Abstract

Background:

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) comprise a large class of chemicals with widespread use and persistence in the environment and in humans; however, most of the epidemiology research has focused on a small subset.

Objectives:

The aim of this systematic evidence map (SEM) is to summarize the epidemiology evidence on approximately 150 lesser studied PFAS prioritized by the EPA for tiered toxicity testing, facilitating interpretation of those results as well as identification of priorities for risk assessment and data gaps for future research.

Methods:

The Populations, Exposure, Comparators, and Outcomes (PECO) criteria were intentionally broad to identify studies of any health effects in humans with information on associations with exposure to the identified PFAS. Systematic review methods were used to search for literature that was screened using machine-learning software and manual review. Studies meeting the PECO criteria underwent quantitative data extraction and evaluation for risk of bias and sensitivity using the Integrated Risk Information System approach.

Results:

193 epidemiology studies were identified, which included information on 15 of the PFAS of interest. The most commonly studied health effect categories were metabolic (), endocrine (), cardiovascular (30), female reproductive (), developmental (), immune (), nervous (), male reproductive (), cancer (), and urinary () effects. In study evaluation, 120 (62%) studies were considered High/Medium confidence for at least one outcome.

Discussion:

Most of the PFAS in this SEM have little to no epidemiology data available to inform evaluation of potential health effects. Although exposure to the 15 PFAS that had data was fairly low in most studies, these less-studied PFAS may be used as replacements for “legacy” PFAS, leading to potentially greater exposure. It is impractical to generate epidemiology evidence to fill the existing gaps for all potentially relevant PFAS. This SEM highlights some of the important research gaps that currently exist. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP11185

Introduction

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) comprise a class of chemicals with widespread use and persistence in the environment and in humans. Exposure to PFAS is ubiquitous, with nearly all humans having measurable levels in their blood.1 Exposures to some PFAS have been associated with a wide variety of health effects, including immune suppression, high cholesterol, liver toxicity, fetal growth restriction, and certain types of cancer.2 Certain PFAS, such as perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), have been phased out of production (“legacy” PFAS) in some countries, including the United States.3 However, products containing these PFAS can continue to be imported, and such PFAS are known as “forever chemicals” for a reason—their persistence in the environment means there is ongoing exposure and continued need for monitoring and, potentially, regulation to protect human health. Other PFAS, of which there are more than 9,000,4 are still being identified and may be used as replacements for these “legacy” PFAS chemicals.5,6 However much of the epidemiological research to date has focused on a small subset of PFAS, with well over 500 publications on health effects of exposure to PFOA and PFOS, and between 200 and 400 for perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA), perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS), and perfluorodecanoic acid (PFDA). These well-studied PFAS have also been the subject of numerous chemical assessments and regulatory attention.7–10 Much less information is available on the health effects associated with exposure to other PFAS.

As part of a broader effort to characterize the evidence of health effects associated with exposure to less-studied PFAS, we created a systematic evidence map (SEM) of epidemiology studies of the approximately 150 less-studied PFAS prioritized by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) for tiered toxicity testing.11 This SEM is an extension of another recently published SEM of these PFAS,12 which presented detailed data on animal toxicology studies but only high-level summary study design characteristics (e.g., population, study design, and health effect categories) for epidemiology studies. This SEM uses the same literature search and screen results but adds to the previous analysis with full data extraction and study evaluation of the identified epidemiology studies, allowing the user to access the full quantitative results and risk of bias ratings when examining the available evidence. High-level summary information as reported in Carlson et al.12 is useful at the scoping stage to understand the quantity of available data but does not allow for users to assess the findings or utility of the available studies. The information in this SEM is being disseminated in downloadable formats and an interactive dashboard to facilitate further analyses. The aim is to identify a) what epidemiological evidence exists for health effects of exposure to the selected PFAS, b) priorities for further assessment/systematic review, and c) gaps in knowledge/future research needs.

Methods

The systematic review methods used to conduct this evidence map are outlined in the Office of Research and Development (ORD) Staff Standard Operating Procedures for Developing Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) Assessments (IRIS Handbook).13

Selection of PFAS for Inclusion in the SEM

The set of approximately 150 PFAS on which this review focused were previously identified by U.S. EPA for tiered toxicity and toxicokinetic testing to cover a range of PFAS structures, chemistries, and environmental relevance that would address two overarching objectives: maximizing the ability to perform read-across11 and characterizing the structural diversity and coverage of the PFAS landscape. Substances were identified in two phases. In the first phase, the testing sample library was characterized by 53 expert defined structural categories, building on the classification hierarchy first described by Buck et al.14 Using these categories, 75 substances were selected on the basis of interest to U.S. EPA, category size, structural diversity, and testability, as well as availability of existing in vivo toxicity data. The specific considerations for the selection of these 75 substances are described in more detail in Patlewicz et al.15 The process by which the second set of 75 were selected largely followed the same process except for two main differences: A portion of the Phase 2 substances were identified a priori as part of a nomination process (soliciting U.S. EPA Program Offices, Regions, and States to nominate any PFAS within the testing library), and the expert-based structural categories were extended to cover the full scope of the testing library that had since been developed. The selected PFAS are listed in Excel Table S1 (the complete list includes 180 PFAS, including conjugate salts, acids, etc.).

Literature Search and Screening

The approach for literature search and screening was described in Carlson et al.,12 which had a broader scope to include animal toxicology studies as well as tagging of supplemental information. A separate search was not performed for this SEM. The methods relevant to epidemiology studies are summarized here.

The Populations, Exposures, Comparators, and Outcomes (PECO) criteria relevant to epidemiology studies are presented in Table 1. The PECO criteria were intentionally broad to identify studies of any health effects in humans with information on associations with exposure to the identified PFAS. The focus was identification of results interpretable for a single pollutant; if results were reported only for a summed mixture of PFAS, the study was classified as supplemental material due to the inability to isolate the effects of the individual PFAS of interest.

Table 1.

PECO criteria for systematic evidence map of epidemiology studies of health effects for 150 PFAS.

| PECO element | Description |

|---|---|

| Populations | Human: Any population and life stage (occupational or general population, including children and other sensitive populations). |

| Exposures | Human: Any exposure to approximately 150 PFAS via the oral and inhalation routes because these are typically the most useful for developing human health toxicity values. Studies are also included if biomarkers of PFAS exposure are evaluated (e.g., measured PFAS or metabolite in tissues or bodily fluids), but the exposure route is unclear or reflects multiple routes. |

| Comparators | Human: A comparison or referent population exposed to lower levels (or no exposure/exposure below detection limits), or exposure for shorter periods of time. However, worker surveillance studies are considered to meet PECO criteria even if no referent group is presented. Case reports describing findings in 1–3 people in non-occupational or occupational settings are tracked as supplemental material. |

| Outcomes | All health outcomes (cancer and noncancer). |

Note: PECO, populations, exposures, comparators, and outcomes; PFAS, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances.

