Abstract

PURPOSE OF REVIEW

Anti–myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) autoantibodies have become a recognized cause of a pathophysiologically distinct group of central nervous system (CNS) autoimmune diseases. MOG-associated disorders can easily be confused with other CNS diseases such as multiple sclerosis or neuromyelitis optica, but they have a distinct clinical phenotype and prognosis.

RECENT FINDINGS

Most patients with MOG-associated disorders exhibit optic neuritis, myelitis, or acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) alone, sequentially, or in combination; the disease may be either monophasic or relapsing. Recent case reports have continued to expand the clinical spectrum of disease, and increasingly larger cohort studies have helped clarify its pathophysiology and natural history.

SUMMARY

Anti–MOG-associated disorders comprise a substantial subset of patients previously thought to have other seronegative CNS diseases. Accurate diagnosis is important because the relapse patterns and prognosis for MOG-associated disorders are unique. Immunotherapy appears to successfully mitigate the disease, although not all agents are equally effective. The emerging large-scale data describing the clinical spectrum and natural history of MOG-associated disorders will be foundational for future therapeutic trials.

INTRODUCTION

Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG)–associated disorders (also known as MOGAD) are relative newcomers to neuroimmunology, having only been recognized as pathologic since around 2015. The full scope and clinical implications of the diagnosis are still emerging. MOG autoantibodies were initially thought to distinguish a subset of aquaporin-4 (AQP4)-negative neuromyelitis optica (NMO) cases. It soon became clear that the antibodies were also detectable among patients with acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), recurrent optic neuritis, and autoimmune encephalitis, and the clinical spectrum of MOG-associated disorders has continued to expand. In vitro and animal work established the pathogenic capacity of the autoantibodies, and MOG autoantibodies are now considered indicative of a distinct disease rather than representing a bystander marker of CNS inflammation.

This review first discusses how anti-MOG autoantibody–associated disorders came to be recognized as a pathophysiologically distinct disease. It then summarizes the epidemiology, pathology, and immunobiology of MOG-associated disorders. Last, it examines the various clinical features of MOG-associated disorders and discusses diagnostic and treatment approaches.

EMERGENCE OF MYELIN OLIGODENDROCYTE GLYCOPROTEIN–ASSOCIATED DISORDERS

MOG is a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily that resides on the outer lamellae of central nervous system (CNS) myelin sheaths. Its anatomical juxtaposition with the extracellular space suggested that it could interface with immune cells, and, accordingly, much attention centered on MOG in the early era of neuroimmunology. Injecting laboratory animals with MOG peptides and adjuvant led to demyelinating CNS pathology, termed experimental autoimmune encephalitis. Injecting animals with MOG-reactive T cells, likewise, could recapitulate demyelinating pathology, implicating this moiety in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis (MS) and other inflammatory demyelinating diseases. Attempts to identify anti-MOG antibodies in the serum and CSF of humans with neuroimmune diseases, however, yielded inconsistent results. Some detected high frequencies of anti-MOG antibodies in patients with MS,1 whereas others detected anti-MOG antibodies in other inflammatory CNS conditions as well as in healthy controls.2,3 Ultimately, most concluded that, although MOG autoantibodies could be detected in the circulation for a variety of neuroimmune disorders, they were neither sensitive nor specific.

This paradigm shifted in 2007, when O’Connor and colleagues4 demonstrated that, when the three-dimensional structure of the MOG immunoglobulin domain was retained, specific anti-MOG antibodies could be detected in a subset of individuals with ADEM but not in those with MS, suggesting a pathologic association. Shortly thereafter, Waters and colleagues5 found that cell-based assays using IgG1-specific secondary antibodies increased specificity for clinically relevant anti-MOG autoantibodies and that live cell–based assays were superior to fixed cell–based assays.6 The refinement of live cell–based assays made it clear that IgG1-specific MOG-reactive autoantibodies were associated with distinct pathophysiology and that earlier failures to identify them were because of technical limitations and not the biology of disease (FIGURE 8–1). When cell-based assays for anti-MOG autoantibodies became clinically available in 2018, many patients previously diagnosed with other types of “seronegative” CNS demyelinating disorders were reclassified as having MOG-associated disorders, as exemplified by the patient in CASE 8–1.

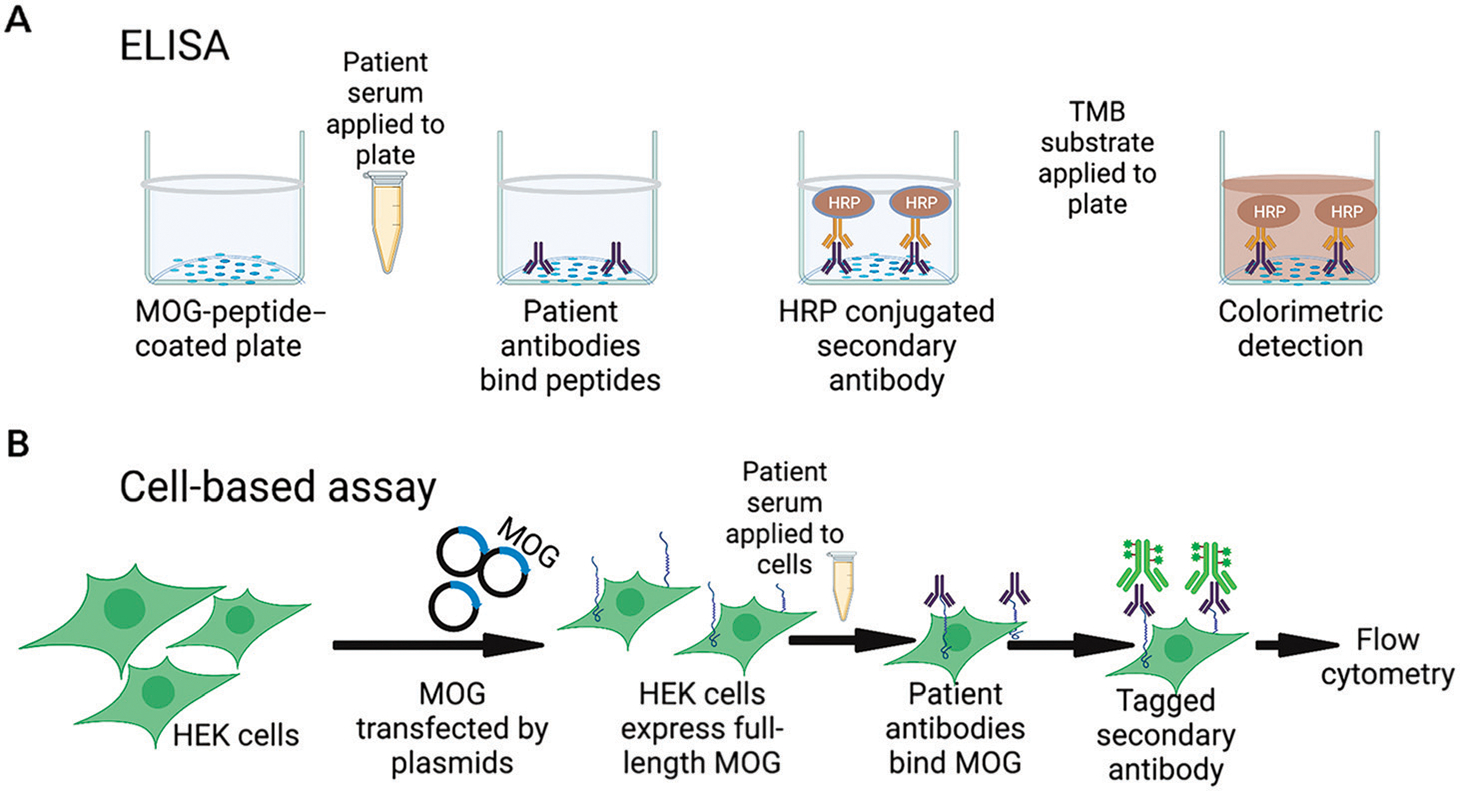

FIGURE 8–1.

Laboratory techniques for identifying MOG autoantibodies. A, In enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), plates are coated with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) peptide. Patient serum is applied, followed by a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody. Application of 3,3′,5,5′- tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate causes a colorimetric reaction when bound antibody is present, which is measured on a plate reader. B, For cell-based assays, full-length MOG is transfected into a living human cell line, translated and expressed on the cell surface. Patient serum is applied, and any anti-MOG antibodies present can bind the protein in its native conformation. Fluorescently tagged secondary antibodies are applied (these may be isotype-specific) and quantified using flow cytometry.

HEK = human embryonic kidney cells.

Figure created with BioRender.

CASE 8–1

A 35-year-old woman developed bilateral optic neuritis at age 23 and experienced a second bout of unilateral optic neuritis combined with bilateral leg weakness 3 months after her first attack. A longitudinally extensive spine lesion was identified, and she was diagnosed with neuromyelitis optica, although testing for aquaporin-4 was negative. She was placed on rituximab. While on therapy, she continued to have relapses of optic neuritis approximately every 12 months.

