Abstract

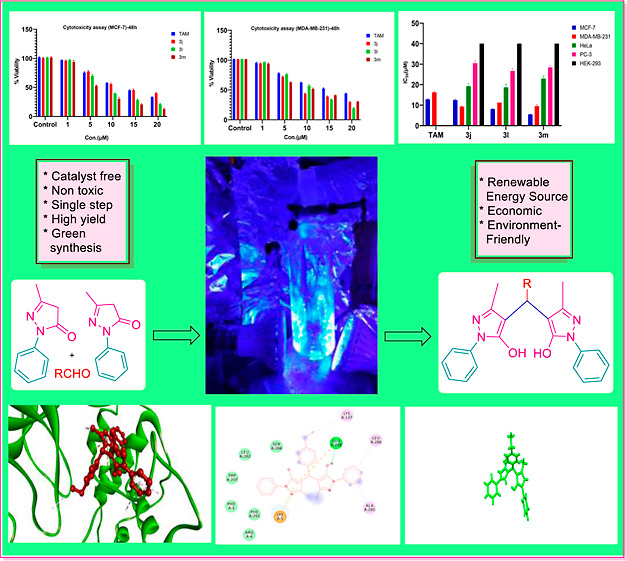

A visible light-promoted, efficient, green, and sustainable strategy has been adopted to unlatch a new pathway toward the synthesis of a library of medicinally important 4,4′-(arylmethylene)bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ols) moieties using substituted aromatic aldehydes and sterically hindered 3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazoline-5-one in excellent yield. This reaction shows high functional group tolerance and provides a cost-effective and catalyst-free protocol for the quick synthesis of biologically active compounds from readily available substrates. Synthesized compounds were characterized by spectroscopic techniques such as IR, 1HNMR, 13CNMR, and single-crystal XRD analysis. All the synthesized compounds were evaluated for their antiproliferative activities against a panel of five different human cancer cell lines and compared with Tamoxifen using MTT assay. Compound 3m exhibited maximum antiproliferative activity and was found to be more active as compared to Tamoxifen against both the MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines with an IC50 of 5.45 and 9.47 μM, respectively. A molecular docking study with respect to COVID-19 main protease (Mpro) (PDB ID: 6LU7) has also been carried out which shows comparatively high binding affinity of compounds 3f and 3g (−8.3 and −8.8 Kcal/mole, respectively) than few reported drugs such as ritonavir, remdesivir, ribacvirin, favipiravir, hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, and olsaltamivir. Hence, it reveals the possibility of these compounds to be used as effective COVID-19 inhibitors.

Introduction

In the past few years, visible light-mediated photoredox catalysis became apparent as one of the most fascinating and robust research strategies in synthetic organic chemistry. This particularly advance area of photochemistry has drawn fair attention of organic chemists due to its more appealing attributes such as no heating, mild reaction condition, nontoxicity, trouble-free workup and handling, cost-effectiveness, abundantly availability, renewable energy source, and environmentally benign nature which further add to sustainable green chemistry.1,2 Harvesting, photons of visible light for organic conversions, covering C–C or C–H bond formation, oxidation, reduction, and many more through single electron transfer reaction (SET) of electronically excited molecules, lead to generate various chemical pathways to bring about selective molecular complexity of interest in simple target molecules.2a,2b,2e,2f,3−8 Hence, visible light photocatalysis can play a vital role in the formation of complex drug moieties under lenient reaction conditions, which unlatches its application in medicinal and pharmaceutical areas. Consequently, the application of visible light for rapid target oriented synthesis required to be combined with some atom economical and highly efficient synthetic methodologies with a profound selectivity such as multicomponent reactions (MCRs) which can play an important role while applying visible light in synthetic organic chemistry.

Lately, MCRs have made an appearance as a sturdy tool in organic synthesis.9 With the help of MCRs, the abovementioned purpose is better achieved by combining three or more reactants on a single step which results into product formation. MCRs have emerged as a fast growing field as they put forward a number of advantages over conventional methods such as one-pot, straightforward, convergent, low cost effective, reduced step, high reaction efficiency, high selectivity10 and molecular diversity, high atom economical,9e,9g,11 and hence environmentally friendly.12−15 This combination of MCRs with visible light-promoted synthesis further adds up to the advancement in medicinal chemistry and new drug discovery.9g,13a,16 N-containing heterocyclic compounds are of special biological and medicinal importance and therefore assume a fundamental part in natural science.

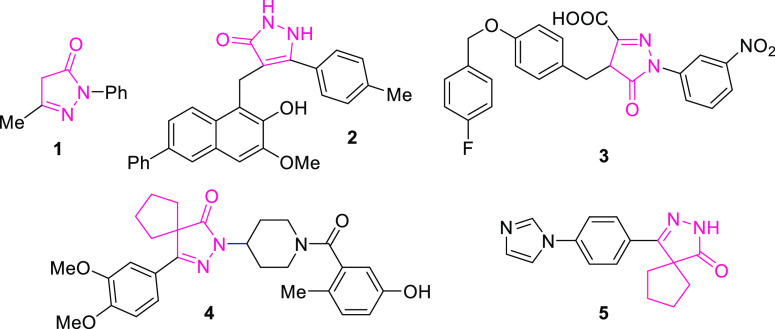

Among the wide range of five-membered aza-heterocycles, pyrazolones have drawn in extensive consideration in view of their scope as possible drug specialists and engineered scaffolds.17 Thus, pyrazolones and their bis-derivatives have been given a lot of contemplation for their different natural exercises such as antitumor,18 antiviral,19 antibacterial,20 antiinflammatory,21 antidepressant,22 antipyretic,23 antifilarial agents,24 gastric discharge stimulatory,25 and particular COX-2 inhibitory.26 Besides, these moieties are utilized as dyes,27 ligands in coordination chemistry,28 and metal ion extracting and purification agents.29−31 Different subsidiaries of pyrazoles, for example, 4,4’-(aryl methylene)bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ols), can be utilized as pesticides,32 fungicides,33 and insectisides.34 Some of their subordinates go about as the structural motif of some commercially approved drug for the treatment of different types of cancers,35c neuroprotective agent (1),35 sirtuin inhibitors (2),36 and HIV integrase inhibitors (3),37 whereas spiro derivatives of pyrazolones have shown a promising pharmacophore, that is, compounds (4)38 and (5)39 (Figure 1). Consequently, a number of protocols have been put resources into preparation of pyrazoles and pyrazolone derivatives during the past decades.40 Their conventional synthesis involves condensation reaction between aromatic aldehyde and pyrazolone moieties to perform tandem Knoevenagel–Michael reaction.41

Figure 1.

Few examples of biologically active pyrazolones.

A wide range of catalysts have been employed for such transformations including CTSA,42a THBS,42b PEGSO3H,29 lithium hydroxide monohydrate,42c cellulose sulfuric acid,42d pyridinium salt (1-carboxymethyl)pyridinium chloride {[cmpy]Cl},42e xanthan sulfuric acid,42f 2-hydroxyethylammonium acetate (HEAA),42g phosphomolybdic acid,42h 3-aminopropylated silica gel,42i [Et3NH][HSO4],42j silica-bonded S-sulfonic acid,42k 1-sulfopyridinium chloride,42l eletrocatalytic procedure,42m Na+-MMT-[pmim]HSO4,42n 2-hydroxyethylammonium propionate,42o ceric ammonium nitrate, cerium sulfate,42p melamine trisulfunicacid,42q sodium dodecyl sulfate,42r sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate (SDBS),42s zinc oxide nanowires,42t 1,3-disulfonic acid imidazoliumtetrachloroaluminate {[Dsim]AlCl4},42u piperidine, sodium lauryl sulfate or catalyst free (PEG-400),42v and ionic liquid [HMIM]HSO4 both under ultrasonic irradiation42w and reflux.42x Mono- and diphenylicbispyrazolones have also been reported.42y

Nonetheless, the abovementioned approaches have been suffering from a number of shortcomings such as economically high cost, poor yield, prolonged reaction time, tiresome workup, and toxic reaction condition or solvents and hence are environmentally unsafe. Therefore, we have adopted an entirely fresh and environmentally friendly strategy for the synthesis of this pharmacologically and medicinally important moiety using visible light as a natural and green source to catalyze this particular transformation. This strategy, being more versatile and easy to handle, out-performs the system we have today.

Results and Discussion

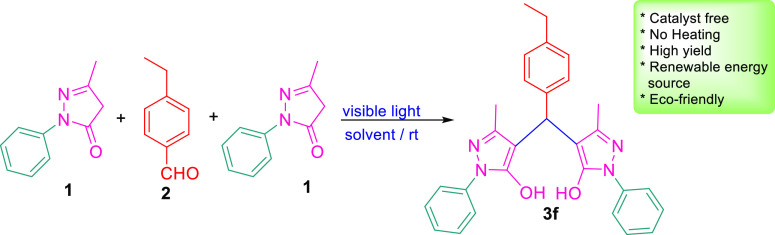

We have reported a series of one-pot pseudo multicomponent synthesis of 4,4́-(arylmethylene)bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ol) by reactions between substituted aldehydes (1 mmol) and 3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazoline-5-one (2 mmol) in the presence of visible light as an energy source at room temperature (Scheme 1). The role of visible light in progress of reaction, consumption of starting materials, that is, 3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazoline-5-one and aldehydes, and appearance of the product and finally completion of reaction was monitored by thin layer chromatography (TLC). The synthesis of compound 3f in the particular reaction condition is shown in Scheme S1. After completion of reaction in 3–5 h, we have obtained fair to excellent yield of products (3a–3r). All the synthesized compounds were identified and characterized by melting point (matched with the reported literature) and spectroscopic techniques such as IR, 1H NMR, and 13C NMR, and finally, the crystal structure was confirmed by single-crystal X-ray crystallographic analysis. Anticancer activity and molecular docking studies with respect to (Mpro) (PDB ID: 6LU7), which is present in COVID-19, have also been carried out.

Scheme 1. Optimization of Reaction Conditions for the Synthesis of 4,4́-(Arylmethylene)bs(1H-pyrazo-5-ol) From Different Aldehyde Derivatives and 3-Methyl-1-Phenyl-2-Pyrazoline-5-One.

To examine the optimization of reaction conditions, the reaction between 4-ethylbenzaldehyde(1 mmol) and 3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazoline-5-one (2 mmol) was selected as model reaction and investigated using under different visible light sources, utilizing blue-green and white LED bulbs of 24 W (Table 1). We found that the reaction proceeded well only under blue LED conditions and no change has been observed in green and red LEDs, while an unsatisfactory yield has been obtained in white light. Furthermore, the reaction has been tested in variant energy visible light conditions as well, using blue LED bulbs of power 12, 24, and 36 W (Table 1, entry 4–6). The best possible reaction performance with minimum energy consumption along with a desirable yield of 78% of product 3f was obtained under catalyst-free reaction conditions using blue LED bulbs (24 W) as a visible light source for 3 h (Table 1, entry 5).

Table 1. Optimization of Visible Light Conditions for Synthesis of Compound 3fa.

| entry | visible light source (LED bulb) | catalyst (mol %) | time (h) | %yieldb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | green (24 W) | catalyst free | 10 | no change |

| 2. | white (24 W) | catalyst free | 10 | 25 |

| 3. | red (24 W) | catalyst free | 10 | no change |

| 4. | blue (12 W) | catalyst free | 8 | 66 |

| 5. | blue (24W) | catalyst free | 3 | 78 |

| 6. | blue (36W) | catalyst free | 3 | 78 |

All reactions were completed under visible light at room temperature using methanol as the solvent.

Isolated yields.

Afterward, we set out the reaction screening under optimized visible light reaction conditions, with different solvents. The subsequent improvement in product yield observed was as follows: dichloromethane (28%), ethylacetate (32%), acetone (35%), chloroform (47%), DMF (60%), MeOH/H2O (1:1) (68%), and methanol (78%) (Table 2). In the presence of water as a solvent, the product was obtained in traces. The highest yield of 96% of the product 3f was acquired when the model reaction was performed utilizing ethanol as a solvent (Table 2).