The search was performed in August 2019 and updated in December 2020 and December 2021 by a U.S. EPA information specialist. The following databases were searched for literature containing the chemical search terms: PubMed (National Library of Medicine), Web of Science (Thomson Reuters), and ToxLine via the ToxNet (the latter for 2019 search only because ToxLine content was subsequently moved to PubMed). The search terms tailored for each of these databases are available in Excel Table S2. All records were stored in the U.S. EPA’s HERO database (https://hero.epa.gov). After deduplication, SWIFT Review software (version 1.42; Sciome LLC)16 was used to identify which of these unique references were most relevant for human health risk assessment. In brief, SWIFT Review was used to filter the unique references based on the software’s preset literature search strategies. References are tagged to a specific evidence stream if the search terms from that evidence stream appear in the title, abstract, keyword, and/or medical subject headings (MeSH) fields of that reference. The following SWIFT Review evidence streams were applied: human (used for this SEM), animal models for human health, and in vitro studies. Specific details on the evidence stream search strategies are available in the Supplemental Material file named SWIFT-Review-Search-Strategies-Evidence-Stream.docx. To identify any studies missed by the database search, reference lists from the following PFAS projects and other databases were searched as well: the health effects chapter of the draft ATSDR Toxicological Profile,9 an evidence map by The Endocrine Disruptor Exchange,17 any other human health review or assessment identified from the literature search, the National Toxicology Program (NTP) database of study results and research projects (based on personal communication with NTP as described in Carlson et al.12) references from the U.S. EPA Chemicals Dashboard ToxVal database,18 and the European Chemicals Agency registration dossiers.19

For literature screening, the studies identified from the database searches and SWIFT Review were imported into SWIFT-Active Screener (version 1.061; Sciome LLC) for title/abstract (TIAB) screening. SWIFT-Active Screener is a web-based collaborative software application that uses active machine-learning approaches to reduce the screening effort.20 The screening process was designed to prioritize records that appeared to meet the PECO criteria or included relevant supplemental information that was not used in this SEM [e.g., mechanistic evidence, information on absorption/distribution/metabolism/excretion (ADME), exposure information, meta-analyses, and others described in the protocol] based on TIAB; consequently, both types of records (PECO relevant and supplemental) were screened as “include” for active-learning purposes. Screening continued until SWIFT-Active Screener indicated that it was likely that at least 95% of the relevant studies were identified. Studies meeting the criteria from TIAB screening and studies identified from the searches of additional resources were then imported into Distiller SR (version 2.29.0; Evidence Partners Inc.) for an additional round of more specific TIAB tagging (i.e., to distinguish studies meeting PECO criteria vs. supplemental content and to tag the specific type of supplemental content) and full-text screening. Both TIAB and full-text screening were conducted by two independent reviewers. Screening conflicts were resolved by discussion between the primary screeners with consultation by a third reviewer (if needed) to resolve any remaining disagreements.

Data Extraction

The epidemiology studies that were determined to meet PECO criteria after full-text review underwent data extraction for all included PFAS using a structured form in DistillerSR. The form is available in Figure S1; in brief, the form captured citation information, study design characteristics (population, study design, country, year of data, exposure measurement type, exposure levels, outcome measures, sample size), whether the paper presented correlations across PFAS (though the actual correlations were not extracted), covariates included in statistical modeling, and quantitative results (effect estimate, confidence interval). Data extraction was performed by a trained member of the team (primary extractor) and checked by a second member for completeness and accuracy [quality control (QC) extractor]. Authors were not contacted for information that was not reported in a study. The data from these extractions were exported from DistillerSR to an Excel format and then transformed for import into Tableau visualization software (https://www.tableau.com/). The data transformations include pivoting multiple columns of data to single columns and merging detailed reference information and chemical ID information into the data set. The available evidence was visualized in Tableau, and the full extraction file is available in Excel Table S4.

Study Evaluation

Studies were evaluated for risk of bias (i.e., factors that could affect the magnitude or direction of an estimated effect in either direction) and reduced sensitivity (i.e., factors that limit the ability of a study to detect a true effect), using the approach described in the IRIS Handbook.13 Evaluation was performed by two members of the team, with conflict resolution by a third member as needed. Evaluations were performed in the U.S. EPA’s version of the Health Assessment Workspace Collaborative (HAWC, https://hawcprd.epa.gov/), a free and open-source web-based software application designed to manage and facilitate the process of conducting health assessments. Studies were evaluated on the following domains (Figure 1): participant selection, exposure measurement, outcome ascertainment, confounding, analysis, study sensitivity, and selective reporting. Evaluations were conducted using core and prompting questions that define the domain and established criteria that apply to all exposures and outcomes, which describe how to reach specific rating levels.13 In addition, specific criteria for evaluation of PFAS exposure developed for IRIS PFAS assessments were incorporated,7 which included consideration of potential for confounding across PFAS.

Figure 1.

![Figure 1A is a tabular representation titled Study evaluation domains having seven rows and two columns, namely, Epidemiology domain and Core question. Row 1: Exposure measurement. Does the exposure measure reliably distinguish between levels of exposure in a time window considered most relevant for a causal effect with respect to the development of the outcome? Row 2: Outcome ascertainment. Does the outcome measure reliably distinguish the presence or absence (or degree of severity) of the outcome? Row 3: Participant selection. Is there evidence that selection into or out of the study (or analysis sample) was jointly related to exposure and to outcome? [note: this includes attrition]. Row 4: Confounding. Is confounding of the effect of the exposure likely? Row 5: Analysis. Does the analysis strategy and presentation convey the necessary familiarity with the data and assumptions? Row 6: Sensitivity. Is there a concern that sensitivity of the study is not adequate to detect an effect? Row 7: Selective reporting. Is there reason to be concerned about selective reporting? Figure 1B is a tabular representation titled Domain judgments having three rows and two columns, namely, judgment and interpretation. Row 1: Good implies appropriate study conduct relating to the domain and minor deficiencies not expected to influence results. Adequate implies a study that may have some limitations relating to the domain, but they are not likely to be severe or to have a notable impact on results. Row 2: Deficient implies identified biases or deficiencies interpreted as likely to have a notable impact on the results or prevent reliable interpretation of study findings. Row 3: Critically deficient implies a serious flaw identified that makes the observes effect(s) uninterpretable. Studies with a critical deficiency will almost always be considered “uninformative” overall. Figure 1C is a tabular representation titled Overall study rating for an outcome having three rows and two columns, namely, Rating and Interpretation. Row 1: High implies no notable deficiencies or concerns identified; potential for bias unlikely or minimal; sensitive methodology. Medium implies possible deficiencies or concerns noted but resulting bias or lack of sensitivity is unlikely to be a notable degree. Row 2: Low implies deficiencies or concerns were noted, and the potential for substantive bias or inadequate sensitivity could have a significant impact on the study results or their interpretation. Row 3: Uninformative implies serious flaw(s) makes study results unusable for hazard identification or dose response.](https://cdn.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/blobs/ea5c/9524599/2459c853ab54/ehp11185_f1.jpg)

Summary of study evaluation approach for systematic evidence map. (A) evaluation domains. (B) domain judgments and interpretations. (C) overall study confidence ratings and interpretations. Note: Adapted from Office of Research and Development (ORD) Staff Standard Operating Procedures for Developing Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) Assessments.13 This resource provides the full description of the methods used to evaluate risk of bias and sensitivity in the included studies.

