Key Points

Question

Are exposure to e-cigarette advertising and parental and peer influence associated with e-cigarette use among US adolescents?

Findings

This cohort study of a total of 11 641 adolescents from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health study waves 4, 4.5, and 5, found that adolescents who reported past 30-day e-cigarette advertising exposure and who reported having best friends using e-cigarettes were more likely to feel curious about using e-cigarettes and more likely to initiate e-cigarette use at follow-up.

Meaning

These findings suggest that efforts to address youth vaping need to consider peer influence and incorporate measures reducing e-cigarette advertising exposure.

This cohort study examines how e-cigarette advertising exposure and parental and peer e-cigarette use are associated with e-cigarette use among US adolescents.

Abstract

Importance

Little is known about the roles of advertising and parental and peer influence in e-cigarette use among US adolescents in recent years, hindering efforts to address the increasing rate of youth vaping.

Objective

To examine how e-cigarette advertising exposure and parental and peer e-cigarette use were associated with e-cigarette use among US adolescents.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study used data from waves 4 (December 2016 to January 2018), 4.5 (December 2017 to December 2018), and 5 (December 2018 to November 2019) of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health study, an on-going cohort study representative of the noninstitutionalized US population. Sample weights were applied to generate nationally representative estimates. Data were analyzed in January 2022.

Exposures

Past 30-day e-cigarette advertising exposure, past 30-day parental e-cigarette use, and the number of best friends using e-cigarettes (none, a few, some, most, and all).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Outcomes were contemporary curiosity about using e-cigarettes and e-cigarette initiation at follow-up. Generalized estimating equations were used to estimate the weighted adjusted associations.

Results

Wave 4 included 8548 adolescents; wave 4.5, 10 073 adolescents; and wave 5, 11 641 adolescents. Among adolescents in the wave 4 survey, 4425 (51.1%) were boys, 1935 (24.9%) were aged 12 years, 1105 (13.0%) were Black, 2515 (24.4%) were Hispanic, and 3702 (52.3%) were White. More than 60% of adolescents reported past 30-day e-cigarette advertising exposure at each survey. Among adolescents who had never used e-cigarettes, those who reported e-cigarette advertising exposure were more likely to feel curious about using e-cigarettes (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.56 [95% CI, 1.43-1.70]) and were more likely to become ever e-cigarette users (aOR, 1.21 [95% CI, 1.05-1.41]) and current e-cigarette users (aOR, 1.42 [95% CI, 1.16-1.75]) at follow-up. Adolescents who reported having best friends using e-cigarettes were more likely to feel curious about using e-cigarettes (eg, all best friends: aOR, 4.13 [95% CI, 2.35-7.26]) and initiate e-cigarette use at follow-up (eg, among adolescents reporting all best friends use e-cigarettes, risk of ever use: aOR, 4.08 [95% CI, 1.44-11.59]; risk of current use aOR, 5.42 [95% CI, 1.49-19.72]) than adolescents who reported having no best friends using e-cigarettes.

Conclusions and Relevance

This cohort study of US adolescents found that e-cigarette advertising and peer influence were significantly associated with e-cigarette initiation. Efforts to address youth vaping need to consider peer influence and incorporate measures reducing e-cigarette advertising exposure.

Introduction

In 2014, e-cigarettes surpassed combustible cigarettes and became the most commonly used tobacco product among US adolescents.1,2,3,4 The 2021 National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) estimated that more than 2 million adolescents (11.3% of high school students and 2.8% of middle school students) in the US currently used e-cigarettes.4 The popularity of e-cigarettes among US youth has been attributed to e-cigarette’s sleek and stealth product designs and availability of a wide varieties of flavors appealing to youth.5,6 Importantly, marketing has also played a critical role in popularizing e-cigarettes among adolescents.7,8,9,10,11 It is noteworthy that much of e-cigarette marketing has been documented by previous studies to be youth-targeted.5,7,8 For example, a 2017 study by Padon et al7 collected 154 e-cigarette video advertisements and found all advertisements included some youth-appealing content. The e-cigarette giant, JUUL, has been criticized for using young models and youth-appealing content in its social media marketing campaigns and accused of being responsible, at least in part, for the surge in youth vaping.8,12,13,14 Data from the NYTS showed that 78.2% of middle and high school students were exposed to e-cigarette advertising in 2016, increased from 68.9% in 2014.15

Previous studies have indicated that e-cigarette advertising exposure was significantly associated with e-cigarette use and susceptibility among US adolescents.9,10,16,17,18 Data from the 2014 NYTS showed that exposure to each channel of e-cigarette advertising (internet, print, retail, and TV and movies) was significantly associated with ever or current e-cigarette use, as well as susceptibility to use among never e-cigarette users.16,18 A randomized trial conducted among adolescents who were e-cigarette naive showed that exposure to e-cigarette TV advertisements increased intentions to use e-cigarettes.17 A 2018 study by Camenga et al10 used longitudinal data collected from middle and high school students in Connecticut and found that exposure to e-cigarette advertising on Facebook was associated with higher odds of subsequent e-cigarette use.10

e-Cigarettes have been regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a tobacco product since the final deeming rule was issued in 2016.19 Steps have been taken to restrict youth access to e-cigarettes and curb e-cigarette marketing aimed at youth since then.20,21,22,23,24 It has been reported that some e-cigarette companies withdrew certain flavored products and suspended certain youth-targeted marketing activities in response to the heighted scrutiny from the FDA.25,26 However, changes of e-cigarette advertising exposure in the context of a rapidly changing regulatory environment have not been examined, and little is known about how e-cigarette advertising exposure was associated with e-cigarette use and susceptibility among US adolescents in recent years.

