Abstract

Purpose of Review

Cognitive impairment is associated with obesity, sarcopenia, and osteoporosis. However, no critical appraisal of the literature on the relationship between musculoskeletal deficits and cognitive impairment, focusing on the epidemiological evidence and biological mechanisms, has been published to date. Herein, we critically evaluate the literature published over the past 3 years, emphasizing interesting and important new findings, and provide an outline of future directions that will improve our understanding of the connections between the brain and the musculoskeletal system.

Recent Findings

Recent literature suggests that musculoskeletal deficits and cognitive impairment share pathophysiological pathways and risk factors. Cytokines and hormones affect both the brain and the musculoskeletal system; yet, lack of unified definitions and standards makes it difficult to compare studies.

Summary

Interventions designed to improve musculoskeletal health are plausible means of preventing or slowing cognitive impairment. We highlight several musculoskeletal health interventions that show potential in this regard.

Keywords: Cognition, Bone, Muscle, Musculoskeletal system, Nervous system

Introduction

Musculoskeletal and cognitive function declines often occur at the same time, for example with aging or in individuals with dementia [1–3]. Cognition is an intellectual or mental process via which organisms obtain knowledge and cognitive impairment (diminished intellectual and/or mental functioning) is associated with obesity [4]. Further, brain function and body composition are linked [4–7]. In particular, obesity in middle age has been linked with increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [8, 9]. However, whether cognitive and musculoskeletal abnormalities share common mechanistic bases or they appear at the same time due to common risk factors is not completed clear and is a subject of continuous research.

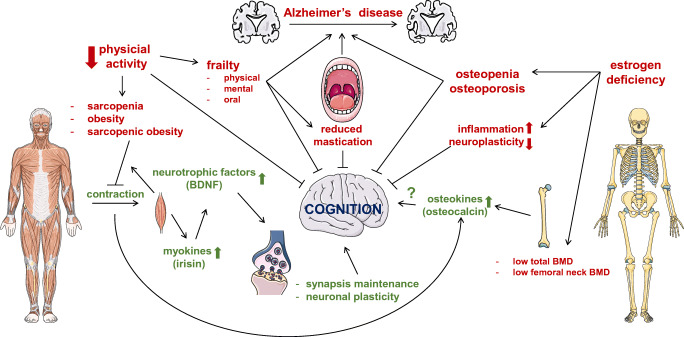

Efforts to establish the mechanistic links between brain and musculoskeletal function have been undertaken. For example, studies showed that metabolically active tissues such as skeletal muscle release neurotrophic factors that regulate synapses in the brain [10]. One of such factors is the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), released during skeletal muscle contraction [11], and which absence has been linked to neurodegenerative processes [12]. Similarly, serotonin controls bone mass accrual by acting on its receptor in the receptors on ventromedial hypothalamic neurons [13]. Further, several factors released by osteoblasts and osteocytes in bone, including osteocalcin, sclerostin, and fibroblast growth factor 23, can cross the blood–brain barrier and alter brain function [14]. Herein, we review the current literature on brain-musculoskeletal system interactions (summarized in Figure 1) and propose future directions that might help resolve controversies in the field.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the nervous-musculoskeletal systems crosstalk. The figure depicts some of the mechanisms by which this crosstalk occurs. The balance among factors produced by the brain, bone, and skeletal muscle is required not only for each tissue homeostasis, but also for the health of other tissues through the production of hormones, cytokines, and mechanical forces. Further research is needed to understand the physiological, cellular, and molecular mechanisms behind the link between the cognition and the musculoskeletal system in health and disease. BDNF, brain derived neurotrophic factor; BMD, bone mineral density

Musculoskeletal System and Cognition

Mounting evidence suggests that physical activity is connected to cognitive development and brain evolution, whereas lifestyles and habits characterized by prolonged stasis (e.g., office work, sedentary entertainment) are associated with increased risk for cognitive impairment [15, 16]. The effects on musculoskeletal conditions and cognitive status of 2-h prolonged sitting [17] and standing [18] during office work were evaluated in an adult population in Australia. Prolonged sitting and standing were associated with increased whole-body musculoskeletal discomfort based on the Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire [17, 18], with detrimental effects on mental status and attention reaction responses [17, 18]. Contrasting results were found for problem-solving skills, assessed with the Ruff Figural Fluency Test, showing improvements during prolonged sitting, but the opposite effect during prolonged standing [17, 18]. Moreover, prolonged standing combined with a foot movement exercise further decreased problem-solving skills while focused musculoskeletal discomfort to the foot and ankle regions [19]. Other studies suggest that prolonged standing decreases cognitive performance during complex tasks [20]. Therefore, moving from sitting to standing while working, involving minimal physical activity, must be evaluated further to understand the mechanisms behind the relationship between musculoskeletal health and cognitive status.

The effects of intermittent physical activity were assessed in a study involving 8 middle-age men and 3 women, by determining the effect of three different disruptive activities (social interaction, functional resistance training, and walking) on cognitive performance and salivary cortisol levels (as a marker of stress) during 3-h sitting [21]. Using a memory task evaluation and the numerical n-back test method, this study found that walking improves cognitive performance. Interestingly, the study also determined a reduction in salivary cortisol levels when participants were exposed to any of the three disruptive activities. The n-back test is useful to assess working memory, since it allows the participants to recall the last in a series of events [22]. Another study of healthy adults 65 years and older showed improved performance on memory task when the letter n-back test was assessed 15 and 45 min after stationary bicycle exercise [23]. Further, following exercise, activity in the parietal brain region was found higher than that of the frontal region, as determined by brain hemoglobin concentration [23]. Further, a positive relationship between the intensity of daily physical activities (from sedentary to highly active) and bone mass was found in adults aged over 70 years, with sex-dependent differences in certain brain regions [24]. Additionally, the later study revealed that women with bone fracture history had been less active earlier in life than women without fractures [24].

Musculoskeletal and dental conditions affecting mastication are also associated with negative effects on cognition. Thus, studies in Japanese individuals 65 years and older show an association between either having less than 20 functional teeth and reduced occlusal force or being fully edentulous and cognitive impairments [25, 26]. Furthermore, a systematic review identified a study linking reduced cognitive performance (based on the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE)) with impaired masticatory function in AD patients compared to an age-matched healthy population [27]. Nonetheless, the relationship between mastication and cognitive impairment is not fully understood [28].

Skeletal Muscle and Cognition

Sarcopenia and Cognitive Impairment

Sarcopenia is generally defined as age-related progressive loss of muscle mass and function, although the working definition varies among different groups [29, 30]. Thus, several operational definitions of sarcopenia are in use, including those provided by the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People [31], the United States Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH) [32], the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia (AWGS) [33], and the Sarcopenia Definition and Outcomes Consortium [34]. Therefore, the prevalence of sarcopenia reported in the literature varies substantially within and across geographic areas, due to differences in the criteria and cutoff points applied [35, 36]. Researchers conducting the Geelong Osteoporosis Study (GOS) [37] described the consequences of applying different criteria and cutoff points (international and population-specific) in a homogeneous sample for prevalence estimates for the Australian population [38, 39]. The main finding was that, across all the definitions, the prevalence of sarcopenia increased with increasing age; however, the varied criteria and cutoff points resulted in inconsistent case ascertainment. The GOS explored the relationship between several muscle parameters and overall cognitive function, specific cognitive domains, and cognitive impairment among men [40]. The findings suggested that muscle parameters, especially muscle function [41••], muscle quality [42•], and muscle density [43••], are associated with certain cognitive domains (including working memory, attention, and information processing speed) independent of age, physical activity levels, education, and lifestyle factors. However, these associations were not detected for all the cognitive domains tested. Similar results on the association between dynapenia (age-associated muscle strength loss not caused by neurologic or muscular diseases) and low cognition were reported in female GOS participants [44•].

In summary, inconsistencies in studies associating muscle health with cognition could be due to differences in criteria used to define sarcopenia, sarcopenic obesity, and cognitive deficits. Evidence for mechanisms linking muscle health with certain brain functions also remain unclear.

