Abstract

A multidisciplinary guideline development group was established to formulate this evidence-based diagnosis and treatment guidelines for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in China. The grading of recommendations, assessment, development, and evaluation (GRADE) system was used to rate the quality of the evidence and the strength of recommendations, which were derived from research articles and guided by the analysis of the benefits and harms as well as patients’ values and preferences. A total of 10 recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of RA were developed. This new guideline covered the classification criteria, disease activity assessment and monitoring, and the role of disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), biologics, small molecule synthetic targeting drugs, and glucocorticoids in the treat-to-target approach of RA. This guideline is intended to serve as a tool for clinicians and patients to implement decision-making strategies and improve the practices of RA management in China.

Keywords: arthritis, diagnosis, guideline, rheumatoid, therapy

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune disease with destructive arthritis as its main clinical manifestation and can occur at any age.[1, 2] Although the pathogenesis is unclear, synovitis, pannus formation, joint cartilage, and bone damage gradually occur, resulting in joint malformations and loss of function.[3, 4] RA can also present with lung and cardiovascular damage; in some patients RA may have complications such as malignancy and depression.[4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10] Epidemiological surveys have shown that the incidence rate of RA is 0.5–1% globally[1] and 0.42% in mainland China. Based on this epidemiological data, it is estimated that the total number of RA patients in mainland China is 5 million,[11] The ratio of men to women with RA is approximately 1:4.[12, 13]

The disability rate of Chinese RA patients increases along with disease duration. For patients with 1–5 years of disease, the disability rate is 18.6%, for patients with 5–10 years of disease, the disability rate is 43.5%, for patients with 10–15 years of disease, the mortality rate is 48.1%, for patients with the disease for more than 15 years, the disability rate is 61.3%.[12] The rate of disability and functional restriction also increases with disease progression. Importantly, RA impacts physical fitness, quality of life, social participation of patients, and creates a huge financial burden on both families and society.[11, 14, 15]

In recent years, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR), the Asia-Pacific League of Associations for Rheumatology (APLAR), and other international academic organizations in rheumatology developed or revised their RA management guideline.[16, 17, 18] Chinese Rheumatology Association published China practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of RA in 2010.[19] Despite the growing number of guidelines released internationally, the diagnosis and treatment of RA still faces many challenges in China because of the limitations of applying these guidelines in real-world clinical practice. One reason is that the quality of the international recommendations for RA is incomparable and some recommendations are inconsistent.[20] Another reason is that most of the international guidelines did not include the epidemiological and clinical research on Chinese RA patients. Furthermore, the focus of the diagnostic, treatment, and prescription practices in China is somewhat different from other countries[13, 20, 21] due to the differences in rheumatologists’ training programs, specialty settings, and behavior patterns of Chinese patients. Surveys have shown that about 60% of hospitals in China do not have a standalone rheumatology department, and more than 80% of the existing 7200 rheumatologists work in tertiary hospitals,[22] leading to limited access to rheumatologists for treatment and diagnosis of patients who live in small cities and rural area. Surveys have revealed that only 23% of RA patients visit rheumatologists when they had the first symptom suggesting the diagnosis of RA.[23]

Therefore, the formulation and implementation of practical RA guideline that conform to local situation will play a vital role in improving the management capability of physicians (e.g., rheumatologists, orthopedists, and internists), especially those working at county-level and primary care institutions, to make correct diagnosis and treatment for RA, to emphasize patient education, and to improve the quality of diagnosis and treatment of RA in China. Thus, based on new evidences and experiences from domestic rheumatologists and studies, taking the preferences and values of Chinese patients into consideration and balancing the benefits and risks of each recommended intervention, the Chinese Rheumatology Association developed the “2018 Chinese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of RA”.

Recommendation 1: Early diagnosis has a significant impact on the treatment and prognosis of RA, so clinicians need to make the diagnosis promptly based on patient's clinical presentations, laboratory tests, and imaging examinations (1A). The 1987 ACR and 2010 ACR/EULAR classification criteria (2B) for RA are recommended as the reference for RA diagnosis.

Surveys have shown that the median time from the onset of typical symptoms of RA such as multiple joint swelling and morning stiffness to the diagnosis of RA may take up to 6 months in China. It takes more than 1 year to be diagnosed in as many as 25% of patients.[23] The timing of diagnosis will directly affect the treatment effectiveness and prognosis of RA. Therefore, early diagnosis shall be based on patient's clinical presentations, laboratory tests, and imaging examinations results. Currently, there are 2 international classification criteria used to help diagnosing RA: one is “The 1987 ACR classification criteria,” which has the sensitivity of 39.1% and the specificity of 92.4%,[24, 25] and the other one is “The 2010 ACR/EULAR classification criteria,” which has a sensitivity of 72.3% and a specificity of 83.2%.[25, 26] Given the specific advantages of each criteria in terms of sensitivity and specificity, clinicians can refer to both as references to make accurate diagnosis of RA based on specific characteristics of Chinese RA patients.[25]

Recommendation 2: We recommend that clinicians choose the most suitable imaging modalities such as X-rays, ultrasound, (computerized tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (2B) based on the specific signs and symptoms of the patient (2B).

Imaging examinations are effective tools to assist clinicians to make the diagnosis of RA. The value for diagnosis and disease monitoring as well as the advantages of various imaging modalities are listed in Table 1.[19, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32] EULAR issued an evidence-based recommendation for selecting imaging modalities for RA diagnosis in 2013. This recommendation greatly aids clinicians to choose appropriate image modalities to make correct diagnosis.[28] It should be noted that Chinese RA patients may go to various levels of medical institutes seeking care, which is very different from that of foreign countries. In addition, there are considerable differences in the availability of imaging equipment and technology in different regions of the country; therefore, clinicians should choose the most suitable diagnostic imaging modalities available locally to assist in making the diagnosis.

Table 1.

The value of imaging modalities in the diagnostics, follow up, and monitoring of RA

| Image modalities | Applied situations | Advantages[27] | Disadvantages[27] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regular radiologic examination | Regular radiologic examinations are the most commonly used imaging tools for assessing structural damage of RA joints.[27] X-rays of hands, wrists, and other affected joints are important for the diagnosis of RA. Early X-rays showed swelling of soft tissue around the joint and osteoporosis near the joint. As the disease progresses, it will show joint surface damage, stenosis of joint gaps, joint fusion, or dislocation.[19] Joint injuries could be regularly assessed by hand and foot X-rays. However, routine X-rays in patients with RA whose disease course is less than half year may be normal.[28] |

|

|

| Ultrasound | Ultrasound detects joint structural damage with higher sensitivity than conventional radiological examinations.[27] Doppler ultrasound can be used to confirm the presence of synovitis, monitor disease activity and progression, and assess inflammation.[28–29] Ultrasound can clearly show synovium, synovial bursa, joint fluid, joint cartilage thickness, morphology, etc. Color Doppler blood flow imaging (CDFI) and color Doppler energy (CDE) can directly detect the distribution of blood flow in joint tissues, reflecting inflammation of synovium with high sensitivity. Ultrasound can also dynamically determine the amount of joint fluid and the distance from the body surface to guide joint aspiration and treatment.[19] |