For each study, each evaluation domain was rated as Good/Adequate, Deficient, or Critically deficient. Once the evaluation domains were rated, the identified strengths and limitations across domains were considered to reach an overall study confidence rating of High/Medium, Low, or Uninformative for a specific PFAS-health outcome combination. Overall confidence ratings were based on expert judgment of the likely impact that the identified domain limitations would have on the results; no predefined weighting of domains was applied. The ratings, which reflect a consensus judgment between reviewers, are defined in Figure 1. The merging of the top two rating levels differs from the approach described in the IRIS Handbook because the focus of study evaluation for this SEM was to identify important deficiencies that should be considered when interpreting results rather than informing full evidence synthesis. All evaluations were performed on an outcome-specific basis, and thus a single study may have different ratings for different included outcomes.

Results

Literature Screening Results

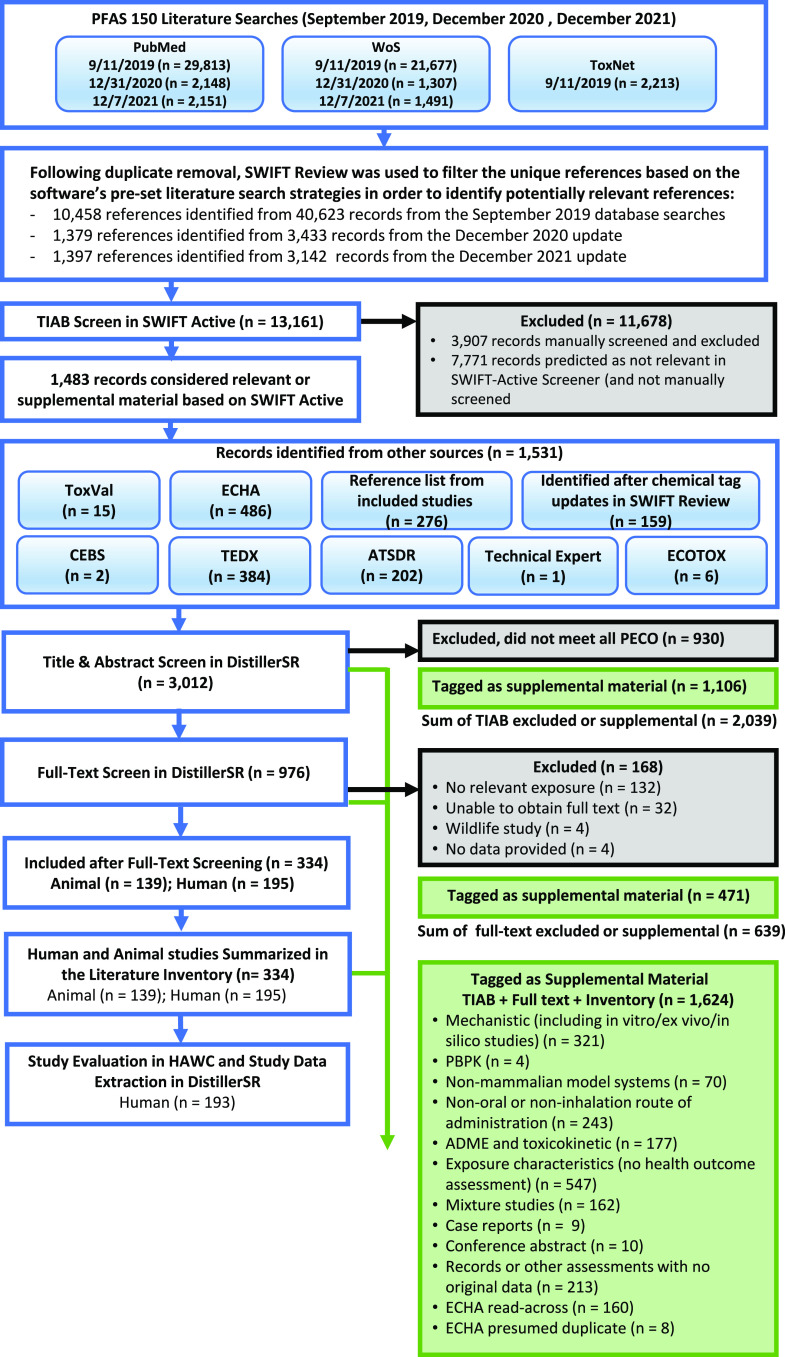

A summary of the literature search and screening process and results is presented in Figure 2, and the references from the full process are available at https://hero.epa.gov/hero/index.cfm/project/page/project_id/2826. The database searches yielded 11,837 records following de-duplication and prioritization in SWIFT Review. During full-text review, 195 epidemiology studies were considered PECO relevant. After removing two studies that were limited to data presented in other included studies, 193 epidemiology studies proceeded to study evaluation and data extraction.

Figure 2.

Literature flow diagram for systematic evidence map of epidemiology studies for 150 PFAS. Note: Literature identified in other sources was brought into screening at DistillerSR title-abstract review. References may have multiple supplemental tags. Two human studies did not proceed to study evaluation and data extraction because they were represented by other included studies. ADME, absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion; ATSDR, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry; ECHA, European Chemicals Agency; ECOTOX, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Ecotoxicology Knowledgebase; HAWC, Health Assessment Workspace Collaborative; NTP, National Toxicology Program Chemical Effects in Biological Systems; PBPK, physiologically based pharmacokinetic; PECO, populations, exposure, comparator, outcome criteria; TEDX, PFAS evidence map prepared by The Endocrine Disruptor Exchange; TIAB, title/abstract screening; ToxVal, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency CompTox Chemicals Dashboard; WoS, Web of Science.

