Abstract

Histiocytic sarcoma (HS) is a rare disease with a poor prognosis. The efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors for this disease has not been established. A 13-year-old boy with HS refractory to conventional chemotherapy was treated with pembrolizumab, an immune checkpoint inhibitor. After treatment, the primary lesion and the bone metastases showed improvement; however, new metastatic lesions also occurred. This case suggests that the effect of immune checkpoint inhibitors might depend not only on programmed death ligand-1 expression and the ratio of tumor mutational burden, but also on other factors, such as the tumor microenvironment. Evaluation of more cases is required to identify biomarkers that define the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Keywords: Histiocytic sarcoma, Pembrolizumab, PD-L1

Introduction

Histiocytic sarcoma (HS) is a hematopoietic neoplasm characterized by histiocytic morphology and immunophenotypic features of mature histiocytes. HS is an extremely rare disease with peak onset at ages 0–29 and 50–69 years [1–3]. Patients with HS exhibit variable clinical presentations, ranging from localized sites to multisystem multisite disease involving the skin, soft tissues, gastrointestinal tract, lung, and/or central nervous system. No standard treatments exist due to the very low disease frequency. However, response to conventional chemotherapy is generally poor [4]. The median overall survival in a recent survey of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database was 6 months, and the 5-year disease specific survival was 42.3% for males and 33.6% for females [5]. Programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) is highly expressed in histiocytic disorders, suggesting a potential therapeutic target for immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) [6, 7]. However, the efficacy of ICIs in HS has not been established, and only a few cases have been reported [8–10]. Here we present a case of relapsed HS treated with pembrolizumab, an immune checkpoint inhibitor, and provide review of patients with HS treated with ICIs.

Case presentation

A 13-year-old male presented with a left mandibular mass that gradually increased in size over a month. Accumulation of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) localized to the left mandibular mass with no distant metastasis, according to the FDG positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET–CT). The tumor was resected, and the histopathological examination revealed diffuse growth of large cells with well-defined nucleoli, large round or highly pleomorphic nuclei, and acidophilic sporangia. These atypical cells were positive for CD68 and CD163 on immunostaining; CD1a and markers of T-cell (CD3) and B cell (CD20) lineages were negative (Fig. 1). These findings led to a diagnosis of HS. Chemotherapy with cladribine (2-CdA) and high-dose cytosine arabinoside, which is used for refractory Langerhans cell histiocytosis, was administered as the initial therapy [11]. After three courses of chemotherapy, PET–CT showed residual tumor. Therefore, the patient underwent resection of the residual tumor. However, histopathology showed residual active tumor cells. Two additional courses of chemotherapy were administered and the patient underwent residual tumor removal again. Vinblastine (VBL), prednisolone (PSL), 6-mercaptopurine (6MP), and methotrexate (MTX), which are effective in treating refractory multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis, was administered as maintenance therapy [12]. However, recurrence occurred in the deep layer of the left sternocleidomastoid muscle 4 months after the last surgery. The patient underwent tumor resection again, and oral pazopanib, a multi-tyrosine kinase inhibitor, was administered. However, PET–CT showed left cervical lymph node metastasis, right lower abdominal metastasis, and multiple bone metastasis (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 1.

Histologic findings of the tumor. A to E are primary tumor specimens, and F is a brain metastasis specimen. A Hematoxylin and eosin stain. Diffuse growth of large cells with well-defined nucleoli, large round or highly pleomorphic nuclei, and acidophilic sporangia. B Atypical cells were positive for CD68 on immunostaining. C Atypical cells were positive for CD163 on immunostaining. D Atypical cells were negative for CD1a on immunostaining. E Atypical cells were positive for programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) on immunostaining. F PD-L1 expression in the brain metastasis specimen was the same as that in the primary tumor

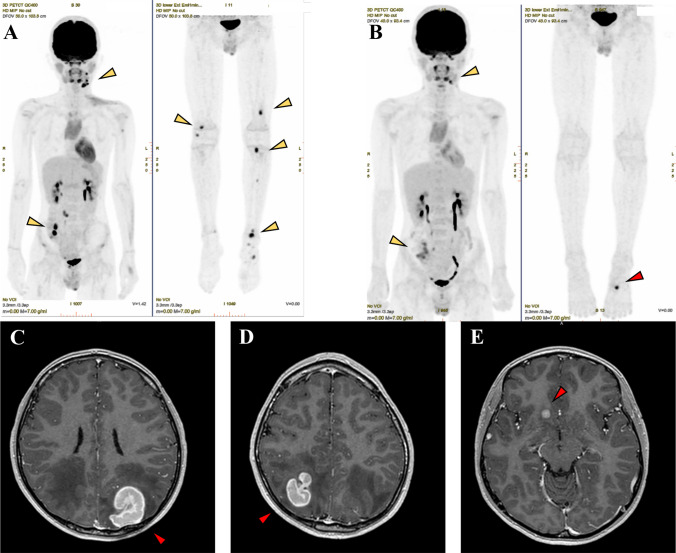

Fig. 2.

