Abstract

Dithiocarbamates constitute an important class of broad-spectrum antifungal compounds used extensively in agriculture, including in the cultivation of spices. Maximum residue limits for these compounds have been enforced by several importing countries in international food trade. Validation of analytical methods for dithiocarbamates in spices have not been reported previously. A quick and sensitive method for estimation of total dithiocarbamates as carbon disulphide (CS2) using GC-MS in two major spices, viz. small cardamom (Elettaria cardamomom) and black pepper (Piper nigrum) was optimized and validated. Dithiocarbamate residues in these spice matrices were extracted and subjected to acid hydrolysis followed by reduction to CS2, which was then quantitatively absorbed into isooctane and analysed using GC-MS, employing selected ion monitoring and post-run mid-column backflush technique. For fortification levels from 0.1 to 1.0 mg kg− 1, recoveries obtained ranged from 75 to 98% in cardamom and 76–98% in black pepper, with intra-day precision (RSDr) < 12% and inter-day precision (RSDR) < 15% in all cases. Limit of Quantification of 0.05 mg kg− 1 was achieved in both spices. It was found that there was negligible interference in quantitative accuracy due to essential oils present in the two spices studied. Matrix effect was seen to be suppressive in the two spices studied, and sufficiently low to exclude the use of matrix-matched calibration in routine quantitative analysis. The optimized analytical method was found to be suitable for evaluation of compliance of real samples against the Codex maximum residue limits for cardamom and black pepper. Safety evaluation for human consumption, based on the incidence of Dithiocarbamate residues, was performed in real samples of cardamom and black pepper. This method offers the possibility of extending applicability to other spices also.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13197-022-05462-9.

Keywords: Dithiocarbamate, Fungicide, Pesticide residue analysis, GC-MS, Method validation

Introduction

The use of dithiocarbamate (DTC) fungicides has been prevalent in agriculture for a long time. The broad-spectrum antifungal activity of these compounds, their comparatively low toxicity profiles, and their low cost of manufacture have resulted in their widespread application in the control of fungal diseases in plants, especially in combination with new systemic antifungal agents (Crnogorac and Schwack 2009; Mujawar et al. 2014). DTC fungicides are generally non-systemic in nature and, due to their low solubility in water, are likely to remain at the site of application without much dissipation into the environment. As a consequence of this, the risk of indiscriminate use of this class of fungicides leading to residues in agriculture products above regulatory limits becomes a concern. Thus, monitoring residues in agriculture products for residues of dithiocarbamates for compliance with international regulations and for assessing food safety risks is an important consideration.

Small cardamom or Malabar cardamom (Elettaria cardamom) is often called the ‘queen of spices’ because of its pleasing aroma and taste, and is a popular spice extensively traded all over the world (Ravindran and Madhusoodanan 2002). During cultivation this spice is affected by many diseases of fungal origin, such as capsule rot, rhizome rot, leaf blight etc., and for the management of these diseases, DTC fungicides are commonly used (Thomas and Suseela Bhai 1995). Similarly, black pepper (Piper nigrum) is another important, internationally traded spice used extensively in culinary applications across the world. This spice is also significantly affected by foot rot disease of fungal origin (Phytophthora capsica), and for disease management, DTC fungicides are recommended (Ravindran 2000).

Regulatory agencies have stipulated strict maximum residue limits (MRLs) for DTC residues in these spices. E.g., the Codex Alimentarius Commission (CAC) has fixed an MRL of 0.1 mg kg− 1 for DTC in cardamom and black pepper (Codex MRL Cardamom 2015; Codex MRL Pepper 2015). The European Union (EU) also has set an MRL of 0.1 mg kg− 1 for DTC in cardamom and seed spices (EUR-Lex 2021). Considering that cardamom and black pepper are extensively used in culinary applications across the world and also contribute substantially to global spice trade, the development and validation of a fast and easy analytical method for the determination of DTC in these spices is very important to verify compliance with MRL regulations as well as to ensure food safety to consumers.

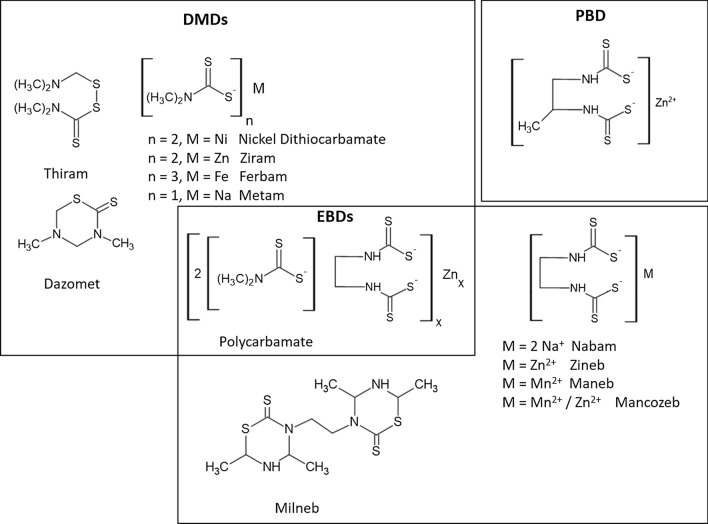

Based on their chemical structure, the DTC compounds can generally be categorized into three subclasses, viz. dimethyldithiocarbamates (DMDs), ethylenebisdithiocarbamates (EBDs), and propylenebis dithiocarbamates (PBDs). A further subclass of compounds that belong to both DMD and EBD are also defined, called polycarbamates (Crnogorac and Schwack 2009; Kakitani et al. 2017). Typically, these compounds exist complexed with transition metal ions, except in the case of thiram, dazomet and milneb. Metiram is a mixture of polythiuram disulphides and zinc ammoniate bis(dithiocarbamate). The classification of DTC compounds used in agriculture is summarized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Classification of DTC on the basis of chemical structure