|

|

| CT | CT can detect bone erosion more accurately than other modalities. It is valuable particularly in large joint lesions and lung disease, but CT cannot detect active inflammation in synovitis, tenosynovitis, for example.[19] Thus when intend to detect large joints involvement or lung lesions, CT can be used to monitor the disease. |

|

|

| MRI | MRI is the most sensitive tool to detect early RA lesions.[27] MRI is superior to X-rays in showing joint lesions because it can detect thickening of synovium, bone marrow edema, and early mild articular surface erosions, and thus helps in early diagnosis of RA.[19] MRI can detect joint changes much earlier than conventional radiological modalities such as synovitis, joints narrowing, and bone erosion.[31] MRI can detect inflammation even earlier than physical examination, so it can be used to identify subclinical inflammation and predict whether the current undifferentiated arthritis may progress to RA. MRI can also be used to predict future joint damage in clinically remission patients. Bone marrow edema has been shown to be one of the powerful independent predictive factors for early RA imaging progression and can be used as one of the prognostic indicators.[28, 32] |

|

|

CT, computerized tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Recommendation 3: The principles of management of RA are early, standardized treatment, regular monitoring, and follow up (1A). The goal of RA treatment is to achieve disease remission or lower disease activity, that is, to treat the disease to the target. The overall goal of treatment is to control the disease activity, reduce disability, and improve patients’ quality of life (1B).

The joint lesions of RA are caused by inflammatory cell infiltration and release of inflammatory factors.[1] To inhibit the production of cytokines and their effects as early as possible can effectively prevent or minimize the destructions in joint synovium and cartilage.[1] Therefore, timely treatment should be carried out as soon as the diagnosis is made. Indeed, studies have shown that irregular use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) is one of the independent risk factors for joint function limitation in RA patients.[12]

Although RA is not curable, the treat-to-target strategy is effective in alleviating symptoms and controlling the disease progression.[33] Treat-to-target is referred to treat to achieve clinical remission, i.e., 28 joint disease activity (DAS28) ≤ 2.6, or clinical disease activity index (CDAI) ≤ 2.8, or simplified disease activity index (SDAI) ≤ 3.3. When the above criteria cannot be met, low disease activity can be the alternative treatment target, i.e., DAS28 ≤ 3.2, CDAI ≤ 10 or SDAI ≤ 11. However, it should be noted that there are limitations in the disease activity evaluation tools and studies have shown that RA patients with swollen joints can still suffer further joint damage even when their DAS28 score is less than 2.6.[34] In 2011, the ACR and EULAR proposed new remission criteria, which included tender joint count, swollen joint count, C-reactive protein (CRP) level, and patient global assessment were all ≤ 1.[35] Due to its high specificity and the ease of use and implementation, the criteria has been gradually adopted in clinical practice. Nevertheless, remission rate based on this new criterion is low,[36] so clinicians should choose the appropriate evaluation criteria according to their real practice situation.

Recommendation 4: For patients who do not achieve the treatment target, we recommend to monitor their disease activity once every 1–3 months (2B). For patients who are treatment naïve and patients with moderate/high disease activity, we recommend to monitor their disease once every month (2B). For patients who have reached the treatment target, we recommend to monitor their disease once every 3–6 months (2B).

For treatment naïve patients, we recommend to monitor their disease once every month due to the slow onset of action of DMARDs and the frequency of adverse reactions. For patients who encounter difficulties with the schedule, monitoring can be done every 3 months. However, randomized controlled trials have shown that monitoring and adjusting the medication regimen monthly can further decrease disease activity, delay radiological progression, and improve the function and quality of life compared to the regimen done once every 3 months.[37] Other randomized controlled studies have revealed that significant progression of joint damage can happen within 3 months in patients with moderate/high disease activity. For these patients, we recommend the frequency of monitoring as once per month. The monitoring frequency for patients who have reached the therapeutic target can be adjusted to be once every 3–6 months.[29, 38, 39]

A systematic review comprehensively analyzed the existing 63 RA disease monitoring and evaluation tools, including comparison for credibility, effectiveness, and responsiveness of DAS28, SDAI, and CDAI. The results showed that DAS28 was better in all 3 aspects.[33] For laboratory tests, CRP was shown to have several advantages when compared to ESR, including more sensitive to inflammation and less susceptible to other factors such as age, sex, and rheumatoid factor (RF).[40] Furthermore, the SDAI and CDAI do not need complicated calculations and their formulas are easy to remember.

Recommendation 5: The number of affected joints, ESR, CRP, RF, ACPA, and other indicators should take into consideration when selecting treatment regimens (1B). Meanwhile, extra-articular lesions should also be considered. Common complications, including cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, and malignancy should be monitored as well (1B).

Evaluation of poor prognostic factors is crucial to RA management, and evaluation can provide important clues to clinicians to adjust treatment plans and select appropriate medications. Several predictive models have shown that joint pain, swollen joint counts, and elevated ESR, CRP, RF, and ACPA levels are predictive factors for joint damage.[41, 42, 43, 44] Thus, poor prognostic factors can help physicians to determine the best treatment strategy.

Data from a Chinese registry for rheumatic diseases shows that the common complications and risk factors are cardiovascular diseases (2.2%), fragile fractures (1.7%), and malignancy (0.6%). Aging and long-term disease have a positive relationship with these complications.[13] Furthermore, these complications have been found to influence prognosis and increase mortality rate.[45, 46] RA patients will also experience extra-articular organ involvement. Studies have shown that the incidence of extra-articular manifestation is between 17.8% and 47.5%, and the affected tissues and organs include skin, lungs, heart, nervous system, eyes, blood, and kidneys. Patients with complications have higher mortality rate when compared with patients with no complications.[47, 48] Therefore, clinicians should evaluate every patient's condition comprehensively to develop the most appropriate treatment regimen and adjust the treatment plans accordingly.

Recommendation 6: Once RA is diagnosed, conventional synthetic DMARDs treatment should be initiated as early as possible. We recommend methotrexate (MTX) monotherapy as the first-line therapy (1A). In patients who are contraindicated to MTX, leflunomide or sulfasalazine monotherapy should be considered (1B).