Additionally, previous studies investigating factors associated with adolescents’ e-cigarette use did not fully consider the potential influence of parental and peer e-cigarette use behaviors. Current evidence about associations of parental and peer use with tobacco use is almost entirely from studies of cigarettes and other tobacco products,27,28 with most of these studies focusing on the associations between adolescents’ cigarette smoking and the smoking status of their friends.28,29,30 A few studies have suggested that a similar pattern exists for e-cigarettes31,32; however, these studies relied primarily on regional data collected from convenience samples. Nationally representative studies are needed to estimate the associations between parental and peer e-cigarette use and adolescents’ e-cigarette use outcomes.

To fill these critical research gaps, this study uses data from the most recent 3 waves of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study surveys to examine trends of overall e-cigarette advertising exposure and advertising exposure from specific media channels among US adolescents and how e-cigarette advertising exposure and parental and peer e-cigarette use were associated with contemporary curiosity about using e-cigarettes and future e-cigarette initiation at follow-up among adolescents who had never used e-cigarettes. We hypothesized that e-cigarette advertising exposure was still high among US adolescents despite recent FDA regulatory actions restricting certain youth-targeted e-cigarette advertising and that e-cigarette advertising exposure and parental and peer use of e-cigarettes were significantly associated with e-cigarette use and susceptibility.

Methods

This cohort study is a secondary analysis of the PATH study and was exempt from ethical review by the Georgia State University institutional review board because the data were deidentified. This PATH study was approved by the Westat institutional review board. Written informed consents were obtained from all study participants and parents (if applicable). This study is reported following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Data

Data used in this study were from the PATH study Youth Cohort wave 4 (December 2016 to January 2018), wave 4.5 (December 2017 to December 2018), and wave 5 (December 2018 to November 2019) surveys. The PATH study is an ongoing, nationally representative longitudinal study conducted by the National Institutes of Health and the FDA. Data collection was conducted by Westat. Detailed information on the study design and sampling strategies can be found elsewhere.33 The weighed response rate for the wave 4 cohort was 89.1% at wave 4.5 survey, and 83.5% at wave 5 survey. Since the data collection for these 3 waves of surveys were mainly conducted in 2017, 2018, and 2019, respectively, survey year was used for each wave to show the trends of e-cigarette advertising exposure. Study sample were adolescents (age 12-17 years) with wave 4 cohort all-wave weights. Answers like “Refused” and “I don’t know” were coded as missing values, and pair-wise deletion was used to handle missing values.

Measures

Adolescents’ e-cigarette advertising exposure was measured as past 30-day any exposure and exposure through multiple channels. Respondents were asked “In the past 30 days, have you noticed e-cigarettes or other electronic nicotine products being advertised in any of the following places? Choose all that apply.” with answer options “I haven’t seen any advertisements in the past 30 days,” “At gas stations, convenience stores, or other retail stores” (coded as stores), “On billboards” (coded as billboards), “In newspapers or magazines” (coded as print), “On radio” (coded as radio), “On television” (coded as TV), “At events such as fairs, festivals, or sporting events” (coded as events), “At nightclubs, bars, or music concerts” (coded as clubs or bars), “On websites or social media sites” (coded as online), and “Somewhere else.” No other options could be selected together with the first option. Adolescents who did not select the first option and selected any of the following options were coded as having past 30-day e-cigarette advertising exposure. Parental use was measured by parental past 30-day e-cigarette use. Peer use was measured by respondents’ reports of how many of their best friends used e-cigarettes (none, a few, some, most, or all).

The outcomes were contemporary curiosity about using e-cigarettes and e-cigarette initiation at the 12-month follow-up. Adolescents who had never used e-cigarettes were asked if they had ever been curious about using an e-cigarette. Those who answered very, somewhat, or a little were coded as yes, and those who answered not at all were coded as no. e-Cigarette initiation was measured as ever use and current (past 30-day) use at follow-up among baseline never users.

Other covariates included in this study were biological sex (boy and girl), age in years, race and ethnicity (categorized as Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, and other), highest parental education (less than high school, high school graduate, some college or associate degree, and bachelor’s degree and above), severity of internalizing and externalizing mental health problems (low, moderate, and high), perception of harm from e-cigarette use (no harm, little harm, some harm, and a lot of harm), current (past 30-day) cigarette smoking status,34,35 and current (past 30-day) use of other tobacco products (cigar, pipe, hookah, bidi, kretek, and smokeless tobacco, including snus and dissolvable products).36,37 Race and ethnicity, which were self-reported by study participants, were included as a covariate since previous studies have indicated that race and ethnicity are significantly associated with adolescents’ e-cigarette use behaviors.4,5 The other racial and ethnic groups included Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Guamanian or Chamorro, Japanese, Korean, non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, other Asian, other Pacific Islander, Samoan, and Vietnamese. Measures for adolescents’ mental health conditions were based on screening questions asking adolescents’ symptoms pertinent to mental health problems in the PATH study. Specifically, there were 4 items for internalizing symptoms and 7 items for externalizing symptoms. For each item, adolescents who had experienced significant problems with it in the past 12 months were coded as 1 and others were coded as 0. Scores for internalizing and externalizing problems were summed up respectively and categorized to low (0-1), moderate (2-3), and high (≥4) severity.38,39

