Abstract

The ability to utilize Escherichia coli as a heterologous system in which to study the regulation of Agrobacterium tumefaciens virulence genes and the mechanism of transfer DNA (T-DNA) transfer would provide an important tool to our understanding and manipulation of these processes. We have previously reported that the rpoA gene encoding the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase is required for the expression of lacZ gene under the control of virB promoter (virBp::lacZ) in E. coli containing a constitutively active virG gene [virG(Con)]. Here we show that an RpoA hybrid containing the N-terminal 247 residues from E. coli and the C-terminal 89 residues from A. tumefaciens was able to significantly express virBp::lacZ in E. coli in a VirG(Con)-dependent manner. Utilization of lac promoter-driven virA and virG in combination with the A. tumefaciens rpoA construct resulted in significant inducer-mediated expression of the virBp::lacZ fusion, and the level of virBp::lacZ expression was positively correlated to the copy number of the rpoA construct. This expression was dependent on VirA, VirG, temperature, and, to a lesser extent, pH, which is similar to what is observed in A. tumefaciens. Furthermore, the effect of sugars on vir gene expression was observed only in the presence of the chvE gene, suggesting that the glucose-binding protein of E. coli, a homologue of ChvE, does not interact with the VirA molecule. We also evaluated other phenolic compounds in induction assays and observed significant expression with syringealdehyde, a low level of expression with acetovanillone, and no expression with hydroxyacetophenone, similar to what occurs in A. tumefaciens strain A348 from which the virA clone was derived. These data support the notion that VirA directly senses the phenolic inducer. However, the overall level of expression of the vir genes in E. coli is less than what is observed in A. tumefaciens, suggesting that additional gene(s) from A. tumefaciens may be required for the full expression of virulence genes in E. coli.

Agrobacterium tumefaciens is a soil bacterium which infects plant wound sites and induces tumor formation. The bacterium harbors a large tumor inducing plasmid (Ti plasmid) encoding virulence genes and transfer DNA (T-DNA). The function of the virulence genes is the processing and transfer of the T-DNA from the Ti plasmid into susceptible plant cells, with subsequent integration into the host genome (for recent reviews, see references 27 and 56). Located on the T-DNA are genes that direct the biosynthesis of the plant growth regulators auxin and cytokinin in the infected cells (1, 49). The synthesis of these plant growth regulators results in a rapid, uncontrolled cell division leading to production of a characteristic tumor at the site of infection. In addition, the T-DNA contains genes for the synthesis of a unique class of compounds called opines, which A. tumefaciens can utilize as a carbon and energy source (36).

In A. tumefaciens, the expression of virulence genes is under the control of a two-component regulatory system comprised of VirA and VirG (45, 52). VirA is an inner membrane histidine kinase (34, 54) which autophosphorylates in response to certain phenolic compounds released from wounded plants (44) with subsequent transfer of the phosphate moiety to the response regulator VirG (16, 22, 24). Once phosphorylated, VirG activates transcription from promoters containing a specific 12-bp sequence called the vir box, which is present in the promoters of all vir genes (25, 40). This expression is augmented by the presence of certain monosaccharides (5, 43) and an acidic pH (32), which is characteristic of plant wound sites. A periplasmic sugar-binding protein, ChvE, which is highly homologous to glucose-binding protein of Escherichia coli, interacts with the periplasmic portion of the VirA molecule in the presence of certain monosaccharides, including glucose and arabinose (2, 15). This interaction alone does not induce vir gene expression, but it sensitizes the VirA molecule to the phenolic inducers.

While A. tumefaciens is a potentially serious plant pathogen, the main interest in this organism is due primarily to its ability to transform plant cells. Researchers have developed delivery systems based on T-DNA transfer to engineer new traits into selected plant species (14). However, the exact mechanism of T-DNA transfer is still not well understood. The ability to use E. coli as a heterologous host in which to study the regulation of A. tumefaciens virulence genes and the mechanism of T-DNA transfer would constitute an excellent model system given the degree of characterization at both the biochemical and the genetic levels and the relative ease of genetic manipulation. However, all previous attempts to reconstitute inducer-mediated vir gene expression in E. coli have not been successful. Previously, we reported the identification of the rpoA gene, encoding the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase from A. tumefaciens, and that it was required for transcription of a virB promoter fused to lacZ (virBp::lacZ) fusion in E. coli using a constitutively active VirG mutant [VirG(Con)] which can activate vir gene expression independent of VirA and inducers (31). In this study, we report the successful reconstitution of inducer-dependent expression of a virBp::lacZ fusion in E. coli utilizing lac promoter-driven virA and virG. Effects of various environmental conditions on virulence gene activation in E. coli are also described. Furthermore, by the gene fusion approach, the C-terminal domain of RpoA from A. tumefaciens is shown to be required for interaction with the transcriptional activator VirG.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Bacterial strains were grown in either Luria-Bertani (LB) medium, mannitol glutamate-Luria salts (MG/L) medium (50), or induction medium containing either 55 mM glucose, mannitol, or glycerol (53). When appropriate, the medium was supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml), kanamycin (50 μg/ml), gentamicin (5 μg/ml), and tetracycline (20 μg/ml). For the growth of DH5α in induction medium, Casamino Acids (Difco) and thiamine were added to final concentrations of 0.1% (wt/vol) and 12 μg/ml, respectively. For M182 and M182Δcrp grown in induction medium, arginine and thiamine were added to final concentrations of 20 and 12 μg/ml, respectively. For visualization of expression of the virBp::lacZ fusion on plates, 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) and isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) were included at final concentrations of 75 μg/ml and 200 μM, respectively. The virulence gene inducers acetosyringone, acetovanillone, hydroxyacetophenone, and syringealdehyde (Sigma) were added where indicated at a final concentration of 200 μM.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or phenotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | recA endA1 hsdR17 supE4 gyrA96 relA1 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 (φ80dlacZΔM15) | 41 |

| MC4100 | F−araD139 Δ(argF-lac)U169 rpsL150 relA flb5301 ptsF25 deoC1 | 7 |

| M182 | K-12 Δlac crp+ | 8 |

| M182Δcrp | K-12 Δlac Δcrp | 4 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pIB410 | virBp::lacZ IncP Tcr | 5 |