There are two important problems associated with the analysis of DTC residues: solubility and stability (Crnogorac et al., 2009). Among the DTC compounds, ziram, ferbam and thiram are sparingly soluble in water, and soluble in some organic solvents like chloroform, carbon disulfide, acetone acetonitrile. The compounds metam and nabam are soluble in water, but less so in organic solvents. Apart from these compounds, the majority of the DTC compounds are practically insoluble in water and organic solvents alike. For regulatory purposes, DTC fungicides are considered together as a class and maximum residue limits are assigned. Thus, the solubility issues among DTC compounds mean that it is practically impossible to devise a single extraction method that can reliabily extract all the DTC compounds together. Apart fromt this soluility issue, DTC compounds become unstable when coming into contact with acidic plant extarcts, and decompose into carbon disulfide and the corresponding amino compound. Thus, extracting a homogenized plant matrix using polar or organic solvents, which is the normal method for residue analysis, is not found to be effective in the case of DTC residues.

One of the major techniques employed for analysis of DTC residues is converting the DTCs present in the sample quantitatively into CS2, and then analysing the CS2 evolved using techniques like spectrophotometry (Kesari and Gupta 1998; Caldas et al. 2001), gas chromatography (Dubey et al. 1997; Mujawar et al. 2014; Gras et al. 2017; Arslan et al. 2019; Chawla et al. 2019), and liquid chromatography (Gustafsson and Thompson 1981; Oellig and Schwack 2017). Alternative approaches have been developed which involve a methylation step, followed by modified QuEChERS extraction and detection of the methylated compounds using LC-MS/MS (Kakitani et al. 2017; Xu et al. 2017). These methods are able to distinguish between different groups of DTC compounds, but are still limited by the solubility constrants of individual DTC compounds in general.

Although previous studies have covered the analysis of DTC residues in fruits, vegetables, oil seeds etc. (Kesari and Gupta 1998; Mujawar et al. 2014; Oellig and Schwack 2017; Chawla et al. 2019), the analysis of these compounds in spices has not been reported. Since DTC compounds are non-systemic and are expected to be present only as a surface contamination, homogenization is not considered to be an important step in DTC analysis. However, spices are usually used in ground / crushed forms in culinary applications and spices like cardamom and black pepper have significant amounts of essential (volatile) oils in them. Thus the possibility of interference of the chemical components in these essential oils, in the formation of CS2 evolved from DTC compounds during analysis, is an important factor to be considered in optimizing this method for spices. This study presents the successful development and validation of a method for estimation of total DTC in two spices viz. cardamom and black pepper. The method offers the possibility of extending the applicability to other spices also.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and apparatus

All chemicals and reagents used for analysis were of analytical grade, and extraction solvents were verified as free from interferences in GC-MS analysis prior to commencing analysis. Carbon disulphide (CS2, Merck Emplura® grade, 99.5% purity), isooctane (Merck Emparta® grade, 99% purity), stannous chloride (SnCl2) and hydrochloric acid were purchased from Merck, India. Helium gas of 99.9995% purity used in GC-MS as carrier gas was obtained from Bhuruka Gases, Bangalore, India. Thiram (98.4%) certified reference manterial used for method validation was purchased from Sigma Aldrich India. For the hydrolysis reaction, stoppered glass bottles from Schott Duran, Germany were used. In order to avoid the possibility of interferences from plastic and latex surfaces, only glass containers and apparatus (Borosil, India) were used for volume transfers and the extraction process until the reaction was completed, and powder-free nitrile gloves were used by analysts.

Reference standard of CS2for calibration

To prepare 2000 µg mL− 1 stock standard solution of CS2 (density 1.26 g cm− 3), 79 µl of CS2 was pipetted into a 50 mL volumetric flask containing about 40 mL of isooctane, shaken well, and then made up to volume with isooctane. From this stock standard, intermediate standards in the range 100 µg mL− 1 to 10 µg mL− 1 were prepared by serial dilutions with isooctane. From these, calibration standards in the range 0.025 to 0.5 µg mL− 1 were then prepared by appropriate dilution with isooctane. Matrix matched standard calibration solutions of CS2 were prepared in the same concentration ranges using the final isooctane extracts from blank samples of black pepper and cardamom, as described in the section on extraction below.

Thiram standard for recovery studies

For spike recovery studies, thiram stock standard of 1000 µg mL− 1 was prepared by dissolving 10 mg of the standard in ethyl acetate and making up to the mark in a 10 ml volumetric flask. From this stock solution, serial dilution was used to obtain working standard of 100 µg mL− 1, which was used to prepare fortified samples of black pepper and cardamom with appropriate concentrations.

Preparation of reaction mixture

The reaction mixture for hydrolysis of the DTC compounds to CS2 was prepared by weighing out accurately 15 g of SnCl2 and dissolving in concentrated HCl in a 500 mL volumetric flask. This solution was then added to 500 mL water and stirred until a clear solution was obtained.

Instrumentation

The instruments used for sample preparation work included analytical balance (AUW220D, Shimadzu, Japan), high speed centrifuge (Z383, Hermle, Germany) and a covered, adjustable-temperature water bath (Narang, India). A gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer system (Agilent 7890 GC with 7693 Autosampler coupled to 7000 Triple Quad) was used for quantitative analysis.