Sarcopenic Obesity and Cognitive Impairment

Sarcopenic obesity is a condition characterized by concurrent high adiposity levels and low muscle mass and function with advanced age [45]. The association between sarcopenic obesity and cognition was assessed in 353 community-recruited USA participants aged 40 years and over [46]. Body composition was measured by bioelectrical impedance analysis. Obesity was determined by body mass index (BMI) and fat percentage. Global cognition was assessed using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment. Specific cognitive domains in verbal fluency and mental flexibility were assessed using the animal naming test (participants are asked to name as many animals as they could within one minute). Visual search speed, scanning, and processing speed were assessed using Trail Making A. The authors recommended that sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity should be regarded as clinical indicators of cognitive impairment, listing potential mechanisms that explain sarcopenic obesity and cognitive deficits association, including low-grade chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and insulin resistance; however, no biomarker data was included in the report.

The association between sarcopenic obesity and cognitive impairment was examined in 948 community-based Chinese participants aged 60 years and over (51% female) [47]. Body composition was measured by bioelectrical impedance analysis and cognition by MMSE. Sarcopenia was defined using the AWGS criteria, and obesity was determined by body fat percentage (fat mass/weight). Six percent of participants were identified as sarcopenic obese. This study reported an independent association between sarcopenic obesity and cognitive impairment and proposed that the mechanisms underlying the link between muscle, fat, and cognition were inflammation, insulin resistance, and decreased growth hormone secretion, but these hypotheses were not tested.

The association between sarcopenic obesity and cognitive performance was also examined in 1235 Singaporean patients (~48% female) aged 45 years and over with type 2 diabetes; all were attending diabetes care [48]. Body composition was assessed using bioelectrical impedance analysis, and the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status and MMSE were applied for assessing cognition. This study identified an association between sarcopenic obesity and poor cognitive performance, particularly in the domains of memory and language. The authors acknowledged that the mechanisms underlying these dual deficits in brain and body were not fully understood; however, it is likely that in these patients, abnormal levels of insulin affect amyloid β metabolism, which controls neuronal function.

Further, in a longitudinal, population-based study in the USA, the association between sarcopenic obesity and incident cognitive function was determined in 5822 participants (~56% female) aged 65 years old and over, without cognitive impairment at baseline [49]. They adopted the FNIH definition of sarcopenia, and defined obesity by BMI. Cognition was assessed using AD-8 score or immediate/delayed recall, orientation, clock-draw test, or date/person recall. At baseline, 12.9% of subjects were identified as having sarcopenic obesity; 21.2% were identified with cognitive impairment at follow-up. Sarcopenia obesity and sarcopenia alone were significantly associated with higher risk of cognitive impairment. On the other hand, a study including 542 participants 21–90 years recruited from the Chinese community produced contrasting findings [50]. The researchers obtained body composition data using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) and defined obesity as the upper two quintiles of fat mass index. They employed a sarcopenia definition based on the 2019 AWGS criteria. Cognitive impairment was determined using the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status. This battery included 12 tests to assess immediate memory, visuospatial/constructional abilities, language, attention, and delayed memory. Sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity were not associated with cognitive impairment, but obesity alone and muscle function (grip strength or gait speed) were. The authors speculated that insulin resistance underpins the association.

Bone and Cognition

Osteoporosis is characterized by low bone mass, and is defined by the number of standard deviations a patient’s BMD differs from the average of a population of the same age and sex (Z-score) or from a young normal reference value (T-score). T-scores lower than −2.5 standard deviations are indicative of osteoporosis, whereas values between −1.0 and −2.5 lead to a diagnosis of osteopenia, a milder condition [51], as defined by the Word Health Organization [52]. Low BMD increases risk for fracture [53] and has been associated with high morbidity and mortality [54], in particular among older individuals.

Several epidemiologic studies have looked at the potential correlation between low bone mass and cognitive decline. The PRESENT project 2018 [55] examined the association between BMD and cognition in 650 Koreans without stroke or dementia, aged 50 years or older. MMSE was used to assess cognition in 197 participants with osteopenia and 154 with osteoporosis. As expected, osteoporosis was more common among women than among men, but low BMD was associated with cognitive impairment in both genders, although the association appeared stronger in women for both osteopenia and osteoporosis. The authors listed possible common mechanisms underlying this association, including estrogen deficiency. Postmenopausal estrogen deficiency leads to an initial increase in bone formation and resorption, with bone loss resulting from remodeling imbalance. In the brain, estrogen reduces inflammation and promotes neuroplasticity in the brain processes crucial for learning and memory [56].

Similarly, a systematic literature review and meta-analysis reported that both lower BMD and lower femoral neck BMD were linked to increased risk of AD and gender seems to play a role in this association [57]. Further studies, under the Bushehr Elderly Health Program [58], examined gender-specific cross-sectional associations between osteoporosis and cognitive impairment in a community-dwelling sample of 1508 Iranian participants aged 60 years and over (~49% female). BMD was assessed using DXA; osteoporosis and osteopenia were identified by DXA-derived BMD at any skeletal site. Cognition was assessed using Mini-Cog and categorical verbal fluency tests. Five hundred and ninety-eight participants had osteoporosis and 677 had cognitive impairment. Osteoporosis at the spine and total hip was associated with increased risk of cognitive impairment in women and, conversely, cognitive impairment was associated with increased risk of spinal osteopenia/osteoporosis, total hip osteoporosis, and whole-body osteoporosis in women. These associations were not found in men. The authors propose that gender differences identified in this study are due to changes in estrogen levels in women during their lifespan and suggested that hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis dysregulation reflected the dual decline in bone health and cognitive function [58].

The associations between osteoporosis and cognitive function were also examined in 260 hospitalized Korean patients (59% female) recovering from acute stroke [59]. Osteoporosis was defined by T-score ≤−2.5 or low BMD in the femoral neck or lumbar spine, and cognitive impairment was assessed by the Korean MMSE. Patients with osteoporosis before and after the recovery phase had higher prevalence of cognitive impairment. In addition, women who experienced significant cognitive decline in the first 5 years after stroke had increased risk of fracture over the next decade. None of the associations identified in women was found in men. The authors recommended further investigation of gender-specific biological mechanisms that might underlie these associations.

Using the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMos), the relationship between cognitive decline, bone loss, and fracture risk was examined in 2361 participants (74% female) selected from the general population [60]. Cognition was assessed using the MMSE. In women, but not in men, there was an association between cognitive decline and bone loss. The authors suggested that estrogen could mediate this association [60]. The association between dementia, low BMD, and osteoporosis was examined in 363 Turkish adults aged 65 years and over (63% female) [61]. In this study, BMD assessed by DXA was found lower in participants with dementia, but without differences based on the type of dementia (AD, vascular dementia, or mixed dementia), gender, disease duration, or severity.

In summary, cross-sectional and longitudinal data support an association between osteoporosis and poor cognition, independent of aging. This pattern appears to be more evident in women than in men, although further research is needed to identify mechanisms linking these deficits in bone and brain.

Muscle and Bone Crosstalk and Cognitive Impairment

A recent report examined lean mass (a surrogate for skeletal muscle mass) and bone mass in association with cognitive status among 535 Taiwanese participants, aged 65 years or over, of which 67.3% had normal cognition status, 18.3% had mild cognitive impairment, and 14.4% had a diagnosis of dementia [62]. An association between bone loss and cognitive impairment was detected. In addition, the authors claimed that diminishing lean mass reduced BMD, so was an indirect contributor to cognitive impairment. Parallel losses of lean and bone mass have also been reported using data from the GOS [63].

