Abstract

Foodborne pathogens are one of the major causes of food deterioration and a public health concern worldwide. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) encrypted in protein sequences from plants, such as chia (Salvia hispanica), might have a crucial role in the inhibition of bacteria. In this study, the antibacterial activity and stability of chia peptide fractions (CPFs) were evaluated for potential applications in food preservation. Three CPFs (F < 1, F 1-3, and F 3-5 kDa) were obtained by enzymatic hydrolysis of a protein-rich fraction and subsequent ultrafiltration. Gram-positive bacteria were susceptible to F < 1. This fraction's more significant inhibition effect was reported against Listeria monocytogenes (635.4 ± 3.6 µg/mL). F < 1 remained active after incubation at 4–80 °C and a pH range of 5–8 but was inactive after exposure to pepsin and trypsin. In this sense, F < 1 could be suitable for meat and dairy products at a maximum reference level of 12–25 mg/kg. Multicriteria analysis suggested that KLKKNL could be the peptide displaying the antimicrobial activity in F < 1. These results demonstrate the potential of this sequence as a preservative for controlling the proliferation of Gram-positive bacteria in food products.

Keywords: Chia, Antimicrobial peptides, Food-borne bacteria, Food preservation

Introduction

Microbial spoilage caused by pathogenic microorganisms reduces the shelf-life of foods and increases the risk of foodborne illnesses (Krepker et al. 2017). In low-income countries, food loss is mainly attributed to microbial contamination. Improvements in food preservation are necessary to reduce food waste and limit foodborne diseases that cause hundreds of thousands of deaths annually (WHO 2015). Most food poisoning reports are associated with bacterial contamination, especially Gram-negative bacteria such as Salmonella Typhi, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Other Gram-positive bacteria, including Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, and Bacillus cereus, have also been identified as the causal agents of foodborne diseases or spoilage (Mostafa et al. 2018). Food additives are used as antimicrobial agents to extend the shelf life of foods by shielding them against deterioration caused by microorganisms. However, they have been associated with adverse side effects (Silva and Lidon 2016). Consequently, the demand for natural antimicrobial alternatives is expected to increase steadily as the negative influence exerted by some synthetic preservatives on consumers’ health has been demonstrated (Pisoschi et al. 2018). In this respect, there is an increasing interest in AMPs’ research and their application in food preservation due to their inhibitory capacity against a broad spectrum of bacteria. AMPs are a large and diverse group of molecules produced by various plant and animal species; they generally consist of 10 to 50 amino acid residues and are part of the innate immune response of organisms. Their amino acid composition, amphipathic character, cationic charge, and size allow them to interact with microbial membranes and destabilize them. AMPs exhibit a wide structural variety, their mechanism of action is mediated by disruption of bacterial membranes, which can be attributed to the cationic character of these molecules, given the presence of lysine, arginine, and histidine residues (Santos et al. 2018). Hydrophobic amino acids also confer antimicrobial activity since they improve the solubility of lipids and easily pass through the cell membrane (Dash and Ghosh 2017). Peptides with antimicrobial potential can be produced through in vitro controlled hydrolysis of food proteins such as plant proteins. The seeds of flowering plants usually accumulate large quantities of seed protein, varying from 10% (in cereals) to 40% (in some legumes and oilseeds) (Liu et al. 2017). For these reasons, seeds have been studied for the obtention of hydrolysates and peptide fractions (PFs) with biological activity.

Salvia hispanica L. is an herbaceous plant native to northern Guatemala and southern Mexico. Its protein content (19–27%) is more significant than other traditional grains used in the food industry (Ghafoor et al. 2020); therefore, it represents a promising source of bioactive peptides. Segura-Campos et al. (2013) evaluated the antibacterial activity of chia hydrolysates obtained with a sequential alcalase-flavourzyme system during 90- and 60-min. Antibacterial activity was not observed in chia hydrolysates against Escherichia coli, Salmonella Typhi, Shigella flexneri, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, and Streptococcus agalactiae. On the other hand, Coelho et al. (2018) obtained antibacterial protein hydrolysates from partially defatted chia flour using enzymatic hydrolysis with alcalase-flavourzyme for 60 and 180 min, respectively. S. aureus was susceptible to chia hydrolysates at a Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of 2.26 mg/mL and a Minimal Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) of 5 µg/mL. However, CPFs obtained with a pepsin-pancreatin sequential system have not been investigated in terms of antimicrobial activity. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the antibacterial activity of chia peptide fractions and their stability for potential applications in food preservation.

Materials and methods

Plant material and reagents

Chia seeds were harvested in January 2017 in Jalisco State, Mexico. They were identified as seeds of Salvia hispanica L., and a voucher specimen was deposited at the herbarium of the Center of Scientific Investigation of Yucatan (CICY) under the identification number 69494. All chemicals were reagent grade and purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., Merck, and J.T. Baker.