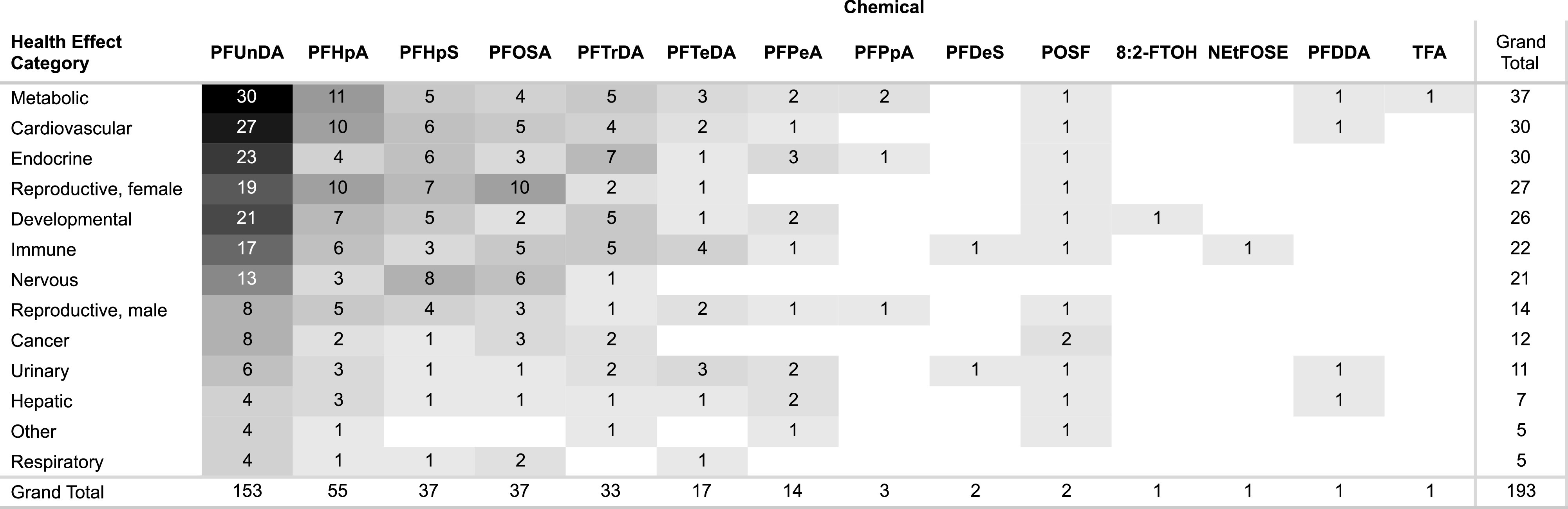

A total of 193 epidemiology studies were identified that included information on 15 different PFAS out of the approximately 150 searched. A list of included studies by included PFAS is available in Excel Table S3. All of the available studies examined exposure to multiple PFAS, and some included multiple PFAS in the SEM. These studies may include multiple publications of the same study population. The most frequently studied chemicals, with more than 10 studies available, were perfluoroundecanoic acid (PFUnDA, 153 studies), perfluoroheptanoic acid (PFHpA, 55), perfluorooctanesulfonamide (PFOSA, 37), perfluoroheptanesulfonic acid (PFHpS, 37), perfluorotridecanoic acid (PFTrDA, 33), perfluorotetradecanoic acid (PFTeDA, 17), and perfluoropentanoic acid (PFPeA, 14). The majority of the searched PFAS had zero epidemiology studies available.

Study Characteristics and Findings

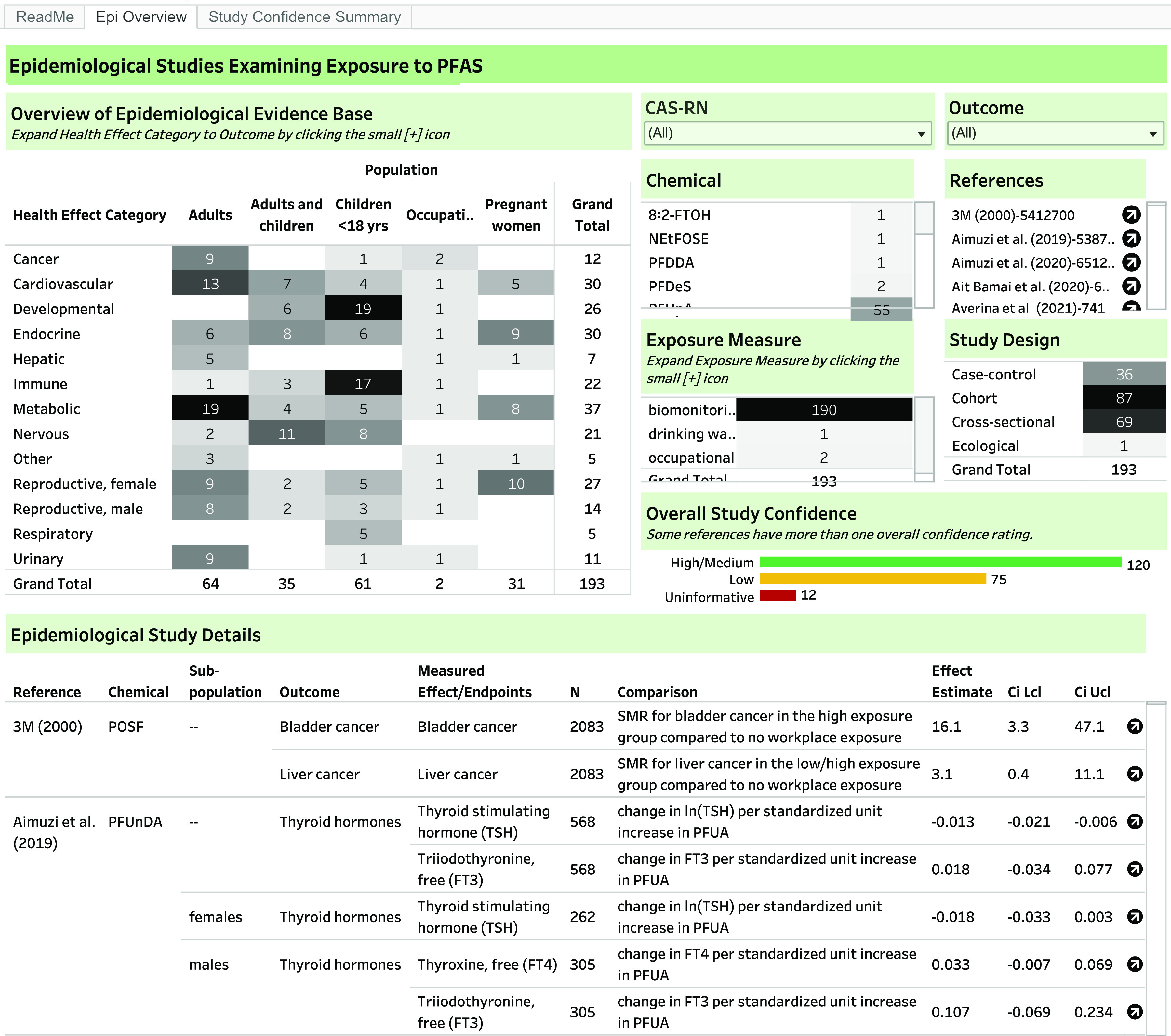

An interactive dashboard with the quantitative study results and study evaluations, filterable by PFAS, health effect category, outcome, population (adults, adults and children, children , pregnant women, occupational, or other), and study design is available at https://hawcprd.epa.gov/summary/visual/assessment/100500085/Epidemiological-Studies-and-Study-Confidence/(screenshot shown in Figure 3). Additional extracted information on each study is available by hovering over the results. All data extracted is also available in Excel Table S4.

Figure 3.

Screenshot of interactive dashboard for systematic evidence map of epidemiology studies for 150 PFAS. The interactive dashboard is available at https://hawcprd.epa.gov/summary/visual/assessment/100500085/Epidemiological-Studies-and-Study-Confidence/. The results are filterable by PFAS, health effect category, population, exposure measure, study design, overall study confidence, and reference by clicking on the relevant cell.

The most commonly studied health effect categories were metabolic (37 studies), endocrine (30), cardiovascular (30), female reproductive (27), developmental (26), immune (22), nervous (21), male reproductive (14), cancer (12), and urinary (11) effects (Figure 4). The other health effect categories had studies each.

Figure 4.