Frailty and Cognitive Impairment

Frailty is reduced resilience to stressors that may lead to declines in multiple functional systems. It is associated with skeletal muscle weakness, fatigue, reduced mobility, low physical activity, and weight loss [64]. Cognitive frailty is defined as concurrent physical frailty and cognitive impairment (excluding dementia and AD) [65], and is associated with adverse health outcomes, such as functional disability, depression, malnutrition, hospitalization, impaired quality of life, loss of independence, and, ultimately, mortality, in the elderly [66–68]. There is currently no universally recognized definition of cognitive frailty, which has been argued to constitute an independent dimension of frailty [69]. Our current understanding of the neuropathological pathways in cognitive frailty is insufficient to develop a cost-effective screening tool, partially because the high cost of specialized equipment (e.g., functional MRI) means that most research involved only small numbers of participants, giving low statistical power for detecting differences and changes. The pathological pathways in cognitive frailty are unclear. As described above, contracting skeletal muscle is a major source of neurotrophic factors, including BDNF, which regulates synapses in the brain [10]. Thus, BDNF is a plausible candidate for the as-yet unidentified mechanism linking skeletal muscle and brain function. Furthermore, skeletal muscle activity has immune and redox effects that support brain function [70] and reduce muscle catabolism [71]. Muscle loss, muscle weakness, fat infiltration into muscle, and frailty, in turn, appear to be associated with systemic and central inflammation and have been linked with impaired synaptic neuroplasticity and cognitive decline [72].

Oral (or dental) frailty has emerged as an indicator on the relationship between oral status and overall health [73]. It is characterized by a reduction in oral activity combined with both musculoskeletal and cognitive impairments. Particularly during aging, musculoskeletal functions such as mastication, swallowing, occlusal force, and tongue pressure are compromised, contributing to declined overall health status and frailty [74, 75••]. Although oral health has been extensively assessed in terms of neurodegeneration risk (e.g., periodontal pathogens and AD), further research on how oral frailty as a musculoskeletal syndrome may promote cognitive impairment is required [74, 75••].

Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms Underlying Musculoskeletal Deficits and Cognitive Impairment

As recent reviews [76–78] show, skeletal muscle and bone are dynamic tissues able to communicate both biomechanically and molecularly. In addition, molecular factors released from skeletal muscle and bone (myokines and osteokines, respectively) affect cognitive processes [76–78]. Since myokines and osteokines may be released in response to physical activity, it is reasonable to consider cellular and molecular crosstalk as potential mechanisms underpinning the relationship between the musculoskeletal system and cognition. Myokines, osteokines, and sex hormones are being studied in the hope of revealing avenues for development of therapies for cognitive detriments caused or aggravated by musculoskeletal deficits.

Myokines and Cognition

During contraction, skeletal muscle releases molecular factors that may affect cognitive function, such as BDNF, a neurotrophin required in adults for the maintenance of synaptic connections and adaptive neuronal plasticity, regulating cognitive processes such as learning and memory [79]. A study showed that after long-term voluntary exercise, adult male mice exhibited a lactate-dependent increase in hippocampal BDNF [80]. Interestingly, lactate (a metabolite released from muscle during exercise) was responsible for improvement in both learning and memory in these mice, and the induction of the hippocampal BDNF expression was found to be dependent on the sirtuin 1 (SIRT1)/peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor-γ coactivator 1-α (PGC1α)/fibronectin type III domain-containing 5 (FNDC5) pathway [80]. Furthermore, SIRT1 knockout male mice were found to be more anxious than wild-type mice and suffering cognitive impairment characterized by reduced learning abilities and memory [81]. In a rat model of AD, direct intervention in the hippocampus with the 42 amino acid form of amyloid β (Aβ1–42) resulted in cognitive impairment by suppressing PGC1α/FNDC5/BDNF signaling [82]. However, the cognitive impairment was partially reversed by moderate physical activity, revealing a recovered PGC1α/ FNDC5/BDNF pathway [82].

In addition, BDNF is released in response to muscle contraction [83], and percutaneous electrical stimulation of the hindlimb muscles in a rat model of spinal cord injury significantly increased BDNF levels in both the anterior tibialis and the vertebral column [84]. Importantly, deletion of BDNF in skeletal muscle in mice resulted in a fatigue-resistant muscle phenotype, migrating from fast to slow muscle fibers in glycolytic muscles tibialis anterior and extensor digitorum longus [85]. In contrast, BDNF overexpression increased the glycolytic and fast fiber phenotype of the muscles [85]. This is consistent with clinical findings, since BDNF levels in skeletal muscles induced by controlled physical activity were found to be correlated positively with muscle phenotypic changes favoring type II muscle fibers (fast and glycolytic) [86]. Moreover, serum BDNF was increased in sedentary subjects 1 h after training, but this was not found in trained young and adult patients, suggesting the relevance of physical conditioning when assessing the effect of training on BDNF induction [86]. In addition, the decrease of BDNF after training was correlated with improvement in cognitive processes such as visuospatial and verbal skills (measured using a before-and-after Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination-Revised test) [86]. Consistent results have been obtained in experimental models, involving young and aged rats, suggesting a role of the PGC1α/ FNDC5/BDNF pathway in the protection of cognition from a musculoskeletal health approach [87].

BDNF expression can also be affected by altered mastication. In growing mice receiving a soft diet, learning and memory processes were impaired, compared to mice eating standard chow, by the apparent decrease in masticatory function [88]. In addition, BDNF expression in the hippocampus of mice receiving soft chow was decreased compared to those fed with standard chow, whereas no changes on the BDNF receptor were found in either group [88]. Moreover, the reduced expression of BDNF was consistent with a decrease on the synapses, leading to degraded neuronal structure and therefore neural function [88]. These findings are consistent with those of a recent systematic review of animal studies that identified a relationship between altered mastication and cognitive impairment characterized by decreased expression of BDNF in the hippocampus, decreased synapses, low performance in behavioral evaluations, and diminished memory and spatial location [89••]. Interestingly, male rats fed with standard chow exhibited higher expression of BDNF hippocampus than those fed with either soft or hard chow [90]. This result poses the question of whether reduced and increased masticatory functions are risk factors for cognitive impairment, suggesting a focus on clinical conditions ranging from loss of teeth (and therefore decreased masticatory function) to masticatory muscle parafunction. Short-term exposure of young adult male mice to a soft diet results in dysregulated expression neurodegenerative condition–related genes such as TREM2, DAP12, APOE, and CD33 in the microglia, suggesting that soft diet has an immunomodulatory role as a risk factor for cognitive impairment [91]. Also, mastication on one side only has been shown to affect BDNF gene expression in the hippocampus, with cognitive impairment evaluated using the Morris Water Maze test in young adult male mice [92•]. In addition, using the MWM test, it was determined that reduced physical activity and reduced masticatory function in adult and aged mice affected their memory and learning skills, but these were restored when normal mastication was enabled [93]. The reduction of the branches in the astrocytes of the group with reduced physical activity and masticatory function [93] is intriguing, suggesting the need for more research into the role of the mastication as a neuroprotective musculoskeletal activity. For instance, in humans, masticatory function has been evaluated as a neuroprotective activity based on its clinical correlation with increased brain blood perfusion [27].

Irisin is a myokine released in response to physical activity, downstream of PGC1α/FNDC5 pathway activation, after FNDC5 cleavage [94, 95]. Irisin stimulates BDNF expression in the hippocampus [96], and is believed to mediate the effect of physical activity on BDNF expression [94, 95]. Continuous physical training increases BDNF and Irisin serum levels, with benefits for cognitive performance, measured as the working memory (part of short memory that is a cognitive ability that can hold the information in mind for executing cognitive function tasks [97]) in adults aged 50 to 70 years [98]. In male mice, injection of Irisin to the hippocampus after physical restraint improved the cognitive response to memory tasks. However, female mice did not benefit from Irisin administration, suggesting a sex-dependent effect [99]. Additionally, in FNDC5 knockout mice, absence of Irisin diminished cognitive skills (spatial and learning memory) after voluntary physical activity when compared with wild-type animals [100]. Interestingly, the same study showed that systemically administered Irisin was able to cross the blood–brain barrier and partially rescue cognitive impairment in two AD mouse models [100]. The mechanism of Irisin action remains to be fully understood. However, the use of AD mouse models has revealed a potential role of Irisin in neuroinflammation control [100] and cognition improvement after physical activity, with increased levels of FDNC5, BDNF, and IL-6 [101]. These findings can be compared and contrasted with clinical data about the correlation between Irisin levels in serum [102] or cerebrospinal fluid [103] and neurodegenerative/inflammatory biomarkers in conditions that affect cognition [102, 103].