Conventional synthetic DMARDs are the cornerstone of RA treatment and are recommended as the first-line therapy by domestic and international guidelines.[16, 17, 18, 19] A cohort study showed that the higher cumulative doses of conventional synthetic DMARDs in RA patients within the first year of diagnosis the later the time for joint replacement. The risk for surgical procedure was reduced by 2–3% if treatment was initiated 1 month earlier.[49] MTX is the “anchor drug” for RA treatment.[50] In general, two-thirds of patients with RA can achieve treatment goals using MTX alone or in combination with other conventional synthetic DMARDs.[21, 50] In terms of safety, studies based on the Chinese population revealed that adverse reactions from small doses of MTX (≤ 10 mg/week) are typically mild and have better long-term tolerability. In addition, a systematic review showed that folic acid supplementation during MTX therapy (at a dose of approximately 5 mg per week) can reduce the risk of adverse reactions such as gastrointestinal side effects and liver damage.[51]

Surveys conducted in 15 European countries and the United States showed that 83% patients were treated with MTX in average, much higher than that of other DMARDs;[21] however, only 55.9% RA patients had ever being treated with MTX[13] in China. In view of the current situation of China's health economy, the role of MTX as the core drug in RA treatment in China should be further strengthened. Studies have shown that for patients who are contraindicated to MTX, the efficacy and safety of leflunomide or sulfasalazine monotherapy are comparable to MTX.[52, 53, 54, 55] Internationally, 21% of RA patients were treated with leflunomide, which is much lower than MTX, sulfasalazine, and hydroxychloroquine usage.[21] However, in China, 45.9% of RA patients were treated with leflunomide in average, ranked to the second most commonly prescribed medications, just less than MTX,[13] and its usage rate was even higher than MTX in some regions. This phenomenon has raised concerns from the rheumatology professions in the country.[56] The safety profile of sulfasalazine in Chinese RA patients is good, but only 4.4% has ever been treated with it, which is far lower than the 43% utilization rate in foreign countries. The vast majority patients were treated with sulfasalazine combined with other conventional synthetic DMARDs.[57] Compared with MTX, sulfasalazine is more cost-effective monotherapy compatible to China's national economic conditions. The utilization rate of hydroxychloroquine in China and internationally are 30.4%[13] and 41%,[21] respectively. Cross-sectional studies showed that hydroxychloroquine was most frequently, in 95% case, prescribed in combination with other DMARDs.[58] Based on systematic reviews, hydroxychloroquine may be beneficial to the metabolism of RA patients and may reduce the occurrence of cardiovascular events; therefore, it is generally recommended in combination with other DMARDs.[59]

Recommendation 7: When a single conventional synthetic DMARD treatment can’t reach the treatment target, we recommend to combine one DAMRD with another 1 or 2 DMARDs (2B) or combine one DMARD with one of the biological DMARDs (2B), or combine one DMARD with one of the small molecule targeted synthetic DMARDs for the treatment (2B).

After being treated with MTX or leflunomide or sulfasalazine monotherapy, if the patients can’t reach the treatment target, we recommend to combine medications for treatment. Studies reported that conventional synthetic DMRDs combination therapy could improve clinical symptoms and reduce joint damage in early RA patients with high disease activity.[52, 60] In patients who did not respond well to MTX, a meta-analysis showed that the combination of 3 conventional synthetic DMARDs (MTX, sulfasalazine, and hydroxychloroquine) could control the disease activity. This regimen was no less effective than that of MTX combined with a biological DMARD or a small molecule targeted synthetic DMARD.[61]

When the conventional synthetic DMARD combination therapy still could not reach the treatment target, treating for extended time and careful monitoring of the efficacy may be considered. A multicenter randomized controlled trial revealed that in patients who were unable to reach the target by intensive conventional synthetic DMARDs for 3–6 months, treatment for an extended time was able to improve the clinical remission rate with good tolerability.[62]

For patients who do not reach the treatment target with conventional synthetic DMARDs, we recommend to combine one DMARD with a biological DMARD or a small molecule targeted synthetic DMARD.

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-a) inhibitors are the most widely used biological DMARDs in treating RA with abundant evidence. In North America, 50.7% patients were treated with biological DMARDs.[63] However, the data from the Chinese registry for rheumatic diseases showed that only 8.3% were treated with biological DMARDs in China.[13] We recommend to use biologic DMARDs in a standardized way in patients who satisfied the indications for biological DMARDs therapy. Tocilizumab is a recombinant humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody that targeted interleukin-6 (IL-6) receptors. For RA patients who have an insufficient response to conventional synthetic DMARDs, we recommend to combine conventional synthetic DMARDs with tocilizumab.[64, 65, 66, 67]

Small molecule targeted synthetic DMARDs, referred to Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors only so far, are a class of anti-rheumatic drugs with novel mechanisms of action. For patients who do not respond well to conventional synthetic DMARDs, we recommend combining JAK inhibitors (tofacitinib) with conventional synthetic DMARDs.[68, 69, 70, 71]

No precedence over each other for TNF-a inhibitors, tocilizumab and tofacitinib in the treatment of RA. If the treatment target could not be achieved with conventional synthetic DMARDs combined with one of the 3 categories of medications, treatment with 1 of the other 2 categories of drugs should be the alternatives.[17]

Iguratimod, an anti-rheumatic drug approved by China's Food and Drug Administration in 2011, is currently used mainly in China and Japan. However, its mechanism of action needs further investigation. Studies have shown that iguratimod and MTX combination therapy can improve clinical symptoms in active RA patients.[72, 73] The 2015 APLAR guidelines recommended that patients with active RA could be treated with iguratimod.[18] Tripterygium wilfordii Hook II is an herbal medicine, which has been used to treat RA since 1969 in China, but its use is limited due to insufficient data on safety and effectiveness. Studies published in the past 2 years had shown that Tripterygium wilfordii Hook II alone or in combination with MTX was effective in patients with no fertility requirements. The adverse reactions besides genital toxicity of Tripterygium wilfordii Hook II were not significantly different from those of MTX. Nevertheless, its toxicity needs to be closely monitored and evaluated.[74, 75, 76] In addition, herbal preparations such as total glucosides of paeony and sinomenine offer alternatives for RA treatment, but high-quality clinical trials are needed to further document their effectiveness and safety.[77]

Recommendation 8: For patients with moderate/high disease activity, we recommend conventional synthetic DMARDs in combination with glucocorticoid therapy to quickly control the symptoms (2B). Adverse events should be closely monitored during treatment. Monotherapy or long-term, high-dose glucocorticoid use is strongly not recommended (1A).

Glucocorticoids, first used to treat RA in 1948, has strong anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects.[78] Due to the concerns of serious side effects caused by gulcocorticoids, clinicians rarely used glucocorticoids for RA management for a long time in the past.[79, –80] However, systematic reviews showed that for patients with moderate/high disease activity, combining low-dose glucocorticoids (prednisone ≤ 10 mg/day or equivalent) with conventional synthetic DMARDs could quickly control symptoms and synergize the action of conventional synthetic DMARDs.[81, 82, 83]

Data from the China registry for rheumatic diseases had shown that 40.6% of patients with RA had ever been treated with glucocorticoid.[13] According to a cross-sectional study, misuse of glucocorticoids is very common in China: 70% of patients with RA received long-term treatment of glucocorticoid (e.g., longer than 6 months) and 11.3% of patients were treated with glucocorticoid alone. Therefore, the use of glucocorticoids in RA treatment needs to be standardized, especially in primary healthcare institutions.[84]

Recommendation 9: If the patient reached disease remission after being treated with a biological DMARD or small molecule targeted synthetic DMARD, tapering of the biological DMARD or the small molecule targeted synthetic DMARD could be considered. Close monitoring of disease activity during tapering is warranted given the potential for disease flare (2C). Clinicians may discuss with the patient about discontinuation of biological DMARDs or small molecule targeted synthetic DMARDs if the patient has been in sustained remission for more than 1 year (2C).

