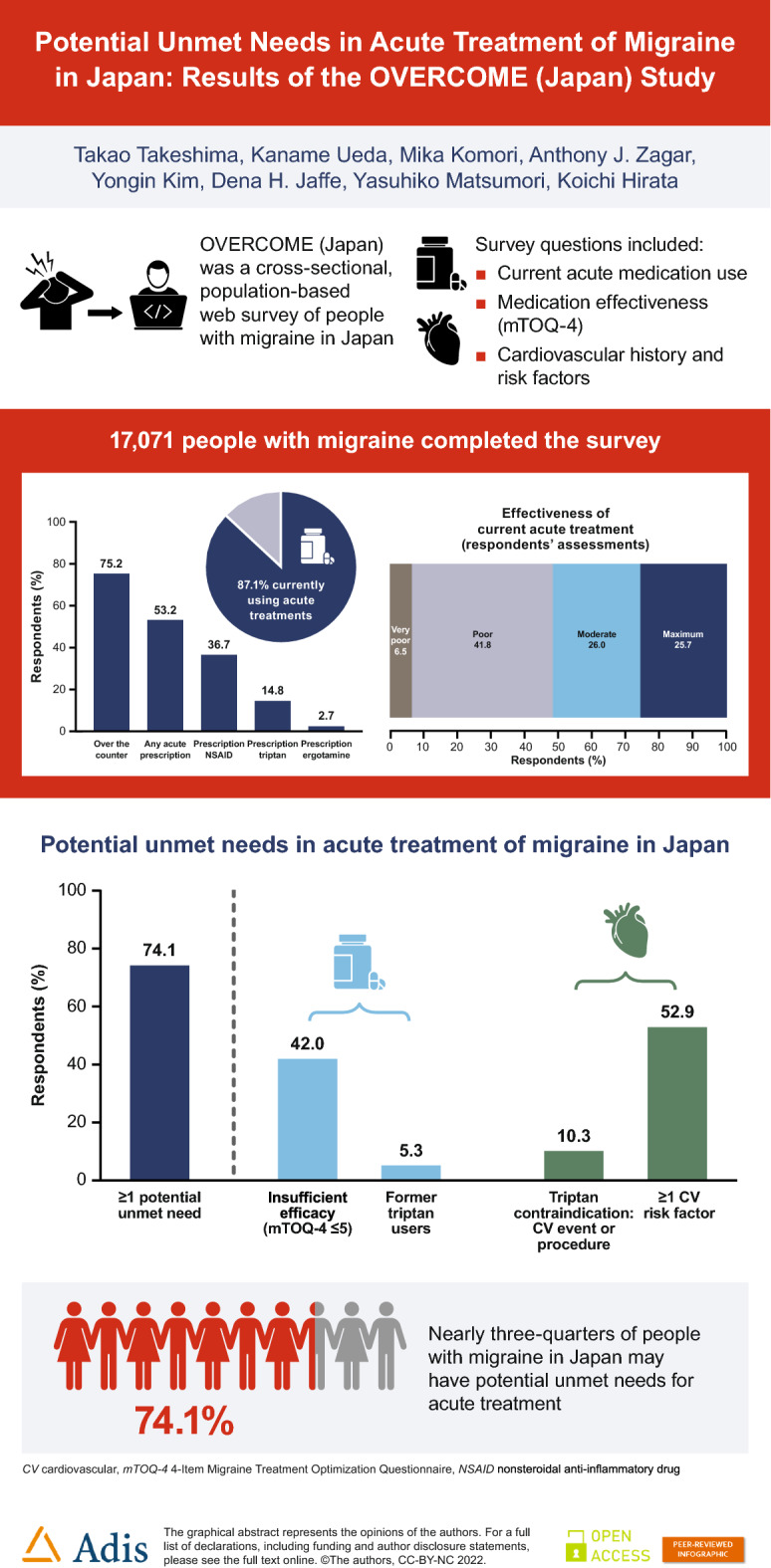

Abstract

Introduction

Using data from the ObserVational survey of the Epidemiology, tReatment, and Care Of MigrainE study in Japan (OVERCOME [Japan]), we describe the current status of the acute treatment of migraine in Japan.

Methods

OVERCOME (Japan) was a cross-sectional, observational, population-based web survey of people with migraine in Japan (met modified International Classification of Headache Disorders criteria or had a physician diagnosis of migraine) conducted between July and September 2020. Respondents reported current acute medication use and effectiveness (assessed using the Migraine Treatment Optimization Questionnaire [mTOQ-4]). Cardiovascular history and risk factors of the respondents were also recorded. Potential unmet acute treatment needs were defined as insufficient effect of current acute treatments (mTOQ-4 score ≤ 5), a history of oral triptan use (and not currently taking any triptan), potential contraindications to triptans due to cardiovascular comorbidities, and/or cardiovascular risk factors.

Results

In total, 17,071 people with migraine in Japan completed the survey; 14,869 (87.1%) of these were currently using acute treatments. Poor effectiveness of current acute treatment was reported by 7170 respondents (42.0%), 900 respondents (5.3%) were former triptan users, 1759 (10.3%) had contraindications to triptans, and 9026 (52.9%) reported at least one cardiovascular risk factor. Overall, 12,649 (74.1%) of OVERCOME (Japan) respondents were categorized into one or more of these groups and were considered to have potential unmet acute treatment needs.

Conclusion

Almost three-quarters of people with migraine in Japan may have potential unmet needs for acute treatment of migraine. There are substantial opportunities for improving care for people with migraine in Japan, including prescription of novel acute medications.

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12325-022-02289-w.

