Abstract

Deinococcus radiodurans is a highly radiation-resistant bacterium that is classed in a major subbranch of the bacterial domain. Since very little is known about gene expression in this bacterium, an initial study of promoters was undertaken. In order to isolate promoters and study promoter function, a series of integrative vectors for stable chromosomal insertion in D. radiodurans were developed. These vectors are based on Escherichia coli replicons that are unable to replicate autonomously in D. radiodurans and carry homologous sequences for replacement recombination in the D. radiodurans chromosome. The resulting integration vectors were used to study expression of reporter genes fused to a number of putative promoters that were amplified from the D. radiodurans R1 genome. Further analysis of these and other putative promoters was performed by Northern hybridization and primer extension experiments. In contrast to previous reports, the −10 and −35 regions of these promoters resembled the ς70 consensus sequence of E. coli.

Its extraordinary tolerance to extremely high doses of ionizing radiation has made Deinococcus radiodurans the focus of growing scientific interest. This non-spore-forming bacterium is able to survive up to 4,000 times the lethal radiation dose for humans without mutation or loss of viability (2, 9). D. radiodurans is also of interest as a representative of a deeply branching family within the domain Bacteria (10). The sequence of the D. radiodurans R1 genome was recently published and shown to consist of two chromosomes, a megaplasmid, and one plasmid (17).

Despite the interest in D. radiodurans, little is known concerning basic gene expression and promoters. Earlier studies showed that Deinococcus promoter regions are poorly recognized in Escherichia coli, and E. coli promoters that were tested were not recognized in D. radiodurans (7, 14), suggesting that deinococcal promoters might be different from the classical E. coli ς70 type. However, no transcriptional analysis of deinococcal promoters has been carried out. Analysis of the recently published genome sequence revealed only three putative sigma factors, one classing with vegetative ς70 (rpoD) sequences, and two classing with extracytoplasmic alternative transcription factors (annotated as rpoE and DR0804 [17]). Surprisingly, orthologs of the nitrogen-starvation, general starvation, and heat shock sigma factors (rpoN, rpoS, and rpoH, respectively) were not found.

One reason for the lack of information on promoters in deinococci is the lack of convenient genetic tools for studying promoters. A promoter cloning vector has been described (7), but it involves an antibiotic resistance reporter and is a large plasmid with limited cloning sites. Therefore, we developed a suite of integrative promoter-screening vectors that allow the screening and assessment of promoter regions in D. radiodurans based on lacZ and xylE as reporters. These vectors were used to isolate and analyze promoter regions, and promoter regions were further defined by transcriptional analysis. Surprisingly, the −10 and −35 sequences of these promoters are similar to the E. coli ς70 sequence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| JM109 | F′ traD36 laclq Δ(lacZ)M15 proA+B+/e14− (McrA−) Δ(lac-proAB) thi gyrA96 (Nalr) endA1 hsdR17(rk− mk+) relA1 supE44 recAl | Promega (18) |

| TOP10 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) Φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 deoR araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697. galU galK rpsL (Strr) endA l nupG | Invitrogen |

| GM48 | F−thr leu thi lacY galK galT ara fhuA tsx dam dcm supE44 | 11 |

| D. radiodurans R1 | Wild-type strain | 1 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR2.1 | Cloning vector for PCR-generated products; Apr Kmr | Invitrogen |

| pCR2.1-TOPO | Like pCR2.1; uses covalently linked topoisomerase I instead of DNA ligase | Invitrogen |

| pUC19 | General cloning vector for E. coli; Apr, 2.7 kb | 18 |

| pMTL23 | General cloning vector for E. coli; Apr, 2.5 kb | 3 |

| pAY/K1 | pUC19 carrying the D. radiodurans amyE gene disrupted by the pUC4K Kmr gene; Apr Kmr, 5.5 kb | This study |

| pAY/K2 | pAY/K1 from which two PstI sites were removed by partial digestion and T4 DNA polymerase treatment | This study |

| pROBe1 | pAY/K2 carrying the P. putida xylE gene; Apr Kmr, 6.4 kb | This study |

| pROBe4 | pAY/K2 carrying the E. coli lacZ gene as a PCR fragment derived from pMUTIN2mcs | This study; 7a |

| pAMYE4Z | pROBe4 carrying the 263-bp putative amyE promoter fragment amplified by PCR (primers amyE-190 and amyE82) | This study |

| pLEXA4Z | Like pAMYE4Z; 288-bp lexA promoter insert | This study |

| pGROES4Z | Like pAMYE4Z; 298-bp groESL promoter insert | This study |

| pPE1 | pCR2.1-TOPO carrying a 713-bp aceR promoter fragment | This study |

| pPEx | Like pPE1; carrying 3′-extended promoter fragments of amyE (pPE2), lexA (pPE4), and groESL (pPE10) | This study |

| pPE11, pPE12, pPE13 | pCR2.1-TOPO carrying the polA (479 bp), rpoBC (631 bp), and rpoD (446 bp) promoter fragments, respectively | This study |

Chemicals and enzymes.