Based on the safety of long-term use of biological DMARDs or small molecule targeted synthetic DMARDS, as well as from the economic considerations, gradual reduction of the dosage when the treatment target has been reached is of great importance in China. A systematic review showed that biological DMARDs or small molecule targeted synthetic DMARDs can help patients to reach the treatment target within 6 months. The flare rate among those patients with reduction in doses was lower than those patients who stopped these medications completely and was comparable to those who did not reduce the dosage. As many as one-third to one-half of patients with RA showed clinical remission or low disease activity 1 year following biological DMARDs or small molecule targeted synthetic DMARDs discontinuation.[85, 86] Disease activity in patients who stopped small molecule targeted synthetic DMARD therapy was generally higher than in those who continued the treatment, while 37% of patients did not relapse within 1 year after drug discontinuation. Therefore, if a patient has been in sustained remission for over 1 year, the clinician may discuss the possibility of discontinuation of the biological DMARDs or small molecule target synthetic DMARDs with the patient based on his or her medication status and financial affordability.

Recommendation 10: Patients with RA should be advised to lifestyle modification, including smoking cessation, weight control, healthy diet, and exercise (2C).

Patient education is essential for disease management, because it helps to improve the effectiveness of RA treatment.[87, 88] Clinicians should help patients to fully understand the nature and prognosis of RA, help them to set up the confidence to receive standard treatment, and remind them to be monitored and followed-up regularly. In addition, patients should be encouraged to change their unhealthy life style. Obesity and smoking not only increase the incidence of RA,[89–90] but also worsen the disease.[91–92] Studies have shown that a balanced diet can help control the disease.[93–94] Adherence to aerobic exercise (rather than high-intensity exercise) 1–2 times per week helps to not only improve joint function and quality of life but also reduce fatigue.[95, 96, 97, 98]

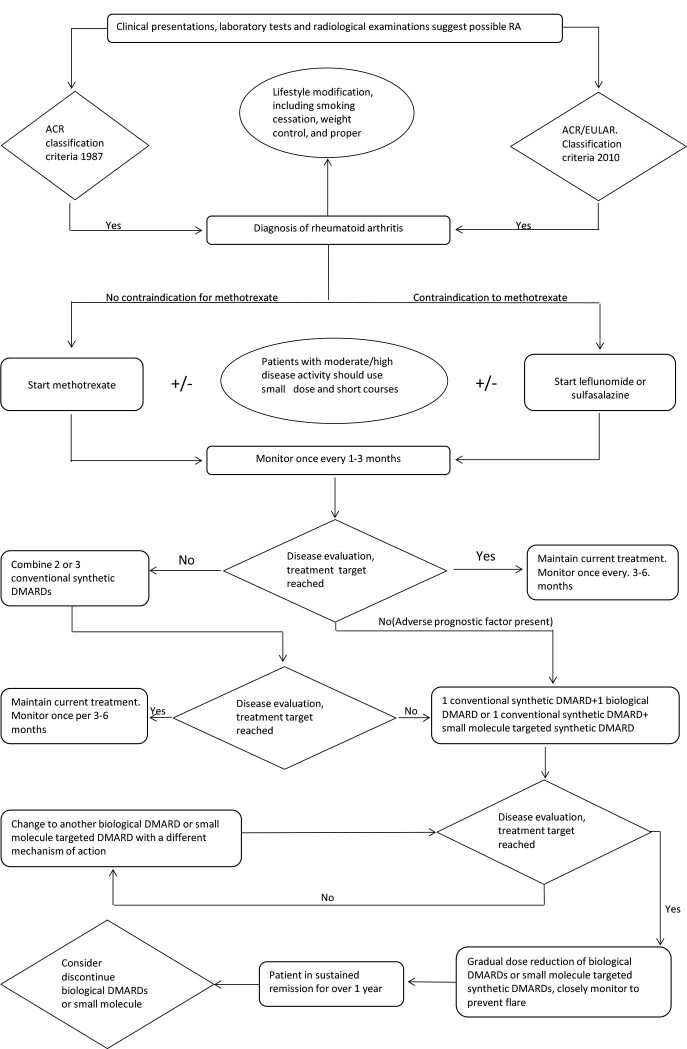

Appendix 1. Algorithm for the diagnosis and treatment of RA (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Procedure for the diagnosis and treatment of RA. Note: ACR, American Rheumatology Society; EULAR, European League Against Rheumatism; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; DMARDs, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs; RA, rheumatoid arthritis. aPatients with RA need to change lifestyle after diagnosis. bShort-term use or non-use of glucocorticoids or NSAIDs depending on patients’ symptoms and condition. cEvaluation as to whether treatment has significant effects. “No” indicates the effect is not significant, i.e., no significant improvement in RA disease activity within 3 months or cannot reach treatment target within 6 months. “Yes” indicates the effect is significant, disease activity is improved within 3 months and the treatment target is reached within 6 months. dPhysicians and patients jointly make decisions on whether or not to discontinue biological DMARDs or small molecule targeted synthetic DMARDs

Appendix 2. Process of guideline development

This guideline was initiated and developed by the Chinese Rheumatology Association. Chinese Grading of recommendations, assessment, development, and evaluation (GRADE) Center, Evidence-Based Medicine Center, Lanzhou University, contributed in methodology and evidence support. The kickoff meeting of the guideline development team was held on May 13, 2017, in Zhengzhou, Henan Province, during the 22nd Annual Meeting of the Chinese Rheumatology Association. The draft was finalized on January 1, 2018. The development of the recommendations of this guideline complies with the WHO Guidelines Development Manual[99] issued by the World Health Organization in 2014 and the Basic Methods and Procedures for the Development/Revision of the “clinical practice guideline” published by the Chinese Medical Association in 2016,[100] with reference to Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II)[101] and Reporting Items for Practice Guidelines in Healthcare (RIGHT), http://www.right-statement.org [102, 103].

Registration and guideline development proposal: This guideline was registered on the International Practice Guide Registry Platform, IPGRP, http://www.guides-registry.org (registration number IPGRP-2017CN027), from which readers can contact and request a guideline proposal.

Guideline users and the target population: This guideline is intended to be used by rheumatologists, endocrinologists, orthopedic surgeons, clinical pharmacists, diagnostic imaging physicians, and professionals who may deal with RA diagnosis and management. The target population is RA patients.

Guidelines Working Group: The Guideline development group is composed of a multidisciplinary expert group, including experts in rheumatology, endocrinology, imagines, evidence-based medicine, etc. The Working Group was divided into consensus expert group and evidence evaluation group.

Conflict of Interest Statement: Members of the Guideline Working Group are required to sign the Statement of Interest form and declare that there is no interest conflict directly related to this Guideline.

Selection and identification of clinical scenario: The Guidelines Working Group selected clinical scenario by questionnaire survey. By systematically reviewing the published guidelines and systematic reviews of RA, the working group developed 40 clinical scenario and then investigated their clinical importance and practical relevance. The first round of survey collected 66 questionnaires from the rheumatologists, with a total of 68 clinical questions and 90 outcome indicators. After merging and removing duplicates, the second round of surveys was proceeded to determine the top 10 outcome indicators for the 47 clinical questions. The survey collected 196 questionnaires from 107 medical institutions in 20 provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions. Based on the findings of the survey and the discussions of the Working Group, the relevant clinical questions were selected and included into this guideline.