Anti–myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibody testing was performed when the test was commercialized in 2018, 5 years after her initial diagnosis, and she tested positive with a titer of 1:1000. She was reclassified as having MOG-associated disorder, and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) 1 g/kg every 4 weeks was added to her treatment regimen. On combination therapy, she had fewer relapses of optic neuritis and continued to have good clinical recovery after each relapse. At her last clinic visit, her visual acuity was 20/25 in both eyes, but optical coherence tomography testing demonstrated severe thinning of bilateral optic nerves and reduction of the retinal nerve fiber layer thickness.

COMMENT

Although the diagnosis was not made for several years, this case illustrates several clinical features typical for MOG-associated disorders. The patient had both sequential and multifocal episodes of central nervous system demyelination, and her second event developed shortly after her first, a timeframe of high risk for MOG-associated disorder relapses. Although she appeared to respond to maintenance immunotherapy, disease control was suboptimal, and she continued to have relapses even while on rituximab. Subsequent combination therapy (rituximab and IVIg) provided better efficacy for her. Patients with MOG-associated disorders often have good visual recovery after optic neuritis, but axonal damage may be severe, and the measurable atrophy of this patient’s retinal nerve fiber layer places her at high risk for visual loss later in life, especially if she continues to experience frequent relapses.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND CLINICAL COURSE OF MYELIN OLIGODENDROCYTE GLYCOPROTEIN–ASSOCIATED DISORDERS

Unlike MS and AQP4-positive NMO spectrum disorders (NMOSD), MOG-associated disorders have no clear sex predilection. Males and females appear to be similarly impacted; some studies have observed a slight female preponderance. MOG-associated disorders are more common in children than in adults, with an estimated pediatric incidence of around 3.1 per 1 million compared with an estimated adult incidence between 1.6 and 2.39 per 1 million.7,8 Although the median age of onset is in the early to midthirties, the disease has a bimodal distribution. The pediatric population represents about 35% of cases, with a second peak occurring in young/midadulthood9,10 To date, MOG-associated disorders have been described most commonly in White individuals, although larger and more systematic epidemiologic work is needed.11 No strong genetic associations with the human leukocyte antigen complex have been identified, unlike with some other demyelinating diseases12; however, large-scale genetic studies have not yet been performed.

KEY POINTS.

Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG)-associated disorders represent a unique subset of central nervous system demyelinating diseases that is pathophysiologically distinct from multiple sclerosis and aquaporin-4–positive neuromyelitis optica.

The evolution of more advanced laboratory techniques was foundational to the identification of MOG-associated disorders as a distinct disease entity. Live cell–based assays are the gold standard for detecting anti-MOG autoantibodies.

MOG-associated disorders have a bimodal distribution, with children representing about one-third of cases and a second peak occurring in young/midadulthood. Males and females appear equally at risk.

MOG-associated disorders may follow either a monophasic or relapsing course. Studies have estimated the likelihood of relapsing disease to be anywhere from 37% to 95%, and the true risk for recurrent relapse is not yet clear.10,13–16 Observational studies with longer follow-up periods have generally observed high relapse rates; 95% of patients followed for at least 8 years had relapsing disease.14 However, these studies are likely subject to attrition bias, as individuals remaining relapse-free without immunosuppressive therapy are less likely to maintain long-term follow-up. As illustrated in CASE 8–1, relapses often emerge soon after the initial event; one study found that about 40% of affected individuals had their second clinical event within 2 years17 and another reported a median time to second event of just 5 months.17,18 The risk of relapse may be impacted by age at presentation and serostatus. Adults were at a higher overall risk of relapse compared with children (hazard ratio, 1.41 in one study of 98 children and 268 adults), whereas children younger than the age of 10 had the lowest risk of relapse.17,19 Seroconversion to MOG-autoantibody negative, which occurs in around 14% to 57% of cases, may be associated with a decreased risk of relapse, although one of the largest studies looking at seroconversion found that it decreased relapse risk only for children and not for adults.17,19–21 Although MOG-associated optic neuritis has been frequently associated with a relapsing course,14 multivariable models controlling for age, disability status, and maintenance therapy did not find clinical phenotype to be a significant predictor of future relapses.17

MOG-associated disorders may emerge in the setting of infections (mainly viral) and, extremely rarely, vaccination. Although the overall proportion of postinfectious cases is not known, MOG-associated disorders have been associated with a wide variety of infectious organisms, including influenza,22 Epstein-Barr virus,23 herpes simplex virus,24 severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2),25 human herpes virus 6,26,27 Borrelia,27 measles,28 Zika virus,29 Mycoplasma pneumoniae,30 and unspecified infections.18 That the disease can arise in the aftermath of such diverse microorganisms argues against the sole mechanism being molecular mimicry and may instead suggest an epiphenomenon associated with robust immune activation and/or disruption of the blood-brain barrier. Whether postinfectious MOG-associated disorders subsequently predispose affected individuals to follow a monophasic course is not yet clear. A few cases of MOG-associated disorders arising after vaccines (diphtheria/pertussis/tetanus, polio, COVID-19, and influenza) have been reported, but these are too few to draw any conclusions regarding causality.18,31

KEY POINTS.

MOG-associated disorders may be monophasic or relapsing; the clinical course is not yet possible to predict at the time of the incident event.

MOG-associated disorders may arise in a postinfectious setting, but they are not strongly associated with any single organism.

MOG-associated disorders do not overlap with multiple sclerosis or aquaporin-4–positive neuromyelitis optica. They may rarely overlap with antibody-mediated autoimmune encephalitis.

MOG-associated disorders are not strongly linked to other systemic autoimmune disorders or circulating autoantibodies such as antinuclear antibody, extractable nuclear antibodies and anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies, which distinguishes them from other CNS demyelinating diseases such as AQP4-positive NMOSD and, to a lesser extent, MS.32 Moreover, MOG autoantibodies are typically not found in individuals with MS or AQP4-positive NMOSD18,33 but have rarely been identified in individuals with autoantibody-mediated autoimmune encephalitis. Cooccurrence has been most often reported with anti–N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antibodies, although anti–contactin-associated proteinlike 2 (CASPR2), glycine, leucine-rich, glioma inactivated 1 (LgI1), γ-aminobutyric acid A (GABAA), and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) autoantibodies have also been detected in parallel with anti-MOG antibodies.34–36 Although MOG-associated disorders are typically not paraneoplastic, they have been recognized concurrently with malignancies including lung adenocarcinoma,37 T-cell lymphoma,38 and teratoma39 on rare occasions.

Similar to MS and AQP4-positive NMO, emerging data suggest that pregnancy may be relatively protective against MOG-associated disorder relapses. The largest pregnancy case series to date included 30 women with MOG-associated disorders.40 None of these patients had a relapse during pregnancy, and most returned to their prepregnancy level of disease activity after delivery. More study is needed, encompassing larger numbers of patients and more systematic data collection.

PATHOLOGY OF MYELIN OLIGODENDROCYTE GLYCOPROTEIN–ASSOCIATED DISORDERS

Histologic features of MOG-associated disorders include perivenular and confluent white matter and cortical demyelination. Perivascular and parenchymal lymphocyte infiltrates are common, particularly within early/active lesions, where myelin-laden macrophages also abound. Meningeal inflammation is common and is topographically associated with cortical demyelination; complement deposition also occurs.41 Although astrogliosis is widespread, dystrophic astrocytes are not typically seen in MOG-associated disorders, and axons generally remain intact. Both AQP4 and MOG expression are preserved.42–44

The pathologic appearance of MOG-associated disorders is distinct from that of MS and AQP4-positive NMOSD. When compared with patients with MS, patients with MOG-associated disorders exhibited a higher incidence of intracortical demyelinating lesions with associated microglial infiltration. Patients with MOG-associated disorders did not exhibit the “chronic active” lesions with well-defined microglial/macrophage rims or slowly expanding/smoldering white matter lesions that are typical of MS. Unlike the CD8+-dominated lymphocyte infiltrate seen within and around MS lesions, lymphocyte infiltrates in MOG-associated disorders were predominantly composed of CD4+ T cells, with CD8+ T cells and CD20+ B cells present in smaller numbers. Granulocytes, specifically neutrophils and eosinophils, also reside within MOG-associated disorder intraparenchymal lesions.42–44 MOG-associated disorder pathobiology is distinguished from AQP4-positive NMOSD in that astrocyte morphology and AQP4 expression are preserved, necrosis and extensive granulocytic cell infiltrates are absent, and complement and immunoglobulin deposits are infrequent. Cortical demyelination is more frequently observed in MOG-associated disorders compared with AQP4-positive NMOSD.44–46

IMMUNOBIOLOGY OF MYELIN OLIGODENDROCYTE GLYCOPROTEIN–ASSOCIATED DISORDERS

Disease-specific anti-MOG antibodies are of the IgG1 subtype and recognize a conformational epitope located on the extracellular MOG domain.47,48 Most autoantibodies bind a Proline42 epitope, although additional epitopes may also contribute, particularly in relapsing disease.49 The epitopes recognized by human anti-MOG antibodies remain stable over time, although antibody titers fluctuate and are typically higher during disease exacerbations compared with remission.49 Anti-MOG autoantibodies appear to be generated in the periphery, and serologic testing is more sensitive than CSF testing for detecting them.50 Indeed, intrathecal IgG synthesis (evidenced by CSF-restricted oligoclonal bands) is only rarely detected in MOG-associated disorders.17

IgG1 autoantibodies, including those targeting MOG, are capable of mediating complement activation and cell-mediated cytotoxicity.51 To evaluate the cytotoxic potential of human anti-MOG antibodies, serum from individuals with MOG-associated disorders was administered to rats with experimental autoimmune encephalitis, which worsened their clinical disease and increased the amount of observed demyelination and axonal loss.52,53 Others observed that serum from pediatric patients with MOG-associated disorders disrupted F-actin and β-tubulin networks in immortalized oligodendrocyte cells.54 In vitro evidence also suggests that MOG autoantibodies disrupt the blood-brain barrier.55 These data support diverse pathologic roles for anti-MOG antibodies in autoimmune demyelinating diseases.

