Significance

As a precursor to the essential vitamin tetrahydrofolate, para-aminobenzoate (pABA) is needed for nucleotide and amino acid synthesis. Chlamydia trachomatis, the causative agent of the sexually transmitted infection, lacks the canonical pabABC biosynthetic pathway and instead utilizes a novel stratagem for pABA synthesis that is catalyzed by the enzyme Chlamydia protein associating with death domains (CADD). Originally assigned as a diiron enzyme, we report high in vitro activity relies on the stoichiometric addition of both Fe and Mn. Furthermore, CADD is shown to activate O2 to self-sacrificially produce pABA from Tyr27. This work addresses the unusual mechanism by which Chlamydiae produce pABA, which is a prime target for the development of therapeutic agents to treat infections.

Keywords: folate biosynthesis, radical transfer, spectroscopy, heterobinuclear cluster

Abstract

Chlamydia protein associating with death domains (CADD) is involved in the biosynthesis of para-aminobenzoate (pABA), an essential component of the folate cofactor that is required for the survival and proliferation of the human pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis. The pathway used by Chlamydiae for pABA synthesis differs from the canonical multi-enzyme pathway used by most bacteria that relies on chorismate as a metabolic precursor. Rather, recent work showed pABA formation by CADD derives from l-tyrosine. As a member of the emerging superfamily of heme oxygenase–like diiron oxidases (HDOs), CADD was proposed to use a diiron cofactor for catalysis. However, we report maximal pABA formation by CADD occurs upon the addition of both iron and manganese, which implicates a heterobimetallic Fe:Mn cluster is the catalytically active form. Isotopic labeling experiments and proteomics studies show that CADD generates pABA from a protein-derived tyrosine (Tyr27), a residue that is ∼14 Å from the dimetal site. We propose that this self-sacrificial reaction occurs through O2 activation by a probable Fe:Mn cluster through a radical relay mechanism that connects to the “substrate” Tyr, followed by amination and direct oxygen insertion. These results provide the molecular basis for pABA formation in C. trachomatis, which will inform the design of novel therapeutics.

Chlamydia is the most common bacterial sexually transmitted disease worldwide (1). Infections can occur in diverse cell and tissue types, and if left untreated, can lead to a variety of complications such as pelvic inflammatory disease, epididymitis, and trachoma, which is the leading cause of preventable blindness worldwide. Chlamydiae, which are obligate intracellular bacteria, have adapted to their unique ecological niche through loss of numerous biosynthetic pathways, opting to import key metabolites (e.g., amino acids and ATP) from their mammalian hosts (2). However, the acquisition of niche pathways that can result from adoption of a parasitic lifestyle may also offer a viable strategy for the development of targeted antimicrobial agents.

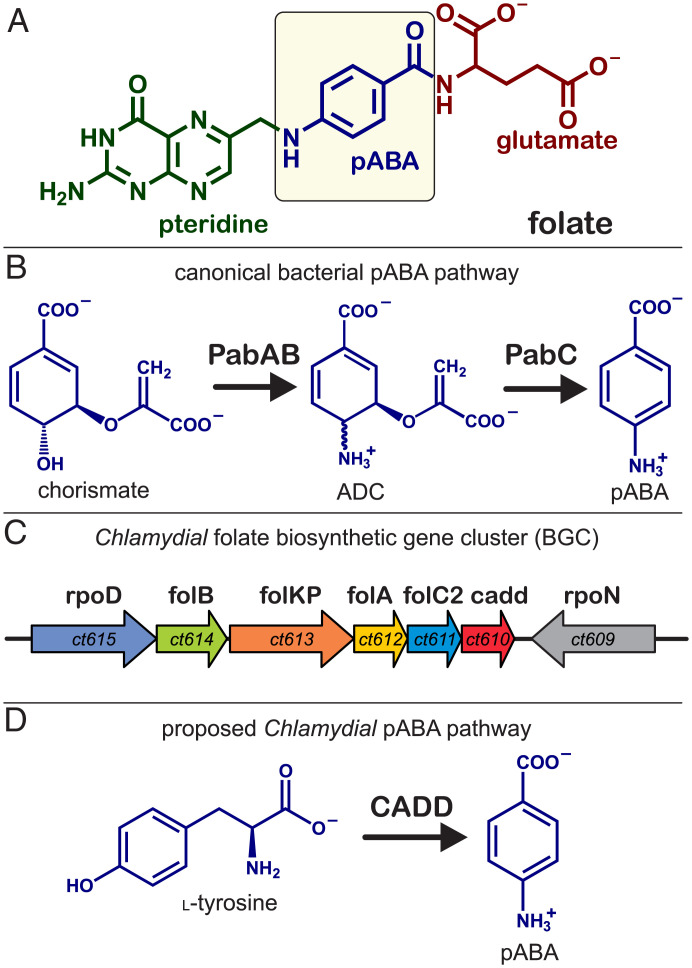

Tetrahydrofolate, a tripartite molecule composed of para-aminobenzoic acid (pABA), glutamate, and pterin (Fig. 1A), is an essential cofactor required for single-carbon transfer processes in the biosynthesis of DNA and amino acids. Its synthesis has been successfully targeted by many antibiotics and cytostatics in the clinic. In most bacteria, the pABA moiety is generated from chorismate using a multistep pathway encoded by the pabABC genes, shown in Fig. 1B. Although the genome of C. trachomatis lacks pabABC, the organism contains the machinery required for downstream pterin assembly and glutamylation and capably synthesizes folate de novo (3–5).

Fig. 1.

Bacterial strategies for the synthesis of folate. (A) Tripartite structure of folate. (B) The canonical pabABC-based strategy for generation of p-aminobenzoic acid. (C) Biosynthetic gene cluster for folate biosynthesis found in C. trachomatis. (D) Proposed pathway for pABA biosynthesis used by Chlamydiae.