| pPC401 | lacp::virG fusion in pTZ18R, Apr | 25 |

| pSW191 | lacp::virA fusion in pTZ18R, Apr | 54 |

| pSG692 | lacp::virA and lacp::virG in pTZ18R, Apr | This work |

| pSY215 | virB::lacZ Plac::virG(N54D) IncW Gmr | 31 |

| pSL107 | lacp::virA lacp::virG virBp::lacZ ColE1 IncP Apr Tcr | 31 |

| pSL204 | lacp::virA lacp::virG virBp::lacZ IncP Tcr | This work |

| pSJ0101 | lacp::virA virBp::lacZ IncP Tcr | This work |

| pSJ0102 | lacp::virG virBp::lacZ IncP Tcr | This work |

| pTZ18R/pTZ19R | Cloning vectors, ColE1 Apr | U.S. Biochemicals |

| pTC110 | Cloning vector, IncW Kmr Spr | 10 |

| pPS1.3 | lacp::rpoA from A. tumefaciens A136 in pTZ19R, Apr | 31 |

| pPS1.3R | Non-lacp-driven rpoA from A. tumefaciens A136 in pTZ18R, Apr | 31 |

| pHO98 | lacp::rpoA from A. tumefaciens A136 in pTC110, Kmr IncW | 31 |

| pTC1.1 | lacp::chvE from A. tumefaciens A136 in PCR2.1-TOPO, Apr | This work |

| pTCR2.4 | lacp::chvE, lacp::rpoA from A. tumefaciens A136 in PCR2.1-TOPO, Apr | This work |

| pQE30 and pQE31 | His expression vector, Apr | Qiagen |

| pZL2 | A. tumefaciens His-RpoA, Apr | 31 |

| pECH | E. coli His-RpoA, Apr | 31 |

| pAD8 | A. tumefaciens His-RpoA (deletion of C-terminal eight amino acids), Apr | This work |

| pEA8 | E. coli His-RpoA (1–329 plus A. tumefaciens RpoA C-terminal eight amino acids), Apr | This work |

| pADC | A. tumefaciens His-RpoA (1–242 amino acids), Apr | This work |

| pEN | E. coli His-RpoA (1–247 amino acids), Apr | This work |

| pENACN | His-RpoA (E. coli 1–247 amino acids plus A. tumefaciens 248–336), Apr | This work |

| pANEC | His-RpoA (A. tumefaciens 1–242 amino acids plus E. coli 243–329) | This work |

Plasmid constructs and DNA manipulations.

The plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Plasmids pZL2 and pECH are wild-type rpoA constructs from A. tumefaciens A136 (ropAAt) and E. coli MC4100 (rpoAEc), respectively (31). Plasmid pAD8 encodes N-terminal His-tagged RpoAAt with the eight C-terminal amino acids deleted and was constructed by PCR amplification from pPS1.3 using the primers 5′-GGA AGG ATC CAA GAT GAT TCA GAA GA-3′ and 5′-TTA GAG ATC TTC GAT GTT CTC AGG CGG-5′, followed by digestion with BamHI and ligation into pQE30 that was digested with BamHI and SmaI. Plasmid pEA8 encodes N-terminal His-tagged RpoAEc plus the eight C-terminal amino acids from RpoAAt fused to the C terminus. This plasmid was generated by inserting 24 nucleotides encoding the eight amino acids into the pECH by site-directed mutagenesis using oligonucleotide 5′-TAG AGG ATC GGG TTA GTA TTG GTC TTC GTA ACG CTT TGC CTC GTC AGC GAT GCT-3′. Plasmid pADC encodes N-terminal His-tagged RpoAAt with the C-terminal 94 amino acids deleted and was generated by PCR amplification of pPS1.3 using primers 5′-GGA AGG ATC CAA GAT GAT TCA GAA GA-3′ and 5′-TTA AGA TCT CGA TTC TTC TGC TTC CTT CTG-3′. The PCR product was digested with BamHI and ligated into pQE30 that was digested with BamHI and SmaI. The C-terminal domain of rpoAEc was amplified with primers 5′-GAA AGG ATC CAA ACC AGA GTT CGA TCC-3′ and 5′-CCT GGG ATC CGG TTA CTC GTC AGC-3′ using pECH as a template, and the PCR product was cleaved with BamHI and cloned into the BglII site of pADC, generating pANEC. To generate a hybrid RpoA containing the N-terminal domain from E. coli and the C-terminal domain from A. tumefaciens, each domain was PCR amplified. For PCR amplification of the N-terminal domain of RpoAEc, we used pECH as a template and primers that contain a BamHI site (5′-CCA AAG AGA GGA TCC AAT GCA GGG-3′) and a KpnI site (5′-CGG GGT ACC CTC TTC TTT CAC TTC AGG CTG ACG-3′), followed by digestion with BamHI and KpnI and ligation into pQE31, to generate pEN. To PCR amplify the C-terminal domain of RpoAAt, pPS1.3 was used as a template and oligonucleotides (5′-CGG GGT ACC GAA CTC GCG TTC AAC CCG GCG-3′ and 5′-CCT GGA TCC TGC AGA TGA CTT ATC TG-3′) were used as primers. The PCR product was digested with KpnI and ligated with pEN that was digested with KpnI and SmaI to generate pENACN.