Keywords: Acute treatment, Cardiovascular risk factors, Contraindications, Drug therapy, Headache, Japan, Migraine with aura, Migraine without aura, Triptans

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Unmet needs for acute treatment of migraine in Japan, particularly for people with cardiovascular disease (CVD) or cardiovascular risk factors (CVRFs), are not currently well understood. |

| The OVERCOME (Japan) observational study assessed diagnosis, symptomatology, treatment, and impact of migraine in a representative sample of the Japanese population. |

| Survey results reported here include the types of acute medications used, patient-reported medication effectiveness, and CVD and/or CVRFs in people with migraine in Japan. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Potential unmet needs, such as insufficient effectiveness of current treatments, former triptan use, contraindications to triptans, and/or CVRFs, were reported by nearly three-quarters (74.1%) of people with migraine in Japan. |

| The impacts of these potential unmet needs may include substantial disability related to migraine and reduced options for acute treatment. |

| There are substantial opportunities for improving the care of people with migraine in Japan, including prescription of novel acute medications. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a graphical abstract, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20403363.

Introduction

Migraine is a neurological disorder characterized by severe pulsating or throbbing headaches, often accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and/or extreme sensitivity to light and sound. Migraine is one of the leading causes of years lived with disability [1]. In Japan, migraine prevalence is estimated at about 8.5% of the population [2, 3]. People with migraine in Japan can experience substantial disability and reduced productivity, which have both societal and economic impacts [3–7].

Pharmacological treatment options for migraine include both acute treatment during a migraine attack and preventive medications to reduce the frequency of migraine attacks. Acute treatments may provide pain relief or limit attack duration [8]. Over-the-counter (OTC) analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and/or migraine-specific medications may all be used as acute treatments. Up to 42% of Japanese patients with migraine may be insufficient responders to currently available acute treatments [9]. At present, triptans are the only disease-specific medications available in Japan for acute treatment of migraine. However, triptans are contraindicated in people with cardiovascular disease (CVD) and should be used with caution in those with CV risk factors (CVRFs) [10]. Patients who have contraindications to triptans or who have failed to respond to or tolerate oral triptans are considered to have unmet needs for acute treatment of migraine; such patients may be candidates for novel acute medications [11]. Unmet needs for acute treatment of migraine in Japan, particularly for people with CVD or CVRFs in the migraine population, are not currently well understood.

The ObserVational survey of the Epidemiology, tReatment, and Care Of MigrainE in Japan (OVERCOME [Japan]) was an observational study of Japanese people with migraine. The survey assessed diagnosis, symptomatology, treatment, and impact of migraine in a representative sample of Japanese people. This article describes the current status of the acute treatment of migraine using the results of OVERCOME (Japan). The objectives were to describe acute medication use, including types of medications used and patient-reported effectiveness, to identify CVD and CVRFs, and to determine potential unmet needs for acute treatment of migraine or severe headache in Japanese people with migraine.

Methods

Study Design and Study Participants

Participants in the OVERCOME (Japan) cross-sectional web survey were enrolled in the study from July to September 2020. The study was approved by the Research Institute of Healthcare Data Science Ethical Review Board (ID: RI2020003). All survey respondents provided informed consent and all data were anonymized before analysis. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Helsinki Declaration of 1964.

The study design of OVERCOME (Japan) has been previously described in detail [3]. In brief, the survey consisted of three stages: identification of a sample representative of the Japanese population in stage I, identification of people with migraine and severe headache in stage II, and assessment of migraine symptoms, impact and burden, and healthcare patterns of people with migraine in stage III. Participants were eligible for the study if they were adults, resident in Japan, had access to the internet, were able to understand Japanese, were members of the Kantar Profiles (Lightspeed) online global survey panel or its panel partners led by Cerner Enviza (formerly Kantar Health), and could provide electronic informed consent. People with migraine were identified on the basis of having at least one headache in the past 12 months that was not associated with an illness, a head injury, or a hangover and meeting the modified criteria for migraine from the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-3) criteria [12] or having a self-reported physician diagnosis of migraine. The modified criteria were previously used in the American Migraine Study [13] and the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study [14].

Measurements

Demographics and Clinical Features of Migraine

Demographic data were collected in stage I. Demographic data reported in this article include age, sex, marital status, education level, employment status, and household income. Baseline health status data include body mass index (BMI) and current smoking habit. Average headache pain severity over the previous 3 months was reported by respondents using an 11-point scale from 0 (no pain at all) to 10 (pain as bad as it could be). Allodynia symptoms were measured using the 12-item Allodynia Symptom Checklist (ASC-12) [15]. Respondents also rated their migraine-related disability during their most severe headaches, with four category options from “I work or function normally” to “bed rest required”.

Acute Treatment for Migraine

Respondents reported their current use of acute medications to treat their migraine attacks or severe headaches. Current use was defined as “currently using or typically keep on hand”. Respondents selected from a list of specific names (brand/generic) of medications for acute migraine treatment (including prescription and OTC) in the categories of triptans, ergotamine, NSAIDs, and/or simple/combination analgesics.

Respondents were also asked if they had ever used triptans as an acute migraine treatment. Those who had used triptans were asked when they typically took them. Response options were “at the first sign of an attack”, “when the pain is mild”, “when the pain is moderate or severe”, “after I’ve tried another medication”, or “don’t remember”. Respondents who selected “when the pain is moderate or severe” or “after I’ve tried another medication” were asked for their reasons for delay(s) in taking triptans. Those who reported that they no longer used triptans were asked for their reasons for stopping. Both current and former triptan users who had used two or more triptans were asked to describe how well the medications had worked. Response options were “they all worked well”, “some worked well, others worked poorly”, “they all worked poorly”, or “don't remember”. This question was separate from respondents’ assessments of their current treatment efficacy.

Respondents who were currently using acute medication completed the 4-Item Migraine Treatment Optimization Questionnaire (mTOQ-4), a validated self-report questionnaire for medication effectiveness [16]. The mTOQ-4 questions cover freedom from pain within 2 h, relief from pain for 24 h, patients’ willingness to make plans, and patients’ perceived control of their migraine or severe headaches over the previous 3 months. Response options are scored as “never” (0), “rarely” (0), “less than half the time” (1), and “half the time or more” (2) [16]. Treatment optimization categories by total mTOQ-4 score were 0 = very poor treatment effectiveness, 1–5 = poor treatment effectiveness, 6–7 = moderate treatment effectiveness, and 8 = maximum treatment effectiveness [16].