An examination of the folate biosynthetic gene clusters in various Chlamydiae reveals a unique and universally conserved open reading frame (ct610), which led to initial speculation that the encoded protein may supplant the function normally provided by pabABC (Fig. 1C). Using a ΔpabABC knockout of Escherichia coli, it was shown that complementation by the ct610 gene, or a related ortholog from Nitrosomonas europaea, rescued pABA auxotrophy and enabled bacterial growth (5, 6). The protein encoded by ct610, termed CADD (or chlamydia protein associating with death domains), has also been shown to have an important secondary role in host cell apoptosis through direct association with tumor necrosis factor family receptors during latter stages of the infectious cycle (7).

The previously solved crystal structure of CADD reveals an overall structural architecture that is similar to heme-oxygenases (HOs) (8). However, the enzyme instead houses a di-metal cofactor. The overall structure and ligation strategy used by CADD, comprised of three histidine and three carboxylate residues, is now known to be very similar to a newly recognized enzyme superfamily that has been termed the HO-like diiron oxidases (HDOs). The HDOs characterized in detail thus far catalyze the iron-dependent activation of O2 (9–13) for a dazzling disposition of substrate transformations that include amine N-oxygenation (14–17), the carbon-carbon cleavage of fatty acids (18) and amino acids (19) to furnish terminal olefin products, and chalkophore biosynthesis (20), among others. The conserved ligand-binding sequence of CADD, the first HDO to be structurally solved, has been used as a query to identify ∼10,000 putative HDOs to date (20, 21); the function of many still await discovery. In the case of the fatty acid decarboxylase UndA, originally designated as a mononuclear-iron enzyme due to a partially occupied metal-binding site in the crystal structure (18), the shared sequence motif with CADD served as the first clue that the enzyme may instead house a dinuclear-iron site. This hypothesis was later supported through spectroscopic and kinetic studies (10, 13).

Despite significant progress in clarifying the early stages for O2-activation and catalytic mechanisms of a select number of HDOs, the transformation that leads to pABA generation by CADD has long remained elusive. Using a ΔpabA knockout/ct610 knockin system, Macias-Orihuela et al. (22) recently identified that when this E. coli strain was supplemented with a ring-deuterated tyrosine, the folate generated largely retained the isotopic label, thus establishing l-tyrosine as the metabolic precursor for pABA (Fig. 1D). Although this study was critical in identifying the putative substrate for CADD, this complex transformation does not have a precedent in enzymatic nor synthetic diiron chemistry, and the details for the conversion of l-tyrosine to pABA remain vague. Progress has largely been hampered by poor activity of the in vitro purified protein.

To begin to define the steps involved in pABA generation by CADD, we report a detailed study of the reaction in vitro. Metal-reconstitution studies suggest that the enzyme requires a heterobinuclear iron:manganese cofactor for activity, rather than the dinuclear-iron cluster used by the limited number of HDOs that have been characterized to date. This high-activity preparation of the enzyme, combined with substrate and oxygen isotope tracer studies and mutagenesis, divulges an O2-dependent, radical-mediated mechanism that results in cleavage of a protein-derived tyrosine that is located over 10 Å from the metal center. This tyrosine is further processed by a cryptic amination and migration to the active-site where it undergoes direct oxygen insertion. These studies expand upon the chemical outcomes and cofactors that are utilized by this emerging class of enzymes. The self-sacrificial cleavage of a tyrosine represents a previously unrecognized posttranslational modification in enzymes capable of radical transfer.

Results

Manganese and Iron Are Both Required for CADD Activity.

Previous metal quantitation studies of CADD that was heterologously expressed in E. coli suggested that the enzyme houses a dinuclear iron cluster (8). When CADD was expressed in minimal media supplemented with iron, the protein was purified to homogeneity and contained ∼1 equivalent of Fe per protein, and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) indicated that no other metals were present in appreciable quantity (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 and Table S1). Other HDOs have also shown variable, and often poor, iron-loading efficiencies that may owe to lability of the cluster after exposure to O2 (9, 12, 21). The optical spectrum of CADD, with an absorption feature at ∼340 nm (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A), is similar to what has been reported for UndA (10) and other diferric enzymes (23–25). To further validate the dinuclear iron assignment, the enzyme was expressed in minimal media supplemented with 57Fe for Mössbauer spectroscopy. The spectrum of the as-isolated protein revealed two quadrupole doublets with parameters that are consistent with high-spin ferric Fe, even though the enzyme was largely EPR silent (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 B and C). This is indicative of a diferric cluster where the two irons are anti-ferromagnetically coupled (S = 0). The Mössbauer spectrum of the chemically reduced enzyme yielded two doublets [δ1 = 1.24 mm/s, ΔEQ1 = 2.02 mm/s, and δ2 = 1.26 mm/s, ΔEQ2 = 2.97 mm/s], features that are highly reminiscent of other HDOs such as UndA (10, 13) and BesC (9, 11) (SI Appendix, Tables S2 and S3). Partial oxidation of the reduced enzyme resulted in an EPR-active species with g-values <2 that are diagnostic of mixed-valent diiron enzymes and model systems [e.g., (23, 26)] (SI Appendix, Fig. S2D). Taken together, the spectroscopic studies all support the presence of a dinuclear iron cluster in CADD as originally suggested in the aforementioned structural work. However, numerous attempts to reconstitute the activity of diiron CADD only resulted in very marginal quantities (≤ 0.001 equivalents per enzyme) of pABA (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Table S4).