Heat map of number of studies by health effect category and PFAS. In the interactive dashboard (https://hawcprd.epa.gov/summary/visual/assessment/100500085/Epidemiological-Studies-and-Study-Confidence/), the number of studies by health effect category and/or PFAS can be obtained by clicking on the cell to filter by. This information can also be obtained by filtering Excel Table S4. Note: 8:2-FTOH, 8:2 fluorotelomer alcohol; PFDDA, perfluoro-2,5,dimethyl-3,6-dioxanonanoic acid; PFDeS, sodium perfluorodecanesulfonate; PFHpA, perfluoroheptanoic acid; PFHpS, perfluoroheptanesulfonate and perfluoroheptanesulfonic acid; PFUnDA, perfluoroundecanoic acid; PFOSA, perfluorooctanesulfonamide; PFTrDA, perfluorotridecanoic acid; PFTeDA, perfluorotetradecanoic acid; PFPeA, perfluoropentanoic acid; PFPpA, perfluoropropanoic acid; POSF, perfluorooctanesulfonyl fluoride; NEtFOSE, N-ethyl-N-(2-hydroxyethyl)perfluorooctanesulfonamide; TFA, trifluoroacetic acid.

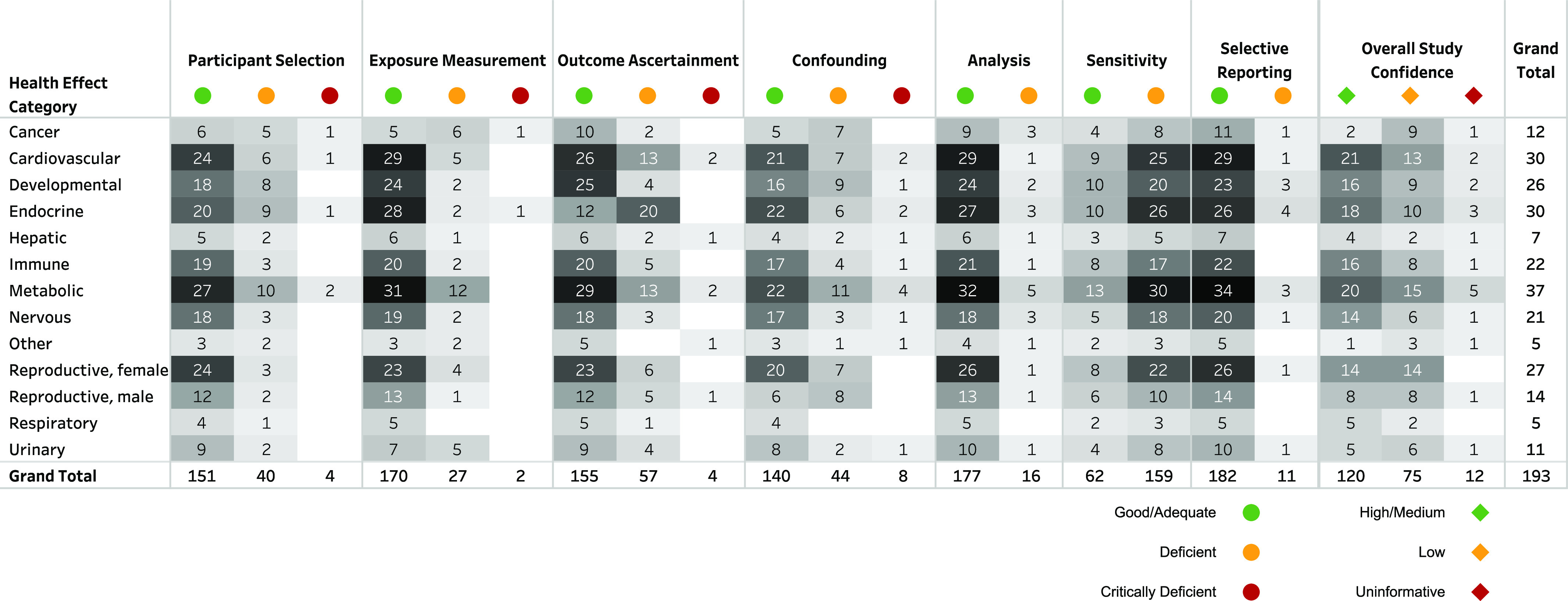

Study Evaluation

Some studies had more than one rating due to differences in ratings by specific outcome (this is reflected in the total number of ratings in Figures 3 and 5 being greater than the total number of studies). For overall study confidence, 120 (62%) studies were High/Medium confidence for at least one outcome (Figures 3 and 5). Over a third of the studies (73, 38% studies) were Low confidence or Uninformative for all outcomes. The study evaluation ratings and rationales are available in the dashboard linked above (Study Confidence Summary tab), filterable by health effect category, outcome, rating, and chemical. A summary of overall study confidence by health effect category is summarized in Figure 5, and study confidence ratings and rationales for each study are available in the interactive dashboard and Excel Table S5.

Figure 5.

Summary of study evaluations by domain and health effect category. In the interactive dashboard (https://hawcprd.epa.gov/summary/visual/assessment/100500085/Epidemiological-Studies-and-Study-Confidence/, “Study Confidence Summary” tab), each domain/overall confidence rating and rationale is available, filterable by PFAS, health effect category, outcome, and rating. This information is also available in Excel Tables S4 and S5. Note: PFAS, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances.

The plurality of studies were prospective cohorts (87 studies), followed by cross-sectional (69) and case–control studies (36); one study was ecological. Nearly all (190, 98%) studies measured PFAS exposure using biomarkers, most commonly in serum (80 studies); plasma (29); or whole blood (4); maternal blood, serum, or plasma (52); or cord blood, serum, or plasma (25). Seven studies used biomarkers in other matrices, including semen and breast milk; some studies used more than one matrix. One study examined drinking water, and two studies analyzed occupational exposure based on job title/duties. See Excel Table S4.

The majority of the studies were well conducted with Good/Adequate ratings in most domains (Excel Table S5). However, the study sensitivity domain goes beyond study design and conduct to identify factors that may reduce a study’s ability to detect an association and that should be considered in the interpretation of the findings. A total of 159 studies (82%) were rated as Deficient for study sensitivity for at least one PFAS; 131 (68%) were Deficient for all the included PFAS 150 chemicals. These ratings were primarily due to concerns of limited exposure contrast; these PFAS generally had narrow ranges of exposure and low exposure levels (1–2 orders of magnitude lower than most epidemiology studies of PFOA and PFOS; specific exposure levels are available in the dashboard). In many cases a high percentage of measurements were below the method limit of detection (LOD; Excel Table S4), but the proportion of measurements that were varied by PFAS (Table 2). To our knowledge, there is no evidence to conclude that these lower exposure levels are not toxicologically relevant (i.e., able to result in adverse health effects), but null results in these studies are not interpreted as evidence of a lack of effect. Rather, the inability to examine the effects of exposure at low levels (below method LODs) is an important challenge in studying these PFAS and interpreting the findings.

Table 2.