A 1.7-kb PvuII fragment from pPC401 (25) containing lac promoter-driven virG was inserted into the SmaI site of pSW191, which is a pTZ18R derivative containing lacp-driven virA (54), resulting in pSG692. To generate pSL204, pSG692 was partially digested with PvuII and a 5.6-kb fragment containing lacp-driven virA and virG was gel purified. This fragment was ligated to EcoRI-digested pIB410 (virBp::lacZ) with the 3′ overhangs filled in by Klenow. lac-driven virG was deleted from pSL204 by digesting pSL204 with KpnI and religating the large fragment, resulting in pSJ0101. To construct pSJ0102, a 1.2-kb KpnI fragment from pSL204, containing lac-driven virG, was inserted into the KpnI site of pIB410. Construct pTC1.1 was generated by PCR amplification of A. tumefaciens chvE from strain A136 using primers 5′-GCG GGT ACC AGA GAA GGG CTC A-3′ and 5′-GAT GGT ACC AAG CCA TCC CCG C-3′, followed by ligation into pCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen), where chvE is under the control of lac promoter on the vector. To construct pTCR2.4, pBP3.0 containing lacp-driven A. tumefaciens rpoA (31) was digested with HindIII and StuI, the 3′ overhangs were filled in with Klenow, and a 1.3-kb fragment was gel purified. This fragment was ligated to pTC1.1 digested with EcoRV where rpoA was inserted in the same direction as chvE; thus, both genes are under the control of the lac promoter. For routine plasmid isolations, the Wizard Plus Miniprep DNA purification system (Promega) was used.

Virulence gene induction assays.

For reconstitution of virulence gene expression in E. coli, plasmid construct pSL204 was introduced into various E. coli strains by electroporation. Constructs containing either lacp-driven A. tumefaciens rpoA (pPS1.3 or pHO98) or non-lacp-driven rpoA (pPS1.3R) were then introduced into these strains and initially screened on MG/L medium (pH 6.0) containing appropriate antibiotics, 200 μM IPTG, 75 μg of X-Gal per ml, and 200 μM acetosyringone.

For quantitative assays of virBp::lacZ expression, E. coli strains containing the plasmids described above were grown to stationary phase in 5 ml of the appropriate medium, containing antibiotics as required. These cultures were used to inoculate 16- by 125-mm test tubes containing 5 ml of the same medium with inducers added where required using 50 μl of the starter culture as an inoculum. The cultures were incubated at either 28 or 37°C with shaking for 18 h and assayed for β-galactosidase activity according to the method of Miller (37).

RESULTS

C-terminal RpoA of A. tumefaciens is required to interact with the VirG protein.

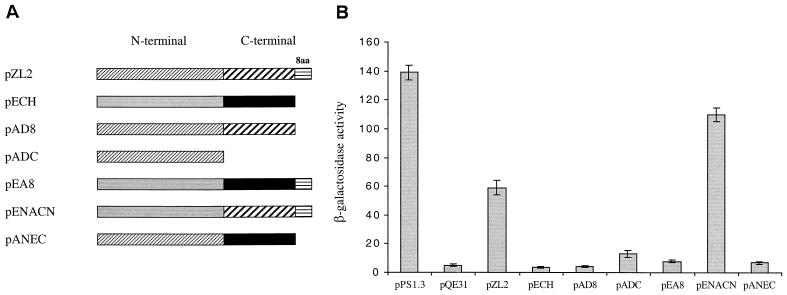

RpoA of E. coli is known to be composed of N- and C-terminal domains (12, 55). RpoA of A. tumefaciens shares 62% sequence similarity and 51% sequence identity with that of E. coli (31). An obvious difference between them is an extra eight amino acids in the C-terminal tail in the RpoA of A. tumefaciens. To determine which domain of the A. tumefaciens RpoA is required for interaction with the VirG protein, a series of protein fusion constructs were generated, and the abilities of the hybrid rpoA constructs to activate transcription of virBp::lacZ in a VirG(Con)-dependent manner in E. coli MC4100 and pSY215 were evaluated (Fig. 1A). When introduced into DH5α, all of the fusion constructs clearly overproduced protein bands with predicted sizes (data not shown), but only pENACN was able to provide significant expression of the virBp::lacZ fusion (Fig. 1B). The wild-type His-tagged A. tumefaciens RpoA construct pZL2 exhibited reduced expression of virBp::lacZ relative to both pPS1.3 (59% reduction) and pENACN (48% reduction). Deletion of 8 and 94 amino acids from the C terminus of A. tumefaciens RpoA (pAD8 and pADC, respectively) resulted in a complete loss of virBp::lacZ expression. Additionally, addition of the eight amino acids from the A. tumefaciens RpoA C terminus to the C terminus of E. coli RpoA (pEA8) also failed to activate transcription of virBp::lacZ. These results indicate that the C-terminal domain of the A. tumefaciens RpoA is required to interact with the VirG protein.

FIG. 1.

Abilities of various rpoA fusion constructs to activate vir gene expression in E. coli. (A) Schematic representation of gene fusions between rpoA of A. tumefaciens and E. coli. Hatched boxes represent RpoAAt, while shaded boxes represent RpoAEc. (B) β-Galactosidase activities of E. coli MC4100 harboring pSY215 and one of the rpoA constructs. Cultures were grown for 18 h in LB medium at pH 7.0 without acetosyringone. β-Galactosidase activity values are averages from three replicates.

Influence of rpoA copy number on expression of virBp::lacZ in E. coli.

We have constructed pSL204, which contains lac promoter-driven virA and virG, as well as a virBp::lacZ reporter gene fusion. This construct is compatible with the rpoAAt clones pHO98 and pPS1.3 (31). Transformation of DH5α containing pSL204 with pHO98 or pPS1.3 resulted in a blue color on MG/L and induction medium plates containing X-Gal and acetosyringone. No blue color was observed on identical medium in the absence of acetosyringone, indicating inducer-dependent expression of the virBp::lacZ fusion. In contrast, transformants containing the non-lacp-driven A. tumefaciens rpoA construct pPS1.3R did not exhibit any blue color on MG/L or induction medium containing X-Gal and acetosyringone.