Evidence searching: For clinical questions and outcome indicators that were eventually included, the questions were decomposed according to population, intervention, comparison, and outcome (PICO) principles and retrieved according to the decomposed questions: (1) Medline, The Cochrane Library, Epistemonikos, Chinese Biomedical Literature Database, Wanfang Database, and CNKI Database, the majority of the included evidence were systematic evaluation, meta-analysis, and mesh meta-analysis. The searching timeframe is the time from database establishment to January 25, 2018; (2) Up-to-date, DynaMed, Medline, China Biomedical Literature Database, Wanfang Database, and CNNKI Database were retrieved. The mostly included were original studies (including randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, case-control studies, case series, epidemiological investigations, etc.). The searching timeframe is the time when these studies are available to January 25, 2018; (3) The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, National Guideline Clearinghouse, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, ACR, EULAR, APLAR, and other official websites, and Medline, CNKI database, medical network database, mainly to search the RA field of relevant guidelines; (4) Other websites, such as Google scholar, were also included.

Evidence evaluation: Assessment of the Methodological quality of Systematic Review (AMSTAR) scale was used to assess the quality of the included systematic review. ROB (Bias Risk Assessment) was used to assess the risk of bias for randomized controlled trials. QUADAS-2 (for diagnostic trials) was used to assess the quality of diagnostic studies. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS)[104] were used to evaluate the quality of methodology of the original studies and observational studies, respectively. The evaluation process was carried out independently by 2 individuals, and if there was a disagreement, discussion or consultation with a third one was the way to reach consensus. The body of evidence and recommendations were graded using the GRADE method.[105, 106, 107, 108, 109]

Recommendations: Based on a summary of the domestic and foreign evidence provided by the evidence evaluation team, taking patients’ preferences and values, the cost, and the pros and cons of interventions into consideration, the Working Group developed 10 recommendations, which were formulated on August 25, 2017. Four face-to-face consensus meetings were held in Beijing, Fuzhou, October 14, 2017, December 14, 2017, respectively, and in Beijing, February 1, 2018, to collect 299 feedbacks. All recommendations and the quality of evidence were discussed and reviewed by the Working Group.

Dissemination and implementation: After the publication of the guideline, the Chinese Rheumatology Association will work with the World Health Organization Guidelines Implementation and Knowledge Transformation Cooperation Center to disseminate and promote the guideline by the following approaches: (1) Interpretation in academic conferences; (2) Organizing guideline promotion meetings around the whole country to ensure that rheumatologists, clinicians, pharmacists, imaging diagnosticians, and professionals related to RA diagnosis and management of RA could fully understood and could implement the guidelines correctly; (3) Publication in academic journals; (4) Promotion through public media such as WeChat.

The Working Group on Updated Guidelines plans to update the Guidelines over the next 3–5 years. The update method will comply with the update process of the international guidelines.[110]

Working Group of 2018 Chinese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of RA

Jinwei Chen (Department of Rheumatology, Xiangya II Hospital, Central South University); Lan He (Department of Rheumatology, the First Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Jiaotong University); Junqiang Lei (Department of Radiology, the First Hospital, Lanzhou University); Caifeng Li (Department of Rheumatology, Beijing Children's Hospital Affiliated to Capital Medical University); Mengtao Li (Department of Rheumatology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH), Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, National Clinical Research Center for Dermatologic and Immunologic Diseases (NCRC-DID), Key Laboratory of Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology, Ministry of Education, Chinese Rheumatism Data Center (CRDC), Chinese SLE Treatment and Research Group (CSTAR), Beijing, China); Xiaomei Li (Department of Rheumatology, Anhui Provincial Hospital); Xiaoxia Li (Department of Rheumatology, Xuanwu Hospital, Capital Medical University); He Lin (Department of Rheumatology, Fujian Provincial Hospital); Jin Lin (Department of Rheumatology, the First Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine)

Shengyun Liu (Department of Rheumatology, the First Hospital affiliated to Zhengzhou University)

Yi Liu (Department of Rheumatology, Huaxi Hospital, Sichuan University); Xiaohong Luo (Department of Endocrinology, Rheumatology and Immunology, Lanzhou General Hospital of the PLA); Li Ma (Department of Rheumatology, China Japan Friendship Hospital); Haili Shen (Department of Rheumatology, the Second Hospital of Lanzhou University); Hui Song (Department of Rheumatology, Jishuitan Hospital, Beijing); Xinping Tian (Department of Rheumatology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH), Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, National Clinical Research Center for Dermatologic and Immunologic Diseases (NCRC-DID), Key Laboratory of Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology, Ministry of Education, Chinese Rheumatism Data Center (CRDC), Chinese SLE Treatment and Research Group (CSTAR), Beijing, China)

Huji Xu (Department of Rheumatology, the Second Military Medical University Changzheng Hospital); Niansheng Yang (Department of Rheumatology, the First Hospital Affiliated to Zhongshan University); Xiaofeng Zeng (Department of Rheumatology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH), Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, National Clinical Research Center for Dermatologic and Immunologic Diseases (NCRC-DID), Key Laboratory of Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology, Ministry of Education, Chinese Rheumatism Data Center (CRDC), Chinese SLE Treatment and Research Group (CSTAR), Beijing, China); Zhuoli Zhang (Department of Rheumatology, the First Hospital of Peking University); Xiangxiong Zheng (Department of Rheumatology, Union Hospital affiliated to Fujian Medical University); Yi Zheng (Department of Rheumatology, Chaoyang Hospital, affiliated with Capital Medical University, Beijing).

Leading Expert of the Guideline Working Group: Xiaofeng Zeng

Leading Expert of the Guideline development methodology: Yaolong Chen

Footnotes

Funding source

Precision Medicine Project of National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFC0907605).

Conflict of Interest

None Declared.