Samples

Cardamom and black pepper samples for the study were collected from farms in Idukki District, in the state of Kerala, India. For evaluation of matrix interference effects, control samples of both spices were procured from spice farms following organic agriculture practices without any history of usage of DTC compounds for management of fungal diseases, and these samples were confirmed as free form DTC residues by analysis, prior to preparation of fortified samples. Spice samples for studies on safety evaluation and regulatory compliance were collected from spice farms having a history of DTC usage for disease control, and also from local markets in Ernakulam district, Kerala, India. The samples were stored at room temperature.

Sample Preparation

DTC compounds are generally non-systemic, so their residues are likely to be located mostly on the surface of the products being analysed. Hence sample comminution is not commonly required for analysis of the samples. However, spices are usually marketed, and also used in culinary applications, in ground form and hence it is necessary to be able to test for DTC residues in the ground form of spices also.

Both cardamom and black pepper have average essential oil concentrations of approximately 8 and 3% by weight respectively. This essential oil would be released into the extraction medium in the case of ground samples. To ensure that this does not affect the analysis, results from whole and ground forms of naturally contaminated spices were compared.

For preparing powdered samples, the cardamom was ground by using a kitchen blender to a coarse powder in the form in which this spice is typically used in culinary preparations. Black pepper was ground to a finer powder and sieved through ASTM 20 (850 mm) mesh to simulate its typical culinary usage.

Extraction and reduction of DTC Compounds to CS2

A previously reported extraction method in fruits and vegetables (EU Community Reference Laboratories for Residues of Pesticides 2009) was modified and optimized for use with spice matrices. About 25 g sample was accurately weighed into a 250 mL stoppered glass bottle. The sample (for both whole and crushed forms) was soaked in 50 mL water for 30 min. Then, 50 mL isooctane was added, followed by 75 mL of the reaction mixture prepared as detailed in Sect. 2.1.3. The bottle was stoppered and transferred into a covered water bath maintained at 80 °C, with 1-minute shakings at intervals of 10 min, for 1 h. The bottle was then immediately transferred to an ice bath, and 2 mL of the supernatant isooctane layer was pipetted out and centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 min. From the centrifugate, 1 mL of the upper layer was pipetted into a GC autosampler vial for analysis by GC-MS, from which 2 ml was injected in the GC-MS system.

Instrumental conditions

The GC capillary column used for analysis was Agilent 19,091 M-431 DB-5MS (30 m x 250 μm x 0.25 μm 5% diphenyl / 95% dimethylpolysiloxane). Ultrapure helium was used as carrier gas. Injection in split mode was optimized for best response of CS2 in GC-MS, operating in electron ionization (EI) and selected ion monitoring (SIM) modes, with the first quadrupole scanning for the target ions of m/z 76 (quantifier) and 78 (qualifier) with an intensity ratio of approximately 100:9 for confirmation of CS2.

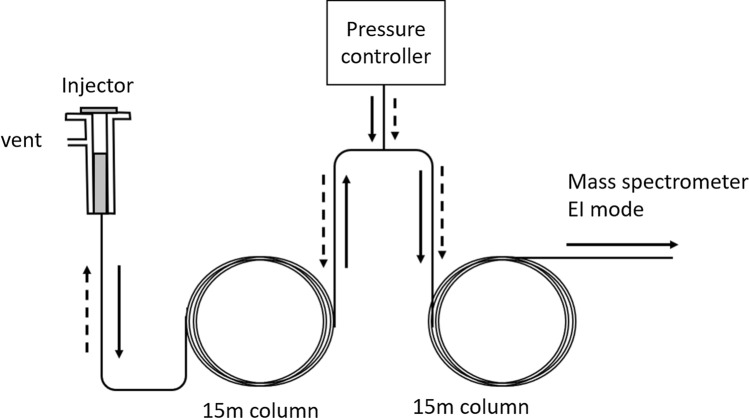

The runtime was 14 min, followed by a post-run program of 10 min which contained a mid-column back flush. This facility, schematically shown in Fig. 2, allowed the flow of carrier gas to be reversed after the elution of the target analyte peak is completed, thereby flushing out the remaining volatiles in the injection. This process helped to maintain consistent response in large batches of samples, especially in complex matrices like black pepper and cardamom. The optimized GC and MS parameters are summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 2.

Schematic of the post-run, mid-column backflush option in GC. Solid arrows indicate the flow of carrier gas during run, and dotted arrows indicate the flow of carrier gas after the post run, mid column back flush is initiated

Table 1.

Optimized GC-MS parameter settings for analysis of CS2

| Parameter | Settings |

|---|---|

| GC parameters | |

| Injector temperature | 150 °C |

| Split injection | Split ratio 20:1 (split flow 22.066 ml/min) |

| Carrier flow | He, 1.1 ml/min |

| Injector conditions | Temperature program: 70 °C hold 0.1 min, ramp at 450 °C/min to 325 °C, hold 2 min, cool at 10 °C/min to 250 °C. |

| Injection volume / mode | 2 ml / split ratio 20:1 |

| Column conditions (run) | Temperature program of 14 min: 40 °C hold 5 min, ramp at 40 °C / min to 200 and hold for 5 min |

| Column conditions (post run) | Post-run program of 10 min at 310 °C: Mid-column back flush, with inlet pressure at 2 psi, backflush column flow − 2.553 ml/min, and onward column flow 2.967 ml/min. |

| MS parameters | |

| Source temperature | 230 °C |

| Ionization / electron energy | Electron ionization (EI) / 70 eV |

| Detector voltage | 1500 V |

| Ion source temperature | 230 °C |

| Damping gas flow | 0.6 ml/min |

| Emission current | 250 µA |

| MS analysis | Selected ion monitoring (SIM), m/z 76 and 78 with unit resolution and dwell time 200 ms |

For quantification, a five-point calibration using CS2 in isooctane was set up, ranging from 0.025 to 0.5 µg mL− 1. A typical routine analysis batch began with a solvent (isooctane) blank, a reagent blank (isooctane) and a matrix blank, followed by the test samples. In every analysis batch, a recovery sample spiked in the range 0.05 to 0.1 mg kg− 1 was included prior to test samples as a QC check, and a reference standard in the concentration range of 0.025 to 0.1 µg mL− 1 was included after every five test samples to verify stability of response.