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography images before and after four cycles of pembrolizumab administration (top panel) and brain contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging after four cycles of pembrolizumab administration. A Yellow arrows indicate left cervical lymph node metastasis, right lower abdominal metastasis, and multiple bone metastasis. B After four cycles of pembrolizumab, multiple bone metastases in the whole body disappeared, and the accumulation of left submandibular lymph node metastasis and right lower abdominal lymph node metastasis decreased (yellow arrow). However, a new bone metastasis was found in the left first metatarsal (red arrow). C–E Brain metastases were confirmed in the bilateral parietal lobes and right frontal lobe after four cycles of pembrolizumab (red arrow)

Due to the refractory course in response to conventional chemotherapy, PD-L1 immunohistochemistry and cancer multi-gene panel testing (FoundationOne CDx) were performed on primary and recurrent tumor samples. The test showed PD-L1 expression in 40% of the tumor cells and no mutation that was a candidate for treatment, but the tumor mutational burden (TMB) was high at 12.61/Mb (Fig. 1). Therefore, pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg every 2 weeks was initiated. After four cycles of pembrolizumab, PET–CT showed the disappearance of multiple bone metastases that were present in the whole body before starting pembrolizumab. The accumulation of left submandibular and right lower abdominal lymph node metastases decreased from 10.8 to 9.1 and from 18.7 to 5.4 in SUV value, respectively (Fig. 2B). We also observed brain metastasis in the bilateral parietal and right frontal lobe and new bone metastasis in the left first metatarsal (Fig. 2B–E). Metastatic brain tumors in the bilateral parietal lobes were surgically resected, and the right frontal lobe lesion was treated with a gamma knife. Radiation therapy (total 30 Gy) was performed for the bone metastasis in the first metatarsal.

Histopathological analysis revealed that the brain tumor consisted of large atypical cells with well-defined nucleoli, similar to the primary tumor, and densely enlarged with multinucleated leukocytes and scattered mitotic figures. Immunostaining showed CD163 and CD68 positivity and CD1a negativity, as in the primary tumor, consistent with brain metastasis of HS. PD-L1 expression in brain metastasis specimens was similar to that in the primary and metastatic lesions (Fig. 1). After treatment of the relapse sites, pembrolizumab treatment was discontinued, and five cycles of systemic chemotherapy with ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide (ICE) were administered. After five cycles of ICE therapy, PET–CT showed complete remission (CR). High-dose chemotherapy with busulfan and melphalan was administered with autologous bone marrow transplantation, and CR was maintained to the present time (2 months after transplantation).

Discussion

We present a case of relapsed HS treated with pembrolizumab. Pembrolizumab treatment resulted in disappearance of systemic bone metastases and a significant decrease in FDG accumulation in the primary tumor and metastatic foci. On the other hand, new brain and left foot metastases appeared, demonstrating that the efficacy of pembrolizumab varies depending on the site of the disease.

Although recent reports have demonstrated elevated PD-L1 expression in histiocytic disorders [6], only a few cases of ICIs treatment of HS have been reported (Table 1) [8–10]. While PD-L1 expression was reported in both cases (15–20% and 75%), the tumor response to ICIs differed, with partial response and progressive disease reported. Increased PD-L1 expression has been suggested to be associated with a favorable response to ICIs [13], but these cases indicate that the precise level of PD-L1 expression may influence treatment response. Despite these results, the use of PD-L1 as a predictive biomarker remains controversial, because PD-L1 measurement methods and cutoff values vary in previous studies [14]. In the case studies cited above, PD-L1 expression was tested at the time of initial diagnosis, with no further analysis at the time of PD-L1 inhibitor administration. Therefore, temporal heterogeneity must be considered when the relationship between PD-L1 expression rate and treatment effect is evaluated. In this case, PD-L1 expression was examined in primary, recurrent, and brain metastasis specimens. PD-L1 expression in the brain metastasis specimen was the same as expression in the primary tumor and metastasis. However, the response to pembrolizumab was different at each disease site. Furthermore, patients with high TMB may have a better response to ICIs [15, 16]. Patients with HS have higher TMB compared with other histiocytic neoplasms and are expected to respond better to ICIs [17]. In the current case, the TMB was as high as 12.61 /Mb, and the result was not what we expected.

