The addition of the immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICPi), pembrolizumab, to standard pemetrexed- and platinum-based chemotherapy has improved progression-free and overall survival in patients with metastatic nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) regardless of programmed death-ligand 1 expression.1 However, ICPis, pemetrexed-, and platinum-based chemotherapies each have nephrotoxic potential,2–5 raising concern that combination therapy may result in a higher incidence and severity of acute kidney injury (AKI) compared with pembrolizumab monotherapy.6 In a phase-3 multicenter trial (KEYNOTE-189), which compared pemetrexed- and a platinum-based agent (either cisplatin or carboplatin) with versus without pembrolizumab in patients with metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC, AKI occurred in 12.2% of patients in the pembrolizumab-carboplatin-pemetrexed group (here-after referred to as “triplet therapy”) compared with 7.6% in the carboplatin-pemetrexed group, suggesting a higher incidence of AKI with triplet therapy.1 Triplet therapy is now first-line treatment for patients with nonsquamous NSCLC with low programmed death-ligand 1 expression, lacking a targetable mutation in EGFR or ALK, and pembrolizumab monotherapy is first-line treatment for patients with high programmed death-ligand 1 expression. Despite the growing use of these therapies, there are few data regarding the incidence and severity of AKI, along with kidney recovery in patients receiving triplet therapy versus pembrolizumab monotherapy.

To address this knowledge gap, we used data from 2 separate cohorts to characterize the clinical features and outcomes of AKI in patients receiving triplet therapy versus pembrolizumab monotherapy for nonsquamous NSCLC. The Massachusetts General Brigham (MGB) cohort consisted of adult patients receiving first-line pembrolizumab for nonsquamous NSCLC, whereas the ICPi-associated AKI (ICPi-AKI) cohort was a multicenter study of adults diagnosed with AKI directly attributable to the ICPi. The primary objective was to determine the incidence of AKI in the MGB cohort, AKI severity and treatment, and kidney recovery rates in patients receiving triplet therapy versus pembrolizumab in both cohorts.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

In the MGB cohort, 1584 patients received pembrolizumab for thoracic cancer. After applying the exclusions shown in Supplementary Figure S1A, the cohort consisted of 872 patients with nonsquamous NSCLC, 361 (41%) of whom received triplet therapy and 511 (59%) of whom received pembrolizumab monotherapy (Table 1).7 Patients in the pembrolizumab monotherapy group were older and had a lower baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate than those in the triplet therapy group (mean age: 70 [SD ± 12] years vs. 65 [SD ± 10] years, P < 0.01; mean estimated glomerular filtration rate: 80 [SD ± 23] ml/min per 1.73 m2 vs. 87 [SD ± 18] ml/min per 1.73 m2, P < 0.01). Patients receiving pembrolizumab monotherapy were more likely to have eosinophilia at the time of AKI (21% vs. 2%; P < 0.01) but had mostly similar rates of extrarenal immune-related adverse events before or concomitant with AKI diagnosis (23% vs. 15%; P = 0.21; Table 1, Supplementary Table S1A and B). Proton pump inhibitor use was similar between the groups.

Table 1 |.

Baseline characteristics

| Variable at baseline | MGB cohort | ICPi-AKI cohort | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triplet therapy (n = 361) |

Pembrolizumab monotherapy (n = 511) |

Triplet therapy (n = 23) |

Pembrolizumab monotherapy (n = 40) |

|

| Age at ICPi initiation, yr, mean (±SD) | 65 (±10) | 70 (±12) | 65 (±11) | 66 (±9) |

| Male, n (%) | 186 (52) | 258 (50) | 8 (35) | 13 (33) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White | 329 (91) | 455 (89) | 15 (65) | 35 (88) |

| Black | 9 (2) | 26 (5) | 5 (22) | 2 (5) |

| Other/unknown | 23 (6) | 29 (6) | 3 (13) | 3 (8) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 218 (60) | 292 (57) | 12 (52) | 16 (40) |

| Diabetes | 77 (21) | 109 (21) | 1 (4) | 3 (8) |

| CHF | 10 (3) | 27 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| COPD | 73 (20) | 131 (26) | 3 (13) | 8 (20) |

