Abstract

Objective:

The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic had greatly impacted health worldwide. The nationwide lockdown was imposed to contain the virus transmission, which indirectly affected health care utilization. Pediatric patients’, as they are considered as a vulnerable group, parents faced a significant challenge to manage their children’s surgical and medical care needs during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. The study aims to explore the parental approach to health care facilities to meet children’s surgical care needs during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic.

Materials and Methods:

A qualitative approach was adopted to fulfill the objective by conducting an in-depth interview using a semi-structured interview schedule among 26 parents of children with perioperative surgical care needs at a tertiary care hospital, eastern India. The digitally recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim. Thematic analysis was employed to understand the parent’s experience toward meeting children’s surgical care needs during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic lockdown. QSR NVIVO software version 12 was used for data management.

Results:

The study found 3 themes related to parent’s experience which include state of desperation (sub-themes: lockdown effect, ignorant to the health facility, phobic to coronavirus disease infection, and testing), state of assurance (sub-themes: telemedicine: accessibility, approachability, and applicability), and state of serenity (sub-themes: refrained from somatic symptoms and shouldering the responsibility).

Conclusion:

Despite various hurdles parents faced during the pandemic, telemedicine helped parents meet their children’s surgical care needs. Framing guidance, protocols to deal with emergency and primary care delivery, and disseminating information on telemedicine facilities to grassroot level to the community can protect this vulnerable population in the upcoming surge of coronavirus disease 2019 waves.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, surgical care needs, children, telemedicine, health facility

What is already known on this topic?

Implementation of nationwide lockdown during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, directly and indirectly, affected health care utilization.

The extent of the pandemic lockdown effect was measured quantitatively but not qualitatively, especially among parents.

Telemedicine was an adjunct besides direct patient consultation in the hospital, and it was not used widely.

What this study adds on this topic?

Pediatric patients’ parents, as they were considered as the vulnerable group, struggled a lot to overcome the hurdles of the lockdown effect to meet their children’s health care needs. Government and stakeholders should take initiative to facilitate the public to approach health facilities during any pandemic.

The telemedicine facility has become a necessity, the only option during pandemics to access health care facilities.

Detailed guidance and protocols framed to deal with emergency and primary care delivery through telemedicine would help the public and physicians manage and meet health needs in upcoming waves of coronavirus disease and any health disaster in the future.

Introduction

By the end of January 2020, the World Health Organization announced the coronavirus disease 2091 (COVID-19) infection as a public health emergency of international concern, followed by the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) as a pandemic.1 As the COVID-19 spread increased across the nation, India received its first case of COVID-19 by January 30, 2020, and the acceleration of the spread of the virus was uncontrollable.2 As a result, enormous COVID-19-positive cases invaded health care facilities. To contain the virus spread, various preventive measures were initiated by the Indian Government, and it declared nationwide lockdown on March 24, 2020, which was continued further.1 Due to alarm on upsurge of COVID-19 third wave, most of the Indian states continued lockdown with limitations. As a consequence of lockdown, most of the facilities were hampered, including health care in routine preventive and curative services across the nation, which affected the people with chronic diseases and other physical disabilities. Maternal and child health services were affected a lot in the center and the periphery. Few health care facilities were converted as COVID care centers by shutting down other routine services, including elective surgeries, outpatient services, outreach services, and by keeping only emergency services on function. On the other hand, the patients too worried about acquiring a COVID infection during hospital visits resulted in a withdrawal of hospital follow-up other than emergency health needs.3

Out of all age groups, the pediatric patients had a severe impact during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown by making it difficult to continue treatment, especially for chronic pediatric medical conditions, and seeking treatment for acute illnesses.4 In addition, it had hampered surgical follow-up and hindered attention toward surgical care needs due to lockdown transportation. To avoid the spreading of infections, the health ministry encouraged using alternative measures to continue the medical services across the nation.5 On the other hand, how the parents of children with surgical care needs managed to access the health care facility was unknown. Hence, the present study was undertaken to explore their experience during the COVID-19 pandemic in eastern India’s selected tertiary care hospital.

