Abstract

Background

People with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) and their carers/families continue to experience structural stigma when accessing health services. Structural stigma involves societal-level conditions, cultural norms, and organizational policies that inhibit the opportunities, resources, and wellbeing of people living with attributes that are the object of stigma. BPD is a serious mental illness characterized by pervasive psychosocial dysfunction including, problems regulating emotions and suicidality. This scoping review aimed to identify, map, and explore the international literature on structural stigma associated with BPD and its impact on healthcare for consumers with BPD, their carers/families, and health practitioners.

Methods

A comprehensive search of the literature encompassed MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Scopus, Cochrane Library, and JBI Evidence-Based databases (from inception to February 28th 2022). The search strategy also included grey literature searches and handsearching the references of included studies. Eligibility criteria included citations relevant to structural stigma associated with BPD and health and crisis care services. Quality appraisal of included citations were completed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool 2018 version (MMAT v.18), the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses Tool, and the AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting, and evaluation in health care tool. Thematic Analysis was used to inform data extraction, analysis, interpretation, and synthesis of the data.

Results

A total of 57 citations were included in the review comprising empirical peer-reviewed articles (n = 55), and reports (n = 2). Studies included quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, and systematic review designs. Review findings identified several extant macro- and micro-level structural mechanisms, challenges, and barriers contributing to BPD-related stigma in health systems. These structural factors have a substantial impact on health service access and care for BPD. Key themes that emerged from the data comprised: structural stigma and the BPD diagnosis and BPD-related stigma surrounding health and crisis care services.

Conclusion

Narrative synthesis of the findings provide evidence about the impact of structural stigma on healthcare for BPD. It is anticipated that results of this review will inform future research, policy, and practice to address BPD-related stigma in health systems, as well as approaches for improving the delivery of responsive health services and care for consumers with BPD and their carers/families.

Review Registration: Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/bhpg4).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13033-022-00558-3.

Keywords: Borderline personality disorder, Structural stigma, Health systems, Health services, Healthcare, Crisis care, Health practitioners, Consumers, Carers, Families

Background

Consumers with a diagnosis of BPD and their carers/families are often confronted with structural stigma when accessing health services for their mental health condition [1–4]. Structural stigma is defined as “the societal-level conditions, cultural norms, and institutional policies that constrain the opportunities, resources, and wellbeing of the stigmatized” ([5] p.742). Stigma is a multi-level phenomenon that occurs within various interpersonal, organisational, and structural contexts causing health inequities in accessing services and supports [5], and poor health outcomes [6] for consumers with BPD [3, 7–9] and their carers/families [1, 2, 10, 11]. BPD is a serious mental illness associated with longstanding and persistent patterns of instability in psychosocial functioning, including problems regulating emotions, self-image, interpersonal relationships, impulsivity, and suicidality [12]. The global lifetime prevalence of BPD is approximately 1–2% in the general population [13–16]; affecting 10% of consumers in outpatient settings, and up to 22% of consumers in inpatient settings [13, 17, 18].

BPD is a complex and contentious diagnosis [19], partly because evidence is yet to determine the exact cause of the condition. However, the trajectory is likely to be linked to genetic and environmental factors including emotional vulnerability, childhood abuse [20, 21], and insecure attachment. Some people with BPD may have experienced traumatic childhood events which can impact their ability to form healthy trusting relationships and develop the resilience needed to cope with the pressures of everyday life [22]. While trauma is not necessarily implicated in the suicidality (i.e., self-harm, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts) common in BPD [12], people with BPD are a high-risk group for suicide [23] which is often triggered by heightened emotions and repetitive cycles of intense distress and crises [24, 25]. Chesney et al. [26] conducted a meta-review on the risk for suicide mortality associated with major psychiatric disorders and found that the suicide risk among consumers with BPD was 45% greater than the general population, and disproportionately higher than other psychiatric disorders. Other studies investigating the prevalence of suicidality found that 75% of people with BPD attempted suicide [27], and up to 10% of people with BPD died by suicide [28].

Recurrent presentations to health services resulting from suicidality among this population place increased demand on health systems [27, 29]. This is particularly evident in emergency services; however, the care provided is often not adequate for meeting the complex needs of consumers with BPD [10]. A recent study investigating the prevalence of mental health presentations reported that consumers with personality disorders represented 20.5% of emergency service presentations and 26.6% of inpatient admissions. Further, consumers with personality disorders were 50% more likely to access health services while experiencing crisis within 28 days of their last presentation, relative to consumers with other mental health disorders [30]. Another study investigating health service utilization found that specialist psychotherapy services, day treatments, residential programs, outpatient, and inpatient medical services were accessed at higher rates by consumers with BPD, than by other consumers [29]. Findings from a community sample also found that 75% of people with BPD accessed help from a range of health professionals including physicians, therapists, and counsellors for their mental illness which may reflect the co-occurring disorders and complexity associated with BPD [31]. The high prevalence of chronic suicidality and crisis presentations to health services by consumers with BPD [15, 27, 28] has contributed to this disorder becoming one of the most highly stigmatized and marginalized mental health conditions in health systems [32, 33].

There is a growing body of research exploring the experiences of BPD-related stigma among consumers with BPD [3, 7–9, 34, 35] and their carers/families [1, 2, 11] when accessing health services. Consumers with BPD consistently report receiving suboptimal levels of care from health services including not being believed or dismissed in relation to the nature and severity of their presentation [3]. These experiences appear to stem from various misconceptions surrounding BPD and suicidality [36]. There are also reports of interactions of conflict between consumers with BPD, their carers/families, and health practitioners [37]. In some instances, consumers with BPD report that they are refused treatment when presenting to health services in distress [38, 39]. Carers/families of consumers with BPD report experiencing anxiety and grief associated with caring for their family member with BPD. Carers/families also experience substantial ongoing financial burdens [11, 40] associated with the costs of private health services including evidence-based therapies and hospitalization of the person with BPD for whom they provide care. Access to clinical and community-based services and supports for consumers with BPD and their carers/families are limited, with current services and supports not adequately meeting the demand for treatment of BPD [41], making it difficult for consumers with BPD and their carers/families to receive treatment and support when needed [3, 4].

There are also concerns regarding the capacity of existing health services to meet the complex needs of consumers with BPD and their carers/families [34, 35, 41, 42]. This stems from the insufficient allocation of resources and funds to support BPD-related research, health service provision [41, 43, 44], education and training, and supervision for health practitioners working with consumers with BPD [45–55]. In addition, there are concerns regarding some practitioners’ stigmatizing beliefs, attitudes, and practices towards BPD [38, 39, 54]. Ungar et al.’s [56] study examined mental health practitioners’ beliefs and attitudes to treating consumers with BPD and found that more than 80% of staff agreed that consumers with BPD were more difficult to work with than consumers with other mental health disorders. Deans et al.’s [57] study found that 89% of psychiatric nurses (n = 47) agreed with the statement that consumers with BPD are ‘manipulative’. These findings are consistent with other studies exploring health practitioners’ perceptions of BPD [58, 59].

While there is vast literature on the perceptions and experiences of stigma among consumers with BPD [3, 9, 34, 60–72], their carers/families [1, 2, 4, 10, 11, 40, 73], and health practitioners [19, 38, 51–55, 57, 74–91], currently there is limited knowledge about the structural mechanisms contributing to BPD-related stigma within health systems, and their impact on the delivery of services and care to consumers with BPD and their carers/families. Exploring the body of literature addressing stigma in relation to BPD will allow us to identify the existing structural problems in healthcare systems and inform recommendations for addressing these significant public health concerns [29].

Aim and research questions

The aim of this scoping review is to identify, map, and provide a broad overview of the international literature concerning structural stigma associated with BPD and its impact on healthcare for consumers with BPD, their carers/families, and health practitioners. This includes understanding how structures in health systems such as institutional policies, cultural norms, and organizational practices affect the availability and accessibility of quality health services and care for consumers with BPD and their carers/families. The primary research question addresses: How does structural stigma relevant to the diagnosis of BPD impact on the provision of health services and care for people with BPD, their carers/families, and health practitioners? Secondary research questions were also explored to gain a deeper understanding of the mechanisms, challenges, and barriers influencing BPD-related stigma in health systems. These were: (1) what are the perspectives and lived experiences of structural stigma among consumers with BPD, their carers/families, and health practitioners? (2) What are the specific drivers influencing the manifestation and perpetuation of BPD-related structural stigma in health systems, and the implications for research, policy, and practice? [92].