Validation of the method

Linearity, range and matrix effects

To establish the linearity of response for CS2 against concentration, working standards of 0.025, 0.05, 0.075, 0.125, 0.25 and 0.5 µg mL− 1 were prepared by serial dilution from the intermediate level CS2 reference standard in isooctane, and injected in GC-MS (m/z 76) to prepare the calibration curve. The linearity was assessed using the regression coefficient (R2).

To assess the matrix effect, matrix-matched calibration curves of CS2 were plotted using extracts from blank samples of black pepper and cardamom in the range 0.125 to 1 µg mL− 1 and compared with the calibration curve for CS2 in isooctane plotted in the same concentration range. Matrix effect (ME) was calculated using the following equation (Chawla et al. 2017; Lehotay et al.):

A negative value for ME occurs when the slope of the matrix-matched calibration curve is lower than that of the solvent calibration curve, indicating that matrix suppression is occurring. Similarly, a positive value for ME shows that there is matrix enhancement. This means that for the same peak area for an unknown sample, the value reported using the solvent curve will be lower than that using matrix matched standard when there is matrix suppression (negative ME), and vice versa. An ME of ± 20% are considered small, and suitable for residue analysis (Cuadros-Rodrıguez et al. 2003; Chawla et al. 2017).

Accuracy and precision

Method accuracy was assessed using spike recoveries from fortified samples, using thiram reference standard. According to the procedure outlined in Sect. 2.2.1, thiram was spiked in whole and ground forms of cardamom and black pepper at three levels, viz. 0.1, 0.5 and 1 mg kg-1. The reduction reaction converts thiram to CS2, and 1 mol of thiram generates 2 moles of CS2 (Fig. 1). In order to correlate the spike levels of thiram to the measured value of CS2, the following equation (Liu et al. 2015) was used for recovery calculations:

where CCS2 is the concentration of CS2, Cthiram is the concentration of thiram, k is a constant equal to 2, MCS2 is the molar mass of CS2, 76.1 g mol-1 and Mthiram is the molar mass of thiram, 240.4 g mol-1. Thus, 1 mg of thiram is theoretically equivalent to 0.6340 mg of CS2. The method accuracy was calculated as recovery (%), for which the acceptance criteria was 80–120% (European Commission 2020).

Intra-day precision (repeatability) was calculated as relative standard deviation (RSDr) at three spike levels of 0.05, 0.1 and 0.5 mg kg-1 for whole and ground forms of black pepper and cardamom, with 5 replicates for each sample set (same instrument, same analyst, same day). The predicted relative standard deviation PRSDr was calculated using the Horwitz equation (Horwitz and Albert 2006; Latimer 2016) as , where C is the concentration expressed as unitless mass fraction (e.g. for 1 mg C = 10− 6). The HorRatr value for intralaboratory repeatability (acceptability range 0.3–1.3) was calculated as

Inter-day precision (reproducibility) was calculated as the relative standard deviation (RSDR) at three spike levels of 0.05, 0.1 and 0.5 mg kg-1 for whole and ground forms of black pepper and cardamom, with each fortification level analysed in triplicate on three non-consecutive days (n = 9).

Sensitivity

To assess the sensitivity of the method, the limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ) were calculated. The LOD was taken as the concentration at which the quantifier ion gave a signal to noise (S/N) ratio ≥ 3, and LOQ as the concentration at which the quantifier ion gave an S/N ≥ 10.

Effect of comminution

The analytical results for DTC residues from 5 samples each of naturally contaminated cardamom and black pepper samples, in whole and ground forms, were examined to ascertain the effect of comminution of samples. Average results from replicate analysis of each sample (n = 3) were compared in each case.

Safety evaluation and analysis of real samples

Twenty-six cardamom samples and twelve black pepper samples collected as detailed in Sect. 2.3 were analysed using the optimized method for DTC. The results were evaluated against the Codex MRL of 0.1 mg kg− 1 in cardamom and black pepper (Codex MRL Cardamom 2015; Codex MRL Pepper 2015).

The results were further assessed from the point of view of consumer safety, in terms of the theoretical maximum daily intake (TMDI, mg person− 1 day− 1) as compared against the maximum permissible intake (MPI, mg person− 1 day− 1). The MPI was calculated as the acceptable daily intake (ADI, mg kg− 1) of DTC multiplied by the average body weight of a child, taken as 16 kg (Shabeer et al. 2018). The ADI values assigned by the Codex Joint Meeting of Pesticide Residues (JMPR) was used for the calculations of MPI. The TMDI was calculated as the average incidence level of DTC (mg kg− 1) in cardamom and black pepper multiplied by the average consumption of cardamom and black pepper taken as 0.0038 and 0.014 kg respectively (Siruguri and Bhat 2015).

