit poor solubility, poor stability in the GI tract, and poor permeability through the intestinal epithelium such as paclitaxel (Taxol) or doxorubicin (Adriamycin). These unfavorable physicochemical or pharmacokinetic properties could lead to their limited bioavailabilities, making them unsuitable for oral administration and requiring chemical modification or formulation development to be used at their therapeutic doses. Moreover, the biggest problem of chemotherapy chemicals is their inability to distinguish between cancer cells and normal ones, which might cause significant toxicity and side effects and limit the efficacy due to their low therapeutic index.2,3

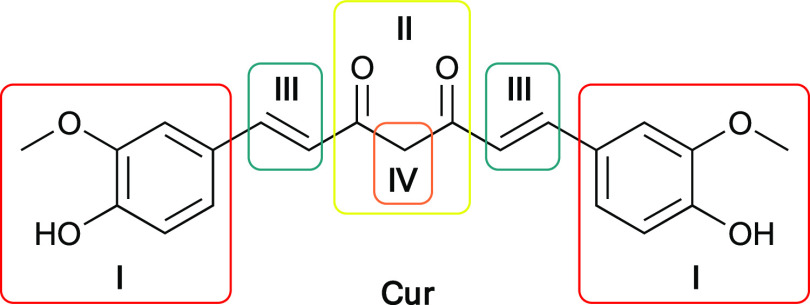

To overcome the shortcomings of chemotherapy in cancer treatment, recent research strategies are efforts to discover new active compounds with higher safety and efficacy profiles. Natural products have been excellent sources of medicinal agents, either by themselves or as a template for synthetic agents.4 Curcumin or diferuloylmethane (Cur) is a natural polyphenolic and the major component in the rhizome of Curcuma longa Linn. (Turmeric) (Figure 1).5 The ability of curcumin to modulate various signal cascades and pathways, such as p53,6 NF-κB,7 AP-1 family,8 and STAT family,9 confirms the potential of curcumin to be an effective regulator of a diverse variety of molecular targets.10 Therefore, it possesses a diverse range of biological activities, such as anticarcinogenic,11 antitumor,12 anti-inflammatory,13 and also being nontoxic even at high dosages.14 Despite its great biological activities, curcumin is not widely accepted as an ideal pharmacologically effective molecule due to some limitations in physicochemical properties such as poor water and plasma solubility, chemical and biological instability, and poor oral bioavailability.15 Hence, the development of synthesized analogues of curcumin, with a similar safety profile, as well as increased activity and improved oral bioavailability, has scientific significance. Among prominent sites of structure modification (Figure 1), the β-diketone moiety was found to be a specific substrate of aldo–keto reductases and could be in vivo metabolized rapidly whereas monocarbonyl analogues of curcumin (MACs) possessing a five-carbon dienone linker (e.g., a–i) have generally improved pharmacokinetic profiles than that of curcumin.16,17

Figure 1.

Structure of curcumin and prominent sites of structure modification: aryl sidechains (I), β-diketone (II), olefin linkers (III), and an active methylene group (IV).

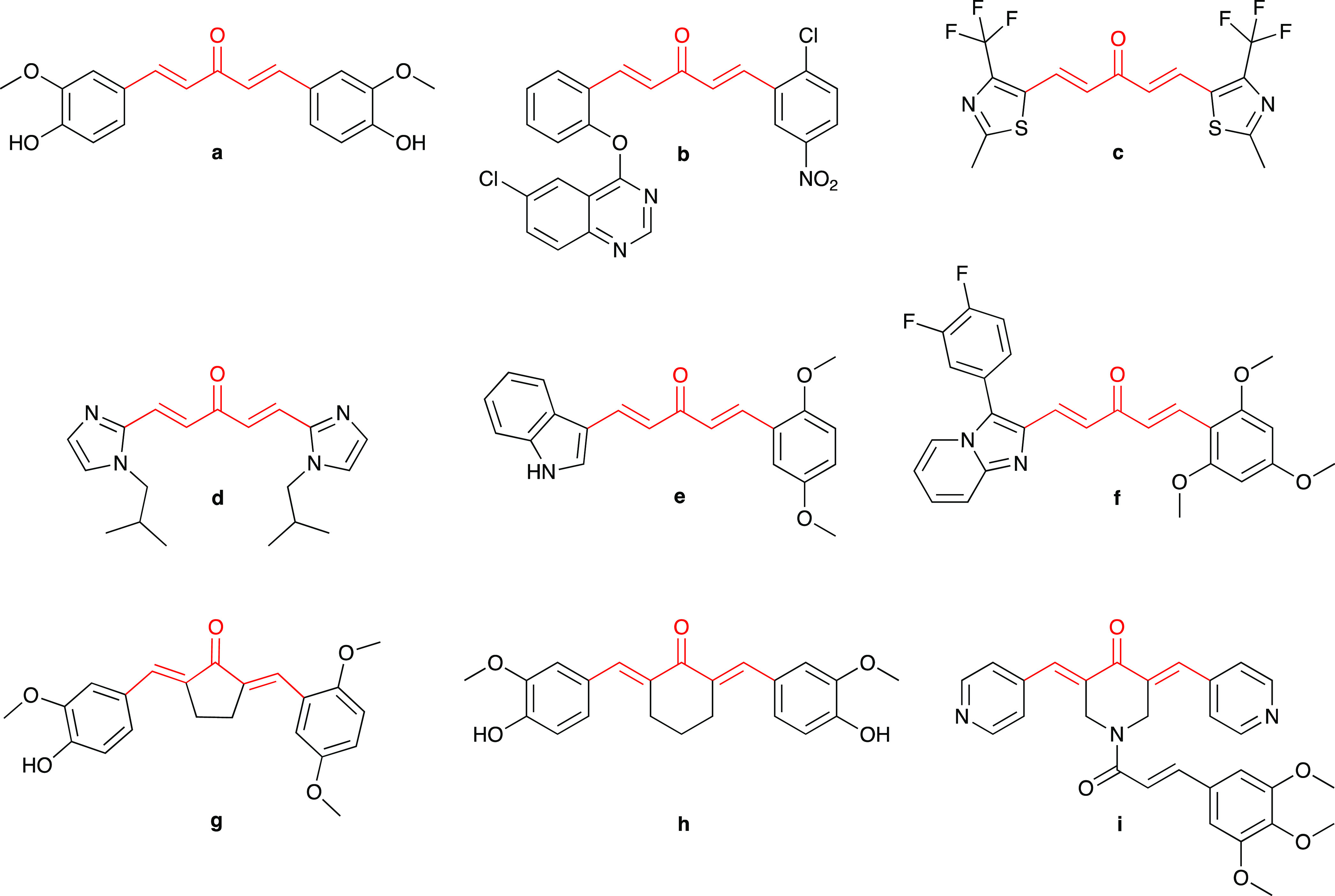

Moreover, MACs fused with five- or six-membered heterocycles such as quinazoline b,18 thiazole c,19 imidazole d,20 indole e,21 and imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine f,22 as well as MACs that have the ketone moiety in the dienone motif replaced with cyclopentanone g,23 cyclohexanone h,24 or 1H-piperidine-4-one i,25 have been well studied for improving anticancer potency than curcumin (Figure 2). Thus, the general structure portrayed by potential compounds composed of one (hetero)aryl linked with another by penta-1,4-dien-3-one moiety could be considered an optimal scaffold for developing novel MACs as potential anticancer agents.22

Figure 2.

Chemical structure of several symmetric MACs (a, c, and d) and asymmetric MACs (b, e, f, g, h, and i) suggests that the acetone moiety in the five-carbon dienone linker (a) could be replaced by cyclopentanone (g), cyclohexanone (h), and 1H-piperidine-4-one (i) while the phenyl ring could also be replaced by several heterocyclics such as quinazoline (b), thiazole (c), imidazole (d), indole (e), imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine (f), and pyridine (i).

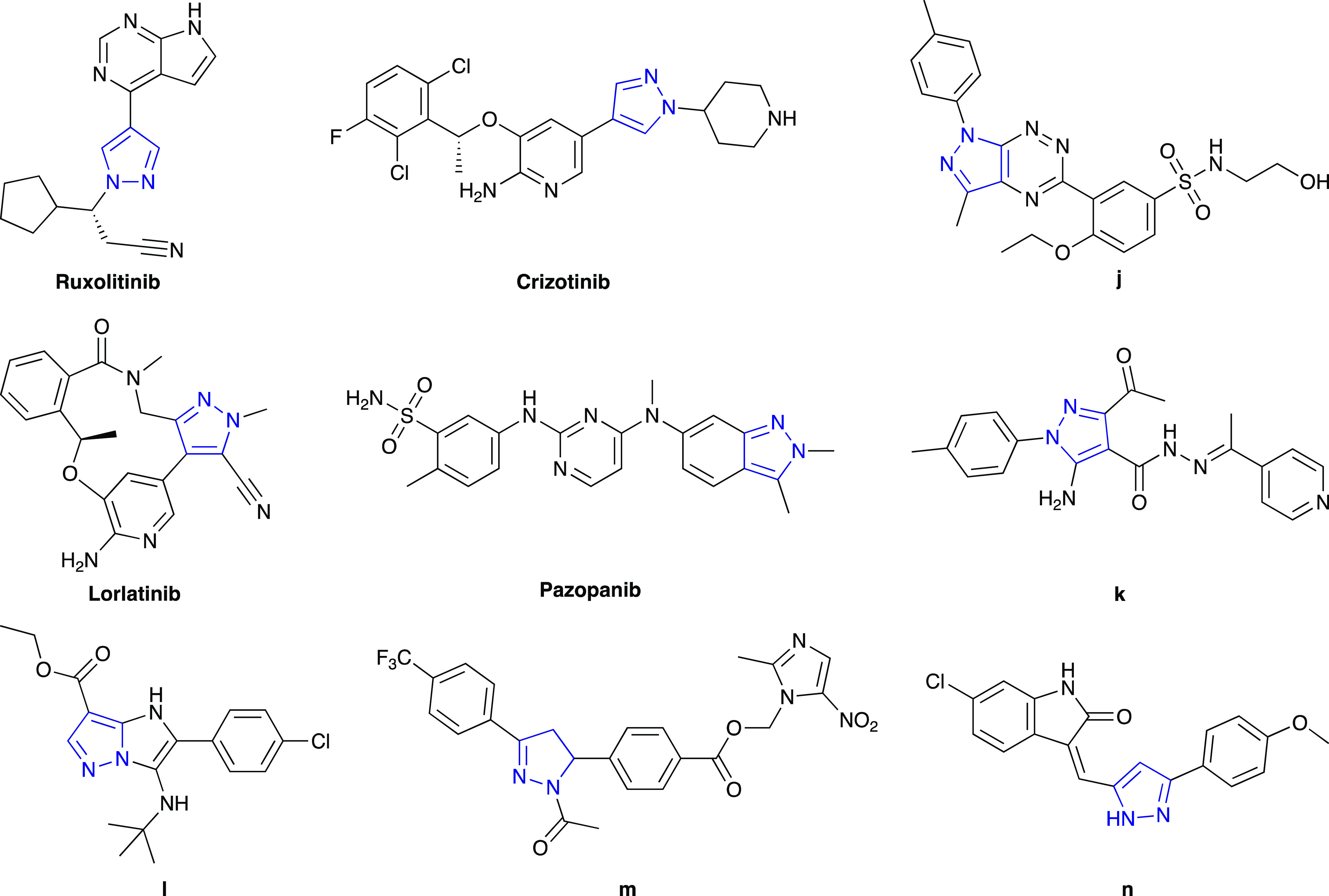

On the other hand, 1H-pyrazole is a five-membered heterocycle constituting a class of compounds that received substantial attention due to their synthetic and effective biological importance.26 In particular, different bioactivity pyrazole-containing structures were described as anticancer,27−29 antibacterial,30 anti-inflammatory,31 antituberculosis,32 and antiviral agents.33 Regarding anticancer activities, several drugs possessing 1H-pyrazole are commercially available and used to treat cancer such as pazopanib (Votrient), ruxotlitinib (Jakavi), crizotinib (Xalkori), encorafenib (Braftovi), and lorlatinib (Lorbrena). Previous studies have shown that 1H-pyrazole derivatives could exhibit antiproliferation activity in vitro and antitumor activity in vivo, suggesting that anticancer agents based on 1H-pyrazole structure are still of significant interest. Recent studies showed that compounds containing 1H-pyrazole could inhibit the growth of several cancer cell types such as lung cancer, brain cancer, colorectal cancer, renal cancer, prostate cancer, pancreatic cancer, and blood cancer.27−29 Among them, the antiproliferation activity compounds containing the 1-aryl-1H-pyrazole scaffold, especially on breast cancer cells MDA-MB-231 (j) and liver cancer cells HepG2 (k), were also reported.34−37 The anticancer activities of 1H-pyrazole derivatives demonstrated that their inhibitory activities of various cancer-related targets such as topoisomerase II (l),38 EGFR (m),36,39 MEK,40 VEGFR,36,41 GGT1,37 microtubule (n),42,43 HDACs,44 Pim 1–3,45 and carbonic anhydrase IX and XII46 could lead to the construction of promising compounds (Figure 3).47,48

Figure 3.

Chemical structures of anticancer drugs (pazopanib, ruxolitinib, crizotinib, and lorlatinib) and several pyrazole-containing anticancer agents (j–n) from previous studies.

