Significance

Detecting genetic variants associated with the variance of complex traits can provide crucial insights into the interplay between genes and environments and how they jointly shape human phenotypes in the population. We propose a new method to estimate genetic effects on trait variability that address critical limitations in existing approaches. Applied to UK Biobank, our method identified 11 variance quantitative trait loci (vQTLs) for body mass index (BMI) that have not been previously reported. Variance polygenic scores based on our method’s effect estimates showed superior predictive performance on both population-level and within-individual BMI variability compared to existing approaches. It is a unified framework to quantify genetic effects on the phenotypic variability at both single-variant and variance polygenic score levels and may have broad applications in future gene–environment interaction studies.

Keywords: vQTL, quantile regression, GxE, vPGS

Abstract

Detecting genetic variants associated with the variance of complex traits, that is, variance quantitative trait loci (vQTLs), can provide crucial insights into the interplay between genes and environments and how they jointly shape human phenotypes in the population. We propose a quantile integral linear model (QUAIL) to estimate genetic effects on trait variability. Through extensive simulations and analyses of real data, we demonstrate that QUAIL provides computationally efficient and statistically powerful vQTL mapping that is robust to non-Gaussian phenotypes and confounding effects on phenotypic variability. Applied to UK Biobank (n = 375,791), QUAIL identified 11 vQTLs for body mass index (BMI) that have not been previously reported. Top vQTL findings showed substantial enrichment for interactions with physical activities and sedentary behavior. Furthermore, variance polygenic scores (vPGSs) based on QUAIL effect estimates showed superior predictive performance on both population-level and within-individual BMI variability compared to existing approaches. Overall, QUAIL is a unified framework to quantify genetic effects on the phenotypic variability at both single-variant and vPGS levels. It addresses critical limitations in existing approaches and may have broad applications in future gene–environment interaction studies.

Human complex phenotypes are shaped by numerous genetic and environmental factors as well as their interactions (1). Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have identified tens of thousands of reproducible genetic associations (2). However, there has been limited success in detecting interactions between human genetic variants and environmental factors (GxE) (3), in part due to the polygenic nature of human traits, small effect sizes of GxE interactions, and a high multiple testing burden (4). An alternative approach is to first quantify the overall genetic propensity in the form of polygenic scores (PGSs) for each individual and then test the interactions between PGS and environmental risk factors (5–9). Here, PGS is a sum of trait-associated alleles across many genetic loci, typically weighted by marginal effect sizes estimated from a GWAS.

However, genetic variants affect not only the level of traits but also the variability (10–12). Since the variance of a quantitative phenotype differs with the genotype of variants involved in GxE interactions, one can use genetic variants associated with the trait variability (variance quantitative trait loci [vQTLs]) to screen for candidate GxE interactions (13–16). The concept of PGS, which estimates the conditional mean of the phenotype (17), has also been extended into genome-wide summaries of genetic effects on phenotypic variability (variance polygenic scores [vPGSs]) (18, 19). These scores, which reflect the genetic contribution to outcome plasticity, have suggested unique genetic contributions orthogonal to that of traditional PGSs and have achieved some recent successes in GxE studies (18, 20).

Robust vQTL findings can be used to prioritize candidate variants in GxE analysis. vPGS also has the potential to aggregate information across numerous genetic loci and improve both statistical power and biological interpretability of GxE studies. However, existing statistical methods for vQTLs and vPGSs have limitations (21, 22). Levene’s test (LT) (23) and deviation regression model (DRM) (13) are robust to model misspecification but do not adjust for confounding effects on trait variance (24, 25). Additionally, these methods cannot be applied to continuous predictors (e.g., vPGSs) because they require the phenotypic mean or median within each category of the predictor (e.g., genotype groups) as input. Heteroskedastic linear mixed models (HLMMs) can adjust for covariates but are sensitive to model misspecification and have type I error inflation when applied to nonnormal phenotypes (14, 16, 26). Furthermore, although it is straightforward to calculate vPGSs by using vQTL effects as variant weights, predictive performance of vPGSs has not been properly benchmarked because of a lack of statistical metrics for variance prediction. There is a need for a unified framework that can accurately and robustly quantify the genetic effects on phenotypic variability at the single variant as well as the vPGS level.

In this work, we introduce a quantile integral linear model (QUAIL), a quantile regression-based framework to estimate genetic effects on the variance of quantitative traits. Our approach can adjust for confounding effects on both the level and the variance of phenotypic outcomes, can be applied to both categorical and continuous predictors, and does not impose strong assumptions on the distribution of phenotypes. We demonstrate the performance of QUAIL through extensive simulations, vQTL mapping for body mass index (BMI) in UK Biobank, GxE enrichment analysis, and vPGS benchmarking and application.

Results

Method Overview.

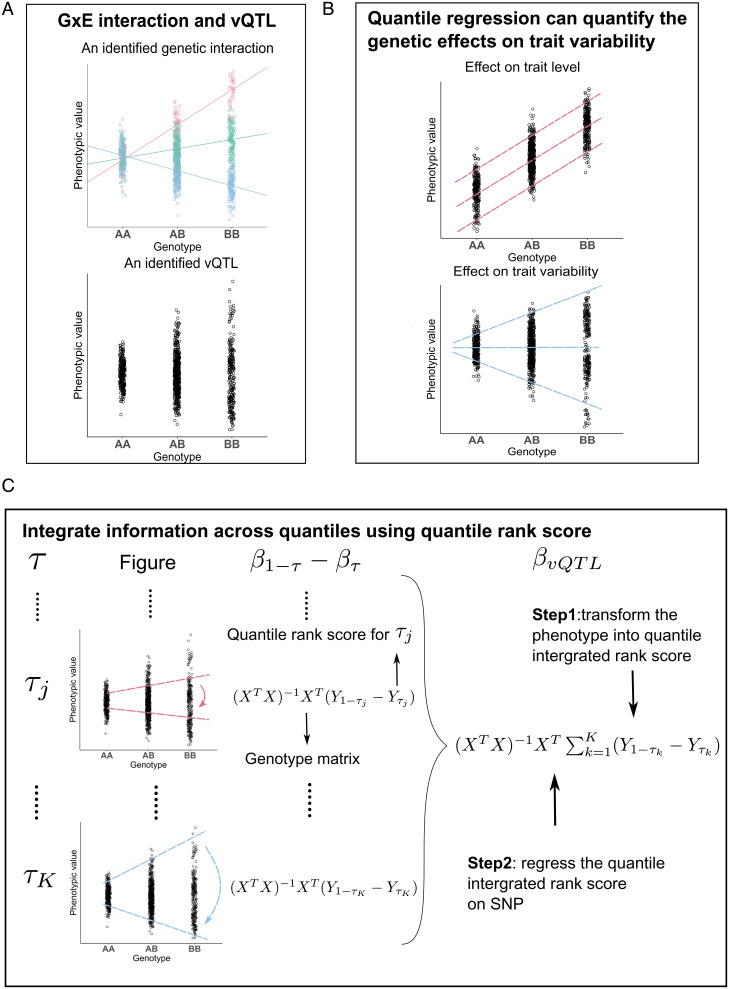

The goal of vQTL mapping is to identify single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) showing differential variability of a quantitative trait across genotype groups. If an SNP has substantially different effects on trait values given different environmental exposures, it will be a vQTL without conditioning on the environment (Fig. 1A). Quantile regression estimates the conditional quantile function of a response variable given predictors (27). If an SNP G is a vQTL for trait Y, the conditional quantile function will have different regression slopes (i.e., βτ) for different quantile levels τ (Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Note S1) (28).

Fig. 1.