| Chronic liver disease | 2 (1) | 4 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Baseline eGFR,a ml/min per 1.73 m2 | ||||

| Mean (±SD) | 87 (±18) | 80 (±23) | 81 (±25) | 84 (±23) |

| eGFR categories, n (%) | ||||

| ≥90 | 187 (52) | 195 (38) | 11 (48) | 19 (48) |

| 60–89 | 141 (39) | 215 (42) | 7 (30) | 16 (40) |

| 45–59 | 28 (8) | 55 (11) | 3 (13) | 2 (5) |

| <45 | 5 (1) | 46 (9) | 2 (9) | 3 (8) |

| MGB cohort | ICPi-AKI cohort | |||

| Variable at time of AKI | Triplet therapy, patients with AKI (n = 82) | Pembrolizumab monotherapy, patients with AKI (n = 95) |

Triplet therapy (n = 23) | Pembrolizumab monotherapy (n = 40) |

| Time to AKI, d, median (IQR) | 81 (21–132) | 70 (28–126) | 105 (65–140) | 202 (128–315) |

| Peak SCr, mg/dl, median (IQR) | 1.2 (1.0–1.6) | 1.38 (1.1–2.1) | 3.1 (2.3–3.8) | 2.6 (1.9–3.7) |

| Eosinophils >500/μl, n (%)b | 2 (2) | 20 (21) | 1 (4) | 7 (18) |

| Extrarenal irAE, n (%)b | 12 (15) | 22 (23) | 4 (17) | 17 (43) |

| PPI, n (%)b | 19 (23) | 14 (15) | 13 (57) | 17 (43) |

| Antibiotics, n (%)b | 24 (29) | 13 (14) | 1 (4) | 3 (8) |

| Biopsy done, n (%) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 12 (52) | 17 (43) |

| ATIN, n (%)c | 1 (100) | 1 (50) | 11 (92) | 14 (82) |

| ICPi held, n (%) | 22 (27) | 35 (37) | 21 (91) | 34 (85) |

| Corticosteroid use, n (%)d | 9 (11) | 9 (10) | 22 (96) | 37 (93) |

| Day to recovery, median (IQR) | 11 (2–26) | 10 (2–29) | 46 (22–56) | 39 (17–66) |

There were 2 patients from the MGB cohort who overlapped with the ICPi-AKI cohort (as MGB was one of the 30 participating sites in the ICPi-AKI cohort). Data on eosinophilia were missing in 1 patient who received triplet therapy in each cohort. All other data are complete.

Baseline eGFR was calculated based on the Chronic Kidney Disease-Epidemiology Collaboration equation.7

Eosinophilia was assessed at the time of AKI. Extrarenal irAEs were assessed before (>14 days) or concomitant (within 14 days) with AKI. PPIs and antibiotics were assessed in the 14 days preceding AKI.

ATIN was the dominant lesion on kidney biopsy.

Corticosteroid use was defined as at least 0.5 mg/kg/d in prednisone equivalents within 2 weeks of AKI.

AKI, acute kidney injury; ATIN, acute tubulointerstitial nephritis; CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ICPi-AKI, immune checkpoint inhibitor–associated acute kidney injury; IQR, interquartile range; irAE, immune-related adverse event; MGB, Massachusetts General Brigham; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; SCr, serum creatinine.

In the ICPi-AKI cohort, 63 patients with nonsquamous NSCLC received pembrolizumab, of whom 23 (37%) received triplet therapy and 40 (63%) received pembrolizumab monotherapy (Supplementary Figure S1B). Patients who received triplet versus pembrolizumab monotherapy were similar with respect to age, sex, comorbidities, baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate, and proton pump inhibitor use (Table 1). Prior or concomitant extrarenal immune-related adverse events were more common among those receiving pembrolizumab monotherapy compared with triplet therapy, though this trend did not reach statistical significance (43% vs. 17%; P = 0.10; Table 1, Supplementary Table S1A and B).

