Abstract

Background

Telemental health (delivering mental health care via video calls, telephone calls, or SMS text messages) is becoming increasingly widespread. Telemental health appears to be useful and effective in providing care to some service users in some settings, especially during an emergency restricting face-to-face contact, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. However, important limitations have been reported, and telemental health implementation risks the reinforcement of pre-existing inequalities in service provision. If it is to be widely incorporated into routine care, a clear understanding is needed of when and for whom it is an acceptable and effective approach and when face-to-face care is needed.

Objective

This rapid realist review aims to develop a theory about which telemental health approaches work (or do not work), for whom, in which contexts, and through what mechanisms.

Methods

Rapid realist reviewing involves synthesizing relevant evidence and stakeholder expertise to allow timely development of context-mechanism-outcome (CMO) configurations in areas where evidence is urgently needed to inform policy and practice. The CMO configurations encapsulate theories about what works for whom and by what mechanisms. Sources included eligible papers from 2 previous systematic reviews conducted by our team on telemental health; an updated search using the strategy from these reviews; a call for relevant evidence, including “gray literature,” to the public and key experts; and website searches of relevant voluntary and statutory organizations. CMO configurations formulated from these sources were iteratively refined, including through discussions with an expert reference group, including researchers with relevant lived experience and frontline clinicians, and consultation with experts focused on three priority groups: children and young people, users of inpatient and crisis care services, and digitally excluded groups.

Results

A total of 108 scientific and gray literature sources were included. From our initial CMO configurations, we derived 30 overarching CMO configurations within four domains: connecting effectively; flexibility and personalization; safety, privacy, and confidentiality; and therapeutic quality and relationship. Reports and stakeholder input emphasized the importance of personal choice, privacy and safety, and therapeutic relationships in telemental health care. The review also identified particular service users likely to be disadvantaged by telemental health implementation and a need to ensure that face-to-face care of equivalent timeliness remains available. Mechanisms underlying the successful and unsuccessful application of telemental health are discussed.

Conclusions

Service user choice, privacy and safety, the ability to connect effectively, and fostering strong therapeutic relationships need to be prioritized in delivering telemental health care. Guidelines and strategies coproduced with service users and frontline staff are needed to optimize telemental health implementation in real-world settings.

Trial Registration

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO); CRD42021260910; https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021260910

Keywords: telemental health, remote care, telemedicine, mental health, COVID-19, digital exclusion, realist review, telemedicine, virtual care, rapid realist review, gray literature, therapy, health care staff, digital consultation, frontline staff, children, inpatient, mobile phone

Introduction

Background

Telehealth is defined as “the delivery of health-related services and information via telecommunications technologies in the support of patient care, administrative activities, and health education” [1]. Telemental health refers to such approaches within mental health care settings. It can include care delivered by means such as SMS text messaging and chat functions but most commonly refers to telephone calls and video calls, which are central to telemental health care.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, there was interest in many countries and settings in integrating new technologies, including telemental health approaches, more widely and effectively in mental health care services. This was of particular interest in countries where face-to-face (ie, in-person) mental health care was largely inaccessible to remote communities [2]. Research has demonstrated that telemental health can be successful in various contexts, although studies before the pandemic tended to relate to relatively small-scale and well-planned applications of telemental health with volunteer participants, rather than large-scale implementations across whole service systems. Telemental health has been found to be effective in reducing treatment gaps and improving access to mental health care for some service users [3-5]. This includes those who live far from services or where caring responsibilities affect their ability to travel [6-8]. Positive outcomes and experiences have been reported across a range of populations (including adult, child and adolescent, older people, and ethnic minority groups) and settings (including hospital, primary care, and community) [9-11]. Some evidence has suggested that telemental health modalities such as videoconferencing are equivalent to, or even better than, face-to-face modalities for some service users in terms of quality of care, reliability of clinical assessments, treatment outcomes, or adherence [9,10,12,13]. High levels of service user acceptance and satisfaction with telemental health services have also been reported in research samples [4] and for certain populations, including those with physical mobility difficulties, social anxiety, or severe anxiety disorders [6,7]. However, conversely, telemental health services are not appropriate for or favored by all service users, and there is no one-size-fits-all approach. In particular, service users experiencing social and economic disadvantages, cognitive difficulties, auditory or visual impairments, or severe mental health problems (such as psychosis) have benefited less from telemental health interventions [14,15]. Digitally excluded service users tend to be people who are already experiencing other forms of disadvantage and are already at risk of poorer access to services and less good quality care; thus, a switch to telemental health may exacerbate existing inequalities [16,17]. In addition, concerns have been raised around the impacts of telemental health on privacy and confidentiality of clinical contacts, especially for the many service users who do not have the appropriate space and facilities for its use, as well as its appropriateness for certain purposes, such as conducting assessments or risk management [14].

Encouraging evidence of telemental health acceptability and effectiveness from prepandemic research tended to relate to limited populations who had opted into well-planned remote services [18]. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of telemental health around the world greatly accelerated, and telemental health became a routine approach for maintaining and delivering mental health services. Telemental health initiatives were central to delivering mental health services in the context of this emergency. Technological initiatives have also helped to address social isolation, which worsened throughout the pandemic [6,19]. In the United Kingdom, there were large increases in remote consultations in National Health Service (NHS) primary care [20], and national data reported that most contacts in NHS mental health settings were delivered remotely in 2020 [21], particularly during the first UK lockdown (March to July 2020).

Following the rapid adoption of telemental health at the start of the crisis, service planners, clinicians, and service users have expressed interest in the greater use of telemental health in the long term [14,19,22,23]. However, several challenges have been identified as arising from this widespread implementation [14,16,19,24,25]. These include (1) reaching digitally excluded populations, who may, for example, have limited technological access or expertise or both, thus compounding existing inequalities experienced by disadvantaged groups; (2) a lack of staff competence in using telemental health devices and confidence in delivering telemental health care; (3) a lack of technological infrastructure within health services; (4) challenges in managing clinical and technological risks in remotely delivered care; (5) developing and maintaining strong therapeutic relationships online, especially when the first contact is remote rather than face-to-face; (6) maintaining service user safety and privacy; and (7) delivering high-quality mental health assessments without being able to see or speak to the service user face-to-face. It is also more difficult to undertake physical assessments, including for physical signs linked to mental health, and side effect monitoring.

Both for future emergency responses and to establish a basis for the integration of telemental health into routine service delivery (where appropriate) beyond the pandemic, evidence is needed on how to optimize telemental health care, given the unique relational challenges associated with mental health care, and identify what works best and for whom in telemental health care delivery and in which contexts. It is also important to identify contexts in which telemental health is unlikely to be safe and effective, where face-to-face delivery should remain the default.

A methodological approach developed to address questions of which interventions work, for whom, and in which contexts in a timely way is the rapid realist review (RRR) [26]. This methodology has been developed to rapidly produce policy-relevant and actionable recommendations through a synthesis of peer-reviewed evidence and stakeholder consultation. A key characteristic of realist methodology is the focus on interactions between contextual factors (eg, a certain population, geographical location, service setting, or situation) and relevant mechanisms (eg, behavioral reactions, participants’ reasoning, or resources), which affect the outcomes of interest, such as intervention adherence or service user satisfaction [26-28]. Together, these are used to develop context-mechanism-outcome (CMO) configurations, which comprise the fundamental building blocks of realist synthesis approaches. Evidence from the wider literature is also drawn upon to develop midrange theories. Midrange theories are program theories that aim to describe how certain mechanisms in specific contexts result in specific outcomes [29]; the use of the wider literature to develop midrange theories helps to elaborate and refine the developed CMO configurations by shedding further light on how their mechanisms operate [26,30-32]. Additional information on realist terminology can be found in Multimedia Appendix 1.