Workflow of QUAIL. (A) The phenotypic variance varies across genotype groups in the presence of vQTL and GxE effects. The data points are colored based on the level of the environmental variable. The lines represent genetic effects on the phenotype conditioning on the environmental variable. (B) Quantile regression can be used to detect vQTLs. The quantile regression slopes will be different across quantile levels if a genetic effect on trait variability exists. (C) Workflow of the QUAIL estimation procedure. τ indicates a specific quantile level. β1−τ − βτ indicates the difference between the regression coefficients of the upper and lower quantile levels. βvQTL denotes the aggregated genetic effect on trait variability across quantile levels.

For a pair of quantile levels , the vQTL effect of an SNP can be quantified by using the difference between the regression coefficients of the upper and lower quantile levels, that is, .

To aggregate information across all quantile levels and better quantify the vQTL effect on trait Y, we introduce a quantile-integrated effect (29):

Note that when the SNP is not associated with trait variability, we have for any . Therefore, testing the vQTL effect of an SNP is equivalent to testing the hypothesis:

However, approximating βQI by using a standard quantile regression fitting procedure involves iterative optimization for numerous quantile levels and thus is computationally challenging in genome-wide analysis. We apply several computational techniques to ensure that QUAIL can efficiently identify vQTLs at the genome-wide scale. We first transform the phenotype into an integrated quantile rank score by using only trait values and covariates. Next, we regress the transformed phenotype on covariate-adjusted SNP residuals. To estimate integral βQI, QUAIL avoids fitting regressions for a grid of quantile levels. Instead, it requires only fitting two linear regressions per SNP in genome-wide analysis (Fig. 1C). We present detailed derivations and technical discussions of the QUAIL framework in Methods and SI Appendix, Note.

Simulation Results.

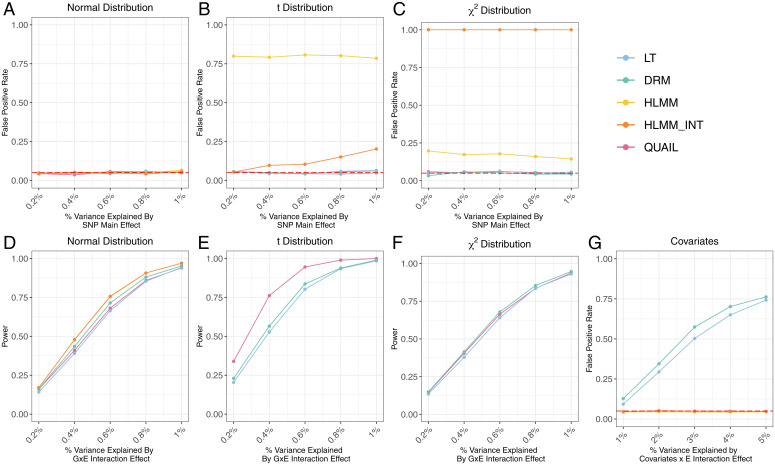

We performed simulations to compare the empirical performance of QUAIL with four other vQTL methods: DRM (13), LT (23), and HLMM with and without inverse normal transformation (16). We compared the statistical power, false-positive rate (FPR), and ability to adjust for confounding effects for these methods.

We evaluated the FPR and power of all approaches under several simulation scenarios, including three different distributions of the error term to represent various degrees of skewness and kurtosis in the phenotype and two types of SNP effects on the level and variance of the phenotype (Methods). For FPR simulations, we used a model where the SNP has effects on the level but not the variance of the phenotype. We used the phenotypic variance explained (PVE) by the SNP to control the magnitude of effects. For power simulations, we simulated quantitative trait values by using a GxE interaction model without genetic main effects (Methods), where the SNP has effects on the variance but not the mean of the phenotype. We used PVE by the GxE interaction to control the magnitude of variance effects.

Throughout all simulations, QUAIL maintained well-controlled type I error regardless of the phenotypic distribution and showed superior power when the phenotype is not normally distributed. When the phenotype follows a normal distribution, all methods control the type I error well, and HLMM is more powerful than other approaches (Fig. 2 A and D). When the phenotype is kurtotic (Fig. 2 B and E) or skewed (Fig. 2 C and F), HLMM shows inflated type I error. QUAIL, DRM, and LT are robust to the skewness and kurtosis of the phenotype. QUAIL is the most powerful method when the phenotype is kurtotic and shows similar power to DRM and LT when the phenotype is skewed.

Fig. 2.

Simulation results. Panels A–C compare the false positive rate, and panels D–F compare the statistical power of QUAIL and other vQTL methods under three different phenotypic distributions. (A and D) The phenotype follows a normal distribution. (B and E) The phenotype follows a t distribution. (C and F) The phenotype follows a χ2 distribution. (G) False positive rate of vQTL methods when confounding effect on trait variability is present.

To examine the ability to adjust for confounding effects on phenotypic variance (SI Appendix, Fig. S1), we first simulated an SNP and a correlated covariate. Next, we simulated the phenotype by using a covariate × E interaction model (Methods). We did not include the SNP in the data-generating model, so the SNP has no causal effect on the phenotype. We also did not include a main effect of the covariate to ensure that the covariate does not affect trait levels. We applied all vQTL methods to test whether the SNP is associated with the variance of the phenotype (Fig. 2G). QUAIL and HLMM maintained a well-controlled type I error rate and successfully adjusted for the covariate’s effect on variance. DRM and LT showed inflated FPR, suggesting a lack of robustness to confounding. We summarize the properties of these vQTL methods in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of key properties of vQTL methods

| Adjust for covariates’ effects on trait level and variability | Robust to nonnormal phenotype | Continuous predictor | |

|---|---|---|---|

| QUAIL | Both | Yes | Yes |

| DRM | Only on trait level | Yes | No |

| Levene’s test | Only on trait level | Yes | No |

| HLMM | Both | No | Yes |

| HLMM_INT | Both | No | Yes |

Identifying vQTLs for BMI in UK Biobank.

We applied QUAIL to perform genome-wide vQTL analysis on unrelated samples of European descent in the UK Biobank. After sample quality control (QC), 375,791 individuals with genotype data and BMI measurements were included in the analysis (Methods). We adjusted for sex, age, genotyping array, and genetic principal components (PCs) in the analysis. For comparison, we also applied DRM and HLMM to the same dataset. Both variance effect (HLMM_Var) and dispersion effect (HLMM_Disp) estimates were obtained from HLMM. We applied the inverse normal transformation to BMI before fitting HLMM. LT was omitted in this analysis because of its near identical performance compared to DRM.

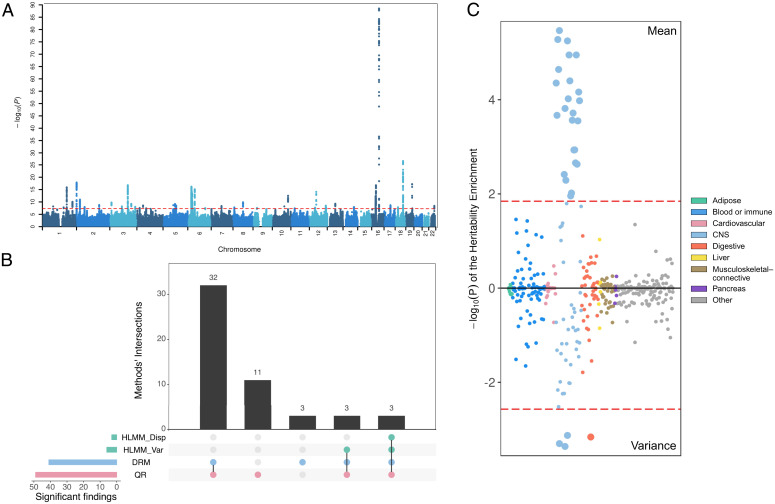

Fig. 3A shows the Manhattan plot for QUAIL vQTL. We identified 49 significant (P < 5.0e-8), approximately independent (pairwise r2 < 0.01) loci (Dataset S1). QUAIL identified more loci than other approaches (Fig. 3B). Among these 49 loci, 11 are vQTLs not identified by other approaches, and 4 are vQTLs not detected by the additive mean test (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). The quantile–quantile plot of QUAIL vQTLs hints at inflation (λGC = 1.339; SI Appendix, Fig. S3), but the intercept of linkage disequilibrium (LD) score regression is 1.003, which suggests polygenic vQTL associations rather than unadjusted confounding. Furthermore, we applied ashR (31) to estimate the fraction of nonnull associations in genome-wide vQTL statistics. We estimated that 85% of all common SNPs have nonzero association effects on the variability of BMI, which is consistent with an “omnigenic” model for BMI (6) and suggests that more loci with small variance effects are yet to be identified.

