Abstract

# Background

Though several environmental and demographic factors would suggest a high burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in most African countries, there is insufficient country-level synthesis to guide public health policy.

# Methods

A systematic search of MEDLINE, EMBASE, Global Health and African Journals Online identified studies reporting the prevalence of COPD in Nigeria. We provided a detailed synthesis of study characteristics, and overall median and interquartile range (IQR) of COPD prevalence in Nigeria by case definitions (spirometry or non-spirometry).

# Results

Of 187 potential studies, eight studies (6 spirometry and 2 non-spirometry) including 4,234 Nigerians met the criteria. From spirometry assessment, which is relatively internally consistent, the median prevalence of COPD in Nigeria was 9.2% (interquartile range, IQR: 7.6–10.0), compared to a lower prevalence (5.1%, IQR: 2.2–15.4) from studies based on British Medical Research Council (BMRC) criteria or doctor’s diagnosis. The median prevalence of COPD was almost the same among rural (9.5%, IQR: 7.6–10.3) and urban dwellers (9.0%, IQR: 5.3–9.3) from spirometry studies.

# Conclusions

A limited number of studies on COPD introduces imprecision in prevalence estimates and presents concerns on the level of response available across different parts of Nigeria, and indeed across many countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

Keywords: epidemiology, prevalence, COPD, chronic respiratory disease, Nigeria

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive, potentially life-threatening lung disease that affects over 380 million adults worldwide with an estimated global economic cost of over $2 trillion.1–3 In 2015, COPD accounted for 3.2 million deaths, representing 5% of all global deaths, with more than 90% occurring in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).1,4

In Nigeria and across many countries in sub-Saharan Africa, COPD is a major public health problem.5–7 The prevalence of tobacco smoking, a major risk for COPD, is increasing in many settings, particularly among the younger population groups.8 Outdoor air pollution continues to worsen, particularly in growing urban settings, contributing further to increased risk.4 Further, second-hand smoke and indoor smoke from the use of unclean cooking and heating fuels are major risks among women and children in many rural settings.9 Low income, poor nutrition, childhood respiratory infections, tuberculosis, and HIV infection, are additional COPD risks that have been reported in many African settings, including Nigeria.10 Yet, facilities and strategies for prevention, early diagnosis, treatment and overall management of COPD have been relatively limited and are currently suboptimal.11,12 Additionally, the awareness of COPD is poor, hence government and policymakers don’t consider COPD a health priority.5,11,13,14 Consequently, diagnosis is often missed and treatments are not guideline-based.5,11,14,15

Priority setting and policy making rely on perceived disease burden, and evidence of COPD burden in many parts of Africa is largely lacking.10,12 A relative lack of standard diagnostic facilities and the required expertise to perform spirometry are among the key factors.3,6,16 In Nigeria, available data on COPD burden have been based on varying survey protocols and case definitions.13 Consequently, there is not yet a comprehensive epidemiologic description of the COPD burden in the country. To fill this knowledge gap, we systematically searched for available evidence on COPD in Nigeria and provided a detailed synthesis of COPD prevalence in the country to further raise awareness of the burden.

METHODS

The study was conducted and reported according to the PRISMA guidelines.17

Search strategy

Epidemiologic studies of COPD in Nigeria were identified in MEDLINE, EMBASE, Global Health (CABI), and Africa Journals Online (AJOL) using a combination of search terms (Table 1). Searches were first conducted on 01 December 2021 with this updated on 04 July 2022 and limited to studies published after 1 January 1990. Unpublished documents were sourced from Google Scholar and Google searches. Titles and abstracts of studies were reviewed, and full texts of relevant studies were accessed. The reference lists of accessed full texts were further hand-searched for additional studies. When necessary, we contacted the authors of selected papers for any missing information.

TABLE 1.

Search terms on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in Nigeria.

| # | Searches |

|---|---|

| 1 | exp Nigeria/ |

| 2 | exp vital statistics/ |

| 3 | (incidence* or prevalence* or morbidity or mortality).tw. |

| 4 | (disease adj3 burden).tw. |

| 5 | exp “cost of illness”/ |

| 6 | case fatality rate.tw |

| 7 | hospital admissions.tw |

| 8 | Disability adjusted life years.mp. |

| 9 | (initial adj2 burden).tw. |

| 10 | exp risk factors/ |

| 11 | 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 |

| 12 | exp chronic obstructive lung disease / or copd / or chronic obstructive airway disease / or chronic bronchitis /or emphysema |

| 13 | 1 and 11 and 12 |

| 14 | Limit 13 to “1990-current” |

Selection criteria

We sought population-based studies reporting on the prevalence of COPD in a Nigerian setting. As there were very few population-based studies from our initial searches, we also searched for hospital-based studies on the prevalence of COPD and only selected such studies if they were conducted among out-patients and provided enough data on the catchment population of the hospital on which the prevalence estimate was based. We excluded other hospital-based or clinical reports, studies on Nigerians in the diaspora, reviews, viewpoints, and commentaries.

