Abstract

There has been increased interest and attention to the need for equity, diversity, and inclusion, in the field of applied behavior analysis in recent years. Several publications have focused on these topics and educational curricula and professional development opportunities have been developed. One aspect that has received less attention is how companies providing behavior analytic services can help to promote and sustain a diverse workforce. The purpose of this article is to provide examples and recommendations for how these overarching goals can be addressed. The examples and recommendations are described in the context of a small company that has made important strides in addressing this topic through its mission to serve members of marginalized communities.

Keywords: Applied behavior analysis, Diversity, Service delivery, Workforce

There has been recent and focused attention on issues related to equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) in the field of applied behavior analysis (ABA; Fong & Tanaka, 2013; Fong et al., 2016, 2017). EDI does not have a universal definition but has been used to describe various programs and policies that help to promote the representation and participation of diverse groups (Rosencrance, 2021), including people of different race, ethnicity, belief system, sexual orientation, gender identity, age, parental status, socioeconomic status, military service, and (dis)ability. In this context, equity refers to practices focused on promoting justice and ensuring fair treatment, access, and equal opportunities; whereas inclusion refers to an environment and culture where everyone feels welcomed and respected, and where differences are embraced. A related concept in EDI is cultural competence. Cultural competence can be described as the ability to work with and for diverse cultures (Chin et al., 2016).

It is important to note that EDI and cultural competence are not new concepts to the field of behavior analysis (Fong & Tanaka, 2013; Iwamasa, 1997; Sugai et al., 2012). For example, Iwamasa (1997) highlighted the need to examine culture in the behavioral assessment process and pointed to the need to train behavior therapists to recognize the importance of diversity. Sugai et al. (2012) discussed culture in the context of positive behavioral supports in educational settings. Among the recommendations these authors made for adopting a culturally responsive approach to teaching was training staff on cultural norms, values, behaviors, and customs; and ensuring that membership of the school leadership team represents the cultural groups of the school and community. In their development of standards for cultural competence within the field of ABA, Fong and Tanaka (2013) made a similar call for support and advocacy of a diverse workforce via recruitment, admissions and hiring, and retention efforts. The recommendation to recruit a diverse workforce has continued to be highlighted by other authors since that time (e.g., Beaulieu et al., 2018; Behavioral Health Center of Excellence [BHCOE], 2021b; Conners et al., 2019; Fong et al., 2017; Rosales et al., 2021).

The need to recruit a diverse workforce in the field of ABA has become evident with the publication of demographic data by the Behavior Analyst Certification Board (BACB;, n.d.). These initial reports show little racial and ethnic diversity at all levels of certification with widened disparities for advanced degrees and corresponding certification (e.g., M.S. and Board Certified Behavior Analyst [BCBA]; Ph.D. and Board Certified Behavior Analyst-Doctoral [BCBA-D]). In particular, the data report that only approximately 22% of BCBA and BCBA-D professionals identify as non-white (e.g., a combination of professionals who identify as Black/African American, Hispanic/Latina/o/x, Asian, American Indian/Alaska Native, or Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander).

Benefits and strategies to recruiting a diverse workforce have been outlined and demonstrated in related industries such as nursing (Hinson et al., 2022), family medicine (Jabbarpour & Westfall, 2021), social work (Lewis, 2018), and public health (Ramos et al., 2022). The values of increasing diversity in the workforce have also been described in more general business contexts. For example, according to McCuiston et al. (2004) there are measurable benefits to promoting diversity within the workforce including an improved bottom line (by improving the culture of the organization, helping to recruit new employees, improving relationships with clients, and higher employee retention); an improved relationship with multicultural communities, and employee satisfaction and loyalty. Two decades ago, Cohen et al. (2002) made a case for increasing diversity in the healthcare workforce. The field of behavior analysis has a strong presence in the health-care industry because the provision of ABA services for individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are reimbursed by insurance companies and behavior technicians were deemed “essential healthcare workers” in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Like the views presented by Cohen et al., increased diversity within the behavior analytic service workforce is an essential component for the provision of culturally competent care to marginalized communities. That is, diversity in the workforce can help to expand access to ABA services in underserved populations, inspire research with populations that have been neglected in behavioral research (Iwamasa & Smith, 1996), and increase the pool of available clinical supervisors and academics to help meet the needs of diverse supervisees and students in the field.

Although the need to increase diversity in the workforce has been described for several years, there were no published resources in the field of behavior analysis on this topic until recently (BHCOE, 2021b). The EDI standards outlined by the BHCOE are presented briefly in Table 1. It should be noted that one of these standards is related to diversifying the workforce with a recommendation that companies recruit a workforce that is representative of the community that it serves, and one that is representative of the recipients of said services (BHCOE, 2021b).

Table 1.

Behavioral health center of excellence EDI standards for ABA organizations

| 1. | Organization has a diversity statement that expresses ongoing commitment to an inclusive and equitable organizational culture, protecting and supporting staff and clients, and ensuring EDI. |

| 2. | Organization communicates availability of translation services; has access to and utilizes translation services for oral and written communication as needed. |

| 3. | *Organization is committed to and has a process for evaluating marketing, training, and therapeutic materials that ensure representation of diverse individuals. |

| 4. | *Organization makes closed captioning available on all video content. |

| 5. | Organization provides mandatory cultural humility and diversity training and competency checks to all staff upon hire, annually, and as required by state and federal guidelines. |

| 6. | *Organization is committed to and has a process for evaluating talent acquisition efforts to ensure a diverse candidate slate. |

| 7. | Organization engages in fair hiring and employment practices. |

| 8. | Organization engages in annual self-assessment of diversity efforts. |

| 9. | Organization’s physical location is compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act. |

| 10. | *Organization makes a good faith effort to provide services to qualified underserved populations. |

| 11. | Organization ensures leadership and supervisory staff complete conflict resolution training that provides a process for responding to bias incidents. |

*Items are not applied to companies that serve fewer than 25 clients

To date, we know of no publications outlining strategies or examples of how recommendations to recruit a diverse workforce can be implemented in practice. Therefore, the purpose of this article is to outline and highlight recommendations for small ABA businesses to actively recruit and retain a diverse workforce. Many of these recommendations align with the BHCOE’s recently published standards (BHCOE, 2021b), but it is important to note that the recommendations described were implemented at the small company of the second and third authors to varying degrees from the time the business was founded in 2012. We provide a brief background of the company and 10 recommendations for focusing on recruiting a diverse workforce. Each recommendation outlines the suggested actions and considerations and then describes how those actions were implemented in the company. In some recommendation application sections we include related data from the company.

Brief Background of the Company

The company was established in direct response to a pressing need to provide behavior analytic services to families living in an urban region of the state that is home to a large immigrant population. When the company was established, the founder, the second, and third authors all resided in the same geographic region as the target population, and actively participated in local community and social events. This helped to facilitate community relations and outreach from the outset. The geographic location of the company was purposely selected in an area that was accessible by public transportation to meet the needs of the community (because many families living in this region do not own a personal vehicle); and the administrative team made efforts to recruit direct care therapists and office staff who were representative of the community being served. In this way, the company was a leader in the state for grassroots outreach to marginalized communities and recruitment of a diverse workforce. The actionable steps described in this manuscript were developed and implemented without a specific guiding resource, such as the recent BHCOE standards. The efforts were informed by and included personal interactions, connections, and informal networking within the community.

Recommendations for Recruiting and Retaining a Diverse Workforce

The following section outlines specific recommendations for recruiting and retaining a diverse workforce followed by examples of how the company implemented each of the recommendations to date. In Table 2, the recommendations are outlined along with additional resources and references with the goal of providing other companies with tools to attract, hire, retain, promote, and celebrate diversity within the workforce.