Table 2. Optimization of the Solvent for the Synthesis of Compound 3fa.

| entry | solvent | time (h) | 1:2 (mmol) | %yieldb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | methanol | 5 | 1:2 | 78 |

| 2. | ethanol | 3 | 1:2 | 96 |

| 3. | acetonitrile | 10 | 1:2 | 62 |

| 4. | chloroform | 12 | 1:2 | 47 |

| 5. | acetone | 18 | 1:2 | 35 |

| 6. | H2O | 23 | 1:2 | traces |

| 7. | EtOAc | 18 | 1:2 | 32 |

| 8. | DCM | 18 | 1:2 | 28 |

| 9. | MeOH/H2O (1:1) | 8 | 1:2 | 68 |

| 10. | DMF | 8 | 1:2 | 60 |

Reaction conditions: 3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazoline-5-one (2 mmol) and 4-ethylbenzaldehyde (1 mmol) under blue LEDs at room temperature.

Isolated yields.

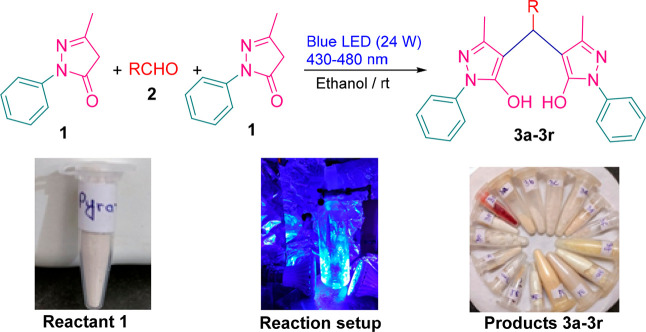

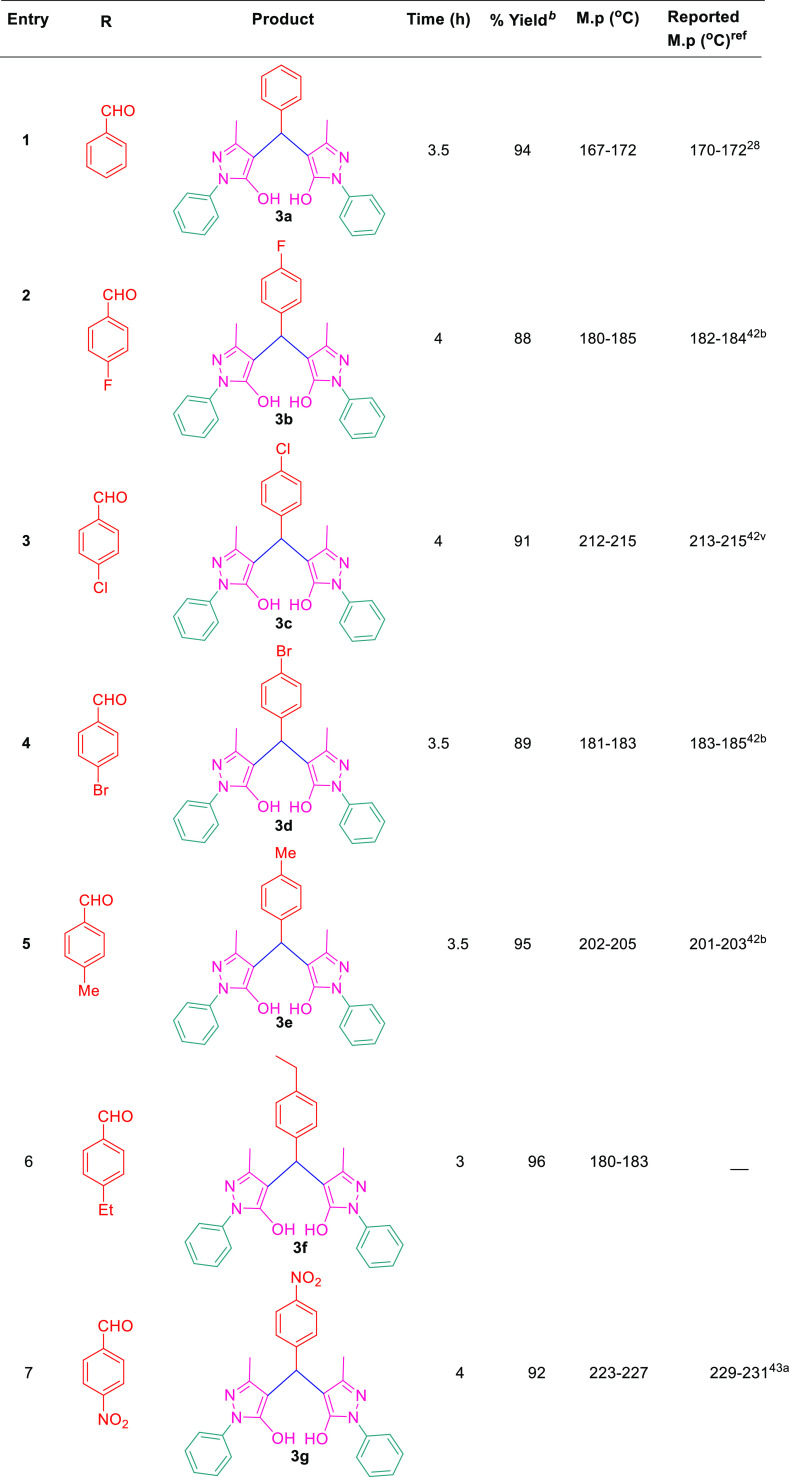

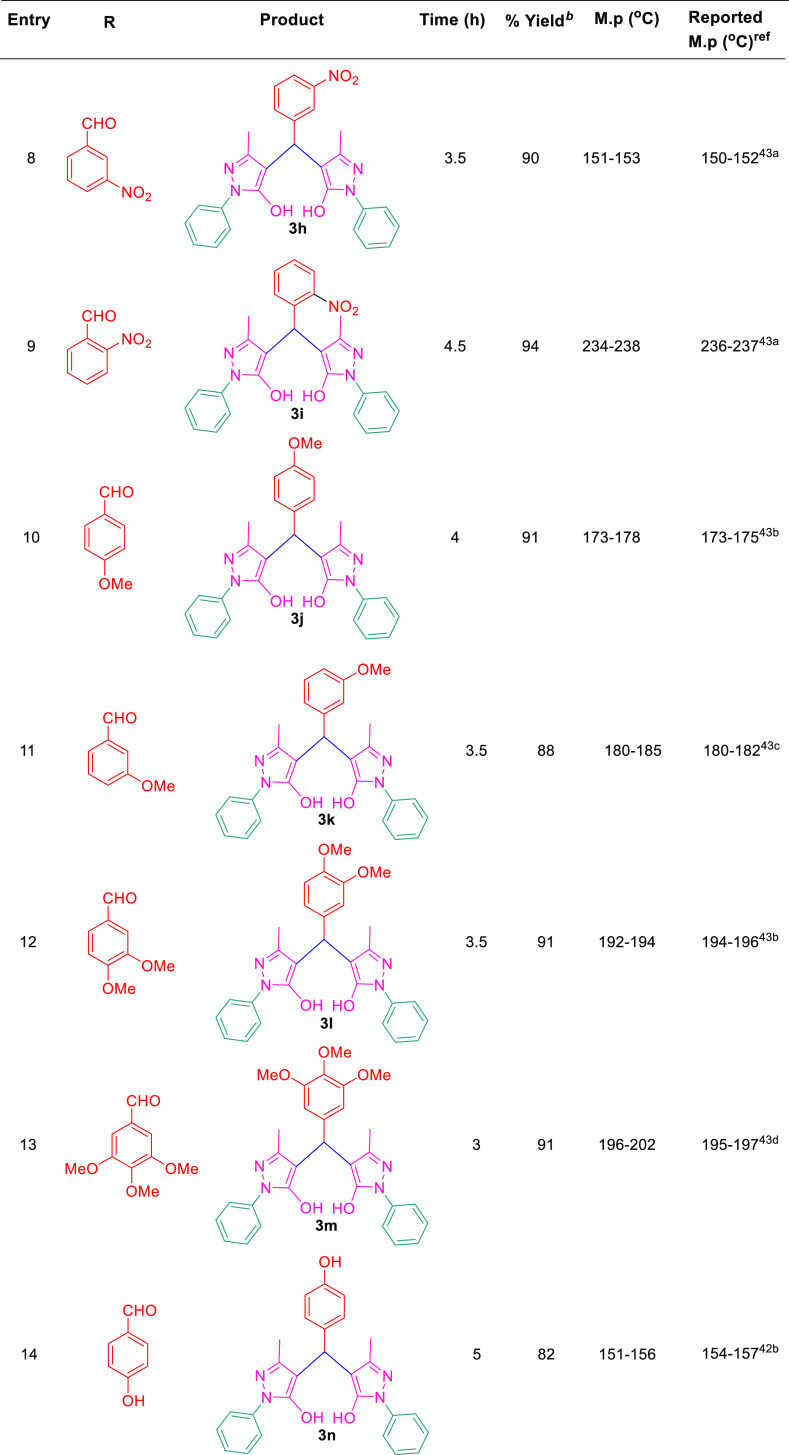

After setting the optimized reaction conditions, we have checked the generality of this protocol to generate various derivatives of 4,4′-(arylmethylene)bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ol) by exploring its substrate scope with differently substituted aldehydes including both aromatic aldehydes such as benzaldehyde(3a), 4-F (3b), 4-Cl (3c), 4-Br (3d), 4-Me (3e), 4-Et (3f), 4-NO2 (3g), 3-NO2 (3h), 2-NO2 (3i), 4-OMe (3j), 3-OMe (3k), 3,4-di-OMe (3l), 3,4,5-tri-OMe (3m), 4-OH (3n), 2-OH (3o), and N(CH3)2 (3q) and aliphatic aldehyde such as formaldehyde (3r) under optimized reaction conditions. For our interest, the reactions with aromatic aldehydes offered the desired products in an excellent yield of 82–96% in 3–5 h, whereas the aliphatic aldehyde, that is, HCHO, gave rise to the expected product with 78% yield in 6.5 h (Scheme 2 and Table 3). Similarly, our reaction was also investigated with thiophene-2-carboxaldehyde (C4H3SCHO) under the same reaction conditions, affording products (3p) in 92% yields, which further confirms the generality of the present protocol (Table 3). It is observed from the experimental results that the aromatic aldehydes afford the products smoothly with electron-donating groups and electron-withdrawing groups, and it is also noteworthy that the aldehydes with electron-donating groups undergo the reaction with faster rate as compared to the aldehydes with electron-donating groups.

Scheme 2. Substrate Scope of 4,4́-(Arylmethylene)bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ol) Under the Optimized Reaction Condition.

Table 3. Substrate Scope for Synthesis of 4,4′-(Arylmethylene)bis(1H-pyrazol-5-Ol).

All reactions were performed under blue visible light at room temperature.

Isolated yields.

Single-Crystal XRD Report

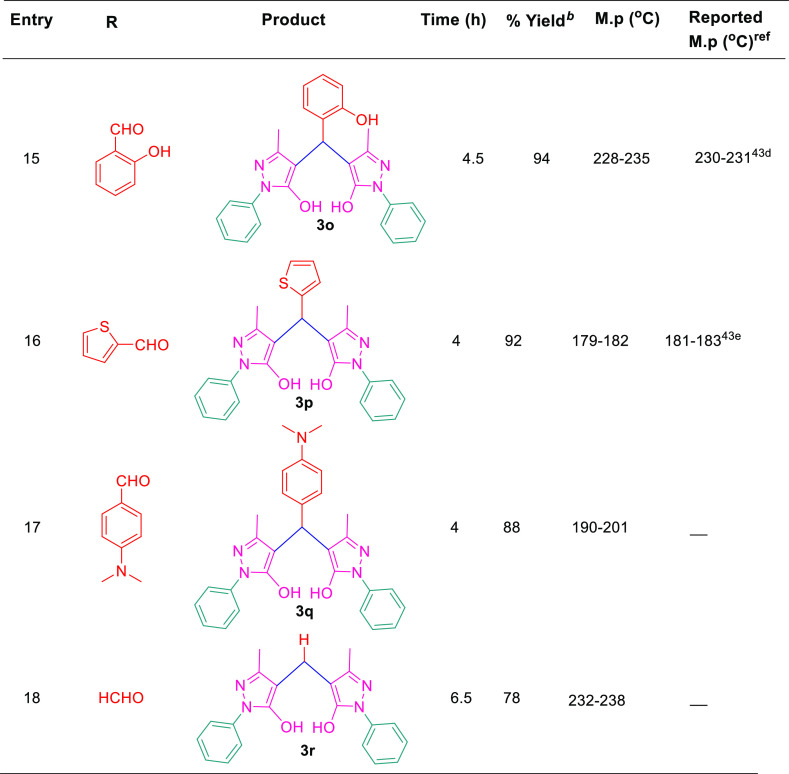

The single-crystal XRD study of the synthesized crystal of compound 3f validates its structure and stereochemistry (Figure 2 and Table S1). The ORTEP diagram of the compound 3f shows that in its crystal form, it consists of an in-plane 4-ethylphenyl ring and two 3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazole rings.