Osteokines and Cognition

Osteokines are molecules released by osteoblasts and osteocytes. Among them, the osteoblast-derived protein osteocalcin or bone γ-carboxyglutamic acid (Gla) protein has been proposed to impact cognition [76, 104, 105]. Compared to baseline measurements, serum levels of osteocalcin increase after intense controlled physical activity to a similar extent in women and men [106]. A correlation study in young men exposed to reduced physical activity followed by a single session of high intensity training found that serum levels of both BDNF and undercarboxylated osteocalcin—the hormonally active form of the protein—were increased [107]. Irisin serum levels were also elevated after the intervention [107]. However, whether there is a molecular link among these molecules remains to be determined.

Musculoskeletal Health and Alzheimer’s Disease, the Potential Connection

Epidemiological evidence indicated a bidirectional relationship between musculoskeletal health and Alzheimer’s disease (AD); however, the shared pathways underlying this relationship are unclear [40]. Beeri et al. (2021) conducted a longitudinal study in the USA to examine the association between sarcopenia and AD incidence [108]. At baseline, 1175 men and women without dementia (mean age = 80.9 years) underwent cognitive testing and assessed sarcopenia parameters each year over a period of 5.6 years. Sarcopenia parameters included muscle mass measured by bioelectrical impedance analysis, muscle function by gait speed, and handgrip strength by a Jamar hydraulic hand dynamometer. Of note, commonly used sarcopenia definitions were not adopted in this study and, instead, cases with sarcopenia were identified using continuous measures of sarcopenia parameters by applying sex-specific binary classifications. Cognitive function was assessed globally (using MMSE and composite scores) and in five specific domains. Clinician-diagnosed dementia cases numbered 243 (78.6% women). This study reported that severe sarcopenia at baseline was associated with a higher risk of incident of AD and a steeper cognitive decline. Among the sarcopenia parameters, poor muscle function and low handgrip strength rather than low lean mass were identified as better risk indicators for AD. This study considered demographic characteristics (e.g., age, sex, and education), seven chronic health conditions (e.g., diabetes, heart diseases, and stroke) and lifestyle factors (e.g., smoking) as confounders; however, no fundamental mechanisms were tested or reported in this study.

Data from the Framingham Offspring Cohort Study in the USA were used to examine the association between BMD and brain structure, and BMD and cognitive function [109]. This study included 1905 men and women (mean age =66 years). BMD of the hip was measured using DXA. Cognitive function was assessed using a series of comprehensive cognitive tests including a neuropsychological battery that included executive function, processing speed, verbal and visual memory, and IQ tests that included dimensions such as abstraction, reasoning, verbal comprehension, and categorization (Wechsler Adult intelligence Scales), and visuo-perceptual skills (Hooper Visual Organization test). Measures of total brain volume, hippocampal volume, and white matter hyperintensity volume were obtained by MRI. This study reported sex-specific associations between higher BMD and better cognitive performance and less white matter hyperintensity burden. The authors proposed cumulative estrogen exposure as the potential underlying mechanism [109]. A large-scale study using a neurobiological approach combining neuroimaging techniques with the biological mechanism is expected to be conducted in this area [44].

Animal models have also been used to determine whether there are associations between cognitive impairments and musculoskeletal deficits. For this, mouse expressing mutations reported in humans with AD have been studied. One of the models is the mouse expressing the Swedish mutation of the amyloid precursor protein, which exhibit bone loss and increased osteoclastogenesis in young but not old mice, suggesting the changes in bone are not explained by the deposit of β-amyloid in the brain, which occurs in old mice [110]. Another model in which both the APP and presinilin1 are mutated (APP/PS1) showed reduced bone mass, but in this case the appearance of the plaque precedes the bone defect [111, 112]. This evidence suggests a disconnection between the central nervous system and the skeletal phenotype. Consistent with this notion, we recently reported a bone and skeletal muscle phenotype in a mouse model in which the R47H variant of the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) was globally expressed [113••]. TREM2 R47H is associated with increased risk of AD, frontotemporal dementia, and Parkinson’s disease in humans and mice [114–117]. The changes in musculoskeletal system were present even though the mice expressing TREM2 R47H do not show cognitive deficits and required the presence of additional mutation to increase the appearance of AD-like symptoms [113••]. These pieces of evidence suggest that the mechanisms of bone loss in AD patients might be independent of the central neuropathology

Future Directions

Future clinical studies could test lifestyle and/or pharmacological interventions that target musculoskeletal parameters associated with cognitive health to identify how particular interventions intended to improve musculoskeletal health in aging people might affect their cognitive status [118]. Further, brain imaging and neuro bio-techniques could be used to investigate the underlying mechanisms for concomitant changes in brain and musculoskeletal health in humans. In addition, studies on the associations between oral health and cognitive impairment are needed in the context of the musculoskeletal deficits, particularly with aging.

Conclusion

Recognizing the interplay between musculoskeletal deficits and cognitive impairment may have important translational implications, particularly because musculoskeletal health is responsive to behavioral modification. The bi-directional nature of links between musculoskeletal health and cognitive function remains somewhat obscure and their elucidation could be central to informing clinical practice and shaping public health policies for improving/maintaining physical and cognitive health.

Acknowledgements

SXS was supported by an Executive Dean Health Research Fellowship (Deakin University). JAP has received funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC); the Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF), Barwon Health, Deakin University, Amgen, the BUPA Foundation, Osteoporosis Australia, the Australian and New Zealand Bone and Mineral Society, the Geelong Community Foundation, Western Alliance, and the Norman Beischer Foundation. JBM is supported by a postdoctoral commission from the Universidad del Valle (Cali, Colombia). LIP research is supported by the Veterans Research Administration Merit Award 1I0 1BX005154.

Author Contribution

Structure and subtitle: SXS, LIP; drafting of the manuscript Abstract, Introduction, and Sections 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, and 8: SXS, JAP. Drafting of the manuscript Sections 1, 6, 7, 8, and 9: JBM, LIP; critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content: all authors.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Declarations

Disclosure

JAP has received speaker fees from Amgen, Eli Lilly, and Sanofi-Aventis. SXS, JBM, and LIP have nothing to disclose.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors. All studies in the referred manuscript complied with human and animal studies normative.

Conflict of interest

SXS was supported by an Executive Dean Health Research Fellowship (Deakin University). JAP has received funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF), Barwon Health, Deakin University, Amgen, the BUPA Foundation, Osteoporosis Australia, the Australian and New Zealand Bone and Mineral Society, the Geelong Community Foundation, Western Alliance, and the Norman Beischer Foundation. LIP research is supported by the Veterans Research Administration Merit Award 1I0 1BX005154

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Muscle and Bone

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Sophia X. Sui and Julián Balanta-Melo are co-first authors. Julie A. Pasco and Lilian I. Plotkin are co-senior authors.