Table 1.

Summary of cases using immune checkpoint inhibitors for HS

| Author | Tumor type | Age | Sex | Primary site | Metastasis | PD-L1 expression | Oncogenic mutation | TMB | Agent | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bose (2019) [8] | HS | 17 | Female | NR | Lung, Bone | 75% | NR | NR | Nivolumab | PR |

| Voruz (2018) [9, 10] | HS | 66 | Male | Ileum | Mediastinum, liver, abdomen, bone | 15–20% | PTPN11 | NR | Nivolumab | PD |

| Current case | HS | 13 | Male | Neck | Brain, abdomen, bone | 40% | BRAF(G466E), KRAS(G13D) | 12.61 /Mb | Pembrolizumab | PD |

HS histiocytic sarcoma, TMB tumor mutational burden, NR not reported, PR partial response; PD progressive disease

PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors enhance the anti-tumor immune response by blocking binding of the tumor cell PD-L1 ligand to the PD-1 receptor on T cells [18]. PD-L1 expression, TMB and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) are potential biomarkers for the effectiveness of immune checkpoint inhibitors [16, 19, 20]. Increased infiltration of CD8+ T cells is associated with improved therapeutic response [20, 21], while the presence of CD4+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells is associated with therapeutic resistance [22]. The tumor microenvironment contains a variety of immune populations, including lymphocytes, dendric cells, and macrophages, which have a significant impact on tumor growth. Furthermore, the complex system of the tumor microenvironment also contains non-immune stromal cells, including endothelial cells, and neovascularization caused by cancer may inhibit normal lymphocyte infiltration [23].

The immune system of the brain is more tightly regulated compared with that of peripheral organs. In a report comparing PD-L1 expression and TILs in primary and brain metastases of non-small cell lung cancer, PD-L1 expression varied between the primary and brain metastases, but the density of TILs was lower in brain metastases [19]. The number of TILs in the microenvironment of brain metastases is highly heterogeneous and varies from patient to patient. In fact, the density of TILs in brain tumors has been reported to be associated with survival prognosis [20]. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) within the brain have also been shown to suppress T-cell immune activity and promote tumor formation in studies primarily involving gliomas [24]. In addition, the blood–brain-barrier protects the brain from inflammation and systemic insults, which distinguishes the brain from other organs.

It was difficult to predict the response to pembrolizumab in the present case based on the tumor size and location. Furthermore, there was clinical heterogeneity, especially in brain and bone metastases. We did not examine all factors involved in the tumor microenvironment in all lesions; data on PD-L1 expression, TMB, TILs, TAM, and stromal cells was inadequate to do so. Therefore, the results should be considered with caution, and firm conclusions cannot be made. However, the mixed clinical responses of lesions to pembrolizumab suggest that there was heterogeneity of the tumor cells and microenvironment.

Previous reports of the use of ICIs for HS did not include cases of brain metastases, and the immune checkpoint inhibitor, nivolumab, was used. Therefore, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of the use of pembrolizumab for brain metastatic HS. Our results suggest that pembrolizumab may be effective for patients with PD-L1-positive HS, but the therapeutic effect may be limited and dependent on the tumor site microenvironment, especially for brain metastasis.

Patients with relapsed or refractory multisystem HS are generally treated with systemic chemotherapy, but conventional chemotherapy regimens provide only transient disease control. In patients with the BRAF V600E mutation, the use of BRAF inhibitors, such as vemurafenib or dabrafenib, can be considered. These agents are efficacious against Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Patients with mutations in the MAPK2K1 pathway may also be sensitive to MEK inhibitors [9]. In this case, the cancer gene panel test did not detect any actionable gene mutations. Since conventional chemotherapy is insufficiently effective, new therapies based on genetic mutations need to be developed. In addition, elucidation of more detailed biomarkers and other factors are needed to determine which cases of HS will benefit from ICIs.

One limitation of this paper is that it is a case report and the efficacy of ICIs for HS is difficult to determine in only one case. However, HS is a rare disease and no standard treatments have been developed. Therefore, sufficient analysis of each case is important.

