Abstract

The redox-sensing flavoprotein NifL inhibits the activity of the nitrogen fixation (nif)-specific transcriptional activator NifA in Azotobacter vinelandii in response to molecular oxygen and fixed nitrogen. Although the mechanism whereby the A. vinelandii NifL-NifA system responds to fixed nitrogen in vivo is unknown, the glnK gene, which encodes a PII-like signal transduction protein, has been implicated in nitrogen control. However, the precise function of A. vinelandii glnK in this response is difficult to establish because of the essential nature of this gene. We have shown previously that A. vinelandii NifL is able to respond to fixed nitrogen to control NifA activity when expressed in Escherichia coli. In this study, we investigated the role of the E. coli PII-like signal transduction proteins in nitrogen control of the A. vinelandii NifL-NifA regulatory system in vivo. In contrast to recent findings with Klebsiella pneumoniae NifL, our results indicate that neither the E. coli PII nor GlnK protein is required to relieve inhibition by A. vinelandii NifL under nitrogen-limiting conditions. Moreover, disruption of both the E. coli glnB and ntrC genes resulted in a complete loss of nitrogen regulation of NifA activity by NifL. We observe that glnB ntrC and glnB glnK ntrC mutant strains accumulate high levels of intracellular 2-oxoglutarate under conditions of nitrogen excess. These findings are in accord with our recent in vitro observations (R. Little, F. Reyes-Ramirez, Y. Zhang, W. Van Heeswijk, and R. Dixon, EMBO J. 19:6041–6050, 2000) and suggest a model in which nitrogen control of the A. vinelandii NifL-NifA system is achieved through the response to the level of 2-oxoglutarate and an interaction with PII-like proteins under conditions of nitrogen excess.

In diazotrophic proteobacteria, the ς54-dependent activator NifA activates transcription of the nif (nitrogen fixation) genes by a conserved mechanism common to members of the enhancer binding protein family (5). Although NifA proteins have similar domain structures, both transcriptional regulation of nifA expression and posttranslational regulation of NifA activity by oxygen and fixed nitrogen vary significantly from one organism to another.

Signal transduction in response to fixed nitrogen status has been best studied in Escherichia coli at both the genetic and biochemical levels (26, 27). Cells respond to changes in nitrogen availability by modifying the activity of a key sensory regulatory protein, PII, the product of glnB. Under conditions of nitrogen excess, when the internal concentration of glutamine is high, PII is primarily unmodified; in conditions of nitrogen limitation, PII is mainly uridylylated. The enzyme responsible for this covalent modification is an uridylyltransferase/uridylyl-removing enzyme (UTase/UR) encoded by the glnD gene. The degree of uridylylation of PII has major physiological implications with respect to both the level and activity of glutamine synthetase (GS), the product of glnA. Under nitrogen-excess conditions, native PII protein prevents transcription from the ntr promoters by stimulating the histidine protein kinase NtrB to dephosphorylate its cognate response regulator, NtrC (16, 17), leading to decreased expression of glnA. In addition, PII stimulates the enzyme adenylyltransferase to adenylylate GS, which decreases its activity (15, 18). Under nitrogen limitation, uridylylation of PII prevents its interaction with NtrB, and thus NtrC is maintained primarily in its phosphorylated form. In addition, PII-UMP stimulates the deadenylation activity of adenyltransferase, which catalyzes the conversion of the inactive GS-AMP to active GS.

E. coli contains a second PII-like protein, which is encoded by the glnK gene (36, 37). This PII paralogue is also regulated by the UTase/UR in response to nitrogen availability and also plays a role in nitrogen regulation (2, 3). While expression of the glnB gene is constitutive with respect to the intracellular nitrogen status, glnK is encoded in the NtrC-dependent operon glnK-amtB, in which amtB encodes a high-affinity ammonium transporter (33). Thus, expression of glnK is subject to nitrogen regulation by the NtrB-NtrC two-component regulatory system, and essentially little GlnK is expressed under conditions of nitrogen excess.

Many proteobacteria express more than one homologue of the PII protein, and current evidence suggests that at least one of the PII-like proteins is involved in nitrogen control of NifA expression and/or activity in several diazotrophs. In Klebsiella pneumoniae and Azotobacter vinelandii, which are members of the gamma subdivision of Proteobacteria, nifA is coordinately transcribed with a second gene, nifL, whose product inhibits NifA activity in response to oxygen and fixed nitrogen (9, 10). Transcription of the K. pneumoniae nifLA operon is activated by the phosphorylated form of NtrC and is therefore influenced by nitrogen availability, whereas in A. vinelandii nifLA expression is constitutive. The identification of two PII-like proteins in enteric bacteria has facilitated analysis of nitrogen control of nitrogen fixation in K. pneumoniae. Recent evidence suggests that the alternative PII-like protein GlnK is required to relieve inhibition of NifA activity by K. pneumoniae NifL under nitrogen-limiting conditions (12, 14). This conclusion is based on the observation that NifL inhibits NifA activity irrespective of the nitrogen status in enteric glnK mutants. Furthermore, the uridylylation state of GlnK is apparently irrelevant for relief of inhibition by NifL in K. pneumoniae (11) and in E. coli (12). Although GlnK clearly has a role in maintaining NifL in an inactive state under derepressing conditions for nitrogen fixation, it is not obvious how the K. pneumoniae NifL-NifA system responds rapidly to changes in nitrogen status.