Bacterial strains and culture media

Bacterial strains were selected due to their relation to foodborne diseases. They were provided from the culture collection of the Biotechnology and Microbiology Lab at the Autonomous University of Yucatan: Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 51,414, Bacillus subtilis ATCC 465, Shigella flexneri ATCC 9748, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25,923, Salmonella Typhimurium ATCC 51,821, Salmonella Typhi ATCC 19,430, Salmonella Paratyphi ATCC 9150, Salmonella Enteritidis ATCC 13,076 y Escherichia coli ATCC 43,895. Bacterial strains were maintained at − 20 °C in BHI containing 40% glycerol (v/v). Disk diffusion and microplate dilution assays were performed on Mueller Hinton agar and in BHI broth, purchased from MCD LAB.

Obtention of degummed and defatted chia flour

Impurities and hulls were removed to extract mucilage and oil from chia seeds, according to Salazar et al. (2020). Degummed flour was obtained by removing mucilage from seeds in a distilled water suspension (1:40 w/v) with continuous agitation for 90 min at room temperature. Seeds were dried in a Fisher Scientific stove for 24 h at 50 °C, then milled to obtain a coarse grind and pressed with an 8 tons TRUPPER hydraulic jack to extract chia oil. The resulting thick flour was subjected to a double oil extraction using the Soxhlet method with hexane as the solvent at 70 °C for 2 h. The flour was passed through a 0.5 mm mesh and a Ro-tap sieve shaking system for 30 min with a 140 µm mesh to yield a chia protein-rich flour (CPRF). The percentage of humidity was determined as described by the AOAC gravimetric method (925.09).

Obtention of hydrolysate and peptide fractions

Enzymatic hydrolysis and ultrafiltration were performed, as reported by Martínez Leo and Segura Campos (2020). For the hydrolysis of CPRF, an enzymatic pepsin-pancreatin sequential system was applied for 90 min. A substrate concentration of 4% and an enzyme–substrate ratio of 1:10 were used. The protein-rich fraction was adjusted to pH 2 using 6 N HCl and hydrolyzed by treatment with pepsin (Sigma) for 45 min, followed by treatment with pancreatin (Sigma) for another 45 min; the temperature was kept at 37 °C. Hydrolysis was stopped by heating to 80 °C for 30 min, followed by centrifuging (Hermle Z300K centrifuge) at 3350 × g for 20 min at a temperature of 4 °C to remove the insoluble portion. Subsequently, degree of hydrolysis (DH) was calculated by determining free amino groups with o-phthaldialdehyde (OPA) following the spectrophotometric method by Nielsen et al., (2001) through the equation: DH: (h htot−1) 100; where htot is the total number of peptide bonds per protein equivalent, and h is the number of hydrolyzed bonds. Chia protein hydrolysate underwent an ultrafiltration process using three membranes in ascendant order (1, 3, and 5 kDa). Permeated fractions were collected in sterile containers (F < 1, F 1-3, and F 3-5 kDa). Protein concentration of the hydrolysate and peptide fractions was determined by a colorimetric assay with Folin–Ciocalteau reagent (Sigma) using bovine serum albumin (Sigma) as standard.

Tricine-SDS-PAGE

Tricine-SDS-PAGE was conducted in a vertical gel unit (MiniPROTEAN tetra cell, BioRad), as described by Schägger (2006). Migration was performed using a 16% separating gel added with 6 M urea. Spacer and stacking gel concentrations were 10 and 4%, respectively. Low molecular weight standards (1.06–26.6 kDa) were used as size markers (Ultra-Low Range Molecular Weight Marker, Sigma). The electrophoretic run was conducted at 30 V through the stacking gel and at 90 V until the tracking dye (Coomassie brilliant blue G250) reached the bottom of the gel. The gel was incubated for 30 min in a fixing solution (50% methanol, 10% acetic acid, and 100 mM ammonium acetate), then it was stained with a 0.025% Coomassie brilliant blue and 10% acetic acid solution. The dye was removed using 10% acetic acid. The relative molecular weights of the resolved peptide fractions were compared with those of molecular weight markers, using the curve of molecular weight standards and relative migration distance.

Antibacterial activity

Bacterial susceptibility to CPFs was assessed using in vitro disk diffusion as well as minimum inhibitory and bactericidal concentration by microplate dilution, following the criteria of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI).

Disk diffusion test

Bacterial suspensions with a 0.5 McFarland equivalent turbidity were inoculated in 100 mm Petri dishes with Mueller Hinton agar using a sterile swab. Subsequently, disks of 6 mm in diameter were placed onto the surface of the agar plate. Disks were loaded with 10 μL of each CPF at different concentrations (500, 250, and 125 μg/mL). Penicillin and gentamicin (500 μg/mL) were used as positive controls for Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Benzoic acid (1%) was also included as a control, while distilled water was used as a negative control. Inoculated plates were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. After incubation, inhibition zones were measured. Bacterial susceptibility to CPFs was determined by inhibition diameter: no inhibition zone “- “ (0 mm), inactive “ + ” (< 10 mm), partially active “ + + ” (10–13 mm), and active “ + + + ” (> 14 mm)(Valgas et al. 2007).

