Abstract

Background

There is growing evidence that chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) can increase the risk of lung cancer, which poses a serious threat to treatment and management. Therefore, we performed a meta-analysis of lung cancer prevalence in patients with COPD with the aim of providing better prevention and management strategies.

Methods

We systematically searched PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library databases from their inception to 20 March 2022 to collect studies on the prevalence of lung cancer in patients with COPD. We evaluated the methodological quality of the included studies using the tool for assessing the risk of bias in prevalence studies. Meta-analysis was used to determine the prevalence and risk factors for lung cancer in COPD. Subgroup and sensitivity analyses were conducted to explore the data heterogeneity. Funnel plots combined with Egger’s test were used to detect the publication biases.

Results

Thirty-one studies, covering 829,490 individuals, were included to investigate the prevalence of lung cancer in patients with COPD. Pooled analysis demonstrated that the prevalence of lung cancer in patients with COPD was 5.08% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 4.17–6.00%). Subgroup analysis showed that the prevalence was 5.09% (95% CI: 3.48–6.70%) in male and 2.52% (95% CI: 1.57–4.05%) in female. The prevalence of lung cancer in patients with COPD who were current and former smokers was as high as 8.98% (95% CI: 4.61–13.35%) and 3.42% (95% CI: 1.51–5.32%); the incidence rates in patients with moderate and severe COPD were 6.67% (95% CI: 3.20–10.14%) and 5.57% (95% CI: 1.89–16.39%), respectively, which were higher than the 3.89% (95% CI: 2.14–7.06%) estimated in patients with mild COPD. Among the types of lung cancer, adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma were the most common, with incidence rates of 1.59% (95% CI: 0.23–2.94%) and 1.35% (95% CI: 0.57–3.23%), respectively. There were also differences in regional distribution, with the highest prevalence in the Western Pacific region at 7.78% (95% CI: 5.06–10.5%), followed by the Americas at 3.25% (95% CI: 0.88–5.61%) and Europe at 3.21% (95% CI: 2.36–4.06%).

Conclusions

This meta-analysis shows that patients with COPD have a higher risk of developing lung cancer than those without COPD. More attention should be given to this result in order to reduce the risk of lung cancer in these patients with appropriate management and prevention.

Systematic review registration

International prospective register of systematic reviews, identifier CRD42022331872.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung cancer, prevalence, meta-analysis, systematic review

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common respiratory disease characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow restriction, with a high risk of morbidity, disability rate, mortality, and heavy disease burden, which seriously impacts human health (1, 2). The prevalence of COPD has increased by 44.2% and reached 174.5 million individuals worldwide from 1990 to 2015 (3), although it remains so far underestimated (4). More than 5.4 million people will die from COPD and related diseases each year by 2060, according to predictions made by the World Health Organization (WHO) (5). As the third leading cause of death worldwide (6, 7), COPD has caused serious economic burden and social pressure and has become a major public health problem (8, 9). The cost of treating COPD is expected to be $800.09 billion in the next 20 years, which is approximately $40 billion per year in the United States (10). Patients with COPD are at a high risk of multiple comorbidities, which have a significant impact on disease progression, hospitalization, and mortality (11–13). As reported by the National Lung Screening Trial, the incidence of lung cancer in patients with airway obstruction has increased by 2.15 times (14), and lung cancer is a critical cause of hospitalization and death in patients with COPD (15). Therefore, it is necessary to emphasize the importance of prevention and treatment of lung cancer in patients with COPD.

Lung cancer is one of the malignant tumors with the highest morbidity and mortality worldwide, especially in male patients, and has a devastating impact on the life expectancy (16). The number of individuals newly diagnosed with lung cancer was up to 2.2 million (11.4%) as reported by Global Cancer Statistics in 2020, and the number of patients with lung cancer that died in the world that year was approximately 1.8 million (18.0%) (16). The onset of lung cancer is insidious, and 75% of patients have reached an advanced stage when visiting a doctor (17). Related studies have shown that the 5-year survival rate of patients with advanced lung cancer is less than 5% (18). Importantly, it has been reported that 45–63% of patients with lung cancer are globally affected by COPD (19). As two major respiratory diseases with the highest mortality, patients with COPD seem to have a higher incidence of lung cancer than patients without COPD (20, 21).

Although previous studies have found that COPD increases the risk of lung cancer, no unified conclusions have been reached owning to the differences in survey periods, sample demographic characteristics, and types of included studies. Currently, there is still no specific epidemiological conclusion concerning an evaluation of the risk of lung cancer in patients with COPD, according to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines. In addition, several high-quality observational studies (22–29) investigating the risk of lung cancer in patients with COPD have recently been published. Therefore, we systematically collected data from existing observational population-based studies to determine whether patients with COPD have an increased risk of lung cancer.

Methods

This study was performed in strict accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) (30). The protocol of this systematic review was registered in the Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), and the registry number is CRD42022331872.

Search strategy

We systematically searched the PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library databases without language restrictions from their inception to 20 March 2022. Medical Subject Headings (MESH) terms and keywords used in the search were (“Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive” OR “Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease*” OR “Chronic Airflow Obstruction*” OR “Chronic Obstructive lung Disease” OR “COPD” OR “COAD” OR “Chronic Obstructive Airway Disease”) AND (“lung neoplasm*” OR “pulmonary neoplasm*” OR “lung cancer” OR “pulmonary cancer” OR “lung tumor” OR “pulmonary tumor” OR “lung carcinoma”). Detailed retrieval strategies and steps are presented in Supplement Table 1 . Furthermore, the reference lists of the retrieved articles and relevant reviews were also manually examined to identify other potentially eligible studies.

Eligibility criteria

Articles were included if they met the following criteria: (1) observational studies that reported on the prevalence of lung cancer in patients with COPD; (2) the exposed group consisted of patients with any grade of COPD, and the control group consisted of patients without COPD; (3) the prevalence of lung cancer was chosen as the primary outcome.

Exclusion criteria

(1) Conference abstracts or study protocols; (2) duplicate published studies based on the same observation population; and (3) containing data with errors and patients diagnosed with non-COPD upon our failure to extract information.

Study selection

The study selection was conducted independently by two reviewers (GX Zhao and XL Li) to screen suitable articles. Duplicate and irrelevant studies were excluded based on their titles and abstracts. Thereafter, the full text of each potentially eligible study was carefully read and reviewed based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria stated above. Any disagreements were resolved by consultation with a third investigator (JS Li) until consensus was reached.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (GX Zhao and SY Lei) independently followed the data extraction guidelines for systematic evaluation and meta-analysis (31), using predesigned forms to extract and summarize the relevant information of the eligible studies. The following information was extracted: Author, year of publication, study type, country, study period or year of follow-up, sample size, lung cancer diagnosis, sex distribution, mean or median age, COPD severity, smoking status, lung cancer type, and confounder adjustment. Any disagreements were resolved with a third investigator (HL Zhang) through consultation until a consensus was reached.

Assessment of risk of bias

We used the disease prevalence quality tool modified by Hoy et al. (32) to assess the quality of the included studies, which consisted of 10 items. The score of each item was 1 or 0, and the total scores of each observational study was between 0 and 10, with higher scores indicating better study quality. Study quality was defined according to the total score of each study, with scores of 0–5, 6–8, and 9–10 for low, moderate, and high quality, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Data were extracted from the included studies to calculate the prevalence of lung cancer in patients with COPD. We performed a meta-analysis using the double arcsine transformation of proportions, which is appropriate for binomial data and allows the adoption of inverse variance methods to calculate binomial and test score-based CIs (33). The chi-square test and I 2 value were used to assess the heterogeneity. A high heterogeneity was existed if P < 0.1 or I 2 > 50%, and the random-effects model was adopted. Subgroup analysis was conducted to determine whether the prevalence was influenced by sex, smoking status, COPD severity, cancer type, and region. Otherwise, a fixed-effects model was selected. To confirm the robustness of the overall results, we performed a sensitivity analysis by excluding one study each time and then re-running it. Funnel plots was used to visually detect publication bias, and Egger’s regression test was used to statistically inspect publication bias. We pooled OR and 95% CIs to assess whether sex, COPD severity, and smoking status were risk factors for lung cancer in patients with COPD. All statistical analyses were conducted by using Stata statistical software version 15.1.