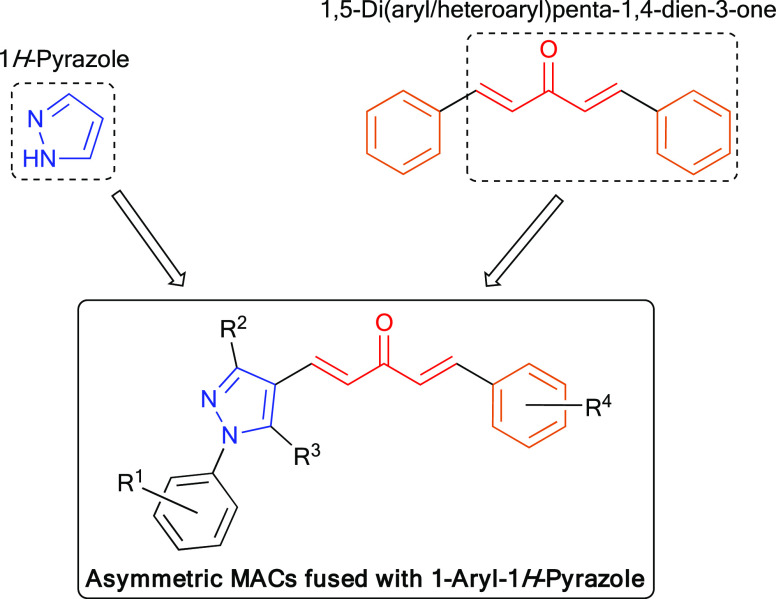

The synthetic feasibility and biological activities26,47,48 of 1H-pyrazole derivatives inspired us to synthesize asymmetric MACs fused with 1H-pyrazole. In the structure of the targeted MACs, we aimed to retain one side of the symmetric structure of curcumin, of which the phenyl ring was substituted with hydroxy or alkoxy groups. This phenyl ring could be connected with the 1-aryl-1H-pyrazole scaffold via a five-carbon dienone linker motif (Figure 4). Regarding the substitution on the phenyl ring at the N1 position of 1H-pyrazole, we chose the nitro group due to the anticancer potential of nitro-containing bioactive compounds described in the literature elsewhere,49 some of which contained 2-, 3-, or 4-nitrophenyl moieties.18,50 The cytotoxicities of compounds containing this functional group have been described through various mechanisms, such as inhibition of topoisomerase,51 alkylation of DNA,52 or inhibition of tubulin polymerization.53,54

Figure 4.

Design of new symmetric and asymmetric MACs fused with 1-aryl-1H-pyrazole as anticancer agents.

In line with previous studies in the development of curcumin analogue-fused heterocycle, herein, we reported MAC-fused 1-Aryl-1H-pyrazole derivatives as desired anticancer agents.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemistry

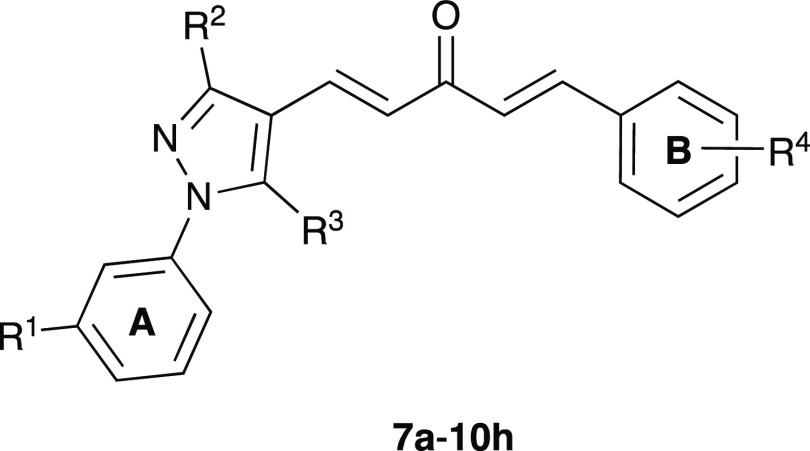

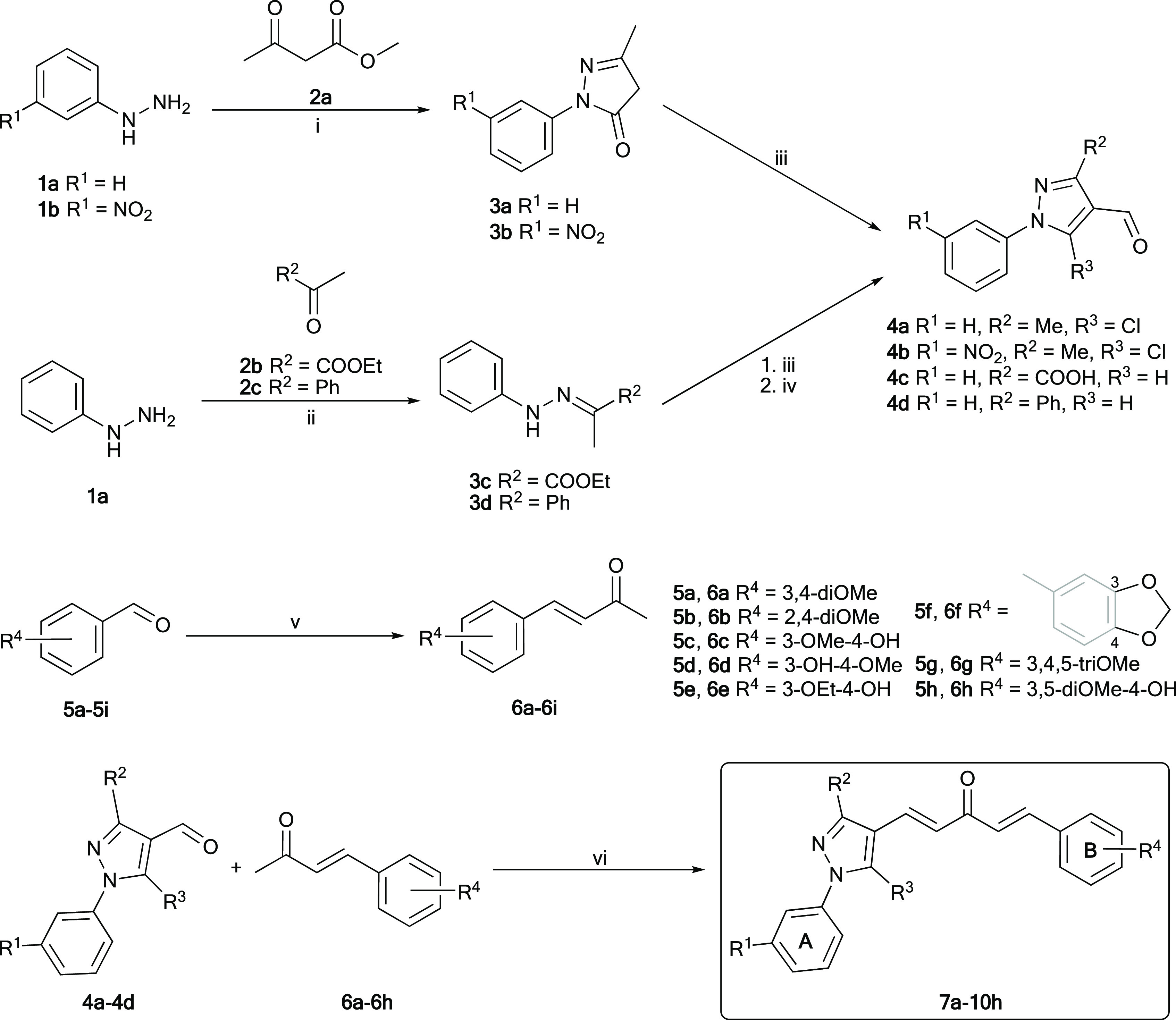

In this study, the target compounds, 32 asymmetric MACs, which were derivatives of (1E,4E)-1-phenyl-5-(1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)penta-1,4-dien-3-ones (7a–10h), were synthesized by employing KOH-catalyzed Claisen–Schmidt condensation between (i) a 1H-pyrazole-4-carbaldehyde derivative (4a–4d) with (ii) a 4-phenylbut-3-en-2-one derivative (6a–6h) (Scheme 1). 3-Nitro group was selected to be substituted on the phenyl ring at the N1 position of 1H-pyrazole (8a–8h), due to its potent anticancer activity.49−54 Among the synthetic compounds, 7a, 7c, 7g, 10a, and 10g were previously described in the literature.55−57 All of these compounds were simply purified by recrystallization in ethanol, ethyl acetate, acetone, or ethyl acetate–ethanol mixture (1:1); or by column chromatography with 25% ethyl acetate in n-hexane as the eluent. Finally, the target compounds were well characterized by spectroscopic techniques such as IR, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), high-resolution mass spectrometry (HR-MS), 1H-, and 13C-NMR, which were in full accordance with the designed structures (Figures S26–S153). The 1H- and 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6) spectra of asymmetric MACs showed the disappearance of specific signals belonging to the aldehyde (9.90–10.32 ppm in 1H- and 184.0–186.3 ppm in 13C-NMR) in 1H-pyrazole-4-carbaldehydes (4a–4d) (Figures S1–S9) and the methyl ketone (2.34–2.39 ppm in 1H- and 27.0–27.3 ppm in 13C-NMR) in 4-phenylbut-3-en-2-ones (6a–6h) (Figures S10–S25). Furthermore, the 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6) spectrum of these MACs showed two pairs of doublet signals with a J value of ∼16.0 Hz, confirming the (E) configuration of two double bonds formed by Claisen–Schmidt condensation.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of 1H-Pyrazole-4-carbaldehydes (4a–4d), 4-Phenylbut-3-en-2-ones (6a–6i), and Asymmetric MACs Fused with 1-Aryl-1H-pyrazole (7a–10h).

Reagents and conditions: (i) AcOH, reflux, 1 h (3a) or EtOH, 65–70 °C, 2 h (3b), 81–91%. (ii) AcOH, EtOH, reflux, 5 h, 91–92%. (iii) POCl3, DMF, 0–5 to 70–80 °C, 5–6 h, 55–95%. (iv, for 4c only) KOH, EtOH–H2O (3:2), reflux, 30 min, 85%. (v) KOH, Me2CO–H2O (2:3), 0–5 °C–r.t. (or 60 °C), 2–48 h, 57–87%. (vi) 4% (w/v) KOH in EtOH or saturated KOH in t-BuOH, 0–5 °C–r.t. (or 60 °C), 4–24 h, 35–54%. Rings A and B were used to denote that the phenyl rings belonged to phenyl hydrazine and benzaldehyde derivatives, respectively.

2.2. Biological Activities

2.2.1. In Vitro Cytotoxicity

All synthetic MACs (7a–10h) were screened for their in vitro cytotoxicity against MDA-MB-231 and HepG2 cancer cell lines using the MTT assay.58 Overall, the IC50 values (μM) of synthesized MACs suggested that the synthesized compounds exhibited stronger cytotoxicity on MDA-MB-231 than on HepG2 cells (Table 1). When compared to those of curcumin and paclitaxel, some compounds exhibited potential cytotoxicity against cancer cells. In particular, on MDA-MB-231 cells, stronger cytotoxicity than curcumin was found in 21 MACs in which seven of them were significantly stronger than paclitaxel. The respective figures for HepG2 cells were 16 MACs compared to curcumin in which six were superior to paclitaxel. Regarding different substitutions on 1H-pyrazole of asymmetric MACs (7a–10h), compounds 9a–9h possessing 3-carboxy-1H-pyrazole were found to be less cytotoxic than the others on MDA-MB-231 and appeared to be inactive on HepG2 cells. Meanwhile, compounds 7a–7h, 8a–8h, and 10a–10h possessing 3-methyl or 3-phenyl-1H-pyrazole were found to be more potent on two cell lines. Concerning different substitutions on ring B of asymmetric MACs, nonphenolic-substituted MACs generally exhibited less cell growth inhibition activity than the phenolic-substituted, except 3,4-dimethoxy- and 3,4,5-trimethoxy-substituted MACs. Among weakly cytotoxic/inactive compounds, which were possibly attributed to the poor absorption and permeability of these compounds through the cell membrane, one can find too hydrophobic structures such as nonphenolic-substituted ones carrying 1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazole or too hydrophilic phenolic-substituted compounds carrying 3-carboxy-1H-pyrazole. For this reason, the hydrophobic/hydrophilic nature of the compounds might be a major factor in their cytotoxicity.

Table 1. Chemical Structure of Asymmetric MACs Fused with 1-Aryl-1H-pyrazole-Synthesized 7a–10h, Their Cytotoxic Activity (IC50, μM), and Selectivity Index (SI) of MACs Demonstrating the Most Potent Cytotoxicities.

| substitution |

IC50 (μM)a |

SIf |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | MDA-MB-231b | HepG2c | LLC-PK1d | MDA-MB-231b | HepG2c |

| 7a | H | Me | Cl | 3,4-diOMe | 6.60 ± 0.16 | 11.55 ± 1.20 | NDe | ND | ND |

| 7b | H | Me | Cl | 2,4-diOMe | 13.29 ± 0.39 | >25 | ND | ND | ND |

| 7c | H | Me | Cl | 3-OMe-4-OH | 7.71 ± 0.32 | 8.00 ± 0.87* | 9.56 ± 0.15 | 1.24 | 1.19 |

| 7d | H | Me | Cl | 3-OH-4-OMe | 5.61 ± 0.24* | 14.20 ± 0.77 | 16.13 ± 0.22 | 2.88 | 1.14 |

| 7e | H | Me | Cl | 3-OEt-4-OH | 13.49 ± 1.43 | 13.18 ± 1.41 | ND | ND | ND |

| 7f | H | Me | Cl | 3,4-methylendioxy | 16.67 ± 0.07 | >25 | ND | ND | ND |

| 7g | H | Me | Cl | 3,4,5-triOMe | 7.84 ± 0.07 | 13.03 ± 0.12 | ND | ND | ND |

| 7h | H | Me | Cl | 3,5-diOMe-4-OH | 3.64 ± 0.02* | 6.03 ± 0.06* | 12.91 ± 0.16 | 3.55 | 2.14 |

| 8a | NO2 | Me | Cl | 3,4-diOMe | 6.89 ± 0.31 | 7.19 ± 0.37* | 21.04 ± 0.47 | 3.05 | 2.93 |

| 8b | NO2 | Me | Cl | 2,4-diOMe | 12.26 ± 1.29 | 18.32 ± 3.14 | ND | ND | ND |

| 8c | NO2 | Me | Cl | 3-OMe-4-OH | 7.00 ± 0.02 | 16.60 ± 0.45 | ND | ND | ND |

| 8d | NO2 | Me | Cl | 3-OH-4-OMe | 7.25 ± 0.08 | 25.31 ± 0.30 | ND | ND | ND |

| 8e | NO2 | Me | Cl | 3-OEt-4-OH | 15.11 ± 0.20 | 11.18 ± 0.04 | ND | ND | ND |

| 8f | NO2 | Me | Cl | 3,4-methylendioxy | >25 | >25 | ND | ND | ND |

| 8g | NO2 | Me | Cl | 3,4,5-triOMe | 2.43 ± 0.04* | 14.65 ± 0.10 | 5.93 ± 0.04 | 2.44 | 0.40 |