Methods

The scoping review was registered within the Open Science Framework (registration ID: (https://osf.io/bhpg4). A scoping review methodology was chosen to achieve the aim of this review based on its broad application to mapping, exploring, and synthesizing extant international literature and identifying gaps in knowledge [93]. Scoping review approaches are useful for understanding the complexity of concepts relating to healthcare and informing evidence-based practice [94]. The review process followed JBI guidelines for scoping reviews [95] and Arksey and O’Malley’s [96] five-step framework for scoping reviews: (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) charting data; and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results.

Identifying relevant studies

We undertook a comprehensive systematic search of electronic databases for peer-reviewed papers published from inception to February 28th 2022 using MEDLINE (Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCO Connect), PsycINFO (Ovid), Scopus (Elsevier), Cochrane Library (Wiley), and JBI Evidence-Based Database (Ovid). A search of grey literature using Google search engine was conducted to identify other relevant citations such as clinical practice guidelines for BPD. The references of included citations from both the peer-reviewed and grey literature searches were hand-searched to identify any additional relevant citations. Additional file 1 presents the PsycINFO search strategy and the grey literature key words. Search terms were developed as relevant to the three categories of key search terms: (a) BPD; (b) stigma; and (c) crisis care. Draft searches were executed in PsycINFO (Ovid) to test the search text word terms and subject heading combinations. Search terms were refined during iterative test searches resulting in a comprehensive search strategy to identify all existing peer-reviewed articles relating to BPD-related stigma associated with crisis presentations (i.e., a crisis relating to self-harm or suicidality) across various population groups (i.e., consumers with BPD, carers/families of people with BPD, and health practitioners) and healthcare settings (e.g., mental health and emergency services). Risk of selection bias was minimized by using multiple search methods. The eligibility criteria (Table 1), based on the Population-Concept-Context (PCC) framework [95], guided the study selection process during screening.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria

| Population, concept, context | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Population | Health practitioners including, psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, mental health nurses, general practitioners, primary care nurses, and other mental health workers who treat people with BPD in healthcare settings such as outpatients, inpatients, and community-based settings; people with BPD; carers/families of people with BPD |

| Concept | Structural stigma specific to BPD and crises (suicidality) |

| Context | International peer-reviewed studies investigating health practitioners’ attitudes and practice in treating people with BPD in healthcare settings; consumers with BPD or carers/families of people with BPD accessing healthcare |

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Articles were included if: | Articles were excluded if: |

| Evaluated health practitioners’ treating people with BPD in crisis in an outpatient, inpatient, and community-based setting; consumers with BPD or carers/families of people with BPD perspectives and experiences of healthcare | Evaluated health practitioners’ treating people with other mental illnesses; consumers with other mental illnesses; carers/families of people with other mental illness |

| Evaluated structural stigma as an outcome in healthcare settings | Not reporting outcomes specific to borderline personality disorder and structural stigma |

| Original research including peer-reviewed publications on quantitative, qualitative, mixed-methods, and review designs | Conducted in non-clinical settings such as educational institutions |

| Accessible for download free of charge | Studies of low quality |

| Written in English language only |

Study selection

All citations identified from the comprehensive search were collated and uploaded into Endnote V.9. Citations were then uploaded into Covidence and de-duplicated by the lead author (PK). Citation screening and selection were undertaken using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [97] (Additional file 2). Two independent reviewers (PK and AKF) screened the titles, abstracts, and full-text citations against the defined selection criteria to identify relevant studies. Full-text citations of selected studies were retrieved via Covidence and assessed against the inclusion criteria. Ineligible citations were omitted in accordance with the exclusion criteria (Table 1). Discrepancies in reviewer decisions regarding the inclusion of studies at both the title/abstract screening stage and the full-text stage were assessed and resolved by a third reviewer (SL) who had clinical expertise in mental health.

Charting the data

The type of information to be extracted from the eligible citations was discussed and consensus reached following meetings held by the research team (PK, AKF, SL). Data identified for inclusion in this review were extracted into a charting table. The charting table of included studies used the following fields: author, year, country; quality rating; population data; aim/purpose; study design; methods; and main findings (Table 2). Data extraction was led by the first author (PK) and checked and revised by the second author (AKF).

Table 2.

Data extraction of study characteristics on borderline personality disorder related structural stigma in healthcare systems

| Author, Year, Country | MMAT v.18*/ JBI quality ratinga | Population data | Aim/purpose | Study design | Methods/intervention | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Acres et al. 2019, AUS [10] |

JBI, Level 1.b/ Level 4b | Carers (N = 1891). Emergency care settings. Sources of evidence (N = 10): research studies (n = 7), advocacy brief (n = 1), clinical practice guideline (n = 1), action plan (n = 1) | Explore, locate, and compile literature detailing the perspectives of family carers of people with BPD in Emergency Departments (ED) with a focus on nursing practices | Scoping review | Review of the literature | Carers perceived ED as the only option for emergency care in a crisis. Carers require information on how to manage a crisis with their loved one. Carers are often not consulted with by health professionals; and perceive that health professionals lack understanding of consumers distress and BPD—a key barrier to effective crisis care |

|

Bodner et al. 2011, IL [76] |

*** | Health practitioners (N = 57): males (n = 35), females (n = 65) age, range (25–65 years old). Psychiatric hospital settings | Develop and use inventories that measure cognitive and emotional attitudes of health practitioners toward patients with BPD | Quantitative study | Surveys | Psychologists scored lower than psychiatrists and nurses on antagonistic judgments; nurses scored lower than psychiatrists and psychologists on empathy. Analyses conducted on the three emotional attitudes separately showed that suicidal tendencies of BPD patients explained negative emotions and difficulties in treating these patients |

|

Bodner et al. 2015, IL [77] |

**** | Health practitioners (N = 710): age, range (40–47 years old). Years of service, range (11–21 years). Psychiatric hospitals (N = 4) | Improve Bodner et al. [76] sample; inspect if nurses’ tendency to express more negative attitudes toward BPD is evident in a larger sample | Quantitative study | Surveys | Nurses and psychiatrists reported higher number of patients with BPD, exhibited more negative attitudes, and less empathy toward these patients than other professions. Negative attitudes were positively correlated with caring for greater numbers of patients with BPD. Nurses expressed the greatest interest in studying short-term methods; psychiatrists expressed interest in improving professional skills for BPD |

|

Borschmann et al. 2014, UK [7] |

**** | People with BPD (N = 41) males (n = 7, 17%), female (n = 34, 82%). Mean age (SD) 36, (11). Community services | Examine crisis care preferences of community-dwelling adults with BPD | Qualitative study | Thematic analysis of crisis plans | Participants gave clear statements in their crisis plans about the desire to recover from the crisis and improve their social functioning. Key themes included: the desire to be treated with dignity and respect; to receive emotional and practical support from clinicians; and preferences for treatment refusals during crises such as, psycho-tropic medication and involuntary treatment |

|

Buteau et al. 2008 [1] |

***** | Carers of people with BPD/ families (N = 12). Males (n = 2), and females (n = 10) | To learn from families what their experiences have been in four key areas: (1) knowledge about BPD, (2) BPD treatments, (3) coping with BPD, and (4) reasons for hope | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | Families identified five key areas of concern: (1) difficulty accessing current evidence-based knowledge about BPD/ treatments, (2) a stigmatizing health care system, (3) prolonged hopelessness, (4) shrinking social networks, and, (5) financial burdens. To improve the quality of services for families affected by BPD, social workers must educate themselves on BPD, BPD treatment options, information, and resources |

|

Carrotte et al. 2019, AUS [62] |

***** | A total of 12 participants comprising, people with BPD (n = 9), carers (n = 3) | Identify treatment and support services accessed by people with BPD and their carers; perceived benefits and challenges associated with these services; and recommended changes to services | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews, focus groups | Themes revealed: identity and discovery; (mis)communication; complexities of care; finding what works; an uncertain future; and carer empowerment. Participants described community-based psychotherapy as critical for reducing symptoms of BPD and improving services. Macro- and micro-levels relating to costs, service access, and clinician-client factors were discussed |

|

Clarke et al. 2015, UK [55] |

**** | Health practitioners (N = 44): years of service, range (1–10 years or more). Inpatient setting | To assess whether training in neurobiological underpinnings of BPD could improve knowledge and attitude change of staff | Within-subjects, quantitative survey design | Surveys relating to delivery of ‘The Science of BPD’ training |