Contributor Information

Sophia X. Sui, Email: sophia.sui@deakin.edu.au

Lilian I. Plotkin, Email: lplotkin@iupui.edu

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

- 1.Bliuc D, Tran T, Adachi JD, Atkins GJ, Berger C, van den Bergh J, Cappai R, Eisman JA, van Geel T, Geusens P, Goltzman D, Hanley DA, Josse R, Kaiser S, Kovacs CS, Langsetmo L, Prior JC, Nguyen TV, Solomon LB, Stapledon C, Center JR, For the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study Research G Cognitive decline is associated with an accelerated rate of bone loss and increased fracture risk in women: a prospective study from the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2021;36:2106–2115. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.4402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogawa Y, Kaneko Y, Sato T, Shimizu S, Kanetaka H, Hanyu H. Sarcopenia and muscle functions at various stages of Alzheimer disease. Front Neurol. 2018;9:710. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burns JM, Johnson DK, Watts A, Swerdlow RH, Brooks WM. Reduced lean mass in early Alzheimer disease and its association with brain atrophy. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(4):428–433. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sui SX, Pasco JA. Obesity and brain function: the brain-body crosstalk. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020;56(10) 10.3390/medicina56100499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Pasco JA, Williams LJ, Jacka FN, Stupka N, Brennan-Olsen SL, Holloway KL, Berk M. Sarcopenia and the common mental disorders: a potential regulatory role of skeletal muscle on brain function? Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2015;13(5):351–357. doi: 10.1007/s11914-015-0279-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papachristou E, Ramsay SE, Lennon LT, Papacosta O, Iliffe S, Whincup PH, Wannamethee SG. The relationships between body composition characteristics and cognitive functioning in a population-based sample of older British men. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:172. doi: 10.1186/s12877-015-0169-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sui SX, Ridding MC, Hordacre B. Obesity is associated with reduced plasticity of the human, motor cortex. Brain Sci. 2020;10(9):579. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10090579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willette AAK, D. Does the brain shrink as the waist expands? Ageing Res Rev. 2015;20:86–97. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luchsinger JAG, D. R. Adiposity and Alzheimer's disease. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2009;12(1):15–21. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32831c8c71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu B, Nagappan G, Lu Y. BDNF and synaptic plasticity, cognitive function, and dysfuction. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2014;220:223–250. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-45106-5_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matthews VB, Astrom MB, Chan MH, Bruce CR, Krabbe KS, Prelovsek O, Akerstrom T, Yfanti C, Broholm C, Mortensen OH, Penkowa M, Hojman P, Zankari A, Watt MJ, Bruunsgaard H, Pedersen BK, Febbraio MA. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor is produced by skeletal muscle cells in response to contraction and enhances fat oxidation via activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. Diabetologia. 2009;52(7):1409–1418. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1364-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lima Giacobbo B, Doorduin J, Klein HC, Dierckx R, Bromberg E, de Vries EFJ. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in brain disorders: focus on neuroinflammation. Mol Neurobiol. 2019;56(5):3295–3312. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-1283-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yadav VK, Oury F, Suda N, Liu ZW, Gao XB, Confavreux C, Klemenhagen KC, Tanaka KF, Gingrich JA, Guo XE, Tecott LH, Mann JJ, Hen R, Horvath TL, Karsenty G. A serotonin-dependent mechanism explains the leptin regulation of bone mass, appetite, and energy expenditure. Cell. 2009;138(5):976–989. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerosa L, Lombardi G. Bone-to-brain: a round trip in the adaptation to mechanical stimuli. Front Physiol. 2021;12:623893. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.623893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chandrasekaran B, Pesola AJ, Rao CR, Arumugam A. Does breaking up prolonged sitting improve cognitive functions in sedentary adults? A mapping review and hypothesis formulation on the potential physiological mechanisms. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021;22(1):274. doi: 10.1186/s12891-021-04136-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallace IJ, Hainline C, Lieberman DE. Sports and the human brain: an evolutionary perspective. Handb Clin Neurol. 2018;158:3–10. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63954-7.00001-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baker R, Coenen P, Howie E, Williamson A, Straker L. The short term musculoskeletal and cognitive effects of prolonged sitting during office computer work. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(8) 10.3390/ijerph15081678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Baker R, Coenen P, Howie E, Lee J, Williamson A, Straker L. A detailed description of the short-term musculoskeletal and cognitive effects of prolonged standing for office computer work. Ergonomics. 2018;61(7):877–890. doi: 10.1080/00140139.2017.1420825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker R, Coenen P, Howie E, Lee J, Williamson A, Straker L. Musculoskeletal and cognitive effects of a movement intervention during prolonged standing for office work. Hum Factors. 2018;60(7):947–961. doi: 10.1177/0018720818783945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang SH, Lee J, Jin S. Effect of standing desk use on cognitive performance and physical workload while engaged with high cognitive demand tasks. Appl Ergon. 2021;92:103306. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2020.103306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heiland EG, Tarassova O, Fernstrom M, English C, Ekblom O, Ekblom MM. Frequent, short physical activity breaks reduce prefrontal cortex activation but preserve working memory in middle-aged adults: ABBaH study. Front Hum Neurosci. 2021;15:719509. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2021.719509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meule A. Reporting and interpreting working memory performance in n-back tasks. Front Psychol. 2017;8:352. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stute K, Hudl N, Stojan R, Voelcker-Rehage C. Shedding Light on the effects of moderate acute exercise on working memory performance in healthy older adults: an fNIRS study. Brain Sci. 2020;10(11) 10.3390/brainsci10110813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Rodriguez-Gomez I, Manas A, Losa-Reyna J, Rodriguez-Manas L, Chastin SFM, Alegre LM, Garcia-Garcia FJ, Ara I. Associations between sedentary time, physical activity and bone health among older people using compositional data analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0206013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakamura M, Hamada T, Tanaka A, Nishi K, Kume K, Goto Y, Beppu M, Hijioka H, Higashi Y, Tabata H, Mori K, Mishima Y, Uchino Y, Yamashiro K, Matsumura Y, Makizako H, Kubozono T, Tabira T, Takenaka T, et al. Association of oral hypofunction with frailty, sarcopenia, and mild cognitive impairment: a cross-sectional study of community-dwelling Japanese older adults. J Clin Med. 2021;10(8) 10.3390/jcm10081626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Da Silva JD, Ni SC, Lee C, Elani H, Ho K, Thomas C, Kuwajima Y, Ishida Y, Kobayashi T, Ishikawa-Nagai S. Association between cognitive health and masticatory conditions: a descriptive study of the national database of the universal healthcare system in Japan. Aging (Albany NY) 2021;13(6):7943–7952. doi: 10.18632/aging.202843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chuhuaicura P, Dias FJ, Arias A, Lezcano MF, Fuentes R. Mastication as a protective factor of the cognitive decline in adults: a qualitative systematic review. Int Dent J. 2019;69(5):334–340. doi: 10.1111/idj.12486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin CS. Revisiting the link between cognitive decline and masticatory dysfunction. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0693-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bauer J, Morley JE, Schols AMWJ, Ferrucci L, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Dent E, Baracos VE, Crawford JA, Doehner W, Heymsfield SB, Jatoi A, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Lainscak M, Landi F, Laviano A, Mancuso M, Muscaritoli M, Prado CM, Strasser F, von Haehling S, Coats AJS, Anker SD. Sarcopenia: a time for action. An SCWD position paper. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2019;10(5):956–961. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fielding RA, Vellas B, Evans WJ, Bhasin S, Morley JE, Newman AB, Abellan van Kan G, Andrieu S, Bauer J, Breuille D, Cederholm T, Chandler J, De Meynard C, Donini L, Harris T, Kannt A, Keime Guibert F, Onder G, Papanicolaou D, Rolland Y, Rooks D, Sieber C, Souhami E, Verlaan S, Zamboni M. Sarcopenia: an undiagnosed condition in older adults. Current consensus definition: prevalence, etiology, and consequences. International working group on sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12(4):249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, Bruyère O, Cederholm T, Cooper C, Landi F, Rolland Y, Sayer AA, Schneider SM, Sieber CC, Topinkova E, Vandewoude M, Visser M, Zamboni M. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019;48(1):16–31. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afy169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Studenski SA, Peters KW, Alley DE, Cawthon PM, McLean RR, Harris TB, Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Fragala MS, Kenny AM, Kiel DP, Kritchevsky SB, Shardell MD, Dam TT, Vassileva MT. The FNIH sarcopenia project: rationale, study description, conference recommendations, and final estimates. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(5):547–558. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen LK, Woo J, Assantachai P, Auyeung TW, Chou MY, Iijima K, Jang HC, Kang L, Kim M, Kim S, Kojima T, Kuzuya M, Lee JSW, Lee SY, Lee WJ, Lee Y, Liang CK, Lim JY, Lim WS, Peng LN, Sugimoto K, Tanaka T, Won CW, Yamada M, Zhang T, Akishita M, Arai H. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 consensus update on sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(3):300–307.e302. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhasin S, Travison TG, Manini TM, Patel S, Pencina KM, Fielding RA, Magaziner JM, Newman AB, Kiel DP, Cooper C, Guralnik JM, Cauley JA, Arai H, Clark BC, Landi F, Schaap LA, Pereira SL, Rooks D, Woo J, Woodhouse LJ, Binder E, Brown T, Shardell M, Xue QL, RB DA, Sr, Orwig D, Gorsicki G, Correa-De-Araujo R, Cawthon PM. Sarcopenia definition: the position statements of the sarcopenia definition and outcomes consortium. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(7):1410–1418. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zanker J, Scott D, Reijnierse EM, Brennan-Olsen SL, Daly RM, Girgis CM, Grossmann M, Hayes A, Henwood T, Hirani V, Inderjeeth CA, Iuliano S, Keogh JWL, Lewis JR, Maier AB, Pasco JA, Phu S, Sanders KM, Sim M, Visvanathan R, Waters DL, Yu SCY, Duque G. Establishing an operational definition of sarcopenia in Australia and New Zealand: Delphi method based consensus statement. J Nutr Health Aging. 2019;23(1):105–110. doi: 10.1007/s12603-018-1113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mayhew AJ, Amog K, Phillips S, Parise G, McNicholas PD, de Souza RJ, Thabane L, Raina P. The prevalence of sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults, an exploration of differences between studies and within definitions: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Age Ageing. 2019;48(1):48–56. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afy106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pasco JA, Nicholson GC, Kotowicz MA. Cohort profile: Geelong Osteoporosis Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(6):1565–1575. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sui SX, Holloway-Kew KL, Hyde NK, Williams LJ, Tembo MC, Leach S, Pasco JA. Definition-specific prevalence estimates for sarcopenia in an Australian population: the Geelong Osteoporosis Study. JCSM Cli Rep. 2020;5(4):89–98. doi: 10.1002/crt2.22. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sui SX, Holloway-Kew KL, Hyde NK, Williams LJ, Tembo MC, Leach S, Pasco JA. Prevalence of sarcopenia employing population-specific cut-points: cross-sectional data from the Geelong Osteoporosis Study, Australia. J Clin Med. 2021;10(2) 10.3390/jcm10020343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Sui SX, Williams LJ, Holloway-Kew KL, Hyde NK, Pasco JA. Skeletal muscle health and cognitive function: a narrative review. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;22(1) 10.3390/ijms22010255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.••.Sui SX, Holloway-Kew KL, Hyde NK, Williams LJ, Leach S, Pasco JA. Muscle strength and gait speed rather than lean mass are better indicators for poor cognitive function in older men. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):10367. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-67251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.•.Sui SX, Williams LJ, Holloway-Kew KL, Hyde NK, Leach S, Pasco JA. Associations between muscle quality and cognitive function in older men: cross-sectional data from the Geelong Osteoporosis Study. J Clin Densitom. 2021;25:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2021.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.••.Sui SX, Williams LJ, Holloway-Kew KL, Hyde NK, Anderson KB, Tembo MC, Addinsall AB, Leach S, Pasco JA. Skeletal muscle density and cognitive function: a cross-sectional study in men. Calcif Tissue Int. 2020;108:165–175. doi: 10.1007/s00223-020-00759-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.•.Pasco JA, Stuart AL, Sui SX, Holloway-Kew KL, Hyde NK, Tembo MC, Rufus-Membere P, Kotowicz MA, Williams LJ. Dynapenia and low cognition: a cross-sectional association in postmenopausal women. J Clin Med. 2021;10(2):173. doi: 10.3390/jcm10020173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stenholm S, Harris TB, Rantanen T, Visser M, Kritchevsky SB, Ferrucci L. Sarcopenic obesity: definition, cause and consequences. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008;11(6):693–700. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328312c37d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tolea MI, Chrisphonte S, Galvin JE. Sarcopenic obesity and cognitive performance. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:1111–1119. doi: 10.2147/cia.S164113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang H, Hai S, Liu YX, Cao L, Liu Y, Liu P, Yang Y, Dong BR. Associations between sarcopenic obesity and cognitive impairment in elderly chinese community-dwelling individuals. J Nutr Health Aging. 2019;23(1):14–20. doi: 10.1007/s12603-018-1088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Low S, Goh KS, Ng TP, Ang SF, Moh A, Wang J, Ang K, Subramaniam T, Sum CF, Lim SC. The prevalence of sarcopenic obesity and its association with cognitive performance in type 2 diabetes in Singapore. Clin Nutr. 2020;39(7):2274–2281. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2019.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Batsis JA, Haudenschild C, Roth RM, Gooding TL, Roderka MN, Masterson T, Brand J, Lohman MC, Mackenzie TA. Incident impaired cognitive function in sarcopenic obesity: data from the National Health and Aging Trends Survey. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(4):865–872.e865. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tou NX, Wee SL, Pang BWJ, Lau LK, Jabbar KA, Seah WT, Chen KK, Ng TP. Associations of fat mass and muscle function but not lean mass with cognitive impairment: the Yishun Study. PLoS One. 2021;16(8):e0256702. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pasco JA, Kotowiczm MA. Osteopaenia – a marker of low bone mass and fracture risk. Hard Tissue. 2013;2(1):10. doi: 10.13172/2050-2303-2-1-368. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.WHO (2004) Scientific group on the assessment of osteoporosis at primary health care level. Paper presented at the World Health Organization, Geneva.

