Abstract

A spore cortex-lytic enzyme of Clostridium perfringens S40 which is encoded by sleC is synthesized at an early stage of sporulation as a precursor consisting of four domains. After cleavage of an N-terminal presequence and a C-terminal prosequence during spore maturation, inactive proenzyme is converted to active enzyme by processing of an N-terminal prosequence with germination-specific protease (GSP) during germination. The present study was undertaken to characterize GSP. In the presence of 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonic acid (CHAPS), a nondenaturing detergent which was needed for the stabilization of GSP, GSP activity was extracted from germinated spores. The enzyme fraction, which was purified to 668-fold by column chromatography, contained three protein components with molecular masses of 60, 57, and 52 kDa. The protease showed optimum activity at pH 5.8 to 8.5 in the presence of 0.1% CHAPS and retained activity after heat treatment at 55°C for 40 min. GSP specifically cleaved the peptide bond between Val-149 and Val-150 of SleC to generate mature enzyme. Inactivation of GSP by phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and HgCl2 indicated that the protease is a cysteine-dependent serine protease. Several pieces of evidence demonstrated that three protein components of the enzyme fraction are processed forms of products of cspA, cspB, and cspC, which are positioned in a tandem array just upstream of the 5′ end of sleC. The amino acid sequences deduced from the nucleotide sequences of the csp genes showed significant similarity and showed a high degree of homology with those of the catalytic domain and the oxyanion binding region of subtilisin-like serine proteases. Immunochemical studies suggested that active GSP likely is localized with major cortex-lytic enzymes on the exterior of the cortex layer in the dormant spore, a location relevant to the pursuit of a cascade of cortex hydrolytic reactions.

Bacterial spore germination, defined as the irreversible loss of spore characteristics, is triggered by specific germinants and proceeds through a set of sequential steps. Spore germination is essential to allow spore outgrowth and the formation of a new vegetative cell; once triggered, it proceeds in the absence of germinants and germinant-stimulated metabolism. This fact indicates that spore germination is a process controlled by the sequential activation of a set of preexisting germination-related enzymes but not by protein synthesis (10, 26).

Among the key enzymes involved in the spore germination of Bacillus subtilis 168, Bacillus cereus IFO 13597, and Clostridium perfringens S40 are a group of cortex-lytic enzymes which degrade spore-specific cortex peptidoglycan. In the spores, at least two cortex hydrolases, spore cortex-lytic enzyme (SCLE) and cortical fragment-lytic enzyme (CFLE), are suggested to cooperatively function for cortex degradation. That is, cortex hydrolysis during germination is initiated by attack of SCLE on intact spore peptidoglycan, which likely leads to un-cross-linking of cortex peptidoglycan; this step is followed by further degradation of the polysaccharide moiety of SCLE-modified cortex peptidoglycan by CFLE (5, 6, 23, 24, 28, 29). Thus, SCLE and CFLE differ from each other in bond specificity and recognition of the morphology of the substrate. It is most likely that the in vivo activity of CFLE is regulated by its requirement for partially un-cross-linked spore cortex. On the other hand, SCLE, which acts on intact spores, needs some activation process for the expression of activity. The mechanism of activation is crucial to an understanding of bacterial spore germination.

SCLE of C. perfringens S40 is a mature form of SleC, which is synthesized at an early stage of sporulation as a precursor consisting of four domains: an N-terminal presequence (113 residues), an N-terminal prosequence (35 residues), mature enzyme (264 residues), and a C-terminal prosequence (25 residues) (24, 33, 40). During spore maturation, the N-terminal presequence and the C-terminal prosequence are sequentially processed; the resulting inactive proenzyme, with a mass of 35 kDa (termed proSCLE) and consisting of the N-terminal prosequence and a mature region which exists as a complex with the cleaved N-terminal prepeptide (termed the prepeptide-proSCLE complex) (33), is deposited on the outside of the cortex layer in the dormant spore (25). Proteolytic cleavage of the promature junction of proSCLE in the complex (the linkage between Val-149 and Val-150 of SleC) during germination generates active SCLE with a mass of 31 kDa (24, 33). The protease involved in the conversion of proSCLE to SCLE, denoted germination-specific protease (GSP), has been detected in germinated spores (40), but its enzymatic entity remains to be established.

A part of the nucleotide sequence of the gene, hereafter denoted cspC (C. perfringens serine protease C; see below), which is present just upstream of the 5′ end of sleC has been reported (24). Comparison of the partial deduced amino acid sequence of the gene product with those registered in various databases suggested that the CspC sequence is homologous to that around the active center of serine proteases from Bacillus species. Bacterial structural genes are often organized into clusters that include genes coding for proteins whose functions are related (1, 17). This information raised the possibility that the cspC gene encodes a protease involved in the activation of SleC and prompted us to analyze the cspC gene in parallel with attempts to identify GSP. In this paper, we describe the characterization of GSP and the cloning of genes which are present upstream of the 5′ end of sleC. GSP, a serine protease which specifically processes the N-terminal prosequence of proSCLE, was isolated as a fraction consisting of three species of proteins. Several pieces of evidence indicated that these proteins are products of three tandem genes, cspA, cspB, and cspC, which are positioned just upstream of the 5′ end of sleC and encode subtilisin-like proteases with a triad active center. However, whether these proteases commit to the activation process for SleC as separate proteases or as a complex is not known at present.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and chemicals.

Spores of C. perfringens S40 were used as the source of proSCLE and GSP. Chromosomal DNA was isolated from vegetative cells of the strain. The organism was cultured as described by Miyata et al. (23). Escherichia coli XL1-Blue (Stratagene Cloning Systems, La Jolla, Calif.) was used as a host for the screening library. Plasmids pUC118 and Bluescript II KS(+) (Stratagene) were used as cloning vectors. E. coli BL21(DE3) (Novagen, Inc., Madison, Wis.) and plasmid pET22b(+) (Novagen) were used as a host and as a vector, respectively, for the expression of recombinant protein. E. coli was routinely grown at 37°C in 2× YT medium (1.6% Bacto Tryptone, 1% Bacto Yeast Extract, 0.5% NaCl [pH 7.0]) with ampicillin added to 100 μg per ml for plasmid-carrying strains. Transformation was carried out according to standard protocols (13).