Figure 2.

Ortep diagram of compound 3f with CCDC 2178033.

Biological Activity

In vitro Antiproliferative Activities of Synthesized 4,4′-(Arylmethylene)bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ol) Derivatives

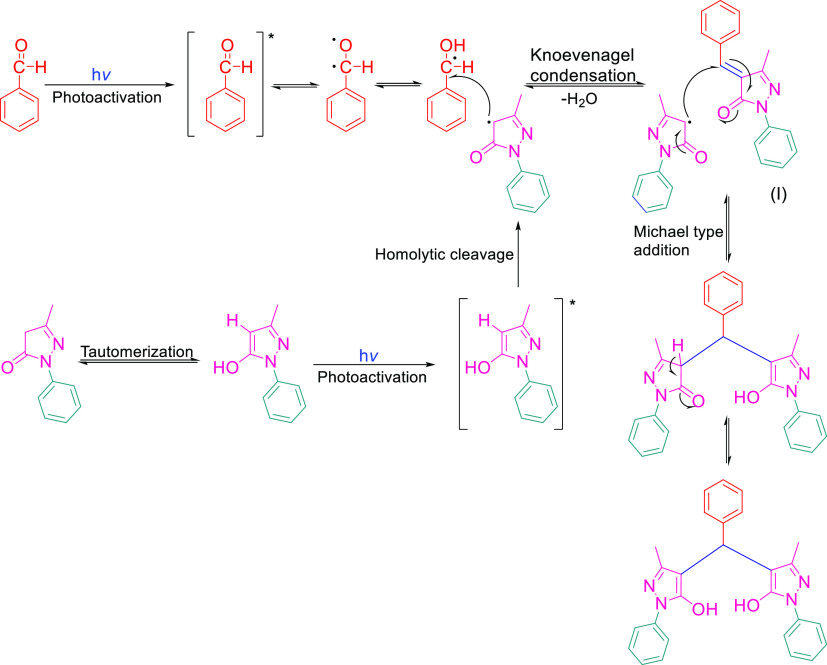

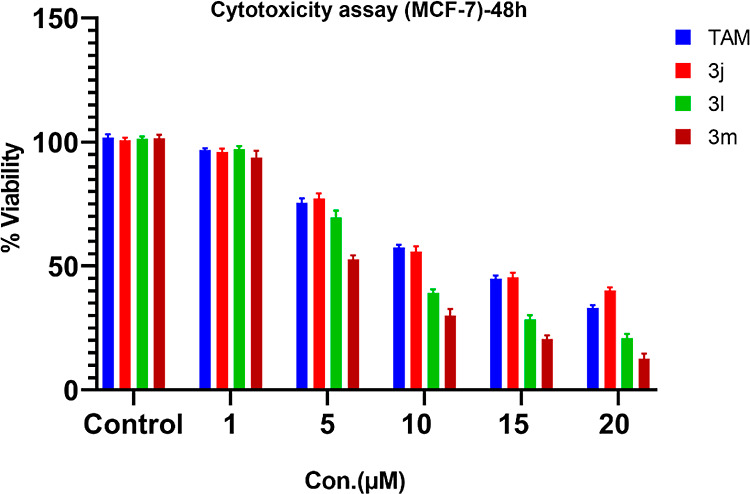

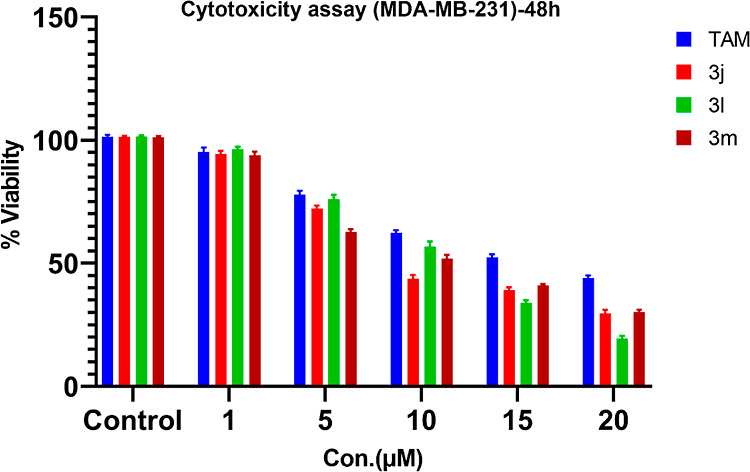

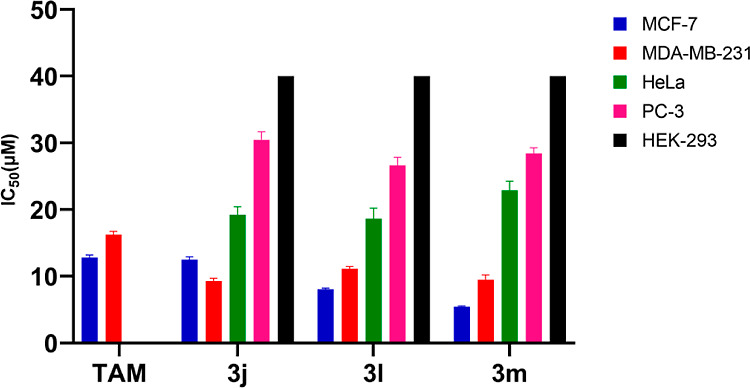

Pyrazole is a privileged scaffold in medicinal chemistry. Various pyrazole derivatives have been reported as potential anticancer agents. Pyrazoles play a crucial role in various disease areas, especially in many cancer types such as lymphoma, breast cancer, melanoma, and cervical cancer. Various studies have demonstrated the potent anticancer activity of pyrazole derivatives against breast cancer cell lines (MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231).44 Therefore, we selected MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines to check the potential anticancer activity of our synthesized library. Furthermore, we evaluated these compounds to explore their potential activity against cancer of other organs or tissues such as endometrial adenocarcinoma (Ishikawa), cervical cancer (Hela), and prostate cancer (PC-3). To achieve our purpose, all the synthesized 4,4′-(arylmethylene)bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ol) derivatives were evaluated in vitro for their anticancer activity against a panel of five different human cancer cell lines, breast cancer (MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231), cervical cancer (Hela cells), endometrial cancer (Ishikawa cell line), and prostate cancer cell lines (PC-3) and compared with Tamoxifen (TAM) using MTT assay (Figure 3 and 4).45 Tamoxifen45b,45c,46 is an effective therapy used to treat estrogen receptor-positive (ER + Ve) breast cancer. Therefore, we selected Tamoxifen as a positive control drug to compare the activity with synthesized compounds against ER + Ve cancer cell lines (MCF-7). The IC50 value of Tamoxifen varies from 7.6 to 13.7 μM against MCF-7 cells and 9.86 to 17.9 μM against MDA-MB-231. The compounds synthesized were also tested for toxicity in normal human embryonic kidney cell line HEK-293, and all of them were found to be nontoxic to the normal cells (IC50 > 40 μM). Most of the compounds exhibited excellent to mild activity against various cancer cell lines (IC50 = 5.45 to 38.84 μM). Five compounds 3b, 3c,3j, 3l, and 3m displayed excellent antiproliferative activity against various cancer cell lines ((IC50 = 5.45 to 18.26 μM). Compound 3m showed maximum antiproliferative activity and was found more active as compared to Tamoxifen against both the MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines with an IC50 of 5.45 and 9.47 μM, respectively. Compound 3j efficiently inhibited the proliferation of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines (IC50 = 12.46 and 9.28 μM), while compound 3l showed antiproliferative activity against both breast cancer cells with IC50 of 8.05 and 11.12 μM, respectively. Furthermore, these compounds (3j and 3l) were also found more active as compared to anti-breast cancer drug Tamoxifen (IC50 = 12.80 and 16.25μM) against MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines, respectively. Compounds 3j, 3l, and 3m also exhibited mild antiproliferative activity against HeLa cancer cell lines and weak activity against PC-3 cell lines. Similarly, compound 3c showed good inhibition against MCF-7 cell lines (IC50 = 16.26 μM) and mild inhibition against MDA-MB-231 with an IC50 of 22.44 μM. Compound 3c exhibited weak antiproliferative activity against HeLa and Ishikawa cell lines. Compound 3a displayed weak inhibition against MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, and HeLa cell lines. Compound 3b showed good antiproliferative activity against MDA-MB-231cells (IC50 = 18.24 μM) and weak activity againstMCF-7, PC-3, and Ishikawa cell lines. Compounds 3f–i and 3o–q showed weak inhibition against MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, and HeLa cell lines. The rest of the compounds showed weak or no inhibition against the concerned cell lines (Table 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 3.

Cytotoxicity assay of some active 4,4′-(arylmethylene)bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ol) derivatives in MCF-7 cells. Cell lines were treated with (0, 1, 5, 10, 15, and 20 μM) for 48 h, after which the cell viability was measured by MTT assay; results are expressed as mean ± SEM; N = 4, at all concentrations of TAM, 3j–3m, p values are p < 0.05 but p > 005 control vs 1 μM TAM, for 3j, 10 μM vs. 15 μM.

Figure 4.

Cytotoxicity assay of some active 4,4’′-(arylmethylene)bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ol) derivatives in MDA-MB-231 cells. Cell lines were treated with (0, 1, 5, 10, 15, and 20 μM) for 48 h, after which the cell viability was measured by MTT assay; results are expressed as mean ± SEM; N = 4, p values are p < 0.05.

Table 4. In vitro Antiproliferative Activity of 4,4′-(Arylmethylene)bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ol) Derivatives Against Various Cancer Cell Lines.

| activity in terms of IC50 (Mean ± SEM, in μM) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S.no | product code | MCF-7 | MDA-MB-231 | HeLa | PC-3 | Ishikawa | HEK-293 |

| 1. | 3a | 35.07 ± 1.38 | 30.82 ± 1.49 | 30.74 ± 1.38 | >40 | 30.24 ± 2.12 | >40 |

| 2. | 3b | 28.46 ± 2.24 | 18.24 ± 1.68 | 36.80 ± 2.34 | 35.86 ± 1.32 | 38.24 ± 2.13 | >40 |

| 3. | 3c | 16.26 ± 0.62 | 22.44 ± 1.34 | 32.40 ± 1.62 | >40 | 36.85 ± 1.38 | >40 |

| 4. | 3e | 30.36 ± 1.24 | 28.28 ± 1.31 | 38.41 ± 1.22 | 28.48 ± 1.43 | >40 | >40 |

| 5. | 3f | 38.36 ± 1.29 | 38.46 ± 1.21 | 28.84 ± 1.34 | 30.62 ± 1.22 | >40 | >40 |

| 6. | 3g | 35.64 ± 1.36 | 39.56 ± 2.32 | 38.32 ± 2.32 | 35.38 ± 2.12 | >40 | >40 |

| 7. | 3h | 32.46 ± 1.70 | 26.34 ± 1.52 | 32.40 ± 1.33 | 30.34 ± 1.21 | 32.78 ± 1.27 | >40 |

| 8. | 3i | 35.84 ± 2.34 | 39.38 ± 1.52 | 39.24 ± 1.28 | >40 | >40 | >40 |

| 9. | 3j | 12.46 ± 0.46 | 9.28 ± 0.42 | 19.20 ± 1.23 | 30.48 ± 2.38 | >40 | >40 |

| 10. | 3l | 8.05 ± 0.17 | 11.12 ± 0.33 | 18.64 ± 1.12 | 26.62 ± 2.44 | >40 | >40 |

| 11. | 3m | 5.45 ± 0.11 | 9.47 ± 0.57 | 22.86 ± 1.38 | 28.44 ± 1.66 | >40 | >40 |

| 12. | 3o | 30.18 ± 1.12 | 24.25 ± 1.24 | 35.44 ± 1.72 | >40 | >40 | >40 |

| 13. | 3p | 28.18 ± 1.22 | 36.80 ± 1.45 | 30.82 ± 1.27 | >40 | >40 | >40 |

| 14. | 3q | 32.64 ± 0.65 | 26.44 ± 1.12 | 39.32 ± 2.36 | >40 | >40 | >40 |

| 15. | TAM | 12.80 ± 0.38 | 16.25 ± 0.47 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

Figure 5.