All chemicals used were of analytical grade and, unless indicated otherwise, were obtained from Baker Chemical Co. (Phillipsburg, N.J.) or Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, N.J.). 5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) and O-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG) were from ISC Bioexpress (Kaysville, Utah) and Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.), respectively. Enzymes for molecular biology were purchased from Roche Molecular Biochemicals (Indianapolis, Ind.) and New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.) and used according to the supplier. Taq and Platinum Taq DNA polymerases were obtained from Gibco-BRL (Gaithersburg, Md.).

Media and growth conditions.

Luria-Bertani (LB) broth for growth of E. coli consisted of (per liter) 10 g of tryptone (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.), 5 g of yeast extract (Difco), and 10 g of NaCl (pH 7.4). TGY broth for D. radiodurans contained (per liter) 5 g of tryptone, 1 g of glucose, and 3 g of yeast extract (10). Solid media were prepared by addition of 1.5% agar (Difco) to either LB or TGY broth. Where necessary, media were supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics, all of which were obtained from Sigma. Ampicillin (Ap) was used at 50 μg/ml for E. coli. Tetracycline (Tc) was added to a final concentration of 2.5 μg/ml for D. radiodurans. Kanamycin (Km) was routinely used at 50 μg/ml for E. coli and 8 or 4 μg/ml for D. radiodurans grown on solid and liquid medium, respectively. Transformations of E. coli were performed either using commercially available cells (JM109 and TOP10 from Promega, Madison, Wis., and Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif., respectively) or by the CaCl2 method (13). D. radiodurans cells were transformed as described previously (7a).

DNA manipulations.

Miniscale plasmid DNA preparations of E. coli were obtained as described by Sambrook et al. (13). PCR products were purified using the Qiaquick PCR purification Kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, Calif.). Northern blot analyses were performed according to Sambrook et al. (13). PCR-generated probes were labeled for hybridization with [α-32P]-dCTP (800 Ci/mmol; NEN Life Science Products, Boston, Mass.) using the Random Primed DNA labeling kit (Roche). Primers for PCR amplification, sequencing, and transcription start site mapping purposes were of varying length and were obtained from Gibco-BRL (Frederick, Md.) (Table 2). Radioactive sequencing reactions for primer extension analyses (see below) were carried out using the T7 Sequenase kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.). Non-radioactive nucleotide sequencing was performed at the University of Washington's Department of Biochemistry DNA Sequencing Facility, using an ABI Prism 377 sequencer (PE Biosystems).

TABLE 2.

Overview of primers used for cloning, diagnostic PCR, and primer extension experiments

| Primer | Length (bp) | Sequencea | Chromosome or plasmid, positiona |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cloning and diagnostic PCR | |||