- 53.Pasco JA, Seeman E, Henry MJ, Merriman EN, Nicholson GC, Kotowicz MA. The population burden of fractures originates in women with osteopenia, not osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(9):1404–1409. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pasco JA, Mohebbi M, Holloway KL, Brennan-Olsen SL, Hyde NK, Kotowicz MA. Musculoskeletal decline and mortality: prospective data from the Geelong Osteoporosis Study. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2017;8(3):482–489. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kang HG, Park HY, Ryu HU, Suk SH. Bone mineral loss and cognitive impairment: the PRESENT project. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97(41):e12755. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sheppard PAS, Choleris E, Galea LAM. Structural plasticity of the hippocampus in response to estrogens in female rodents. Mol Brain. 2019;12(1):22. doi: 10.1186/s13041-019-0442-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lv X-L, Zhang J, Gao W-Y, Xing W-M, Yang Z-X, Yue Y-X, Wang Y-Z, Wang G-F. Association between osteoporosis, bone mineral density levels and Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Gerontol. 2018;12(2):76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijge.2018.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ebrahimpur M, Sharifi F, Shadman Z, Payab M, Mehraban S, Shafiee G, Heshmat R, Fahimfar N, Mehrdad N, Khashayar P, Nabipour I, Larijani B, Ostovar A. Osteoporosis and cognitive impairment interwoven warning signs: community-based study on older adults-Bushehr Elderly Health (BEH) Program. Arch Osteoporos. 2020;15(1):140. doi: 10.1007/s11657-020-00817-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee SH, Park SY, Jang MU, Kim Y, Lee J, Kim C, Kim YJ, Sohn JH. Association between osteoporosis and cognitive impairment during the acute and recovery phases of ischemic stroke. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020;56(6) 10.3390/medicina56060307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Bliuc D, Tran T, Adachi JD, Atkins GJ, Berger C, van den Bergh J, Cappai R, Eisman JA, van Geel T, Geusens P, Goltzman D, Hanley DA, Josse R, Kaiser S, Kovacs CS, Langsetmo L, Prior JC, Nguyen TV, Solomon LB, Stapledon C, Center JR. Cognitive decline is associated with an accelerated rate of bone loss and increased fracture risk in women: a prospective study from the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2021;36(11):2106–2115. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.4402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Başgöz B, İnce S, Safer U, Naharcı M, Taşçı İ. Low bone density and osteoporosis among older adults with Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia, and mixed dementia: a cross-sectional study with prospective enrollment. Turk J Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;66(2):193–200. doi: 10.5606/tftrd.2020.3803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lin SF, Fan YC, Pan WH, Bai CH. Bone and lean mass loss and cognitive impairment for healthy elder adults: analysis of the nutrition and health survey in Taiwan 2013-2016 and a validation study with structural equation modeling. Front Nutr. 2021;8:747877. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.747877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pasco JA. Age-related changes in muscle and bone. In: Duque G, editor. Osteosarcopenia: Bone, Muscle and Fat Interactions. Springer Nature, 2019; pp 45–71.