Table 2.

Recommendations and resources for recruiting and retaining a diverse workforce

| Recommendation | Strategies & Implications | Resources & References |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Include an equal opportunity statement |

-Include administrative staff in drafting of statement -Sends a message to staff that diversity is valued -Sends a message to candidates about the organization’s values |

U.S. Department of Labor: https://www.tinyurl.com/4w9xtdff Examples of EOE statements: https://www.tinyurl.com/3yzzh8y7 |

| 2. Promote diversity in marketing |

-Include diverse images in online presence -Promote and help to support diverse community events on social media platforms -Candidates see themselves in the company’s advertising -Current employees feel valued and included |

McKay et al. (2007) http://www.tinyurl.com/2dkjabv3 Websites for Diverse Images: https://www.diversityphotos.com/ https://www.genderphotos.vice.com/ https://www.blackillustrations.com/ Resource for Client Materials: |

| 3. Use creative recruitment strategies |

-Post job ads on nontraditional sites and in the community -Ask current employees to serve as a referral source -Provide employees with incentives for recruiting within their own networks -Create a high school internship program -Diverse candidates may not access traditional employment sites -Organization’s name becomes recognized within the community |

OutPro (Professional Diversity Network): https://www.outpronet.com/ PinkJobs (LGBT+ Friendly Job Site): https://www.pink-jobs.co Autism Employment Network: https://www.tinyurl.com/2thvezkx Burks et al. (2013): https://www.tinyurl.com/2p8ym98y Mani (2012): https://www.tinyurl.com/2cjksn34 Toolkit: Designing and Managing Successful Employee Referral Programs: http://www.tinyurl.com/3hzere9j 7 Steps to Creating Internship Program (U.S. Chamber of Commerce): http://www.tinyurl.com/3pkdasua Handshake (College Recruitment): https://www.joinhandshake.com/ Leverage Community Outreach: https://www.tinyurl.com/3ws8c42r |

| 4. Broaden requirements and qualifications |

-Formalize interview process -Use readily available tools to blind resumes -Avoid over-screening (bias in review) of potential candidates |

Reduce Bias in Screening: https://www.tinyurl.com/2pxmbkv3 Fu (2020) on Indeed Assessments: https://www.tinyurl.com/jeknmf4r Kang et al. (2016): https://www.tinyurl.com/4xfbj6dv |

| 5. Evaluate consumer and staff demographics |

-Collect data during client intake -Collect data as part of hiring onboarding process -Company objectively evaluates disparities in clients served and employees -Company self-evaluates and modifies recruitment and hiring efforts as needed |

BHCOE (2021b): https://www.tinyurl.com/2p8jtuxb Hasnain-Wynia and Baker (2006): https://www.tinyurl.com/2p8sakbb |

| 6. Provide equitable and fair pay |

-Offer a fair living wage -Use compensation grids -Attract more qualified candidates -Increased employee retention and satisfaction |

Living Wage Calculator: https://www.tinyurl.com/5xyyrdxz Information on Compensation Grids: https://www.tinyurl.com/h28nmmwf Payscale for BCBAs®: https://www.tinyurl.com/2p92wpaf Tucker (2021): https://tinyurl.com/29f74ysk |

| 7. Build community among staff |

-Enhance interpersonal communication and interactions among staff -Formalize training approaches that embed self-care -Increased employee satisfaction -Improved employee retention |

Perlow and Kelly (2014): https://www.tinyurl.com/29bacss3 Slowiak and DeLongchamp (2021): https://www.tinyurl.com/3hxe3ezc |

| 8. Implement policies and practices that support staff and embrace diversity |

-Avoid unnecessary policies in the workplace -Recruit input and formal written feedback -Creates an inclusive culture within the organization -May lead to improved retention |

Babcock (2009): https://www.tinyurl.com/58nypc4c EEOC Enforcement Guidance on National Origin Discrimination |

| 9. Assess staff satisfaction and levels of stress |

-Recruit formal feedback at regular intervals -Company evaluates how they are meeting needs of their employees and/or areas for improvement -Improved job satisfaction, improved retention |

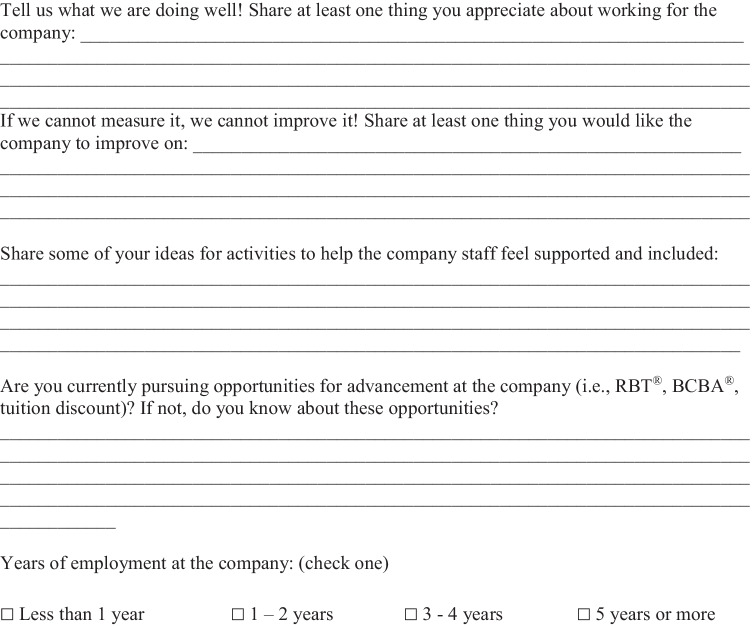

Pittenger et al. (2014); https://www.tinyurl.com/2p9cjw6x Tools to Assess Burnout Kristensen et al. (2007): https://www.tinyurl.com/msrta862 see Appendix 1 for a sample Social Validity Survey for Staff |

| 10. Provide mentorship |

-Identify talented candidates for graduate programs -Encourage prospective candidates to apply to graduate programs or pursue other credentials -Helps strengthen existing partnerships or establish new partnerships with area colleges and universities |

Holloway (2001): https://www.tinyurl.com/38apdrvf Clark et al. (2012): https://www.tinyurl.com/3mjwyn37 Brunsma et al. (2017): https://tinyurl.com/523wj5wp |

Recommendation 1: Equal Opportunity Employer (EOE) Statement

Organizations are not legally required to include an equal opportunity employer (EOE) statement in their job postings, except for federal contractors (Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs, n.d.). However, an EOE statement may be used as a discriminative stimulus to signal to applicants that diverse candidates are welcome. Including such a statement has been shown to reduce instances of “résumé whitening,” a term to describe when applicants conceal racial markers from their job applications (Kang et al., 2016). An EOE statement is described as a short paragraph that conveys a business's commitment to EDI in its employment practices.