To obtain a quantitative value for expression of the virBp::lacZ fusion, β-galactosidase activities were determined for DH5α containing pSL204 and either pHO98, pPS1.3, or pPS1.3R (Table 2). Both pPS1.3 and pHO98 conferred significant expression of virBp::lacZ in induction medium supplemented with 55 mM glycerol and 200 μM acetosyringone. The increases in β-galactosidase activity were approximately 4.6- and 30-fold, respectively, for pHO98 and pPS1.3, relative to the control DH5α containing pSL204 only. In contrast, there was no increase in β-galactosidase activity when pPS1.3R was used relative to that of the control. Deletion of either the virA or virG gene in pSL204, pSJ0101, and pSJ0102, , resulted in no expression of the virBp::lacZ gene (data not shown), suggesting a VirA-VirG-dependent phenomenon. Interestingly, significantly reduced β-galactosidase activity was observed when cultures were grown in induction medium supplemented with 55 mM glucose and 200 μM acetosyringone (∼95% reduction with pPS1.3). A similar level of reduction was seen when the strains were grown in induction medium supplemented with both glucose and glycerol as well as acetosyringone (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Effect of rpoA copy number on wild-type expression of virBp::lacZ in E. coli DH5α

| DH5α + plasmid: | U of β-galactosidase activity ina:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IM plus glucose

|

IM plus glycerol

|

IM plus glycerol plus glucose

|

||||

| −AS | +AS | −AS | +AS | −AS | +AS | |

| pSL204 | 1.3 | 2.3 | 0.2 | 4.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

| pSL204 and pHO98 | 1.4 | 2.6 | 1.2 | 20.8 | ND | ND |

| pSL204 and pPS1.3 | 1.9 | 7.2 | 3.1 | 136.5 | 1.5 | 7.3 |

| pSL204 and pPS1.3R | 2.5 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 3.0 | ND | ND |

Cultures were grown for 18 h in induction medium (IM) at pH 6.0 containing 55 mM glucose or glycerol or both, with (+) or without (−) 200 μM acetosyringone (AS) as indicated. Values are averages from three replicates and are expressed as units of β-galactosidase activity. ND, not determined.

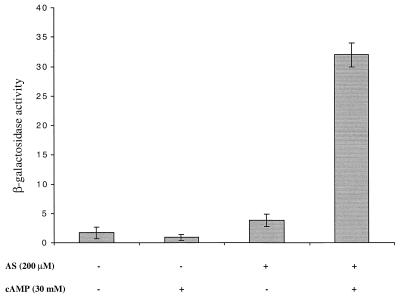

The inhibitory effect of glucose suggested to us the possible role of catabolite repression. Indeed, vir gene expression was abolished when the induction assays were carried out with a crp deletion mutant strain of E. coli, M182Δcrp, containing pSL204 and pPS1.3, whereas vir gene expression in the parent strain M182 containing pSL204 and pPS1.3 was similar to that in DH5α (Table 3). To test whether the cyclic AMP (cAMP) receptor protein (CRP) affects the virB promoter directly or the lac promoters that drive the expression of virA, virG, and rpoA, DH5α containing pSL204 and pPS1.3 was tested for the glucose effect in the presence of 30 mM cAMP, which activates genes under the control of CRP. Indeed, using 30 mM cAMP, a high level of β-galactosidase activity was induced in DH5α harboring pTZ18R where lacZα′ is under the control of the lac promoter (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 2, virBp::lacZ expression required both cAMP and acetosyringone, whereas cAMP or acetosyringone alone had no effect. These results suggest that the inhibitory effect of glucose is likely due to the catabolite repression of the lac promoter, which drives the expression of virA, virG, and rpoA genes, rather than to a direct effect on the virB promoter.

TABLE 3.

Expression of virBp::lacZ in an isogenic E. coli crp mutant background

| Strain | U of β-galactosidase activity ina:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IM plus glucose

|

IM plus glycerol

|

|||

| −AS | +AS | −AS | +AS | |

| M182(pSL204/pPS1.3) | 2.2 | 30.2 | 1.4 | 65.2 |

| M182(pSL204/pPS1.3R) | 1.1 | 3.6 | 5.1 | 6.4 |

| M182Δcrp(pSL204/pPS1.3) | 0 | 1.1 | 2.3 | 0.1 |

| M182Δcrp(pSL204/pPS1.3R) | 2.2 | 3.4 | 2.1 | 2.9 |

Cultures were grown for 18 h in induction medium at pH 6.0 (IM) containing 55 mM glucose or glycerol. Acetosyringone (AS) was added where indicated to a final concentration of 200 μM. Values are averages from three replicates and are expressed as units of β-galactosidase activity.

FIG. 2.

Effect of cAMP on the expression of virulence genes in E. coli. Strain DH5α harboring both pSL204 and pPS1.3 was grown in induction medium containing 55 mM glucose. The medium was supplemented with 200 μM acetosyringone, 30 mM cAMP, or both. β-Galactosidase activity values are the average of three replicates.

Effect of other virulence gene inducers on the expression of virBp::lacZ in DH5α.

It is known that vir genes of different A. tumefaciens strains respond to different sets of phenolic compounds depending on the origin of the VirA molecules. The virA of pSL204 is derived from strain A348, whose vir gene expression is activated by acetosyringone, acetovanillone, and syringealdehyde but not by hydroxyacetophenone (29). The ability of DH5α containing pSL204 and pPS1.3 to express virBp::lacZ in response to these inducing compounds was evaluated. DH5α containing pSL204 with or without pPS1.3 were grown in induction medium amended with glycerol and with one of the following inducers: acetosyringone, acetovanillone, hydroxyacetophenone, or syringealdehyde. Significant levels of virBp::lacZ expression were obtained with DH5α containing pPS1.3 when acetosyringone and syringealdehyde were present. Low-level expression was detected in the presence of acetovanillone, and no induction was seen when hydroxyacetophenone was present (Table 4). Similarly, a Ti plasmidless A. tumefaciens strain, A136, harboring pSL204 responded strongly to acetosyringone and syringealdehyde and weakly to acetovanillone, but not at all to hydroxyacetophenone (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Wild-type expression of virBp::lacZ in DH5α in response to other inducers

| Strain | U of β-galactosidase activity plus (inducer)a:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | AS | AV | HAP | SYR | |

| DH5α(pSL204) | 3.8 | 9.7 | 4.4 | 1.0 | 5.0 |

| DH5α(pSL204/pPS1.3) | 0.8 | 137 | 12.3 | 0.7 | 120 |

| A136(pSL204) | 15.6 | 856 | 189 | 14.1 | 795 |

Cultures were grown for 18 h in induction medium at pH 6.0 containing 55 mM glycerol. Inducers were added to a final concentration of 200 μM. Values are averages from three replicates and are expressed as units of β-galactosidase activity. AS, acetosyringone; AV, acetovanillone; HAP, hydroxyacetophenone; SYR, syringealdehyde.