Fig. 3.

vQTL mapping of BMI in UK Biobank. (A) Manhattan plot of genome-wide vQTL analysis for BMI in UK Biobank via QUAIL. The dashed red line indicates P = 5.0e-8. (B) Number of independent significant loci (P < 5.0e-8) identified by four vQTL methods. This plot uses bars to break down the Venn diagram of overlapped loci in different vQTL methods. (C) Cell type enrichment results for BMI vQTL (Upper) and GWAS associations (Lower). Each data point represents a tissue or cell type. Different colors represent tissue categories based on Finucane et al. (30). Dashed red lines are drawn at false discovery rate = 0.05.

Previous studies have shown that heritability of BMI is mostly enriched in active genomic regions of the central nervous system (CNS) (30, 32). A recent study showed that vQTLs of BMI are significantly enriched in the gastrointestinal tract (13). We applied stratified LD score regression (33) to summary statistics of QUAIL vQTLs and GWASs of BMI. We partitioned the vQTL and GWAS associations by 205 cell-type-specific annotations (34, 35). Overall, we observed similar cell type enrichment patterns between GWAS and vQTL associations (Pearson’s correlation of LD score regression coefficient across 205 annotations = 0.78, P = 2.1e-71; Dataset S2). Both vQTL and GWAS signals showed strong enrichment in the CNS. The stomach cell type was specifically enriched for BMI vQTLs (Fig. 3C, P = 6.9e-4) but not GWAS heritability (P = 0.22), suggesting different biological mechanisms underlying the level and variability of BMI.

GxE Enrichment in vQTLs.

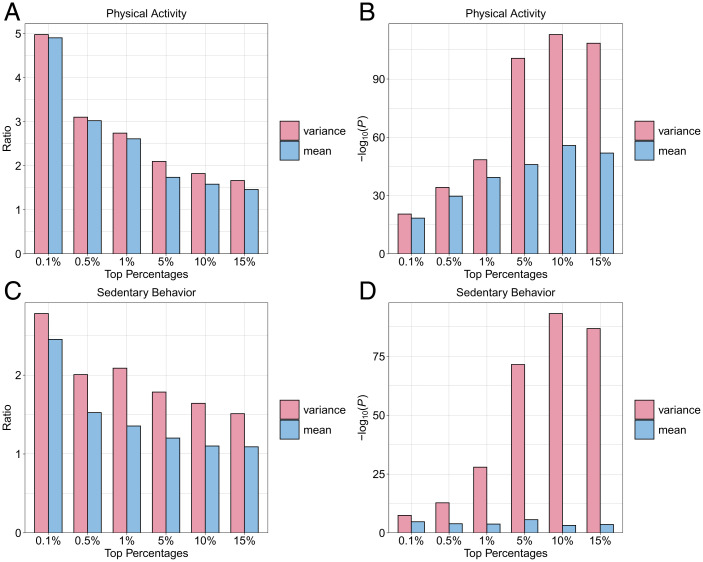

To investigate whether BMI vQTLs are enriched for GxE interactions, we performed GxE interaction tests with genome-wide SNP data and two BMI-related behavioral traits in UK Biobank: physical activity (PA) (3, 36, 37) and sedentary behavior (SB) (15, 38). We assessed enrichment for nominally significant GxE interactions (P < 0.05) in top vQTL and GWAS associations for BMI (Dataset S3 and Methods). We observed consistently and moderately stronger enrichment for GxPA and substantially stronger enrichment for GxSB interactions in top vQTL than in top GWAS associations for BMI (Fig. 4). These results show that vQTL mapping may be a more effective strategy to screen for GxE candidates than GWAS. In addition, although the fold enrichment has a decreasing trend as we consider more vQTLs in the analysis, we still observed substantial and highly significant GxE enrichment even in the top 15% of vQTLs for PA (fold enrichment = 1.66, P = 4.0e-109) and SB (fold enrichment = 1.51, P = 1.5e-87), suggesting pervasive GxE interactions between SNPs associated with BMI variability.

Fig. 4.

Enrichment for GxE interactions in top BMI vQTL and GWAS associations. Panels A and C illustrate the fold enrichment for GxE interactions in top vQTL (pink) and GWAS associations (blue). Fold enrichment ratio is defined as the actual count of significant GxE among top SNPs divided by the expected count. Panels B and D illustrate the P values for enrichment calculated from Fisher’s exact test. The environmental factors are PA for A and B and SB for C and D.

vPGS Predicts Population-Level and Within-Individual Variability of BMI.

Next, we explore whether genome-wide vQTL associations can be aggregated into concise, effective metrics to better quantify genetic effects on trait variability. Although it is straightforward to generate vPGSs by using vQTL effect sizes as SNP weights, it is a nontrivial task to evaluate the predictive performance of vPGSs. Common metrics that are used to assess PGS performance (e.g., R2) quantify the association between PGSs and trait levels and do not reflect the effect of vPGSs on trait variability. Here, we extend our quantile regression framework to continuous predictors (Methods) and use it to benchmark the performance of different vPGS models.