A variety of systemic immunologic changes have been observed in patients with MOG-associated disorders. Many of these vary between acute relapses and periods of remission. During relapses, elevated serum interleukin 1β levels and a pronounced Th1/Th17 phenotype in circulating T cells emerge.56–58 Patients with MOG-associated disorders were also more likely to exhibit elevated B cell–related cytokines/chemokines such as CXCL13, APRIL, BAFF, and CCL19 in their CSF compared with seronegative patients with similar clinical phenotypes.59

CLINICAL PHENOTYPES OF MYELIN OLIGODENDROCYTE GLYCOPROTEIN–ASSOCIATED DISORDERS

MOG-associated disorders overlap phenotypically with a variety of neuroimmune syndromes that lack serum biomarkers, including seronegative NMO, MS, ADEM, transverse myelitis, and chronic relapsing inflammatory optic neuritis. All of these are diagnoses of exclusion, and testing for known biomarkers (eg, anti-MOG, anti-AQP4) is an important part of the workup for any patient presenting with inflammatory CNS disease. Individual patients should be diagnosed according to the most specific data available; when MOG autoantibodies are discovered in an individual who has a congruent clinical phenotype, that individual should be classified as having a MOG-associated disorder, regardless of whether they also meet McDonald criteria for MS or Wingerchuk criteria for seronegative NMO.60 Correctly classifying inflammatory CNS diseases is crucial for selecting effective treatment modalities.

KEY POINTS.

MOG-associated disorders have pathologic findings that are distinct from multiple sclerosis and aquaporin-4–positive neuromyelitis optica.

MOG autoantibody titers frequently fluctuate over time and are higher during exacerbations compared with during remission.

Patients with MOG autoantibodies and a congruent clinical phenotype should be diagnosed with MOG-associated disease, regardless of whether they also meet clinical criteria for a different neuroimmune disease. Identification of specific autoantibodies takes diagnostic precedence over clinical diagnoses of exclusion.

MOG-associated disorders occupy a broad clinical spectrum, with the most common phenotypes being optic neuritis, myelitis, and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM).

Optic neuritis and myelitis associated with MOG-associated disorders often have unique clinical, laboratory, or radiologic features that distinguish them from other central nervous system autoimmune diseases.

The most common clinical manifestations of MOG-associated disorders are optic neuritis, ADEM, and myelitis, either alone or in combination. Multifocal presentations are common; one study found that up to 32% of patients with MOG-associated disorders have had multifocal relapses with the combination of optic neuritis and myelitis being the most common.18 Patients with relapsing disease may sequentially exhibit different clinical phenotypes of MOG-associated disorders as well. In the following sections, unique characteristics of the most common clinical manifestations are considered, and then some of the more unusual presentations of MOG-associated disorders are discussed.

Optic Neuritis

Optic neuritis is the most common manifestation of MOG-associated disorders, appearing in about 41% of pediatric patients and 56% of adult patients.17 Within the pediatric population, optic neuritis tends to be seen mainly in older children, and it is almost never observed in children younger than 5 years. MOG-associated optic neuritis is frequently recurrent and bilateral; it may present simultaneously or sequentially with myelitis or another MOG-associated clinical phenotype. Most patients manifesting with optic neuritis maintain persistent MOG seropositivity and follow a relapsing course over time.17,61 Among adults, White people were more likely than Asian people to have either recurrent optic neuritis or extraoptic nerve central nervous system manifestations, although no differences in visual outcomes were noted.62

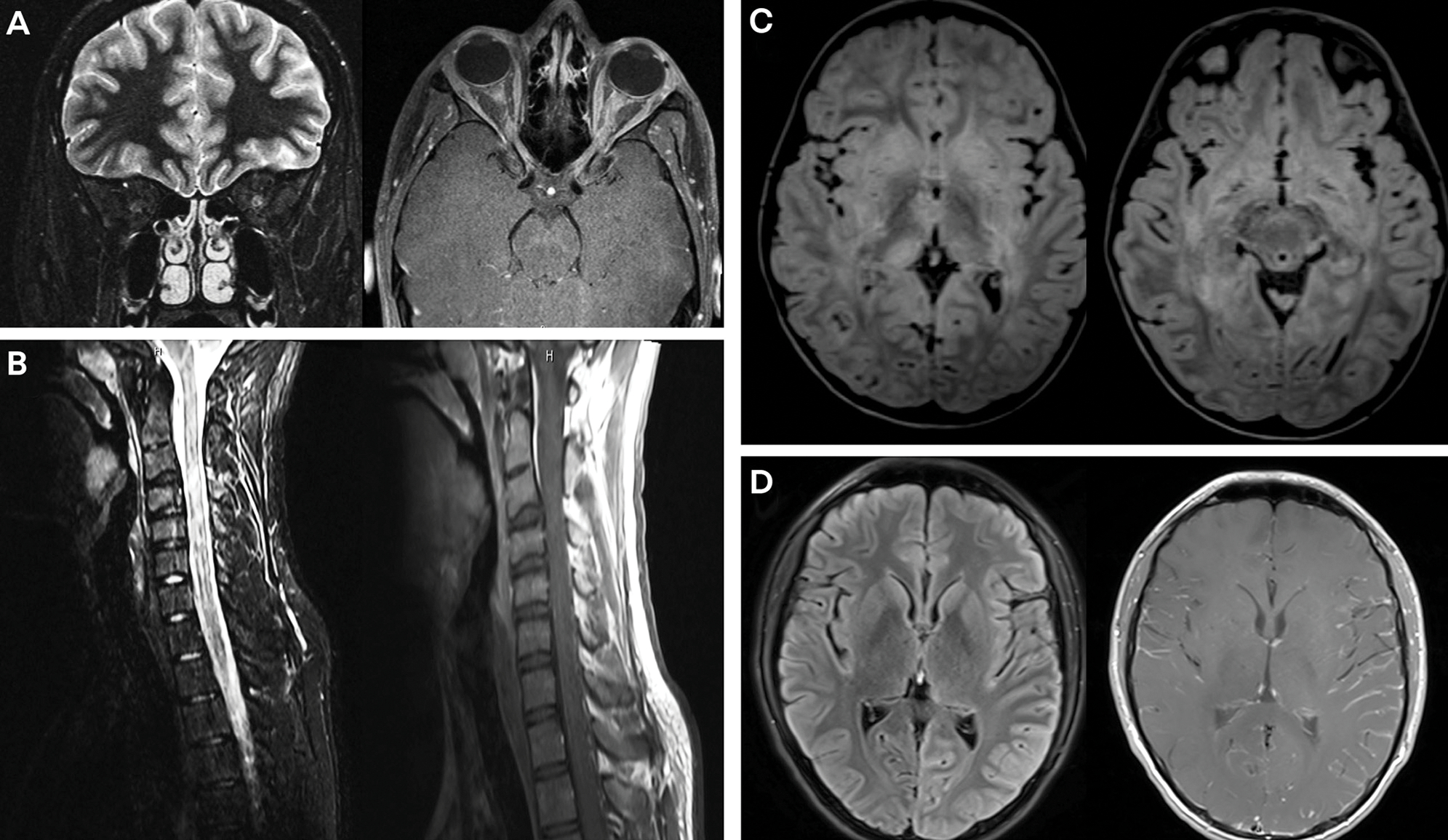

On examination, optic disc edema and peripapillary hemorrhages are common.61,63 Longitudinally extensive optic nerve involvement, frequently with associated perineural enhancement, is seen on MRI in the majority of cases, and involvement of the optic chiasm may be observed (up to 15% of patients with MOG-associated disorders) (FIGURE 8–2A).64,65

FIGURE 8–2.

MRI findings associated with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) phenotypes. A, Coronal (left) T2-weighted image and axial (right) postgadolinium T1-weighted image demonstrate bilateral optic neuritis with T2 hyperintensity and mild diffuse enhancement of the bilateral optic nerves. B, Sagittal short tau inversion recovery (STIR) (left) and postgadolinium T1-weighted (right) images demonstrate longitudinally extensive cervical spine lesions with minimal associated enhancement. C, Axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images demonstrate bilateral hemispheric white matter lesions with involvement of bilateral basal ganglia and thalami in a child with acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM). D, Axial FLAIR (left) and postgadolinium T1-weighted (right) images demonstrate diffuse left hemispheric cortical FLAIR signal changes with associated diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement in a patient with encephalopathy.