The protease inhibitors used were as follows: Streptomyces subtilisin inhibitor (SSI), phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and 4-amidinophenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (APMSF) from Wako Pure Chemicals (Osaka, Japan); antipain, leupeptin, and pepstatin A from Peptide Institute, Inc. (Osaka, Japan); and aprotinin, bestatin, and E-64 from Sigma-Aldrich (Tokyo, Japan). α-, β- and κ-Caseins were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Other chemicals were obtained from Wako Pure Chemicals.

Preparation of spores and decoated spores.

Spores, decoated spores, and the spore coat fraction of C. perfringens S40 were prepared by methods described previously (23, 24).

Assay of GSP activity.

GSP activity was measured indirectly via the increase in SCLE activity after incubation of the prepeptide-proSCLE complex with GSP. The complex used as a substrate for GSP was obtained as described by Okamura et al. (33). A mixture containing 5 μl of the prepeptide-proSCLE complex (0.2 mg/ml), 134 to 115 μl of 40 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.0), and 1 to 20 μl of GSP fractions in a total volume of 140 μl was incubated at 32°C for 3 min, and then 10 μl of decoated spore suspensions was added. This reaction mixture contained a large excess of substrates for both GSP and SCLE. The initial optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of the mixture in a cell with a 1-mm light path was 0.18, and the decrease in OD600 was monitored at 32°C to detect SCLE activity (20). One unit of activity was defined as a decrease in the OD600 of 0.100 per min.

Preparation of GSP.

Purification procedures were carried out at 20°C, unless noted otherwise, and GSP activity was monitored in each fractionation step as described above. Spores were germinated as described previously (23), and GSP was extracted by incubating germinated spores (4 g of packed weight) in 20 ml of 0.25 M KCl–50 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.0) containing 0.2% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonic acid (CHAPS) at 30°C for 2 h. After debris were removed by centrifugation (15,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C), the extract was heated at 52°C for 30 min to inactivate existing SCLE, and the supernatant (20 ml) was recovered by centrifugation (15,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C). The supernatant was concentrated threefold by using a UK-10 membrane filter (Advantec MFS, Inc., Tokyo, Japan), and 2 ml was applied to a Superose 12 column (2.0 by 31 cm; bead size, 20 to 40 μm; Pharmacia) which had been equilibrated with 0.1 M KCl–40 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.0) containing 0.1% CHAPS. This procedure was carried out three times. Fractions containing GSP (total, 18 ml), which eluted near the voided volume of the column, were applied to a hydroxyapatite column (3.0 by 20 cm; fast flow; Wako Pure Chemicals) which had been equilibrated with 40 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.0) containing 0.1% CHAPS. GSP did not bind to the column, while most proteins adsorbed to the column.

Fractions containing GSP (30 ml) were applied to a TSK gel DEAE-5PW high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) column (0.75 by 7.5 cm; bead size, 10 μm; Tosoh, Tokyo, Japan) preequilibrated with 40 mM potassium phosphate (pH 6.0) containing 0.1% CHAPS. Adsorbed materials were eluted with a linear gradient of 0 to 0.3 M KCl in 40 mM potassium phosphate (pH 6.0) containing 0.1% CHAPS. The flow rate was 0.5 ml/min, and fractions were collected and assayed for GSP activity. The HPLC system used consisted of a Jasco 801-SC controller, a Jasco 880-PU pump, a Jasco 875-UV detector (all from Japan Spectroscopic Co., Tokyo, Japan), and a Shimadzu C-R3A signal integrator (Shimadzu Co., Kyoto, Japan).

Effect of protease inhibitors and chemicals on GSP activity.

All assays were carried out with 40 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.0), except when we examined the effect of CaCl2 and dipicolinic acid on activity, for which 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0) was used. Purified GSP (1.2 U; 50 μl in 0.15 M KCl–40 mM potassium phosphate [pH 7.0] containing 0.2% CHAPS or 0.15 M KCl–40 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.0] containing 0.2% CHAPS) was mixed with 1.25 to 2.50 μl of protease inhibitors and chemicals of appropriate concentrations and the mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 1 h. Dimethyl sulfoxide was used to solubilize bestatin, E-64, pepstatin A, and PMSF, but the solubilizer included in the assay medium (maximum, 0.2%) had no effect on activity.

Cloning of the csp genes.

Chromosomal DNA from C. perfringens S40 was digested with EcoRI; fragments in the size range of 6.2 to 8.0 kb were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, purified with a Geneclean II kit (Bio 101, Inc., La Jolla, Calif.), and inserted into pUC118. The ligation mixture was used to transform E. coli XL1-Blue. The csp genes were cloned from this library with a sleC probe obtained as a 2.2-kb HindIII fragment from pCP22H (24). The primers used for inverse PCR were 5′-TCACAATCTGGAGCTACTCC-3′ and 5′-TGCTTGGATTCTTCAAAGAGA-3′.

Preparation of antiserum against recombinant protein r Δ1–78CspC.

To prepare a polyclonal antibody against CspC, a recombinant CspC-His fusion was purified. The plasmid used to synthesize this protein was constructed by PCR amplification of a part of the cspC gene, encoding Ser-79 to Thr-582, from pCP70E using primers containing NdeI and XhoI restriction sites. The NdeI- and XhoI-digested PCR product was ligated into the NdeI and XhoI restriction sites of vector pET22b(+) to generate plasmid pΔ1–78CspC, resulting in a sequence encoding processed CspC with a C-terminal six-histidine tag. Plasmid pΔ1– 78CspC was introduced into E. coli BL21(DE3), and production of His-fused recombinant protein rΔ1–78CspC was induced with 1 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-galactopyranoside. The resulting fusion protein obtained from an inclusion body was dissolved in 6 M urea and purified using His · Bind kits (Novagen) as recommended by the supplier. Polyclonal antibody against the purified fusion protein was raised in mice as described previously (24).

Nucleotide sequencing and analysis.

Nucleotide sequencing was performed by the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method of Sanger et al. (35) using an ABI PRISM 310 automatic sequencer and an ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). Nucleotide and amino acid sequence analyses and comparisons with DNA and protein sequences registered in databases (GenBank, EMBL, PIR, and SWISS-PROT) were performed with MacDNASIS software (Hitachi Software Engineering, Tokyo, Japan).

Other procedures.