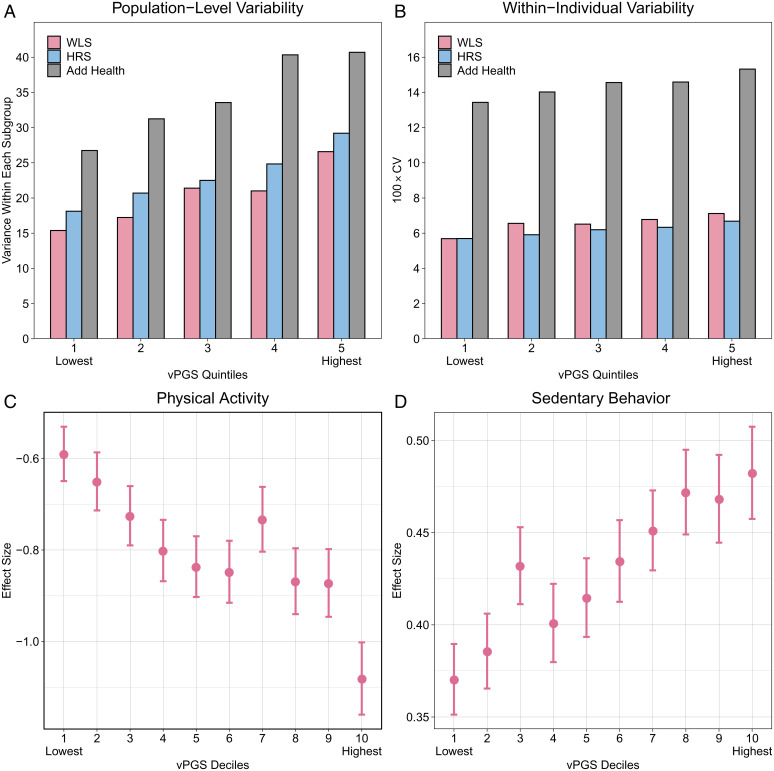

We first investigated whether vPGSs can predict the population-level BMI variability (SI Appendix, Fig. S4) by using three independent longitudinal datasets: the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (WLS), and National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health). We describe details of sample QC procedures in Methods. We used a multilevel linear growth curve model to adjust for age effects on longitudinal measurements of BMI. In each longitudinal cohort, we estimated the expected BMI of each individual across waves after removing age effects (Methods). We generated vPGSs in each cohort by using vQTL effects estimated in UK Biobank by QUAIL, HLMM_Var, HLMM_Disp, and DRM. vPGSs based on QUAIL vQTLs consistently showed the largest effect sizes and the most significant associations with BMI variability in three independent cohorts (meta-analysis beta = 0.583, P = 2.92e-48) (Table 2), followed by DRM (meta-analysis beta = 0.539, P = 6.98e-37). Compared with individuals in the lowest vPGS quintile, individuals in the highest quintile showed 61%, 52%, and 73% increases in BMI variance in HRS, Add Health, and WLS, respectively (Fig. 5A). We did two robustness checks of our results. First, we added the PGSs that predict the level of the phenotype (mPGSs) as covariates when evaluating the performance of vPGSs. vPGSs based on QUAIL vQTLs also show the best performance across these three independent cohorts (meta-analysis P = 7.66e-09) (Dataset S4). Second, we applied an alternative approach called double generalized linear model (DGLM) to evaluate the performance of vPGSs on inversed normal transformed outcome. We also obtained similar results (Methods and Dataset S5), with vPGSs based on QUAIL consistently showing the strongest associations with BMI variability (meta-analysis P = 3.56e-09).

Table 2.

Benchmarking the prediction accuracy of vPGS for population-level and within-individual BMI variability

| Population-level variability | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methods | HRS (n = 10,550) | Add Health (n = 6,717) | WLS (n = 4,694) | ||||||

| Beta | SE | P | Beta | SE | P | Beta | SE | P | |

| QUAIL | 0.520 | 0.055 | 3.07E-21 | 0.716 | 0.090 | 1.89E-15 | 0.610 | 0.077 | 2.16E-15 |

| HLMM_Var | 0.260 | 0.058 | 7.08E-6 | 0.268 | 0.094 | 0.106 | 0.292 | 0.084 | 4.93E-4 |

| HLMM_Disp | 0.098 | 0.058 | 0.094 | −0.020 | 0.094 | 0.833 | 0.156 | 0.086 | 0.068 |

| DRM | 0.507 | 0.059 | 9.97E-18 | 0.644 | 0.093 | 3.66E-12 | 0.521 | 0.082 | 2.33E-10 |

| Within-individual variability | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methods | HRS (N = 10,502) | Add Health (N = 6,706) | WLS (N = 4,471) | ||||||

| Beta | SE | P value | Beta | SE | P value | Beta | SE | P value | |

| QUAIL | 0.097 | 0.010 | 9.31E-24 | 0.092 | 0.012 | 2.60E-14 | 0.088 | 0.015 | 2.28E-9 |

| HLMM_Var | 0.048 | 0.010 | 4.26E-7 | 0.048 | 0.012 | 8.70E-5 | 0.048 | 0.015 | 0.012 |

| HLMM_Disp | 0.020 | 0.010 | 0.035 | 0.014 | 0.012 | 0.236 | 0.034 | 0.015 | 0.021 |

| DRM | 0.086 | 0.010 | 6.47E-17 | 0.087 | 0.012 | 2.07E-12 | 0.082 | 0.015 | 8.47E-8 |

The Upper and Lower tables show the results of population-level and within-individual variability, respectively. Each row represents a different vPGS approach. In the upper table, Beta denotes the estimated effect size of vPGS on the population-level BMI variability by using an evaluation method based on our quantile regression approach. In the lower table, Beta denotes the estimated effect of vPGS on the CV. SE is the SE of estimated effects. The most predictive vPGS is highlighted in boldface.

Fig. 5.

vPGS performance and application in GxE interaction. Panels A and B illustrate the prediction accuracy of vPGSs on population-level and within-individual BMI variability, respectively, in three external cohorts. (A) Each bar shows the variance of BMI within each vPGS quintile in a given cohort. (B) Each bar shows the average within-individual BMI variability quantified by the 100 × CV within each vPGS quintile. Panels C and D illustrate the vPGS–PA and vPGS–SB interactions in UK Biobank holdout samples. (C) Effect size of PA on BMI by vPGS deciles. (D) Effect size of SB on BMI by vPGS deciles.

We continued to investigate whether vPGSs estimated from cross-sectional data are also predictive of within-individual variability, which quantifies the change in a dynamic outcome (e.g., BMI) as individuals progress through the life course (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Although within-individual trait variability is a better way to quantify outcome plasticity in response to environmental changes, direct estimation of genetic associations with within-individual variability remains challenging, mostly because of limited samples in existing cohorts with genotype data and longitudinal phenotypic measurements. We leveraged the longitudinal nature of the three datasets described above and used the wave-to-wave variability to quantify the within-individual variability. More specifically, we estimated the wave-to-wave BMI variability yb using the coefficient of variation (CV; Methods). To benchmark the performance of vPGSs, we used linear regressions to quantify vPGS associations with CVs in each cohort. vPGSs based on QUAIL again showed the best predictive performance among all methods, followed by the DRM (Table 2). vPGSs based on HLMM showed substantially weaker associations with CV in all cohorts. Fig. 5B shows the average within-individual CV for samples in each vPGS quintile. We observed 17%, 14%, and 25% increases in within-individual BMI variability in the highest vPGS quintile than in the lowest quintile for HRS, Add Health, and WLS, respectively.

GxE Interaction Analysis Using vPGSs.

To further investigate the possibility of using vPGSs in GxE interaction studies, we randomly apportioned unrelated UK Biobank participants of European descent into training and testing sets with an 80–20 split. We first applied QUAIL to estimate vQTL effects of all SNPs on BMI by using samples in the training set and then used QUAIL summary statistics to generate vPGSs for samples in the testing set. We tested vPGS–PA and vPGS–SB interactions for BMI in the testing samples (Methods).

We identified significant interactions between BMI vPGSs and both PA (P = 1.1e-8) and SB (P = 1.6e-5) (Dataset S6). Both interactions remained significant after we adjusted for vPGS–covariate interaction terms in the model (39) (P = 1.7e-8 and 1.1e-7 for PA and SB, respectively; Dataset S7). We partitioned the testing sample into 10 deciles based on vPGS values and observed clear, linearly decreasing trajectories of PA effects and increasing SB effects on BMI as vPGS increases (Fig. 5 C and D).

Discussion

In this study, we introduced QUAIL, a unified statistical framework for estimating genetic effects on the variability of quantitative traits. QUAIL constructs a quantile integral phenotype that aggregates information from all quantile levels and requires fitting only two linear regressions per SNP in genome-wide analysis. Our approach directly addresses some limitations of current vQTL methods, including a lack of robustness to non-Gaussian phenotypes and confounding effects on both trait levels and trait variability. We also demonstrated that QUAIL can be extended to continuous predictors such as vPGSs. Applied to 375,791 samples in UK Biobank, QUAIL identified 49 significant vQTLs for BMI, including 11 loci that have not been previously identified. These vQTLs were significantly enriched in functional genomic regions in CNS and gastrointestinal tract, were substantially enriched for GxE interactions with BMI-related behavioral traits, and produce vPGSs that can effectively predict both population-level and within-individual BMI variability. Overall, these results hinted at distinct genetic mechanisms underlying the level and variability of BMI.

