Abstract

The tumor microenvironment (TME) plays a key role in the poor prognosis of many cancers. However, there is a knowledge gap concerning how multicellular communication among the critical players within the TME contributes to such poor outcomes. Using epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) as a model, we show how crosstalk among cancer cells (CC), cancer associated fibroblasts (CAF), and endothelial cells (EC) promotes EOC growth. We demonstrate here that co-culturing CC with CAF and EC promotes CC proliferation, migration, and invasion in vitro and that co-implantation of the three cell types facilitates tumor growth in vivo. We further demonstrate that disruption of this multicellular crosstalk using a gold nanoparticle (GNP) inhibits these pro-tumorigenic phenotypes in vitro as well as tumor growth in vivo. Mechanistically, GNP treatment reduces expression of several tumor-promoting cytokines and growth factors, resulting in inhibition of MAPK and PI3K-AKT activation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition - three key oncogenic signaling pathways responsible for the aggressiveness of EOC. The current work highlights the importance of multicellular crosstalk within the TME and its role for the aggressive nature of EOC, and demonstrates the disruption of these multicellular communications by self-therapeutic GNP, thus providing new avenues to interrogate the crosstalk and identify key perpetrators responsible for poor prognosis of this intractable malignancy.

Keywords: Cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF); Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT); Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC); Gold nanoparticle (GNP, AuNP); Tumor microenvironment (TME)

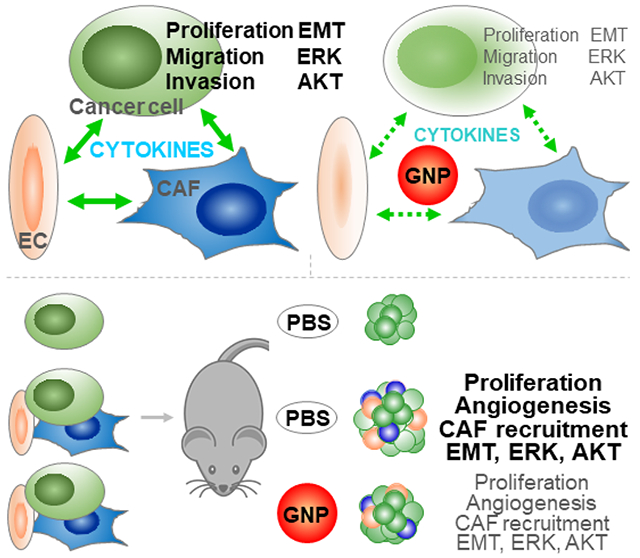

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Gold nanoparticles (GNP) have demonstrated intrinsic therapeutic potential in a variety of disease models [1]. Using cancer cells (CC) only models, GNP were found to act directly on CC to inhibit the survival, growth, and metastasis of cancers of the breast [2], cervix [3], ovary [4], pancreas [5] and prostate [6], as well as leukemia [7], melanoma [8], multiple myeloma [9] and osteosarcoma [10] (Fig 1). GNP transformed activated cancer associated fibroblasts (CAF), an important cell type in the tumor microenvironment (TME) [11], to quiescence by disturbing lipid metabolism [12]. GNP also exhibited antiangiogenic properties, both in vitro and in vivo, by either inducing autophagy in endothelial cells (EC), another important cell type in the TME, or inhibiting several proangiogenic factors [13, 14], thus contributing to block ovarian tumor progression [4]. In CC-CAF co-implantation models, GNP inhibited growth of both pancreatic and oral tumors by disrupting CC-CAF crosstalk [4, 5, 15]. Additionally, GNP inhibited CAF activation by obstructing their communications with CC, EC and CAF [16]. Mechanistically, when introduced into a biological system, GNP can rapidly adsorb biomolecules to form a dynamic protein corona on the surface, and further bind, deform and inhibit numerous growth factors, such as PDGF (platelet derived growth factor), bFGF (basic fibroblast growth factor) and VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) [4, 5, 15, 17, 18]. Based on these observations, as well as their ability to easily access the TME [19], GNP could be a potential effective therapeutic candidate to simultaneously target CC, CAF and EC, as well as multiple signaling pathways initiated by multicellular communications within TME. This kind of therapeutic agent, or multi-target drug, could be more potent than the single-target drug by eliciting synergistic effects and various antitumor mechanisms, and bring more clinical benefits [20].

Fig 1.

Potential, necessity and strategy to target multicellular communications in the TME by GNP. (A) The intrinsic tumor therapeutic potential of GNP has been demonstrated in CC, CAF or EC single-cell models, as well as CC-CAF, CC-EC, or CAF-EC two-cell bidirectional crosstalk models. (B) The impact of the triangular crosstalk among CC, CAF, and EC on tumor progression, desmoplasia and angiogenesis is not clear, nor is the effect of GNP on the crosstalk. (C) This study investigated the triangular crosstalk using ovarian cancer models and evaluated GNP as a potential multi-target agent.

The TME is the biological and biochemical milieu surrounding CC. The major TME constituents range from tissues to molecules, including vasculature, nerves, CAF, EC, immune cells, and signaling molecules [21, 22]. The highly reactive TME and its communication with CC play key roles in tumor progression and therapeutic response [23, 24]. Active desmoplasia and angiogenesis are two main features of the reactive TME, and both are associated with increased aggressiveness and poor prognosis in multiple cancers [23, 24]. CAF are the principal desmoplastic effector cells, and as such promote tumor growth, angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis (Fig 1). CAF enable CC to escape both immune surveillance and therapeutic attack by secreting soluble factors, exchanging metabolites with CC, releasing immunosuppressive cytokines, and reducing drug receptors on CC [25, 26]. EC are the principal angiogenic effector cells, as such they form blood vessels that provide tumors with oxygen and nutrients as well as routes for metastasis. Also, EC secrete molecules such as IL-6, EGF, Jagged-1 and FGF2 to directly promote CC growth and induce epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), stem cell phenotype, and docetaxel resistance [27–30]. Likewise, CC, by releasing cytokines and growth factors such as TGFβ, PDGF, FGF2, VEGF and ANGPT2, activate CAF and EC, thus promoting desmoplasia and angiogenesis [31, 32]. Additionally, the crosstalk between CAF and EC reciprocally activates both cell types [16, 26, 32]. Despite the knowledge about all the bidirectional crosstalk, the possible triangular crosstalk among CAF, EC and CC, its impact on tumor progression and its role as a therapeutic target, remains inadequately investigated and understood. Importantly, effective strategies to interrogate multicellular crosstalk within the TME and identify key mediators of the communications are lacking. In this context, the self-therapeutic property of GNP, due to their ability to bind and inhibit a number of protumorigenic molecules, provides unique opportunities to investigate the TME and determine specific mediators in an unbiased manner.

High-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC) and undifferentiated carcinoma (UC) respectively represent the most common type and the type with the worst prognosis among the epithelial ovarian cancers (EOC), to which CAF, EC and their derived cytokines impose a pro-tumorigenic microenvironment [33–35]. In this study (Fig 1), using the typical HGSC and UC cell lines OV90 and A2780-CP20 (hereafter termed CP20) as EOC models [36–38], human microvascular endothelial cells (HMEC) and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) as EC models, and the TAF18 cell line as a primary ovarian CAF model [39], we investigated the impact of CC-CAF-EC triangular crosstalk on tumor aggressiveness. We further investigated the effects of 20 nm diameter GNP on both the crosstalk and the malignancy, as well as on the underlying molecular mechanisms.

Results

GNP Preparation and Characterization

We previously reported the effect of GNP of different size (5, 10, 20, 50, or 100 nm in diameter) on the proliferation of a variety of cell lines. GNP of 20 nm exhibited the greatest efficacy in inhibiting the growth of ovarian CC lines SKOV3, A2780 and OVCAR5. In addition, 20 nm GNPs more effectively inhibited growth factor induced proliferation of fibroblasts and EC than GNP of other sizes [4, 18]. Thus, we prepared 20 nm GNP with the citrate reduction method and used them in this study [18]. Physicochemical characterization of the synthesized GNP with UV-visible spectroscopy gave a surface plasmon resonance (SPR) band at around 521 nm, indicating successful formation of GNP (Fig S1A). Hydrodynamic diameter and surface charge of the GNP was determined to be 23.9 nm (Fig S1B) and −41.9 mV (Fig S1C) by dynamic light scattering and zeta potential measurement, respectively. The shape and size of the GNP was further validated by transmission electron microscopy, which confirmed the formation of spherical GNP of approximately 20 nm in diameter (Fig S1D).

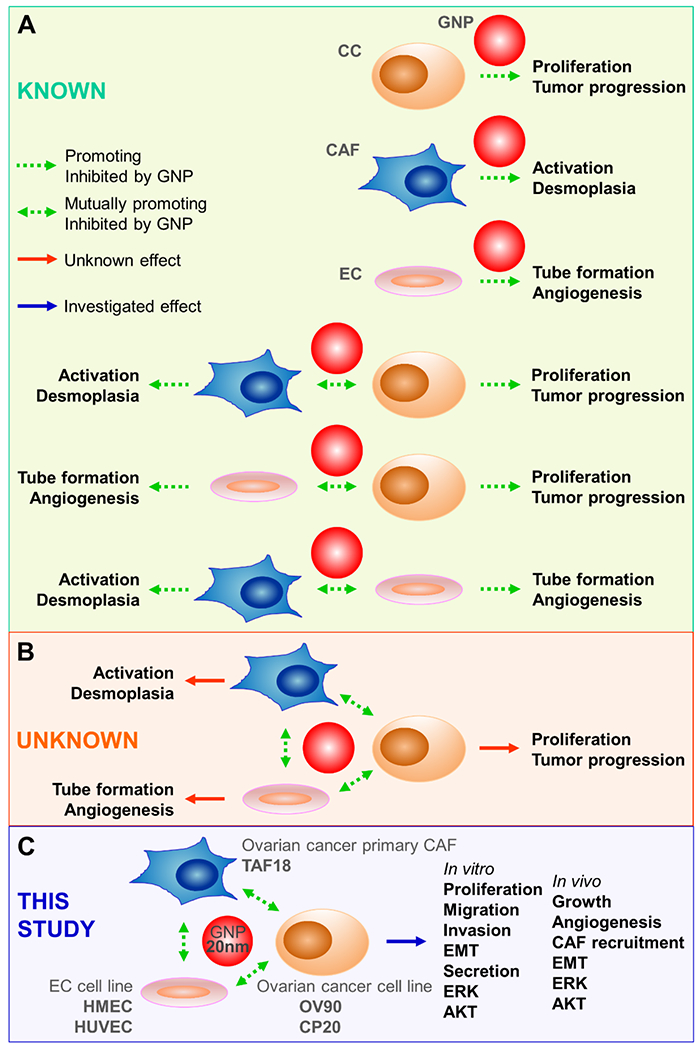

Cocultured CAF and EC promoted CC proliferation

We recently reported that the conditioned media (CM) from ovarian CC (CP20, OV90, OVCAR4), ovarian CAF (TAF18, TAF19) and EC (HMEC, HUVEC) induce morphological changes, migration, and activation markers of the CAF via the TGFβ1, PDGF, uPA and TSP1 pathways [16]. These CM also promote tube formation and migration of the EC by VEGF-VEGFR2 signaling [39]. The molecular crosstalk among the three cell types and its impact on tumor aggressiveness, however, has not been studied. To reveal the impact of the tri-cellular crosstalk on CC, we initially co-cultured all three cell types together, so that signaling due to either secretory factors or direct cell-cell contact could not be overlooked at the outset, and measured cell proliferation. Antecedently, to clearly distinguish CC, we generated EGFP-expressing derivatives of CP20 (CP20-EGFP) and OV90 (OV90-EGFP). EGFP fluorescence at 488 nm was confirmed and was directly proportional to cell number; thus, fluorescence directly reflected the number of CC and was used as a readout for cell proliferation in coculture (Fig 2A). To determine whether CAF and EC promoted CC proliferation, varying numbers of cells were seeded in complete mixed medium (complete mixed media was a 1:1:1 mixture of individual complete media for CC, CAF and EC in order to support all cell types well). Twenty-four hours after cell seeding, the complete mixed medium was replaced with serum-free mixed medium to eliminate the influence of FBS on cellular phenotype. Cell state and growth were checked daily by microscopy. All cells looked healthy and grew steadily, except the individually cultured TAF18 and HUVEC which stopped growing upon withdrawal of FBS. Experiments were terminated at day 7, cells were imaged, and fluorescence was measured (Fig 2B, C). Fig 2A and Fig 2C show that autofluorescence from all wild type cells was minimal (Groups 11-14 for CP20 composition and 12-15 for OV90 composition). Both quantitative fluorescence measurements and fluorescence images showed that TAF18 and HUVEC, either individually or in combination, promoted CC proliferation. The CC proliferation positively associated with the numbers of TAF18 and HUVEC seeded to the cocultures. It is evident that the presence of TAF18 and HUVEC together promoted CC growth more effectively than either single TAF18 or single HUVEC. It is also evident that specific CC:CAF:EC ratios facilitated optimal CC growth, with 1:1:2 (Group 5) or 1:2:1 (Group 10) for CP 20 and 2:1:4 (Group 6) or 1:1:1 (Group 11) for OV90. These results indicate that the triangular crosstalk among CC, CAF, and EC stimulates CC growth and facilitates CC aggressiveness more effectively than the CC-CAF and CC-EC bidirectional crosstalk, suggesting the usefulness of the three-cell model in investigating TME.