Although K. pneumoniae and A. vinelandii NifL have similar functions, there is some evidence that A. vinelandii NifL may use a different mechanism to respond to the cellular nitrogen status. Previous genetic studies in A. vinelandii revealed that a mutation in nfrX (now called glnD), which encodes a homologue of E. coli UTase/UR, gave rise to a Nif phenotype which could be suppressed by a secondary mutation in nifL (8). These results suggested that in contrast to K. pneumoniae, uridylylation of a regulatory component may be required to prevent inhibition by NifL. Current evidence indicates that A. vinelandii contains only a single PII-like protein encoded by a gene designated glnK, and in contrast to E. coli and K. pneumoniae, the glnK-amtB operon is expressed under all conditions regardless of fixed nitrogen supply (25). The PII-like protein encoded by A. vinelandii glnK (Av PII) could therefore be a good candidate for a signal transduction component which could interface between GlnD and NifL, thus controlling the activity of NifL in response to the uridylylation state of PII. However, determination of the role of A. vinelandii glnK gene product in nitrogen signaling has been thwarted by the essential nature of this gene since it has not been possible to isolate null mutations in glnK (25).

Since it has not been possible to study in vivo regulation of nitrogen fixation in A. vinelandii in the complete absence of the PII-like protein, we have resorted to a heterologous system to analyzse the response of the A. vinelandii NifL-NifA system in glnB and glnK mutants. We have shown previously that, as is the case with the K. pneumoniae NifL-NifA system, A. vinelandii NifL modulates NifA activity in E. coli in response to oxygen and fixed nitrogen (32). We have used this heterologous system to study the role of the PII-like regulatory proteins in nitrogen regulation of A. vinelandii NifL activity. We anticipated that both A. vinelandii and K. pneumoniae NifL would respond to a common signal transduction pathway for sensing the nitrogen status in E. coli. Surprisingly, we found that in contrast to K. pneumoniae NifL, neither PII nor GlnK is required to relieve inhibition by A. vinelandii NifL under nitrogen-limiting conditions. Moreover, in mutants lacking both the PII and NtrC proteins, NifL activity is no longer responsive to the nitrogen status. These results reveal striking differences in the mechanism of nitrogen regulation of NifL activity between A. vinelandii and K. pneumoniae.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

E. coli mutant strain constructions.

All strains used were derivatives of E. coli ET8000 (Table 1). To construct the ΔglnB1 mutation, the 0.31-kb AgeI-EcoNI fragment from plasmid pAH5 which carries the E. coli glnB region was deleted, and the 5′ extensions from the digested plasmid were trimmed by incubation with mung bean nuclease. The blunt-end extensions were ligated, producing plasmid pglnB19. A SalI-BglII fragment carrying the deleted glnB gene from this plasmid was cloned into the gene replacement vector pKO3 digested with SalI and BamHI, generating plasmid pglnBO3. E. coli ET8000 was transformed with pglnBO3, and homologous recombination between the cloned fragment and bacterial chromosome was carried out as described previously (19), resulting in strain PT8000. The absence of wild-type sequences in the recombinant was confirmed by PCR analysis using primers 5′ TGAAACGCCTGATGAC 3′ and 5′ CTATTCCCGATGCCGTTG 3′, which flank the glnB region.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| YMC10 | ΔlacU169 endA1 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 hutCk (wild type) | 7 |

| RB9066 | ΔlacU169 endA1 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 hutCk ntrC10::Tn5 | 6 |

| WCH30 | ΔlacU169 endA1 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 hut Ck ΩGmr ΔglnK1 | 1 |

| ET8000 | rbs lacZ::IS1 gyr A hutCcK (wild type) | 24 |

| PT8000 | rbs lacZ::IS1 gyr A hutCcK ΔglnB1 | This work |

| GT1002 | rbs lacZ::IS1 gyr A hutCcK ΩGmr ΔglnK1 | Gavin Thomas |

| GT1001 | rbs lacZ::IS1 gyr A hutCcK ΔamtB | 34 |

| AT8000 | rbs lacZ::IS1 gyr A hutCcK ΔglnB1 ΔamtB | This work |

| FT8000 | rbs lacZ::IS1 gyr A hutCcK ΔglnB1 ΩGmr ΔglnK1 | This work |

| NT8000 | rbs lacZ::IS1 gyr A hutCcK ntrC10::Tn5 | This work |

| RT8000 | rbs lacZ::IS1 gyr A hutCcK ΔglnB1 ntrC10::Tn5 | This work |

| MT8000 | rbs lacZ::IS1 gyr A hutCcK ΔglnB1 ΩGmr ΔglnK1 ntrC10::Tn5 | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pRT22 | pnifH-lacZ in pACYC184 | 35 |

| pPR34 | A. vinelandii nifLA translated from the natural ribosome binding site of nifL in pT7-7 | 32 |

| pPR54 | Derivative of pPR34 expressing NifL(147–519) and NifA | 32 |

| pPR39 | Derivative of pPR34 expressing NifL(454–519) and NifA | 32 |

| pKO3 | Gene replacement plasmid | 19 |

| pAH5 | E. coli glnB in pUC18 | 13 |

| pGlnB19 | ΔglnB in pUC19 | This work |

| pGlnBO3 | ΔglnB in pKO3 | This work |

Strain GT1002 carrying a glnK in-frame deletion was made by transducing the ΔglnK1 mutation from strain WCH30 into ET8000 using phage P1. In addition to the glnK deletion, WCH30 contains a gentamicin resistance Ω cassette inserted 171 bp upstream of glnK; hence, the transductant colonies were selected by their resistance to gentamicin and were tested by PCR to verify the presence of the glnK deletion (1).

GT1001 containing the amtB mutation has been described previously (34). The double-mutant glnB glnK and glnB amtB strains were made by transforming pglnBO3 into strains GT1002 and GT1001, respectively. Recombinant colonies in which chromosomal glnB replacement was performed were confirmed by PCR, resulting in strains FT8000 and AT8000, respectively.