Objective

This is a unique opportunity to establish the characteristics of high-quality telemental health services and use these findings to identify key mechanisms for acceptable, effective, and efficient integration of telemental health services into routine mental health care. Using a realist methodology, in this RRR, we aimed to answer the question of what telemental health approaches work, for whom, in which contexts, and how? Specifically, we investigated the following questions in this review:

What factors or interventions improve or reduce adoption, reach, quality, acceptability, or other relevant outcomes in the use of telemental health in any setting?

Which approaches to telemental health work best for which staff and service users in which contexts?

In what contexts are phone calls, video calls, or SMS text messages preferable, and in which contexts should mental health care be delivered face-to-face instead?

We focus particularly on groups and contexts identified as high priority by policy makers (the process is described in detail in the Methods section), including children and young people, crisis care and inpatient settings, and groups at high risk of digital exclusion; examples from these groups are included wherever possible.

Methods

Overview

The RRR was conducted by the National Institute for Health Research Mental Health Policy Research Unit (MHPRU), a team established to deliver evidence rapidly to inform policy making, especially by the Department of Health and Social Care in England, associated government departments, and NHS policy leadership bodies. The project constitutes the final stage in a program of work on telemental health delivery conducted to meet urgent policy needs, which included an umbrella review of pre–COVID-19 evidence [18], a qualitative investigation of service user experiences of telemental health [24], a systematic review of literature on telemental health adoption conducted during the early phase of the pandemic [14], and a systematic review on the cost-effectiveness of telemental health approaches (personal communication by Clark et al, 2022). This RRR was registered on PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews; CRD42021260910).

We conducted the RRR during the COVID-19 pandemic, with videoconferencing via Zoom (Zoom Video Communications) as the primary means of communication among the research team.

Study Design

An expert reference group of 28 people, including 16 (57%) university-employed academics, 7 (25%) experts by experience (lived experience researchers from the MHPRU Lived Experience Working Group (LEWG) with personal experiences of using mental health services or supporting others or both), and 8 (29%) experts by profession (including frontline clinicians), guided and contributed to the RRR throughout. Some members belonged to multiple groups and therefore worked from several (academic, clinical, or lived experience or multiple) perspectives.

The group met weekly throughout this process from July to November 2021. The expert reference group meetings served to develop and refine the study protocol; plan the searches for evidence (particularly the targeted additional searches supplementing the initially planned strategy); iteratively examine, refine, and validate the CMO configurations derived from our evidence synthesis, with reference to their expertise by experience or profession or both; and plan wider consultation on our emerging findings. Members of the expert reference group also contributed to the literature searches, data extraction, synthesis, and interpretation of data.

The stages of our RRR were based on the following five steps, variations of which have been described and used in previous studies [26,31,32]:

Developing and refining research questions

Literature searching and retrieving information (data/stakeholder views)

Screening and extracting information/data

Synthesizing information/data

Interpreting information/data

Our approach to these steps was iterative rather than linear, particularly for steps 3, 4, and 5, where there were multiple phases of extraction, synthesis, and interpretation. This is described in detail in the following section.

Developing and Refining the Research Question

We formulated the research question in response to policy maker needs. We reviewed findings from earlier stages of the MHPRU’s program on COVID-19 impact on mental health care and on telemental health [6,18,19,24,33] with policy makers, including senior officials and mental health teams in the Department for Health and Social Care, NHS England, and Public Health England. We then identified questions to be addressed from their perspective to plan for future implementation and delivery of telemental health. This included considering how best to incorporate telemental health in routine practice once the need for its emergency deployment passes. Early in these discussions, three priority groups regarding the evidence that is currently lacking were identified as especially important for policy and planning: children and young people, users of inpatient and crisis care services, and digitally excluded groups. Digitally excluded groups include those who have no or reduced access to the digital world because of a lack of digital skills (eg, using computers or smartphones), connectivity (eg, access to the internet or phone signal), and accessibility (eg, those who may require assistive technology or do not have access to digital devices or connectivity because of, eg, costs). Our primary question of which telemental health approaches work, for whom, and in what context originated in these discussions and was further refined by the MHPRU core research team who identified a RRR methodology as appropriate and further refined the primary and secondary questions and methodology with the expert reference group before registering the protocol.

Selection Criteria

Sources were included if they met the criteria described in the following sections.

Participants

Participants included staff working in the field of mental health, people receiving care from mental health services, family members, and other supporters of people receiving mental health care.

Interventions

Interventions included any form of remote (spoken or written) communication between mental health professionals, or among mental health professionals and service users, family members, and other supporters, using video calls, telephone calls, SMS text messaging services, or hybrid approaches combining face-to-face and web-based modalities. Peer support communications were also included alongside any strategies or training programs to support the implementation of the abovementioned interventions. Self-guided web-based support and therapy programs were excluded.

Types of Evidence

This included qualitative or quantitative evidence on (1) what improves or reduces adoption, reach, quality, acceptability, or clinical outcomes in the use of telemental health; (2) impacts of introducing interventions or strategies intended to improve adoption, reach, quality, acceptability, or clinical outcomes; (3) interventions or strategies intended to help mental health staff make more effective use of telemental health technologies; (4) impacts of telemental health on specific service user groups and settings, including people who are digitally excluded, users of inpatient and crisis care services, and children and young people; and (5) the appropriateness of the use of telemental health versus face-to-face care in particular contexts. In addition to outcomes, sources were required to include information on mechanisms (ie, what works, for whom, and how).

Study Design

This included any qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods study design, including relevant service evaluations, audits, and case series. Gray literature and other sources, such as websites, stakeholder feedback, and testimonies from provider organizations and service user and carer groups were also included. Sources were also included if the focus was not solely on remote working, but the results contained substantial data relevant to our research questions. Substantial data had to provide relevant and sufficient information on context, mechanisms, and outcomes and contribute to the development of overarching CMO configurations. Editorials, commentaries, letters, conference abstracts, and theoretical studies were excluded.

Search Strategy

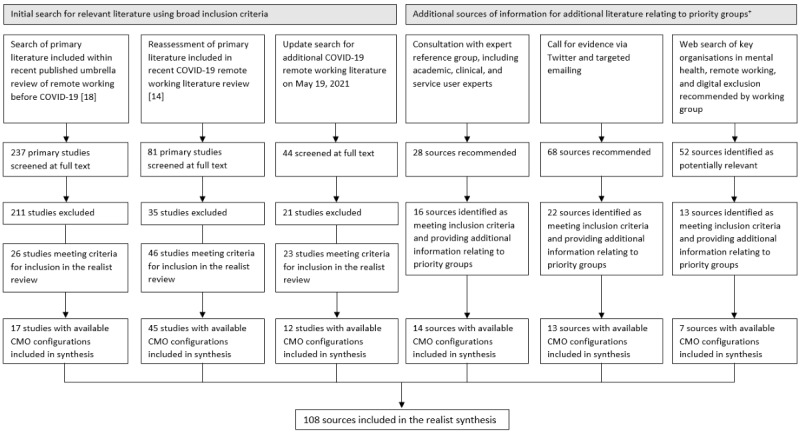

The search strategy was in accordance with PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (Figure 1) [34]. Resources and literature were identified through the sources described in the following paragraphs.