MATERIALS AND Methods

Setting and Participants

The present study was undertaken in the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), a public tertiary care hospital situated in the eastern part of India at Odisha state. All India Institute of Medical Sciences is an autonomous body established by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare under Pradhan Mantri Swasthya Suraksha Yojana, with 764 beds covering super specialty departments with 24 hours casualty and critical care units. Pediatric department facilities consist of pediatric medical surgery units functioning around the clock with comprehensive monitoring by health care professionals. Due to an upsurge of COVID-19 first and second wave, the institute had stopped the outpatient services of all specialties and shut down was implemented from April 2021 to the end of June 2021. Patients were also encouraged to utilize “telemedicine (WhatsApp calls) and “AIIMS swasthya app” for consulting with a physician for their health care needs. A separate telemedicine number from each department was provided, disseminated through social media and institute website where patients get to know about health services during the shutdown period. The pediatric surgery department is also involved in telemedicine services, and pediatric surgical patients used such services to meet their surgical care needs. The present study included children with surgical care needs (preoperative and post-surgical follow-up care needs) who approached the health care facility. From the pediatric surgery registry maintained in the department, the investigator obtained the contact information about children who underwent surgery 2 months before outpatient department shutdown to know how they could continue the follow-up care needs and about those children who have undergone surgery for acute surgical care needs during the pandemic period.

Data Collection Methods

The study adopted the qualitative approach and conducted the interview using a semi-structured interview schedule. Rapport was established telephonically to interact with the parents for their willingness to participate in the interview. Out of 35 parents who were approached, 4 declined to participate because of their busy schedule and 5 parents’ contact number was not reachable. After explaining the study purpose, those who agreed to participate and gave telephonic verbal consent were included in the study. A total of 26 parents of children with surgical care needs participated in the study.

Sample and Instruments

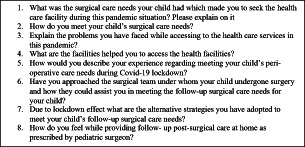

Data were obtained through in-depth interviews (IDIs). The IDIs were carried out at the participants’ convenient time telephonically (14 interviews) and as face-to-face conversation (12 interviews). The interview was conducted in the regional language (Odiya). After receiving verbal telephonic consent, the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants were collected. The participants were aware of the audio recording of the interview session, and confidentiality was ensured. As the parents expressed their experiences after the 24-25th interview, there was no new information received from them which helped the researcher to ensure the data saturation, and the data collection was curtailed. The interview was conducted using open-ended questions, which lasted 30-45 minutes. The in-depth interview guide contained the following questions given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Semi-structured interview guide on parents’ approach to meet children’s surgical health care needs during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic.

As the parents spoke about how they could meet their children’s surgical care needs, the researcher asked questions to help the participants explain who, what, why, where, and how the child was managed in meeting surgical care needs. Once the data were saturated and no further new information was added from the participants, the interview was terminated. Ethical permission was obtained from the hospital’s Institutional Ethics committee of AIIMS Bhubaneswar (I/IM-NF/Nursing/20/211). Before initiating the interview, informed telephonic verbal recorded consent (telephonic interview) and written consent (face-to-face interview) were obtained from each participant. The interviewer was a pediatric nurse working in the pediatric surgery unit who was fluent in speaking the regional language (Odiya) of study participants.

Data Analysis

The socio-demographic information of the children and the parents were analyzed using descriptive statistics including mean and frequency percentage. The digitally recorded interviews were initially transcribed verbatim and then translated into the English language. The data were subjected to content analysis.6 The first author performed the coding process, and confirmation on the codes, categories, and sub-categories was done by the second author. Both researchers were from the field of nursing. Data were systematically studied, the transcripts were read and re-read several times, which gave an overall idea about the researcher’s content. Initial codes were then generated and allocated to relevant sentences and paragraphs, which helped identify the concepts. Later, the concepts were grouped into categories. The categories were reviewed and named with definitions. The categories were primarily descriptive and represented a broad scope to allow for variation. Instead of imposing a preselected theoretical grid on the data, this method ensured that the coding frame elements reflected the language of parent’s experience toward approaching health care facilities to meet children’s surgical care needs during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. QSR NVIVO software version 12 was used for data management.