Evidence suggests that genetics, environments, and their ubiquitous interactions jointly shape human phenotypes (1). However, there has been only limited success in identifying robust GxE interactions in complex trait research. This is because detecting GxE interactions at the SNP level requires a hypothesis-free genome-wide scan, which introduces an extreme burden of multiple testing and severely reduces statistical power. Alternatively, people constructed PGSs, which are genome-wide summaries of numerous SNPs’ aggregated effects on trait levels, and used these scores as the G component in GxE studies (5–8). However, these scores do not directly quantify the susceptibility of each individual to environmental exposures and could only partially characterize the interplay between genes and environments. Our study advances the field on multiple fronts. First, our approach produces statistically robust and powerful vQTL results. These loci associated with phenotypic variability may be used as candidate SNPs in GxE research, thereby reducing the search space for possible interactions. Second, we demonstrated that the enrichment of GxE interactions is ubiquitous for vQTLs in the genome rather than concentrated only in genome-wide significant vQTLs. This finding lays the foundation for using vPGSs (which involves a large number of SNPs) in GxE studies. Third, we developed a metric to quantify the performance of variance prediction. We used it to comprehensively benchmark the predictive performance of vPGSs based on effect size from different methods in predicting both between-individual and within-individual variability of BMI in three well-powered longitudinal cohorts. Fourth, we demonstrated that vPGSs based on QUAIL effect estimates show superior predictive performance compared to existing approaches. The improved vQTLs and vPGSs, coupled with large population cohorts with deep phenotyping and sophisticated measurements on the environments, have the potential to improve prioritization and aggregation of genetic effects on both trait levels and plasticity and accelerate findings in GxE research.

Our study has some limitations. First, our method cannot be applied to binary phenotypes. Second, it is unclear whether a linear mixed model accounting for sample relatedness will be compatible with the quantile integral phenotype produced by QUAIL. Third, the use of vPGSs to predict the within-individual phenotypic variability requires some attention. In this study, we generated vPGSs by using the vQTL effects obtained from a genome-wide analysis of population-level BMI variability and demonstrated its significant association with the longitudinal, wave-to-wave BMI variability. However, for certain traits it is possible that within-individual and population-level variability are controlled by distinct biological processes and have different genetic architecture. An ultimate solution to studying the genetic basis of within-individual variability requires large GWAS samples with repeated measurements of the same outcome for each individual across time. Fourth, we demonstrated that vQTLs identified by QUAIL are enriched for GxE. With that said, it is important to recognize that GxE is sufficient but not necessary for vQTLs. Therefore, all vQTL methods (including QUAIL) will also capture other types of mechanisms that lead to differential trait variance across genotype groups, including gene–gene interactions and genetic effects on higher moments of the phenotype distribution. Therefore, findings based on vQTLs and vPGSs need to be interpreted with caution. Fifth, it is known that genetic effects on the level and the variability of BMI can be correlated (12, 13, 16). We also made similar observations in our analysis (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Young et al. (16) previously introduced the dispersion effect, which quantifies the residual genetic effect on trait variance after decorrelating association with trait levels. This approach may be overly conservative especially when SNP–trait associations are heteroskedastic. It also requires an inverse-normal transformation to the phenotype, which has been suggested to reduce the power of using vQTLs to find GxE signals (13). In the SI Appendix, Note S5, we show that the dispersion effect can also be estimated in our framework without any transformation of the phenotype. In the simulation (SI Appendix, Note S6), the QUAIL dispersion effect succeeds in picking up the variance effects that go beyond the inherent mean–variance relationship and show performance comparable to the dispersion effect of Young et al. (16) (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). In the UK Biobank BMI analysis, it substantially reduces the mean–variance relationship (SI Appendix, Fig. S4) but identifies fewer loci for BMI (SI Appendix, Figs. S7 and S8 and Dataset S8). When and how to use these dispersion effect estimates in GxE applications remains to be explored. Finally, the role of inverse-normal transformation in vQTL mapping remains to be further studied. In our simulations, under the null hypothesis that there is no genetic effect on the variance of raw phenotype, we found type I error inflation for HLMM after inverse-normal transformation. However, it is possible that inverse-normal transformation induced a real difference of phenotypic variance for the transformed phenotype across genotype groups, which HLMM correctly picked up. Therefore, interpreting different vQTL associations before and after nonlinear transformations involves some technical nuance. In practice, if getting potential false findings is a concern, estimating dispersion effects provides a useful alternative that eliminates associations introduced only by inverse-normal transformation.

QUAIL addresses several critical limitations in existing vQTL and vPGS methods and provides robust, powerful, and computationally efficient estimates for genetic effects on phenotypic variability. These methodological advances, in conjunction with increasing sample size in population cohorts with longitudinal measures of phenotypic outcomes and environments, promise exciting new developments in the near future. We believe our approach complements existing analytical strategies and will have broad applications in future studies of complex trait genetics and GxE interactions.

Methods

Statistical Model.

If a SNP G is a vQTL for trait Y, the slopes (i.e., βτ) will differ in quantile regressions based on different quantile levels τ (Fig. 1).

Here, C is a n × m matrix for covariates in the model, ατ denotes the regression coefficients for covariates, and μτ is the intercept. For a pair of quantile levels , the difference between regression coefficients (i.e., β1−τ − βτ) quantifies the effect of SNP on the variability of Y. Instead of choosing arbitrary quantile levels to define the effect size, we aggregate information across all quantile levels to define the vQTL effect:

Testing whether an SNP is associated with the variability of Y is equivalent to testing the null H0: βQI = 0. In practice, βQI can be approximated via a linear spline expansion from K quantile levels:

There are two key inference problems in this framework. First, to obtain parameter estimates which include , , and (), we can use a standard fitting approach for quantile regression (40):

where and i is the index for the ith individual in the analysis. However, to make the linear spline approximation accurate for βQI, K needs to be big. This will lead to fitting K quantile regressions for each SNP, which is computationally challenging in genome-wide analysis. Second, the SE for quantile integrated effect involves estimation of the variance–covariance matrix for and is difficult to obtain. We propose a two-step procedure in QUAIL to obtain statistically justified estimates for quantile integral effect while bypassing these computational challenges.

Step 1: Transform the phenotype into a quantile integrated rank score.

First, we estimate the intercept and covariate effects under the null model (i.e., βτ = 0) for quantile levels

where ρτ(u) = u[τ − I(u < 0)] is the loss function for quantile regression. Importantly, this step is done on the null model, so it does not need to be repeated for different SNPs in genome-wide analysis. Then, for each individual i, we construct 2K quantile rank scores:

where is a binary indicator for whether Yi is smaller than the estimated τth conditional quantile for Yi.

Then, we construct a quantile rank score for each individual:

where n is the sample size, is the SE of the regression coefficient estimate in quantile regression , and d is a random variable sampled from N(0,1). Here, we create the random variable d and calculate as described above to approximate by using estimated quantile regression coefficients while bypassing the fitting of K quantile regressions for each SNP. We show the details and rationale of this approximation in SI Appendix, Note SS2 and Figs. S9 and S10.

Finally, we construct the quantile integrated rank score for each individual i by combining Yiτ across quantile levels:

We then center the to have a mean of 0.

Step 2: Estimate the quantile integral effect.

We estimate the quantile integral effect as

where G* is the n × 1 vector of genotype residuals after covariates are regressed out. More specifically, G* = (I − PC)G, where G is the original n × 1 standardized genotype vector with mean 0 and variance 1, C is the n × m matrix for covariates, and PC = C(CTC)−1 CT is the projection onto the linear space spanned by C. Since we adjusted for covariates when obtaining the YQI and G*, we accounted for the covariates’ effects on traits level and variance when obtaining the quantile integral effect. We provide detailed derivations of this procedure in the SI Appendix, Note S2.

Under the null hypothesis that the slopes (i.e., βτ) are identical in quantile regressions based on different quantile levels τ, βQI follows a normal asymptotic distribution

where and are the residual in linear regression . We provide the derivation for the null distribution of test statistics in the SI Appendix, Note S3. In our implementation, we use a linear regression to obtain the QUAIL test statistics and P values.