| amyE_fwd | 20 | CCCTGACATCCCGCCTCTGA | I, 1484016 |

| amyE_rev | 21 | TCACCGCAAAACGAACGCCGC | I, 1485526 (C) |

| amyE-190 | 17 | CACCAGAAGGCGACGAT | I, 1483885 |

| amyE82 | 17 | CGGTTGATGTAGGCGCA | I, 1484147 (C) |

| amyE229 | 18 | TTCTGGATGTAAGGCAGC | I, 1484304 (C) |

| groESL-540 | 18 | AATCACCGCGTACTCGTC | I, 617330 |

| groESL-236 | 17 | GGAAGCACGTATTGTCG | I, 617634 |

| groESL61 | 17 | GTCTTCTGCTCGGCTTC | I, 617931 (C) |

| lexA-241 | 17 | GAGCGCTACGCCTTCAT | II, 380033 (C) |

| lexA46 | 17 | GTGGCTTGCAGGATGGA | II, 379746 |

| polAfwd | 18 | CAGAAGGTCCAGAACGTG | I, 1732780 (C) |

| polA_PE | 18 | AGGGATCTGGGGAAGCGT | I, 1732302 |

| rpoBCfwd | 18 | GTCCTTGCGCATCGTCTG | I, 927583 (C) |

| rpoBC_PE | 18 | CTGCACTTCGGTCAGGTT | I, 926953 |

| rpoDfwd | 18 | CTCCCAAAAAGGCCCGTG | I, 929104 |

| rpoD_PE | 18 | GGTCCTGCACTTCGATGT | I, 929549 (C) |

| amyEDCOf | 18 | GAACAAGGACGTGGACTG | pAY/K2, 859 |

| amyEDCOr | 18 | CCACGTTGTATACGGCTT | pAY/K2, 2726 (C) |

| KmRDCO | 18 | ATCCTGGTATCGGTCTGC | pAY/K2, 1999 (C) |

| SCOfwd | 18 | GAACTGGATCTCAACAGC | pAY/K2, 3791 |

| SCOrev | 18 | AGGCACCTATCTCAGCGA | pAY/K2, 4496 (C) |

| Primer extension | |||

| aceR_PE | 18 | GCGTCAGAATCTCGGCAT | II, 300602 |

| aceR_PE30 | 30 | TACTCGGGCTTGATCGGCGCGTTGATGGTC | II, 300619 |

| amyE_PE | 18 | ATCTGGCCTTCAAAGCTG | I, 1484169 (C) |

| amyE_PE30 | 30 | ACCTGATAGATGATCTGGCCTTCAAAGCTG | I, 1484181 |

| lexA_PE3 | 18 | CTGATTGCCTGCTTGGTG | II, 379674 |

| lexA_PE30 | 30 | GTGATGCCCACTTCCTGCGCCACCTGCCCC | II, 379689 |

| polA_PE | 18 | AGGGATCTGGGGAAGCGT | I, 1732302 |

| polA_PE30 | 30 | GGGAGGATTCTACTCTGGACGTAATTGCCG | I, 1732328 |

| rpoBC_PE | 18 | CTGCACTTCGGTCAGGTT | I, 926953 |

| rpoBC_PE30 | 30 | GGTCAGGTTGGGGAGCGGAATCACTTCGGT | I, 926962 |

| rpoD_PE | 18 | GGTCCTGCACTTCGATGT | I, 929549 (C) |

| rpoD_PE30 | 30 | AGGTAGACCTGCATATCCTCGAAGGCGTCA | I, 929520 (C) |

I and II, chromosome I or II, respectively. (C), sequence is on noncoding strand.

Sequence comparisons and predictions.

Computational analyses of DNA and predicted amino acid sequences were performed using the using the following internet-based programs. Similarity searches were carried out using the Blast algorithms available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/. Amino acid sequences for these searches were retrieved from the Colibri (http://bioweb.pasteur.fr/GenoList/Colibri/) and SubtiList (http://bioweb.pasteur.fr/GenoList/SubtiList/) webservers, dedicated to the E. coli and Bacillus subtilis genome sequences, respectively. Multiple alignments were performed using ClustalW (http://www2.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw/). The presence of possible signal peptidase I cleavage sites was analyzed using the parameters at http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/; analysis of primary protein structure was performed using the ExPASy ProtParam tool available at http://www.expasy.ch/cgi-bin/protparam. Preliminary sequence data for D. radiodurans were obtained from the Institute for Genomic Research website at http://www.tigr.org.

Plasmid constructions.

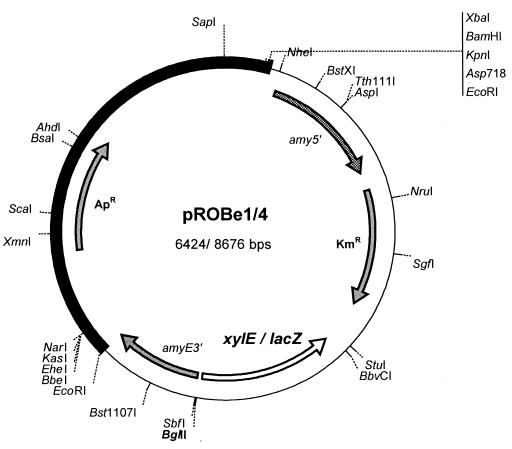

The pAY/K and pROBe series of promoter probe vectors were constructed as follows. First, a PCR fragment carrying the putative D. radiodurans R1 α-amylase (1,4-α-d-glucan glucanohydrolase) gene (amyE) was cloned in pCR2.1 (Invitrogen). The amyE gene was subsequently transferred to the EcoRI site of pUC19 and disrupted by insertion of the pUC4K Km marker in the HincII site, yielding pAY/K1. After partial PstI and T4 DNA polymerase treatment, pAY/K1.1 through −1.3 were obtained, each lacking one of the three PstI sites of pAY/K1. By fusing pAY/K1.2 and pAY/K1.3, plasmid pAY/K2 was constructed, carrying a unique PstI site between the amyE segments. This site was subsequently used for the insertion of PCR fragments carrying either the Pseudomonas putida xylE, E. coli lacZ, or Aequorea victoria gfp gene flanked by PstI and NsiI sites, yielding pROBe1, pROBe4, and pROBe5, respectively. All these vectors contain a unique BglII site that was used for the introduction of D. radiodurans R1-derived promoter fragments that were amplified by PCR and cloned into pCR2.1 or pCR2.1-TOPO. A second series of vectors were constructed by deletion of an NheI-XbaI fragment from pROBe1 carrying the amyE (pAMYE1), lexA (pLEXA1), and groESL (pGROES1) promoter fragments and subsequent cloning of a pMTL23-derived multiple cloning site in a unique XmaIII site located behind these promoter fragments. In a final step, the E. coli lacZ gene was inserted in the BglII and SpeI sites of these vectors, generating plasmids pAMYE4Z, etc.

