Abstract

Formation of spores from vegetative bacteria by Bacillus subtilis is a primitive system of cell differentiation. Critical to spore formation is the action of a series of sporulation-specific RNA polymerase ς factors. Of these, ςF is the first to become active. Few genes have been identified that are transcribed by RNA polymerase containing ςF (E-ςF), and only two genes of known function are exclusively under the control of E-ςF, spoIIR and spoIIQ. In order to investigate the features of promoters that are recognized by E-ςF, we studied the effects of randomizing sequences for the −10 and −35 regions of the promoter for spoIIQ. The randomized promoter regions were cloned in front of a promoterless copy of lacZ in a vector designed for insertion by double crossover of single copies of the promoter-lacZ fusions into the amyE region of the B. subtilis chromosome. This system made it possible to test for transcription of lacZ by E-ςF in vivo. The results indicate a weak ςF-specific −10 consensus, GG/tNNANNNT, of which the ANNNT portion is common to all sporulation-associated ς factors, as well as to ςA. There was a rather stronger −35 consensus, GTATA/T, of which GNATA is also recognized by other sporulation-associated ς factors. The looseness of the ςF promoter requirement contrasts with the strict requirement for ςA-directed promoters of B. subtilis. It suggests that additional, unknown, parameters may help determine the specificity of promoter recognition by E-ςF in vivo.

Formation of spores from vegetative bacteria by Bacillus subtilis is a primitive system of cell differentiation. A hallmark of B. subtilis sporulation is an asymmetric division that produces two cells of unequal size, the smaller prespore and the larger mother cell. The prespore develops into the mature, heat-resistant spore, whereas the mother cell ultimately lyses. These radically different developmental fates are in part determined by the action of a series of sporulation-specific RNA polymerase ς factors: ςF and ςG in the prespore and ςE and ςK in the mother cell. Of these, ςF is the first to become active (reviewed in references 17 and 36).

Sigma factors determine the promoter recognition specificity of RNA polymerase. Comparative analysis of different promoters and analysis of promoter mutations have revealed that two regions centered at approximately 35 and 10 nucleotides upstream of the transcription start point are of prime importance for promoter recognition directed by the majority of ς factors. They are generally referred to as the −35 and −10 regions. By far the most extensively studied promoters are those for the major vegetative ς factors ς70 of Escherichia coli and ςA of B. subtilis. For both of these ς factors, the consensus −35 sequence is TTGACA and the −10 consensus is TATAAT. The distance between these two sequences is also important and varies mostly between 16 and 18 nucleotides. Although the sequences at these two regions are not strictly conserved, B. subtilis promoters conform much more closely to the consensus than do those of E. coli (11). The different promoters for the sporulation-associated ς factors of B. subtilis are less firmly defined (9).

The complex regulation of ςF activation is increasingly becoming understood (16, 17). However, much less is known about promoters recognized by RNA polymerase containing ςF (E-ςF). Few genes have been identified that are transcribed by E-ςF (9). The two genes of known function that are exclusively under the control of E-ςF are spoIIR (13, 20) and spoIIQ (19); PspoIIQ is much the stronger of the two promoters. Several E-ςF-transcribed genes are also transcribed by E-ςG (9), whose promoter specificity overlaps that of E-ςF (9), whereas the specificity of one overlaps that of E-ςB (28).

In order to investigate the features of promoters that are recognized by E-ςF, we have employed a method based on that developed by Oliphant and Struhl (23, 24) to study ςA promoters of E. coli. The method utilizes chemically synthesized DNA sequences that are degenerate in a predefined region. In the present study, the randomized sequences were for the −10 and −35 regions of the promoter for spoIIQ. Randomized promoter regions were cloned in front of a promoterless copy of lacZ in a vector designed for insertion by double crossover of single copies of the promoter-lacZ fusions into the amyE region of the B. subtilis chromosome. This system made it possible to test for transcription of lacZ by E-ςF in vivo. The results indicate a weak ςF-specific −10 consensus and a rather stronger −35 consensus. The looseness of the ςF promoter requirement contrasts with the strict requirement for ςA promoters (11) and suggests that additional factors may determine the specificity of promoter recognition by E-ςF in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

The E. coli strain used for all cloning and clone bank amplification was DH5α [F− endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) supE44 thi-1 λ− recA1 gyrA96 relA1 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 φ80dlacZΔM15]. The parental B. subtilis strain was BR151. The B. subtilis strains used are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

B. subtilis strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotype |

|---|---|

| BR151 | trpC2 lys-3 metB10 |

| EIA54 | trpC2 metB10 spoIIAΔ4 spoIIG::spc |

| EIA87 | trpC2 lys-3 spoIIGΔI amyE::erm |

| SL5037 | trpC2 metB10 spoIIAΔ4 |

| SL5618 | trpC2 lys-3 spoIIIGΔ1 |

| SL7541 | trpC2 pheA1 spoIIGB::spc |

| SL7542 | trpC2 pheA1 spoIIIGΔ1 Pspac-spoIIAC |

Plasmids.

All plasmids were maintained in E. coli DH5α. Plasmid pEIA84 is a derivative of integrative plasmid pDH32 (35), in which the spoIIQ promoter region extending from −200 to +9 was amplified by PCR and inserted into the EcoRI site (made blunt with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase) of pDH32, which is located immediately upstream of the lacZ ribosome binding site. Plasmid pEIA96 is a derivative of pDH32 (35) in which the cat cassette was removed by digestion with EcoRI and StuI and replaced with a neo cassette from a derivative of pBEST501 (12). pEIA98 was constructed by cloning the region upstream of SpoIIQ, extending from −200 to −38 (obtained by PCR), into the EcoRI site (made blunt with Klenow) of pEIA96.

Media.