AKI incidence, etiology, and severity

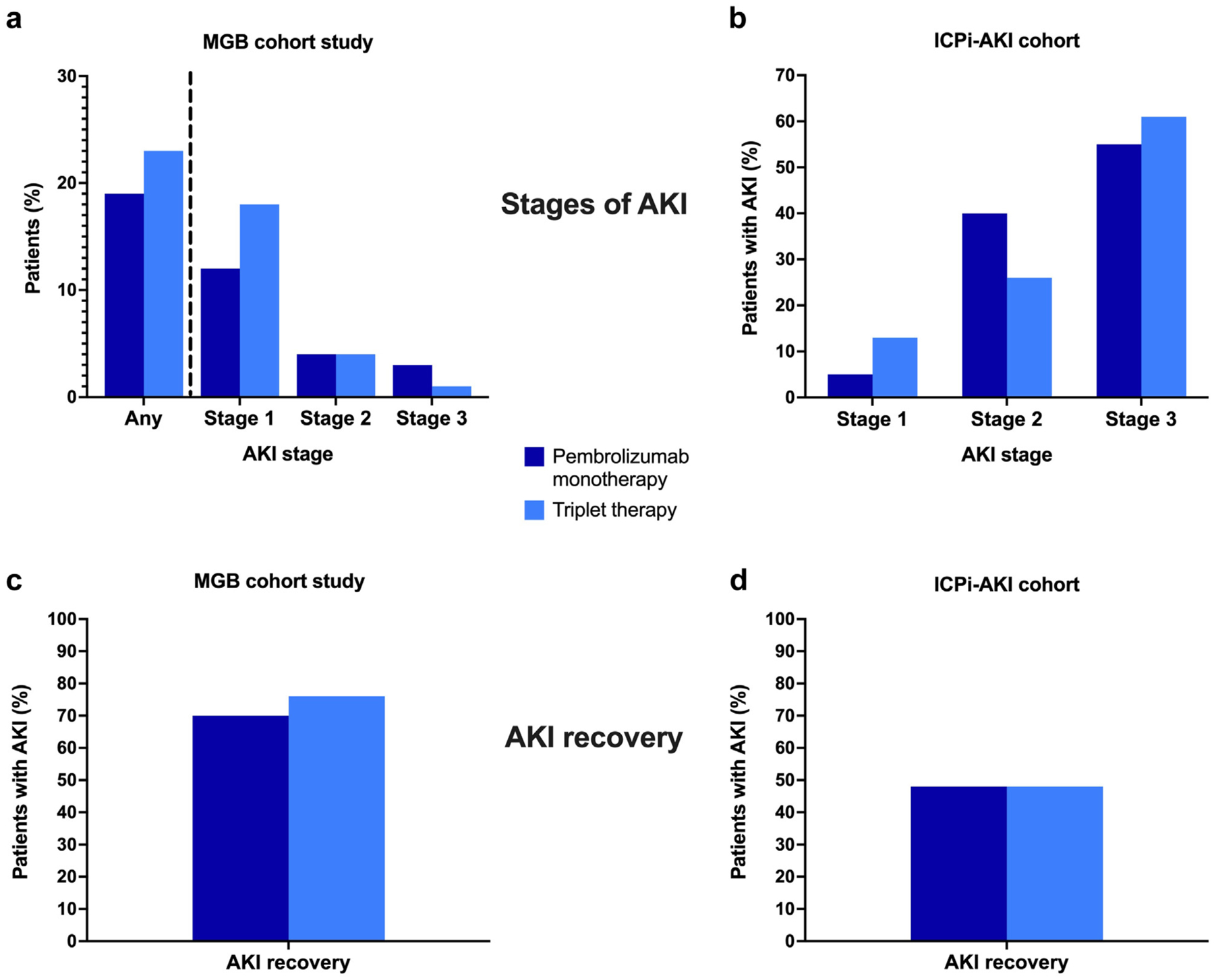

In the MGB cohort, 82 of 361 patients (23%) in the triplet therapy group developed AKI, as compared with 95 of 511 patients (19%) in the pembrolizumab monotherapy group (P = 0.16). The distribution of AKI stages 1, 2, and 3 was similar between the groups (Figure 1a). In multivariable analyses, the incidence of AKI was also similar between the groups (adjusted hazard ratio: 1.19 [95% confidence interval: 0.88–1.61]; P = 0.25; Table 2). Female sex was also a significant predictor of AKI risk (Supplementary Table S2). The timing of AKI did not differ significantly in the triplet group versus the pembrolizumab monotherapy group (median: 81 [interquartile range (IQR): 21–132] days vs. 70 [IQR: 28–126] days; P = 0.95; Table 1). AKI was attributed to ICPi therapy in 28% (27 of 95) of cases in the pembrolizumab monotherapy cohort, and in 31% (25 of 82) of cases in the triplet therapy cohort. The breakdown of AKI etiologies is shown in Supplementary Figure S2.