Including an EOE statement in job postings may seem commonplace given the legal protections against discrimination in the workplace. To assess this, we conducted an informal search for positions using the keyword “ABA therapist” and limited the search to open positions in the author’s home state using a popular search engine. We found that only 317 of the 1,466 jobs posted (22%) included an EOE statement (search conducted on July 10, 2021). The minimum requirement for inclusion was that the job made any mention of an EOE statement (e.g., “[Name of the company] is an equal opportunity employer”). However, it is important to highlight that there was variability in how the EOE statements were phrased, ranging from a simple phrase (e.g., “[Name of company] is an Equal Opportunity Employer”) to a full paragraph listing the protected groups to whom the company commits to nondiscrimination and harassment. The evidence to date on the impact of EO statements is limited (Flory et al., 2019), but at least one previous study reported that participants rated the attractiveness of a company higher when a job advertisement included an extensive EOE statement compared to no statement or a minimal statement (McNab & Johnston, 2002). In considering implementing an EOE statement in job postings, it need not be lengthy. However, there may be value in working collaboratively to draft the statement as an administrative team to highlight the company’s values to promote diversity in the workforce among current team members (see Table 2 for a resource that gives examples of various EOE statements).

Application of Recommendation 1

To apply this first recommendation, the company includes a full EOE statement in all job postings. The company’s leaders drafted the EOE statement to align with the company’s values to signal to applicants that diversity was welcome. This statement was reviewed and approved by the company’s chief human resource officer before dissemination. In particular, the statement reads:

[Company name] is an Equal Opportunity employer of qualified individuals and does not discriminate based on race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, disability, veteran status, or any other basis protected by applicable federal, state, or local law. [Name of company] also prohibits harassment of applicants or employees based on any of the protected categories.

Recommendation 2: Promote Diversity in Marketing

Organizations are not required to include diverse images in their marketing, but a candidates’ perceptions of an organization can be influenced by the lack of diversity represented in the company’s online presence. Diversifying marketing materials has also been shown to influence employees’ decision to remain at a company (McKay et al., 2007). ABA companies seeking to attract a diverse workforce should conduct a thorough review of all visual marketing materials (e.g., pictures on websites and fliers, videos, logos, and materials created for client use) and maintain a committed practice of ensuring that visuals used align with the company’s values and mission to EDI.

Examples of diverse marketing can also include actions such as promoting a local BIPOC event taking place in one’s community on the company’s social media page or email-newsletter, and incorporating children’s books, games, toys, and visuals (e.g., for functional communication or schedules) that represent characters or individuals of marginalized groups (see Table 2 for links to resources). The company’s website should reflect its mission including a diversity and equity statement, and this information can be included in professional presentations delivered at conferences and/or in the community. Like the recommendation to include an EOE statement in job postings, the present recommendation should be considered a starting point to signal to potential candidates and consumers that the organization values diversity.

Application of Recommendation 2

To apply this recommendation, all photos used for marketing are selected in an intentional and considerate way to visually promote the company’s commitment to representation and inclusion. Stock images are used in marketing material to ensure confidentiality. The staff responsible for selecting images purposefully identify visuals that represent various races, ethnicities, faiths, ages, gender identification, and physical abilities. The company aims to use images that highlight groups of people with different identities to avoid creating harmful stereotypes or associations (e.g., children of mixed genders shown playing an activity typically associated with one gender, or a photo of an older adult pursuing continuing education with students of various ages). In addition, the books and toys available for use during therapy sessions are representative of a diverse population (e.g., dolls of different racial identities and books in multiple languages).

Recommendation 3: Use Creative Recruitment Strategies

To recruit a diverse workforce, companies need to take meaningful steps during and after the hiring process to attract and retain employees from underrepresented groups (Dixon, 2020). The platform(s) used for the placement of job ads will affect the type of applicant a company will attract. For example, popular job search engines (e.g., Monster.com, Indeed.com) and professional social media pages (e.g., LinkedIn) are commonplace for potential employees, but may not always lead to a diverse applicant pool. Companies can take simple steps by posting ads on job websites aimed specifically at candidates from underrepresented groups (e.g., OutProNet, PinkJobs, Autism Employment Network, Recruit Disability, TJobBank), posting in the community (e.g., community college campuses, adult education centers, local churches), asking current employees to spread the word in their own circles (Mani, 2012), and making a commitment to community outreach in order to increase the visibility of the company.

Companies can also form strategic partnerships with local high schools, community colleges, and universities. For example, companies who affiliate with high schools can offer volunteer and internship opportunities to junior and seniors who may be interested in working with children or adults with ASD and related disabilities, but who are unfamiliar with the field of behavior analysis as a career path. It is important to note that outreach to high school students in diverse communities can create a pipeline of highly qualified employees and applicants for undergraduate and graduate training programs in behavior analysis. Affiliations with college and university programs may also be arranged with tuition discounts to employees to encourage pursuit of advanced degrees in behavior analysis. This strategy could be enhanced by targeted outreach to community colleges, Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), Hispanic Serving Institutions (HSIs), and Asian American and Native American Pacific Islander-Serving Institutions (AANAPISIs), where there are larger representations of BIPOC students. The affiliation with university programs may be an option that is readily available given the current focus on EDI initiatives within the field. That is, colleges and universities with ABA training programs may be looking to partner with companies applying this lens to their recruitment.

Finally, employee incentive programs can be easily adopted, but may not always be successful to promote diversity within the workforce. Care should be taken to avoid overburdening employees of diverse backgrounds especially if there is little diversity of which to speak. Also, if referrals are solicited from current employees, companies should ensure the job description is accurate when described to prospective employees (Marin, 2012) and continue to screen, interview, and thoroughly vet all job candidates (Pieper et al., 2018).

Application of Recommendation 3

From the time the company was founded, nontraditional recruitment methods were intentionally implemented. For example, the founder posted flyers in the community (e.g., community colleges, adult education centers, local churches) and personally distributed information about the company to members of the community at local events and during personal outings (e.g., a trip to the local beauty salon). These strategies resulted in the hiring of a racially and ethnically diverse workforce that was representative of the community it served.

Other initiatives include an incentive program for current employees to spread the word about current postings among their own professional and personal networks. These internal referrals have been maximized by offering incentives to employees who recommend highly qualified candidates who remain at the company for at least 3 months. The employee referral program began in 2018 when employees asked if they could refer people that they knew who would “make great therapists.” This allowed the company to take the cost per applicant from the online recruitment site and pay it instead to current staff as a referral bonus. Employee referral schemes such as this tend to be viewed positively by employees (Burks et al., 2013; Mani, 2012).

The company is in the beginning phases of establishing an internship program for local high school students, and recently signed a corporate partnership agreement with a local university that attracts a large population of racially and ethnically diverse students with almost half of the population identifying as first-generation college students. This partnership will afford students the opportunity to receive a tuition discount for attending a master’s program in ABA while working for the company as a behavior technician. Finally, the company has a strong commitment to community outreach that has included presenting to stakeholders (e.g., state insurance providers, local hospitals that serve a large population of immigrants), and interviews on Spanish language radio stations. These efforts can help disseminate ABA to historically marginalized communities and increase referrals for services and employment (via word-of-mouth).

Recommendation 4: Broaden Requirements and Qualifications (Avoid Overscreening Potential Candidates)

ABA companies interested in diversifying their workforce may opt to begin by reviewing the recommendation to avoid over screening potential candidates. Overscreening of candidates can come in many forms but may include bias in review of resumes (Kang et al., 2016), evaluation of prior experiences in the field, and professionalism during an interview. Regarding bias of resumes, prior research has demonstrated that candidates may “whiten” their resumes by altering information that indicates their ethnicity. Unfortunately, this does not always lead to an increased likelihood of a call back from a potential employer (Kang et al., 2016). When evaluating prior experiences in the field, an applicant should not be screened out simply based on a lack of formal work experience interacting with children or individuals with disabilities. The applicant should be considered if they have related experience, such as caring for an extended family member with a disability, or if they themselves are members of the neurodiverse community. Regarding professionalism, employers should be sensitive to differences in how professionalism is exemplified in diverse cultures including attire, hairstyles, use of accessories and make-up, and disparities for members of communities that may lack familiarity with white American business or professional attire (or adequate access to this attire). Another consideration is that some diverse individuals may not have had access to experience or mentorship related to professionalism during a job interview.