Number (and percent) of studies with percent of exposure measurements below LOD by PFAS.

| Chemical | Percentage | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20%–39% | 40%–59% | 60%–79% | Not reported | ||||

| 8:2-FTOH | — | — | 1 (100%) | — | — | — | 1 |

| NEtFOSE | — | — | — | — | — | 1 (100%) | 1 |

| PFDDA | 1 (100%) | — | — | — | — | — | 1 |

| PFDeS | — | — | — | — | — | 2 (100%) | 2 |

| PFHpA | 19 (35%) | 16 (29%) | 7 (13%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 12 (22%) | 55 |

| PFHpS | 29 (78%) | 4 (11%) | 1 (3%) | — | — | 4 (11%) | 37 |

| PFOSA | 11 (30%) | 9 (24%) | — | 4 (11%) | 4 (11%) | 9 (24%) | 37 |

| PFPeA | 3 (21%) | 4 (29%) | 3 (21%) | — | — | 4 (29%) | 14 |

| PFPpA | 2 (67%) | 1 (33%) | — | — | — | — | 3 |

| PFTeDA | 5 (29%) | 2 (12%) | 2 (12%) | 1 (6%) | 1 (6%) | 6 (35%) | 17 |

| PFTrDA | 21 (64%) | 3 (9%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (6%) | — | 6 (18%) | 33 |

| PFUnDA | 103 (67%) | 23 (15%) | 8 (5%) | 1 (1%) | — | 19 (12%) | 153 |

| POSF | — | — | — | — | — | 2 (100%) | 2 |

| TFA | 1 (100%) | — | — | — | — | — | 1 |

| Total | 128 (66%) | 51 (26%) | 21 (11%) | 9 (5%) | 6 (3%) | 30 (16%) | 193 |

Note: Most studies reported percent below the limit of detection, but in some cases, only percent below the limit of quantification was reported. Although these are distinct concepts, they are both used here to represent the percent of participants in each study with negligible exposure. Excel Table S4 provides details on the percent below the LOD for individual studies. —, no data; 8:2 FTOH, 8:2 fluorotelomer alcohol; LOD, limit of detection; NEtFOSE, N-ethyl-N-(2-hydroxyethyl)perfluorooctanesulfonamide; PFAS, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances; PFDDA, perfluoro-2,5,dimethyl-3,6-dioxanonanoic acid; PFDeS, sodium perfluorodecanesulfonate; PFHpA, perfluoroheptanoic acid; PFHpS, perfluoroheptanesulfonate and perfluoroheptanesulfonic acid; PFOSA, perfluorooctanesulfonamide; PFPeA, perfluoropentanoic acid; PFPpA, perfluoropropanoic acid; PFTrDA, perfluorotridecanoic acid; PFUnDA, perfluoroundecanoic acid; PFTeDA, perfluorotetradecanoic acid; POSF, perfluorooctanesulfonyl fluoride; TFA, trifluoroacetic acid.

Another issue that was present in multiple studies was concern for potential confounding by other PFAS, given that all study participants were exposed to multiple PFAS. This issue would mainly be a concern (affect ability to interpret study results) when there is moderate to high correlations between PFAS and represents a source of uncertainty in interpreting the results for individual PFAS. In the database, 121 (63%) studies reported correlations for at least some combinations of PFAS (Excel Table S4). This information can inform directionality (and to a degree, magnitude) of associations between coexposures; importantly, correlations analysis can be a first step to gauging the potential for confounding and may lead to greater confidence (when correlations are relatively low) or lesser confidence (when correlations are high) in interpreting study results. Of course, if these correlated exposure are not strong risk factors for the same end points being examined, our concern for potential confounding is minimized.

Discussion

This SEM provides a resource for identifying existing epidemiology studies of PFAS exposure and health effects. The original impetus for its development was to summarize the available evidence for a subset of PFAS that are undergoing in vitro high-throughput toxicity and toxicokinetic testing at the U.S. EPA.15 The data contained herein will enhance interpretation of those testing results, but there are a variety of additional potential uses. For researchers, it can assist in identifying data gaps for future research. For regulatory and other agencies conducting health assessments, it can be used to prioritize PFAS for further review/evaluation of toxicity.21 The SEM also allows for determination of the consistency of results within and across PFAS. This determination is informative for efforts aimed at examining similarity or difference in associated health effects across PFAS, which, alongside other relevant considerations (e.g., chemical structure; human exposure potential) may help inform efforts to group different PFAS for evaluation.

Overall, outside of a few highly studied PFAS, little to no epidemiology data on most PFAS were available to inform evaluation of potential health effects. Some PFAS (e.g., PFUnDA, PFHpA) appear to have sufficient data quality/quantity to develop systematic reviews of some outcomes. Without doing a full evidence synthesis, which is outside the scope of this SEM, it is difficult to definitively state where evidence is adequate to draw conclusions. However, gaps in the available database for most of the PFAS in this SEM are expected to preclude the ability to interpret whether exposure might be associated with health effects based on the epidemiology data. These data deficits are particularly true for health effects with the fewest studies available, such as respiratory, urinary, cancer, and nervous system effects. However, even when more studies are available, the data may be inadequate to draw conclusions (some of the reasons for this are described below). Understanding potential health effects associated with PFAS is important, given the ubiquity and extent of exposure in the United States, the most recent data release from the Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals displays information for 12 different PFAS measured in serum and 15 PFAS measured in urine, including three of the PFAS examined in this SEM (PFUnDA, PFHpA, and PFOSA).1 These data can highlight overall patterns of exposure over time and subgroups that may be at increased risk due to higher levels of exposure, spurring research on subsequent health effects and elevating PFAS with demonstrated exposures in the general population to examine in future studies.

Epidemiology studies can be highly influential to human health risk assessments of chemical exposure. They provide the most relevant data in our species of interest (humans), which can eliminate the need for extrapolation from animal models.13 They also assess real-world exposure scenarios, including exposure to different mixtures (such as PFAS), which is often more relevant than high-dose experimental animal studies focused on a single chemical exposure at a time (though understanding the mixture of exposures is a challenge). With sufficient high-quality (i.e., externally and internally valid) epidemiology data, conclusions regarding causality can be drawn independent of other evidence streams.13 In addition, for more highly studied PFAS that are undergoing the assessment process, toxicity values based on human studies have generally been lower in comparison with values based on animal toxicology studies (e.g., the California EPA’s recent assessment8 and draft assessments of PFOA and PFOS by the U.S. EPA). However, there are limitations inherent to observational studies, some of which arise from lack of experimental conditions (e.g., randomization to exposure groups and control of exposure levels and timing). Thus, integrating findings from multiple studies is important, particularly when the results can be compared in light of contrasting study designs and potential biases.13 In this SEM, although there are a large number of High/Medium confidence epidemiology studies available, many health outcomes have only a single study or a small number of studies with inconsistent results. Given the limitations above, unless results from a single study are extremely compelling (e.g., demonstrate large effect estimate, clear exposure–response gradient, minimal risk of bias and sensitivity concerns), it is challenging to draw causal conclusions based on a single epidemiology study alone. Even when multiple studies exist for a given PFAS–outcome combination, apparent inconsistency is often present, and it will be important for future evidence synthesis efforts to probe any potential reasons for these differing results (e.g., between-study heterogeneity due to variable levels of susceptibility of study populations or subpopulations, study sensitivity, specific sources of bias, different exposure levels and contrasts being compared). An additional important consideration is that when there are gaps in the epidemiology evidence, observing coherence in effects across human and animal studies or using mechanistic evidence to provide biological plausibility of effects can result in more definitive causal conclusions (in addition to the other important influences of these other data streams).13

However, given that there are thousands of PFAS in existence or development,4 high-quality epidemiology (or animal) data are unlikely to be available for most PFAS, and prioritization efforts such as this SEM will increasingly be needed. Further, despite tremendous analytical advancements, current and future epidemiology studies (which typically target only PFAS per study) will be complicated by relatively low levels of exposure detected in the population, as was observed in this SEM, limiting sensitivity and thus reducing confidence in null findings. Because of this complication, for many PFAS it will not be possible to generate informative epidemiology evidence, and other methods will need to be used to determine their toxicity.