UNIQUE FEATURES OF MYELIN OLIGODENDROCYTE GLYCOPROTEIN–ASSOCIATED DISORDER-ASSOCIATED OPTIC NEURITIS.

Several clinical signs and symptoms distinguish MOG-associated optic neuritis from that caused by MS or AQP4-positive NMOSD. Headache is frequently present, and this may precede visual symptoms by several days.66 Optic disc edema and peripapillary hemorrhages also suggest a diagnosis of MOG-associated optic neuritis. Long-segment optic nerve lesions often distinguish MOG-associated disease from AQP4-positive NMOSD and MS.64 Vision loss is frequently severe at nadir for both MOG-associated and AQP4-positive NMOSD optic neuritis, but recovery of visual acuity is usually better for MOG-associated disorders.67 Despite this, patients of all ages with MOG-associated optic neuritis have thin retinal nerve fiber layers, suggesting that they remain at risk for permanent vision loss with future attacks.67,68

Myelitis

Myelitis is another common manifestation of MOG-associated disorders that may occur alone or in parallel with another clinical MOG-associated disorder syndrome. Like in CASE 8–2, myelitis associated with MOG-associated disorders frequently arises in the setting of prodromal illness, assumed to be viral. As with any myelitis, patients may experience weakness, a sensory level, bladder/bowel dysfunction, and spasticity. A minority instead present with symptoms reminiscent of acute flaccid myelitis and demonstrate flaccid areflexia instead of the more common upper motor neuron syndrome. In contrast to enterovirus D68–associated acute flaccid myelitis, MOG-associated cases often responded well to short-term immunotherapy.69

CASE 8–2

An 18-year-old man presented with a 5-day history of subacute progressive bilateral leg weakness and numbness. He reported having mild upper respiratory tract symptoms about 2 weeks before the onset of weakness. Neurologic examination revealed mild bilateral hip flexor weakness (4/5) and sensory deficits to light touch, temperature, and pain below the level of T4. This progressed over 3 days to flaccid paraplegia.

MRI revealed a nonenhancing, longitudinally extensive spinal cord lesion that extended from the medulla to the conus. Brain and orbital MRIs were normal. CSF testing showed a lymphocytic pleocytosis with a cell count of 350/mm3 and protein of 62 mg/dL. Serum anti–myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibodies were positive at 1:5000. The patient was admitted to the hospital, where he received IV steroids and plasma exchange.

He required a wheelchair at the time of his discharge to a rehabilitation unit. Over the next 3 months, his symptoms gradually improved, and he reported that he had no residual neurologic symptoms when he returned to the outpatient neurology clinic in follow-up. Repeat blood testing showed an anti-MOG titer of 1:100 at 6 months and was negative at 1 year. No residual T2 lesions were detectable on follow-up MRI of his spine performed at 1 year. He was not started on maintenance immunotherapy.

COMMENT

This patient developed symptoms of myelitis in a parainfectious setting, which is a common clinical scenario for adult patients with MOG-associated disorders. The very high cell count in his CSF is atypical for MS and aquaporin-4–positive neuromyelitis optica but is frequently seen in MOG-associated disorders and should increase the clinical suspicion for this diagnosis once infectious etiologies are considered and ruled out. He had excellent clinical and radiologic recovery from his incident attack, and his MOG antibodies eventually converted to seronegative. An underlying MOG-associated disorder diagnosis may suggest a better prognosis for recovery from longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis than other disease entities causing this clinical phenotype. In the absence of confirmed relapsing disease, maintenance immunotherapy is not definitely indicated although continued clinical follow-up is desirable. Should he develop a new clinical manifestation of a MOG-associated disorder in the future, maintenance immunotherapy would be warranted.

On MRI, patients with MOG-associated disorders often exhibit multiple spinal lesions. These may be either short-segment or longitudinally extensive (three or more spinal segments) and can involve the cord anywhere from the medulla to the conus (FIGURE 8–2B). Gadolinium enhancement is uncommon and, if present, is typically faint. Disproportionate spinal cord gray matter involvement is often present, visualized as an H pattern in the axial plane and a linear central T2 hyperintensity in the sagittal plane. Atrophy is uncommon, and spinal imaging abnormalities may resolve after clinical recovery.69 Interestingly, patients with MOG-associated disorders may exhibit spinal lesions in the absence of a myelitis phenotype, indicating that not all imaging abnormalities have a clinical correlate.36

KEY POINT.

MOG-associated disorders can overlap the clinical spectrum of neuromyelitis optica, but MOG autoantibodies and aquaporin-4 autoantibodies do not colocalize within an individual.

UNIQUE FEATURES OF MYELITIS IN MYELIN OLIGODENDROCYTE GLYCOPROTEIN–ASSOCIATED DISORDERS.

Clinical clues suggestive of MOG-associated myelitis include the viral prodrome, which is more often seen with MOG-associated disorders than with other CNS demyelinating diseases. Characteristic imaging features, too, can suggest MOG-associated disorders. In particular, the lack of gadolinium enhancement and the restriction of lesions to gray matter were the strongest radiologic predictors of myelitis associated with MOG-associated disorders as opposed to that caused by MS or AQP4-positive NMOSD.69

Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder

In the absence of AQP4 autoantibodies, NMOSD requires at least one of the following clinical syndromes for diagnosis: optic neuritis, longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis, or area postrema syndrome (intractable nausea/vomiting/hiccups). A second, different clinical syndrome confirming dissemination in space must also be documented; in addition to the classic syndromes listed above, the second syndrome could be an acute brainstem syndrome, symptomatic narcolepsy, an acute diencephalic syndrome, or a symptomatic cerebral syndrome with characteristic brain lesions.70 A subset of patients with MOG-associated disorders meet clinical criteria for NMOSD; it is estimated that between 7% and 42% of seronegative patients with NMOSD have anti-MOG autoantibodies and would be more accurately classified as having MOG-associated disorders.33,71,72 Indeed, simultaneous optic neuritis and myelitis or bilateral optic neuritis appear to be even more common for MOG-associated disorders than for AQP4-positive NMO.18 Area postrema syndrome, however, is unusual for MOG-associated disorders.73 Despite the clinical overlap, AQP4 autoantibodies and MOG autoantibodies do not colocalize within an individual.33

Acute Demyelinating Encephalomyelitis

The clinical phenotype of ADEM includes fever, headaches, irritability, fatigue, encephalopathy, seizures, brainstem/cerebellar dysfunction, and other neurologic symptoms. Pediatric patients with MOG-associated disorders are highly likely to present with ADEM, especially those younger than 10 years of age. As age increases, the likelihood of an ADEM-like presentation decreases.17 MRI typically reveals bilateral supratentorial brain lesions, which may affect both subcortical and deep white matter, along with involvement of the deep gray nuclei such as the basal ganglia and the thalamus. Lesions are usually large (greater than 2 cm), poorly demarcated, and best visualized using fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) or T2-weighted sequences (FIGURE 8–2C). Parenchymal contrast enhancement is common during relapses. ADEM-related MRI changes frequently resolve entirely on follow-up imaging.74 MOG autoantibody testing is warranted during the diagnostic workup for all pediatric patients with ADEM, particularly for those younger than 10 years of age.

Focal Encephalitis

Rarely, MOG-associated disorders can present with focal encephalitis that may be associated with decreased consciousness, seizures/status epilepticus, and focal weakness. MRI reveals hyperintense cortical FLAIR lesions that appear swollen and are usually unilateral.75–78 Corresponding leptomeningeal enhancement may be visible (FIGURE 8–2D).25 This clinical phenotype has been termed FLAMES (FLAIR-hyperintense lesions in anti-MOG-associated encephalitis with seizures).79

Atypical Encephalitis

A subset of encephalopathic patients with MOG autoantibodies do not meet ADEM criteria or exhibit a focal encephalitis syndrome (eg, FLAMES79). These patients present with altered consciousness, seizures, or a brainstem syndrome. MRI findings for patients with atypical encephalitis may include bilateral cortical MRI abnormalities and/or isolated deep gray matter (thalamic or basal ganglia) involvement. A small number of patients exhibit minimal brain MRI changes, despite dramatic clinical phenotypes that may include refractory status epilepticus.36

Progressive Leukodystrophy

A few cases have been described of MOG autoantibody–positive individuals, typically children, whose MRIs were suggestive of genetic leukodystrophies. Some of these patients initially presented with an ADEM phenotype and tended to have poor recovery and high levels of disability in follow-up.36 Although disability related to MOG-associated disorders is usually thought to be relapse-dependent, children with this disease phenotype may display progressive deterioration in addition to disability acquisition secondary to “typical” MOG-associated disorder relapses.80 Immunotherapy may help stabilize these cases.