Fig 2.

Coculture with CAF and EC promotes CC growth. (A) Specified numbers of CP20-EGFP, OV90-EGFP or wild type (WT) CP20 were seeded to 96-well plates. OD 488 was read the next day. (B) TAF18, HUVEC, and CP20-EGFP, OV90-EGFP, CP20-WT or OV90-WT cells were seeded, together or separately, to 96-well plates with the composition and number indicated in the table. Cells were grown in serum-free medium. Images were taken 7 days after seeding. In the table: CP20=CP20-EGFP, OV90=OV90-EGFP, WT=CP20 WT or OV90 WT. (C) Cells were trypsinized after imaging with 30 μl trypsin/well, resuspended in 200 μl PBS, and OD488 was read 30 min later. Experiments were performed in sextuplicate and repeated 3 times. *, p<0.05, compared to group 1. Scale bar: 100 μm.

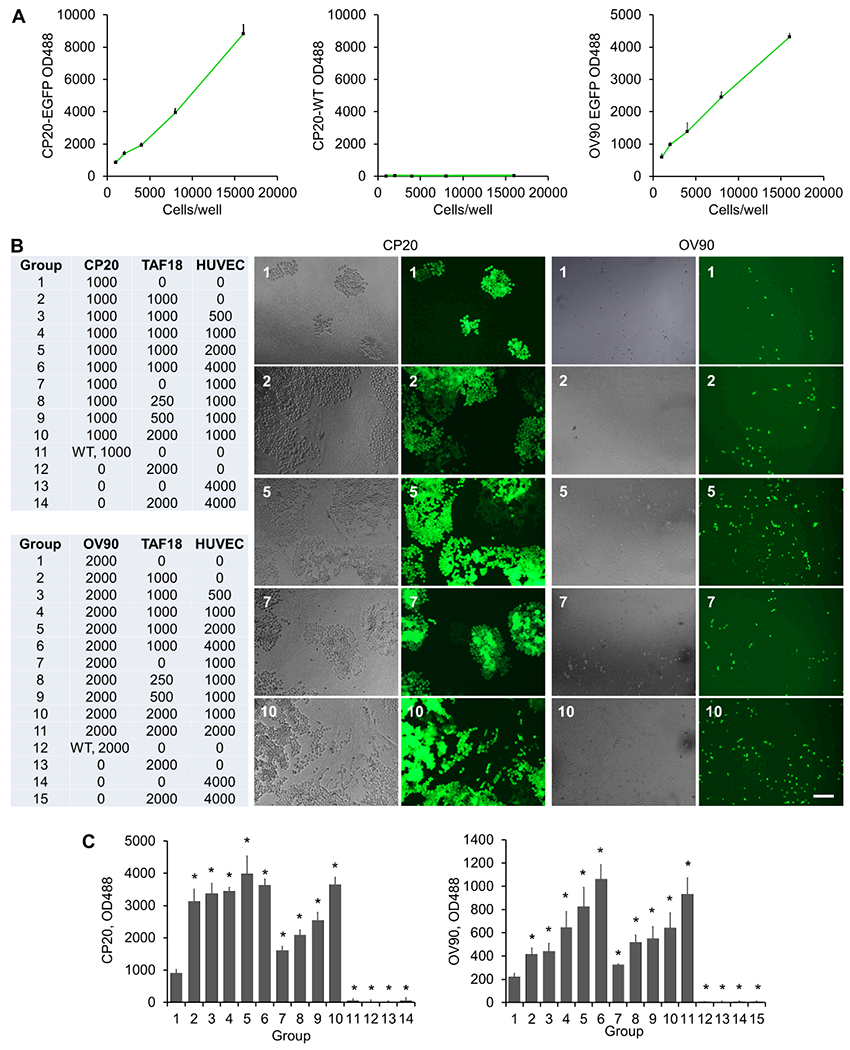

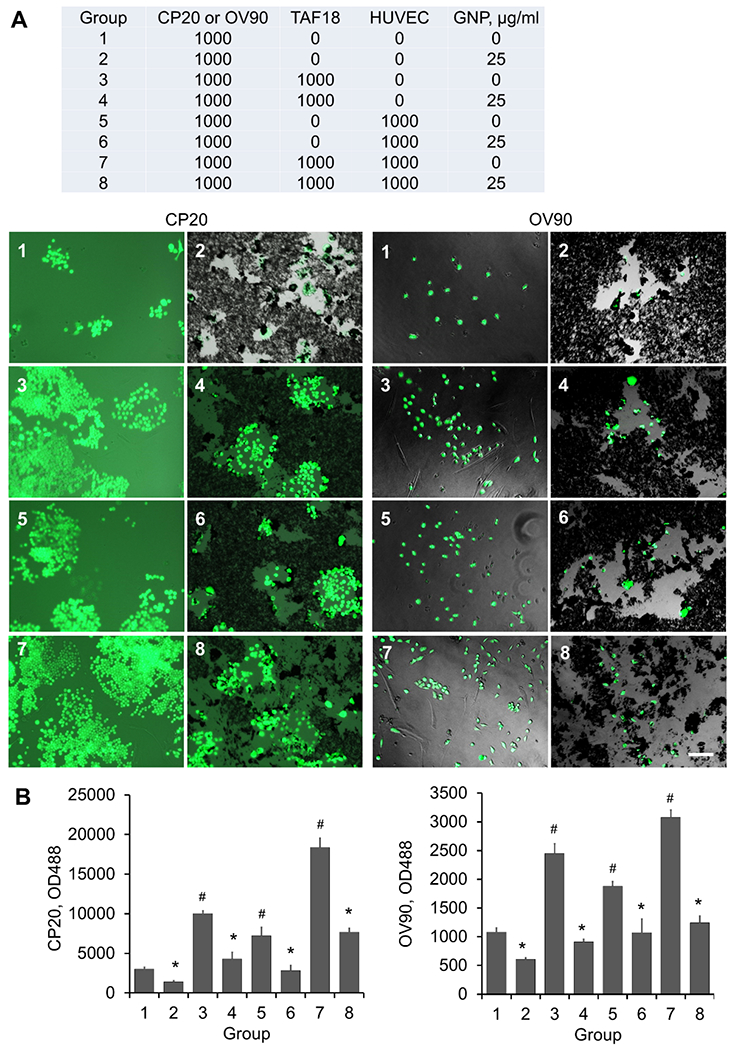

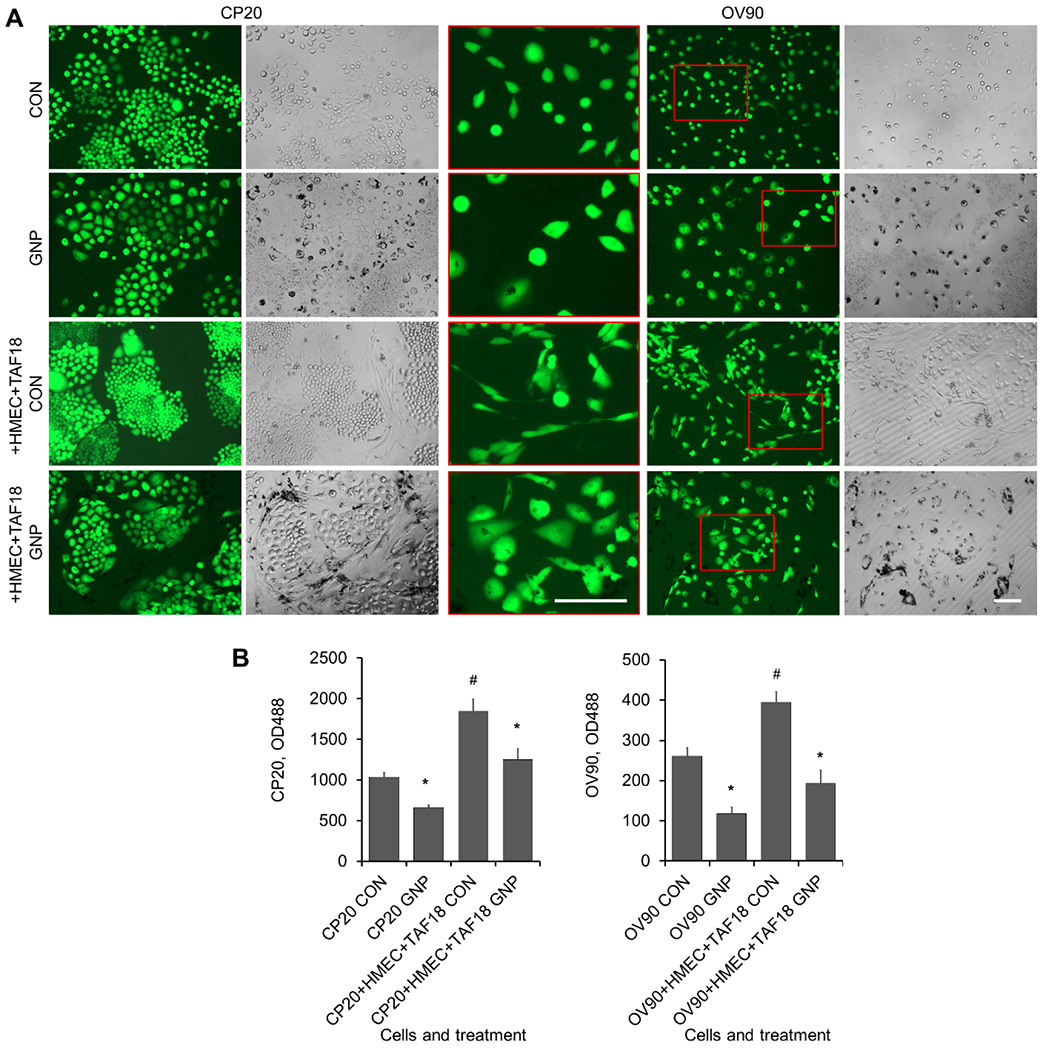

GNP inhibited the growth of CC cocultured with EC and CAF

We demonstrated in our recent work that GNP inhibit CAF activation by disrupting CC-CAF, EC-CAF, and CAF-CAF signaling [16], and that GNP inhibit EC angiogenesis by disturbing CC-EC, CAF-EC, and EC-EC communication [39]. We show above that the multicellular communication among CC, CAF and EC promoted CC growth (Fig 2). Based on these findings, we investigated whether GNP, due to their self-therapeutic properties, can also disrupt this triangular crosstalk. GNP were added to CC-CAF-EC cocultures, and CC proliferation was monitored by measuring fluorescence (Fig 3). According to the results shown in Fig 2B, C, we seeded the same number (1000 cells/well) of CAF or/and EC with CC. The complete medium was replaced with serum-free mixed medium 24 h after cell seeding, followed by GNP treatment for 7 days. We reported previously that GNP at 20 μg/ml (among 5, 10 and 20 μg/ml) most effectively inhibited the growth of ovarian CC lines SKOV3, A2780, and OVCAR5 [4]. GNP at 25 μg/ml (among 5, 10, 25 and 50 μg/ml) effectively inhibited the growth of pancreatic CC lines AsPC1 and Panc1, and pancreatic CAF cell lines CAF19 and iTAF [5]. Thus, we used GNP at 25 μg/ml and found this dose significantly inhibited the proliferation of CP20-EGFP or OV90-EGFP co-cultured with TAF18, HUVEC (Fig 3A, B), or HMEC (Fig 4A, B) alone, or the combination of TAF18 and EC. These results suggested that GNP may interrupt the triangular crosstalk among CC, CAF, and EC. Moreover, either coculture or GNP treatment caused morphological changes to CC (Fig 4A). Some CP20-EGFP and OV90-EGFP cocultured with TAF18 and HMEC looked smaller, while some cells treated with GNP became bigger and better spread, two days after coculture or treatment. Noticeably, relatively more OV90-EGFP cells in coculture displayed fibroblast-like morphology compared to monoculture, whereas relatively fewer exhibited such changes upon GNP treatment (Fig 4A). These observations suggest that the cells may undergo EMT or the reverting mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET). We therefore investigated if the triangular crosstalk among CC, CAF and EC promotes CC migration and invasion, two key EMT functional phenotypes that demonstrate aggressiveness of CC, and whether GNP treatment can blunt such aggressive phenotypes.