E. coli was maintained on Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or LB agar supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) when required. B. subtilis was maintained by using Schaeffer's sporulation agar (SSA) or modified Schaeffer's sporulation medium (MSSM) (30). When appropriate, B. subtilis was grown in the presence of antibiotics at the following concentrations: neomycin, 5 μg/ml; spectinomycin, 50 μg/ml. When required, 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) was added to SSA to a concentration of 100 μg/ml.

Nucleic acid manipulation.

DNA was prepared as described previously (39). DNA sequencing was done by the dideoxy-chain termination method of Sanger et al. (33), using the Circum Vent Thermal Cycle Dideoxy DNA Sequencing Kit (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.). The primers used for sequencing of cloned promoter inserts were LacZ2 (reverse) (GGGTTTTCCCGGTCG) and IIQ12 (forward) (CTATGTTCAGCAAGACGC). Cellular RNA was extracted essentially as described by Penn et al. (27). Primer extension analyses were performed as described previously (39).

The PCR was based on the protocol of Sambrook et al. (32). One hundred picomoles of each oligonucleotide and 2.0 μg of chromosomal template DNA, 0.2 μg of a PCR fragment, or 1.0 μg of plasmid template DNA were added to the PCR mixture. The PCR was carried out with Taq polymerase (Fisher, Pittsburgh, Pa.) or Pfu polymerase (Statagene, La Jolla, Calif.) in the appropriate amplification buffer with deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs; 0.25 mM each dNTP) in a final volume of 100 μl.

Transformation.

B. subtilis transformation was performed as described previously (31). When large numbers of colonies were being screened as donors in transformations, donor DNA was not purified. Instead, a modification of the method of Ephrati-Elizur (6) was used essentially as described previously (29). Donor strains were grown in LB broth to stationary phase, at which stage they secreted DNA onto the cell surface or into the medium (6). A volume of 0.05 ml of these cultures was used as a donor and added to 0.5 ml of the culture of a competent recipient. This method required counterselection against the donor.

Induction of the Pspac promoter by IPTG.

Overnight cultures were diluted 100-fold into prewarmed MSSM and incubated at 37°C with aeration. Induction of Pspac by addition of 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was performed as described previously (34)

β-Galactosidase activity.

B. subtilis strains grown in MSSM at 37°C were assayed with o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside as substrate essentially as described by Nicholson and Setlow (22). β-Galactosidase specific activity is expressed as nanomoles of o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside hydrolyzed per minute per milligram (dry weight) of bacteria.

Construction of randomized spoIIQ promoter clone banks.

Clone banks were constructed as described by Oliphant and Struhl (23), with some modifications. Approximately 50 pmol of oligonucleotides R10IIQup and R35IIQup was phosphorylated with 5 U of T4 polynucleotide kinase and ATP for 1 h at 37°C in separate 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes. These oligonucleotides consisted of the spoIIQ promoter region extending from −37 to +9, with positions −14 to −7 (R10IIQup) or −35 to −31 (R35IIQup) randomized. The phosphorylated oligonucleotides were cleaned by precipitation and resuspended in 10 μl of sterile distilled water. Next, 50 pmol of oligonucleotide IIQext was added, separately, to the phosphorylated R10IIQup and R35IIQup oligonucleotides. Primer IIQext has 15 bases, corresponding to spoIIQ positions +9 to −6, that hybridize to R10IIQup and R35IIQup and also a 12-nucleotide extension downstream of +9 that will form a BamHI restriction site. The mixtures were heated to 90°C for 5 min and then cooled to room temperature slowly. After the annealing, Klenow buffer (1× final concentration), dNTPs (0.25 mM final concentration of each dNTP), and 5 U of Klenow fragment were added in a final volume of 30 μl. The mixtures were incubated in 37°C for 1 h and then fractionated by electrophoresis in a 4% NuSieve GTG agarose gel. The appropriate double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) band was excised from the gel and purified by using the QIAEX II (Qiagen, Chatsworth, Calif.) gel extraction kit. Approximately 2 μg of dsDNA from each preparation was digested with BamHI and purified. The resulting oligonucleotides, with a blunt end at −37 and a BamHI site at +9, were ligated to pEIA98 previously digested with StuI and BamHI. As the yield of dsDNA was somewhat variable, the amount of insert to be added to a given amount of vector was determined empirically in order to optimize the ligation reactions. In this way, random −10 (R10) and random −35 (R35) clone banks were obtained by using the framework of PspoIIQ.

RESULTS

Test system for analysis of E-ςF-transcribed promoters.

The two well-characterized loci that are known to be transcribed only by E-ςF are spoIIR (13, 20) and spoIIQ (19). Primer extension analysis was used to identify the 5′ end of the spoIIQ transcript and hence to infer the transcription start point and promoter. RNA was isolated from B. subtilis strain SL5618 4 h after the start of sporulation. Primer extension analysis was performed, and the same 5′ end was identified with two different primers (Fig. 1). It is inferred that this represents the transcription start point. The sequence of the spoIIQ promoter is indicated in Fig. 2. The deduced spoIIQ promoter −10 and −35 regions are indicated in bold. A similar analysis was performed for spoIIR (data not shown). The deduced spoIIR promoter agreed with that predicted previously (Fig. 2) (13). Also shown are the promoter regions for genes known to be transcribed in vivo by E-ςF and whose transcription start point has been inferred from primer extension analysis.

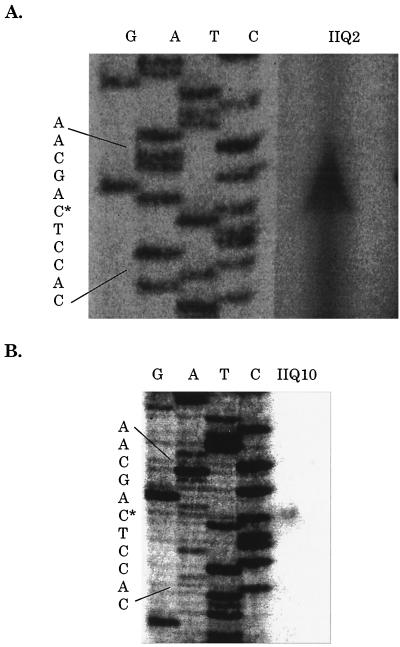

FIG. 1.