Strain NT8000 carrying the ntrC10::Tn5 null allele was obtained by transducing this mutation from strain RB9066 into ET8000 by P1-mediated transduction. As expected, the resulting kanamycin-resistant colonies were unable to use arginine as the sole nitrogen source. To obtain the double-mutant glnB ntrC and triple-mutant glnB glnK ntrC strains, the same ntrC10::Tn5 null allele was introduced into strains PT8000 and FT8000, respectively. The mutants strains were selected by their resistance to kanamycin and their glutamine auxotrophy.

β-Galactosidase assays and growth conditions.

To assay β-galactosidase activity, E. coli strains were transformed with plasmid pRT22, which carries a nifH-lacZ translational fusion. NifA activity was measured by determining the level of expression from the nifH promoter. To monitor the ability of wild-type NifL or the truncated NifL(147–519) protein (which lacks the redox response) to inhibit NifA activity, E. coli strains were transformed with plasmids pRT22 and pPR34 or pRT22 and pPR54, respectively. The activity of NifA alone was assayed by transforming E. coli strains with plasmids pRT22 and pPR39 (Table 1) (32).

For β-galactosidase assays and for determination of intracellular pools of 2-oxoglutarate, E. coli strains were grown to late exponential phase in Luria-Bertani medium at 30°C in the presence of appropriate antibiotics. Aliquots (50 μl) of these cultures were then inoculated into 4 ml of NFDM medium (30) supplemented with casein hydrolysate (200 μg ml−1) and glutamine (25 μg ml−1) for nitrogen-limiting conditions or with (NH4)2SO4 (1 mg ml−1) plus glutamine (25 μg ml−1) for nitrogen-excess conditions. Cultures were grown in a plastic vial (7-ml internal volume) sealed with a rubber closure for anaerobic conditions. When conditions required aerobiosis, 5-ml cultures were grown with vigorous shaking in 25-ml conical flasks.

Determination of intracellular 2-oxoglutarate.

Extracts for measurements of 2-oxoglutarate were prepared as described previously (21), with minor amendments. Portions of cultures (8 ml) were filtered through 0.45-μm-pore-size membrane filters (25-mm diameter) with vacuum suction. As soon as the liquid was removed (∼30 s), the filter was transferred to an Eppendorf centrifuge tube containing 1 ml of 0.3 M HClO4 plus 1 mM EDTA at 0°C. Once the tube contents were mixed thoroughly, the filter was removed from the Eppendorf tube and the content was centrifuged to remove debris. Then 500 μl of the extract was removed and neutralized by the addition of 75 μl of 2 M K2CO3. The resulting KClO4 precipitate was removed by centrifugation, and the supernatant fluid was stored at −80°C for further analysis.

2-Oxoglutarate was determined by fluorometric procedures (22), with some modifications. Reaction mixes contained 0.06 ml of 0.5 M imidazole acetate buffer (pH 7.0), 0.03 ml of 0.625 M ammonium acetate, 0.0075 ml of 0.4 mM NADH, 0.01 ml of glutamate dehydrogenase (1 mg/ml), and sample (0.05 to 0.19 ml). Distilled water was added to a final volume of 0.3 ml. The disappearance of NADH after the addition of glutamate dehydrogenase was measured by the decrease in fluorescence, using a Perkin-Elmer model LS50B spectrofluorimeter with an excitation wavelength of 340 nm and an emission wavelength of 460 nm. The concentration of 2-oxoglutarate in the cell extract was estimated based on the decay of fluorescence in the reaction mix measured against standards containing 0.6 to 3 nmol of 2-oxoglutarate, prepared using the same neutralization procedure as used for the cell extracts. Protein was determined by the Lowry method (23), with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Western blotting.

Western blotting was performed as described previously (30), using polyclonal antisera against A. vinelandii NifL and NifA raised in rabbits and the Amersham enhanced chemiluminescense system for detection.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Activity of A. vinelandii NifL and NifA in E. coli.

We have shown previously that when the A. vinelandii nifL and nifA genes are expressed from a constitutive promoter in E. coli, transcriptional activation of a nifHp-lacZ reporter is responsive to fixed nitrogen and oxygen in vivo. These results indicate that the Azotobacter NifL and NifA proteins are competent to interact with signal transduction components in E. coli and that this heterologous system can be used to analyze nitrogen regulation of NifA activity by NifL. Since some of the E. coli mutant strains studied below grew poorly on minimal medium unless supplemented with glutamine, we checked that the addition of glutamine in our standard culture conditions did not alter the level of NifA activity in the presence of NifL (Table 2). As observed previously, we found that when both nifL and nifA were expressed, NifA was active only under anaerobic and nitrogen-limiting conditions (32). We also confirmed that removal of the first 146 residues of NifL, which includes the redox-sensing PAS domain, rendered the protein unable to inhibit NifA under oxic conditions unless ammonia was present in the medium (Table 2). We use this truncated protein throughout the course of our experiments as a control on the specificity of the nitrogen response. It is notable that when the coding sequence of nifL is almost entirely deleted (producing a putative truncated peptide containing 65 C-terminal residues of NifL), NifA activity is 10-fold higher under anaerobic and nitrogen-limiting conditions than when wild-type NifL is present (Table 2). Similar high levels of NifA activity were observed with some mutant NifA proteins which escape inhibition in the presence of wild-type NifL (data not shown). This suggests that NifL retains some inhibitory function even when conditions are derepressing for nitrogen fixation. Thus, some factor(s) required to maintain A. vinelandii NifL in its inactive form may be limiting under our growth conditions in E. coli.

TABLE 2.