Attendance at the training session was associated with significant increases in theoretical knowledge, perspective taking and mental health locus of origin. There were no changes observed in empathic concern. A brief training session utilizing a neurobiological framework can be effective in facilitating knowledge and attitudinal change among health practitioners working with BPD |

|

Commons Treloar et al. 2008, AUS [85] |

**** | Medical and health practitioners (N = 140). Males (n = 48), females (n = 92). Years of service, range (1–16 years). Emergency care, Mental health services settings | To assess the attitudes of clinicians towards patients diagnosed with BPD | Quantitative study | A purpose-designed survey | Significant differences were found among emergency medical and mental health staff in their attitudes to people with BPD. The strongest predictor of attitudes to self-harm were whether the practitioner worked in emergency medicine or mental health, years of experience, and training in BPD |

|

Commons Treloar et al. 2009a, AUS [84] |

***** | Medical and health practitioners (N = 140). Males (n = 48), females (n = 92). Emergency medicine, Mental health services settings (N = 3) | To explore health practitioners’ experiences and attitudes in working with patients with BPD | Qualitative study | Qualitative survey | Results revealed four themes: BPD patients generate an uncomfortable personal response in health practitioners, characteristics of BPD contribute to negative health practitioner/service responses, inadequacies of the health system in addressing BPD patient needs, and strategies needed to improve services for BPD. Findings suggest that interpersonal and system difficulties may have impacted the services for BPD |

|

Commons Treloar et al. 2009b, AUS [53] |

*** | Registered health practitioners (N = 65). Males (n = 26, 40%), females (n = 39, 60%). Years of service (1 year or more. Psychiatric hospital settings | To examine two theoretical educational frameworks (cognitive-behavioural and psychoanalytic), compared with no education to assess subsequent differences in health practitioners’ attitudes to deliberate self-harm behaviours in BPD | A randomized comparative quasi-experimental study | Surveys/‘cognitive behavioural therapy program’, ‘psychotherapy program’ training | Compared with participants in the control group (N = 22), participants in the cognitive-behavioural program (N = 18) showed significant improvement in attitudes after attending the training, as did participants in the psychoanalytic program (N = 25). At six-month follow-up, the psychoanalytic group maintained significant changes in attitude. Results support the use of brief educational interventions in sustaining attitude change to working with this population |

|

Day et al. 2018, AUS [86] |

*** | Mental health practitioners (N = 66). Males (n = 22, 33.3%), female (n = 44, 66.7%). Public health service settings | To investigate mental health practitioners’ attitudes to individuals with BPD where attitudes were compared over time | Longitudinal mixed methods design | Surveys, Semi-structured interviews | The 2000 sample (n = 33) endorsed more negative descriptions (e.g.,) ‘attention seeking’, ‘manipulative’), and the 2015 sample (n = 33) focused more on treatment approaches and skills (e.g.,) ‘management plan’, ‘empathy’). The 2015 sample endorsed more positive attitudes than the 2000 sample. This positive attitudinal shift may reflect a changing landscape of the mental health system and greater awareness and use of effective treatments |

|

Deans et al. 2006, AUS [57] |

**** | Registered psychiatric nurses (N = 47). Males (n = 14, 30%), females (n = 34, 70%). Age, range (21–60 years old). 15 years or more (53%) of service. Psychiatric inpatient and community services | To describe psychiatric nurses’ attitudes to individuals with BPD | Quantitative study | Survey | Results show that a proportion of psychiatric nurses' experience negative reactions and attitudes to people with BPD, perceiving them as manipulative, and feeling angry towards them. One third of nurses reported they ‘strongly disagreed’ or ‘disagreed’ that they know how to care for people with BPD |

|

Dickens et al. 2016, UK [52] |

JBI, Level 1.b/ Level 4b | Mental health nurses (N = 1197). 9 studies across 6 Countries | To collate evidence on interventions devised to improve the responses of mental health nurses to people with BPD | Systematic Review | Review of the literature | Eight studies were included in this review, half of which were judged to be methodologically weak, and the remaining four studies judged to be of moderate quality. Only one study employed a control group. The largest effect sizes were found for changes related to cognitive attitudes including knowledge; smaller effect sizes were found in relation to changes in affective outcomes. Mental health nurses hold the poorest attitudes to people with BPD |

|

Dickens et al. 2019, UK [51] |

**** | Mental health nurses (N = 28, training and pre-and post- surveys; N = 16, 4-month survey; N = 11, focus groups). Inpatient and community settings | To evaluate mental health nurses’ responses and experiences of an educational intervention for BPD | Mixed methods | Surveys, focus groups/‘positive about borderline’ training | Results revealed some sustained changes consistent with expected attitudinal gains in relation to the perceived treatment characteristics of this group, the perception of their suicidal tendencies and negative attitudes. Qualitative findings revealed hostility towards the underpinning biosocial model and positive appreciation for the involvement of an expert by experience |

|

Dunne & Rogers, 2013, UK [2] |

***** | Carers (N = 8). Community Personality Disorder Service | To explore carers’ experiences of the caring role, and mental health and community services | Qualitative study | Focus groups | The first carers’ focus group exploring the role of mental health services produced four super-ordinate themes. The second carers’ focus groups experiences in the community produced six super-ordinate themes. It seems carers of people with BPD are often overlooked by mental health services, and subsequently require more support to ensure their own well-being |

|

Ekdahl et al. 2015, SE [73] |

***** | Carers/ significant others (N = 19). Of the 19, 11 were involved in focus groups. Males (n = 5), females (n = 14). Age, range (43–75 years old). Psychiatric and health service settings | To describe significant others’ experiences of living close to a person with BPD and their experience of psychiatric care | Qualitative study | Qualitative survey, focus groups | Results revealed four categories: a life tiptoeing, powerlessness, guilt, and lifelong grief, feeling left out and abandoned, and lost trust. The first two categories describe the experience of living close to a person with BPD, and the last two categories describe encounters with psychiatric care |

|

Fallon 2003, UK [65] |

**** | People with BPD (N = 7). Psychiatric services | To analyse the perspectives and lived experiences of participants with BPD contact with psychiatric services | Qualitative study | Unstructured interviews | Results found that people with BPD valued contact with psychiatric services despite negative staff attitudes and experiences. Relationships with others was vital in containing their distress despite trusting issues. Overcoming this was achieved by consistent long-term involvement with staff, containing relationships, encouraging participants to contribute to their care, and improving understanding of BPD |

|

Hauck et al. 2013, USA [88] |

**** | Psychiatric nurses (N = 83) males (n = 8, 9.6%); females (n = 75, 90.3%). Age, range (21–65 years old). Psychiatric hospitals (N = 3) | To explore the attitudes of psychiatric nurses to patients with BPD experiencing self-harm | Descriptive, correlational design | Surveys | Psychiatric nurses had positive attitudes toward hospitalized BPD patients with deliberate self-harm. Psychiatric nurses with more years of nursing experience and self-reported need for further BPD education had more positive attitudes |

|

Horn et al. 2007, UK [68] |

***** | People with BPD (N = 5). Male (n = 1), female (n = 4). Age, range (23–44 years old). Mental health services | To explore user experiences and understandings of being given the diagnosis of BPD | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | Analysis identified five themes: knowledge as power, uncertainty about what the diagnosis meant, diagnosis as rejection, diagnosis is about not fitting, hope and the possibility of change. Positive and negative aspects to these themes were apparent |

|

James et al. 2007 IL [121] |

*** | Psychiatric nurses (N = 157) males (n = 21, 32%), females (n = 44, 68%) age, range (< 25- > 50) Years of service (< 2- > 15 years old). Various Psychiatric services | To describe the experiences and attitudes of nurses who deliver nursing care to people with BPD | Descriptive survey research design | Surveys | Results indicated that most nurses have regular contact with clients with BPD and nurses on inpatient units reported more frequent contact than nurses in the community. Eighty per cent of nurses viewed clients as more difficult to care for than other clients and believe that the care they receive is inadequate. Lack of services was the most important factor contributing to the inadequate care and the development of a specialist service as the most important to improve care |