In conclusion, ICIs may be effective for HS with known high PD-L1 expression, but evaluations of efficacy must take into account not only PD-L1 expression and TMB, but also various other factors, such as the tumor microenvironment. More cases are required to identify biomarkers that define efficacy of ICIs.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Enago (www.enago.jp) for English language review.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Ethical approval

Informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parents for the publication of this case report, and publication was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nagano Children’s Hospital (K-03-61).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Takahashi E, Nakamura S. Histiocytic sarcoma : an updated literature review based on the 2008 WHO classification. J Clin Exp Hematop. 2013;53:1–8. doi: 10.3960/jslrt.53.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skala SL, Lucas DR, Dewar R. Histiocytic sarcoma: review, discussion of transformation from B-cell lymphoma, and differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:1322–1329. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2018-0220-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auerbach A, Schmieg JJ, Aguilera NS. Pediatric lymphoid and histiocytic lesions in the head and neck. Head Neck Pathol. 2021;15:41–58. doi: 10.1007/s12105-020-01257-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vos JA, Abbondanzo SL, Barekman CL, et al. Histiocytic sarcoma: a study of five cases including the histiocyte marker CD163. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:693–704. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kommalapati A, Tella SH, Durkin M, et al. Histiocytic sarcoma: a population-based analysis of incidence, demographic disparities, and long-term outcomes. Blood. 2018;131:265–268. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-10-812495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gatalica Z, Bilalovic N, Palazzo JP, et al. Disseminated histiocytoses biomarkers beyond BRAFV600E: frequent expression of PD-L1. Oncotarget. 2015;6:19819–19825. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu J, Sun HH, Fletcher CDM, et al. Expression of programmed cell death 1 ligands (PD-L1 and PD-L2) in histiocytic and dendritic cell disorders. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:443–453. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bose S, Robles J, McCall CM, et al. Favorable response to nivolumab in a young adult patient with metastatic histiocytic sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66:e27491. doi: 10.1002/pbc.27491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Voruz S, Martins F, Cairoli A, et al. Response to MEK inhibition with trametinib and tyrosine kinase inhibition with imatinib in multifocal histiocytic sarcoma. Haematologica. 2018;103(1):e39–e41. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2017.179150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voruz S, Martins F, Cairoli A, et al. Comment on “MEK inhibition with trametinib and tyrosine kinase inhibition with imatinib in multifocal histiocytic sarcoma”. Haematologica. 2018;103:e130. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2017.186932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwabuchi H, Kawashima H, Umezu H, et al. Successful treatment of histiocytic sarcoma with cladribine and high-dose cytosine arabinoside in a child. Int J Hematol. 2017;106:299–303. doi: 10.1007/s12185-017-2202-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donadieu J, Bernard F, van Noesel M, et al. Cladribine and cytarabine in refractory multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis: results of an international phase 2 study. Blood. 2015;126:1415–1423. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-635151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel SP, Kurzrock R. PD-L1 expression as a predictive biomarker in cancer immunotherapy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14:847–856. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishino M, Ramaiya NH, Hatabu H, Hodi FS. Monitoring immune-checkpoint blockade: response evaluation and biomarker development. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14:655–668. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodman AM, Kato S, Bazhenova L, et al. Tumor mutational burden as an independent predictor of response to immunotherapy in diverse cancers. Mol Cancer Ther. 2017;16:2598–2608. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yarchoan M, Hopkins A, Jaffee EM. Tumor mutational burden and response rate to PD-1 inhibition. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2500–2501. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1713444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goyal G, Lau D, Nagle AM, et al. Tumor mutational burden and other predictive immunotherapy markers in histiocytic neoplasms. Blood. 2019;133:1607–1610. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-12-893917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conway JR, Kofman E, Mo SS, et al. Genomics of response to immune checkpoint therapies for cancer: implications for precision medicine. Genome Med. 2018;10:93. doi: 10.1186/s13073-018-0605-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiao G, Liu Z, Gao X, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for brain metastases in non-small-cell lung cancer: from rationale to clinical application. Immunotherapy. 2021;13:1031–1051. doi: 10.2217/imt-2020-0262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berghoff AS, Fuchs E, Ricken G, et al. Density of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes correlates with extent of brain edema and overall survival time in patients with brain metastases. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5:e1057388. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1057388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahmoud SMA, Paish EC, Powe DG, et al. Tumor-infiltrating CD8+ lymphocytes predict clinical outcome in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1949–1955. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.5037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takeuchi Y, Nishikawa H. Roles of regulatory T cells in cancer immunity. Int Immunol. 2016;28:401–409. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxw025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piali L, Fichtel A, Terpe HJ, et al. Endothelial vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 expression is suppressed by melanoma and carcinoma. J Exp Med. 1995;181:811–816. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.2.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hussain SF, Yang D, Suki D, et al. The role of human glioma-infiltrating microglia/macrophages in mediating antitumor immune responses. Neuro Oncol. 2006;8:261–279. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2006-008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]