Figure 1 |. (a) Massachusetts General Brigham (MGB) cohort study with acute kidney injury (AKI) rates (any AKI incidence and breakdown of stages 1–3); (b) breakdown of the AKI stage in the immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated acute kidney injury (ICPi-AKI) cohort study; (c) AKI recovery rates in the MGB cohort; (d) AKI recovery rates in the ICPi-AKI cohort.

In the ICPi-AKI cohort, there was 1 patient in the triplet therapy group who received kidney replacement therapy (KRT) (4.4%) and was ultimately liberated from KRT, as compared with 2 patients in the pembrolizumab monotherapy group (5.0%) who received KRT, 1 of whom was liberated from KRT. In the MGB cohort, 2 patients received KRT, and neither was liberated from KRT.

Table 2 |.

Fine-Gray model for AKI within 6 months of initiation of triplet therapy or pembrolizumab monotherapy in the MGB cohort

| Univariate analysis | Multivariable model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P value | aHR | 95% CI | P value |

| Triplet therapy (vs. monotherapy) | 1.25 | 0.93–1.68 | 0.14 | 1.19 | 0.88–1.61 | 0.25 |

| Female | 2.17 | 1.59–2.96 | <0.01 | 2.41 | 1.76–3.30 | <0.01 |

| Age | 0.99 | 0.98–1.00 | 0.04 | 1.00 | 0.98–1.02 | 0.83 |

| Baseline eGFR (per 1 ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 1.02 | 1.01 −1.02 | <0.01 | 1.02 | 1.01–1.04 | <0.01 |

| BMI | ||||||

| 20–25 vs. <20 | 0.95 | 0.46–1.97 | 0.84 | — | — | — |

| 25–30 vs. <20 | 0.79 | 0.38–1.66 | 0.64 | — | — | — |

| ≥30 vs. <20 | 0.83 | 0.38–1.79 | 0.76 | — | — | — |

| Hypertension | 1.15 | 0.85–1.55 | 0.37 | — | — | — |

| Diabetes | 0.96 | 0.66–1.38 | 0.81 | — | — | — |

| Coronary artery disease | 1.49 | 1.10–2.02 | 0.01 | 1.44 | 1.03–2.02 | 0.03 |

| Cirrhosis | 0.74 | 0.12–4.52 | 0.75 | — | — | — |

| ACEI/ARBs | 1.39 | 1.04–1.87 | 0.03 | 1.63 | 1.19–2.22 | <0.01 |

| Diuretics | 1.13 | 0.83–1.53 | 0.44 | — | — | — |

| PPIs | 1.03 | 0.77–1.38 | 0.85 | — | — | — |

| Charlson comorbidity score | 1.04 | 0.99–1.09 | 0.15 | 1.05 | 0.99–1.11 | 0.13 |

aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; ACEI/ARB, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor blocker; AKI, acute kidney injury; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ICPi-AKI, immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated acute kidney injury; MGB, Massachusetts General Brigham; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

The Fine-Gray model takes into account the competing risk for death. The multivariable model evaluates the risk of AKI in patients treated with triplet versus monotherapy, adjusting for age, sex, baseline eGFR, coronary artery disease, Charlson comorbidity score, and ACEI/ARB use.

In the ICPi-AKI cohort, the distribution of AKI severity was similar in patients who received triplet therapy versus pembrolizumab monotherapy (Figure 1b). AKI occurred earlier in the triplet therapy group versus the pembrolizumab monotherapy group (median: 105 [IQR: 65–140] days vs. 202 [IQR: 128–315] days; P < 0.01; Table 1).