Minimum inhibitory and minimum bactericidal concentrations

MIC and MBC values were determined against susceptible strains, following the method reported by Coelho et al. (2018) with adjustments. Sterile 96 well microplates (Costar) containing 100 μL of BHI broth, 100 μL of CPFs (1000, 850, 700, 550, 400, 250 μg/mL) and 100 μL of bacterial inoculum (80 μL of BHI broth and 20 μL of sterile saline with bacteria adjusted to a 0.5 McFarland equivalent). The inhibition was evaluated through absorbance at 620 nm in a Multiskan Plus microplate reader (Thermo Electron Corporation) after incubation for 24 h at 37 °C. The absorbance of wells with CPFs at different concentrations, positive control (well containing BHI broth), and negative control (well with bacterial inoculum) was considered to calculate MIC values. MIC was established as the concentration at which 50% of bacterial growth reduction was detected in culture media with CPFs. For MBC determination, 15 μL from wells exhibiting bacterial growth inhibition were extracted and inoculated on Mueller Hinton agar. Inverted plates were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. MBC was considered as the concentration at which bacterial growth was not observed.

Temperature, pH, and protease effects on antibacterial activity

Stability assays were carried out as proposed by Essig et al. (2014) with adjustments to investigate the resistance of the most active CPF under different food processing conditions, such as temperature, pH, and proteolysis. Thermal stability was tested in PBS buffer, pH 7.4, at 4, 25, 60, 80, 100 °C for 1 h of incubation. The pH stability was determined after incubation for 1 h at room temperature in different buffer solutions: 250 mM KCl/HCl (pH 2), 100 mM sodium acetate (pH 4 and 5), 200 mM sodium phosphate (pH 6), 100 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8), and 100 mM carbonate-bicarbonate (pH 10). The effect of trypsin and pepsin on CPF activity was evaluated by incubation with respective proteases at 37 °C for 3 h in a reaction mixture containing a ratio of 1:10 (w/w) of protease to CPF. For pepsin, the reaction was conducted in 250 mM KCl/HCl buffer (pH 2) and trypsin in 100 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 8). After incubation, the samples were centrifuged at 12,000 × g, and the antibacterial activity of the supernatant was tested by disk diffusion. A stock solution of the CPF (700 µg/mL) was used as a positive control. In order to ensure the buffers themselves were not contributing to any inhibition, they were used as negative controls.

Multicriteria analysis

The identification of peptide sequences in F < 1 was used to screen potential AMPs. The analysis was performed following the Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS), according to Yoon and Kim (2017). This multicriteria analysis is based on the concept that the chosen alternative has the longest geometric distance from the negative ideal solution and the shortest geometric distance from the positive ideal solution. First, a decision matrix was established (1067 peptide sequence × 7 physicochemical indicators). Then, the normalized decision matrix and the weighted normalized decision matrix were calculated. The positive and negative ideal solutions were determined, and the Euclidean distance between them was measured. Finally, the relative closeness (Rc) to the ideal solution was calculated, and the alternatives were ranked based on Rc values (0–1). The alternative closest to 1 was considered the best alternative.

Statistical analysis

All the experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3). Results were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation and evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (p < 0.05). Tukey’s post hoc test was used to establish statistical differences between CPFs treatments. Statgraphics Centurion XVI.II and GraphPad Prism 8 were employed to analyze data.

Results and discussion

Degummed and defatted flour

From the removal of mucilage and oil from chia seeds together with grinding and sieving procedures, a CPRF was obtained, showing a percentage of humidity of 8.4% ± 0.04 and protein content of 75.28% ± 1.08. The degumming process using water suspension allowed the removal of soluble fiber, reducing the percentage of non-proteinaceous compounds in PRCF. Double oil extraction also contributed significantly to the obtention of high levels of proteins in PRCF. This is supported by research conducted by Segura-Campos et al. (2013) in a chia protein-rich fraction, which showed that increasing protein content is promoted by reducing fiber and lipid content.

Chia protein hydrolysate and peptide fractions

Enzymatic hydrolysis with a sequential pepsin-pancreatin system of CPRF yielded a chia protein hydrolysate (CPH) with a resulting degree of hydrolysis of 33.79% ± 2.14. Fractionation was achieved with ultrafiltration of CPH, producing 3 CPFs. Their protein contents are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Protein content of CPH and CPF

| CPH/CPF | Protein content (mg /mL) |

|---|---|

|

CPH F < 1 kDa F 1-3 kDa F 3-5 kDa |

0.507 0.02a 0.074 0.02b 0.069 0.01b 0.059 0.02c |

Data expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). a−cDifferent letters represent significant statistical differences between chia protein derivatives with a one-way ANOVA and a Tukey’s post hoc test (p < 0.05)

CPH obtained with sequential pepsin-pancreatin enzymatic hydrolysis showed a degree of hydrolysis (DH) greater than 10%, which classified CPH as an extensive hydrolysate according to Vioque et al. (2001). A higher DH was registered by Segura-Campos et al. (2013) for chia hydrolysates (43.8%) using alcalase-flavourzyme for 150 min. Variations in DH were influenced by prolonged incubation with proteolytic enzymes. Pepsin-pancreatin enzymatic system for 90 min used in this study achieved an extensive DH in lower reaction time than that mentioned above with alcalase-flavourzyme. The generation of extensive DHs facilitates the production of hydrolysates with potential biological activities, such as antibacterial activity. Fractionation according to molecular weight was achieved through ultrafiltration. In this work, the protein content of CPFs (F < 1. F 1-3, F 3-5 kDa) depended on specific molecular weight peptide abundance in CPH.