Statistical Analysis

Data management and analysis were conducted using Stata statistical software version 16.1 (StataCorp). Wave 4 cohort all-wave weights were applied to account for the complex sampling strategies and nonresponse rates and to generate nationally representative estimates. Prevalence of any past 30-day e-cigarette advertising exposure and exposure from the 8 channels (ie, stores, billboards, print, radio, TV, events, clubs or bars, and online) were estimated separately for the full study sample and for adolescents who had never used e-cigarettes (eFigure in the Supplement). Generalized estimating equations were used to estimate the adjusted associations between exposures and each outcome, controlling for all specified covariates, study wave, and participant’s state of residence. All statistical tests were 2-tailed with significance level set at α = .05. Data were analyzed in January 2022.

Results

Sociodemographic Factors of Study Sample

The sample size was 8548 participants for wave 4, 10 073 participants for wave 4.5, and 11 641 participants for wave 5. The sample size increased because youth aged 9 to 11 years aged up and joined the youth cohort at each wave (eFigure in the Supplement). Among adolescents in the wave 4 survey, 4425 (51.1%) were boys, 1935 (24.9%) were aged 12 years, 1105 (13.0%) were Black, 2515 (24.4%) were Hispanic, and 3702 (52.3%) were White. The distributions of sex and race and ethnicity did not change significantly across study waves. During the study period, the prevalence of ever e-cigarette use increased from 9.0% (95% CI, 8.4%-9.7%) of participants in wave 4 to 19.9% (95% CI, 19.1%-20.6%) of participants in wave 5. Report of parental past 30-day e-cigarette use increased from 3.9% (95% CI, 3.5%-4.4%) of participants in wave 4 to 5.2% (95% CI, 4.8%-5.6%) of participants in wave 5. Adolescents who reported none of their best friends using e-cigarettes decreased from 84.3% (95% CI, 83.4%-85.1%) of participants in wave 4 to 63.4% (95% CI, 62.5%-64.4%) of participants in wave 5 (eTable in the Supplement).

e-Cigarette Advertising Exposure

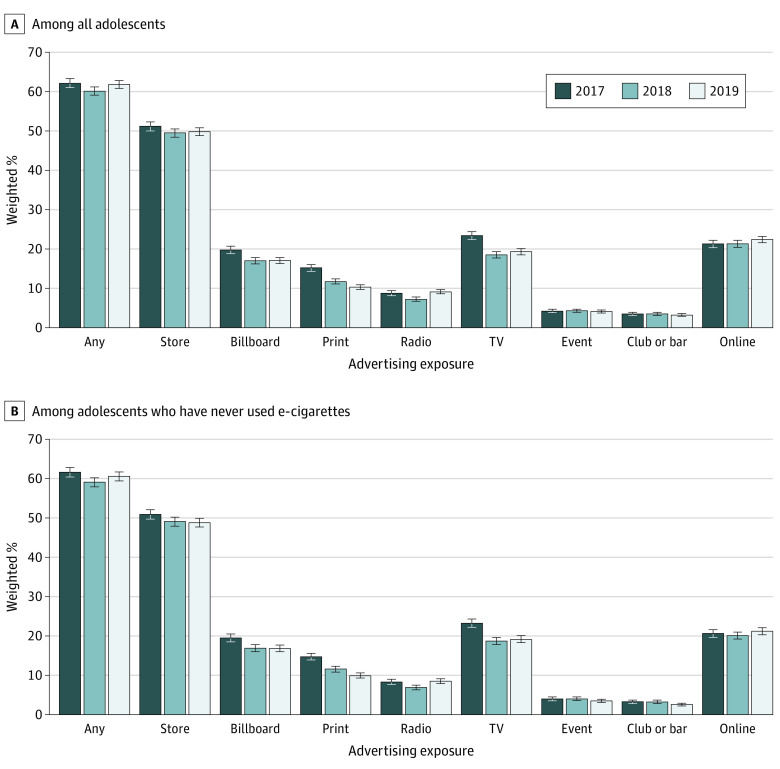

Figure 1 shows the prevalence of any e-cigarette advertising exposure and exposure from multiple channels in the past 30 days among all participating adolescents and among adolescents who had never used e-cigarettes. It was estimated that more than 60% of US adolescents reported exposure to e-cigarette advertising in the past 30 days at each survey during the study period. In 2017, exposure was highest in stores (51.2% [95% CI, 50.0%-52.3%] of participants), followed by TV (23.4% [95% CI, 22.4%-24.4%] of participants), online (21.3% [95% CI, 20.3%-22.2%] of participants), and billboards (19.7% [95% CI, 18.8%-20.7%]). Advertising exposure from stores and online did not change significantly from 2017 to 2019. Exposure from billboard and TV decreased from 2017 to 2018 but did not change significantly from 2018 to 2019. Exposure from print media decreased from 15.2% (95% CI, 14.3%-16.0%) in 2017 to 9.1% (95% CI, 8.6%-9.7%) in 2019. The prevalence of e-cigarette advertising exposure and trends were similar for adolescents who had never used e-cigarettes compared with all adolescent respondents.