A source of uncertainty for assessment of individual PFAS (where exposure contrast is adequate to detect an association) stems from the potential for confounding by other PFAS coexposures. Correlations across subsets of PFAS were reported in almost two-thirds of the evaluated studies, but only a minority examined the potential for confounding between PFAS using statistical techniques such as multipollutant models. Furthermore, even when a comparison of results of single and multipollutant models is presented to evaluate the potential confounding, the potential of amplification bias22 from highly correlated coexposures can impact the validity and complicate interpretation of these results. This potential for bias and its interpretation is a current research gap. An important consideration for evaluating such bias includes the toxicokinetic and toxicodynamic interactions of PFAS mixtures, which could lead to either underestimation or overestimation of associations with health end points23 and is another gap in current knowledge. An example of underestimation would result from competitive binding with key receptors, a toxicodynamic effect.24,25 Underestimation or overestimation could result from toxicokinetic interactions that could affect the rate of PFAS excretion or the distribution of PFAS in the body, which affects the ratio between the serum and target tissue, including the products of conception in developmental end points.26 Active methods development for analysis and interpretation of mixtures data is underway, such as the use of Bayesian kernel machine regression, quantile-based g-computation, and other approaches,27 but many new methods focus on joint effects of mixtures and may preclude interpretation of the effects of individual PFAS. Still, with new developments, we are hopeful that future studies will be better able to characterize the effects of individual PFAS and joint effects in a mixtures setting. Additional efforts to address the issues described here would enable more informative epidemiological studies to add to the literature base and potentially be used for risk assessment purposes.

For the purposes of regulation, there is often a focus on chemicals where the potential for human health impacts is recognized (“legacy” chemicals) rather than emerging chemicals. The challenges of evaluating emerging PFAS are compounded by limitations in both resources and existing data (such as those described above). Moving forward, one approach to address this issue is to consider health effects of the PFAS in combination or as a group of similar PFAS rather than evaluating each compound in isolation. This approach may better reflect reality because exposures to PFAS are often highly correlated. It also avoids extensive delays inherent to researching and regulating them one at a time. In addition, industries tend to move away from use of “legacy” chemicals when associated health risks are identified, in favor of replacements that are often less characterized with respect to toxicity. One manifestation of this shift with PFAS is a trend toward use of those with shorter half-lives and environmental persistence (e.g., PFAS with shorter chain lengths or functional groups), although it is not clear whether they are necessarily safer.28,29 Possible methods for grouping PFAS have been described previously.15,28,30 Similar to other agencies’ ongoing efforts to consider grouping of PFAS for regulation,28,31,32 the U.S. EPA has also recently taken several steps in this direction, with the aim of “accelerating the effectiveness of regulations, enforcement actions, and the tools and technologies needed to remove PFAS from air, land, and water,”33 and this is an important area for future research. In addition to assessing the current utility of traditional structural categories, this approach includes examining joint toxicity, potentially defining PFAS categories based on toxicity (which this SEM will inform) and toxicokinetic data as well as on removal techniques; these categories will be used to prioritize risk assessment needs.33 In addition, the U.S. EPA has strengthened restrictions around new uses of PFAS.3

This SEM used state-of-the-art systematic mapping methods and thus provides a comprehensive representation of the epidemiological evidence for health effects associated with exposure to approximately 150 PFAS (only 15 of which have been examined in epidemiology studies). It expands beyond another recently posted but unrelated SEM of PFAS exposure that includes some of the same PFAS17 by including complete data extraction and study evaluation, allowing a more thorough understanding of the available data as well as research needs. The full quantitative extraction is a strength of this SEM, because evidence maps (and other methods of evidence summary) often rely on statistical significance and/or author interpretations (which may be impacted by selective reporting and study sensitivity considerations) to indicate whether associations between exposures and health outcomes exist in the study population. This approach may be misleading, given the limitations of statistical significance as a primary indicator of an association,34 and we made no such interpretations. With the specific results extracted and easily filterable and downloadable, the reader can come to their own interpretations about the findings as appropriate for their specific question. Overall, the extensive data extraction and study evaluation efforts allow for a more complete future analysis of patterns across the data, including consistency within and between studies as well as a thorough examination of study sensitivity. However, an important limitation in interpreting the results across studies is that there was no data standardization; studies do not report their results in a uniform way, and this SEM did not attempt to rescale any of the results to improve comparability across studies. In addition, although we advocate for the use of mixture approaches to better understand and regulate PFAS exposures, this SEM focused only on results for individual PFAS; we hope that future work will include examination of mixture results.

In conclusion, this SEM is a valuable resource for accessing and understanding the available epidemiology evidence for health effects of these PFAS, identifying data gaps, and prioritizing PFAS for further evaluation. Although PFAS research has been exploding over the last decade, it is important to recognize that the epidemiology evidence is primarily limited to a small number of high-profile PFAS, some of which represent ongoing exposures despite limitations in their industrial production and use. An important possibility is that less-studied PFAS may be used to replace these “legacy” PFAS, leading to greater exposure over time. Realistically, it will be impossible to generate epidemiological evidence to fill the existing gaps for all the potentially relevant PFAS in a reasonable time frame. This SEM highlights some of the important research gaps that currently exist and points to the potential utility of defining categories of PFAS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank A. Kraft, L. Carlson, A. Shirke, D. Shams, A. Shapiro, M. Angrish, G. Patlewicz, M. Dzierlenga, K. Rappazzo, J. Lees, S. Jones, and B. Glenn of the U.S. EPA for their input and support in developing this evidence map. The authors would also like to thank the following ICF staff for assistance in extracting data, evaluating studies, and creating the literature flow diagram: A. Lindahl, J. Greig, A. Schumacher, R. Blain, S. Eftim, K. Clark, and N. Vetter.

This material has been funded in part by the U.S. EPA under contract 68HERC19D0003 to ICF International. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or policies of the U.S. EPA. Any mention of trade names, products, or services does not imply an endorsement by the U.S. government or the U.S. EPA. The U.S. EPA does not endorse any commercial products, services, or enterprises.