Trustworthiness/Rigor

Credibility was ensured by including study participants of varied clinical characteristics and the pre-and post-surgical follow-up approach to the health care facility. The authors were from diverse educational backgrounds, with all having academic teaching and research experience, which enriched the study’s findings and helped in data triangulation. During analysis, audiotaping of interviews and auditing of transcripts enhanced the data’s dependability. The researchers’ condensation of interviews, thick data description, and exploration of similarities and differences in parent’s experiences for their children’s surgical care needs were done independently. We used consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies guidelines for our study.

Results

The socio-demographic and clinical information of the study participants are as follows:

The qualitative analysis in the present study found 3 categories with a theme on “Telemedicine-A ray of hope for parents of children with surgical care needs during pandemic.” The categories are as follows:

State of desperation

State of assurance

State of serenity

State of Desperation

Lockdown Effect

Due to the COVID pandemic lockdown, the parents were shocked that their children’s surgical follow-up would get interrupted. Parents of children with postoperative surgical care needs were worried about the transportation halt announced across the nation that hindered them from accessing health care facilities. Parents of children with pre-op surgical care needs struggled to approach health care facilities due to closure near them and needed to approach government health facility which is far and pushed them to take private transport to approach a higher health care facility. This was expressed as:

“Doctor asked me to bring the child for follow-up after six months. I have not gone due to this lockdown. Now it crossed eight months.”

“What to do? Doctor asked me to bring the child every two months once. But it is 300 kilometers from here to the hospital where surgery was performed. So am not able to show my child due to this pandemic.”

“I have shown my child in a nearby private clinic instead of showing in the big hospital where surgery has performed.”

“The local hospital refused to take my child for admission as they stopped inpatient due to COVID pandemic. Only symptomatic management was possible to do there. But somehow, I reached this (AIIMS) health care facility.”

Ignorant to Facility

Few parents reported that they were unaware of the “Telemedicine” facility to meet the follow-up care available in the hospital in which their child had undergone surgery. Also, from unknown sources, parents received information about alternate health care services provided to patients. On the other hand, few parents had the contact number of physicians to call the physician on the telephone and consulted for follow-up care for the child. Parents reported as follows:

“I did not know about Telemedicine facility. If I could know, I could have consulted the physician. However, now my child is fine. There is no urgency or emergency for him.”

“A stranger mentioned to me about Telemedicine facility. However, unfortunately, I do not have a video mobile to show my child and his reports to the physician. So, I borrowed others mobile to use that facility.”

Phobic to COVID and Testing

Parents also specified they were worried about taking their children to the hospital in this pandemic where either the parent or the child may harbor the COVID-19 infection. They refrained from taking the risk of traveling from home to hospital for follow-up care for their children. They also reported that without having the COVID-negative report in hand, they might not be permitted to get admission to the hospital.

“I am worried that if I travel distant with my child on the way, we may contract the COVID infection. So, I decided not to go for surgical follow-up care in this pandemic situation.”

“In every place they (police/security) asking COVID free report. I am worried about doing an investigation as I do not have any symptoms. However, My child needs treatment, so we both have to undergo testing for COVID-19 to get admission.”

State of Assurance

Accessibility

Parents expressed that the hospital website, physician contact/communication, WhatsApp friends’ group, and even a strange person were the various sources from which they came to know about the telemedicine facility. Few parents specified they could not access the telemedicine facility, got a delay in the call, and had connectivity and network issues. On the other hand, parents also specified they could talk with physicians, send images of reports taken from nearby health care facilities or diagnostic centers, have direct conversation with physicians, and visual examination of the child were made possible with the help of telemedicine.

“After getting the telemedicine number, I called the physician. I could make conversation, show my child, shared my child’s reports. In this pandemic, it was a great help for people like us to access health care facilities.”