References

- [1].Smolen JS, Aletaha D, McInnes IB. Rheumatoid Arthritis. Lancet. 2016;388(10055):2023–2038. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].McInnes IB, Schett G. Pathogenetic Insights from the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2328–2337. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31472-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Mcinnes IB, Schett G. The Pathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(23):2205–2219. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1004965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Burmester GR, Pope JE. Novel Treatment Strategies in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2338–2348. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31491-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Dougados M, Soubrier M, Antunez A. et al. Prevalence of Comorbidities in Rheumatoid Arthritis and Evaluation of Their Monitoring: Results of an International, Cross-Sectional Study (COMORA) Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(1):62–68. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hitchon CA, Boire G, Haraoui B. et al. Self-Reported Comorbidity is Common in Early Inflammatory Arthritis and Associated with Poorer Function and Worse Arthritis Disease Outcomes: Results from the Canadian Early Arthritis Cohort. Rheumatology. 2016;55(10):1751–1762. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kitas GD, Gabriel SE. Cardiovascular Disease in Rheumatoid Arthritis: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(1):8–14. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.142133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Smitten AL, Simon TA, Hochberg MC. et al. A Meta-Analysis of the Incidence of Malignancy in Adult Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(2):R45. doi: 10.1186/ar2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ang DC, Choi H, Kroenke K. et al. Comorbid Depression is an Independent Risk Factor for Mortality in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(6):1013–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Dickens C, McGowan L, Clark-Carter D. et al. Depression in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review of the Literature with Meta-Analysis. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(1):52–60. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200201000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Xiaofeng Z, Songlin Z, Aichun T. et al. Systematic Evaluation of the Disease Burden and Quality of Life of Rheumatoid Arthritis in China. Chin J Evidence-Based Med. 2013;13(3):300–307. doi: 10.7507/1672-2531.20130052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Yunshan Z, Xiuru W, Yuan A. et al. Investigation of Disability and Functional Restriction in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis Nationwide. Chin J Rheumatol. 2013;17(8):526–532. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-7480.2013.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Jin S, Li M, Fang Y. et al. Chinese Registry of Rheumatoid Arthritis (CREDIT): II. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Major Comorbidities in Chinese Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19(1):251. doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1457-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D. et al. The Global Burden of Rheumatoid Arthritis: Estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1316–1322. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hu H, Luan L, Yang K. et al. Burden of Rheumatoid Arthritis from a Societal Perspective: A Prevalence-Based Study on Cost of Illness for Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis in China. Int J Rheum Dis. 2018;21(8):1572–1580. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13028. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1756-185X.13028/pdf . [published online ahead of print Feb 17, 2017]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SLJ. et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(1):1–26. doi: 10.1002/art.39480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Smolen JS, Landewé R, Bijlsma J. et al. EULAR Recommendations for the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis with Synthetic and Biological Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs: 2016 Update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(6):960–977. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lau CS, Chia F, Harrison A. et al. APLAR Rheumatoid Arthritis Treatment Recommendations. Int J Rheum Dis. 2015;18(7):685–713. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Chinese Rheumatology Association. Chinese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Chin J Rheumatol. 2010;14(4):265–270. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-7480.2010.04.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Chen YL, Wang C, Shang HC. et al. Clinical Practice Guideline in China. BMJ. 2018;360:j5158. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j5158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Pincus T, Gibson KA, Castrejón I. Update on Methotrexate as the Anchor Drug for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 2013;71(Suppl 1):S9–S19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Xiaofeng Z. Investigation on the Status of Rheumatology Immunology in China. Chi Med N. 2015;30(10):19. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Yu L, Yuan J, Yuan A. et al. Analysis of the Status of Treatment in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Chin J Rheumatol. 2008;12(9):637–639. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:1007-7480.2008.09.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA. et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 Revised Criteria for the Classification of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31(3):315–324. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ye H, Su Y, Li R. et al. Comparison of Three Classification Criteria of Rheumatoid Arthritis in an Inception Early Arthritis Cohort. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35(10):1–5. doi: 10.1007/s10067-016-3281-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ. et al. 2010 Rheumatoid Arthritis Classification Criteria: An American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Collaborative Initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(9):2569–2581. doi: 10.1002/art.27584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Da ML, Cruz BA, Brenol CV. et al. 2011 Consensus of the Brazilian Society of Rheumatology for Diagnosis and Early Assessment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Rev Bras Rheumatol. 2011;51(3):199–219. doi: 10.1590/S0482-50042011000300002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Colebatch AN, Edwards CJ, Østergaard M. et al. EULAR Recommendations for the Use of Imaging of the Joints in the Clinical Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(6):804–814. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-203158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gaujoux-Viala C, Gossec L, Cantagrel A. et al. Recommendations of the French Society for Rheumatology for Managing Rheumatoid Arthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2014;81(4):287–297. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Barile A, Arrigoni F, Bruno F. et al. Computed Tomography and MR Imaging in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Radiol Clin North Am. 2017;55(5):997–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hodkinson B, Van DE, Pettipher C. et al. South African Recommendations for the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis: An Algorithm for the Standard of Care in 2013. S Afr Med J. 2013;103(2):576–585. doi: 10.7196/samj.7047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Davis JM 3rd, Matteson EL. My Treatment Approach to Rheumatoid Arthritis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(7):659–673. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Anderson J, Caplan L, Yazdany J. et al. Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity Measures: American College of Rheumatology Recommendations for Use in Clinical Practice. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64(5):640–647. doi: 10.1002/acr.21649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Aletaha D, Smolen JS. Joint Damage in Rheumatoid Arthritis Progresses in Remission According to the Disease Activity Score in 28 Joints and is Driven by Residual Swollen Joints. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(12):3702–3711. doi: 10.1002/art.30634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Felson DT, Smolen JS, Wells G. et al. American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Provisional Definition of Remission in Rheumatoid Arthritis for Clinical Trials. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(3):573–586. doi: 10.1002/art.30129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zhu H, Ru L, Da Z. et al. Remission Assessment of Rheumatoid Arthritis in Daily Practice in China: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;8(42):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10067-017-3850-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Grigor C, Capell H, Stirling A. et al. Effect of A Treatment Strategy of Tight Control for Rheumatoid Arthritis (the TICORA Study): A Single-Blind Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9430):263–269. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16676-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Albrecht K, Krüger K, Wollenhaupt J. et al. German Guidelines for the Sequential Medical Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis with Traditional and Biologic Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs. Rheumatol Int. 2014;34(1):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00296-013-2848-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Luqmani R, Hennell S, Estrach C. et al. British Society for Rheumatology and British Health Professionals in Rheumatology Guideline for the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis (the First Two Years) Rheumatology. 2006;45(9):1167–1169. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel215a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].van Leeuwen MA, van Rijswijk MH. Acute Phase Proteins in the Monitoring of Inflammatory Disorders. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1994;8(3):531–552. doi: 10.1016/S0950-3579(05)80114-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Visser K, Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK. et al. A Matrix Risk Model for the Prediction of Rapid Radiographic Progression in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis Receiving Different Dynamic Treatment Strategies: Post Hoc Analyses from the BeSt Study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(7):1333–1337. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.121160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Vastesaeger N, Xu S, Aletaha D. et al. A Pilot Risk Model for the Prediction of Rapid Radiographic Progression in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Rheumatology. 2009;48(9):1114–1121. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Meyer O, Labarre C, Dougados M. et al. Anticitrullinated Protein/Peptide Antibody Assays in Early Rheumatoid Arthritis for Predicting Five Year Radiographic Damage. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(2):120–126. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.2.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Vittecoq O, Pouplin S, Krzanowska K. et al. Rheumatoid Factor is the Strongest Predictor of Radiological Progression of Rheumatoid Arthritis in a Three-Year Prospective Study in Community-Recruited Patients. Rheumatology. 2003;42(8):939–946. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, Kremers HM. et al. Survival in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Population-Based Analysis of Trends Over 40 Years. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(1):54–58. doi: 10.1002/art.10705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Lin YC, Li YH, Chang CH. et al. Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients with Hip Fracture: A Nationwide Study. Osteoporos Int. 2015;26(2):811–817. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-2968-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Prete M, Racanelli V, Digiglio L. et al. Extra-Articular Manifestations of Rheumatoid Arthritis: An Update. Autoimm Rev. 2011;11(2):123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Hochberg MC, Johnston SS, John AK. The Incidence and Prevalence of Extra-Articular and Systemic Manifestations in a Cohort of Newly-Diagnosed Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis Between 1999 and 2006. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(2):469–480. doi: 10.1185/030079908′261177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Widdifield J, Moura CS, Wang Y. et al. The Longterm Effect of Early Intensive Treatment of Seniors with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Comparison of 2 Population-Based Cohort Studies on Time to Joint Replacement Surgery. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(5):861–868. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.151156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Pincus T, Yazici Y, Sokka T. et al. Methotrexate as the “Anchor Drug” for the Treatment of Early Rheumatoid Arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2003;21(5 Suppl 31):S179–S185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Shea B, Swinden MV, Tanjong Ghogomu E. et al. Folic Acid and Folinic Acid for Reducing Side Effects in Patients Receiving Methotrexate for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;31(5):CD000951. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000951.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Osiri M, Shea B, Welch V. et al. Leflunomide for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;3:CD002047. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Su Ran, Wei Li, Chen Yanchun. et al. Meta Analysis of the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis with Fluormit and Methotrexate. Chin J Evidence-Based Med. 2011;11(9):1062–1069. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-2531.2011.09.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Gaujoux-Viala C, Smolen JS, Landewé R. et al. Current Evidence for the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis with Synthetic Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs: A Systematic Literature Review Informing the EULAR Recommendations for the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(6):1004–1009. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.127225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Smolen JS, Kalden JR, Scott DL. et al. Efficacy and Safety of Leflunomide Compared with Placebo and Sulphasalazine in Active Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Multicenter Trial. Lancet. 1999;353(9149):259–266. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)09403-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Jirong W, Yanfei C, Lei M. et al. Investigation of the Status of Diagnosis and Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. J Gansu Trad Chin Med College. 2015;6:57–60. [Google Scholar]