Results

Identification of studies

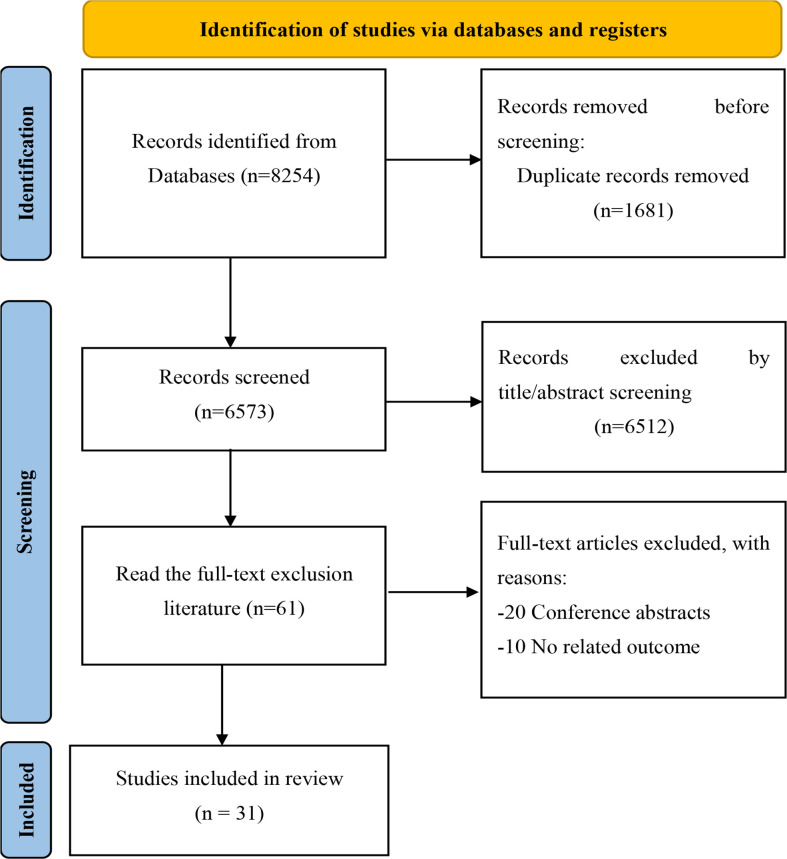

A total of 8,254 related studies were retrieved through electronic and manual searching from the initial examination, of which 1,681 duplicates, 6,573 unrelated studies were excluded after reading titles and abstracts. After screening qualified articles by reading the full text, 31 (13, 22–26, 34–55) studies were included in the meta-analysis. The study selection process is shown in ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study identification for meta-analysis.

Study characteristics

Overall, we included 31studies covering 829,490 patients with COPD, including twenty-one (13, 22–26, 34–48) cohort studies, three (27, 49, 50) case-control studies and seven (28, 29, 51–55) cross-sectional studies. These studies were published from 2003 to 2022 with definite diagnostic criteria, and the sample sizes ranged from 198 to 236,494. Data were acquired from 13 countries: China, Korea, Japan, the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, Denmark, Norway, Spain, Lithuania, Sweden, Turkey, and the Netherlands. Fifteen, twelve, and two studies were conducted in the European region, Western Pacific region, and Americas, respectively. Besides, two studies (13, 41) included both the United States and Spain, simultaneously. The main characteristics of the included trials are summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the included studies.

| Reference | Country | Study design | COPD | Lung cancer | Duration or range of follow-up, years | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Sample size | Age (years) | M/F | Diagnosis | Sample size | M/F | ||||

| Sandelin et al.2018 (22) | Swedish | Retrospective cohort | ICD-10-CM code J44 | 19894 | – | 9452/110442 | ICD-10 code C34 | 594 | 291/303 | 1999.1.1-2009.12.31 |

| Ahn et al., 2020 (23) | Korean | Retrospective cohort | ICD-10 codes J43-J44 | 11551 | – | 6172/5379 | ICD-10 codes C33-C34 | 1136 | – | 2004.1.1-2015.12.31 |

| Husebøet al., 2019 (24) | Norway | Prospective cohort | Clinical and Spirometry confirmed | 433 | 63.5 ± 6.9 | 258/175 | Norwegian Cancer Registry | 28 | – | 9 |

| Park et al., 2020 (25) | Korean | Retrospective cohort | ICD-10 codes J43-J44 | 58972 | – | – | ICD-10 code C33 or C34 | 290 | – | 2002.1.1-2013.12.31 |

| Machida et al., 2021 (26) | Japan | Prospective cohort | Spirometry confirmed | 224 | 70.4 ± 8.4 | 214/10 | CT | 19 | 19 | 2014.1-2020.4 |

| Sakai et al., 2020 (27) | Japan | Retrospective cohort | Spirometry confirmed | 198 | 69.7 ± 8.0 | 184/14 | – | 43 | – | 2011.4.1-2015.7.16 |

| Montserrat et al., 2021 (28) | Spain | Retrospective cross-sectional | Spirometry confirmed | 24135 | 72 ± 11 | 18612/5523 | ICD-10 | 552 | – | 2012.1.1-2017.12.31 |

| Jurevičienė et al., 2022 (29) | Lithuanian | Retrospective cross-sectional | ICD-10-AMD J44.8 | 4834 | 67.2 ± 8.4 | 3338/1496 | ICD 10 code C33, C34 | 186 | – | 2012.1.1-2014.6.30 |

| Thomsen et al., 2012 (34) | Denmark | Prospective cohort | ICD8: 490–492; ICD10: J44 | 8656 | 65 (57, 74) | 47%/53% | ICD10 code C34 | 93 | – | 5 |

| Chubachi et al., 2016 (35) | Japan | Prospective cohort | Spirometry confirmed | 311 | 72.3 ± 8.2 | 278/33 | clinical history and medical records | 13 | – | 2 |

| Divo et al., 2012 (13) | USA + Spain | Prospective cohort | Spirometry confirmed | 1659 | 66 ± 9 | 1477/182 | medical record and direct questioning | 151 | – | 1997.11-2010.3 |

| Westerik et al., 2017 (36) | Dutch | Retrospective cohort | ICPC code R95 in the electronic medical record | 14603 | 66.5 ± 11.5 | 7749/6854 | ICPC code R84 | 317 | – | 2012–2013.12.31 |

| Lin et al.2013 (37) | China | Retrospective case-control | ICD-9-CM code 496 | 2630 | – | 2096/534 | cytologically or histologically confirmed | 181 | – | 2006.1.1-2011.12.31 |

| de Torres et al., 2007 (38) | Spain | Prospective cohort | Spirometry confirmed | 1166 | 54 ± 8 | 74% vs 26% | CT and Biopsy | 23 | – | 2000.9-2005.12 |

| Purdue et al., 2007 (39) | Swedish | Retrospective cohort | Spirometry confirmed | 6849 | – | 6849 | ICD-7 codes 162, 163 | 175 | 175 | 1971-2001 |

| Wilson et al., 2008 (40) | USA | Prospective cohort | Spirometry confirmed | 1486 | – | – | medical records and pathology reports | 67 | – | 3.26 |