Case definitions

There are existing limitations in the case definition and diagnosis of COPD across Africa and many LMICs.1,4 Hence, to have a broad view of current research efforts, we included all studies based on COPD irrespective of the case definitions employed and presented results based on individual case definitions. First, we included studies that were based on spirometry, as these are largely consistent with the diagnosis of COPD worldwide.18,19 We employed the Global Initiative on Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) recommended a fixed ratio of forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) to forced vital capacity (FVC) that is less than 0.7 (FEV1/FVC<0.7).18 We also considered studies with the ratio (FEV1/FVC) less than the lower limit of normal (LLN), which is calculated by subtracting the standard deviation (multiplied by 1.64) from the mean.18 This is because respiratory physicians have argued that using a fixed ratio may potentially result in underdiagnoses in younger patients and more frequent diagnoses in the elderly, as lung elasticity decreases with age.2,4 Second, we included studies based on the British Medical Research Council (BMRC) questionnaire for chronic bronchitis in which there is an affirmative response to the definition “daily productive cough for at least three consecutive months for more than two successive years”.20 Third, we considered any studies based on a previous COPD diagnosis by a physician. We sorted our data and analysis based on these criteria – spirometry and non-spirometry (BMRC and doctor’s diagnosis).

Data extraction

Eligible studies were independently assessed by two reviewers (BMA and YL). An eligibility guideline was applied to ensure consistency in selection. The disagreement was resolved in another meeting with the DA. From selected studies, data on the location, study period, study design, study setting (urban, rural, or mixed), sample size, diagnostic criteria and mean age of the population were extracted, and matched with corresponding data on COPD cases, sample population, the prevalence of COPD in the study.

Quality assessment

From each full text, study design and methodology, case definitions, and the generalizability of the reported estimates to a larger population within the Nigerian geo-political zone were further checked, by adapting a previously used quality guideline for studies on the burden of chronic diseases.21–24 We checked for sampling approach (was it representative of a target subnational population?), statistical methods (was it appropriate for the study outcome?), and case ascertainment (was it based on spirometry, BMRC criteria, informal interviews, or not reported?). Studies were graded as high (4–5), moderate (2–3), or low quality (0–1) (see Tables 2 and 3, and online supplementary document for details of all full-text manuscripts accessed and quality grading).

TABLE 2.

Quality assessment of selected studies.

| Quality criteria | Assessment | Score | Maximum score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling method (was it representative of a target subnational population?) | Yes | 1 | 1 |

| No | 0 | ||

| Appropriateness of statistical analysis | Yes | 1 | 1 |

| No | 0 | ||

| Case ascertainment (was it based on spirometry, BMRC criteria, informal interviews, or not reported?) | Spirometry | 3 | 3 |

| BMRC or doctor’s diagnosis | 2 | ||

| Informal interviews | 1 | ||

| Not-reported | 0 | ||

| Total (high (4–5), moderate (2–3), or low quality (0–1)) | 5 | ||

TABLE 3.

Characteristics of studies on prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in Nigeria.

| Author | Study period | Location | Geopolitical zone | Study design | Case definition | Study Setting | Age range (mean) | Sample | Overall prevalence, CI (%) | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adeniyi et al.25 | 2012 | Owo, Ondo State | South-west | Hospital based retrospective study | FEV1/FVC < 0.7 | Semi-urban/ Rural | 25+ (50.0) | 914 | 7.6 | Moderate |

| Obaseki et al.26 | 2012 | Ile-Ife, Osun State | South-west | Population-based cross-sectional study | FEV1/FVC < LLN | Semi-urban/ Rural | 40+ (53.3) | 875 | 7.7 | High |

| Desalu et al.27 | 2009 | Ido-Ekiti, Ekiti State | South-west | Population-based cross-sectional study | BMRC criteria or doctor’s diagnosis | Semi-urban/ Rural | 35+ (55.5) | 391 | 5.6 | Moderate |

| Desalu et al.28 | 2004–2010 | Ido-Ekiti, Ekiti State | South-west | Hospital based retrospective study | FEV1/FVC < 0.7 | Semi-urban/ Rural | 18+ (49.9) | 368 | 10.3 | Moderate |

| Harris-Eze29 | 1992 | Ibadan, Oyo State | South-west | Population-based cross-sectional study | BMRC criteria or doctor’s diagnosis | Urban | 18+ (35.8) | 804 | 2.2 | Moderate |

| Douglas & Katchy31 | 2016 | Port-Harcourt, Rivers State | South-south | Population-based cross-sectional study | FEV1/FVC < 0.7 | Urban | 40+ (52.0) | 200 | 9.0 | High |

| Ozoh et al.30 | 2012 | Idi-Araba, Lagos | South-west | Population-based cross-sectional study | FEV1/FVC < 0.7 | Urban | 40+ (53.7) | 412 | 5.3 | High |

| Gathuru et al.32 | 1999 | Benin, Edo State | South-south | Population-based cross-sectional study | FEV1/FVC<0.7 | Urban | 30–69 (47.0) | 270 | 9.3 | High |

Data analysis

We provided a narrative synthesis of study characteristics and individual estimates of COPD prevalence from each study. Due to limited data and observed high heterogeneity in a preliminary analysis, we found pooling by meta-analysis inappropriate for this study (see online supplementary document for details). Rather, we estimated each study’s median and interquartile range (IQR) separately by case definitions (spirometry or non-spirometry). We have applied this approach in a previous study on COPD prevalence in Africa12. All statistical analyses were conducted on Stata (Stata Corp V.14, Texas, USA).