Electrophoretic profile

The tricine-SDS-PAGE analysis revealed CPFs' molecular weight distribution. Bands in F < 1 were below 1.06 kDa, while F 1-3 revealed three low-intensity bands of 1.6, 2 y 2.4 kDa. F 3-5 exhibited the presence of 4 bands of 2.1, 2.5, 3.2, and 4.7 kDa. CPFs electrophoretic profile showed low molecular weight bands in Tricine-SDS-PAGE, corroborating the effectiveness of enzymatic hydrolysis, as well as the ultrafiltration process. The results presented in this work also showed that molecular weight bands were distributed according to the molecular weight cutoff determined by ultrafiltration membranes. The ascendant order of membranes (from 1 to 5 kDa) allowed the obtention of low molecular weight peptides selectively.

Antibacterial activity of CPFs

The antibacterial activity of CPFs was evaluated through disk diffusion assay. F < 1, F 1-3, and F 3-5 were considered inactive against all Gram-negative bacteria tested (Shigella flexneri, Salmonella Typhimurium, Salmonella Typhi, Salmonella Paratyphi, Salmonella Enteritidis, and Escherichia coli O:157:H7). Gram-positive bacterial susceptibility to CPFs can be observed in Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, and Listeria monocytogenes. The degree of inhibition was categorized according to the inhibition diameter, and these results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Degree of inhibition of bacterial growth produced by CPFs

| Treatment | SA | BS | LM | EC | ST | STM | SP | SE | SF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C + | + + + | + + + | + + + | + + + | + + + | + + + | + + + | + + + | + + | |

| C- | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| BA | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| F < 1 | C1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| C2 | + + | + + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| C3 | + + + | + + + | + + | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| F 1-3 | C1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| C2 | + + | + + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| C3 | + + | + + | + + | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| F 3-5 | C1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| C2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| C3 | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

No inhibition zone (-), diameter < 10 mm “Inactive” ( +), diameter between 10 and 13 mm “partially active” (+ +) and diameter > 14 mm “active” (+ + +) (Valgas et al. 2007). Bacterial strains: SA (Staphylococcus aureus), BS (Bacillus subtilis), LM (Listeria monocytogenes), EC (Escherichia coli), ST (Salmonella Typhi), STM (Salmonella Typhimurium), SP (Salmonella Parathyphi), SE (Salmonella Enteritidis), SF (Shigella flexneri). C + (500 µg /mL Penicillin/Gentamicin), C- (distilled water), BA (1% Benzoic acid), C1 (500 µg /mL), C2 (250 µg /mL), C3 (125 µg /mL)

F < 1 was considered active at the highest concentration tested (500 µg/mL) against S. aureus and B. subtilis because the inhibition diameter was greater than 14 mm. At the same concentration, F < 1 was partially active in inhibiting L. monocytogenes growth. However, at a 250 µg/mL concentration, F < 1 was classified as inactive. F 1-3 was considered partially active against the three Gram-positive test strains at 500 µg/mL. Contrarily, it was inactive at lower concentrations against L. monocytogenes since the inhibition diameter registered was < 10 mm. F 3-5 exhibited bacterial inhibition with insufficient diameter to be considered active at the highest concentration against all strains. At concentrations below 250 and 125 µg/mL, inhibition halos were reported between 7 and 9 mm, respectively. The highest inhibition degrees were achieved at 500 µg/mL on Gram-positive bacteria. S. aureus registered inhibition halos of 17.332 ± 0.58 mm (F < 1), 14.667 ± 0.57 mm (F 1–3) and 7.333 ± 0.57 mm (F 3-5). B. subtilis showed more susceptibility than other Gram-positive strains tested, with inhibition diameters of 17.668 ± 0.57 mm (F < 1), 16.666 ± 0.054 mm (F 1-3), and 8.233 ± 0.54 mm (F 3-5). CPFs were less active against L. monocytogenes than S. aureus and B. subtilis.