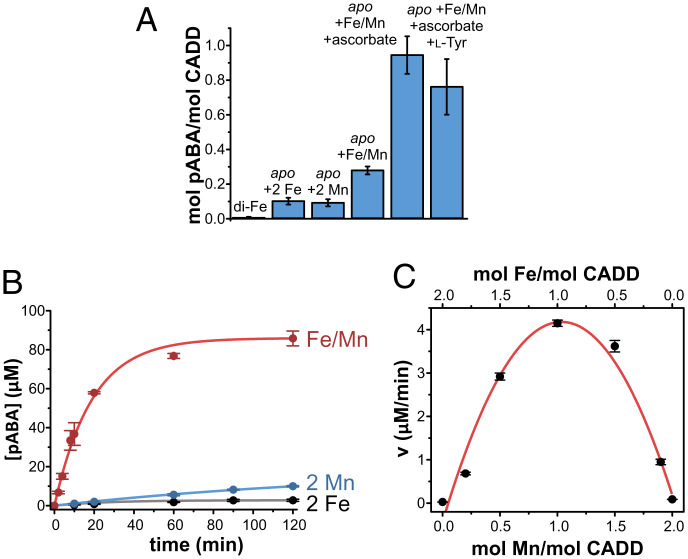

Fig. 2.

Product yields for pABA synthesis by CADD. (A) pABA formation by different preparations of CADD from left to right: diiron CADD (as characterized in SI Appendix, Fig. S2), apo-CADD given 2 molar equivalents Fe, apo-CADD given 2 molar equivalents Mn, apo-CADD given 1 molar equivalent each of Fe and Mn, and the latter with the addition of ascorbate and l-Tyr. Reactions were carried out using 100 μM CADD, 200 μM total metal ([Fe] + [Mn]), 1.25 mM ascorbic acid if indicated, and 200 μM Tyr if indicated. The average pABA production is displayed as one bar with SDs from ≥3 measurements from at least two different preparations of the enzyme. (B) pABA formation over time by apo-CADD reconstituted with 2 molar equivalents of Fe (black), 2 molar equivalents of Mn (blue), or 1 molar equivalent of each Fe and Mn (red) with excess ascorbate. (C) Metal-dependence of the initial velocity of pABA formation by CADD with different ratios of Fe:Mn as shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S4. For (B) and (C), reactions were carried out using 250 μM CADD, 500 μM total metal ([Fe] + [Mn]), and 6.25 mM ascorbic acid.

On the basis of comparably low-activity preparations of CADD and the inability of exogenously added tyrosine to stimulate more pABA production, Macias-Orihuela et al. (22) hypothesized that the enzyme may cleave a protein-derived tyrosine in a sacrificial manner. Despite numerous attempts to purify CADD in an active form through anaerobic purification to circumvent premature reactivity, the enzyme remained largely inactive (SI Appendix, Table S4). We next adopted a mis-metallation approach. Although the enzyme preferably loads Fe when expressed in E. coli, the addition of only Mn to the M9 growth media fortuitously resulted in an apo-enzyme that was largely free of bound metal (SI Appendix, Table S1). However, the addition of Fe(II) to this presumptively unmodified form of CADD again only yielded marginal levels (∼0.1 equivalent/CADD) of pABA production even upon addition of reductants (Fig. 2A).

Given the inability to rescue the activity of apo-CADD with Fe alone, we rationalized that CADD may require a different type of metallocofactor for catalysis. Using the apo-enzyme preparation, we reconstituted the enzyme with varying levels of Fe and Mn, keeping a fixed stoichiometry of two metals added per protein (SI Appendix, Fig. S3), and the highest amount of pABA formed (0.3 equivalents per enzyme) when one equivalent of Fe and Mn were simultaneously added, implicating a heterobimetallic Fe:Mn cofactor. When the redox donor ascorbate was included with Mn, Fe, and apo-CADD, a stoichiometric amount of pABA was produced per CADD (Fig. 2A). Addition of exogenous l-Tyr to the reaction did not enhance activity above 1 pABA per CADD (Fig. 2A). Although this level of product would still appear to be quite minimal for a typical enzyme-catalyzed reaction, and in particular a process that is required for bacterial survival, this represents a significant improvement over our and others’ previous preparations. The time course of pABA formation further displays the necessity for both metals (Fig. 2B). Fitting the linear portions of these plots for a variety of Fe/Mn ratios provided initial reaction velocities, which displayed a clear parabolic dependence on Fe/Mn ratio with a >50-fold increase in pABA formation when both metals were included in the reaction mixture (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Fig. S4). A very similar metal/activity dependence was observed for the heterobinuclear Fe:Mn cofactor of ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) from C. trachomatis that has been spectroscopically and structurally verified to house a mixed-metal cluster (27, 28). Initial attempts to spectroscopically characterize the mixed-metal cluster in various oxidation states were unsuccessful, likely owing to the cluster instability that is a shared attribute for many HDOs (9, 12, 16, 21).

A Protein-Derived Tyrosine Serves As the CADD Substrate.