Determination of the 5′ end of spoIIQ mRNA by primer extension analysis. RNA was extracted from strain SL5618 (spoIIIGΔ1) 4 h after the end of exponential growth. Primer extension analysis was done with primer IIQ2 (TCAGCCAACGGATCCTTTACC, positions +161 to +181 from the inferred transcription start point) (A) and primer IIQ10 (CTGATTGATACCAAAGGAC, positions +128 to +147 from the inferred transcription start point) (B). Sequencing ladders using the same primers are also shown. The likely transcription start site is indicated by an asterisk.

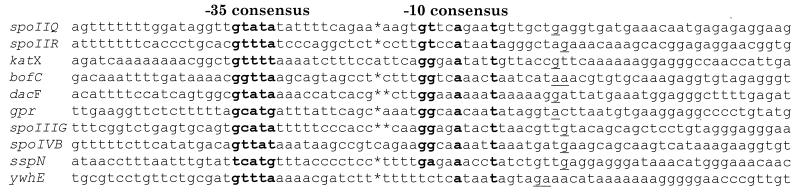

FIG. 2.

Sequence alignment of promoter regions for E-ςF-transcribed genes for which the transcription start site has been inferred by primer extension analysis. Of these, only spoIIQ, spoIIR, and katX are not also recognized by E-ςF (1–3, 5, 7, 8, 13, 34, 37–39). Asterisks indicate spaces introduced to adjust the spacing between the −10 and −35 consensuses. The underlined bases indicate the inferred transcription start points.

The spoIIQ promoter was chosen for the analysis of E-ςF-transcribed promoters because it is the strongest promoter known to be transcribed by E-ςF and it is transcribed only by E-ςF. Initial experiments indicated that the spoIIQ promoter region extending from −200 to +9 (relative to the inferred transcription start point) displayed maximal spoIIQ promoter activity as assayed with lacZ. In order to analyze the effects of alterations to the −10 and −35 regions, a vector, pEIA98, was constructed that contained the spoIIQ promoter region from −200 to −38 and had a StuI site at −38 and an adjacent BamHI site immediately upstream of the lacZ ribosome binding site. The vector was designed for insertion by double crossover of promoter-lacZ fusions into the amyE region of the B. subtilis chromosome (35) with selection for Neor. pEIA98 was digested with StuI and BamHI, and oligonucleotides extending from −37 to +9 were ligated into the plasmid to yield the spoIIQ promoter region from −200 to +9, with alterations as required.

Construction and analysis of a clone bank containing a randomized −10 ςF promoter region.

The procedure used to construct a library with the randomized −10 region is described in Materials and Methods. Positions −14 to −7 were randomized, with the rest of PspoIIQ kept constant from −200 to +9. In particular, the G at −15 was kept constant. Sun et al. (37) had shown that a G in this position in other promoters appeared to be necessary for ςF recognition (although one weak ςF /ςG promoter, for ywhE, has recently been described that has a T at this position [26]). The ligation mixtures were used to transform E. coli, and in all, approximately 250,000 transformant colonies were obtained. Plasmids were isolated from eight of these clones, and the promoter regions were sequenced. Three or four different nucleotides were found at each of the randomized positions in the eight clones, indicating that the randomization was successful; none of the eight clones displayed ςF promoter activity in B. subtilis (data not shown). The rest of the transformant colonies were recovered from the agar plates, and pooled plasmid DNA was prepared from them. This preparation was designated the R10 clone bank.

The R10 clone bank was initially screened with B. subtilis strain EIA87. Strain EIA87 has the spoIIIGΔ1 mutation and so lacks ςG, whose promoter specificity overlaps that of ςF (9). It also contains amyE::erm to help confirm that the promoter-lacZ fusions integrate at the amyE locus by double crossover. Strain EIA87 was transformed with a portion of the R10 clone bank. Approximately 55,000 transformants were obtained on SSA containing neomycin and X-Gal. Known ςF promoters are generally weak, and so any colony that had a detectable shade of blue was considered a potential positive clone. About 800 blue colonies were detected, and 500 of these were used for further study.

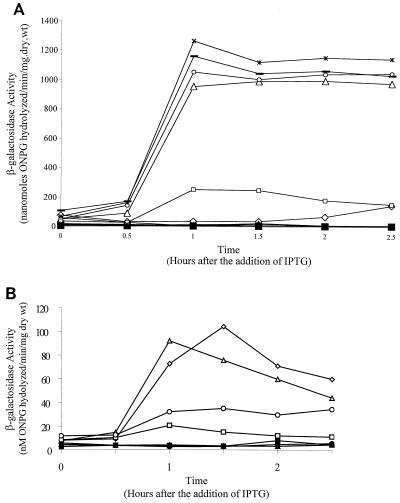

The subsequent screens of these putative ςF responsive clones utilized them as donors in transformation with different tester strains. To readily accommodate large numbers of donors, the Ephrati-Elizur (6) method was used; in this method, DNA secreted by B. subtilis is used as the donor in transformations. The tests were for lack of expression in a strain that had the structural gene for ςF deleted (EIA54) and for expression in a strain (SL7541) that had the structural gene for ςE deleted, but not the structural gene for ςF; ςE is the next factor activated after ςF during sporulation. Three hundred twenty-eight clones passed the screens. Of these, five were also tested for their response to artificial induction of ςF by addition of IPTG to a strain that had the structural gene for ςF, spoIIAC, placed under the control of the Pspac promoter; the test strain, SL7542, also contained the spoIIIGΔ1 mutation so as to avoid possible complications from ςG induction. β-Galactosidase was measured to indicate promoter activity. The results are shown in Fig. 3A. Addition of IPTG resulted in induction of β-galactosidase in all five clones but not in the strain with the lacZ fusion derived from pEIA98 (with the spoIIQ promoter region extending only from −200 to −38), confirming that the screen had identified ςF-controlled promoters. There was no significant difference in strength among the four strongest promoters.