Employers can take measures to avoid bias in review of application materials by conducting a blind review (e.g., remove names that are often racial and gender indicators; Bortz, 2018) and ensuring all applicants are processed using the same steps and activities. The process of a blind review for applications is an important (albeit potentially laborious) step for companies to take given the documented evidence of implicit bias in the review of applications (Bertrand & Mullainathan, 2004). As an alternative, companies can make use of the “Assessment Test” feature in Indeed.com to help reduce bias and create a more consistent recruitment process (Condon, 2018). This is a free tool that allows employers to add skills tests to postings to screen candidates based on their abilities and aptitudes for a particular role (e.g., reliability, diligence, customer focus and orientation). Employers can opt to require completion of this assessment tool as part of the application process (Fu, 2020). Finally, employers should take care in using standard interview questions that are asked to all candidates in a consistent manner.

Application of Recommendation 4

The previously outlined considerations are considered at every stage of the recruitment process at the company. The company takes careful steps when using the Indeed site to control for potential bias in review of resumes. This includes the following steps: (1) open up all applicants that meet requirements, such as location, minimum degree, and credential (these can be filtered); (2) assign a number or code to each applicant; (3) open each applicant profile and immediately scroll down to Assessment Results; (4) document the applicant number and assessment results of each applicant on a spreadsheet; (5) select highest scores on the assessments (criteria for selection varies and depend on the hiring need); and (6) add the selected applicants’ name, resume, and contact information to the final list of job candidates to schedule for an initial interview.

Following review of resumes, a considerate amount of care goes into ensuring the same steps are followed in the hiring process for every potential hire: first a phone screening is scheduled, followed by a virtual interview, and, finally, an in-person interview. Omitting any of the steps may give an applicant an unfair advantage. The interviewers at the company are trained to ask the same set of questions to each applicant applying to a position. The preplanned questions are relevant to traits or skills needed for success on the job, and any questions that infer information that may lead to bias such as ageism (i.e., “What year did you graduate?”), sexism (“Do you have children?”), and other potential discriminatory biases are strictly avoided. Each applicant’s interview performance is measured by the extent to which their answers align with experience, knowledge, and skills needed for the job.

Recommendation 5: Evaluate Consumer and Staff Demographics

Companies are encouraged to begin an initial assessment of client and staff demographics to determine if employees reflect the population being served (BHCOE, 2021b). Hasnain-Wynia and Baker (2006) provide a strong rationale for why health-care organizations should collect race, ethnicity, and language data directly from consumers; namely, that doing so will make it more likely that the organization will evaluate disparities in care and design programs to improve quality of care to historically marginalized populations. Demographic data should include multiselect boxes with options to skip questions employees are not comfortable responding to. This step is particularly important if staff completes the forms online (e.g., the form should allow employees to complete the form even if they choose to skip some of the questions). The demographic questionnaire options should also include an option to write-in responses to allow respondents to self-describe. Employers explain the purpose of collecting the information and a privacy policy regarding the information that will be shared. In addition, the form should be ADA compliant by increasing font size and augmenting visual images as needed, making documents available in both electronic and paper formats, have options to complete forms orally (e.g., someone reads the question and writes down a response on behalf of the applicant or employee), and having access to qualified interpreters for individuals with hearing impairments (Americans with Disabilities Act, 1990).

Application of Recommendation 5

As noted in the background section, the company was founded with a mission to serve immigrant communities in a geographic region of the state where ABA clinical services were not being provided. The administrators collected demographic data from consumers through an intake report. During the intake caregivers were asked to provide demographic information on a written form and interviewed to ask follow-up questions. Caregivers were given the option to skip any questions they did not feel comfortable responding to at the time of the intake and were informed that their personal information would not be disclosed (e.g., names). Staff demographic data were collected via employee files completed as part of the hiring process.

The data collected from families and staff are summarized and presented in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. Table 3 shows that 90.62% (n = 58) of families reported identified as BIPOC (e.g., Hispanic/Latino/a/x, Black or African American, Asian, Native American, American Native, or Indigenous, or of Mixed Race). In addition, 89.1% (n = 57) of the families reported that their dominant language was not English (76.56%; n = 49 of caregivers reported Spanish as their home language). Table 4 shows that 70.27% (n = 26) of staff reported that they identified as BIPOC, and 79.84% (n = 29) of staff reported speaking two or more languages fluently. These data reflect a close “match” in consumer and staff demographics in terms of race and ethnicity.

Table 3.

Client demographics (N = 64)

| Race | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Black or African American | 11 (17.19%) |

| White | 6 (9.3%) |

| Asian | 1 (1.5%) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0 (0%) |

| Native American, American Native, or Indigenous | 5 (7.8%) |

| Two or More Races/Mixed Race, or Mestizo | 41 (64.06%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic or Latino/a/x | 50 (78.13%) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino/a/x | 14 (21.88%) |

| Home Language (if not English) | |

| Cape Verdean | 1 (1.56%) |

| Haitian Creole | 1 (1.56%) |

| English | 7 (10.93%) |

| Portuguese | 4 (6.25%) |

| Somali | 2 (3.13%) |

| Spanish | 49 (76.56%) |

Table 4.

Staff demographics (N = 37)

| Race | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Black or African American | 14 (37.84%) |

| White | 11 (29.73%) |

| Asian | 2 (5.41%) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0 (0%) |

| Native American, American Native, or Indigenous | 1 (2.70%) |

| Two or More Races/Mixed Race, or Mestizo | 9 (24.32%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic or Latino/a/x | 16 (43.32%) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino/a/x | 21 (56.76%) |

| Languages Spoken (other than English) | |

| Albanian | *1 (2.70%) |

| French | *3 (8.11%) |

| Greek | *1 (2.70%) |

| Spanish | 19 (51.35%) |

| Haitian Creole | *8 (21.62%) |

| Cape-Verdean Creole | *1 (2.70%) |

| Portuguese | *3 (8.11%) |

| Arabic | 1 (2.70%) |

| Hindi | 1 (2.70%) |

| Italian | *1 (2.70%) |

| Yoruba | 1 (2.70%) |

*The total for these languages reflects employees who are multilingual.

Although these initial data focused on race, ethnicity, and home language, the company plans to gather additional information on other variables related to diversity including gender identification, (dis)ability, veteran status, and religious affiliation. This will help apply a much-needed lens to the various forms of diversity needed within the workforce.

Recommendation 6: Provide Equitable and Fair Pay

Companies must ensure that compensation takes into consideration the living wage standards of individuals from the community. According to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in Cambridge, Massachusetts (Glasmeier, 2021), a living wage is defined as market-based approach that draws upon geographically specific expenditure data related to a family’s minimum food, childcare, health insurance, housing, transportation, and other necessities (e.g., clothing, personal care items). Compensation below what is considered a living wage in any given geographic region is likely to result in a less diverse pool of eligible candidates. That is, offering wages that are below the living wage may limit opportunities for candidates who lack family support (e.g., single parent households, individuals with a disability). Offering part-time and full-time opportunities with benefits is also likely to attract a diverse pool of applicants. Previous research has demonstrated inequities in pay for behavior analysts working in academic settings (Li et al., 2019) and in clinical settings with data showing that female minority groups are affected the most by pay inequities (Vance & Saini, 2022). The practice of asking about previous salary may contribute to systemic inequality, as women, people of color, and individuals with disabilities are typically paid less for equal or similar work (Tucker, 2021). ABA companies can begin to adopt practices within their own hiring to provide equitable and fair pay to employees at all levels. It is important to note that given the increasing demand of behavior technicians and BCBAs in the last 2 decades (Behavior Analyst Certification Board, 2021), compensation rates can vary widely depending on the geographic region (PayScale, 2022).