Figure 1. Prevalence of Past 30-Day e-Cigarette Advertising Exposure Among US Adolescents, 2017-2019.

Factors Associated With Curiosity About Using e-Cigarettes

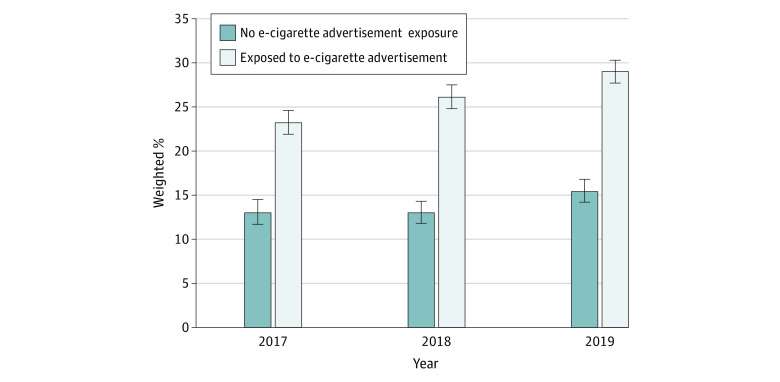

Bivariate associations showed that among adolescents who had never used e-cigarettes, those who reported any past 30-day e-cigarette advertising exposure were more likely to feel curious about using e-cigarettes compared with adolescents who reported no exposure (2017: 23.2% [95% CI, 21.9%-24.6%] of participants vs 13.0% [95% CI, 11.7%-14.5%] of participants; 2018: 26.1% [95% CI, 24.8%-27.5%] of participants vs 13.0% [95% CI, 11.8%-14.3%] of participants; 2019: 29.0% [95% CI, 27.7%-30.3%] of participants vs 15.4% [95% CI, 14.2%-16.8%] of participants) (Figure 2). Adjusted regression analysis showed consistent results (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.56 [95% CI, 1.43-1.70]) (Table 1).

Figure 2. Proportion of Adolescents Feeling Curious About Using e-Cigarettes by e-Cigarette Advertising Exposure Status.

Table 1. Adjusted Associations of Curiosity in Using e-Cigarettes With e-Cigarette Advertising Exposure, Parental Effect, and Peer Effect.

| Factor | OR (95% CI)a |

|---|---|

| Past 30-d any e-cigarette advertising exposureb | 1.56 (1.43-1.70) |

| Parental e-cigarette useb | 1.27 (1.03-1.56) |

| Friends using e-cigarettes | |

| None | 1 [Reference] |

| A few | 2.60 (2.36-2.86) |

| Some | 3.40 (2.91-3.96) |

| Most | 4.96 (3.90-6.31) |

| All | 4.13 (2.35-7.26) |

| Perception of harm from e-cigarette use | |

| No harm | 2.73 (2.00-3.72) |

| Little harm | 3.93 (3.45-4.49) |

| Some harm | 2.43 (2.24-2.65) |

| A lot of harm | 1 [Reference] |

| Sex | |

| Boys | 0.91 (0.83-1.00) |

| Girls | 1 [Reference] |

| Age, y | |

| 12 | 1 [Reference] |

| 13 | 1.17 (1.03-1.33) |

| 14 | 1.39 (1.23-1.58) |

| 15 | 1.51 (1.33-1.73) |

| 16 | 1.32 (1.13-1.55) |

| 17 | 1.31 (1.07-1.61) |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| Black | 0.97 (0.83-1.13) |

| Hispanic | 1.10 (0.97-1.24) |

| White | 1 [Reference] |

| Otherc | 1.03 (0.88-1.21) |

| Parental education | |

| <High school | 1 [Reference] |

| High school graduate | 0.88 (0.76-1.02) |

| Some college or associate degree | 0.96 (0.84-1.10) |

| ≥Bachelor’s degree | 1.03 (0.90-1.19) |

| Severity of internalizing mental health problems | |

| Low | 1 [Reference] |

| Moderate | 1.31 (1.19-1.45) |

| High | 1.57 (1.40-1.76) |

| Severity of externalizing mental health problems | |

| Low | 1 [Reference] |

| Moderate | 1.61 (1.44-1.79) |

| High | 2.28 (2.03-2.55) |

| Current cigarette smokingb | 1.43 (0.78-2.60) |

| Current use of other tobacco productsb | 2.05 (1.14-3.68) |

| Wave | |

| 4 | 0.76 (0.68-0.83) |

| 4.5 | 0.81 (0.75-0.88) |

| 5 | 1 [Reference] |

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

Participant state of residence was controlled for.

Reference group was those who answered no.

Other included Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Guamanian or Chamorro, Japanese, Korean, Native Hawaiian, non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native, other Asian, other Pacific Islander, Samoan, and Vietnamese.

Adolescent never e-cigarette users with parents currently using e-cigarettes were more likely to feel curious about using e-cigarettes (aOR, 1.27 [95% CI, 1.03-1.56]). Compared with adolescents who reported none of their best friends using e-cigarettes, adolescents were more likely to feel curious about using e-cigarettes if they reported that a few (aOR, 2.60 [95% CI, 2.36-2.86]), some (aOR, 3.40 [95% CI, 2.91-3.96]), most (aOR, 4.96 [95% CI, 3.90-6.31]), or all (aOR, 4.13 [95% CI, 2.35-7.26]) of their best friends used e-cigarettes (Table 1).