References

- 1.U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019. Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals, Updated Tables, January 2019, vol. 2. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). 2016. Health effects support document for perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA). Washington, DC: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Water, Health and Ecological Criteria Division. [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. EPA. 2021. Risk management for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) under TSCA. https://www.epa.gov/assessing-and-managing-chemicals-under-tsca/risk-management-and-polyfluoroalkyl-substances-pfas [accessed 1 March 2022].

- 4.U.S. EPA. CompTox Chemicals Dashboard: PFAS Master List of PFAS Substances (Version 4). https://comptox.epa.gov/dashboard/chemical_lists/PFASMASTER [accessed 8 August 2021].

- 5.Wang Z, DeWitt JC, Higgins CP, Cousins IT. 2017. A never-ending story of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs)? Environ Sci Technol 51(5):2508–2518, PMID: , 10.1021/acs.est.6b04806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pan Y, Wang J, Yeung LWY, Wei S, Dai J, et al. 2020. Analysis of emerging per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances: progress and current issues. Trends Analyt Chem 124:115481, 10.1016/j.trac.2019.04.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. EPA. 2019. Systematic Review Protocol for the PFAS IRIS Assessments. EPA/635/R-19/050. https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/iris_drafts/recordisplay.cfm?deid=345065 [accessed 4 January 2021].

- 8.California Environmental Protection Agency Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment. 2021. Public Health Goals: Perfluorooctanoic Acid and Perfluorooctane Sulfonic Acid in Drinking Water. Sacramento, CA: California Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, Pesticide and Environmental Toxicology Branch. [Google Scholar]

- 9.ATSDR (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry). 2021. Toxicological Profile for Perfluoroalkyls. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.NJDWQI (New Jersey Drinking Water Quality Institute). 2017. Maximum Contaminant Recommendation for Perfluorooctanoic Acid in Drinking Water: Basis and Background. Trenton, NJ: New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. https://www.nj.gov/dep/watersupply/pdf/pfoa-recommend.pdf [accessed 27 September 2022].

- 11.U.S. EPA. 2019. EPA’s Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) Action Plan Washington, DC: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlson LA, Angrish M, Shirke AV, Radke EG, Schulz B, Kraft A, et al. 2022. Systematic evidence map for 150+ per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Environ Health Perspect 130(5):056001, PMID: , 10.1289/EHP10343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.U.S. EPA. 2020. ORD Staff Handbook for Developing IRIS Assessments (Public Comment Draft). Washington, DC: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development, Center for Public Health and Environmental Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buck RC, Franklin J, Berger U, Conder JM, Cousins IT, de Voogt P, et al. 2011. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment: terminology, classification, and origins. Integr Environ Assess Manag 7(4):513–541, PMID: , 10.1002/ieam.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patlewicz G, Richard AM, Williams AJ, Grulke CM, Sams R, Lambert J, et al. 2019. A chemical category-based prioritization approach for selecting 75 per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) for tiered toxicity and toxicokinetic testing. Environ Health Perspect 127(1):14501, PMID: , 10.1289/EHP4555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howard BE, Phillips J, Miller K, Tandon A, Mav D, Shah MR, et al. 2016. SWIFT-Review: a text-mining workbench for systematic review. Syst Rev 5(1):87, PMID: , 10.1186/s13643-016-0263-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pelch KE, et al. 2021. PFAS-Tox Database. https://pfastoxdatabase.org/ [accessed 1 March 2022].

- 18.U.S. EPA. 2018. Chemistry Dashboard. Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 19.ECHA (European Chemicals Agency). 2020. Information on Chemicals. Helsinki, Finland: European Chemical Agency, European Union. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howard BE, Phillips J, Tandon A, Maharana A, Elmore R, Mav D, et al. 2020. SWIFT-Active screener: accelerated document screening through active learning and integrated recall estimation. Environ Int 138:105623, PMID: , 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2021. Review of U.S. EPA’s ORD Staff Handbook for Developing IRIS Assessments: 2020 Version. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weisskopf MG, Seals RM, Webster TF. 2018. Bias amplification in epidemiologic analysis of exposure to mixtures. Environ Health Perspect 126(4):047003, PMID: , 10.1289/EHP2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dzierlenga MW, Moreau M, Song G, Mallick P, Ward PL, Campbell JL, et al. 2020. Quantitative bias analysis of the association between subclinical thyroid disease and two perfluoroalkyl substances in a single study. Environ Res 182:109017, PMID: , 10.1016/j.envres.2019.109017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ojo AF, Peng C, Ng JC. 2020. Combined effects and toxicological interactions of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances mixtures in human liver cells (HepG2). Environ Pollut 263(Pt B):114182, PMID: , 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolf CJ, Rider CV, Lau C, Abbott BD. 2014. Evaluating the additivity of perfluoroalkyl acids in binary combinations on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α activation. Toxicology 316(1):43–54, PMID: , 10.1016/j.tox.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dennis NM, Subbiah S, Karnjanapiboonwong A, Dennis ML, McCarthy C, Salice CJ, et al. 2021. Species-and tissue-specific avian chronic toxicity values (CTVs) for perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and a binary mixture of PFOS and perfluorohexane sulfonate. Environ Toxicol Chem 40(3):899–909, PMID: , 10.1002/etc.4937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosato I, Zare Jeddi M, Ledda C, Gallo E, Fletcher T, Pitter G, et al. 2022. How to investigate human health effects related to exposure to mixtures of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances: a systematic review of statistical methods. Environ Res 205:112565, PMID: , 10.1016/j.envres.2021.112565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kwiatkowski CF, Andrews DQ, Birnbaum LS, Bruton TA, DeWitt JC, Knappe DRU, et al. 2020. Scientific basis for managing PFAS as a chemical class. Environ Sci Technol Lett 7(8):532–543, PMID: , 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.U.S. EPA. 2021. Human health toxicity values for hexafluoropropylene oxide (HFPO) dimer acid and its ammonium salt (CASRN 13252-13-6 and CASRN 62037-80-3) also known as “GenX chemicals.” Washington, DC: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Water, Health and Ecological Criteria Division.

- 30.Cousins IT, DeWitt JC, Glüge J, Goldenman G, Herzke D, Lohmann R, et al. 2020. Strategies for grouping per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) to protect human and environmental health. Environ Sci Process Impacts 22(7):1444–1460, PMID: , 10.1039/d0em00147c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blum A, Balan SA, Scheringer M, Trier X, Goldenman G, Cousins IT, et al. 2015. The Madrid Statement on poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs). Environ Health Perspect 123(5):A107–A111, PMID: , 10.1289/ehp.1509934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cousins IT, Goldenman G, Herzke D, Lohmann R, Miller M, Ng CA, et al. 2019. The concept of essential use for determining when uses of PFASs can be phased out. Environ Sci Process Impacts 21(11):1803–1815, PMID: , 10.1039/c9em00163h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.U.S. EPA. 2021. PFAS Strategic Roadmap: EPA Commitments to Action 2021–2024. Washington, DC: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wasserstein RL, Lazar NA. 2016. The ASA’s statement on p-values: context, process, and purpose. Am Stat 70(2):129–133, 10.1080/00031305.2016.1154108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.