| 8h | NO2 | Me | Cl | 3,5-diOMe-4-OH | 2.56 ± 0.01* | 6.69 ± 0.04* | 15.38 ± 0.05 | 6.01 | 2.30 |

| 9a | H | COOH | H | 3,4-diOMe | 19.32 ± 2.61 | >25 | ND | ND | ND |

| 9b | H | COOH | H | 2,4-diOMe | 19.90 ± 6.77 | >25 | ND | ND | ND |

| 9c | H | COOH | H | 3-OMe-4-OH | 22.61 ± 4.74 | >25 | ND | ND | ND |

| 9d | H | COOH | H | 3-OH-4-OMe | >25 | >25 | ND | ND | ND |

| 9e | H | COOH | H | 3-OEt-4-OH | 22.63 ± 2.17 | >25 | ND | ND | ND |

| 9f | H | COOH | H | 3,4-methylendioxy | 15.75 ± 0.88 | >25 | ND | ND | ND |

| 9g | H | COOH | H | 3,4,5-triOMe | >25 | >25 | ND | ND | ND |

| 9h | H | COOH | H | 3,5-diOMe-4-OH | >25 | >25 | ND | ND | ND |

| 10a | H | Ph | H | 3,4-diOMe | 23.32 ± 2.37 | >25 | ND | ND | ND |

| 10b | H | Ph | H | 2,4-diOMe | >25 | >25 | ND | ND | ND |

| 10c | H | Ph | H | 3-OMe-4-OH | 5.50 ± 0.22* | 10.59 ± 1.38 | 15.79 ± 0.28 | 2.87 | 1.49 |

| 10d | H | Ph | H | 3-OH-4-OMe | 3.29 ± 0.18* | 6.74 ± 0.26* | 8.39 ± 0.12 | 2.55 | 1.25 |

| 10e | H | Ph | H | 3-OEt-4-OH | 6.14 ± 0.33 | 13.47 ± 1.53 | ND | ND | ND |

| 10f | H | Ph | H | 3,4-methylendioxy | 22.03 ± 3.24 | >25 | ND | ND | ND |

| 10g | H | Ph | H | 3,4,5-triOMe | 14.29 ± 0.37 | >25 | ND | ND | ND |

| 10h | H | Ph | H | 3,5-diOMe-4-OH | 4.06 ± 0.02* | 4.98 ± 0.09* | 10.19 ± 0.20 | 2.51 | 2.05 |

| curcumin | 20.65 ± 0.80 | 23.45 ± 7.27 | >25 | 1.72 | 1.51 | ||||

| paclitaxel | 8.79 ± 0.96 | 12.00 ± 0.56 | 0.73 ± 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.06 | ||||

Half-maximal inhibitory concentrations, after being treated with compounds for 72 h, were represented in mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three individual experiments with p < 0.05 (*) when compared to paclitaxel.

Human breast cancer cell line.

Human liver cancer cell line.

Normal porcine kidney cell line.

ND—not determined.

The SI of each MAC was calculated by dividing the corresponding IC50 average value of the MAC on the normal cell line by that on each cancer cell line.

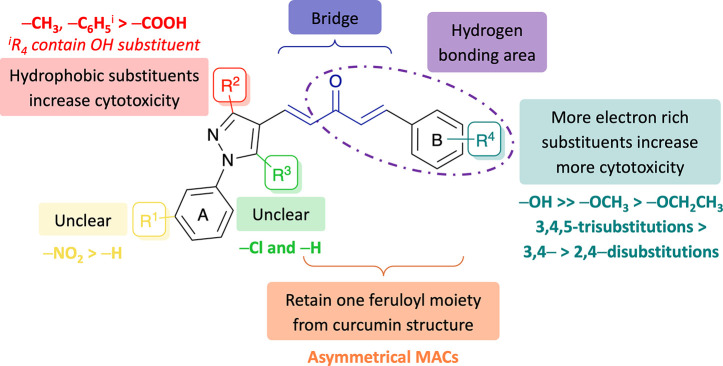

From cytotoxicity analysis of the synthesized MACs carrying diversified substituents on the 1H-pyrazole and ring B, the impact of substitution was intriguing, and the following conclusions had been drawn from the structure–activity relationship analysis of these compounds (Figure 5).

-

(a)

The number of electron-donating substituents on ring B should be as high as possible, as could be seen in potential 3,4,5-trisubstituted compounds such as 7g, 7h, 8g, 8h, and 10h. If there are two substituents on ring B, the 3,4-disubstitution would be more effective than the 2,4-disubstitution, except for 3,4-methylenedioxy. In most cases, compounds replacing an alkoxy with a hydroxy group on ring B showed more cytotoxicity, and when comparing different alkoxy groups, an ethoxy group showed less effectiveness on cytotoxicity than that of a methoxy one.

-

(b)

The presence of hydrophobic groups (1-phenyl and 3-methyl/phenyl) on 1H-pyrazole was attributed to superior cytotoxicity. If the substituents on 1H-pyrazole are 1,3-diphenyl, the substituents on ring B should include hydroxy groups such as 3-hydroxy (e.g., 7d and 10d) or 4-hydroxy (e.g., 7c, 7h, 8h, 10c, or 10h) to ensure the hydrophilic–hydrophobic balance.

-

(c)

The effects of the 3-nitro group on ring A and 5-chloro group on 1H-pyrazole to cytotoxicities were unclear.

Figure 5.

Structure–activity relationship of MACs fused with 1-aryl-1H-pyrazole for increased anticancer potency based on cytotoxic studies.

From the careful analysis above, the combined result indicated that nine compounds, including 7c, 7d, 7h, 8a, 8g, 8h, 10c, 10d, and 10h, exhibited the strongest cell growth inhibition against two selected cell lines. For further evaluation of their selectivity toward cancer cells, these compounds were also tested on a normal porcine kidney cell line (LLC-PK1), and the selective index (SI) on each cancer cell line showed that compound 8h was the most selective on MDA-MB-231 and HepG2, followed by compounds 7h, 8a, and 10h (Table 1). In addition, other compounds such as 7d, 10c, and 10d also showed higher selectivity on MDA-MB-231 and HepG2 than the noncancerous ones. Importantly, the highly selective compounds showed more selectivity than paclitaxel on two cancer cell lines compared to the normal one, which suggested that these compounds could have lower toxicity on normal cells, thereby probably safer than paclitaxel. Consequently, compounds 7d, 7h, 8a, 8h, 10c, 10d, and 10h were the most potent compounds in this study due to their promising cytotoxicity and were selected to further investigate their effects at the cellular and molecular levels.

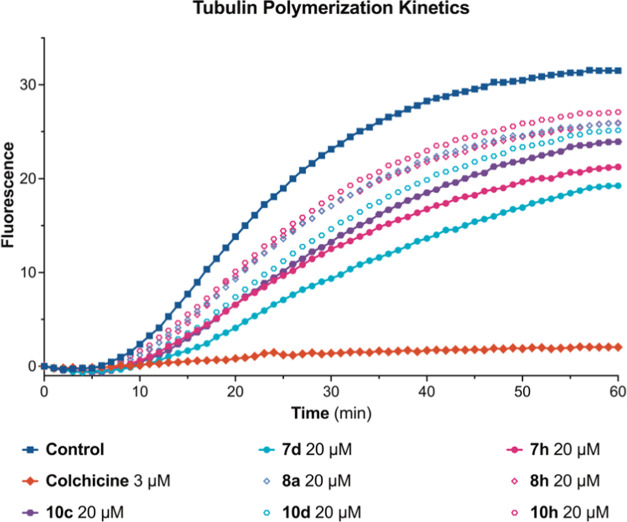

2.2.2. In Vitro Tubulin Polymerization Inhibitory Activity

The microtubule cytoskeleton plays pivotal roles in several biological functions, ranging from intracellular trafficking and positioning of cellular components in interphase and the formation of the mitotic spindle during cell division to the establishment and maintenance of cell morphology and cell motility.59,60 Previously, several MACs fused with heterocyclics were reported for inhibitory activities of microtubule polymerization,21,22,61 while others possessing enone moieties such as 4′-methoxy-2-styrylchromone62 and 5-(indol-3-yl)-1-phenyl penta-2,4-dien-1-one63 could stabilize microtubules. In addition, chalcones, possessing enone moieties connecting two aryl or heteroaryl units that were structurally similar to the MACs, could induce microtubule polymerization64,65 or reversibly bind in the CBS to inhibit this process,66,67 which depended on the different structures of chalcones. Therefore, evaluating the effects of synthesized MACs on tubulin polymerization in a free-cell in vitro assay was crucial. The screening results of the selected compounds, including 7d, 7h, 8a, 8h, 10c, 10d, and 10h, for their effects on tubulin polymerization via a free-cell in vitro assay (Table 2, Figure 6) showed that compounds 7d, 7h, and 10c at 20.0 μM exhibited the highest microtubule-destabilizing activities, with the respective decreasing percentages in the control’s Vmax being 52.03 ± 0.65, 45.29 ± 0.81, and 40.76 ± 0.33%, respectively, while that of colchicine at 3.0 μM was 94.65 ± 0.97%. The effective inhibition of compounds 7d, 7h, and 10c against tubulin polymerization indicated that these MACs might target specific binding sites of tubulin, such as the CBS and act as microtubule-destabilizing agents to affect the microtubule dynamics.

Table 2. In Vitro Effects of Selected Compounds on Inhibitions of Tubulin Polymerization.

| compound | % inhibitiona | compound | % inhibitiona |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7d | 52.03 ± 0.65 | 10c | 40.76 ± 0.33 |

| 7h | 45.29 ± 0.81 | 10d | 35.48 ± 0.51 |

| 8a | 25.90 ± 0.33 | 10h | 25.73 ± 0.15 |

| 8h | 22.11 ± 0.84 | colchicineb | 94.65 ± 0.97 |

The final concentration of test compounds and DMSO in each reaction mixture were 20 μM and 1% (v/v), respectively. Data were reduced to Vmax, which is the maximum slope of the growth phase, then the Vmax data were converted into a change in percentage of the control’s Vmax and were represented as the mean ± SD of two individual experiments. The final concentration of DMSO in the reaction mixture of the control sample was 1% (v/v).

The final concentration of colchicine in the reaction mixture of the negative control sample was 3 μM, whereas that of DMSO was 0.138% (v/v).

Figure 6.

Effects of the selected compounds on microtubule dynamics. Polymerization of tubulin at 37 °C in the presence of colchicine (3 μM), the selected compounds (20 μM), and the control sample containing an equivalent amount of 1% (v/v) DMSO were monitored continuously by recording fluorescence, with the respective value of excitation and emission wavelength being 360 and 410 nm, over 60 min. The reaction was initiated by the addition of tubulin to a final concentration of 2.0 mg·mL–1.

Overall, the cell-free in vitro study indicated that the selected MACs showed significant inhibitions on microtubule assembly. On the other hand, regarding cytotoxic studies against breast cancer cells MDA-MB-231 and liver cancer cells HepG2, these MACs exhibited stronger cell growth inhibitions and higher selectivities against the former. In comparison to paclitaxel—a microtubule-targeting agent (MTA) widely employed for breast cancer treatment—among the initial nine candidates, compounds 7d, 7h, and 10c demonstrated strong cytotoxicity (IC50 3.64–5.61 μM) and roughly three times the selectivity (SI 2.87–3.55) toward MDA-MB-231, while exhibiting strong inhibition on tubulin polymerization (40.76–52.03%). Therefore, these compounds were chosen for further examination regarding their cellular effects on this line of breast cancer cells.

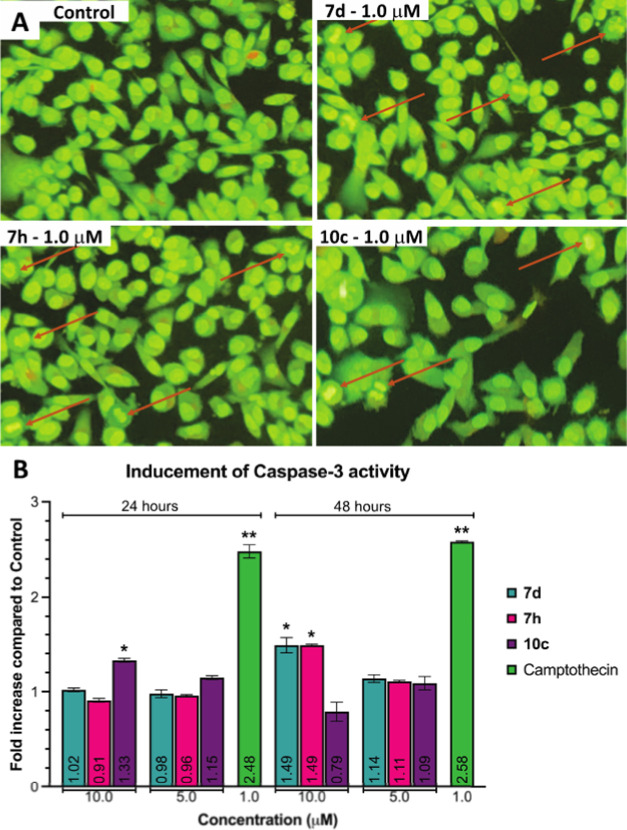

2.2.3. In Vitro Apoptosis-Inducing Activity

Many cytotoxic agents act by inducing apoptosis as their common mechanism. Therefore, it was interesting to examine the apoptosis-inducing effect of compounds 7d, 7h, and 10c on MDA-MB-231 cells by the AO/EB staining and the caspase-3 activity assay method.

2.2.3.1. Acridine Orange/Ethidium Bromide (AO/EB) Staining

The morphological changes induced by the compounds in MDA-MB-231 cells were further studied by employing the AO/EB staining technique.68 It could be observed that the control cells showed normal morphology with intact nucleus architecture and appeared green, whereas treated MDA-MB-231 cells demonstrated morphological changes, which were the characteristic features of apoptotic cells such as cytoplasmic shrinkage, nucleus condensation, and cell membrane blebbing at 1.0 μM of the selected potential compounds (Figure 7A). This confirmed that these potential compounds could induce programmed cell death in MDA-MB-231 cells.

Figure 7.

(A) Morphological changes in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with and without compounds 7d, 7h, or 10c for 24 h. Red arrows indicated compromised cells with early signs of apoptosis such as condensed chromatins, horseshoe-shaped nucleus, and nucleus fragmentation. (B) Enhancements of caspase-3 activity of 7d, 7h, and 10c in MDA-MB-231 cells for 24 and 48 h. Data were represented as the mean ± SD of three individual experiments with p < 0.05 (*) and p < 0.01 (**) when compared to control.