Inhibition of Gram-positive bacteria generated by CPFs in disk diffusion tests was compatible with results reported by Coelho et al. (2018) in chia protein hydrolysates, which were inactive in the inhibition of Gram-negative E. coli O157:H7 and active against Gram-positive S. aureus. Structural differences between them could explain more susceptibility in Gram-positive than Gram-negative bacteria. Compared with Gram-negative bacteria, Gram-positive have a higher proportion of negatively charged membrane components, such as phosphatidylglycerol (Malanovic and Lohner 2016). This feature increases the electrostatic attraction between positively charged antibacterial peptides and bacterial membranes. In this regard, less susceptibility to CPFs observed in L. monocytogenes could be attributed to variations in the fatty acid composition of the cellular membrane. MIC and MBC values of F < 1, F 1-3 against Gram-positive strains were detected by microplate dilution. In the case of F 3-5, MIC values could not be defined after bacterial growth reduction was below the 50% established by Coelho et al. (2018) for MIC determination. The results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

MIC values (µg /mL) of CPFs

| CPF | SA | BS | LM |

|---|---|---|---|

| F < 1 | 662.69 ± 5.2796b | 642.82 ± 4.2865b | 635.47 ± 3.6532b |

| F 1-3 | 818.60 ± 2.5039a | 807.89 ± 3.0574a | 818.94 ± 2.8519a |

| F 3-5 | ND | ND | ND |

Mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). a−bDifferent letters represent significant statistical differences between CPFs with a one-way ANOVA and a Tukey’s post hoc test (p < 0.05). ND Not detected. Bacterial strains: SA (Staphylococcus aureus), BS (Bacillus subtilis), LM (Listeria monocytogenes)

MIC values registered in the most active CPF (F < 1) were lower than reported by Coelho et al. (2018) for chia protein hydrolysates (2.26 mg/mL) against S. aureus. Variations could derive from the enzymatic systems used for hydrolysis and the differences between the chia protein hydrolysate and peptide fraction composition. A hydrolysate contains a mixture of diverse peptides, while the peptide fraction is selectively designed to contain peptides of specific molecular weights. MBC was not detected at the concentrations tested in this study. This suggests that higher concentrations of CPFs are required to observe a bactericidal effect.

Effect of temperature, pH, and protease on antibacterial activity

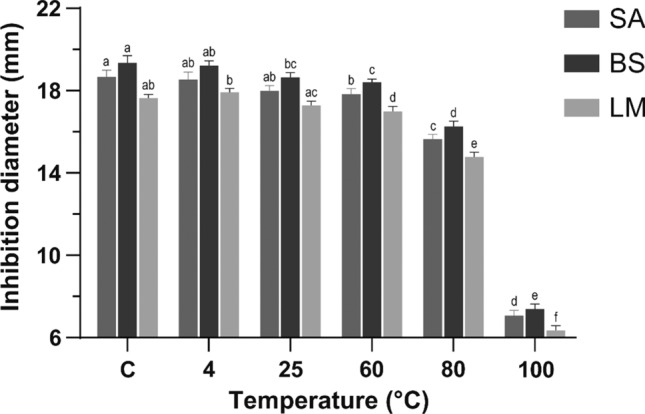

A critical condition for AMPs’ application in the food industry is thermostability, which was determined after incubation of F < 1 at 4, 25, 60, 80, and 100 °C for 1 h. Inhibition diameters produced by F < 1 are presented in Fig. 1. The highest inhibition diameters were 17.91 ± 0.19, 19.22 ± 0.22, and 18.54 ± 0.35 mm for L. monocytogenes, B. subtilis, and S. aureus respectively, when samples were incubated at 4 °C. Data registered no significant statistical difference between diameters generated by F < 1 incubated at 4 °C and the control. There were no differences between samples incubated at 25 and 60 °C. After incubation at a temperature range from 4 to 80 °C, F < 1 was active, generating inhibition diameters > 14 mm. Significant loss of F < 1 antibacterial activity was not observed until the temperature was > 80 °C. At 100 °C, inhibition diameters were less than 10 mm, and therefore, they were classified as inactive.

Fig. 1.

Effect of temperature on antibacterial activity of F < 1 against S. aureus (SA), B. subtilis (BS) and L. monocytogenes (LM). a−f Different letters represent significant statistical differences between bars of the same color with a one-way ANOVA and a Tukey’s post hoc test (p < 0.05)

These results showed that F < 1 remained active after incubation at temperatures close to 100 °C, which could be of interest for food applications. According to results herein reported, F < 1 can preserve activity up to 80 °C for 1 h, which indicates that its antimicrobial activity could be preserved after a batch pasteurization process (63 °C–30 min) or an HTST (High Temperature Short Time) continuous flow pasteurization (72 °C–15 s) in dairy products. Processing at higher temperatures, such as HHST (Higher Heat Shorter Time) pasteurization (> 89 °C ~ 1 s) and ultra-pasteurization (> 138 °C–2 s), could compromise F < 1 stability (FDA 2017). In designing a thermal process, a minimum cumulative total lethality of F90°C (i.e., equivalent accumulated time at 90 °C = 10 min) is adequate for pasteurized fish and fishery products (FDA 2020). Following this parameter, F < 1 could lose or reduce its antibacterial activity as the temperature rises to 100 °C in fish and fishery products. Moreover, liquid egg products undergo heat treatments at specific times (3.55–6.2 min) and temperatures (55.6–63.3 °C) (C.F.R. 2012). Therefore, these treatments would not affect the antibacterial activity of F < 1 since temperatures applied are below 80 °C.