Detection of α-amylase activity.

Kmr D. radiodurans R1 transformants were streaked on TY agar (TGY from which glucose was omitted), supplemented with 1% (wt/vol) soluble potato starch (Sigma, S-2004). After growth at 30°C for 2 days, plates were placed at room temperature for an additional 5 days. Haloes around α-amylase-producing colonies were visualized using an iodine solution consisting of 0.6% (wt/vol) KI and 0.3% (wt/vol) I2.

β-Galactosidase assays.

Expression of the lacZ reporter gene in E. coli and D. radiodurans colonies was detected using X-Gal (40 μg/ml). Quantitative analyses of lacZ expression were performed according to Miller et al. (8). Cell extracts of D. radiodurans were obtained by passing concentrated cell suspensions through a French press at 1,000 lb/in2 using a J5-598A laboratory pressure cell press (Aminco, Silver Spring, Md.). To prevent degradation of the reporter protein in cell extracts, a protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete Mini; Roche) was used. Alternatively, β-galactosidase activity was measured in toluene-permeabilized cells as follows. Cells were harvested by centrifuging 1-ml culture samples at 16,000 × g for 2 min. The pellets were subsequently resuspended in 500 μl of Z-buffer (8) supplemented with lysozyme (25 μg/ml) and DNase I (50 ng/ml). After incubation for 30 min at 37°C, 20 μl of toluene was added. The suspensions were incubated for another 60 min at 37°C, and aliquots (20 to 200 μl) were taken to measure β-galactosidase activity.

Northern hybridizations.

Total RNA was isolated from a maximum of 5 optical density at 600 nm (OD600) units of exponentially growing cells using the RNA Perfect kit (Eppendorf-5 Prime Inc., Boulder, Colo.). The isolates were subsequently treated with RNase I-free DNase I (Gibco-BRL) to remove residual contaminating chromosomal DNA. RNA samples (±8 μg) and molecular size RNA markers (0.24 to 9.5 kb; Gibco-BRL) were electrophoresed on MOPS (morpholine propane sulfonic acid)-formaldehyde-agarose slab gels at 6 to 7 V/cm. Subsequently, RNA was either stained in ethidium bromide (1 μg/ml) for 20 min and destained overnight in diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated H2O or transferred to positively charged Hybond-N+ membranes (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and probed with 32P-labeled PCR fragments, according to Sambrook et al. (13).

Transcription start site mapping.

Transcription start sites were mapped by means of primer extension according to the ThermoScript cDNA synthesis protocol, using 10 μg of total RNA. Primers were labeled with [γ32P]-ATP (6,000 Ci/mmol; NEN) using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Roche). In each case, primers for the reverse transcription reactions were 18- and 30-mers and were located at different positions relative to the start codon.

RESULTS

Construction and characterization of an integration vector.

In order to develop a system for analyzing promoters in D. radiodurans at the same copy number as the chromosome, a chromosomal integration vector was developed based on recombination replacement within a nonessential gene. A gene predicted to encode α-amylase was chosen as the target insertion site, as similar systems have proven successful in other bacteria (4, 6). Insertions in this gene, encoding the 1,4-α-d-glucan glucanohydrolase enzyme, provide a screenable phenotype, the formation of turbid haloes around amylase-producing colonies on starch-containing agar plates. Analysis of the D. radiodurans R1 partial genome sequence indicated that a 1,452-bp open reading frame (ORF) (DR1472) located on chromosome I was a likely candidate for an α-amylase ortholog, with identities to the E. coli malS and B. subtilis amyE genes. The predicted protein contains a possible signal peptidase cleavage site (17AQA↓AP21), suggesting that it may be translocated across the bacterial membrane. The corresponding ORF was amplified by PCR and cloned in pCR2.1. The pAY/K (general insertion vectors) and pROBe (insertion vectors containing reporter genes; Fig. 1) series of plasmids were subsequently constructed as indicated in Materials and Methods. Transformation of CaCl2-competent D. radiodurans yielded Km colonies at low frequencies when the plasmids were propagated in E. coli JM109 (Table 3). Loss of function could be visualized by the absence of halos around colonies grown for several days on TY agar containing 1% (wt/vol) starch.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the integration vectors and their unique restriction sites. The checkered and solid gray bars represent the 5′ and 3′ portions of the D. radiodurans R1 amyE gene, respectively; the solid bar indicates the pUC19-derived vector moiety. Antibiotic resistance markers (Apr and Kmr) are represented as shaded arrows. Fragments to be fused to the reporter genes xylE and lacZ (open arrow) were inserted in the BglII site indicated in bold type. Also indicated are the EcoRI sites used in the generation of pAY/K1 (see text for details). The vectors that were used for the integration and analyses of the promoters described in the present studies were different in their orientation of the Px::lacZ fusion (see Materials and Methods).

TABLE 3.