| Rodríguez et al., 2010 (41) | UK | Prospective cohort | Oxford Medical Information System [OXMIS] and Read codes | 1924 | – | – | Oxford Medical Information System [OXMIS] and Read codes | 48 | – | 1996.1.31-2001 |

| de Torres et al., 2011 (42) | USA + Spain | Prospective cohort | Spirometry confirmed | 2507 | 65 ± 9 | 2307/200 | medical records and pathology reports | 215 | 205/10 | 1997.1-2009.12 |

| Kornum et al., 2012 (43) | Danish | Prospective cohort | ICD-8 codes:491-492; ICD-10 codes: J41-J44 | 236494 | – | 129344/107150 | medical records and pathology reports | 10118 | – | 1980-2008 |

| Shen et al., 2014 (44) | China | Retrospective cohort | ICD-9-CM 491, 492, and 496 | 20730 | 70 | 13291/7439 | ICD-9-CM 162 | 729 | 575/154 | 1998-2011 |

| Hasegawa et al., 2014 (45) | Japan | Retrospective cohort | ICD-10 codes: J41, J42, J43, J44 | 172707 | – | 136632/36075 | ICD-10 codes C34 | 13930 | – | 2010.7.1-2013.3.31 |

| Roberts et al., 2011 (46) | UK | Prospective cohort | ICD10 code J44 and J45/46 (asthma) later confirmed as COPD |

9716 | 73 ± 10 | 4906/4810 | Medical records confirmed by physician | 180 | – | 2008.3-2008.8 |

| Ställberg et al., 2018 (47) | Swedish | Retrospective cohort | ICD-10 code: J44 | 17479 | – | – | ICD-10 code: C34 | 1091 | – | 2000-2014 |

| Mannino et al., 2003 (48) | USA | Prospective cohort | Spirometry confirmed | 5402 | – | 2473/2929 | ICD-9 code: 162 | 113 | – | 1971-1992 |

| Schneider et al., 2010 (49) | UK | Retrospective case-control | OXMIS codes | 35772 | – | 18351/17421 | OXMIS codes | 2585 | 1526/1059 | 1995.1.1-2005.12.31 |

| Greulich et al., 2017 (50) | Germany | Retrospective case-control | ICD-10: J41, J43, J44 | 146141 | 67.2 ± 12.41 | 51%/49% | ICD-10 code not provided | 2663 | – | 2013.1.1-2014.12.31 |

| Jo et al., 2015 (51) | Korean | Retrospective cross-sectional | ICD-10 code: J44 | 744 | 65.0 ± 9.40 | ICD-10 code: C34 | 97 | – | 2010-2012 | |

| Deniz et al., 2016 (52) | Turkey | Retrospective cross-sectional | Spirometry confirmed | 3095 | 71.9 ± 10.5 | 2434/661 | Medical records | 58 | – | 2014.1.1-2014.12.31 |

| Jung et al., 2018 (53) | Korean | Retrospective cross-sectional | ICD 10 code J44 | 15949 | 69 (60, 76) | 9039/6910 | ICD 10 code C34 | 753 | 590/163 | 2011.1-2011.12 |

| Masuda et al., 2017 (54) | Japan | Retrospective cohort | Spirometry confirmed | 920 | – | 651/269 | self-reported and confirmed by a physician | 13 | 10/3 | 2009.4-2010.3 |

| Nishida et al., 2017 (55) | Japan | Retrospective cross-sectional | Spirometry confirmed | 2309 | 69.06 ± 10.53 | 1549/760 | ICD-10 code C34 | 354 | – | 2005.9-2008.12 |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; F: female; M: male; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; -: No mentioned.

Quality assessment

We evaluated the quality of the included studies, and the average score of the included cohort studies, case-control studies, and cross-sectional studies were 7.90, 8.33, and 8.43, respectively, which suggested that the studies included in our meta-analysis were of high quality. Ten cohort studies (22, 23, 25, 34, 36, 41, 43 - 45, 48), two case-control studies (49, 50) and five cross-sectional studies (28, 37, 51, 53, 54) with scores ≥ 9 were classified as high-quality studies, and the remaining observational studies were of moderate quality. The specific score information for all included observational studies is shown in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Risk of bias for included studies.

| Study Items | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Scores | Overall of quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort studies | ||||||||||||

| Thomsen, M. 2012 (34) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | High |

| S. Chubachi, 2016 (35) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | Moderate |

| M. Divo, 2012 (13) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | Moderate |

| J.A.M. Westerik, 2017 (36) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | High |

| Lin, S. H. 2013 (37) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | Moderate |

| Sandelin, M. 2018 (22) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | High |

| Ahn, S. V. 2020 (23) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | High |

| de Torres, J. P. 2007 (38) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | Moderate |

| Purdue, M. P. 2007 (39) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | Moderate |

| Wilson, D. O. 2008 (40) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | Moderate |

| Rodríguez, L. A. 2010 (41) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | High |

| De Torres, J. P. 2011 (42) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | Moderate |

| Kornum, J. B. 2012 (43) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | High |

| Shen, T. C. 2014 (44) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | High |

| Husebø, G. R. 2019 (24) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | Moderate |

| Park, H. Y. 2020 (25) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | High |

| Machida, H. 2021 (26) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | Moderate |

| W. Hasegawa, 2014 (45) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | Moderate |

| C.M. Roberts, 2011 (46) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | Moderate |

| Ställberg, B. 2018 (47) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | Moderate |

| Mannino DM, 2003 (48) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | High |

| Case-control studies | ||||||||||||

| Schneider, C. 2010 (49) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | High |

| Greulich, T. 2017 (50) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | High |

| Sakai, T. 2020 (27) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | Moderate |

| Cross-sectional studies | ||||||||||||

| Y.S. Jo, 2015 (51) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | High |

| S. Deniz, A. 2016 (52) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | Moderate |

| Jung, H. I. 2018 (53) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | High |

| Montserrat-Capdevila, J. 2021 (28) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | High |

| Jurevičienė, E. 2022 (29) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | High |

| Masuda, S. 2017 (54) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | High |

| Nishida, Y. 2017 (55) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | Moderate |

1.Was the study’s target population a close representation of the national population in relation to relevant variables?

2.Was the sampling frame a true or close representation of the target population?

3.Was some form of random selection used to select the sample, or was a census undertaken?

4.Was the likelihood of nonresponse bias minimal?

5.Were data collected directly from the subjects (as opposed to a proxy)?

6.Was an acceptable case definition used in the study?

7.Was the study instrument that measured the parameter of interest shown to have validity and reliability?

8.Was the same mode of data collection used for all subjects?

9.Was the length of the shortest prevalence period for the parameter of interest appropriate?

10.Were the numerator(s) and denominator(s) for the parameter of interest appropriate?