Figure 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) diagram. *Inpatient and crisis service users, children and young people, people who are digitally excluded, and items from a service user viewpoint [14,18]. CMO: context-mechanism-outcome.

First, we screened peer-reviewed studies included in 2 previous reviews on telemental health conducted by the MHPRU. The umbrella review by Barnett et al [18] included systematic reviews, realist reviews, and qualitative meta-syntheses on remote working before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic [18]. The systematic review by Appleton et al [14] synthesized primary research on the adoption and impacts of telemental health approaches during the pandemic [14]. An updated search of the latter review was conducted on May 19, 2021.

Second, we worked with our expert reference group to identify additional peer-reviewed and gray literature. Searches were conducted on the websites of relevant national and international voluntary and statutory organizations identified by the expert reference group and by internet searches (eg, Mind and the Royal College of Psychiatrists). Identified literature was noted on a shared Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. This process was supported using Slack, a web-based messaging application, to coordinate this complex and rapidly changing process.

Finally, the MHPRU disseminated a call for evidence via Twitter and email to relevant organizations and individuals (such as charities supporting digital inclusion, chief information officers, and telehealth leads within NHS Trusts) inviting them to submit relevant evidence, including evaluations, audits, surveys, stakeholder feedback, and testimonies from provider organizations and service user and carer groups.

Study Selection

References included in the umbrella and systematic review were downloaded and screened for inclusion in the RRR using EPPI-Reviewer (version 4.0) [35]. One of the reviewers screened abstracts and titles of the references identified through the updated searches of the umbrella review and systematic review. Full texts were reviewed for inclusion, with included and unsure sources checked by another reviewer. Sources were included in the final review if they met our inclusion criteria and provided relevant information for the development of CMO configurations. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with the wider research team.

Process of Data Extraction, Synthesis, and Interpretation

Data Extraction

The source characteristics were extracted and inputted on EPPI-Reviewer (version 4.0) [35]. Extracted characteristics included study aim and design (if applicable), type of service, telemental health modalities used, mental health diagnosis of service users, and staff occupation. MHPRU researchers screened each included source for information that could be assembled into CMO configurations related to telemental health (ie, information on contexts, outcomes, and underlying mechanisms). Underlying CMO configurations were extracted by MHPRU researchers and LEWG members. Underlying CMO extraction involved reading each source before identifying contexts, mechanisms, and outcome configurations that were either (1) identified by the authors in the paper or (2) identified by extractors by linking them together from the data, descriptions, and discussion in the paper. Each week, samples of the extracted CMO configurations were reviewed by the expert reference group to ensure coherence, relevance, validity, and format consistency.

Data Synthesis

The research team then began the process of synthesizing the underlying CMO configurations by reviewing the extracted CMO configurations and identifying emerging themes. We developed four domains to encapsulate key aspects of the evidence: (1) connecting effectively; (2) flexibility and personalization; (3) safety, privacy, and confidentiality; and (4) therapeutic quality and relationship. Each of the 4 identified domains was allocated to an MHPRU researcher to lead the synthesis, with input from LEWG members, clinicians, and MHPRU senior researchers.

To develop content for each of these 4 domains, underlying CMO configurations were, in essence, synthesized based on similarities to create a single overarching CMO (discussed in full detail in Multimedia Appendix 1). Underlying CMO configurations extracted from individual sources were reviewed in terms of their similarities and differences (eg, CMO configurations related to the convenience of telemental health) and then grouped together based on similar mechanisms (eg, flexibility, which reduces practical barriers to accessing mental health care) and outcomes (eg, increasing attendance and reducing missed appointments). Each similar group of underlying CMO configurations was then synthesized and refined to create a single overarching CMO, which reflected key content across the underlying CMO configurations, as well as input from the expert reference group. Each overarching CMO was assigned to 1 of the 4 domains.

Realist work does not conduct a traditional quality appraisal, as it values evidence from all sources in a nonhierarchical manner [27,29]. Our overarching CMO configurations were also significantly developed throughout the synthesis process based on stakeholder input, and thus, quality appraisal of individual study sources would not have reflected the quality of the final overarching CMO configurations.

Interpretation

An iterative process of revising and refining overarching CMO configurations from the perspective of stakeholder experience followed. Revisions, refinements, and additions were first made through discussion with the expert reference group. Summaries were then also discussed at three 2-hour stakeholder webinars, each focusing on one of our priority groups: children and young people, inpatient and crisis care services, and digitally excluded groups. The webinars were primarily attended by groups representing these constituencies and services who work with them, including experts and stakeholder representatives from research, policy, and clinical settings (nationally and internationally); the voluntary sector; lived experience groups and community organizations working with marginalized groups; and telehealth technology initiatives. There were between 30 and 40 participants at each webinar. During the webinars, participants were divided into breakout rooms, with a facilitator and a note taker from the core research team. High-level summaries of preliminary data were presented by domain, and attendees were asked to discuss the following questions: (1) whether the preliminary summaries captured their own knowledge and experience of telemental health, (2) whether the summaries applied to and how the summaries were relevant for the priority group at hand, and whether they were aware of any additional challenges or recommendations related to delivering telemental health to the priority group.

On the basis of the feedback from these webinars, the overarching CMO configurations within each of the 4 domains were then further revised and refined. We actively sought additional information related to each overarching CMO, including relevant contexts, further detail about mechanisms, real-life examples of strategies and solutions (such as for overcoming barriers identified within the CMO), and points of particular importance or concern, from the webinar notes, the expert reference group meetings, and related literature. We noted this information alongside the relevant overarching CMO and used it to refine the CMO configurations. In addition, we drew upon midrange theories (evidence-based theories derived from the wider literature) to provide more theoretically informed explanations of mechanisms (eg, the digital inverse care law [16], which theorizes that those most in need of care via telemental health are least likely to engage with it and existing inequalities will widen, helped to strengthen the mechanisms around digital exclusion). Throughout this process, the core research team and the expert reference group were iteratively consulted, and their feedback was integrated into the overarching CMO configurations. The revised theories were shared for a final email consultation with the stakeholders who were invited to our webinars. Their feedback was incorporated and resulted in the final overarching CMO models presented under each domain in this paper.

Results

Overview

Underlying CMO configurations were extracted from 17 studies included in the previous umbrella review [18] and from 45 studies included in the systematic review [14]. The updated search yielded 44 potentially relevant studies, of which 21 (48%) were excluded (either as they did not contain data on context, mechanisms, and outcomes or they added no additional information as data saturation had been reached). CMO configurations were extracted from 52% (12/23) of the remaining studies that met our inclusion criteria and were included in the realist synthesis. Through consultations with our expert reference group, we identified 28 sources, of which 16 (57%) met our inclusion criteria and provided additional information related to our priority groups, and 14 (50%) yielded CMO configurations that were included in the synthesis. We received 68 potential sources through the call for evidence, of which 22 (32%) met our inclusion criteria and provided relevant information on our priority groups; CMO configurations were extracted from 13 (19%) of these. Finally, website searches identified 52 potentially relevant sources, of which 13 (25%) met our inclusion criteria and 7 (13%) provided information relevant to CMO configurations. The realist synthesis includes a total of 108 sources.