Results

Optimization of chromatographic conditions

Splitless injection in GC was observed to be unsuitable for obtaining good chromatographic resolution under the experimental conditions used. Hence optimization of CS2 on GC-MS, by monitoring the ion with m/z 76, was done in split injection mode. At a low split ratio of 0.1:1, the response was good but the peak shape was not suitable for quantitative analysis. After progressively increasing split ratio to optimize peak shape and response, the value of 20:1 with a split flow of 22.066 mL min− 1 was adopted as the optimum setting with a retention time of 1.82 min (Supplementary Fig. I).

The use of post-run, mid-column backflush facility was seen to be important in obtaining good chromatographic performance. Although this extended the total runtime by 10 min, it was found to be extremely helpful in maintaining consistency of instrument response, especially after multiple injections in a batch run.

The ion with m/z 76 was used for quantitation, and the ion with m/z 78 with a response of ~ 9% of the quantifier ion was used for confirmation (Supplementary Fig. II). This ratio was observed to be maintained between 8.5 and 10.9 in all the cardamom and black pepper samples analysed, which complied with the compound identification requirement using single quadruple MS techniques as per DG-SANTE guidelines (European Commission 2020).

Accuracy, precision and sensitivity of the method

Accuracy was assessed in terms of the percentage recovery of DTC as CS2 in cardamom and black pepper in both whole and crushed (cardamom) / ground (black pepper) forms. The fortification levels were 0.1 mg kg− 1 (which represented the Codex MRL for DTC in the two spices), 0.5 mg kg− 1 and 1 mg kg− 1. Method precision was assessed in terms of relative standard deviation and HorRat values. The results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Accuracy (% recovery), intra-day precision (RSDr, n = 5) and inter-day precision (RSDR, n = 9) for dithiocarbamates (as CS2) in cardamom and black pepper (whole and crushed/ground forms)

| Fortification level (mg/kg) |

Mean recovery (% ± SD) | RSDr (%) | Predicated RSDr (%)a | HorRatrb | RSDR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardamom | |||||

| 0.1 | 78 (± 5) | 6.7 | 22.4 | 0.30 | 14.8 |

| 0.5 | 82 (± 6) | 6.7 | 17.6 | 0.38 | 13.2 |

| 1.0 | 90 (± 8) | 7.8 | 15.9 | 0.49 | 12.5 |

| Cardamom crushed | |||||

| 0.1 | 73 (± 6) | 7.4 | 22.4 | 0.33 | 10.8 |

| 0.5 | 85 (± 10) | 11.8 | 17.6 | 0.67 | 12.1 |

| 1.0 | 93 (± 6) | 6.8 | 15.9 | 0.43 | 9.2 |

| Black pepper | |||||

| 0.1 | 81 (± 6) | 7.2 | 22.4 | 0.32 | 13.1 |

| 0.5 | 91 (± 5) | 5.3 | 17.6 | 0.30 | 14.2 |

| 1.0 | 97 (± 8) | 8.1 | 15.9 | 0.51 | 12.9 |

| Black pepper ground | |||||

| 0.1 | 78 (± 5) | 7.1 | 22.4 | 0.31 | 11.6 |

| 0.5 | 76 (± 7) | 8.2 | 17.6 | 0.47 | 9.8 |

| 1.0 | 81 (± 9) | 10.6 | 15.9 | 0.67 | 12.1 |

RSDr repeatability relative standard deviation, RSDR Reproducibility relative standard deviation

aPredicted RSD is calculated as

bHorRatr is calculated as RSDr / PRSD

In whole cardamom, the average recoveries (n = 5) were 75, 86, and 98% at spiking levels of 0.1, 0.5 and 1 mg kg− 1 respectively, while in the ground cardamom, the recoveries were 78, 82 and 90% respectively for the same spiking levels. Between whole and crushed cardamom, the variation of recovery levels was in the range 3 to 5%, indicating that the extent of interference of matrix components (including essential oils, which would have been released in higher quantity to the reaction medium in the crushed form) in cardamom was minimal. The standard deveiations in the recovery values were mariginally higher in the crushed samples as compared to the whole samples. The intra-day repeatability values (RSDr) in the whole form were 6.7 to 7.8% in whole and 6.8 to 11.8 in crushed forms. overall, the HorRat values in both whole and crushed forms of cardamom were within the acceptable range of 0.3–1.3 (Latimer 2016). The inter-laboratory precision (RSDR) for whole cardamom was between 12.5 and 14.8%, while that in crushed cardamom was slightly lower at 9.2 to 10.8%.

In black pepper also similar trends were observed in recoveries and standard deviation. For whole black pepper, recovery values obtained were 81, 91 and 97% for 0.1, 0.5 and 1.0 mg kg− 1 fortification levels respectively. In ground samples, these recovery values were lower, at 78, 76 and 81% respectively. The same range standard deviations, ± 5 to ± 9, observed for black pepper for both whole and ground samples, is possibly due to the higher homogeneity was higher in the ground black pepper samples. The HorRat values for whole and ground black pepper were also within the acceptable range. As in the case of cardamom, the inter-day precision (RSDR) values in ground black pepper (9.8 to 12.1%) were slightly lower than those for whole black pepper (12.9 to 14.2%). In all cases, the intra- and inter-day precision values were well below 20%. Limit of detection at 0.025 mg kg− 1 and limit of quantification at 0.05 mg kg− 1 were established in both the spice matrices.

Matrix effects and effects of sample comminution

The matrix-matched calibration curves in the range 0.125 to 1 µg mL− 1 for cardamom and black pepper, were compared against the solvent (isooctane) calibration curve (Supplementary Fig III). The calibration equations and regression coefficients for the solvent and matrix-matched calibration curves for cardamom and black pepper, and the calculated matrix effects for the two spices, is given in Table 3. In both the spices, the average matrix effect was suppressive: −3.8% for black pepper and − 12.4% for cardamom. As the matrix effects observed were low, for routine analysis solvent-based calibration curves were employed for quantitative determination.