RESULTS

Search results

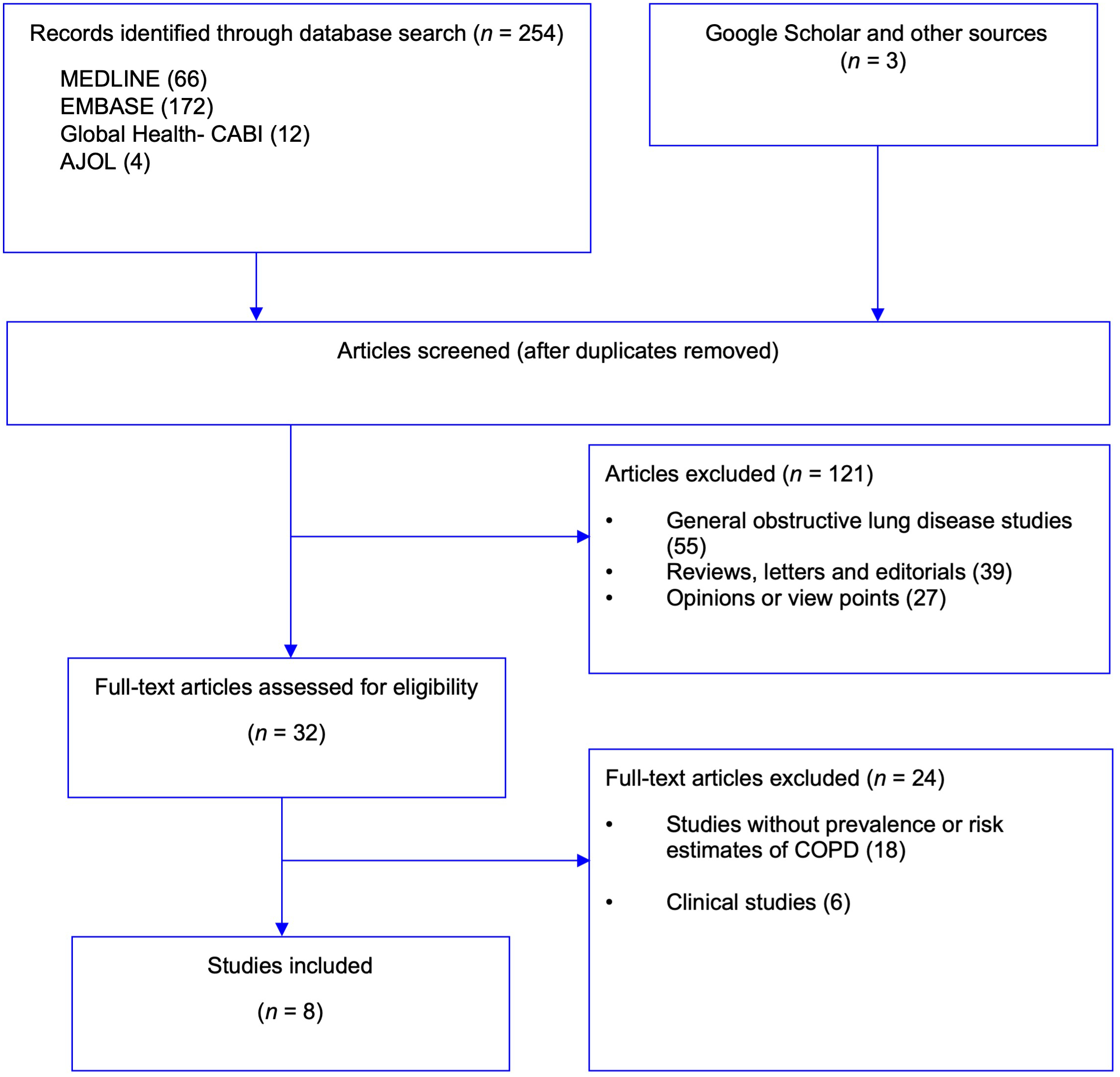

The search of the databases returned 184 studies (MEDLINE 66, EMBASE 102, Global Health 12, and AJOL 4) and 3 additional studies were identified through Google Scholar and hand-searching reference lists of relevant studies. After removing duplicates, applying the aforementioned selection criteria, and full-text examinations, a total of 8 studies25–32 were included (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of selection of studies on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in Nigeria.

Study characteristics

The 8 studies yielded 17 data points. There were 15 data points from the South-west and 2 from the South-south of Nigeria. There were no studies from the northern region. Rural dwellers had 13 data points, while urban had four (Table 3). Six studies were based on a spirometry-defined epidemiologic assessment and two on non-spirometry definitions (BMRC criteria or doctor’s diagnosis). Only one of the spirometry-based studies was based on LLN.26 Two studies were based on a review of out-patient cases matched to an estimated catchment population25,28. The study period ranged from 1992 to 2016, with most studies conducted within one year. The total sample population from all studies was 4,234, with a mean age ranging from 35.8 to 55.0 years (Table 3). Four studies were rated high quality and four moderate (Table 3, Online supplementary document).