Protein concentrations were measured according to the methods of Bradford (4) and/or Groves et al. (12) using bovine serum albumin as a standard. Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) was carried out on slab gels using a Laemmli buffer system (19) at a constant current of 20 mA. Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation were performed by use of anti-rΔ1–78CspC antiserum as described previously (24). Analysis of the N-terminal amino acid sequence was carried out with a protein sequencer (Procise cLC model 494; Applied Biosystems) according to the method of Matsudaira (22).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper will appear in the DDBJ, EMBL, and GenBank nucleotide sequence databases under accession number AB042154.

RESULTS

Purification of GSP.

GSP was extracted from germinated spores in 0.25 M KCl–50 mM KH2PO4 (pH 7.0) containing 0.2% CHAPS. The presence of CHAPS (>0.05%) was needed for the stabilization of enzyme activity. Although most anion exchangers tested retained GSP even at 1 M KCl over the pH range of 6.5 to 8.5, the enzyme could be eluted from a DEAE-5PW column with 0.15 M KCl at pH 6.0, which is an acidic pH limit used to retain enzyme activity. The addition of dithiothreitol (0.2 mM) or EDTA (1 mM) or both in the extraction and purification steps had no effect on the activity. On this basis, the purification of GSP was performed under the conditions described in Materials and Methods.

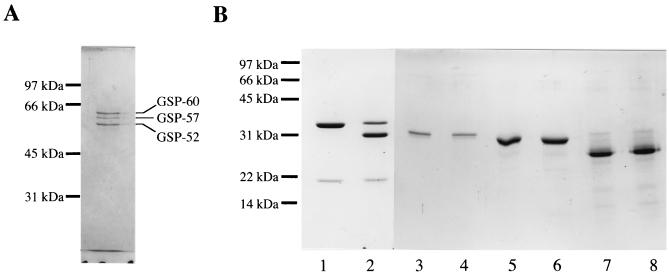

The steps in the purification procedure and the yields are shown in Table 1. A 668-fold purification was achieved, with a final yield of 10.6% enzyme activity. This final purified fraction contained three predominant proteins, termed GSP-60, GSP-57, and GSP-52; the proteins had apparent molecular masses of 60, 57, and 52 kDa, respectively, as estimated by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions (Fig. 1A). The same electrophoretic pattern was obtained under nonreducing conditions. The apparent nonstoichiometric molar ratios of GSP-60, GSP-57, and GSP-52 were 1:1:1. The N-terminal amino acid sequences of the three components were determined to be STSPIEASKVENFHNSPYLKLTGK DVIVXII (31 residues) for GSP-60, ESPVEDSKAPVFHRNP (16 residues) for GSP-57, and AYDSNRASXIPSVWNNYNLTGEGILVGFLDTGIDY (35 residues) for GSP-52 (X denotes an unidentified residue).

TABLE 1.

Purification of GSP activity from C. perfringens germinated sporesa

| Procedure | Total protein (mg) | Total activity (U) | Sp act (U/mg of protein) | Yield (%) | Purification (fold) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exudate | 69.0 | 14,394 | 208.6 | 100 | 1 |

| Superose 12 | 18.4 | 6,282 | 341.4 | 43.6 | 1.6 |

| Hydroxyapatite | 0.23 | 3,620 | 15,739.1 | 25.2 | 75.5 |

| DEAE-5PW | 0.011 | 1,533 | 139,363.6 | 10.6 | 668.1 |

C. perfringens germinated spores (4 g of packed weight) obtained as described in Materials and Methods were used as the enzyme source for this experiment.

FIG. 1.

SDS gel electrophoretic patterns of the purified active enzyme fraction (A) as well as the prepeptide-proSCLE complex and α-, β-, and κ-caseins treated or not treated with GSP (B). (A) An aliquot (1 ml) of the main peak fraction containing GSP activity which eluted from a DEAE-5PW column was dialyzed against H2O, dried by using of rotary evaporator, dissolved in 40 μl of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 1% SDS and 1% 2-mercaptoethanol, and electrophoresed on a 0.1% SDS–10% polyacrylamide gel. (B) The prepeptide-proSCLE complex (lanes 1 and 2), α-casein (lanes 3 and 4), β-casein (lanes 5 and 6), and κ-casein (lanes 7 and 8) (5 to 10 μg each) were incubated with (odd-numbered lanes) or without (even-numbered lanes) GSP (1.5 U) in 40 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.0) at 30°C for 4 h and electrophoresed on a 0.1% SDS–13.3% polyacrylamide gel. In lanes 1 and 2, 35- and 18-kDa bands are proSCLE and prepeptide, respectively. The standard proteins run were rabbit muscle phosphorylase b (97 kDa), bovine serum albumin (66 kDa), ovalbumin (45 kDa), bovine carbonic anhydrase (31 kDa), soybean trypsin inhibitor (22 kDa), and lysozyme (14 kDa).

Treatment of the prepeptide-proSCLE complex with the purified GSP fraction generated a 31-kDa polypeptide (Fig. 1B), in parallel with the appearance of spore cortex-lytic activity. Protein sequence analysis of the 31-kDa product provided an N-terminal sequence of VLPEPXVPEYIV (12 residues), which is identical to that of SCLE.

The purified GSP fraction consisting of three protein components was available in limited quantities (Table 1), which hampered further biochemical characterization of its gross conformation and compositional stoichiometry. Indeed, the amount of GSP in the spore was estimated to be about 1/100 that of the prepeptide-proSCLE complex, which is the in vivo substrate of GSP (2 mg/g of wet spore) (unpublished results).

Characteristics of GSP.

GSP was active over a pH range of 5.8 to 8.5 in the presence of 0.1% CHAPS (at least 2 months at 4°C and pH 7.0) and was stable after heat treatment at 55°C for 40 min at pH 7.0. However, the enzyme lost its activity (>80%) within 72 h at 4°C in the absence of CHAPS. Detergents such as Triton X-100, nonaethyleneglycol n-dodecyl ether, octylglucoside, and deoxycholate, which are often used to stabilize membrane proteins but dissociate aggregated proteins more effectively than CHAPS (30), were ineffective in preventing the inactivation of GSP.

GSP was inhibited 68% after incubation at 30°C for 1 h with 1 mM PMSF and 20% with 0.1 mM PMSF but not with E-64 (0.1 mM), pepstatin A (0.1 mM), bestatin (0.1 mM), and EDTA (5 mM), suggesting that GSP belongs to a family of serine proteases. However, GSP resisted a variety of known serine protease inhibitors, such as antipain (0.1 mM), APMSF (0.1 mM), leupeptin (0.1 mM), aprotinin (10 μM), and SSI (1 μM). In order to determine the substrate preference of GSP, the hydrolytic activity of GSP was investigated with α-casein, β-casein, and κ-casein as substrates. None of the proteins tested was hydrolyzed by GSP at detectable levels (Fig. 1B). These results suggest that the enzyme has a strict substrate specificity.