Efficiencies of D. radiodurans R1 transformationa

| Plasmid | Strain | Transformation frequency (transformants/μg of DNA) | Ratio, GM48/JM109 |

|---|---|---|---|

| pAY/K2 | JM109 | 14 | 47.6 |

| GM48 | 667 | ||

| pROBe4 | JM109 | 1.6 | 751 |

| GM48 | 1,202 |

Transformation yields with DNA isolated from a dam dcm strain of E. coli (GM48) were compared to those obtained with DNA extracted from a methylation-proficient host (JM109).

Using the pAY/K-derived series of plasmids, the use of linearized DNA greatly enhanced the occurrence of replacement recombinants (double-crossover strains) as opposed to single-crossover recombinants. However, the use of nonmethylated donor DNA, DNA passed through a dam dcm E. coli strain (11), resulted in large increases in transformation efficiencies (Table 3). Hence, it seemed possible that restriction of methylated donor DNA caused by a methylation-specific endonuclease(s) might significantly affect transformability of D. radiodurans and that by inactivating these systems, an improved host for genetic engineering of D. radiodurans might be obtained. Although a candidate (DRB0143) with identity to the E. coli mcrBC operon was identified in the partial genome sequence (12), an insertion mutation generated in mcrB did not cause increased transformation frequencies. All transformations with these and subsequent integration vectors were carried out after passage through a dam dcm E. coli strain.

In order to obtain D. radiodurans fragments containing promoter activity, two approaches were used with these vectors: direct cloning of PCR products based on the genome sequence and a random screening approach.

Assessment of promoter activities from selected genes.

Analysis of the preliminary genome sequence generated a number of potentially interesting genes for promoter analysis. Three genes were chosen at this stage, amyE (since it was being used as an insertion site) and two that might be under stress control, groES (DRO606), and lexA (DRA0344) (5, 16). The latter two were chosen as candidates for future development of stress-induced expression systems. In D. radiodurans (as in most other bacteria), groES is located immediately upstream of groEL (DRO607) (17), and both are involved in heat shock response in other bacteria (5). Using the vectors described above, transcriptional fusions between putative promoter fragments and reporter genes present on pAY/K2 plasmids were constructed to assess the activity of these promoters. The fragment containing the groES regulatory region was chosen so as to include a possible ς32-like promoter sequence (15) located 157 bp upstream of the groES translational start site. For lexA and amyE, each promoter fragment tested included approximately 200 bp upstream of the predicted start codon. Two of the reporter genes tested (xylE and lacZ) were reliable for plate screening, but only lacZ gave detectable activity in in vitro assays. Therefore, lacZ was used as a reporter in experiments involving activity measurements.

When these promoter fragments were fused to lacZ, blue colonies of D. radiodurans were obtained on X-Gal plates and significant levels of β-galactosidase activity were detected in cell extracts of these D. radiodurans recombinants (Table 4). The lexA fragment showed relatively low activity, the amyE fragment had moderate activity, and the groES fragment showed high activity (Table 4). Similar levels were obtained with a more rapid procedure involving toluene-treated cells (see Materials and Methods). The double-crossover nature of these recombinants was verified by a series of diagnostic PCRs on chromosomal DNA isolated from these strains.

TABLE 4.

Assessment of promoter activities in D. radiodurans R1 strains containing double-crossover promoter fusion insertions using the E. coli lacZ reporter gene

| Strain | Relevant genotype | β-Galactosidase activity (nmol/min/mg of protein) |