In the SI Appendix, Note S1, we show that the quantile integral effects βQI have a closed-form linear relationship with the GxE effects under the common linear GxE model assumption. We also note that, more generally, we can use to quantify the vQTL effect. The quantile integral effect described above is a special case where the weights of the quantile regression coefficients are equal to 1 for quantile levels ≥0.5 and −1 for quantile levels < 0.5 (wτ = 1 when τ ≥ 0.5 and wτ = −1 when τ < 0.5). In the SI Appendix, Note S4, we introduce a more powerful vQTL test by optimally combining quantile regressions across quantile levels. Simulations show that it controls type I error well and has substantial power gain compared to existing vQTL methods (SI Appendix, Fig. S11).

Simulation Settings.

We performed extensive simulations to evaluate the type I error, statistical power, and ability to correct for confounding effect on trait variability for six vQTL methods including QUAIL by using an unweighted and optimal scheme for combining quantile regression results across various quantile levels, LT, DRM, and HLMM with and without inverse normal transformation. We used 100 quantile levels (i.e., K = 100) for QUAIL. We generated an SNP variable G coded as 0, 1, 2 from Binomial(2,f), where f is the minor allele frequency generated from a uniform distribution on [0.05, 0.5]. Environmental exposure E was generated from a standard normal distribution N(0,1). We repeated the simulation 1,000 times and calculated FPR and power as the proportion of simulations where the null hypothesis was rejected at P < 0.05.

For FPR simulations, we used a model where the SNP has effects on the level but not the variance of the phenotype. We simulated a phenotype for 200,000 individuals according to the model , where yi is the simulated phenotype, is an error term with mean and variance for the ith individual. To simulate the error term with different levels of skewness and kurtosis, we sampled from three different distributions: standard normal distribution N(0,1), t distribution with df = 3, and χ2 distribution with df = 6. Regression coefficients were selected such that the proportion of total PVE by genotype, defined as Var(βgGi)/Var(yi), ranged between 0.2% and 1%. was set to be 1 − Var(βgGi)/Var(yi) so that Var(yi) = 1.

For power simulation, we simulated the phenotype such that the SNP has a variance effect only on the phenotype. This variance effect is reflected in the interaction term for the SNP and environmental exposures. We simulated a phenotype for 200,000 individuals according to the model , where yi is the simulated phenotype, and is an error term with mean 0 and variance for the ith individual. We also simulated error terms from three different distributions as described above. We selected the regression coefficients such that the proportion of total PVE by the GxE interaction, that is, Var(βGEGiEi)/Var(yi), ranged between 0.2% and 1%. We set .

To assess different methods’ robustness to confounding effect on trait variability, we simulated the phenotype such that the SNP has no effect and a covariate has variance effect on the phenotype. This covariate was generated from Bernoulli(p), where p varies with each individual’s genotype value (i.e., p = 0.2 for individuals with G = 0, p = 0.5 when G = 1, and p = 0.8 when G = 2. The covariate’s variance effect is reflected in the interaction term for the covariate and environmental exposures. We simulated a phenotype for 200,000 individuals according to the model , where yi is the simulated phenotype, Ci is the covariate, and is an error term that follows for the ith individual. We selected the regression coefficients such that the proportion of total PVE by the covariate × E interaction, Var(βCECiEi)/Var(yi), ranged between 1% and 5%. We also set to rescale the variance of yi to be 1.

UK Biobank Data Processing.

The QC procedure for genetic data in the UK Biobank has been described elsewhere (41). We analyzed UK Biobank samples with European ancestry inferred from genetic PCs (data field 22006). Participants who are recommended by UK Biobank to be excluded (data field 22010), those with conflicting genetically inferred (data field 22001) and self-reported sex (data field 31), and those who withdrew from the study were excluded from the analyses. We also removed related individuals identified by software KING (Kinship-based INference for Gwas) (42) and retained 377,509 unrelated individuals with European descent.

Genome-Wide vQTL Mapping for BMI.

Following previous work on genome-wide analysis in UK Biobank (43), we used year of birth (data field 34), sex (data field 31), genotyping array, and top 12 PCs computed in flashPCA2 (44) on the analytical sample as covariates for both trait level and variability. We included only SNPs with a minor allele frequency >1% and missingness <1% in the analysis.

We conducted genome-wide vQTL analysis via four methods: QUAIL, DRM, HLMM_Var, and HLMM_Disp. For QUAIL, we transformed the BMI into a quantile integrated rank score, obtained SNP residual values by regressing each SNP on covariates, and estimated the vQTL effect by regressing the quantile integrated rank score on SNP residuals. For DRM, we first fit a linear model between BMI and covariates and calculated the BMI residual. Then, we applied DRM to quantify the effect of each SNP on BMI residual. For HLMM, we first applied an inverse normal transformation to BMI. Then, we fit HLMM to obtain the additive and log-linear variance effects (i.e., HLMM_Var). Next, we estimated the HLMM dispersion effect (i.e., HLMM_Disp) by using the additive and log-linear variance effects as described previously (16).

We set the genome-wide significance threshold at 5.0e-8. To determine the number of independent significant vQTLs, we clumped the summary statistics for each method in PLINK2 (45) (–clump option with parameters –clump-p1 5.0e-8 –clump-p2 5.0e-8 –clump-r2 0.01 and –clump-kb 5000) by using the analytic sample in UK Biobank as the LD reference panel. To visualize the results, we generated the Manhattan plot and quantile–quantile plot with the ramwas (46) package in R.

We also conducted a GWAS for BMI by using Hail (47) on the same data used in the vQTL analysis. We included year of birth, sex, genotyping array, and top 12 PCs computed in flashPCA2 (44) on the analytical sample as covariates. LD clumping and visualization were performed similarly as described above.

Additionally, we used the estimated intercept from LD score regression (48) to quantify the level of unadjusted confounding in genome-wide vQTL analysis. We used ashR (31) on the full set of SNPs to estimate the proportion of nonnull vQTL associations.

Cell-Type Heritability Enrichment Analysis.

We used stratified LD score regression (33) to perform cell type enrichment analyses with gene expression data by using the “Multi_tissue_gene_expr” (including data from GTEx and Franke laboratory) flag and default settings. We only included non-MHC (Major histocompatibility complex) HapMap3 SNPs for LD score regression analysis. Cell-type enrichment P values across 205 functional annotations were adjusted via the Benjamini–Hochberg method for false discovery rate (49).

Gene–Environment Interaction Enrichment Analysis.

We performed GxE interaction tests by using genome-wide SNP data and two BMI-related behavioral traits (i.e., PA and SB) in UK Biobank. Details about the construction of PA and SB variables can be found elsewhere (13, 15). For PA, we assigned a three-level categorical score (low, medium, and high) based on the short form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire guideline for each individual. We defined SB as an integer by using the combined time (hours) spent driving, using a computer, and watching television.

To assess the enrichment for GxE effects in top vQTLs, we first clumped the QUAIL summary statistics in PLINK2 (–clump option with parameters –clump-p1 1 –clump-p2 1 –clump-r2 0.1 and –clump-kb 1000) by using the CEU samples (Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry) in the 1000 Genome Project Phase III cohort as the LD reference panel. Next, we performed a GxE analysis to test the interaction between SNPs in the clumped summary statistics and PA and SB based on the model:

where Yi is BMI, Gi is the SNP genotype, and Ei is the environmental factor for the ith individual. We defined nominally significant GxE by using a P value cutoff of 0.05. We also defined vQTL as the top 0.1%, 0.5%, 1%, 5%, 10%, and 15% of SNPs ordered by their QUAIL P values in the clumped summary statistics. The fold enrichment was calculated as the actual count of significant GxE between vQTLs divided by the expected count. We used Fisher’s exact test to test the enrichment.