2.2.3.2. Caspase-3 Activity Assay

Caspase-3, along with caspase-6 and 7—highly conserved cysteine proteases—carry out the mass proteolysis that leads to apoptosis.69 To quantify the apoptosis-inducing ability in MDA-MB-231 cells, the colorimetric-based caspase-3 assay was employed to determine the increase in caspase-3 activity between the apoptotic sample and the untreated control. After treating the selected compounds for 24 and 48 h, results from analyzing cell lysates (Figure 7B) exhibited that, while camptothecin activated caspase-3 at 2.48 and 2.58 folds at 1.0 μM for two respective times, only compound 10c at 10.0 μM exhibited a 1.33-fold increase in caspase-3 activity in MDA-MB-231 cells after 24 h. Meanwhile, after 48 h, compounds 7d and 7h at 10.0 μM could induce caspase-3 activity that was 1.49 times higher than the control cells. This observation suggested that these compounds could induce apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells via the increase in caspase-3 activity.

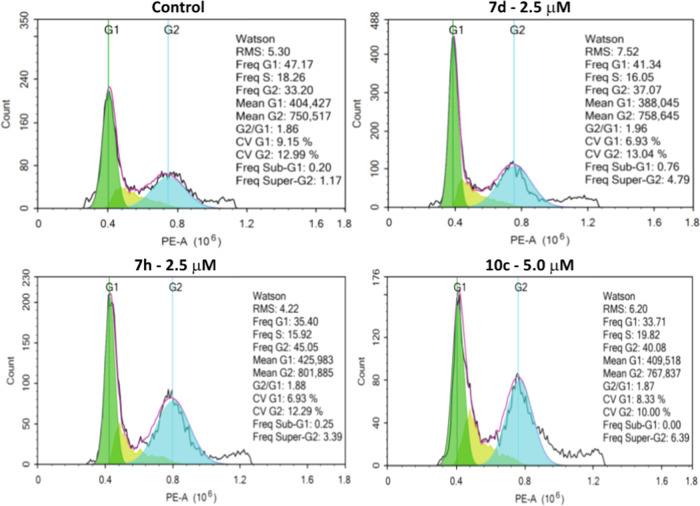

2.2.4. Cell Cycle Analysis

Cytotoxic agents usually alter the regulation of the cell cycle, resulting in the arrest of cell division in various phases, thereby preventing the growth and proliferation of cancer cells. The screening results revealed that 7d, 7h, and 10c could exhibit significant antiproliferative activity on MDA-MB-231 cells and could inhibit tubulin polymerization. Therefore, the influences of selected MACs on the MDA-MB-231 cell cycle were determined by flow cytometry analysis of a population of cells stained with propidium iodide (PI).70 Regarding the G2/M population, while there was a slight increase to 37.07% in the case of 7d at 2.5 μM, the treatment with 7h at 2.5 μM and 10c at 5.0 μM displayed higher values at 45.05 and 40.08%, respectively, compared to the control (33.20%), pointing out that compounds 7d, 7h, and 10c could result in G2/M cell cycle arrest in MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 8). This observation could be attributed to their inhibitory effects on the assembly of microtubules to form the mitotic spindle, which could prevent cells at the end of the G2 phase from entering the beginning of the M phase, hence increasing the proportion of the G2/M cell population.

Figure 8.

Effect of compounds 7d, 7h, and 10c on cell cycle of MDA-MB-231 cells. Cells were treated with these selected compounds for 24 h followed by the analysis of cell cycle distribution using the PI staining method. All assays were conducted in triplicate.

2.3. In Silico Molecular Modeling

2.3.1. Prediction of Pharmacokinetic and Toxicity Profiles

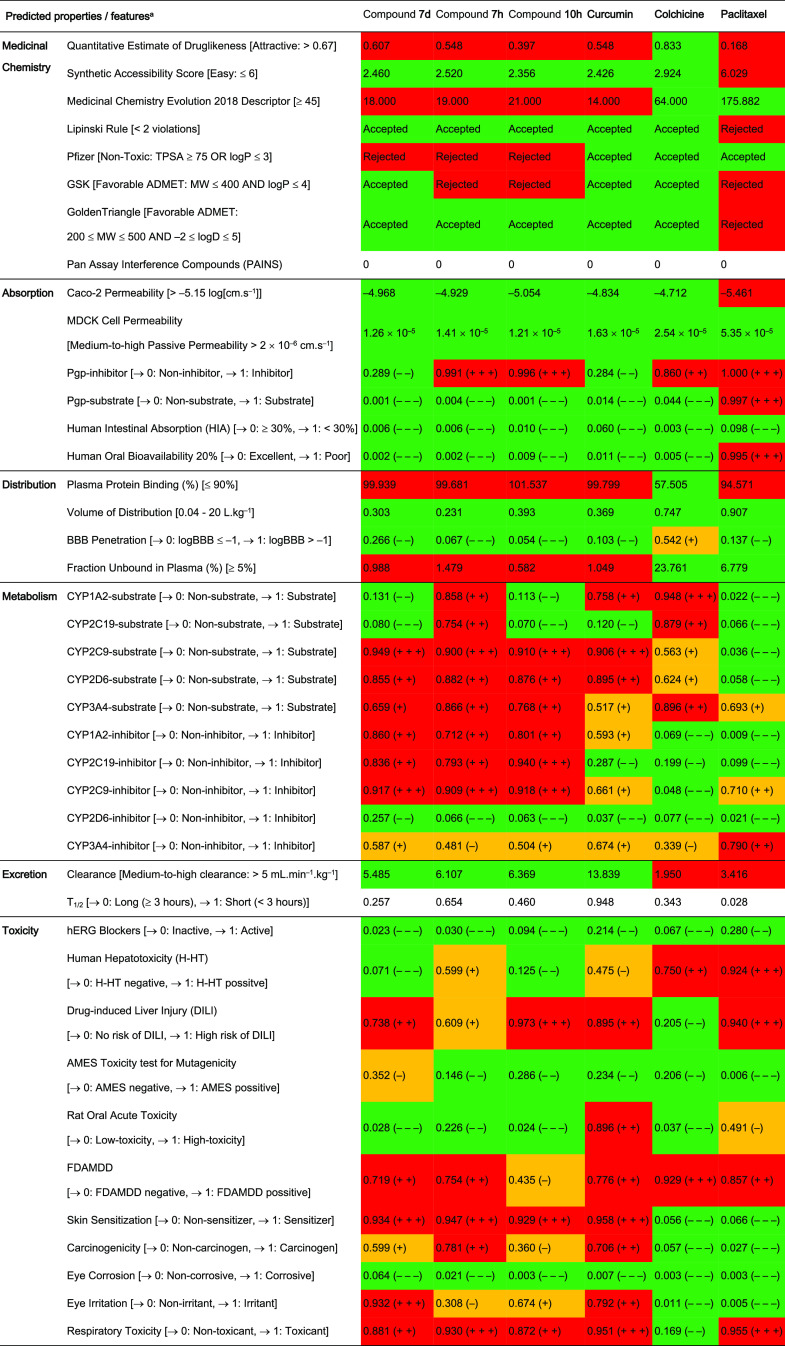

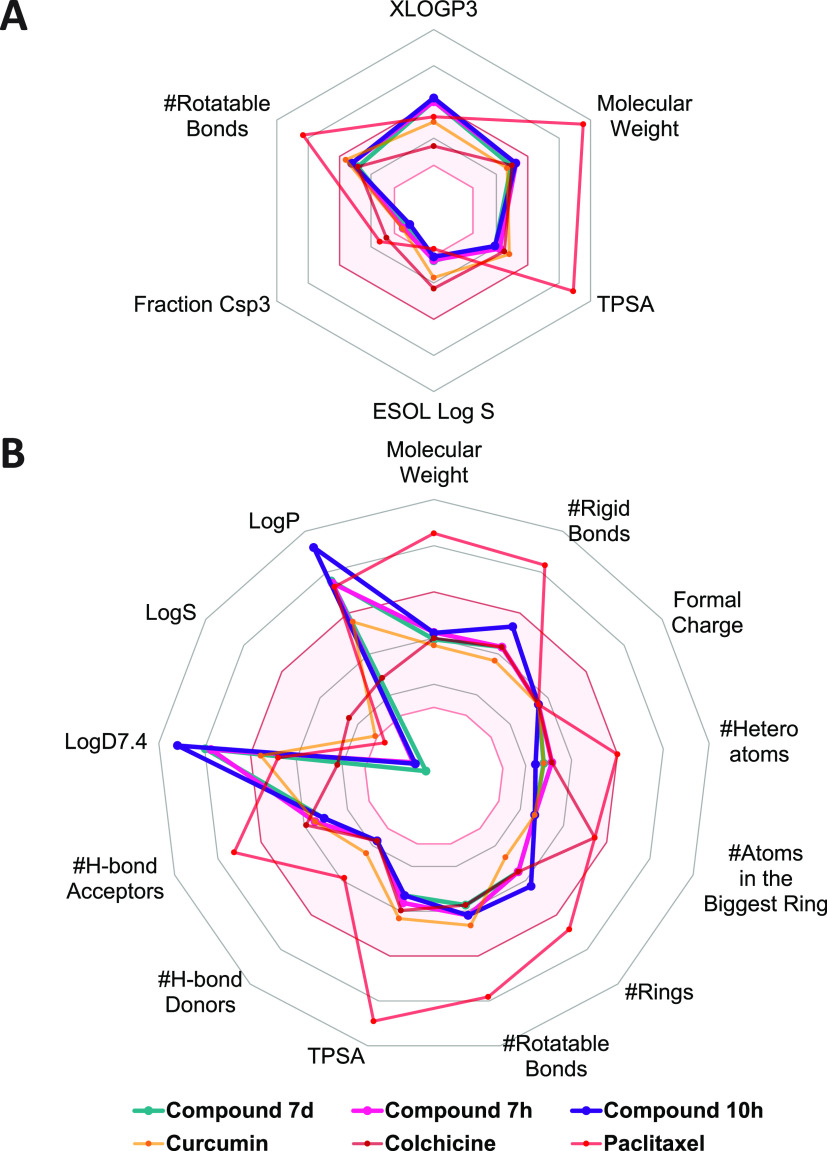

Pharmacokinetics including the absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and the toxicity (ADMET) profile of compounds 7d, 7h, and 10c were predicted by ADMETlab2.0 (https://admetmesh.scbdd.com/) and SwissADME (http://www.swissadme.ch/) online platforms,71,72 in comparison with curcumin, colchicine, and paclitaxel (Table 3, Figure 9, and Tables S1 and S2).

Table 3. ADMET Profile of Three Potent MACs Including Compounds 7d, 7h, and 10c, in Comparison with Curcumin, Colchicine, and Paclitaxela.

Data shown in [ ] represented optimal values or defined output values. Abbreviations: MW: molecular weight; TPSA: topological polar surface area; MDCK: Madin–Darby Canine kidney cells; Pgp: P-glycoprotein; BBB: blood–brain barrier; FFAMDD: the maximum recommended daily dose provides an estimate of the toxic dose threshold of chemicals in humans. The output value is within the range of 0–1. For the classification endpoints, the prediction probability values are transformed into six symbols that were divided into three empirical-based decision states visually represented with different colors, including (1) excellent/green: 0–0.1 (− – −) and 0.1–0.3 (− −), (2) medium/yellow: 0.3–0.5 (−) and 0.5–0.7 (+), and (3) red/poor: 0.7–0.9 (+ +) and 0.9–1.0 (+ + +). Full details of ADMET profiles predicted are shown in Tables S1 and S2.

Figure 9.

Physicochemical properties of compounds 7d, 7h, and 10c, in comparison with those of curcumin, colchicine, and paclitaxel. Data were retrieved from (A) SwissADME (http://www.swissadme.ch/) and (B) ADMETlab2.0 (https://admetmesh.scbdd.com/) platforms. The colored zone (pink) was the suitable physicochemical space for oral bioavailability. Lines and dots representing each compound are shown in the figure. Details of physicochemical properties are shown in Tables S1 and S2. TPSA: topological polar surface area.

Regarding the physicochemical descriptors, the results estimated from two platforms showed that compounds 7d, 7h, and 10c exhibited proper physical and chemical properties. All three compounds met the requirements of 5/6 properties of the SwissADME and 10/13 properties of the ADMETlab2.0 model, being comparable to curcumin—with 5/6 and 13/13 properties—and colchicine—with 6/6 and 13/13 properties—respectively. Paclitaxel exhibited fewer suitable physicochemical properties, meeting only 2/6 and 5/13 properties in optimal ranges according to the SwissADME and ADMETlab2.0 models, respectively. With relatively promising physicochemical properties, three potent MACs satisfied the Lipinski rule and the GoldenTriangle rule to attain favorable oral pharmacokinetic profiles.73,74 Moreover, the structure of these compounds did not contain the alerting substructures in PAINS and also showed a high possibility of easy synthesis of drug-like molecules.75,76 Nevertheless, the TPSA value of these MACs below 75 Å2 made them unsatisfactory to the Pfizer rule,77 while only compound 7d conformed to the GSK rule due to its molecular weight being below 400.78 These observations suggested that compounds 7d, 7h, and 10c have potential molecular structures with appropriate physicochemical properties; however, further developments based on their structures would be necessary to find out optimal lead compounds.

As for the prediction of pharmacokinetics, during the absorption phase, three potent MACs exhibited good passive permeabilities in both Caco-2 and MDCK cell line models. These permeabilities could be compared with those of curcumin, colchicine, and paclitaxel, and even higher than that of paclitaxel in the case of the Caco-2 model. Additionally, both online platforms predicted that paclitaxel could be a substrate of P-glycoprotein (Pgp), while the others could not. Therefore, the results showed an agreement between SwissADME and ADMETlab2.0 predictions in which potent MACs, curcumin, and colchicine demonstrated higher absorption through the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and also, higher oral bioavailabilities (F20% and F30%) than those of paclitaxel.

Next, in the distribution phase, only colchicine showed favorable percentages of plasma protein binding (PPB) form (≤90%) and free form (≥5%), contrary to the cases of curcumin and the analogues. The high percentage of PPB form over 90% of potent MACs, curcumin, and paclitaxel suggested that they might have a low therapeutic index. Interestingly, all compounds had proper volumes of distribution (0.04–20 L·kg–1) and most of them could not be able to penetrate the blood–brain barrier (BBB), which is advantageous as it could avoid side effects on the central nervous system (CNS).