Prevalence of lung cancer in COPD patients

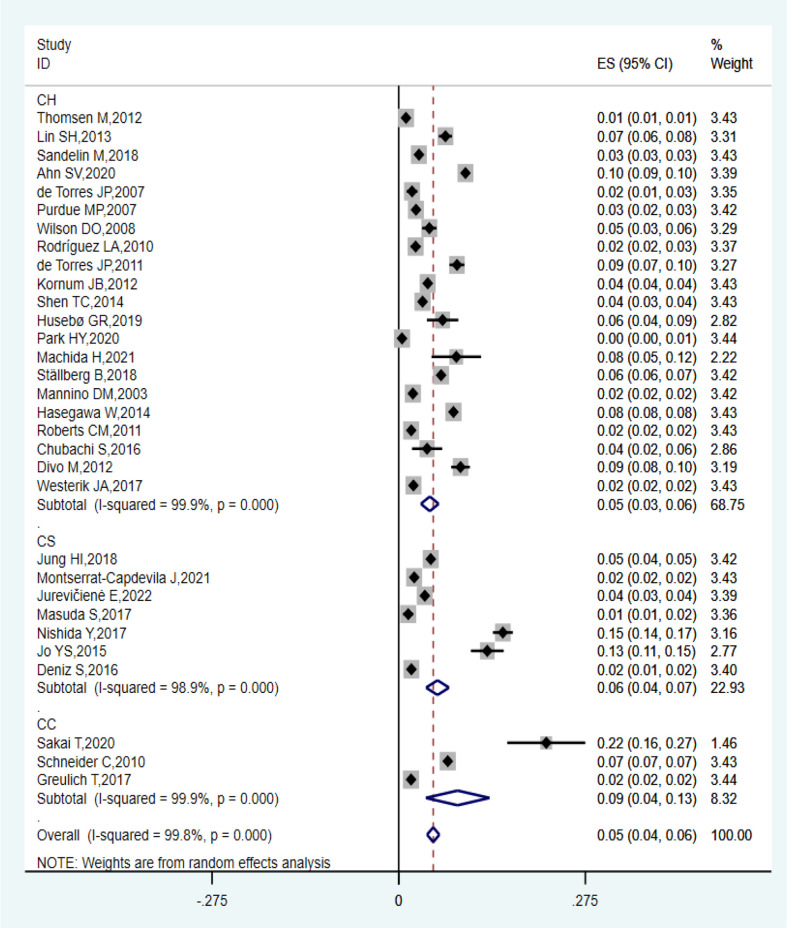

Thirty-one observational studies reported that the prevalence of lung cancer among patients with COPD ranged from 0.49% to 21.7%, and the overall estimated prevalence was 5.08% (95% CI: 4.17–6.00%; I 2 = 99.8%, P = 0.000). Of these studies, the estimated pooled prevalence of 21 cohort studies, three case-control studies, and seven cross-sectional studies were 4.58% (95% CI: 3.27–5.89%; I 2 = 99.9%, P = 0.000), 8.67% (95% CI: 4.00–13.35%; I 2 = 99.9%, P = 0.000), and 5.72% (95% CI: 4.02–7.41%; I 2 = 98.9%, P = 0.000), respectively, as shown in Figure 2 . Sensitivity analysis proved that the estimated pooled prevalence was still ≥ 4% after excluding one study at a time, which confirmed the high stability of our results in Table 3 .

Figure 2.

Forest plot showing the prevalence of lung cancer in COPD.

Table 3.

Sensitivity analysis showing the effect of lung cancer in COPD.

| Study design | Deletion | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Cohort study | Thomsen M, 2012 (34) | ES = 5.23%, 95% CI [4.29%, 6.18%] |

| Lin SH, 2013 (37) | ES = 5.02%, 95% CI [4.09%, 5.95%] | |

| Sandelin M, 2018 (23) | ES = 5.17%, 95% CI [4.22%, 6.11%] | |

| Ahn SV, 2020 (24) | ES = 4.91%, 95% CI [3.99%, 5.82%] | |

| de Torres JP, 2007 (38) | ES = 5.19%, 95% CI [4.26%, 6.12%] | |

| Purdue MP, 2007 (39) | ES = 5.18%, 95% CI [4.24%, 6.11%] | |

| Wilson DO, 2008 (40) | ES = 5.10%, 95% CI [4.17%, 6.04%] | |

| Rodríguez, L. A. 2010 (41) | ES = 5.18%, 95% CI [4.24%, 6.11%] | |

| de Torres JP, 2011 (42) | ES = 4.97%, 95% CI [4.04%, 5.89%] | |

| Kornum JB, 2012 (43) | ES = 5.14%, 95% CI [4.16%, 6.12%] | |

| Shen TC, 2014 (44) | ES = 5.15%, 95% CI [4.21%, 6.09%] | |

| Husebø GR, 2019 (24) | ES = 5.04%, 95% CI [4.12%, 5.97%] | |

| Park HY, 2020 (25) | ES = 5.22%, 95% CI [4.33%, 6.11%] | |

| Machida H, 2021 (26) | ES = 5.01%, 95% CI [4.08%, 5.93%] | |

| Ställberg B, 2018 (47) | ES = 5.04%, 95% CI [4.12%, 5.97%] | |

| Mannino DM, 2003 (48) | ES = 5.19%, 95% CI [4.26%, 6.13%] | |

| Hasegawa W, 2014 (45) | ES = 4.85%, 95% CI [4.10%, 5.59%] | |

| Roberts CM, 2011 | ES = 5.20%, 95% CI [4.26%, 6.15%] | |

| Chubachi S, 2016 (35) | ES = 5.11%, 95% CI [4.18%, 6.04%] | |

| Divo M, 2012 (13) | ES = 4.95%, 95% CI [4.02%, 5.88%] | |

| Westerik JA, 2017 (36) | ES = 5.20%, 95% CI [4.25%, 6.14%] | |

| Cross-sectional study | Jung, HI, 2018 (53) | ES = 5.10%, 95% CI [4.17%, 6.03%] |

| Montserrat-Capdevila J. 2021 (28) | ES = 5.20%, 95% CI [4.24%, 6.15%] | |

| Jurevičienė E. 2022 (29) | ES = 5.13%, 95% CI [4.20%, 6.06%] | |

| Masuda S, 2017 (54) | ES = 5.21%, 95% CI [4.28%, 6.14%] | |

| Nishida Y, 2017 (55) | ES = 4.75%, 95% CI [3.82%, 5.67%] | |

| Jo YS, 2015 (51) | ES = 4.86%, 95% CI [3.93%, 5.78%] | |

| Deniz S, 2016 (52) | ES = 5.20%, 95% CI [4.27%, 6.13%] | |

| Case-control study | Sakai T. 2020 (27) | ES = 4.84%, 95% CI [3.92%, 5.76%] |

| Schneider C, 2010 (49) | ES = 5.00%, 95% CI [4.09%, 5.91%] | |

| Greulich T, 2017 (50) | ES = 5.27%, 95% CI [4.20%, 6.35%] |

Subgroup analysis

In terms of sex, nine studies (22, 26, 39, 41, 44, 48, 49, 54, 54) investigated the prevalence of lung cancer in male patients with COPD, covering 62,627 individuals, with a prevalence ranging from 1.54% to 8.89%, and the estimated pooled prevalence was 5.09% (95% CI: 3.48–6.70%; I 2 = 98.8%, P = 0.000). Eight (22, 26, 41, 44, 48, 49, 53, 54) studies illustrated that the prevalence of lung cancer in female patients with COPD was 2.52% (95% CI: 1.57–4.05%; I 2 = 99.9%, P = 0.000) ( Table 4 ).