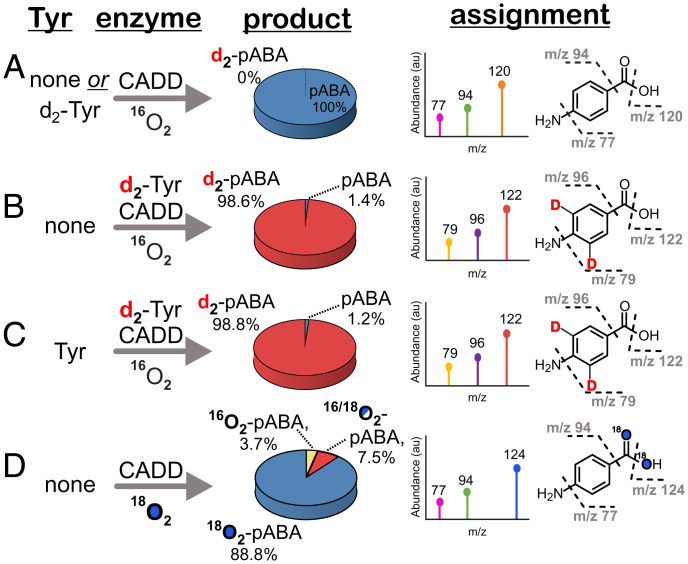

The stoichiometric production of pABA and inability for exogenously added l-Tyr to stimulate further metabolite production even in the “high-activity” Fe/Mn preparation (Fig. 2A) prompted us to more closely evaluate the hypothesis that a protein-derived tyrosine could serve as the CADD “substrate.” Using a targeted mass spectrometry (MS) approach described in SI Methods, we evaluated the isotopic composition of pABA using CADD that was expressed in the presence of 3,5-d2-l-tyrosine. Unlike pABA from the unlabeled enzyme (Fig. 3A), the pABA produced contained a major (∼99%) product with m/z +2 fragmentation peaks (m/z = 79, 96, 122) relative to those corresponding to the unlabeled product (m/z = 77, 94, 120), consistent with the incorporation of two ring deuterons (Fig. 3B). A very minor (∼1%) fraction of pABA remained unlabeled, most likely arising from the incomplete incorporation of the labeled amino acid during protein expression. The incorporation of the isotopic label into the major product was further validated by high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) studies, which show fragmentation patterns and exact masses that are in excellent agreement with the assignments shown in Fig. 3 (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 A and B). To further rule out the possibility that the presence of an adventitiously bound, nonprotein derived tyrosine led to the integration of the label into the product, both the unlabeled and d2-Tyr-labeled forms of CADD were provided excess l-tyrosine that contained the opposite isotopic label. The resulting isotopic composition of pABA remained unchanged in all cases (Fig. 3 A and C).

Fig. 3.

Targeted mass spectrometry of pABA produced from CADD under varying conditions. MS analysis of pABA produced from reactions of (A) unlabeled CADD with or without exogenous 3,5-d2-labeled Tyr, (B) isotopically labeled d2-Tyr-CADD, (C) isotopically labeled d2-Tyr-CADD in the presence of two equivalents of unlabeled tyrosine, and (D) unlabeled CADD and 18O2. All reactions contained 100 μM CADD, 100 μM ferrous ammonium sulfate, 100 μM MnCl2, and 1.25 mM ascorbic acid. 200 μM Tyr or 3,5-d2-Tyr was included as specified.

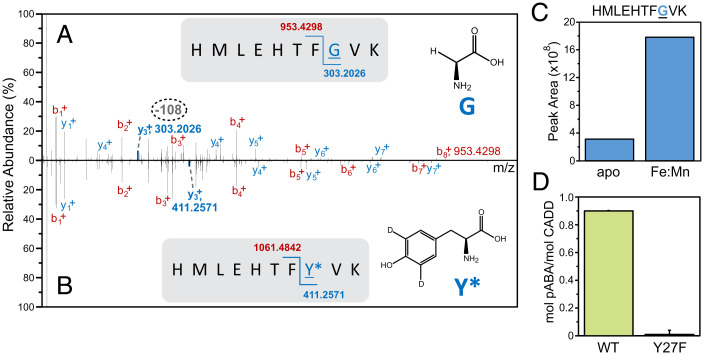

We next sought to provide further evidence for the cleavage of a protein-derived amino acid as the metabolic precursor of pABA and to determine its precise location through HRMS-based proteomics approaches. To facilitate detection, the 3,5-d2-Tyr-labeled CADD was analyzed by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and examined for the loss of a d2-tyrosine side-chain (with a predicted Δm/z = –108.0546) using reaction conditions that produced stoichiometric pABA (i.e., Fe/Mn/excess ascorbate). Detailed evaluation of the resulting tryptic fragments (∼80% protein coverage) revealed that such a modification was prevalent on one peptide. A comparison of the MS spectra of this region is shown in Fig. 4A and reveals an m/z change of –108 on the y3+ ion, which corresponds to cleavage of a Tyr27 side chain that results in the effective substitution of a Gly at this position. Although the proteomics methods applied here preclude an absolute quantification of the modified peptide, the relative abundance of the modification in apo and Fe/Mn CADD from extracted ion chromatograms shows a clear difference in the extent of side-chain loss, with a significantly greater abundance of modified peptide in the Fe:Mn sample (Fig. 4C and SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S7). This is consistent with the results for pABA production.

Fig. 4.

Verification of the self-sacrificing nature of CADD. MS2 spectra of major products of tryptic-digested CADD postreaction (A and B). The modified peptide fragment (y3+, m/z = 303.2026) displaying a mass loss of 108 at position Y27 is bolded in blue (Top), and the same fragment lacking the –108 modification (m/z = 411.2571) is bolded in blue (Bottom). (C) Abundances of the modification shown in (A) in metal-free or Fe:Mn CADD were estimated from the EIC peak area of the precursor peptide (SI Appendix, Fig. S4), which was m/z 400.2061 (z = 3) for HMLEHTFGVK. (D) Production of pABA by WT and Y27F CADD. Reactions were carried out using 100 μM WT or Y27F CADD, 100 μM each ferrous ammonium sulfate and manganese(II) chloride, and 1.25 mM ascorbic acid.

Remarkably, Tyr27 resides ∼14 Å from the dimetal site. This distance would appear to prohibit a C–C cleavage mechanism that is initiated via direct C–H abstraction by an activated (e.g., peroxo or oxo) form of the Fe:Mn cluster nor a process that is directed by prior oxygen insertion (29). Instead, this suggests that a long-range radical process is more likely operative. Accordingly, the mutagenesis of Tyr27 to a redox-inactive residue (Tyr27Phe) eliminated pABA production, in excellent agreement with the proteomics data presented here (Fig. 4D and SI Appendix, Figs. S6C and S7B).

Identification of the CADD Cosubstrate and Formation of the pABA Carboxylate.