Graphical representation of calculated IC50 values for the selected active compounds (3j, 3l, and 3m) and TAM, against a panel of five cancerous and normal cell lines. Compounds showed an IC50 value of more than 40 μM HEK-293cell lines; hence, to plot a graph of the IC50 value against the selected compounds, we considered the value of 40 μM as IC50. In the case of the standard drug (TAM), the experiment was not performed against Hela PC- 3, Ishikawa cell lines, and HEK-293 cells.

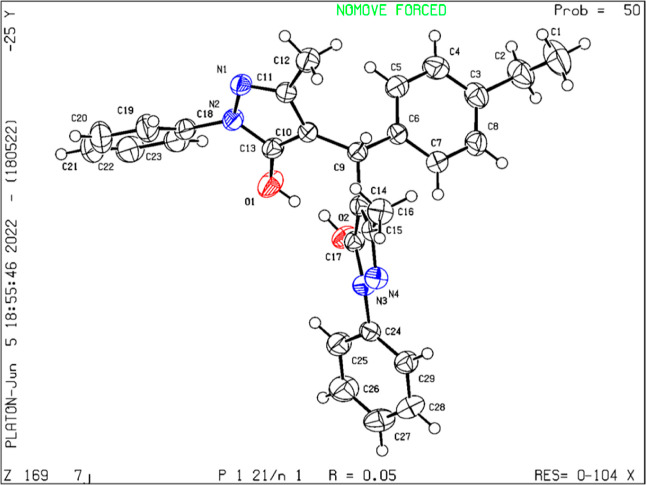

Structural Activity Relationship

Structural activity relationship of synthesized bispyrazole derivatives may be described based on the nature of the substituents attached to the phenyl ring A derived from aromatic aldehyde (Figure 6). In general, compounds (3b, 3c, and 3j–3m) having halogen atoms (F and Cl) or OMe functionalities at the para position of ring A exhibited better activities as compared to other compounds having Me, Et, and NMe2 at the para position (3e–3f and 3q), NO2 at the para, meta, and ortho position (3g–3i), and OH at the ortho position (3o) of ring A.

Figure 6.

Structural activity relationship of bis-pyrazole derivatives against MCF-7 cell lines.

Introduction of the OMe functionality at meta position along with para position greatly enhanced the activity against all the cancer cell lines (3l and 3m).Replacement of aryl ring A with the 2-thienyl moiety (3p) slightly enhanced the anticancer activity as compared to compound 3a.

Molecular Docking Studies with COVID-19 Mpro

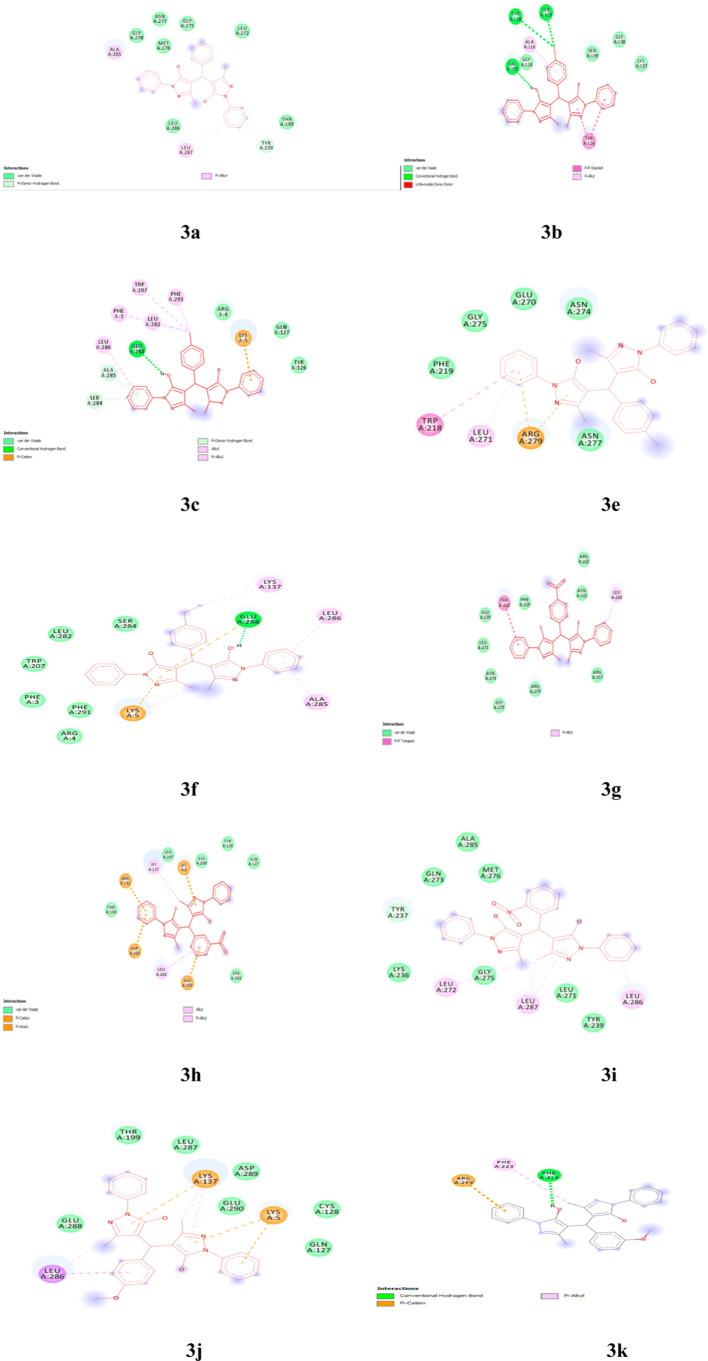

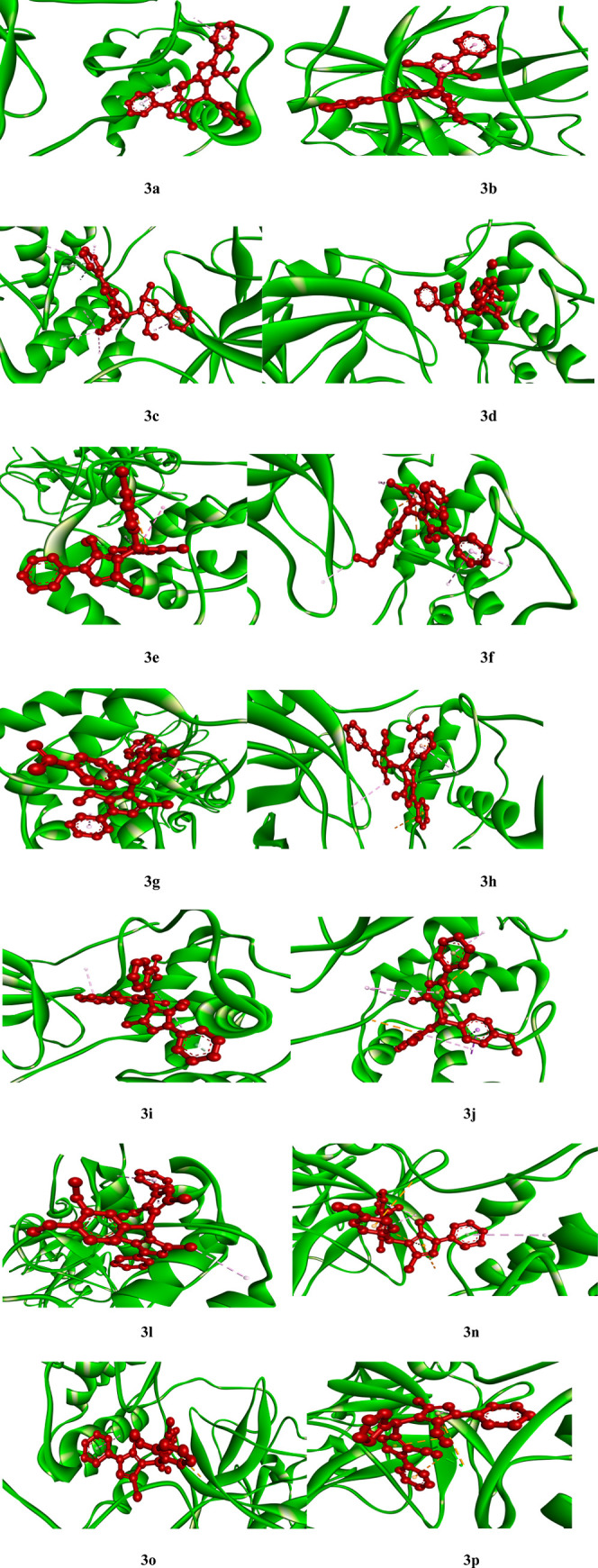

Various pyrazole-based drugs such as Ruxolitinib have been reported to possess anticancer activity. Ruxolitinib is an important pyrazole-based drug and has been reported to possess anticancer activity. Ruxolitinib showed anticancer effects in estrogen receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer cells.47 Regarding COVID-19, ruxolitinib was recently repurposed to quell the immune-hyper activation, thus dampening the cytokine storm. An artificial intelligence-driven study has identified ruxolitinib as a promising drug for COVID-19.48 Other than ruxotinib, several pyrazole-containing moieties have been reported to show anticancer49 and coronavirus inhibitory50 effects. Considering these facts and the havoc like situation created by the COVID-19 pandemic throughout the world prompted us to check the theoretical effectiveness of synthesized compounds as drug toward COVID-19 treatment as well. The cysteine protease, that is, main protease Mpro present in SARS-CoV-2, was found to be responsible for viral replication and transcription and hence proved to be a main drug target.51 Therefore, computational analysis has been carried out to check the possibility of all the synthesized compounds as inhibitors toward COVID-19. For this purpose, we used molecular docking to find out the type of interactions and the binding affinities between all the synthesized ligands withCOVID-19 main protease in complex with inhibitor N3, that is, Mpro(PDB ID: 6LU7)52 (in silico). The resulting binding affinities of all the ligands along with the possible number of hydrogen bonds between ligands and 6LU7 are summarized in Table 5 and Figures 7 and 8. Comparative binding affinity of ligand 3g and few COVID-19 effective drugs such as ritonavir, remdesivir, ribacvirin, favipiravir, hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, and olsaltamivir has also been denoted (Table 6).

Table 5. Molecular Docking Result of 4,4′-(Aryl methylene)bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ol) Derivatives With COVID-19 (Mpro) (PDB ID: 6LU7) Protein.

| entry | compound | binding energy (Kcal/mol) | no of H-bonds |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 3a | –7.8 | 1 |

| 2. | 3b | –7.4 | 3 |

| 3. | 3c | –8.0 | 3 |

| 4. | 3d | –8.0 | – |

| 5. | 3e | –6.8 | 0 |

| 6. | 3f | –8.3 | 1 |

| 7. | 3g | –8.8 | 0 |

| 8. | 3h | –7.7 | 0 |

| 9. | 3i | –8.0 | 1 |

| 10. | 3j | –7.6 | 0 |

| 11. | 3k | –7.8 | 1 |

| 12. | 3l | –6.1 | 1 |

| 13. | 3m | –8.0 | 1 |

| 14. | 3n | –8.0 | 0 |

| 15. | 3o | –7.5 | 0 |

| 16. | 3p | –8.1 | 2 |

| 17. | 3q | –8.2 | 0 |

Figure 7.

3D molecular docking models showing interaction of synthesized ligands with COVID-19 (Mpro) (PDB ID: 6LU7).

Figure 8.

2D representation of different interacting modes of synthesized ligands with COVID-19 (Mpro) (PDB ID: 6LU7).