Both l-alanine and d-alanine (5 mM each, a germinant and a competitive inhibitor of the normal germination process, respectively) (10) had no effect on GSP-mediated hydrolysis of the prepeptide-proSCLE complex. This activity was also not affected by the addition of dipicolinic acid (5 mM) or Ca2+ (2 mM) or both, which are released from the spore core at an early stage of germination (16). The enzyme was inhibited 73 and 39% by incubation with 1 mM HgCl2 and 1 mM p-chloromercuribenzenesulfonate, respectively. The addition of dithiothreitol (10 mM, incubation at 30°C for 1 h) restored nearly 100% of the GSP activity which had been once lost with either inhibitor.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of cspA, cspB, and cspC.

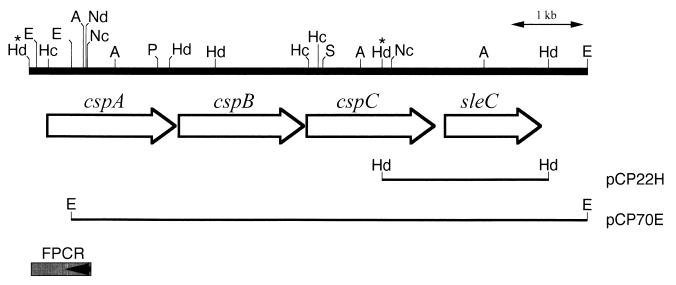

An EcoRI genomic library from C. perfringens S40 was constructed in pUC118 and transformed into E. coli XL1-Blue. This library was screened with an sleC probe, and a positive clone carrying a 6.9-kb EcoRI fragment was isolated (pCP70E in Fig. 2). A 6.4-kb EcoRI-AccI region of this fragment was sequenced, revealing the presence of four open reading frames (ORFs); 5′-truncated cspA, cspB, and cspC and 3′-truncated sleC. The sequence of the 5′ end of the cspA gene was determined by sequencing of an amplicon obtained by inverse PCR after HindIII chromosomal DNA digestion and religation. A 5,989-bp DNA sequence encompassing the complete cspA, cspB, and cspC genes was determined. Figure 3 shows the nucleotide sequence of nucleotides 1 to 4,648 and the corresponding predicted amino acid sequence. The sequence of nucleotides 4,643 to 5,989 determined in this study agreed completely with the sequence reported by Miyata et al. (24).

FIG. 2.

Physical map of a csp gene cluster of C. perfringens. The ORFs and direction of transcription are indicated by the arrows. The solid lines below the ORF arrows represent the inserts of recombinant plasmids pCP22H, from which the sleC probe was isolated, and pCP70E, from which the nucleotide sequence was derived. Restriction sites are indicated as A (AccI), E (EcoRI), Hc (HincII), Hd (HindIII), Nc (NcoI), Nd (NdeI), P (PvuII), and S (SacI). FPCR is a fragment of DNA cloned by reverse PCR. Sequence data for the HindIII-HindIII region marked by asterisks are given in Fig. 3.

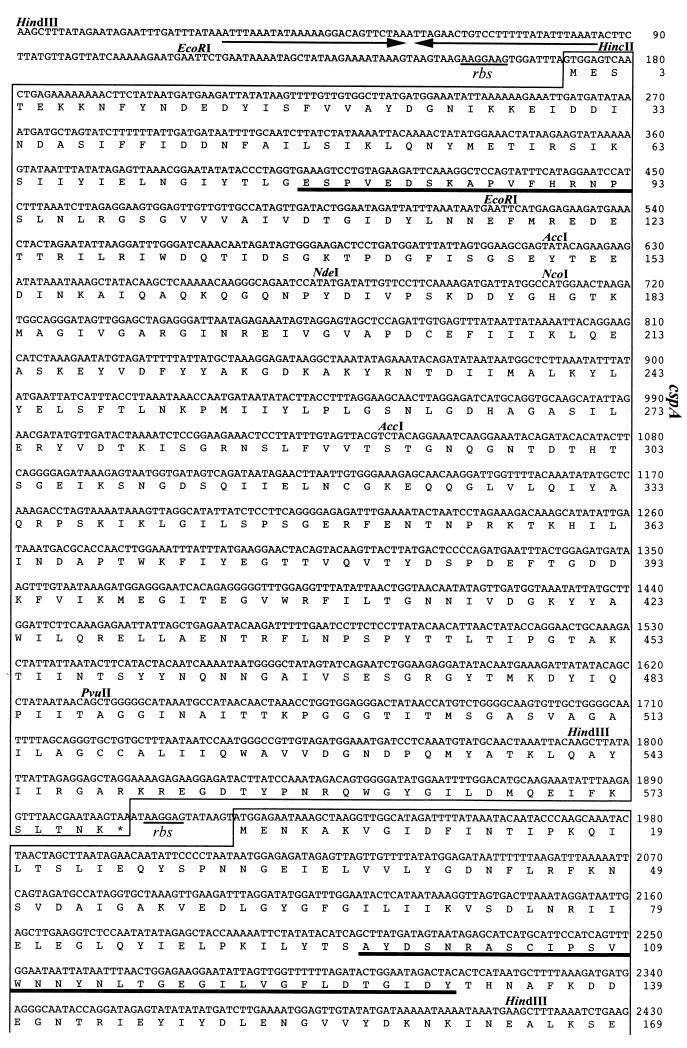

FIG. 3.

Nucleotide sequence and deduced amino acid sequence of a 4,648-bp HindIII-HindIII fragment containing cspA, cspB, and partial cspC genes. The deduced amino acid sequences of cspA (nucleotides 171 to 1,907), cspB (nucleotides 1,923 to 3,620), and part of cspC (nucleotides 3,623 to 4,648) are given below the nucleotide sequences (See reference 24 for the 3′-end sequence of cspC and the whole sequence of sleC). The numbers for the nucleotides and amino acids are shown on the right. An inverted repeat is indicated by arrows. Putative ribosome binding sites (rbs) with moderate complementarity to the 3′ end of the 16S rRNA of C. perfringens (11) are underlined. The asterisks indicate termination codons. The amino acid sequences of CspA, CspB, and CspC which agreed with the N-terminal sequences of GSP-57, GSP-52, and GSP-60, respectively, are underlined in bold.