Prevalence of COPD in Nigeria

The lowest COPD prevalence was reported in a study of soldiers in Ibadan, Oyo State, South-west Nigeria, with an estimated prevalence of 2.2% using the BMRC criteria29. The highest prevalence of COPD was reported among factory workers in the oil-producing city of Port Harcourt, Rivers State, South-south Nigeria at 9.0%. Another high prevalence was estimated in the peri-rural setting of Ile-Ife, Osun State, South-west Nigeria at 7.7%26. The distribution of the crude prevalence rates from individual studies appears to be rising with increasing age and study years. For example, the Ibadan study29 was conducted in 1992 with a mean age of 35.8 years, while the Port Harcourt study31 had a mean age of 52 years and was conducted in 2016.

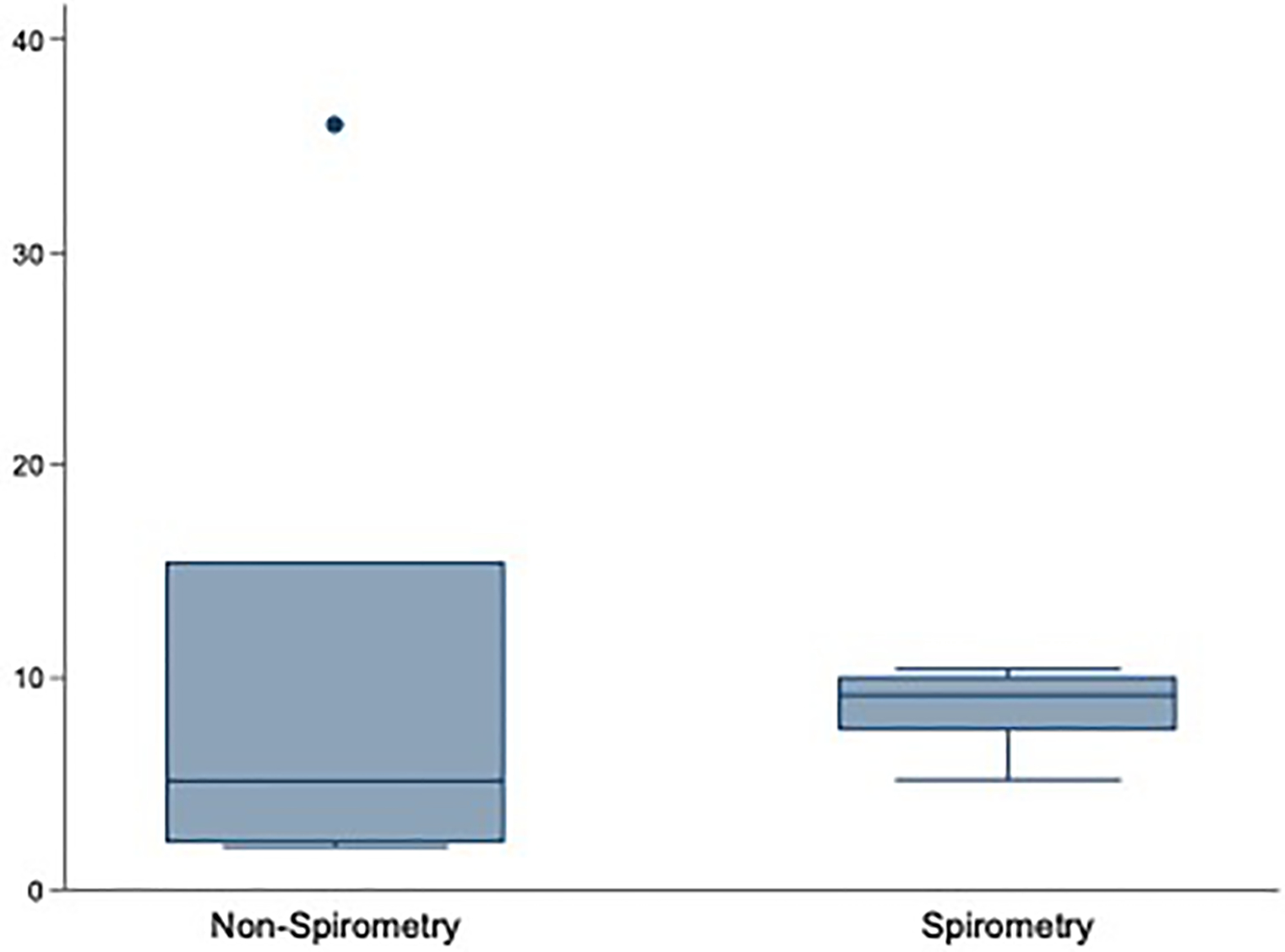

From studies based on spirometry, the median prevalence of COPD in Nigeria was 9.2% (interquartile range, IQR=7.6–10.0) (Table 4). As observed in Figure 2, the median prevalence was lower with wide IQR from studies based on BMRC criteria or doctor’s diagnosis (5.1%, IQR=2.2–15.4). The wide IQR may further underpin the uncertainties from studies based on BMRC criteria or doctor’s diagnosis, with higher heterogeneity (I2=74.3%, P=0.001) observed in a preliminary analysis, compared to a lower heterogeneity from spirometry studies (I2=45.6%, P=0.065).