In addition to side-chain cleavage, the conversion of a protein-derived tyrosine to pABA also necessitates the integration of two oxygen atoms, presumably at the Cβ position. Such a process is more difficult to rationalize as occurring via a long-range process unless an activated form of O2 is utilized by the enzyme. The exclusion of O2 from a reaction mixture comprised of apo-CADD, Mn, Fe, and ascorbate completely abolished pABA formation. The inclusion of superoxide dismutase (SOD) or catalase as scavengers for reactive oxygen species only had negligible effects on activity (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). Thus, we propose that CADD, unlike the Mn2-dependent class Ib RNRs that require superoxide as an oxidant (30), utilizes O2 as a cosubstrate like other HDOs. Isotopic tracer studies with 18O2 were used to further determine the source of the pABA carboxylate. MS analysis revealed a total of three different forms of pABA in varying ratios (Fig. 3D and SI Appendix, Fig. S9). The m/z = 142.1 for the major (88.8%) product is consistent with the predominant integration of two 18O atoms into the carboxylate moiety. The mass spectra of minor products (m/z =140.1, 7.5% and m/z =138.1, 3.7%) arise from 18O/16O- or 16O/16O-pABA, respectively. The ramifications of this labeling pattern are considered further in the following section.

Discussion

The current results show that CADD requires both manganese and iron for activity, thus expanding the cofactors known to be utilized by HDOs. The accommodation of Mn in the place of Fe has been shown for a few homologous enzymes that perform nonhydrolytic chemistry whose mechanisms require transient changes in the metal redox state during catalysis. For mononuclear enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), the secondary coordination sphere serves to attenuate the redox potential (Eo) of the associated metal center through the presence/absence of a hydrogen-bond donor to a bound water/hydroxide ligand and thus compensates for the large potential differences that are normally inherent to metal identity (the Eo is ∼0.8 V higher for the aqueous Mn3+/Mn2+ couple relative to Fe3+/Fe2+) (13, 31). On the other hand, Mn and Fe are functionally interchangeable in homoprotocatechuate dioxygenases, where it is thought that the facile accommodation of the nonphysiological metal for catalysis is enabled by rapid electron transfer from the substrate to minimize the impact of metal substitution on resulting steady-state kinetic parameters (32).

Prior to this work, heterobimetallic Fe:Mn cofactors had only been identified in the ferritin structural family and notably in the R2 subunit of the Ic subclass Chlamydia trachomatis RNR (R2c) (28) and in the R2-like ligand binding oxidases (R2lox) (33). In both cases, only subtle structural reconfigurations are accompanied with a change in metal preference, and as a result, both enzymes are readily reconstituted in vitro with Fe2 sites that are largely nonfunctional (28, 34). This is very similar to what is observed here for CADD. Thus, proper cofactor generation is either enabled by the accumulation of subtle structural factors that disfavor mis-metalation (R2lox) (35, 36) or is finely regulated in vivo by metal availability, redox state, or auxiliary protein factors (R2c) (37). The favored incorporation of Fe into CADD expressed in E. coli and similarity in the structurally validated (13, 21) or predicted (19, 20, 38) primary ligation sphere of other HDOs suggests the latter scenario is likely operant. This may represent a common strategy used by intracellular bacteria to adapt to changes in host cellular iron status. However, this feature also cautions against cofactor assignment for new HDOs on the grounds of spectroscopy or metal-counting methods prior to the availability of functional data.

The R2c and R2lox examples also highlight the catalytic flexibility for Fe:Mn cofactors for one- and two-electron redox processes. Both enzymes utilize Fe2+/Mn2+ for the activation of O2 and use a suite of activated-O2 intermediates that are functionally (and potentially structurally) similar to those characterized for their Fe2 counterparts. Kinetic studies of R2lox have shown the transient formation of a heterobimetallic Mn3+/Fe3+-peroxo n the reaction with O2 that forms prior to crosslink formation (39). Likewise, R2c has been shown to form an Fe4+/Mn4+-oxo intermediate (40) en route to generation of the Fe3+/Mn4+ state that is analogous to the X intermediate found in class Ia RNRs (41). In the case of R2c, the Mn site serves to replace a nearby tyrosine (42) that normally acts as the primary initiation site for radical transfer in class Ia Fe2-dependent RNRs (43). Although the native function for R2lox is unknown, it performs the two-electron oxidation of the protein framework during cluster assembly that results in the generation of a valine-to-tyrosine ether crosslink; a Fe4+/Mn4+ intermediate has similarly been invoked as the primary oxidant. The demonstration that CADD utilizes a heterobinuclear Fe:Mn cofactor necessitates the reconsideration of the HDO family as the “heme oxygenase-like dimetal oxidases.”