Inducer-dependent virBp::lacZ expression in DH5α is affected by pH, temperature, and choice of media.

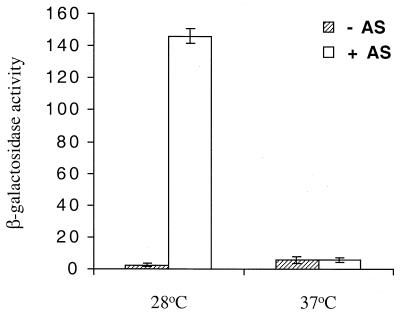

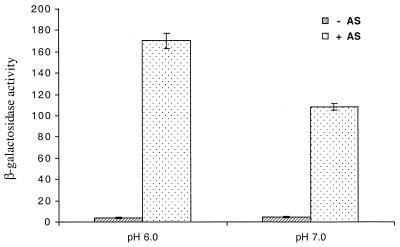

To assess whether the expression of the virBp::lacZ in E. coli is responding to the same environmental signals that affect vir expression in A. tumefaciens, the effect of variations in temperature and pH were examined. When DH5α cells containing pSL204 with or without pPS1.3 were grown in induction medium containing acetosyringone and glycerol at 28 or 37°C, high-level expression was observed at 28°C but not at 37°C (Fig. 3). When the same strains were assayed for virBp::lacZ expression in induction medium at pH 6.0 and 7.0, there was approximately a 36% reduction in β-galactosidase activity when the bacterium was grown at pH 7.0 compared to when it was grown at pH 6.0 (Fig. 4).

FIG. 3.

Effect of temperature on the expression of the virB::lacZ fusion in E. coli. Strain DH5α harboring both pSL204 and pPS1.3 was grown for 18 h in induction medium (pH 6.0) containing 55 mM glycerol at either 28 or 37°C. Acetosyringone (AS) was added where indicated at a final concentration of 200 μM. β-Galactosidase activity values are average from three replicates.

FIG. 4.

Effect of pH on the expression of virB::lacZ expression in E. coli. Strain DH5α containing both pSL204 and pPS1.3 was grown for 18 h in induction medium, at pH 6.0 or 7.0, containing 55 mM glycerol with (+) or without (−) 200 μM acetosyringone (AS). β-Galactosidase activity values are averages from three replicates.

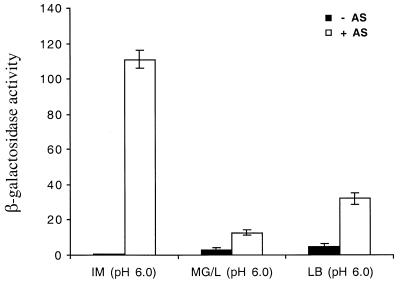

To evaluate the effect of rich, complex medium on virBp::lacZ expression, induction assays were carried out in MG/L and LB media at pH 6.0 in the presence or absence of acetosyringone. Overall, expression levels were significantly lower than what was obtained with induction medium supplemented with glycerol. The levels of induction were approximately 4.5- and 7-fold with MG/L and LB media, respectively, compared to that of the control without acetosyringone (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Effect of growth media on the expression of virB::lacZ expression in E. coli. Strain DH5α containing both pSL204 and pPS1.3 was grown for 18 h in induction medium containing 55 mM glycerol (IM) or MG/L or LB medium at pH 6.0. Acetosyringone (AS) was added where indicated at a 200 μM final concentration. β-Galactosidase activity values are averages from three replicates.

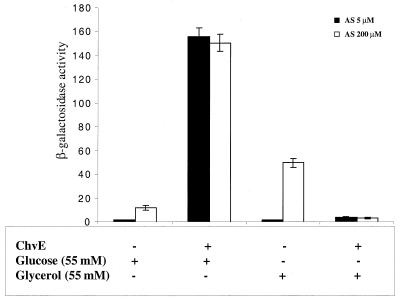

Effect of chvE on virBp::lacZ expression.

To evaluate whether chvE from A. tumefaciens can increase virBp::lacZ expression in E. coli, we introduced pTCR2.4, which contains lacp-driven chvE and lacp-driven rpoA of A. tumefaciens into DH5α containing pSL204 and compared virBp::lacZ expression with that of DH5α containing pSL204 and pPS1.3. To avoid the inhibitory effect of the glucose on the lac promoter driving the expression of virA, virG, and rpoA, 30 mM cAMP was added to the induction medium. As shown in Fig. 6, the virBp::lacZ expression level was highest in the presence of both ChvE and glucose, suggesting that similar interactions between VirA and sugar-bound ChvE also occur in E. coli, which enhances the sensitivity of VirA to the acetosyringone signal. As in A. tumefaciens, the presence of glucose and ChvE sensitizes the VirA molecule, resulting in a high level of virBp::lacZ expression in the presence of a low concentration of acetosyringone (5 μM), whereas in the absence of ChvE, virBp::lacZ responded only to a high level of acetosyringone (200 μM) (Fig. 6). The fact that no glucose effect was detected in the absence of chvE indicates that the glucose-binding protein of E. coli is incapable of interacting with the VirA, although there is significant amino acid sequence homology between the ChvE and the E. coli glucose-binding protein (5).

FIG. 6.

Effect of sugar and ChvE on the expression of virB::lacZ in E. coli. Strain DH5α harboring pSL204 and either pZL2, which contains rpoA of A. tumefaciens, or pTC2.4, which contains both lac-promoter driven rpoA and chvE. Bacterial cultures were grown for 18 h in induction medium supplemented with 30 mM cAMP and either 55 mM glucose or glycerol. Acetosyringone (AS) was added at either a 5 or a 200 μM final concentration. β-Galactosidase activity values are averages from three replicates.