Table 3.

Matrix effect (ME, %) in black pepper and cardamom

| Matrix | Calibration equation | Regression coefficient (R2) | ME (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent | y = 1545x + 39,036 | 0.9992 | − |

| Black pepper | y = 1486x + 8373 | 0.9975 | − 3.8 |

| Cardamom | y = 1354x + 15,566 | 0.9972 | − 12.4 |

The comparison of average results from replicate analysis (n = 3) for whole and homogenized form of the two spices (crushed cardamom/ground black pepper), in 5 naturally contaminated samples of each spice, showed only minor variations between whole and homogenized forms. In black pepper the variation between whole and ground forms was between − 0.6 and 0.9% and cardamom the variation was between 0.3 − 0.6%.

Safety evaluation of DTC in cardamom and black pepper

Out of the 26 market samples studied for cardamom, 73.1% were found to be in compliance with the Codex limit of 0.1 mg kg− 1. In the case of the 11 black pepper samples studied, the compliance level was 72.7%.

As per the risk evaluation of DTC by the Codex joint meeting on pesticide residues (JMPR), the ADI for the DTC compounds were fixed as, thiram: 0–0.01 mg kg− 1, ferbam and ziram: 0–0.02 mg kg− 1, and mancozeb, maneb, zineb and metiram: 0–0.03 mg kg− 1(FAO/WHO 1994; Vettorazzi et al. 1995). Although mancozeb is the most prominent DTC compound used for spice cultivation in India, the more stringent ADI assigned to thiram, i.e., 0.01 mg kg− 1, was used for the calculations of MPI. The comparison of the calculated MPI values based on the ADI for DTC residues and the TMDI values based on the average incidence level of DTC residues in real-life samples studied for the two spices, are given in Table 4.

Table 4.

Safety evaluation of dithiocarbamate residues in cardamom and black pepper

| Spice | Average incidence (mg/kg) | Consumption (kg/person/day)a | ADI (mg/kg) |

MPI (mg/person/ day)b |

TMDI (mg/person/ day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardamom | 0.09 (n = 26) | 0.0038 | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.00034 |

| Black pepper | 0.13 (n = 11) | 0.0140 | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.00178 |

aTaken from [30], median quantity of spice intake per day

bADI multiplied by average body weight of a child, taken as 16 kg

Discussion

Using GC-MS method, CS2 recoveries in the range 76–104% with RSD ≤ 15% have been reported in grapes, tomatoes, green chilli and brinjal for fortification levels of thiram in the range of 0.04–1.30 mg kg− 1(Mujawar et al. 2014). Recovery ranges of 81–113% with RSD ≤ 0.1% for fortification levels of thiram in the range 0.5–5.0 mg kg− 1 in soybean leaf, pod and seed, and in the range 75–113% with RSD < 0.05 in soybean oil for the same fortification levels have also been reported (Chawla et al. 2019). In the present study, the average recoveries ranged from 73 to 93% with RSDr ≤ 11.8% in cardamom and from 76 to 97% with RSDr ≤ 10.6 in black pepper. The high volatility of CS2 is also a contributing factor to the precision. However, unlike in earlier studies, an increase in fortification level was not seen to be considerably improving the precision in the case of spices.

Various studies on fruits and vegetables have established limits of detection and quantitation for DTC residues in different ranges using diverse analytical methodology. For example, LOD of 0.01 mg kg− 1 and LOQ of 0.04 mg kg− 1 in grape, brinjal, red pepper, potato and tomato using CS2 based GC-MS method has been reported (Mujawar et al. 2014). Others have demonstrated LOD 0.04–0.1 mg kg− 1 and LOQ of 0.18–0.32 mg kg− 1 in various forms of soybean and soybean oil, using the same method (Chawla et al. 2019). LOD of 0.03 to 0.19 mg kg− 1 for different DTC compounds in apples and tomatoes using an LC-MS/MS method .(Schmidt et al. 2013), and LOQ of 0.1–0.2 mg kg− 1 in various fruits and vegetables using an HPLC-UV method (Ekroth et al. 1998) have also been reported. The present optimized method for spices, with LOD of 0.025 mg kg− 1 and LOQ of 0.05 mg kg− 1 for DTC residues in both cardamom and black pepper, compares well with these values established in other matrices. The LOQ achieved using the present method was sufficient for using the method to assess compliance of the two spices studied with respect to the Codex MRL of 0.1 mg kg− 1.

A matrix enhancement in low ranges (< 10%) has been observed previously in fruits and vegetables while using CS2 analysis in GC-MS (Mujawar et al. 2014). In the case of spices, there is a small amount of matrix suppression in the signal. For GC analysis in general, the type matrix effect expected is signal enhancement (Erney et al. 1993; Schenck and Lehotay 2000; Rahman et al. 2013), due to the interactions of the analyte and matrix molecules with the active sites in the GC injection system and column. This is because the molecules from the matrix, being in higher concentration than the analyte molecules, will occupy and block the available active sites and thus increase the number of analyte molecules entering the mass spectrometer. In the present case, this mechanism does not seem to be operating, as it is likely that the isooctane extract injected does not contain sufficient concentration of matrix components to cause the expected matrix enhancement effect. It is more likely that coeluting peaks might play a role in affecting the ionization of the analyte in EI, thus resulting in a small amount of signal suppression. This seems to be consistent with the approximate essential oil content in the two spice matrices, black pepper (oil content ~ 4%, observed signal suppression − 3.8%) and cardamom (oil content ~ 8%, observed signal suppression − 12.4%). However, as the extent of matrix effect was observed to be low the use of matrix-matched calibration was not needed in quantitative analysis. This offers the possibility that the method could be adapted for testing DTC residues in other classes of spices, like fruits (e.g., chillies), roots and rhizomes (e.g., turmeric, ginger), bulbs (e.g., garlic) etc. where the use of DTC compounds for fungal disease control is prevalent.