Table 4.

Crude estimates of prevalence of COPD in Nigeria.

| Both sexes | Men | Women | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (IQR) % | Data points | Prevalence (IQR) % | Data points | Prevalence (IQR) % | Data points | |||

| Diagnostic criteria | Spirometry | 9.2 (7.6–10.0) | 10 | 8.6 (7.6–10.5) | 3 | 6.3 (3.8–6.7) | 3 | |

| BMRC or doctor’s diagnosis | 5.1 (2.2–15.4) | 7 | 6.7 | 1 | 5.1 | 1 | ||

| Settings | Spirometry | Rural | 9.5 (7.6–10.3) | 7 | - | - | - | - |

| Urban | 9.0 (5.3–9.3) | 3 | - | - | - | - | ||

| BMRC or doctor’s diagnosis | Rural | 5.4 (4.0–15.4) | 6 | - | - | - | - | |

| Urban | 2.2 | 1 | - | - | - | - | ||

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) prevalence in Nigeria by case definition.

Sex-specific estimates from spirometry assessment revealed a higher median prevalence among men at 8.6% (IQR=7.6–10.5) compared to women at 6.3% (IQR=3.8–6.7) (Table 4). Only one study27 reported sex-specific estimates for non-spirometry studies, at 6.7% among men and 5.1% in women.

In terms of residence, the median prevalence of COPD was slightly higher in rural settings (9.5%, IQR=7.6–10.3) compared to urban settings (9.0%, IQR=5.3–9.3) from spirometry studies (Table 4). Although generally lower in non-spirometry studies, the median prevalence was also higher in rural settings at 5.4% (IQR=4.0–15.4), compared to 2.2% reported in the only non-spirometry study conducted among urban dwellers29.