FIG. 3.

Effect of induction of ςF on expression of lacZ associated with different spoIIQ promoter regions. Synthesis of ςF was induced by addition of IPTG to strains containing the structural gene for ςF, spoIIAC, under the control of the Pspac promoter (41). Shown are strains with alterations to the −10 region (A) and the −35 region (B) of the promoter directing lacZ. Cultures were grown in MSSM to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.3. They were then divided in two, and 1 mM IPTG was added to one of each pair. None of the cultures displayed significant β-galactosidase activity in the absence of IPTG. (A) SL7472/EIA100 (PspoIIQ [−200 to −38]) symbols: ⧫, no IPTG; ◊, 1 mM IPTG. SL7472/R10-103 symbols: ▴, no IPTG; ▵, 1mM IPTG. SL7472/R10-333 symbols: ●, no IPTG; ○, 1 mM IPTG. SL7472/R10-435 symbols: ■, no IPTG; □, 1 mM IPTG. SL7472/R10-901 symbols: ×, no IPTG; ∗, 1 mM IPTG. SL7472/R10-1024 symbols: +, no IPTG; −, 1 mM IPTG. Samples grown in the absence of IPTG produced little or no β-galactosidase, and symbols for the different cultures largely mask each other. (B) SL7472/R35-10 symbols: ⧫, no IPTG; ◊, 1 mM IPTG. SL7472/R35-20 symbols: ▴, no IPTG; ▵, 1 mM IPTG. SL7472/R35-43 symbols: ■, no IPTG; □, 1 mM IPTG. SL7472/R35-53 symbols: ●, no IPTG; ○, 1 mM IPTG. wt, weight.

Out of the 328 positive R10 clones, 35 were picked at random (by using a table of random numbers) for sequencing of the promoter region (Table 2). Four of the sequences were shifted by one base to better fit the consensus suggested by the other promoters. The variety of promoter sequences was surprising. Out of 35 R10 clones sequenced, only two were identical to each other (R10-332 and R10-333) and another one was identical to the spoIIQ −10 sequence (R10-746). If the ςF −10 consensus sequence were highly conserved, then more sequences in the set would have been expected to be identical to each other. Measurement of β-galactosidase activities of liquid cultures confirmed that the 35 clones contained promoters that were induced during sporulation. However, statistical analysis using the Kruskal-Wallis test indicated that fine distinctions could not be made between the strengths of the promoters (M. L. Higgins, personal communication).

TABLE 2.

Promoter sequences from the R10 clone bank that responded to E-ςF

| Clone | Position

|

Response to E-ςG | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −14 | −13 | −12 | −11 | −10 | −9 | −8 | −7 | ||

| R10-702 | T | T | A | A | C | T | A | T | − |

| R10-318 | T | T | A | A | C | G | A | T | − |

| R10-746 | T | T | C | A | G | A | A | T | − |

| R10-313 | T | T | T | A | A | C | C | T | − |

| R10-1003 | T | G | T | A | T | A | A | T | − |

| R10-806 | T | C | G | A | G | G | A | T | − |

| R10-838a | T | C | C | A | G | C | T | G | − |

| R10-403 | T | A | T | A | T | G | A | T | − |

| R10-332 | G | T | A | A | T | G | A | T | + |

| R10-333 | G | T | A | A | T | G | A | T | + |

| R10-301 | G | T | C | A | T | G | A | T | − |

| R10-602 | G | T | C | A | T | C | C | T | − |

| R10-510 | G | T | C | A | C | T | A | T | − |

| R10-203 | G | T | G | A | G | A | C | T | + |

| R10-435 | G | T | G | A | T | C | T | T | − |

| R10-103 | G | T | T | A | A | C | A | T | + |

| R10-948 | G | T | T | A | G | C | C | T | + |

| R10-1010 | G | T | T | A | C | A | T | T | + |

| R10-920 | G | T | T | T | G | T | A | G | + |

| R10-932b | G | T | A | A | G | A | C | T | − |

| R10-1004b | G | G | G | A | T | C | A | T | − |

| R10-1024 | G | G | T | A | G | G | A | T | + |

| R10-319 | G | G | G | A | C | C | T | T | − |

| R10-631 | G | G | T | A | G | C | T | T | − |

| R10-414b | G | G | C | A | T | C | C | T | − |

| R10-901 | G | G | T | A | G | A | C | T | + |

| R10-131 | G | C | T | A | T | G | G | T | − |

| R10-223 | G | C | G | A | T | G | T | T | − |

| R10-731 | G | C | A | A | A | C | G | T | − |

| R10-308 | G | A | G | A | T | T | C | T | − |

| R10-633 | G | A | T | A | G | C | T | G | − |

| R10-828 | G | A | T | A | T | T | G | T | − |

| R10-337 | C | T | A | A | G | G | C | T | − |

| R10-829 | C | A | C | A | C | A | C | T | + |

| R10-110 | A | C | C | A | T | A | G | T | − |

| spoIIQ | T | T | C | A | G | A | A | T | − |

The sequence was shifted to the left by one base to fit the consensus.

The sequence was shifted to the right by one base to fit the consensus.

Construction and analysis of a clone bank containing a randomized −35 ςF promoter region.