Inhibition of NifA activity by NifL in response to oxygen and nitrogen in wild-type E. coli strain ET8000

| Plasmida | Proteins | β-Galactosidase activityb (mean ± SD)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anaerobic

|

Aerobic

|

||||

| −N | +N | −N | +N | ||

| pPR34 | NifL, NifA | 2,300 ± 273 (2,800) | 35 ± 7.5 (42) | 210 ± 63 (255) | 55 ± 5.6 (91) |

| pPR54 | NifL(147–519), NifA | 2,300 ± 610 (1,900) | 37 ± 8.5 (35) | 3,600 ± 600 (3,510) | 120 ± 14.5 (227) |

| pPR39 | NifL(454–519), NifA | 25,000 ± 1,290 (20,000) | 46,000 ± 1,370 (41,100) | 24,000 ± 2,000 (22,360) | 26,000 ± 2,100 (23,000) |

All strains contain the nifH-lacZ reporter plasmid pRT22 and the indicated plasmid expressing the appropriate Nif regulatory proteins.

NifA-mediated activation of transcription from the nifH promoter, measured as β-galactosidase activity in Miller units, in cultures grown under the conditions indicated with either casein hydrolysate and glutamine (−N) or (NH4)2SO4 and glutamine (+N) as nitrogen sources. Numbers in parentheses indicate data obtained in the absence of glutamine.

PII-like proteins are not required to prevent A. vinelandii NifL from inhibiting NifA under derepressing conditions for nitrogen fixation.

Since the A. vinelandii NifL-NifA regulatory system is apparently responsive to the nitrogen status in E. coli, it was of interest to determine which nitrogen regulatory genes are required for the nitrogen response. Inhibition of NifA activity by NifL was assessed in various E. coli mutant strains defective in nitrogen regulation by determining the level of expression from a nifH-lacZ translational fusion carrying the reporter plasmid pRT22 (Table 3). Single null mutations in glnB and glnK had little influence on the activity of NifA in the absence of NifL. That is, the levels of NifA activity in the absence of NifL were similar under nitrogen-deficient and nitrogen-excess conditions, as previously observed with the wild-type strain. The glnB null mutation also had little apparent influence on the activity of either NifL or NifL(147–519) under nitrogen-limiting anaerobic conditions. However, there was almost a threefold decrease in the inhibitory activity of NifL compared with the wild-type strain under nitrogen-excess conditions, resulting in a decrease in the nitrogen repression ratio (Table 3, PT8000). A similar pattern of activity was seen in the strain containing only the glnK mutation. We also observed an increased level of β-galactosidase activity under nitrogen limitation when this strain carried exclusively the reporter plasmid pRT22 (Table 3, GT1002). This could be largely due to a high intracellular level of phosphorylated NtrC under these conditions, as suggested by the observation that this strain displayed an apparent increased growth rate in liquid glucose-arginine medium, a demanding test for NtrC activity (3). This can be explained in the context that GlnK is required for fine control of the level of phosphorylated NtrC as previously suggested (3). The observation that the activity of neither NifL nor NifL(147–519) was significantly influenced by the glnK mutation is remarkably different from what is observed with the K. pneumoniae NifL-NifA system. In this case no activation of the nifH promoter is observed in glnK mutant strains when both NifL and NifA are present, indicating that glnK is absolutely required to prevent K. pneumoniae NifL from inhibiting NifA activity (12, 14).

TABLE 3.

Influence of nitrogen regulatory mutations on the regulation of NifA activity by NifL

| Straina | Genotype | β-Galactosidase activityb

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (pRT22)

|

NifL + NifA (pRT22, pPR34)

|

NifL(147–519) + NifA (pRT22, pPR54)

|

NifA (pRT22, pPR39)

|

||||||||||

| −N | +N | Ratio | −N | +N | Ratio | −N | +N | Ratio | −N | +N | Ratio | ||

| ET8000 | Wild type | 94 | 15 | 6.3 | 2,300 | 35 | 65.7 | 2,300 | 37 | 62.2 | 25,000 | 47,000 | 0.53 |

| PT8000 | glnB | 93 | 17 | 5.5 | 2,000 | 115 | 17.4 | 2,300 | 110 | 20.9 | 25,000 | 58,000 | 0.43 |

| GT1002 | glnK | 390 | 15 | 26 | 1,900 | 99 | 19.1 | 2,300 | 100 | 23 | 25,000 | 57,000 | 0.44 |

| FT8000 | glnB glnK | 330 | 490 | 0.7 | 2,300 | 636 | 3.6 | 2,600 | 610 | 4.3 | 21,000 | 53,000 | 0.40 |

| MT8000 | glnB glnK ntrC | 36 | 14 | 2.6 | 9,900 | 8,900 | 1.1 | 11,000 | 8,300 | 1.3 | 30,000 | 58,000 | 0.52 |

| RT8000 | glnB ntrC | 27 | 14 | 1.9 | 4,900 | 3,100 | 1.6 | 3,800 | 3,100 | 1.2 | 30,000 | 40,000 | 0.75 |

| NT8000 | ntrC | 39 | 10 | 3.9 | 3,300 | 332 | 9.9 | 4,100 | 210 | 19.5 | 23,000 | 59,000 | 0.39 |

| GT1001 | amtB | 88 | 16 | 5.5 | 2,200 | 30 | 73.3 | 2,100 | 27 | 77.7 | 20,000 | 49,000 | 0.40 |

| AT8000 | glnB amtB | 55 | 12 | 4.6 | 2,400 | 81 | 29.6 | 2,200 | 99 | 22.2 | 21,000 | 51,000 | 0.41 |

All strains contained the nifH-lacZ reporter plasmid pRT22 and an additional plasmid expressing the appropriate Nif regulatory protein.

NifA-mediated activation of transcription from the nifH promoter, measured as β-galactosidase activity in Miller units, in cultures grown in anaerobiosis with either casein hydrolysate and glutamine (−N) or (NH4)2SO4 and glutamine (+N) as nitrogen sources. Values represent the mean of at least three independent determinations. In most assays standard deviations were less than 20% of the mean.