Application of Recommendation 6

At the company, interviewers avoid asking candidates about salaries from previous employment to prevent using this as a basis for the initial salary offer. Instead, the company created a formal pay range structure formatted into a grid to use as a simple and objective reference tool (Culpepper & Associates, 2010) to allocate an equitable salary. The grid designates salary or hourly wage ranges by categories: highest degree earned, highest certification level, and relevant experience (less than or more than 1 year). Each employee is compensated within the range provided until they move to a higher range by earning a degree, certification, or gaining additional years of experience at the company. Part of the interview process is to explicitly ask candidates about their preferred hours and attempt to accommodate flexible schedules. This helps to ensure that candidates in different situations (e.g., working parents, those working two jobs) are provided equal opportunities for employment.

Recommendation 7: Build Community among Staff

Supporting staff and building community among employees is critical to improve turnover rates and may be particularly important for BIPOC employees and members of other marginalized groups. There is ample research suggesting that creating a sense of community among workers enhances the perception of the company culture (Perlow & Kelly, 2014). Perlow and Kelly describe various models of flexible work accommodations that can help employees manage work and life demands. For example, the concept of predictability, teaming, and open communication include employees having planned uninterrupted time off. Arranging time for employees to enjoy one another’s company outside of the work setting can facilitate culture building and encourage discussion about what is and what is not working for them. Strategies to build community can include opportunities for collaborative problem-solving during work. This can be accomplished by creating space and time for employees who work with the same client(s) to brainstorm solutions on challenging cases. Regular meetings times should be scheduled for team members to discuss their clients and bounce ideas off each other as well as celebrate successes.

Companies should also encourage, model, and support self-care practices. Recent data from the field of ABA shows that when individuals can engage in self-care strategies and take initiative-taking steps to improve aspects of their job (i.e., job crafting), they are more likely to see improvements in work-life balance, work engagement, and symptoms of burnout (Slowiak & DeLongchamp, 2021). Given that professionals providing services to individuals with ASD are at considerable risk of experiencing high job-related stress (i.e., burnout; Bottini et al., 2020) which may contribute to high turnover rates (Plantiveau et al., 2018), it is incumbent on the employer to implement policies and practices to mitigate levels of stress that can lead to burnout. For example, employers should evaluate policies related to paid time off, paid sick time, caseloads, manageable work hours, and reduce ancillary work that can be delegated to a separate position.

ABA companies interested in taking steps to support and build community among staff can follow the recommendation to incorporate brief moments for staff to share something about their identity as part of ongoing training and/or meetings. This can alleviate the need to create additional company events if there is a strain for time and need to prioritize clinically relevant initiatives. Celebrating milestones (e.g., work anniversaries) can be done monthly (e.g., announced during a company-wide meeting or training) or broadcasted on social media with the staff member’s permission.

Application of Recommendation 7

Community is a core value of the company. First, staff are encouraged to learn about one another’s personal identity and culture by routinely asking staff to talk about and share aspects of their own culture during meetings (as icebreakers) to learn from one another and celebrate differences. For example, staff are invited (but not required) to share information about their interests (hobbies), traditions, holidays celebrated, meals prepared, and languages spoken. It is important to note here that a diverse workforce may lead to an inadvertent increase in microaggressions in the workplace. Microaggressions are defined as “brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults toward persons of color” (Sue et al., 2007, p. 271). When microaggressions occur in the workplace they must be addressed. Sue et al. (2019) provides several recommendations to this effect. For example, these authors suggest to “make the invisible visible” (e.g., by educating the offender), and to seek external support (e.g., by reaching out to colleagues who can provide emotional support and brainstorm ideas to address and/or educate the offender). In the company, regular sharing of one’s personal identity and interests may serve as an antecedent strategy to deter microaggressions and/or to teach bystanders to become allies by interrupting and addressing instances of microaggressions when they occur.

A second way the company builds community is by hosting a variety of social events to provide staff with an opportunity to come together outside of the work context. Social events are sometimes planned immediately following required training events or are embedded into the training day (e.g., a barbeque hosted by the company as part of the lunch hour for full-day training). Significant others and children are invited to attend events scheduled outside of work to include employees who would otherwise be unable to participate. Staff are provided with an opportunity to select and help facilitate social events. For example, the company created connections in the community that have resulted in opportunities for staff to gain additional benefits such as tickets to a baseball game or museum. In addition, employee life (e.g., birthdays, family additions, loss of family members) and career milestones (e.g., pursuing a master’s degree, completing a bachelor’s degree or additional credentials) are recognized and celebrated. It is important to note that these celebrations need not be costly or draw attention to the employee in a group setting. For example, something as simple as a handwritten or signed congratulatory or thank you note to employees to celebrate an important milestone can boost morale. Engaging in these small acts may result in employees feeling connected and appreciated by the employer.

Third, all staff have ample opportunity to communicate with their colleagues about the cases they are working on; to propose solutions to challenges; and celebrate client outcomes via regularly scheduled meetings. Staff are encouraged and reminded to share their perspectives with their colleagues and supervisors. In this way, the company administrators encourage open communication.

Fourth, in an effort to mitigate levels of stress and reduce ancillary work, clinical supervisors and direct care are advised to direct clients to the family liaison (a position created to help make a strong connection with families and provide much needed initial rapport building to build trust) for all nonclinical issues (e.g., if families need assistance completing school forms, have questions regarding access to other community resources, need assistance translating a document, or need help scheduling their child’s services). Although these issues may affect the quality of ABA services if left unresolved, it is important for staff to have clear direction on how to set boundaries to alleviate potential conflicts of interest and reduce nonclinical work duties.

Finally, all employees are provided with ample sick time, and employees working 30 or more hours per week are offered generous paid time off and competitive medical, dental, and vision insurance coverage. Information about the benefits of paid time off is communicated to families as part of the intake process to alleviate concerns about the need to switch therapists from time to time, especially when there is a good match between client and therapist and/or supervisor. The open communication encouraged for all employees facilitates saying “no” to requests to add another client to their caseload or to request additional time as needed.

Recommendation 8: Create Policies and Practices to Support Staff and Embrace Diversity

Companies typically communicate employee policies in the form of handbooks, orientations, training materials, and other similar mediums. It is important to continuously monitor and reevaluate these policies in the context of the impact they have on an organization’s culture. For example, company dress codes can sometimes be overly stringent for home- or community-based work, given that formal attire is not needed for the work to be performed successfully (e.g., not allowing tattoos to be visible, certain hairstyles, or accessories). Strict and unnecessary dress code policies may potentially constrain employees’ expression of cultural or racial identity, ethnic background, faith, or other aspects of individuality (Babcock, 2009). Likewise, employees who originate from a different country and/or whose first language is not English may speak with an accent. In many cases, direct staff are modeling language and verbal behavior skills to children with language delays, so fluency in the target language is understandably to be expected for the job. However, it is important to note that hiring and employment decisions based on a person’s accent are only allowed in cases where the accent impedes the employee’s ability to do their job (U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 2016). Employers should carefully evaluate and determine if speaking in a standard American accent is truly a requirement for teaching verbal behavior to a client, especially if the employee with an accent is able to pronounce target sounds correctly and is understood by other English speakers. This same logic should also be extended to employees who speak in other dialects of American English. Policies around avoiding slang or “informal” speech may inadvertently create a company culture that is biased for standard English and less tolerant of nonstandard dialects of English (i.e., African American vernacular English, Chicano English, Cajun English). Even when exemptions are allowed, overly stringent policies risk alienating employees, which may also hinder the development of an inclusive workplace culture. If policies are not required by law, it is essential to train supervisors on the goals of each company policy so they can be in a better position to address questions and/or challenges posed by employees (Babcock, 2009).

