Dear Editor,

Voltage-gated calcium (Cav) channels regulate a broad range of physiological processes, such as muscle contraction, synaptic signal transduction, and hormone secretion.1 Cav1.3 channels belong to the L-type (L for long-lasting current) Cav subfamily (LTCC) and display diverse tissue distributions in brain, ear, heart, and endocrine organs.2 Of note, Cav1.3 channels are predominantly expressed in cochlea inner hair cells, whose normal development and synaptic transmission are crucial for proper auditory function.3

Therapeutic agents targeting Cav1.3 channels hold promises for Parkinson’s disease, resistant hypertension, and hearing dysfunction.4 In addition to the widely prescribed dihydropyridine (DHP), phenylalkylamine (PAA), and benzothiazepine (BTZ) drugs, Cav1.3 channels are subject to regulation by compounds with the diphenylmethylpiperazine (DPP) core group, exemplified by cinnarizine and flunarizine (Supplementary information, Fig. S1).5 DPP analogs, with their dual activities as antihistamines and Cav channel blockers, are used to treat motion sickness, although the molecular details for their mode of actions (MOA) remain to be revealed.6

The rabbit Cav1.1 multimeric complex purified from endogenous skeletal muscle tissues has been employed as a prototype for structural analysis of LTCC antihypertensive and antiarrhythmic agents.7 Here, we present the high-resolution structures of human Cav1.3 complex, comprising the pore-forming α1 and auxiliary α2δ-1 and β3 subunits. Ligand-free and cinnarizine-bound human Cav1.3 structures were determined at 3.0 Å and 3.1 Å resolutions, respectively.

To attain heterotrimeric Cav1.3 proteins, we transfected HEK293F cells with plasmids encoding full-length α1, α2δ-1 and β3 subunits at the mass ratio of 1.5:1.2:1. After tandem purification through affinity and size exclusion chromatography, peak fractions containing all three subunits were pooled for cryo-sample preparation (Supplementary information, Fig. S2a). The Cav1.3–drug samples were prepared by incubating concentrated proteins in the presence of 250 μM cinnarizine or 150 μM cp-PYT (compound 8 in8), a pyrimidine-2,4,6-triones derivative that showed modest selective inhibition against Cav1.3.

While cinnarizine is unambiguously resolved (Fig. 1a), there is no discernible density for cp-PYT in the electron microscopy (EM) map. cp-PYT was predicted to occupy the DHP-binding site,7,9,10 which is on the interface of repeats III and IV in the pore domain (PD), known as the III–IV fenestration. As the entire PD is clearly resolved, the invisibility of cp-PYT is unlikely to result from potential flexibility. cp-PYT was shown to be a modest inhibitor of Cav1.3, with the IC50 > 50 μM.11,12 It is possible that addition of 150 μM cp-PYT did not warrant a stable drug–channel complex that survived cryo-sample preparation. We will refer to the structure of Cav1.3 treated with cp-PYT as the apo state (Supplementary information, Figs. S2–S4 and Table S1).

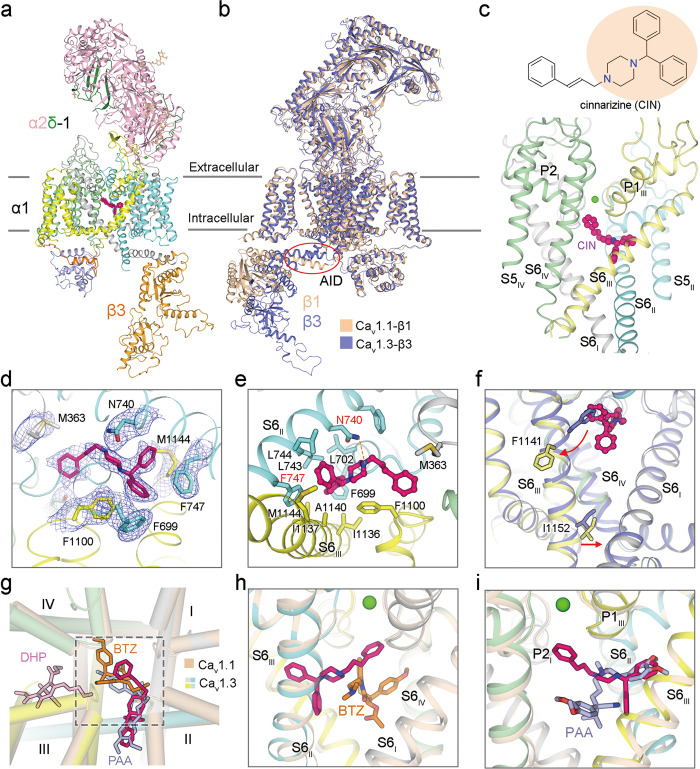

Fig. 1. Pore blockade of human Cav1.3 by cinnarizine.