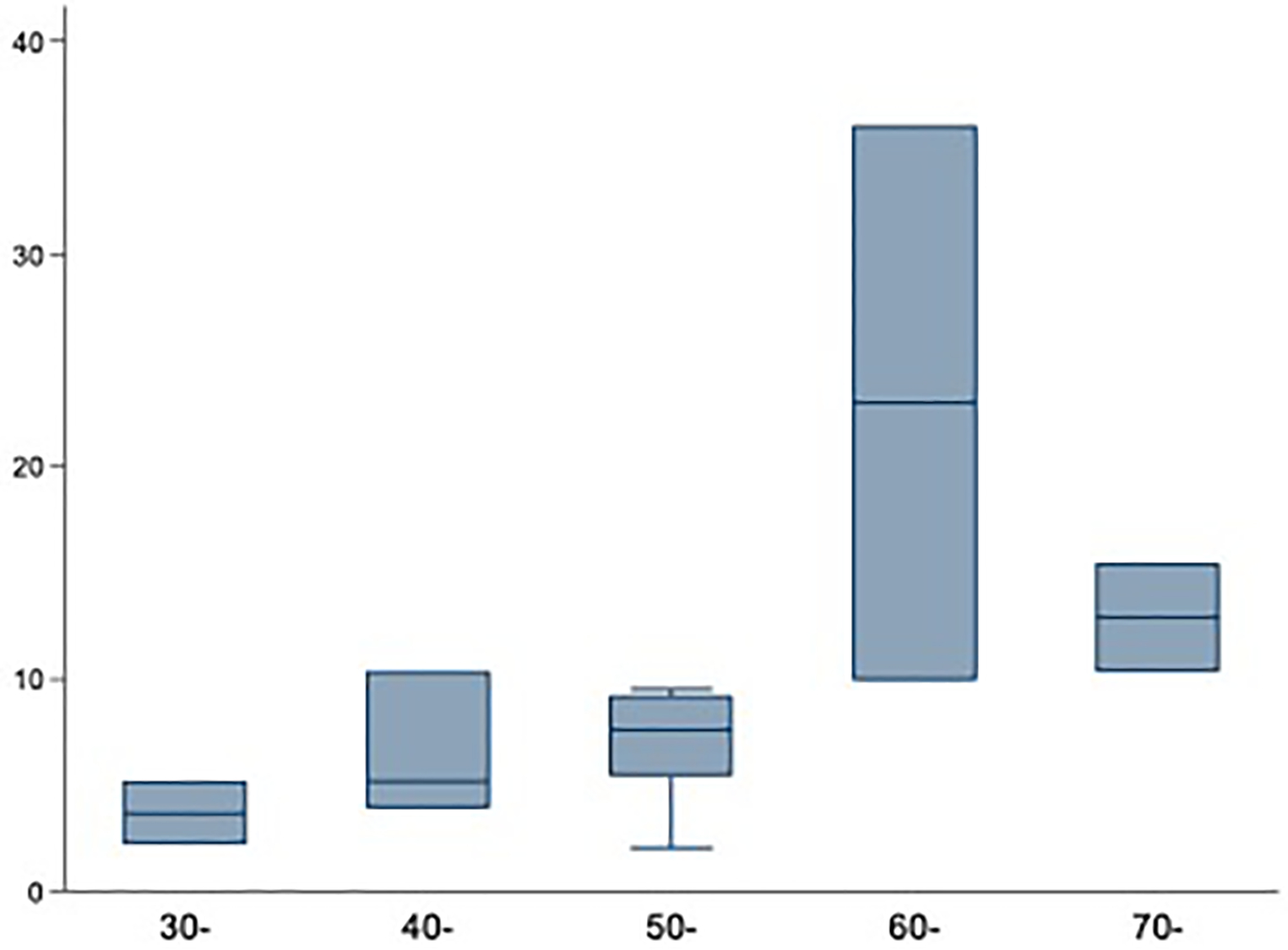

From all studies, the prevalence of COPD increased with the rising mean age of the sample population (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

The prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in Nigeria by age (in years).

COPD prevalence in the WHO African region

To compare estimates from other African settings with Nigeria, we ran additional literature searches for studies in the World Health Organization (WHO) African region. The highest spirometry-based prevalence of COPD at 23.8% was estimated in Cape Town, South Africa, in 200519. The lowest prevalence (2.3%) was reported in the Mbarara district, Uganda, in 201833 (Table 5).

Table 5.

Prevalence of spirometry-confirmed COPD in the WHO African region

| First Author | Study period | Country | Location | Setting | Protocol | Screening | Age | Sample | Cases | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buist19 | 2005 | South Africa | Cape Town | Urban | BOLD | FEV1/FVC<0.7 | 40+ | 847 | 202 | 23.8 |

| Fullerton40 | 2001 | Malawi | Southern Malawi | Mixed | ATS/ERS | FEV1/FVC<0.7 | 30+ | 332 | 45 | 13.6 |

| Khelafi41 | 2011 | Algeria | Algiers | Mixed | ATS/ERS | FEV1/FVC<0.7 | 21+ | 1800 | 87 | 4.9 |

| Magitta42 | 2018 | Tanzania | Simuyu | Rural | BOLD | FEV1/FVC<0.7 | 35+ | 496 | 87 | 17.5 |

| Musafiri43 | 2008– 2009 | Rwanda | Huye & Kigali | Mixed | Standard questionnaire | FEV1/FVC<LLN | 15+ | 1824 | 82 | 4.5 |

| Musafiri43 | 2008– 2009 | Rwanda | Huye & Kigali | Mixed | Standard questionnaire | FEV1/FVC<0.7 | 15+ | 1824 | 212 | 11.6 |

| North33 | 2015 | Uganda | Mbarara | Rural | Standard questionnaire | FEV1/FVC<0.7 | 18–93 | 565 | 13 | 2.3 |

| Pefura-Yone44 | 2013–2014 | Cameroon | Yaounde | Rural | ATS/ERS | FEV1/FVC<LLN | 19+ | 1276 | 31 | 2.4 |

| Van Gemert35 | 2012 | Uganda | Masindi | Rural | Standard questionnaire | FEV1/FVC<0.7 | 30+ | 588 | 95 | 16.2 |

DISCUSSION

Herein, we provide the first national estimates of the prevalence of COPD in Nigeria. With Nigeria being the most populous country in Africa, our findings are also relevant on the continent, and useful for relevant international comparisons.

Our review revealed that there is an absence of a nationally representative study on COPD prevalence across Nigeria, similar to observations in many African countries.6,10,12 There is a strong likelihood that our estimates are under-estimations due to the lack of data, varying case definitions, and underdiagnoses across several settings.10,34 However, based on available data, we noted higher and internally consistent estimates from studies based on spirometry (compared to non-spirometry), but still with very low levels of certainties in terms of national and sub-national representativeness. The prevalence of COPD we have estimated in Nigeria in this review is lower than reported in some other African settings. For example, a 2015 spirometry-based survey that followed standard survey protocols in Uganda revealed a higher estimate of COPD prevalence at 16.2%,35 which is similar to our previous estimate of 13.4% in Africa.12 The highest spirometry-based prevalence of COPD in Africa at 23.8% was estimated in Cape Town, South Africa, in 2005.19 Asides from the lack of data from many settings, there is no clear explanation for the lower comparative COPD prevalence in Nigeria, thus suggesting a need for a nationally representative study on prevalence, risk factors, economic burden and outcome.