- [57].Tian L, Xiuru W, Yuan A. et al. The Status of Sulfasalazine used in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis in China. J Pek University (Medical Edition) 2012;44(2):188–194. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-167X.2012.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Sali Z, Xiuru W, Chun L. et al. Investigation of the Current Situation of Hydroxychloroquine used in Rheumatoid Arthritis in China. Chin J Rheumatol. 2013;17(9):585–590. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-7480.2013.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Rempenault C, Combe B, Barnetche T. et al. Metabolic and Cardiovascular Benefits of Hydroxychloroquine in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(1):98–103. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Sheng H, Fuzhang L, Jian Z. et al. The Effects of Leflunomide Combine with Methotrexate in the Treatment of Early Severe Rheumatoid Arthritis. J Pract Med. 2008;24(20):3562–3564. [Google Scholar]

- [61].Hazlewood GS, Barnabe C, Tomlinson G. et al. Methotrexate Monotherapy and Methotrexate Combination Therapy with Traditional and Biologic Disease Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs for Rheumatoid Arthritis: Abridged Cochrane Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. BMJ. 2016;353:i1777. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Ru L, Zhao JX, Yin S. et al. High Remission and Low Relapse with Prolonged Intensive DMARD Therapy in Rheumatoid Arthritis (PRINT): A Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial. Medicine. 2016;95(28):e3968. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Strand V, Greenberg JD, Griffith J. et al. Impact of Treatment with Biologic Agents on the Use of Mechanical Devices Among Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients in A Large US Patient Registry. Arthritis Care Res(Hoboken) 2016;68(7):914–921. doi: 10.1002/acr.22784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Genovese MC, Mckay JD, Nasonov EL. et al. Interleukin-6 Receptor Inhibition with Tocilizumab Reduces Disease Activity in Rheumatoid Arthritis with Inadequate Response to Disease Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs: The Tocilizumab in Combination with Traditional Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drug Therapy Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(10):2968–2980. doi: 10.1002/art.23940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Lee YH, Bae SC. Comparative Efficacy and Safety of Tocilizumab, Rituximab, Abatacept and Tofacitinib in Patients with Active Rheumatoid Arthritis that Inadequately Responds to Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitors: A Bayesian Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Int J Rheum Dis. 2016;19(11):1103–1111. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Buckley F, Finckh A, Huizinga TW. et al. Comparative Efficacy of Novel DMARDS as Monotherapy and in Combination with Methotrexate in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients with Inadequate Response to Conventional DMARDs: A Network Meta-Analysis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21(5):409–423. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2015.21.5.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Qun S, Yan Z, Chunde B. et al. Multi-Center RCT Clinical Studies on Tocilizumab Combine with DMARDs to Treat Rheumatoid Arthritis. Chin J Intern Med. 2013;52(4):323–329. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1426.2013.04.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Fleischmann R, Mysler E, Hall S. et al. Efficacy and Safety of Tofacitinib Monotherapy, Tofacitinib with Methotrexate, and Adalimumab with Methotrexate in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis (ORAL Strategy): A Phase 3b/4, Double-Blind, Head-to-Head, Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10093):457–468. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31618-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Bergrath E, Gerber RA, Gruben D. et al. Tofacitinib Versus Biologic Treatments in Moderate-to-Severe Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients who have had an Inadequate Response to Nonbiologic DMARDs: Systematic Literature Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Int J Rheumatol. 2017;2017:8417249. doi: 10.1155/2017/8417249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Vieira MC, Zwillich SH, Jansen JP. et al. Tofacitinib Versus Biologic Treatments in Patients with Active Rheumatoid Arthritis who have had an Inadequate Response to Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitors: Results from a Network Meta-Analysis. Clin Ther. 2016;38(12):2628–2641. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Fleischmann R, Kremer J, Cush J. et al. Placebo-Controlled Trial of Tofacitinib Monotherapy in Rheumatoid Arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(6):495–507. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Li J, Mao H, Liang Y. et al. Efficacy and Safety of Iguratimod for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Clin Dev Immunol. 2013;2013(7):310628. doi: 10.1155/2013/310628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Hara M, Ishiguro N, Katayama K. et al. Safety and Efficacy of Combination Therapy of Iguratimod with Methotrexate for Patients with Active Rheumatoid Arthritis with an Inadequate Response to Methotrexate: An Open-Label Extension of A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Mod Rheumatol. 2014;24(3):410–418. doi: 10.3109/14397595.2013.843756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Xu X, Li QJ, Xia S. et al. Tripterygium Glycosides for Treating Late-Onset Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Altern Ther Health Med. 2016;22(6):32–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Wang X, Zu Y, Huang L. et al. Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis with Combination of Methotrexate and Tripterygium Wilfordii: A Meta-Analysis. Life Sci. 2017;171:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Lv QW, Zhang W, Shi Q. et al. Comparison of Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F with Methotrexate in the Treatment of Active Rheumatoid Arthritis(TRIFRA): A Randomised, Controlled Clinical Trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(6):1078–1086. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Jing Q, Zhenbin L. Herbal Medicine Bring New Promise for Treating Rheumatoid Arthritis. Chin J Rheumatol. 2014;18(3):145–147. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-7480.2014.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Neeck G. Fifty Years of Experience with Cortisone Therapy in the Study and Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;966(1):28–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].van Tuyl LH, Plass AM, Lems WF. et al. Why are Dutch Rheumatologists Reluctant to use the COBRA Treatment Strategy in Early Rheumatoid Arthritis? Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(7):974–976. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.067447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Meyfroidt S, van Hulst LT, De Cock D. et al. Factors Influencing the Prescription of Intensive Combination Treatment Strategies for Early Rheumatoid Arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2014;43(4):265–272. doi: 10.3109/03009742.2013.863382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Kirwan JR, Bijlsma JW, Boers M. et al. Effects of Glucocorticoids on Radiological Progression in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;1(1):CD006356. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Gorter SL, Bijlsma JW, Cutolo M. et al. Current Evidence for the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis with Glucocorticoids: A Systematic Literature Review Informing the EULAR Recommendations for the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(6):1010–1014. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.127332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Shengyun L, Lu Y, Lei Z. et al. Short-Term Efficacy and Safety Observation of Methotrexate Combined with Small Doses Prednisone for Treating Rheumatoid Arthritis. Chin J Intern Med. 2013;52(12):1018–1022. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1426.2013.