|

Keuroghlian et al. 2006, USA [50] |

**** | Medical and health practitioners (N = 297). Males (n = 25, 25.3%), females (n = 75, 74.7%) Mean years of service (SD) (17 years old (12). Medical centres, hospitals | To assess the effectiveness of Good Psychiatric Management workshops at improving clinicians’ attitudes to BPD; to assess if attitude changes relate to years of experience; and, compare the magnitude of change after GPM workshops to those from STEPPS workshop | Pre-post (repeated measures) design | Surveys/‘good psychiatric management’ training | Participants reported a decrease in the inclination to avoid, or dislike, patients with BPD, and belief that the prognosis is hopeless. were Participants also reported increased feelings of professional competence, belief that they can make a positive difference, and that effective psychotherapies do exist. Findings demonstrate Good Psychiatric Management’s potential for training health practitioners to meet the needs of people with BPD |

|

Knaak et al. 2015, CA [49] |

*** | Health practitioners (N = 187) males (n = 28, 15%), female (n = 159, 85%. Mean age (39.1 years old). Mean years of service (22.2). Health services | To identify whether a generalist or specialist approach is the better strategy for anti-stigma programming for stigmatized disorders, and to examine the extent an intervention led to change in perceptions of people with BPD and mental illness | Pre-post design | Surveys/‘dialectical behaviour therapy’ training | Results suggest that the intervention was successful at improving healthcare provider attitudes and behavioural intentions towards persons with BPD. The results further suggest that anti-stigma interventions effective at combating stigma against a specific disorder may also have positive generalizable effects towards a broader set of mental illnesses |

|

Koehne et al. 2012, AUS [19] |

***** | Medical and health practitioners (N = 15). (Psychiatric hospitals (N = 3). Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services | Do mental health clinicians share diagnostic information about BPD with their adolescent clients, and if so, how? What are the factors that guide clinical practice in the decision to disclose or to withhold a diagnosis of emerging BPD to adolescents? | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | Findings found that doctors, nurses, and allied health practitioners resisted a diagnosis of BPD in their work with adolescents. We delineate specific social and discursive strategies that health practitioners displayed including: team rules discouraged diagnostic disclosure, the lexical strategy of hedging when using the diagnosis, the prohibition and utility of informal ‘borderline talk’ among health practitioners reframed the diagnosis with young people |

|

Lawn et al. 2015a, AUS [3] |

*** | People with BPD (N = 153). Age, range (18–65 years and older) | To explore the lived experiences of health service access from the perspective of Australians with BPD | Quantitative study | Survey | Responses from 153 consumers with BPD showed that they experience significant challenges and discrimination when accessing public and private health services. Seeking help from emergency departments during crises was challenging. Community support services were perceived as inadequate to meet patient needs |

|

Lawn et al., 2015b, AUS [4] |

*** | Carers (N = 121). Males (n = 24, 25.5%), female (n = 78, 76.5%). Age, range (mostly 50-60 s). Various health and community services settings | To explore their experiences of being carers, attempts to seek help for the person diagnosed with BPD, and their own carer needs | Quantitative study | Surveys | Responses from 121 carers found carers experience significant challenges and discrimination when accessing health services. Comparison with consumers’ experiences showed that carers/families understand the discrimination faced by people BPD, largely because they also experience exclusion and discrimination. Community carer support services were perceived as inadequate. General Practitioners (GP) were an important source of support however, service providers need more education and training to support attitudinal change that addresses discrimination, recognizes carers’ needs, and provides support |

|

Lohman 2017, USA [89] |

***** | People with BPD (N = 500)/ BPD Resource Centre | To build on the BPD services knowledge base by characterizing the experiences of consumers, caregivers, and family members seeking BPD resources | Qualitative study | Retrospective data analysis of brief unstructured interviews (N = 500)/ Data from resource centre transcripts (N = 6253) | Results found that primary services and resources requested were: outpatient services (51%) and educational materials (13%). Care-seekers identified family services, crisis intervention, and mental health literacy as areas where available resources did not meet demand. Factors identified as potential barriers to accessing appropriate treatment for BPD included stigmatization and marginalization within mental health system and financial concerns |

|

Ma et al. 2009, TW [109] |

***** | Mental health nurses (N = 15). Females (n = 15). Age, range (20- > 40). Years of service (4–10 years). Various health and community service settings | To explore the contributing factors and effects of Taiwan’s mental health nurses’ decision-making patterns on care outcomes for patients with BPD | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | The informants’ caring outcomes for BPD patients were involved with interactions across five themes: shifting from the honeymoon to chaos stage, nurses’ expectations for positive vs. negative outcomes, practicing routine vs. individualized care, adequate or inadequate support from healthcare teams and differences in care outcomes |

|

Markham 2003, UK [104] |

*** | Mental health nurses (N = 71). Males (n = 18), females (n = 47). Mental health inpatient facilities | To evaluate the effects of the BPD label on staff attitudes and perceptions | Repeated measures factorial design | Surveys | Registered mental health nurses expressed less social rejection towards patients with schizophrenia and perceived them to be less dangerous than patients with BPD. Staff were least optimistic about patients with a BPD and were more negative about their experience of working with this group compared to the other patient groups |

|

Markham et al. 2003, UK [122] |

*** | Mental health nurses (N = 48). Males (N = 12, 25%), females (N = 33, 69%). Mean age (SD), 38 (9.3). Mean years of service (SD), 12.7 (8.9). Mental health inpatient facilities | To investigate how the BPD label affects health practitioners’ perceptions and causal attributions about patients’ behaviour | Within-participants survey design | Survey | Patients with BPD attracted more negative responses from nurses than those with a label of schizophrenia. Causes of their behaviour were rated as more stable and they were thought to be more in control of their behaviour, then patients with other mental illnesses. Nurses reported less sympathy towards patients with BPD and rated their personal experiences as more negative than experienced with other patients |

|

Masland et al. 2018, USA [48] |

**** | Mental health practitioners, researchers (N = 193). Mean age (SD), 48.84 (13.47). Mean years of service (SD), 18.12, (12.37). Various health services | To examine if the 1-day training can change health practitioners’ attitudes to BPD, which persist over time | Repeated measures design | Surveys/‘good psychiatric management’ training | Staff attitudes did not change immediately after training, but 6-months later had changed significantly. Findings indicated that brief training fosters improvements in health practitioners’ attitudes and beliefs about BPD |

|

McGrath et al. 2012, IE [110] |

***** | Registered psychiatric nurses (N = 17). Males (n = 5), females (n = 12). Mean years of service (n = 16). Community mental health service settings | To identify themes from an analysis of the nurses’ interactions with people with BPD, and to describe their level of empathy to this patient group | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | Results found four themes: challenging and difficult, manipulative, destructive and threatening behaviour, preying on the vulnerable resulting in splitting staff and service users, and boundaries and structure. Low levels of empathy were evident in most participants’ responses to the staff-patient interaction response scale. Findings provide further insight on nurses’ empathy responses and views on caring for people with BPD |

|

Millar 2012, SC [119] |

**** | Psychologists (N = 16). Females (n = 16). Years of service, range (1–32 years) | To explore psychologists’ experiences and perceptions of clients with BPD | Qualitative study | Focus groups | The following themes emerged from the analysis: negative perceptions of the client, undesirable feelings in the psychologist, positive perceptions of the client, desirable feelings in the psychologist, awareness of negativity, trying to make sense of the chaos, working in contrast to the system, and improving our role |

|

Morris 2014, UK [111] |

***** | People with BPD (N = 9). Males (n = 2), females (n = 7). Age, range (18–65 years old). Various voluntary sector organisations in the North-West of England | To explore people with BPD’s experience of mental health services to understand what aspects of services are helpful | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | Three themes were generated including: the diagnostic process influences how service users feel about BPD, non-caring care, and it’s all about the relationship. Participants identified practical points which services could implement to improve the experiences of service users |

|

National Health and Medical Research Council 2012, AUS [16] |

Agree II Instrument level 6 | Health practitioners | To provide current evidence for the effective treatment to improve the diagnosis and care of people with BPD in healthcare services in Australia | Clinical guidelines | Treatment and crisis management | Health professionals at all levels of the healthcare system and within each type of health service should recognize that BPD treatment is a legitimate use of healthcare services. Having BPD should never be used as a reason to refuse health care to a person. A tailored management plan, including crisis plan, should be developed for all people with BPD who are accessing health services |