AKI treatment and kidney recovery

In the MGB cohort, there were no differences in corticosteroid use between triplet versus pembrolizumab monotherapy (Table 1). The rates of kidney recovery were also similar between the groups (84% and 78%; P = 0.39; Figure 1c), as was time to kidney recovery (median: 11 [IQR: 2–26] days vs. 10 [IQR: 2–29] days; P = 0.65). There was also no difference in corticosteroid use or recovery time for cases of AKI attributed to triplet therapy or pembrolizumab monotherapy (Supplementary Table S3).

In the ICPi-AKI cohort, 28 (44%) were hospitalized at the time of AKI. Corticosteroids were used more frequently in the ICPi-AKI cohort, with similar usage in patients receiving triplet therapy versus pembrolizumab monotherapy (Table 1). The rates of kidney recovery were similar between the groups (48% in both groups; P = 0.98; Figure 1d), as was time to kidney recovery (median: 46 [IQR: 22–56] days vs. 39 [IQR: 17–66] days; P = 0.98).

Histopathology

In the ICPi-AKI cohort, 12 of 23 patients (52%) who received triplet therapy and 8 of 63 patients (13%) who received pembrolizumab monotherapy underwent a kidney biopsy. Both groups had a similar proportion of moderate-to-severe acute interstitial nephritis; however, those receiving triplet therapy were more likely to have moderate-to-severe acute tubular necrosis versus those receiving pembrolizumab monotherapy (Supplementary Figures S3 and S4).

DISCUSSION

In 2 independent “real-world” cohorts consisting of nearly 1000 patients with nonsquamous NSCLC treated with triplet therapy or pembrolizumab monotherapy, we investigated the incidence and severity of AKI, and kidney recovery, along with associated clinical and histopathologic features. We found no significant difference in the incidence of AKI between these 2 treatment regimens. We also found no major differences in AKI severity, treatment, kidney recovery, or histopathologic findings among patients treated with these 2 regimens. Cumulatively, our findings suggest that triplet therapy does not pose a greater risk of kidney injury as compared with pembrolizumab monotherapy.

Clinical features of AKI were largely similar among patients who received triplet therapy versus pembrolizumab monotherapy; however, in the ICPi-AKI cohort, extrarenal immune-related adverse events were more common among patients receiving pembrolizumab monotherapy. This finding may reflect a greater likelihood of acute interstitial nephritis in the pembrolizumab monotherapy group.2,8

With regard to kidney recovery, we previously found that 64% of patients with all malignancies who developed ICPi-AKI had kidney recovery.2 In this study, rates of recovery were lower overall among patients with nonsquamous NSCLC (48%), but were similar between patients receiving triplet therapy versus pembrolizumab monotherapy. Pemetrexed has been associated with acute tubular necrosis and progressive kidney fibrosis,3,4,9 and despite concerns that the addition of pemetrexed to ICPis may increase the risk of AKI severity and decrease the likelihood of kidney recovery, our data are potentially reassuring that this may not be the case.

Although this study includes data from 2 cohorts, it has limitations. First, the MGB cohort included patients with any cause of AKI and thus captured milder stages of AKI, on average, than the multicenter ICPi-AKI cohort. In contrast, the ICPi-AKI cohort included patients with more severe AKI directly attributable to the ICPi, which likely explains the lower rates of kidney recovery and higher rates of corticosteroid use than in the MGB cohort. Second, we did not collect data on long-term kidney outcomes after AKI. Third, oncologists may have opted to treat older and more frail patients with pembrolizumab monotherapy rather than triplet therapy because of concern for toxicities; as a result, rates of AKI may have been lower in the triplet therapy group because of selection bias. However, neither age nor comorbidities have been demonstrated to be risk factors for ICPi-AKI.2,8 Furthermore, our multivariable model in the MGB cohort did not demonstrate an association between the treatment regimen and risk of AKI, though this may have been limited by lack of statistical power. Finally, as dexa-methasone is commonly administered with each cycle of triplet therapy but not with pembrolizumab monotherapy, this could potentially impact the risk of developing ICPi-associated AKI or other immune-related adverse events.