For comparison, we also performed enrichment analysis for GxE interaction in top GWAS associations via the same analytical procedure described above.

Predicting Population-Level Trait Variability.

To benchmark the predictive power of vPGSs, we used data from three independent cohorts: HRS, Add Health, and WLS. We included only individuals of European ancestry in the analysis. The sample sizes were 10,550, 6,717, and 4,694 for HRS, Add Health, and WLS respectively.

To compute vPGSs, we first clumped each set of summary statistics in PLINK2 (–clump option with parameters –clump-p1 1 –clump-p2 1 –clump-r2 0.1 and –clump-kb 1000) by using the CEU samples in the 1000 Genome Project Phase III cohort as the LD reference panel. Then, we computed vPGSs in PRSice-2 (50) without P value filtering. We calculated four vPGSs based on different vQTL methods: QUAIL, DRM, HLMM_Var, and HLMM_Disp.

To quantify the performance of vPGSs in predicting population-level variability, we first fit a multilevel linear growth curve model on BMI and age in each cohort:

where Yit and Ageit denote the BMI and age of respondent i at time point t, respectively (i = 1, . . ., n and t = 1, . . ., Ti), and β0i is assumed to be normally distributed. We included linear and quadratic terms for age to reflect the nonlinear age-dependent trajectory of BMI. The estimated individual intercept (i.e., ) represents the expected BMI after the age effect is removed. We denote it as BMI-adj and use it as the trait value for the further analysis described below.

We extended our quantile regression framework to assess vPGS performance with two modifications because of the eased computational burden. First, we regressed the phenotype on the vPGS and use the residual to construct the rank score as described before. Second, we performed a standard quantile regression and used the kernel-based sandwich approach (51) to obtain the SE of the estimated quantile regression coefficient for vPGS, SE(βτ). We used the same approach to construct the quantile integrated rank score YQI for each individual. The effect size of vPGS can be quantified as

where vPGS* is the n-dimensional vPGS residual vector after covariates are regressed out. Here, original vPGS is standardized to have mean 0 and variance 1. We used this quantile integral effect to quantify the predictive performance of vPGSs on the population-level variability. We adjusted sex and top 10 PCs in the analysis of each cohort. We repeated the analysis by using the model above with mPGSs as additional covariates. We constructed the mPGSs by using the GWAS summary statistics of BMI in this article and same procedure as computing the vPGSs described above. We also extended the DGLM (14, 26), the method implemented in HLMM, as an alternative approach to evaluate vPGS performance. The DGLM takes the form of

where BMIi denotes the inverse normal-transformed BMI-adj of individual i, Gi is the vPGS of individual i, and Ci is the vector of covariates including sex and top 10 PCs. Here, α1 quantifies the effect of vPGSs on the variability of BMI and is the parameter of interest in this analysis. We fitted DGLM in the dglm (52) packages in R. We used the inverse variance-weighted meta-analysis method to combine the effect size estimates in these three cohorts.

To visualize the predictive performance of vPGSs in predicting population-level variability, we divided samples into quintiles according to their vPGS values and compared the variance of BMI-adj across quintiles in each cohort.

Predicting Within-Individual Trait Variability.

We used the same three external datasets (i.e., WLS, HRS, and Add Health) to benchmark the performance in predicting within-individual BMI variability. We applied the same QC procedure described above except that we included only individuals with reported BMI in at least two waves.

We quantified the wave-to-wave BMI variability by using CV (53), defined as:

where SDi is the BMI SD of the ith individual across waves and μi is the individual mean of BMI across waves. We calculated CV for each individual based on all of the participant’s BMI measurements across waves. Then, we used linear regression to quantify the predictive performance of vPGS on the within-individual variability. We regressed CV on vPGS in each cohort and included sex, mean age across waves, and top 10 PCs as covariates. To visualize the results, we divided samples from each cohort into quintiles according to their vPGS values and compared the average CV across quintiles.

Gene–Environment Interaction Analysis by Using vPGS.

To test GxE interactions by using vPGS, we randomly apportioned unrelated UK Biobank participants of European descent (n = 375,791) into training (n = 300,633) and testing sets (n = 75,158), with an 80–20 split. We applied QUAIL to estimate the effect of each SNP on BMI variability by using samples in the training set while controlling for year of birth, sex, genotyping array, and top 12 PCs computed in flashPCA2 (44) on the analytical sample as covariates.

Next, we used weights obtained in the training set to construct vPGSs for samples in the testing set. To compute vPGSs, we first clumped the summary statistics in PLINK2 (–clump option with parameters –clump-p1 1 –clump-p2 1 –clump-r2 0.1 and –clump-kb 1000) by using the CEU samples in the 1000 Genome Project Phase III cohort as the LD reference panel. Then, we computed vPGS in PRSice-2 without P value filtering.

We tested vPGSxE effects on BMI by fitting the following model:

where Yi is BMI, vPGSi is the standardized vPGS with mean 0 and variance 1, and Ei is the environmental factor (i.e., PA or SB) for the ith individual. We adjusted for year of birth, sex, genotyping array, and top 12 PCs. To check the robustness of our results, we repeated our vPGSxE analysis on BMI by using the model above with vPGS-Sex and vPGS-Year of birth interaction terms as additional covariates.

To visualize the interaction, we divided samples into 10 deciles based on their vPGS values and compared estimates of the environmental factor on BMI across vPGS deciles.

URLs.

UK Biobank (https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/); HRS (https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/about); Add Health (https://addhealth.cpc.unc.edu/); WLS (https://www.ssc.wisc.edu/wlsresearch/); HLMM (https://hlmm.readthedocs.io/en/latest/); DRM (https://github.com/drewmard/DRM); ashR (https://github.com/stephens999/ashr); dglm (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/dglm/); KING (https://www.kingrelatedness.com/).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the pilot grant of the Center for Demography of Health and Aging at University of Wisconsin–Madison (P30 AG017266). We also acknowledge research support from the University of Wisconsin–Madison Office of the Chancellor and the Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education with funding from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation. We thank faculties and students involved in the Initiative in Social Genomics at the University of Wisconsin–Madison for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2212959119/-/DCSupplemental.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

The QUAIL software package, and anonymized vQTL GWAS summary statistics and software data are publicly available on GitHub (https://github.com/qlu-lab/QUAIL) (54). Summary statistics of QUAIL vQTL analysis for BMI are available at (http://qlu-lab.org/data.html) (55).