|

Nehls 1999, USA [112] |

***** | People with BPD (N = 30). 30 Females (N = 30). Psychiatric, outpatient, and community services | To generate knowledge about the experience of living with the diagnosis of BPD | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | Three themes were identified: living with a label, living with self-destructive behaviour perceived as manipulation, and living with limited access to care. The findings suggest that mental health care for persons with BPD could be improved by confronting prejudice, understanding self-harm, and safeguarding opportunities for dialogue |

|

Nehls 2000, USA [113] |

***** | Case managers (N = 17). Community mental health centre | To study the day-to-day experiences of case managers who care for persons with borderline personality disorder | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | The analysis showed a pattern of monitoring self-involvement. The case managers monitored themselves in terms of expressing concern and setting boundaries. These practices highlight a central and unique component of being a case manager for persons with BPD, that is, the case manager's focus of attention is on self. By focusing on the self, case managers seek to retain control of the nature of the relationship |

|

Ng 2016, AUS [123] |

JBI, Level 1.b/ Level 4b | People with BPD (N = 1122), carers and health practitioners’ perspectives reflected in consumer studies | To review the literature on symptomatic and personal recovery from BPD | Systematic review | Review of the literature | There were 19 studies, representing 11 unique cohorts meeting the review criteria. There was a limited focus on personal recovery and the views of family and carers were absent from the literature. Stigma associated with the diagnostic label hindered trust formation and consumers ability to fully engage |

|

O’Connell 2013, IE [120] |

*** | Community psychiatric nurses (N = 15). Years of service, range (3–15 years). Irish adult community mental health service | To explore the experience of psychiatric nurses who work in the community caring for clients with BPD | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | The nurses’ understanding of BPD and their experiences of caring for individuals with the condition varied. Participants identified specific skills required when working with clients, but the absence of supervision for nurses was a particular difficulty, and training on BPD was lacking |

|

Perseius et al. 2005, SE [8] |

***** | People with BPD (N = 10) age, range (22–49 years old) | To investigate life situations, suffering, and perceptions of encounters with psychiatric care among patients with BPD | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | Findings revealed three themes: life on the edge, the struggle for health and dignity, a balance act on a slack wire over a volcano, and the good and the bad act of psychiatric care in the drama of suffering. Theme formed movement back and forth, from despair and unendurable suffering to struggle for health and dignity and a life worth living |

|

Pigot et al. 2019, AUS [47] |

***** | Mental health practitioners (N = 21). Males (n=10), female (n = 11). Mean age, 39.5 (9.7). Public mental health services | To understand the facilitators and barriers to implementation of a stepped care approach to treating personality disorders | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews /‘stepped care approach’ training | Participants identified personal attitudes, knowledge, and skills as important for successful implementation. Existing positive attitudes and beliefs about treating people with a personality disorder contributed to the emergence of clinical champions. Training facilitated positive attitudes by justifying the psychological approach. Findings suggests specific organizational and individual factors may increase timely and efficient implementation of interventions for people with BPD |

|

Proctor et al. 2020, AUS [106] |

*** | People with BPD (N = 577), comprising 153 consumers in 2011, and 424 consumers in 2017 | To understand Australian consumer perspectives regarding BPD | Quantitative study | Surveys | Many people diagnosed with BPD experience difficulties when seeking help, stigma within health services, and barriers to treatment. Improved general awareness, communication, and understanding of BPD from consumers and health professionals were evident |

|

Ring et al. 2019, AUS [34] |

JBI, Level 1.b/ Level 4b | People with BPD (N = 12), Health practitioners (N = 18) across 30 studies in total | To compare and contrast what stigma looks like within mental health care contexts, from the perspective of patients and mental health professionals’ and how it is perpetuated at the interface of care | Literature review | Review of the literature | Thirty studies were found: 12 on patient’s perspectives and 18 on clinician’s perspectives. Six themes arose from the thematic synthesis: stigma related to diagnosis and disclosure, perceived un-treatability, stigma as a response to feeling powerless, stigma due to preconceptions of patients, low BPD health literacy, and overcoming stigma through enhanced empathy. A conceptual framework for explaining the perpetuation of stigma and BPD is proposed |

|

Rogers 2012, UK [69] |

***** | People with BPD (N = 7). Male (n = 1), female (n = 5) age, range (22–66 years old) | To explore the experience of service users being treated with medication for the BPD diagnosis | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | The main themes to emerged were: staff knowledge and attitudes, lack of resources and the recovery pathway for BPD. Service users felt that receiving the BPD diagnosis had a negative impact on the care they received, with staff either refusing treatment or focusing on medication as a treatment option. The introduction of specialist services for this group appears to improve service user satisfaction with treatment and adherence to the National Institute for Clinical Excellence guidelines |

|

Shaikh et al. 2017, USA [33] |

JBI, Level 1.b/ Level 4 | Health practitioners (N = 5136). 56 studies. Emergency care | To review the advice to physicians and health-care providers who face challenging BPD patients in the ED | Systematic review | Review of the literature | Results found that crisis intervention should be the first objective of health practitioners when dealing with these patients in emergency departments. Risk management processes and developing a positive attitude and empathy towards these patients will help them in normalizing in an emergency setting after which treatment course can be decided |

|

Sitsti 2016, USA [108] |

**** | Psychiatrists (N = 134). Male (n = 88, 65.7%), females, (n = 46, 34.3%). Years of service, range (0- > 20). Psychiatric services | To examine whether Psychiatrists had ever withheld/not documented patients’ BPD diagnosis | Quantitative study | Survey | Fifty-seven percent of participants indicated that they failed to disclose BPD to their patients, and 37 percent said they had not documented the diagnosis. For those respondents with a history of not disclosing or documenting BPD, most agreed that either stigma or uncertainty of diagnosis played a role in decisions |

|

Stapleton et al. 2019, UK [71] |

JBI, Level 1.b/ Level 4 | People with BPD (N = 90) across all 8 studies. Age, range between 21 and 61 years. Acute Psychiatric inpatient wards | To conduct a meta-synthesis of qualitative research exploring the experiences of people with BPD on acute psychiatric inpatient wards | Meta-synthesis | Review of the literature | Eight primary studies met the inclusion criteria. Four themes included: contact with staff and fellow inpatients, staff attitudes and knowledge, admission as a refuge, and the admission and discharge journey. Opportunities to be listened to and to talk to staff and fellow inpatients, time-out from daily life and feelings of safety and control were perceived as positive elements of inpatient care. Negative experiences were attributed to a lack of contact with staff, negative staff attitudes, staff’s lack of knowledge on BPD, coercive involuntary admission, and poor discharge planning |

|

Stroud et al. 2013, UK [39] |

***** | Registered Community Mental Health Nurses (N = 4). Male (n = 1, female (n = 3). Age range (30–59 years old). Community Mental Health team | To gain a fuller understanding of how community psychiatric nurses make sense of the diagnosis of BPD and how their constructs of BPD impact their approach to this client group | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | Results suggested that participants ascribe meaning to the client’s presentation ‘in the moment’. When they had a framework to explain behaviour, participants were more likely to express positive attitudes. As participants were deriving meaning ‘in the moment’, there could be fluidity with regards to participants’ attitudes, ranging from ‘dread’ to a ‘desire to help’, and leading participants to shift between ‘connected’ and ‘disconnected’ interactions |

|

Sulzer 2015, USA [114] |

***** | Mental health practitioners (N = 22). Inpatient and out-patient settings | To evaluate how health practitioners describe patients with BPD, how the diagnosis affects the treatment provided, and the implications for patients | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | Findings suggest patients with BPD are routinely labelled difficult, and subsequently routed out of care through a variety of direct and indirect means. This process creates a functional form of demedicalization where the actual diagnosis of BPD remains de jure medicalized, but the treatment component of medicalization is harder to secure for patients |

|

Sulzer 2016a, USA [115] |

***** | Mental health practitioners (N = 22). BPD activists | To understand how health practitioners communicate the diagnosis of BPD with patients, and to compare and evaluate these practices with patient communication preferences | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | Most participants sampled did not actively share the BPD diagnosis with their patients, even when they felt it was the most appropriate diagnosis. Most patients wanted to be told that they had the disorder, as well as have their providers discuss the stigma they would face. Patients who later discovered that their diagnosis had been withheld consistently left treatment |