Concerning the metabolism processes, all five popular human cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYPs) were predicted to involve in the metabolism of compound 7h and colchicine, especially enzymes CYP2C9 and CYP1A2. Similar to compound 7h, compounds 7d, 10c, and curcumin were also predicted to be the substrates and could be metabolized by CYP2D6, CYP3A4, and mainly CYP2C9. Meanwhile, CYP3A4 is the only enzyme among those mentioned having the ability to metabolize paclitaxel at a moderate level. On the other hand, three potent MACs exhibited considerable abilities to inhibit CYP1A2, CYP2C19, and CYP2C9, while CYP2C9 and CYP3A4 could be inhibited by paclitaxel.

In the elimination phase, curcumin and three potent analogues displayed medium-to-high clearances that were higher than those of colchicine and paclitaxel. When combining the results of clearance and volume of distribution, curcumin showed the lowest elimination half-life due to the highest clearance, whereas the figures for potent MACs were higher since they showed lower clearances but similar volumes of distribution to curcumin. Although there were improvements in retention time in the body compared to curcumin, all potent MACs were generally predicted to be eliminated more rapidly than colchicine and paclitaxel, suggesting the need for higher doses and/or shorter dosing intervals to maintain their therapeutic concentrations.

Finally, prediction of possible toxicities of three potent MACs compared with curcumin, colchicine, and paclitaxel was also conducted. The predicting results generally showed that all compounds might have low risks of causing hERG blockade, eye corrosion, and also mutagenicity in the AMES toxicity test, whereas their FDAMDD results could be positive, meaning that they could be toxic with a maximum daily dose below 0.011 mmol·(kg-bw)−1·day–1. Higher potentials for causing skin sensitization, carcinogenicity, and eye irritation could be seen in curcumin and three potent analogues than those of colchicine and paclitaxel. Additionally, except for colchicine, the remaining might have high respiratory toxicities and high risks of induction of liver injuries. Interestingly, three potent analogues were predicted to have fewer adverse hepatic effects than colchicine and paclitaxel, while possibly being less toxic in the oral acute toxicity study in rats than those of curcumin and paclitaxel, with LD50 values of over 500 mg·kg–1.

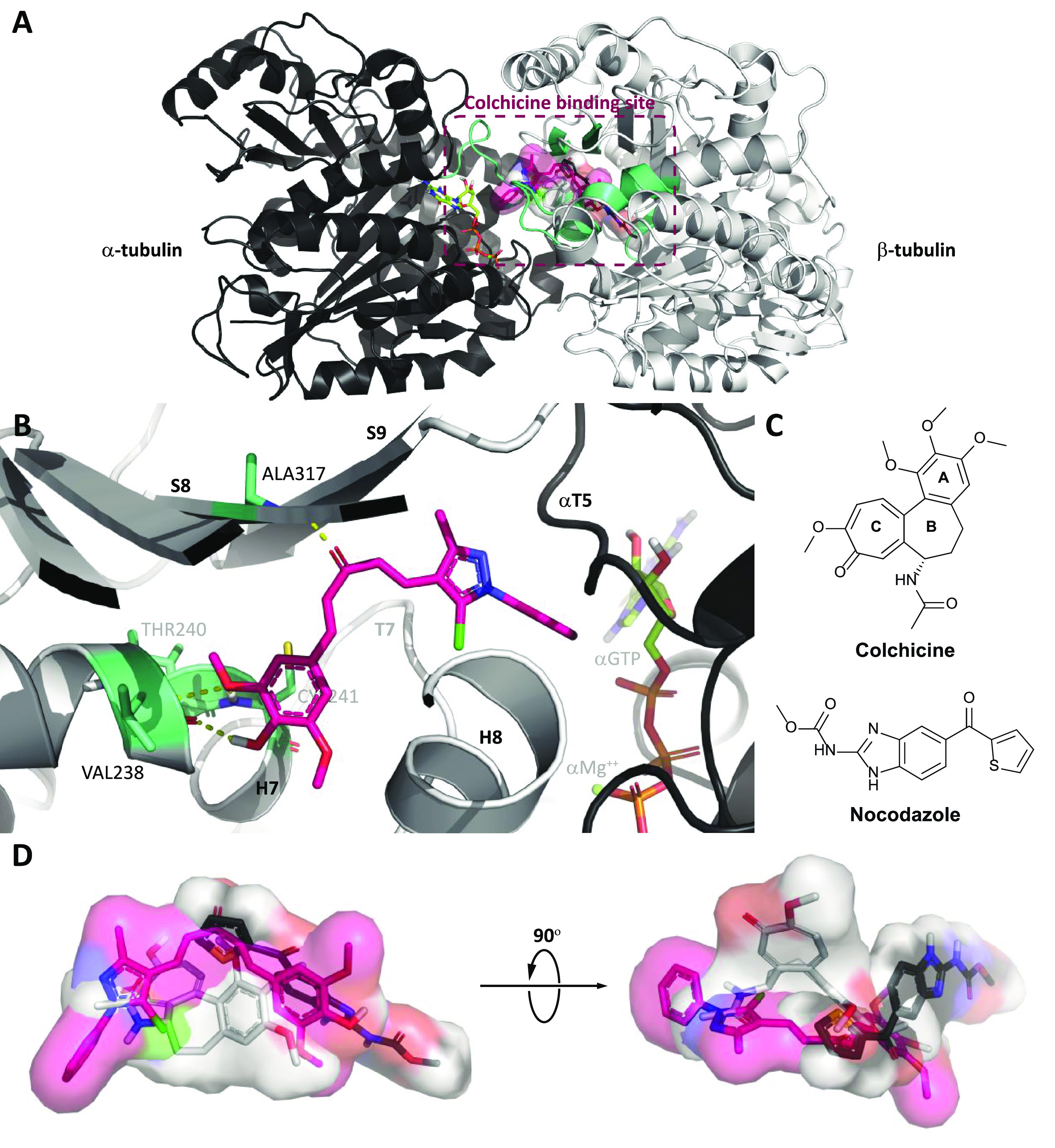

2.3.2. Molecular Docking

Molecular docking study was performed on the CBS of tubulin (PDB ID 4O2B)79 (Figure 10A) to gain a better understanding of the potency of the selected compounds (7d, 7h, and 10c) and to support the aforementioned biological results. The binding ability of these compounds with tubulin was representatively investigated through the binding mode of 7h. Compound 7h was selected for its potential cytotoxicity with higher selectivity against cancer cells, its effective inhibition of microtubule assembly, together with its promising cellular effects on breast cancer cells. As a preselection step for validating the docking protocols and parameters, the redocking step of the native ligand—colchicine—was carried out before compound 7h was docked. From the redocking result, the top docked pose of colchicine exhibited binding energy and root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) value, respectively, being at −9.46 kcal·mol–1 and 0.0487 nm (Figures S154, S156, and S158), signifying that the docking protocols and parameters were reliable for predicting and evaluating the binding mode of compound 7h.

Figure 10.

Results of molecular docking of compound 7h into the CBS. (A) Overall view of α,β-tubulin (shown in black and white cartoon representation) bound with compound 7h (shown in sticks inside the ligand surface) inside the CBS established by secondary structures (shown in green–cyan cartoon) at the α,β-tubulin interface. (B) Close-up view of interactions between compound 7h (shown in pink sticks) with several labeled residues (shown in green–cyan sticks) in the CBS. (C) Molecular structures of colchicine and nocodazole. (D) Superimposition of colchicine and nocodazole (shown in white and black sticks, respectively) with the top pose of compound 7h (shown in pink sticks). The αGTP molecule (shown in limon sticks) and ion αMg++ (shown in the lime–green sphere) were also labeled. Hydrogen bonds are highlighted as dashed yellow lines. Heteroatoms are colored blue (nitrogen), red (oxygen), orange (phosphorus), yellow (sulfur), or green (chlorine).

Regarding compound 7h, the best-docked pose of this compound showed that its ring B could enter the hydrophobic pocket inside β-tubulin shaped by H7 helix, S6, and S8 strands, hence forming several hydrophobic contacts with GLY237-THR239, CYS241 (H7 helix), ALA316-ILE318 (S8 strand), and TYR202 (S6 strand), together with three canonical hydrogen bonds between hydroxy/methoxy groups of ring B and backbone atoms of VAL238 (0.211 nm), THR240 (0.276 nm), and CYS241 (0.206 nm). Meanwhile, the 1H-pyrazole of the top pose is located at the interface and navigated ring A to the space between αT5 and T7 loops, while its carbonyl group projected toward the S8 strand to form a canonical hydrogen bond with ALA317 (0.210 nm) (Figure 10B). These interactions increased the stability of compound 7h in the CBS, resulting in the significant binding energy of this compound, at −10.08 kcal·mol–1 (Figures S155, S157, and Table S3). With the insights into the binding mode of compound 7h, it could be observed that this compound could bind well at the CBS and could occupy the same position as several common colchicine-binding site inhibitors (CBSIs). Interestingly, from the best of our knowledge, the CBS could be subdivided into the main zone in the center (zone 2) and two additional zones located on either sides of the main zone (zones 1 and 3),80 and none of CBSIs occupying three zones simultaneously have been described so far.81 The superimposition of the top docked poses of compound 7h with two well-known CBSIs, colchicine82,83 and nocodazole (PDB ID 5CA1)79,84 (Figure 10C,D), demonstrated that the binding ability of these MACs could spread in a wider space in the CBS, which were more accessible to the α-tubulin surface (zone 1) than nocodazole and were concurrently buried deeper inside β-tubulin (zone 3) than colchicine.

3. Conclusions

In conclusion, MACs fused with 1-aryl-1H-pyrazole, especially asymmetric MACs, described in our present study demonstrated the potential anticancer activities and indicated exciting possibilities of developing new cancer therapeutics via their structural modifications. Although the most potent MACs had several benefits in addition to potential drawbacks in terms of biological activities and ADMET properties when compared with well-known drugs, we expect that our study could serve as a basis for the design of synthetic compounds that would appear promising for other in vitro or in vivo anticancer activity studies as tubulin polymerization inhibitors in the future.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. General

All of the chemicals, reagents, starting materials, and solvents were procured from commercial suppliers such as Acros, Fisher Scientific (Hampton, NH), AK Scientific (Union City, CA), Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), and Gibco-Invitrogen (Waltham, MA) and were used without further purification. Analytical thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed using Merck precoated silica gel 60 F254 (8.0–12.0 μm) aluminum plates (0.2 mm), while column chromatography was conducted using silica gel 60 (40.0–63.0 μm) (Kenilworth, NJ). Visualization of spots on TLC plates was achieved by UV light (254 and 365 nm). The purity of all compounds was detected by a Shimadzu Prominence-i LC2030C 3D (Kyoto, Japan) (column: Gemini C18 5 μm × 4.6 mm × 250 mm, flow rate: 1.0 mL·min–1, UV wavelength: 430 nm, eluent/methanol water from 70:30 to 90:10). Melting points were checked by the open capillary tube method using a Sanyo–Gallenkamp melting point apparatus (Hampton, NH) and they are uncorrected. IR spectra for all of the compounds were recorded on an IRAffinity-1S Shimadzu instrument (Kyoto, Japan) using the ATR technique. 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Advance II Instrument (Billerica, MA) operated at 500 and 125 MHz, respectively. HR-MS spectra were performed by a Shimadzu LC-20A system (Kyoto, Japan) with the LCMS-IT-TOF detector, or by the Agilent LC 6545 system (Santa Clara, CA) with the LCMS Q-TOF detector. The human breast (MDA-MB-231), human liver (HepG2), and porcine kidney cell line (LLC-PK1) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA).

4.2. Synthetic Procedure

Initially, 1H-pyrazole-4-carbaldehyde derivatives (4a–4d) were synthesized through 2–3 consecutive steps, which were described before,85−87 starting from (i) phenyl hydrazine derivatives, and (ii) methyl acetoacetate, ethyl pyruvate, or acetophenone, to afford 1H-pyrazol-5(4H)-ones (3a and 3b)86 or hydrazones (3c and 3d).85 Subsequently, via the Vilsmeier–Haack reaction, 3a and 3b underwent a formylation–chlorination process to obtain intermediates 4a and 4b,86 whereas 3c and 3d underwent a cyclization–formylation process to obtain intermediates 4c′ and 4d,85 respectively. The intermediate 3c was synthesized by hydrolysis of ester 4c′ in the presence of aqueous alkali, followed by acidification with aqueous acid.87 The other core structures, 4-phenylbut-3-en-2-one derivatives (6a–6h), were prepared by KOH-catalyzed condensation of benzaldehyde derivatives with acetone. Finally, KOH-catalyzed condensation between 4a–4d and 6a–6h furnished the target asymmetric MACs 7a–10h (Scheme 1).88 Synthetic compounds were characterized by spectroscopic techniques such as IR, HR-MS, 1H-, and 13C-NMR.

4.2.1. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Asymmetric MACs 7a–10h

A mixture of a 4-phenylbut-3-en-2-one derivative (6a–6h, 1.05 mmol) and 4% KOH solution in ethanol or saturated KOH solution in tert-butanol (5 mL) was stirred at 0–5 °C for 10–15 min. To this mixture, 1H-pyrazole-4-carbaldehyde (4a–4d, 1.00 mmol) was added in small portions. The reaction mixture was carried out at room temperature, or 60 °C if 6c or 6e was used, for 4–24 h. Upon completion, the mixture was added with cold water (10–15 mL), then the excess amount of KOH was either neutralized or acidified to pH = 2–4 if 4c was used, by a concentrated solution of HCl. The precipitate was filtered, then dried, and purified by recrystallization using solvents such as ethanol, ethyl acetate, acetone, and the ethyl acetate–ethanol (1:1) mixture, or by column chromatography using the n-hexane–ethyl acetate (3:1) mixture to obtain the corresponding asymmetric MACs. Among asymmetric MACs synthesized, 7a, 7c, 7g, 10a, and 10g were described before in the literature.55,56

4.2.1.1. (1E,4E)-1-(5-Chloro-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-5-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)penta-1,4-dien-3-one (7a)56

Yellow solid (171.7 mg, 42%); mp 137–140 °C; TLC (Rf, dichloromethane–methanol 95:5) 0.67; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 2938 (ArH), 2839 (Me), 1655 (C=O), 1589 (C=C), 772 (C–Cl); HPLC purity 99.410% (r.t. 11.589 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 7.67 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.61–7.50 (5H, m, ArH), 7.55 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.42 (1H, d, J = 1.0 Hz, ArH), 7.34 (1H, dd, J = 1.5, 8.5 Hz, ArH), 7.23 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.14 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.02 (1H, d, J = 8.5 Hz, ArH), 3.84 (3H, s, OMe), 3.81 (3H, s, OMe), 2.49 (3H, s, Me); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 187.6, 151.2, 149.4, 149.0, 142.9, 137.2, 130.4, 129.3, 128.8, 128.0, 127.4, 125.0, 124.8, 124.1, 123.4, 113.6, 111.6, 110.7, 55.6, 55.6, 14.0; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C23H21ClN2O3 [M + H]+ calcd 409.1320, found 409.1297.