We considered the possibility that under nitrogen-limiting conditions, single mutations in either glnB or glnK might not reveal a requirement for relief of inhibition by A. vinelandii NifL since PII and GlnK might substitute for one another to prevent inhibition. We therefore tested NifL inhibition in a glnB glnK double-mutant strain. Atkinson and Ninfa have reported that such strains exhibit severe growth defects in minimal media (3). In our hands, the double-mutant strain grew more slowly than the wild-type strain in minimal medium containing ammonia and glutamine as nitrogen sources, and we also observed that the presence of casein hydrolysate relieved the growth rate defect to a certain extent. We noted that under conditions of either nitrogen limitation or nitrogen excess, the background level of expression from the nifH-lacZ reporter was significantly higher in the glnB glnK mutant strain than in the wild-type strain (Table 3, FT8000). We attribute this to an increased level of phosphorylated NtrC in the double-mutant strain (3). The glnB glnK mutations had no apparent effect on the activity of NifA alone, and under nitrogen-limiting conditions, the same relief of inhibition of NifA activity in the presence of NifL was observed as in the wild-type strain. Similar results were obtained with the truncated form of NifL (Table 3, FT8000). These results rule out the possibility for a negative role of the PII regulatory proteins under derepressing conditions for nitrogen fixation and suggest that neither PII nor GlnK is necessary for relief of inhibition by A. vinelandii NifL under these conditions. However, the NifL-NifA system still remained responsive to fixed nitrogen in the double-mutant strain, implying that nitrogen regulation still occurs even in the absence of glnB and glnK. Nevertheless, the nitrogen repression ratio is considerable lower in this strain than in the wild type (3.6 and 65.8, respectively), although this result is difficult to interpret as a consequence of the high levels of β-galactosidase observed with the reporter plasmid.

Nitrogen regulation of NifL activity is absent in strains carrying both ntrC and glnB mutations.

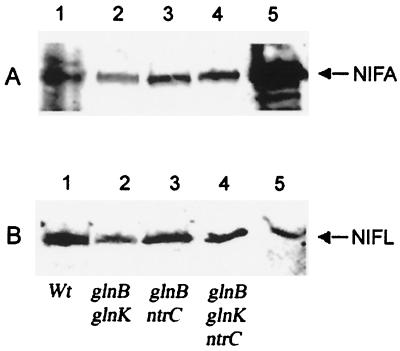

Since the data obtained with the glnB glnK mutant could be influenced by its slow growth and the presence of high levels of phosphorylated NtrC, we examined the effect of introducing a ntrC::Tn5 mutation into the double-mutant strain. As expected, this mutation rendered cells auxotrophic for glutamine, presumably as a consequence of the influence of these mutations on the expression and activity of GS. Surprisingly, under conditions of nitrogen excess, NifL inhibition was substantially relieved in the triple-mutant strain in the case of both native NifL and the truncated variant, and in both cases the repression ratio was close to 1 (Table 3, MT8000). Moreover, in this background, greater relief of NifL inhibition was seen under nitrogen-limiting conditions compared with the wild-type strain, regardless of whether native NifL or NifL(147–519) was present (Table 3, compare ET8000 and MT8000). These data clearly demonstrate that neither of the PII paralogues are required to relieve inhibition by A. vinelandii NifL under N-limiting conditions. Since phosphorylated NtrC is required for activation of GlnK expression in E. coli, we suspected that the glnK mutation did not contribute to the phenotype of the glnB glnK ntrC strain. Accordingly, we constructed a glnB ntrC double-mutant strain. The nitrogen response of NifL in this strain was similar to that observed with the triple mutant, although the levels of NifA activity observed in the presence of NifL or NifL(147–519) under nitrogen-limiting conditions were lower than those observed with the glnB glnK ntrC strain (Table 3, RT8000). Western blotting analysis suggested that there were no major differences in the levels of NifL and NifA expression in the mutant strains compared with the wild-type, and the ratios of NifL to NifA were similar in all cases (Fig. 1). Hence, the failure of NifL to inhibit NifA activity in the mutant strains under nitrogen-excess conditions is unlikely to be a consequence of decreases in the level of NifL protein or to the presence of excess NifA in these strains.

FIG. 1.

Immunodetection of NifA and NifL in E. coli wild-type and mutants strains grown under nitrogen-excess conditions. All strains carried the reporter plasmid pRT22 in addition to pPR34, which encodes wild-type NifL and NifA, and were grown in NFDM medium containing (NH4)2SO4 and glutamine as nitrogen sources. Samples were subjected to Western blotting as described in Materials and Methods with polyclonal antiserum against either NifA (A) or NifL (B). Lanes: 1, wild type (Wt; ET8000); lane 2, glnB glnK (FT8000); lane 3, glnB ntrC (RT8000); lane 4, glnB glnK ntrC (MT8000); lane 5, either purified NifA (A) or purified NifL (B) as control.

To ensure that the loss of NifL inhibition was specific to the nitrogen response, we also tested the redox response of NifL under aerobic conditions in the triple-mutant strain (Table 4). As expected, native NifL was responsive to oxygen inhibition in the wild-type and mutant strains (compare Tables 3 and 4), whereas the truncated NifL(147–519) protein was insensitive to aerobiosis in the wild-type and glnB strains but nevertheless was responsive to the nitrogen source (Table 4.) In contrast, when expressed in the triple glnB glnK ntrC mutant, the truncated NifL protein was unable to inhibit NifA activity regardless of the growth conditions, and the level of NifA activity remained significantly higher than in the wild-type strain even in nitrogen-limiting conditions (Table 4). These results are similar to those obtained under anaerobic conditions and suggest that the presence of NtrC in combination with PII influences the nitrogen but not the oxygen response of the A. vinelandii NifL-NifA system in E. coli.

TABLE 4.