Fig 3.

GNP inhibit proliferation of CC cocultured with CAF and HUVEC. (A) TAF18, HUVEC, and CP20-EGFP or OV90-EGFP cells were seeded, together or separately, to 96-well plates with the composition and number indicated in the table. Cells were grown in serum-free medium. Cells were treated with 25 μg/ml GNP or PBS 16 h after seeding. Images were taken 7 days after seeding. In the table: CP20=CP20-EGFP, OV90=OV90-EGFP. (B) Cells were trypsinized after imaging with 30 μl trypsin/well, resuspended in 200 μl PBS, and OD488 was read 30 min later. Experiments were performed in sextuplicate and repeated 3 times. *, p<0.05, compared to corresponding control. #, p<0.05, compared to group 1. Scale bar: 100 μm.

Fig 4.

GNP alter growth and morphology of CC cocultured with CAF and HMEC. (A) CP20-EGFP or OV90-EGFP cells, alone or with TAF18 and HMEC cells, were seeded to 96-well plates; 1000 cells/well of each cell type. Cells were grown in serum-free medium. Cells were treated with 25 μg/ml GNP or PBS 16 h after seeding. Images were taken 7 days after seeding. The amplified inserts (in red box) highlight OV90 cell morphology. (B) Cells were trypsinized after imaging with 30 μl trypsin/well, resuspended in 200 μl PBS, and OD488 was read 30 min later. Experiments were performed in sextuplicate and repeated 3 times. *, p<0.05, compared to corresponding control. #, p<0.05, compared to CP20 CON or OV90 CON. Scale bar: 100 μm.

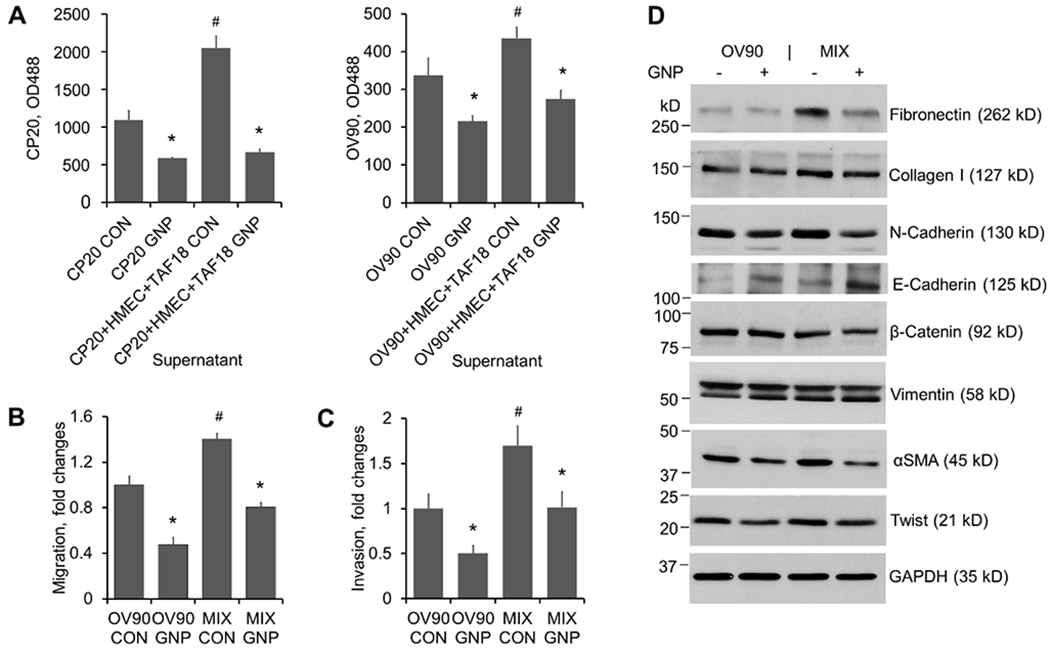

Supernatants of cultures treated with GNP inhibited CC proliferation, migration, invasion and EMT

The cellular secretome is a major mediator of cell communication [40]. Previously, we demonstrated that GNP disrupts communication between pancreatic CC and stellate cells by altering their cell secretomes [5]. Therefore, herein, we checked whether the phenotype changes observed above (Fig 4) were at least partially mediated by the corresponding secretomes. To model the cell secretomes, we collected serum-free supernatants, i.e. CM, from the cocultures of CC, TAF18, and HMEC (equal numbers for each cell type were seeded) and from the CC monocultures that were incubated with or without 25 μg/ml GNP for two days. We then used the CM to treat CC for three days, and compared their growth. We found that the coculture CM, as compared to the monoculture CM, stimulated the proliferation of CC significantly more. The CM from GNP-treated monocultures or cocultures, as compared to the PBS-treated (Control) counterparts, exhibited less stimulatory effect (Fig 5A). The proliferation changes mediated by the CM (Fig 5A) were comparable to those mediated by the comprehensive communication (Fig 4B). These results clearly indicated that the cell secretome plays a critical role in inducing the growth of CC.

Fig 5.

Supernatants of cultures treated with GNP inhibit CC proliferation, migration, invasion and EMT. CM preparation: 5x105 CP20-EGFP or OV90-EGFP cells were seeded to 10 cm dishes with or without HMEC and TAF18 of equal numbers. Cells were starved from the next day for 16 h and then treated with 25 μg/ml GNP or PBS in fresh serum-free media for 2 days. Supernatants were collected and centrifuged to remove cell debris and GNP. (A) Proliferation: CP20-EGFP or OV90-EGFP cells were seeded at 1000 cells/well to 96-well plates. The following day the CM were added to plates and incubated for 3 days. EGFP fluorescence intensity was measured after treatment. Experiments were performed in sextuplicate and repeated 3 times. (B) Migration: OV90-EGFP (designated as OV90 hereafter) cells (8x104 cells) were seeded to each transwell. Migration was induced by CM added to the outwells for 16 h. Experiments were performed in duplicate and repeated 3 times. (C) Invasion: OV90 cells (1x105 cells) were seeded to each Matrigel precoated transwell. Invasion was induced by CM added to the outwells for 24 h. Experiments were performed in duplicate and repeated 3 times. (D) EMT marker expression change upon CM treatment. OV90 cells were treated for 2 days with CM from OV90 alone or from the OV90, TAF18 and HMEC cocultures (MIX) incubated with or without GNP. Proteins (5 μg- 50 μg) in cell lysates were separated with 6% or 12% SDS-PAGE. GAPDH was used as loading control. Experiments were repeated 3 times. *, p<0.05, compared to corresponding control. #, p<0.05, compared to CP20 CON or OV90 CON.

Next, we investigated the stimulatory effect of coculture CM on the migration and invasion of OV90-EGFP cells (designated as OV90 hereafter). The CM from coculture (equal numbers for OV90, TAF18, and HMEC, for clarity designated as “MIX” hereafter) induced more migration and invasion than did the CM from CC monoculture, whereas CM from GNP-treated cultures inhibited CC motility more compared to CM from Control (Fig S2, Fig 5B, C). Since EMT is a dynamic process by which CC loosen their cell-cell junctions and gain migratory, invasive, and metastatic properties [41], and we already observed the related morphological (Fig 4A) and functional changes (Fig S2, Fig 5B, C), we next sought to confirm that EMT was implicated in the coculture-induced or GNP-inhibited cell motility by examining the molecular marker changes. Indeed, treatment of OV90 with the coculture CM upregulated the expression of Fibronectin, Collagen I, N-cadherin, αSMA and Twist as compared to treatment with the monoculture CM (Fig 5D). Importantly, these EMT markers were downregulated when OV90 were treated with CM from GNP-treated cultures. Furthermore, OV90 treated with CM from GNP-treated culture exhibited upregulated expression of E-cadherin, a marker for epithelial transition. These results suggest that the CM from coculture contains key mediators for CC proliferation, EMT, migration, and invasion. These aggressive potentials can be suppressed by GNP via altering the cellular secretome that mediates multicellular communication. Thus, we next tried to identify the key molecules in the secretome that are responsible for endowing CC with the aggressive potential and for the impact of GNP on this potential, as well as the key intracellular signaling in CC.

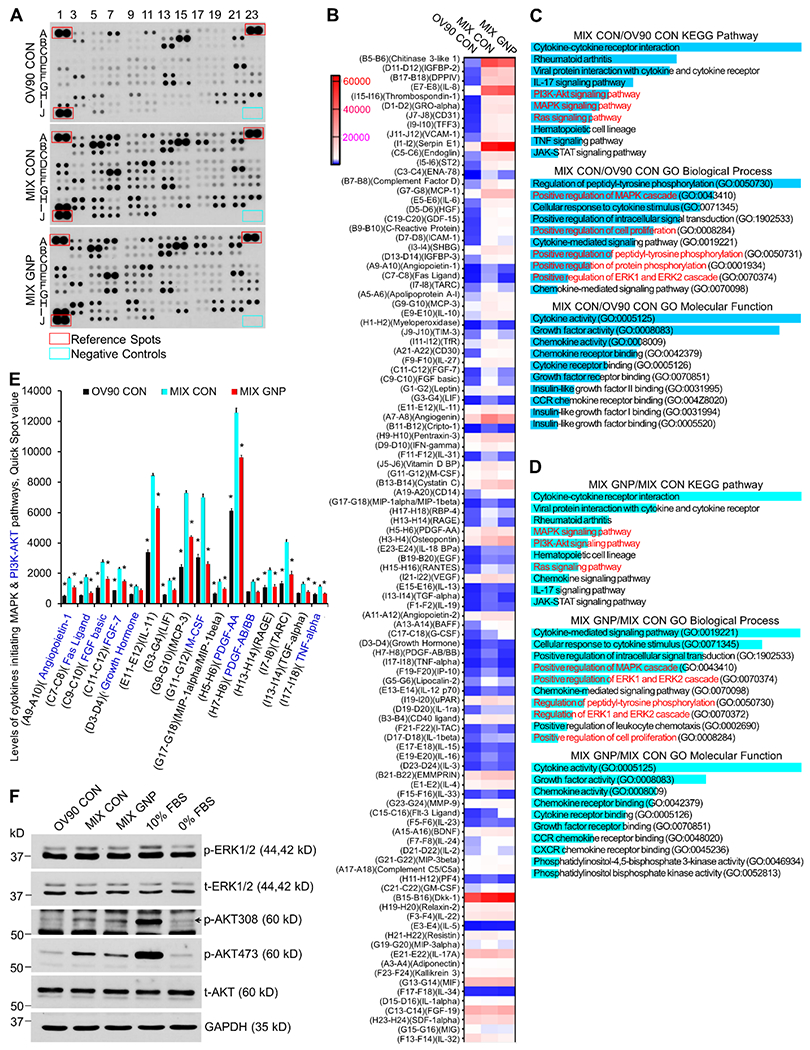

GNP decreased levels of cytokines that initiate MAPK and PI3-AKT pathways leading to CC proliferation and EMT