DISCUSSION

For many years it was believed that the specificity of RNA polymerase for promoters was determined by various sigma factors. Beginning in the early 1990s it was demonstrated that rpoA, encoding the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase, plays an essential role in the transcription of many operons in E. coli controlled by transcriptional regulators such as FNR (51), GalR (11), MarA (20), MerR (9, 26), MetR (18), OxyR (48), OmpR (17), Rob (21), SoxS (19), UhpA (39), and TyrR (28). Recently, it has become clear that RpoA also plays an essential role in transcription in other bacterial systems such as Agrobacterium tumefaciens (31), Bacillus subtilis (35, 38), Bordetella pertussis (6, 46), Rhodospirullum rubrum (13), Pseudomonas putida (33), and Vibrio fischeri (47).

Similar to results obtained for other transcriptional regulators in other bacterial systems, the results of the domain swap indicate the importance of the C-terminal domain of A. tumefaciens rpoA in VirG-mediated transcription from virB promoters (35, 46). The ability of pENACN to allow virBp::lacZ expression indicates that the residues essential for transcription are located in the C-terminal 89 amino acids of A. tumefaciens RpoA. Interestingly, deletion of eight residues from the C terminus of A. tumefaciens RpoA abolished virB::lacZ transcription, indicating an essential role for these residues. However, when these eight residues were added to the C terminus of E. coli RpoA, we did not obtain any transcription, indicating that while this region is essential for transcription, other determinants in the C-terminal region are also required. As expected, deletion of the C-terminal 94 amino acids from A. tumefaciens RpoA (pADC) or replacement with the C-terminal domain of E. coli RpoA (pANEC) failed to result in any expression of the virBp::lacZ fusion. The reduced virBp::lacZ expression obtained with the wild-type His-tagged A. tumefaciens RpoA indicates that the N-terminal histidine residues are interfering with RpoA function. Interestingly, pENACN gave intermediate levels of virBp::lacZ expression even though it contains the N-terminal domain of E. coli RpoA from pECH, which contains an N-terminal His tag plus the C-terminal domain of A. tumefaciens. This suggests that an N-terminal His tag negatively affects A. tumefaciens RpoA function to a greater degree than for E. coli RpoA, at least at the virB promoter.

Another purpose of this study was to determine if we could reconstitute wild-type, inducer-dependent A. tumefaciens virulence gene expression in the heterologous host E. coli. In a previous study (31), we were unable to detect acetosyringone-mediated expression of virBp::lacZ in E. coli MC4100 using the constructs pHO98 (lacp::rpoA) and pSL107 (lacp::virA/G, virBp::lacZ). The pSL107 plasmid used in that study was not stable and resulted in high-frequency spontaneous mutations, probably due to the presence of two replicons (ColE1 and IncP origin) (data not shown). In response to this finding, we constructed pSL204, which also contains lacp-driven virA and virG, virBp::lacZ, and in contrast to pSL107, only the IncP origin. This allowed us to utilize the high-copy-number plasmid pPS1.3 in our attempts to reconstitute inducer-dependent virBp::lacZ expression in E. coli. Introduction of either pHO98 or pPS1.3 into DH5α containing pSL204 resulted in significant expression of the virBp::lacZ fusion in the presence of acetosyringone. The higher level of expression observed with pPS1.3 most likely is the result of an increase in the copy number of rpoA compared to that in pHO98.

The expression of virulence genes in A. tumefaciens is known to be affected by changes in temperature (23) and pH (32), with 28°C and pH 5.5 being optimal. The thermosensitive nature of virulence expression in A. tumefaciens is due to a reversible inactivation of VirA protein (23). Similar to what is observed in A. tumefaciens, we have also seen virBp::lacZ expression at 28°C, while no expression was observed at 37°C. In addition, we demonstrated that virBp::lacZ expression in DH5α is also affected by pH, with a 36% decrease in expression at pH 7.0 compared with that seen at pH 6.0. We did not use pH 5.5, since the growth of DH5α was adversely affected by this pH. Taken together, these results reinforce our conclusion that we have obtained inducer-dependent virBp::lacZ expression in E. coli and that the VirA-VirG signaling mechanism appears to be functioning.

Our observation that the choice of sugar greatly influences virBp::lacZ expression in DH5α is indicative of catabolite repression. To confirm this, we utilized the isogenic E. coli strains M182 and M182Δcrp (3, 4, 8), which differ only in the presence of the cAMP receptor gene crp. Our observation that virBp::lacZ expression in M182Δcrp was dramatically reduced in induction medium amended with glycerol confirms the requirement of CRP. Since the addition of cAMP alone in the induction medium did not induce virBp::lacZ expression, the CRP may not directly activate the virB promoter. The fact that both cAMP and acetosyringone are needed for virBp::lacZ expression suggests that the CRP is required for the expression of virA, virG, and rpoA that are under the control of the lac promoter, a well-characterized promoter that requires activation by CRP. An alternative promoter that is not influenced by CRP or any other factors might be needed to further clarify this.

One unresolved question in virulence gene expression is the exact mechanism of sensing of phenolic inducers by the VirA-VirG system. The two possibilities are either a direct binding of the inducer by VirA or an intermediate receptor protein that binds the inducer and then interacts with VirA. Although the genetic evidence supporting direct binding of inducers by VirA has been reported (29, 30), all attempts to demonstrate direct binding by VirA have been unsuccessful. We were able to demonstrate significant expression of virBp::lacZ in response to acetosyringone, syringealdehyde and, to a lesser extent, acetovanillone but not to hydroxyacetophenone. This result provides further evidence that inducers may be recognized directly by VirA. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that E. coli may contain homologues of A. tumefaciens receptors for the phenolic inducers. In the case of sugar effect, given the fact that E. coli encodes a ChvE homologue, the profound effect of ChvE and sugar on virBp::lacZ expression was somewhat unexpected. Apparently, VirA can be sensitized only by sugar- bound ChvE but not by the glucose-binding protein of E. coli which shares significant amino acid homology with ChvE (5).