Factors Associated With e-Cigarette Initiation at Follow-up

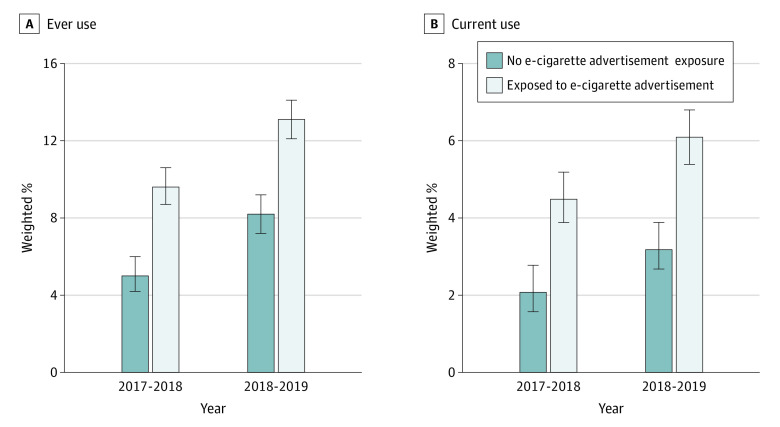

Figure 3 shows the bivariate associations between baseline e-cigarette advertising exposure and e-cigarette initiation at follow-up among adolescents who had never used e-cigarettes at baseline. Adolescents who reported e-cigarette advertising exposure, compared with those who reported no exposure, were more likely to become ever e-cigarette users (2018: 9.6% [95% CI, 8.7%-10.6%] of participants vs 5.0% [95% CI, 4.2%-6.0%] of participants; 2019: 13.1% [95% CI, 12.1%-14.1%] of participants vs 8.2% [95% CI, 7.2%-9.2%] of participants) and current e-cigarette users (2018: 4.5% [95% CI, 3.9%-5.2%] of participants vs 2.1% [95% CI, 1.6%-2.8%] of participants; 2019: 6.1% [95% CI, 5.4%-6.8%] of participants vs 3.2% [95% CI, 2.7%-3.9%] of participants) at follow-up. Adjusted associations showed consistent results at follow-up for ever e-cigarette use (aOR, 1.21 [95% CI, 1.05-1.41]) and current e-cigarette use (aOR, 1.42 [95% CI, 1.16-1.75]) (Table 2).

Figure 3. Proportion of e-Cigarette Initiation at Follow-up by Baseline e-Cigarette Advertising Exposure Status.

Table 2. Adjusted Associations of e-Cigarette Initiation at Follow-up With Baseline Past 30-Day e-Cigarette Advertising Exposure, Parental Use, and Peer Use.

| Factor | e-Cigarette use, OR (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|

| Ever | Current | |

| Past 30-d any e-cigarette advertising exposureb | 1.21 (1.05-1.41) | 1.42 (1.16-1.75) |

| Parental e-cigarette useb | 1.33 (0.96-1.85) | 1.10 (0.71-1.68) |

| Friends using e-cigarettes | ||

| None | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| A few | 2.69 (2.27-3.18) | 2.27 (1.81-2.85) |

| Some | 3.69 (2.91-4.68) | 3.35 (2.45-4.58) |

| Most | 4.56 (3.14-6.63) | 4.40 (2.77-7.00) |

| All | 4.08 (1.44-11.59) | 5.42 (1.49-19.72) |

| Perception of harm from e-cigarette use | ||

| No harm | 2.44 (1.55-3.84) | 3.21 (1.78-5.80) |

| Little harm | 2.56 (2.10-3.13) | 2.01 (1.53-2.65) |

| Some harm | 1.50 (1.30-1.73) | 1.27 (1.04-1.56) |

| A lot of harm | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Sex | ||

| Boys | 0.89 (0.78-1.02) | 0.83 (0.69-0.99) |

| Girls | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Age, y | ||

| 12 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 13 | 2.33 (1.79-3.02) | 2.99 (2.00-4.45) |

| 14 | 2.69 (2.09-3.47) | 3.26 (2.20-4.84) |

| 15 | 3.11 (2.41-4.03) | 4.10 (2.77-6.08) |

| 16 | 2.66 (1.98-3.59) | 3.73 (2.40-5.80) |

| 17 | 3.74 (1.15-12.15) | 4.98 (1.20-20.61) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| Black | 0.39 (0.30-0.50) | 0.33 (0.23-0.47) |

| Hispanic | 0.70 (0.58-0.85) | 0.70 (0.54-0.92) |

| White | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Otherc | 0.62 (0.49-0.78) | 0.56 (0.40-0.79) |

| Parental education | ||

| Less than high school | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| High school graduate | 0.89 (0.71-1.13) | 0.91 (0.65-1.28) |

| Some college or associate degree | 0.98 (0.79-1.20) | 0.87 (0.65-1.18) |

| Bachelor's degree or above | 0.93 (0.75-1.16) | 0.79 (0.58-1.09) |

| Severity of internalizing mental health problems | ||

| Low | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Moderate | 1.11 (0.94-1.31) | 1.05 (0.83-1.31) |

| High | 1.28 (1.06-1.54) | 1.07 (0.83-1.39) |

| Severity of externalizing mental health problems | ||

| Low | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Moderate | 1.39 (1.16-1.67) | 1.29 (1.01-1.66) |

| High | 1.83 (1.51-2.22) | 1.89 (1.46-2.44) |

| Current cigarette smokingb | 2.55 (1.29-5.06) | 2.26 (0.91-5.59) |

| Current use of other tobacco productsb | 3.42 (1.67-6.99) | 4.80 (2.09-11.05) |

| Wave period | ||

| 4 to 4.5 | 0.78 (0.68-0.89) | 0.83 (0.69-1.01) |

| 4.5 to 5 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

Participant state of residence was also controlled for.