Of the 108 included sources with primary data or detailed accounts of what works, for whom, and in what context, most were primary research studies (72/108, 66.7%), followed by service descriptions/evaluations/audits (19/108, 17.6%), guidance documents (4/108, 3.7%) and briefing papers (3/108, 2.8%), commentaries/editorials/discussions (4/108, 3.7%), and letters (2/108, 1.9%), as well as a review (1/108, 0.9%), news article (1/108, 0.9%), webpage (1/108, 0.9%), and a service user–led report (1/108, 0.9%). Of the 84 sources that included primary research data, 32 (38%) used quantitative methods, 19 (23%) used qualitative methods, and 33 (39%) used mixed methods (including n=2, 2% case studies).

Most sources were published in the United States (41/108, 38%) and the United Kingdom (34/108, 31.5%). The remaining sources collected data in Canada (7/108, 6.5%), the Dominican Republic (1/108, 0.9%), Australia (7/108, 6.5%), China (2/108, 1.9%), India (3/108, 2.8%), Egypt (1/108, 0.9%), and Nigeria (1/108, 0.9%), as well as 10 European countries, including Austria (1/108, 0.9%), France (1/108, 0.9%), Germany (1/108, 0.9%), Ireland (1/108, 0.9%), Italy (2/108, 1.9%), Netherlands (1/108, 0.9%), Portugal (1/108, 0.9%), Spain (1/108, 0.9%), Sweden (1/108, 0.9%), and Switzerland (1/108, 0.9%). Details of the included sources are presented in Multimedia Appendix 2 [12,19,24,36-153].

Overarching CMO configurations for each domain are summarized in Tables 1-4, and details of the underlying CMO configurations and summary notes on stakeholder discussions, which shaped the overarching CMO configurations, are presented in Multimedia Appendix 3 [12,19,24,36-153]. For each overarching CMO, we included examples of key contexts that are relevant for the CMO and examples of strategies and solutions addressing the challenges or opportunities identified in the CMO: these were drawn from underlying CMO configurations and stakeholder discussions. In the text outlining each domain, we also identify major midrange theories that elucidate mechanisms and outcomes for overarching CMO configurations.

Table 1.

Domain 1: Connecting Effectively.

| CMOa title | References | Overarching CMO | Key contexts | Example strategies and solutions | |

| CMO 1.1: Providing service users with access to digital devices | [19,39-49, 59] | When service users who do not have access to digital devices are given access to up-to-date devices (and chargers), paid for or loaned to them (context), this results in improved access to and implementation of telemental health services (especially via video platforms; outcome 1), some inequalities in accessing a digital device are addressed (outcome 2), exacerbation of existing inequalities is less likely (outcome 3), and service users are more able to maintain personal contact with family and friends if they wish and access a range of web-based services (outcome 4), as this reduces the burden of having to purchase a device for the service users and provides more financially viable access to devices required for web-based connections (mechanism). | Lack of access to devices particularly affects people living in poverty or unstable living circumstances (such as homeless people or refugees), as well as other groups at risk of exclusion not only from telemental health but from a range of services and networks (such as people who are cognitively impaired or with psychosis or substance abuse disorders). It can also particularly affect inpatients, who may not have access to devices or charging facilities or both on the ward, and children and young people, who may not have access to their own devices. |

|

|

| CMO 1.2: Lack of access to stable, secure, and adequate internet connection | |||||

|

|

Staff | [19, 39, 41, 42, 44, 47, 50-60] | When the staff deliver telemental health via video from workplaces or homes with an unstable and poor internet connection (context), teleconsultations are difficult (or impossible) to conduct with service users (outcome 1), fewer teleconsultations are conducted (outcome 2), and telemental health is viewed less positively (outcome 3), as staff experience frustration, and there is reduced motivation to arrange web-based appointments (mechanism). | This is particularly relevant for staff working within health care providers that frequently have insufficient Wi-Fi or internet connection to deliver sessions smoothly. It also affects staff who do not have adequate Wi-Fi connectivity in their own homes or when working in the community. |

|

|

|

Service users | [19, 39, 41, 42, 44, 47, 50-60] | When service users only have access to an insecure, unstable, and poor-quality internet connection or consistent technological problems (context), it is difficult for telemental health to be viewed positively (outcome 1), they are able or willing to accept fewer web-based consultations (outcome 2), they may continue to struggle with their mental health (if face-to-face consultations are unavailable; outcome 3), and this may result in digital exclusion that could exacerbate existing inequalities (outcome 4), as the service users struggle to engage in sessions with sufficient clarity and mutual comprehension and experience frustration (mechanism). | This is especially relevant for service users on low incomes or from socially marginalized groups (such as homeless people), those living in multiple occupancy households where Wi-Fi is overstretched, and people from low-to-middle income countries. Lack of access to reliable internet or even electricity also differentially affects people in rural and remote areas. People in marginalized groups may also lack the means to pay for a telephone service. |

|

| CMO 1.3: Benefits of providing support and guidance for using technology | |||||

|

|

Staff | [19, 24, 38, 42-44, 46, 53, 59, 61-75] | When staff who lack the confidence or knowledge to deliver mental health care online (particularly via video calls) receive practical instruction and guidance on how to use technology to deliver mental health services (including clear information about how to operate within local policies, procedures, and platforms; troubleshoot issues during telemental health sessions; and formulate and implement backup plans; context), they feel an increased sense of confidence in managing and delivering telemental health services (mechanism), which leads to increased use of telemental health services (outcome 1) and fewer delays, resulting in more appointments being completed on time (outcome 2). | This is especially relevant for staff who are new to delivering mental health care remotely or who are unclear or unfamiliar with using locally recommended platforms and procedures. |

|

|

|

Service users | [19, 24, 38, 42-44, 46, 53, 61-75] | When service users with access to a technology device who struggle with the confidence, knowledge, or the ability to use telemental health receive guidance, reassurance, and instruction (tailored to their health care provider and their language, reading ability, and any sensory disability) on how to use technology (particularly video calls) to access mental health care, engage with backup plans, and receive timely technical support and troubleshooting during treatment sessions (context), they feel an increased sense of confidence in accessing telemental health (mechanism), which reduces anxiety in using telemental health and digital technologies (including in their personal lives; outcome 1), facilitates the adoption of and adherence to telemental health (outcome 2), improves service users’ ability to adjust to remote care (outcome 3), reduces interruptions in care delivered via telemental health (outcome 4), and increases satisfaction with telemental health (outcome 5). | Receiving guidance tailored to local policies and procedures for telemental health access is relevant to all service users. It is likely to be particularly relevant to groups identified as at high risk of digital exclusion through lack of confidence in using technology, including older people, people with severe mental health problems, and people with intellectual disabilities or cognitive impairments. Production of accessible guidance is especially relevant for people with cognitive impairments or intellectual disabilities, children, people with sensory disabilities, and people who do not understand English well. |

|

| CMO 1.4: Impact of technology-related disruptions | [36, 45, 56, 76-82] | When technological issues (including connection problems and device issues) lead to disruptions in web-based sessions and there is no prearranged backup method of contact (eg, a plan to connect by telephone instead of video call if needed; context), the quality of the intervention is diminished (outcome 1), there is a loss of empathic connection between client and therapist (outcome 2), and the sessions may not be able to continue (outcome 3), as the flow of the conversation is interrupted and session time reduced, for example, when having to ask the other person to repeat what has been said or when cut off completely, leaving staff and service users potentially feeling distracted, frustrated, awkward, and upset (particularly if there is a threat of therapy withdrawal because of missed sessions; mechanism). | This is particularly relevant for the use of videoconferencing, where phone backup can reduce the risk of abandoning appointments because of failure to make a stable connection. |