In summary, in 2 cohorts of patients with nonsquamous NSCLC, we found that AKI incidence, severity, and treatment, along with kidney recovery, do not differ between patients receiving triplet therapy versus pembrolizumab monotherapy. Given the nephrotoxic potential of combination therapy, these data are potentially reassuring to both nephrologists and oncologists managing patients on this regimen.

Supplementary Material

Table S1A. Extrarenal immune-related adverse events prior to onset of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICPi)–associated acute kidney injury (AKI).

Table S1B. Extrarenal immune-related adverse events concomitant with immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICPi)–associated acute kidney injury (AKI).

Table S2. Rate of acute kidney injury (AKI) by sex in the Massachusetts General Brigham (MGB) cohort.

Table S3. Characteristics of acute kidney injury (AKI) in patients with therapy-induced AKI in the Massachusetts General Brigham (MGB) cohort.

Figure S1. Patient flowchart for the Massachusetts General Brigham (MGB) and immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICPi)–associated acute kidney injury (AKI) cohorts.

Figure S2. Etiology of acute kidney injury (AKI) cases in the Massachusetts General Brigham (MGB) cohort.

Figure S3. Kidney biopsy findings in pembrolizumab monotherapy versus triplet therapy.

Figure S4. Representative pathology findings in triplet therapy (A,B) and pembrolizumab monotherapy (C,D).

DISCLOSURE

SG receives research funding from GE Healthcare and BTG International and is president and founder of the American Society of Onconephrology. KDJ is a consultant for Astex Pharmaceuticals, Natera, GlaxoSmithKline, ChemoCentryx, and Chinook; a paid contributor to Uptodate.com; receives honorarium from the International Society of Nephrology and the American Society of Nephrology; and is cofounder and copresident of the American Society of Onconephrology. DSS participates in the speakers’ bureau at Genentech. FBC is a consultant for ChemoCentryx and Retrophin. AA is supported by the Division of Internal Medicine Immuno-Oncology Toxicity Award Program of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. BS is a senior clinical investigator at the Research Foundation Flanders (F.W.O.) (1842919N) and is supported by Stichting tegen Kanker (grant C/2020/1380). AR is a consultant for Otsuka Pharmaceutical Company and treasurer of the American Society of Onconephrology. SMH is supported by the Mayo Clinic K2R award. KB receives grant support from the Olympia Morata Programme, Foundations Commission of University of Heidelberg, Rheumaliga Baden-Württemberg e.V., Abbvie, and Novartis; and also serves as a consultant for and receives speaker fee/travel reimbursements from Abbvie, BMS, Janssen, MSD, Viatris, Gilead/Galapagos, Janssen, Lilly, Medac, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Union Chimique Belge. MES has served on a scientific advisory board for Mallinckrodt. MJM has served as a consultant or received honorarium from AstraZeneca, Immunai, Istari Oncology, Nektar Therapeutics, and Bristol Myers Squibb. LC serves as a consultant for and receives honorarium and/or travel reimbursements from Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, and MSD. All other authors declared no competing interests.