Cardiovascular History and Risk Factors

In stage III, respondents were also asked if they had any diagnosed CVD comorbidities and/or any prior cardiovascular (CV) procedures. CVDs were defined as any of the following CV events or conditions: myocardial infarction, transient ischemic attack, stroke, claudication, angina, aneurysm, cerebral hemorrhage, or deep vein thrombosis. CV procedures were any of the following: coronary angioplasty, stenting of coronary artery, coronary bypass surgery, carotid artery surgery, stenting of carotid artery, peripheral artery bypass surgery, tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) injection, or cerebral artery stent.

Patient-reported CVRFs were defined in accordance with the Japanese Comprehensive Risk Management Chart for Cerebro-Cardiovascular Disease, 2019 [17]. Respondents were identified as having CVRF(s) if they had any of the following risk factors: current smoker, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, aged ≥ 45 years (men) or ≥ 55 years (women), or postmenopausal women.

Categorizing Potential Unmet Needs for Acute Treatment

To identify respondents with potential unmet needs for acute treatment of migraine, survey respondents were placed into Groups A–D. Respondents in Group A were classified as having an insufficient effect of current acute treatments, i.e., they were currently using any acute treatment and reported a very poor/poor treatment effectiveness (mTOQ-4 score ≤ 5). Respondents in Group B had a history of oral triptan use, were not currently taking any triptan medication, and were considered to have a potential unmet need as they may be candidates for novel acute medications. Respondents in Group C had potential contraindications to triptans in the form of at least one CV event or condition and/or at least one CV procedure, as listed above. Respondents in Group D reported at least one CVRF, as defined above. Patients could be categorized into multiple groups.

Statistical Analysis

The population for analysis comprised all respondents who were identified as having migraine and who completed the migraine survey. Mean and standard deviation are reported for continuous variables. Frequencies and percentages are reported for categorical variables. Results were stratified into two monthly headache days categories: 0–3 headache days per month and ≥ 4 headache days per month. This stratification was selected because patients who experience ≥ 4 headache days per month are considered candidates for preventive medication [11]. Monthly headache days were averaged for each participant across the preceding 3 months. Potential differences between monthly headache days groups were assessed using t tests (continuous variables) or chi-square tests (categorical variables), and p < 0.05 was considered significant. SAS Enterprise Guide 7.15 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Demographics and Clinical Features of Migraine

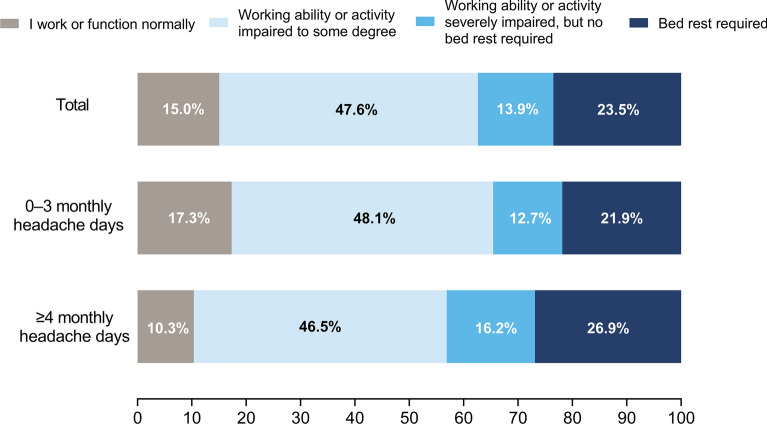

The migraine survey was completed by 17,071 respondents, most of whom were female (66.5%; Table 1). Migraine symptoms tended to be more severe in respondents with ≥ 4 monthly headache days than those with 0–3 monthly headache days. Most respondents (85.0%) experienced at least some disability during their most severe headaches (Fig. 1). Overall, 37.4% of respondents experienced severe impairment and/or required bed rest during their most severe headaches.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of survey respondents

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | Totala N = 17,071 |

Monthly headache days categoryb | p valuesc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–3 n = 11,498 |

≥ 4 n = 5573 |

|||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 40.7 (13.0) | 40.3 (13.0) | 41.7 (12.9) | < 0.001d |

| Female | 11,354 (66.5) | 7325 (63.7) | 4029 (72.3) | < 0.001e |

| At least some college education | 11,891 (69.7) | 8119 (70.6) | 3772 (67.7) | < 0.001f |

| Employment status | < 0.001f | |||

| Employed full time | 9557 (56.0) | 6614 (57.5) | 2943 (52.8) | |

| Employed part time | 2826 (16.6) | 1848 (16.1) | 978 (17.6) | |

| Household income ≥ ¥5M | 8131 (47.6) | 5573 (48.5) | 2558 (45.9) | 0.0023f |

| Current smoking habit | 3783 (22.2) | 2435 (21.2) | 1348 (24.2) | < 0.001g |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 21.86 (3.87) | 21.85 (3.76) | 21.88 (4.08) | 0.7006d |

| Pain severity score (min–max: 0–10), mean (SD) | 5.1 (2.2) | 4.8 (2.2) | 5.8 (1.9) | < 0.001d |

| ASC-12, mean (SD) | 3.4 (3.6) | 3.2 (3.6) | 3.8 (3.8) | < 0.001d |

| ASC-12 category | < 0.001f | |||

| None (0–2) | 9011 (52.8) | 6362 (55.3) | 2649 (47.5) | |

| Mild (3–5) | 4288 (25.1) | 2787 (24.2) | 1501 (26.9) | |

| Moderate (6–8) | 2113 (12.4) | 1326 (11.5) | 787 (14.1) | |

| Severe (≥ 9) | 1659 (9.7) | 1023 (8.9) | 636 (11.4) | |

Data are n (%), unless otherwise indicated

ASC-12 Allodynia Symptom Checklist, BMI body mass index, M million, max maximum, min minimum, SD standard deviation