|

Sulzer 2016b, USA [118] |

**** | Mental health practitioners (N = 39). Men (n = 15), female (n = 24). Various public and private health services | To examine how clinicians navigate providing treatment to BPD in the context of the DSM 5, deinstitutionalization, and the biomedical model | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | Health practitioners faced pressures to focus on biomedical treatments. Treatments which emphasized pharmaceuticals and short courses of care were ill-suited compared to long-term therapeutic interventions. This contradiction is the ‘biomedical mismatch’; Gidden's concept of structuration is used to understand how health practitioners navigate care. Social factors such as, stigma and trauma, are insufficiently represented in the biomedical model of care for BPD |

|

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2009 UK [107] |

Agree II Instrument level 5 | Targeting Health practitioners | To advise on the treatment and management of BPD | Clinical guidelines | Treatment and crisis management | Findings provide evidence-based guidance on interventions for health practitioners supporting people with BPD and families/carers. People with BPD should not be excluded from accessing health services because of their diagnosis or suicidality. Health practitioners should build a trusting relationship, work in an open, engaging, and non-judgmental manner, and be consistent and reliable when working with people with BPD and carers |

|

Vandyk et al. 2019, CA [117] |

***** | People with BPD (N = 6). Emergency care settings | To explore the experiences of persons who frequently present to the ED for mental health-related reasons | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | Two broad themes included: the cyclic nature of ED use, coping skills and strategies. Unstable community management that leads to crisis presentation to the ED often perpetuated access by participants. Participants identified a desire for human interaction, feelings of loneliness, lack of community resources, safety concerns following suicidality as the main drivers for visiting ED. Participants identified strategies to protect themselves against unnecessary ED use and improve health |

|

Veysey 2014, NZ [72] |

***** | People with a BPD (N = 8). Male (n = 2), female (n = 7). Age, range (25–65) | To explore people with BPD encounters of discriminatory experiences from healthcare professionals | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | Themes found that discriminatory experiences contributed to participants’ negative self-image and negative messages about the BPD label. A history of self-harm appeared to be related to an increased number of discriminatory experiences. Connecting with the person and ‘seeing more’ beyond an individual’s diagnosis and/or behaviour epitomized helpful experiences |

|

Warrender 2015, UK [45] |

***** | Nurses (N = 9). Acute mental health wards, hospital setting (N = 1). Health services | To capture staff perceptions of the impact of health. Mentalization-based therapy skills training on their practice when working with people BPD in acute mental health | Qualitative study | Focus groups/‘mentalization-based therapy skills training | Mentalization-based Therapy Skills training promoted empathy and humane responses to self-harm, impacted on participants ability to tolerate risk and changed some perceptions of BPD. Staff felt empowered and more confident working with people with BPD. The positive implication for practice was the ease in which the approach was adopted and participants perception of Mentalization-based Therapy skills as an empowering skill set which also contributed to attitudinal change |

|

Warrender et al. 2020, UK [35] |

JBI, Level 1.b/ Level 4 | Health practitioners 46 studies. A total of N = 3714 participants comprising: people with BPD (n = 2345), carers (n = 184), Health practitioners (n = 1185). Various healthcare settings | To explore the experiences of stakeholders involved in the crisis care of people diagnosed with BPD | Integrative review | Systematic review of the literature | Four themes: crisis as a recurrent multidimensional cycle, variations and dynamics impacting on crisis intervention, impact of interpersonal dynamics and communication on crisis, and balancing decision making and responsibility in managing crisis |

|

Wlodarczyk et al. 2018 AUS [42] |

***** | A total of 22 participants comprising GP (N = 12); research team (n = 5); People with BPD (n = 2); Carers, 3. GPs: males (n = 6), females (n = 6). GP Partners Australia | To explore the nature and difficulties for GP, examine the reasons that caring for people with BPD in primary care is difficult and not well managed, and explore what strategies and actions might assist with improving the care of their patients with BPD | Qualitative study | Focus groups | Key themes identified were: challenges regarding the BPD diagnosis, clinical complexity, the GP–patient relationship, and navigating systems for support. Health service pathways are dependent on the quality of care provided and GP capacity to identify and understand BPD. GP need support to develop the skills necessary to provide effective care for BPD patients. Structural barriers obstructing attempts to address patients with BPD were discussed |

|

Woollaston et al. 2008, UK [116] |

***** | Nurses (N = 6). Males (n = 4), females (n = 2). Age, range (20–40 years old). Years of service, range (2–17 years). Various hospital and community health services (N = 6) | To explore nurses’ relationships with BPD patients from their own perspective | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | Results identified the following themes: destructive whirlwind’, idealized and demonized, and manipulation and threatening. The study concludes that nurses experience BPD patients negatively. This can be attributed to the unpleasant interactions they have with them and feeling that they lack the necessary skills to work with this group. Nurses report that they want to improve their relationships with BPD patients |

BPD Borderline Personality Disorder, ED Emergency department

aMMAT v.18 quality rating: low = 1* to 2** stars; moderate = 3*** stars; moderately high = 4**** stars; high = 5***** stars[97]

bJBI Quality rating for level of evidence for effectiveness is level 1.b systematic review of RCTs and other study designs; and the level of meaningfulness is 4—systematic reviews of expert opinion[120]

cAgree II Instrument quality rating scale [99]: 1 = lowest possible quality, through to, 7 = highest possible quality

Quality appraisal

Quality appraisal of all citations was undertaken to reduce the risk of bias. The MMAT v.18 checklist [98] was used to determine methodological quality of the quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods studies for inclusion in this review. The JBI Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses tool [99] was used to appraise methodological rigor of the reviews; the AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting, and evaluation in health care tool [100] was used to appraise the Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of BPD (referred to as Guidelines) [16]. Meetings were held by the research team (PK, AKF, SL) to discuss the application of items within the quality appraisal tools and processes for assessing the methodological quality of the included citations. This included establishing an agreed cut-off criteria to exclude low quality studies in accordance with the eligibility criteria. Initially, one reviewer (PK) conducted the quality appraisals of the citations. Two reviewers (PK and AKF) then met to review the quality appraisals of the studies and highlight any concerns; where issues were identified, resolution was achieved through discussion. Although a third reviewer (SL) was available to resolve any discrepancies, no further resolution was required.

Collating and summarizing findings

Data were collated, analysed, and synthesized using Braun and Clarke’s [101] Thematic Analysis. Results of the review were synthesized into a narrative summary of the study aims, research questions, and eligibility criteria (PCC). Data analyses involved: (1) quantitative data being summarized using descriptive statistics and frequencies [102]; and (2) Thematic Analysis of qualitative data to organize, categorize, and interpret key themes and patterns emerging from the data [101]. Trustworthiness and rigor of data abstraction and synthesis were established using a data analysis table that captured the categories, codes, and key findings/themes on the impact of structural stigma on healthcare for consumers with BPD, their carers/families, and health practitioners. Triangulating the perspectives and lived experiences of the relevant populations (i.e., consumers with BPD, their carers/families, and health practitioners) has been identified as an effective approach to establishing a comprehensive understanding of the complex nature of health systems [103].