|

|

| CMO 1.5: Preparing service users for telemental health | [83-85] | When staff prepare service users for telemental health appointments and communicate clearly with service users about what to expect (context), this leads to more accepted calls and fewer missed service user contacts (outcome), as service users have more relevant knowledge of the process, including when to expect contacts and from what number, and feel more comfortable engaging with telemental health services (mechanism). | This is relevant across telemental health contexts but may be particularly relevant for service users who have not used telemental health before or are anxious or worried about telemental health. |

|

|

| CMO 1.6: Service users’ familiarity with the platform and ease of use | [41,66,86-90] | Where service users already use remote technologies for social, educational, or work purposes, or where the web-based platforms are relatively easy to use (context), offering a choice of familiar and accessible technology platforms that may be less difficult and time-consuming for staff and service users to understand or learn (mechanism) may increase the likelihood of engagement with services via telemental health, especially video calls (outcome). | This is especially relevant to service users who are already making some use of technology, for example, for social, educational, or work purposes. |

|

|

| CMO 1.7: Telemental health may be a better alternative to receiving no care for service users during an emergency, such as the COVID-19 pandemic | [36, 43, 60, 90-92] | When service users are offered telemental health appointments as face-to-face appointments are restricted (eg, because of COVID-19 or another emergency; context); these appointments are likely to be accepted by some service users on the basis that they are the main way by which mental health care can continue (outcome 1), and there is a reduced risk of infection from COVID-19 (outcome 2), as telemental health is seen as preferable to receiving no support at all and as an alternative to canceling appointments entirely (mechanism). | This is applicable across mental health services in the context of any emergency which restricts face-to-face meetings, especially in services where all face-to-face contacts have been discontinued or where they are limited to immediate crises. It is especially relevant for service users who need to self-isolate because of high personal risk, or where clinicians need to self-isolate after contact with others. |

|

|

aCMO: context-mechanism-outcome.

Table 4.

Domain 4: Therapeutic quality and relationship.

| CMOa title | References | Overarching CMO | Key contexts | Example strategies and solutions | |

| CMO 4.1: Change in nonverbal cues and informal chat, affecting the therapeutic relationship | [12, 19, 24, 36, 37, 40, 45, 49, 54, 55, 60, 67, 76, 77, 79, 81, 90-92, 96, 103, 137 - 142] | When switching from face-to-face to telemental health care (context), staff and some service users perceived the relationship between staff and service users (and other service user group members) to be negatively affected or found it more difficult to develop a therapeutic relationship (outcome 1) and, thus, were less willing to take up or use telemental health (outcome 2), more likely to be dissatisfied (outcome 3), and viewed care as less effective compared with previously received face-to-face care (outcome 4). This was because they perceived telemental health to be impersonal and found it more difficult to discuss personal information because of a lack of nonverbal feedback, eye contact, and social cues, as well as informal chat before, after, and during sessions (mechanism). | This may be relevant during rapid switches to telemental health because of emergency situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic in which staff training and structured telemental health implementation are limited because of time constraints; for staff with limited training and experience generally and those with limited experience of using telemental health specifically, who may lack the confidence to navigate the change in visual cues, which, in turn, can affect the therapeutic relationship; for staff and service users who are new to a specific service, staff/service user, or to mental health care generally; for service users who are apprehensive of technology use or who are concerned about the violation of their privacy; and in telemental health group sessions in which the flow of conversation is affected or people find it less easy to establish relationships and be at ease with the whole group. |

|

|

| CMO 4.2: Assessment via telemental health versus face-to-face (staff) | [40, 82, 92, 111, 121, 133, 137, 138, 143 - 145] | When using telemental health for assessments (context), staff report finding it more difficult to assess mental health problems, care needs, and risk, and make diagnoses (outcome), as they are less able to observe nonverbal and visual cues (depending on the telemental health modality used), and some service users may find it more difficult to have in-depth conversations about their problems and experiences (mechanism). | Cues can include extrapyramidal symptoms from antipsychotics, hygiene, gait, direct eye contact, mannerism, and linguistic nuances. Conducting assessments might be particularly difficult over the phone because of the lack of visual cues; with service users who experience domestic violence and abuse and thus cannot be honest about their well-being and current situation in the presence of their abuser; with young children; with service users who find it difficult to speak directly about their difficulties and experiences; and when the staff make incorrect assumptions about service users’ mental states based on behavioral indicators and without considering service user reports, especially of neurodivergent service users. |

|

|

| CMO 4.3: Staff support and training | [49, 63, 102, 146] | When staff receive specific instructions and training, for example, on how to build rapport using telemental health and support from colleagues with prior telemental health experience (context), it facilitates quality of care (outcome 1), building therapeutic relationships (outcome 2), and increased engagement (outcome 3), as staff are able to ask questions and acquire new skills and knowledge about the interventions and thus build confidence in delivering telemental health (mechanism). | This is likely to be especially relevant to staff who have little or no previous experience of delivering telemental health. |

|

|

| CMO 4.4: Service users who find it easier to establish a therapeutic relationship | |||||

|

|

On the web | [39, 60, 79, 96, 99, 119, 136, 137, 147, 148] | When delivering telemental health to some services users who feel uncomfortable in clinical settings and social situations (context), these service users find it easier to build a therapeutic relationship and are more willing to use telemental health (outcome), as they feel safer, are more relaxed and less anxious being in their own environment or outside of clinical settings and in-person social situations, or both, and, thus, feel more empowered and comfortable to open up and speak freely (mechanism). | This may be especially relevant for some children and young people, including those with special needs and neurodivergent children, who find clinical settings and having to travel upsetting, and some service users with social anxiety. However, it is important that using telemental health does not reinforce potentially detrimental safety behaviors that may maintain and potentially exacerbate their social anxiety. |

|

|

|

Via video versus phone | [24, 36, 50, 52, 55, 78, 105] | When service users and staff who prefer video calls use them (instead of telephone calls or text-based chats) for telemental health (context), it can facilitate a stronger therapeutic relationship (outcome 1), satisfaction (outcome 2), and engagement (outcome 3), as it is easier to see visual and nonverbal cues, gauge the therapist’s reaction, and connect with the service user/staff member than with other telemental health modalities (mechanism). | This applies to service users across age groups and may be especially the case for new service users. |

|

|

|

Via the phone versus face-to-face or video calls | [50, 65, 80, 111] | When services offer phone calls and SMS text messages instead of video calls (context), some service users are more satisfied with their care (outcome) as they do not have to sit still and see themselves on screen, are less conscious of their body language and facial gestures, are less distracted by the clinician’s nonverbal cues, are able to move around freely, and are thus less inhibited and able to open up more quickly (mechanism). | This might be especially relevant for service users who are neurodivergent, socially anxious, and self-conscious about their appearance. |