Chronic Lymphocytic Inflammation With Pontine Perivascular Enhancement Responsive to Steroids

Chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids (CLIPPERS) is a rare syndrome that was first described in 2010.81 The diagnosis requires a clinical syndrome of subacute pontocerebellar dysfunction, without peripheral nerve involvement, that is responsive to steroids. On MRI, small, homogeneous gadolinium-enhancing nodules are visible in the pons and cerebellum with matching T2 lesions. Spinal cord lesions may also be seen. Gadolinium enhancement improves with steroids.82 Anti-MOG autoantibodies have been identified in several cases otherwise meeting clinical diagnostic criteria for CLIPPERS.83,84

DIAGNOSTIC WORKUP AND MONITORING FOR MYELIN OLIGODENDROCYTE GLYCOPROTEIN–ASSOCIATED DISEASE

Although clinical presentations can raise suspicion for MOG-associated disorders, diagnostic testing is essential to confirm the diagnosis. A thorough diagnostic workup will include CNS imaging along with CSF and blood testing.

Imaging in Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein–Associated Disorders

MRI remains one of the most clinically useful tools in evaluating acute autoimmune demyelinating syndromes, including MOG-associated disorders. Individuals with MOG-associated disorders exhibit a variety of distinctive radiologic characteristics that correspond to the clinical phenotype (TABLE 8–1, TABLE 8–2,85–90 and FIGURE 8–2). Screening MRI is less important for the long-term management of patients with MOG-associated disorders because individuals with MOG-associated disorders appear less likely to exhibit subclinical disease activity than those with MS.91 One pediatric study observed that some asymptomatic MRI lesions emerged within the first few months after a clinical event, but these silent lesions were not predictive of future relapsing disease (positive predictive value, 20%).92 Regular MRI screening of asymptomatic patients is, therefore, not typically indicated.

TABLE 8–1.

Clinical Characteristics of Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein-Associated Disorders According to Disease Phenotype

| MOG-associated disorder clinical characteristics | All MOG-associated disorders phenotypes | Acute optic neuritis | Acute myelitis | Acute ADEM | Non-ADEM encephalitis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average age of onset 10,17,61,69 | Early adulthood (late twenties to early thirties) | Early adulthood | Early to midadulthood | Pediatric to adolescence | Insufficient data |

| Overall proportion of cases 17 | N/A | Pediatric: 40–45% Adult: 55–60% |

Pediatric: 10–15% Adult: 25–30% |

Pediatric: 35–40% Adult: 5–10% |

Rare |

| MOG-antibody persistent | 43–86%19–21,61,69 | Very common (~98%)61 | Common (~44%)69 | Common (~68%)20 | Insufficient data |

| CSF cell counts 61,69,94,95 | Pleocytosis for most; marked pleocytosis for a subset: CSF white blood cell count >50/mm3 for ~20%, CSF white blood cell count >100/mm3 for ~10%; pleocytosis often resolves during remission | Normal or increased (median 2–3/ mm3); markedly elevated (≥100/mm3) in a subset (<5%; more common if comorbid with myelitis) | Elevated (median 41–45/mm3); markedly elevated (≥100/mm3) in a subset (~30%); lymphocytic predominance, neutrophils often detectable | Elevated (median 13–22/mm3); markedly elevated (≥100/mm3) in a subset (~5%); lymphocytic predominance, neutrophils often detectable | Elevated (median 13–22/mm3); markedly elevated (≥100/mm3) in a subset (~5%); lymphocytic predominance, neutrophils often detectable |

| Intrathecal IgG synthesis 61,69,94,95 | Oligoclonal bands present in <10% | Absent | Rare oligoclonal bands during relapses only | Rare oligoclonal bands during relapses only | Rare oligoclonal bands during relapses only |

| Unique MRI findings | N/A | Perineural enhancement (50%)61; long segment lesions (80%)61,64; chiasmal involvement (10–20%)61,64 | Short-segment lesions and longitudinally extensive lesions both common18,69; multiple spine lesions69; central gray involvement (H sign) and linear sagittal T2 hyperintensity (~30%)69; involvement of the conus (4–40%)69; enhancement/ edema mild or relatively uncommon (25–70%)18,69 | Diffuse, poorly demarcated, large (>1–2 cm), bilateral lesions involving subcortical/deep white matter and deep gray matter74 | Unilateral or bilateral cortical/subcortical lesions (~16%)16; isolated deep gray matter lesions; meningeal enhancement (<10%)16 |

ADEM = acute disseminated encephalomyelitis; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; IgG = immunoglobulin G; MOG = myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; N/A = not applicable.

TABLE 8–2.

Comparative Phenotypes of Common Central Nervous System Demyelinating Disorders

| Clinical feature | Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-associated disorder | Multiple sclerosis | Aquaporin-4-positive neuromyelitis optica |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, female:male | Around 1:110,16 | Around 2:185 | Up to 9:17 |

| Relapsing | +10,13–16 | +++ | +++86 |

| Comorbid autoimmune disease | +32 | +87 | ++32 |

| Clinical phenotype | |||

| Bilateral optic neuritis | ++ | + | ++ |

|

| |||

| Myelitis | ++ | + | ++ |

|

| |||

| Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) | ++ | (+) | − |

|

| |||

| Area postrema syndrome | − | − | ++ |

|

| |||

| MRI | |||

| McDonald criteria | (+) | +++ | (+) |

|

| |||

| Long-segment optic nerve | ++ | − | ++ |

|

| |||

| Optic chiasm | ++64 | − | ++64 |

|

| |||

| Perineural optic nerve enhancement | ++ | − | − |

|

| |||

| Longitudinally extensive spine | ++ | (+) | ++ |

|

| |||

| Gray matter spine | +++69 | − | + |

|

| |||

| Gadolinium enhancement | (+)69 | ++88 | ++ |

|

| |||

| CSF | |||

| Pleocytosis | +++ | (+) | + + |

|

| |||

| Oligoclonal bands | (+)94,95 | +++89 | −90 |

| Serologic biomarker | |||

| Anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein | +++ | − | − |

|

| |||

| Anti-aquaporin-4 | − | − | + + + |

|

| |||

| Approved treatments | − | +++ | + |

− = usually not present, not characteristic; (+) = rarely present, not characteristic; + = sometimes present; ++ = often present, or fairly characteristic; +++ = highly characteristic; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

KEY POINTS.

“Atypical” MOG-associated disorder presentations are still emerging, and this diagnosis should be considered when patients present with unusual central nervous system pathology.

MOG-associated disorders are rarely associated with subclinical radiologic activity, although emergence of asymptomatic MRI lesions has not been associated with future clinical relapses. Routine MRI screening of asymptomatic patients is typically unnecessary.

MOG autoantibodies should be tested in the serum. High titers are both sensitive and specific, but low titers may represent false positives. Clinical correlation is important.

MOG-associated disorders can be associated with a significant CSF lymphocytic pleocytosis in a subset of patients.

MOG autoantibodies have very rarely been associated with malignancies including lung adenocarcinoma,37 T-cell lymphoma,38 and teratoma.39 Screening for malignancy with CT or positron emission tomography (PET) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis or transvaginal ultrasound can be considered during the diagnostic workup and should be performed for patients for whom a high degree of clinical suspicion exists. The rarity with which MOG autoantibodies are paraneoplastic argues against routinely performing this imaging for patients without other risk factors.

Laboratory Findings in Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein–Associated Disorders

MOG-associated disorders are defined by the presence of anti-MOG antibodies. These antibodies should be detected in the serum by using cell-based assays. Importantly, although MOG antibody titers greater than 1:20 are considered positive, the positive predictive value of testing increases with higher antibody titers. Titers of 1:20 to 1:40 have a positive predictive value of 51% for diagnosing MOG-associated disorders, whereas titers of 1:1000 or higher have a positive predictive value of 100%. True positives were determined by consensus; two neurologists evaluated each case based on current international diagnostic recommendations or identification of alternative diagnoses.93 The overall positive predictive value for testing, with commercially available cell-based assay techniques, is 72%. It is, therefore, essential to consider the clinical picture when interpreting the results of MOG antibody testing. If the clinical picture is inconsistent with MOG-associated disorders, it is possible that a positive test result, particularly one with a low titer, could represent a false positive.

CSF findings in MOG-associated disorders usually support the diagnosis of an inflammatory CNS syndrome. Pleocytosis is common during relapses and is often much more marked than that seen with MS or AQP4-positive NMOSD: 10% to 15% of patients with MOG-associated disorders have a CSF cell count of 100/mm3 or higher (TABLE 8–1 and TABLE 8–2).94,95 Although lymphocytes are the predominant cell type, neutrophils are also detectable in around half of specimens. CSF pleocytosis associated with MOG-associated disorders tends to be most marked during relapses, and CSF cell counts are often higher during ADEM or myelitis episodes (as in the patient in CASE 8–2) as compared with isolated optic neuritis (TABLE 8–1). CSF protein may be modestly elevated during relapses, although oligoclonal banding is typically negative. If oligoclonal bands are detected, they are transient and disappear with the resolution of the clinical relapse. Blood-CSF barrier dysfunction, evidenced by an elevated albumin CSF-to-serum ratio, could also be detected in around half of patients tested, and this often persisted during remission.94,95 CSF profiles do not appear to vary substantially across the age spectrum.