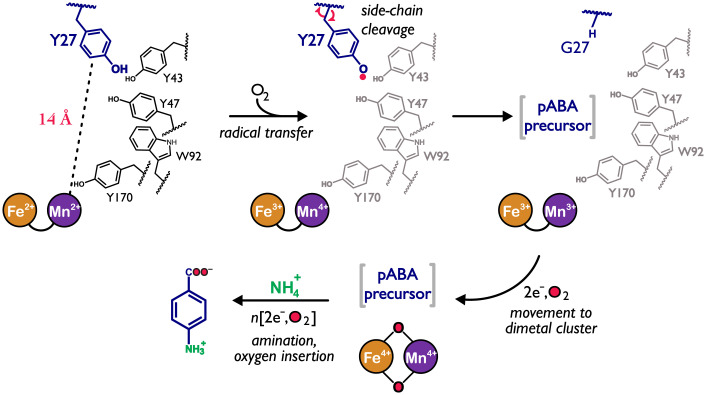

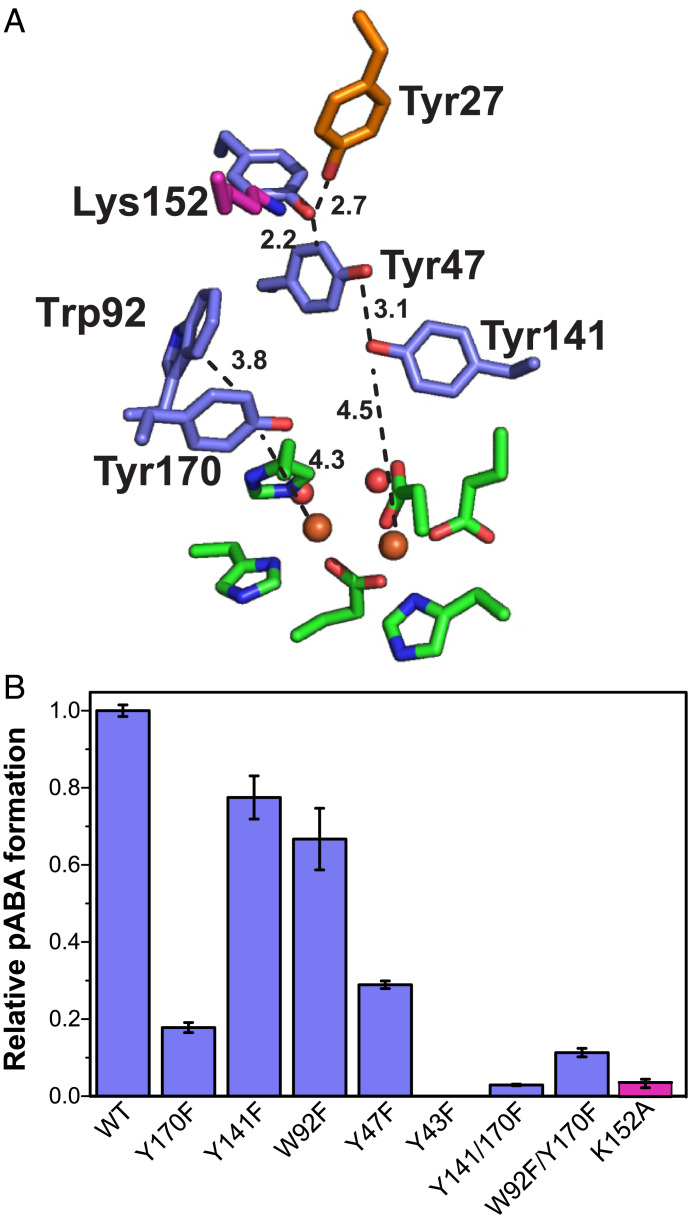

CADD apparently accomplishes both one- and two-electron oxidation chemistries within the same protein scaffold, and we propose a mechanism in Fig. 5 that unifies our current data with the aforementioned mechanistic paradigms. The importance of a largely conserved radical transfer chain that leads to Y27 is suggested by the crystal structure of CADD (8) and sequence comparison to orthologs that were judiciously selected from HDOs that are similarly located within folate BGCs (Fig. 6A and SI Appendix, Fig. S10). Mutagenesis studies further reinforce the importance of this putative radical transfer network and surrounding Y27 environment for pABA formation (Fig. 6B). Notably, UndA has been shown to generate a minor amount of Tyr radical species in what is thought to be a noncatalytic “off-pathway” process (13), suggesting that the active-oxidant for UndA may bear similarity to what we currently presume to be a Fe4+/Mn4+ species that is operant in CADD. Nonetheless, the large degree of integration of 18O2 into the final pABA product highlights that the enzyme is also competent of oxygen-insertion chemistry and alludes to a mechanism where the Tyr side chain, once cleaved, migrates into the active-site for further processing to form the pABA carboxylate through a multistep oxidation process, as characterized in other metalloenzymes such as cytochrome P450s (44). Multiple rounds (three or more) of O2-activation would then be required, in accord with the ∼0.3 equivalents of pABA that is produced in the absence of exogenous reductant. The minor amounts of unlabeled 16O/16O pABA in the reaction with 18O2 is likely attributed to slow exchange of the carboxylate with solvent or from the oxo/hydroxo ligand-exchange, which is a hallmark for enzymes that utilize high-valent species (45).

Fig. 5.

Proposal for the catalytic mechanism of CADD. Oxygen activation by the heterobimetallic Fe:Mn cluster results in long-range electron transfer through a series of oxidizable aromatic amino acids to the “substrate” Tyr27. The Tyr27 radical prompts homolytic Cα–Cβ scission and subsequent release of the side-chain moiety, which then migrates to the active site for direct oxygen insertion by the Fe:Mn cofactor. The remaining step to form pABA is amination of C4. However, this step may occur concomitant with side-chain cleavage.

Fig. 6.

Importance of radical transfer chain and Tyr27 environment on pABA formation by CADD. (A) The crystal structure of diferric CADD [PDB: 1RCW (8)] with the “substrate” tyrosine shown in red, potential residues in the radical transfer chain shown in blue, and ligands to the diiron cluster and Lys152 are shown in green and purple respectively. Distance labels represent the closest pairs of atoms. (B) Production of pABA by WT CADD and mutants in which the oxidizable amino acids are replaced with Phe or the neighboring Lys152 is replaced with Ala. Reactions were carried out using 100 μM CADD (WT or mutant), 100 μM each ferrous ammonium sulfate and manganese(II) chloride, and 1.25 mM ascorbic acid. Error bars represent the SD of ≥3 replicates.

To our knowledge, the cleavage of a tyrosine side chain represents a previously uncharacterized posttranslational modification for proteins. Oxidation of the protein framework is known to occur in many metalloenzymes that form powerful oxidants, and as Gray and Winkler (46) have proposed, may serve as a mechanism to shunt oxidative damage to the protein surface. Nonetheless, photochemical studies of proteins in vitro have afforded the type of radical-initiated homolytic cleavage at Cα–Cβ that is depicted in Fig. 5 (47), which would afford the formation of a glycyl radical at this position. It is thought that formation of a Tyr/Trp radical cation may favor this type of cleavage and hence the propensity for side-chain loss is very likely promoted by the surrounding protein microenvironment. Accordingly, the elimination of hydrogen-bonding interactions to Y27 result in a large reduction of CADD activity (Fig. 6B).