There are a variety of ways ABA companies can adopt policies and practices to embrace diversity and improve job satisfaction among practitioners. To start, companies should evaluate their current policies on dress code and how “professional” behavior and appearance is defined and viewed within the company. A shift in focus on employees’ work ethic, passion, initiative, and responsiveness to feedback should be underscored.

Application of Recommendation 8

At the company, communication about company policies is provided during the onboarding process, via an employee handbook, and in training materials. For example, the company’s dress code is focused primarily on safety and based on recommendations from the safety training curriculum adopted by the company (i.e., clothing and shoes must not restrict movement, accessories may not hang from the body, and long hair must be tied back). If needed, more specific recommendations around attire are discussed with the therapist when more information is known about the client’s triggers and/or the family’s customs and preferences at home. Both employees and clients are encouraged to accept and appreciate the diversity in accents and dialects within the company. In many cases, the use of idioms, expressions, and slang can only be beneficial to a learner when incorporated as teaching opportunities for naturalistic speech. Likewise, exposing a learner to different accents effectively teaches them variations of the same stimulus class of sounds. Clear guidelines are provided and respected on working hours, timely communication from employers, and communication about policies to staff and families alike. The company’s core hours of operation are regularly communicated to staff and families. Barring exceptional circumstances, all therapy sessions and work-related communications must take place within these core hours to promote a culture of respect for the staff’s personal time. After these hours, staff are advised to leave the work site (therapy clinic or client’s home) to ensure they spend sufficient quality time outside of work.

Recommendation 9: Assess Staff Satisfaction and Levels of Stress

Seeking regular input from employees is one way companies can evaluate how they are (or are not) meeting the needs of their workforce and employees’ overall levels of satisfaction (e.g., feeling valued and supported). One strategy to evaluate employee satisfaction is to recruit formal feedback at regular intervals. Previous research on this topic has demonstrated that when employers ask for staff input this leads to increased job satisfaction and lower levels of job-related stress (Gray-Stanley et al., 2010). Companies can recruit feedback on a quarterly basis via social validity assessments to align with employee performance reviews. Pittenger et al. (2014) evaluated a social validity assessment with educational service practitioners to get input on their levels of satisfaction and acceptance of available resources, support, and responsibilities at a specialized school for children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Results helped to inform recommendations for improvements and revealed positive staff perceptions.

There are also a variety of standardized assessments that could be used by employers to assess levels of stress experienced by employees (see Kristensen et al., 2007; Malach-Pines, 2005). Once levels of stress are assessed, formal practices to support staff can also be embedded into training. For example, Little et al. (2020) evaluated the addition of acceptance and commitment training (ACT) on the enhanced effectiveness of behavioral skills training for staff working in an autism clinic. The ACT component of the training included exercises commonly reported in the literature (e.g., present moment attention, values identification, and committed action). Results of this study showed that the addition of ACT was effective in enhancing the performance of staff in the training procedure learned via participation in the study.

Recruiting input from staff collaborating directly with clients (i.e., behavior technicians) may help them feel valued in their job. Finally, because staff experience varying levels of comfort in providing direct feedback to employers, companies are encouraged to recruit anonymous feedback on a regular basis.

Application of Recommendation 9

The company is working to formally recruit feedback from all staff using a staff satisfaction survey that was recently developed for this purpose (see Appendix 1). Other processes to recruit staff input have been in place for many years. For example, clinical supervisors schedule regular meetings with the behavior therapists to get input on client behaviors of concerns and skill deficits. Clinical quality assurance reviews are conducted on a quarterly basis whereby two independent BCBAs review client progress via data analysis and direct observations and have follow-up meetings to discuss the clinical recommendations and potential treatment modifications with the help and support of the behavior technicians on each case.

The company has also evaluated staff preferences in a formal manner and there are plans to assess staff preference to identify reinforcers (Wine et al., 2014) and feedback delivery (Reid & Parsons, 1996). As one indicator of the impact of the activities the company has implemented to date, there are low employee turnover rates for direct care staff (i.e., 20% annual turnover for direct-care staff in 2020). This low turnover is promising given a recent report estimating an annual turnover as high as 59%+ for direct-care staff in 2020 (BHCOE, 2021a).

Recommendation 10: Provide Mentorship

Acquiring a diverse team of BCBAs may present a unique challenge. According to the BACB certificant data, less than 10% BCBA-D, BCBA, and board certified assistant behavior analyst (BCaBA) respondents identified as Hispanic/Latino/a/x, and only 3.6% of respondents identified as Black/African American (BACB, n.d.). Given this data, business owners may ask, “How do I attract and retain a diverse team of BCBAs when there is already a shortage of BCBAs?” An organization may find that, despite their best efforts in diverse recruiting, they are nevertheless unable to find diverse candidates to fill the BCBA roles. In this case, the company may opt to instead focus on growing and retaining a diverse body of direct care staff, followed by training, certification, and development with the aim of advancing into supervisory roles. Over time, diversity may be reflected in the leadership of the organization but getting to this point will require administrative staff providing opportunities and mentorship to staff. Previous research in related fields has shown that training that is supplemented with high-quality mentorship leads to improved retention (Hagaman & Casey, 2018; Holloway, 2001). In the context of graduate training programs, previous studies have shown that mentoring plays a crucial role in retaining BIPOC graduate students (Clark et al., 2012); yet these students have often identified that a lack of mentoring is one way in which their experience differed from their White counterparts (Brunsma et al., 2017).

ABA companies are encouraged to develop a mentor or apprenticeship (Hartley et al., 2016) model that can include staff at all levels rather than focusing solely on graduate students already enrolled in a master’s program or verified course sequence (VCS) by the Association for Behavior Analysis International. Employees may need targeted mentoring with encouragement and support to apply to graduate programs. Students/employees, even when they have the knowledge about career pathways, still do not see the next step as being something they can do or be eligible for. If employees do not see themselves in the administrative/clinical admin staff, this may also affect their motivation to pursue advanced degrees.

Application of Recommendation 10

At the company, four of the five active BCBAs (including the second and third authors) identify as Latino/a/x. By the year 2023, seven employees who started as behavior therapists in the company are expected to obtain their BCBA certification. Five of these employees are from underrepresented racial or ethnic backgrounds, and they began as entry-level therapists in the company. As part of their new hire onboarding training, therapists were provided with information on how to grow in the company and the steps required to obtain the BCBA or BCaBA certification and were continuously encouraged to do so via meetings with administrative staff. If they decided to enroll in a college program, a tuition discount was offered through a partner university as well as an hourly raise and promotion. These employees were also invited and encouraged to attend clinical meetings with the company BCBAs and a weekly study group was held to promote engagement while supporting them in studying for the certification exam. Through this dedicated approach to mentorship the diversity of the staff may be represented equally across all tiers of the company in the coming years.