Reference group was those who answered no.

Other included Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Guamanian or Chamorro, Japanese, Korean, Native Hawaiian, non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native, other Asian, other Pacific Islander, Samoan, and Vietnamese.

Compared with those who reported none of their best friends using e-cigarettes, baseline never e-cigarette users were more likely to become ever users if they reported a few (aOR, 2.69 [95% CI, 2.27-3.18]), some (aOR, 3.69 [95% CI, 2.91-4.68]), most (aOR, 4.56 [95% CI, 3.14-6.63]), or all (aOR, 4.08 [95% CI, 1.44-11.59]) of their best friends used e-cigarettes. Similar findings were found for risk of becoming current users among adolescents who reported a few (aOR, 2.27 [95% CI, 1.81-2.85]), some (aOR, 3.35 [95% CI, 2.45-4.58]), most (aOR, 4.40 [95% CI, 2.77-7.00]) or all (aOR, 5.42 [95% CI, 1.49-19.72]) of their best friends used e-cigarettes (Table 2).

Discussion

This cohort study using nationally representative longitudinal data provides important evidence on trends of e-cigarette advertising exposure from 2017 to 2019 and on how e-cigarette advertising and parental and peer e-cigarette use were associated with e-cigarette initiation and susceptibility among US adolescents. Our study results show that, despite measures taken to regulate e-cigarette companies’ youth-targeted marketing, e-cigarette advertising exposure was still high among US adolescents, regardless of their e-cigarette use status, and e-cigarette advertising exposure and peer use of e-cigarettes were significantly associated with contemporary curiosity about using e-cigarettes and future e-cigarette initiation among adolescents who had never used e-cigarettes.

Consistent with previous findings,10,15 we also found that e-cigarette advertising exposure was highest at point-of-sale (ie, stores: 49.8% of participants in 2019), suggesting the presence of a high level of e-cigarette marketing by e-cigarette companies in retail settings. In addition, our study found that TV, online, and billboards were also major sources of e-cigarette advertising exposure among US youth. Importantly, although overall e-cigarette advertising exposure, and exposure from TV, billboards, and print media decreased from 2017 to 2018, the overall level of e-cigarette advertising exposure in 2019 was comparable with that in 2017. In addition, despite the FDA’s intense regulatory scrutiny of e-cigarette companies’ advertising on social media, online e-cigarette advertising exposure did not change significantly during our study period. The decrease in e-cigarette advertising from 2017 to 2018 was likely due to the heightened federal regulations.21,23,24 For example, it was reported that, beginning in early 2018, the US FDA and the Federal Trade Commission issued multiple warning letters to e-cigarette companies and retailers for promoting e-cigarette products in ways misleading to youth or selling e-cigarette products to youth illegally.23,40 The FDA also took actions to prevent youth access to e-cigarette products.21,23,24,40,41 However, despite these efforts, our study findings suggest that the level of exposure to e-cigarette advertising, both overall and via specific channels (eg, online), was still high among adolescents in our study period. More targeted efforts may be needed to reduce youth e-cigarette advertising exposure.

Our study also found that adolescent never e-cigarette users who reported any past 30-day e-cigarette advertising exposure were significantly more likely to feel curious about using e-cigarettes and more likely to initiate e-cigarette use at 1-year follow-up. Existing literature has documented the powerful influence associated with e-cigarette advertising in increasing adolescents’ intentions to use and use of e-cigarettes.9,10,16,17 Our findings demonstrated that even in a context of intensified regulatory environment with heightened scrutiny of youth-targeted e-cigarette marketing, e-cigarette companies could still find ways to get around these regulations to market their products to adolescents, which in turn may increase adolescents’ e-cigarette use and susceptibility. These findings suggest that stronger and more comprehensive regulations may be needed to reduce e-cigarette advertising exposure and prevent e-cigarette initiation for US adolescents. The World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control called for a comprehensive ban on tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship in 2003.42 In 2014, the World Health Organization specifically called for restrictions on e-cigarette marketing to protect the health of youth and nonsmokers.43 Policies that regulate youth-oriented e-cigarette marketing would benefit from incorporating the comprehensive approaches proposed by the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control.

Peer influence is one of the key factors that can affect adolescent cigarette smoking.28,29,30 Our study also found that having best friends using e-cigarettes was associated with higher odds of e-cigarette initiation and susceptibility, consistent with what has been reported previously using convenience samples.31,32 According to multiple health theories and models,44,45,46 perceived peer approval and use of substances play key roles in influencing early stages of substance use during adolescence. Our findings indicate that these theories and models are also applicable to e-cigarette use. These findings suggest that efforts to change social norms toward e-cigarettes and to communicate the risks of e-cigarette use during adolescence are needed as part of a comprehensive strategy to reverse the evolving trend of youth vaping in the US.