TREATMENT OF MYELIN OLIGODENDROCYTE GLYCOPROTEIN–ASSOCIATED DISORDERS

Acute attacks of MOG-associated disorders are treated similarly to acute events in other demyelinating syndromes. High-dose IV corticosteroids (20 mg/kg/d to 30 mg/kg/d methylprednisolone for pediatric patients or 1000 mg/d methylprednisolone for adults) for 3 to 5 days are the first line of therapy, and most patients are steroid responsive. In one clinical cohort, IV steroids led to complete or near-complete recovery in 50% of patients, with another 44% exhibiting partial recovery.18 However, multiple lines of evidence support an increased risk of relapses in the months following an acute episode. In particular, relapses may be seen on withdrawal of steroids. The use of a slow oral steroid taper for up to 3 months after an exacerbation can help to mitigate this risk.96 Pediatric guidelines suggest starting an oral prednisone taper at 1 mg/kg/d to 2 mg/kg/d (maximum, 60 mg daily) and titrating down to 0.5 mg/kg/d over 1 to 4 weeks. Further prednisone tapering should occur more slowly, aiming to have the patient fully weaned by around 3 months after relapse. Close clinical monitoring is needed while weaning steroids.96 These guidelines may also be applied to adults.

KEY POINTS.

High-dose steroids, IVIg, and/or plasma exchange may be effective for treating MOG-associated disorder relapses. This may be followed by an oral steroid taper lasting up to 3 months because relapses often cluster temporally.

Steroid-sparing immunomodulators including azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, rituximab, and IVIg appear effective for treating relapsing MOG-associated disorders, but most patients continue to have some level of breakthrough disease.

A subset of patients does not respond to steroids, and for these individuals either plasma exchange or IVIg can be used as second-line therapy during a relapse. No strong data guide the selection of second-line treatment agent, and so the decision about plasma exchange versus IVIg should be made based on the clinical situation. Escalation should occur promptly (eg, after 3 to 5 days of high-dose steroids if the patient is not clinically improving) to avoid accumulation of disability because relapses may cluster temporally and high numbers of relapses tend to precipitate cumulative disability.91

Although no randomized clinical trials have been performed for MOG-associated disorders, cohort data strongly support the utility of steroid-sparing immunomodulators for those with relapsing disease. The most commonly used agents have been azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, rituximab, tocilizumab, and maintenance IVIg. Patients treated with any of these medications generally experienced reduction in their annualized relapse rates, supporting a beneficial role for immunomodulation, but a high proportion (20% to 75%) of treated patients continued to experience relapses regardless of the type of immunomodulator.96–98 Notably, anti-CD20 medications (eg, rituximab), which are highly efficacious in other demyelinating syndromes, appear to be relatively less efficacious for MOG-associated disorders. A high proportion of treated patients continued to have relapses, even when B cells were totally depleted.97,99

Although clinical data are limited, MS-specific immunomodulators appear to be ineffective for anti-MOG disorders.18,91 A retrospective observational case series of 70 patients with MOG-associated disorders receiving long-term immunotherapy through the Mayo Clinic included nine patients treated with traditional MS medications, including interferons, glatiramer acetate, and fingolimod. The posttreatment annualized relapse rate was unchanged compared with the pretreatment relapse rate, and all nine patients experienced relapses during treatment.97 Recent in vitro work also suggested that fingolimod had the potential to compound the blood-brain barrier dysfunction induced by anti-MOG antibodies.55 Traditional MS disease-modifying therapies should, therefore, be avoided in patients with MOG-associated disorders.

Controversy remains about when to start patients with MOG-associated disorders on long-term immunotherapy. As discussed, current natural history data support that a substantial subset of patients has monophasic disease, and committing these individuals to lifelong immunosuppression introduces unnecessary risks. A recent consensus statement from the European Union pediatric MOG consortium suggested initiating maintenance immunotherapy at the time of the second event (ie, first relapse).96 If subsequent relapses occur while on immunotherapy, an alternative agent should be considered. If relapses continue despite adequate treatment with at least two different immunomodulators, add-on therapy may be used; for example, oral prednisone or pulse IVIg could be added onto rituximab.96 These principles may also be applied for adults. In general, unless a patient had a very poor recovery from the incident event, maintenance therapy would not be started until it was clear that the patient had a relapsing, and not a monophasic, variant of a MOG-associated disorder. Better data elucidating the risk factors for relapsing disease are needed to ensure that those needing maintenance immunotherapy receive it in a timely fashion. At this point, older age appears to be the strongest risk factor for relapse.17,19 Other putative risk factors, including whether the incident MOG-associated disorder episode arises in a postinfectious setting and whether serial antibody titers can be used for overall risk stratification, require more study.17,19–21

CLINICAL OUTCOMES FOR MYELIN OLIGODENDROCYTE GLYCOPROTEIN–ASSOCIATED DISORDERS

Clinical outcomes for MOG-associated disorders are determined in large part by the clinical phenotype and by the number of relapses experienced. One large-scale study including 252 children and adults with MOG-associated disorders reported that 78% had “good” or full recovery from their initial episode.10 Younger age was positively associated with better recovery, whereas disability tended to be greater among patients who had experienced higher numbers of attacks and among those who did not fully recover from their onset attack.91 Age at onset, sex, ethnicity, and disease duration were not significant contributors to long-term disability.10

Radiologic lesions associated with MOG-associated disorders frequently resolve, regardless of the clinical phenotype,10,16 although a few notable exceptions exist. A small minority of patients presenting with MOG-associated ADEM exhibited progressive accumulation of white matter changes suggestive of a leukodystrophy.36 Another small subset of patients, mainly those presenting with atypical encephalitis, subsequently developed cortical atrophy. Both of these radiographic findings were associated with poor long-term clinical outcomes.36

KEY POINTS.

Most patients with MOG-associated disorders recover well from the incident attack, but significant disability may accumulate with subsequent relapses.

MOG-associated myelitis is the clinical phenotype most strongly associated with permanent disability.

To date, no serologic or CSF studies have been predictive of either future disease course or long-term outcomes. Although some studies associated persistent high titers of anti-MOG antibodies with relapsing disease,100,101 others observed relapses even in patients who converted to seronegative, so the prognostic value of seroconversion to MOG negative remains uncertain. Moreover, patients seroconverting to MOG-antibody negative after their initial episode may test positive again in the setting of a new relapse.19

Optic Neuritis

MOG-associated optic neuritis often results in good visual recovery after an incident event, particularly for children, although the associated retinal axon loss can be severe.17,18,68,102 Recurrent optic neuritis is common for MOG-associated disorders, and some studies found the relapse rate to be higher with MOG-associated optic neuritis than with AQP4-positive NMOSD.61,103 Visual disability may accumulate with subsequent episodes.104 Long-term follow-up data for one cohort of 61 patients with MOG-associated disorders found that 16% had unilateral blindness and 6% had bilateral blindness at a median follow-up of almost 15 years14; another cohort observed functional blindness or severe visual impairment (visual acuity ≤0.1 and ≤0.5, respectively) in at least one eye for 14 of 38 patients around 4 years after their initial optic neuritis presentation.18 Interestingly, emerging data suggest that subclinical damage to retinal axons may occur in MOG-associated disorders. In a small cohort, the unaffected eyes from patients with MOG-associated unilateral optic neuritis had lower retinal nerve fiber layer thickness than unaffected eyes from patients with either AQP4-positive or AQP4-negative optic neuritis.105 Additional work is needed to determine whether this subclinical involvement occurs during or independent of clinical relapses.

Myelitis

Among all MOG-associated disorder phenotypes, myelitis is the most likely to cause permanent disability. At clinical nadir, one study of 54 patients with MOG-associated myelitis estimated that 75% were unable to ambulate independently and one-third needed wheelchairs. This improved with time, and after 2 years only 6% continued to require ambulatory assistance, although nearly half continued to experience bowel, bladder, and/or sexual dysfunction.69 Another study reported complete recovery in only about one-third of myelitis cases.18 Adults presenting with MOG-associated myelitis were more likely to experience residual disability and future relapses when compared with pediatric patients.17

Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis

Patients with MOG-associated disorders presenting with ADEM may follow either a monophasic or a relapsing clinical course, and MOG autoantibodies may be either persistent or transient. The child described in CASE 8–3 followed a typical clinical course of rapid deterioration followed by full clinical and radiologic recovery. Her seroconversion to antibody negative suggests that she may avoid future relapses; patients with ADEM who seroconverted to MOG antibody–negative had fewer subsequent relapses in one small observational cohort (12% compared with 88%).20 However, relapses could occur regardless of serostatus.20 Compared with children, adults presenting with ADEM were at higher risk of both relapses and incomplete recovery.17

CASE 8–3

An 8-year-old girl developed fever and confusion. After 3 days, she had a generalized seizure and was admitted to the hospital. Brain MRI showed extensive, bilateral diffuse T2 hyperintensities in the supratentorial white matter and deep gray nuclei with associated patchy contrast enhancement. CSF revealed a lymphocytic pleocytosis with a white blood cell count of 50/mm3 and protein of 45 mg/dL; CSF cultures and viral polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) were negative. Autoimmune encephalitis antibody panels and antithyroid autoantibodies were negative, but serum anti–myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) autoantibodies were positive with a titer of 1:1000.