An inverted repeat sequence (nucleotides 31 to 85) was found upstream of cspA. Possible initiation codons are nucleotides 171 to 173 (GTG) for cspA, nucleotides 1,923 to 1,925 (ATG) for cspB, and nucleotides 3,623 to 3,625 (ATG) for cspC. The stop codons for cspA, cspB, and cspC occurred at nucleotides 1,905 to 1,907 (TAA), nucleotides 3,618 to 3,620 (TAG), and nucleotides 5,369 to 5,371 (TAG), respectively. These findings suggest that cspA encodes a 578-residue protein (molecular weight, 64,427), cspB encodes a 565-residue protein (molecular weight, 62,215), and cspC encodes a 582-residue protein (molecular weight, 64,392). A potential stem-loop terminator structure for the mRNA was found downstream of the stop codon for cspC (24) but not for cspA or cspB.

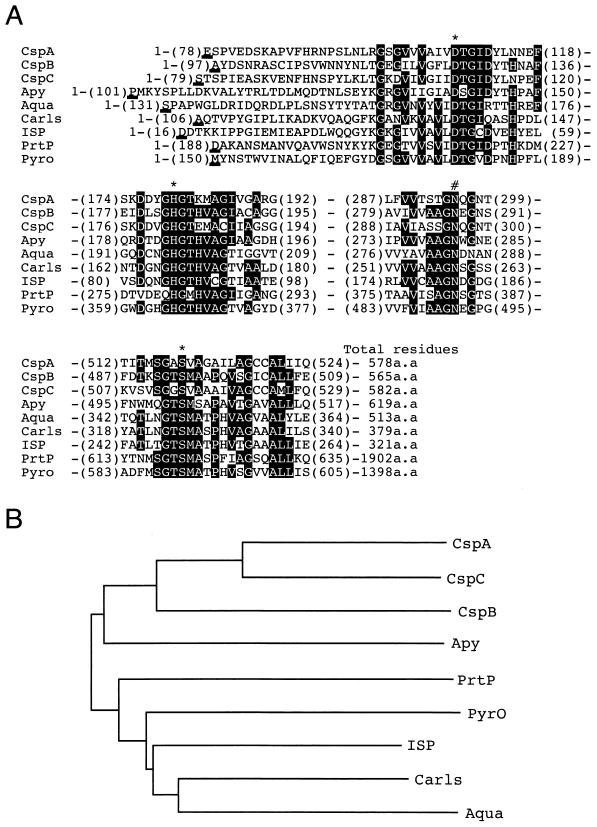

A database search revealed that the products of the csp genes belong to the superfamily of subtilisin-like serine proteases, as demonstrated by the high degree of conservation in the catalytic domain, which includes the three active-site residues (Asp, His, and Ser) and the oxyanion binding region (Asn), which stabilizes the hydrolytic reaction intermediate (Fig. 4A). Dendrogram analysis suggested that Csp proteins are closely related to each other (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Sequence alignment (A) and dendrogram analysis (B) of Csp proteins and several subtilisin-like serine proteases. (A) Only the sequences around three canonical residues (asterisks) and an oxyanion binding site (number sign) of the proteases are aligned. Identical residues in more than five proteins are indicated by black boxes. Bold underlining indicates the N terminus of mature or putative mature enzymes. Amino acid residue numbers given in parentheses indicate the first and last residues of amino acid alignments represented. The proteases are as follows: Apy, hyperthermostable protease from Aquifex pyrophilus (7); Aqua, mesothermophile alkaline protease from Thermus aquaticus YT-1 (18); Carls, subtilisin Carlsberg from Bacillus licheniformis (15); ISP, intracellular alkaline protease from Thermoactinomyces sp. strain HS682 (39); PrtP, cell envelope-located protease from Lactobacillus paracasei (14); and Pyro, hyperthermostable protease pyrolysin from Pyrococcus furiosus (41). (B) Dendrogram of Csp proteins and proteases listed above, in which branch lengths are in inverse proportion to the degree of sequence similarity. The tree was constructed using the programs ClustalX and NJPLOT (38).

GSP-57, GSP-52, and GSP-60 are processed forms of CspA, CspB, and CspC, respectively.

The 16 amino acid residues starting from Glu-78 of CspA, the 35 residues starting from Ala-97 of CspB, and the 31 residues starting from Ser-79 of CspC corresponded to the N-terminal sequences of GSP-57, GSP-52, and GSP-60, respectively. The results unequivocally indicate that GSP-52, GSP-57, and GSP-60 are processed forms of CspA, CspB, and CspC, respectively. The data suggest that the Csp proteases are produced in a form possessing propeptides, with the promature junctions in CspA, CspB, and CspC being similar to each other (Fig. 3). Thus, the predicted molecular weights of the processed GSP proteins are 51,442 for GSP-52, 55,458 for GSP-57, and 55,585 for GSP-60. Percent identities among the putative mature protease sequences are 34% between GSP-52 and GSP-57, 54% between GSP-57 and GSP-60, and 39% between GSP-52 and GSP-60.