|---|---|---|

| R1a | Wild type | 0 |

| RM11 | ΔamyE PamyE::lacZ | 47.5 |

| RM15 | ΔamyE PlexA::lacZ | 9.2 |

| RM16 | ΔamyE PgroES::lacZ | 115.1 |

| RM18 | ΔamyE lacZ (no promoter) | 0.9 |

D. radiodurans R1 wild-type culture was used as a zero reference in the β-galactosidase assay.

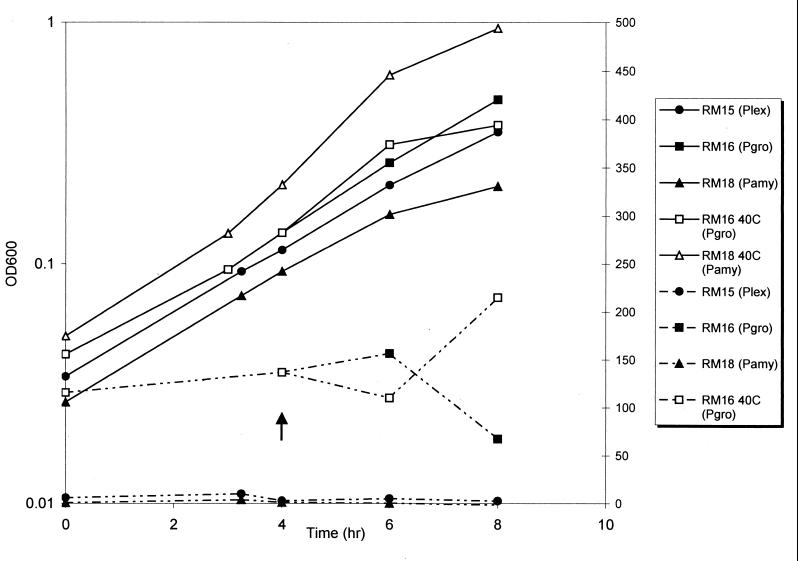

The groES promoter appeared to be expressed at a high, constitutive level at the normal growth temperature (30°C). In many bacteria, these genes are expressed at higher levels under heat shock conditions (5). In order to assess whether the cloned promoter region contained a heat shock regulatory element, we analyzed expression of the groES promoter under heat shock conditions. For D. radiodurans in TGY medium, the nonpermissive temperature is 42°C (7a), and so 40°C was chosen for the heat shock temperature. Four hours after a shift from 30 to 40°C, growth had leveled off, but a threefold increase in activity was observed compared to a culture with no temperature shift (Fig. 2). A similar difference was observed in cells grown overnight at 40°C compared to cells grown at 30°C.

FIG. 2.

Growth (solid lines) and β-galactosidase expression (dotted lines; nanomoles per minutes per OD600) of strains RM15 (ΔamyE PlexA::lacZ), RM16 (ΔamyE PgroESL::lacZ), and RM18 (ΔamyE::lacZ). The time point at which cultures were shifted to elevated temperatures is indicated by the arrow.

Random screening for promoter fragments.

In a separate series of experiments, a random Sau3A genomic library of D. radiodurans R1 was constructed in pROBe1 in order to isolate promoter-containing fragments from the genome. After establishment of recombinants in E. coli, clones were pooled, transferred to D. radiodurans R1, and screened for catechol 2,3-dioxygenase activity on plates. Pools generating transformants showing activity were separated into single clones which were tested again for activity in D. radiodurans R1. Several promoter-containing fragments were identified by this approach. A few showing the strongest activity were sequenced, and among these was a fragment derived from a gene that shows considerable similarity with the malate synthase A gene (aceB) of E. coli. By analogy, we designated the corresponding ORF aceR. The 5′ terminus of this gene is identical to an ORF (DRA0277) described by White et al. (17). This putative promoter fragment was included in further studies.

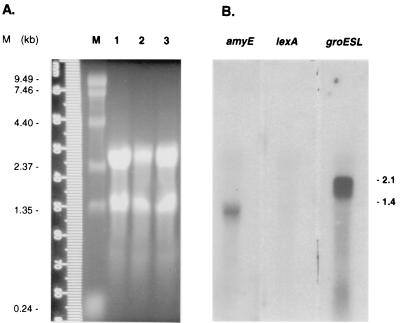

Northern blots and transcriptional start site mapping.

In order to further characterize expression of these genes, Northern blots were carried out. Total RNA was isolated from cells at different points in the growth cycle (Fig. 3A). Subsequent Northern hybridization experiments identified transcripts for amyE and groESL (1.45 and 2.02 kb, respectively) with RNA from early-exponential-phase cells, but we were unable to detect a lexA transcript in any of the RNA preparations (Fig. 3B). For amyE and groESL, the mRNAs detected were the correct size for single-gene and two-gene transcripts, respectively.

FIG. 3.

RNA analyses in wild-type cells of D. radiodurans R1. (A) Formaldehyde gel electrophoresis of total RNA isolated from stationary-phase (lane 1), early-exponential-phase (lane 2), and mid-exponential-phase (lane 3) cells. As a marker, 4 μg of an RNA ladder was applied (lane M). (B) Northern hybridization using probes for amyE, lexA, and groESL. The expected transcript sizes are indicated at the right-hand side of the panel (in kilobases).

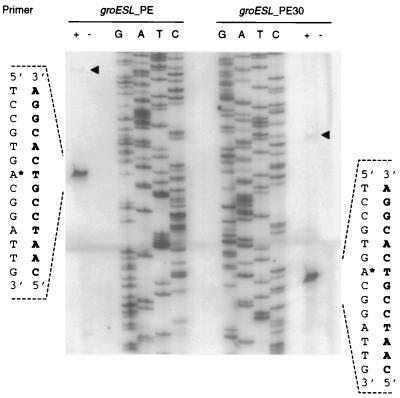

Transcription start sites were successfully mapped for groESL, aceR, and lexA (Table 5), but not for amyE. It is not clear why we were unsuccessful with the amyE promoter, since the Northern blots suggested the presence of a detectable amount of transcript, but several attempts were made with different RNA preparations and different primers and all were unsuccessful. For groESL, a major and a minor band were identified (Fig. 4). Transcription start site mapping experiments for this region were carried out with RNA isolated from cultures grown at 30 and 40°C, and in both cases the same transcription start sites were obtained as major and minor bands. Neither of these corresponds to the ς32-like promoter sequence found in this region, which overlaps but does not coincide with the minor start site (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Alignment of transcription start sites of D. radiodurans R1 genesa