Contrary to our initial hypothesis, we found that baseline parental e-cigarette use was not significantly associated with adolescents’ e-cigarette initiation at 1-year follow-up, suggesting youth vaping behaviors may be more in sync with the behavior of their peers than their parents.6,47,48 This finding may be explained in part by the source of e-cigarettes for youth, which came primarily from their peers.48 Additionally, the small sample percentage of parents who used e-cigarettes may be also a factor.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, this study used self-reported data, which may induce recall bias and social desirability bias. Second, despite the temporal association, this study design could not establish a causal relationship. Third, although we controlled for a variety of covariates, other potential confounders may still exist and were not accounted for in our models. Furthermore, this study conducted multiple hypothesis tests without α correction.

Conclusions

This cohort study found that e-cigarette advertising exposure was high among US adolescents between 2017 and 2019, regardless of their e-cigarette using status. e-Cigarette advertising exposure and peer use of e-cigarettes were significantly associated with contemporary curiosity about using e-cigarettes and future e-cigarette initiation among adolescents who had never used e-cigarettes. Efforts to address the increasing use of vaping among youth need to consider peer influence and incorporate measures reducing e-cigarette advertising exposure.

eFigure. Flowchart of Analytical Sample

eTable. Descriptive Statistics of Study Sample

References

- 1.Cullen KA, Ambrose BK, Gentzke AS, Apelberg BJ, Jamal A, King BA. Notes from the field: use of electronic cigarettes and any tobacco product among middle and high school students—United States, 2011–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(45):1276-1277. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6745a5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang TW, Gentzke AS, Creamer MR, et al. Tobacco product use and associated factors among middle and high school students—United States, 2019. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2019;68(12):1-22. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6812a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang TW, Neff LJ, Park-Lee E, Ren C, Cullen KA, King BA. e-Cigarette use among middle and high school students—United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(37):1310-1312. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6937e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park-Lee E, Ren C, Sawdey MD, et al. Notes from the field: e-cigarette use among middle and high school students—National Youth Tobacco Survey, United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(39):1387-1389. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7039a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Department of Health and Human Services . 2016 Surgeon General’s Report: e-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perikleous EP, Steiropoulos P, Paraskakis E, Constantinidis TC, Nena E. e-Cigarette use among adolescents: an overview of the literature and future perspectives. Front Public Health. 2018;6:86. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Padon AA, Maloney EK, Cappella JN. Youth-targeted e-cigarette marketing in the US. Tob Regul Sci. 2017;3(1):95-101. doi: 10.18001/TRS.3.1.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang J, Duan Z, Kwok J, et al. Vaping versus JUULing: how the extraordinary growth and marketing of JUUL transformed the US retail e-cigarette market. Tob Control. 2019;28(2):146-151. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Angelo H, Patel M, Rose SW. Convenience store access and e-cigarette advertising exposure is associated with future e-cigarette initiation among tobacco-naïve youth in the PATH study (2013-2016). J Adolesc Health. 2021;68(4):794-800. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Camenga D, Gutierrez KM, Kong G, Cavallo D, Simon P, Krishnan-Sarin S. e-Cigarette advertising exposure in e-cigarette naïve adolescents and subsequent e-cigarette use: a longitudinal cohort study. Addict Behav. 2018;81:78-83. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duan Z, Wang Y, Emery SL, Chaloupka FJ, Kim Y, Huang J. Exposure to e-cigarette TV advertisements among U.S. youth and adults, 2013-2019. PLoS One. 2021;16(5):e0251203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hammond D, Wackowski OA, Reid JL, O’Connor RJ. Use of JUUL e-cigarettes among youth in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(5):827-832. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nty237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Office of the Surgeon General . Surgeon General’s advisory on e-cigarette use among youth. Accessed October 11, 2021. https://e-cigarettes.surgeongeneral.gov/documents/surgeon-generals-advisory-on-e-cigarette-use-among-youth-2018.pdf

- 14.Dyer O. e-Cigarette maker Juul pays $40m to North Carolina in landmark settlement. BMJ. 2021;374:n1669. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marynak K, Gentzke A, Wang TW, Neff L, King BA. Exposure to electronic cigarette advertising among middle and high school students—United States, 2014–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(10):294-299. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6710a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dai H, Hao J. Exposure to advertisements and susceptibility to electronic cigarette use among youth. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(6):620-626. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farrelly MC, Duke JC, Crankshaw EC, et al. A randomized trial of the effect of e-cigarette TV advertisements on intentions to use e-cigarettes. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(5):686-693. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mantey DS, Cooper MR, Clendennen SL, Pasch KE, Perry CL. e-Cigarette marketing exposure is associated with e-cigarette use among US youth. J Adolesc Health. 2016;58(6):686-690. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Food and Drug Administration; HHS . Deeming tobacco products to be subject to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act; restrictions on the sale and distribution of tobacco products and required warning statements for tobacco products: final rule. Fed Regist. 2016;81(90):28973-29106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hammond D, Reid JL, Burkhalter R, Rynard VL. e-Cigarette marketing regulations and youth vaping: cross-sectional surveys, 2017–2019. Pediatrics. 2020;146(1):e20194020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-4020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Food and Drug Administration . Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., on new enforcement actions and a Youth Tobacco Prevention Plan to stop youth use of, and access to, JUUL and other e-cigarettes. Accessed September 15, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/statement-fda-commissioner-scott-gottlieb-md-new-enforcement-actions-and-youth-tobacco-prevention