aData in the total column previously reported [3] are age, sex, employment status, and pain severity

bData in the 0–3 monthly headache days column previously reported [4] are age, sex, total employed, pain severity, and total current use of acute treatment. Data for ≥ 4 monthly headache days as a single category have not been previously reported

cPairwise comparisons between migraine headache days categories (0–3 vs. ≥ 4); note that the large sample size may result in statistically significant differences of minimal clinical importance

dt test (continuous variable)

eChi-square test, female versus male

fChi-square test across all categories (education categories: less than high school, high school graduate, college or technical school, university graduate, post-graduate qualification, not sure, or prefer not to answer; employment categories: employed full time, employed part time, homemaker, retired, student, disability payment, not employed and looking for work, not employed and not looking for work, or prefer not to answer; household income categories: < ¥1,000,000, ¥1,000,000–¥2,999,999, ¥3,000,000–¥7,999,999, ¥8,000,000–¥9,999,999, > ¥10,000,000, or prefer not to answer)

gChi-square test, current smoker versus current non-smoker

Fig. 1.

Level of disability caused by the respondents’ most severe type of headache, stratified by monthly headache days categories. Survey participants responded to the question “Which best describes how your most severe type of headache usually affects you?”

Acute Treatment for Migraine

Among OVERCOME (Japan) respondents, 85.3% of those with 0–3 monthly headache days and 90.9% of those with ≥ 4 monthly headache days were currently using acute treatments for migraine (Table 2). OTC treatments were used by 75.2% of respondents. Most of the OTC medications used by OVERCOME respondents were analgesics such as aspirin, loxoprofen, etc. (used by 69.9% of respondents). Acetaminophen, whether OTC or prescription, was used by only 19.2% of those surveyed.

Table 2.

Acute treatment for migraine among OVERCOME (Japan) survey respondents

| Acute treatment characteristics | Totala N = 17,071 |

Monthly headache days categoryb | p valuesc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–3 n = 11,498 |

≥ 4 n = 5573 |

|||

| Current use of acute treatment (prescription and/or OTC) | 14,869 (87.1) | 9802 (85.3) | 5067 (90.9) | < 0.001d |

| OTC | 12,835 (75.2) | 8643 (75.2) | 4192 (75.2) | 0.9432d |

| Acute prescription | 9078 (53.2) | 5674 (49.4) | 3404 (61.1) | < 0.001d |

| NSAIDs | 6262 (36.7) | 3802 (33.1) | 2460 (44.1) | < 0.001d |

| Triptan | 2533 (14.8) | 1416 (12.3) | 1117 (20.0) | < 0.001d |

| Ergotamine | 466 (2.7) | 286 (2.5) | 180 (3.2) | 0.0052d |

| Current use of preventive medication | 1567 (9.2) | 854 (7.4) | 713 (12.8) | < 0.001d |

| Timing of taking triptans among current triptan userse | n = 2206 | n = 1209 | n = 997 | |

| At the first sign of an attack | 677 (30.7) | 370 (30.6) | 307 (30.8) | 0.9239d |

| When the pain is mild | 812 (36.8) | 437 (36.2) | 375 (37.6) | 0.4770d |

| When the pain is moderate or severe | 643 (29.2) | 346 (28.6) | 297 (29.8) | 0.5471d |

| After I’ve tried another medication | 130 (5.9) | 65 (5.4) | 65 (6.5) | 0.2565d |

| Don’t remember | 156 (7.1) | 98 (8.1) | 58 (5.8) | 0.0369d |

| Among those who delay taking triptans, reason(s) for delayf | n = 759 | n = 405 | n = 354 | |

| I wait to see whether the attack will go away on its own | 273 (36.0) | 143 (35.3) | 130 (36.7) | 0.6854d |

| I try to save it for really bad attacks | 250 (32.9) | 118 (29.1) | 132 (37.3) | 0.0171d |

| I may not realize that it is going to be a migraine or severe headache | 229 (30.2) | 118 (29.1) | 111 (31.4) | 0.5062d |

| Ever use triptan(s) | 3433 (20.1) | 1994 (17.3) | 1439 (25.8) | < 0.001d |

| Effectiveness of triptansg | n = 1633 | n = 921 | n = 712 | 0.0076h |

| They all worked well | 334 (20.5) | 214 (23.2) | 120 (16.9) | |

| Some worked well, others worked poorly | 1016 (62.2) | 544 (59.1) | 472 (66.3) | |

| They all worked poorly | 136 (8.3) | 81 (8.8) | 55 (7.7) | |

| Don’t remember | 147 (9.0) | 82 (8.9) | 65 (9.1) | |

Data are n (%)

NSAIDs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, OTC over the counter

aCurrent acute treatment use (any OTC, NSAIDs, triptans, and ergotamine) for the total migraine group have been previously reported [3]

bThe overall current use of acute treatment in the 0–3 monthly headache days column has been previously reported [4]. Data for ≥ 4 monthly headache days as a single category have not been previously reported

cPairwise comparisons between migraine headache days categories (0–3 vs. ≥ 4); note that the large sample size may result in statistically significant differences of minimal clinical importance

dChi-square test, “yes” versus “no”

eResponses were missing from n = 327 current triptan users

fThis question was asked if respondents took triptans when their pain was moderate or severe or after trying another medication. Top three reasons shown; additional reasons for delaying taking triptans are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Respondents could select more than one option

gThis question was asked of respondents who had ever used triptans (both current and former users) and who reported using/having used two or more triptans

hChi-square test across all categories

Overall, 53.2% of respondents were currently using acute prescription treatments (Table 2). A significantly higher percentage of respondents with ≥ 4 monthly headache days than with 0–3 headache days were using prescription NSAIDs or triptans (44.1% vs. 33.1% and 20.0% vs. 12.3%, respectively). People with ≥ 4 monthly headache days were also significantly more likely to have ever used triptan medication. Respondents with ≥ 4 monthly headache days were more likely to be currently taking preventive medication than respondents with 0–3 monthly headache days (12.8% vs 7.4%, respectively).