CM from OV90 monoculture treated with PBS, and cocultures (equal numbers of OV90, TAF18 and HMEC) treated with either PBS or 25 μg/ml GNP for two days were collected as described above (for clarity in figure labeling, these CM were designated as OV90 CON, MIX CON, and MIX GNP, respectively). The CM were subjected to antibody-based cytokine array to determine the expression of 105 cytokines and growth factors that mediate cell communication (Fig 6A). Blot images were converted to values using the Quick Spot image analysis tool according to the array usage directions. Values were then manually adjusted based on spot area and intensity (Tab S1). An expression heatmap of the cytokines was drawn, by ranking the ratio of the coculture control to the OV90 control (highest top, Fig 6B). We used Enrichr, a web-based tool for gene set enrichment analysis and annotation [42], to analyze the expression data. To get meaningful information, we input the valid gene symbols of the 79 cytokines with ≥ 1.5-fold changes (p < 0.1) between the two control cultures (ratio of MIX CON / OV90 CON or OV90 CON / MIX CON ≥ 1.5) (Tab S2) to Enrichr. KEGG pathway results showed that: (1) PI3K-AKT (phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase - protein kinase B), (2) MAPK (mitogen activated protein kinase) and (3) Ras signaling pathways (Fig 6C, Tab S3) were among the top 10 relevant and significantly altered (P < 0.001) pathways. Gene Ontology (GO) Biological Process results showed that: (1) positive regulation of MAPK cascade, (2) positive regulation of cell proliferation, (3) positive regulation of protein phosphorylation, and (4) positive regulation of ERK1 (extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1) and ERK2 cascades (Fig 6C, Tab S4) were among the top 10 relevant and significantly altered (P < 0.001) processes. GO Molecular Function results classified: (1) cytokine activity and receptor binding, (2) growth factor activity and receptor binding, and (3) chemokine activity and receptor binding (Fig 6C, Tab S5) as among the top 10 relevant and significantly altered (P < 0.01) functions.

Fig 6.

GNP inhibit the MAPK and PI3-AKT signaling pathways by altering the coculture secretome. (A) CM from coculture treated with 25 μg/ml GNP (MIX GNP) or PBS (MIX CON), and CM from OV90 treated with PBS (OV90 CON) were collected and subjected to cytokine antibody array assays. Experiments were performed twice with similar results. Shown is a typical blot. (B) Blot images were quantified with Quick Spot image analysis tool. Values were further manually adjusted based on spot area and intensity. An expression heatmap was drawn. Cytokines were arranged by the ratio of MIX CON to OV90 CON (highest top). (C) 79 Cytokines with ≥ 1.5 folds change between MIX CON and OV90 CON were subjected to pathway and GO analysis using Enrichr. Returns were ranked by P-value (most significant top) and the top 10 returns are shown. The P-value is “computed from the Fisher exact test which is a proportion test that assumes a binomial distribution and independence for probability of any gene belonging to any set” (Enrichr). The highest P-value of the top 10 returns for KEGG pathway, GO biological process and GO molecular function are 5.2 x 10−4, 2.2 x 10−6 and 1.4 x 10−3, respectively. (D) 52 cytokines with ≤ 0.8 folds change between MIX GNP and MIX CON were subjected to pathway and GO analysis. Returns were ranked by P-value (most significant top) and the top 10 returns are shown. The highest P-value of the top 10 returns for KEGG pathway, GO biological process and GO molecular function are 8 x 10−7, 1.7 x 10−11 and 5.7 x 10−5. (E) Expression changes of cytokines initiating MAPK and PI3K-AKT pathways. All cytokines shown initiate MAPK pathway. Cytokines labeled blue initiate PI3K-AKT pathways. * P < 0.05, compared to MIX CON. (F) ERK1/2 and AKT activation by CM. OV90 cells were treated for 10 min with CM from OV90 alone or from the OV90, TAF18 and HMEC cocultures (MIX) incubated with or without GNP. Cell lysates with 10 μg proteins were loaded to each lane in 10% SDS-PAGE. 10% FBS: phosphorylation positive control, 0% FBS: phosphorylation negative control; t-ERK1/2 (total ERK), t-AKT (total AKT) and GAPDH: loading controls.

To get meaningful information, we input the valid gene symbols of the 52 cytokines with ≤ 0.8-fold changes (p < 0.1) between the GNP-treated coculture and the control coculture (ratio of MIX GNP / MIX CON or MIX CON / MIX GNP ≤ 0.8) to Enrichr (Tab S6). KEGG pathway results showed that: (1) MAPK, (2) PI3K-AKT and (3) Ras signaling pathways (Fig 6D, Tab S7) were among the top 10 relevant and significantly altered (P < 0.001) pathways. GO Biological Process results showed that: (1) positive regulation of the MAPK cascade, (2) positive regulation of ERK1 and ERK2 cascades, (3) regulation of peptidyl-tyrosine phosphorylation, and (4) positive regulation of cell proliferation (Fig 6D, Tab S8) were among the top 10 relevant and significantly altered (P < 0.001) processes. GO Molecular Function results classified: (1) cytokine activity and receptor binding, (2) growth factor activity and receptor binding, (3) chemokine activity and receptor binding, and (4) phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate kinase activity (Fig 6D, Tab S9) as among the top 10 relevant and significantly altered (P < 0.001) functions.

It is notable that most of the top-ranked KEGG pathways, GO biological processes, and GO molecular functions associated with coculture (MIX CON vs OV90 CON) and those associated with GNP treatment (MIX GNP vs MIX CON) were the same or similar (Fig 6C, 6D), except that if coculture promoted a pathway (process, or function), then GNP treatment inhibited it, and vice versa. This suggested that these pathways, processes and functions are readily affected and important for the cell behaviors discussed herein. Specifically, the common and top relevant “Ras signaling pathway”, “MAPK cascade”, and “ERK1 and ERK2 cascades” pointed to the activation of the classical MAPK pathway (Cytokines-Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK1/2) that directly participates in the regulation of cell proliferation [43]. The analysis-identified cytokines that initiated this signaling pathway were angiopoietin-1, Fas Ligand, FGF basic, FGF-7, growth hormone, IL-11, LIF, MCP-3, M-CSF, MIP-1alpha/MIP-1beta, PDGF-AA, PDGF-AB/BB, RAGE, TARC, TGF-alpha and TNF-alpha. Consistently, the expression of these cytokines was upregulated by coculture as compared to monoculture, and downregulated by GNP as compared to PBS (Fig 6E). Another common and top relevant pathway was identified as PI3K-AKT that also actively regulates cell proliferation [43]. Cytokines activating this pathway were angiopoietin-1, Fas Ligand, FGF basic, FGF-7, growth hormone, PDGF-AA, PDGF-AB/BB, M-CSF and TNF-alpha. Again, expression of these cytokines was upregulated by coculture as compared to monoculture, and downregulated by GNP as compared to PBS (Fig 6E). Equally importantly, both the MAPK and PI3K-AKT pathways play a key role in the induction of EMT [44, 45].

To validate the involvement of ERK1/2 and AKT activation in coculture and the effect of GNP treatment, we treated the starved OV90 with the three CM, and found that ERK1/2 (Thr202 / Tyr204) and AKT (Thr308 / Ser473) were phosphorylated more by the coculture control CM than the monoculture control CM, whereas the GNP-treated coculture CM inhibited the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (Thr202 / Tyr204) and AKT (Ser473) (Fig 6F).

These results demonstrated that some cytokines and growth factors were upregulated in the CM from coculture, initiated MAPK and PI3K-AKT pathways, and promoted CC proliferation and EMT. One the other hand, GNP inhibited the processes by downregulating these cytokines and growth factors. Next, we investigated if GNP can inhibit the multicellular communications and tumor aggressiveness in vivo.