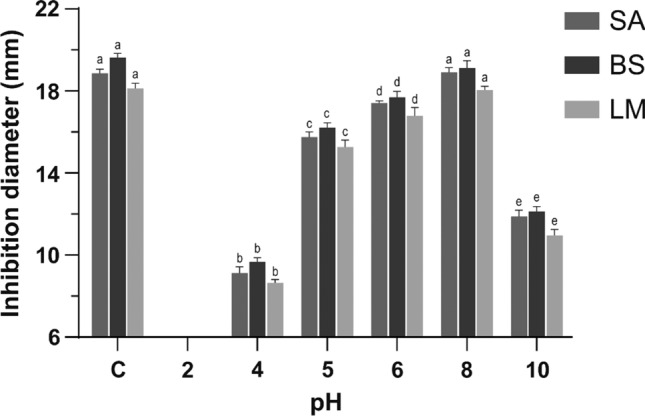

Results on pH stability assays after incubation at pH 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, and 10 (Fig. 2) revealed that the greatest inhibition diameters were reported at pH 8 with inhibition zones of 18.92 ± 0.22, 19.12 ± 0.35, and 18.04 ± 0.18 mm against S. aureus, B. subtilis, and L. monocytogenes, respectively. A significant statistical difference was not observed between F < 1 incubated at pH 8 and control. On the other hand, the antibacterial activity of F < 1 incubated at pH 2 was considered null since inhibition was not observed. Consequently, F < 1 was stable in a pH range from 5 to 8 with inhibition diameters > 14 mm. Inhibition diameters were notably reduced in F < 1 incubated at pH 10 with values between 10 and 13 mm, classifying as partially active.

Fig. 2.

Effect of pH on the antibacterial activity of F < 1 against S. aureus (SA), B. subtilis (BS) and L. monocytogenes (LM). a−e Different letters represent significant statistical differences between bars of the same color, with a one-way ANOVA and a Tukey’s post hoc test (p < 0.05)

The pH range of some common foods is 7.1–7.9 for eggs, 6.3–8.5 for milk, 5.3–5.8 for bakery products, 5.0–7.0 for meat, 4.8–7.3 for fish, 4.0–7.0 for vegetables, 3.3–7.1 for fruits and 3.1–4.5 for berries (FDA 2012). F < 1 was more active at pH 8; consequently, it may show a higher protective effect against microorganisms in products with pH values closer to neutrality, as in eggs or milk, and lower antibacterial activity in acid foods, such as berries and fruits.

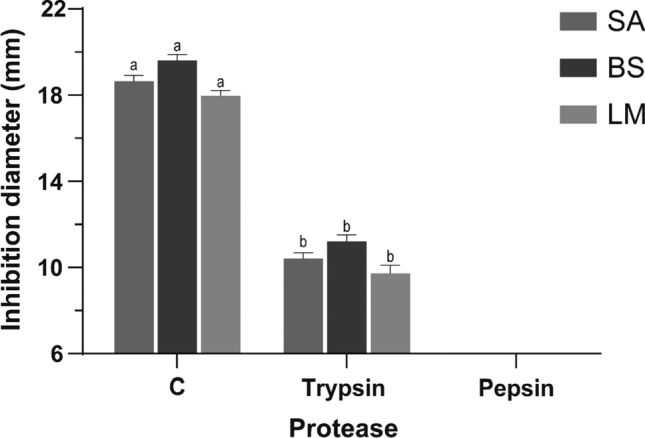

Protease susceptibility of F < 1 was analyzed after incubation with pepsin and trypsin for 3 h. Results showed significant statistical differences between inhibition diameters of F < 1 incubated with proteases and control (Fig. 3). Samples treated with trypsin were partially active since they produced inhibition diameters between 10 and 13 mm against S. aureus and B. subtilis. However, they were considered inactive in inhibiting L. monocytogenes (inhibition < 10 mm). F < 1 treated with pepsin exhibited no inhibition zones against any bacteria.

Fig. 3.

Effect of proteases on antibacterial activity of F < 1 against S. aureus (SA), B. subtilis (BS) and L. monocytogenes (LM). a−b Different letters represent significant statistical differences between bars of the same color, with a one-way ANOVA and a Tukey’s post hoc test (p < 0.05)

The antimicrobial activity of F < 1 was not preserved after exposure to proteases such as trypsin and pepsin. Pepsin and chymosin are used as coagulants in cheese production, while trypsin, chymotrypsin, and pepsin have been used to degrade gluten in grains (Zhang et al. 2018). F < 1 could present limitations for application in the processes mentioned above. Different strategies have been addressed to increase its stability to degradation. Some of these include the introduction of unnatural amino acids and the modification of terminal regions by cyclization. Incorporating D-amino acids has been shown to increase the stability of an AMP analogous to W3R6 in the presence of trypsin for up to 72 h (Li et al. 2019). These could be valuable tools to preserve AMPs’ stability in processes like proteolysis, which are used for the transformation of food products. However, further studies are needed to evaluate the interaction of F < 1 from chia with food components.