4.2.1.2. (1E,4E)-1-(5-Chloro-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-5-(2,4-dimethoxyphenyl)penta-1,4-dien-3-one (7b)

Yellow solid (175.9 mg, 43%); mp 120–123 °C; TLC (Rf, dichloromethane–methanol 95:5) 0.70; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 2940 (ArH), 2843 (Me), 1667 (C=O), 1607 (C=C), 754 (C–Cl); HPLC purity 97.838% (r.t. 19.236 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 7.90 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.77 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.59–7.51 (5H, m, ArH), 7.53 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.23 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.06 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 6.64–6.61 (2H, m, ArH), 3.89 (3H, s, OMe), 3.84 (3H, s, OMe), 2.47 (3H, s, Me); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 187.7 163.0, 159.9, 149.4, 137.2, 137.2, 130.1, 129.9, 129.3, 128.8, 127.9, 125.5, 125.0, 123.3, 115.8, 113.6, 106.3, 98.3, 55.8, 55.5, 13.9; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C23H21ClN2O3 [M + H]+ calcd 409.1320, found 409.1285.

4.2.1.3. (1E,4E)-1-(5-Chloro-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-5-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)penta-1,4-dien-3-one (7c)56

Yellow solid (149.8 mg, 38%); mp 133–136 °C; TLC (Rf, dichloromethane–methanol 95:5) 0.54; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 3107 (OH), 2931 (ArH), 2835 (Me), 1634 (C=O), 1593 (C=C), 762 (C–Cl); HPLC purity 98.487% (r.t. 8.133 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.66 (1H, s, OH), 7.64 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.61–7.52 (5H, m, ArH), 7.54 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.39 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz, ArH), 7.23 (1H, dd, J = 1.5, 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.17 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.13 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 6.83 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 3.85 (3H, s, OMe), 2.48 (3H, s, Me); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 187.5, 149.6, 149.4, 148.0, 143.4, 137.2, 130.2, 129.3, 128.8, 128.0, 126.1, 125.0, 124.9, 123.6, 123.2, 115.6, 113.6, 111.6, 55.7, 14.0; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C22H19ClN2O3 [M + H]+ calcd 395.1163, found 395.1113.

4.2.1.4. (1E,4E)-1-(5-Chloro-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-5-(3-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)penta-1,4-dien-3-one (7d)

Yellow solid (177.7 mg, 45%); mp 190–193 °C; TLC (Rf, dichloromethane–methanol 95:5) 0.49; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 3310 (OH), 3003 (ArH), 2843 (Me), 1641 (C=O), 1560 (C=C), 765 (C–Cl); HPLC purity 98.152% (r.t. 8.056 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.17 (1H, s, OH), 7.59 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.61–7.52 (5H, m, ArH), 7.54 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.23–7.21 (2H, m, ArH), 7.12 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.11 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 6.99 (1H, d, J = 8.5 Hz, ArH), 3.83 (3H, s, OMe), 2.48 (3H, s, Me); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 187.6, 150.2, 149.4, 146.7, 142.9, 137.2, 130.3, 129.3, 128.8, 128.0, 127.5, 125.1, 125.0, 123.7, 121.8, 114.4, 113.6, 112.0, 55.6, 14.0; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C22H19ClN2O3 [M + H]+ calcd 395.1163, found 395.1089.

4.2.1.5. (1E,4E)-1-(5-Chloro-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-5-(4-hydroxy-3-ethoxyphenyl)penta-1,4-dien-3-one (7e)

Yellow solid (167.6 mg, 41%); mp 155–158 °C; TLC (Rf, dichloromethane–methanol 95:5) 0.62; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 3134 (OH), 2982 (ArH), 2889 (Me), 1636 (C=O), 1557 (C=C), 773 (C–Cl); HPLC purity 99.372% (r.t. 11.264 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.58 (1H, s, OH), 7.63 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.61–7.50 (5H, m, ArH), 7.53 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.38 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz, ArH), 7.22 (1H, dd, J = 1.5, 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.16 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.12 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 6.84 (1H, d, J = 8.5 Hz, ArH), 4.11 (2H, q, J = 7.0 Hz, CH2), 2.48 (3H, s, Me), 1.36 (3H, t, J = 7.0 Hz, Me); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 187.5, 149.9, 149.4, 147.1, 143.4, 137.2, 130.1, 129.3, 128.8, 127.9, 126.2, 125.0, 124.9, 123.6, 123.2, 115.7, 113.6, 113.0, 64.0, 14.7, 14.0; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C23H21ClN2O3 [M + H]+ calcd 409.1320, found 409.1276.

4.2.1.6. (1E,4E)-1-(Benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-5-(5-chloro-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)penta-1,4-dien-3-one (7f)

Yellow solid (176.8 mg, 45%); mp 147–150 °C; TLC (Rf, n-hexane–ethyl acetate 2:1) 0.49; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 2924 (ArH), 2799 (Me), 1655 (C=O), 1597 (C=C), 750 (C–Cl); HPLC purity 98.785% (r.t. 17.370 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 7.63 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.60–7.52 (5H, m, ArH), 7.56 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.49 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz, ArH), 7.28 (1H, dd, J = 1.0, 10.0 Hz, ArH), 7.26 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.09 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 6.99 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 6.10 (2H, s, CH2), 2.48 (3H, s, Me); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 187.7, 149.5, 149.4, 148.1, 142.5, 137.2, 130.6, 129.3, 129.1, 128.8, 128.0, 125.5, 125.1, 125.0, 124.0, 113.6, 108.5, 106.7, 101.6, 13.9; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C22H17ClN2O3 [M + H]+ calcd 393.1007, found 393.0986.

4.2.1.7. (1E,4E)-1-(5-Chloro-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-5-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)penta-1,4-dien-3-one (7g)56

Yellow solid (162.4 mg, 37%); mp 142–144 °C; TLC (Rf, dichloromethane–methanol 95:5) 0.59; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 2947 (ArH), 2833 (Me), 1620 (C=O), 1579 (C=C), 758 (C–Cl); HPLC purity 97.993% (r.t. 12.453 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 7.67 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.59–7.52 (6H, m, ArH), 7.30 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.17–7.14 (3H, m, −CH= and ArH), 3.85 (6H, s, OMe), 3.72 (3H, s, OMe), 2.49 (3H, s, Me); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 187.6, 153.1, 149.5, 142.9, 139.7, 137.2, 130.7, 130.2, 129.3, 128.8, 128.1, 125.7, 125.0, 124.5, 113.6, 106.3, 60.1, 56.1, 14.0; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C24H23ClN2O4 [M + H]+ calcd 439.1426, found 439.1475.

4.2.1.8. (1E,4E)-1-(5-Chloro-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-5-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)penta-1,4-dien-3-one (7h)

Yellow solid (208.2 mg, 49%); mp 158–160 °C; TLC (Rf, dichloromethane–methanol 95:5) 0.47; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 3319 (OH), 2959 (ArH), 2843 (Me), 1645 (C=O), 1593 (C=C), 1107 (C–O–C), 762 (C–Cl); HPLC purity 98.763% (r.t. 7.458 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.04 (1H, s, OH), 7.65 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.61–7.50 (6H, m, ArH), 7.20 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.14 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.12 (2H, s, −CH= and ArH), 3.84 (6H, s, OMe), 2.49 (3H, s, Me); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 187.5, 149.4, 148.1, 143.7, 138.7, 137.2, 130.2, 129.3, 128.8, 128.0, 125.0, 125.0, 124.8, 123.7, 113.6, 106.7, 56.1, 14.0; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C23H21ClN2O4 [M – H]− calcd 423.1112, found 423.1095.

4.2.1.9. (1E,4E)-1-[5-Chloro-3-methyl-1-(3-nitrophenyl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl]-5-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)penta-1,4-dien-3-one (8a)

Yellow solid (190.6 mg, 42%); mp 181–183 °C; TLC (Rf, n-hexane–ethyl acetate 1:1) 0.46; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 2938 (ArH), 2839 (Me), 1657 (C=O), 1589 (C=C), 1539 and 1348 (NO2), 804 (C–Cl); HPLC purity 98.270% (r.t. 12.563 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 8.45 (1H, t, J = 2.0 Hz, ArH), 8.33 (1H, dd, J = 1.0, 2.5, 8.5 Hz, ArH), 8.13 (1H, dd, J = 1.0, 2.0, 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.88 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.66 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.54 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.39 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz, ArH), 7.33 (1H, dd, J = 2.0, 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.17 (2H, d, J = 16. Hz, −CH=), 7.03 (1H, d, J = 8.5 Hz, ArH), 3.86 (3H, s, OMe), 3.84 (3H, s, OMe), 2.52 (3H, s, Me); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 187.4, 151.2, 150.0, 149.0, 147.9, 142.6. 137.7, 130.5, 130.2, 129.5, 127.8, 125.4, 123.9, 122.8, 122.7, 118.9, 114.3, 112.0, 111.5, 55.7, 55.5, 13.4; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C23H20ClN3O5 [M + H]+ calcd 454.1164, found 454.1165.

4.2.1.10. (1E,4E)-1-[5-Chloro-3-methyl-1-(3-nitrophenyl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl]-5-(2,4-dimethoxyphenyl)penta-1,4-dien-3-one (8b)

Yellow solid (199.7 mg, 44%); mp 183–185 °C; TLC (Rf, n-hexane–ethyl acetate 1:1) 0.56; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 2930 (ArH), 2839 (Me), 1668 (C=O), 1607 (C=C), 1537 and 1348 (NO2), 793 (C–Cl); HPLC purity 98.082% (r.t. 19.275 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 8.45 (1H, t, J = 2.0 Hz, ArH), 8.35 (1H, dd, J = 1.0, 2.0, 8.5 Hz, ArH), 8.15 (1H, dd, J = 1.0, 2.0, 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.90 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.88 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.78 (1H, d, J = 8.5 Hz, ArH), 7.53 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.24 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.10 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 6.66–6.56 (2H, m, ArH), 3.90 (3H, s, OMe), 3.84 (3H, s, OMe), 2.52 (3H, s, Me); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 187.4, 162.7, 159.6, 149.8, 147.9, 137.7, 137.2, 130.4, 130.1, 129.6, 129.1, 127.5, 126.0, 123.2, 122.6, 118.8, 115.8, 114.3, 106.2, 98.3, 55.5, 55.1, 13.3; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C23H20ClN3O5 [M + H]+ calcd 454.1164, found 454.1160.

4.2.1.11. (1E,4E)-1-[5-Chloro-3-methyl-1-(3-nitrophenyl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl]-5-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)penta-1,4-dien-3-one (8c)

Yellow solid (153.9 mg, 35%); mp 155–157 °C; TLC (Rf, n-hexane–ethyl acetate 1:1) 0.35; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 3536 (OH), 3101 (CH-pyrazole), 2924 (ArH), 2853 (Me), 1656 (C=O), 1593 (C=C), 1530 and 1346 (NO2), 1277 (C–O–C), 802 (C–Cl); HPLC purity 98.592% (r.t. 8.817 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.68 (1H, s, OH), 8.46 (1H, t, J = 2.0 Hz, ArH), 8.35 (1H, dd, J = 2.0, 8.0 Hz, ArH), 8.15 (1H, dd, J = 2.0, 8.5 Hz, ArH), 7.89 (1H, t, J = 8.5 Hz, ArH), 7.65 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.53 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.40 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz, ArH), 7.24 (1H, dd, J = 2.0, 8.5 Hz, ArH), 7.17 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.16 (1H, d, J = 16.5 Hz, −CH=), 6.84 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 3.85 (3H, s, OMe), 2.52 (3H, s, Me); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 187.5, 150.2, 149.7, 148.0, 147.9, 143.5, 137.8, 130.9, 130.7, 129.7, 128.3, 126.1, 125.5, 123.6, 123.2, 123.1, 119.4, 115.6, 114.5, 111.6, 55.7, 14.0; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C22H18ClN3O5 [M + H]+ calcd 440.1014, found 440.1133.

4.2.1.12. (1E,4E)-1-[5-Chloro-3-methyl-1-(3-nitrophenyl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl]-5-(3-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)penta-1,4-dien-3-one (8d)

Yellow solid (299.1 mg, 68%); mp 171–173 °C; TLC (Rf, n-hexane–ethyl acetate 1:1) 0.38; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 3356 (OH), 3096 (CH-pyrazole), 2960 (ArH), 2839 (Me), 1645 (C=O), 1608 (C=C), 1522 and 1344 (NO2), 1103 (C–O–C), 800 (C–Cl); HPLC purity 99.287% (r.t. 8.606 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.18 (1H, s, OH), 8.45 (1H, t, J = 2.0 Hz, ArH), 8.34 (1H, dd, J = 1.5, 8.0 Hz, ArH), 8.14 (1H, dd, J = 1.5, 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.88 (1H, t, J = 8.5 Hz, ArH), 7.60 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.53 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.22–7.21 (2H, m, ArH), 7.15 (1H, d, J = 16.5 Hz, −CH=), 7.11 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 6.99 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 3.83 (3H, s, OMe), 2.51 (3H, s, Me); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 187.5, 150.3, 148.0, 146.7, 143.1, 137.8, 130.9, 130.5, 129.8, 128.3, 127.5, 125.6, 123.6, 123.1, 121.9, 119.2, 114.6, 114.4, 111.9, 55.6, 13.4; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C22H18ClN3O5 [M + H]+ calcd 440.1014, found 440.0916.