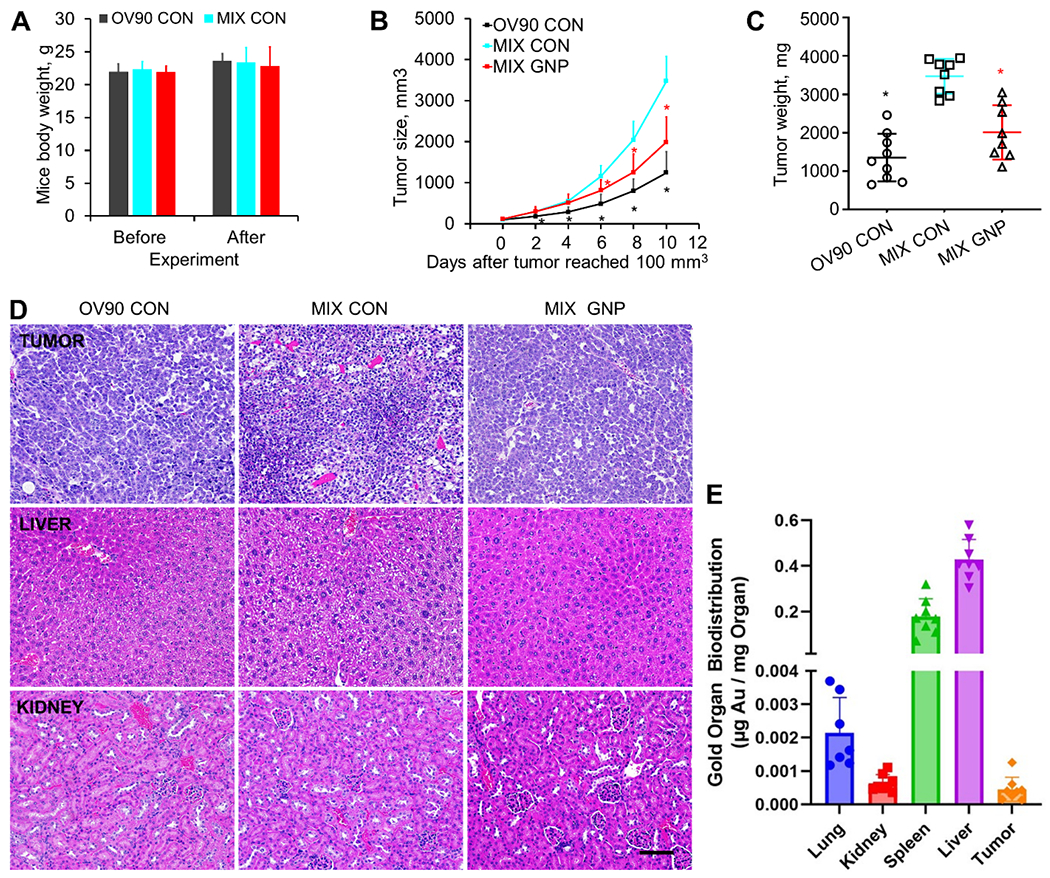

GNP inhibited tumor growth and reversed EMT

We used human xenograft tumor models to validate our in vitro findings and to investigate the effect of GNP on tumor aggressiveness. OV90 cells (1x106 cells/mouse) alone or with TAF18 cells (1x106 cells/mouse) and HMEC (1x106 cells/mouse) were inoculated into nu/nu mice subcutaneously. Mice were assigned to one of three treatment groups: (1) OV90 only tumor control (OV90 CON), (2) mixed-cell tumor control (MIX CON), and (3) mixed-cell tumor GNP treatment (MIX GNP). Mice were injected with either GNP 200 μg/mouse through the tail vein three times a week, or an equal volume of PBS (for CON) once tumors attained a volume of 100 mm3. The dosage of GNP was determined based on our previous data showing that this dose, compared to 100 and 400 μg/mouse, achieved the best therapeutic effect on A2780 and SKOV3 orthotopic tumors. Despite significant uptake to the liver and marginal uptake to lungs and kidneys, no sign of toxicity was seen in those animals [4]. Since the in-group body weight variation was minimal (22.33±1.19 g and 23.34±2.27 g at the beginning and the end of the experiment, MIX GNP group, Fig 7A), administration of GNP as μg/mouse instead of μg/mg body weight allowed the GNP concentration to remain practically constant for all the mice, while also limiting disturbance of the animals. Mouse health status and tumor size (Fig 7B) were monitored throughout the experiment as mandated by the IACUC. Several mice were removed from study early: one OV90 CON mouse did not develop tumor; two MIX CON mice developed cachexia; one MIX GNP mouse died by tail vein injection; and one mouse inoculated with MIX did not form tumor. Physical appearance, activity and body weights of the mice did not differ significantly between and among groups, suggesting mouse tolerance of the GNP dosage (Fig 7A). Animals were euthanized and weighed, and tumors were collected and weighed before the tumors attained IACUC-mandated limits (Fig 7C). Both the average volume and weight of tumors in the MIX CON group were significantly greater than in the OV90 CON group, suggesting that the tricellular crosstalk promoted tumor growth. Importantly, treatment of the co-inoculation tumors with GNP significantly inhibited tumor growth, further confirming the ability of GNP to disrupt multicellular crosstalk within the TME. No indications of cytotoxicity in any mouse were seen in the hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of various organs (Fig 7D, Fig S3). Biodistribution and accumulation analysis showed that GNP were significantly enriched in liver (0.4 μg Au/mg Organ) and spleen (0.2 μg/mg) (Fig 7E). GNP accumulation in the tumor (0.4 ng/mg) was much lower than these two organs, but comparable to lung (2 ng/mg) and kidney (0.6 ng/mg), suggesting that the particles can directly act on CC and TME cells, besides binding the secreted and circulating cytokines.

Fig 7.

GNP inhibit tumor growth without obvious toxicity to host mice. OV90 (1x106 cells/mouse) with or without TAF18 (1x106 cells/mouse) and HMEC (1x106 cells/mouse) were inoculated to nu/nu mice subcutaneously. Mice were divided in three groups: (1) OV90 cells alone, PBS treated (OV90 CON), (2) all three cell types, PBS treated (MIX CON), and (3) all three cell types, GNP treated (MIX GNP). Tumor sizes were measured every (other) day once the tumor appeared. Treatment began when tumor attained a volume of 100 mm3. Treatments were GNP (200 μg/mouse, iv, 3 times a week) or an equivalent volume of PBS. (A) Mice body weights before and after experiment. (B) Tumor growth curves. (C) Tumor weight at collection (10 days after their volume reached 100 mm3). (D) HE staining of tumors and mouse organs. (E) GNP biodistribution and accumulation in tumor and organs. Mass of gold (Au) was measured per mass of examined tissue samples with ICP-MS. N=8 except for Lung group from which one significant outlier was removed. * P < 0.05, compared to MIX CON. Scale bar, 100 μM.

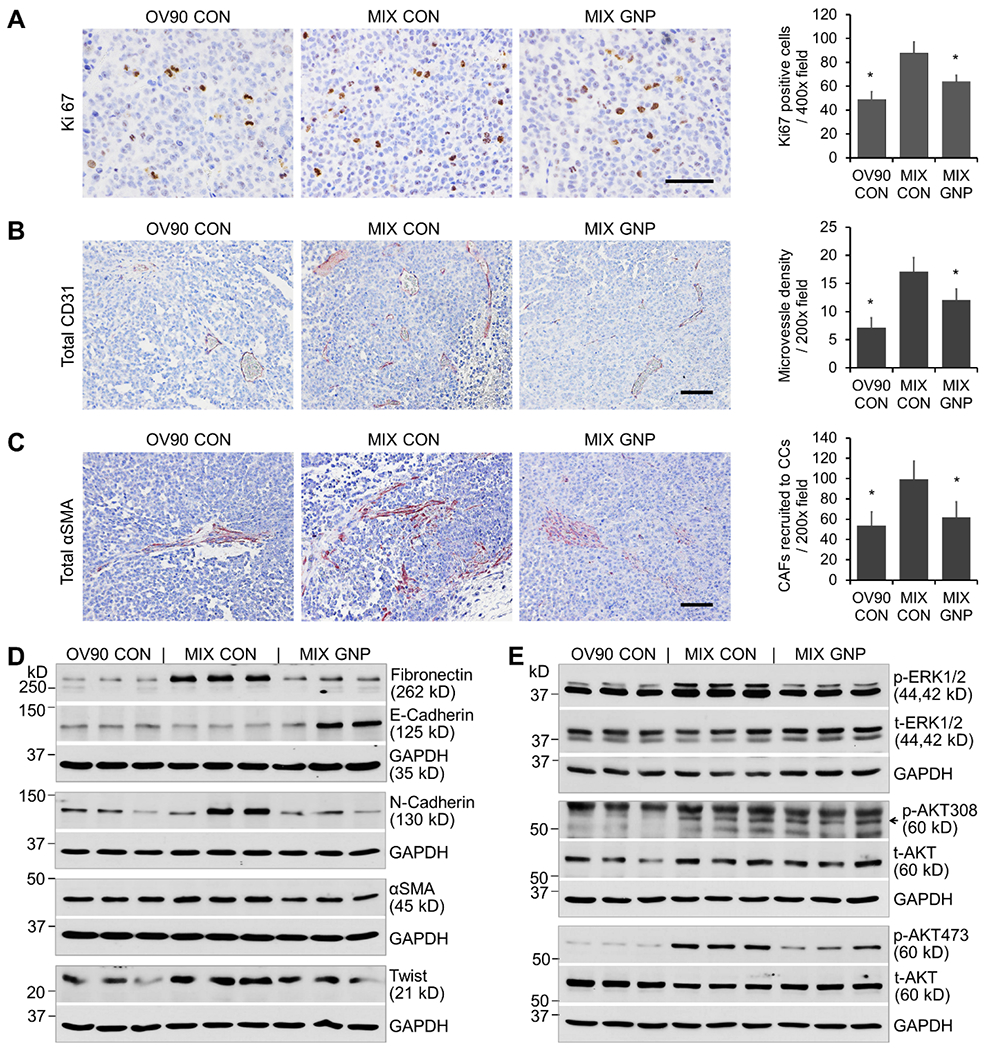

H&E staining of tumor tissues did not show much difference among the groups, but the CC in some areas in the MIX CON group seemed smaller and denser compared to the other two groups, suggesting they are faster growing and at a different stage in EMT (Fig 7D). Ki67 (proliferating cell marker) staining of tumor tissues showed there were more active proliferating CC in MIX CON than in OV90 CON, whereas GNP treatment significantly decreased the number of proliferating cells (Fig 8A). CD31 (EC marker) staining by “anti-mouse + anti-human” antibodies showed that the total micro-vessel density (MVD) was more pronounced in MIX CON than in either OV90 CON or MIX GNP (Fig 8B), suggesting greater angiogenic activity in the co-inoculation tumor which was inhibited by GNP. αSMA (CAF marker) staining, to assess fibroblast activation, using an antibody reactive to both mouse and human αSMA, showed more CAF interspersed with CC in MIX CON than in either OV90 CON or MIX GNP (Fig 8C), suggesting enhanced activation of fibroblasts in co-inoculation tumors which was decreased upon GNP treatment. To further validate the in vitro finding of EMT induction in coculture and its inhibition by GNP treatment, we assessed expression of multiple EMT markers in tumor tissues (Fig 8D). Upregulation of Fibronectin, N-cadherin, αSMA and Twist, accompanied by downregulation of the epithelial marker E-cadherin was seen in MIX CON compared to the OV90 CON. GNP treatment of mice with co-inoculation tumors downregulated the EMT markers and upregulated E-cadherin, validating the in vitro findings and supporting the conclusions that CAF and EC, in concert, promote ovarian tumor aggressiveness, and that GNP treatment effectively disrupts the tricellular communication. Finally, we assessed activation of ERK1/2 (Thr202 / Tyr204) and AKT (Thr308 / Ser473) in tumor tissues, and observed that phosphorylation of the kinases was increased in MIX CON compared to OV90 CON. Importantly, phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (Thr202 / Tyr204) and AKT (Ser473) was decreased in MIX GNP compared to MIX CON (Fig 8E). These data reinforced the in vitro observations that coculture, through the cellular secretome, promotes aggressive behaviors of CC via ERK1/2 and AKT signaling, and that GNP disrupts these processes by inhibiting the pathways.

Fig 8.

GNP inhibit tumor aggressiveness by blockade of MAPK and PI3-AKT signaling, angiogenesis and CAF recruitment. (A) Ki67 staining of tumor tissues and quantification of the positive cells. (B) Anti-mouse- and anti-human-CD31 staining of tumor tissues and quantification of the MVD. (C) Anti-αSMA (reactive to both human and mouse) staining of tumor tissues and quantification of the positive cells interspersed among CC. (D) EMT marker expression in tumor tissues was examined by WB. Fractions of three biggest tumors from each group were lysed. Tissue lysates were loaded (10 μg- 60 μg proteins) to each lane in 6% or 12% SDS-PAGE. GAPDH was used as loading control. (E) Activation of ERK1/2 and AKT in tumor tissues. The same tissue lysates for (D) with 20 μg proteins were loaded to each lane in 10% SDS-PAGE. t-ERK1/2, t-AKT and GAPDH were used as loading controls.

Discussion

Multicellular interactions of CC, CAF, and EC in a triangular fashion have not been thoroughly studied, in part due to the lack of models incorporating all the functioning components [46, 47]. Herein, we established comprehensive in vitro and in vivo ovarian cancer models that serve to illustrate the triangular crosstalk among CC, CAF, and EC. Our in vitro models combined HGSC OV90 cells or undifferentiated ovarian carcinoma A2780-CP20 cells, with ovarian cancer primary CAF TAF18 cells, and HMEC or HUVEC; our in vivo model combined OV90 cells, TAF18 cells and HMEC. In vitro investigation indicated that both TME cells promote CC proliferation, that the more TME cells are present then the faster CC grow, and that the simultaneous presence of the two types of TME cells promotes CC growth more effectively than either single TME cell type. In vivo, OV90 co-inoculated with TAF18 and HMEC at equal numbers gave rise to tumors almost three times the size of tumors arising from OV90 alone. At the tissue level, more blood vessels were formed in the co-inoculation tumors than in the CC only tumors. At the cellular level, more CAF were recruited to the sites of CC in the co-inoculation tumors than in CC only tumors. At the molecular level, multiple cytokines, including angiopoietin-1, FGF basic, FGF-7, growth hormone, PDGF and M-CSF, were upregulated in the CM of CC-CAF-EC coculture compared to CC monoculture. These cytokines initiated the MAPK and PI3K-AKT signaling pathways that mediated CC proliferation and tumor growth. Indeed, activated ERK1/2 phosphorylates ribosomal S6 kinases (RSK) and both ERK and RSK translocate to the nucleus where they activate multiple transcription factors such as Elk-1, CREB and Fos, resulting in effector protein synthesis and cell survival and proliferation [48]. ERK1/2 activation phosphorylates Bim and Bid, and causes Bim degradation and Bad sequestration to inhibit apoptosis and increase cell survival. ERK1/2 phosphorylates FOXO3a to enhance FOXO3a degradation that leads to cell proliferation, transformation, angiogenesis and tumor progression [48]. ERK1/2 also activates various other transcription factors including carbamoyl phosphate synthetase II (CPS II) to facilitate DNA synthesis and cell cycle progression [43]. Cooperatively, activated AKT drives CC growth via activating mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) to initiate protein synthesis, activating mouse double minute 2 homolog (MDM2) to inhibit p53 mediated apoptosis, and inhibiting Bad, p27, glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) and FOXO transcription factors 1 and 4 (FOXO1/4) to suppress apoptosis and promote cell cycle [43]. Thus, the triangular crosstalk among ovarian CC, CAF and EC mediated at least partially by cytokines secreted by the cells involved, not only promotes EC angiogenesis [39] and CAF activation [16], as we reported previously, but also supports tumor growth.