Taken together, these results provide conclusive evidence that we have indeed reconstituted inducer-dependent vir gene expression in E. coli. However, the level of expression in E. coli is still significantly less than what is usually observed in A. tumefaciens (29, 30). One possible explanation for the relatively low induction in E. coli may be the E. coli sigma factors, which are inefficient in recognizing the vir gene promoters. It is conceivable that E. coli sigma factors may have a lower affinity for the virB promoter than sigma factors from A. tumefaciens. Although the vegetative sigma factor from A. tumefaciens has been identified (42), it is unclear whether this or an alternative sigma factor is involved in vir gene transcription. It is also likely that the relatively low expression is a consequence, at least in part, of RNA polymerase-containing endogenous E. coli RpoA subunits. One approach to resolve this would be to engineer E. coli RpoA such that it is able to activate virBp::lacZ expression. The results of our domain swap experiments have demonstrated that it is possible to obtain a hybrid RpoA molecule that will function at vir promoters, although the effect of such hybrids on the transcription of E. coli genes is unclear. In a recent study, Carbonetti et al. (6) reported that, in B. pertussis, overexpression of RpoABp reduced the transcription of Bvg-activated virulence genes. It was suggested that excess RpoABp was able to interact with Bvg and prevent interaction with virulence promoters. Since we previously reported that RpoA from A. tumefaciens, but not from E. coli, is able to interact with VirG (31), it may be that the constructs we are using result in cellular levels of A. tumefaciens RpoA that bind VirG and prevent optimal transcription. Although the current level of expression in E. coli is relatively low, it may still be sufficient to begin studies on A. tumefaciens processes in E. coli such as T-DNA transfer. Studies are under way to address these possibilities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Nigel Savery of the University of Bristol for the generous gift of E. coli strains M182 and M182Δcrp.