- 64.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kelaiditi E, Cesari M, Canevelli M, Abellan van Kan G, Ousset PJ, Gillette-Guyonnet S, Ritz P, Duveau F, Soto ME, Provencher V, Nourhashemi F, Salva A, Robert P, Andrieu S, Rolland Y, Touchon J, Fitten JL, Vellas B. Cognitive frailty: rational and definition from an (I.A.N.A./I.A.G.G.) International Consensus Group. J Nutr Health Aging. 2013;17(9):726–734. doi: 10.1007/s12603-013-0367-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Feng L, Zin Nyunt MS, Gao Q, Feng L, Yap KB, Ng T-P. Cognitive frailty and adverse health outcomes: findings from the Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Studies (SLAS) J Am Med Di Ass. 2017;18(3):252–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kwan RYC, Leung AYM, Yee A, Lau LT, Xu XY, Dai DLK. Cognitive frailty and its association with nutrition and depression in community-dwelling older people. J Nutr Health Aging. 2019;23(10):943–948. doi: 10.1007/s12603-019-1258-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ruan Q, Yu Z, Chen M, Bao Z, Li J, He W. Cognitive frailty, a novel target for the prevention of elderly dependency. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;20:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.De Roeck EE, van der Vorst A, Engelborghs S, Zijlstra GAR, Dierckx E, Consortium DS. Exploring cognitive frailty: prevalence and associations with other frailty domains in older people with different degrees of cognitive impairment. Gerontology. 2020;66(1):55–64. doi: 10.1159/000501168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Butterfield DA, Perluigi M, Sultana R. Oxidative stress in Alzheimer's disease brain: new insights from redox proteomics. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;545(1):39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Koltun DO, Marquart TA, Shenk KD, Elzein E, Li Y, Nguyen M, Kerwar S, Zeng D, Chu N, Soohoo D, Hao J, Maydanik VY, Lustig DA, Ng KJ, Fraser H, Zablocki JA. New fatty acid oxidation inhibitors with increased potency lacking adverse metabolic and electrophysiological properties. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14(2):549–552. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.09.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kumar A. Editorial: Neuroinflammation and cognition. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:413. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dibello V, Lozupone M, Manfredini D, Dibello A, Zupo R, Sardone R, Daniele A, Lobbezoo F, Panza F. Oral frailty and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Neural Regen Res. 2021;16(11):2149–2153. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.310672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Slashcheva LD, Karjalahti E, Hassett LC, Smith B, Chamberlain AM. A systematic review and gap analysis of frailty and oral health characteristics in older adults: a call for clinical translation. Gerodontology. 2021;38(4):338–350. doi: 10.1111/ger.12577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.••.Dibello V, Zupo R, Sardone R, Lozupone M, Castellana F, Dibello A, Daniele A, De Pergola G, Bortone I, Lampignano L. Oral frailty and its determinants in older age: a systematic review. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021;2(8):e507–e520. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(21)00143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Han Y, You X, Xing W, Zhang Z, Zou W. Paracrine and endocrine actions of bone-the functions of secretory proteins from osteoblasts, osteocytes, and osteoclasts. Bone Res. 2018;6:16. doi: 10.1038/s41413-018-0019-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kirk B, Feehan J, Lombardi G, Duque G. Muscle, bone, and fat crosstalk: the biological role of myokines, osteokines, and adipokines. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2020;18(4):388–400. doi: 10.1007/s11914-020-00599-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pedersen BK. Physical activity and muscle-brain crosstalk. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15(7):383–392. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0174-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Miranda M, Morici JF, Zanoni MB, Bekinschtein P. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor: a key molecule for memory in the healthy and the pathological brain. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019;13:363. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2019.00363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.El Hayek L, Khalifeh M, Zibara V, Abi Assaad R, Emmanuel N, Karnib N, El-Ghandour R, Nasrallah P, Bilen M, Ibrahim P, Younes J, Abou Haidar E, Barmo N, Jabre V, Stephan JS, Sleiman SF. Lactate mediates the effects of exercise on learning and memory through SIRT1-dependent activation of hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) J Neurosci. 2019;39(13):2369–2382. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1661-18.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shtaif B, Hornfeld SH, Yackobovitch-Gavan M, Phillip M, Gat-Yablonski G. Anxiety and cognition in cre- collagen type II sirt1 K/O male mice. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021;12:756909. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.756909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Azimi M, Gharakhanlou R, Naghdi N, Khodadadi D, Heysieattalab S. Moderate treadmill exercise ameliorates amyloid-beta-induced learning and memory impairment, possibly via increasing AMPK activity and up-regulation of the PGC-1alpha/FNDC5/BDNF pathway. Peptides. 2018;102:78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2017.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Leuchtmann AB, Adak V, Dilbaz S, Handschin C. The role of the skeletal muscle secretome in mediating endurance and resistance training adaptations. Front Physiol. 2021;12:709807. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.709807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hayashi N, Himi N, Nakamura-Maruyama E, Okabe N, Sakamoto I, Hasegawa T, Miyamoto O. Improvement of motor function induced by skeletal muscle contraction in spinal cord-injured rats. Spine J. 2019;19(6):1094–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2018.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Delezie J, Weihrauch M, Maier G, Tejero R, Ham DJ, Gill JF, Karrer-Cardel B, Ruegg MA, Tabares L, Handschin C. BDNF is a mediator of glycolytic fiber-type specification in mouse skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(32):16111–16120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1900544116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Maderova D, Krumpolec P, Slobodova L, Schon M, Tirpakova V, Kovanicova Z, Klepochova R, Vajda M, Sutovsky S, Cvecka J, Valkovic L, Turcani P, Krssak M, Sedliak M, Tsai CL, Ukropcova B, Ukropec J. Acute and regular exercise distinctly modulate serum, plasma and skeletal muscle BDNF in the elderly. Neuropeptides. 2019;78:101961. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2019.101961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Belviranli M, Okudan N. Exercise training protects against aging-induced cognitive dysfunction via activation of the Hippocampal PGC-1alpha/FNDC5/BDNF pathway. NeuroMolecular Med. 2018;20(3):386–400. doi: 10.1007/s12017-018-8500-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fukushima-Nakayama Y, Ono T, Hayashi M, Inoue M, Wake H, Ono T, Nakashima T. Reduced mastication impairs memory function. J Dent Res. 2017;96(9):1058–1066. doi: 10.1177/0022034517708771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.••.Piancino MG, Tortarolo A, Polimeni A, Bramanti E, Bramanti P. Altered mastication adversely impacts morpho-functional features of the hippocampus: a systematic review on animal studies in three different experimental conditions involving the masticatory function. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0237872. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sunariani J, Khoswanto C, Irmalia WR. Difference of brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression and pyramid cell count during mastication of food with varying hardness. J Appl Oral Sci. 2019;27:e20180182. doi: 10.1590/1678-7757-2018-0182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Seki M, Haino A, Ishikawa T, Inagawa H, Soma GI, Terada H, Nashimoto M. Mastication affects transcriptomes of mouse microglia. Anticancer Res. 2020;40(8):4719–4727. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.14473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.•.Jiang H, Yin H, Wang L, Feng C, Bai Y, Huang D, Zhang Q, Liu H, Hu Y. Memory impairment of chewing-side preference mice is associated with 5-HT-BDNF signal pathway. Mol Cell Biochem. 