We observed that coculture induced CC EMT as evidenced by morphological, functional and molecular marker changes [41]. The underlying mechanism as we deduced based on our findings could also be the cytokines induced MAPK and PI3K-AKT signaling. In fact, classical RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK-MAPK signaling, activated by cytokines or growth factors, acts as a major EMT-inducing pathway. Activated ERK1/2 enables EMT by upregulating EMT transcription factors such as Twist and the regulators of cell migration and invasion such as Rho GTPases [44, 45]. The PI3K-AKT pathway activates transcription factors binding to the promoters of genes encoding EMT transcription factors such as Twist and Snail, inhibits the expression of genes encoding cell adhesion molecules, and induces EMT [44, 45].

MAPK and PI3K-AKT are two major signaling pathways activated in patient EOC tissues and contribute significantly to the progression of this malignancy [49]. EMT can further aggravate the process by inciting cell fate transitions, increasing CC survival and upregulating drug resistance genes [50]. Accordingly, inhibitors of the key molecules in MAPK and PI3K-AKT pathways such as sorafenib, a multi-kinase (receptor tyrosine kinases and serine/threonine kinase) inhibitor, was shown to improve the progression-free survival of platinum-resistant ovarian cancer patients in a phase II trial [51]. Anti-EMT therapies were reported to reverse therapy resistance in vitro or in vivo as exemplified by Twist-targeting siRNA that sensitized ovarian cancer to cisplatin and suppressed tumor growth [52]. Interestingly, PD98059, a MEK inhibitor, impaired cisplatin-resistance of ovarian CC by repressing the ERK pathway and EMT processes [53].

We evaluated the effects of GNP on ovarian cancer aggressiveness in the context of the TME. We found that GNP suppressed the growth, EMT, migration and invasion of OV90 cells in vitro and OV90 derived tumors in vivo. Mechanistically, GNP inhibited tumor angiogenesis and CAF accumulation around CC. GNP downregulated multiple cytokines that activate MAPK and PI3K-Akt signaling pathways. Treatment with GNP reportedly modulates levels of multiple cytokines, growth factors and other secreted proteins. For example, treatment of prostate CC with 60 nm GNP upregulated IL-10 and CXCL3 and downregulated MMP9 and CCL2 [6]. GNP altered levels of HGF, IL-6, IL-8, PDGF-AA, TGF-β1 and VEGF secreted by CAF from oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), and downregulated these cytokines in the tissues of OSCC xenograft tumors [15]. Our previous work showed that GNP changed the secretomes of pancreatic CC, pancreatic stellate cells (pancreatic CAF) [5], ovarian CC [4, 16] and ovarian CAF [16]. The mechanisms by which GNP regulates protein expression are not fully understood. The interaction between GNP and biological systems results in the formation of a protein corona around the nanoparticles. The physicochemical properties of GNP (such as size, shape, charge, concentration, surface modifications) and characteristics of proteins (such as amino acid residues, domain, abundancy) are among the most important determinants of the protein corona composition [17]. Some proteins, such as those rich in -SH and -NH2 residues [54] or heparin-binding domains [14] may preferentially bind to GNP and become the major components of the corona. Formation of protein coronas reduces the circulating levels of free, functional proteins, including those related to mRNA processing [55], and thus can regulate protein expression on both protein and mRNA levels [4–6].

Conclusions

In summary, we used ovarian CC, CAF, and EC for in vitro coculture and in vivo co-inoculation models to investigate the triangular communication among the three cell types, the effects of the communication on cancer aggressiveness, and the inhibitory effects of GNP. We found that the TME cells promoted cancer growth and EMT via cytokines that initiate MAPK and PI3K-AKT pathways. GNP, by downregulating the cytokines, inactivating MAPK and PI3K-AKT pathways, inhibiting cell proliferation, reverting EMT, preventing tumor angiogenesis and the recruitment of CAF to CC, suppressed cancer aggressiveness. This work provided experimental evidence that the triangular crosstalk among CC, CAF and EC promotes EOC progression and that interrupting the crosstalk using GNP is a promising therapeutic strategy.

Material and methods

Preparation and Characterization of 20 nm GNP

GNP (20 nm in diameter) were prepared as previously described [39]. Briefly, 5 ml of 10 mM HAuCl4·3H2O (tetrachloroauric acid trihydrate, 520918, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in 185 ml water (endotoxin-free, 786671, G Biosciences, St. Louis, MO) was heated to boiling in a 500 ml flask. Fifteen ml of sodium citrate (1%, 1613859, Sigma) preheated to 70°C was added to the flask 4 min later. The solution was boiled for 14 min with active agitation until the color changed to dark purple. The solution was then stirred overnight at 25°C. The GNP was then characterized using UV–visible spectroscopy (Spectrostar Nano, BMG, Cary, NC), dynamic light scattering (Zetasizer Nano, Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, UK), zeta potential measurement (Malvern Zetasizer Nano) and transmission electron microscopy (Hitachi H-7600, Chiyoda, Tokyo, Japan). To concentrate them, the GNP was centrifuged at 10000 rpm for 20 min at 10 °C immediately before use. To determine the concentration of GNP, the original solution was concentrated 16 folds; OD for both original and concentrated solutions were measures at 800 nm and 522 nm. The concentration of the original solution was calculated as follows: 30.02 × total initial volume × (OD520-OD800) of concentrated/[as synthesized volume × (OD520-OD800) of as synthesized]. All GNPs were used within two weeks of preparation.

Cell Culture

Human EOC cell line A2780-CP20 (designated as CP20) was a kind gift from Dr. Anil Sood (MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX); OV90 was from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). EGFP (enhanced green fluorescent protein) stably expressing CP20 or OV90 cells were established by transfecting the cells with pcDNA3-EGFP vector (Watertown, MA) with FuGENE 6 Transfection Reagent (E2691, Promega, Madison, WI). All cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 (10-040-CV, Corning, NY) with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS, 16000-044, Life technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and 1% Penn-Strep (15140-122, Life technologies). Primary ovarian CAF TAF18 were isolated and identified in this laboratory [39], grown in DMEM:F12 (10-090, Corning, NY) with 15% FBS and 1% Penn-Strep, and used up to passage 7. HMEC, a kind gift from Dr. Xin Zhang (OUHSC Stephenson Cancer Center, Oklahoma City, OK), and HUVEC (Lonza, Walkersville, MD) were propagated in Endothelial Cell Growth Medium 2 (EGM, CC-3162) and used up to passage 7 [56]. When different types of cells were cultured together, the mixed cells were grown in a mixed medium prepared by combining equal volumes of the individual medium for each of the three cell types. All cells were maintained in a humidified 95% air and 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C.

Preparation of Conditioned Media (CM)

CM from GNP-treated or PBS-treated (control) CC (CP20-EGFP or OV90-EGFP) alone or from cocultures (CC + TAF18 + HMEC) was prepared. Briefly, 5x105 CC alone, or “5x105 CC + 5x105 TAF18 + 5x105 HMEC” were seeded to culture dishes (T1110, Thomas Scientific, Swedesboro, NJ) of 10 cm in diameter, and cultured in complete mixed medium for 16 h. Media were replaced with serum-free mixed medium for 16 h. The cells were then treated with 25 μg/ml GNP or the same volume of PBS in fresh serum-free mixed medium for 48 h. The serum-free media were collected, centrifuged for 6 min at 1500 rpm to remove cell debris, then centrifuged for 20 min at 10000 rpm at 10 °C to remove the GNP, and used within 1 h or stored at −80 °C for later use.

Proliferation assay

Proliferation of EGFP labeled CC was evaluated by EGFP fluorescence intensity. Specific numbers of CP20-EGFP or OV90-EGFP, either alone or mixed with TAF18 and HUVEC or HMEC cells, were seeded onto 96-well plates (1156F02, Thomas Scientific) in complete mixed medium for 16 h. Media were replaced with serum-free mixed medium. The cells were then left untreated, or treated with 25 μg/ml GNP, an equivalent volume of PBS, or CM for three or seven days. Cell images were taken with a Zeiss Axiovert 200M inverted fluorescence microscope before processing for fluorescence intensity measurement. Cell media were removed by inverting and shaking the plates gently. Trypsin (30 μl) was added to each well and incubated for 5-10 min to ensure complete cell detachment. PBS (200 μl) was then added to each well. Cells were resuspended by pipetting and then allowed to settle. Trypsin (30 μl) plus PBS (200 μl) without cells was used as blank control. OD488 was measured as an indicator of cell number using CLARIOstar microplate reader (BMG Labtech, Cary, NC). Experiments were performed in sextuplicate and repeated 3 times.

Migration assay

OV90-EGFP cells were starved in RPMI 1640 for 16 h, trypsinized, and seeded onto each transwell (3422, Corning) at 80,000 cells in 200 μl RPMI 1640 containing 0.1% BSA (bovine serum albumin, A2153, Sigma). Cell migration was induced by CM added immediately after seeding to the outwells at 700 μl/well for 16 h. Cells were fixed and dyed using 0.2% crystal violet (C0775, Sigma) in 20% ethanol. Cells inside the inserts were cleared away with cotton swabs. Cells migrated across the membrane were then photographed and counted using ImageJ. For analysis, migration induced by CM from OV90 only/PBS was set as 100%. Experiments were done in duplicate and repeated three times.

Invasion assay

OV90-EGFP cells were starved in RPMI 1640 for 16 h, trypsinized, and seeded onto each invasion chamber (354480, Corning) at 100,000 cells in 300 μl RPMI 1640 containing 0.1% BSA. Cell invasion was induced by CM added immediately after seeding to the outwells 800 μl/well for 24 h. The subsequent steps were as described in the “Migration assay”. Experiments were done in duplicate and repeated three times.

Western Blotting

OV90-EGFP cells were starved for 16 h and then incubated with CM for 48 h (for EMT marker expression) or 10 min (for ERK1/2 and AKT activation). Cells were collected after washing with PBS twice, and lysed with RIPA buffer (BP-115, Boston BioProducts, Ashland, MA) containing Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (78440, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (78420, ThermoFisher Scientific) on ice. Xenograft tumor tissues from mice were lysed by sonication in RIPA buffer on ice. The concentration of proteins in the lysate was determined with BCA Protein Assay Kit (23227, Thermo-Fisher). Lysates (5 μg - 60 μg proteins/lane) were separated on 6% - 12% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to PVDF membranes (1620177, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat milk (M7409-1BTL, Sigma)/PBST (0.1% Tween-20, P1379, Sigma, in PBS) at RT for 45 min, and then incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. HRP-coupled secondary antibodies were applied at RT for 1 h, followed by blotting development with Clarity Western ECL Substrates (1705061, Bio-Rad) or SuperSignal West Femto (TI271896A, ThermoFisher). Primary antibodies used were Abcam (Cambridge, MA) rabbit anti-Fibronectin (1:1000, ab23751), rabbit anti-collagen I (1:1000, ab34710); BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA) mouse anti-N-cadherin (1:2000, #610920), mouse anti-β-catenin (1:1000, 610154); Sigma rabbit anti-Twist (1:1000, SAB1411370), rabbit anti-GAPDH (1:10000, G9545); and Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA) mouse anti-E-cadherin (1:2000, 5296), rabbit anti-vimentin (1:1000, 5741), rabbit anti-α-SMA (1:1000, 19245), rabbit anti-Phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204) (1:1000, 4370), rabbit anti-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (1:1000, 9102), rabbit anti-Phospho-Akt (Thr308) (1:1000, 13038), rabbit anti-Phospho-Akt (Ser473) (1:1000, 4060), mouse anti-Akt (pan) (1:1000, 2920). Secondary antibodies were Sigma goat anti-mouse IgG (1:10000, A4416) and goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:10000, A6154). To detect tumor tissue total Erk or Akt, membranes for Phospho-Erk or Phospho-Akt were stripped with Stripping Buffer (#BP-98, Ashland, MA) for 10 min, followed by standard Western Blotting.