a Overall structure of Cav1.3 bound to cinnarizine. The complex comprises transmembrane α1 (gray, cyan, yellow, and pale green for Repeats I–IV, respectively), extracellular α2δ-1 (light pink for α2, and green for δ), and cytosolic β3 subunits (bright orange). Cinnarizine and Ca2+ ions are shown as magenta, and green spheres. Wheat sticks indicate N-glycans on the α2δ-1 subunit. b Superimposition of rabbit Cav1.1 complex (colored wheat, PDB: 5GJV) and human Cav1.3 complex (colored purple). Despite treatment with 150 μM cp-PYT before cryo-sample preparation, there is no density for the drug in the EM map of Cav1.3. This structure will thus serve as a reference to study the conformational changes upon cinnarizine binding, as shown in panel f. Red circle highlights the minor structural shift at the AID. c Cinnarizine is accommodated in the central cavity of the PD. Chemical structure of cinnarizine is shown, with the core DPP group shaded light orange. d EM map for cinnarizine and surrounding residues. The densities, shown as blue meshes, are contoured at 4 σ in PyMol. e Molecular details for cinnarizine coordination. A potential hydrogen bond is indicated by orange dashes. f Local conformational changes upon cinnarizine binding. Red arrows indicate the structural shift of S6III upon cinnarizine binding. g The binding mode of cinnarizine is different from that of DHP drugs and other pore blockers. Shown here is an extracellular view of superimposed structures of Cav1.3 (domain-colored) bound to cinnarizine and Cav1.1 (colored wheat) bound to amlodipine (DHP drug, pink sticks, PDB: 7JPX), diltiazem (BTZ, orange sticks, PDB: 6JPB), and verapamil (PAA, light blue sticks, PDB: 6JPA). h Orthogonal binding pockets for cinnarizine and BTZ. i PAA partially overlaps with cinnarizine.

Similar to rabbit Cav1.1, the conformation of human Cav1.3 is consistent with an inactivated state, as all voltage-sensing domains (VSDs) are depolarized and the intracellular gate of the PD is closed (Supplementary information, Fig. S5). The structures of the α1 subunit in Cav1.3 and Cav1.1 can be superimposed with the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of 1.63 Å over 1017 Cα atoms (Fig. 1b; Supplementary information, Fig. S6). A minor structural difference occurs in the α1-interacting domain (AID), which is responsible for the association of β subunit to α1 and serves as a lever for β subunit to regulate the gating properties of Cav channels.13,14

Cinnarizine is accommodated in the central cavity of PD. The structure thus reveals that the motion sickness drugs are pore blockers of Cav channels (Fig. 1c, d). The entire molecule nestles right beneath the selectivity filter (SF), directly obstructing the ion-conducting pathway. Cinnarizine is coordinated through extensive contacts between its core DPP group and residues from repeats II and III. The diphenylmethane group occupies a hydrophobic pocket composed of Phe699, Leu702, Leu743, Leu744 and Phe747 in repeat II, and Ile1136, Ile1137, Ala1140 and Met1144 in repeat III. Among these residues, Phe747 on S6II appears to make the primary contribution via π–π stacking with the two phenyl rings of cinnarizine. Besides, piperazine of the core group is H-bonded to Asn740 on S6II. The cinnamyl group, which points to the SF vestibule, is sandwiched by Met363 and Phe1100, whose carbonyl oxygen groups are constituents of the inner Ca2+-binding site in the SF (Fig. 1e).

Compared to the apo state, the S6 segments in the four repeats undergo structural shifts upon cinnarizine binding (Fig. 1f; Supplementary information, Fig. S7). To accommodate cinnarizine, the helical turn of S6III containing Phe1141 undergoes both a π → α secondary structural transition and an outward motion to avoid steric clash. Interestingly, the helical turn where the gating residue Ile1152 is positioned undergoes an α → π transition, which appears to tighten the intracellular gate (Supplementary information, Fig. S8).

The binding mode of cinnarizine is distinct from those of DHP allosteric drugs and previously reported pore blockers.4 When structures of Cav1.1 in the presence of amlodipine (DHP drug), diltiazem (BTZ), and verapamil (PAA) are separately aligned with that of cinnarizine-bound Cav1.3, two major binding pockets are revealed to accommodate the diverse LTCC modulators (Fig. 1g). DHP drugs, consistent with their nature of being allosteric antagonists and agonists, occupy the III–IV fenestration, a pocket separated from that for pore blockers. Diltiazem, verapamil, and cinnarizine all directly occlude the ion-permeation pathway, but with different coordination characteristics.