A comparison of the results from whole and crushed (cardamom) / ground (black pepper) forms of naturally contaminated samples showed that there was very little effect of matrix components (including essential oils) in the spices on the CS2 generation process. This result, considered along with the fact that DTC are generally non-systemic, indicates that comminution of samples is not required in routine analysis of DTC residues using this method. Although the results for recovery and precision from fortified samples varied slightly between whole and crushed/ground forms, the values were well within acceptable tolerance limits.

During the safety evaluation, it was seen that for both the spices, the TMDI values (0.00034 and 0.00178 mg person− 1 day− 1 for cardamom and black pepper respectively) were much below the MPI values of 0.16 mg person− 1 day− 1, indicating that there was no significant health risk with respect to DTC residues in the samples studied.

Conclusions

The method of analysis of dithiocarbamate residues by acid hydrolysis and reduction to carbon disulphide followed by absorption into isooctane and analysis by GC-MS SIM method, which was earlier reported in vegetables and fruits, has been extended to spices for the first time. The GC chromatographic conditions were optimized with split injection. The novel use of a post-run GC program implementing mid-column backflush, which gave good consistency in instrument response though large batches, was seen to be important in the routine analysis DTC residues in complex matrices like spices. Validation of the method in two spices, viz. cardamom and black pepper, was performed using thiram as a representative compound for dithiocarbamate residues. Method validation parameters like accuracy, precision, linearity, and range were assessed and found acceptable as per international standards. LOD at 0.025 mg kg− 1 and LOQ at 0.05 mg kg− 1 were established in both spice matrices studied. These levels are adequate for compliance assessment of market samples against the Codex MRLs. Recovery studies in the whole and crushed / ground forms of the spices, and the assessment of matrix effects in both spices, proved that there is no significant impact of matrix interference in the optimized analytical method. This offers the possibility of extending the method to other classes of spices also.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the use of instrumentation facilities at Quality Evaluation Laboratory (Kochi, Kerala), Spices Board, Ministry of Commerce, Government of India.

Abbreviations

- DTC

Dithiocarbamates.

- GC-MS

Gas chromatograph - mass spectrometer.

- MRLs

Maximum residue limits.

- TMDI

Theoretical maximum daily intake.

- MPI

Maximum permissible intake.

- ADI

Acceptable daily intake.

- DG-SANTE

Director general for health and food safety (European Union).

Author's contribution

The analytical work was carried out by Ramesh Babu Natarajan, Ranjith Arimboor, Joby Jacob and Binumol Thankan under the guidance of Joby Thomas Kakkasery.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

Yes.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests or competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Arslan S, Mert ID, Yiğitkaya S, Dagaşan O, Sakallı FN, Oztürk S. The false positive effect of residue of sulphur sources on dithiocarbamate analysis based on CS2 measurement. Food Addit Contaminants: Part A. 2019;36:131–140. doi: 10.1080/19440049.2018.1562235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldas ED, Conceição MH, Miranda MCC, de Souza LCKR, Lima JF. Determination of dithiocarbamate fungicide residues in food by a spectrophotometric method using a vertical disulfide reaction system. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:4521–4525. doi: 10.1021/jf010124a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla S, Patel HK, Gor HN, Vaghela KM, Solanki PP, Shah PG. Evaluation of matrix effects in multiresidue analysis of pesticide residues in vegetables and spices by LC-MS/MS. J AOAC Int. 2017;100:616–623. doi: 10.5740/jaoacint.17-0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla S, Patel H, Kalasariya R, Shah P. Validation and analysis of thiram, a dithiocarbamate, as CS2 from soybean (Glycine max) samples on GC–MS. Int J Environ Sci Technol. 2019;16:6991–6998. doi: 10.1007/s13762-018-2069-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Codex MRL, Cardamom (2015) Codex Maximum Residue Limits in HS 0775 - Cardamom. http://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/codex-texts/dbs/pestres/commodities-detail/en/?lang=en&c_id=745. Accessed 11 Feb 2021

- Codex MRL, Pepper (2015) Codex Maximum Residue Limits in HS 0790 - Pepper, black, white. http://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/codex-texts/dbs/pestres/commodities-detail/en/?c_id=171. Accessed 11 Feb 2021