Among current triptan users, a substantial percentage (29.2%) typically took their triptan medication when their pain was moderate or severe; this was only slightly lower than the percentage who took their triptan at the first sign of an attack (30.7%) or when their pain was mild (36.8%; Table 2). Among those who delayed taking a triptan until the pain was moderate or severe or after trying another medication, the most common reasons for the delay were waiting to see if the attack would go away on its own (36.0%), trying to save the medication for really bad attacks (32.9%), or not realizing that the headache was a migraine/severe headache (30.2%). Additional reasons given by respondents for delaying taking triptans are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Among respondents who had previously used two or more triptans, 62.2% had experienced variation in treatment effectiveness (“some worked well, others worked poorly”; Table 2). Only 16.9% of respondents with ≥ 4 monthly headache days reported that all triptans tried had worked well, compared with 23.2% of those with 0–3 monthly headache days. Among respondents who had ever stopped using a triptan (regardless of whether they were currently taking a triptan), the most common reason given was that the medication was not working (Table S1).

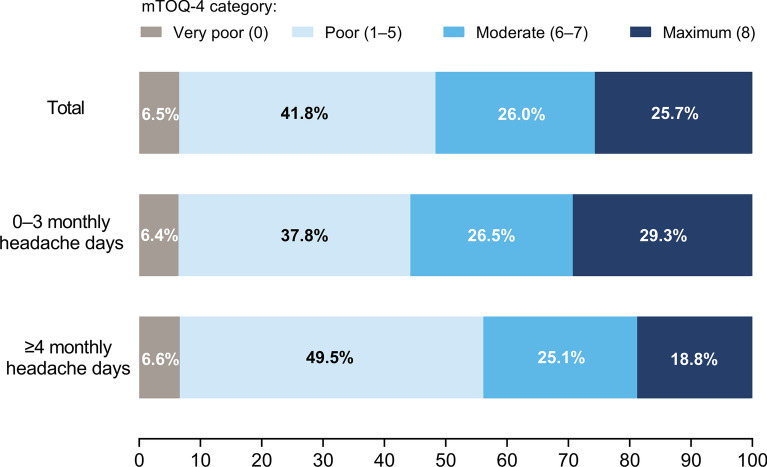

Among 14,869 respondents currently using acute medications, 962 (6.5%) reported very poor treatment effectiveness and 6208 (41.8%) reported poor treatment effectiveness (mTOQ-4 scores of 0 or 1–5, respectively) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Respondent-reported effectiveness of their current acute medication (mTOQ-4 categories). Results are shown as percentages of respondents currently using acute medication (n = 14,869). There was a significant difference between monthly headache days categories (0–3 [n = 9802] vs. ≥ 4 [n = 5067]) across all mTOQ-4 categories (chi-square test; p < 0.001). mTOQ-4 4-Item Migraine Treatment Optimization Questionnaire

Cardiovascular History and Risk Factors

Among OVERCOME (Japan) respondents, 10.0% reported having had at least one CV event and 3.0% reported having had at least one CV procedure (Table 3). The most common CV event was aneurysm (860 respondents; 5.0%). The most common CV procedure was an injection of tPA (205 respondents; 1.2%).

Table 3.

CV comorbidities, procedures, and risk factors

| Total N = 17,071 |

|

|---|---|

| Any CV event or procedure | 1759 (10.3) |

| Any CV event | 1708 (10.0) |

| Aneurysm | 860 (5.0) |

| Angina | 609 (3.6) |

| Stroke | 360 (2.1) |

| Claudication | 334 (2.0) |

| Cerebral hemorrhage | 323 (1.9) |

| Myocardial infarction | 306 (1.8) |

| DVT | 237 (1.4) |

| TIA | 218 (1.3) |

| Any CV procedure | 512 (3.0) |

| tPA injection | 205 (1.2) |

| Cerebral artery stent | 200 (1.2) |

| Coronary artery stent | 199 (1.2) |

| Carotid artery stent | 198 (1.2) |

| Carotid artery surgery | 196 (1.2) |

| Coronary angioplasty | 184 (1.1) |

| Coronary bypass surgery | 177 (1.0) |

| Peripheral artery bypass surgery | 173 (1.0) |

| CVRFs | |

| Any CVRF | 9026 (52.9) |

| Current smokers | 3783 (22.2) |

| Postmenopausal women | 2321 (20.4) |

| BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 | 2414 (16.4) |

| Hypertension | 2167 (12.7) |

| Male aged ≥ 45 years | 2006 (11.8) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1823 (10.7) |

| Female aged ≥ 55 years | 1720 (10.1) |

| Diabetes | 774 (4.5) |

Data are n (%)

BMI body mass index, CV cardiovascular, CVRF cardiovascular risk factor, DVT deep vein thrombosis, TIA transient ischemic attack, tPA tissue plasminogen activator

At least one CVRF was identified in 52.9% of OVERCOME (Japan) respondents (Table 3). The most common CVRF was smoking (22.2%). Other common risk factors included age and/or sex (postmenopausal women and men aged ≥ 45 years), BMI, and hypertension.