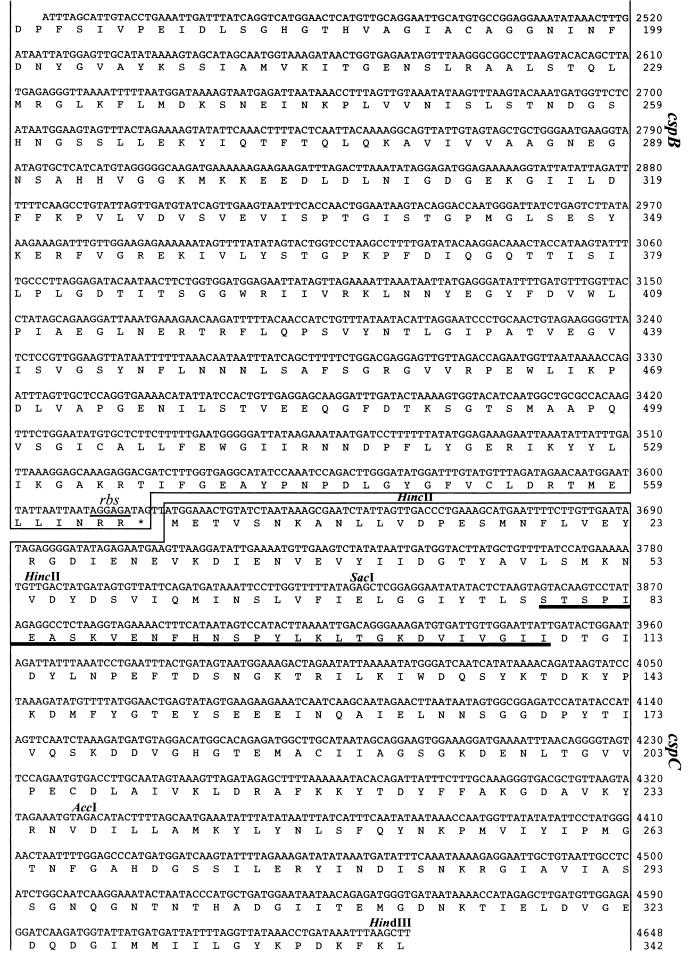

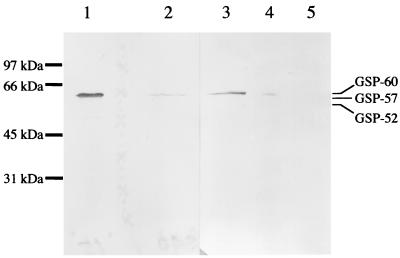

Recombinant protein rΔ1–78CspC, which was obtained in an insoluble form, did not show GSP activity. Purified rΔ1–78CspC was shown by SDS-PAGE to be almost identical in size to GSP-60, and antiserum raised against the recombinant protein recognized GSP-60 but not GSP-52 or GSP-57 (Fig. 5, lane 1). Thus, despite the high sequence similarity among GSP proteins (especially between GSP-57 and GSP-60), GSP-60 is immunologically distinct from GSP-52 and GSP-57. The anti-rΔ1–78CspC antiserum failed to immunoprecipitate GSP activity.

FIG. 5.

Immunological detection of CspC-related proteins in dormant spores. The spore coat fraction was separated from decoated spores as described in Materials and Methods. The decoated spores (1 g of wet weight) were disrupted with a bead beater in a 20-ml tube containing 10 ml H2O and 10 g of glass beads (diameter, 0.1 mm). The supernatant obtained by centrifugation (15,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C) was used as an extract of disrupted decoated spores. GSP obtained by DEAE-5PW column chromatography, the extract obtained from germinated spores by incubation in CHAPS solution, the spore coat fraction, and the extract of disrupted decoated spores were subjected to 0.1% SDS–10% PAGE followed by immunoblot analysis with anti-rΔ1–78CspC antiserum. Lanes 1, GSP obtained by DEAE-5PW column chromatography (∼5 μg of protein); 2 and 4, spore coat fraction (∼100 μg of protein for lane 2 and ∼70 μg of protein for lane 4); 3, extract from germinated spores (∼100 μg of protein); 5, extract of disrupted decoated spores (∼100 μg of protein). Samples for lanes 1 and 2 were electrophoresed on a separate gel different from that used for lanes 3 to 5. The standard proteins were the same as those used for Fig. 1.

Location of GSP-60 in dormant spores.

The coat fraction was separated from decoated spores as described previously (24). Anti-rΔ1–78CspC antiserum was used to detect GSP-60 in the spore fractions. As shown in Fig. 5, the antiserum cross-reacted only with a 60-kDa polypeptide in the extract from germinated spores incubated in CHAPS solution (lane 3) as well as purified GSP (lane 1). These findings unequivocally show that the antiserum specifically recognizes GSP-60. GSP-60 was detected in the coat fraction from dormant spores (Fig. 5, lanes 2 and 4) but not in the extract from decoated spores (lane 5), suggesting a peripheral location of GSP-60 in dormant spores. GSP activity was not detected in the coat fraction under reduced alkaline pH, nor was it regained by the addition of CHAPS after dialysis against neutral buffer.

DISCUSSION

The present results provide direct evidence demonstrating the involvement of GSP in the process of activation of SleC during the germination of C. perfringens spores. It has been confirmed that the germination protease of B. subtilis and Bacillus megaterium is involved in degrading small acid-soluble proteins during spore germination (32, 34). However, germination protease is not responsible for a germination-triggering reaction, in the sense that the enzyme hydrolyzes the so-called storage proteins of spores. Although the involvement of trypsin-like proteolytic activity in the triggering reaction has been suggested by the arrest of germination of B. cereus and B. subtilis spores in the presence of trypsin inhibitors (2, 3), several of the inhibitors used are rather hydrophobic and relatively high concentrations of the inhibitors (on the order of millimolar or more) are needed to interrupt germination. It should be noted that hydrophobic compounds such as alcohols, fatty acids, and surfactants in such concentrations are known to exert an inhibitory effect on spore germination (31, 42, 43). In this regard, the results obtained by using protease inhibitors in vivo, without consideration of possible inhibitory effects on germination due to the hydrophobic nature itself, should be viewed with some caution, since neither the relevant proteases nor their genes have been characterized. Moreover, it was reported that the inactive proform of a germination-specific cortex-lytic enzyme from spores of B. megaterium KM is processed to release the active enzyme (9), but the processing enzyme has not been identified.

GSP activity eluted from a DEAE-5PW column as a single peak which consisted of three protein components, GSP-52, GSP-57, and GSP-60. There was no disulfide linkage among these proteins. We have detected active GSP as a large molecular fraction, as suggested by its elution near the void volume in Superose 12 column chromatography. A comparison of the N-terminal amino acid sequences of the isolated proteins with the deduced amino acid sequences of Csp proteins unequivocally demonstrated that GSP-57, GSP-52, and GSP-60 are hydrolyzed forms of CspA, CspB, and CspC, respectively. Anti-rΔ1–78CspC antiserum recognized only GSP-60. It is known that genes for enzymes with related activities are often organized into clusters in bacteria; indeed, tandem cspA, cspB, and cspC genes were aligned just upstream of the 5′ end of the sleC gene. The failure of immunoprecipitation of active GSP by anti-rΔ1–78CspC antiserum may imply that epitopes are masked in the multiprotein complex. The percentage of charged amino acids (Asp, Glu, Arg, and Lys) in each GSP protein is over 20%. It has been shown that salt bridges between charged amino acids are a major factor stabilizing protein structure (7). It is likely, therefore, that intermolecular electrostatic interactions contribute to the formation of the active multiprotein enzyme with a relatively high thermal stability. At present, however, whether all three of the proteins in the active enzyme fraction or only one of the proteins is involved in the process of activation of proSCLE is unknown. In addition to the functional characteristics of each GSP protein, knowledge of the gross conformation and compositional stoichiometry of the active GSP molecule obtained here is needed to understand the mechanism of GSP function.