The patient was treated with high-dose steroids and IVIg. Her mental status slowly improved over the course of 2 months, and she was eventually discharged to home. Her follow-up brain MRI at 6 months was normal, and anti-MOG autoantibody testing was negative. She was not started on maintenance immunotherapy.

COMMENT

This child presented with a clinical picture consistent with acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM). A broad clinical workup, evaluating both infectious and immune-mediated causes of her symptoms was appropriately performed because no clinical clues strongly suggested any inciting etiology. When high-titer anti-MOG antibodies were identified, she was reclassified as having a MOG-associated disorder. As is often seen in young children with anti-MOG–associated ADEM, she ultimately had complete resolution of both clinical and MRI findings without further relapses. Some children with this clinical picture do subsequently experience academic difficulties, so continued vigilance is appropriate.

Although many cases of ADEM appear to resolve completely, residual cognitive deficits can often be detected. Academic difficulties were observed in 72% of children with past MOG-associated ADEM in one cohort106; other studies found residual cognitive deficits in 10% to 50% of pediatric patients with MOG-associated disorders.102 Children with long-term cognitive problems were often younger (10 years old or younger) and had deep gray matter lesions at disease onset.106

Focal and Atypical Encephalitis

Focal encephalitis syndromes associated with MOG autoantibodies are often steroid responsive or self-limited with a corresponding resolution of MRI lesions.75–78 In contrast, patients with MOG-associated disorders with atypical, non-ADEM encephalitis are at high risk for poor outcomes. In one prospective observational study, 8 of 42 individuals (36%) presenting with this clinical phenotype had a modified Rankin score of 2 or higher in long-term follow-up.36 Patients whose MRI scans progressed to show a leukodystrophylike pattern or cortical atrophy also did worse clinically. Indeed, the latter group of patients exhibited progressive clinical deterioration independent of relapses and development of permanent cognitive/neurologic deficits.36 Refractory epilepsy was also seen among this subset of patients.102

CONCLUSION

MOG-associated disorders represent a pathophysiologically distinct class of antibody-mediated CNS demyelinating disorders. As these antibodies were recognized as pathogenic only within the past decade, the full spectrum of disease is still emerging. Although rare phenotypic variants may continue to emerge, the most common clinical presentations have now been established as optic neuritis, myelitis, and ADEM, occurring alone, sequentially, or in combination. Both children and adults are affected by MOG-associated disorders, with ADEM being more likely in the youngest patients and myelitis in older individuals. Unlike many other CNS demyelinating diseases, a subset of MOG-associated disorders is monophasic, and ongoing work is necessary to accurately identify which patients will have recurrent relapses and benefit from maintenance immunotherapy. Although the observational literature suggests that immunotherapy may be effective for many, no published randomized controlled clinical trials demonstrate efficacy for any pharmacotherapy, much less elucidate relative efficacies for different classes of immune pharmacotherapies. Much work remains to be done, and the emerging large-scale data describing the clinical spectrum and natural history of MOG-associated disorders will be foundational for future therapeutic trials.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The author would like to thank Drs Amanda Hernandez and Naila Makhani for their critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

(Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs). The institution of Dr Longbrake has received research support from Genentech, Inc, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (K23107624 and UL1 TR001863), Race to Erase MS, and the and Robert E. Leet and Clara Guthrie Patterson Trust.

RELATIONSHIP DISCLOSURE:

Dr Longbrake has served on the editorial board for Neurology: Neuroimmunology and Neuroinflammation and the Journal of Neuroimmunology and has received personal compensation in the range of $0 to $499 for serving as the scientific advisory board chair and as a steering committee member for Genentech, Inc, and in the range of $500 to $4999 for serving as an advisory board member for Genentech, Inc, Janssen Global Services, LLC, and TG Therapeutics, Inc; for serving as an assistant associate editor for Annals of Neurology; and for serving as a study section member with the Department of Defense Continued on page 1193

UNLABELED USE OF PRODUCTS/INVESTIGATIONAL USE DISCLOSURE:

Dr Longbrake discusses the unlabeled/investigational use of immunomodulators, none of which is approved for the treatment of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein–associated disorders.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gaertner S, Graaf KL, Greve B, Weissert R. Antibodies against glycosylated native MOG are elevated in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2004;63(12):2381–2383. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000147259.34163.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karni A, Bakimer-Kleiner R, Abramsky O, Ben-Nun A. Elevated levels of antibody to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein is not specific for patients with multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol 1999;56(3):311–315. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lampasona V, Franciotta D, Furlan R, et al. Similar low frequency of anti-MOG IgG and IgM in MS patients and healthy subjects. Neurology 2004;62(11):2092–2094. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000127615.15768.ae [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Connor KC, McLaughlin KA, De Jager PL, et al. Self-antigen tetramers discriminate between myelin autoantibodies to native or denatured protein. Nat Med 2007;13(2):211–217. doi: 10.1038/nm1488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waters PJ, Komorowski L, Woodhall M, et al. A multicenter comparison of MOG-IgG cell-based assays. Neurology 2019;92(11):e1250–e1255. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waters P, Woodhall M, O’Connor KC, et al. MOG cell-based assay detects non-MS patients with inflammatory neurologic disease. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2015;2(3):e89. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hor JY, Asgari N, Nakashima I, et al. Epidemiology of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder and its prevalence and incidence worldwide. Front Neurol 2020;11:501. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Mol C, Wong Y, Pelt E, et al. The clinical spectrum and incidence of anti-MOG-associated acquired demyelinating syndromes in children and adults. Mult Scler 2020;26(7):806–814. doi: 10.1177/1352458519845112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brill L, Ganelin-Cohen E, Dabby R, et al. Age-related clinical presentation of MOG-IgG seropositivity in Israel. Front Neurol 2020;11:612304. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.612304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jurynczyk M, Messina S, Woodhall MR, et al. Clinical presentation and prognosis in MOG-antibody disease: a UK study. Brain 2017;140(12):3128–3138. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ciotti JR, Eby NS, Wu GF, et al. Clinical and laboratory features distinguishing MOG antibody disease from multiple sclerosis and AQP4 antibody-positive neuromyelitis optica. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2020;45:102399. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grant-Peters M, Dos Passos GR, Yeung HY, et al. No strong HLA association with MOG antibody disease in the UK population. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2021;8(7):1502–1507. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boesen MS, Jensen PEH, Born AP, et al. Incidence of pediatric neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease in Denmark 2008–2018: a nationwide, population-based cohort study. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2019;33:162–167. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2019.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deschamps R, Pique J, Ayrignac X, et al. The long-term outcome of MOGAD: an observational national cohort study of 61 patients. Eur J Neurol 2021;28(5):1659–1664. doi: 10.1111/ene.14746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu J, Mori M, Zimmermann H, et al. Anti-MOG antibody–associated disorders: differences in clinical profiles and prognosis in Japan and Germany. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2021;92:377–383. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2020-324422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cobo-Calvo A, Ruiz A, Maillart E, et al. Clinical spectrum and prognostic value of CNS MOG autoimmunity in adults: the MOGADOR study. Neurology 2018;90(21):e1858–e1869. doi:doi:1212/WNL.0000000000005560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cobo-Calvo A, Ruiz A, Rollot F, et al. Clinical features and risk of relapse in children and adults with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease. Ann Neurol 2021;89(1):30–41. doi: 10.1002/ana.25909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jarius S, Ruprecht K, Kleiter I, et al. MOG-IgG in NMO and related disorders: a multicenter study of 50 patients. Part 1: frequency, syndrome specificity, influence of disease activity, long-term course, association with AQP4-IgG, and origin. J Neuroinflammation 2016;13(1):279. doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0717-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waters P, Fadda G, Woodhall M, et al. Serial anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody analyses and outcomes in children with demyelinating syndromes. JAMA Neurol 2020;77(1):82–93. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lopez-Chiriboga AS, Majed M, Fryer J, et al. Association of MOG-IgG serostatus with relapse after acute disseminated encephalomyelitis and proposed diagnostic criteria for MOG-IgG-associated disorders. JAMA Neurol 2018;75(11):1355–1363. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.1814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hyun JW, Woodhall MR, Kim SH, et al. Longitudinal analysis of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies in CNS inflammatory diseases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2017;88(10):811–817. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-315998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amano H, Miyamoto N, Shimura H, et al. Influenza-associated MOG antibody-positive longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis: a case report. BMC Neurol 2014;14:224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakamura Y, Nakajima H, Tani H, et al. Anti-MOG antibody-positive ADEM following infectious mononucleosis due to a primary EBV infection: a case report. BMC Neurol 2017;17:76. doi: 10.1186/s12883-014-0224-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakamura M, Iwasaki Y, Takahashi T, et al. A case of MOG antibody-positive bilateral optic neuritis and meningoganglionitis following a genital herpes simplex virus infection. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2017;17:148–150. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2017.07.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peters J, Alhasan S, Vogels CBF, et al. MOG-associated encephalitis following SARS-COV-2 infection. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2021;50:102857. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2017.07.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jumah M, Rahman F, Figgie M, et al. COVID-19, HHV6 and MOG antibody: a perfect storm. J Neuroimmunol 2021;353:577521. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2021.577521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vieira JP, Sequeira J, Brito MJ, et al. Postinfectious anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody positive optic neuritis and myelitis. J Child Neurol 2017;32(12):996–999. doi: 10.1177/0883073817724927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi SJ, Oh DA, Chun W, Kim SM. The relationship between anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease and the Rubella virus. J Clin Neurol 2018;14(4):598–600. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2018.14.4.598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neri VC, Xavier MF, Barros PO, et al. Case report: acute transverse myelitis after Zika virus infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2018;99(6):1419–1421. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonagiri P, Park D, Ingebritsen J, Christie LJ. Seropositive anti-MOG antibody-associated acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM): a sequelae of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. BMJ Case Rep 2020;13:5. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-234565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Netravathi M, Dhamija K, Gupta M, et al. COVID-19 vaccine associated demyelination and its association with MOG antibody. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2022;60:103739. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2022.103739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kunchok A, Flanagan EP, Snyder M, et al. Coexisting systemic and organ-specific autoimmunity in MOG-IgG1-associated disorders versus AQP4-IgG+ NMOSD. Mult Scler 2021;27(4):630–635. doi: 10.1177/1352458520933884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sato DK, Callegaro D, Lana-Peixoto MA, et al. Distinction between MOG antibody-positive and AQP4 antibody-positive NMO spectrum disorders. Neurology 2014;82(6):474–481. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kunchok A, Flanagan EP, Krecke KN, et al. MOG-IgG1 and co-existence of neuronal autoantibodies. Mult Scler 2021;27(8):1175–1186. doi: 10.1177/1352458520951046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ding J, Ren K, Wu J, et al. Overlapping syndrome of MOG-IgG-associated disease and autoimmune GFAP astrocytopathy. J Neurol 2020;267(9):2589–2593. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09869-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Armangue T, Olive-Cirera G, Martinez-Hernandez E, et al. Associations of paediatric demyelinating and encephalitic syndromes with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies: a multicentre observational study. Lancet Neurol 2020;19(3):234–246. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30488-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li K, Zhan Y, Shen X, et al. Multiple intracranial lesions with lung adenocarcinoma: a rare case of MOG-IgG-associated encephalomyelitis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2020;42:102064. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kwon YN, Koh J, Jeon YK, et al. A case of MOG encephalomyelitis with T-cell lymphoma. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2020;41:102038. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wildemann B, Jarius S, Franz J, et al. MOG-expressing teratoma followed by MOG-IgG-positive optic neuritis. Acta Neuropathol 2021;141(1):127–131. doi: 10.1007/s00401-020-02236-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Collongues N, Do Rego CA, Bourre B, et al. Pregnancy in patients with AQP4-Ab, MOG-Ab, or double-negative neuromyelitis optica disorder. Neurology 2021;96(15):e2006–e2015. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000011744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lucchinetti C, Bruck W, Parisi J, et al. Heterogeneity of multiple sclerosis lesions: implications for the pathogenesis of demyelination. Ann Neurol 2000;47(6):707–717. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(200006)47:6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoftberger R, Guo Y, Flanagan EP, et al. The pathology of central nervous system inflammatory demyelinating disease accompanying myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein autoantibody. Acta Neuropathol 2020;139(5):875–892. doi: 10.1007/s00401-020-02132-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Di Pauli F, Berger T. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disorders: toward a new spectrum of inflammatory demyelinating CNS disorders? Front Immunol 2018;9:2753. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takai Y, Misu T, Kaneko K, et al. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease: an immunopathological study. Brain 2020;143(5):1431–1446. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Popescu BF, Guo Y, Jentoft ME, et al. Diagnostic utility of aquaporin-4 in the analysis of active demyelinating lesions. Neurology 2015;84(2):148–158. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Popescu BF, Parisi JE, Cabrera-Gomez JA, et al. Absence of cortical demyelination in neuromyelitis optica. Neurology 2010;75(23):2103–2109. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d80c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.von Budingen H, Hauser S, Ouallet J, et al. Frontline: epitope recognition on the myelin/oligodendrocyte glycoprotein differentially influences disease phenotype and antibody effector functions in autoimmune demyelination. Eur J Immunol 2004;34(8):2072–2083. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Graaf K, Albert M, Weissert R, et al. Autoantigen conformation influences both B- and T-cell responses and encephalitogenicity. J Biol Chem 2012;287(21):17206–17213. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.304246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tea F, Lopez JA, Ramanathan S, et al. Characterization of the human myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody response in demyelination. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2019;7:145. doi: 10.1186/s40478-019-0786-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jarius S, Ruprecht K, Kleiter I, et al. MOG-IgG in NMO and related disorders: a multicenter study of 50 patients. Part 2: epidemiology, clinical presentation, radiological and laboratory features, treatment responses, and long-term outcome. J Neuroinflammation 2016;13(1):280. doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0718-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mader S, Gredler V, Schanda K, et al. Complement activating antibodies to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein in neuromyelitis optica and related disorders. J Neuroinflammation 2011;8:184. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou D, Srivastava R, Nessler S, et al. Identification of a pathogenic antibody response to native myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein in multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103(50):19057–19062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607242103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spadaro M, Winklmeier S, Beltran E, et al. Pathogenicity of human antibodies against myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein. Ann Neurol 2018;84(2):315–328. doi: 10.1002/ana.25291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dale RC, Tantsis EM, Merheb V, et al. Antibodies to MOG have a demyelination phenotype and affect oligodendrocyte cytoskeleton. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2014;1:1. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoshimura S, Nakagawa S, Takahashi T, et al. FTY720 exacerbates blood-brain barrier dysfunction induced by IgG derived from patients with NMO and MOG disease. Neurotox Res 2021;39(4):1300–1309. doi: 10.1007/s12640-021-00373-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kwon YN, Kim B, Ahn S, et al. Serum level of IL-1β in patients with inflammatory demyelinating disease: marked upregulation in the early acute phase of MOG antibody associated disease (MOGAD). J Neuroimmunol 2020;348:577361. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2020.577361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saxena S, Lokhande H, Gombolay G, et al. Identification of TNFAIP3 as relapse biomarker and potential therapeutic target for MOG antibody associated diseases. Sci Rep 2020;10(1):12405. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-69182-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu J, Mori M, Sugimoto K, et al. Peripheral blood helper T cell profiles and their clinical relevance in MOG-IgG-associated and AQP4-IgG-associated disorders and MS. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2020;91(2):132–139. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2019-321988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kothur K, Wienholt L, Tantsis EM, et al. B cell, Th17, and neutrophil related cerebrospinal fluid cytokine/chemokines are elevated in MOG antibody associated demyelination. PLoS One 2016;11(2):e0149411. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wingerchuk DM, Banwell B, Bennett JL, et al. International consensus diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Neurology 2015;85(2):177–189. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen JJ, Flanagan EP, Jitprapaikulsan J, et al. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-positive optic neuritis: clinical characteristics, radiologic clues, and outcome. Am J Ophthalmol 2018;195:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2018.07.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Padungkiatsagul T, Chen JJ, Jindahra P, et al. Differences in clinical features of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated optic neuritis in white and Asian race. Am J Ophthalmol 2020;219:332–340. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2020.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen JJ, Tobin WO, Majed M, et al. Prevalence of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein and aquaporin-4-IgG in patients in the optic neuritis treatment trial. JAMA Ophthalmol 2018;136(4):419–422. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.6757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tajfirouz D, Padungkiatsagul T, Beres S, et al. Optic chiasm involvement in AQP-4 antibody-positive NMO and MOG antibody-associated disorder. Mult Scler 2021;28(1):149–153. doi: 10.1177/13524585211011450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tajfirouz DA, Bhatti MT, Chen JJ, et al. Clinical characteristics and treatment of MOG-IgG-associated optic neuritis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2019;19(12):100. doi: 10.1007/s11910-019-1014-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Asseyer S, Hamblin J, Messina S, et al. Prodromal headache in MOG-antibody positive optic neuritis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2020;40:101965. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.101965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Filippatou AG, Mukharesh L, Saidha S, et al. AQP4-IgG and MOG-IgG related optic neuritis-prevalence, optical coherence tomography findings, and visual outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurol 2020;11:540156. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.540156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Havla J, Pakeerathan T, Schwake C, et al. Age-dependent favorable visual recovery despite significant retinal atrophy in pediatric MOGAD: how much retina do you really need to see well? J Neuroinflammation 2021;18(1):121. doi: 10.1186/s12974-021-02160-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dubey D, Pittock SJ, Krecke KN, et al. Clinical, radiologic, and prognostic features of myelitis associated with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein autoantibody. JAMA Neurol 2019;76(3):301–309. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wingerchuk DM, Banwell B, Bennett JL, et al. International consensus diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Neurology 2015;85(2):177–189. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kitley J, Woodhall M, Waters P, et al. Myelin-oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies in adults with a neuromyelitis optica phenotype. Neurology 2012;79(12):1273–1277. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826aac4e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hamid SHM, Whittam D, Mutch K, et al. What proportion of AQP4-IgG-negative NMO spectrum disorder patients are MOG-IgG positive? A cross sectional study of 132 patients. J Neurol 2017;264(10):2088–2094. doi: 10.1007/s00415-017-8596-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]