The loss of the Tyr27 side chain and its incorporation into the product pABA confirm previous hypotheses that CADD functions as a suicidal enzyme capable of only one turnover. We note that the precise source of the amine that is integrated into pABA remains unclear; however, 15N isotopic-labeling experiments suggest that it also derives from the protein (SI Appendix, Fig. S11). Although self-sacrificing enzymes are quite rare, there are precedents that may provide rationales for such a mechanism being operant in CADD, and more broadly, aid in the generation of antibiotics that target Chlamydial folate biosynthesis. For the enzyme Ada, the repair of DNA lesions occurs through the irreversible transfer of a methyl group to an active-site cysteine (48); the inactivated protein can act as a transcriptional activator for the induction of other DNA repair enzymes (49). It is similarly hypothesized that Thi4p, which donates a cysteine sulfur for thiazole-ring formation during thiamine synthesis, may also have a role in mediating yeast stress responses (50). It is tempting to propose that the inactivated form of CADD may also have an important secondary role, particularly in light of its function for mediating host cell apoptosis through direct protein:protein interactions. Nonetheless, the interruption of tyrosine cleavage or further modification to produce pABA could provide important new therapeutic strategies.

Materials and Methods

The expression and purification of CADD in various metal bound states and isotopically labeled forms is described in SI Appendix, including the source of reagents and routine procedures such as activity assays, mutagenesis, and pABA product analysis by LC-MS. The SI Appendix also describes the procedures for spectroscopic characterization of CADD in the diiron-loaded form and proteomics analysis.

Time-Dependent Activity Assays.

Time-course experiments were carried out using 250 μM apo CADD, 2 molar equivalents total of Fe and Mn (via anaerobic stock solutions of ferrous ammonium sulfate and manganese(II) chloride) at varying ratios, and 6.25 mM ascorbate. The reactions were carried out at room temperature. Reactions were quenched at specific time-points by combining with an equal volume of acetonitrile (ACN). The protein precipitate was pelleted by centrifugation, and the supernatant was stored at –20 °C before analysis for pABA quantification by ultra-performance liquid chromatography. Targeted and untargeted mass spectrometry data acquisition and processing is described in the SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health (GM135315 to T.M.M. and GM125924 to Y.G.). D.A.M. was partially supported by NSF-STEM training grant 1643814. This work was performed in part by the Molecular Education, Technology and Research Innovation Center (METRIC) at NC State University, which is supported by the state of North Carolina. We would like to acknowledge Jeffrey Enders of METRIC for performing ICP-MS to determine metal content of CADD.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See online for related content such as Commentaries.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2210908119/-/DCSupplemental.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2019. (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2021).