As observed in this study, higher COPD prevalence among men is common in the literature.19,26,34 However, women are generally more susceptible to COPD exposures compared to men, presenting with a faster annual decline in FEV1 and a higher risk of hospital admissions and death from respiratory failure and related comorbidities.36,37 Women may also be more affected in rural settings where data and surveillance may be weaker or variable in population coverage completeness. In Nigeria and many African settings, rural dwellers are regularly exposed to smoke from firewood and other biomass fuels, as this is the main source of energy for cooking.5,12 In this study, the relatively similar prevalence of COPD among rural and urban dwellers (9.5% vs 9.0% from spirometry assessment) further underpins a rising burden in rural settings. Smoke from biomass fuel, in contrast to tobacco smoking, is an important and highly prevalent risk for COPD among women in rural Africa where over 90% of the population employ this for domestic cooking, and are exposed at an average of 3–5 hours daily in poorly ventilated kitchens.35

Existing programs for the prevention, care and management of COPD in Nigeria are mostly poorly developed,5,38 reflective of Africa more broadly. In a survey of 106 physicians in 34 countries, Mehrotra and colleagues39 reported that only 23 physicians satisfactorily used spirometry to diagnose COPD, and effective treatment is largely unavailable or unaffordable for diagnosed cases. There is a strong need for strategies to improve population-wide awareness and provision of facilities for the diagnosis and treatment of COPD.6,8 These programs are likely to be most effective if adequate capacity is developed at the primary care levels of health delivery which is likely the first point of contact for most patients in urban and rural settings.3

The main limitation of this study is the narrow national representation of the available data. For example, there were no studies from the northern regions, and we also extracted data from some hospital-based studies for better insight into the burden of COPD at facility levels. We also had challenges from varying prevalence rates, a wide range of populations, inconsistent diagnostic criteria, and inconsistent study designs and quality.6,39

CONCLUSIONS

Studies on the prevalence of COPD in Nigeria are still mainly from the southern parts of the country, and many of these are not based on spirometry. This presents huge uncertainties on the current level of evidence. Furthermore, it presents concerns on the level of response available across different parts of the country, and indeed across many countries in Africa, for a disease currently rated the third leading cause of death globally. This study has provided some insights on the burden of COPD in Nigeria, relevant for policies, programming, and future research in the country and Africa.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors acknowledge the support of the Nigeria Federal Ministry of Health and the WHO Nigeria Country Office in the conduct of this study.

Funding:

MOH was supported by NIH/NHLBI K99 HL141678.

Footnotes

Competing interests: DA is a Co-Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Global Health Reports. To ensure that any possible conflict of interest relevant to the journal has been addressed, this article was reviewed according to best practice guidelines of international editorial organisations. The authors completed the ICMJE Unified Competing Interests Form (available upon request) and declare no further conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Soriano JB, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, et al. Global, regional, and national deaths, prevalence, disability-adjusted life years, and years lived with disability for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 2017;5(9):691–706. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30293-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adeloye D, Chua S, Lee C, et al. Global and regional estimates of COPD prevalence: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of global health. Dec 2015;5(2):020415. doi: 10.7189/jogh.05-020415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salvi S The silent epidemic of COPD in Africa. The Lancet Global Health. 2015;3(1):e6–e7. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70359-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). World Health Organization. Accessed 03 December 2018, http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-(copd) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desalu OO, Onyedum CC, Adeoti AO, et al. Guideline-based COPD management in a resource-limited setting - physicians’ understanding, adherence and barriers: a cross-sectional survey of internal and family medicine hospital-based physicians in Nigeria. Primary care respiratory journal : journal of the General Practice Airways Group. Mar 2013;22(1):79–85. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2013.00014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finney LJ, Feary JR, Leonardi-Bee J, Gordon SB, Mortimer K. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. May 2013;17(5):583–9. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adeloye D, Song P, Zhu Y, Campbell H, Sheikh A, Rudan I. Global, regional, and national prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in 2019: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Respir Med. May 2022;10(5):447–458. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(21)00511-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stanciole AE, Ortegón M, Chisholm D, Lauer JA. Cost effectiveness of strategies to combat chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma in sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia: mathematical modelling study. 10.1136/bmj.e608. BMJ. 2012;344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sylla FK, Faye A, Fall M, Anta T-D. Air Pollution Related to Traffic and Chronic Respiratory Diseases (Asthma and COPD) in Africa. Health. 2017;9(10):1378. [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Gemert F, van der Molen T, Jones R, Chavannes N. The impact of asthma and COPD in sub-Saharan Africa. Clinical Reviews. Primary Care Respiratory Journal. 04/20/online 2011;20:240. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2011.00027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ozoh OB, Eze JN, Garba BI, et al. Nationwide survey of the availability and affordability of asthma and COPD medicines in Nigeria. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2021;26(1):54–65. doi: 10.1111/tmi.13497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adeloye D, Basquill C, Papana A, Chan KY, Rudan I, Campbell H. An estimate of the prevalence of COPD in Africa: a systematic analysis. COPD: Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2015;12(1):71–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Obaseki DO, Erhabor GE, Awopeju OF, Obaseki JE, Adewole OO. Determinants of health related quality of life in a sample of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Nigeria using the St. George’s respiratory questionnaire. African health sciences. Sep 2013;13(3):694–702. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v13i3.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozoh OB, Awokola BI, Buist SA. A survey of the knowledge of general practitioners, family physicians and pulmonologists in Nigeria regarding the diagnosis and treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. West Afr J Med. Apr-Jun 2014;33(2):100–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erhabor GE, Kolawole OA. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a ten-year review of clinical features in O.A.U.T.H.C., Ile-Ife. Nigerian journal of medicine : journal of the National Association of Resident Doctors of Nigeria. Jul–Sep 2002;11(3):101–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plum C, Stolbrink M, Zurba L, Bissell K, Ozoh BO, Mortimer K. Availability of diagnostic services and essential medicines for non-communicable respiratory diseases in African countries. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. Feb 1 2021;25(2):120–125. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.20.0762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS medicine. Jul 21 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, et al. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2007/09/15 2007;176(6):532–555. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-456SO [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buist AS, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM, et al. International variation in the prevalence of COPD (the BOLD Study): a population-based prevalence study. Lancet (London, England). Sep 1 2007;370(9589):741–50. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(07)61377-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Definition and classification of chronic bronchitis for clinical and epidemiological purposes. A report to the Medical Research Council by their Committee on the Aetiology of Chronic Bronchitis. Lancet (London, England). Apr 10 1965;1(7389):775–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stanifer JW, Jing B, Tolan S, et al. The epidemiology of chronic kidney disease in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Global Health. 2014;2(3):e174–e181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pai M, McCulloch M, Gorman JD, et al. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses: an illustrated, step-by-step guide. Natl Med J India. 2004;17:86–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guyatt GH, Rennie D. Users’ guides to the medical literature: a manual for evidence-based clinical practice AMA Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Juni P, Altman DG, Egger M. Systematic reviews in health care: assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ. 2001;323:42–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adeniyi B, Awokola B, Irabor I, et al. Pattern of Respiratory Disease Admissions among Adults at Federal Medical Centre, Owo, South-West, Nigeria: A 5-Year Review. Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research. 2017; [Google Scholar]