Table 6. Comparative Study of Binding Affinity of Ligand 3g and Few Covid Effective Drugs.

| Sr. no. | compound | binding affinity (Kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | 3g | –8.8 |

| 2. | 3f | –8.3 |

| 3. | ritonavir53 | –7.3 |

| 4. | remdesivir53 | –6.5 |

| 5. | ribacvirin53 | –5.6 |

| 6. | favipiravir53 | –5.4 |

| 7. | hydroxychloroquine53 | –5.3 |

| 8. | chloroquine53 | –5.1 |

| 9. | olsaltamivir53 | –4.7 |

Ligand 3a shows pi-donor hydrogen binding interaction with amino acid Tyr-239 and pi-alkyl hydrophobic binding interaction with amino acids Ala-285 and Leu-287. The ligand 3b shows a binding affinity of −7.4 Kcal/mole, while the ligands 3c, 3d, 3i, and 3n show an equivalent binding energy of −8.0 Kcal/mole, which is summarized in Table 5. The ligand 3i shows pi-donar hydrogen bonding interaction with amino acid Tyr-237 and alkyl/pi-alkyl hydrophobic bonding interaction with amino acids Leu-272, Leu-286, and Leu-287 at the active center of 6LU7. Ligands 3e and 3l show lower binding interactions (−6.8 and −6.1 Kcal/mole, respectively) at the active site of 6LU7. The ligand 3e shows pi-cation binding interaction with amino acid Arg-279, pi–pi T-shaped binding interaction with amino acid Trp-218, and pi-alkyl hydrophobic binding interaction with amino acid Leu-271, whereas ligand 3f shows excellent binding interaction (−8.3 Kcal/mole) with COVID-19 Mpro and shows more binding interaction such as conventional hydrogen binding with amino acid Glu-288, pi-cation and pi-anion binding with amino acids Lys-5 and Glu-288, and alkyl/pi-alkyl hydrophobic binding with amino acids Lys-137, Ala-285, and Leu-286.

The ligands 3h and 3o showed nearby binding affinities of −7.7 and −7.5 Kcal/mole, respectively. The ligand 3j shows pi-cation binding interaction with amino acids Lys-5 and Lys-137, pi-sigma binding interaction with amino acid Leu-286, and alkyl and pi-alkyl hydrophobic binding interaction with amino acids Lys-137 and Leu-286. The ligand 3k displayed a binding affinity of −7.8Kcal/mole with COVID-19 Mpro and forms one conventional hydrogen binding with amino acid Phe-219, one pi-cation binding with amino acid Arg-279, and one pi-alkyl hydrophobic with amino acid Phe-223, while another ligand 3m shows a binding affinity of −8.0 Kcal/mole involving one hydrogen bonding with amino acid Leu-220 and two hydrophobic pi-alkyl interactions with amino acids Phe-223 and Leu-271. In the meanwhile, ligand 3p interacts with COVID-19 Mpro with a binding affinity of −8.1 Kcal/mole with two conventional hydrogen binding interaction with amino acid Glu-288, three pi-cation and pi-anion hydrogen binding interaction with amino acids Lys-5, Glu-288, and Glu-290, and alkyl and pi-alkyl hydrophobic interaction with amino acid Lys-5. The ligand 3q forms one pi-cation bonding with amino acid Agr-222 and two pi-alkyl hydrophobic bonds with amino acids Phe-223 and Arg-222.

It is interesting to note that the ligands 3f and 3g having Et and NO2 groups at para position show comparatively very high binding affinity values (−8.3 and −8.8 Kcal/mole, respectively) than the remaining ligands and few reported drugs such as ritonavir, remdesivir, ribacvirin, favipiravir, hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, and olsaltamivir (Table 6). Hence, compounds 3f and 3g could prove to be more effective drugs as COVID-19 inhibitors.

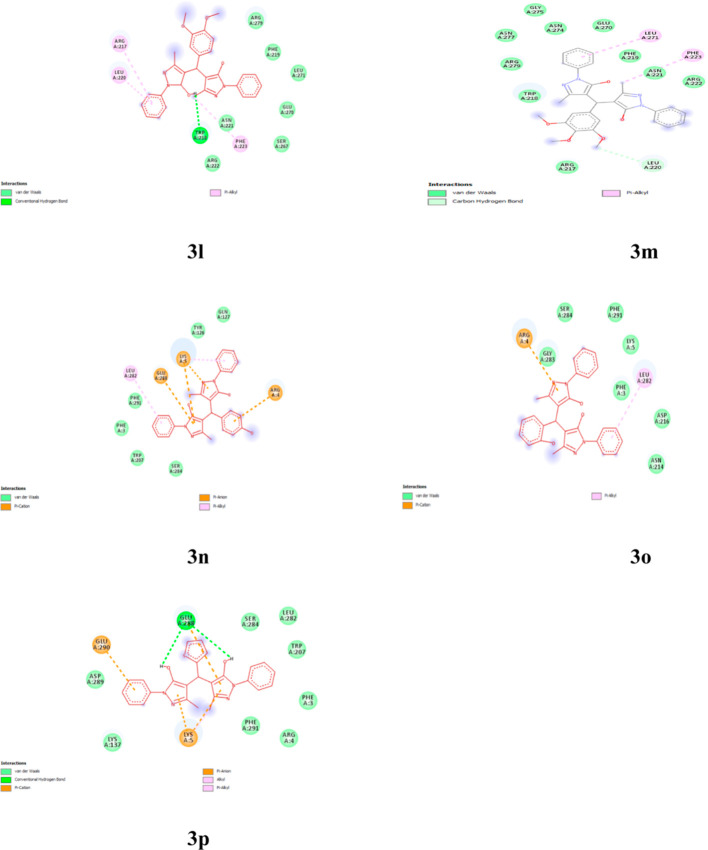

Plausible Mechanism

The plausible mechanistic pathway for this protocol has been shown (Scheme 3) in accordance to the previously reported radical mechanism.54 The mechanism represents the first activation of aldehyde by visible light irradiation where the carbonyl group of aldehyde is photochemically excited to undergo Norrish-type cleavage to give rise to a benzoyl or α-hydroxybenzyl radical. In the meantime, 3-methyl-1-phenyl(1H)-pyrazol-5(4H)-one undergoes keto–enol tautomerism. The photoinduced excited molecule of 3-methyl-1-phenyl(1H)-pyrazol-5(4H)-one then undergoes radical formation by homolytic cleavage at active methylene carbon which further participates into bond formation with the benzoyl radical by knoevenagel condensation with elimination of a water molecule and leads to a benzylidene intermediate (I). Furthermore, the second excited molecule of the enolic form of 3-methyl-1-phenyl(1H)-pyrazol-5(4H)-one gets added to the activated benzylidine intermediate (I) to give rise to the final product.43,53

Scheme 3. Plausible Mechanistic Pathway for Synthesis of 4,4′-(Arylmethylene)bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ol).

A quantum yield higher than 1 was obtained for model photochemical reaction forming product 3f (Scheme 1), supporting the involvement of a radical chain mechanism as the main reaction pathway. Radical trapping experiment with an efficient radical scavenger and a radical mechanism indicator 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy (TEMPO)55 also authenticates the radical nature of this reaction. The reaction was inhibited, and even after prolonged irradiation, progress of the reaction was nil as checked by a co-TLC; also, most reaction constituents were recovered after a chromatographic purification. This observation further reveals the involvement of a radical process in the reaction mechanism.

Conclusions

The present protocol demonstrated the utilization of visible light for catalyst-free one-pot pseudo-multicomponent synthesis of 4,4′-(aryl methylene)bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ols) and offers a number of advantages over conventional synthesis such as catalyst-free, nontoxic, short reaction time, easy workup and purification process, inexpensive, and abundant and renewable source of energy, which further adds more to the economic value and environmentally benign reaction conditions. The reaction shows high generality and functional group tolerance. It provides a direct approach for the generation of a library of diverse and potential anticancer agents. All the synthesized compounds were evaluated for their antiproliferative activities against various human breast cancer cell lines. Compound 3m exhibited significant antiproliferative activity and was found more active as compared to the well-known anti-breast cancer drug (Tamoxifen) against both the MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines with an IC50 of 5.45 and 9.47 μM, respectively. Based on the abovementioned investigations, compound 3m has been identified as a potential lead for the development of more potent anti-breast cancer agents. Molecular docking study with respect to COVID-19 main protease (Mpro) (PDB ID: 6LU7) has also been carried out which shows comparatively high binding affinity of compounds 3f and 3g (−8.3 and −8.8 Kcal/mole, respectively) than few reported drugs such as ritonavir, remdesivir, ribacvirin, favipiravir, hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, and olsaltamivir. All the results clearly render the approach very attractive in both organic synthesis and in pharmaceutical industry due to their biological importance.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the UGC, New Delhi, for providing financial support. We are thankful to USIF, AMU and SAIF, PU, Chandigarh for providing analytical facilities. The authors are also grateful to the chairman of Department of Chemistry, AMU, Aligarh, for providing basic infrastructures and other necessary facilities.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c04506.

Procedure of synthesis, melting point, IR data, and copies of 1HNMR, 13CNMR, and single-crystal XRD data of compounds synthesized (PDF).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