Isolated GSP failed to digest different caseins. Furthermore, the enzyme attacked only the Val-Val linkage of the promature junction of proSCLE (residues 149 and 150 of SleC) and not neighbor Val-Val bonds (residues 155 and 156 and residues 161 and 162 of SleC), which lie within a prolyl cluster region between Pro-131 and Pro-167 that contains 10 proline residues (24). GSP is not responsible for processing of the N-terminal prepeptide and the C-terminal propeptide of SleC during sporulation (33). It appears that the processing of the extended sequences of SleC during sporulation and germination of C. perfringens spores is tightly regulated by proteases which have a rigorous substrate specificity and are specific to the time of development of the spores.

Extraction of active GSP from germinated spores was enhanced by the addition of CHAPS, a nondenaturing detergent (30). Immunochemical studies using anti-rΔ1–78CspC antiserum revealed that GSP-60 is liberated from dormant spores by treatment of the spores with 0.1 M H3BO3 (pH 10.0) containing 1% 2-mercaptoethanol. This treatment also detaches from spores proSCLE and CFLE, which have been shown to be located on the exterior of the cortex layer (25). These observations suggest the localization of GSP to a hydrophobic and peripheral region of dormant spores, such as the outer membrane, which lies underneath the spore coat. Close localization of cortex degradation-related enzymes is pertinent to the pursuit of a cascade of cortex hydrolytic reactions during germination.

The results suggested that Csp proteins belong to a family of subtilisin-like proteases, based on DNA sequence analysis. This family of proteases is characterized by an N-terminal extended prosequence which functions as the intramolecular chaperone to assist correct folding of the protease domain (8, 36). It is likely, therefore, that the N-terminal extended sequences of Csp proteins also act as intramolecular chaperones. Unlike the situation for all known Bacillus exoproteases, which are synthesized as preproenzymes carrying both a signal peptide and a propeptide (37), there is no amino acid alignment showing the characteristics of a signal peptide-like sequence in the N-terminal extensions of the Csp proteins. In the cortex-lytic enzyme of Bacillus species, SleB, which is produced in the forespore compartment of sporulating cells, a signal sequence is needed for translocation across the forespore inner membrane to deposit forespore-synthesized proteins on the exterior side of the cortex (27). Furthermore, together with our observation that CspC is synthesized at stages II to III of sporulation (unpublished results), it seems that the Csp proteins are produced in the mother cell compartment of sporulating cells. When GSP proteins are activated in the cell by processing of the prosequences and the mechanism of processing remain to be studied.

GSP proteins possess the following biochemical properties. The heat stabilization effect of added Ca2+ on protease activity, as observed for subtilisins (21), was defective in GSP. Each of the proteins that copurified with the GSP activity had four cysteine residues, one of which was conserved (Cys-519 of CspA, Cys-504 of CspB, and Cys-524 of CspC). Since GSP was inactivated by the addition of sulfhydryl reagents, at least one of the residues might be a free cysteine which is a functionally essential sulfhydryl group. The predicted pI values were 5.02 for GSP-52, 5.53 for GSP-57, and 4.85 for GSP-60. The acidic nature might account for the observed strong adsorption of the enzyme to anion exchangers.

Although not completed, the nucleotide sequences of genomic DNAs of Clostridium acetobutylicum and Clostridium difficile are now available from Genome Therapeutics Corporation (http://www.cric.com/sequence center) and The Sanger Centre (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Profect/C difficile/), respectively. Computer research using these databases suggested the presence of sleC and csp homologs in both genomes. Tandem alignment of the csp and sleC genes observed in C. perfringens S40 appears to be conserved in the C. acetobutylicum genome. The csp homolog of C. acetobutylicum (termed cspCa), encoding a putative serine protease, is found upstream of the 5′ end of the sleC homolog, and the product of cspCa has double catalytic triads. It seems that the cspCa gene product is a bifunctional protein with two subtilisin-like protease domains or, alternatively, might undergo proteolytic processing after expression to generate two proteases. The third csp gene is missing in C. acetobutylicum. Unlike the genome organization of both C. perfringens and C. acetobutylicum, the C. difficile sleC homolog is found at a distance from two csp homologs. Although these genome sequences are incomplete, it seems that SleC- and Csp-like proteins are conserved among the clostridia.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the technical assistance of Y. Tagata.