The −35 clone bank was constructed in a way similar to that used for the R10 clone bank, as described in Materials and Methods. Five bases, from −35 to −31 in the spoIIQ promoter, were randomized. Ligation mixes were used to transform E. coli, and about 7,700 transformants were obtained. The transformant colonies were recovered, and pooled plasmid DNA was prepared from them; this preparation is referred to as the R35 clone bank. The same general procedure was used to screen the R35 and R10 banks. Transformation of EIA87 with a portion of the R35 bank yielded 3,300 colonies on SSA containing neomycin and X-Gal; of these, 64 appeared blue after 2 days at 37°C. These were presumed to represent distinct clones. All 64 clones were screened for ςF-responsive promoter activity, as described for the R10 bank; 44 passed the screens and were presumed to contain ςF-controlled promoters. Four of the 44 presumptive ςF-controlled promoter clones were also tested for their response to artificial induction of ςF by addition of IPTG to a strain (SL7542) that had the structural gene for ςF, spoIIAC, placed under the control of the Pspac promoter. β-Galactosidase was measured to indicate promoter activity. The results are shown in Fig. 3B. Addition of IPTG resulted in induction of β-galactosidase in all four clones.

Out of the 44 positive R35 clones, 18 were picked at random (by using a table of random numbers) for sequencing. The results of the sequencing are in Table 3. These data suggested a tight consensus for the −35 region. Plasmids were also prepared from 11 R35 clones that were negative for ςF activity and from eight of the original E. coli transformants used to make the R35 plasmid bank; sequence analysis indicated 19 unique sequences that showed no conformity to the consensus deduced for the positive clones. This result indicated that the randomization was successful.

TABLE 3.

Promoter sequences from the R35 bank that responded to E-ςF

| Clone | Nucleotide at position:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −35 | −34 | −33 | −32 | −31 | |

| 8 | G | T | A | T | T |

| 10 | G | T | A | T | T |

| 13a | G | T | A | T | A |

| 15 | G | T | A | T | T |

| 17 | G | T | A | T | A |

| 20 | G | T | A | T | G |

| 24b | G | T | A | T | A |

| 26 | G | T | A | T | G |

| 29 | G | T | A | T | A |

| 31 | G | T | A | T | A |

| 34 | G | T | A | T | A |

| 35 | G | T | A | T | A |

| 43a | G | T | A | T | T |

| 45 | G | T | A | T | A |

| 47 | G | T | A | T | T |

| 53a | G | T | A | T | T |

| 61 | G | T | A | T | A |

| 39 | G | A | A | T | A |

| spoIIQ | G | T | A | T | A |

The sequence was shifted to the left by 1 bp to fit the consensus.

The sequence was shifted to the left by 2 bp to fit the consensus.

Distinguishing promoters recognized only by E-ςF from those recognized by both E-ςF and E-ςG.

As mentioned previously, ςF and ςG have overlapping promoter specificities (9, 37). The positive, sequenced clones from the R10 and R35 banks were tested for β-galactosidase expression in a B. subtilis strain, SL5037, that lacked ςF but had ςG activity. This strain has the spoIIAΔ4 mutation that deletes most of the spoIIA operon, including spoIIAC, which encodes ςF, and spoIIAB, which encodes a negative regulator of ςG (15, 31); apparently as a consequence of the deletion of spoIIAB, ςG becomes active even though ςF is absent (V. K. Chary and P. J. Piggot, unpublished observations). Promoter-lacZ fusions were introduced into SL5037 by transformation. As controls, dacF-lacZ (responding to ςF and ςG) and spoIIQ-lacZ (responding only to ςF) were also introduced into SL5037. Transformants were selected on SSA containing neomycin with X-Gal. Transformants were scored after a 2-day incubation at 37°C. Colonies of the positive control (dacF-lacZ) were blue; colonies of the negative control (spoIIQ-lacZ) were white. By this test, 10 of the 35 R10 promoter-lacZ fusions responded to ςG. None of the R35 promoter-lacZ fusions was responsive. The failure of the R35 clones to respond to ςG is thought to result from their having the −10 sequence of the spoIIQ promoter, which is presumed to prevent recognition by E-ςG. The responses of the different R10 clones to ςG are indicated in Table 2. Seven of the natural promoters responded to ςG, while three did not (Fig. 1). The frequencies of bases at different positions are shown in Table 4 for promoters that responded to ςG and for those that did not; data for natural promoters and for the R10 bank are combined.

TABLE 4.

Frequencies of occurrence of different nucleotides in the −10 region of promoters recognized by E-ςFa

| Promoter group and nucleotide | No. of occurrences at position:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −14 | −13 | −12 | −11 | −10 | −9 | −8 | −7 | |

| Recognized by E-ςG | ||||||||

| G | 14 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| A | 1 | 3 | 6 | 16 | 5 | 10 | 9 | 0 |

| T | 0 | 9 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 16 |

| C | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 0 |

| Not recognized by E-ςG | ||||||||

| G | 16 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 2 |

| A | 1 | 4 | 6 | 28 | 2 | 7 | 11 | 0 |

| T | 10 | 11 | 7 | 0 | 14 | 4 | 7 | 26 |

| C | 1 | 7 | 9 | 0 | 4 | 10 | 6 | 0 |

The data include 10 natural promoters and 35 promoters identified in the present study (Table 2).

Search for ςF-controlled genes by computer-assisted analysis.

The putative ςF consensus sequence, as defined above, was used to search the B. subtilis database for any potential promoter within 100 nucleotides upstream of an open reading frame by utilizing the search tools provided by the Subilist database (http://genolist.pasteur.fr/SubtiList). For the search, four different −35 sequences (GTTTD, GTATD, GCTTD, and GCATD, where D is A, G, or T) were used, with a spacer of 14 to 16 bp and GKNNANNNT (K is G or T; N is G, A, T, or C) as the −10 sequence. The search gave 193 hits, including all known ςF-controlled genes that conformed to the search sequence. Of the potential promoter regions, the following seven were chosen for further analysis: yhcR, ycdF, yveA, ykqC, yxlJ, lonB, and yfhF. The potential promoter regions were amplified by PCR and cloned into pEIA96 as a prelude to testing in strain SL7542 (Pspac-spoIIAC). The expression of only one, lonB, was induced by ςF, indicating that lonB is transcribed by E-ςF in vivo. LonB is involved in the proteolysis of ςH at low pH (18). However, a knockout mutation of lonB was generated and it had no discernible effect on growth or sporulation (data not shown). Serrano et al. have also identified lonB as an E-ςF-transcribed gene (M. Serrano, S. Hövel, C. P. Moran, Jr., A. O. Henriques, and U. Völker, personal communication).