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis of the prevalence of lung cancer in COPD.

| Subgroups | Studies | Total | Events | Model | ES | Heterogeneity | P difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (95%CI) | I 2 | P | ||||||||

| Gender | |||||||||||

| Male | 9 | 62627 | 3472 | random | 5.09% (3.48%, 6.70%) | 98.80% | 0 | 0.000 | |||

| Female | 8 | 45620 | 1724 | random | 2.52% (1.57%, 4.05%) | 99.90% | 0 | 0.000 | |||

| Smoking status | |||||||||||

| Never smoking | 4 | 52863 | 744 | random | 0.68% (0.10%, 4.65%) | 100% | 0 | 0.000 | |||

| Former smoking | 4 | 20812 | 323 | random | 3.42% (1.51%, 5.32%) | 97.600% | 0 | 0.000 | |||

| Current smoking | 5 | 9879 | 731 | random | 8.98% (4.61%, 13.35%) | 98.40% | 0 | 0.000 | |||

| COPD severity | |||||||||||

| Mild | 6 | 5311 | 151 | random | 3.89% (2.14%, 7.06%) | 99.40% | 0 | 0.000 | |||

| Moderate | 3 | 1986 | 141 | random | 6.67% (3.20%, 10.14%) | 87.00% | 0 | 0.000 | |||

| Severe | 2 | 835 | 70 | random | 5.57% (1.89%, 16.39%) | 94.70% | 0 | 0.000 | |||

| Cancer type | |||||||||||

| Small cell carcinoma | 3 | 8213 | 35 | random | 0.78% (0.78%, 1.77%) | 99.70% | 0 | 0.000 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 3 | 8213 | 68 | random | 1.59% (0.23%, 2.94%) | 90.90% | 0 | 0.022 | |||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 3 | 8213 | 75 | random | 1.35% (0.57%, 3.23%) | 99.70% | 0 | 0.000 | |||

| Region | |||||||||||

| European | 15 | 531191 | 18711 | random | 3.21% (2.36%, 4.06%) | 99.6% | 0 | 0.000 | |||

| Western Pacific region | 12 | 287245 | 17558 | random | 7.78% (5.06%, 10.5%) | 99.9% | 0 | 0.000 | |||

| Americas | 2 | 6888 | 180 | random | 3.25% (0.88%, 5.61%) | 94.40% | 0 | 0.007 | |||

CH, Cohort study; CS, Cross-sectional study; CC, Case-control study.

Six studies comprehensively described the influence of smoking status on the prevalence of lung cancer in patients with COPD. Of these studies, the prevalence of lung cancer was estimated in current smokers in five (23, 26, 39, 42, 48), in former smokers in four (23, 25, 39, 48), and in never smokers in four (23, 25, 39, 48). The estimated prevalence according to the smoking status was 8.98% (95% CI: 4.61–13.35%; I 2 = 98.4%, P = 0.000), 3.42% (95% CI: 1.51–5.32%; I 2 = 97.6%, P = 0.000), and 0.68% (95% CI: 0.10–4.65%; I 2 = 100%, P = 0.000), respectively ( Table 4 ).

Regarding the severity of COPD, six studies (26, 39, 40, 42, 48, 54) provided comprehensive information on the incidence of COPD combined with lung cancer at different stages. Among them, six (26, 39, 40, 42, 48, 54), three (26, 40, 42), and two (26, 42) studies reported lung cancer prevalence in patients with mild, moderate, and severe COPD, respectively, with a pooled prevalence of 3.89% (95% CI: 2.14–7.06%; I 2 = 99.4%, P = 0.000), 6.67% (95% CI: 3.20–10.14%; I 2 = 87%, P = 0.000), and 5.57% (95% CI: 1.89–16.39%; I 2 = 94.7%, P = 0.000), respectively ( Table 4 ).

With respect to the histological subtype of lung cancer, three studies (27, 38, 39) described specific categories and the overall pooled prevalence of small cell lung cancer, adenocarcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma in patients with COPD was 0.78% (95% CI: 0.34–1.77%; I 2 = 99.7%, P = 0.000), 1.59% (95% CI: 0.23–2.94%; I 2 = 90.9%, P = 0.022) and 1.35% (95% CI: 0.57–3.23%; I 2 = 99.7%, P = 0.000), respectively ( Table 4 ).

The prevalence of lung cancer among patients with COPD in different regions is of great significance. Fifteen (22, 24, 28, 29, 34, 36, 38, 39, 41, 43, 46, 47, 49, 50, 52) studies reported lung cancer prevalence in patients with COPD in the European region, ranging from 1.07% to 7.23%, with an estimated prevalence of 3.21% (95% CI: 2.36–4.06%; I 2 = 99.6%, P = 0.000). In addition, 12 (23, 25–27, 35, 37, 44, 45, 51, 53–55) and two (40, 48) studies reported that the prevalence of lung cancer in patients with COPD in the Western Pacific and the Americas region, with a pooled prevalence of 7.78% (95% CI: 5.06–10.5%; I 2 = 99.9%, P = 0.000) and 3.25% (95% CI: 0.88–5.61%; I 2 = 94.4%, P = 0.007), respectively ( Table 4 ).

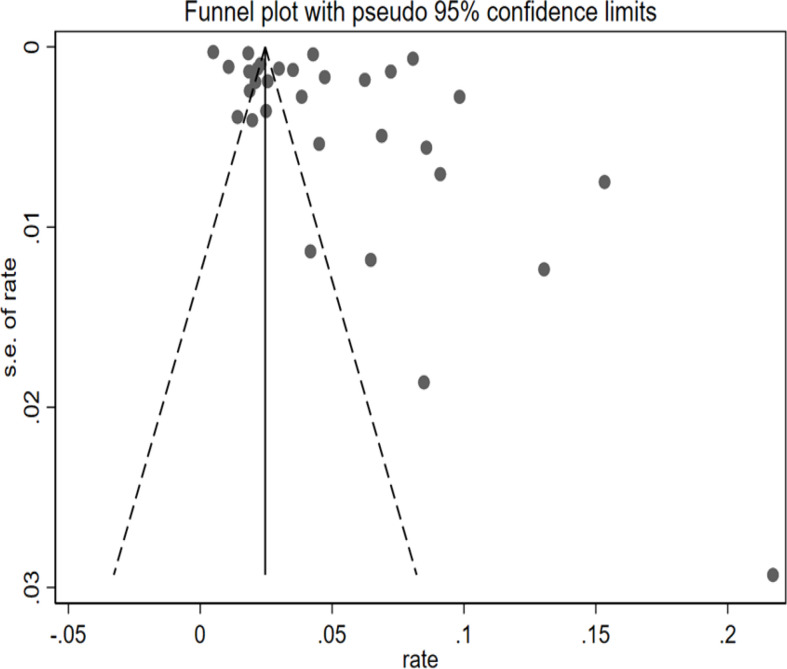

Publication bias

The funnel plot exhibited visual asymmetry, whereas Egger’s test regression values (P = 0.052) indicated that the difference was insignificant in Figure 3 . Regression tests indicated no publication bias in this meta-analysis.

Figure 3.

Funnel plot showing the effect of lung cancer in COPD.

Risk factors for lung cancer in COPD

Four studies (24, 44, 48, 53) reported the sex of patients with COPD and lung cancer, and the pooled OR suggested that sex was not a risk factor for lung cancer in COPD. Smoking status was examined in six studies (24–26, 39, 48, 49), and the analysis results indicated that smoking status of any type did increase the risk of lung cancer, with current smokers showing a higher risk (P ≤ 0.05). Five studies (24, 26, 40, 42, 48) focused on the COPD severity as a risk factor for lung cancer, and the results (pooled OR) showed that the risk was statistically significant in patients with mild and moderate COPD ( Table 5 ).

Table 5.