“Once the physician saw my child through video call, he asked me to admit the child immediately as he required surgical intervention. Even though I am 250 kilometers far away, by train, I could reach this health care facility for my child’s treatment.”

Approachability

Parents expressed they were contented with the telemedicine facility where physicians were approachable and showed their responsibility in child care by listening to parental and child’s concerns and directed parents on the necessity of surgical interventions, admission, follow-up, etc.,

“I am happy for the health care facility (Telemedicine) as well as the child specialist who took care of my child. Amid all pandemic difficulties, the physician was more approachable and concerned about my child’s surgical care needs.”

“The physician was attended my video call and asked me to share all the reports. As I was not able to do the investigation near to my home, I could do the USG CT scan immediately for my child after reaching this health care facility.”

Applicability

Parents reported that the telemedicine facility was applied well and sound at the right time of the pandemic. Those who resided in a distant place from the hospital got treatment via video call and refrained from acquiring COVID-19 infection, avoided unnecessary travel, and overcame the transportation difficulties and demand of submitting evidence of COVID-free status at each district borders of the state.

“My stress about child’s surgical follow-up care was relieved because of this telemedicine facility. Otherwise, I have to travel throughout the state of Odisha. My child’s doctor checked by video call about his urinary elimination and said the child is fine. So I have not come to the hospital for follow-up care.”

“I wandered more than three hospitals for my child’s surgical condition, a doctor from Cuttack Hospital (nearby tertiary care public hospital) talked with the child specialist in this health facility through video call, and my child got referral service.”

State of Serenity

Refrained from Somatic Symptoms

Parents expressed that they were delighted to see their children in a disease-free stable state and with alleviated symptoms of pain, feeding difficulties, urinary and bowel elimination issues, and psychological stress after the treatment, which were facilitated through a telemedicine facility.

“My child is fine now. She could able to eat well, sleep without complaints of pain. What else do I need more than this? I thank the medical team members who helped me to reach this health facility through video call.”

“My child had abdomen pain and constipation. Through video call, I could reach the physician, and he asked me to do few tests which were not possible in my hometown. So, he was brought to this facility and undergone treatment. Now he is fine.”

Shoulder the Health Care Responsibility

A parent whose child recovered from surgical condition expressed her happiness that she had shared the telemedicine link to most of her friends, families, and neighbors and circulated it through social media, which may help other parents of children with pediatric surgical concerns and other health care needs, and they could approach health care professionals and receive treatment on time during this COVID-19 pandemic situation through this alternative facility. Parents too shouldered the responsibility of spreading alternate options available to access health care facilities for those with health care needs in times of pandemic.

“I do not know when this lockdown may get over, and COVID may come to an end, but as much as possible, I am sharing this facility to all my known person and others through social media.”

“Let everyone utilize this facility for their health needs, I wish.”

“I have heard many more waves of COVID pandemic yet to come. What will the children with surgical concerns and other illnesses do in a lockdown situation? Whomever I know, I have shared this number. Let everyone get benefitted by this.”

Discussion

The present study explored the state of the parents having children with surgical care needs during the COVID-19 pandemic and how they could access the health care facility to meet their children’s surgical care needs. It was found that parents were in a desperate state due to lockdown effects such as lack of transportation facilities, fear of infection spread, the necessity of proving themselves as COVID-free to cross the district borders, and getting their child admitted to the hospital. Consistent with this, Aklilu7 studied the health care-seeking behavior of people from Ethiopia and found that medication was missed, loss of follow-up, and death occurred as 12%, 70%, and 1.3% were affected due to pandemic effect and transportation issues were the significant reason for missed follow-up during pandemic (adjusted odds ratio (OR) = 6.11, 95% CI: 3.06-12.17, P < .001).7 Kuruvilla et al8 in India compared the patients’ health care-seeking behavior and found it to be decreased by 31.01% from 2019 to 2020 and a decline in pediatric patient’s visit by 37.2%. They concluded that the fall in patients during the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with lockdown restrictions to contain the virus. Williams et al.9 in their retrospective cohort study, identified the indirect effect of COVID-19 on pediatric health care use and identified that national lockdown affected reduction in utilization of pediatric emergency care. Kruizinga et al10 in Netherland found a reduction in pediatric emergency department utilization and hospitalization, including hospital admission, emergency, or outpatient visit. They stated that decreased health care utilization for non-infectious disease indicating avoidance of pediatric care during the COVID-19 pandemic was significant. These shreds of evidence aid in understanding lockdown effects that influenced health care utilization worldwide, including pediatric populations.