DISCUSSION

The RNA polymerase factor ςF has a pivotal role in the sporulation of B. subtilis. Its activation is highly regulated. It is the first ς factor to display compartmentalized expression, during sporulation (10). It is made in large quantities (21), and inappropriate expression is toxic (4, 42). However, fewer promoters have been identified as specifically requiring only ςF for their expression than requiring any of the other sporulation-associated ς factors (1–3, 5, 7, 8, 13, 34, 37–39). Sun et al. originally identified four promoters that responded to E-ςF. The most striking feature that they noted was G at −15 (37) (to avoid confusion, all numbering is relative to the spoIIQ promoter [Fig. 2]). Subsequently, Londoño-Vallejo et al. (19) identified spoIIQ, which was found to have the strongest promoter known to be recognized only by E-ςF. We determined the 5′ end of ςF spoIIQ mRNA and inferred the transcription start point and hence the promoter. The promoter deviated somewhat from the previously suggested consensus but retained the G at −15. Here we report the analysis of ςF −10 and −35 region recognition determinants by using a method similar to that developed by Oliphant and Struhl (23), with the spoIIQ promoter as the base.

We tested the effects of randomizing positions −14 to −7 of the spoIIQ promoter while keeping the rest of the region from −200 to +9 fixed. Surprisingly, almost 1% of 56,000 clones with this randomized region displayed E-ςF promoter activity. Of 35 active promoters that were sequenced, only 2 were the same and only 1 was identical to the spoIIQ promoter (Table 2). This variability suggests that a large number of possible −14 to −7 sequences could be recognized by E-ςF within the context of the spoIIQ promoter region. Data for the 10 natural promoters are combined with data for the R10 sequences in Table 4. A consensus, GG/tNNANNNT, from −15 to −7 was discernible. However, the ANNNT portion, from −11 to −7, is common to all sporulation-associated ς factors, as well as to ςA (Table 5). The 10 natural ςF promoters had T or A at −16 (Fig. 2), and this position might also contribute to promoter recognition. The G at −15 had previously been considered to be essential for ςF activity (37), although one exception, the ywhE promoter, has recently been described (26). Nucleotides G are T are favored at −14. Site-directed mutatgenesis of the spoIIQ promoter confirmed the importance of the A at −11 and the T at −7 and also confirmed that a C is tolerated at −14 (E. Amaya and P. J. Piggot, unpublished observations).

TABLE 5.

Alignment of −10 consensus sequences for B. subtilis ς factorsa

| Sigma factor | Consensus sequence |

|---|---|

| ςF | G K N N A N N N T W |

| ςA | N N N T A T A A T N |

| ςG | N N N C A T W M T A |

| ςE | N C A T A C A M T N |

| ςK | N C A T A N N N T A |

The −10 consensus sequence for ςF is from the present study; other sequences were obtained from reference 9. The −10 position is underlined. B is C, G, or T; K is G or T; M is A or C; N is G, A, T, or C; W is A or T.

The limited nature of the −10 consensus identified as specific for ςF promoters was surprising. Comparison of ςA-controlled promoters has indicated that they conform much more closely to the consensus in B. subtilis than do the comparable ς70-controlled promoters in E. coli (11). The analysis by Oliphant and Struhl (23) of ς70-controlled promoters indicated that the results obtained with their method agreed very well with those obtained by analyzing natural promoters. Our preliminary analysis of B. subtilis ςA promoters by the randomized-oligonucleotide method is entirely consistent with a tighter consensus than for ς70 promoters of E. coli (A. Khvorova and P. J. Piggot, unpublished observations). It may be that the context of the spoIIQ promoter permitted the flexibility in the −10 region of the E-ςF promoters analyzed. However, the natural E-ςF promoters (Fig. 2) did not suggest a more restricted −10 region, with the possible exception of additional conformity at −9.

Analysis of the effects of randomizing five nucleotides in the −35 region suggested greater ςF specificity than at −10. Of 3,300 clones tested with a randomized −35 to −31 pentamer, 44 displayed ςF promoter activity. From these, 18 were sequenced, and 17 had the motif GTAT (−35 to −32), with 15 being GTATA/T (Table 3); analysis of nonexpressing clones in the R35 bank had indicated that the −35 to −31 region was indeed randomized in the bank. The 10 natural ςF promoters display greater variability, with T, C, or G being found at position −34 and T or A at −33 (Fig. 2). This greater flexibility in the natural promoters may indicate that the spoIIQ promoter framework somehow restricts the flexibility in recognition of the −35 region. As with the −10 consensus, much of the −35 consensus, GNATA, is recognized by other sporulation-specific ς factors (Table 6). The natural promoters also suggested that positions flanking the region tested might contribute to promoter specificity; these positions were not investigated in the present study. The natural promoter sequences are combined with the randomization data to illustrate the conformity to the −35 consensus (Table 7).

TABLE 6.

Alignment of −35 consensus sequences for B. subtilis ς factorsa

| Sigma factor | Consensus sequence |

|---|---|

| ςF | N G T A T W W N |

| ςA | T T G A C A N N |

| ςG | N G M A T R N N |

| ςE | N K M A T A W W |

| ςK | N N N A C N N N |

The −35 consensus sequence for ςF is from the present study; other sequences were obtained from reference 9. The −35 position is underlined. International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry-International Union of Biochemistry codes: M, A or C; R, A or G; W, A or T; S, C or G; Y, C or T; K, G or T; V, A, T, or G; H, A, C, or T; D, A, G, or T; B, C, G, or T; N, G, A, T, or C.