This work is supported by NSF grant MCB-972227.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akiyoshi D E, Klee H, Amasino R M, Nester E W, Gordon M P. T-DNA of Agrobacterium tumefaciens encodes an enzyme of cytokinin biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:5994–5998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.19.5994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ankenbauer R G, Nester E W. Sugar-mediated induction of Agrobacterium tumefaciens virulence genes: structural specificity and activities of monosaccharides. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6442–6446. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6442-6446.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Busby S, Ebright R H. Transcription activation at class II CAP-dependent promoters. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:853–859. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2771641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Busby S, Kotlarz D, Buc H. Deletion mutagenesis of the Escherichia coli galactose operon promoter region. J Mol Biol. 1983;167:259–274. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80335-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cangelosi G A, Ankenbauer R G, Nester E W. Sugars induce the Agrobacterium virulence genes through a periplasmic binding protein and a transmembrane signal protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6708–6712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carbonetti N H, Romashko A, Irish T J. Overexpression of the RNA polymerase alpha subunit reduces transcription of Bvg-activated virulence genes in Bordetella pertussis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:529–531. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.2.529-531.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casadaban M J. Regulation of the regulatory gene for the arabinose pathway, araC. J Mol Biol. 1976;104:557–566. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90120-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casadaban M J, Cohen S N. Analysis of gene control signals by DNA fusion and cloning in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1980;138:179–207. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(80)90283-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caslake L F, Ashraf S I, Summers A O. Mutations in the alpha and sigma-70 subunits of RNA polymerase affect expression of the mer operon. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1787–1795. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1787-1795.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charles T C, Nester E W. A chromosomally encoded two-component sensory transduction system is required for virulence of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6614–6625. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.20.6614-6625.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choy H E, Park S W, Aki T, Parrack P, Fujita N, Ishihama A, Adhya S. Repression and activation of transcription by Gal and Lac repressors: involvement of alpha subunit of RNA polymerase. EMBO J. 1995;14:4523–4529. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00131.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebright R H, Busby S. The Escherichia coli RNA polymerase alpha subunit: structure and function. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1995;5:197–203. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(95)80008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He Y, Gaal T, Karls R, Donohue T J, Gourse R L, Roberts G P. Transcription activation by CooA, the CO-sensing factor from Rhodospirillum rubrum: the interaction between CooA and the C-terminal domain of the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10840–10845. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hiei Y, Ohta S, Komari T, Kumashiro T. Efficient transformation of rice (Oryza sativa L.) mediated by Agrobacterium and sequence analysis of the boundaries of the T-DNA. Plant J. 1994;6:271–282. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1994.6020271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang M L, Cangelosi G A, Halperin W, Nester E W. A chromosomal Agrobacterium tumefaciens gene required for effective plant signal transduction. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1814–1822. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.4.1814-1822.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang Y, Morel P, Powell B, Cado C I. VirA, a coregulator of Ti-specific virulence genes, is phosphorylated in vitro. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1142–1144. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.1142-1144.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Igarashi K, Hanamura A, Makino K, Aiba H, Aiba H, Mizuno T, Nakata A, Ishihama A. Functional map of the alpha subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase: two modes of transcription activation by positive factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8958–8962. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.8958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jafri S, Urbanowski M L, Stauffer G V. A mutation in the rpoA gene encoding the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase that affects metE-metR transcription in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:524–529. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.3.524-529.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jair K W, Fawcett W P, Fujita N, Ishihama A, Wolf R E., Jr Ambidextrous transcriptional activation by SoxS: requirement for the C-terminal domain of the RNA polymerase alpha subunit in a subset of Escherichia coli superoxide-inducible genes. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:307–317. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.368893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jair K W, Martin R G, Rosner J L, Fujita N, Ishihama A, Wolf R E., Jr Purification and regulatory properties of MarA protein, a transcriptional activator of Escherichia coli multiple antibiotic and superoxide resistance promoters. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:7100–7104. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.24.7100-7104.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jair K W, Yu X, Skarstad K, Thony B, Fujita N, Ishihama A, Wolf R E., Jr Transcriptional activation of promoters of the superoxide and multiple antibiotic resistance regulons by Rob, a binding protein of the Escherichia coli origin of chromosomal replication. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2507–2513. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.9.2507-2513.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin S, Roitsch T, Ankenbauer R G, Gordon M P, Nester E W. The VirA protein of Agrobacterium tumefaciens is autophosphorylated and is essential for vir gene regulation. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:525–530. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.525-530.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin S, Song Y N, Deng W Y, Gordon M P, Nester E W. The regulatory VirA protein of Agrobacterium tumefaciens does not function at elevated temperatures. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6830–6835. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.21.6830-6835.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin S G, Prusti R K, Roitsch T, Ankenbauer R G, Nester E W. Phosphorylation of the VirG protein of Agrobacterium tumefaciens by the autophosphorylated VirA protein: essential role in biological activity of VirG. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4945–4950. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.9.4945-4950.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin S G, Roitsch T, Christie P J, Nester E W. The regulatory VirG protein specifically binds to a cis-acting regulatory sequence involved in transcriptional activation of Agrobacterium tumefaciens virulence genes. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:531–537. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.531-537.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kulkarni R D, Summers A O. MerR cross-links to the alpha, beta, and sigma 70 subunits of RNA polymerase in the preinitiation complex at the merTPCAD promoter. Biochemistry. 1999;38:3362–3368. doi: 10.1021/bi982814m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lai E M, Kado C I. The T-pilus of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:361–369. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01802-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lawley B, Fujita N, Ishihama A, Pittard A J. The TyrR protein of Escherichia coli is a class I transcription activator. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:238–241. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.1.238-241.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee Y-W, Jin S, Sim W-S, Nester E W. Genetic evidence for direct sensing of phenolic compounds by the VirA protein of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:12245–12249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee Y W, Jin S, Sim W S, Nester E W. The sensing of plant signal molecules by Agrobacterium: genetic evidence for direct recognition of phenolic inducers by the VirA protein. Gene. 1996;179:83–88. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00328-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lohrke S M, Nechaev S, Yang H, Severinov K, Jin S J. Transcriptional activation of Agrobacterium tumefaciens virulence gene promoters in Escherichia coli requires the A. tumefaciens RpoA gene, encoding the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4533–4539. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.15.4533-4539.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mantis N J, Winans S C. The Agrobacterium tumefaciens vir gene transcriptional activator virG is transcriptionally induced by acid pH and other stress stimuli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1189–1196. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.4.1189-1196.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McFall S M, Chugani S A, Chakrabarty A M. Transcriptional activation of the catechol and chlorocatechol operons: variations on a theme. Gene. 1998;223:257–267. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00366-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melchers L S, Regensburg T T J, Bourret R B, Sedee N J, Schilperoort R A, Hooykaas P J. Membrane topology and functional analysis of the sensory protein VirA of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. EMBO J. 1989;8:1919–1925. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03595.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mencia M, Monsalve M, Rojo F, Salas M. Substitution of the C-terminal domain of the Escherichia coli RNA polymerase alpha subunit by that from Bacillus subtilis makes the enzyme responsive to a Bacillus subtilis transcriptional activator. J Mol Biol. 1998;275:177–185. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Messens E, Lenaerts A, Van M M, Hedges R W. Genetic basis for opine secretion from crown gall tumour cells. Mol Gen Genet. 1985;25:344–348. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller J H. Assay of β-galactosidase. In: Miller J H, editor. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratories; 1972. pp. 352–355. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monsalve M, Calles B, Mencia M, Rojo F, Salas M. Binding of phage phi29 protein p4 to the early A2c promoter: recruitment of a repressor by the RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol. 1998;283:559–569. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olekhnovich I N, Kadner R J. RNA polymerase alpha and sigma(70) subunits participate in transcription of the Escherichia coli uhpT promoter. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:7266–7273. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.23.7266-7273.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pazour G J, Das A. Characterization of the VirG binding site of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6909–6913. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.23.6909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Segal G, Ron E Z. Cloning, sequencing, and transcriptional analysis of the gene coding for the vegetative sigma factor of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3026–3030. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.3026-3030.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimoda N, Toyoda-Yamamoto A, Nagamine J, Usami S, Katayama M, Sakagami Y, Machida Y. Control of expression of Agrobacterium vir genes by synergistic actions of phenolic signal molecules and monosaccharides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6684–6688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stachel S E, Nester E W, Zambryski P C. A plant cell factor induces Agrobacterium tumefaciens vir gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:379–383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.2.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stachel S E, Zambryski P C. virA and virG control the plant-induced activation of the T-DNA transfer process of A. tumefaciens. Cell. 1986;46:325–333. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90653-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steffen P, Ullmann A. Hybrid Bordetella pertussis-Escherichia coli RNA polymerases: selectivity of promoter activation. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1567–1569. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.6.1567-1569.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stevens A M, Fujita N, Ishihama A, Greenberg E P. Involvement of the RNA polymerase alpha-subunit C-terminal domain in LuxR-dependent activation of the Vibrio fischeri luminescence genes. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4704–4707. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.15.4704-4707.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tao K, Zou C, Fujita N, Ishihama A. Mapping of the OxyR protein contact site in the C-terminal region of RNA polymerase alpha subunit. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6740–6744. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.23.6740-6744.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thomashow M F, Hugly S, Buchholz W G, Thomashow L S. Molecular basis for the auxin-independent phenotype of crown gall tumor tissues. Science. 1986;231:616–618. doi: 10.1126/science.3511528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Watson B, Currier T C, Gordon M P, Chilton M D, Nester E W. Plasmid required for virulence of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 1975;123:255–264. doi: 10.1128/jb.123.1.255-264.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Williams S M, Savery N J, Busby S J, Wing H J. Transcription activation at class I FNR-dependent promoters: identification of the activating surface of FNR and the corresponding contact site in the C-terminal domain of the RNA polymerase alpha subunit. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4028–4034. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.20.4028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Winans S C, Ebert P R, Stachel S E, Gordon M P, Nester E W. A gene essential for Agrobacterium virulence is homologous to a family of positive regulatory loci. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:8278–8282. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.21.8278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Winans S C, Kerstetter R A, Nester E W. Transcriptional regulation of the virA and virG genes of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4047–4054. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4047-4054.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Winans S C, Kerstetter R A, Ward J E, Nester E W. A protein required for transcriptional regulation of Agrobacterium virulence genes spans the cytoplasmic membrane. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:1616–1622. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.3.1616-1622.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang G, Darst S A. Structure of the Escherichia coli RNA polymerase alpha subunit amino-terminal domain. Science. 1998;281:262–266. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5374.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhu J, Oger P M, Schrammeijer B, Hooykaas P J, Farrand S K, Winans S C. The bases of crown gall tumorigenesis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3885–3895. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.14.3885-3895.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]