Analysis of the risk factors of lung cancer in COPD.

| Risk factors | Studies | Model | OR | Heterogeneity | P difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (95% CI) | I 2 | P | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 4 | Random | 0.48 (0.09, 2.66) | 99.50% | 0 | 0.398 |

| Female | 2 | Random | 0.13 (0.00, 4.86) | 99.70% | 0 | 0.268 |

| COPD severity | ||||||

| Mild | 3 | Fixed | 1.79(1.23, 2.60) | 21.90% | 0.278 | 0.002 |

| Moderate | 3 | Fixed | 2.14(1.44, 3.18) | 0 | 0.931 | 0.000 |

| Severe | 2 | Fixed | 1.36(0.80, 2.31) | 0 | 0.419 | 0.251 |

| Very severe | 1 | Fixed | 0.60(0.18, 1.98) | 0 | 0.569 | 0.404 |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Never smoking | 3 | Fixed | 2.94(2.38, 3.64) | 31.40% | 0.233 | 0.000 |

| Former smoking | 4 | Random | 3.17(1.30, 7.74) | 91.10% | 0 | 0.011 |

| Current smoking | 5 | Random | 3.94(1.28, 12.12) | 95.10% | 0 | 0.017 |

Discussion

Our review synthesized the current evidence on the prevalence of lung cancer in COPD in 31 populational-based studies covering 829,490 individuals with COPD to show a pooled prevalence of 5.08%, which indicated that lung cancer was an important comorbidity in patients with COPD. Our comprehensive review found that COPD was associated with an increased risk of lung cancer, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies (56, 57). A meta-analysis of a cohort study performed by Zhang et al. (56) showed that the prevalence of lung cancer in patients with COPD was 2.06%, and its subgroup analysis also revealed that locations and COPD severity played a role in increasing the risk of lung cancer. However, their results showed a lower prevalence than ours, which may be attributed to the fact that five (58–62) studies of lung cancer mortality in patients with COPD were included in their analysis, which may have affected the accuracy of the conclusion, particularly underestimating the prevalence of lung cancer in patients with COPD. A population-based review reported that patients with COPD were 6.35 times more likely to have lung cancer than those without COPD, and the pooled prevalence of lung cancer in patients with COPD was 2.79%, which was somewhat different from our results (57). The reason may be related to the different search databases, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and sample size. Unfortunately, their study did not include subgroup analysis or sensitivity analyses, which were adopted in ours to explore the sources of heterogenicity and to confirm that the results had a reliable stability. Furthermore, we pooled the analyses on the risk factors of lung cancer in COPD in order to provide stronger evidence for the relationship between COPD and lung cancer, with the aim of improved prevention and disease management.

The prevalence in male was evidently higher than that in female patients, which is different from the study of Zhang et al. (56). The reason may be that the pooled analysis of a previous systematic review included two studies on lung cancer mortality in COPD, which strikingly affected the analysis results. Also, compared with former smokers, the prevalence of current smokers clearly increased, whereas never smokers with COPD had an exceedingly low risk of lung cancer, indicating that to quit smoking was necessary in patients with COPD. The prevalence was closely related to the severity of COPD (63, 64), and the increased lung cancer risk was 20% when FEV1% predicted was decreased by 10% (65). However, our analysis of patients with very severe COPD showed that the prevalence of lung cancer was statistically insignificant, which was mainly attributed to insufficient sample size and demographics discrepancy. The histological subtype showed that adenocarcinoma was the most common cancer in patients with COPD, followed by squamous cell carcinoma, whereas the probability of small-cell occurrence was lower, which was consistent with a previous study (66). The prevalence of lung cancer in COPD was higher in the Western Pacific region than in the European and the Americas regions, which showed similar prevalence. These differences may owe to the relatively backward economic development as well as different aging population and medical conditions in the Western Pacific region.

Understanding the risk factors of lung cancer in patients with COPD can facilitate early prevention and management, thereby reducing the risk of lung cancer. Our result proved that sex should not be interpreted as a risk factor for lung cancer in patients with COPD, which may be associated with increasing female smoking, passive smoking, and indoor air pollutants such as the use of biomass fuel, cooking fumes, as well as poor ventilation systems (67, 68). As in other recent epidemiologic studies (25, 69, 70), the most common risk factor in our study was current smoking, followed by former smoking, and never smoking, which further verifies the harmful effects of tobacco. Also, COPD severity was a common risk factor for lung cancer. In this regard, mild and moderate COPD were statistically significant, which was principally attributed to different demographic characteristics, investigation period, study site, data extraction and processing methods.

The underlying mechanisms of lung cancer predisposition in patients could be deduced and explained based on the characteristics of COPD. First, the inflammatory microenvironment occurring in COPD may increase the probability of DNA damage and mutations (71, 72). Second, some susceptible genes related to COPD can affect the immune microenvironment of the lung by changing their expression pattern in various immune cells, which may lead in turn to the occurrence of lung cancer in COPD (73–75). Third, matrix metalloproteinases not only affect the progression of COPD but also degrade elastic fibers and may thus contribute to the progression and invasion of lung cancer (76, 77). Fourth, tissue hypoxia caused by obstruction of small airways and alveolar capillaries activates hypoxia-inducible factor 1, which can cause tumorigenesis, angiogenesis, and cell multiplication, and therefore accompany a metastatic phenotype (78). In summary, the pathological mechanism of lung cancer in COPD is complex and is related to genetic susceptibility, environmental factors, epithelial-mesenchymal transformation, endothelial-mesenchymal transformation, and extracellular matrix components and functions.

To the best of our knowledge, this systematic review is the largest and most comprehensive of its kind on lung cancer prevalence in patients with COPD. Subgroup and sensitivity analyses were performed to confirm the stability of results. In addition, the quality assessment of most included studies was better, which may have strengthened the reliability of the analysis results. Despite its strengths, our meta-analysis also has several limitations. First, owning to the differences in investigation periods, locations, sample sizes, and demographic characteristics, the heterogeneity of the pooled data was high, which could not be solved even by subgroup analysis. Furthermore, incomplete and missing reports on sex, smoking status, COPD severity, and other variables in the included studies caused imperfect comparisons of all influencing factors. Therefore, positive results should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusions

This review revealed that the prevalence of lung cancer in patients with COPD is higher, which was supported by evidence-based studies. These findings help to further promote the attention and prevention of lung cancer in patients with COPD and contribute to the development of global management strategies to reduce the occurrence of lung cancer in COPD.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material . Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JL and XL contributed to the conception and design of the article; GZ and XL formulated the retrieval strategy and conducted the literature search. GZ, XL, SL, HuZ, and HaZ would answer for data interpretation and analysis; GZ and XL drafted the manuscript; XL, SL, HuZ, HaZ, and JL read and revised it. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Chinese Medicine Inheritance and Innovation “Hundred and Ten Million” Talent Project – Chief Scientist of Qi-Huang Project ([2020] No. 219); Zhong-yuan Scholars and Scientists Project (No. 2018204); Characteristic backbone discipline construction project of Henan Province (STG-ZYXKY-2020007).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2022.947981/full#supplementary-material

Search strategy. The retrieval strategies and steps for searching PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library.

PRISMA checklist.PRISMA checklist was adopted to normalize the report of this overview, in which the page numbers of the content were detailed.

References

- 1. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease . Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2022 REPORT) . Available at: https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/GOLD-REPORT-2022-v1.0-12Nov2021_WMV.pdf.

- 2. GBD . Chronic respiratory disease collaborators. prevalence and attributable health burden of chronic respiratory diseases, 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet Respir Med (2020) 8(6):585–96. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30105-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. GBD 2015 Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators . Global, regional, and national deaths, prevalence, disability-adjusted life years, and years lived with disability for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, 1990-2015: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet Respir Med (2017) 5(9):691–706. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30293-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arce-Ayala YM, Diaz-Algorri Y, Craig T, Ramos-Romey C. Clinical profile and quality of life of Puerto ricans with hereditary angioedema. Allergy Asthma Proc (2019) 40:103–10. doi: 10.2500/aap.2019.40.4200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease . Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2021 REPORT) . Available at: https://goldcopd.org/2021-gold-reports/.

- 6. WHO . Global health estimates: Life expectancy and leading causes of death and disability . Available at: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates.

- 7. WHO . The top 10 causes of death . Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death.