|

| CMO 4.5: More frequent telemental health sessions plus SMS text messages | [39, 40, 99, 104, 149] | When services adapt flexibly to service users’ preferences regarding the pattern and frequency of telemental health sessions, including offering more frequent, shorter rather than infrequent, long sessions, and additional asynchronous SMS text messages and calls to check in between sessions (context), it may lead to stronger therapeutic relationships (outcome 1), increased engagement (outcome 2), and improved quality of care (outcome 3), as service users receive regular and more frequent support depending on their preference (mechanism). | Lack of a need to travel means that more frequent shorter sessions may be particularly feasible with telemental health: they are potentially less tiring and thus might better maintain concentration and engagement, especially for children. Frequent sessions might help new service users to build trust and reduce anxiety around the treatment. Frequent sessions may also help support and monitor less stable service users, for example, following a crisis. |

|

|

| CMO 4.6: Enhancing the quality of care through the use of telemental health enhancements | [24, 74, 101, 150-152] | When clinicians make appropriate and personalized use of enhancements and extensions of telemental health (such as using chat, voice activation to instruct phones, SMS text messaging and other text-based messaging, web-based appointment schedules, screen sharing, and apps accessed during sessions; context); it can lead to success engaging in telemental health (outcome 1) and broadening the range of strategies and interventions available during clinical meetings (outcome 2), as these features make engaging with services easier and provide a functional method useful for exchanging practical information, such as reminding service users about the date and purpose of an appointment, with less room for ambiguity and more creative methods of engagement (mechanism). | Additional telemental health features might be particularly helpful for young children (who overall find it difficult to engage on the web). Adolescents who experience social anxiety or are autistic may benefit from and prefer the chat function. |

|

|

| CMO 4.7: Staff well-being and quality of care | [51-53, 80, 88, 91, 101, 107, 112, 153] | When the staff use the time saved on travel to take breaks in between telemental health sessions (context), it may increase staff well-being (outcome 1) and improve quality of care (outcome 2), as it provides the opportunity to reflect and recharge after telemental health sessions, which are often experienced as tiring and thus reduces fatigue, tension, and anxiety among staff (mechanism 1), and staff can use some of the time on clinical work, catch up on administrative tasks, or engage in professional developmental activities (mechanism 2). | This may be relevant for clinicians who can work wholly or partly at home and teams working across different sites or who visit service users at home or in other community settings. |

|

|

aCMO: context-mechanism-outcome.

Domain 1: Connecting Effectively

The content of this domain relates to establishing a good web-based connection to join a video call of sufficient quality or to engage in telemental health via phone or message, with a particular focus on digital exclusion. Table 1 outlines 7 overarching CMO configurations identified in relation to this domain, addressing issues concerning device and internet access (CMO 1.1 and CMO 1.2), technology training (CMO 1.3), the impact of preparation and technological disruptions (CMO 1.4 and CMO 1.5), the familiarity and usability of the platforms (CMO 1.6), and the acceptability of telemental health as an alternative to receiving no care during emergency situations (CMO 1.7). Three of the CMO configurations were related to trying to resolve three main challenges: (1) access to a charged, up-to-date device that enables internet access (CMO 1.1); (2) an internet (Wi-Fi or data) or signal connection (CMO 1.2); and (3) the knowledge, ability, and confidence to engage on the web (CMO 1.3). Much of the content relates to challenges service users encounter in engaging with telemental health; however, the literature and stakeholder discussion also yielded significant challenges for staff and service providers in the practicalities of connecting on the web.

Theories regarding the relationship between digital exclusion and other forms of exclusion and deprivation, as well as the potential of digital exclusion to amplify inequalities, contribute to our understanding of key mechanisms and outcomes in this domain. Widening inequalities have been described as an inevitable consequence of the expansion of the role of technology in health care, with loss of access to community facilities, such as libraries, making this a still greater risk during the pandemic [154]. The “digital inverse care law” [16] describes a tendency for groups in most need of care (eg, older people or people experiencing social deprivation) to be least likely to engage with technological forms of health care. This is highly salient in mental health care, given the strong associations between experiencing mental health challenges and experiencing one or, often, many forms of disadvantage [154].

Access to devices (CMO 1.1) is a contributor to digital exclusion, and groups who are especially likely to be affected include homeless individuals and people living in poverty, those receiving inpatient or crisis care, and young children who may not have their own devices. The type of device may be important for accessing telemental health. For example, smartphones may be less suitable for video therapy because of their small screens [155], although this may be less relevant for young people who are familiar with and consistently use smartphones for connecting on the web [156]. This raises future research questions around which types of digital devices work for whom and in what context when it comes to continuing telemental health treatment. It may also have implications for the provision of suitable equipment to certain populations.

Our consultations and the wider literature revealed that lack of access to good quality Wi-Fi, including poor Wi-Fi in hospitals and offices, was a further key barrier to the successful and equitable delivery of telemental health (CMO 1.2). It was emphasized that modernization of software and hardware, particularly within the NHS, is needed in many health care sites to allow for the requirements of telemental health. Service users also reported relying on their own mobile phone data to connect to telemental health services, often depleting their data completely after or during just one video call or consultation, which is expensive to replenish and may also deter engagement. This could amplify existing inequalities, leaving some service users at risk of digital exclusion and unable to access the internet and mental health support. Disruptions to telemental health appointments because of poor connections are a significant barrier to engagement (CMO 1.4). Our consultations and the existing literature highlighted the importance of having an alternate form of communication (eg, a telephone call) as a backup plan in case of a technology or connection failure [36,37,157,158].

We identified the importance of technology training and sustained formal and informal support for service users (CMO 1.3). Variations in the ability to use telemental health are likely to disproportionately affect certain service user populations, often groups who also experience high levels of need for mental health care and inequalities in its provision. This includes people living in deprived circumstances, people with cognitive difficulties, people with paranoia, or those who do not speak the same language as service providers. Understanding how to use technology is also important for service users’ social engagement and connection, which is relevant for wider recovery and citizenship [159-161]. Young children may also be disproportionately affected as they may not be able to resolve difficulties they experience during telemental health sessions without the help of their parents or other supporters.

For staff (CMO 1.3), our evidence suggests that staff training provided more widely and accessibly on using technology for telehealth would be helpful to ensure high-quality service provision and overcome barriers around staff not having time allocated to training or being reluctant to ask for support. Evidence suggests that there are also benefits of having access to technical support to troubleshoot issues during sessions [38], as well as of practicing new skills and learning with colleagues and peers [162].

The importance of the familiarity and usability of platforms was highlighted throughout our stakeholder consultations and weekly reference group meetings, as well as in the published literature (CMO 1.6), in keeping with previous research on the acceptability of telemedicine by service users [163]. Many of the platforms and devices commonly used for telemental health services, for example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, were not designed for use in health care settings and, therefore, may be less user-friendly. The importance of usability is emphasized by Nielsen and Landauer [164]; 3 of 5 main usability attributes of a program are that it should be easy to learn, efficient to use, and easy to remember. This is in keeping with our findings related to familiarity and usability in telemental health.

Finally, preparing service users for telemental health sessions was key (CMO 1.5). This was relevant across telemental health contexts; however, information tailored to individual communication needs may be especially helpful for service users who may experience additional challenges connecting on the web (eg, those who are inexperienced with technology or anxious about using telemental health, young children, older people, and people with cognitive difficulties). For people with significant sensory impairments, specialist adaptations will need to be available if telemental health is to be a viable modality (eg, mobile phones that flash when receiving a call or providing guidance in Braille or sign languages).