TABLE 7.

Frequency of occurrence of different nucleotides in the −35 region of promoters recognized by E-ςFa

| Nucleotide | No. of occurrences at position:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −35 | −34 | −33 | −32 | −31 | |

| G | 26 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| A | 0 | 1 | 24 | 0 | 17 |

| T | 2 | 23 | 4 | 28 | 7 |

| C | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

E-ςF has promoter specificity that overlaps that of E-ςG (9). PspoIIQ is one of the few E-ςF promoters that are not recognized by E-ςG. Ten of the promoters from the R10 library constructed in the PspoIIQ background responded to ςG, and 25 did not (Table 2). None of the promoters with a T at −14 responded to ςG (Tables 2, and 5), suggesting that the T at this position discriminated against ςG. However, a G, C, or A at this position was not sufficient among ςF promoters to determine ςG recognition. No clear discriminator was found at any other position. Scanning of known natural ςF promoters outside the regions tested here (Fig. 2) shed no further light on the situation. An example of the complexity is at position −12, where all four nucleotides were found in both classes of promoters (Tables 4 and 5), and yet R10-333, which responded to ςG, differed only at that position from R10-301, which did not respond. None of the clones from the R35 library was responsive to ςG; this is presumably a consequence of the T at position −14 in the spoIIQ promoter discriminating against ςG.

The B. subtilis database was scanned for plausible ςF promoters located within 100 nucleotides of the start of open reading frames, as defined in the database. By using the ςF consensus defined from the R10 and R35 analysis, 193 possible promoters were identified. A set of seven was chosen from this group that also fulfilled the additional criterion of having an upstream AT-rich region. This set was tested to see if the genes were transcribed in vivo by E-ςF. Only one of the seven, lonB, was transcribed by E-ςF. The inadequacy of our database predictions indicates that something additional to the −10 and −35 regions is important for E-ςF recognition. This same conclusion can be deduced from the lack of a strong ςF-specific promoter consensus sequence. It may be that the surrounding spoIIQ promoter context provides ςF recognition determinants additional to those tested in the −10 and −35 regions. However, no strong determinants were apparent when other natural ςF promoters (Fig. 2) were compared to the set of eight potential promoters. For example, A/T at position −16 (Fig. 2) was present in three of the seven nonfunctional test promoters and not present in the likely lonB promoter. However, comparison of known ςF promoters did not reveal any obvious shared sequence motif outside the −10 and −35 regions (Fig. 2).

Accessory transcription factors have been identified that strongly modulate (activate or repress) the activity of RNA polymerase containing each of the other sporulation-associated ς factors: SpoIIID, SpoVT, and GerE are associated with ςE, ςG, and ςK, respectively (17). No factor has been identified that shows comparable strong regulation of E-ςF-directed promoters, although it seems plausible that such factors exist. The transcription of spoIIIG is delayed by some 40 min compared to the transcription of other ςF-directed genes (14) and requires that ςE also be active (25), suggesting that for spoIIIG, at least, there is an absolute requirement for an accessory transcription factor. Wu and Errington (40) have reported that RsfA increases the expression of spoIIR and modulates, to some extent, the activity of E-ςF on other promoters, although not transcription of spoIIQ, the base of the present study. A requirement for unidentified transcription factors may explain, in part, the looseness of the ςF promoter consensus and the inability of our search to identify novel ςF-directed genes. However, it is also possible that the promoter recognition requirements of E-ςF are complex, with weak contributions from various positions outside the tested regions, as well as from the tested regions.

Selection of functional nucleotide sequences from randomized libraries has become a powerful technique for studying the structure and function of the nucleic acids (7). This technique (often called SELEX) has been used successfully to select in vitro the functional sequences in both RNA and DNA that are capable of binding to specific ligands or of performing a chemical reaction. The use of the randomized libraries for selection of the functional nucleic acid sequences is mostly restricted to in vitro applications, mainly because of physical limitations on the length of the library (about 15 nucleotides) imposed by the cloning and expression procedures. Although the randomized libraries are limited by length, selection from them in vivo can potentially be a very powerful tool with which to study functions of nucleic acids that involve the interactions of short nucleotide (DNA or RNA) motifs. This approach was successfully used to analyze the consensus sequence of E. coli E-ς70 promoters (23). The present study illustrates the usefulness and the limitations of SELEX logic applied to an analysis of promoter recognition determinants of E-ςF in B. subtilis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant GM43577 from the National Institutes of Health.