This work was supported in part by grants in aid for scientific research (10660081 and 11660085) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blattner F R, Plunkett G, Bloch C A, et al. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boschwitz H, Gofshtein-Gandman L, Halvorson H O, Keynan A, Milner Y. The possible involvement of trypsin-like enzymes in germination of spores of Bacillus cereus T and Bacillus subtilis 168. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:1145–1153. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-5-1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boschwitz H, Halvorson H O, Keynan A, Milner Y. Trypsin-like enzymes from dormant and germinated spores of Bacillus cereus T and their possible involvement in germination. J Bacteriol. 1985;164:302–309. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.1.302-309.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y, Fukuoka S, Makino S. A novel spore peptidoglycan hydrolase of Bacillus cereus: biochemical characterization and nucleotide sequence of the corresponding gene, sleL. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1499–1506. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.6.1499-1506.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y, Miyata S, Makino S, Moriyama R. Molecular characterization of a germination-specific muramidase from Clostridium perfringens S40 spores and nucleotide sequence of the corresponding gene. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3181–3187. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3181-3187.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi I-G, Bang W-G, Kim S-H, Yu Y G. Extremely thermostable serine-type protease from Aquifex pyrophilus. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:881–888. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eder J, Fersht A R. Pro-sequence-assisted protein folding. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:609–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foster S J, Johnstone K. Germination-specific cortex-lytic enzyme is activated during triggering of Bacillus megaterium KM spore germination. Mol Microbiol. 1988;2:727–733. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1988.tb00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foster S J, Johnstone K. Pulling the triggers: the mechanism of bacterial spore germination. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:137–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb02023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garnier T, Canard B, Coles S T. Cloning, mapping, and molecular characterization of the rRNA operons of Clostridium perfringens. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5431–5438. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.17.5431-5438.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Groves W E, Davis F C, Jr, Sells B H. Spectrophotometric determination of microgram quantities of protein without nucleic acid interference. Anal Biochem. 1968;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(68)90307-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Eshcerichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holck A, Naes H. Cloning, sequencing and expression of the gene encoding the cell-envelope-associated proteinase from Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei NCDO 151. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:1353–1364. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-7-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobs M, Eliasson M, Uhlen M, Flock J I. Cloning, sequencing and expression of subtilisin Carlsberg from Bacillus licheniformis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:8913–8926. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.24.8913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnstone K, Stewart G S A B, Scott I R, Ellar D J. Zinc release and the sequence of biochemical events during triggering of Bacillus megaterium spore germination. Biochem J. 1982;208:407–411. doi: 10.1042/bj2080407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kunst F, Ogasawara N, Moszer I, et al. The complete genome sequence of the Gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature. 1997;390:249–256. doi: 10.1038/36786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwon S, Terada I, Matsuzawa H, Ohta T. Nucleotide sequence of the gene for aqualysin I (a thermophilic alkaline serine protease) of Thermus aquaticus YT-1 and characterization of the deduced primary structure of the enzyme. Eur J Biochem. 1988;173:491–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb14025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Makino S, Ito N, Inoue T, Miyata S, Moriyama R. A spore-lytic enzyme released from Bacillus cereus spores during germination. Microbiology. 1994;140:1403–1410. doi: 10.1099/00221287-140-6-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Markland F C, Smith E L. Subtilisins: primary structure, chemical and physical properties. In: Boyer P D, editor. The enzymes. Vol. 3. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1971. pp. 561–608. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsudaira P. Sequence from picomole quantities of protein electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:10035–10038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyata S, Moriyama R, Sugimoto K, Makino S. Purification and partial characterization of a spore cortex-lytic enzyme of Clostridium perfringens S40 spores. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1995;59:514–515. doi: 10.1271/bbb.59.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyata S, Moriyama R, Miyahara N, Makino S. A gene (sleC) encoding a spore cortex-lytic enzyme from Clostridium perfringens S40 spores; cloning, sequence analysis and molecular characterization. Microbiology. 1995;141:2643–2650. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-10-2643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyata S, Kozuka S, Yasuda Y, Chen Y, Moriyama R, Tochikubo K, Makino S. Localization of germination-specific spore-lytic enzymes in Clostridium perfringens S40 spores detected by immunoelectron microscopy. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;152:243–247. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1097(97)00204-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moir A, Smith D A. The genetics of bacterial spore germination. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1990;44:531–553. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.44.100190.002531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moriyama R, Fukuoka H, Miyata S, Kudoh S, Hattori A, Kozuka S, Yasuda Y, Tochikubo K, Makino S. Expression of a germination-specific amidase, SleB, of bacilli in the forespore compartment of sporulating cells and its localization on the exterior side of the cortex in dormant spores. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2373–2378. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.8.2373-2378.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moriyama R, Hattori A, Miyata S, Kudoh S, Makino S. A gene (sleB) encoding a spore cortex-lytic enzyme from Bacillus subtilis and response of the enzyme to l-alanine-mediated germination. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6059–6063. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.20.6059-6063.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moriyama R, Kudoh S, Miyata S, Nonobe S, Hattori A, Makino S. A germination-specific spore cortex-lytic enzyme from Bacillus cereus spores: cloning and sequencing of the gene and molecular characterization of the enzyme. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5330–5332. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.17.5330-5332.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moriyama R, Makino S. Effect of detergent on protein structure. Action of detergents on secondary and oligomeric structures of band 3 from bovine erythrocyte membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985;832:135–141. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(85)90324-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moriyama R, Sugimoto K, Miyata S, Katsuragi T, Makino S. Antimicrobial action of sucrose esters of fatty acids on bacterial spores. J Antibact Antifung Agents. 1996;24:3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nessi C, Jedrzejas M J, Setlow P. Structure and mechanism of action of the protease that degrades small, acid-soluble spore proteins during germination of Bacillus species. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5077–5084. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.19.5077-5084.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okamura S, Urakami K, Kimata M, Aoshima T, Shimamoto S, Moriyama R, Makino S. The N-terminal prepeptide is required for the production of spore cortex-lytic enzyme from its inactive precursor during germination of Clostridium perfringens S40 spores. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:821–827. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanchez-Salas J-L, Setlow P. Proteolytic processing of the protease which initiates degradation of small, acid-soluble proteins during germination of Bacillus subtilis spores. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2568–2577. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.9.2568-2577.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shinde U, Inouye M. The structural and functional organization of intramolecular chaperones: the N-terminal propeptides which mediate protein folding. J Biochem. 1994;115:629–636. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simonen M, Palva I. Protein secretion in Bacillus species. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:109–137. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.1.109-137.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thompson J D, Gibson T J, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins D G. The ClustalX windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;24:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsuchiya K, Ikedo I, Tsuchiya T, Kimura T. Cloning and expression of an intramolecular alkaline protease gene from alkalophilic Thermoactinomyces sp. H5682. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1997;61:298–303. doi: 10.1271/bbb.61.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Urakami K, Miyata S, Moriyama R, Sugimoto K, Makino S. Germination-specific cortex-lytic enzymes from Clostridium perfringens S40 spores: time of synthesis, precursor structure and regulation of enzymatic activity. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;173:467–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Voorhorst W G B, Eggen R I L, Geerling A C M, Platteeuw C, Siezen R J, Vos W M. Isolation and characterization of the hyperthermostable serine protease, pyrolysin, and its gene from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20426–20431. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yasuda Y, Tochikubo K, Hachisuka Y, Tomida H, Ikeda K. Quantitative structure-inhibitory activity relationships of phenols and fatty acids for Bacillus subtilis spore germination. J Med Chem. 1982;25:315–320. doi: 10.1021/jm00345a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yasuda-Yasaki Y, Namiki-Kanie S, Hachisuka Y. Inhibition of Bacillus subtilis spore germination by various hydrophobic compounds: demonstration of hydrophobic character of the l-alanine receptor site. J Bacteriol. 1978;136:484–490. doi: 10.1128/jb.136.2.484-490.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]