| Promoter | −35 and −10 sequence, +1 nucleotide, and spacing (bp) | Position relative to RBS and ATG |

|---|---|---|

| groESLM | TTGACATTTTTCTTATCGGCGCTCTACCATCCGTGA* (18) | N66-AGGAGGACCCCACATG |

| groESLm | GTCCCAGCGCCCCTTGAGCGTCATAGACTCAGA* (17) | N120-AGGAGGACCCCACATG |

| aceR | GGAACAGCCGGCCTCATTTGCTGTAAAATGAAATC* (17) | N57-AGGAGAACCCCATG |

| lexA | TCCTCGTAGGCCAATTCTGACGGTTGGGCCGCCGCTTG* (17) | N18-GGCAAACTGCGCGCACATG |

| pI3 resU | GGAACCCCGCGCCGACCCCCCTTAATGCGGC* (16) | N119-AGGAGGTTTGAATG |

| pI3 CmrM | GGTCCTCGCCCTCCTTAGGGGCAAGGACGTCCGGC* (18) | N??-?? |

| rpoBC | TTGACAGGGAATCATGAGCGCCCTATACTTTC* (17) | N168-GAGGTGTGCATG |

| E. coli ς70 | TTGACA-N17-TATAAT |

The nucleotides at which transcription is initiated (+1) are marked with the asterisk (*); −35 and −10 sequences are underlined. Start codons are in italics, and the putative ribosome-binding site (RBS) is in bold. Since the region immediately downstream of the transcriptional start site of the promoter driving expression of the Cmr marker was lost during the construction of PI3, the original gene and start codon are not known; this is indicated with question marks. Major (groESLM) and (groESLm) minor start sites are shown, as well as the putative ς32 promoter sequence preceding the groESL operon (double underlined).

FIG. 4.

Transcription start site mapping of the groESL promoter by primer extension. The experiments were performed in either the presence (+) or absence (−) of reverse transcriptase, and the two panels show the results with two different primers (PE and PE30). The flanking sequences represent the upper (lightface) and lower (boldface) this is the strand shown) strands. The nucleotide used as the transcription initiation site is marked with an asterisk. An additional minor cDNA product (◂) was obtained in both reactions; these could reflect an alternative transcription initiation site.

In order to obtain additional start sites and promoter sequences, we selected other genes that were expected to be expressed at detectable levels in exponentially growing cells. For this purpose, the rpoBC (DR0912 to DR0911) genes were chosen, predicted to encode subunits of RNA polymerase (17), and two plasmid-encoded genes in pI3. pI3 is a derivative of a large plasmid found in D. radiodurans SARK that also replicates in D. radiodurans R1 (7), and we have sequenced the Deinococcus insert in pI3 in its entirety (7a). Two plasmid genes were chosen that appeared to be expressed at high levels: resU, encoding a putative resolvase, and the antibiotic selection marker cat. A putative promoter segment for rpoBC was amplified by PCR, and the start site was mapped by primer extension (Table 5). The start sites for the pI3 promoters were mapped directly from pI3 using RNA from a D. radiodurans R1 strain containing pI3. Surprisingly, all seven of the upstream −10 and −35 regions bear a resemblance to the standard E. coli ς70 promoter sequence. The rpoBC and groESL promoters show only one and two differences, respectively, from the ς70 consensus sequence, in both cases in the −10 sequence.

DISCUSSION

Despite the fact that D. radiodurans R1 has been the focus of increasing scientific interest over the past decade, only a limited number of molecular tools for genetic engineering of this radioresistant bacterium are currently available and very little is known about promoters and expression. The present paper describes the development of a series of double-crossover integrative vectors and their use in the cloning and initial characterization of promoters isolated from the D. radiodurans R1 genome and from a cryptic D. radiodurans SARK plasmid.

Although these integrative vectors were used in this study for promoter cloning, they are also useful for general cloning and expression in this strain. These vectors, in combination with the improved transformation protocols described here, will significantly enhance the ability to carry out genetic manipulations in Deinococcus strains.

Of the three potential reporter genes tested, only lacZ was successful for screening of colonies as well as for quantitative assays in cell lysates and in toluene-permeabilized cells. This system was used to identify three promoters with different strengths, one low level (lexA), one moderate level (amyE), and one strong (groESL). It was surprising to find a lexA ortholog in the D. radiodurans R1 genome sequence, because this strain was reported not to have an SOS-like error-prone response to DNA damage (10). Low-level reporter activity was obtained with the fragment tested, but the role of lexA in D. radiodurans R1 remains unclear.