- 26.Obaseki D, Erhabor G, Burney P, Buist S, Awopeju O, Gnatiuc L. The prevalence of COPD in an African city: Results of the BOLD study, Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Eur Respiratory Soc; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Desalu OO. Prevalence of chronic bronchitis and tobacco smoking in some rural communities in Ekiti state, Nigeria. The Nigerian postgraduate medical journal. Jun 2011;18(2):91–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Desalu OO, Ojo OO, Busari OA, Fadeyi A. Pattern of respiratory diseases seen among adults in an emergency room in a resource-poor nation health facility. The Pan African medical journal. 2011;9:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harris-Eze AO. Smoking habits and chronic bronchitis in Nigerian soldiers. East African medical journal. Dec 1993;70(12):763–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ozoh O, Balogun B, Oguntunde O, et al. The prevalence and determinants of COPD in an urban community in Lagos, Nigeria. Eur Respiratory Soc; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Douglas KE, Katchy I. Comparative study of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease among production and administration cement factory workers in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Gazette of Medicine. 2016;5(1):453–75. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gathuru IM, Bunker CH, Ukoli FA, Egbagbe EE. Differences in rates of obstructive lung disease between Africans and African Americans. Ethnicity and Disease. Autumn 2002;12(4):S3–107-S3–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.North CM, Kakuhikire B, Vorechovska D, et al. Prevalence and correlates of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic respiratory symptoms in rural southwestern Uganda: a cross-sectional, population-based study. Journal of Global Health. 2019;9(1):010434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Obaseki DO, Erhabor GE, Gnatiuc L, Adewole OO, Buist SA, Burney PG. Chronic Airflow Obstruction in a Black African Population: Results of BOLD Study, Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Copd. 2016;13(1):42–9. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2015.1041102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Gemert F, Kirenga B, Chavannes N, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and associated risk factors in Uganda (FRESH AIR Uganda): a prospective cross-sectional observational study. The Lancet Global Health. 2015;3(1):e44–e51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gan WQ, Man SF, Postma DS, Camp P, Sin DD. Female smokers beyond the perimenopausal period are at increased risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respiratory research. Mar 29 2006;7:52. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barnes PJ. Sex Differences in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Mechanisms. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2016;193(8):813–814. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201512-2379ED [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Magitta NwF. Epidemiology and Challenges of Managing COPD in sub-Saharan Africa. Acta Scientific Medical Sciences. 2018;2(1):17–23. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mehrotra A, Oluwole AM, Gordon SB. The burden of COPD in Africa: a literature review and prospective survey of the availability of spirometry for COPD diagnosis in Africa. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2009/08/01 2009;14(8):840–848. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02308.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fullerton DG, Suseno A, Semple S, et al. Wood smoke exposure, poverty and impaired lung function in Malawian adults. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. Mar 2011;15(3):391–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khelafi R, Aissanou A, Tarsift S, Skander F. [Epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Algiers]. Rev Mal Respir. Jan 2011;28(1):32–40. Epidemiologie de la bronchopneumopathie chronique obstructive dans la wilaya d’Alger. doi: 10.1016/j.rmr.2010.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Magitta NF, Walker RW, Apte KK, et al. Prevalence, risk factors and clinical correlates of COPD in a rural setting in Tanzania. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t. European Respiratory Journal. 2018;51(2):02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Musafiri S, van Meerbeeck J, Musango L, et al. Prevalence of atopy, asthma and COPD in an urban and a rural area of an African country. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t. Respiratory Medicine. 2011;105(11):1596–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pefura-Yone EW, Kengne AP, Balkissou AD, et al. Prevalence of obstructive lung disease in an African country using definitions from different international guidelines: a community based cross-sectional survey. BMC Research Notes. 2016;9:124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.