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Na L, Xiaoyuan W, Xiuru W. et al. A National Multi-Center Survey on the Status of the Application of Glucocorticoids in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Chin Med. 2016;11(8):1216–1221. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1673-4777.2016.08.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Kuijper TM, Lamerskarnebeek FB, Jacobs JW. et al. Flare Rate in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis in Low Disease Activity or Remission when Tapering or Stopping Synthetic or Biologic DMARD: A Systematic Review. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(11):2012–2022. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.141520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Galvao TF, Zimmermann IR, da Mota LM. et al. Withdrawal of Biologic Agents in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35(7):1659–1668. doi: 10.1007/s10067-016-3285-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Riemsma RP, Kirwan JR, Taal E. et al. Patient Education for Adults with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2):CD003688. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Ying Z, Dongfeng L, Feng H. Attention to the Study of Psychosomatic Medicine in Patients with Rheumatology. Chin J Intern Med. 2017;56(3):163–166. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1426.2017.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Xu B, Lin J. Characteristics and Risk Factors of Rheumatoid Arthritis in the United States: An NHANES Analysis. Peer J. 2017;5:e4035. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Sugiyama D, Nishimura K, Tamaki K. et al. Impact of Smoking as a Risk Factor for Developing Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(1):70–81. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.096487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Saag KG, Cerhan JR, Kolluri S. et al. Cigarette Smoking and Rheumatoid Arthritis Severity. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56(8):463–469. doi: 10.1136/ard.56.8.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Liu Y, Hazlewood GS, Kaplan GG. et al. Impact of Obesity on Remission and Disease Activity in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 2017;69(2):157–165. doi: 10.1002/acr.22932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Proudman SM, James MJ, Spargo LD. et al. Fish Oil in Recent Onset Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Randomised, Double-Blind Controlled Trial within Algorithm-Based Drug Use. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(1):89–95. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].He J, Wang Y, Feng M. et al. Dietary Intake and Risk of Rheumatoid Arthritis – A Cross Section Multicenter Study. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35(12):2901–2908. doi: 10.1007/s10067-016-3383-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].do Carmo CM, Almeida da Rocha B, Tanaka C. Effects of Individual and Group Exercise Programs on Pain, Balance, Mobility and Perceived Benefits in Rheumatoid Arthritis with Pain and foot deformities. J Phys Ther Sci. 2017;29(11):1893–1898. doi: 10.1589/jpts.29.1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Hurkmans E, Van der Giesen FJ, Vliet Vlieland TP. et al. Dynamic Exercise Programs (Aerobic Capacity and/or Muscle Strength Training) in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;7(4):CD006853. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006853.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Han A, Robinson V, Judd M. et al. Tai Chi for Treating Rheumatoid Arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD004849. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Cramp F, Hewlett S, Almeida C. et al. Non-Pharmacological Interventions for Fatigue in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;23(8):997–1005. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008322.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].World Health Organization. WHO Handbook for Guideline Development. 2nd ed. Vienna: World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [100].Zhuming J, Siyan Z, Xiaowei J. et al. The Basic Methods and Procedures of Developing the Clinical Guideline. Chin Med J. 2016;96(4):250–253. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491.2016.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP. et al. AGREE II: Advancing Guideline Development, Reporting and Evaluation in Health Care. CMAJ. 2010;182(18):E839–E842. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Chen Y, Yang K, Marušic A. et al. A Reporting Tool for Practice Guidelines in Health Care: The RIGHT Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(2):128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.zefq.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Chen Y, Wang X, Wang Q. et al. Improve the Reporting Quality of Guidelines by Following the Reporting Guideline. Chin J Intern Med. 2018;57(3):168–170. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1426.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Wells GA, Shea BJ, O’Connell D. et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-Analyses. The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. 2013;(3):1–4. doi: 10.2307/632432. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA. et al. GRADE Guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE Evidence Profiles and Summary of Findings Tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Chen Y, Yao L, Norris S. et al. Application of GRADE in Systematic Reviews: Necessity, Frequently-Asked Questions and Concerns. Chin J Evid Based Med. 2013;13(12):1401–1404. doi: 10.7507/1672-2531.20130240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Yao L, Chen Y, Du L. et al. Application of GRADE in Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Accuracy Tests: A Case Analysis. Chin J Evid- Based Med. 2014;14(11):1407–1412. doi: 10.7507/1672-2531.20140226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Chen Y, Yao L, Du L. et al. Rationales, Methods, Challenges and Development Tendency of Using GRADE in Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Accuracy Tests. Chin J Evid Based Med. 2014;14(11):1402–1406. doi: 10.7507/1672-2531.20140225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Yang N, Xiao S, Zhou Q. et al. An Introduction of Principles and Methods of Applying GRADE to Network Meta-analysis. Chin J Evid Based Med. 2016;16(05):598–603. doi: 10.7507/1672-2531.20160092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Vernooij RW, Alonso-Coello P, Brouwers M. et al. Reporting Items for Updated Clinical Guidelines: Checklist for the Reporting of Updated Guidelines (CheckUp) PLoS Med. 2017;14(1):e1002207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Bruynesteyn K, Landewé R, Van dLS. et al. Radiography as Primary Outcome in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Acceptable Sample Sizes for Trials with 3 Months’ follow up. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(11):1413–1418. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.014043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Ping Y, Limin R, Xiuru W. et al. Investigation and Analysis of Adverse Reactions of Methotrexate in the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis in China. Chin J Rheumatol. 2010;14(8):550–553. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-7480.2010.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Kubo S, Yamaoka K, Amano K. et al. Discontinuation of Tofacitinib after Achieving Low Disease Activity in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Multicentre, Observational Study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017;56(8):1293–1301. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA. et al. Development of AMSTAR: A Measurement Tool to Assess the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7(2):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC. et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomised Trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME. et al. QUADAS-2: A Revised Tool for the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):529–536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]