The binding site for cinnarizine is orthogonal to that for diltiazem. The core benzothiazepine group of diltiazem is at a lower position compared to the cinnamyl group of cinnarizine. The methoxyphenyl group of diltiazem is supported by residues from repeats IV (Fig. 1h). In comparison, cinnarizine and verapamil partially overlap in the central cavity, interacting mainly with the hydrophobic residues on S6II and S6III (Fig. 1i). The cinnamyl group of cinnarizine directly inserts into the SF vestibule, whereas the moiety of verapamil responsible for pore blockage is positioned at the center of the pore cavity.

Taken together, DPP, BTZ and PAA compounds are all pore blockers of LTCC. To stabilize the coordination in channel pores, one end of the small molecules requires extensive hydrophobic interactions with S6 helices, S6IV for BTZ, and both S6II and S6III for PAA and DPP. The other end can be positioned at variable positions in the central cavity.

In sum, the structure of human Cav1.3 channel bound to cinnarizine unveils a direct pore blockade of LTCC by motion sickness drugs. Local structural shifts at the cinnarizine-binding site cause an axial rotation of the ensuing helical segment. The α → π transition of the gating residue-locating helical turn in S6III further constricts the ion-permeation pore. The structures shown here, along with our previous studies, reveal the molecular details for the MOA of diverse Cav channel modulators and lay the foundation for structure-aided drug discovery. Furthermore, all the reported structures of LTCC, either Cav1.1 from endogenous tissue or Cav1.3 from heterologous expression, are featured with four up VSDs and closed PD, consistent with inactivated states. In contrast, the recently reported structures of N-type Cav2.2 channels reveal a down VSDII.14,15 Establishment of a recombinant expression system for L-type Cav channels paves the avenue to investigate the intrinsic biophysical differences between different types of Cav channels.

Supplementary information

supplementary information, Figures and Table

Acknowledgements

We thank the cryo-EM facility at Princeton Imaging and Analysis Centre. This work was supported by grants from NIH (5R01GM130762, 5R01GM057440).

Author contributions

N.Y. and S.G. conceived the project. X.Y. and S.G. together conducted all wet experiments, including molecular cloning, protein purification, cryo-sample preparation, and data acquisition. S.G. performed cryo-EM data processing, model building, and refinement. All authors contributed to data analysis. N.Y. and X.Y. wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

The atomic coordinates and EM maps for cinnarizine-bound and apo Cav1.3 have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with the accession codes 7UHF (cinnarizine-bound Cav1.3) and 7UHG (apo Cav1.3) and in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank with the codes EMD-26513 (cinnarizine-bound Cav1.3) and EMD-26514 (apo Cav1.3), respectively.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Xia Yao, Shuai Gao.

Contributor Information

Xia Yao, Email: xiayao@princeton.edu.

Nieng Yan, Email: nyan@princeton.edu.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41422-022-00663-5.

References

- 1.Catterall WA. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2000;16:521–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zamponi GW, Striessnig J, Koschak A, Dolphin AC. Pharmacol. Rev. 2015;67:821–870. doi: 10.1124/pr.114.009654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brandt A, Striessnig J, Moser T. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:10832–10840. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-34-10832.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Striessnig J, Ortner NJ, Pinggera A. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 2015;8:110–122. doi: 10.2174/1874467208666150507105845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arab SF, Düwel P, Jüngling E, Westhofen M, Lückhoff A. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2004;369:570–575. doi: 10.1007/s00210-004-0936-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rascol O, Clanet M, Montastruc JL. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 1989;3:79s–87s. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.1989.tb00478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao Y, et al. Cell. 2019;177:1495–1506.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang S, et al. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:1146. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooperoper G, et al. ACS Chem. Biol. 2020;15:2539–2550. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.0c00577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao S, Yan N. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2021;60:3131–3137. doi: 10.1002/anie.202011793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang H, et al. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4481. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ortner NJ, et al. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3897. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buraei Z, Yang J. Physiol. Rev. 2010;90:1461–1506. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00057.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao S, Yao X, Yan N. Nature. 2021;596:143–147. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03699-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong Y, et al. Cell Rep. 2021;37:109931. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

supplementary information, Figures and Table

Data Availability Statement

The atomic coordinates and EM maps for cinnarizine-bound and apo Cav1.3 have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with the accession codes 7UHF (cinnarizine-bound Cav1.3) and 7UHG (apo Cav1.3) and in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank with the codes EMD-26513 (cinnarizine-bound Cav1.3) and EMD-26514 (apo Cav1.3), respectively.