- 8. Rehman A Ur, MA AH, SA M, Shah S, Abbas S, Hyder Ali IAB, et al. The economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in the USA, Europe, and Asia: Results from a systematic review of the literature. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res (2020) 20(6):661–72. doi: 10.1080/14737167.2020.1678385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhu B, Wang Y, Ming J, Chen W, Zhang L. Disease burden of COPD in China: A systematic review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis (2018) 27(13):1353–64. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S161555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zafari Z, Li S, Eakin MN, Bellanger M, Reed RM. Projecting long-term health and economic burden of COPD in the united states. Chest (2021) 159(4):1400–10. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.09.255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Negewo NA, Gibson PG, McDonald VM. COPD and its comorbidities: Impact, measurement and mechanisms. Respirology (2015) 20(8):1160–71. doi: 10.1111/resp.12642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smith MC, Wrobel JP. Epidemiology and clinical impact of major comorbidities in patients with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis (2014) 27(9):871–88. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S49621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Divo M, Cote C, de Torres JP, Casanova C, Marin JM, Pinto-Plata V, et al. Comorbidities and risk of mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2012) 186(2):155–61. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201201-0034OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Young RP, Duan F, Chiles C, Hopkins RJ, Gamble GD, Greco EM, et al. Airflow limitation and histology shift in the national lung screening trial. the NLST-ACRIN cohort substudy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2015) 192(9):1060–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201505-0894OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carr LL, Jacobson S, Lynch DA, Foreman MG, Flenaugh EL, Hersh CP, et al. Features of COPD as predictors of lung cancer. Chest (2018) 153(6):13261335. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.01.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin (2021) 71(3):209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Detterbeck FC, Chansky K, Groome P, Bolejack V, Crowley J, Shemanski L, et al. The IASLC lung cancer stagingproject: methodology and validation used in the development of proposals for revision of the stage classification of NSCLC in the forthcoming (Eighth) edition of the TNM classification of lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol (2016) 11(09):1433–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Blandin Knight S, Crosbie PA, Balata H, Chudziak J, Hussell T, Dive C. Progress and prospects of early detection in lung cancer. Open Biol (2017) 7(9):170070. doi: 10.1098/rsob.170070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Young RP, Hopkins R. The potential impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in lung cancer screening: implications for the screening clinic. Expert Rev Respir Med (2019) 13(8):699–707. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2019.1638766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mouronte-Roibás C, Leiro-Fernández V, Fernández-Villar A, Botana-Rial M, Ramos-Hernández C, Ruano-Ravina A. COPD. Emphysema and the onset of lung cancer. A systematic review. Cancer Lett (2016) 382(2):240–4. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. de-Torres JP, Marín JM, Casanova C, Pinto-Plata V, Divo M, Cote C, et al. Identification of COPD patients at high risk for lung cancer mortality using the COPD-LUCSS-DLCO. Chest (2016) 149(4):936–42. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-1868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sandelin M, Mindus S, Thuresson M, Lisspers K, Ställberg B, Johansson G, et al. Factors associated with lung cancer in COPD patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis (2018) 13:1833–9. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S162484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ahn SV, Lee E, Park B, Jung JH, Park JE, Sheen SS, et al. Cancer development in patients with COPD: A retrospective analysis of the national health insurance service-national sample cohort in Korea. BMC Pulm Med (2020) 20(1):170. doi: 10.1186/s12890-020-01194-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Husebø GR, Nielsen R, Hardie J, Bakke PS, Lerner L, D'Alessandro-Gabazza C, et al. Risk factors for lung cancer in COPD - results from the Bergen COPD cohort study. Respir Med (2019) 152:81–8. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2019.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Park HY, Kang D, Shin SH, Yoo KH, Rhee CK, Suh GY, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer incidence in never smokers: A cohort study. Thorax (2020) 75(6):506–9. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2019-213732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Machida H, Inoue S, Shibata Y, Kimura T, Ota T, Ishibashi Y, et al. The incidence and risk analysis of lung cancer development in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Possible effectiveness of annual CT-screening. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis (2021) 16:739–49. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S287492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sakai T, Hara J, Yamamura K, Abo M, Okazaki A, Ohkura N, et al. Histopathological type of lung cancer and underlying driver mutations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) versus patients with asthma and COPD overlap: A single-center retrospective study. Turk Thorac J (2020) 21(2):75–9. doi: 10.5152/TurkThoracJ.2019.18100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Montserrat-Capdevila J, Marsal JR, Ortega M, Castañ-Abad MT, Alsedà M, Barbé F, et al. Clinico-epidemiological characteristics of men and women with a new diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A database (SIDIAP) study. BMC Pulm Med (2021) 21(1):44. doi: 10.1186/s12890-021-01392-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jurevičienė E, Burneikaitė G, Dambrauskas L, Kasiulevičius V, Kazėnaitė E, Navickas R, et al. Epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) comorbidities in Lithuanian national database: A cluster analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2022) 19(2):970. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19020970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Taylor KS, Mahtani KR, Aronson JK. Summarising good practice guidelines for data extraction for systematic reviews and meta-analysis. BMJ Evid Based Med (2021) 26(3):88–90. doi: 10.1136/bmjebm-2020-111651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, Blyth F, March L, Bain C, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol (2012) 65(9):934–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Freeman MF, Tukey JW. Transformations related to the angular and the square root. Ann Math Statist (1950) 21(4):607–11. doi: 10.1214/aoms/1177729756 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thomsen M, Dahl M, Lange P, Vestbo J, Nordestgaard BG. Inflammatory biomarkers and comorbidities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2012) 186(10):982–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201206-1113OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chubachi S, Sato M, Kameyama N, Tsutsumi A, Sasaki M, Tateno H, et al. Identification of five clusters of comorbidities in a longitudinal Japanese chronic obstructive pulmonary disease cohort. Respir Med (2016) 117:272–9. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Westerik JA, Metting EI, van Boven JF, Tiersma W, Kocks JW, Schermer TR. Associations between chronic comorbidity and exacerbation risk in primary care patients with COPD. Respir Res (2017) 18(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s12931-017-0512-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lin SH, Ji BC, Shih YM, Chen CH, Chan PC, Chang YJ, et al. Comorbid pulmonary disease and risk of community-acquired pneumonia in COPD patients. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis (2013) 17(12):1638–44. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.13.0330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. de Torres JP, Bastarrika G, Wisnivesky JP, Alcaide AB, Campo A, Seijo LM, et al. Assessing the relationship between lung cancer risk and emphysema detected on low-dose CT of the chest. Chest (2007) 132(6):1932–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Purdue MP, Gold L, Järvholm B, Alavanja MC, Ward MH, Vermeulen R. Impaired lung function and lung cancer incidence in a cohort of Swedish construction workers. Thorax (2007) 62(1):51–6. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.064196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wilson DO, Weissfeld JL, Balkan A, Schragin JG, Fuhrman CR, Fisher SN, et al. Association of radiographic emphysema and airflow obstruction with lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2008) 178(7):738–44. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200803-435OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rodríguez LA, Wallander MA, Martín-Merino E, Johansson S. Heart failure, myocardial infarction, lung cancer and death in COPD patients: A UK primary care study. Respir Med (2010) 104(11):1691–9. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. de Torres JP, Marín JM, Casanova C, Cote C, Carrizo S, Cordoba-Lanus E, et al. Lung cancer in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease– incidence and predicting factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2011) 184(8):913–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0430OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kornum JB, Sværke C, Thomsen RW, Lange P, Sørensen HT. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cancer risk: A Danish nationwide cohort study. Respir Med (2012) 106(6):845–52. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shen TC, Chung WS, Lin CL, Wei CC, Chen CH, Chen HJ, et al. Does chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with or without type 2 diabetes mellitus influence the risk of lung cancer? Result from a population-based cohort study. PloS One (2014) 9(5):e98290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hasegawa W, Yamauchi Y, Yasunaga H, Sunohara M, Jo T, Matsui H, et al. Factors affecting mortality following emergency admission for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMC Pulm Med (2014) 14(1):151. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-14-151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Roberts CM, Stone RA, Lowe D, Pursey NA, Buckingham RJ. Co-Morbidities and 90-day outcomes in hospitalized COPD exacerbations. COPD (2011) 8(5):354–61. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2011.600362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ställberg B, Janson C, Larsson K, Johansson G, Kostikas K, Gruenberger JB, et al. Real-world retrospective cohort study ARCTIC shows burden of comorbidities in Swedish COPD versus non-COPD patients. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med (2018) 28(1):33. doi: 10.1038/s41533-018-0101-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mannino DM, Aguayo SM, Petty TL, Redd SC. Low lung function and incident lung cancer in the united states: data from the first national health and nutrition examination survey follow-up. Arch Intern Med (2003) 163(12):1475–80. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.12.1475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schneider C, Jick SS, Bothner U, Meier CR. Cancer risk in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pragmat Obs Res (2010) 1:15–23. doi: 10.2147/POR.S13176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Greulich T, Weist BJD, Koczulla AR, Janciauskiene S, Klemmer A, Lux W, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities in COPD patients by disease severity in a German population. Respir Med (2017) 132:132–8. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2017.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jo YS, Choi SM, Lee J, Park YS, Lee SM, Yim JJ, et al. The relationship between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and comorbidities: A cross-sectional study using data from KNHANES 2010-2012. Respir Med (2015) 109(1):96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Deniz S, Şengül A, Aydemir Y, Çeldir Emre J, Özhan MH. Clinical factors and comorbidities affecting the cost of hospital-treated COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis (2016) 11:3023–30. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S120637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Jung HI, Park JS, Lee MY, Park B, Kim HJ, Park SH, et al. Prevalence of lung cancer in patients with interstitial lung disease is higher than in those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Med (Baltimore) (2018) 97(11):e0071. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Masuda S, Omori H, Onoue A, Lu X, Kubota K, Higashi N, et al. Comorbidities according to airflow limitation severity: data from comprehensive health examination in Japan. Environ Health Prev Med (2017) 22(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s12199-017-0620-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Nishida Y, Takahashi Y, Tezuka K, Yamazaki K, Yada Y, Nakayama T, et al. A comprehensive analysis of association of medical history with airflow limitation: A cross-sectional study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis (2017) 12:2363–71. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S138103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhang X, Jiang N, Wang L, Liu H, He R. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and risk of lung cancer: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Oncotarget (2017) 8(44):78044–56. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Butler SJ, Ellerton L, Roger S, Goldstein RS, Brooks D. Prevalence of lung cancer in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review. Respir Medicine: X (2019) 1:100003. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20351 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58. van Gestel YR, Hoeks SE, Sin DD, Hüzeir V, Stam H, Mertens FW, et al. COPD and cancer mortality: the influence of statins. Thorax (2009) 64(11):963–7. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.116731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Leung CC, Lam TH, Yew WW, Law WS, Tam CM, Chang KC, et al. Obstructive lung disease does not increase lung cancer mortality among female never-smokers in Hong Kong. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis (2012) 16(4):546–52. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Aldrich MC, Munro HM, Mumma M, Grogan EL, Massion PP, Blackwell TS, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and subsequent overall and lung cancer mortality in low-income adults. PloS One (2015) 10(3):e0121805. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Oelsner EC, Carr JJ, Enright PL, Hoffman EA, Folsom AR, Kawut SM, et al. Per cent emphysema is associated with respiratory and lung cancer mortality in the general population: A cohort study. Thorax (2016) 71(7):624–32. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Turner MC, Chen Y, Krewski D, Calle EE, Thun MJ. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with lung cancer mortality in a prospective study of never smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2007) 176(3):285–90. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200612-1792OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Su Z, Jiang Y, Li C, Zhong R, Wang R, Wen Y, et al. Relationship between lung function and lung cancer risk: A pooled analysis of cohorts plus mendelian randomization study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol (2021) 147(10):2837–49. doi: 10.1007/s00432-021-03619-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kang HS, Park YM, Ko SH, Kim SH, Kim SY, Kim CH, et al. Impaired lung function and lung cancer incidence: A nationwide population-based cohort study. J Clin Med (2022) 11(4):1077. doi: 10.3390/jcm11041077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Fry JS, Hamling JS, Lee PN. Systematic review with meta-analysis of the epidemiological evidence relating FEV1 decline to lung cancer risk. BMC Cancer (2012) 12(1):498. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Littman AJ, Thornquist MD, White E, Jackson LA, Goodman GE, Vaughan TL. Prior lung disease and risk of lung cancer in a large prospective study. Cancer Causes Control (2004) 15(8):819–27. doi: 10.1023/B:CACO.0000043432.71626.45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Jemal A, Miller KD, Ma J, Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Islami F, et al. Higher lung cancer incidence in young women than young men in the united states. N Engl J Med (2018) 378(21):1999–2009. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1715907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Mu L, Liu L, Niu R, Zhao B, Shi J, Li Y, et al. Indoor air pollution and risk of lung cancer among Chinese female non-smokers. Cancer Causes Control (2013) 24(3):439–50. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-0130-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hou W, Hu S, Li C, Ma H, Wang Q, Meng G, et al. Cigarette smoke induced lung barrier dysfunction, EMT, and tissue remodeling: A possible link between COPD and lung cancer. BioMed Res Int (2019) 2019:2025636. doi: 10.1155/2019/2025636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zhai R, Yu X, Wei Y, Su L, Christiani DC. Smoking and smoking cessation in relation to the development of co-existing non-small cell lung cancer with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Cancer (2014) 134(4):961–70. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bernardo I, Bozinovski S, Vlahos R. Targeting oxidant dependent mechanisms for the treatment of COPD and its comorbidities. Pharmacol Ther (2015) 155:60–79. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Houghton AM. Mechanistic links between COPD and lung cancer. Nat Rev Cancer (2013) 13(4):233–45. doi: 10.1038/nrc3477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ziółkowska-Suchanek I, Mosor M, Gabryel P, Grabicki M, Żurawek M, Fichna M, et al. Susceptibility loci in lung cancer and COPD: Association of IREB2 and FAM13A with pulmonary diseases. Sci Rep (2015) 5(1):13502. doi: 10.1038/srep13502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Jiang D, Wang Y, Liu M, Si Q, Wang T, Pei L, et al. A panel of autoantibodies against tumor-associated antigens in the early immunodiagnosis of lung cancer. Immunobiology (2020) 225(1):151848. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2019.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Sandri BJ, Masvidal L, Murie C, Bartish M, Avdulov S, Higgins L, et al. Distinct Cancer-Promoting stromal gene expression depending on lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2019) 200(3):348–358. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2018010080OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kraen M, Frantz S, Nihlén U, Engström G, Löfdahl CG, Wollmer P, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases in COPD and atherosclerosis with emphasis on the effects of smoking. PloS One (2019) 14(2):e0211987. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Houghton AM. Common mechanisms linking chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer. Ann Am Thorac Soc (2018) 15(Suppl 4):S273S277. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201808537MG [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. De la Garza MM, Cumpian AM, Daliri S, Castro-Pando S, Umer M, Gong L, et al. COPD-type lung inflammation promotes K-ras mutant lung cancer through epithelial HIF-1α mediated tumor angiogenesis and proliferation. Oncotarget (2018) 9(68):32972–83. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.26030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Search strategy. The retrieval strategies and steps for searching PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library.

PRISMA checklist.PRISMA checklist was adopted to normalize the report of this overview, in which the page numbers of the content were detailed.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material . Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.