Taken together, these results imply that F < 1 could be suitable for dairy products that are exposed to a batch pasteurization process or an HTST (High Temperature Short Time) continuous flow pasteurization. Dairy products have the optimal pH range for the antibacterial activity of F < 1. However, cheeses and dairy products that require the use of proteases in their production, such as trypsin and pepsin, should be avoided. Meat products are also appropriate for the optimal activity of F < 1 since the pH in these products is between 5.0 and 7.0. As reported in antibacterial assays, F < 1 inhibits the growth of important gram-positive pathogens (L. monocytogenes and S. aureus), which frequently contaminate dairy and meat products. Given this set of conditions, these products are suggested as potential food systems for incorporating F < 1.

The effectiveness of an AMP is generally lower in food systems than in growth mediums. To reach the same efficiency in food systems, it is often necessary to add an AMP amount about ten times higher than that in a culture medium (Gharsallaoui et al. 2016). The suitability of F < 1 for dairy and meat products suggests that it is needed to adapt the inhibitory concentrations to these specific food systems. According to the Codex General Standard for Food Additives, the use of nisin as an antimicrobial food additive is permitted at a maximum level of 12 mg/kg in dairy-based desserts and flavored fluid milk drinks. On the other hand, a maximum 25 mg/kg level is established in heat-treated processed comminuted meat and poultry, as well as heat-treated processed meat and poultry in whole pieces or cuts (GSFA 2019). These levels (12–25 mg/kg) could indicate the potential application amounts of F < 1 in the products of interest.

Potential antimicrobial peptide sequences in F < 1

To evaluate the antimicrobial potential of peptide sequences in F < 1, they were ranked by the TOPSIS approach using the following criteria: (1) Chain length (5–10 amino acids); (2) Net charge (+ 3 – + 9); (3) Hydrophobicity (30–50%); (4) The presence of arginine, tryptophan or lysine; (5) Cationic: hydrophobic amino acid proportion (4:5); (6) Hydrophobic amino acids (isoleucine, valine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, tryptophan) at position 5, 7 or 9; and (7) Presence of lysine as either N- or C- terminal (Mikut et al. 2016; Aguilar-Toalá et al. 2020; Yan et al. 2020). The analysis showed that KLKKNL was ranked at the top as the alternative with the nearest distance to the ideal positive solution and the farthest distance to the negative ideal solution, followed by KKYRVF, MLKSKR, MSKAKPGRSM, and SVVAKAPVGKR. Since the amino acid sequence contributes to the antimicrobial activity of AMPs, it is highlighted that the presence of lysine in KLKKLN provides a net positive charge (+ 3). According to Mikut et al. (2016), a primary rule for activity is dictated by a balance of positive charge and hydrophobicity. Consistent with this interpretation, KLKKLN contains amino acid residues in its sequence that confer not only a cationic character but hydrophobicity, which is also required for the interaction with bacterial membranes.

Conclusions

Based on the evidence presented in this work, a 90 min hydrolysis using a pepsin-pancreatin system is considered useful for the release of short chain peptides, and the ascending order of ultrafiltration membranes favored the concentration of peptides (< 1 kDa) in F < 1. The peptide fraction F < 1 reported the highest antibacterial activity against L. monocytogenes, suggesting its potential as an antibacterial agent in food products with a high incidence of this bacterium, such as dairy and meat products. F < 1 could resist heat treatments such as HTST pasteurization of milk and pasteurization of egg and egg products. It might have an antimicrobial role in foods with pH values ranging between 5 and 8, with better performance in foods close to neutrality than in acidic foods. The antimicrobial activity of F < 1 could be restricted in processes involving proteases such as trypsin or pepsin. However, new strategies such as incorporating D-amino acids or the cyclization of the terminal regions may promote protease resistance and, consequently, their stability in foods involving proteolytic processes. It is expected that F < 1 exhibits antimicrobial activity in dairy and meat products at around 12–25 mg/kg, preserving its activity under adequate pH and temperature processing conditions. Incorporation of F < 1 into food systems could contribute to control foodborne diseases caused by L. monocytogenes and S. aureus. Additionally, future research is necessary to determine the antimicrobial activity of short-chain peptides from chia peptide fraction F < 1, such as KLKKNL.

Acknowledgements

This is study is a result of the research conducted within the Project 119RT0567 financially supported by CITED. ALM acknowledges CONACyT MSc Scholarship (CVU 933185).

Author’s Contributions

MRSC conceived the project, supervised the work, reviewed the manuscript, and was responsible for project administration; ALM performed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; ABFO contributed materials and methodology; LFMM performed the TOPSIS analysis of peptide sequences.

Funding

This work was supported by CYTED (project 119RT0567).