Inhibition of NifA activity by NifL and NifL(147–519) under aerobic conditions

| Straina | Genotype | β-Galactosidase activityb

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NifL + NifA (pRT22, pPR34)

|

NifL(147–519) + NifA (pRT22, pPR54)

|

||||

| −N | +N | −N | +N | ||

| ET8000 | Wild type | 210 | 55 | 3,500 | 120 |

| PT8000 | glnB | 190 | 32 | 5,200 | 300 |

| MT8000 | glnB glnK ntrC | 360 | 550 | 16,000 | 11,000 |

All strains contained the nifH-lacZ reporter plasmid pRT22 and plasmids expressing the appropriate Nif regulatory proteins.

NifA-mediated activation of transcription from the nifH promoter, measured as β-galactosidase activity in Miller units, in cultures grown in aerobiosis with either casein hydrolysate and glutamine (−N) or (NH4)2SO4 and glutamine (+N) as nitrogen sources. Standard deviations were within 11% of the mean.

Since ntrC mutants have pleiotropic effects on nitrogen metabolism, the results observed in the mutant strains could potentially be physiological or perhaps due to the lack of expression of a specific gene or operon which is subject to NtrC control. We therefore studied the activity of NifL in a strain containing an ntrC null mutation. Although this strain gave slightly greater relief of NifL inhibition under nitrogen-limiting conditions compared with the wild type (around 1.5-fold), the NifL and the NifL(147–519) proteins remained responsive to fixed nitrogen in this background, although the nitrogen repression ratio was lower than in the wild-type strain (Table 3, NT8000). Hence, the absence of NtrC by itself is not sufficient to inactivate the nitrogen response of A. vinelandii NifL.

As relief of NifL inhibition under nitrogen-excess conditions was not observed in either the glnB or ntrC single-mutant strain, inactivation of the nitrogen response apparently requires mutations in both glnB and ntrC. Since NtrC is required for transcription of the glnK-amtB operon, we also considered the possibility that the methylammonium transporter amtB might be required for the nitrogen response. However, neither an amtB or a double-mutant glnB amtB background appeared to influence NifL activity (Table 3, GT1001 and AT8000).

Relationship between in vivo 2-oxoglutarate pools and NifL activity.

The above observation that the combination of glnB and ntrC mutations eliminates the nitrogen response of A. vinelandii NifL in E. coli suggests that more than one factor is involved in this response. In addition to the potential role of the PII paralogues, the additional factor could be a metabolite whose levels are influenced by the ntrC mutation or a gene product which is expressed under the control of NtrC. It is interesting to consider the former possibility in the light of our recent in vitro data, which demonstrates that the NifL-NifA system is directly responsive to 2-oxoglutarate within the physiological range (20). Under conditions of nitrogen excess, the reported 2-oxoglurate concentration in E. coli is ∼100 μM, which increases to ∼1 mM under conditions of nitrogen limitation (31). We therefore considered the possibility that 2-oxoglutarate could be an effector required for relief of inhibition by NifL in vivo. To investigate this hypothesis, we measured the intracellular accumulation of 2-oxoglutarate in E. coli mutant strains grown under conditions identical to those used to determine transcriptional activation by NifA using the reporter system. The 2-oxoglutarate concentration was below the level of detection (>50 μM) in the wild-type strain grown under conditions of nitrogen excess (glucose, ammonia, and glutamine) but increased by a factor of at least 30-fold to ∼10 nmol/mg of protein under nitrogen-limiting conditions (Table 5, ET8000). This value corresponds to ∼3 nmol/mg (dry weight), or an intracellular concentration of ∼1.5 mM. Similar results were observed with the glnB mutant (Table 5, PT8000). Surprisingly, the level of 2-oxoglutarate increased substantially in the glnB glnK double mutant under nitrogen-excess conditions. This may result from overadenylylation of GS in this strain (3, 6) and consequent accumulation of 2-oxoglutarate in the absence of efficient nitrogen assimilation. The ntrC mutation did not appear to influence 2-oxoglutarate accumulation under conditions of nitrogen excess, but a small increase was observed under nitrogen-limiting conditions. This might be expected if nitrogen is poorly assimilated since the level of GS is significantly decreased in ntrC mutants under conditions of nitrogen limitation (28). In contrast, the combination of the ntrC with the glnB or glnB and glnK mutations gave rise to a high level of 2-oxoglutarate accumulation under conditions of nitrogen excess, resulting in levels similar to that observed with the wild-type strain under nitrogen-limiting conditions (Table 5, MT8000 and RT8000 compared with ET8000). We interpret this accumulation as a consequence of physiological nitrogen limitation in these strains even when excess external ammonium is present. Notably, the growth rates of these strains were similar in the presence and absence of ammonia. Overall, these results suggest that there is some correlation between the intracellular accumulation of 2-oxoglutarate and the nitrogen repression ratio observed with the nifH-lacZ reporter (Table 3), indicating that 2-oxoglutarate may have a role in modulating the activity of the A. vinelandii NifL-NifA system in vivo.

TABLE 5.

Intracellular accumulation of 2-oxoglutarate

| Straina | Genotype | Mean 2-oxoglutarate (nmol/mg of protein) ± SDb

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| −N | +N | ||

| ET8000 | Wild type | 9.94 ± 0.56 | <0.3 |

| PT8000 | glnB | 10.12 ± 0.50 | <0.3 |

| FT8000 | glnB glnK | 9.55 ± 0.90 | 2.62 ± 0.82 |

| NT8000 | ntrC | 13.71 ± 0.84 | <0.3 |

| RT8000 | glnB ntrC | 12.40 ± 0.55 | 6.91 ± 0.90 |

| MT8000 | glnB glnK ntrC | 14.24 ± 0.34 | 8.26 ± 0.55 |

All strains contained the nifH-lacZ reporter plasmid pRT22 in addition to plasmid pPR34, which encodes wild-type NifL and NifA.