Antibody array assay

CM (1 ml each) from OV90-EGFP monocultures, the coculture control, and the GNP-treated coculture were incubated with antibody array membrane from the Proteome Profiler Human XL Cytokine Array Kit (ARY022B, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) at 4°C for 16 h, followed by incubation with biotinylated detection antibody cocktail, streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase and chemiluminescent detection reagents. Films were developed for different exposure times. Blot images were scanned with Color LaserJet Pro MFO M477fdn and quantified with Quick Spot image analysis tool (Western Vision Software, Salt Lake City, UT). Values were manually adjusted based on spot area and intensity. Experiments were repeated twice.

Animal studies

Female athymic nude mice (NCr-nu; 6-week old, Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) were housed and maintained under pathogen-free conditions in facilities approved by American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care and in accordance with regulations and standards of US Department of Agriculture, Department of Health and Human Services, and National Institutes of Health. Studies were approved and supervised by the University of Oklahoma Health Science Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. OV90-EGFP cells (1x106 cells in 100 μl PBS) were inoculated (day 0) subcutaneously (SC) to the flanks of 10 mice. Mixed OV90-EGFP, TAF18 and HMEC cells (1x106 + 1x106 + 1x106 in 100 μl PBS) (MIX) were inoculated SC to the flanks of 20 mice. Mice weights were recorded weekly and their health and behavior were monitored daily. Once tumors began to appear, tumor sizes were measured with calipers every (other) day. Tumor volume was calculated as V = W2 × L/2, where W is tumor width and L is tumor length. Once the tumor reached 100 mm3, the mice were grouped and treated as: (1) OV90 only: PBS (as OV90 CON), (2) MIX: PBS (as MIX CON), and (3) MIX: GNP (as MIX GNP), where GNP was injected 200 μg/mouse through the tail vein three times a week. The experiment was terminated at day 29 when the maximum allowable tumor size was attained. Tumors were weighed, photographed, and preserved in 10% formalin solution (HT501128, Sigma) and −80°C.

Tissue staining

Tumor grafts were fixed in 10% formalin solution for 24 h, transferred to 70% ethanol, embedded with paraffin, serially sectioned at 4 μm thickness, and mounted on positively charged slides. Slides were processed for Hematoxylin and Eosin (HE) staining using standard protocols. For Ki67 staining, slides were deparaffinized and rehydrated in an automated Multistainer (ST5020, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). The slides were then transferred to the BOND-III automated IHC Stainer (Leica) for stepwise incubation with BOND Epitope Retrieval Solution pH 6 (AR9961, Leica) at 100°C for 20 min, 5% goat serum (01-6201, ThermoFisher) at 25°C for 30 min, Peroxidase Block (RE7101, Leica) at 25°C for 10 min, and primary antibody rabbit anti-Ki67 (1:2500, ab16667, Abcam) at 4°C for 16 h. The Bond Polymer Refine Detection System (DS 9800, Leica) was then used to localize primary antibodies, visualize the targets, and counterstain cell nuclei according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The slides were dehydrated in Multistainer and mounted with MM 24 Mounting Media (3801120, Leica). For CD31 and αSMA staining, slides were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated in graded alcohol, subjected to heat-induced antigen retrieval with pH 6.0 Antigen Retrieval Buffer (ab93678, Abcam) for 20 min, blocked with 2.5% Horse Serum (30022, Vector Lab, Burlingame, CA) for 1 h, probed with rabbit anti-human CD31(1:50, ab32457, Abcam) and rabbit anti-mouse CD31 (1:100, #77699, Cell Signaling) combined, or rabbit anti-αSMA reactive to both human and mouse αSMA (1:200, #19245, Cell Signaling) at 4°C overnight. Slides were washed and incubated in Peroxide Block (925B-05, Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA) for 10 min, followed by incubation with SignalStain Boost Reagent (#8114, Cell Signaling) for 30 min. Sections were developed with AEC Substrate (ab64252, Abcam), counterstained with 50% hematoxylin, and mounted with aqueous Mounting Medium (ab64230, Abcam). Negative (omission of primary antibody) controls were stained in parallel and no staining was observed under these conditions. To quantify MVD, five microscopic images of 200x fields in each section that contain the greatest microvessel density (hotspots) were taken. Any red staining of cell or cell cluster that was separate from adjacent microvessels was considered a single, countable vessel. The 3 highest vessel counts for each section were used for statistical analysis. All tumors were counted [57]. To quantify CAF, five microscopic images of 200x fields in each section that contain the greatest red spots (hotspots) were taken. Any red staining of cell that was separate from other cells was considered a countable cell. The 3 highest cell counts for each section were used for statistical analysis. All tumors were counted.

Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS)

Tissue samples were processed and analyzed as previously described [58–60]. Briefly, 37% formaldehyde fixed tumor, lung, kidney, liver, and spleen tissue samples were collected and weighted into borosilicate tubes. Tissue samples were digested by the addition of 0.8 ml of 16-M nitric acid to each sample. The samples were then incubated in a water bath at 70°C for 2 h. Next, 0.2 ml of 12-M hydrochloric acid were added to each sample followed by another hour of incubation using similar digestion conditions as in the previous step. Samples were allowed to cool to room temperature and then diluted into nanopure water containing an internal standard of iridium to a final volume of 40 ml. Five ml of these diluted solutions were filtered through a 0.22-μM syringe filter (MilliporeSigma™ SLGPR33RS) into 15-ml conical tubes. A gold standard curve was prepared using the same final acid concentration, 2.0% (v/v) nitric acid and 0.5% (v/v) hydrochloric acid as the digested tissue samples. Elemental analysis was performed with a PerkinElmer NexIon 2000 ICP-MS at the Mass Spectrometry Facility of the University of Oklahoma. Gold organ biodistribution (μg of gold / mg of organ) was then calculated.

Statistics

Data were expressed as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA was performed to compare the mean among three or more groups using GraphPad Prism 9 software. P value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Cocultured EC and CAF promote cancer cell proliferation

20 nm GNP inhibit the growth of cancer cells cocultured with EC and CAF

Supernatants of coculture treated with GNP reduce cancer cell aggressiveness

GNP downregulate cytokines initiating MAPK and PI3-AKT pathways and EMT

Co-inoculated EC and CAF promote tumor growth in vivo and GNP inhibit the process

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants CA220237, 2CA136494, and CA213278, CA253391, 1R01CA260449-01A1 (to P.M.). We thank the Peggy and Charles Stephenson Cancer Center at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center for a seed grant, and an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant number P20 GM103639 for the use of Histology and Immunohistochemistry Core, which provided immunohistochemistry and image analysis service. Research reported in this publication was also supported in part by the National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA225520 and the Oklahoma Tobacco Settlement Endowment Trust contract awarded to the University of Oklahoma Stephenson Cancer Center and used the services of the Proposal Services Core. S.W. acknowledges funding from NSF CAREER (2048130), OCAST (HR20-106), the University of Oklahoma Research Council Faculty Investment Program, and the IBEST-OUHSC Collaborative Funding for Interdisciplinary Research. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors thank Daniel Morton for editorial assistance.

Abbreviations

- αSMA

α-smooth muscle actin

- CAF

cancer-associated fibroblast

- EBM

endothelial cell growth basal medium

- EC

endothelial cell

- EGM

endothelial cell growth medium

- EMT

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- EOC

epithelial ovarian cancer

- GNP

gold nanoparticle

- HMEC

human microvascular endothelial cells

- HUVEC

human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- MVD

microvessel density

- SFM

serum-free media

- TME

tumor microenvironment

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CRediT author statement

Yushan Zhang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Chandra Kumar Elechalawar, Wen Yang, Alex N. Frickenstein: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft. Sima Asfa: Methodology, Investigation. Kar-Ming Fung: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Resources. Brennah N Murphy, Shailendra K Dwivedi, Geeta Rao, Anindya Dey: Methodology, Investigation. Stefan Wilhelm: Resources, Project administration, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing. Resham Bhattacharya: Conceptualization, Resources, Project administration, Writing - review & editing. Priyabrata Mukherjee: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Project administration, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

REFERENCES

- [1].Melamed JR, Riley RS, Valcourt DM, Day ES, Using Gold Nanoparticles To Disrupt the Tumor Microenvironment: An Emerging Therapeutic Strategy, ACS Nano 10(12) (2016) 10631–10635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Selim ME, Hendi AA, Gold nanoparticles induce apoptosis in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells, Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 13(4) (2012) 1617–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tan G, Onur MA, Cellular localization and biological effects of 20nm-gold nanoparticles, J Biomed Mater Res A 106(6) (2018) 1708–1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Arvizo RR, Saha S, Wang E, Robertson JD, Bhattacharya R, Mukherjee P, Inhibition of tumor growth and metastasis by a self-therapeutic nanoparticle, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110(17) (2013) 6700–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Saha S, Xiong X, Chakraborty PK, Shameer K, Arvizo RR, Kudgus RA, Dwivedi SK, Hossen MN, Gillies EM, Robertson JD, Dudley JT, Urrutia RA, Postier RG, Bhattacharya R, Mukherjee P, Gold Nanoparticle Reprograms Pancreatic Tumor Microenvironment and Inhibits Tumor Growth, ACS Nano 10(12) (2016) 10636–10651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hao Y, Hu J, Wang H, Wang C, Gold nanoparticles regulate the antitumor secretome and have potent cytotoxic effects against prostate cancer cells, J Appl Toxicol 41(8) (2021) 1286–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Parnsamut C, Brimson S, Effects of silver nanoparticles and gold nanoparticles on IL-2, IL-6, and TNF-alpha production via MAPK pathway in leukemic cell lines, Genet Mol Res 14(2) (2015) 3650–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Li W, Li X, Liu S, Yang W, Pan F, Yang XY, Du B, Qin L, Pan Y, Gold nanoparticles attenuate metastasis by tumor vasculature normalization and epithelial-mesenchymal transition inhibition, Int J Nanomedicine 12 (2017) 3509–3520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bhattacharya R, Patra CR, Verma R, Kumar S, Greipp PR, Mukherjee P, Gold Nanoparticles Inhibit the Proliferation of Multiple Myeloma Cells, Adv Mater 19 (2007) 711–716 [Google Scholar]