Results

Data characteristics

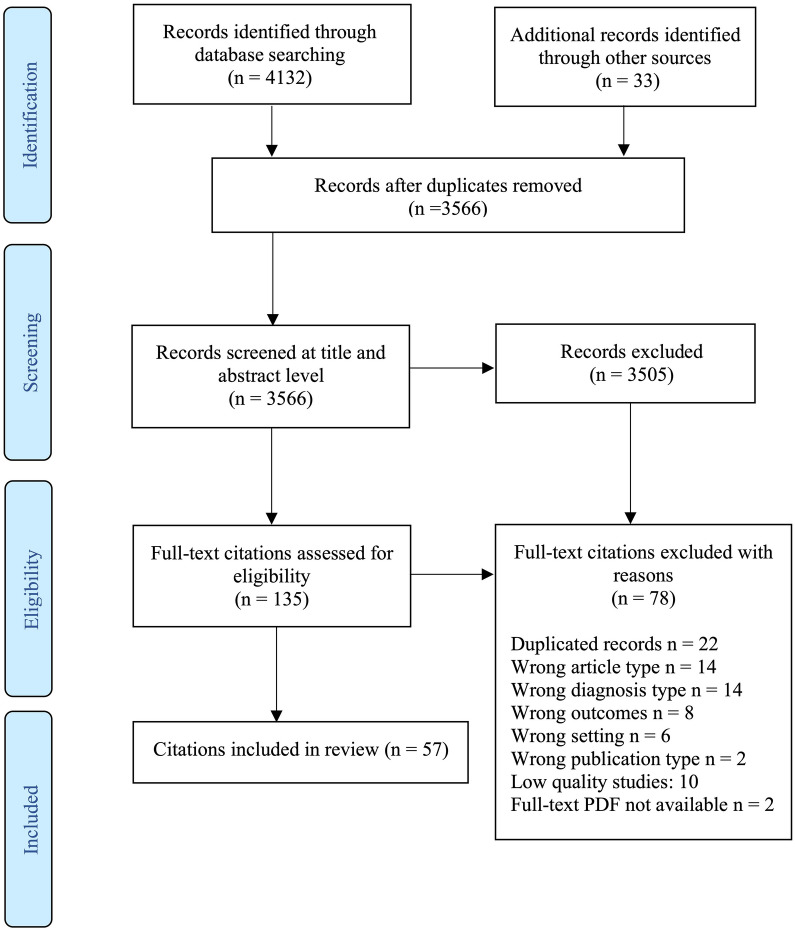

The initial database searches yielded 4132 publications. An additional 33 (n = 33) records were identified via other sources. Following the removal of duplicates, citation titles and abstracts were screened (n = 3566), and full-text records (n = 135) were retrieved and assessed for eligibility. Of these records, 78 (n = 78) were excluded when assessed against the inclusion criteria and the quality appraisal criteria. In total, 57 (n = 57) citations that aligned with the inclusion criteria and study aims were incorporated into this review. Search results including reasons citations were excluded are presented in a PRISMA Flow Diagram (Fig. 1). Most of the citations comprised peer-reviewed published studies (n = 55), and two (n = 2) non-published reports. The majority of the citations examined health practitioners' stigmatizing attitudes and practice specific to BPD (n = 36, 63%). Some citations focused on BPD-related educational interventions designed to modify health practitioners' attitudes and practice in treating BPD (n = 9, 5%) [45, 47–53, 55]. Table 2 presents data characteristics of included citations. Table 3 summarizes study characteristics of included studies.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart of the selection of citations for the scoping review

Table 3.

Summary of key study characteristics

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | 17,406 | 100 |

| Study methodologies | ||

| Quantitative studies | 18 | 32.0 |

| Qualitative studies | 28 | 49.0 |

| Mixed methods study | 2 | 3.5 |

| Reviews/meta-synthesis | 7 | 12.0 |

| Clinical practice guidelines | 2 | 3.5 |

| Countries | ||

| Australia | 16 | 28.0 |

| Israel | 3 | 5.0 |

| United Kingdom | 17 | 30.0 |

| Sweden | 2 | 3.3 |

| United States of America | 11 | 19.0 |

| Canada | 2 | 3.3 |

| New Zealand | 1 | 2.0 |

| Ireland | 2 | 3.3 |

| Scotland | 1 | 2.0 |

| Taiwan | 1 | 2.0 |

| Unknown | 1 | 2.0 |

| Population groupsa | ||

| Health practitioners | 37 | 65.0 |

| Consumers with BPD | 15 | 25.0 |

| Carers/families | 6 | 10.0 |

| Healthcare settings | ||

| Mental health services | 19 | 31.0 |

| Emergency departments | 13 | 21.0 |

| General hospital and health services | 14 | 24.0 |

| Community-based services | 14 | 24.0 |

| Health professions | ||

| Medicine/psychiatry | 18 | 30.0 |

| Nursing | 26 | 42.0 |

| Allied health | 17 | 28.0 |

aSome citations included more than one population group, healthcare setting, and health profession

Methodological quality

Critical appraisal of all included citations found that the quality ratings of the quantitative studies were moderate (n = 9), [3, 4, 49, 53, 76, 104–107], and moderately high (n = 8) [48, 50, 55, 57, 77, 85, 88, 108]. The quality of most qualitative studies was rated as high (n = 24) [1, 2, 8, 19, 39, 42, 45, 47, 62, 68, 69, 72, 73, 84, 89, 109–117], or moderately high in quality (n = 4) [7, 65, 118, 119]. One (n = 1) qualitative study was deemed moderate in quality [120]. The quality of the mixed methods studies (n = 2) was determined as moderate [86] and moderately high [51].

Reviews were of moderate (n = 6) [10, 33, 35, 52, 71, 123], or high quality (n = 1) [34], and reports were moderately high in quality (n = 2) [16, 107] (Table 2).

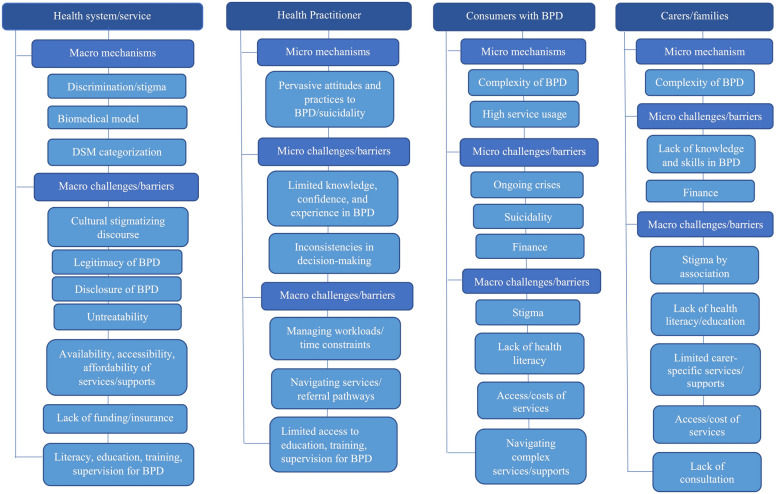

Key findings

Synthesis of the review findings identified several extant macro- and micro-level structural mechanisms, challenges, and barriers associated with BPD-related stigma in health systems. Structural problems that contribute to BPD-related stigma were evident across multiple levels of the health sector including system/service-, practitioner-, and consumer-levels. These results highlight the complex and contentious nature of BPD and healthcare across the following broad themes (and sub-themes) comprising: structural stigma and the BPD diagnosis (subthemes—legitimacy of the BPD diagnosis, reluctance to disclose a BPD diagnosis, discourse of untreatability); BPD-related stigma surrounding health and crisis care services (subthemes—BPD and healthcare, practitioner-consumer interactions). Each of these themes and subthemes are discussed below.

Structural stigma and the BPD diagnosis

This theme is centred around the dominant stigma discourse and misconceptions within health systems regarding the BPD diagnosis, its disclosure to the consumer, treatment options, and prognosis for recovery from the perspectives of health practitioners [16, 19, 33, 34, 108, 114, 115, 118, 119, 123], consumers with BPD [3, 34, 62, 68, 111, 112, 123], and carers/families [4, 10, 62, 123]. The main structural challenges and barriers associated with the diagnosis of BPD in health systems include: uncertainty whether BPD is a legitimate mental illness [19, 84, 114–116, 118]; concerns regarding the disclosure of a BPD diagnosis [65, 108, 115]; and perceptions that BPD is an untreatable condition [114, 116, 118]. Consequently, consumers with BPD are often denied evidence-based treatment [3, 4, 114, 115, 118] and routed out of the health system through a process called de-medicalization—making it difficult for these consumers to access health services and support [114].