This paper was published ASAP on September 14, 2022, with an error in Scheme 2. The corrected version was reposted on September 27, 2022.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Prier C. K.; Rankic D. A.; MacMillan W. C. Visible Light Photoredox Catalysis with Transition Metal Complexes: Applications in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 5322. 10.1021/cr300503r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Xuan J.; Lu L.-Q.; Chen J.-R.; Xiao W.-J. Visible-Light-Driven Photoredox Catalysis in the Construction of Carbocyclic and Heterocyclic Ring Systems. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 2013, 6755. 10.1002/ejoc.201300596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Chen J.-R.; Hu X.-Q.; Lu L.-Q.; Xiao W.-J. Visible Light Photoredox-controlled Reactions of N-radicals and Radical Ions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 2044. 10.1039/c5cs00655d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Yoon T. P.; Ischay M. A.; Du J. Visible Light Photocatalysis as a Greener Approach to Photochemical Synthesis. Nat. Chem. 2010, 2, 527. 10.1038/nchem.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Narayanam J. M. R.; Stephenson C. R. J. Visible light photoredox catalysis: applications in organic synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 102. 10.1039/b913880n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Teplý F. Photoredox Catalysis by [Ru(bpy)3]2+ to Trigger Transformations of Organic Molecules. Organic Synthesis using Visible-Light Photocatalysis and its 20th Century Roots. Collect.Czech. Chem. Commun. 2011, 76, 859. 10.1135/cccc2011078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Xuan J.; Xiao W.-J. Visible-Light Photoredox Catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 6828. 10.1002/anie.201200223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Shi L.; Xia W. Photoredox Functionalization of C–H Bonds Adjacent to a Nitrogen Atom. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 7687. 10.1039/c2cs35203f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Hari D. P.; König B. The Photocatalyzed Meerwein Arylation: Classic Reaction of Aryl Diazonium Salts in a New Light. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 4734.The Photoredox-Catalyzed Meerwein Addition Reaction: Intermolecular Amino-Arylation of Alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.,2014, 53, 725 10.1002/anie.201210276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Xi Y.; Yi H.; Lei A. Synthetic Applications of Photoredox Catalysis with Visible Light. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 2387. 10.1039/c3ob40137e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Dai X.-J.; Xu X.-L.; Li X.-N. Applications of Visible Light Photoredox Catalysis in Organic Synthesis. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 33, 2046. 10.6023/cjoc201304026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Fagnoni M.; Dondi D.; Ravelli D.; Albini A. Photocatalysis for the Formation of the C-C Bond. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 2725. 10.1021/cr068352x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Gambarotti C.; Punta C.; Recupero F.; Caronna T.; Palmisano L. Liquid Phase Oxidation via Heterogeneous Catalysis: Organic Synthesis and Industrial Applications. Curr. Org. Chem. 2010, 14, 1153. 10.2174/138527210791317111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Zeitler K. Photoredox Catalysis with Visible Light. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 9785. 10.1002/anie.200904056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Hering T.; Hari D. P.; König B. Visible-Light-Mediated α-Arylation of Enol Acetates Using Aryl Diazonium Salts. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 10347. 10.1021/jo301984p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Rueping M.; Vila C.; Bootwicha T. Continuous Flow Organocatalytic C–H Functionalization and Cross-Dehydrogenative Coupling Reactions: Visible Light Organophotocatalysis for Multicomponent Reactions and C–C, C–P Bond Formations. ACS Catal 2013, 3, 1676. 10.1021/cs400350j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Skubi K. L.; Yoon T. P. Shape Control in Reactions with Light. Nature 2014, 515, 45. 10.1038/515045a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Xu Z.; Gao L.; Wang L.; Gong M.; Wang W.; Yuan R. Visible Light Catalysis Assisted Site-Specific Functionalization of Amino Acid Derivatives by C–H Bond Activation without Oxidant: Cross-Coupling Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. ACS Catal 2015, 5, 2391. 10.1021/cs5011037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; h Ravelli D.; Protti S.; Albini A. Energy and Molecules from Photochemical/Photocatalytic Reactions: An Overview. Molecules 2015, 20, 1527. 10.3390/molecules20011527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reckenthäler M.; Griesbeck A. G. Photoredox Catalysis for Organic Syntheses. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2013, 355, 2727. 10.1002/adsc.201300751. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz D. M.; Yoon T. P. Solar Synthesis: Prospects in Visible Light Photocatalysis. Science 2014, 343, 1239176. 10.1126/science.1239176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan F.; Xiao W. Visible-Light Photoredox Catalysis in Natural Products Synthesis. Acta Chim. Sin. 2015, 73, 85. 10.6023/a14120860. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kärkäs M. D.; Porco J. A. Jr.; Stephenson C. R. J. Photochemical Approaches to Complex Chemotypes: Applications in Natural Products Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 9683. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studer A.; Curran D. P. Catalysis in Radical Reactions: A Radical Chemistry Perspective. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 58. 10.1002/anie.201505090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Hulme C.; Gore V. Multi-Component Reactions: Emerging Chemistry in Drug Discovery″ ’from Xylocain to Crixivan. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003, 10, 51. 10.2174/0929867033368600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Orru R. V. A.; de Greef M. Recent Advances in Solution-Phase Multicomponent Methodology for the Synthesis of Heterocyclic Compounds. Synthesis 2003, 10, 1471. 10.1055/s-2003-40507. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Zhu J. Recent Developments in the Isonitrile-Based Multicomponent Synthesis of Heterocycles. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 2003, 1133. 10.1002/ejoc.200390167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Simon C.; Constantieux T.; Rodriguez J. Utilisation of 1,3-Dicarbonyl Derivatives in Multicomponent Reactions. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 2004, 4957. 10.1002/ejoc.200400511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Ramón D. J.; Yus M. Asymmetric Multicomponent Reactions (AMCRs): The New Frontier. Angew. Chem. 2005, 117, 1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.,2005, 44, 1602.; f Banfi L.; Riva R.. Organic Reactions Overman L. E. Ed.; Wiley: Weinheim, 2005, 65. [Google Scholar]; g Dömling A. Recent Developments in Isocyanide Based Multicomponent Reactions in Applied Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 17. 10.1021/cr0505728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Sunderhaus J. D.; Martin S. F. Applications of Multicomponent Reactions to the Synthesis of Diverse Heterocyclic Scaffolds. Chem. Eur. J. 2009, 15, 1300. 10.1002/chem.200802140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Tietze L. F. Domino Reactions in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 115. 10.1021/cr950027e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Nicolaou K. C.; Edmonds D. J.; Bulger P. G. Kaskadenreaktionen in der Totalsynthese. Angew. Chem. 2006, 118, 7292. 10.1002/ange.200601872. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.,2006, 45, 7134; c Enders D.; Grondal C.; Huttl M. R. M. Asymmetric Organocatalytic Domino Reactions. Angew. Chem. 2007, 38, 1590. 10.1002/anie.200603129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ; .Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.,2007, 46, 1570; d Grondal C.; Jeanty M.; Enders D. Organocatalytic Cascade Reactions as a New Tool in Total Synthesis. Nat. Chem. 2010, 2, 167. 10.1038/nchem.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Enders D.; Hüttl M. R. M.; Grondal C.; Raabe G. Control of Four Stereocentres in a Triple Cascade Organocatalytic Reaction. Nature 2006, 441, 861. 10.1038/nature04820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Ugi I. Recent Progress in the Chemistry of Multicomponent Reactions. Pure.Appl. Chem. 2001, 73, 187. 10.1351/pac200173010187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Nair V.; Rajesh C.; Vinod A. U.; Bindu S.; Sreekanth A. R.; Mathen J. S.; Balagopal L. Strategies for Heterocyclic Construction via Novel Multicomponent Reactions Based on Isocyanides and Nucleophilic Carbenes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2003, 36, 899. 10.1021/ar020258p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Seayad J.List, B. Catalytic Asymmetric Multicomponent Reactions: in Multicomponent Reaction Zhu J., Bienaym H. Eds.; Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2005. [Google Scholar]; d Ganem B. Strategies for Innovation in Multicomponent Reaction Design. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 463. 10.1021/ar800214s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Yue T.; Wang M.-X.; Wang D.-X.; Masson G.; Zhu J. Brønsted Acid Catalyzed Enantioselective Three-Component Reaction Involving the α Addition of Isocyanides to Imines. Angew. Chem. 2009, 121, 6845. 10.1002/ange.200902385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.,2009, 48, 6717; f Yu J.; Shi F.; Gong L.-Z. Brønsted-Acid-Catalyzed Asymmetric Multicomponent Reactions for the Facile Synthesis of Highly Enantioenriched Structurally Diverse Nitrogenous Heterocycles. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 1156. 10.1021/ar2000343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g de Graaff C.; Ruijter E.; Orru R. V. A. Recent Developments in Asymmetric Multicomponent Reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 3969. 10.1039/c2cs15361k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Ohno H.; Ohta Y.; Oishi S.; Fujii N. Facile Synthesis of 3-(Aminomethyl)isoquinoline by Copper-Catalyzed Domino Four-Component Coupling and Cyclization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Bonne D.; Dekhane M.; Zhu J. Direct Synthesis of 2-(Aminomethyl)indoles through Copper(I)-Catalyzed Domino Three-Component Coupling and Cyclization Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 2485. 10.1002/anie.200604342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Pinto A.; Neuville L.; Zhu J. P. Palladium-Catalyzed Three-Somponent Synthesis of 3-(diarylmethylene)Oxindoles Through a Domino Sonagashira/Carbopalladation/C--H Activation/C--C Bond-Forming Sequence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 3291. 10.1002/anie.200605192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Komagawa S.; Saito S. Nickel-Catalyzed Three-Component [3+2+2] Cocyclization of Ethyl Cyclopropylideneacetate and Alkynes—Selective Synthesis of Multisubstituted Cycloheptadienes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 2446. 10.1002/anie.200504050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Yoshida H.; Fukushima H.; Ohshita J.; Kunai A. CO2 Incorporation Reaction Using Arynes: Straightforward Access to Benzoxazinone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 11040. 10.1021/ja064157o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Dondas H. A.; Fishwick C. W. G.; Gai X.; Grigg R.; Kilner C.; Dumrongchai N.; Kongkathip B.; Kongkathip N.; Polysuk C.; Sridharan V. Stereoselective Palladium-Catalyzed Four-Component Cascade Synthesis of Pyrrolidinyl-, Pyrazolidinyl-, and Isoxazolidinyl isoquinolines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 7570. 10.1002/anie.200502066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Pache S.; Lautens M. Palladium-Catalyzed Sequential Alkylation–Alkenylation Reactions: New Three-Component Coupling Leading to Oxacycles. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 4827. 10.1021/ol035806t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Miyamoto H.; Okawa Y.; Nakazaki A.; Kobayashi S. Highly Diastereoselective One Pot Synthesis of Spirocyclic Oxindoles through Intramolecular Ullmann Coupling and Claisen Rearrangement. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 2274. 10.1002/anie.200504247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Tietze L. F.; Sommer K. M.; Zinngrebe J.; Stecker F. Palladium-Catalyzed Enantioselective Domino Reaction for the Efficient Synthesis of Vitamin E. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 257. 10.1002/anie.200461629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Yamamoto Y.; Hayashi H.; Saigoku T.; Nishiyama H. J. Domino Coupling Relay Approach to Polycyclic Pyrrole-2-carboxylates. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 10804. 10.1021/ja053408a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Tietze L. F.; Ila H.; Bell H. P. Enantioselective Palladium-Catalyzed Transformations. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 3453. 10.1021/cr030700x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siamaki A. R.; Arndtsen B. A. A Direct, One Step Synthesis of Imidazoles from Imines and Acid Chlorides: A Palladium Catalyzed Multicomponent Coupling Approach. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 6050. 10.1021/ja060705m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhu J.; Bienaymé H.. Multicomponent Reactions; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2005. [Google Scholar]; b Tietze L. F.; Brasche G.; Gericke K.. Domino Reactions in Organic Synthesis; Wiley- VCH: Weinheim,2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dömling A.; Ugi I. Ugi Four-Component Reaction (U-4CR) Under Green Conditions Designed for Undergraduate Organic Chemistry Laboratories. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 3168. [Google Scholar]

- a Varvounis G. Chapter 2 Pyrazol-3-ones. Part IV: Synthesis and Applications. Adv. Heterocycl. Chem. 2009, 98, 143–224. 10.1016/s0065-2725(09)09802-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Ke B.; Tian M.; Li J.; Liu B.; He G. Targeting Programmed Cell Death Using Small molecule Compounds to Improve Potential Cancer Therapy. Med. Res. Rev. 2016, 36, 983. 10.1002/med.21398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Fustero S.; Sánchez-Roselló M.; Barrio P.; Simón-Fuentes A. From 2000 to Mid-2010: A Fruitful Decade for the Synthesis of Pyrazoles. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 6984. 10.1021/cr2000459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Schmidt A.; Dreger A. Recent Advances in the Chemistry of Pyrazoles. Properties, Biological Activities, and Syntheses. Curr. Org. Chem. 2011, 15, 1423. 10.2174/138527211795378263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Sondhi S. M.; Dinodia M.; Singh J.; Rani R. Heterocyclic Compounds as Anti-inflammatory Agents. Curr. Bioact. Compd. 2007, 3, 91. 10.2174/157340707780809554. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Horton D. A.; Bourne G. T.; Smythe M. L. The Combinatorial Synthesis of Bicyclic Privileged Structures or Privileged Substructures. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 893.the references therein 10.1021/cr020033s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norouzi M.; Elhamifar D. Ionic liquid-modified Magnetic Mesoporous Silica Supported Tungstate: A Powerful and Magnetically Recoverable Nanocatalyst. Catal. Letters 2019, 149, 619. 10.1007/s10562-019-02653-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sujatha K.; Shanthi G.; Selvam N.P.; Manoharan S.; Perumal P.T.; Rajendran M. Synthesis and Antiviral Activity of 4,4’-(arylmethylene)bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ols) Against Peste des Petits Ruminant Virus (PPRV). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 4501. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.02.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhavanarushi S.; Kanakaiah V.; Bharath G.; Gangagnirao A.; Rani V. Synthesis and Antibacterial Activity of 4,4′-(aryl or alkyl methylene)-bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ol) Derivatives. J. Med. Chem. Res. 2014, 23, 158. 10.1007/s00044-013-0623-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zolfigol M. A.; Khazaei A.; Karimitabar F.; Hamidi M. Alum as a Catalyst for the Synthesis of Bispyrazole Derivatives. Appl. Sci. 2016, 60, 10027. 10.3390/app6010027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey D. M.; Hansen P.E.; Hlavac A.G.; Baizman E.R.; Pearl J.; DeFelice A.F.; Feigenson M.E. 3,4-Diphenyl-1H-pyrazole-1-propanamine Antidepressants. J. Med. Chem. 1985, 28, 256. 10.1021/jm00380a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malvar D.; Ferreira R. T.; de Castro R. A.; de Castro L. L.; Freitas A.C. C.; Costa E. A.; Florentino I.F.; Mafra J.C. M.; de Souza G.E. P.; Vanderlinde F.A. Antinociceptive, Anti-inflammatory and Antipyretic Effects of 1.5-diphenyl-1H-Pyrazole-3-carbohydrazide, A New Heterocyclic Pyrazole Derivative. Life Sci 2014, 95, 81. 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shekouhy M.; Kordnezhadian R.; Khalafi-Nezhad A. Silica-bonded DABCO hydrogen sulfate ((SB-DABCO)HSO4): A New Dual-interphase Catalyst for the Diversity-oriented Pseudo-five-component Synthesis of bis(pyrazolyl)methanes and Novel 4-[bis(pyrazolyl)methane]phenylmethylene-bis(indole)s. J. Iran.Chem. Soc. 2018, 15, 2357. 10.1007/s13738-018-1424-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosiere C.E.; Grossman M. I. An Analog of Histamine that Stimulates Gastric Acid Secretion without Other Actions of Histamine. Science 1951, 113, 651. 10.1126/science.113.2945.651-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azarifar D.; Khatami S. M.; Zolfigol M. A.; Nejat-Yami R. Nano-titania Sulfuric acid-promoted Synthesis of Tetrahydrobenzo[b]pyran and 1,4-dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole Derivatives under Ultrasound Irradiation. J. Iran.Chem. Soc. 2014, 11, 1223. 10.1007/s13738-013-0392-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farhadi S.; Jahanara K.; Sepahdar A. Sol–gel derived LaFeO3/SiO2 Nanocomposite: Synthesis, Characterization and its Application as a New, Green and Recoverable Heterogeneous Catalyst for the Efficient Acetylation of Amines, Alcohols and Phenols. J. Iran.Chem. Soc. 2014, 11, 1103. 10.1007/s13738-013-0377-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niknam K.; Mirzaee S. Silica Sulfuric Acid, an Efficient and Recyclable Solid Acid Catalyst for the Synthesis of 4,4′-(Arylmethylene)bis (1H-pyrazol-5-ols). Synth. Commun. 2011, 41, 2403. 10.1080/00397911.2010.502999. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hasaninejad A.; Shekouhy M.; Zare A.; Hoseini Ghattali S. M. S.; Golzar N. PEG-SO3H as a New, Highly Efficient and Homogeneous Polymeric Catalyst for the Synthesis of bis(indolyl)methanes and 4,4′-(arylmethylene)-bis(3-methyl-1-phenyl-1Hpyrazol-5-ol)s in Water. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2011, 8, 411. 10.1007/bf03249075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sridhar R.; Perumal P.T.; Etti S.; Shanmugam G.; Ponnuswamy M. N.; Prabavathy V. R.; Mathivanan N. Design, Synthesis and Anti-microbial Activity of 1H-pyrazole carboxylates. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004, 14, 6035. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivaprasad G.; Perumal P. T.; Prabavathy V. R.; Mathivanan N. Synthesis and Anti-microbial Activity of Pyrazolylbisindoles—Promising Anti-fungal Compounds. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 6302. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Londershausen M. Review: Approaches to New Parasiticides. Pestic. Sci. 1996, 48, 269.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh D.; SINGH D. Synthesis and Antifungal Activity of Some 4-Arylmethylene Derivatives of Substituted Pyrazolones. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 1991, 68, 165. [Google Scholar]