- [10].Chakraborty A, Das A, Raha S, Barui A, Size-dependent apoptotic activity of gold nanoparticles on osteosarcoma cells correlated with SERS signal, J Photochem Photobiol B 203 (2020) 111778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Huai Y, Hossen MN, Wilhelm S, Bhattacharya R, Mukherjee P, Nanoparticle Interactions with the Tumor Microenvironment, Bioconjug Chem 30(9) (2019) 2247–2263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hossen MN, Rao G, Dey A, Robertson JD, Bhattacharya R, Mukherjee P, Gold Nanoparticle Transforms Activated Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts to Quiescence, ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 11(29) (2019) 26060–26068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Shen N, Zhang R, Zhang HR, Luo HY, Shen W, Gao X, Guo DZ, Shen J, Inhibition of retinal angiogenesis by gold nanoparticles via inducing autophagy, Int J Ophthalmol 11(8) (2018) 1269–1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bhattacharya R, Mukherjee P, Biological properties of “naked” metal nanoparticles, Adv Drug Deliv Rev 60(11) (2008) 1289–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Xia C, Pan J, Wang J, Pu Y, Zhang Q, Hu S, Hu Q, Wang Y, Functional blockade of cancer-associated fibroblasts with ultrafine gold nanomaterials causes an unprecedented bystander antitumoral effect, Nanoscale 12(38) (2020) 19833–19843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zhang Y, Elechalawar CK, Hossen MN, Francek ER, Dey A, Wilhelm S, Bhattacharya R, Mukherjee P, Gold nanoparticles inhibit activation of cancer-associated fibroblasts by disrupting communication from tumor and microenvironmental cells, Bioact Mater 6(2) (2021) 326–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mahmoudi MB, Bertrand N, Zope H, Farokhzad OC, Emerging understanding of the protein corona at the nano-bio interfaces, Nano Today 11 (2016) 817–832. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Arvizo RR, Rana S, Miranda OR, Bhattacharya R, Rotello VM, Mukherjee P, Mechanism of antiangiogenic property of gold nanoparticles: role of nanoparticle size and surface charge, Nanomedicine 7(5) (2011) 580–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gao Q, Zhang J, Gao J, Zhang Z, Zhu H, Wang D, Gold Nanoparticles in Cancer Theranostics, Front Bioeng Biotechnol 9 (2021) 647905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zheng YG, Wang JA, Meng L, Pei X, Zhang L, An L, Li CL, Miao YL, Design, synthesis, biological activity evaluation of 3-(4-phenyl-1H-imidazol-2-yl)-1H-pyrazole derivatives as potent JAK 2/3 and aurora A/B kinases multi-targeted inhibitors, Eur J Med Chem 209 (2021) 112934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Gysler SM, Drapkin R, Tumor innervation: peripheral nerves take control of the tumor microenvironment, J Clin Invest 131(11) (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Singleton DC, Macann A, Wilson WR, Therapeutic targeting of the hypoxic tumour microenvironment, Nat Rev Clin Oncol (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Behrens ME, Grandgenett PM, Bailey JM, Singh PK, Yi CH, Yu F, Hollingsworth MA, The reactive tumor microenvironment: MUC1 signaling directly reprograms transcription of CTGF, Oncogene 29(42) (2010) 5667–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Maman S, Witz IP, A history of exploring cancer in context, Nat Rev Cancer 18(6) (2018) 359–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Valkenburg KC, de Groot AE, Pienta KJ, Targeting the tumour stroma to improve cancer therapy, Nat Rev Clin Oncol 15(6) (2018) 366–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Sahai E, Astsaturov I, Cukierman E, DeNardo DG, Egeblad M, Evans RM, Fearon D, Greten FR, Hingorani SR, Hunter T, Hynes RO, Jain RK, Janowitz T, Jorgensen C, Kimmelman AC, Kolonin MG, Maki RG, Powers RS, Pure E, Ramirez DC, Scherz-Shouval R, Sherman MH, Stewart S, Tlsty TD, Tuveson DA, Watt FM, Weaver V, Weeraratna AT, Werb Z, A framework for advancing our understanding of cancer-associated fibroblasts, Nat Rev Cancer 20(3) (2020) 174–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Neiva KG, Warner KA, Campos MS, Zhang Z, Moren J, Danciu TE, Nor JE, Endothelial cell-derived interleukin-6 regulates tumor growth, BMC Cancer 14 (2014) 99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Zhang Z, Dong Z, Lauxen IS, Filho MS, Nor JE, Endothelial cell-secreted EGF induces epithelial to mesenchymal transition and endows head and neck cancer cells with stem-like phenotype, Cancer Res 74(10) (2014) 2869–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lu J, Ye X, Fan F, Xia L, Bhattacharya R, Bellister S, Tozzi F, Sceusi E, Zhou Y, Tachibana I, Maru DM, Hawke DH, Rak J, Mani SA, Zweidler-McKay P, Ellis LM, Endothelial cells promote the colorectal cancer stem cell phenotype through a soluble form of Jagged-1, Cancer Cell 23(2) (2013) 171–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Zhou W, Su Y, Zhang Y, Han B, Liu H, Wang X, Endothelial Cells Promote Docetaxel Resistance of Prostate Cancer Cells by Inducing ERG Expression and Activating Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway, Front Oncol 10 (2020) 584505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kalluri R, The biology and function of fibroblasts in cancer, Nat Rev Cancer 16(9) (2016) 582–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].De Palma M, Biziato D, Petrova TV, Microenvironmental regulation of tumour angiogenesis, Nat Rev Cancer 17(8) (2017) 457–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].De Leo A, Santini D, Ceccarelli C, Santandrea G, Palicelli A, Acquaviva G, Chiarucci F, Rosini F, Ravegnini G, Pession A, Turchetti D, Zamagni C, Perrone AM, De Iaco P, Tallini G, de Biase D, What Is New on Ovarian Carcinoma: Integrated Morphologic and Molecular Analysis Following the New 2020 World Health Organization Classification of Female Genital Tumors, Diagnostics (Basel) 11(4) (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kim HB, Lee HJ, Hong R, Park SG, Extremely rare case of successful treatment of metastatic ovarian undifferentiated carcinoma with high-dose combination cytotoxic chemotherapy: A case report, World J Clin Cases 8(19) (2020) 4488–4493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Eckert MA, Orozco C, Xiao J, Javellana M, Lengyel E, The Effects of Chemotherapeutics on the Ovarian Cancer Microenvironment, Cancers (Basel) 13(13) (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Domcke S, Sinha R, Levine DA, Sander C, Schultz N, Evaluating cell lines as tumour models by comparison of genomic profiles, Nat Commun 4 (2013) 2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Harrington BS, He Y, Davies CM, Wallace SJ, Adams MN, Beaven EA, Roche DK, Kennedy C, Chetty NP, Crandon AJ, Flatley C, Oliveira NB, Shannon CM, deFazio A, Tinker AV, Gilks CB, Gabrielli B, Brennan DJ, Coward JI, Armes JE, Perrin LC, Hooper JD, Cell line and patient-derived xenograft models reveal elevated CDCP1 as a target in high-grade serous ovarian cancer, Br J Cancer 114(4) (2016) 417–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Tudrej P, Kujawa KA, Cortez AJ, Lisowska KM, Characteristics of in Vivo Model Systems for Ovarian Cancer Studies, Diagnostics (Basel) 9(3) (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Zhang Y, Xiong X, Huai Y, Dey A, Hossen MN, Roy RV, Elechalawar CK, Rao G, Bhattacharya R, Mukherjee P, Gold Nanoparticles Disrupt Tumor Microenvironment-Endothelial Cell Cross Talk To Inhibit Angiogenic Phenotypes in Vitro, Bioconjug Chem 30(6) (2019) 1724–1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Roan F, Obata-Ninomiya K, Ziegler SF, Epithelial cell-derived cytokines: more than just signaling the alarm, J Clin Invest 129(4) (2019) 1441–1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Yang J, Antin P, Berx G, Blanpain C, Brabletz T, Bronner M, Campbell K, Cano A, Casanova J, Christofori G, Dedhar S, Derynck R, Ford HL, Fuxe J, Garcia de Herreros A, Goodall GJ, Hadjantonakis AK, Huang RJY, Kalcheim C, Kalluri R, Kang Y, Khew-Goodall Y, Levine H, Liu J, Longmore GD, Mani SA, Massague J, Mayor R, McClay D, Mostov KE, Newgreen DF, Nieto MA, Puisieux A, Runyan R, Savagner P, Stanger B, Stemmler MP, Takahashi Y, Takeichi M, Theveneau E, Thiery JP, Thompson EW, Weinberg RA, Williams ED, Xing J, Zhou BP, Sheng G, Association EMTI, Guidelines and definitions for research on epithelial-mesenchymal transition, Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 21(6) (2020) 341–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Xie Z, Bailey A, Kuleshov MV, Clarke DJB, Evangelista JE, Jenkins SL, Lachmann A, Wojciechowicz ML, Kropiwnicki E, Jagodnik KM, Jeon M, Ma’ayan A, Gene Set Knowledge Discovery with Enrichr, Curr Protoc 1(3) (2021) e90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Cao Z, Liao Q, Su M, Huang K, Jin J, Cao D, AKT and ERK dual inhibitors: The way forward?, Cancer Lett 459 (2019) 30–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lamouille S, Xu J, Derynck R, Molecular mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition, Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 15(3) (2014) 178–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Gonzalez DM, Medici D, Signaling mechanisms of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition, Sci Signal 7(344) (2014) re8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Maru Y, Hippo Y, Current Status of Patient-Derived Ovarian Cancer Models, Cells 8(5) (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ricci F, Broggini M, Damia G, Revisiting ovarian cancer preclinical models: implications for a better management of the disease, Cancer Treat Rev 39(6) (2013) 561–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Mebratu Y, Tesfaigzi Y, How ERK1/2 activation controls cell proliferation and cell death: Is subcellular localization the answer?, Cell Cycle 8(8) (2009) 1168–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Katopodis P, Chudasama D, Wander G, Sales L, Kumar J, Pandhal M, Anikin V, Chatterjee J, Hall M, Karteris E, Kinase Inhibitors and Ovarian Cancer, Cancers (Basel) 11(9) (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Loret N, Denys H, Tummers P, Berx G, The Role of Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Plasticity in Ovarian Cancer Progression and Therapy Resistance, Cancers (Basel) 11(6) (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Chekerov R, Hilpert F, Mahner S, El-Balat A, Harter P, De Gregorio N, Fridrich C, Markmann S, Potenberg J, Lorenz R, Oskay-Oezcelik G, Schmidt M, Krabisch P, Lueck HJ, Richter R, Braicu EI, du Bois A, Sehouli J, Noggo, A.T. Investigators, Sorafenib plus topotecan versus placebo plus topotecan for platinum-resistant ovarian cancer (TRIAS): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial, Lancet Oncol 19(9) (2018) 1247–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Shahin SA, Wang R, Simargi SI, Contreras A, Parra Echavarria L, Qu L, Wen W, Dellinger T, Unternaehrer J, Tamanoi F, Zink JI, Glackin CA, Hyaluronic acid conjugated nanoparticle delivery of siRNA against TWIST reduces tumor burden and enhances sensitivity to cisplatin in ovarian cancer, Nanomedicine 14(4) (2018) 1381–1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Hou L, Hou X, Wang L, Li Z, Xin B, Chen J, Gao X, Mu H, PD98059 impairs the cisplatin-resistance of ovarian cancer cells by suppressing ERK pathway and epithelial mesenchymal transition process, Cancer Biomark 21(1) (2017) 187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Patra CR, Bhattacharya R, Wang E, Katarya A, Lau JS, Dutta S, Muders M, Wang S, Buhrow SA, Safgren SL, Yaszemski MJ, Reid JM, Ames MM, Mukherjee P, Mukhopadhyay D, Targeted delivery of gemcitabine to pancreatic adenocarcinoma using cetuximab as a targeting agent, Cancer Res 68(6) (2008) 1970–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Giri K, Shameer K, Zimmermann MT, Saha S, Chakraborty PK, Sharma A, Arvizo RR, Madden BJ, McCormick DJ, Kocher JP, Bhattacharya R, Mukherjee P, Understanding protein-nanoparticle interaction: a new gateway to disease therapeutics, Bioconjug Chem 25(6) (2014) 1078–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Huang C, Fu C, Wren JD, Wang X, Zhang F, Zhang YH, Connel SA, Chen T, Zhang XA, Tetraspanin-enriched microdomains regulate digitation junctions, Cell Mol Life Sci 75(18) (2018) 3423–3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Weidner N, Semple JP, Welch WR, Folkman J, Tumor angiogenesis and metastasis--correlation in invasive breast carcinoma, N Engl J Med 324(1) (1991) 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Dai Q, Wilhelm S, Ding D, Syed AM, Sindhwani S, Zhang Y, Chen YY, MacMillan P, Chan WCW, Quantifying the Ligand-Coated Nanoparticle Delivery to Cancer Cells in Solid Tumors, ACS Nano 12(8) (2018) 8423–8435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Sindhwani S, Syed AM, Ngai J, Kingston BR, Maiorino L, Rothschild J, MacMillan P, Zhang Y, Rajesh NU, Hoang T, Wu JLY, Wilhelm S, Zilman A, Gadde S, Sulaiman A, Ouyang B, Lin Z, Wang L, Egeblad M, Chan WCW, The entry of nanoparticles into solid tumours, Nat Mater 19(5) (2020) 566–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].N.D.D. Lee Joanne C., Mao Angelina S., Karim Amber, Komarneni Mallikharjuna, Thomas Emily E., Francek Emmy R., Yang Wen, and Wilhelm Stefan, Exploring Maleimide-Based Nanoparticle Surface Engineering to Control Cellular Interactions, ACS Appl. Nano Mater 3(3) (2020) 2421–2429. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.