Transcriptional start sites were mapped for five genes, including groESL. Alignment of the −10 and −35 regions of these sequences showed that two strong promoters (groESL and rpoBC) had −10 and −35 regions that were highly similar to the corresponding regions of the E. coli ς70 consensus promoter. This result was surprising because previous reports had suggested that Deinococcus promoters should be significantly different from E. coli promoters (7, 14). The other three regions upstream of mapped transcriptional start sites as well as an additional minor start site for groESL were more divergent, but the −10 and −35 regions still showed some similarity to the E. coli consensus sequence.

The two start sites mapped for groESL were about 60 bp apart. The minor (more upstream) start site overlapped a sequence with good similarity to the E. coli heat shock sigma factor (rpoH) recognition consensus sequence, which is involved in regulation of heat shock genes such as groESL in many bacteria (5). However, the −10 and −35 sequences upstream of this minor start site did not coincide with the same regions in the rpoH recognition sequence. The possibility that the transcription start site might be different under heat shock conditions was addressed. Although the cloned groESL promoter region was found to direct higher expression of the reporter gene under heat shock conditions, suggesting that D. radiodurans mounts a heat shock response, the transcriptional start sites were the same as in cells grown at normal temperatures. The basis for heat shock regulation in D. radiodurans is unknown, and further studies will be required to address this.

The present studies show that it is possible to efficiently insert heterologous genes into the genome of D. radiodurans using the vectors described in this paper. In addition, the constructs containing the various promoters described here can be used for insertional expression vectors with different levels of expression. Such new genetic tools will greatly enhance the ability to carry out genetic manipulations of D. radiodurans for a variety of basic and applied research applications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Valerie Vagner for providing pMUTIN2mcs and Francois Baneyx for helpful discussions. We thank Marion Franke and Khue Quang Trinh for excellent technical assistance. Preliminary sequence data were obtained from the Institute for Genomic Research website at http://www.tigr.org.

This work was funded by a grant from the DOE EMSP program (DEFG0797ER20294).

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson A W, Nordan H C, Cain R F, Parrish G, Duggan D. Studies on a radio-resistant micrococcus. I. Isolation, morphology, cultural characteristics, and resistance to gamma radiation. Food Technol. 1956;10:575–577. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Battista J R. Against all odds: the survival strategies of Deinococcus radiodurans. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1997;51:203–224. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chambers S P, Prior S E, Barstow D A, Minton N P. The pMTL nic-cloning vectors. I. Improved pUC polylinker regions to facilitate the use of sonicated DNA for nucleotide sequencing. Gene. 1988;68:139–149. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90606-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dahl M K, Meinhof C G. A series of integrative plasmids for Bacillus subtilis containing unique cloning sites in all three open reading frames for translational lacZ fusions. Gene. 1994;145:151–152. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Georgopoulos C, Ang D. The Escherichia coli groE chaperonins. Semin Cell Biol. 1990;1:19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim L, Mogk A, Schumann W. A xylose-inducible Bacillus subtilis integration vector and its application. Gene. 1996;181:71–76. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00466-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masters C I, Minton K W. Promoter probe and shuttle plasmids for Deinococcus radiodurans. Plasmid. 1992;28:258–261. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(92)90057-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7a.Meima R, Lidstrom M E. Characterization of the minimal replicon of a cryptic Deinococcus radiodurans SARK plasmid and development of versatile Escherichia coli-D. radiodurans shuttle vectors. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:3856–3867. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.9.3856-3867.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular biology. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minton K W. DNA repair in the extremely radioresistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:9–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray R G E. The family Deinococcaceae. In: Ballows A, Truper H G, Dworkin M, Harder W, Schliefer K H, editors. The prokaryotes. Vol. 4. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1992. pp. 3732–3744. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palmer B R, Marinus M G. The dam and dcm strains of Escherichia coli—a review. Gene. 1994;143:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90597-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ross T K, Achberger E C, Braymer H D. Nucleotide sequence of the McrB region of Escherichia coli K-12 and evidence for two independent translational initiation sites at the mcrB locus. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:1974–1981. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.4.1974-1981.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith M D, Masters C I, Lennon E, McNeil L B, Minton K W. Gene expression in Deinococcus radiodurans. Gene. 1991;98:45–52. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90102-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Vies S M, Georgopoulos C. Regulation of chaperonin gene expression. In: Ellis R J, editor. The chaperonins. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1996. pp. 137–166. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walker G W. Inducible DNA repari systems. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:425–457. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.002233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White O, Eisen J A, Heidelberg J F, Hickey E K, Peterson J D, Dodson R J, Haft D H, Gwinn M L, Nelson W C, Richardson D L, Moffat K S, Qin H, Jiang L, Pamphile W, Crosby M, Shen M, Vamathevan J J, Lam P, McDonald L, Utterback T, Zalewski C, Makarova K S, Aravind L, Daly M J, Fraser C M, et al. Genome sequence of the radioresistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans R1. Science. 1999;286:1571–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5444.1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]