Closing Remarks

The purpose of this article was to provide recommendations and examples of actionable steps small ABA companies can take to help recruit and retain a diverse workforce, as well as descriptions of the recommendation in application. Increasing the diversity of the field will require ongoing and continuous support at all levels including national, state, and regional professional organizations; academic environments recruiting, retaining, and mentoring students from historically marginalized groups; and companies mentoring entry-level technicians from diverse backgrounds to pursue advanced degrees in the field. The recommendations and resources shared here can serve as one model for other small companies to adopt practices that promote diversity in the workforce. These recommendations are not intended to be exhaustive, but to provide a starting point for companies interested in taking meaningful steps in EDI initiatives. It is important to note that the recommendations can be replicated and are in line with suggestions provided in recent publications, including the BHCOE EDI standards for ABA organizations (BHCOE, 2021b).

Other important initiatives that can be applied that were not explicitly outlined in the recommendations described here include development of a diversity statement for the company, closed captioning videos that are shared for promotion and training, holding a mandatory diversity training (ideally by an outside agency or consultant), ensuring all buildings are accessible, and providing conflict resolution training for the leadership team (BHCOE, 2021b). Companies may also consider forming an EDI committee to continuously work on and evaluate progress the company is making toward achieving their goals related to this topic. Formation of a committee may not be feasible for small companies who have limited available human resources.

Our discussion in this article has primarily focused on race, ethnicity, and home language as important demographic variables. These demographics are representative of the community where the company of the second and third authors is located (both the clients served, and the staff hired). Some demographics related to diversity are not easily visible (e.g., religion, education, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, gender identity, [dis]abilities) and present new opportunities for companies to address. Moreover, culturally responsive care and practicing cultural humility should be practiced with all families/clients regardless of how they present or identify.

We understand that there are many researchers, practitioners, and groups in behavior analysis who have been actively engaged in EDI work for years. This article was inspired by the tireless work of the founder of the company where the second and third authors are also employed. The founder is a Puerto Rican migrant to the U.S. mainland who has been dedicated to creating a more diverse and equitable practice for over a decade. We hope that this article will contribute to the conversation others have started related to EDI in the field of behavior analysis, and that it can serve to inspire other members of our community to take steps toward developing and implementing practices related to recruitment and retention of a diverse workforce.

Acknowledgments

We thank Betzaida Fuentes, M.S., BCBA, LABA, president and founder of ABATEC. The inspiration for writing this article is a small testament to her labor of love and deep commitment to serving immigrant families who are often marginalized or forgotten. We thank Claudia Rodriguez for her comments that contributed to the content of this article, and Isabel De La Cruz for her editorial assistance. We also thank Dr. Tyra Sellers and several anonymous reviewers for their invaluable feedback on previous versions of this article.

Code Availability

N/A

Appendix 1

Staff Satisfaction Survey

Instructions: The staff satisfaction survey is designed to recruit input from employees. The purpose of this survey is to obtain information on staff satisfaction regarding overall support received. Responses will help the administration continue to actively create a more supportive and inclusive work environment. Please rate each of the following statements on a scale of 1–5.

1 = Strongly agree 2 = Disagree 3 = Neither agree nor disagree 4 = Agree 5 = Strongly disagree

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The company values me. | |||||

| 2. The company values my work. | |||||

| 3. My work schedule is consistent. | |||||

| 4. I have received the training I need to do my job. | |||||

| 5. I have the tools and resources needed to do my job. | |||||

| 6. I know who to call for assistance if I am confused or have questions about the instructions outlined in a behavior support plan or treatment plan. | |||||

| 7. I feel included and respected by my coworkers. | |||||

| 8. I feel included and respected by my supervisors. | |||||

| 9. My opinions are sought on issues that affect my job. | |||||

| 10. I feel comfortable speaking up about any job-related issues. | |||||

| 11. My supervisors are approachable and easy to talk to. | |||||

| 12. I am provided with opportunities for career advancement. | |||||

| 13. Management communicates effectively on matters important to me. | |||||

| 14. There is a culture of diversity within the company. | |||||

| 15. Different races, ethnicities, cultures, and backgrounds are represented at all levels of the company. | |||||

| 16. I would recommend others to work at this company. |

Data Availability

N/A

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The first author is an unpaid research consultant for the company of the second and third authors. The second and third authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, 42 U.S.C. § 12101 et seq. (1990). https://www.ada.gov/pubs/adastatute08.htm

- Babcock, P. (2009, June 24). Some policies do more harm than good. SHRM.org. https://www.tinyurl.com/58nypc4c

- Beaulieu L, Addington J, Almeida D. Behavior analysts’ training and practices regarding cultural diversity: The case for culturally competent care. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2018;12(3):557–575. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-00313-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (n.d.). BACB certificant data. https://www.bacb.com/BACB-certificant-data

- Behavioral Health Center of Excellence. (2021a). 2021 ABA Compensation & Turnover Report.

- Behavioral Health Center of Excellence. (2021b). Diversity, equity, and inclusion standards for ABA organization. https://www.tinyurl.com/2p8jtuxb

- Bertrand, M., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. American Economic Review, 94(4), 991–1013. 10.1257/0002828042002561

- Bortz, D. (2018). Can blind hiring improve workplace diversity? SHRM.org. https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/news/hr-magazine/0418/pages/can-blind-hiring-improve-workplace-diversity.aspx

- Bottini S, Wiseman K, Gillis J. Burnout in providers serving individuals with ASD: The impact of the workplace. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2020;100:article 103616. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2020.103616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunsma DL, Embrick DG, Shin JH. Graduate Students of Color. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity. 2017;3(1):1–13. doi: 10.1177/2332649216681565. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burks, S.V., Cowgill, B., Hoffman, M. & Housman, M.G. (2013). The value of hiring through referrals. IZA Discussion Paper No. 7382, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2266809 or 10.2139/ssrn.2266809

- Chin JL, Desormeaux L, Sawyer K. Making way for paradigms of diversity leadership. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice & Research. 2016;68(1):49–71. doi: 10.1037/cpb0000051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark CR, Mercer SH, Zeigler-Hill V, Dufrene BA. Barriers to the success of ethnic minority students in school psychology graduate programs. School Psychology Review. 2012;41:176–192. doi: 10.1080/02796015.2012.12087519. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JJ, Gabriel BA, Terrell C. The case for diversity in the health care workforce. Health Affairs (Project Hope) 2002;21(5):90–102. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condon, S. (2018, May 14). Indeed rolls out platform to remove bias from hiring. Between the Lines. https://www.tinyurl.com/44z2xerj

- Conners B, Johnson A, Duarte J, Murriky R, Marks K. Future directions of training and fieldwork in diversity issues in Applied Behavior Analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12(4):767–776. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00349-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culpepper & Associates. (2010, November 24). Salary Structures: Creating Competitive and Equitable Pay Levels. SHRM.org. https://www.tinyurl.com/h28nmmwf

- Dixon, J. A. (2020, September 29). 7 Proactive Strategies to Recruit a More Diverse Workforce. BambooHR. [Blog]. https://www.tinyurl.com/2p8n3jzc

- Flory JA, Leibbrandt A, Rott C, Stoddard O. Increasing workplace diversity: Evidence from a recruiting experiment at a Fortune 500 company. Human Resources. 2019;56(1):73–92. doi: 10.3368/jhr.56.1.0518-9489R1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fong EH, Tanaka S. Multicultural alliance of behavior analysis standards for cultural competence in behavior analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation & Therapy. 2013;8(2):17–19. doi: 10.1037/h0100970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fong EH, Catagnus RM, Brodhead MT, Quigley S, Field S. Developing the cultural awareness skills of behavior analysts. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9(1):84–94. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0111-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong EH, Ficklin S, Lee HY. Increasing cultural understanding and diversity in applied behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice. 2017;17(2):103–113. doi: 10.1037/bar0000076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, E. (2020, January 16). Indeed Assessments: Why Employers Should Leverage Skills Tests. Indeed for Employers. https://www.indeed.com/lead/indeed-assessments-skills-tests