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was not required for this research.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aguilar-Toalá JE, Deering AJ, Liceaga AM. New Insights into the Antimicrobial properties of Hydrolysates and peptide fractions derived from Chia Seed (Salvia hispanica L.) Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2020;12(4):1571–1581. doi: 10.1007/s12602-020-09653-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- C.F.R. (2012) 9 CFR 590. Inspection of egg and egg products

- Coelho MS, Soares-Freitas RA, Areas JA, et al. Peptides from Chia present antibacterial activity and inhibit cholesterol synthesis. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2018;73:101–107. doi: 10.1007/s11130-018-0668-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dash P, Ghosh G. Fractionation, amino acid profiles, antimicrobial and free radical scavenging activities of Citrullus lanatus seed protein. Nat Prod Res. 2017;31:2945–2947. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2017.1305385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essig A, Hofmann D, Münch D, et al. Copsin, a Novel Peptide-based Fungal Antibiotic Interfering with the Peptidoglycan Synthesis. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:34953–34964. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.599878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA (2012) Factors that affect microbial growth in food. In: Food pathogenic microorganisms and natural toxins, Segunda. pp 263–265

- FDA (2017) Grade “A” Pasteurized Milk Ordinance (PMO). 1–426

- FDA (2020) Fish and fishery products hazards and controls guidance. Fish Fish. Prod. Hazard Control Guid. Fourth Ed. 1–401

- Ghafoor K, Ahmed IAM, Özcan MM, et al. An evaluation of bioactive compounds, fatty acid composition and oil quality of chia (Salvia hispanica L.) seed roasted at different temperatures. Food Chem. 2020;333:127531. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharsallaoui A, Oulahal N, Joly C, Degraeve P. Nisin as a food preservative: Part 1: physicochemical properties, antimicrobial activity, and main uses. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2016;56:1262–1274. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2013.763765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GSFA (2019) Food additive details: Nisin (E 234). In: Codex Gen. Stand. Food Addit. http://www.fao.org/gsfaonline/additives/details.html?id=1&print=true&lang=en

- Krepker M, Shemesh R, Danin Y, et al. Active food packaging fi lms with synergistic antimicrobial activity. Food Control. 2017;76:117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2017.01.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Liu T, Liu Y, et al. Antimicrobial activity, membrane interaction and stability of the D-amino acid substituted analogs of antimicrobial peptide W3R6. J Photochem Photobiol B Biol. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2019.111645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Wu X, Hou W, et al. Structure and function of seed storage proteins in faba bean (Vicia faba L.) Biotech. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s13205-017-0691-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malanovic N, Lohner K. Antimicrobial Peptides targeting gram-positive bacteria. Pharmaceuticals. 2016 doi: 10.3390/ph9030059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Leo EE, Segura Campos MR. Neuroprotective effect from Salvia hispanica peptide fractions on pro-inflammatory modulation of HMC3 microglial cells. J Food Biochem. 2020;44:e13207. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.13207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikut R, Ruden S, Reischl M, et al. Improving short antimicrobial peptides despite elusive rules for activity. Biochim Biophys Acta - Biomembr. 2016;1858:1024–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa AA, Al-askar AA, Almaary KS, et al. Antimicrobial activity of some plant extracts against bacterial strains causing food poisoning diseases. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2018;25:361–366. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen PM, Petersen D, Dambmann C. Improved method for determining food protein degree of hydrolysis. J Food Sci. 2001;66:642–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2001.tb04614.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pisoschi AM, Pop A, Georgescu C, et al. An overview of natural antimicrobials role in food. Eur J Med Chem. 2018;143:922–935. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.11.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar Vega IM, Quintana Owen P, Segura Campos MR. Physicochemical, thermal, mechanical, optical, and barrier characterization of chia (Salvia hispanica L.) mucilage-protein concentrate biodegradable films. J Food Sci. 2020;85:892–902. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.14962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos JCP, Sousa RCS, Otoni CG, et al. Nisin and other antimicrobial peptides: production, mechanisms of action, and application in active food packaging. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2018;48:179–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2018.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schägger H. Tricine – SDS-PAGE. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:16–23. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segura-Campos MR, Salazar-Vega IM, Chel-Guerrero LA, Betancur-Ancona DA. Biological potential of chia (Salvia hispanica L.) protein hydrolysates and their incorporation into functional foods. LWT - Food Sci Technol. 2013;50:723–731. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2012.07.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silva MM, Lidon FC. Food preservatives – An overview on applications and side effects. Emirates J Food Agric. 2016;28:366–373. doi: 10.9755/ejfa.2016-04-351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valgas C, Machado de Souza S, Smânia E, Smânia A., Jr Screening method to determine antibacterial activity of natural products. Brazilian J Microbiol. 2007;38:369–380. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822007000200034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vioque J, Clemente A, Pedroche J, Del M, Yust M, Millán F. Obtención y aplicaciones de hidrolizados protéicos. Grasas Aceites. 2001;52:132–136. doi: 10.3989/gya.2001.v52.i2.385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2015) WHO estimates of the global burden of foodborne diseases: Foodborne disease burden epidemiology reference group 2007–2015. Geneva

- Yan J, Bhadra P, Li A, et al. Deep-AmPEP30: Improve short Antimicrobial Peptides prediction with deep learning. Mol Ther - Nucleic Acids. 2020;20:882–894. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon KP, Kim WK. The behavioral TOPSIS. Expert Syst Appl. 2017;89:266–272. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2017.07.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, He S, Simpson BK. Enzymes in food bioprocessing — novel food enzymes, applications, and related techniques. Curr Opin Food Sci. 2018;19:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cofs.2017.12.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Not applicable.