Domain 2: Flexibility and Personalization

Table 2 presents the CMO configurations, key contexts, and example strategies and solutions for the domain of flexibility and personalization. The need for flexibility and personalization was a key theme identified in both the literature and stakeholder consultations when considering using telemental health in place of (or in conjunction with) face-to-face mental health support. A total of eight overarching CMO configurations were identified in this domain, which can be divided into three main categories: taking individual preferences into account (CMO 2.1, CMO 2.5, and CMO 2.7), convenience (CMO 2.2), and allowing for more collaborative and potentially specialized care (eg, involving specialists, family, or friends in care; CMO 2.3, CMO 2.4, CMO 2.6, and CMO 2.8).

Table 2.

Domain 2: Flexibility and personalization.

| CMOa title | References | Overarching CMO | Key contexts | Example strategies and solutions |

| CMO 2.1: Taking service users’ individual preferences into account—offering alternatives | [24, 36, 48, 50, 65, 67, 75, 77, 90, 91, 93-104, Eagle et al (email, August 31, 2022)] | When services using remote mental health care allow service users to choose the modality of telemental health and a choice of remote versus face-to-face care and regularly check their preferences (context), this allows service users to have greater autonomy and choice (mechanism), leading to them feeling more satisfied and able to engage with the type of care received (outcome 1), leading to improved uptake (outcome 2) and improved therapeutic relationships with their clinician (outcome 3). | Allowing service user choice and delivering services flexibly is a key principle across settings and populations, with the overall aim that care of equivalent quality should be available in a timely way whatever modality is chosen. Hybrid care, with a flexible mixture of face-to-face and telemental health care based on the purpose or function of appointment (eg, prescription review versus the first visit to see a clinician), preference, and circumstances, is especially relevant to service users receiving relatively complex care with multiple types of appointments, for example, from multidisciplinary community teams. Children and young people may particularly benefit from being offered a choice as it increases their feelings of autonomy and improves engagement in care. |

|

| CMO 2.2: Removing barriers—greater convenience for service users and family/friends | [19, 24, 36, 38, 40, 42, 45, 54, 55, 67, 70, 75, 76, 79, 81, 82, 84, 90-92, 95, 97, 105-112] | Among some service users, family, and other supporters experiencing specific practical barriers to attending face-to-face services (childcare or other caring responsibilities; location, work, and mobility limitations; travel difficulties/costs, and work commitments) and those who have good access to telemental health (context), telemental health may provide increased flexibility that addresses individual practical barriers (mechanism), which can lead to telemental health being viewed by some service users and carers as more convenient and accessible than face-to-face care (outcome 1), easing attendance (outcome 2), increasing uptake (outcome 3), and reducing missed appointments (outcome 4). | This may be relevant for parents with young children, people with caring responsibilities, and people who struggle to travel because of work commitments/disability/costs; children and young people in school or higher education (so they can access mental health care without having to leave their place of education); people who live in remote areas or a long distance away from a specialist service; and people for whom travel is challenging because of impaired mobility or sensory impairments or mental health difficulties such as agoraphobia. There may be more advantages to treatments that involve the support of family and friends. |

|

| CMO 2.3: Involvement and support for family and friends | [79, 91, 113-115] | When family and other supporters are invited (with service user agreement) to join telemental health sessions (context), this may result in more holistic treatment planning and greater engagement of family and others in supporting service users (outcome 1); may help improve therapeutic relationships and treatment success (outcome 2), increase engagement (outcome 3), and reduce some uncertainty and anxiety around treatment (outcome 4); and may increase the satisfaction of and support for family and friends (outcome 5), as family and other supporters may be able to participate in care planning meetings and assessments that they would have found difficult to attend face-to-face, increasing their engagement in supporting service users and their understanding of their difficulties and care plans (mechanism). | This is especially helpful for those living in locations different from their family and friends or where family and friends have caring or work commitments preventing them from attending meetings face-to-face, children and young people (as this may allow their parents to be more involved in their care), and service users in inpatient settings where family and friends cannot visit (eg, because of epidemic-related restrictions) or as the hospital is in a remote location. |

|

| CMO 2.4: Widening the range of available mental health services and treatments for service users via telemental health | [49, 116-118] | For service users who may benefit from services that they cannot readily access locally and that provide specialized forms of treatment and support regionally or nationally (context), telemental health can widen the range of specialist assessment, treatment, and support available (mechanism), which potentially leads to improved access to services tailored to individual needs and culturally appropriate or specialist services (outcome 1) and improved satisfaction and treatment outcomes (outcome 2), although an impoverished range of local face-to-face provision may be a risk if referral to distant specialist care via telemental health becomes routine (outcome 3). | People to whom this is relevant may include people who have complex clinical needs or rarer conditions such that they would potentially benefit from assessment, treatment, and support from specialist services provided at regional and national rather than local levels; people who may be able to access distant therapists who speak their own language or interpreters of rare languages not available locally; people who would benefit from support from voluntary organizations that meet specific needs that are not catered for locally (eg, that support particular cultural groups; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer groups; or people with sensory impairments); and people who would benefit from a wider choice of therapies and support (including peer support) than is available locally. |

|

| CMO 2.5: Adaptations for service users with sensory or psychological barriers to telemental health | [40, 50, 77, 119] | Offering face-to-face (or telephone) appointments to people who struggle to cope with sensory (visual or auditory) aspects of telemental health or have symptoms that are exacerbated by it (context) may help to improve engagement with mental health care (outcome) as the adverse effects of the switch to telemental health for these symptoms and sensory or cognitive impairments may be avoided and service users are able to access their preferred modality of care (mechanism). | This may be relevant for people with symptoms that may interfere with or be exacerbated by engaging with telemental health, such as persecutory ideas or hearing voices; autism; sensory or cognitive impairments; and migraines. |

|

| CMO 2.6: Inclusion of multidisciplinary and interagency teams in service users’ care | [89,115] | When mental health consultations are conducted using telemental health (context), it enables the inclusion of staff in appointments who are based geographically far away or who have schedules that would not have allowed them to join a face-to-face session (outcome 1), meaning care and support has potential to be more holistic and integrated (outcome 2), as it is possible for staff from different services and sectors to provide perspectives and contribute to plans (mechanism). | Key contexts include hospital inpatients, where telemental health may enable staff who work with them in community settings to join reviews and ward rounds (especially in pandemic conditions where they cannot attend in person), and people with complex treatment and support, who are receiving support from >1 team or sector. |

|

| CMO 2.7: Continuing to offer face-to-face care to service users | [53, 81, 92, 116, 120] | When service providers offer care of equivalent quality and timeliness face-to-face (including home visits where needed) rather than via telemental health to service users who do not wish or do not feel able to receive their care remotely (context), it ensures that care can continue and that inequalities in provision are not created or exacerbated (outcome), as it provides a choice to service users and avoids the negative impacts of digital exclusion (mechanism). | People for whom face-to-face options may be preferable, and choice is especially important, include those who do not have access to private spaces, live with people they do not wish to be overheard by in their appointments (including perpetrators of domestic abuse), do not feel comfortable communicating via remote means, and do not want therapy to intrude on their private lives should be included. In addition, some service users who value the time spent traveling to and from face-to-face appointments to process emotions may find face-to-face options particularly useful. |

|

| CMO 2.8: Communication between staff | [19, 85, 121] | When remote technology platforms are used to facilitate real-time communication between staff members, including managers or clinicians working in different teams (context), it can lead to improved efficiency, more convenient working and staff management (outcome 1), improved communication and collaborative planning (outcome 2), and process improvement opportunities (outcome 3), as staff have the ability to rapidly share information, keep track of evolving telemental health procedures (eg, during emergencies), and make collaborative decisions (mechanism). | Contexts in which this is relevant include multidisciplinary teams who are not working on the same site; complex provider organizations with management teams and clinicians working on multiple sites; situations in which people may be receiving care from multiple teams, for example, from an inpatient or crisis service, as well as a continuing care service. |

|

aCMO: context-mechanism-outcome.