2021;476(1):303–310. doi: 10.1007/s11010-020-03907-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.de Siqueira Mendes FCC, Paixao L, Diniz DG, Anthony DC, Brites D, Diniz CWP, Sosthenes MCK. Sedentary life and reduced mastication impair spatial learning and memory and differentially affect dentate gyrus astrocyte subtypes in the aged mice. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:632216. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.632216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Flori L, Testai L, Calderone V. The "irisin system": from biological roles to pharmacological and nutraceutical perspectives. Life Sci. 2021;267:118954. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Young MF, Valaris S, Wrann CD. A role for FNDC5/Irisin in the beneficial effects of exercise on the brain and in neurodegenerative diseases. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2019;62(2):172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2019.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pesce M, La Fratta I, Paolucci T, Grilli A, Patruno A, Agostini F, Bernetti A, Mangone M, Paoloni M, Invernizzi M, de Sire A. From exercise to cognitive performance: role of irisin. Appl Sci. 2021;11(15):7120. doi: 10.3390/app11157120. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cowan N. Working memory underpins cognitive development, learning, and education. Educ Psychol Rev. 2014;26(2):197–223. doi: 10.1007/s10648-013-9246-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tsai CL, Pan CY, Tseng YT, Chen FC, Chang YC, Wang TC. Acute effects of high-intensity interval training and moderate-intensity continuous exercise on BDNF and irisin levels and neurocognitive performance in late middle-aged and older adults. Behav Brain Res. 2021;413:113472. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2021.113472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jodeiri Farshbaf M, Garasia S, Moussoki DPK, Mondal AK, Cherkowsky D, Manal N, Alvina K. Hippocampal injection of the exercise-induced myokine irisin suppresses acute stress-induced neurobehavioral impairment in a sex-dependent manner. Behav Neurosci. 2020;134(3):233–247. doi: 10.1037/bne0000367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Islam MR, Valaris S, Young MF, Haley EB, Luo R, Bond SF, Mazuera S, Kitchen RR, Caldarone BJ, Bettio LEB, Christie BR, Schmider AB, Soberman RJ, Besnard A, Jedrychowski MP, Kim H, Tu H, Kim E, Choi SH, Tanzi RE, Spiegelman BM, Wrann CD. Exercise hormone irisin is a critical regulator of cognitive function. Nat Metab. 2021;3(8):1058–1070. doi: 10.1038/s42255-021-00438-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Choi SH, Bylykbashi E, Chatila ZK, Lee SW, Pulli B, Clemenson GD, Kim E, Rompala A, Oram MK, Asselin C, Aronson J, Zhang C, Miller SJ, Lesinski A, Chen JW, Kim DY, van Praag H, Spiegelman BM, Gage FH, Tanzi RE. Combined adult neurogenesis and BDNF mimic exercise effects on cognition in an Alzheimer's mouse model. Science. 2018;361(6406) 10.1126/science.aan8821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 102.Fraga VG, Ferreira CN, Oliveira FR, Candido AL, das Gracas Carvalho M, Reis FM, Caramelli P, De Souza LC, Gomes KB. Irisin levels are correlated with inflammatory markers in frontotemporal dementia. J Clin Neurosci. 2021;93:92–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2021.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lourenco MV, Ribeiro FC, Sudo FK, Drummond C, Assuncao N, Vanderborght B, Tovar-Moll F, Mattos P, De Felice FG, Ferreira ST. Cerebrospinal fluid irisin correlates with amyloid-beta, BDNF, and cognition in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2020;12(1):e12034. doi: 10.1002/dad2.12034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wang JS, Mazur CM, Wein MN. Sclerostin and osteocalcin: candidate bone-produced hormones. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021;12:584147. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.584147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Obri A, Khrimian L, Karsenty G, Oury F. Osteocalcin in the brain: from embryonic development to age-related decline in cognition. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(3):174–182. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hiam D, Landen S, Jacques M, Voisin S, Alvarez-Romero J, Byrnes E, Chubb P, Levinger I, Eynon N. Osteocalcin and its forms respond similarly to exercise in males and females. Bone. 2021;144:115818. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2020.115818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nicolini C, Michalski B, Toepp SL, Turco CV, D'Hoine T, Harasym D, Gibala MJ, Fahnestock M, Nelson AJ. A single bout of high-intensity interval exercise increases corticospinal excitability, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, and uncarboxylated osteolcalcin in sedentary, healthy males. Neuroscience. 2020;437:242–255. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2020.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Beeri MS, Leugrans SE, Delbono O, Bennett DA, Buchman AS. Sarcopenia is associated with incident Alzheimer's dementia, mild cognitive impairment, and cognitive decline. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(7):1826–1835. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Stefanidou M, O'Donnell A, Himali JJ, DeCarli C, Satizabal C, Beiser AS, Seshadri S, Tan Z. Bone mineral density measurements and association with brain structure and cognitive function: the Framingham Offspring cohort. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2021;35(4):291–297. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Cui S, Xiong F, Hong Y, Jung JU, Li XS, Liu JZ, Yan R, Mei L, Feng X, Xiong WC. APPswe/Aβ regulation of osteoclast activation and RAGE expression in an age-dependent manner. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(5):1084–1098. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Yang M-W, Wang T-H, Yan P-P, Chu L-W, Yu J, Gao Z-D, Li Y-Z, Guo B-L. Curcumin improves bone microarchitecture and enhances mineral density in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Phytomedicine. 2011;18(2):205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Radde R, Bolmont T, Kaeser SA, Coomaraswamy J, Lindau D, Stoltze L, Calhoun ME, Jaggi F, Wolburg H, Gengler S, Haass C, Ghetti B, Czech C, Holscher C, Mathews PM, Jucker M. Abeta42-driven cerebral amyloidosis in transgenic mice reveals early and robust pathology. EMBO Rep. 2006;7(9):940–946. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.••.Essex AL, Huot JR, Deosthale P, Wagner A, Figueras J, Davis A, Damrath J, Pin F, Wallace J, Bonetto A, Plotkin LI. TREM2 R47H variant causes distinct age- and sex-dependent musculoskeletal alterations in mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2022; 10.1002/jbmr.4572. This study shows a comprehensive anaysis of the musculoskeletal phenotype of mice expressing a gene variant that confers increased risk to developing AD, without central nervous phenotype [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 114.Ulrich JD, Ulland TK, Colonna M, Holtzman DM. Elucidating the Role of TREM2 in Alzheimer's Disease. Neuron. 2017;94(2):237–248. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Jay TR, Hirsch AM, Broihier ML, Miller CM, Neilson LE, Ransohoff RM, Lamb BT, Landreth GE. Disease progression-dependent effects of TREM2 deficiency in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2017;37(3):637–647. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2110-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ransohoff RM. How neuroinflammation contributes to neurodegeneration. Science. 2016;353(6301):777–783. doi: 10.1126/science.aag2590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Korvatska O, Leverenz JB, Jayadev S, McMillan P, Kurtz I, Guo X, Rumbaugh M, Matsushita M, Girirajan S, Dorschner MO, Kiianitsa K, Yu C-E, Brkanac Z, Garden GA, Raskind WH, Bird TD. R47H variant of TREM2 associated with Alzheimer disease in a large late-onset family: clinical, genetic, and neuropathological study. JAMA Neurology. 2015;72(8):920–927. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.0979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.De Spiegeleer A, Beckwée D, Bautmans I, Petrovic M, Bautmans I, Beaudart C, Beckwée D, Beyer I, Bruyère O, De Breucker S, De Cock A-M, Delaere A, de Saint-Hubert M, De Spiegeleer A, Gielen E, Perkisas S, Vandewoude M, the Sarcopenia Guidelines Development group of the Belgian Society of G. Geriatrics Pharmacological interventions to improve muscle mass, muscle strength and physical performance in older people: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Drugs Aging. 2018;35(8):719–734. doi: 10.1007/s40266-018-0566-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]