Potential Unmet Needs in Acute Treatment of Migraine

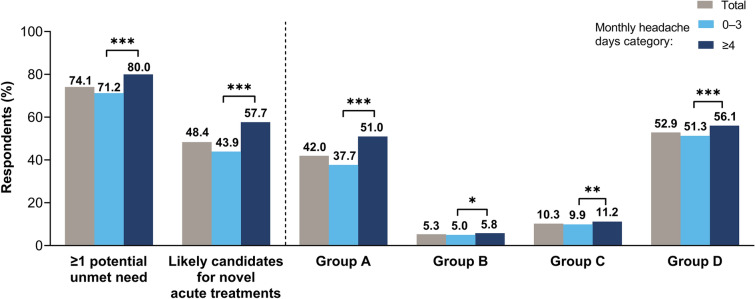

Overall, 12,649 (74.1%) OVERCOME (Japan) respondents were categorized into Group A, B, C, and/or D and were therefore considered to have potential unmet needs for acute treatment of migraine or severe headache (Fig. 3). Poor effectiveness of current acute treatment was reported by 7170 respondents (Group A; 42.0%). There were 900 former triptan users not currently using any triptan (Group B; 5.3%). There were 1759 respondents (10.3%) with contraindications to triptans (at least one CV comorbidity or procedure; Group C). At least one CVRF was reported by 9026 respondents (Group D; 52.9%). The number of respondents with poor efficacy of current medications, who were former triptan users, or who were contraindicated to triptans (i.e., the total number of respondents in Groups A, B, and/or C) was 8260 (48.4%); this group may be eligible for novel acute medications. The number of respondents who had CVRFs only and no other potential unmet needs for acute treatment (i.e., were in Group D only) was 4389 (25.7%).

Fig. 3.

Percentage of patients with potential unmet needs for acute treatment, stratified across monthly headache days categories. The patient groups were defined as Group A, insufficient effect of current acute treatments; Group B, history of oral triptan use; Group C, potential contraindications to triptans; Group D, CVRFs. Respondents could be categorized into multiple groups (see text for further details). Respondents in any of Groups A–D were considered to have ≥ 1 potential unmet need; those in Groups A, B, or C but not D were considered likely candidates for novel acute treatments. Asterisks indicate pairwise comparisons between monthly headache days categories (0–3 vs. ≥ 4): *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. CVRF cardiovascular risk factor

Discussion

OVERCOME (Japan) is the first demographically representative population-based survey of migraine in Japan to describe a broad range of characteristics, including symptom severity and disability, acute medication use, and potential unmet needs for acute treatment. Survey respondents reported substantial disability related to their most severe headaches. Most respondents used some form of acute medication treatment for migraine attacks, but almost half reported poor or very poor effectiveness of their acute medication. Around half of the respondents had at least one CVRF, which may impact on their acute treatment options. Overall, nearly three-quarters of OVERCOME (Japan) respondents had potential unmet needs for acute treatment of their migraine or severe headaches and nearly half may be candidates for novel acute medications. There are substantial opportunities for improving the care of people with migraine in Japan, including prescription of novel acute medications.

Both migraine symptoms and disability could be quite severe in OVERCOME (Japan) respondents. During their most severe headaches, 37.4% of respondents experienced severe impairment and/or required bed rest. These results are consistent with an earlier population-based survey in Japan, in which 34% of respondents rated their migraine headaches as “severe”, defined as requiring bed rest always or frequently [2]. Moderate-to-severe allodynia symptoms were experienced by 22.1% of OVERCOME (Japan) respondents, which was lower than previously reported in a US population (AMPP study, 38.1% [15]). Although the biggest impacts of migraine were seen in people with ≥ 4 monthly headache days, severe symptoms and substantial disability were also experienced by those with lower headache frequencies.

A large majority (87.1%) of OVERCOME (Japan) respondents were currently using acute medications, but nearly half of these (48.3%) reported poor or very poor effectiveness of their medication. This is a somewhat higher proportion than in the Japanese Adelphi Migraine Disease Specific Programme study, a cross-sectional survey of physicians and their consulting adult patients with migraine, in which 42.2% of patients were classified as insufficient responders to their acute medication [9]. However, in the Adelphi study, insufficient responders were defined as patients who achieved freedom from pain within 2 h of taking acute medication in three or fewer of their last five migraine attacks. The use of the validated mTOQ assessment tool in the current study allowed for more than just freedom from pain to be included in the assessment of treatment effectiveness. Insufficient acute treatment effectiveness is of concern because it has been associated with an increase in headache frequency and development of chronic migraine at 1-year follow-up [16].

Many OVERCOME (Japan) respondents (75.2%) were currently using OTC medications, consistent with the OVERCOME (US) population (81.8% using OTC medications [18]). The high percentage of respondents using OTC medications may be due in part to non-specialist physicians following a stepwise approach to migraine treatment (rather than a stratified approach), in which OTC analgesics and/or NSAIDs are trialled as treatments before proceeding to disease-specific medications. In addition, Japanese people with migraine are often subject to prescription limits (e.g., the prescription limit for triptans is typically 10 doses per month), which may result in switching to OTC medications when the prescription limit is reached. High usage of OTC medications for migraine is a concern because OTC overuse may be the most common cause of medication overuse headache in Japan [19, 20]. It appears that Japanese patients and physicians may be poorly informed about migraine and that there is a need for improved education about migraine and medication overuse headache.

In addition to insufficient effectiveness of acute treatments in general, the OVERCOME (Japan) data revealed insufficient effectiveness of triptan medications for many respondents. Only 20.5% of those who had previously used two or more triptans reported that they all worked well. Among those who had stopped using triptans, the most common reason for stopping was that they were not working. In addition, the timing of taking triptan medication was difficult for many respondents, with less than one-third (30.7%) of current triptan users taking their medication at the first sign of an attack. Many of the respondents who delayed taking their medication did so in order to determine whether the attack was truly a migraine, whether it was sufficiently severe, and/or whether it might resolve without medication. This is consistent with recent analyses of both Japanese and global Adelphi study data, in which insufficient triptan responders were significantly more likely than sufficient responders to take their medication when or after the pain had started, rather than at the first sign of a migraine attack [21, 22]. Delayed timing of taking acute medications has also been associated with insufficient response to acute treatments generally [21], so patients who have difficulty in timing their medication may benefit from novel acute treatments. Improved patient education regarding timing of medication may also benefit this patient group.