Our findings emphasize the importance of taking individual service user preferences into account when deciding whether to make use of telemental health, in selecting the modality of digital communication used (including the type of technology platform), and in decisions about involving others (clinicians or family members) in care. This finding underpins all other CMO configurations in this theme and coheres with theories regarding the importance of shared decision-making, collaborative care planning, and personalization in mental health care [165-167]. Involving service users and carers in decisions and care planning as part of a collaborative approach to mental health care has been identified as central to best practice [168]; for example, a review of collaborative care for depression and anxiety found this approach to be more effective than usual care in improving treatment outcomes [169].

Flexible use of telemental health was also identified as being beneficial in reducing barriers to accessing mental health support for some service users, particularly those who may struggle to access face-to-face services for reasons such as caring or work commitments, problems traveling (eg, because of a physical disability, anxiety, or lack of transport) or a reluctance to attend the stigmatizing places. Telemental health can also facilitate connections between clinicians, especially across different services or specialties, which can improve multidisciplinary working and collaboration across teams and agencies and provide service users with a wider range of specialists or support for specific groups. This approach has been identified as having salience in a mental health setting [170-172]. In some cases, telemental health was viewed by both service users and clinicians as more convenient, as it reduced the need for (and cost of) traveling to face-to-face appointments.

Telemental health was also seen as an important tool in inpatient wards, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic when visiting was restricted, as it allowed service users to stay in touch with family and friends and for them to be involved in their care. It also allowed staff supporting inpatients in the community to remain involved.

However, instances were identified where telemental health was not appropriate, and face-to-face care needs to be available. For example, some service users do not wish or feel able to receive care by remote means or do not wish to have all appointments by this means, whereas others may struggle with telemental health because of sensory or psychological factors or a lack of access to appropriate technology and internet connectivity.

Domain 3: Safety, Privacy, and Confidentiality

Table 3 presents the four overarching CMO configurations, key contexts, and example strategies and solutions for the domain of safety, privacy, and confidentiality. Key messages were the importance of ensuring the availability of a private space for both service users and clinicians (CMO 3.1), the potential for telemental health to provide privacy to some service users experiencing stigma (CMO 3.2), the importance of considering how to manage risk when using telemental health and the limits to how far this is possible (CMO 3.3), and data security and staff training (CMO 3.4).

Table 3.

Domain 3: Safety, privacy, and confidentiality.

| CMOa title | References | Overarching CMO | Key contexts | Example strategies and solutions |

| CMO 3.1: Lack of privacy | [39, 42, 45, 48, 54, 55, 58, 60, 77, 79-82, 90, 91, 97, 101, 102, 104, 111, 120, 122-127] | When accessing telemental health sessions without access to a private space or secure private connection (context), service users and staff are at an increased risk of being overheard (mechanism 1), potentially leading to breaches of privacy and confidentiality (outcome 1), risk of harm to those in unsafe domestic situations (outcome 2), and reluctance to speak openly about sensitive topics (outcome 3). It may also cause some service users to experience frustration, distress, and anxiety (mechanism 2), leading to impacts on service user engagement and interactions (outcome 4) and reduced willingness to use telemental health and continue therapy (outcome 5). | Issues related to lack of privacy at home are especially relevant for young people who are distracted by their home environment, may not feel safe in their own home, or have siblings/parents/other family members unexpectedly appearing in the room; parents with children at home; those experiencing domestic abuse who are not able to be honest about symptoms, risk, or violence experienced; people who may be living with/caring for extended family or in households that are crowded; inpatients who may not have a space where they feel psychologically safe; people living in houses of multiple occupation; staff members who are not able to work in a private environment when providing remote therapy; and service users who experience cultural stigma in the home from their families relating to their mental health. |

|

| CMO 3.2: Privacy, anonymity, and reduced stigma (service users) | [40, 43, 92, 103, 105, 128-131] | For some service users who feel stigmatized when attending a mental health service in person and who have access to a private and secure space to receive therapy remotely (context), being provided with the option of telemental health as an alternative means there is an option to receive care with more anonymity (mechanism), which helps ensure their privacy and safety (outcome 1), thereby increasing the accessibility of services (outcome 2). | Some groups may be more likely to feel there is a stigma associated with attending mental health premises or reluctant to have contact with others doing so, for example, young people not previously in contact with services. |

|

| CMO 3.3: Managing risk | [24, 43, 85, 91, 111, 112, 119, 124, 132-136] | When services incorporate tailored risk management procedures in the delivery of remote care (context), it encourages consideration of the risks associated with remote care specific to each individual, including the risk of self-harm or suicide and risk from others in situations of domestic abuse, and ensures the staff are aware of the procedures to try to assess and respond to risk or safeguarding concerns despite challenges associated with remote care (mechanism), which has the potential to improve the safety and well-being of service users and others (outcome 1). However, a disadvantage of telemental health is that real-time risk assessment limits an immediate response to be organized when someone is at imminent risk of harm and some distance away (outcome 2). | This may be relevant to people who are currently unwell or in a crisis, situations where someone is remote from the assessing clinician or at a location unknown to them, situations where technological difficulties occur during an assessment of someone who is at high risk, people with eating disorders or who are physically unwell and where there are practical impediments to assessing risk remotely, and when a service user suddenly exits during a telemental health consultation and it is not clear why. In substance misuse services, it may be harder to detect whether someone is under the influence of drugs or alcohol. |

|

| CMO 3.4: Technological support and information security | [85] | When services provide technology support, software with appropriate security, and devices (including mobile phones and headphones) to staff specifically for work use (context), it helps ensure privacy and confidentiality for both service users and staff (outcome), as staff can store information securely on devices that are not shared with others (mechanism 1) and are able to ensure that service users are aware of when they will have access to their work devices (mechanism 2). | This may be relevant in services where staff share office space and devices, or where a shortage of devices may lead to the use of personal devices, for example, for home working; when balancing service user preference with risk from using less secure software or software with which the staff are less familiar; where software has a particular set of settings that must be enabled to ensure secure, private connections. |

|

aCMO: context-mechanism-outcome.

With the most supporting literature, CMO 3.1 highlights the need for appropriate private space to receive telemental health and that many service users may not have consistent access to such a space. As a lack of privacy can risk breaches in confidentiality and safety for some, a key message was that alternatives such as face-to-face modalities or alternative times/locations to receive telemental health should be provided. The importance of privacy for effective mental health care has been frequently cited in the literature and is likely to be especially important in ensuring high-quality telemental health [91]. Although some literature indicated that some service users feel an increased sense of privacy and a reduction in stigma when not having to attend mental health clinics in person (CMO 3.2), a key message lies in providing a choice so that each individual can work with their clinicians to find ways of receiving care that they are happy with, a message highlighted in CMO configurations throughout this paper.