We are very grateful to V. K. Chary, J. D. Helmann, and M. L. Higgins for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bagyan I, Casillas-Martinez L, Setlow P. The katX gene, which codes for the catalase in spores of Bacillus subtilis, is a forespore-specific gene controlled by ςF, and KatX is essential for hydrogen peroxide resistance of the germinating spore. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2057–2062. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.8.2057-2062.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagyan I, Noback M, Bron S, Paidhungat M, Setlow P. Characterization of yhcN, a new forespore-specific gene of Bacillus subtilis. Gene. 1998;212:179–188. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00172-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cabrera-Hernandez A, Sanchez-Salas J-L, Paidhungat M, Setlow P. Regulation of four genes encoding small, acid-soluble spore proteins in Bacillus subtilis. Gene. 1999;232:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00124-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coppolecchia R, DeGrazia H, Moran C P., Jr Deletion of spoIIAB blocks endospore formation in Bacillus subtilis at an early stage. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6678–6685. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.21.6678-6685.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Decatur A, Losick R. Identification of additional genes under the control of the transcription factor ςF of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5039–5041. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.5039-5041.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ephrati-Elizur E. Spontaneous transformants in Bacillus subtilis. Genet Res. 1968;11:83–96. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300011216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gold L, Brown D, He Y-Y, Shtatland T, Singer B S, Wu Y. From oligonucleotide shapes to genomic SELEX: novel biological regulatory loops. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:59–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomez M, Cutting S M. Expression of the Bacillus subtilis spoIVB gene is under dual ςF/ςG control. Microbiology. 1996;142:3453–3457. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-12-3453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haldenwang W G. The sigma factors of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:1–30. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.1-30.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harry E, Pogliano K, Losick R. Cell-specific gene expression in B. subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3386–3393. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.12.3386-3393.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helmann J D. Compilation and analysis of Bacillus subtilis ςA-dependent promoter sequences: evidence for extended contact between RNA polymerase and upstream promoter DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;13:2351–2360. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.13.2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Itaya M, Kondo K, Tanaka T. A neomycin resistance gene cassette selectable in a single copy state in the Bacillus subtilis chromosome. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:4410. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.11.4410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karow M L, Glaser P, Piggot P J. Identification of a gene, spoIIR, that links the activation of ςE to the transcriptional activity of ςF during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2012–2016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karow M L, Piggot P J. Construction of gusA transcriptional fusion vectors for Bacillus subtilis and their utilization for studies of spore formation. Gene. 1995;163:69–74. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00402-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kellner E M, Decatur A, Moran C P., Jr Two-stage regulation of an anti-sigma factor determines developmental fate during bacterial endospore formation. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:913–924. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.461408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.King N, Dreesen O, Stragier P, Pogliano K, Losick R. Septation, dephosphorylation, and the activation of ςF during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1156–1167. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.9.1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroos L, Zhang B, Ichikawa H, Yu Y-T N. Control of ς factor activity during Bacillus subtilis sporulation. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1285–1294. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu J, Cosby W M, Zuber P. Role of Lon and ClpX in the posttranslational regulation of a sigma subunit of RNA polymerase required for cellular differentiation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:415–428. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Londoño-Vallejo J A, Frehel C, Stragier P. spoIIQ, a forespore-expressed gene required for engulfment in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:29–39. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3181680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Londoño-Vallejo J-A, Stragier P. Cell-cell signaling pathway activating a developmental transcription factor in Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 1995;9:503–508. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.4.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lord M, Barilla D, Yudkin M D. Replacement of vegetative ςA by sporulation-specific ςF as a component of the RNA polymerase holoenzyme in sporulating Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2346–2350. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.8.2346-2350.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicholson W L, Setlow P. Sporulation, germination and outgrowth. In: Harwood C R, Cutting S M, editors. Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1990. pp. 391–429. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oliphant A R, Struhl K. The use of random-sequence oligonucleotides for determining consensus sequences. Methods Enzymol. 1987;155:568–582. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)55037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oliphant A R, Struhl K. Defining the consensus sequences of E. coli promoter elements by random selection. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:7673–7683. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.15.7673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Partridge S R, Errington J. The importance of morphological events and intercellular interactions in the regulation of prespore-specific gene expression during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:945–955. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pedersen L B, Ragkousi K, Cammett T J, Melly E, Sekowska A, Schopick E, Murray T, Setlow P. Characterization of ywhE, which encodes a putative high-molecular-weight class A penicillin-binding protein in Bacillus subtilis. Gene. 2000;246:187–196. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00084-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Penn M D, Thireos G, Greer H. Temporal analysis of general control of amino acid biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisae: role of positive regulatory genes in initiation and maintenance of mRNA derepression. Mol Cell Biol. 1984;4:339–348. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.3.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petersohn A, Engelmann S, Setlow P, Hecker M. The katX gene of Bacillus subtilis is under dual control of ςB and ςF. Mol Gen Genet. 2000;262:173–179. doi: 10.1007/s004380051072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piggot P J. Mapping of asporogenous mutations of Bacillus subtilis: a minimum estimate of the number of sporulation operons. J Bacteriol. 1973;114:1241–1253. doi: 10.1128/jb.114.3.1241-1253.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piggot P J, Curtis C A M. Analysis of the regulation of gene expression during Bacillus subtilis sporulation by manipulation of the copy number of spo-lacZ fusions. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:1260–1266. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.3.1260-1266.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piggot P J, Curtis C A M, de Lencastre H. Use of integrational plasmid vectors to demonstrate the polycistronic nature of a transcriptional unit (spoIIA) required for sporulation of Bacillus subtilis. J Gen Microbiol. 1984;130:2123–2136. doi: 10.1099/00221287-130-8-2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schuch R, Piggot P J. The dacF-spoIIA operon of Bacillus subtilis, encoding sigma F, is autoregulated. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4104–4110. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.13.4104-4110.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shimotsu H, Henner D J. Construction of a single-copy integration vector and its use in analysis of regulation of the trp operon of Bacillus subtilis. Gene. 1986;43:85–94. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stragier P, Losick R. Molecular genetics of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Annu Rev Genet. 1996;30:297–341. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun D, Fajardo-Cavazos P, Sussman M D, Tovar-Rojo F, Cabrera-Martinez R M, Setlow P. Effect of chromosome location of Bacillus subtilis forespore genes on their spo gene dependence and transcription by EςF: identification of features of good EςF-dependent promoters. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7867–7874. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.24.7867-7874.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sussman M D, Setlow P. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and regulation of the Bacillus subtilis gpr gene, which codes for the protease that initiates degradation of small, acid-soluble proteins during spore germination. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:291–300. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.1.291-300.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu J J, Piggot P J. Regulation of transcription of Bacillus subtilis spoIIA locus. J Bacteriol. 1990;171:692–698. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.2.692-698.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu L J, Errington J. Identification and characterization of a new prespore-specific regulatory gene, rsfA, of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:418–424. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.2.418-424.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yansura D G, Henner D J. Use of the Escherichia coli lac repressor and operator to control gene expression in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:439–443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.2.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yudkin M D. The sigma-like product of sporulation gene spoIIAC of Bacillus subtilis is toxic to Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;202:55–57. doi: 10.1007/BF00330516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]