References

- 1.Manolio T. A., et al. , Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature 461, 747–753 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yengo L., et al. ; GIANT Consortium, Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for height and body mass index in ∼700000 individuals of European ancestry. Hum. Mol. Genet. 27, 3641–3649 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young A. I., Wauthier F., Donnelly P., Multiple novel gene-by-environment interactions modify the effect of FTO variants on body mass index. Nat. Commun. 7, 12724 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aschard H., et al. , Challenges and opportunities in genome-wide environmental interaction (GWEI) studies. Hum. Genet. 131, 1591–1613 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belsky D. W., et al. , Genetic analysis of social-class mobility in five longitudinal studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E7275–E7284 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyle E. A., Li Y. I., Pritchard J. K., An expanded view of complex traits: From polygenic to omnigenic. Cell 169, 1177–1186 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fletcher J. M., Lu Q., Health policy and genetic endowments: Understanding sources of response to Minimum Legal Drinking Age laws. Health Econ. 30, 194–203 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmitz L., Conley D., The long-term consequences of Vietnam-era conscription and genotype on smoking behavior and health. Behav. Genet. 46, 43–58 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barcellos S. H., Carvalho L. S., Turley P., Education can reduce health differences related to genetic risk of obesity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E9765–E9772 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill W. G., Mulder H. A., Genetic analysis of environmental variation. Genet. Res. 92, 381–395 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ivarsdottir E. V., et al. , Effect of sequence variants on variance in glucose levels predicts type 2 diabetes risk and accounts for heritability. Nat. Genet. 49, 1398–1402 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang J., et al. , FTO genotype is associated with phenotypic variability of body mass index. Nature 490, 267–272 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marderstein A. R., et al. , Leveraging phenotypic variability to identify genetic interactions in human phenotypes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 108, 49–67 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rönnegård L., Valdar W., Detecting major genetic loci controlling phenotypic variability in experimental crosses. Genetics 188, 435–447 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang H., et al. , Genotype-by-environment interactions inferred from genetic effects on phenotypic variability in the UK Biobank. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw3538 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Young A. I., Wauthier F. L., Donnelly P., Identifying loci affecting trait variability and detecting interactions in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 50, 1608–1614 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao Z., et al. , PUMAS: fine-tuning polygenic risk scores with GWAS summary statistics. Genome biol. 22, 1–19 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Johnson R., Sotoudeh R., Conley D., Polygenic Scores for Plasticity: A New Tool for Studying Gene–Environment Interplay. Demography 59, 1045–1070 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Conley D., et al. , A sibling method for identifying vQTLs. PLoS One 13, e0194541 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmitz L. L., Goodwin J., Miao J., Lu Q., Conley D., The impact of late-career job loss and genetic risk on body mass index: Evidence from variance polygenic scores. Sci. Rep. 11, 7647 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rönnegård L., Valdar W., Recent developments in statistical methods for detecting genetic loci affecting phenotypic variability. BMC Genet. 13, 63 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Struchalin M. V., Dehghan A., Witteman J. C., van Duijn C., Aulchenko Y. S., Variance heterogeneity analysis for detection of potentially interacting genetic loci: Method and its limitations. BMC Genet. 11, 92 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levene H., “Robust tests for equality of variances” in Contributions to Probability and Statistics. Essays in Honor of Harold Hotelling, I. Olkin et al., Eds. (Stanford University Press, 1961), pp. 278–292. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Musharoff S., et al. , Existence and implications of population variance structure. bioRxiv [Preprint] (2018). https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/439661v1.full. Accessed 20 October 2018.

- 25.Sofer T., et al. , Population stratification at the phenotypic variance level and implication for the analysis of whole genome sequencing data from multiple studies. bioRxiv [Preprint] (2020). https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.03.03.973420v1.full. Accessed 15 March 2020.

- 26.Smyth G. K., Generalized linear models with varying dispersion. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 51, 47–60 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koenker R., Hallock K. F., Quantile regression. J. Econ. Perspect. 15, 143–156 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abadi A., et al. , Penetrance of polygenic obesity susceptibility loci across the body mass index distribution. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 101, 925–938 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang T., Ionita-Laza I., Wei Y., Integrated Quantile RAnk Test (iQRAT) for gene-level associations. Ann. Appl. Stat. 16, 1422–1444 (2022).

- 30.Finucane H. K., et al. ; Brainstorm Consortium, Heritability enrichment of specifically expressed genes identifies disease-relevant tissues and cell types. Nat. Genet. 50, 621–629 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stephens M., False discovery rates: A new deal. Biostatistics 18, 275–294 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu Q., Powles R. L., Wang Q., He B. J., Zhao H., Integrative tissue-specific functional annotations in the human genome provide novel insights on many complex traits and improve signal prioritization in genome wide association studies. PLoS Genet. 12, e1005947 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finucane H. K., et al. ; ReproGen Consortium; Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium; RACI Consortium, Partitioning heritability by functional annotation using genome-wide association summary statistics. Nat. Genet. 47, 1228–1235 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Battle A., Brown C. D., Engelhardt B. E., Montgomery S. B.; GTEx Consortium; Laboratory, Data Analysis &Coordinating Center (LDACC)—Analysis Working Group; Statistical Methods groups—Analysis Working Group; Enhancing GTEx (eGTEx) groups; NIH Common Fund; NIH/NCI; NIH/NHGRI; NIH/NIMH; NIH/NIDA; Biospecimen Collection Source Site—NDRI; Biospecimen Collection Source Site—RPCI; Biospecimen Core Resource—VARI; Brain Bank Repository—University of Miami Brain Endowment Bank; Leidos Biomedical—Project Management; ELSI Study; Genome Browser Data Integration &Visualization—EBI; Genome Browser Data Integration &Visualization—UCSC Genomics Institute, University of California Santa Cruz; Lead analysts; Laboratory, Data Analysis &Coordinating Center (LDACC); NIH program management; Biospecimen collection; Pathology; eQTL manuscript working group, Genetic effects on gene expression across human tissues. Nature 550, 204–213 (2017).29022597 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hunt K. A., et al. , Newly identified genetic risk variants for celiac disease related to the immune response. Nat. Genet. 40, 395–402 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kilpeläinen T. O., et al. , Physical activity attenuates the influence of FTO variants on obesity risk: A meta-analysis of 218,166 adults and 19,268 children. PLoS Med. 8, e1001116 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahmad S., et al. ; InterAct Consortium; DIRECT Consortium, Gene × physical activity interactions in obesity: Combined analysis of 111,421 individuals of European ancestry. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003607 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martínez-González M. Á., Martinez J. A., Hu F., Gibney M., Kearney J., Physical inactivity, sedentary lifestyle and obesity in the European Union. Int. J. Obes. 23, 1192–1201 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keller M. C., Gene × environment interaction studies have not properly controlled for potential confounders: the problem and the (simple) solution. Biol. Psychiatry 75, 18–24 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koenker R., Quantile Regression (Cambridge University Press, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bycroft C., et al. , The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature 562, 203–209 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manichaikul A., et al. , Robust relationship inference in genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics 26, 2867–2873 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jansen I. E., et al. , Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies new loci and functional pathways influencing Alzheimer’s disease risk. Nat. Genet. 51, 404–413 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abraham G., Qiu Y., Inouye M., FlashPCA2: Principal component analysis of Biobank-scale genotype datasets. Bioinformatics 33, 2776–2778 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Purcell S., et al. , PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 559–575 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shabalin A. A., et al. , RaMWAS: Fast methylome-wide association study pipeline for enrichment platforms. Bioinformatics 34, 2283–2285 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hail Team, Hail 0.2.13-81ab564db2b4. https://github.com/hail-is/hail/releases/tag/0.2.13. Accessed 12 October 2020.

- 48.Bulik-Sullivan B. K., et al. ; Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, LD Score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 47, 291–295 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y., Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 57, 289–300 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Choi S. W., O’Reilly P. F., PRSice-2: Polygenic Risk Score software for biobank-scale data. Gigascience 8, giz082 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Powell J. L., Estimation of Monotonic Regression Models Under Quantile Restrictions (Wisconsin Madison-Social Systems, 1988). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rönnegård L., Felleki M., Fikse F., Mulder H. A., Strandberg E., Genetic heterogeneity of residual variance-estimation of variance components using double hierarchical generalized linear models. Genet. Sel. 42, 8 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Everitt B., Skrondal A., The Cambridge Dictionary of Statistics (Cambridge University Press Cambridge, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 54.J. Miao et al., QUAIL: a unified framework to estimate genetic effects on the variance of quantitative traits. GitHub. https://github.com/qlu-lab/QUAIL. Deposited 13 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lu Laboratory, Statistical Genetics & Genome Information. University of Wisconsin-Madison. http://qlu-lab.org/data.html. Accessed 12 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The QUAIL software package, and anonymized vQTL GWAS summary statistics and software data are publicly available on GitHub (https://github.com/qlu-lab/QUAIL) (54). Summary statistics of QUAIL vQTL analysis for BMI are available at (http://qlu-lab.org/data.html) (55).