- Lubs H.A.The Chemistry of Synthetic Dyes and Pigments, Ed.; Am. Chem. Soc., Washington, DC. 1970. [Google Scholar]

- a Yuan W. J.; Yasuhara T.; Shingo T.; Muraoka K.; Agari T.; Kameda M.; Uozumi T.; Tajiri N.; Morimoto T.; Jing M.; Baba T.; Wang F.; Leung H.; Matsui T.; Miyoshi Y.; Date I. Neuroprotective Effects of Edaravone-administration on 6-OHDA-treated Dopaminergic Neurons. BMC Neurosci 2008, 9, 75. 10.1186/1471-2202-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Yoshida H.; Yanai H.; Namiki Y.; Fukatsu-Sasaki K.; Furutani N.; Tada N. Neuroprotective Effects of Edaravone: A Novel Free Radical Scavenger in Cerebrovascular Injury. CNS Drug Rev 2006, 12, 9. 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2006.00009.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Cadena-Cruz J. E.; Guamán-Ortiz J. E.; Romero-Benavides M.; Bailon-Moscoso J. C.; Murillo-Sotomayor N.; Ortiz-Guamán K. E.; Heredia-Moya N. V.; Heredia-Moya J.; Cadena-Cruz V.; et al. Synthesis of 4,4′-(arylmethylene)-bis-(3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-ols) and Evaluation of their Antioxidant and Anticancer Activities. BMC Chemistry 2021, 15, 38. 10.1186/s13065-021-00765-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan S. S.; Scian M.; Sripathy S.; Posakony J.; Lao U.; Loe T. K.; Leko V.; Thalhofer A.; Schuler A. D.; Bedalov A.; Simon J. A. Development of Pyrazolone and Isoxazol-5-one Cambinol Analogues as Sirtuin Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 3283. 10.1021/jm4018064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadi V.; Koh Y.-H.; Sanchez T. W.; Barrios D.; Neamati N.; Jung K. W. Development of the Next Generation of HIV-1 Integrase Inhibitors: Pyrazolone as A Novel Inhibitor Scaffold. Bioorg.Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 6854. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.08.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chande M. S.; Barve P. A.; Suryanarayan V. Synthesis and Antimicrobial Activity of Novel Spirocompounds with Pyrazolone and Pyrazolthione Moiety. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2007, 44, 49. 10.1002/jhet.5570440108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schlemminger I.; Schmidt B.; Flockerzi D.; Tenor H.; Zitt C.; Hatzelmann A.; Marx D.; Braun C.; Kuelzer R.; Heuser A.; Kley H.-P.; Sterk G. J.. Novel Pyrazolone-derivatives and Their Use as PD4 Inhibitors. WO 2010,055,083, 2008.

- Chauhan P.; Mahajan S.; Enders D. Asymmetric Synthesis of Pyrazoles and Pyrazolones Employing the Reactivity of Pyrazolin-5-one Derivatives. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 12890. 10.1039/c5cc04930j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Singh D.; Singh D. Syntheses of 1, 3-Disubstituted 4-Arylidenepyrazolin-5-ones and the Keto and Enol Forms of 4,4’-arylidene-bis-(1, 3-disubstituted pyrazolin-5-ones). J. Chem. Eng. Data 1984, 29, 355. 10.1021/je00037a040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Gupta A. D.; Pal R.; Mallik A.K. Two Efficient and Green Methods for Synthesis of 4,4′-(arylmethylene)bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ols) Without Use of Any Catalyst or Solvent. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2014, 7, 404. [Google Scholar]