4.2.1.13. (1E,4E)-1-[5-Chloro-3-methyl-1-(3-nitrophenyl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl]-5-(4-hydroxy-3-ethoxyphenyl)penta-1,4-dien-3-one (8e)

Yellow solid (154.3 mg, 34%); mp 216–218 °C; TLC (Rf, n-hexane–ethyl acetate 1:1) 0.40; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 3370 (OH), 2924 (ArH), 2851 (Me), 1674 (C=O), 1599 (C=C), 153 and 1348 (NO2), 1275 (C–O–C), 806 (C–Cl); HPLC purity 98.558% (r.t. 12.464 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.60 (1H, s, OH), 8.45 (1H, t, J = 2.0 Hz, ArH), 8.34 (1H, dd, J = 2.0, 8.5 Hz, ArH), 8.14 (1H, dd, J = 2.0, 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.88 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.63 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz, −CH=), 7.52 (1H, d, J = 16.5 Hz, −CH=), 7.37 (1H, d, J = 1.5 Hz, ArH), 7.22 (1H, dd, J = 2.0, 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.15 (2H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 6.84 (1H, d, J = 8.5 Hz, ArH), 4.10 (2H, q, J = 7.0 Hz, CH2), 2.51 (3H, s, Me), 1.36 (3H, t, J = 7.0 Hz, Me); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 187.5, 150.2, 149.9, 148.0, 147.1, 143.5, 137.9, 130.9, 130.7, 129.7, 128.3, 126.1, 125.5, 123.6, 123.2, 123.1, 119.4, 115.7, 114.5, 113.0, 64.0, 14.7, 14.0; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C23H20ClN3O5 [M + H]+ calcd 454.1170, found 454.1163.

4.2.1.14. (1E,4E)-1-(Benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-5-(5-chloro-3-methyl-1-(3-nitrophenyl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)penta-1,4-dien-3-one (8f)

Yellow solid (183.9 mg, 42%); mp 178–181 °C; TLC (Rf, n-hexane–ethyl acetate 1:1) 0.71; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 2987 (ArH), 2922 (Me), 1653 (C=O), 1587 (C=C), 1531 and 1348 (NO2), 794 (C–Cl); HPLC purity 98.858% (r.t. 18.991 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 8.46 (1H, t, J = 2.0 Hz, ArH), 8.36 (1H, dd, J = 1.5, 8.0 Hz, ArH), 8,16 (1H, dd, J = 1.5, 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.89 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.65 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz, −CH=), 7.56 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.50 (1H, s, ArH), 7.29 (1H, dd, J = 1.0, 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.27 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.13 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.00 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 6.10 (2H, s, CH2), 2.52 (3H, s, Me); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 187.3, 149.9, 149.1, 147.9, 147.4, 142.1, 137.7, 130.5, 130.1, 129.6, 128.9, 127.7, 125.6, 124.6, 123.8, 122.6, 118.9, 114.3, 108.1, 106.5, 101.2, 13.3; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C22H16ClN3O5 [M + H]+ calcd 438.0851, found 438.0843.

4.2.1.15. (1E,4E)-1-(5-Chloro-3-methyl-1-(3-nitrophenyl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-5-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)penta-1,4-dien-3-one (8g)

Orange solid (217.8 mg, 45%); mp 125–127 °C; TLC (Rf, n-hexane–ethyl acetate 1:1) 0.57; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 3097 (CH-pyrazole), 2938 (ArH), 2839 (Me), 1653 (C=O), 1614 (C=C), 1530 and 1346 (NO2), 1279 (C–O–C), 802 (C–Cl); HPLC purity 98.868% (r.t. 14.841 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 8.46 (1H, t, J = 2.0 Hz, ArH), 8.35 (1H, dd, J = 1.5, 8.5 Hz, ArH), 8.15 (1H, dd, J = 2.0, 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.88 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.67 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz, −CH=), 7.56 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.30 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.18 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.14 (2H, s, ArH), 3.85 (6H, s, OMe), 3.72 (3H, s, OMe), 2.52 (3H, s, Me); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 187.6, 153.0, 150.3, 148.0, 143.1, 139.7, 137.8, 130.9, 130.7, 130.3, 130.1, 128.5, 125.6, 125.1, 123.2, 119.3, 114.4, 106.3, 60.1, 56.1, 14.0; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C24H22ClN3O6 [M + H]+ calcd 484.1276, found 484.1274.

4.2.1.16. (1E,4E)-1-(5-Chloro-3-methyl-1-(3-nitrophenyl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-5-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)penta-1,4-dien-3-one (8h)

Orange solid (84.6 mg, 18%); mp 215–217 °C; TLC (Rf, n-hexane–ethyl acetate 1:1) 0.31; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 3499 (OH), 2960 (CH-pyrazole), 2924 (ArH), 2851 (Me), 1645 (C=O), 1603 (C=C), 1531 and 1344 (NO2), 1103 (C–O–C), 804 (C–Cl); HPLC purity 98.509% (r.t. 8.707 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.05 (1H, s, OH), 8.46 (1H, s, ArH), 8.36 (1H, d, J = 8.5 Hz, ArH), 8,16 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.89 (1H, t, J = 8.5 Hz, ArH), 7.66 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.54 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.20 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz, −CH=), 7.18 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.12 (2H, s, ArH), 3.84 (6H, s, OMe), 2.53 (3H, s, Me); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 187.4, 150.3, 148.1, 148.0, 143.9, 138.8, 137.9, 130.9, 130.7, 129.7, 128.3, 125.4, 124.9, 123.6, 123.2, 119.3, 114.5, 106.7, 55.1, 14.0; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C23H20ClN3O6 [M + H]+ calcd 470.1120, found 470.1126.

4.2.1.17. 4-([(1E,4E)-5-(3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl)-3-oxopenta-1,4-dien-1-yl])-3-carboxy-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazole-4-yl (9a)

Yellow solid (141.8 mg, 35%); mp 238–241 °C; TLC (Rf, dichloromethane–methanol–acetic acid 96:6:3) 0.56; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 3130 (CH-pyrazole), 3067 (ArH), 2845 (Me), 1692 (C=O), 1651 (C=C), 1589 (C=N); HPLC purity 99.452% (r.t. 11.591 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 13.35 (1H, s, COOH), 9.30 (1H, s, CH-pyrazole), 8.07 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.93 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.74 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.59 (2H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.45 (1H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, ArH), 7.42 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.38 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz, ArH), 7.30 (1H, dd, J = 1.5, 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.05 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.03 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 3.84 (3H, s, OMe), 3.81 (3H, s, OMe); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 188.2, 163.1, 151.2, 149.0, 143.2, 143.1, 138.7, 132.0, 129.7, 128.6, 127.9, 127.4, 125.9, 124.6, 123.1, 121.7, 119.2, 111.7, 111.4, 55.6; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C23H20N2O5 [M + H]+ calcd 405.1445, found 405.1392.

4.2.1.18. 4-([(1E,4E)-5-(2,4-Dimethoxyphenyl)-3-oxopenta-1,4-dien-1-yl])-3-carboxy-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazole-4-yl (9b)

Yellow solid (145.8 mg, 36%); mp 234–237 °C; TLC (Rf, dichloromethane–methanol–acetic acid 96:6:3) 0.57; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 3125 (CH-pyrazole), 3067 (ArH), 2835 (Me), 1686 (C=O), 1651 (C=C), 1582 (C=N); HPLC purity 99.430% (r.t. 13.823 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 13.35 (1H, s, COOH), 9.28 (1H, s, CH-pyrazole), 8.09 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.93 (2H, d, J = 7.5 Hz, ArH), 7.87 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.67 (1H, d, J = 8.5 Hz, ArH), 7.59 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, ArH), 7.44 (1H, t, J = 7.0 Hz, ArH), 7.26 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.11 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 6.65–6.61 (2H, m, ArH), 3.91 (3H, s, OMe), 3.83 (3H, s, OMe); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 188.2, 163.2, 162.9, 159.9, 143.0, 138.7, 137.9, 131.9, 130.6, 129.7, 128.6, 127.8, 126.8, 123.7, 121.6, 119.2, 115.8, 106.3, 98.4, 55.7, 55.5; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C23H20N2O5 [M + H]+ calcd 405.1445, found 405.1406.

4.2.1.19. 4-[(1E,4E)-5-(4-Hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-3-oxopenta-1,4-dien-1-yl]-3-carboxy-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazole-4-yl (9c)

Yellow solid (156.4 mg, 40%); mp 268–271 °C; TLC (Rf, dichloromethane–methanol–acetic acid 96:6:3) 0.34; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 3414 (COOH), 3130 (CH-pyrazole), 3067 (ArH), 2859 (Me), 1694 (C=O), 1651 (C=C), 1585 (C=N); HPLC purity 99.077% (r.t. 8.172 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.69 (1H, s, COOH), 9.27 (1H, s, CH-pyrazole), 8.06 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.92 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.69 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.60 (2H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.45 (1H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, ArH), 7.39 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.35 (1H, s, ArH), 7.20 (1H, d, J = 8.5 Hz, ArH), 6.99 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 6.85 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 3.85 (3H, s, OMe); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 188.1, 163.1, 149.6, 148.0, 143.5, 143.0, 138.7, 131.7, 129.7, 128.5, 127.9, 126.1, 126.0, 123.6, 123.3, 121.7, 119.2, 115.7, 111.4, 55.7; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C22H18N2O5 [M + H]+ calcd 391.1288, found 391.1272.

4.2.1.20. 4-[(1E,4E)-5-(3-Hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)-3-oxopenta-1,4-dien-1-yl]-3-carboxy-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazole-4-yl (9d)

Yellow solid (176.0 mg, 45%); mp 240–243 °C; TLC (Rf, dichloromethane–methanol–acetic acid 96:6:3) 0.37; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 3304 (COOH), 3115 (CH-pyrazole), 3067 (ArH), 2833 (Me), 1682 (C=O), 1651 (C=C), 1586 (C=N); HPLC purity 98.473% (r.t. 8.089 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.27 (2H, s, COOH and CH-pyrazole), 8.06 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.92 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.65 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.60 (2H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.45 (1H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, ArH), 7.37 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.19–7.18 (2H, m, ArH), 7.00 (1H, d, J = 9.0 Hz, ArH), 6.89 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 3.83 (3H, s, OMe); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 188.0, 163.1, 150.3, 146.8, 143.2, 143.1, 138.7, 131.9, 129.7, 128.6, 127.9, 127.4, 126.1, 123.9, 121.6, 121.6, 119.3, 114.1, 112.1, 55.6; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C22H18N2O5 [M + H]+ calcd 391.1288, found 391.1237.

4.2.1.21. 4-[(1E,4E)-5-(4-Hydroxy-3-ethoxyphenyl)-3-oxopenta-1,4-dien-1-yl]-3-carboxy-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazole-4-yl (9e)

Yellow solid (158.0 mg, 39%); mp 247–250 °C; TLC (Rf, dichloromethane–methanol–acetic acid 96:6:3) 0.45; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 3142 (CH-pyrazole), 3068 (ArH), 2878 (Me), 1690 (C=O), 1643 (C=C), 1574 (C=N); HPLC purity 99.442% (r.t. 11.295 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.61 (1H, s, COOH), 9.26 (1H, s, CH-pyrazole), 8.05 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.92 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.68 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.60 (2H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.45 (1H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, ArH), 7.38 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.33 (1H, d, J = 1.5 Hz, ArH), 7.19 (1H, dd, J = 2.0, 8.5 Hz, ArH), 6.97 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 6.86 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 4.11 (2H, q, J = 7.0 Hz, CH2), 1.36 (3H, t, J = 7.0 Hz, Me); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 188.1, 163.1, 149.9, 147.1, 143.6, 143.0, 138.7, 131.7, 129.8, 128.6, 127.9, 126.0, 123.6, 123.2, 121.7, 119.2, 115.8, 112.7, 63.9, 14.7; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C23H20N2O5 [M + H]+ calcd 405.1445, found 405.1405.

4.2.1.22. 4-((1E,4E)-5-(Benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-3-oxopenta-1,4-dien-1-yl)-3-carboxy-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazole-4-yl (9f)

Yellow solid (179.3 mg, 42%); mp 206–209 °C; TLC (Rf, dichloromethane–methanol–acetic acid 96:6:3) 0.56; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 3125 (CH-pyrazole), 3067 (ArH), 1692 (C=O), 1656 (C=C), 1587 (C=N); HPLC purity 98.829% (r.t. 17.379 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.13 (1H, s, CH-pyrazole), 8,28 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.91 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.65 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=); 7.55 (2H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.40 (1H, d, J = 1.5 Hz, ArH), 7.38 (1H, t, J = 7.0 Hz, ArH), 7.24 (1H, dd, J = 1.5, 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.19 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.05 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 6.98 (1H, d, J = 8.5 Hz, ArH), 6.08 (2H, s, CH2); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 188.3, 164.2, 149.3, 148.1, 142.1, 139.1, 134.5, 129.6, 129.5, 129.1, 127.7, 127.1, 125.0, 124.9, 124.2, 120.5, 118.9, 108.6, 106.7, 101.6; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C22H16N2O5 [M – H]− calcd 387.0986, found 387.0926.

4.2.1.23. 4-((1E,4E)-3-Oxo-5-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)penta-1,4-dien-1-yl)-3-carboxy-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazole-4-yl (9g)

Yellow solid (130.5 mg, 30%); mp 264–266 °C; TLC (Rf, dichloromethane–methanol–acetic acid 96:6:3) 0.59; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 3130 (CH-pyrazole), 3065 (ArH), 1694 (C=O), 1654 (C=C), 1599 (C=N); HPLC purity 98.416% (r.t. 12.459 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.29 (1H, s, CH-pyrazole), 8.10 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.93 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.72 (1H, d, J = 16.5 Hz, −CH=), 7.61 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, ArH), 7.46 (1H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, ArH), 7.42 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.14 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.11 (2H, s, ArH), 3.86 (6H, s, OMe), 3.73 (3H, s, OMe); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 188.3, 163.1, 153.1, 143.2, 143.1, 139.7, 138.7, 132.4, 130.1, 129.8, 128.6, 127.9, 126.1, 125.7, 121.6, 119.2, 106.0, 60.1, 56.0; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C24H22N2O6 [M + H]+ calcd 435.1557, found 435.1519.