- Crnogorac G, Schwack W. Residue analysis of dithiocarbamate fungicides. TRAC Trends Anal Chem. 2009;28:40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2008.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cuadros-Rodríguez L, García-Campaña AM, Almansa-López E, Egea-González FJ, Cano MLC, Frenich FG, Martínez-Vidal JL. Correction function on biased results due to matrix effects: application to the routine analysis of pesticide residues. Anal Chim Acta. 2003;478:281–301. doi: 10.1016/S0003-2670(02)01508-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey JK, Heberer T, Stan H-J. Determination of ethylenethiourea in food commodities by a two-step derivatization method and gas chromatography with electron-capture and nitrogen-phosphorus detection. J Chromatogr A. 1997;765:31–38. doi: 10.1016/S0003-2670(02)01508-8021-9673(96)01008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekroth SB, Ohlin B, Österdahl B-G. Rapid and simple method for determination of thiram in fruits and vegetables with high-performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detection. J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46:5302–5304. doi: 10.1021/jf980910o. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erney D, Gillespie A, Gilvydis D, Poole C. Explanation of the matrix-induced chromatographic response enhancement of organophosphorus pesticides during open tubular column gas chromatography with splitless or hot on-column injection and flame photometric detection. J Chromatogr A. 1993;638:57–63. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(93)85007-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- EU Community Reference Laboratories for Residues of Pesticides (2009) Analysis of Dithiocarbamate Residues in Foods of Plant Origin involving Cleavage into Carbon Disulfide, Partitioning into Isooctane and Determinative Analysis by GC-ECD, Single Residue Method Version 2. https://www.eurl-pesticides.eu/library/docs/srm/meth_DithiocarbamatesCs2_EurlSrm.PDF. Accessed 20 Jul 2020

- EUR-Lex (2021) The European Pesticide Database. https://ec.europa.eu/food/plant/pesticides/eu-pesticides-db_en. Accessed 11 Feb 2021

- FAO/WHO (1994) Pesticide Residues in Food-1993 Evaluations. Part 11-Toxicology

- Gras R, Luong J, Shellie R. Gas chromatography and diode array detection for the direct measurement of carbon disulfide in challenging matrices. Anal Methods. 2017;9:3908–3913. doi: 10.1039/C7AY00392G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (2020) Guidance document on analytical quality control and method validation procedures for pesticide residue analysis in food and feed (SANTE/12682/2019)

- Gustafsson KH, Thompson RA. High-pressure liquid chromatographic determination of fungicidal dithiocarbamates. J Agric Food Chem. 1981;29:729–732. doi: 10.1021/jf00106a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz W, Albert R. The Horwitz ratio (HorRat): a useful index of method performance with respect to precision. J AOAC Int. 2006;89:1095–1109. doi: 10.1093/jaoac/89.4.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakitani A, Yoshioka T, Nagatomi Y, Harayama K (2017) A rapid and sensitive analysis of dithiocarbamate fungicides using modified QuEChERS method and liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. J pesticide Sci D 17–025. 10.1584/jpestics.D17-025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kesari R, Gupta V. A sensitive spectrophotometric method for the determination of dithiocarbamate fungicide and its application in environmental samples. Talanta. 1998;45:1097–1102. doi: 10.1016/S0039-9140(97)00208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latimer GW (2016) AOAC Official methods of analysis of AOAC International, 20th edn

- Lehotay SJ, Kwon H, Lucía G-A, Sample Preparation and Matrix Effects in the Detection of Chemical Residues in Foods. http://www.laprw2011.fq.edu.uy/pdf/Lunes/Steven%20Lehotay.pdf. Accessed 25 Dec 2020

- Liu S, Bai A, Zhou L, Yu c, Li Y, Fan S, Pa C. Dissipation and residues of thiram in potato and soil. J Chem. 2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/623847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mujawar S, Utture SC, Fonseca E, Matarrita J, Banerjee K. Validation of a GC–MS method for the estimation of dithiocarbamate fungicide residues and safety evaluation of mancozeb in fruits and vegetables. Food Chem. 2014;150:175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.10.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oellig C, Schwack W. Comparison of HILIC columns for residue analysis of dithiocarbamate fungicides. J Liq Chromatogr Relat Technol. 2017;40:415–418. doi: 10.1080/10826076.2017.1315724. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman MM, El-Aty AA, Shim J-H. Matrix enhancement effect: a blessing or a curse for gas chromatography?—a review. Anal Chim Acta. 2013;801:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravindran P. Black pepper: Piper nigrum. 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravindran P, Madhusoodanan K (2002) Cardamom: the genus Elettaria. Tailor and Francis Group, CRC Press

- Schenck FJ, Lehotay SJ. Does further clean-up reduce the matrix enhancement effect in gas chromatographic analysis of pesticide residues in food? J Chromatogr A. 2000;868:51–61. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(99)01137-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt B, Christensen HB, Petersen A, Sloth JJ, Poulsen ME. Method validation and analysis of nine dithiocarbamates in fruits and vegetables by LC-MS/MS. Food Addit Contaminants: Part A. 2013;30:1287–1298. doi: 10.1080/19440049.2013.801083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabeer TPA, Girame R, Utture S, Oulkar D, Banerjee K, Ajay D, Arimboor R, Menon KRK. Optimization of multi-residue method for targeted screening and quantitation of 243 pesticide residues in cardamom (Elettaria cardamomum) by gas chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (GC-MS/MS) analysis. Chemosphere. 2018;193:447–453. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.10.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siruguri V, Bhat RV. Assessing intake of spices by pattern of spice use, frequency of consumption and portion size of spices consumed from routinely prepared dishes in southern India. Nutr J. 2015;14:7. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-14-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J, Suseela Bhai R (1995) Fungal and bacterial diseases of cardamom. Elettaria cardamomum Maton) and their management

- Vettorazzi G, Almeida WF, Burin GJ, Jaeger RB, Puga FR, Rahde AF, Reyes FG, Schvartsman S. International safety assessment of pesticides: dithiocarbamate pesticides, ETU, and PTU—a review and update. Teratog Carcinog Mutagen. 1995;15:313–337. doi: 10.1002/tcm.1770150608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G, Nie J, Li H, Yan Z, Cheng Y. Determination of mancozeb residue in fruit by derivatization and a modified QuEChERS method using ultraperformance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2017;409:5057–5063. doi: 10.1007/s00216-017-0451-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Yes.