Legitimacy of the BPD diagnosis

The BPD diagnosis and its legitimacy as a serious mental illness is actively contested in some health systems [19, 35, 114], which can create barriers to consumers with BPD accessing health services [16, 107]. Sulzer et al.’s [114] qualitative study found that some health practitioners viewed consumers with BPD from a moral stance, rather than the consumer being genuinely unwell; and consequently denied these consumers treatment. For instance, participants described consumers with BPD as morally deviant and viewed self-harming behaviour as attention-seeking, rather than perceiving it as a symptom of their underlying mental illness and associated distress. Nehls et al.’s [112] qualitative study suggest that some health practitioners held misconceptions regarding the disorder such as associating it with a flaw in character, rather than it being a legitimate illness. Health practitioners also believed consumers with BPD were responsible for their presentation and more in control of their actions than consumers with other mental health conditions [112, 114]. These misconceptions regarding the validity and reliability of the BPD diagnosis historically stem partly from the separation of BPD (and all personality disorders) into Axis II of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) [12]. This distinguished BPD from other mental health disorders such as schizophrenia which we understand has a clear biological aetiology and response to psychoactive medication [114]. Psychiatrists working with adolescents in Child and Mental Health Services also expressed concerns regarding the legitimacy of the BPD diagnosis for adolescents given the DSM criteria are adult-specific and do not account for the developmental stages of adolescents [19].

Consumers with BPD [3, 7, 65, 69, 71, 72, 112, 117] and their carers/families [1, 2, 4, 10, 42, 62, 73, 123] have consistently reported experiencing discrimination and stigma from health services in response to the BPD diagnosis. Lawn et al.’s [3, 4] quantitative studies found that consumers with BPD reported experiencing high levels of anxiety associated with ‘discrimination due to their BPD diagnosis’ (58%, n = 67) and ‘not being taken seriously’ (71%, n = 82) by health practitioners. Carers/families of people with BPD also reported that they were not taken seriously by practitioners (60.5%, n = 46/77). Carers/families also perceived the discrimination towards the BPD diagnosis (53%, n = 36), and not being taken seriously (44%, n = 30) as major barriers to accessing health services and support. These discriminatory experiences are contrary to best practice guidelines for the treatment and management of BPD [16, 107] which describes the disorder as a valid mental illness with effective treatments available and a legitimate use of healthcare resources. These guidelines also advise against discrimination or withholding treatment based on the presence of a BPD diagnosis.

Reluctance to disclose a BPD diagnosis

Studies examining BPD-related stigma in health systems have highlighted some health practitioners reluctance to disclose a BPD diagnosis to consumers [33, 34, 108, 114, 118, 123]. Sisti and colleague [108] undertook a quantitative survey and found more than half of psychiatrists (57%, n = 77) participating in the study chose not to disclose a BPD diagnosis to their patients; over a third of psychiatrists (37%, n = 49) did not document the diagnosis in their patient’s medical charts. Respondents in this study reported stigma (43%) and uncertainty regarding the diagnosis (60%) as the reasons for withholding a BPD diagnosis from patients. Respondents (n = 12) in Lawn et al.’s [3] survey suggested that family doctors (General Practitioners) did not appear to take notes on BPD or recognize the disorder. Koehne et al.’s [19] qualitative study explored health practitioners diagnostic and disclosure practices for adolescent patients and found that practitioners decisions regarding diagnostic disclosure were often influenced by cultural norms embedded within their professional teams. Findings further indicated that some health practitioners may use discursive strategies to avoid disclosing the diagnosis to their patients such as hedging (i.e., vague terms used to distance from the discussion at hand) and reframing the condition in terms of emerging traits, rather than naming the diagnosis.

Similarly, Sulzer et al. [115] found most health practitioners (81%, n = 32) diagnosed patients with an alternative disorder such as post-traumatic stress disorder or depression. Practitioners' reported reasons for providing patients with an alternative diagnosis included: fear of patient rejecting the diagnosis; protecting patient from stigma, shame, and blame associated with the disorder; and, enhancing patients' likelihood of receiving appropriate treatment for their mental health condition. These findings are consistent with consumer responses reported in this study, which indicated that they had not been informed about the BPD diagnosis by their health practitioner at the time of the diagnosis. Only a few health practitioners (9%) reported fully disclosing a BPD diagnosis to their patients. The reasons these participants gave for disclosing the diagnosis was to ensure that they were complying with their professional duties regarding informed consent for treatment, and to enable consumers to access appropriate treatment for their specific needs.

Contrary to health practitioners beliefs, some consumers with BPD in Sulzer et al.’s [115] study (n = 29) reported that they wanted to be informed of their diagnosis and discuss the disorder and its associated stigma with their health practitioner. Most consumers stated that they experienced relief when they received the diagnosis, and that they found the diagnostic process therapeutic. Few consumers (n = 3) reacted negatively to receiving a BPD diagnosis. These findings are consistent with other studies reporting that consumers with BPD appreciate being informed about the diagnosis by their health practitioner [34, 62]. In addition, Morris et al.’s [111] qualitative study suggested that the way in which people are diagnosed and informed about the diagnosis impacts how they feel about BPD. Consumers who were informed of their BPD diagnosis by a health practitioner that was optimistic about effective treatment and recovery prospects were more likely to feel positive about BPD than consumers who had a negative experience learning about their diagnosis. Further, Sulzer et al. [115] observed that some consumers with BPD whose health practitioner did not openly discuss their diagnosis with them subsequently disengaged with treatment.

Consumers with BPD also reported that receiving BPD-related information and education from their health practitioner was helpful [111, 112] as it assisted them to understand their symptoms and behaviours [65], and to see their condition from a disease perspective rather than as a personality flaw [34]. Other studies highlighted the importance of receiving adequate information about BPD from health practitioners; consumers who did not receive sufficient education showed limited knowledge and understanding of BPD [3, 68]. This experience may be relatively common given the findings of Lawn et al. [3] that 37.8% (n = 45/119) of consumers with BPD reported that they had not received any information from practitioners about what the BPD diagnosis means, and 19.3% (n = 23) of respondents stated that the diagnosis had been explained but they had not understood the information provided. These practices present major structural challenges and barriers to consumers with BPD as they prevent them from having adequate knowledge with which to understand their symptoms, as well as knowledge regarding treatment options to support them with their specific needs [16, 107].

Discourse of untreatability

The dominant biomedical approach to healthcare has been identified as an important structural mechanism driving the challenges and barriers to responsive services and care for BPD. Debates in the literature regarding the effectiveness of biomedical approaches for treating BPD, which rely upon conventional treatments such as medication and short-term intervention rather than longer-term therapy and support, are viewed by many health practitioners as ill-suited [118, 119]. Social factors contributing to stigma and trauma are not considered in the biomedical approach, and have consequently created the unintentional downstream effects of short-term crisis interventions, repetitive crisis presentations, and readmissions to hospital [118]. The inadequacy of the biomedical model to effectively respond to the complex needs of consumers with BPD is evident from their high rates of health service utilization, predominantly primary, emergency, and mental health services [118, 123]. However, health practitioners working with this population experience considerable pressure to align their practice to the dominant biomedical approach [118], despite the challenges associated with treatment, perceptions of poor prognosis, and recovery pathways for BPD [16, 34, 35, 39, 50–53, 57, 76, 77, 84–86, 104, 105, 107, 109, 110, 113, 116, 118, 119, 122].

Sulzer et al.’s [118] qualitative study suggests that some health practitioners avoid working with consumers with BPD based on the misconception that BPD is not treatable as it is not responsive to psychotropic medication. Another qualitative study [84] found that some health practitioners were less likely to provide an objective assessment of consumers' needs when BPD was present, and refused to treat consumers with BPD. Alarmingly, a few health practitioners (n = 2) [110] revealed that they avoided providing any (or minimal) level of care to consumers with BPD. These findings are consistent with reports of health practitioners witnessing their colleagues refusing to treat consumers with BPD [84]. Consistent with this, several studies (n = 9) reported consumers’ with BPD [3, 7, 62, 65, 68, 89, 111, 112, 118] and carers/families of people with BPD [4] being denied treatment by health practitioners when attempting to access health services and support. Consumers with BPD described their experiences of being denied treatment by health practitioners as distressing [16, 106], and that health practitioners’ preconceived ideas and attitudes to BPD left them feeling "labelled and judged" rather than, "diagnosed and treated" for their mental health condition ([112] p.288). Consumers with BPD also stated that although they believed receiving a diagnosis of BPD was useful in guiding treatment at times, the BPD diagnosis affected their treatment and recovery prospects [112]. These findings suggest that the myths concerning the untreatable nature of BPD persists to impact practice (i.e., denying treatment) despite evidence of effective treatments for BPD such as Dialectical Behavioural Therapy, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, and mentalization based approaches [16, 107, 114].

BPD-related stigma surrounding health and crisis care services

BPD and healthcare