4.2.1.24. 4-((1E,4E)-5-(4-Hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-3-oxopenta-1,4-dien-1-yl)-3-carboxy-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazole-4-yl (9h)

Yellow solid (117.9 mg, 28%); mp 262–264 °C; TLC (Rf, dichloromethane–methanol–acetic acid 96:6:3) 0.30; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 3504 (COOH), 3130 (CH-pyrazole), 3067 (ArH), 1694 (C=O), 1655 (C=C), 1600 (C=N); HPLC purity 98.875% (r.t. 7.461 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.26 (1H, s, COOH), 9.02 (1H, s, CH-pyrazole), 8.06 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.92 (2H, d, J = 7.5 Hz, ArH), 7.70 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.60 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, ArH), 7.45 (1H, t, J = 7.0 Hz, ArH), 7.40 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.07 (2H, s, ArH), 7.03 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 3.84 (6H, s, OMe); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 188.1, 163.1, 148.1, 143.9, 143.1, 138.7, 138.7, 131.8, 129.8, 127.9, 125.9, 124.9, 124.1, 121.7, 119.2, 106.4, 56.1; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C23H20N2O6 [M + H]+ calcd 421.1400, found 421.1378.

4.2.1.25. (1E,4E)-1-(3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl)-5-(1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)penta-1,4-dien-3-one (10a)55

Yellow solid (236.0 mg, 54%); mp 192–195 °C; TLC (Rf, n-hexane–ethyl acetate 3:2) 0.41; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 3123 (CH-pyrazole), 3007 (ArH), 2841 (Me), 1651 (C=O), 1591 (C=C); HPLC purity 98.062% (r.t. 19.145 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.26 (1H, s, CH-pyrazole), 7.95 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.69 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.69 (2H, dd, J = 1.5, 8.5 Hz, ArH), 7.63 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.60–7.55 (4H, m, ArH), 7.52–7.49 (1H, tt, J = 2.0, 7.0 Hz, ArH), 7.40 (1H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, ArH), 7.38 (1H, d, J = 1.5 Hz, ArH), 7.33 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.30 (1H, dd, J = 2.0, 8.5 Hz, ArH), 7.07 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.03 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 3.84 (3H, s, OMe), 3.82 (3H, s, OMe); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 187.9, 152.6, 151.2, 149.0, 142.9, 139.0, 132.2, 132.0, 129.7, 128.8, 128.6, 128.4, 128.3, 127.4, 127.1, 124.9, 124.4, 123.1, 118.7, 117.8, 111.7, 110.4, 55.6; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C28H24N2O3 [M + H]+ calcd 437.1860, found 437.1745.

4.2.1.26. (1E,4E)-1-(2,4-Dimethoxyphenyl)-5-(1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)penta-1,4-dien-3-one (10b)

Yellow solid (222.9 mg, 51%); mp 161–164 °C; TLC (Rf, n-hexane–ethyl acetate 3:2) 0.51; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 3111 (CH-pyrazole), 3065 (ArH), 2835 (Me), 1641 (C=O), 1601 (C=C); HPLC purity 99.349% (r.t. 8.656 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.26 (1H, s, CH-pyrazole), 7.95 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.85 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.69 (1H, d, J = 8.5 Hz, ArH), 7.68 (2H, d, J = 7.0 Hz, ArH), 7.61 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.59–7.55 (4H, m, ArH), 7.51 (1H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, ArH), 7.40 (1H, t, J = 7.0 Hz, ArH), 7.21 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.09 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 6.65 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz, ArH), 6.62 (1H, dd, J = 2.0, 8.0 Hz, ArH), 3.90 (3H, s, OMe), 3.83 (3H, s, OMe); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 188.0, 162.9, 159.8, 152.6, 139.0, 137.5, 132.1, 132.1, 130.4, 129.6, 128.8, 128.6, 128.5, 128.4, 127.0, 125.5, 123.8, 118.7, 117.7, 115.8, 106.3, 98.4, 55.8, 55.6; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C28H24N2O3 [M + H]+ calcd 437.1860, found 437.1821.

4.2.1.27. (1E,4E)-1-(1,3-Diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-5-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)penta-1,4-dien-3-one (10c)

Yellow solid (198.9 mg, 47%); mp 146–149 °C; TLC (Rf, dichloromethane–methanol 95:5) 0.58; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 3362 (OH), 3122 (CH-pyrazole), 3055 (ArH), 2943 (Me), 1645 (C=O), 1578 (C=C); HPLC purity 98.515% (r.t. 14.820 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.67 (1H, s, OH), 9.25 (1H, s, CH-pyrazole), 7.95 (2H, dd, J = 1.0, 9.0 Hz, ArH), 7.68 (2H, dd, J = 1.5, 8.5 Hz, ArH), 7.66 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.61 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.60–7.55 (4H, m, ArH), 7.50 (1H, tt, J = 1.0, 6.0 Hz, ArH), 7.40 (1H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, ArH), 7.35 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz, ArH), 7.32 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.19 (1H, dd, J = 1.5, 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.00 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 6.85 (1H, d, J = 8.5 Hz, ArH), 3.85 (3H, s, OMe); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 187.9, 152.6, 149.6, 148.0, 143.3, 139.0, 132.0, 131.9, 129.7, 128.8, 128.6, 128.4, 128.4, 127.1, 126.1, 125.0, 123.5, 123.3, 118.7, 117.8, 115.7, 111.3, 55.6; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C27H22N2O3 [M + H]+ calcd 423.1703, found 423.1673.

4.2.1.28. (1E,4E)-1-(1,3-Diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-5-(3-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)penta-1,4-dien-3-one (10d)

Yellow solid (224.2 mg, 54%); mp 190–193 °C; TLC (Rf, dichloromethane–methanol 95:5) 0.55; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 3178 (OH), 3121 (CH-pyrazole), 3039 (ArH), 2841 (Me), 1630 (C=O), 1597 (C=C); HPLC purity 99.433% (r.t. 14.522 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.24 (1H, s, OH), 9.23 (1H, s, CH-pyrazole), 7.95 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.68 (2H, d, J = 7.0 Hz, ArH), 7.61 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.61 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.63–7.55 (4H, m, ArH), 7.51 (1H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, ArH), 7.41 (1H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, ArH), 7.30 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.19–7.17 (2H, m, ArH), 7.00 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 6.90 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 3.83 (3H, s, OMe); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 187.8, 152.6, 150.2, 146.7, 142.9, 139.0, 132.1, 132.0, 129.7, 128.8, 128.7, 128.4, 128.4, 127.4, 127.1, 125.0, 124.0, 121.6, 118.7, 117.8, 114.2, 112.1, 55.6; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C27H22N2O3 [M + H]+ calcd 423.1703, found 423.1678, [M – H]− calcd 421.1558, found 421.1451.

4.2.1.29. (1E,4E)-1-(1,3-Diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-5-(4-hydroxy-3-ethoxyphenyl)penta-1,4-dien-3-one (10e)

Yellow solid (222.9 mg, 51%); mp 176–179 °C; TLC (Rf, n-hexane–ethyl acetate 3:2) 0.45; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 3217 (OH), 3059 (ArH), 2895 (Me), 1645 (C=O), 1580 (C=C); HPLC purity 98.728% (r.t. 18.975 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.59 (1H, s, OH), 9.24 (1H, s, CH-pyrazole), 7.95 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.68 (2H, dd, J = 1.5, 8.5 Hz, ArH), 7.65 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.62 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.59–7.55 (4H, m, ArH), 7.50 (1H, tt, J = 2.0, 7.5 Hz, ArH), 7.40 (1H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, ArH), 7.31 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, ArH), 7.33 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz, ArH), 7.18 (1H, dd, J = 1.5, 8.0 Hz, ArH), 6.99 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 6.86 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 4.11 (2H, q, J = 7.0 Hz, CH2), 1.36 (3H, t, J = 7.0 Hz, Me); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 187.9, 152.6, 149.8, 147.1, 143.3, 139.0, 132.0, 131.9, 129.6, 128.8, 128.6, 128.4, 128.3, 127.1, 126.1, 125.0, 123.5, 123.2, 118.7, 117.8, 115.8, 112.6, 63.9, 14.7; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C28H24N2O3 [M + H]+ calcd 437.1860, found 437.1843.

4.2.1.30. (1E,4E)-1-(Benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-5-(1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)penta-1,4-dien-3-one (10f)

Yellow solid (223.1 mg, 53%); mp 161–164 °C; TLC (Rf, n-hexane–ethyl acetate 2:1) 0.51; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 3123 (CH-pyrazole), 3065 (ArH), 1651 (C=O), 1589 (C=C); HPLC purity 98.694% (r.t. 8.681 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.23 (1H, s, CH-pyrazole), 7.95 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.68 (2H, d, J = 8.5 Hz, ArH), 7.65 (2H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.59–7.55 (4H, m, ArH), 7.50 (1H, tt, J = 2.0, 7.5 Hz, ArH), 7.44 (1H, d, J = 1.5 Hz, ArH), 7.40 (1H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, ArH), 7.25 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.24 (1H, dd, J = 1.5, 8.0 Hz, ArH), 7.07 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.00 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH), 6.10 (2H, s, CH2); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 188.0, 152.6, 149.4, 148.1, 142.5, 139.0, 132.4, 132.0, 129.7, 129.1, 129.8, 128.6, 128.4, 128.4, 127.1, 125.2, 125.2, 124.3, 118.7, 117.7, 108.6, 106.6, 101.6; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C27H20N2O3 [M + H]+ calcd 421.1547, found 421.1540.

4.2.1.31. (1E,4E)-1-(1,3-Diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-5-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)penta-1,4-dien-3-one (10g)55

Yellow solid (186.8 mg, 40%); mp 196–198 °C; TLC (Rf, n-hexane–ethyl acetate–acetone 3:1:1) 0.67; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 3127 (CH-pyrazole), 3063 (ArH), 2828 (Me), 1651 (C=O), 1595 (C=C); HPLC purity 99.560% (r.t. 20.148 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.27 (1H, s, CH-pyrazole), 7.96 (2H, d, J = 7.5 Hz, ArH), 7.69 (2H, d, J = 6.5 Hz, ArH), 7.65 (2H, d, J = 16.5 Hz, −CH=), 7.60–7.55 (4H, m, ArH), 7.51 (1H, t, J = 7.0 Hz, ArH), 7.41 (1H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, ArH), 7.35 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz, −CH=), 7.16 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.10 (2H, s, ArH), 3.85 (6H, s, OMe), 3.72 (3H, s, OMe); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 188.0, 153.1, 152.7, 142.8, 139.6, 138.9, 132.5, 132.0, 130.1, 129.7, 128.8, 128.7, 128.4, 127.1, 126.0, 124.7, 118.7, 117.7, 106.0. 60.1, 56.0; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C29H26N2O4 [M + H]+ calcd 467.1972, found 467.2031.

4.2.1.32. (1E,4E)-1-(1,3-Diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-5-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)penta-1,4-dien-3-one (10h)

Yellow solid (172.1 mg, 38%); mp 181–183 °C; TLC (Rf, n-hexane–ethyl acetate–acetone 3:1:1) 0.32; IR (ATR, ν cm–1): 3510 (OH), 3125 (CH-pyrazole), 3055 (ArH), 2843 (Me), 1651 (C=O), 1508 (C=C); HPLC purity 99.648% (r.t. 13.812 min); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 9.26 (1H, s, OH), 9.06 (1H, s, CH-pyrazole), 7.96 (2H, d, J = 7.5 Hz, ArH), 7.70 (2H, d, J = 7.0 Hz, ArH), 7.68 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz, −CH=), 7.63 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz, −CH=), 7.61–7.56 (4H, m, ArH), 7.51 (1H, t, J = 7.0 Hz, ArH), 7.41 (1H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, ArH), 7.35 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 7.08 (2H, s, ArH), 7.06 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, −CH=), 3.85 (6H, s, OMe); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm): 197.4, 162.1, 157.6, 153.1, 148.5, 148.1, 141.5, 141.5, 139.2, 138.3, 138.1, 137.9, 137.8, 136.6, 134.4, 134.4, 133.5, 128.2, 127.3, 115.9, 65.6; HR-MS (ESI, m/z): C28H24N2O4 [M + H]+ calcd 453.1815, found 453.1794.

4.3. Biological Evaluation

4.3.1. MTT Cytotoxic Assay

The in vitro anticancer activity of synthetic compounds was determined using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. About 2.5–5 × 103 cells per well were seeded in 100 μL of DMEM or RPMI 1640, supplemented with 10% FBS, 4 mM of l-glutamine, 100 IU·mL–1 penicillin, and 100 μM streptomycin in each well of 96-well plates and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Compounds at designed concentrations were added to wells with respective vehicle control. Paclitaxel and equivalent amounts of solvent used to dissolve the compounds were used as the positive and negative controls, respectively, whereas curcumin was used for comparison. After 72 h of incubation period, the medium was removed, then 100 μL of MTT (0.5 mg·mL–1) containing serum-free medium was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for 3 h. The supernatant from each well was removed carefully; formazan crystals were dissolved in 200 μL of acidified isopropanol, and the absorbance was recorded at 570 nm wavelength with a Multiskan FC Microplate Photometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Then, cytotoxic activities and half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) were calculated.58

4.3.2. Tubulin Polymerization Inhibitory Assay

To assess the effect of potential compounds on tubulin polymerization, a fluorescence-based in vitro tubulin polymerization assay was carried out according to the manufacturer’s protocol (BK011P, Cytoskeleton, Denver, CO). The reaction mixture consisting of 2.0 mg·mL–1 porcine brain tubulin in 80 mM PIPES at pH 6.9, 2.0 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EGTA, 1.0 mM GTP, and 15% glycerol in the presence of sample compounds at a final concentration of 20.0 μM or the equivalent amount of DMSO at a final concentration of 1% (v/v) was prepared and added to each well of a black 96-well plate. Paclitaxel and colchicine at a final concentration of 3.0 μM were used as the positive and negative controls, respectively. Tubulin polymerization was followed by a time-dependent increase in fluorescence intensity due to the incorporation of a fluorescence reporter into microtubules as polymerization proceeds. Tubulin assembly was determined via measuring fluorescence variation at 410 nm (excitation wavelength is 360 nm) and 37 °C every 60 s for 60 min was recorded using a Varioskan LUX Multimode Microplate Reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Data obtained were reduced to the maximum slope of the growth phase (Vmax) of microtubule polymerization using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA), and then the Vmax data were converted into a percentage change in the Vmax of control.

4.3.3. Acridine Orange/Ethidium Bromide (AO/EB) Staining