- Glasmeier, A. K. (2021). About the Living Wage Calculator. Living Wage. https://livingwage.mit.edu/pages/about

- Gray-Stanley JA, Muramatsu N, Heller T, Hughes S, Johnson TP, Ramirez-Valles J. Work stress and depression among direct support professionals: The role of work support and locus of control. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2010;54(8):749–761. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01303.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagaman JL, Casey KJ. Teacher attrition in special education: Perspectives from the field. Teacher Education & Special Education. 2018;41:277–291. doi: 10.1177/0888406417725797. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley BK, Courtney WT, Rosswurm M, LaMarca VJ. The apprentice: An innovative approach to meet the Behavior Analysis Certification Board’s supervision standards. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9:329–338. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0136-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasnain-Wynia R, Baker DW. Obtaining data on patient race, ethnicity, and primary language in health care organizations: Current challenges and proposed solutions. Health Services Research. 2006;41(4 Pt 1):1501–1518. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00552.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinson, T. D., Brostoff, M., Grossman, A. B., Ward, V. L., Lind, K., & Wood, L. (2022). Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in the nursing workforce. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing, 47(5), 265–272. 10.1097/NMC.0000000000000840 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Holloway JH. The benefits of mentoring. Educational Leadership. 2001;58:85–86. [Google Scholar]

- Iwamasa GY. Behavior therapy and a culturally diverse society: Forging an alliance. Behavior Therapy. 1997;28(3):347–358. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(97)80080-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamasa GY, Smith SK. Ethnic diversity in behavioral psychology: A review of the literature. Behavior Modification. 1996;20(1):45–59. doi: 10.1177/01454455960201002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jabbarpour Y, Westfall J. Diversity in the family medicine workforce. Family Medicine. 2021;53(7):640–643. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2021.284957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SK, DeCelles KA, Tilcsik A, Jun S. Whitened résumés: Race and self-presentation in the labor market. Administrative Science Quarterly. 2016;61(3):469–502. doi: 10.1177/0001839216639577. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen TS, Borritz M, Villadsen E, Christensen KB. The Copenhagen burnout inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work & Stress. 2007;19(3):192–207. doi: 10.1080/02678370500297720. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis GB. Diversity, pay equity, and pay in social work and other professions. Affilia. 2018;33(3):286–299. doi: 10.1177/0886109917747615. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li A, Gravina N, Pritchard JK, Poling A. The gender pay gap for behavior analysis faculty. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12:743–746. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00347-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little A, Tarbox J, Alzaabi K. Using acceptance and commitment training to enhance the effectiveness of behavioral skills training. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. 2020;16:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malach-Pines A. The burnout measure, short version. International Journal of Stress Management. 2005;12(1):78–88. doi: 10.1037/1072-5245.12.1.78. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mani V. The effectiveness of employee referral as a recruitment source. International Journal of Management Sciences & Business Research. 2012;1(11):12–25. [Google Scholar]

- Marin A. Don’t mention it: Why people don’t share job information, when they do, and why it matters. Social Networks. 2012;34:181–192. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2011.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCuiston VE, Wooldridge BR, Pierce C. Leading the diverse workforce: Profit, prospects and progress. Leadership & Organization Development Journal. 2004;25:73–92. doi: 10.1108/01437730410512787. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKay PF, Avery DR, Tonidandel S, Morris MA, Hernandez M, Hebl MR. Racial differences in employee retention: Are diversity climate perceptions the key? Personnel Psychology. 2007;60:35–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00064.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McNab SM, Johnston L. The impact of equal employment opportunity statements in job advertisements on applicants’ perceptions of organisations. Australian Journal of Psychology. 2002;54(2):105–109. doi: 10.1080/00049530210001706573. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs. (n.d.). Postings and notice requirements. U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.tinyurl.com/4w9xtdff

- PayScale. (2022). Salary for certification: BACB board certified behavior analyst (BCBA®). https://www.tinyurl.com/2p92wpaf

- Perlow LA, Kelly EL. Toward a model of work redesign for better work and better life. Work & Occupations. 2014;41(1):111–134. doi: 10.1177/0730888413516473. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pieper JR, Greenwald JM, Schlachter SD. Motivating employee referrals: The interactive effects of the referral bonus, perceived risk in referring, and affective commitment. Human Resource Management. 2018;57:1159–1174. doi: 10.1002/hrm.21895. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pittenger AA, Barahona C, Cavalari RN, Parent V, Luiselli JK, Dubard M. Social validity assessment of job satisfaction, resources, and support among educational service practitioners for students with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Developmental & Physical Disabilities. 2014;26:737–745. doi: 10.1007/s10882-014-9389-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Plantiveau C, Dounavi K, Virués-Ortega J. High levels of burnout among early-career board-certified behavior analysts with low collegial support in the work environment. European Journal of Behavior Analysis. 2018;19(2):195–207. doi: 10.1080/15021149.2018.1438339. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, L. R., Tissue, M. M., Johnson, A., Kavanagh, L., & Warren, M. (2022). Building the MCH Public Health workforce of the future: A call to action from the MCHB strategic plan. Maternal and Child Health Journal, published online first. 10.1007/s10995-022-03377-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Reid DH, Parsons MP. A comparison of staff acceptability of immediate versus delayed verbal feedback in staff training. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 1996;16(2):35–47. doi: 10.1300/J075v16n02_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosales, R., Leon, A., Serna, R. W., Maslin, M., Arevalo, A., & Curtin, C. (2021). A first look at applied behavior analysis service delivery to Latino American families raising a child with autism spectrum disorder. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 14(4), 974–983. 10.1007/s40617-021-00572-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rosencrance, L. (2021, March 2). What is diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI)? SearchHRSoftware. https://www.techtarget.com/searchhrsoftware/definition/diversity-equity-and-inclusion-DEI

- Slowiak, J. M., & DeLongchamp, A. C. (2021). Self-care strategies and job-crafting practices among behavior analysts: Do they predict perceptions of work–life balance, work engagement, and burnout? Behavior Analysis in Practice. Advance Online Publication. 10.1007/s40617-021-00570-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, Bucceri JM, Holder A, Nadal KL, Esquilin M. Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist. 2007;62(4):271. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Alsaidi S, Awad MN, Glaeser E, Calle CZ, Mendez N. Disarming racial microaggressions: Microintervention strategies for targets, white allies, and bystanders. American Psychologist. 2019;74(1):128–142. doi: 10.1037/amp0000296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugai G, O’Keeffe BV, Fallon LM. A contextual consideration of culture and school-wide positive behavior support. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2012;14(4):197–208. doi: 10.1177/1098300711426334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, M. A. (2021). How to ensure pay equity for people of color. SHRM.org. https://tinyurl.com/29f74ysk

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (2016, November 18). EEOC enforcement guidance on national origin discrimination.https://www.eeoc.gov/laws/guidance/eeoc-enforcement-guidance-national-origin-discrimination

- Vance, H., & Saini, V. (2022). Pay equity in applied behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice. Advance online publication. 10.1007/s40617-022-00708-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wine B, Reis M, Hantula DA. An evaluation of stimulus preference assessment methodology in organizational behavior management. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2014;34(1):7–15. doi: 10.1080/01608061.2013.873379. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

N/A