Values represent means of at least three independent determinations for cultures grown in anaerobiosis with either casein hydrolysate and glutamine (−N) or (NH4)2SO4 and glutamine (+N) as nitrogen sources. Similar results were obtained when strains were compared on the basis of dry weight (data not shown).

Conclusions.

We have utilized defined E. coli mutant strains to analyze nitrogen regulation of A. vinelandii NifA activity mediated by NifL. This heterologous system has been used previously to examine the role of PII-like proteins in modulating the activity of K. pneumoniae NifL in vivo (1, 12) and hence allows direct comparison of the properties of the A. vinelandii and K. pneumoniae nitrogen fixation regulatory genes.

In contrast to the observations made with the equivalent K. pneumoniae NifL-NifA regulatory components (1, 12, 14), our data demonstrate clearly that the E. coli PII paralogues are not required to prevent A. vinelandii NifL from inhibiting NifA. This conclusion is based on the observation that under nitrogen-limiting conditions, the activity of NifA in the presence of NifL does not decrease in the glnB glnK and glnB glnK ntrC mutant strains, which do not express either of the PII paralogues. Rather, the circumstantial evidence presented here suggests that under nitrogen-limiting conditions, 2-oxoglutarate may be required to alleviate inhibition of NifA activity by NifL, in agreement with our in vitro observations (20). Whereas in the K. pneumoniae system, GlnK is absolutely required to relieve inhibition by NifL, it would appear that the PII paralogues have the opposite role to increase the activity of A. vinelandii NifL under conditions of nitrogen excess. Hence, although both the K. pneumoniae and A. vinelandii NifL-NifA systems are responsive to fixed nitrogen in E. coli, the mechanism for this response is fundamentally different in each case.

Although the nitrogen response of A. vinelandii NifL in E. coli could be dependent solely on the level of 2-oxoglutarate, the requirement for the PII proteins to increase the inhibitory activity of NifL under nitrogen-excess conditions would allow a more highly tuned response. Our in vitro experiments show that the nonmodified form of E. coli PII and Av PII can increase the inhibitory activity of NifL, whereas E. coli GlnK is ineffective (20). Thus, E. coli PII is apparently functionally analogous to Av PII with respect to its interaction with the A. vinelandii NifL-NifA system. The involvement of Av PII in increasing the inhibitory function of NifL is also suggested from genetic evidence with A. vinelandii, since glnD mutants which have lost the ability to fully uridylylate Av PII are Nif (8, 29). Furthermore, a mutation in A. vinelandii glnK which prevents uridylylation of the target tyrosine residue in the T loop of Av PII is also Nif−. Both of these mutant classes can be suppressed by insertion mutations in nifL (8, 29; P. Rudnick and C. Kennedy, unpublished results). This is in accord with our in vitro data which show that uridylylation of Av PII prevents it activating the inhibitory function of NifL (20).