- a Patil P. G.; Sehlangia S.; More D. H. Chitosan-SO3H (CTSA) An Efficient and Biodegradable Polymeric Catalyst for the Synthesis of 4,4′-(arylmethylene)bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ol) and α-amidoalkyl-β-naphthol’s. Synth. Commun. 2020, 50, 1696. 10.1080/00397911.2020.1753078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Karimi-jaberi Z.; Pooladian B.; Moradi M.; Ghasemi E. 1,3,5-tris(Hydrogensulfato) Benzene: A New and Efficient Catalyst for Synthesis of 4,4’-(arylmethylene) Bis(1H- pyrazol-5-ol) Derivatives. Chin. J. Catal. 2012, 33, 1945. 10.1016/s1872-2067(11)60477-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Gouda M. A.; Abu-Hashem A. A. An Eco-Friendly Procedure for the Efficient Synthesis of Arylidinemalononitriles and 4,4’-(arylmethylene)Bis(3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5- ols) in Aqueous Media. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2012, 5, 203. 10.1080/17518253.2011.613858. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Mosaddegh E.; Hassankhani A.; Baghizadeh A. Cellulose Sulfuric Acid as a New, Biodegradable and Environmentally Friendly Biopolymer for Synthesis of 4,4’-(arylmethylene)bis(3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5- ols). J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2010, 55, 419. 10.4067/s0717-97072010000400001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Moosavi-Zare A. R.; Zolfigol M. A.; Noroozizadeh E.; Khaledian O.; Shaghasemi B. S. Cyclocondensation-Knoevenagel–MichaelDomino Reaction of Phenyl Hydrazine, Acetoacetate Derivatives and Aryl Aldehydes over Acetic Acid Functionalized Ionic Liquid. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2016, 42, 4759. 10.1007/s11164-015-2317-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Kuarm B. S.; Rajitha B. Xanthan Sulfuric Acid, R. An Efficient, Biosupported, and Recyclable Solid Acid Catalyst for the Synthesis of 4,4-(arylmethylene)bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ols). Synth. Commun. 2012, 42, 2382. 10.1080/00397911.2011.557516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Sobhani S.; Nasseri R.; Honarmand M. 2-Hydroxyethylammonium Acetate as a Reusable and Cost-Effective Ionic Liquid for the Efficient Synthesis of Bis(pyrazolyl)methanes and 2-pyrazolyl-1-nitroalkanes. Can. J. Chem. 2012, 90, 798. 10.1139/v2012-059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; h Phatangare K.; Padalkar V.; Gupta V.; Patil V.; Umape P. G.; Sekar N. Phosphomolybdic Acid: An Efficient and Recyclable Solid Acid Catalyst for the Synthesis of 4,4’-(Arylmethylene)bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ols). Synth. Commun. 2012, 42, 1349. 10.1080/00397911.2010.539759. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; i Sobhani S.; Hasaninejad A. R.; Maleki M. F.; Parizi Z. P. Tandem Knoevenagel-Michael Reaction of 1-phenyl-3-methyl-5-pyrazolone with Aldehydes Using 3-Aminopropylated Silica Gel as an Efficient and Reusable Heterogeneous Catalyst. Synth. Commun. 2012, 42, 2245. 10.1080/00397911.2011.555589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; j Zhou Z.; Zhang Y. An Eco-Friendly One-Pot Synthesis of 4,4’(arylmethylene)-bis-(1H-pyrazol- 5-ols) Using [Et3NH][HSO4] as a Recyclable Catalyst. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2015, 60, 2992. 10.4067/s0717-97072015000300003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; k Niknam K.; Saberi D.; Sadegheyan M.; Deris A. Silica-Bonded S-Sulfonic Acid: An Efficient and Recyclable Solid Acid Catalyst for the Synthesis of 4,4’- (arylmethylene)-bis-(1H-pyrazol-5-ols). Tetrahedron Lett 2010, 51, 692. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.11.114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; l Moosavi-Zare A. R.; Zolfigol M. A.; Zarei M.; Zare A.; Khakyzadeh V.; Hasaninejad A. Design, Characterization and Application of New Ionic Liquid 1-Sulfopyridinium Chloride as an Efficient Catalyst for Tandem Knoevenagel – Michael Reaction of 3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5(4H)-One with Aldehydes. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2013, 467, 61. 10.1016/j.apcata.2013.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; m Elinson M.N.; Dorofeev A.S.; Nasybullin R.F.; Nikishin G.I. Facile and Convenient Synthesis of 4,4′-(arylmethylene)bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ols) by Electrocatalytic Tandem Knoevenagel-Michael Reaction. Synthesis 2008, 2008, 1933. 10.1055/s-2008-1067079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; n Shirini F.; Seddighi M.; Mazloumi M.; Makhsous M.; Abedini M. One-pot Synthesis of 4,4′-(arylmethylene)-bis-(3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-ols) Catalyzed by Brönsted Acidic Ionic Liquid Supported on Nanoporous Na+-montmorillonite. J. Mol. Liq. 2015, 208, 291. 10.1016/j.molliq.2015.04.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; o Zhou Z.; Zhang Y. An Efficient and Green One-pot Three-component Synthesis of 4,4′-(arylmethylene)-bis-(1H-pyrazol-5-ol)s Catalyzed by 2-Hydroxyethylammonium Propionate. Green Chem.Lett.Rev. 2014, 7, 18. 10.1080/17518253.2014.894142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; p Gupta P.; Gupta J. K.; Halve A. K. Synthesis and biological significance of pyrazolones: A review. IJPSR 2015, 6, 2291. [Google Scholar]; q Iravani N.; Albadi J.; Momtazan H.; Baghernejad M. Melamine Trisulfunic Acid: An Efficient and Recyclable Solid Acid Catalyst for the Synthesis of 4,4′-(arylmethylene)-bis-(1H-pyrazol-5-ols). J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2013, 60, 418. 10.1002/jccs.201200345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; r Wang W.; Wang S.X.; Qin X.Y.; Li J.T. Reaction of Aldehydes and Pyrazolones in the Presence of Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate in Aqueous Media. Synth. Commun. 2005, 35, 1263. 10.1081/scc-200054854. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; s Zheng Y.; Zheng Y.; Wang Z.; Cao Y.; Shao Q.; Guo Z. Sodium Dodecyl Benzene Sulfonate-catalyzed Reaction for Aromatic Aldehydes with 1-phenyl-3-methyl-5-pyrazolone in Aqueous Media. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2018, 11, 217. 10.1080/17518253.2018.1465600. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; t Eskandari K.; Karami B.; Khodabakhshi S.; Hoseini S. J. Green and Efficient Synthesis of Novel bispyrazole Through a Tandem Knoevenagel and Michael type Reaction using Nanowire Zinc oxide as Powerful and Recyclable Catalyst. Turk. J. Chem. 2015, 39, 1069. 10.3906/kim-1404-54. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; u Khazaei A.; Zolfigol M.A.; Moosavi-Zare A.R.; Asgari Z.; Shekouhy M.; Zare A.; Hasaninejad A. Preparation of 4,4′-(arylmethylene)-bis(3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-ol)s over 1,3-disulfonic acid Imidazolium Tetrachloroaluminate as a Novel Catalyst. RSC Adv 2012, 2, 8010. 10.1039/c2ra20988h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; v Metwally M. A.; Bondock S. A.; El-Desouky S. E.; Abdou M. M. Pyrazol-5-ones: Tautomerism, Synthesis and Reactions. Int. J. Mod. Org. Chem. 2012, 1, 19. [Google Scholar]; w Zang V.; Su Q.; Mo Y.; Cheng B. Ionic Liquid under Ultrasonic Irradiation towards a Facile Synthesis of Pyrazolone Derivatives. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2001, 18, 68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; x Zang H.; Su Q.; Guo S.; Mo Y.; Cheng B. An Efficient One pot Synthesis of Pyrazolone Derivatives Promoted by Acidic Ionic Liquid. Chin. J. Chem. 2011, 29, 2202. 10.1002/cjoc.201180381. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; y Huang R. T.; Rott R.; Klenk H. D. Influenza Viruses Cause Hemolysis and Fusion of Cells. Virology 1981, 110, 243. 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Rostami E.; Kordrostami Z. An Efficient Synthesis of 4,4’-(aryl methylene)-bis-(1H-pyrazol-5-ols) Over Graphene oxide Functionalized Pyridine-methanesulfonate as a Novel Nanocatalyst. Asian Journal of Nanosciences and Materials 2020, 3, 203. [Google Scholar]; b Tale N. P.; Tiwari G. B.; Karade N. N. Un-catalyzed tandem Knoevenagel–Michael reaction for the synthesis of 4,4′-(arylmethylene)-bis-(1H-pyrazol-5-ols) in aqueous medium. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2011, 22, 1415. 10.1016/j.cclet.2011.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Phatangare K. R.; Padalkar V. S.; Gupta V. D.; Patil V. S.; Umape P. G.; Sekar N. Phosphomolybdic Acid: An Efficient and Recyclable Solid Acid Catalyst for the Synthesis of 4,4′-(arylmethylene)-bis-(1H-pyrazol-5-ols). Synth. Commn. 2012, 42, 1349. 10.1080/00397911.2010.539759. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Niknam K.; Habibabad M. H.; Deris A.; Aeinjamshid N. Preparation of silica-bonded N-propyltriethylenetetramine as a recyclable solid base catalyst for the synthesis of 4,4’-(arylmethylene)-bis-(1H-pyrazol-5-ols). Monatsh Chem 2013, 144, 987. 10.1007/s00706-012-0910-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Zheng Y.; Zheng Y.; Wang Z.; et al. Sodium Dodecylbenzenesulfonate-Catalyzed Reaction for Aromatic Aldehydes with 1-phenyl-3-methyl-5-pyrazolone in Aqueous Media. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2018, 11, 217. 10.1080/17518253.2018.1465600. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a El-Gamal M. I.; Zaraei S-O.; Madkour M. M.; Anbar H. S. Evaluation of Substituted Pyrazole-Based Kinase Inhibitors in One Decade (2011–2020): Current Status and Future Prospects. Molecules 2022, 27, 330. 10.3390/molecules27010330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lehmann T. P.; Kujawski J.; Kruk J.; Czaja K.; Bernard M. K.; Jagodzinski P. P. Cell-specific Cytotoxic Effect of Pyrazole Derivatives on Breast Cancer Cell lines MCF7 and MDA-MB-231. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2017, 68, 201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Anwar M. M.; Abd El-Karim S. S.; Mahmoud A. H.; Amr A. E. E.; Al-Omar M. A. A Comparative Study of the Anticancer Activity and PARP-1 Inhibiting Effect of Benzofuran-Pyrazole Scaffold and Its Nano-Sized Particles in Human Breast Cancer Cells. Molecules 2019, 24, 2413. 10.3390/molecules24132413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Bennani F. E.; Doudach L.; Karrouchi K.; El rhayam Y.; Rudd E.C.; Ansar M.; El Abbes Faouzi M-E. A. Design and Prediction of Novel Pyrazole Derivatives as Potential Anti-cancer Compounds based on 2D-2D-QSAR Study against PC-3, B16F10, K562, MDA-MB-231, A2780, ACHN and NUGC Cancer Cell lines. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10003 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Saquib M.; Baig M. H.; Khan M. F.; Azmi S.; Khatoon S.; Rawat A. K.; Dong J. J.; Asad M.; Arshad M.; Hussain M. K. Design and Synthesis of Bioinspired Benzocoumarin-Chalcones Chimeras as Potential Anti-Breast Cancer Agents. Chemistry Select 2021, 6, 8754. 10.1002/slct.202101853. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Hussain M. H.; Ansari M. I.; Yadav N.; Gupta P. K.; Gupta A. K.; Saxena R.; Fatima I.; Manohar M.; Kushwaha P.; Khedgikar V.; Gautam J.; Kant R.; Maulik P. R.; Trivedi R.; Dwivedi A.; Kumar K. R.; Saxena A. K.; Hajela K. Design and Synthesis of ERα/ERβ Selective Coumarin and Chromene Derivatives as Potential Anti-breast cancer and Anti-osteoporotic Agents. RSC Advances 2014, 4, 8828. 10.1039/c3ra45749d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Ansari M. I.; Hussain M. K.; Arun A.; Chakravarti B.; Konwar R.; Hajela K. Synthesis of Targeted Dibenzo[b,f]thiepines and dibenzo[b,f]oxepines as Potential Lead Molecules with Promising Anti-breast cancer Activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 99, 113. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Ansari M. I.; Arun A.; Hussain M. K.; Konwar R.; Hajela K. Discovery of 3, 4, 6-Triaryl-2-pyridones as Potential Anticancer Agents that Promote ROS-Independent Mitochondrial-Mediated Apoptosis in Human Breast Carcinoma Cells. Chemistry Select 2016, 1, 4255. 10.1002/slct.201600893. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Shankar R.; Chakravarti B.; Singh U. S.; Ansari M. I.; Deshpande S.; Dwivedi S. K. D.; Bid H. K.; Konwar R.; Kharkwal G.; Chandra V.; Dwivedi A.; Hajela K. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of 3,4,6-triaryl-2-pyranones as a Potential New Class of Anti-breast cancer Agents. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2009, 17, 3847. 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Sashidhara K. V.; Rosaiah J. N.; Kumar M.; Gara R. K.; Nayak L. V.; Srivastava K.; Bid H. K.; Konwar R. Neo-tanshinlactone Inspired Synthesis, In vitro Evaluation of Novel Substituted Benzocoumarin Derivatives as Potent Anti-breast Cancer Agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 7127–7131. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Kumar S.; Deshpande S.; Chandra V.; Kitchlu S.; Dwivedi A.; Nayak V. L.; Konwar R.; Prabhakar Y. S.; Sahu D. P. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of 2,3,4-triarylbenzopyran Derivatives as SERM and Therapeutic Agent for Breast Cancer. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2009, 17, 6832–6840. 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Etti I.; Abdullah R.; Hashim N.M.; Kadir A.; Abdul A.B.; Etti C.; Malami I.; Waziri P.; How C.W. Artonin E and Structural Analogs from Artocarpus Species Abrogates Estrogen Receptor Signaling in Breast Cancer. Molecules 2016, 21, 839. 10.3390/molecules21070839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S. T.; Jeon Y. W.; Gwak H.; Kim S. Y.; Suh Y. J. Synergistic Anticancer Effects of Ruxolitinib and Calcitriol in Estrogen Receptor- positive, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-positive Breast Cancer Cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 5581. 10.3892/mmr.2018.8580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Bairi K.; Trapani D.; Petrillo A.; Le Page C.; Zbakh H.; Daniele B.; Belbaraka R.; Curigliano G.; Afqir S. Repurposing Anticancer Drugs for the Management of COVID-19. Eur. J. Cancer 2020, 141, 40. 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari S.; Singh M.; Sharma P.; Arora S. Pyrazolones as a Potential Anticancer Scaffold: Recent Trends and Future Perspectives. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 11, 026. [Google Scholar]

- a Chen L.; Chen S.; Gui C.; Shen J.; Shen X.; Jiang H. Discovering Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 3CL Protease Inhibitors: Virtual Screening, Surface Plasmon Resonance, and Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer Assays. J. Biomol. Screen. 2006, 11, 915. 10.1177/1087057106293295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kuo C. J.; Liu H. G.; Lo Y. K.; Seong C. M.; Lee K. I.; Jung Y. S.; Liang P. H. Individual and Common Inhibitors of Coronavirus and Picornavirus Main Proteases. FEBS Lett 2009, 583, 549. 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.12.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Ramajayam R.; Tan K-P.; Liu H-G.; Liang P-H. Synthesis and Evaluation of Pyrazolone Compounds as SARS-coronavirus 3C-like Protease Inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 7849. 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Brankovíc J.; Milovanovíc V. M.; Simijonovíc D.; Novakovíc S.; Petrovíc Z. D.; Trifunovíc S. S.; Bogdanovíc G. A.; Petrovíc V. P. Pyrazolone-type Compounds: Synthesis and In silico Assessment of Antiviral Potential Against Key Viral Proteins of SARS-CoV-2. RSC Adv 2022, 12, 16054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Addoum B.; El Khalfi B.; Sakoui S.; Derdak R.; Elmakssoudi A.; Soukri A. Synthesis and Molecular Docking Studies of Some Pyrano[2,3-c] Pyrazole as an Inhibitor of SARS-Coronavirus 3CL Protease. Lett. Appl. NanoBioscience 2022, 11, 3780. [Google Scholar]

- a Ton A. T.; Gentile F.; Hsing M.; Ban F.; Cherkasov A. Rapid Identification of Potential Inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease by Deep Docking of 1.3 Billion Compounds. Mol. Inform. 2020, 39, 2000028. 10.1002/minf.202000028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Báez-Santos Y. M.; St John S. E.; Mesecar A. D. The SARS-Coronavirus Papain-like Protease: Structure, Function and Inhibition by Designed Antiviral Compounds. Antiviral Res 2015, 115, 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z.; Du X.; et al. Structure Mpro from SARS-CoV-2 and Discovery of its Inhibitors. Nature 2020, 582, 289. 10.1038/s41586-020-2223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narkhede R.; Cheke R.; Ambhore J.; Shinde S. The Molecular Docking Study of Potential Drug Candidates Showing Anti-COVID-19 Activity by Exploring of Therapeutic Targets of SARS-CoV-2. EJMO 2020, 4, 185–195. [Google Scholar]

- a Liu G.; Niu P.; Yin L.; Cheng H. M. α-Sulfur Crystals as a Visible-Light-active Photocatalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 9070. 10.1021/ja302897b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hoffmann N. Photochemical Reactions as Key Steps in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 1052. 10.1021/cr0680336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Tiwari J.; Saquib M.; Singh S.; Tufail F.; Singh M.; Singh J.; Singh J. Visible Light Promoted Synthesis of dihydropyrano[2,3-c]chromenes via a Multicomponent-Tandem Strategy under Solvent and Catalyst free Conditions. Green Chem 2016, 18, 3221. 10.1039/c5gc02855h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Davoodinia A.; Moghaddas M. Der Pharma Chemica 2015, 7, 46. [Google Scholar]; e Hari D. P.; König B.; Eosin Y. Catalyzed Visible Light Oxidative C–C and C–P bond Formation. Org Lett 2011, 13, 3852. 10.1021/ol201376v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Mohamadpour F.; für M. Catalyst-free and Solvent-free Visible Light Irradiation-assisted Knoevenagel–Michael Cyclocondensation of Arylaldehydes, Malononitrile, and Resorcinol at Room Temperature. Chemie - Chemical Monthly 2021, 152, 507. 10.1007/s00706-021-02763-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Nadaf A. N.; Shivashankar K. Visible Light-Induced Synthesis of Biscoumarin Analogs under Catalyst-Free Conditions. J. Heterocyclic Chem. 2018, 55, 1375. 10.1002/jhet.3171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y.; Huang K.; Pan J.; Qiu X.; Luo X.; Luo Q.; Qin J.; Wei X.; Wen L.; Zhang N.; Jiao N. Silver-catalyzed Remote Csp3-H Functionalization of Aliphatic Alcohols. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2625. 10.1038/s41467-018-05014-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.