Briggs et al11 stated that strengthening the health care system and enhancing the accessibility development of contextual strategies are the prime needs to mitigate the pandemic effect and accelerate the health care facility access and utilization by parents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Parents from India believed telemedicine facility as a ray of hope to meet their child’s surgical care needs. Amid this pandemic, an inevitable opportunity to rescue parents and children with health needs was “telemedicine.” Through the telemedicine facility, the parents exchanged information on the child’s status by video phone calls, which facilitated the physician in diagnosing and treating disease conditions and reducing overcrowding in the hospitals. Telemedicine ensured equitable delivery of services to all, which was cost-effective, health protection to physicians and patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, and rendered timely and fast care. Telemedicine has its pros and cons to patients and practitioners such as it is time-saving, easily accessible, maintains social distancing, provides health education, reduces overcrowding, is cost-effective, enables refill prescription and triaging, etc. On the other hand, the physician found technological issues, lack of physical examination, missed diagnosis, patient illiteracy, medico-legal issues, prescription errors, confidentiality, etc. Despite its pros and cons, when more health care professionals were affected by this pandemic, telemedicine was the only promising choice.5 Parents were delighted to access the health care facility through this alternative option. In a literature review, Iyenger et al12 cited that telemedicine was significantly applied through smartphone technology during the COVID-19 pandemic to manage health care issues. The study was limited to parents of children with surgical care needs during the COVID-19 pandemic, not with any other disease conditions. Due to pandemic lockdown, telephonic interview was conducted with parents of children who had post-surgical follow-up care needs. The study was limited to a tertiary care public hospital.

Summary

The present study explored how parents of children with surgical care needs would be able to approach the health care facility during the COVID-19 pandemic among 26 parents in a tertiary care hospital and found that parents were desperate because of transportation halt, health care facility shut down, and keeping themselves as COVID-free with evidence to reach the hospital. Furthermore, the telemedicine facility was the only option and hope for them, which was accessible, approachable, and applicable in times of the COVID-19 situation. Parents managed minor ailments at home and in local clinics that ultimately affected the health care-seeking behavior of the people by postponing the child’s follow-up care. Amid the pandemic, telemedicine had a major role to bridge the needs of parents with health care needs. The better utilization of telemedicine would be possible by framing policies and guidelines by health department and disseminating the same to common public helps in future to manage and meet the health care needs in times of pandemic.

Conclusion

During COVID-19, parents had to face various issues to access the health care facilities. Amid the pandemic, telemedicine had a major role to bridge the needs of parents with health care needs. Even though physicians were comfortable with the usual treatment method during the pre-pandemic stage, everyone had no choice other than telemedicine. In India, telemedicine was welcomed by both patients and practitioners as it is necessary to meet health care needs. Detailed guidance and protocols need to be framed to deal with emergency and primary care delivery through telemedicine as children are the vulnerable population. Spreading awareness on telemedicine facilities to the periphery through community health workers, framing policies and guidelines by health department, and disseminating the same to general public help to manage and meet the health care needs during subsequent pandemic waves.