Why are the mechanisms of the nitrogen response radically different between A. vinelandii with K. pneumoniae? One possibility lies in the differences between the C-terminal domains of the NifL counterparts (4, 38). The C-terminal domain of A. vinelandii NifL is homologous to the histidine protein kinase family, and although this protein does not exhibit kinase activity, it does bind adenosine nucleotides, particularly ADP, which is required to form the inhibitory NifL-NifA complex (32). In contrast, the C-terminal domain of K. pneumoniae NifL shows only limited homology to the histidine kinase family and has not been shown to interact with nucleotides. Although no extensive in vitro studies have been performed with the K. pneumoniae system, it is possible that K. pneumoniae NifL interacts with NifA irrespective of the presence of metabolites. This may impose the requirement for GlnK to destabilize the complex in order to achieve nitrogen regulation. In contrast in the A. vinelandii system, formation of the inhibitory complex is influenced by metabolite concentrations (ADP and 2-oxoglutarate) and the nonmodified form of PII stabilizes the complex. These differences reveal the considerable versatility of the PII signal transduction proteins in their mode of interaction with receptors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Gavin Thomas for strain GT1002, Paul Rudnick and Christina Kennedy for informing us of their unpublished results, and Mike Merrick for comments on the manuscript. F.R.-R. was supported by Marie Curie Training Fellowship FMBICT983125 from the European Community. R.L. and R.D. were supported by the BBSRC Competitive Strategic Grant to the John Innes Centre.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arcondéguy T, van Heeswijk W C, Merrick M. Studies on the roles of glnK and glnB in regulating Klebsiella pneumoniae NifL-dependent nitrogen control. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;180:263–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb08805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkinson M R, Ninfa A J. Characterization of the GlnK protein of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:301–313. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atkinson M R, Ninfa A J. Role of the GlnK signal transduction protein in the regulation of nitrogen assimilation in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:431–447. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanco G, Drummond M, Woodley P, Kennedy C. Sequence and molecular analysis of the nifL gene of Azotobacter vinelandii. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:869–880. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buck M, Gallegos M T, Studholme D J, Guo Y, Gralla J D. The bacterial enhancer-dependent ς54 (ςN) transcription factor. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4129–4136. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.15.4129-4136.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bueno R, Pahel G, Magasanik B. Role of glnB and glnD gene products in regulation of the glnALG operon of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1985;164:816–822. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.2.816-822.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Y-M, Backman K, Magasanik B. Characterization of a gene, glnL, the product of which is involved in the regulation of nitrogen utilization in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1982;150:214–220. doi: 10.1128/jb.150.1.214-220.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Contreras A, Drummond M, Bali A, Blanco G, Garcia E, Bush G, Kennedy C, Merrick M. The product of the nitrogen fixation regulatory gene nfrX of Azotobacter vinelandii is functionally and structurally homologous to the uridylyltransferase encoded by glnD in enteric bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7741–7749. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.24.7741-7749.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dixon R, Austin S, Eydmann T, Hill S, Kim S-O, Macheroux P, Poole R, Reyes-Ramirez F, Sobzcyk A, Söderbäck E. Regulation of nif gene expression in free-living diazotrophs: recent advances. In: Elmerich C, Kondorosi A, Newton W, editors. Biological nitrogen fixation in the 21st century. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1998. pp. 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dixon R. The oxygen-responsive NIFL-NIFA complex: a novel two-component regulatory system controlling nitrogenase synthesis in γ-Proteobacteria. Arch Microbiol. 1998;169:371–380. doi: 10.1007/s002030050585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards R, Merrick M. The role of uridylyltransferase in the control of Klebsiella pneumoniae nif gene regulation. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;247:189–198. doi: 10.1007/BF00705649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He L, Soupene E, Ninfa A, Kustu S. Physiological role for the GlnK protein of enteric bacteria: relief of NifL inhibition under nitrogen-limiting conditions. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6661–6667. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6661-6667.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holtel H, Merrick M. Identification of the Klebsiella pneumoniae glnB gene: nucleotide sequence of wild-type and mutant alleles. Mol Gen Genet. 1988;215:134–138. doi: 10.1007/BF00331314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jack R, De Zamaroczy M, Merrick M. The signal transduction protein GlnK is required for NifL-dependent nitrogen control of nif gene expression in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1156–1162. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.4.1156-1162.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaggi R, van Heeswijk W C, Westerhoff H V, Ollis D L, Vasudevan S G. The two opposing activities of adenylyl transferase reside in distinct homologous domains, with intramolecular signal transduction. EMBO J. 1997;16:5562–5571. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.18.5562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang P, Ninfa A J. Regulation of autophosphorylation of Escherichia coli nitrogen regulator II by the PII signal transduction protein. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1906–1911. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.6.1906-1911.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang P, Peliska J A, Ninfa A J. Reconstitution of the signal-transduction bicyclic cascade responsible for the regulation of Ntr gene transcription in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1998;37:12795–12801. doi: 10.1021/bi9802420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang P, Peliska J A, Ninfa A J. The regulation of Escherichia coli glutamine synthetase revisited: role of 2-ketoglutarate in the regulation of glutamine synthetase adenylylation state. Biochemistry. 1998;37:12802–12810. doi: 10.1021/bi980666u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Link A J, Phillips D, Church G M. Methods for generating precise deletions and insertions in the genome of wild-type Escherichia coli: application to open reading frame characterization. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6228–6237. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6228-6237.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Little R, Reyes-Ramirez F, Zhang Y, Van Heeswijk W, Dixon R. Signal transduction to the Azotobacter vinelandii NIFL-NIFA regulatory system is influenced directly by interaction with 2-oxoglutarate and the PII regulatory protein. EMBO J. 2000;19:6041–6050. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.22.6041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowry O H, Carter J, Ward J B, Glaser L. The effect of carbon and nitrogen sources on the level of metabolic intermediates in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:6511–6521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowry O H, Passonneau J V. A flexible system of enzymatic analysis. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1972. pp. 78–82. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lowry O H, Rosenberg N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macneil T, Macneil D, Tyler B. Fine-structure deletion map and complementation analysis of the glnA-glnL-glnG region in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1982;150:1302–1313. doi: 10.1128/jb.150.3.1302-1313.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meletzus D, Rudnick P, Doetsch N, Green A, Kennedy C. Characterization of the glnK-amtB operon of Azotobacter vinelandii. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3260–3264. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.12.3260-3264.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merrick M, Edwards R. Nitrogen control in bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:604–622. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.4.604-622.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ninfa A, Atkinson M. PII signal transduction proteins. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:172–179. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01709-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pahel G, Tyler B. A new glnA-linked regulatory gene for glutamine synthetase in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4544–4548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rudnick P, Colnaghi R, Green A, Kennedy C. Molecular analysis of the glnB, amtB, glnD and glnA genes in Azotobacter vinelandii. In: Elmerich C, Kondorosi A, Newton W, editors. Biological nitrogen fixation in the 21st century. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1998. pp. 123–124. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Screen S, Watson J, Dixon R. Oxygen sensitivity and metal ion-dependent transcriptional activation by NIFA protein from Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar trifolii. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;245:313–322. doi: 10.1007/BF00290111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Senior P J. Regulation of nitrogen metabolism in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella aerogenes: studies with the continuous culture technique. J Bacteriol. 1975;123:407. doi: 10.1128/jb.123.2.407-418.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Söderbäck E, Reyes-Ramirez F, Eydmann T, Austin S, Hill S, Dixon R. The redox-and fixed nitrogen-responsive regulatory protein NifL from Azotobacter vinelandii comprises discrete flavin and nucleotide-binding domains. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:179–192. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas G, Coutts G, Merrick M. The glnKamtB operon. A conserved gene pair in prokaryotes. Trends Genet. 2000;16:11–14. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01887-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas G H, Mullins J G, Merrick M. Membrane topology of the Mep/Amt family of ammonium transporters. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:331–344. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tuli R, Merrick M J. Over-production and characterisation of the nifA gene product of Klebsiella pneumoniae—the transcription activator of nif gene expression. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:425–432. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-2-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Heeswijk W, Hoving S, Molenaar D, Stegeman B, Kahn D, Westerhoff H. An alternative PII protein in the regulation of glutamine synthetase in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:133–146. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.6281349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Heeswijk W C, Stegeman B, Hoving S, Molenaar D, Kahn D, Westerhoff H V. An additional PII in Escherichia coli: a new regulatory protein in the glutamine synthetase cascade. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;132:153–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woodley P, Drummond M. Redundancy of the conserved His residue in Azotobacter vinelandii nifL, a histidine protein kinase homologue which regulates transcription of nitrogen fixation genes. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:619–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]