- 22.US Food and Drug Administration . FDA announces comprehensive regulatory plan to shift trajectory of tobacco-related disease, death. Accessed September 15, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-announces-comprehensive-regulatory-plan-shift-trajectory-tobacco-related-disease-death

- 23.US Food and Drug Administration . FDA, FTC take action against companies misleading kids with e-liquids that resemble children’s juice boxes, candies and cookies. Accessed September 15, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-ftc-take-action-against-companies-misleading-kids-e-liquids-resemble-childrens-juice-boxes

- 24.US Food and Drug Administration . Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., on proposed new steps to protect youth by preventing access to flavored tobacco products and banning menthol in cigarettes. Accessed September 15, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/statement-fda-commissioner-scott-gottlieb-md-proposed-new-steps-protect-youth-preventing-access

- 25.Liber A, Cahn Z, Larsen A, Drope J. Flavored e-cigarette sales in the United States under self-regulation from January 2015 through October 2019. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(6):785-787. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allem J-P, Dharmapuri L, Unger JB, Cruz TB. Characterizing JUUL-related posts on Twitter. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;190:1-5. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.05.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barnett TE, Curbow BA, Weitz JR, Johnson TM, Smith-Simone SY. Water pipe tobacco smoking among middle and high school students. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(11):2014-2019. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.151225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffman BR, Monge PR, Chou C-P, Valente TW. Perceived peer influence and peer selection on adolescent smoking. Addict Behav. 2007;32(8):1546-1554. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Urberg KA, Shyu S-J, Liang J. Peer influence in adolescent cigarette smoking. Addict Behav. 1990;15(3):247-255. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90067-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoffman BR, Sussman S, Unger JB, Valente TW. Peer influences on adolescent cigarette smoking: a theoretical review of the literature. Subst Use Misuse. 2006;41(1):103-155. doi: 10.1080/10826080500368892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Durkin K, Williford DN, Turiano NA, et al. Associations between peer use, costs and benefits, self-efficacy, and adolescent e-cigarette use. J Pediatr Psychol. 2021;46(1):112-122. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barrington-Trimis JL, Berhane K, Unger JB, et al. Psychosocial factors associated with adolescent electronic cigarette and cigarette use. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):308-317. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-0639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hyland A, Ambrose BK, Conway KP, et al. Design and methods of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study. Tob Control. 2017;26(4):371-378. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-052934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wills TA, Knight R, Sargent JD, Gibbons FX, Pagano I, Williams RJ. Longitudinal study of e-cigarette use and onset of cigarette smoking among high school students in Hawaii. Tob Control. 2017;26(1):34-39. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duan Z, Wang Y, Huang J. Sex difference in the association between electronic cigarette use and subsequent cigarette smoking among US adolescents: findings from the PATH study waves 1–4. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):1695. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Y, Duan Z, Emery SL, Kim Y, Chaloupka FJ, Huang J. The association between e-cigarette price and TV advertising and the sales of smokeless tobacco products in the USA. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(13):6795. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18136795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shahab L, Beard E, Brown J. Association of initial e-cigarette and other tobacco product use with subsequent cigarette smoking in adolescents: a cross-sectional, matched control study. Tob Control. 2021;30(2):212-220. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Conway KP, Green VR, Kasza KA, et al. Co-occurrence of tobacco product use, substance use, and mental health problems among adults: findings from wave 1 (2013-2014) of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;177:104-111. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.03.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duan Z, Wang Y, Spears CA, et al. Role of mental health in the association between e-cigarettes and cannabis use. Am J Prev Med. 2022;62(3):307-316. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.US Food and Drug Administration . Warning letters and civil money penalties issued to retailers for selling JUUL and other e-cigarettes to minors. Accessed September 15, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/ctp-newsroom/warning-letters-and-civil-money-penalties-issued-retailers-selling-juul-and-other-e-cigarettes

- 41.Rogers K. The FDA is launching an anti-JUUL campaign that’s like D.A.R.E. for vaping. Vice. September 18, 2018. Accessed September 15, 2020. https://www.vice.com/en/article/zm5nw4/the-fda-is-launching-an-anti-juul-campaign-thats-like-dare-for-vaping

- 42.World Health Organization . WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 43.World Health Organization . WHO report on regulation of e-cigarettes and similar products. BMJ Blog. August 27, 2014. Accessed August 29, 2022. https://blogs.bmj.com/tc/2014/08/27/who-report-on-regulation-of-e-cigarettes-and-similar-products/

- 44.Bandura A, Walters RH. Social Learning Theory. Prentice Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179-211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52(1):1-26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leung RK, Toumbourou JW, Hemphill SA. The effect of peer influence and selection processes on adolescent alcohol use: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Health Psychol Rev. 2014;8(4):426-457. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2011.587961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krishnan-Sarin S, Morean ME, Camenga DR, Cavallo DA, Kong G. e-Cigarette use among high school and middle school adolescents in Connecticut. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(7):810-818. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Flowchart of Analytical Sample

eTable. Descriptive Statistics of Study Sample