The cardiovascular history of OVERCOME (Japan) respondents revealed additional potential unmet needs for acute treatment of migraine. One-tenth (10.3%) of respondents had experienced a prior CV event and/or CV procedure. This proportion is consistent with data from the MONONOFU study, a phase 2 clinical trial of lasmiditan as an acute treatment of Japanese people with migraine, and slightly lower than the proportion observed in the AMPP study. In MONONOFU, 8.8% of participants had pre-existing CVD [23]. In the AMPP study, CV events, conditions, or procedures were reported by 13.1% of survey respondents [24]. Prescription of triptans to this subpopulation is contraindicated [10] and thus acute treatment options are restricted for this group. In addition, CVRFs were relatively common among the respondents, with 52.9% having at least one CVRF. This result is considerably lower than reported in the MONONOFU study (78.1% [23]) and the AMPP study (70.3% [25]), but consistent with an analysis of health claims data from American patients with migraine (58.5% [26]). The American population in the AMPP survey study (2009 data) had substantially higher incidences of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and obesity (all in the 30–40% range) than the health claims population (2017 data; all in the 20–30% range) and the Japanese population in the current study. The current study, with its demographically representative sampling method, is probably a better indicator of baseline CVRFs in people with migraine in Japan than the MONONOFU study, which recruited a specific subpopulation for a clinical trial. Patients with CVRFs should be prescribed triptans with caution and monitored carefully, particularly as these relatively young patients age and potentially develop CVD [10, 25].

Overall, 74.1% of OVERCOME (Japan) respondents had potential unmet needs for acute treatment of their migraine or severe headache. Furthermore, almost half (48.4%) of the OVERCOME (Japan) respondents experienced insufficient acute treatment effectiveness, were prior triptan users, and/or had a history of CV events or procedures; these people were likely candidates for novel acute treatments. For many people with migraine in Japan, improved migraine care should include acute treatment optimization, including the consideration of CV history and risk factors.

The OVERCOME (Japan) study was the first population-based epidemiological survey of people with migraine in Japan in over 20 years, and it is the largest-scale survey of migraine in Japan to date. Moreover, this was the first Japanese population-based survey to use mTOQ to assess acute treatment effectiveness. Additional strengths of the study include the use of patient-reported outcomes, the reduction of selection bias by using a demographically representative sample, and the inclusion of respondents with a large variation in headache frequency and migraine burden. Limitations of this study include recall bias owing to the use of self-reported data; potential participation bias because of a relatively low participation rate and self-selection (respondents needed internet access and opted in to both the healthcare panel and the survey [3]); and the fact that migraine diagnoses, CV events and procedures, and some CVRFs (e.g., hypertension, hyperlipidemia) were not verified by physicians. As with most survey-based studies, some data were missing owing to questions not answered (or answered incompletely) by respondents; however, this was rare and unlikely to affect the generalizability of our results.

Conclusions

The results of the OVERCOME (Japan) study have revealed that almost three-quarters of people with migraine in Japan may have potential unmet needs for acute treatment. Potential unmet needs included insufficient effectiveness of current treatments, former triptan use, contraindications to triptans, and/or CVRFs that may impact on acute treatment options. These results highlight the substantial opportunities for improving the care of people with migraine in Japan, including prescription of novel acute medications.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all study participants.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company and operated by Cerner Enviza (formerly Kantar Health). Eli Lilly and Company was involved in the study design, data analysis, and preparation of the manuscript. Cerner Enviza (formerly Kantar Health) was involved in the study design, data collection, data analysis, and preparation of the manuscript. Eli Lilly Japan K.K. and Daiichi Sankyo Company, Limited funded the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access fees.

Medical Writing Assistance

Medical writing assistance was provided by Koa Webster, PhD, and Rebecca Lew, PhD, CMPP, of ProScribe—Envision Pharma Group, and was funded by Eli Lilly Japan K.K. and Daiichi Sankyo Company, Limited. ProScribe’s services complied with international guidelines for Good Publication Practice (GPP3).

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

All authors participated in the interpretation of study results, and in the drafting, critical revision, and approval of the final version of the manuscript. Takao Takeshima, Kaname Ueda, Mika Komori, Anthony J. Zagar, Dena H. Jaffe, Yasuhiko Matsumori, and Koichi Hirata were involved in the study design. Dena H. Jaffe was an investigator in the study and was involved in data collection and statistical analysis. Yongin Kim and Anthony J. Zagar also conducted the statistical analysis.

Prior Presentation

This manuscript includes some data that were previously presented at the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Japanese Society of Neurology, Kyoto, Japan (May 19–22, 2021) and at the 49th Annual Meeting of the Japanese Headache Society, Shizuoka, Japan (November 19–21, 2021).