APPENDIX

ICPi-AKI Consortium collaborators

Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP), Sorbonne Université, Hôpital Pitié-Salpêtrière: Luca Campedel, Joe-Elie Salem, and Corinne Isnard Bagnis; Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Dana-Farber Cancer Institute: Shruti Gupta, David E. Leaf, Harkarandeep Singh, Shveta S. Motwani, Naoka Murakami, Maria C. Tio, Suraj S. Mothi, Umut Selamet, and Astrid Weins; Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin: Sebastian Loew and Kai M. Schmidt-Ott; Chi-Mei Medical Center: Weiting Chang; Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine: Kenar D. Jhaveri, Rimda Wanchoo, Yuriy Khanin, Jamie S. Hirsch, Vipulbhai Sakhiya, Daniel Stalbow, and Sylvia Wu; Duke University Medical Center: David I. Ortiz-Melo; Guy’s and St. Thomas NHS Hospital: Marlies Ostermann, Nuttha Lumlertgul, Nina Seylanova, Armando Cennamo, Anne Rigg, and Nisha Shaunak; Harvard Medical School: Zoe A. Kibbelaar; Heidelberg University Hospital: Karolina Benesova; Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital: Priya Deshpande; Massachusetts General Hospital: Meghan E. Sise, Kerry L. Reynolds, Harish S. Seethapathy, Meghan Lee, Ian A. Strohbhen, Meghan J. Mooradian, Paul E. Hanna, Qiyu Wang, and Rituvanthikaa Seethapathy; Mayo Clinic: Sandra M. Herrmann and Busra Isik; Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center: Ilya G. Glezerman; New York Nephrology Vasculitis and Glomerular Center: Frank B. Cortazar; Northwestern University: Vikram Aggarwal and Sunandana Chandra; Ohio State University: Jason M. Prosek, Sethu M. Madhavan, Dwight H. Owen, and Marium Husain; Sheba Medical Center: Pazit Beckerman and Sharon Mini; Stanford University School of Medicine: Shuchi Anand, Pablo Garcia, and Aydin Kaghazchi; University of Alabama at Birmingham: Sunil Rangarajan; University of California-Los Angeles: Daniel Sanghoon Shin and Grace Cherry; University of California-San Francisco: Christopher A. Carlos, Raymond K. Hsu, and Andrey Kisel; University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center: Arash Rashidi, Sheru K. Kansal, Nicole Albert, Katherine Carter, Vicki Donley, Tricia Young, and Heather Cigoi; University Hospital of Geneva: Sophie De Seigneux and Thibaud Koessler; University Hospitals Leuven: Ben Sprangers and Els Wauters; University of Florida: Chintan V. Shah; University Medical Center Groningen: Mark Eijgelsheim; University of Miami Miller School of Medicine: Zain Mithani, Javier A. Pagan, and Yiqin Zuo; University of Pennsylvania Health System: Gaia Coppock and Jonathan J. Hogan; University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center: Ala Abudayyeh, Omar Mamlouk, Jamie S. Lin, and Valda Page; University of Toronto: Abhijat Kitchlu; University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine: Samuel A.P. Short; University of Virginia Health System: Amanda D. Renaghan and Elizabeth M. Gaughan; University of Washington: A. Bilal Malik; Vall d’Hebron University Hospital: Maria Jose Soler, Clara García-Carro, Sheila Bermejo, Enriqueta Felip, Eva Muñoz-Couselo, and Maria Josep Carreras.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Gandhi L, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2078–2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta S, Short SAP, Sise ME, et al. Acute kidney injury in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9: e003467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glezerman IG, Pietanza MC, Miller V, Seshan SV. Kidney tubular toxicity of maintenance pemetrexed therapy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58: 817–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Visser S, Huisbrink J, van ‘t Veer NE, et al. Renal impairment during pemetrexed maintenance in patients with advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer: a cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2018;52:1800884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Motwani SS, McMahon GM, Humphreys BD, et al. Development and validation of a risk prediction model for acute kidney injury after the first course of cisplatin. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:682–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu K, Qin Z, Xu X, et al. Comparative risk of renal adverse events in patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors: a Bayesian network meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 2021;11:662731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cortazar FB, Kibbelaar Z, Glezerman IG, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated AKI: a multicenter study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31:435–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dumoulin DW, Visser S, Cornelissen R, et al. Renal toxicity from pemetrexed and pembrolizumab in the era of combination therapy in patients with metastatic nonsquamous cell NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15:1472–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1A. Extrarenal immune-related adverse events prior to onset of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICPi)–associated acute kidney injury (AKI).

Table S1B. Extrarenal immune-related adverse events concomitant with immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICPi)–associated acute kidney injury (AKI).

Table S2. Rate of acute kidney injury (AKI) by sex in the Massachusetts General Brigham (MGB) cohort.

Table S3. Characteristics of acute kidney injury (AKI) in patients with therapy-induced AKI in the Massachusetts General Brigham (MGB) cohort.

Figure S1. Patient flowchart for the Massachusetts General Brigham (MGB) and immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICPi)–associated acute kidney injury (AKI) cohorts.

Figure S2. Etiology of acute kidney injury (AKI) cases in the Massachusetts General Brigham (MGB) cohort.

Figure S3. Kidney biopsy findings in pembrolizumab monotherapy versus triplet therapy.

Figure S4. Representative pathology findings in triplet therapy (A,B) and pembrolizumab monotherapy (C,D).