- 2.Stephens R. S., et al. , Genome sequence of an obligate intracellular pathogen of humans: Chlamydia trachomatis. Science 282, 754–759 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Crécy-Lagard V., El Yacoubi B., de la Garza R. D., Noiriel A., Hanson A. D., Comparative genomics of bacterial and plant folate synthesis and salvage: Predictions and validations. BMC Genomics 8, 245 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fan H., Brunham R. C., McClarty G., Acquisition and synthesis of folates by obligate intracellular bacteria of the genus Chlamydia. J. Clin. Invest. 90, 1803–1811 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams N. E., et al. , Promiscuous and adaptable enzymes fill “holes” in the tetrahydrofolate pathway in Chlamydia species. MBio 5, e01378-14 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Satoh Y., Kuratsu M., Kobayashi D., Dairi T., New gene responsible for para-aminobenzoate biosynthesis. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 117, 178–183 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stenner-Liewen F., et al. , CADD, a Chlamydia protein that interacts with death receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 9633–9636 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwarzenbacher R., et al. , Structure of the Chlamydia protein CADD reveals a redox enzyme that modulates host cell apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 29320–29324 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manley O. M., et al. , BesC Initiates C-C cleavage through a substrate-triggered and reactive diferric-peroxo intermediate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 21416–21424 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manley O. M., Fan R., Guo Y., Makris T. M., Oxidative decarboxylase UndA utilizes a dinuclear iron cofactor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 8684–8688 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McBride M. J., et al. , Substrate-triggered μ-peroxodiiron(III) intermediate in the 4-Chloro-l-lysine-fragmenting heme-oxygenase-like diiron oxidase (HDO) BesC: Substrate dissociation from, and C4 Targeting by, the intermediate. Biochemistry 61, 689–702 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McBride M. J., et al. , A peroxodiiron(III/III) intermediate mediating both N-hydroxylation steps in biosynthesis of the N-nitrosourea pharmacophore of streptozotocin by SznF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 11818–11828 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang B., et al. , Substrate-triggered formation of a peroxo-Fe2(III/III) intermediate during fatty acid decarboxylation by UndA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 14510–14514 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He H. Y., Henderson A. C., Du Y. L., Ryan K. S., Two-enzyme pathway links L-arginine to nitric oxide in N-nitroso biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 4026–4033 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hedges J. B., Ryan K. S., In vitro reconstitution of the biosynthetic pathway to the nitroimidazole antibiotic azomycin. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 58, 11647–11651 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ng T. L., Rohac R., Mitchell A. J., Boal A. K., Balskus E. P., An N-nitrosating metalloenzyme constructs the pharmacophore of streptozotocin. Nature 566, 94–99 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimo S., et al. , Stereodivergent nitrocyclopropane formation during biosynthesis of belactosins and hormaomycins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 18413–18418 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rui Z., et al. , Microbial biosynthesis of medium-chain 1-alkenes by a nonheme iron oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 18237–18242 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marchand J. A., et al. , Discovery of a pathway for terminal-alkyne amino acid biosynthesis. Nature 567, 420–424 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patteson J. B., et al. , Biosynthesis of fluopsin C, a copper-containing antibiotic from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Science 374, 1005–1009 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McBride M. J., et al. , Structure and assembly of the diiron cofactor in the heme-oxygenase-like domain of the N-nitrosourea-producing enzyme SznF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2015931118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Macias-Orihuela Y., et al. , An unusual route for p-aminobenzoate biosynthesis in Chlamydia trachomatis involves a probable self-sacrificing diiron oxygenase. J. Bacteriol. 202, e00319–e00320 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Makris T. M., Chakrabarti M., Münck E., Lipscomb J. D., A family of diiron monooxygenases catalyzing amino acid beta-hydroxylation in antibiotic biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 15391–15396 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathevon C., et al. , tRNA-modifying MiaE protein from Salmonella typhimurium is a nonheme diiron monooxygenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 13295–13300 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Behan R. K., Lippard S. J., The aging-associated enzyme CLK-1 is a member of the carboxylate-bridged diiron family of proteins. Biochemistry 49, 9679–9681 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park Y. J., et al. , A mixed-valent Fe(II)Fe(III) species converts cysteine to an oxazolone/thioamide pair in methanobactin biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 119, e2123566119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andersson C. S., et al. , The manganese ion of the heterodinuclear Mn/Fe cofactor in Chlamydia trachomatis ribonucleotide reductase R2c is located at metal position 1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 123–125 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang W., et al. , A manganese(IV)/iron(III) cofactor in Chlamydia trachomatis ribonucleotide reductase. Science 316, 1188–1191 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cryle M. J., De Voss J. J., Carbon-carbon bond cleavage by cytochrome p450(BioI)(CYP107H1). Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 86–87, 86–87 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.J. A. Cotruvo, Jr, Stich T. A., Britt R. D., Stubbe J., Mechanism of assembly of the dimanganese-tyrosyl radical cofactor of class Ib ribonucleotide reductase: Enzymatic generation of superoxide is required for tyrosine oxidation via a Mn(III)Mn(IV) intermediate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 4027–4039 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vance C. K., Miller A. F., A simple proposal that can explain the inactivity of metal-substituted superoxide dismutases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 461–467 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emerson J. P., Kovaleva E. G., Farquhar E. R., Lipscomb J. D., L. Que, Jr, Swapping metals in Fe- and Mn-dependent dioxygenases: Evidence for oxygen activation without a change in metal redox state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 7347–7352 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andersson C. S., Högbom M., A Mycobacterium tuberculosis ligand-binding Mn/Fe protein reveals a new cofactor in a remodeled R2-protein scaffold. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 5633–5638 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Voevodskaya N., Lendzian F., Ehrenberg A., Gräslund A., High catalytic activity achieved with a mixed manganese-iron site in protein R2 of Chlamydia ribonucleotide reductase. FEBS Lett. 581, 3351–3355 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shafaat H. S., et al. , Electronic structural flexibility of heterobimetallic Mn/Fe cofactors: R2lox and R2c proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 13399–13409 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kisgeropoulos E. C., et al. , Key structural motifs balance metal binding and oxidative reactivity in a heterobimetallic Mn/Fe protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 5338–5354 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.J. M. Bollinger, Jr, Jiang W., Green M. T., Krebs C., The manganese(IV)/iron(III) cofactor of Chlamydia trachomatis ribonucleotide reductase: Structure, assembly, radical initiation, and evolution. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 18, 650–657 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pang L., et al. , In vitro characterization of a nitro-forming oxygenase involved in 3-(trans-2’-aminocyclopropyl) alanine biosynthesis. Eng. Microbiol. 2, 100007 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller E. K., Trivelas N. E., Maugeri P. T., Blaesi E. J., Shafaat H. S., Time-resolved investigations of heterobimetallic cofactor assembly in R2lox reveal distinct Mn/Fe intermediates. Biochemistry 56, 3369–3379 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang W., Hoffart L. M., Krebs C., J. M. Bollinger, Jr, A manganese(IV)/iron(IV) intermediate in assembly of the manganese(IV)/iron(III) cofactor of Chlamydia trachomatis ribonucleotide reductase. Biochemistry 46, 8709–8716 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.J. M. Bollinger, Jr, et al. , Mechanism of assembly of the tyrosyl radical-dinuclear iron cluster cofactor of ribonucleotide reductase. Science 253, 292–298 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Larsson A., Sjöberg B. M., Identification of the stable free radical tyrosine residue in ribonucleotide reductase. EMBO J. 5, 2037–2040 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Högbom M., et al. , The radical site in chlamydial ribonucleotide reductase defines a new R2 subclass. Science 305, 245–248 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guengerich F. P., Sohl C. D., Chowdhury G., Multi-step oxidations catalyzed by cytochrome P450 enzymes: Processive vs. distributive kinetics and the issue of carbonyl oxidation in chemical mechanisms. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 507, 126–134 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bernadou J., Meunier B., ‘Oxo-hydroxo tautomerism’ as useful mechanistic tool in oxygenation reactions catalysed by water-soluble metalloporphyrins. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 2167–2173 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gray H. B., Winkler J. R., Hole hopping through tyrosine/tryptophan chains protects proteins from oxidative damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 10920–10925 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kang H., Tolbert T. J., Schöneich C., Photoinduced tyrosine side chain fragmentation in IgG4-Fc: Mechanisms and solvent isotope effects. Mol. Pharm. 16, 258–272 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Olsson M., Lindahl T., Repair of alkylated DNA in Escherichia coli. Methyl group transfer from O6-methylguanine to a protein cysteine residue. J. Biol. Chem. 255, 10569–10571 (1980). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sedgwick B., Robins P., Totty N., Lindahl T., Functional domains and methyl acceptor sites of the Escherichia coli ada protein. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 4430–4433 (1988). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chatterjee A., et al. , Saccharomyces cerevisiae THI4p is a suicide thiamine thiazole synthase. Nature 478, 542–546 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.