Disclosures

During the conduct of the study, Takao Takeshima received personal fees from AbbVie GK, Amgen Astellas BioPharma K.K., Asahi Kasei Pharma Corporation, Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd, Daiichi Sankyo Company, Limited, Eli Lilly Japan K.K., Fujifilm Toyama Chemical Co., Ltd., Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K., Kowa Company, Ltd., Kyowa Kirin Co., Ltd., Lundbeck Japan K.K., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Novartis Pharma K.K., Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Pfizer Japan Inc., Sawai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co. Ltd., and UCB Japan Co. Ltd. He also received personal fees from Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited outside the submitted work. Kaname Ueda and Mika Komori are employees of Eli Lilly Japan K.K. and own minor shares in Eli Lilly and Company. Anthony J. Zagar and Yongin Kim are employees of, and own minor shares in, Eli Lilly and Company. Dena H. Jaffe is an employee of Cerner Enviza (formerly Kantar Health); Cerner Enviza received research funding for this study from Eli Lilly and Company. Yasuhiko Matsumori received personal consultancy fees from Amgen Astellas BioPharma K.K., Daiichi Sankyo Company, Limited, Eli Lilly Japan K.K., and Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Koichi Hirata received research funding from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development and the Japanese Ministry for Health, Labour and Welfare and personal fees from Amgen Astellas BioPharma K.K., Daiichi Sankyo Company, Limited, Eisai Co., Ltd., Eli Lilly Japan K.K., MSD Co., Ltd., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Pfizer Japan Inc.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study was approved by the Research Institute of Healthcare Data Science Ethical Review Board (ID: RI2020003). All survey respondents provided informed consent and all data were anonymized before analysis. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Helsinki Declaration of 1964.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Jensen R, Uluduz D, Katsarava Z, on behalf of Lifting The Burden: the Global Campaign against Headache Migraine remains second among the world’s causes of disability, and first among young women: findings from GBD2019. J Headache Pain. 2020;21:137. doi: 10.1186/s10194-020-01208-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakai F, Igarashi H. Prevalence of migraine in Japan: a nationwide survey. Cephalalgia. 1997;17:15–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1997.1701015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirata K, Ueda K, Komori M, et al. Comprehensive population-based survey of migraine in Japan: results of the ObserVational survey of the Epidemiology, tReatment, and Care Of MigrainE (OVERCOME [Japan]) study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37:1945–1955. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2021.1971179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsumori Y, Ueda K, Komori M, et al. Burden of migraine in Japan: results of the ObserVational Survey of the Epidemiology, tReatment, and Care Of MigrainE (OVERCOME [Japan]) study. Neurol Ther. 2022;11:205–222. doi: 10.1007/s40120-021-00305-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ueda K, Ye W, Lombard L, et al. Real-world treatment patterns and patient-reported outcomes in episodic and chronic migraine in Japan: analysis of data from the Adelphi migraine disease specific programme. J Headache Pain. 2019;20:68. doi: 10.1186/s10194-019-1012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeshima T, Wan Q, Zhang Y, et al. Prevalence, burden, and clinical management of migraine in China, Japan, and South Korea: a comprehensive review of the literature. J Headache Pain. 2019;20:111. doi: 10.1186/s10194-019-1062-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimizu T, Sakai F, Miyake H, et al. Disability, quality of life, productivity impairment and employer costs of migraine in the workplace. J Headache Pain. 2021;22:29. doi: 10.1186/s10194-021-01243-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Araki N, Takeshima T, Ando N, et al. Clinical practice guideline for chronic headache 2013. Neurol Clin Neurosci. 2019;7:231–259. doi: 10.1111/ncn3.12322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirata K, Ueda K, Ye W, et al. Factors associated with insufficient response to acute treatment of migraine in Japan: analysis of real-world data from the Adelphi Migraine Disease Specific Programme. BMC Neurol. 2020;20:274. doi: 10.1186/s12883-020-01848-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bigal ME, Golden W, Buse D, Chen YT, Lipton RB. Triptan use as a function of cardiovascular risk. A population-based study. Headache. 2010;50:256–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Headache Society The American Headache Society position statement on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache. 2019;59:1–18. doi: 10.1111/head.13456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1–211. doi: 10.1177/0333102417738202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond S, Diamond ML, Reed M. Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: data from the American Migraine Study II. Headache. 2001;41:646–657. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2001.041007646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silberstein S, Loder E, Diamond S, Reed ML, Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Probable migraine in the United States: results of the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:220–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lipton R, Bigal M, Ashina S, et al. Cutaneous allodynia in the migraine population. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:148–158. doi: 10.1002/ana.21211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lipton RB, Fanning KM, Serrano D, Reed ML, Cady R, Buse DC. Ineffective acute treatment of episodic migraine is associated with new-onset chronic migraine. Neurology. 2015;84:688–695. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Japanese Council on Cerebro-Cardiovascular Disease Comprehensive risk management chart for cerebro-cardiovascular disease 2019. Nihon Naika Gakkai Zasshi. 2019;108:1024–1074. doi: 10.2169/naika.108.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lipton RB, Nicholson RA, Reed ML, et al. Diagnosis, consultation, treatment, and impact of migraine in the US: results of the OVERCOME (US) study. Headache. 2022;62:122–140. doi: 10.1111/head.14259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imai N, Kitamura E, Konishi T, Suzuki Y, Serizawa M, Okabe T. Clinical features of probable medication-overuse headache: a retrospective study in Japan. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:1020–1023. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katsuki M, Yamagishi C, Matsumori Y, et al. Questionnaire-based survey on the prevalence of medication-overuse headache in Japanese one city—Itoigawa study. Neurol Sci. 2022;43:3811–3822. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05831-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirata K, Ueda K, Komori M, et al. Unmet needs in Japanese patients who report insufficient efficacy with triptans for acute treatment of migraine: retrospective analysis of real-world data. Pain Ther. 2021;10:415–432. doi: 10.1007/s40122-020-00223-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lombard L, Farrar M, Ye W, et al. A global real-world assessment of the impact on health-related quality of life and work productivity of migraine in patients with insufficient versus good response to triptan medication. J Headache Pain. 2020;21:41. doi: 10.1186/s10194-020-01110-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hashimoto Y, Komori M, Tanji Y, Ozeki A, Hirata K. Lasmiditan for single migraine attack in Japanese patients with cardiovascular risk factors: subgroup analysis of a phase 2 randomized placebo-controlled trial. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2022 doi: 10.1080/14740338.2022.2078302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buse DC, Reed ML, Fanning KM, Kurth T, Lipton RB. Cardiovascular events, conditions, and procedures among people with episodic migraine in the US population: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study. Headache. 2017;57:31–44. doi: 10.1111/head.12962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lipton RB, Reed ML, Kurth T, Fanning KM, Buse DC. Framingham-based cardiovascular risk estimates among people with episodic migraine in the US population: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study. Headache. 2017;57:1507–1521. doi: 10.1111/head.13179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dodick DW, Shewale AS, Lipton RB, et al. Migraine patients with cardiovascular disease and contraindications: an analysis of real-world claims data. J Prim Care Community Health. 2020;11:2150132720963680. doi: 10.1177/2150132720963680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.