| (n=26) | ||

| Sl. No | Demographic characteristics | Frequency (Percentage) Mean ±SD |

| 1. | Parents age | 37 ±5 years |

| 2. | Educational status | |

|

10 (38.4%) | |

|

9 (34.6%) | |

|

5 (19.2%) | |

|

2 (7.6%) | |

| 3. | Occupational status (during covid) |

|

|

8 (30.7%) | |

|

4 (15.3%) | |

|

14 (53.8%) | |

| 4. | Religion | |

| a) Christian | 1 (3.8%) | |

| b) Muslim | 2 (7.6) | |

| c) Hindu | 23 (88.4%) | |

| 5. | Child’s age | |

| a) <12 months | 6 (23%) | |

|

7 (26.9%) | |

|

5 (19.2%) | |

|

3 (11.5%) | |

|

5 (19.2%) | |

| 6. | Child’s gender | |

|

16 (61.5%) | |

|

10 (38.4%) | |

| 7. | Health care needs | |

|

14 (53.8%) | |

|

12 (46.1%) | |

| 8. | Parents used telemedicine | |

|

16 (61.5%) | |

|

10 (38.4%) | |

| 9 | Surgical pathologies related to system | |

|

8 (30.7%) | |

|

7 (26.9%) | |

|

5 (19.2%) | |

|

6 (23%) | |

| SD, standard deviation; CNS, central nervous system. | ||

Footnotes

Ethics Committee Approval: This study was approved by the Hospital’s Institutional Ethics committee of All India Medical Sciences, Bhubaneswar, India (I/IM-NF/Nursing /20/211).

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patients who agreed to take part in the study.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept – S.K., H.J; Design – S.K., H.J., A.S., S.M.; Supervision – S.M., K.D.; Funding – None ; Materials – H.J., A.S.; Data Collection and/or Processing – H.J; Analysis and/or Interpretation – H.J., S.K.; Literature Review – H.J., S.K.; Writing – H.J., Critical Review – K.D., A.S., S.M.

Declaration of Interests: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Funding: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

References

- 1. Singh AK, Jain PK, Singh NP.et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and child health services in Uttar Pradesh, India. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2021;10(1):509-513. 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1550_20) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Verma BK, Verma M, Verma VK.et al. Global lockdown: an effective safeguard in responding to the threat of COVID-19. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;26(6):1592 1598. 10.1111/jep.13483) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Praticò AD. COVID-19 pandemic for Pediatric Health Care: disadvantages and opportunities. Pediatr Res. 2020;89:709 710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Seth R, Das G, Kaur K.et al. Delivering pediatric oncology services during a COVID-19 pandemic in India. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(12):e28519. 10.1002/pbc.28519) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Using telemedicine During the COVID-19 pandemic. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32412914/. Accessed 2021 August 29. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Guest G, MacQueen KM. Applied Thematic Analysis. Sage Publication; 2011. Available at: https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/applied-thematic-analysis/book233379 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aklilu TM, Abebe W, Worku A.et al. The impact of COVID-19 on care seeking behavior of patients at tertiary care follow-up clinics: a cross-sectional telephone survey. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Affliation for all authors. Available at: 10.1101/2020.11.25.20236224. Accessed 2021 August 29. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kuruvilla KP, Varghese PR, Vinu EV, Gopi IK. Paradigm shift in healthcare seeking behavior: a report from central Kerala, India, during COVID-19 pandemic. CHRISMED J Heal Res. 2020;7(4):271. Available at: https://www.cjhr.org/article.asp?issn=2348-3334;year=2020;volume=7;issue=4;spage=271;epage=275;aulast=Kuruvilla. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Williams TC, MacRae C, Swann OV.et al. Indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on paediatric healthcare use and severe disease: a retrospective national cohort study. Arch Dis Child. 2021;106(9):911 917. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-321008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kruizinga MD, Peeters D, Veen van M.et al. The impact of lockdown on pediatric ED visits and hospital admissions during the COVID19 pandemic: a multicenter analysis and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2021;180(7):2271-2279. 10.1007/s00431-021-04015-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Briggs DC, Kattey KA. COVID-19: parents’ healthcare-seeking behaviour for their sick children in Nigeria - an online survey. Int J Trop Dis Heal. 2020:14 25. 10.9734/ijtdh/2020/v41i1330344) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Iyengar K, Upadhyaya GK, Vaishya R, Jain V. COVID-19 and applications of smartphone technology in the current pandemic. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2020;14(5):733 737. 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.033) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Content of this journal is licensed under a

Content of this journal is licensed under a